Abstract

The Polycomb group proteins are transcriptional repressors that are thought to act through multimeric nuclear complexes. We show that ph and Psc coprecipitate with Pc from nuclear extracts. We have analyzed the domains required for the association of Psc with ph and Pc by using the yeast two-hybrid system and an in vitro protein-binding assay. Psc and ph interact through regions of sequence conservation with mammalian homologs, i.e., the H1 domain of ph (amino acids 1297 to 1418) and the helix-turn-helix-containing region of Psc (amino acids 336 to 473). Psc contacts Pc primarily at the helix-turn-helix-containing region of Psc (amino acids 336 to 473), but also at the ring finger (amino acids 250 to 335). The Pc chromobox is not required for this interaction. We discuss the implication of these results for the nature of the complexes formed by Polycomb group proteins.

Restricting the spatial and temporal expression of the transcription factors that control development is a central part of the mechanism by which pattern and structure come into being in a developing organism. In Drosophila melanogaster, cellular identity along the anterior-posterior axis is specified by the homeotic selector genes (23, 26), whose domains of expression are set up by gap and pair-rule genes (17). The Polycomb group (PcG) proteins are required to maintain the fidelity of these domains of expression through later divisions when the early regulators are no longer present. The PcG was originally identified in Drosophila as a group of genes whose mutations cause multiple homeotic transformations similar to gain-of-function mutations of the homeotic selector genes. This similarity is the result of derepression of the homeotic genes outside their proper spatial boundaries (26, 30, 41, 42, 44). Derepression in PcG mutants characteristically occurs at between 5 and 6 h of development, before which time selector gene expression is normal in both degree and pattern, showing that the PcG is required for maintenance of the repressed state but not for initiation of the repression (21, 42, 43).

Mammalian Hox gene expression boundaries appear to be maintained via a mechanism similar to that seen in Drosophila, through mammalian homologs of PcG proteins. Targeted gene replacements of the Psc homologs Bmi-1 (47) and Mel-18 (2) as well as of the Pc homolog M33 (10) cause posterior transformations of the axial skeleton, due to the anterior shift of several Hox gene expression boundaries. Overexpression of Mel-18 in transgenic mice confers the opposite phenotype (4). The surprising result that an M33 transgene partially rescues a Pc mutation in Drosophila demonstrates that there has been remarkable conservation of the mechanism of PcG function between flies and mammals (31).

Another hallmark of PcG mutants is that they display dominant enhancement (1, 7, 9, 22) and in some cases antipodal suppression (7, 9, 24, 37) of each other’s phenotypes, implying that the function of the group as a whole is sensitive to the dosages of its members (22, 27). However such interactions are not seen for every mutant combination or for every phenotype, and in many cases the interaction is allele specific (7). The favored model postulates that the PcG acts as a multimeric protein complex, with phenotypic enhancement being the result of increased perturbation of the complex with an increased number of mutant members. Antisera to ph and Pc coimmunoprecipitate both proteins (13), and antibody staining of polytene chromosomes has shown colocalization for ph-Pc-Pcl at all sites (13, 28), for E(z)-ph/Pc/Pcl at most sites (8), and for Psc-ph/Pc/Pcl and Su(z)2-ph/Pc/Pcl at many sites (29, 39), strengthening the argument for a multimeric complex. However, the fact that many loci stain for some members but not others, as well as the fact that different PcG mutants display different levels of selector gene derepression (42), suggests that if a complex exists, it must be heterogeneous.

A clear understanding of how the PcG proteins carry out their function requires knowing the compositions and structures of protein complexes that they form, how these complexes are assembled, and the factors (DNA, chromatin, basal or other transcription factors, replication factors, and others) with which different members of the complexes ultimately interact. The current knowledge of intracomplex physical interactions in Drosophila is very sparse. We have shown that a 60-amino-acid conserved domain shared by ph and Scm can mediate homotypic and heterotypic complex formation between these two proteins (36). Temperature shift experiments with a temperature-sensitive allele of E(z) suggest that in vivo binding of ph, Psc, and Su(z)2 to most but not all of their sites on salivary gland chromosomes is dependent on E(z) protein (39). This may mean that E(z) plays a role in targeting or fixing certain PcG complexes to their sites. A possible ph-Psc interaction is suggested by recent two-hybrid experiments with the mouse homologs of these proteins, Mph1 and Bmi-1, respectively (3). The C-terminal 292 amino acids of Mph1 interacted with Bmi-1, and a 220-amino-acid putative helical domain of Bmi-1 interacted with Mph1. However, these two domains were not tested against each other, so it is not known whether they interact with each other or with other parts of their respective proteins. The human homologs of ph, HPH1 and HPH2, were recently cloned by using Xenopus Bmi-1 as bait in the two-hybrid system (15). This interaction was delimited to a 295-amino-acid C-terminal fragment of HPH2. The conserved amino-terminal 188 amino acids of the Xenopus homolog of Psc, XBmi-1, has been shown to bind to the Xenopus homolog of Pc, XPc, and Xpc has been shown to bind to itself (40). The mouse homologs of Psc and Su(z)2, Bmi-1 and Mel-18, have been shown to coimmunoprecipitate with the mouse homolog of ph, Mph, and the mouse homolog of Pc, M33 (3, 17a).

We have undertaken a detailed analysis of potential physical contacts between three PcG members: ph, Psc, and Pc. We show that these three proteins coimmunoprecipitate from nuclear extracts. We have identified and delimited interacting domains by using the two-hybrid system, and we have shown that these interactions are direct by using an in vitro binding assay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subcloning.

We used linker PCR to generate appropriate restriction enzyme sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends of fragments subcloned. PCR products were cut, ligated into pBluescript, and sequenced to confirm the absence of PCR-induced mutations. They were then subcloned into pET28a (Novagen), pGEX4T1 (Pharmacia), and pEG202 and pJG4-5 (16) (provided by Roger Brent). The standard PCR mixture contained the following: 1 μg of template, 0.5 μl of 10-mg/ml acetylated bovine serum albumin (BSA), 5 μl of 10× buffer (New England Biolabs [NEB]), 0.7 μl of 25 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 μl of 100 mM MgSO4, 1 μM each primer, 1 μl (2 U) of Vent polymerase (NEB), and distilled water to make a 50-μl final volume, overlaid with 50 μl of mineral oil. The temperature cycles were as follows: 5 min at 95°C; two cycles of 1 min at 4°C, 1 min at 72°C, and 1 min at 95°C; and seven cycles of 1 min at 45°C, 1 min at 72°C, and 1 min at 95°C.

(i) Templates.

