Abstract

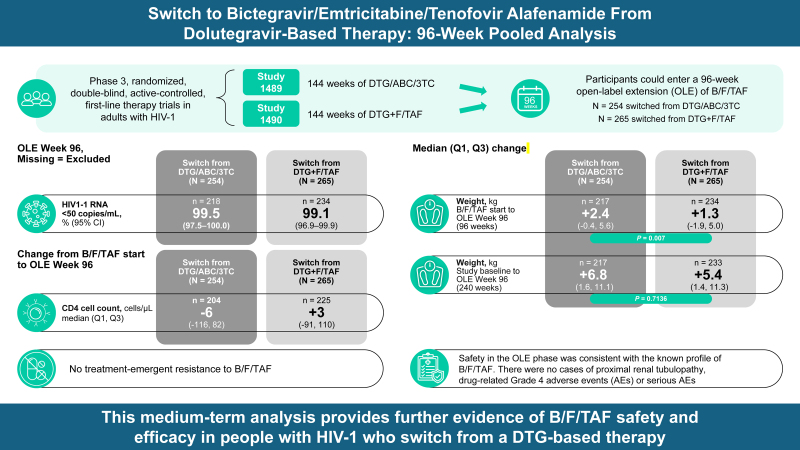

Objective:

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of 96 weeks of bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (B/F/TAF) treatment in participants switching from dolutegravir (DTG)-based therapy.

Design:

Studies 1489 (NCT02607930) and 1490 (NCT02607956) were phase 3 randomized, double-blind, active-controlled, first-line therapy trials in people with HIV-1. After 144 weeks of DTG-based or B/F/TAF treatment, participants could enter a 96-week open-label extension (OLE) of B/F/TAF.

Methods:

A pooled analysis evaluated viral suppression (HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/ml) and changes in CD4+ cell count at OLE Weeks 48 and 96, treatment-emergent resistance, safety, and tolerability after switch from a DTG-based regimen to B/F/TAF. Outcomes by prior treatment were summarized using descriptive statistics and compared by two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Results:

At OLE Week 96, participants who switched to B/F/TAF (N = 519) maintained high levels of virologic suppression (99.5 and 99.1% in those switching from DTG/abacavir/lamivudine and DTG+F/TAF, respectively) and CD4+ cell count, with no treatment-emergent resistance to B/F/TAF. Twenty-one participants experienced drug-related adverse events after switching, with diarrhea, weight gain, and headache occurring most commonly. There were no cases of proximal renal tubulopathy, drug-related Grade 4 adverse events, or serious adverse events. Two participants discontinued B/F/TAF due to treatment-related adverse events. Participants who switched from DTG/abacavir/lamivudine experienced statistically significant greater weight gain than those who switched from DTG+F/TAF; however, median weight change from the blinded phase baseline to OLE Week 96 was numerically similar across treatment groups.

Conclusion:

This medium-term analysis demonstrates the safety and efficacy of switching to B/F/TAF from a DTG-containing regimen in people with HIV-1.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, bictegravir, efficacy, HIV-1, regimen switch, safety, tenofovir alafenamide

Introduction

The number of people with HIV accessing antiretroviral therapy (ART) is increasing, from 7.8 million in 2010 to 28.7 million in 2021 [1]. Furthermore, increased longevity on HIV therapy means that people will require decades of ART. Managing emerging comorbidities and drug interactions as people age on ART is an increasing challenge [2,3]. Simplification of treatment regimens and treatment switches to optimize care may be needed [2–4]. There are many different reasons why a provider or patient may want or need to switch their ART regimen. Evaluating medium and long-term clinical trial outcomes, where available, can guide decisions on optimal treatment options for specific subpopulations.

Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (B/F/TAF) is a three-drug, fixed-dose, single-tablet regimen containing an integrase strand transfer inhibitor, bictegravir, and two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, emtricitabine and TAF. Clinical trial results have shown that B/F/TAF is highly effective and well tolerated in adults [5–10]. There is also growing evidence supporting the use of B/F/TAF in routine clinical practice [11–13].

B/F/TAF (50/200/25 mg) is approved for adults in many countries around the world [14,15] and is recommended in international HIV guidelines in high-income countries, both as first-line and as a switch regimen for those with virologic suppression [2–4].

Study 1489 and Study 1490 are randomized, double-blinded, phase 3 clinical trials that evaluated the long-term efficacy and safety of either dolutegravir (DTG)-based treatment or B/F/TAF over 144 weeks [7,16,17]. Here, we report the efficacy and safety of 96 weeks of B/F/TAF treatment in participants who switched from DTG-based therapy on completion of the blinded phase at 144 weeks.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

Studies 1489 (GS-US-380–1489, NCT02607930) and 1490 (GS-US-380-1490, NCT02607956) were phase 3, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, active-controlled studies. Study 1489 was conducted in Europe, Latin America, and North America; Study 1490 in Australia, Europe, Latin America, and North America [7,16,17]. Detailed methods for these studies and eligibility criteria were described previously [16,17].

