Abstract

Background:

Veterans Affairs (VA) implemented the Veteran-centered Whole Health System initiative across VA sites with approaches to implementation varying by site.

Purpose:

Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), we aimed to synthesize systemic barriers and facilitators to Veteran use with the initiative.

Relevance to healthcare quality:

Systematic comparison of implementation procedures across a national healthcare system provides a comprehensive portrait of strengths and opportunities for improvement.

Methods:

Advanced fellows from eleven VA Quality Scholars sites performed the initial data collection and the final report includes CFIR-organized results from six sites.

Results:

Key innovation findings included cost, complexity, offerings, and accessibility. Inner setting barriers and facilitators included relational connections and communication, compatibility, structure and resources, learning-centeredness, and information and knowledge access. Finally, results regarding individuals included innovation deliverers, implementation leaders and team, and individual capability, opportunity, and motivation to implement and deliver whole health care.

Discussion and implications:

Examination of barriers and facilitators suggest that Whole Health coaches are key components of implementation and help to facilitate communication, relationship-building, and knowledge access for Veterans and VA employees. Continuous evaluation and improvement of implementation procedures at each site is also recommended.

Keywords: Whole Health, Veterans Affairs, Quality Improvement, CFIR

Introduction

In 2011, the Whole Health System initiative was launched by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), also known as the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), to transform Veteran care. This initiative shifts the VHA model of care from disease- to whole person-focused, prioritizing Veterans’ personal well-being and goals using complimentary and integrative therapies.1,2 This transformational care shift is uniquely challenging for the VHA, the largest integrated healthcare system in the United States. The 171 Veterans Affairs medical centers (VAMCs) have diverse infrastructures and variable clinical complexity, complicating implementation of a new system-wide care approach.3 The extent to which this variation can be attributed to site-specific contextual factors versus VHA system barriers and facilitators is unknown.4,5

Background

Veterans experience considerable physical and psychosocial health struggles (e.g., chronic pain, PTSD; unhoused status), necessitating a new model of care.7–9 In 2016, President Obama signed the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act to address the opioid epidemic, resulting in the Whole Health initiative.6 This initiative is an evidence-based healthcare approach with the mission to provide preventative and patient-centered care.5 The initiative includes three core components: 1) the completion of a Personalized Health Inventory and Plan (PHI/PHP) to promote goal-aligned care, 2) Well-being programs and classes to holistically optimize health, and 3) complimentary and integrative health (CIH) therapies for chronic pain management, contributing to improved patient outcomes and reduced costs.10–12

From 2017 to 2020, the VHA instituted a pilot project to integrate this initiative across Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISN). Each of the 18 VISNs selected and financially supported a Flagship VAMC to implement the initiative within the current institutional structure. Non-flagship VAMCs had fewer resources, but all sites were required to implement all Whole Health components with variable support.5,12,13 Successful implementation included integration of the core Whole Health components, but each site determined the process and extent of integration, resulting in variable service availability and access to this new initiative. Implementation barriers included insufficient institutional resources, low maintenance of continuous learning opportunities, a lack of leadership support, and unstandardized evaluation metrics.14 Since the widespread COVID-19 crisis management, there is a need to provide an updated assessment of implementation barriers and facilitators to Veteran Whole Health use. As implementation concepts are multi-faceted, we used the updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) for analysis.

CFIR is a comprehensive and systematic framework that integrates implementation determinants from several frameworks.15,16 CFIR is one of the most cited implementation research frameworks and has been identified as a particularly useful framework in complex and dynamic healthcare environments (e.g., Veteran Whole Health use across Flagships).17

Purpose and Design

As part of ongoing process improvement across sites, this project represents the “study” phase of the plan-do-study-act quality improvement (QI) cycle, whereby previous project change actions are evaluated for influence on outcomes of interest.18 While we did not implement Whole Health at each site, we aimed to qualitatively and systematically synthesize implementation barriers and facilitators to Veteran use to inform future QI and research efforts.

Methods

Context

The national VA Quality Scholars (VAQS) program is an interprofessional, 2-year Advanced Fellowship focused on leadership and healthcare improvement and funded by the VHA Office of Academic Affiliations.19–22 The VAQS program is a pre/post-doctoral fellowship that trains early career scholars to perform high-quality quality improvement, lead interdisciplinary teams, and learn implementation science approaches.19 Faculty select scholars after intensive interviews to assess qualifications and program alignment with each applicant’s scholarly interests.