The template cDNAs used for these constructs were as follows: for Pc, Pc-12c (34) (provided by Renato Paro); for ph, c4-11 (11); and for Psc, PscIIIA (6) (provided by Paul Adler).

(ii) Pc.

Primers Pc5 and Pc3 were used to generate the full-length Pc EcoRI-ATG/BamHI fragment. ΔchrPc was created by using the primers Pc208f and Pc3. The minimal chromobox-containing fragment was generated with the primers chr5 and chr3.

(iii) Ph.

An EcoRI site was generated directly upstream of the first ATG of ph by PCR with the primers ph5 and ph255r. This EcoRI/XhoI fragment replaced the 5′ EcoRI/XhoI fragment of c4-11 (full-length proximal ph cDNA). ph contains a BamHI site three codons before the stop codon. ph was subcloned as an EcoRI/BamHI fragment. ph constructs designated ΔN retain amino acids 1 to 1418 and have the 3′ sequence following the NcoI site deleted by NcoI digestion and religation, which liberated an NcoI fragment. Those designated ΔS retain amino acids 1 to 522 and have the 3′ sequence following the first SalI site deleted in the same way. We created phHD by using the primers phD5 and phD3. We created H1 by digesting phHD with NcoI, which liberates 3′ sequence (corresponding to amino acid 1418 and following) as an NcoI fragment, and recircularizing the plasmid.

(iv) Psc.

We used the primers Psc5 and Psc3 to create the EcoRI-ATG/BamHI fragment PscΔB, which contains amino acids 1 to 696. Full-length Psc was created in all subsequent constructs by ligating the BamHI/BamHI fragment from the Psc cDNA into the BamHI site of PscΔB. Psc constructs designated ΔN had the 3′ sequence following the NotI site (corresponding to amino acid 1460) deleted by NotI digestion and religation, which liberated a NotI fragment, and those designated ΔS had the 3′ sequence following the SalI site (corresponding to amino acid 205) deleted in the same way. We created PscHD with the primers Psc748f and Psc1149r, ring with the primers Psc748f and Psc1005r, and HTH with the primers Psc1006f and Psc1149r.

Primers.

The sequences of the primers are as follows: Pc5, 5′-GGAGCGAATTCATGACTGGTCGAGGCAAGG-3′; Pc3, 5′-GGGGGGGATCCCGACATTGTTTGGGTC-3′; Pc208f, 5′-CCCATATGAATTCGACATCTACGAACAAACGAAC-3′; chr5, 5′-CCCATATGAATTCGATCCAGTCGATCTAGTGTAC-3′; chr3, 5′-GTGGGGATCCGATGAGGCGGCGATCCAGGAT-3′; ph5, 5′-GCGAATTCATGGATCGTCGTGCAT-3′; ph255r, 5′-GGCCGCTCGAGCTGCTTGCCACCC-3′; phD5, 5′-CCACGAATTCCCCAAGGCGATGATTAAG-3′; phD3, 5′-GTGGGGATCCTCCTTAATGGACTCCACCTT-3′; Psc5, 5′-GGAGCGAATTCATGATGACGCCAGAATCG-3′; Psc3, 5′-AACGACTTGAGGAACTCCGAC-3′; Psc748f, 5′-CGCATATGGAATTCAGGCCACGCCCCGTCCTTCTA-3′; Psc1149r, 5′-CGCCGGATCCCTGGGGCGACTCATAAACACG-3′; Psc1005r, 5′-GCGGCTCGAGTCATTCCCGTTCGTAAAGGCCCGG-3′; and Psc1006f, 5′-CCGCGAATTCCTGATGCGCAAAAGGGCCTTC-3′.

Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein expression and purification.

pGEX-4T-1 derivative plasmids were transformed into the strain AD202. Single colonies were grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 in 250 ml of L broth at 37°C and induced by the addition of 250 μl of 1 M IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside). Induction was carried out for 15 h at 25°C. The induced cells were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in 15 ml of 20 mM Tris · Cl–100 mM NaCl–1 mg of lysozyme per ml, and left at room temperature for 1 h. Five microliters of β-mercaptoethanol was added, and the resuspended cells were subjected to six cycles of freezing and thawing with liquid N2. The extract was cleared by centrifugation for 40 min at 12,500 rpm (SS34 rotor) at 4°C and filtered through Miracloth.

In vitro coprecipitations.

[35S]methionine-labeled proteins were generated by using the Promega TNT rabbit reticulocyte lysate transcription-translation kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Templates were uncut plasmid DNA. cDNAs with appropriate initiator methionine codons were transcribed by T7 or T3 polymerase from pBluescript constructs, and inserts lacking an initiator methionine were transcribed by T7 polymerase from pET28a (Novagen) constructs which provided the initiator methionine. GST fusion protein-bound glutathione agarose beads were prepared by incubating an aliquot of raw bacterial extract with 50 μl of a 50% slurry of reduced glutathione agarose (Sigma) (in 100 mM NaCl–20 mM Tris · Cl [pH 7.5] [TBS]) in 1 ml of TBS–1% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40)–0.5% phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride-saturated isopropanol for 30 min with gentle rocking at 4°C. The amount of bacterial extract was normalized to give 1 μg of fusion protein in each experimental tube. The bound beads were washed twice in TBS–1% NP-40 and once in TBS. They were then blocked in a solution of 3% BSA in TBS for 30 min at 4°C. The 35S-labeled proteins from the in vitro translation reactions were precleared with the addition of GST-bound glutathione agarose in TBS and incubation at 4°C with gentle rocking for 30 min. For each 200-μl in vitro translation reaction mixture, a 100-μl bed volume of glutathione agarose coupled to 10 μg of GST in a volume of 500 μl was used in the preclearing step. Fifty microliters of precleared lysate and 5 μl of 10% NP-40 (to a 0.1% final concentration) were added to the blocking mixture in each experimental tube, and the tubes were incubated for 30 min at 4°C. The bound beads were washed twice in TBS–0.5% NP-40, twice in 250 mM NaCl–20 mM Tris · Cl (pH 7.5), and once in TBS, followed by elution in 30 μl of TBS–20 mM reduced glutathione (pH 7.5). The eluate was analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), with one-third of the eluate loaded in each experimental lane and 2.5 μl of the prebound lysate loaded in the control lane.

Transformation and culturing of yeast strains.