In short, participants with plasma HIV-1 RNA levels of at least 500 copies/ml and no more than 10 days of prior ART were randomized 1 : 1 in Study 1489 to receive first-line therapy with B/F/TAF (n = 316) or DTG/abacavir/lamivudine (DTG/ABC/3TC; n = 315) and in Study 1490 to receive first-line therapy with B/F/TAF (n = 327) or DTG+F/TAF (n = 330) in a double-blinded fashion. Participants with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection or who were HLA-B∗5701 positive at screening were excluded from Study 1489; participants with acute hepatitis within 30 days prior to study entry were excluded from both studies.

Both studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, with the understanding and the informed written consent of each participant. Site-specific independent ethics committees approved the protocols.

Study endpoints and assessments

The primary endpoints of both studies were published previously [16,17]. The open-label extension (OLE) endpoints in both studies included the following secondary endpoints: the proportion of participants who achieved HIV-1 RNA less than 50 copies/ml at OLE Weeks 48 and 96, as defined by missing = excluded (M = E) and missing = failure (M = F) analyses; and changes from B/F/TAF start in CD4+ cell count at OLE Weeks 48 and 96. Other endpoints included treatment-emergent resistance, safety (including change in weight), and treatment discontinuations.

In the OLE phase, efficacy and safety were assessed at Week 12 and subsequently every 12 weeks for at least 96 weeks. Safety was assessed by physical examination (including vital signs measurements and weight), laboratory tests, and review of concomitant medications and adverse events (coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 24.0). Adverse events and laboratory abnormalities were graded according to the Gilead Sciences, Inc. (GSI) Grading Scale for Severity of Adverse Events and Laboratory Abnormalities (version 01 April 2015). Laboratory tests included measurement of plasma HIV-1 RNA, CD4+ cell counts, hematological analyses (chemistry profile, metabolic assessments [fasting glucose and lipid parameters], estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR]), and urine sample analysis. The Cockcroft–Gault formula was used to calculate eGFR [18].

Participants with HIV-1 RNA of at least 200 copies/ml at the last on-treatment visit or at the visit following HIV-1 of at least 50 copies/ml (confirmed virologic failure) without resuppression of HIV-1 RNA to less than 50 copies/ml while on treatment were assessed for genotypic and phenotypic resistance. Resistance testing methods and a list of surveillance resistance-associated mutations have been published previously [19].

Statistical analysis

Demographic and baseline characteristics were summarized using standard descriptive methods, including sample size, mean, standard deviation, median, quartile (Q) 1 and Q3, minimum and maximum for continuous variables, and frequency and percentages for categorical variables. The proportion of participants who achieved HIV-1 RNA less than 50 copies/ml was defined by M = E and M = F algorithms and summarized together with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) calculated using the Clopper–Pearson exact method. The changes from B/F/TAF start in CD4+ cell count, safety data, and other outcomes were summarized by prior treatment using descriptive statistics. Changes in weight were summarized by prior treatment as absolute change from B/F/TAF start and as an annual change. A two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare groups.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics at the time of B/F/TAF start

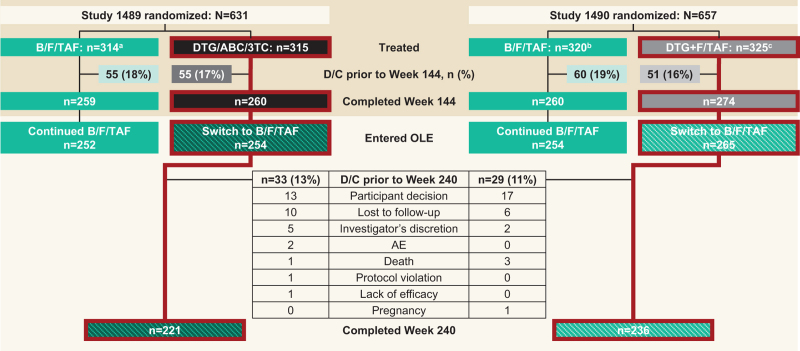

Overall, 519 of 534 (97.2%) participants who completed 144 weeks of DTG-based ART were switched to B/F/TAF and included in this analysis: 254 of 260 participants from Study 1489 and 265 of 274 participants from Study 1490. In total, 457 of 519 (88.1%) participants completed Week 240 (OLE Week 96); 221 of 254 (87.0%) participants from Study 1489 and 236 of 265 (89.1%) from Study 1490 (Fig. 1). Demographics and clinical characteristics for participants at the time of B/F/TAF start are summarized in Table 1. Participants in OLE of both studies were predominantly male (88.6% in Study 1489 and 90.2% in Study 1490). The median age at time of B/F/TAF initiation was 36 years in Study 1489 and 38 years in Study 1490. In both studies, approximately one-third of participants who switched to B/F/TAF were Black and over one-fifth were Hispanic/Latinx. The median CD4+ cell count at the time of B/F/TAF start was 766 cells/μl in Study 1489 and 730 cells/μl in Study 1490.