As part of the national curriculum, 37 first-year Advanced Fellows across 11 diverse U.S. institutions identified how Veterans use Whole Health at each respective institution. Veteran “use” consists of Veteran interaction with any of the Whole Health core components. The project prompted a process mapping of Veteran Whole Health use within a single primary care clinic, provided examples of interview questions and provider types to interview, and details to report (supplementary material). The VAQS fellows presented the local site context, a process map, barriers and facilitators, and recommendations for improvement. This report focuses on synthesizing the barriers and facilitators using the updated CFIR and is reported in accordance with SQUIRE guidelines.23

Study of the Whole Health System

In July of 2021, first-year scholars worked with VA leadership, VAQS faculty, and returning scholars to develop individualized interview guides, identify potential stakeholders to interview, conduct interviews, and rapidly analyze and report findings. Scholars interviewed stakeholders across a spectrum of Whole Health roles (clinical providers and support staff, implementation team members, and Whole Health providers and coaches) about the initiative rollout and Veteran use at each institution. Scholars conducted interviews over Zoom or in-person, took detailed notes, and synthesized findings at the site level. Interviews were not recorded or transcribed.

Materials

Each site designed a distinct and individual qualitative interview guide to assess Veteran Whole Health use. Each site customized their interview guides from a standardized list of questions (See Supplemental material). Questions included: “How are providers educated about the WHS Program?” and “What is the process that leads to Veterans using Whole Health?” Prompts and probes were added to more fully understand barriers and facilitators that affected Veteran use and provider participation.