Yeast strains were grown nonselectively on yeast extract-peptone-dextrose or selected on complete minimal dropout medium lacking uracil, tryptophan, histidine, and leucine. For transformations, 50 ml of fresh yeast culture at an optical density at 600 nm of 1.0 was collected by centrifugation for 5 min at 2,000 rpm at room temperature on a tabletop centrifuge (Clay-Adams) and resuspended in 40 ml of distilled water. Cells were pelleted again and resuspended in 1.5 ml of freshly prepared 100 mM lithium acetate–Tris-EDTA. Two hundred microliters of cells was added to glass tubes containing 1 μg of the plasmid to be transformed plus 200 μg of denatured herring sperm DNA as a carrier. A 1.2-ml amount of polyethylene glycol solution (8 parts sterile 50% polyethylene glycol, 1 part 1 M lithium acetate, 1 part 10× Tris-EDTA) was added, and the tubes were set turning at 30°C for 30 min. A 15-min heat shock at 42°C was applied, and yeast cells were plated directly onto selective plates.

Two-hybrid interaction assay.

Strain EGY48 was transformed with derivatives of plasmids EG202 and JG4-5 (14), encoding the LexA and activator fusion proteins, respectively. Three individual transformed colonies from each plate were streaked out on both dextrose and galactose plates containing complete minimal medium lacking uracil, histidine, and leucine. Growth was scored after 4 days: a strong interaction was deemed to have occurred if the colonies reached 1 mm in diameter. Plates with slower-growing colonies were scored as having weak interactions, and the absence of growth indicated no interaction.

Coimmunoprecipitation from Kc nuclear extracts.

Nuclear extracts were prepared from 2 liters of Kc cells at a cell density of 2 × 106 cells/ml as described by Heberlein et al. (18) and Parker and Topol (33). Antibody to Pc was kindly provided by Jacob Hodgson. Two microliters of preimmune serum was added to 200 μl of nuclear extract and incubated at 4°C with gentle rocking for 30 min. Eighty microliters of a 50% slurry of protein A-Sepharose in HEMG (25 mM HEPES-K+ [pH 7.6], 100 mM KCl, 12.5 MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 15% glycerol, 1.5 mM dithiothreitol) was added, and the tube was rocked for a further 60 min. The beads were removed by centrifugation, and the cleared extract was divided evenly between two tubes containing equal amounts of immunoglobulin G and either 0.5 μl of preimmune serum or 1 μl of affinity-purified anti-Pc antibody. The antibody was bound for 60 min, and 20 μl of 50% protein A beads were added and bound for 30 min. The bound beads were then washed three times in HEMG, eluted with SDS-PAGE loading buffer, run on an 8% gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and blocked in 3% BSA. The filter was then cut into high- and low-molecular weight pieces, and the bottom was probed with the same anti-Pc antibody, while the top was probed with anti-ph (11) and anti-Psc (29).

RESULTS

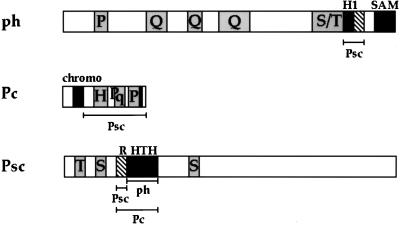

Sequence motifs present in ph, Psc, and Pc.

From the point of view of domain analysis, the three proteins studied have several interesting features (Fig. 1). ph is a tandemly duplicated gene with the proximal and distal transcription units coding for two nearly identical products of 167 and 149 kDa. The proximal ph product has 193 amino-terminal amino acids that are absent from distal ph, and in addition it makes use of internal initiation to give an alternate product shorter by 244 amino acids (19). A notable feature of this unique proximal domain is the presence of a PxxPxxPxxP motif (amino acids 156 to 165) with proline spacing the same as that of the polyproline type II helix recognized by the SH3 domain (50). ph also has many glutamine repeats and a serine/threonine-rich region. Near the carboxyl terminus are two blocks of sequence (amino acids 1297 to 1388 and 1511 to 1576) that are shared with the mammalian ph homologs (3, 15, 32). The first sequence, named H1, consists of 28 highly conserved amino acids followed by an unusual C4 zinc finger with intercysteine spacing Cx2C…Cx3C. The second sequence has been variously referred to as H2 (32) or SEP (3) for the mouse homolog, as SPM for the PcG protein Scm (5) as well as for the human ph homologs HPH1 and HPH2 (15), and as SAM for a variety of yeast signal transduction proteins (38). We have shown that this domain can mediate homotypic and heterotypic self-association between ph and Scm proteins in vitro (25, 36). In view of this result, we refer to the domain in general as a self-association motif and keep the acronym SAM, but we refer to the specific subset of SAMs with greatest similarity to ph and Scm as SPM. The only internal region of sequence dissimilarity between the proximal and distal ph are the 52 amino acids immediately preceding the SPM domain. This work has exclusively used the proximal isoform of ph.

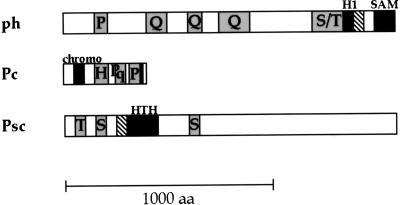

FIG. 1.

Sequence motifs of PcG proteins. Regions of sequence conservation with mammalian homologs are black, zinc and ring fingers are hatched, and regions containing a predominance of a particular amino acid are shaded and labeled with the one-letter designation for that amino acid. aa, amino acids; chromo, chromobox.

Psc is a 170-kDa protein with several stretches of repeated amino acids. Strong similarity to amino acids 261 to 467 of Psc has been found in the Drosophila PcG protein Su(z)2 and the mammalian homologs Bmi-1 (6, 48) and Mel-18 (46). This block of conserved sequence includes a potential C2HC3 ring finger at the amino end and a putative helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif at the carboxyl end. Interestingly, another Drosophila homolog has been cloned, which consists of these two conserved sequences and nothing else (20).

Pc is a 44-kDa protein with two histidine repeats and two proline-rich regions, the first of which partly overlaps with interspersed glutamine repeats. Amino acids 26 to 62 of Pc are conserved with HP1, a Drosophila heterochromatin protein, and the mammalian protein M33 and have been named the chromobox (34, 35). In addition, Pc and M33 share a short sequence near their respective carboxyl termini.

Coimmunoprecipitation of Pc, ph, and Psc.

Most double heterozygous combinations of PcG mutations enhance each other (7). The Psc;Pc enhancement is the strongest nonlethal interaction between PcG mutations. The ph;Psc and ph;Pc combinations are unusual because they display lethality (9), suggesting that direct interactions between these three members may be important in PcG function.