Fig. 1.

Participant disposition from baseline to Week 240 (OLE Week 96).

aTwo participants randomized and not treated; bSeven participants randomized and not treated; cFive participants randomized and not treated. AE, adverse event; B/F/TAF, bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide; D/C, discontinuation; DTG/ABC/3TC, dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine; DTG+F/TAF, dolutegravir plus emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide; OLE, open-label extension.

Table 1.

Demographics and disease characteristics at the time of B/F/TAF starta,b

| Study 1489 (DTG/ABC/3TC switch to B/F/TAF) (N = 254) | Study 1490 (DTG+F/TAF switch to B/F/TAF) (N = 265) | |

| Age, median (Q1, Q3), years | 36 (30, 45) | 38 (30, 48) |

| Sex at birth, n (%) | ||

| Male | 225 (88.6) | 239 (90.2) |

| Female | 29 (11.4) | 26 (9.8) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 144 (56.7) | 160 (60.4) |

| Black | 94 (37.0) | 80 (30.2) |

| Asian | 8 (3.1) | 7 (2.6) |

| Other | 8 (3.1) | 18 (6.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 54 (21.3) | 73 (27.5) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latinx | 199 (78.7) | 192 (72.5) |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Weight, median (Q1, Q3), kg | 83.0 (72.6, 94.3) | 81.7 (71.0, 96.0) |

| BMI, median (Q1, Q3), kg/m2 | 26.3 (23.5, 30.4) | 26.3 (23.5, 30.8) |

| HIV-1 RNA | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3), log10 copies/ml | 1.28 (1.28, 1.28) | 1.28 (1.28, 1.28) |

| <50 copies/ml, n (%) | 245 (96.5) | 263 (99.2) |

| 50 to <200 copies/ml, n (%) | 3 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) |

| ≥200 copies/ml, n (%) | 6 (2.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| CD4+ cell count | ||

| Median (Q1, Q3), cells/μl | 766 (599,1023) | 730 (550, 958) |

| ≥50 to <200 cells/μl, n (%) | 0 | 3 (1.1) |

| ≥200 to <500 cells/μl, n (%) | 40 (15.7) | 46 (17.4) |

| ≥500 cells/μl, n (%) | 214 (84.3) | 216 (81.5) |

| eGFRCG, median (Q1, Q3), ml/min | 115.6 (98.5, 137.6) | 111.0 (95.1, 134.8) |

B/F/TAF, bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide; DTG/ABC/3TC, dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine; DTG+F/TAF, dolutegravir plus emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide; eGFRCG, estimated glomerular filtration rate by Cockcroft–Gault; Q, quartile.

Baseline value for switch to B/F/TAF was defined as the last nonmissing value obtained during or before the first dose of open-label B/F/TAF.

Missing values were excluded from the percentage calculations.

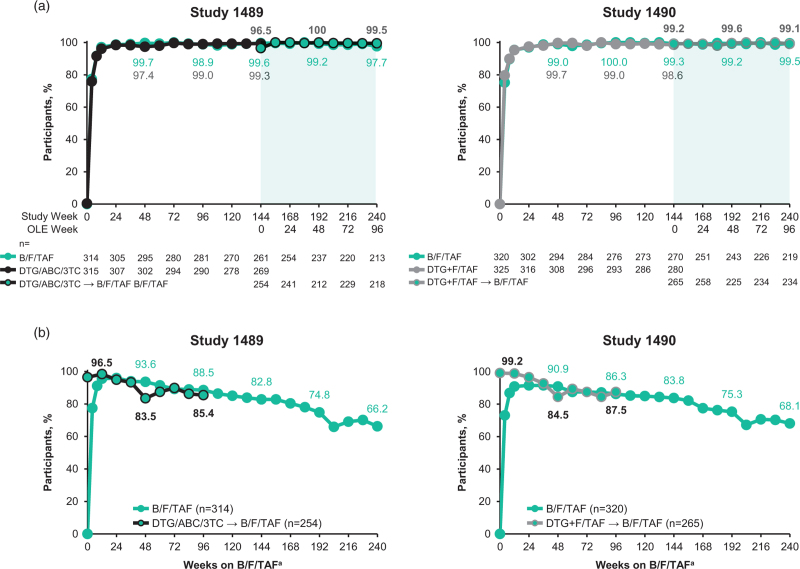

Efficacy

At Week 240 (OLE Week 96), rates of virologic suppression were similar among participants who switched from DTG-based regimens and those initially randomized to B/F/TAF (Fig. 2). HIV-1 RNA data were missing for three participants who switched to B/F/TAF in Study 1489 and two participants who switched to B/F/TAF in Study 1490. In the M = E analysis, participants who switched to B/F/TAF from DTG/ABC/3TC or DTG+F/TAF maintained high levels of virologic suppression (HIV RNA <50 copies/ml) until OLE Week 96 (Fig. 2a). At OLE Week 96, virologic suppression rates were 99.5% (95% CI, 97.5–100.0; M = E; 217/218 participants) in those who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC and 99.1% (95% CI, 96.9–99.9; M = E; 232/234 participants) in those who switched from DTG+F/TAF. In the M = F analysis, rate of virologic suppression at OLE Week 96 in participants who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC to B/F/TAF was 85.4% (95% CI, 80.5–89.5; 217/254 participants) and for those switching from DTG+F/TAF, it was 87.5% (95% CI, 83.0–91.3; 232/265 participants) (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of participants with HIV-1 RNA <50 copies/ml to OLE Week 96. (a) M = E analysis and (b) M = F analysis.