Analysis and Theoretical Model

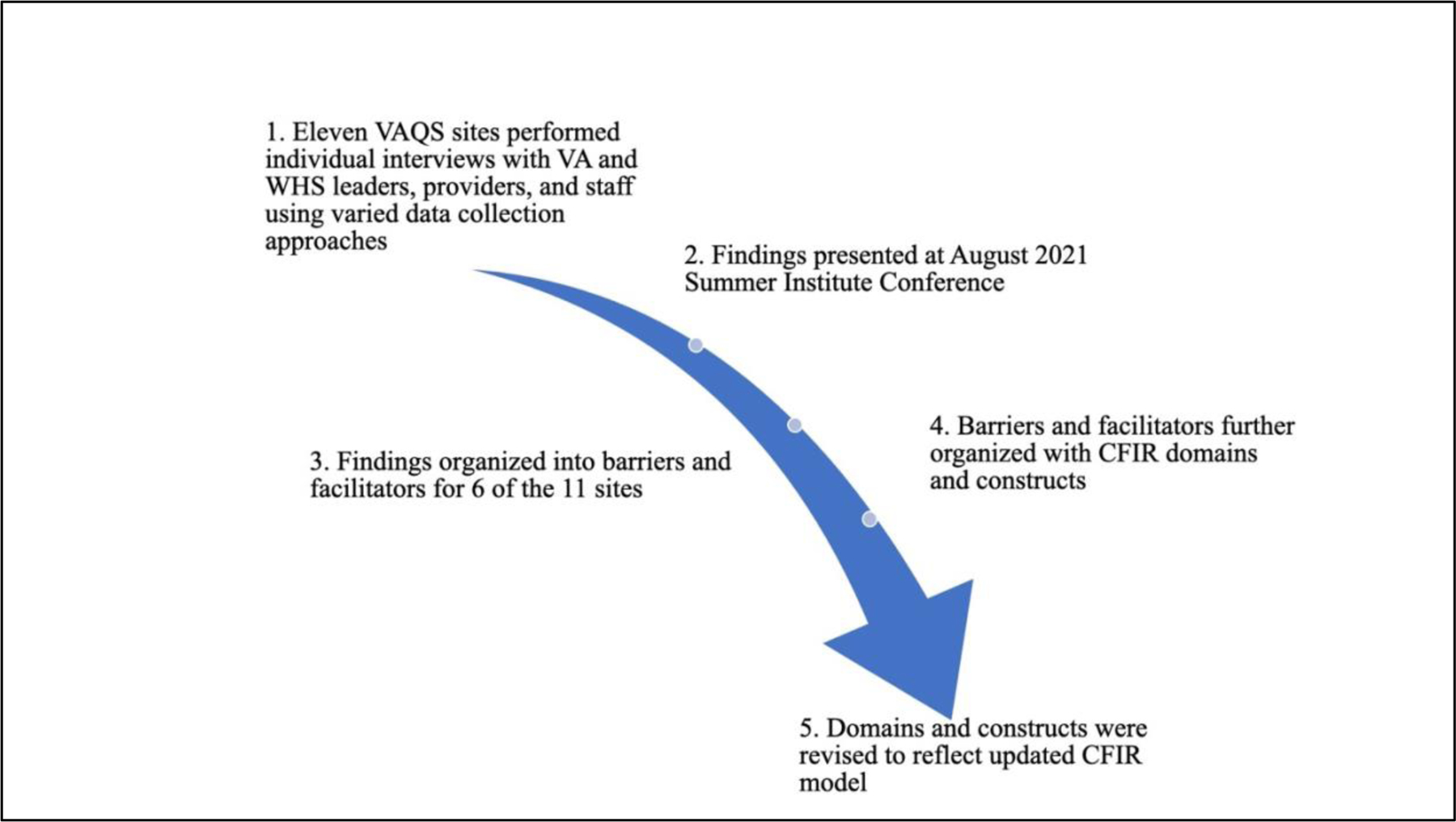

Data collection, presentation, and continued analysis followed four phases (Figure 1). Initially, each of the 11 sites individually collected and analyzed data. Scholars from six of the 11 sites were available to participate in continued analysis at the national level and contribute to this report. Teams reviewed interview notes, listed initial barriers and facilitators across individual interviews, and refined key themes through iterative review cycles (Microsoft Word and Excel). For this report and additional analysis, we used a matrix to categorize barrier and facilitator themes by CFIR construct (column) and site (row) (Microsoft Excel).15,16 The authors engaged in three consensus-seeking meetings to iteratively refine and synthesize themes. These themes were subsequently revised to reflect updated CFIR constructs where applicable.16

Figure 1. Data Collection and Analysis Process.

This process details the process of each individual site collecting data and subsequently six of the eleven sites synthesizing the data using the updated CFIR domains.

Ethical considerations

The home institution considered this project to be QI and did not require Institutional Review Board review.