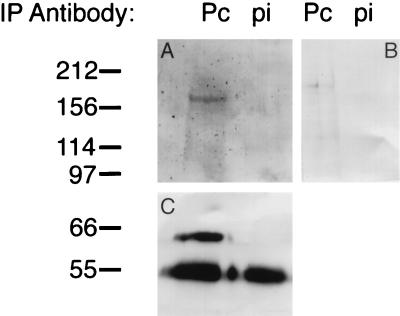

Pc and ph have previously been shown to colocalize on polytene chromosomes and to immunoprecipitate with each other as well as with at least 10 unidentified proteins (13). Given the high level of overlap between the polytene chromosome binding sites of these two proteins with Psc (29, 39) as well as the coimmunoprecipitation of the mammalian homologs of all three proteins (3, 17a), it seemed likely that Psc would complex with ph and Pc in vivo. We therefore performed an immunoprecipitation of a nuclear extract with an antibody to Pc. As shown in Fig. 2, the ph and Psc proteins are both present in the immunoprecipitate of the Pc antibody but are not present in the immunoprecipitate of the preimmune serum. Very recently, the two reciprocal immunoprecipitations have been performed by Strutt and Paro (45), who show that the ph immunoprecipitate contains Psc and that the Psc immunoprecipitate contains ph, completing the circle of interactions.

FIG. 2.

Pc, ph, and Psc proteins coimmunoprecipitate. The nuclear extract immunoprecipitate (IP) of a Pc antibody and its cognate preimmune serum were electrophoresed in two lanes each and electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose filter. The filter was then cut into three pieces, and each was probed with a different antibody. The reconstructed filter is shown. (A) Part probed with ph antibody; (B) part probed with Psc antibody; (C) part probed with Pc antibody. All three proteins are present in the Pc IP but not in the preimmune IP. The large band at 55 kDa is the immunoglobulin G heavy chain of the immunoprecipitating antibody, which reacts with the secondary antibodies. Numbers on the left are molecular masses in kilodaltons.

Two-hybrid interactions.

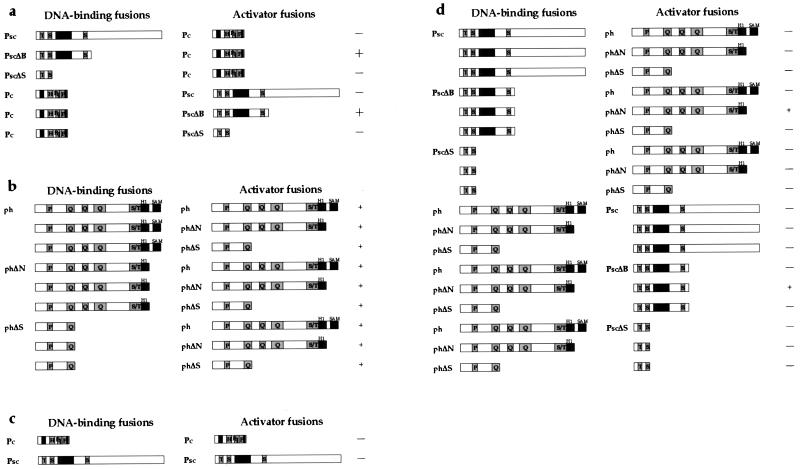

To identify potential direct contacts between the ph, Pc, and Psc proteins, we generated DNA-binding and activator fusions to all three proteins and carboxyl deletion derivatives and tested them for interaction in the yeast two-hybrid system (14). All possible pairwise combinations were tested. Shown in Fig. 3 are the most informative pairs. All pairs not shown were negative. Three interacting combinations were detected: Psc-Pc (Fig. 3a), ph-ph (Fig. 3b), and ph-Psc (Fig. 3d). There were no self-interactions seen for either Pc or Psc (Fig. 3c). The deletion derivatives locate a ph-ph interacting region in the amino-terminal 522 amino acids, although we have recently demonstrated that ph also has a carboxyl-terminal self-interacting domain (25, 36). The ph-Psc interacting domains were mapped to between amino acids 523 and 1418 of ph and to between amino acids 205 and 696 of Psc. This interaction occurred with deleted versions of each protein but not with the full-length proteins. The Psc-Pc interaction also mapped to amino acids 205 to 696 of Psc and was similarly not observed with full-length Psc.

FIG. 3.

Two-hybrid interaction assay results for ph, Psc, Pc, and carboxyl-deletion mutants. DNA-binding fusions represent protein fusions to LexA, a bacterial DNA-binding protein, and activator fusions represent protein fusions to B42, a short acidic transactivation sequence. All pairwise combinations were tested. Combinations not shown were negative. Strong interactions (1-mm-diameter colonies after 4 days of growth on selective medium) are indicated by a large plus, and weak interactions (<1-mm-diameter colonies after four days) are indicated by a small plus. Shadings are as described for Fig. 1. (a) Psc interacts with Pc; however, full-length Psc must be deleted for this interaction to be seen. (b) ph interacts with itself through a domain or domains in the smallest amino-terminal construct. (c) Self-interactions were not seen with either Pc or Psc. (d) Psc interacts with ph, and this interaction requires carboxyl deletions of both proteins to be detected.

Because all of the interactions mapped to areas that contained sequence similarity to mammalian homologs, we generated DNA-binding and activator fusions to these regions alone and tested these against each other and the previous panel of constructs (Fig. 4). The smallest fragment of ph to interact with Psc was the H1 domain, amino acids 1297 to 1418. The minimal Psc element required for the same interaction was the HTH fragment, amino acids 336 to 473. The minimal domains interacted with each other and are therefore sufficient. DNA-binding fusions to both phHD (amino acids 1297 to 1576) and the subfragment H1 activated transcription alone as assayed by their ability to promote growth on leucine-deficient medium in the absence of any other plasmid. It was therefore impossible to test these domains reciprocally. However, by using the phΔN construct (amino acids 1 to 1417), which contains the H1 domain and does not activate transcription alone, we could demonstrate reciprocity for the HTH domain of Psc. An interesting modulating effect was noted with the SPM domain of ph (amino acids 1511 to 1576): when the SPM domain was present in a construct, the interaction with Psc was weaker or, as shown in Fig. 3d, absent.

FIG. 4.

Two-hybrid interaction assay results for conserved sequence constructs. (a) Psc-ph interacting constructs. The interaction is delimited to the H1 domain of ph and the HTH-containing region of Psc. It is stronger in the absence of the SPM domain of ph. (b) Psc-Psc interacting constructs. This interaction was seen only with the isolated domains and was dependent on the ring finger. (c) Psc-Pc interacting constructs. The interaction appears to be dependent on sequences carboxyl to the chromobox (chromo) of Pc and the HTH-containing region of Psc, although an interaction is seen with the ring finger in one pair. Shadings are as described for Fig. 1.