Bold numbers display; M = E results for participants who switched to B/F/TAF from DTG-based regimens. aFor participants who switched to B/F/TAF from DTG-based regimens, “weeks on B/F/TAF” indicates the time since the start of the OLE; for participants who remained on B/F/TAF throughout the blinded and OLE phases, “weeks on B/F/TAF” indicates the time since the start of the blinded phase. B/F/TAF, bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide; DTG/ABC/3TC, dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine; DTG+F/TAF, dolutegravir plus emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide; M = E, missing = excluded; M = F, missing = failure; OLE, open-label extension.

At OLE Week 96, data were missing for 36 of 254 (14.2%) participants who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC and 31 of 265 (11.7%) participants who switched from DTG+F/TAF. Two (0.6%) participants receiving blinded DTG/ABC/3TC had HIV-1 RNA of at least 200 copies/ml at the time of switch, both of whom had a M184 V substitution and resuppressed on B/F/TAF (Supplementary Figure 1). In total, three of 254 (1.2%) participants who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC met criteria for resistance testing during the OLE phase (one participant at OLE Week 36 and one participant at OLE Week 72, both of whom also met the criteria for resistance testing during the blinded treatment phase; and one participant at OLE Week 96) and one of 265 (0.4%) who switched from DTG+F/TAF met criteria for resistance testing (at OLE Weeks 12 and 24; also met criteria during blinded treatment phase). None of these participants developed treatment-emergent resistance during the OLE.

Immunological outcomes

In participants who switched to B/F/TAF from DTG/ABC/3TC, the median (Q1, Q3) changes in CD4+ cell count from B/F/TAF start to OLE Week 48 and OLE Week 96 were -6 (-113, 104; n = 212) cells/μl and -6 (-116, 82; n = 204) cells/μl, respectively. In those who switched to B/F/TAF from DTG+F/TAF, the median changes (Q1, Q3) in CD4+ cell count were +14 (-83, 117; n = 223) cells/μl and +3 (-91, 110; n = 225) cells/μl, respectively.

Safety and tolerability

Overall, 214 of 254 (84.3%) of participants who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC and 215/265 (81.1%) of those who switched from DTG+F/TAF experienced adverse events by OLE Week 96 (Table 2). Drug-related adverse events were experienced by 13 of 254 (5.1%) participants who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC and 8 of 265 (3.0%) participants who switched from DTG+F/TAF. The most common drug-related adverse events in the OLE were diarrhea (3/519 [0.6%] of participants), weight gain (3/519 [0.6%] of participants) and headache (2/519 [0.4%] of participants). The incidence of nausea and diarrhea declined numerically after switching from a DTG-based regimen to B/F/TAF in the OLE (Supplementary Figure 2). Drug-related nausea and diarrhea were reported in 1 of 254 (0.4%) and 2 of 254 (0.8%) participants, respectively, who switched to B/F/TAF from DTG/ABC/3TC (no incidence of drug-related nausea or diarrhea from OLE Week 8 to 96 in evaluable participants). In participants who switched from DTG+F/TAF, no drug-related nausea or diarrhea were reported in evaluable participants during the OLE.

Table 2.

Adverse events during Weeks 144–240 (OLE)a,b

| Switch from DTG/ABC/3TC to B/F/TAF (N = 254) | Switch from DTG+F/TAF to B/F/TAF (N = 265) | |

| Any AE, n (%) | 214 (84.3) | 215 (81.1) |

| Drug-related AE, n (%) | 13 (5.1) | 8 (3.0) |

| ≥2 participants in either group or overall, n (%) | ||

| Diarrhea | 3 (1.2) | 0 |

| Weight increased | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Headache | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| Grade 3 or 4 drug-related AE, n (%) | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Any SAE | 19 (7.5) | 32 (12.1) |

| Drug-related SAE | 0 | 0 |

| Discontinued B/F/TAF due to drug-related AEc | 2 (0.8) | 0 |

| Deaths | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.1) |

AE, adverse event; B/F/TAF, bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide; DTG/ABC/3TC, dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine; DTG+F/TAF, dolutegravir plus emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide; OLE, open-label extension; SAE, serious adverse event.

Severity grades were defined by Gilead Grading Scale for Severity of AE and Laboratory Abnormalities.

Relatedness to study drug was assessed by the investigator.

The drug-related AE leading to B/F/TAF discontinuation were weight gain and obesity.