Results

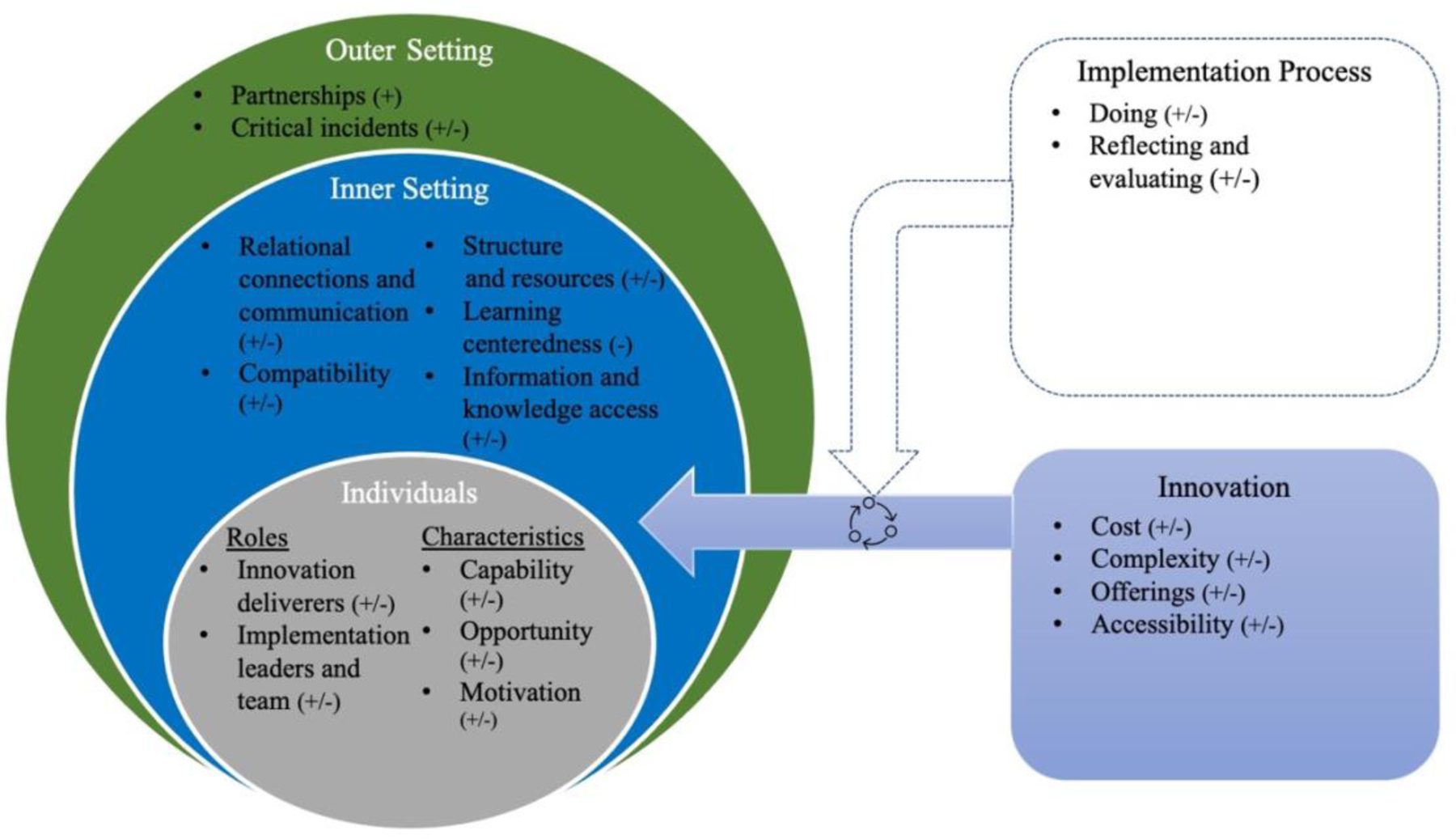

Results are presented according to the updated CFIR domains and constructs, which were adapted and defined in Table 1. Six VAQS sites contributed Whole Health data. Four of the VAs were located in urban settings (66.6%). Half of the VAs resided in the southeast and the other half in the Mid-West region. City populations of the VAs ranged from 24,569 to 692,587 people. Three VAs had less than 300 beds and three exceeded 600 beds. Although data were categorized using all five CFIR domains, we discuss key constructs from three domains to reflect the most prominent findings: Innovation, Inner Setting, and Individuals. Findings from individual sites for all five updated CFIR domains are presented in Table 2 and depicted in Figure 2, which illuminates constructs that aligned with our data and the presence of barriers (−) and/or facilitators (+).

Table 1.

Adapted Updated CFIR Model Domains and Construct Definitions

| Domain and Domain Definition | Construct | Construct Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation– the Whole Health System features implemented at each site as the “thing” that is being implemented | Cost | The expense and funding needed to implement, deliver, and maintain the WHS innovation | FTE for dedicate WHS team members, e.g., implementation leaders, coaches |

| Complexity | The nature, scope, and number of steps taken to engage with the WHS, e.g., referral | The number of steps needed for a Veteran to be referred, scheduled, and to complete a CIH clinic visit | |

| Offerings * | Specific WHS procedures, programs, and clinical therapies for Veterans to access | PHI Completion | |

| Accessibility * | The extent to which offerings were available and easily used by Veterans, primarily operationalized as referral procedures | Referral initiation source and procedures | |

| Inner Setting - Available resources and characteristics at the local level that may support or obstruct the innovation | Relational connections and communication * | The associations, interactions, and messaging of members of the WHS initiative team with other healthcare teams and departments | Implementation leadership regularly meets with department heads to identify challenges and solutions and share best practices |

| Compatibility | The fit of the WHS innovation with the practices and procedures of each distinct healthcare setting | Seamless referral menus in the electronic health record that facilitates appropriate CIH clinic referral | |

| Structure and resources | The local infrastructure, staffing, funding, and physical space that helped or inhibited successful integration of WHS offerings with the daily clinical workflow | Hiring staff to perform the PHI with Veterans and recommend/coach Veterans as to WHS classes or clinical services aligned with Veteran goals | |