The domain of Pc required for the interaction with Psc was shown to reside in the 320 amino acids C terminal to the chromobox (Fig. 4c) (referred to as ΔchrPc). Surprisingly, the chromobox was not required for this interaction, nor did it or ΔchrPc show interactions with any Pc construct or with any ph construct from the panel (not shown). The Psc domain required for the Pc interaction was also located within the region of amino acid conservation. Minimally, the HTH domain showed interaction with Pc both as a DNA-binding fusion and as an activator fusion. The ring finger of Psc showed weak interaction with the activator fusion of ΔchrPc. This may mean that although Pc makes contacts primarily with the HTH domain, it also makes weaker contacts with the ring finger domain.

When expressed in the absence of surrounding sequence, the ring finger of Psc dimerized (Fig. 4b). This was surprising, as dimerization of Psc had not been observed with any larger construct. A weak interaction between the ring finger construct and the HTH domain was seen in one orientation but not the other. This interaction may occur simply because these domains fit together naturally in the tertiary structure of the protein, or it may be part of a true Psc dimerization domain.

Caution should be used in relating the strength of interactions seen in the two-hybrid system with presumed affinities of individual proteins for one another. Two-hybrid analysis done with interactors of known affinities has shown that while interaction strength generally correlates with in vitro affinity, the response curve is not linear, and in many cases it shows a threshold below which no response is seen (12).

In vitro interactions.

The two-hybrid interaction assay takes place within the yeast nucleus. Because PcG proteins are transcriptional repressors, this environment is likely very close to their natural environment. However, for the same reason it may also contain confounding influences. Any of these interactions could be mediated by an endogenous yeast nuclear protein with enough similarity to the Drosophila protein that actually functions as the mediator; hence, the observed interaction may not be direct. Likewise, there may exist yeast proteins capable of interacting with the Drosophila fusion proteins, which would occlude or prevent their interaction with each other. We therefore sought to test the identified interactions in vitro. Interacting proteins and domains were subcloned into pGEX4T-1 for bacterial GST fusion protein expression and into pET28a for T7 transcription and in vitro translation in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate. The T7 constructs were translated in the presence of 35S-labeled methionine and incubated with GST fusion protein immobilized on glutathione agarose. Bound protein was then washed extensively, eluted with reduced glutathione, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and autoradiographed.

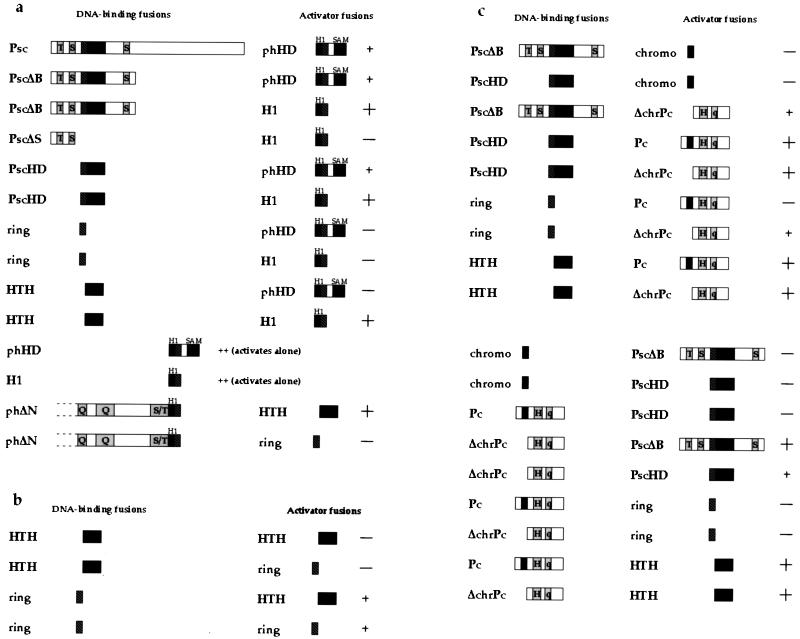

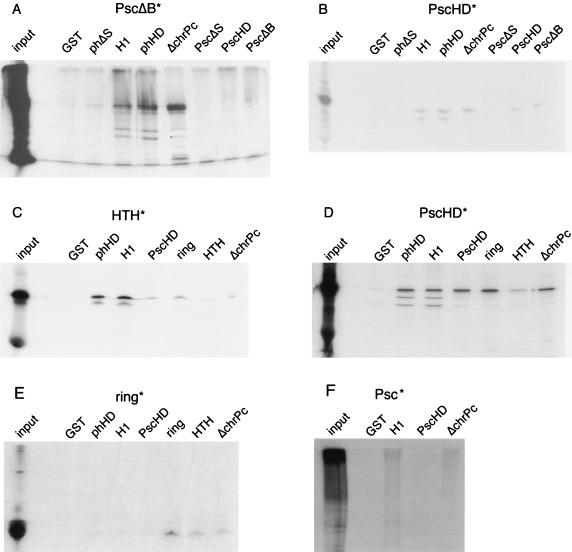

The construct PscΔB (amino acids 1 to 696), originally implicated in the two-hybrid interaction, was shown to interact specifically both with the minimal H1 domain of ph and with phHD (amino acids 1297 to 1576), the larger construct which contains the H1 domain and the SPM domain. It also bound the chromobox-deleted Pc fusion. However, it did not bind a ph construct that does not contain H1, nor did it bind any Psc construct or GST alone (Fig. 5A). These data corroborate the two-hybrid data. The construct PscHD (amino acids 250 to 473), which contains only the conserved sequences of Psc (the ring finger followed by the HTH-containing region), showed similar behavior, although a new interaction with itself was detected (Fig. 5B). When the homology region was broken into the ring finger and the HTH domain, the HTH domain interacted with H1, while weaker interactions were seen between the HTH and Pc as well as between HTH and ring finger-containing constructs (Fig. 5C). The ring finger did not interact with H1 but did show an interaction with itself and a weaker interaction with Pc and the HTH (Fig. 5E). Full-length Psc interacted with both H1 and chromobox-deleted Pc (Fig. 5F), recapitulating the behavior of PscΔB.

FIG. 5.