No drug-related Grade 4 adverse events or serious adverse events were reported. There was one Grade 3 adverse event that was designated by the investigator as study drug-related. The investigator deemed existing diabetes mellitus in one participant (first reported during the blinded phase while on DTG+F/TAF) to have worsened on Day 1 after switching to B/F/TAF. The event (worsening of diabetes without accompanied excessive weight gain) resolved within 15 weeks and did not result in study discontinuation. None of the participants who switched to B/F/TAF experienced drug-related cardiovascular events after the switch (Supplementary Table 1). Hypertension was reported in 12 of 254 (4.7%) and 11 of 265 (4.2%) participants, who switched to B/F/TAF from DTG/ABC/3TC and DTG+F/TAF, respectively. No new-onset HBV infections were reported in participants on B/F/TAF.

In total, of 519 participants across both studies, 23 (4%) participants initiated antihypertension medication, 17 (3%) participants initiated lipid-lowering agents, and seven (1%) initiated antidiabetes agents during OLE.

Median eGFR changes were negligible in participants receiving B/F/TAF during the OLE (Supplementary Figure 3), with no reported cases of proximal renal tubulopathy.

Discontinuations

Across both studies, 2 of 519 participants (0.4%) experienced a drug-related adverse event that led to discontinuation of the study drug after switching (weight gain and obesity, respectively); both switched from DTG/ABC/3TC (Table 2). Other reasons for discontinuation included participant's decision (n = 30), loss to follow-up (n = 16), investigator's discretion (n = 7), protocol violation (n = 1), lack of efficacy (n = 1), and pregnancy (n = 1) (Fig. 1). There were no discontinuations due to renal adverse events. In total, five deaths occurred during the OLE: two in participants who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC (one due to seizures and one of unknown cause in a participant with known cardiovascular disease and risk factors) and three in participants who switched from DTG+F/TAF (one due to malignant neoplasm of urinary bladder and two of unknown cause, including one in a participant with known cardiovascular disease and risk factors and one in a participant with no history of cardiovascular disease or risk factors). None of the participants who died had emergent hypertension, emergent diabetes, or initiated statins after the switch to B/F/TAF.

Laboratory abnormalities

Overall, 76 of 519 (15%) participants (34/254 [13%] of those who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC and 42/265 [16%] of those who switched from DTG+F/TAF) experienced any Grade 3 or 4 laboratory abnormality (Supplementary Table 2). The most common treatment-emergent Grade 3 or 4 laboratory abnormalities in participants who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC were increased creatine kinase (9/252 [4%] of participants), increased amylase and increased aspartate aminotransferase (5/252 [2%] of participants each); none were associated with clinical symptoms of pancreatitis. In those who switched from DTG+F/TAF, the most common laboratory abnormalities were increased creatine kinase (7/264 [3%] of participants), nonfasting hyperglycemia (5/143 [3%] of participants), increased fasting low-density lipoprotein (8/257 [3%] of participants), and glycosuria (9/264 [3%] of participants, all with concomitant hyperglycemia).

Minor changes in lipids were observed among participants who switched to B/F/TAF (Supplementary Figure 4). Median (95% CI) change from Week 144 (OLE Week 0) in fasting total cholesterol-to-high-density lipoprotein (HDL) ratio at Week 240 (OLE Week 94) was 0.1 (-0.3, 0.5) in those who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC and 0.1 (-0.4, 0.5) in participants who switched from DTG+F/TAF.