| Learning-centeredness | The degree to which a workplace culture embraces data-driven quality improvement for Veteran outcomes | Each site collects evaluation metrics of program success and utilizes outcome and process metrics to inform continuous process improvement | |

| Information and knowledge access | The availability and ease of access of WHS education to support the delivery of the WHS innovation | Provider training for how to integrate the WHS in their daily practice | |

| Individuals - The roles and features of individuals involved in the implementation, leadership, delivery, and receipt of the WH innovation Roles - Roles indicate one’s position within the project as well as the inner or outer setting |

Innovation deliverers (role) | Providers that directly administered the WHS components (e.g., PHI) to Veterans (i.e., innovation recipients). | Primary care providers or WHS Coaches complete the PHI |

| Implementation leaders and team (role) | Those with the responsibility to facilitate the WHS implementation within the inner setting | WHS leaders regularly assess the reach, adaptability, feasibility etc. of the WHS innovation | |

| Individual characteristics - the conditions needed to optimize WHS delivery and reception | Capability (characteristic) | The capacity with which individuals possess the appropriate knowledge and skills to deliver or receive the innovation | PCP knowledge of how to refer a Veteran for a pain management consult with the CIH clinic |

| Opportunity (characteristic) | Opportunity refers to the availability, control, and scope to deliver or receive the WHS innovation | PCP has the power to refer a Veteran for CIH clinic services, nurse has the power to refer a Veteran to a Well-being class | |

| Motivation (characteristic) | Motivation refers to the individual commitment to deliver or receive the WH innovation. | PCP believes in the vision of the WHS and regularly fills out the PHI as part of daily clinic visits | |

| Outer Setting - the multilevel context (e.g., city, state) in which the inner setting is embedded | Partnerships | Professional connections with outside organizations such as other healthcare entities, academic institutions, and professional organizations | Referrals partnerships with rural providers |

| Critical incidents | Widespread occurrences that disrupt or modify the delivery of the innovation | COVID-19; staffing shortages, | |

| Process - the steps taken to implement the WHS innovation within the inner setting | Doing | Growing the implementation effort from initial, small improvement cycles within a microsystem (e.g., one PACT team clinic) | Implementing the innovation on one PACT team clinic |

| Reflecting and evaluating | Collecting metrics to assess status of implementation process and identify areas for process improvement | Capturing Veteran “engagement” metrics to track use of the innovation such as Wellbeing program attendance |

This construct was developed to reflect available data and was not a CFIR 2.0 Construct

Two or more constructs were grouped together to simplify description of the results

WHS=Whole Health System; PHI=Personalized Health Inventory; CIH=Complimentary Integrative Health; FTE=Full Time Equivalents; PCP=Primary Care Provider; PACT=Patient Aligned Care Team

Table 2.

Site-Specific Barriers and Facilitators through Updated CFIR Lens

| Site Descriptives* | Innovation | Inner Setting | Individuals | Outer Setting | Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Site 1

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site 2

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site 4

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site 5

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site 6

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site descriptives provide ranges of facility bed and rounded population estimates. WH=Whole Health; PHI=Personal Health Inventory, PHP=Personal Health Plan; FTE=Full Time Equivalent(s); PHP=Personal Health Plan; PHI=Personal Health Inventory; N/A=Not applicable or missing information; HCP=Healthcare Professional; CIH=Complimentary Integrative Health; IHH=Integrative Health and Healing; PCP=Primary Care Provider; CPRS=Computerized Patient Record System; TMS=Talent Management System (Staff Education Portal); QOL=Quality of Life; VVC=VA Video Connect

Figure 2. Updated CFIR Domains and Constructs Identified in Whole Health System Engagement Analysis.

The + symbol indicates facilitators whereas the − symbol represents the barriers under the corresponding construct.

Innovation

The Whole Health innovation faced barriers and facilitators regarding cost and complexity of access to innovation core components. Each site was required to feature the Whole Health core components as listed in the introduction.

Cost.

Cost was estimated based on the number of Full Time Equivalents (FTEs) allotted to support the initiative. While a higher number of FTEs facilitated the innovation delivery, most sites were restricted to few FTEs (FTE median: 2, range: 0–65). The frequent low number of FTEs was considered a barrier to implementation, but one site was facilitated by 65 FTEs.