In vitro binding of reticulocyte lysate-generated 35S-labeled Psc constructs to bacterially produced GST fusions. (A) Labeled PscΔB (amino acids 1 to 696) binds to GST fusions to regions of ph which contain H1 (amino acids 1297 to 1418) and to a GST fusion of Pc with the chromobox deleted. It does not bind phΔS (amino acids 1 to 522 of ph) or other Psc constructs. (B) Labeled PscHD (amino acids 250 to 473) bind the same GST fusions as well as GST fusions containing amino acids 250 to 473 of Psc. (C) The Psc HTH-containing region (amino acids 336 to 473) binds H1-containing ph constructs strongly and Pc and Psc constructs weakly. (D) PscHD (amino acids 250 to 473) binds as strongly to the ring finger alone (amino acids 250 to 335) as it does to the ring finger plus the HTH region and binds only weakly to the HTH. (E) The ring finger of Psc binds to itself and also more weakly to Pc and the HTH. (F) Labeled full-length Psc binds GST fused to phH1 (amino acids 1297 to 1418) and to the GST fusion of Pc with the chromobox deleted but not to PscHD (amino acids 250 to 473).

In the translation of HTH-containing constructs of Psc, we observed smaller labeled fragments most likely derived from weak internal initiation or possibly from breakdown of the full-length products (Fig. 5A to D). These bound to H1-containing constructs but not to Pc. We interpret this as evidence that ph and Pc bind to different regions of PscHD. Furthermore, while H1-containing GST fusions strongly bound both PscHD and the HTH domain, Pc strongly bound only the complete PscHD and more weakly bound both the HTH and the ring finger. This is further evidence that Pc makes use of an interaction surface different from that used by ph and that this interaction surface is likely made up of elements from both the ring finger and the HTH. The self-interaction of PscHD required the ring finger (Fig. 5D) and was not seen with the larger construct PscΔB.

The amount of sample loaded in each experiment was such that a bound band with intensity equal to that of the input band represents approximately 10% of input labeled protein remaining bound through multiple wash steps of increasing stringency and eluting with reduced glutathione. By comparing the relative intensities of bound band to input band between experiments, the most stable association under these conditions is seen to be between the labeled HTH fragment and ph constructs containing the H1 domain. This level of bound to input protein is similar to that seen in experiments with the SPM domain interactions of ph and Scm (36).

DISCUSSION

We have tested three PcG proteins, ph, Pc, and Psc, for interaction with each other in the yeast two-hybrid system, in an in vitro protein-binding assay, and by immunoprecipitation. The results suggest that a nuclear protein complex or complexes exist in which Psc makes contacts with both ph and Pc. The in vitro results corroborate the two-hybrid results and limit the interactions to specific domains (Fig. 6). The interaction between ph and Psc is mediated by the H1 domain of ph (amino acids 1297 to 1418) and the HTH domain of Psc (amino acids 336 to 473). The interaction between Psc and Pc does not require the chromobox of Pc and is likely mediated by contacts with both the HTH domain (amino acids 336 to 473) and the ring finger (amino acids 250 to 335) of Psc.

FIG. 6.

Domains involved in interactions between Pc, ph, and Psc. Psc interactions occur through amino acids 1297 to 1418 of ph, 70 to 390 of Pc, and 250 to 335 of Psc. A ph interaction occurs through amino acids 336 to 473 of Psc. A Pc interaction occurs through amino acids 250 to 473 of Psc. Shadings are as described for Fig. 1. chromo, chromobox.

Independently, the coimmunoprecipitation and domain analysis are consistent with either a ternary complex or multiple binary complexes; however, a ternary complex seems more likely, considering the data together. Our coimmunoprecipitation demonstrates the existence of protein complexes containing Pc-ph and Pc-Psc, while the domain analysis gives evidence only for the direct interactions between Pc-Psc and ph-Psc. A ternary complex with Psc as the bridge explains both sets of data. Alternatively, a direct Pc-ph interaction may have eluded our assays or may be mediated by another, unidentified protein in the nuclear extract.

Isolated domain interactions were modulated by external sequences.

In our domain analysis, some interactions were affected by parts of the proteins not implicated in binding. In the case of the ph-Psc interaction, the presence of the ph SPM domain weakened the interaction in most two-hybrid combinations, although not in the in vitro assay. Since the SPM domain has the potential for heterologous self-association, and since yeast proteins with this domain exist (38), the modulation might be an artifact of ph interacting with endogenous yeast proteins. In Drosophila there are at least two nuclear proteins that contain the SPM domain: Scm (5) and 1(3)mbt (49). Whether the Scm-ph interaction affects the ph-Psc interaction is an open question. The two-hybrid interactions were also attenuated by full-length Psc. We believe this may be due to the ability of full-length Psc to repress transcription in yeast (25a). Consistent with this, the full-length protein does interact with the expected domains of ph and Pc in the in vitro assay.

The greatest inconsistency between the two-hybrid results and the in vitro results was seen with the Psc-Psc interaction. In the two-hybrid system, self-interactions were seen only with the isolated ring finger domain. In vitro, self-interactions were seen with the ring finger and with the complete conserved region which includes the ring finger, but not with larger constructs. The most likely reason for the discrepancy is the fact that these assays employ proteins produced from three different sources: yeast cells, bacterial cells, and a reticulocyte lysate. A protein expressed in a heterologous system will not necessarily have the same folding and covalent modifications as its native cognate. A given domain may be prevented by its expression context from attaining the folding or covalent modifications required for interaction. The fact that large parts of Psc from outside the homology domain prevent the self-interaction may mean that the interaction is spurious, an artifact of the isolation of individual domains, or that dimerization is cryptic and normally modulated by other parts of Psc, with dimerization happening only under certain conditions, such as binding to DNA or binding to other PcG proteins.

Interactions of the vertebrate homologs of Psc, Pc, and ph.

Our results are similar in general but differ in detail from those reported for the various mammalian homologs of ph and Psc. Although the isolated Mph H1 domain and Bmi-1 HTH domain were not tested with each other, the presence of both H1 and the SPM domain of Mph was required for the interaction with Bmi-1 (3), leading those authors to speculate that Mph dimerization was a prerequisite for Bmi-1 binding. We do not see such a requirement for ph binding to Psc. The issue is complicated by the fact that besides Psc, there are two other ring-HTH-containing proteins in the fly, Su(z)2 (6, 48) and L(3)Ah (20), and at least one other in the mouse, Mel-18 (46). The mammalian complex members may truly behave differently from their fly cognates, or perhaps Mel-18 and not Bmi-1 is the functional homolog of Psc.