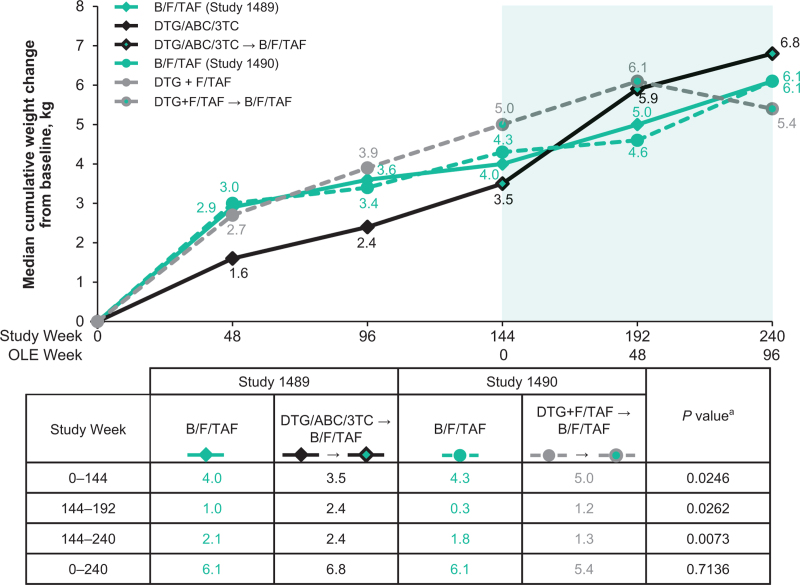

Changes in weight

At Week 144 (OLE Week 0), significantly smaller median weight changes from baseline were observed with DTG/ABC/3TC than with DTG+F/TAF: +3.5 versus +5.0 kg (P = 0.025) (Fig. 3). Between Weeks 144 and 240 (OLE Weeks 0 and 96), participants who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC had greater weight changes than those who switched from DTG+F/TAF. Median (Q1, Q3) at Week 240 (OLE Week 96) was +2.4 (-0.4, +5.6) kg versus +1.3 (-1.9, +5.0) kg (P = 0.007), respectively. Cumulative median (Q1, Q3) weight changes at Week 240 (OLE Week 96) from baseline in the blinded phase were numerically similar for all treatment groups: 6.8 (1.6, 11.1) kg in those who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC; 5.4 (1.4, 11.3) kg in those who switched from DTF+F/TAF; 6.1 (2.0, 11.1) kg in those originally randomized to B/F/TAF in Study 1489; and 6.1 (2.3, 12.6) kg in those originally randomized to B/F/TAF in Study 1490.

Fig. 3.

Weight changes from baseline through Week 240 (OLE 96).

Numbers in the table show median weight changes for the time periods specified. aP value for comparison of median weight change in the DTG/ABC/3TC switch to B/FTAF group versus the DTG+F/TAF switch to B/F/TAF group. B/F/TAF, bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide; DTG/ABC/3TC, dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine; DTG+F/TAF, dolutegravir plus emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide; OLE, open-label extension.

Discussion

During the blinded phase of studies 1489 and 1490, B/F/TAF demonstrated noninferior efficacy and safety to DTG/ABC/3TC or DTG+F/TAF in people on first-line ART over 144 weeks [6,9,17]. The OLE phase of these studies evaluated the impact of switching from DTG-based treatment to B/F/TAF at the end of the 144-week blinded treatment phase. In the OLE phase we saw consistent efficacy and safety results after 96 weeks of B/F/TAF treatment in participants who had initially been randomized to DTG-based treatment.

During the follow-up, adults who switched from DTG-based treatment to B/FTAF in studies 1489 and 1490 maintained high rates of virologic suppression with no treatment-emergent resistance to B/F/TAF during 96 weeks of treatment [10]. Two participants with M184 V had HIV-1 RNA of at least 200 copies/ml at the time of switching from DTG/ABC/3TC. Both participants subsequently had sustained resuppression on B/F/TAF. Consistent with findings seen in other clinical trials [15], there were no cases of treatment-emergent resistance with B/F/TAF. These data confirm and extend the previous 144- and 240-week follow-up results of B/F/TAF in the blinded and open-label phases, respectively [6,10], and 48-week follow-up results of B/F/TAF switch from DTG/ABC/3TC [5].

Safety in the OLE phase was consistent with the known profile of B/F/TAF [6,8–11,15,17], and tolerability was reflected by few discontinuations. Outside of a clinical trial setting, results from a large observational cohort have demonstrated maintenance of virologic control and no new or unexpected safety findings after switching to B/F/TAF from other regimens in people with HIV in routine clinical care [13].

The two most common AE with DTG-based regimens in the blinded phase of studies 1489 and 1490 were nausea and diarrhea [6,16]. However, consistent with previous reports [7,16,20], the incidence and prevalence of nausea and diarrhea improved after switching to B/F/TAF, possibly due to better gastrointestinal tolerability of TAF than ABC in Study 1489 [21,22]. The median lipid changes were small and the impact of the switch to B/F/TAF on total cholesterol-to-HDL ratio was minimal, similar to those observed during the 240-week follow-up in participants initially randomized to receive B/F/TAF [10]. Subsequently, the number of participants who initiated lipid-lowering agents, antihypertensives, and antidiabetic agents after the switch was also small. No cases of proximal renal tubulopathy and no discontinuations due to renal adverse events were observed in participants receiving B/F/TAF, providing further evidence of the renal safety profile of B/F/TAF.

During the first 144 weeks (blinded phase) of the study, participants on DTG/ABC/3TC had lower weight gain than those who were on DTG+F/TAF (3.5 versus 5.0 kg; P = 0.025). This observation is consistent with a previously reported differential effect of ABC and TAF on weight [22,23]. Between Week 144 (OLE Week 0) and Week 240 (OLE Week 96), significantly greater weight increases were observed in participants who switched to B/F/TAF from DTG/ABC/3TC (2.4 kg) compared with those who switched from DTG+F/TAF (1.3 kg), suggesting that the differential effect of ABC versus TAF on weight gain is reversed on switching to B/F/TAF. The mechanism underlying this effect is unknown. Cumulative weight changes from blinded phase baseline at Week 240 (OLE Week 96) were similar across all treatment groups.

Although one case of new-onset HBV infection was reported in the DTG/ABC/3TC group during the blinded phase, no cases were reported in participants on B/F/TAF, consistent with the prophylactic activity of TAF against HBV [4].