Complexity.

At two sites, informants reported that the complex consultation process was a barrier that hindered Well-being class attendance and ease of referral to clinic services. Informants from another site reported that the electronic health record (EHR) consultation menu facilitated knowledge of Whole Health offerings, but that the high volume of options was visually overwhelming. These providers suggested a single order option for consultations to improve Whole Health uptake. Complexity was also reduced by allowing Veterans to self-refer, simplifying the simplified referral process, and providing access to a variety of Well-being classes. Barriers consisted of limited class options, provider-only referral, and limited modalities (online vs. in-person) (four sites).

Inner Setting

The inner setting indicated the local site context where the innovation was deployed. Barriers and facilitators were categorized within the following constructs: relational connections and communication, compatibility, structure and resources, learning-centeredness, and information and knowledge access.

Relational connections and communication.

Each facility varied by implementation stage and communication plan. Facilitators included intentional interdepartmental relationship-building to gain leadership buy-in and improve appropriate referral rates for CIH services (two sites) and informal communication (e.g., word-of-mouth) to raise awareness (three sites). Relational and communication barriers were noted at the microsystem level (i.e., Whole Health coach working independently of the Patient Aligned Care Team (PACT) and not attending weekly huddles (one site)) and at the facility level (i.e., interdepartmental siloes) (one site).

Compatibility.

Whole Health compatibility within each context was enhanced by a designated Whole Health coach assigned to each PACT (one site). Compatibility was inhibited by the lack of an EHR reminder to promote Whole Health evaluation during clinic visits (one site) and duplicative charting requirements (one site).

Structure and resources.

Innovation integration was facilitated by existing structures, such as the GeroFit physical activity program and the Integrated Health and Healing (IHH) department (two sites) because the existing structures operated with a similar philosophy and care approach. Barriers included: insufficient funding for program implementation (three sites, <8 FTE), staffing turnover (two sites), and delegating Whole Health assessment to existing providers without appropriate incentives (two sites). Time and staffing barriers prevented robust Whole Health delivery to Veterans (one site). Whole Health team leaders described an additional barrier to in-person CIH clinic visits, as one clinic was located nearly 50 miles from the main campus (one site).

Learning-centeredness.

At four VAs, collaborators noted the implementation barrier of insufficient pre and post-evaluation metrics of Veteran Whole Health use and workforce needs. No facilitators were noted.

Information and knowledge access.

Information and knowledge access were facilitated by a variety formal training opportunities including a nationally replicated coach training program, online education, a Well-being staff retreat, and direct care training (two sites). However, barriers included insufficient continuing education and lack of updated information about Well-being class schedules, current therapies, active CIH providers, and EHR referral procedures (three sites).

Individuals

The updated CFIR framework divides this domain into the roles and characteristics of individuals.16 Barriers and facilitators emerged including innovation deliverers, implementation leaders and team, capability, and opportunity and motivation.

Roles

Innovation deliverers.

Innovation delivery was facilitated by clear role delineation to specialized staff such as coaches (one site) and specialty pain clinic providers (2 sites, IHH and CIH clinics). Barriers from role conflict arose when general healthcare staff and providers (e.g., primary care physicians) had to deliver initial Whole Health assessment (i.e., PHI), education, and referral in addition to existing clinical duties (four sites).

Implementation leaders and team.

Facilitators of the implementation process included implementation leaders and team members with alloted time, compensation, and a primary responsibility to initiate and maintain implementaiton procedures at their VAs (five sites). Conversely, barriers included leadership that implemented Whole Health as a secondary responsibility (e.g., steering committee) (two sites).

Characteristics

Capability.

Barriers consisted of Veteran knowledge barriers (four sites), staff/provider knowledge barriers (three sites), and provider referral knowledge barriers (three sites). Some of these knowledge barriers included insufficient knowledge of the referral criteria for CIH or Wellbeing classes, the EHR referral process, and the most current list of Whole Health providers and offerings. Conversely, interviewees at one site reported the facilitator of a PACT-embedded Whole Health coach that served as a team guide, Veteran educator, and knowledge source.

Opportunity and motivation.