In this work, the Psc-Pc interaction was seen with both the ring finger and the HTH domains of Psc. Alkema et al. (3) did not see a two-hybrid interaction between the mouse homologs, Bmi-1 and M33. However, Hashimoto et al. (17a) have reported observing such an interaction with an in vitro binding assay similar to that used in this work, and in one orientation in the two-hybrid system, and show that the HTH domain-containing region is required. The Xenopus homologs, XPsc and XPc, have been shown to interact with each other; however, this interaction was shown not to require the HTH domain of XPsc (40), requiring instead the 188 upstream amino acids which contain the ring finger. While these differences may reflect true differences between fly, frog, and mouse, given the sequence conservation of these domains, it is more likely that the differences arise from differences in the assays, specifically in the sizes and imprecise overlap of the constructs used. Since we have seen interactions with both the ring finger and the HTH-containing regions in both two-hybrid and in vitro assays, we speculate that Pc primarily contacts the HTH-containing region but also contacts the ring finger domain weakly. Alternatively, Pc may contact the region between the ring finger and the HTH domain proper, and some level of binding to each half is seen even when this region is divided. Pc and XPc differ also in their observed self-affinities: Reijnen et al. (40) reported that full-length XPc was able to interact with both its amino terminus and its carboxyl terminus, whereas we see no Pc-Pc self-interaction.

It has been shown that full-length Mel-18 has the ability to bind DNA, whereas a deleted version of Mel-18 lacking the ring finger does not (46). It is possible that Psc also has this ability, and it would be interesting to know whether the binding of ph and Pc, so close to and perhaps directly on the putative DNA-binding domain, would influence the putative DNA-binding properties of Psc.

Role of multiple interacting domains in PcG complexes.

Using a formaldehyde cross-linking assay, Strutt and Paro (45) have recently shown that the compositions of PcG complexes are not the same at all target loci. The partially but not completely overlapping patterns of PcG protein binding to polytene chromosomes also suggest PcG complexes that are heterogeneous in composition, being different at different target sites. The interaction domains that we have described may facilitate this heterogeneity. Psc has a domain with the ability to bind either ph or Pc, or perhaps both, while ph has two very distinct domains with the ability to bind Psc on the one hand and ph or Scm (36) on the other. These interaction domains make possible multiple protein contacts, not all of which necessarily occur at every site. By allowing different complexes to form at different sites, more complex regulation of target genes is permitted.

All of the conserved sequences of ph and Psc have now been shown to function as protein-binding domains. This raises the question of what purpose the nonconserved sequence, which forms the vast majority of these proteins, serves. A putative complex involving only a single copy each of ph, Scm, Psc, and Pc would be on the order of 0.5 MDa, although the interacting amino acid sequences would account for less than 80 kDa. One possibility is that the nonconserved sequence has a direct transcriptional repression function that is conserved in the absence of sequence conservation. An alternative is that transcriptional repression is an indirect result of the bulk of the protein complex, which either excludes transcriptional activators from the vicinity of their binding sites or prevents their interaction with the basal transcription machinery. If this were the case, the PcG proteins could be described as very large molecules with small domains that can interact with each other promiscuously, allowing bulky heterogeneous complexes to form at their various sites of action.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge P. Adler and J. Hodgson for the provision of antibodies and R. Brent and R. Finlay for two-hybrid plasmids.

This work was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council of Canada to H.W.B. and by an NSERC postgraduate fellowship to M.K.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler P N, Charlton J, Brunk B. Genetic interactions of the Suppressor 2 of zeste region genes. Dev Genet. 1989;10:249–260. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020100314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akasaka T, Kanno M, Balling R, Mieza M A, Taniguchi M, Koseki H. A role for mel-18, a Polycomb group-related vertebrate gene, during the anteroposterior specification of the axial skeleton. Development. 1996;122:1513–1522. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkema M J, Bronk M, Verhoeven E, Otte A, van’t Veer L J, Berns A, van Lohuizen M. Identification of Bmi1-interacting proteins as constituents of a multimeric mammalian Polycomb complex. Genes Dev. 1997;11:226–240. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkema M J, van der Lugt N M T, Bobeldijk R C, Berns A, van Lohuizen M. Transformation of axial skeleton due to overexpression of bmi-1 in transgenic mice. Nature. 1995;374:724–727. doi: 10.1038/374724a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bornemann D, Miller E, Simon J. The Drosophila Polycomb group gene Sex comb on midleg (Scm) encodes a zinc finger protein with similarity to polyhomeotic protein. Development. 1996;122:1621–1630. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brunk B P, Martin E C, Adler P N. Drosophila genes Posterior sex combs and Suppressor two of zeste encode proteins with homology to the murine bmi-1 oncogene. Nature. 1991;353:351–353. doi: 10.1038/353351a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell R B, Sinclair D A R, Couling M, Brock H W. Genetic interactions and dosage effects of Polycomb group genes of Drosophila. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;246:291–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00288601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrington E A, Jones R S. The Drosophila Enhancer of zeste gene encodes a chromosomal protein: examination of wild-type and mutant protein distribution. Development. 1996;122:4073–4083. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.4073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng N N, Sinclair D A R, Campbell R B, Brock H W. Interactions of polyhomeotic with Polycomb group genes of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1994;138:1151–1162. doi: 10.1093/genetics/138.4.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coré N, Bel S, Gaunt S J, Aurrand-Lions M, Pearce J, Fisher A, Djabali M. Altered cellular proliferation and mesoderm patterning in Polycomb-M33-deficient mice. Development. 1997;124:721–729. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.3.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeCamillis M A, Cheng N, Pierre D, Brock H W. The polyhomeotic gene of Drosophila encodes a chromatin protein that shares polytene chromosome binding sites with Polycomb. Genes Dev. 1992;6:223–232. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estojak J, Brent R, Golemis E A. Correlation of two-hybrid affinity data with in vitro measurements. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5820–5829. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franke A, DeCamillis M A, Zink D, Cheng N, Brock H W, Paro R. Polycomb and polyhomeotic are constituents of a multimeric protein complex in chromatin of Drosophila melanogaster. EMBO J. 1992;11:2941–2950. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05364.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golemis E A, Gyuris J, Brent R. Two hybrid systems/interaction traps. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R, Moore D, Seidman J, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1993. pp. 13.14.1–13.14.17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunster M J, Satijn D P E, Hamer K M, den Blaauwen J L, de Bruijn D, Alkema M J, van Lohuizen M, van Driel R, Otte A P. Identification and characterization of interactions between the vertebrate Polycomb-group protein BMI1 and human homologs of Polyhomeotic. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2326–2335. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gyuris J, Golemis E, Chertkov H, Brent R. Cdi1, a human G1 and S phase protein phosphatase that associates with Cdk2. Cell. 1993;75:791–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90498-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harding K, Levine M. Gap genes define the limits of Antennapedia and bithorax gene expression during early development in Drosophila. EMBO J. 1988;7:205–214. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02801.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17a.Hashimoto, N., H. W. Brock, M. Nomura, M. Kyba, J. Hodgson, Y. Fujita, Y. Takihara, K. Shimada, and T. Higashinakagawa. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Heberlein U, England B, Tjian R. Characterization of Drosophila transcription factors that activate the tandem promoters of the alcohol dehydrogenase gene. Cell. 1985;41:965–977. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodgson J W, Cheng N N, Sinclair D A R, Kyba M, Randsholt N B, Brock H W. The polyhomeotic locus of Drosophila melanogaster is transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally regulated during embryogenesis. Mech Dev. 1997;66:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00091-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irminger-Finger I, Nöthiger R. The Drosophila melanogaster gene lethel(3)Ah encodes a ring finger protein homologous to the oncoproteins MEL-18 and BMI-1. Gene. 1995;163:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones R S, Gelbart W M. Genetic analysis of the Enhancer of zeste locus and its role in gene regulation in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1990;126:185–199. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jurgens G. A group of genes controlling the spatial expression of the bithorax complex in Drosophila. Nature. 1985;316:153–155. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufman T C, Lewis R A, Wakimoto B T. Cytogenetic analysis of chromosome 3 in Drosophila melanogaster: the homeotic gene complex in polytene chromosome interval 84A-B. Genetics. 1980;94:115–133. doi: 10.1093/genetics/94.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennison J A, Russell M A. Dosage-dependent modifiers of homeotic mutations in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1987;116:75–86. doi: 10.1093/genetics/116.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kyba M, Brock H. The SAM domain of Polyhomeotic, RAE28, and Scm mediates specific interactions through conserved residues. Dev Genet. 1998;22:74–78. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1998)22:1<74::AID-DVG8>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25a.Kyba, M. Unpublished data.