This study has several limitations. While the first 144 weeks of studies 1489 and 1490 were blinded, the data presented here are based on an optional OLE of those studies. This open-label design may have introduced some bias into the study results. Although a 96-week treatment period allows us to monitor medium-term efficacy and safety, we cannot exclude the possibility of adverse events or complications that can only be detected with longer follow-up. However, the efficacy and safety results were consistent with outcomes during the first 144 weeks [10]. The timing of the switch was protocol-defined in this study, so it may not reflect how people chose to switch regimens in real life. A proportion of data was also missing for some participants, and some of the follow-up visits did not take place because of the COVID-19 pandemic; however, similar rates of discontinuation were observed in other antiretroviral studies conducted during this time period [24,25]. In our study, the most common reasons for discontinuation were participant decision, loss to follow-up and investigator's decision; there was also a very low percentage of participants who discontinued due to an adverse event (2% in those who switched from DTG/ABC/3TC; 0% in those who switched from DTG+F/TAF). However, M = E and M = F analyses of viral suppression should sufficiently account for any missing data. Descriptive statistics were used for most outcomes.

Conclusion

Participants in studies 1489 and 1490 who switched to B/F/TAF from a DTG-containing regimen maintained high rates of virologic suppression, with no emergent resistance. The treatment was well tolerated and there were no new safety signals reported during medium-term B/F/TAF treatment. These results provide further medium-term evidence of B/F/TAF safety and efficacy in people with HIV who switch from a DTG-based therapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants and their families, participating sites, investigators, and study staff involved in the study. This work was supported by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (Foster City, California, USA). Medical writing support, including development of a draft outline and subsequent drafts in consultation with the authors, collating author comments, copyediting, fact checking and referencing, was provided by Joanna Nikitorowicz-Buniak, PhD, and Victoria Warwick, PhD, at Aspire Scientific (Bollington, UK), and funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (Foster City, California, USA).

C.O., A.A., J.K.R., S.M.-G., C.T.M., J.-M.M., A.L., F.M., Y.Y., and A.P. contributed to data collection and data analysis or interpretation. K.A. and J.T.H. contributed to data analysis or interpretation. H.H. and H.M. contributed to study design and data analysis or interpretation. All authors have read and approved the text as submitted.

Gilead Sciences shares anonymized individual patient data upon request or as required by law or regulation with qualified external researchers based on submitted curriculum vitae and reflecting nonconflict of interest. The request proposal must also include a statistician. Approval of such requests is at Gilead Sciences’ discretion and is dependent on the nature of the request, the merit of the research proposed, the availability of the data and the intended use of the data. Data requests should be sent to datarequest@gilead.com.

Data were previously presented in poster format at Glasgow HIV 2022 and published as an abstract in J Int AIDS Soc 2022;25 (Suppl. 6):e26009.

This work was supported by Gilead Sciences, Inc. (Foster City, California, USA).

Conflicts of interest

C.O. has received grants or contracts from Janssen, Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, MSD, and AstraZeneca (paid to institution); payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Janssen, Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, and MSD; and is President of the Medical Women's Federation (unpaid) and a governing council member of the International AIDS Society (unpaid). A.A. has received grants or contracts from Gilead Sciences, AstraZeneca, and ViiV Healthcare; consulting fees from Gilead Sciences, AstraZeneca, GSK, Merck, Janssen-Cilag, Moderna, Mylan, Pfizer, and ViiV Healthcare; and support for attending meetings and/or travel from Gilead Sciences. J.K.R. has received payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Gilead Sciences, Janssen, MSD, and ViiV Healthcare; and honoraria for consulting from Boehringer. S.-M.G. has received grants or contracts from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Janssen Pharmaceutical, and MSD; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Janssen Pharmaceutical, and MSD; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Janssen Pharmaceutical, and MSD; and payment for participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Janssen Pharmaceutical, and MSD. C.T.M. has received payments or honoraria for speakers’ bureaus from Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Theratechnologies, and AbbVie. J.-M.M. has received grants or contracts from Gilead Sciences (paid to institution); consulting fees from Gilead Sciences, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare; and payment for participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Aelix. K.A., H.H., and J.T.H., are employees of Gilead Sciences and hold stocks. H.M. was an employee of Gilead Sciences at the time of the study and holds stocks in the company. A.P. has received grants or contracts from Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare (paid to institution); payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, or educational events from Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare; and is President of NEAT ID and a member of guideline committees for BHIVA and EACS. A.L., F.M., and Y.Y. have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Retired. Affiliation at the time of the study.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Global HIV and AIDS statistics. 2022. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.[Accessed 14 August 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.European AIDS Clinical Society. Guidelines Version 11.1. October 2022. https://www.eacsociety.org/media/guidelines-11.1_final_09–10.pdf. [Accessed 14 August 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gandhi RT, Bedimo R, Hoy JF, Landovitz RJ, Smith DM, Eaton EF, et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2022 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA 2023; 329:63–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services. Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. September 2022. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/adult-adolescent-arv/guidelines-adult-adolescent-arv.pdf. [Accessed 14 August 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molina JM, Ward D, Brar I, Mills A, Stellbrink HJ, Lopez-Cortes L, et al. Switching to fixed-dose bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide from dolutegravir plus abacavir and lamivudine in virologically suppressed adults with HIV-1: 48 week results of a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, active-controlled, phase 3, noninferiority trial. Lancet HIV 2018; 5:e357–e365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orkin C, DeJesus E, Sax PE, Arribas JR, Gupta SK, Martorell C, et al. Fixed-dose combination bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir-containing regimens for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: week 144 results from two randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3, noninferiority trials. Lancet HIV 2020; 7:e389–e400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sax PE, Rockstroh JK, Luetkemeyer AF, Yazdanpanah Y, Ward D, Trottier B, et al. Switching to bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide in virologically suppressed adults with HIV. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 73:e485–e493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stellbrink HJ, Arribas JR, Stephens JL, Albrecht H, Sax PE, Maggiolo F, et al. Co-formulated bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: week 96 results from a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3, noninferiority trial. Lancet HIV 2019; 6:e364–e372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wohl DA, Yazdanpanah Y, Baumgarten A, Clarke A, Thompson MA, Brinson C, et al. Bictegravir combined with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir, abacavir, and lamivudine for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: week 96 results from a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3, noninferiority trial. Lancet HIV 2019; 6:e355–e363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sax PE, Arribas JR, Orkin C, Lazzarin A, Pozniak A, DeJesus E, et al. Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide as initial treatment for HIV-1: five-year follow-up from two randomized trials. EClinicalMedicine 2023; 59:101991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ambrosioni J, Rojas LJ, Berrocal L, Inciarte A, de la Mora L, González-Cordón A, et al. Real-life experience with bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in a large reference clinical centre. J Antimicrob Chemother 2022; 77:1133–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mounzer K, Brunet L, Fusco JS, McNicholl IR, Diaz CH, Sension M, et al. Advanced HIV infection in treatment-naïve individuals: effectiveness and persistence of recommended 3-drug regimens. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 9:ofac018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esser S, Brunetta J, Inciarte A, Levy I, D’Arminio Monforte A, Lambert JS, et al. Twelve-month effectiveness and safety of bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in people with HIV: real-world insights from BICSTaR cohorts. HIV Med 2023. doi: 10.1111/hiv.13593. [Online ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilead Sciences. Biktarvy 50 mg/200 mg/25 mg film-coated tablets: European summary of product characteristics. 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/biktarvy-epar-product-information_en.pdf. [Accessed 14 August 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilead Sciences. Biktarvy highlights of US prescribing information. 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/210251s013lbl.pdf. [Accessed 14 August 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallant J, Lazzarin A, Mills A, Orkin C, Podzamczer D, Tebas P, et al. Bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir, abacavir, and lamivudine for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (GS-US-380-1489): a double-blind, multicentre, phase 3, randomised controlled noninferiority trial. Lancet 2017; 390:2063–2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sax PE, Pozniak A, Montes ML, Koenig E, DeJesus E, Stellbrink HJ, et al. Coformulated bictegravir, emtricitabine, and tenofovir alafenamide versus dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (GS-US-380-1490): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3, noninferiority trial. Lancet 2017; 390:2073–2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron 1976; 16:31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acosta RK, Willkom M, Martin R, Chang S, Wei X, Garner W, et al. Resistance analysis of bictegravir-emtricitabine-tenofovir alafenamide in HIV-1 treatment-naive patients through 48 weeks. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63:e02533–e2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lagi F, Botta A, Ciccullo A, Picarelli C, Fabbiani M, di Giambenedetto S, et al. Early discontinuation of DTG/ABC/3TC and BIC/TAF/FTC single-tablet regimens: a real-life multicenter cohort study. HIV Res Clin Pract 2021; 22:96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sax PE, Erlandson KM, Lake JE, McComsey GA, Orkin C, Esser S, et al. Weight gain following initiation of antiretroviral therapy: risk factors in randomized comparative clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:1379–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood BR, Huhn GD. Excess weight gain with integrase inhibitors and tenofovir alafenamide: what is the mechanism and does it matter?. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021; 8:ofab542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erlandson KM, Carter CC, Melbourne K, Brown TT, Cohen C, Das M, et al. Weight change following antiretroviral therapy switch in people with viral suppression: pooled data from randomized clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:1440–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osiyemi O, De Wit S, Ajana F, Bisshop F, Portilla J, Routy JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching to dolutegravir/lamivudine versus continuing a tenofovir alafenamide-based 3- or 4-drug regimen for maintenance of virologic suppression in adults living with human immunodeficiency virus type 1: results through week 144 from the phase 3, noninferiority TANGO randomized trial. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 75:975–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Overton ET, Richmond G, Rizzardini G, Thalme A, Girard PM, Wong A, et al. Long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine dosed every 2 months in adults with human immunodeficiency virus 1 type 1 infection: 152-week results from ATLAS-2 M, a randomized, open-label, phase 3b, noninferiority study. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76:1646–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.