- 26.Lewis E B. A gene complex controlling segmentation in Drosophila. Nature. 1978;276:565–570. doi: 10.1038/276565a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Locke J, Kotarski M A, Tartof K D. Dosage-dependent modifiers of position-effect variegation in Drosophila and a mass action model that explains their effect. Genetics. 1988;120:181–198. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lonie A, D’Andrea R, Paro R, Saint R. Molecular characterisation of the Polycomblike gene of Drosophila melanogaster, a trans-acting negative regulator of homeotic gene expression. Development. 1994;120:2629–2636. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.9.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin E C, Adler P N. The Polycomb group gene Posterior sex combs encodes a chromosomal protein. Development. 1993;117:641–655. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.2.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKeon J, Brock H W. Interactions of the Polycomb group of genes with homeotic loci of Drosophila. Arch Dev Biol. 1991;199:387–396. doi: 10.1007/BF01705848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muller J, Gaunt S, Lawrence P A. Function of the Polycomb protein is conserved in mice and flies. Development. 1995;121:2847–2852. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.9.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nomura M, Takihara Y, Shimada K. Isolation and characterization of retinoic acid-inducible cDNA clones in F9 cells: one of the early inducible clones encodes a novel protein sharing several highly homologous regions with a Drosophila polyhomeotic protein. Differentiation. 1994;57:39–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.1994.5710039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker C, Topol J. A Drosophila RNA polymerase II transcription factor contains a promoter-region-specific DNA-binding activity. Cell. 1984;36:357–369. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paro R, Hogness D S. The Polycomb protein shares a homologous domain with a heterochromatin-associated protein in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:263–267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.1.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pearce J H H, Singh P B, Gaunt S J. The mouse has a Polycomb-like chromobox gene. Development. 1992;114:921–929. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.4.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson A, Kyba M, Borneman D, Morgan K, Brock H, Simon J. A domain shared by the Polycomb group proteins Scm and ph mediates heterotypic and homotypic interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6683–6692. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phillips M D, Shearn A. Mutations in polycombeotic, a Drosophila Polycomb group gene, cause a wide range of maternal and zygotic phenotypes. Genetics. 1990;125:91–101. doi: 10.1093/genetics/125.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ponting C P. SAM: a novel motif in yeast sterile and Drosophila polyhomeotic proteins. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1928–1930. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rastelli L, Chan C S, Pirrotta V. Related chromosome binding sites for zeste, suppressor of zeste and Polycomb group protein and their dependence on Enhancer of zeste function. EMBO J. 1993;12:1513–1522. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reijnen M J, Hamer K M, den Blaauwen J L, Lambrechts C, Schoneveld I, van Driel R, Otte A P. Polycomb and bmi-1 homologs are expressed in overlapping patterns in Xenopus embryos and are able to interact with each other. Mech Dev. 1995;53:35–46. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon J, Chiang A, Bender W. Ten different Polycomb group genes are required for spatial control of the abd-A and Abd-B homeotic products. Development. 1992;114:493–505. doi: 10.1242/dev.114.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soto M C, Chou T-B, Bender W. Comparison of germ-line mosaics of genes in the Polycomb group of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1995;140:231–243. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.1.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Struhl G, Akam M E. Altered distribution of Ultrabithorax transcripts in extra sex combs mutant embryos of Drosophila. EMBO J. 1985;4:3259–3264. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Struhl G, Brower D. Early role of the esc+ gene product in the determination of segments in Drosophila. Cell. 1982;31:285–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90428-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strutt H, Paro R. The polycomb group protein complex of Drosophila melanogaster has different compositions at different target genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6773–6783. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tagawa M, Sakamoto T, Shigemoto K, Matsubara H, Tamura Y, Ito T, Nakamura I, Okitsu A, Imai K, Taniguchi M. Expression of novel DNA-binding protein with zinc finger structure in various tumor cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20021–20026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Lugt N M T, Alkema M J, Berns A, Deschamps J. The Polycomb-group homologue Bmi-1 is a regulator of murine Hox expression. Mech Dev. 1996;58:153–164. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00570-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Lohuizen M, Frasch M, Wientjens E, Berns A. Sequence similarity between the mammalian bmi-1 proto-oncogene and the Drosophila regulatory genes Psc and Su(z)2. Nature. 1991;353:353–355. doi: 10.1038/353353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wismar J, Loffler T, Habtermichael N, Vef O, Geissen M, Zirwes R, Altmeyer W, Sass H, Gateff E. The Drosophila melanogaster tumor suppressor gene lethal(3)malignant brain tumor encodes a proline-rich protein with a novel zinc finger. Mech Dev. 1995;53:141–154. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yu H, Chen J K, Feng S, Dalgarno D C, Brauer A W, Schreiber S L. Structural basis for the binding of proline-rich peptides to SH3 domains. Cell. 1994;76:933–945. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]