Provider opportunity barriers included competing clinical duties and workflow (two sites). Veteran opportunity barriers to in-person or virtual wellbeing included schedule conflicts and no internet access (two sites). Provider motivation barriers included the viewpoint that formal Whole Health procedures were superfluous, because the Whole Health philosophy was already delivered with an informal clinical assessment (two sites).

Limitations

The available data are limited to six VA sites within the VAQS Program. The VA sites participating in the VAQS program may have unique characteristics (e.g., strong academic affiliations, QI resources) that may limit the interpretation of the findings. Additionally, the data did not include an exhaustive list of available Whole Health resources among sites and integration into each system is constantly changing. The data collected was from one point in time. Interview data were subject to primacy and recency biases given that informants perceptions of implementation may vary with Flagship status and variable local implementation efforts.

Lastly, the updated CFIR was applied after the data were gathered to synthesize findings and was used for after-implementation analysis post-hoc.16 While this model facilitated synthesis of cross-site barriers and opportunities, the retroactive use may have limited the full scope of application. Future work should further investigate these findings with consistent CFIR application from project onset through publication.

Discussion

We examined barriers and facilitators to Whole Health implementation and Veteran use within and across a convenience sample of VAMCs through structured analysis and synthesis of the updated CFIR domains. While VAMCs individualize their approach to implementation and use, this project improves our understanding of strengths and opportunities for improvement regarding implementation on a local and national scale, which have implications for large healthcare systems. We will discuss lessons learned from all updated CFIR domains.

While we found the strengths of Whole Health care coordination and person-centered care in the context of COVID-19 crisis management and historic staffing shortages,24–26 we also identified barriers of workforce role strain and innovation complexity. For instance, one VA’s GeroFit program designed each physical activity regimen according to each Veteran’s goals and physical status, and all sites promoted PHI completion as a Whole Health entry point. Despite these advancements, our results suggest that barriers to full integration include a lack of assigned staff for Whole Health delivery, staff knowledge deficits, variable class offerings and clinic use, and challenging referral procedures. These challenges signal an opportunity to standardize implementation across VAs.

Veteran Whole Health use begins with Veteran goal setting (PHI) and continues with Well-being class participation and therapeutic management (CIH clinic). This process requires staff, time, and resources to initiate Whole Health assessment and guide Veterans to the appropriate offerings. Inner setting facilitators for this process included appropriate staff training and Whole Health innovation deliverers. However, barriers included providers and staff needing help to incorporate Whole Health into their clinical workflow. Meyers and colleagues (2012) identified four implementation phases with the first phase consisting of self-assessment strategies, creating adaptation strategies, and capacity-building strategies.27 Consistent with the capacity-building activities, robust initial training occurred across sites. However, there was an opportunity to increase buy-in, organizational capacity, and staff maintenance, which may be addressed partially with Whole Health coaches to facilitate innovation delivery.

Each VA network has had the leeway to implement Whole Health coaching differently across sites: coaches may be Veterans or other healthcare workers that have undergone specialized training and have provided goal-setting consultations via different modalities throughout the pandemic.28,29 Coaching may assist with building organizational capacity, lower provider stress, and diffuse this innovation at the microsystem level (PACT team). Previous research indicates that Veterans benefitted from short-term coaching, but desired more intensive and ongoing coaching programs for goal attainment,30 requiring sufficient FTE allocation. Moreover, the coaching intensity will vary by Veteran, warranting evaluation to identify the dose and duration of coaching necessary to promote efficient Veteran-centric coaching and quality of life. We found that coaches were an essential knowledge source (current class offerings) and may address knowledge access challenges to changes in referral processes.

We also found that implementation facilitators included assigned implementation teams, robust communication and relationship-building, and easy knowledge access, but only some sites had these advantages. The essential components of later implementation stages include team building, a clear implementation plan, process evaluation, and supportive feedback mechanisms.27 Although some site partners reported strong interdepartmental relationships with increased leadership buy-in, interdepartmental siloes prevented communication about the implementation process and a promoted a lack of a learning-centered culture.

Sites may support continuous improvement with a mix of formal and informal feedback mechanisms and varied process and outcome evaluation metrics.27 Feedback mechanisms may include periodic reflections This standardized methodology entails qualitative exploration of clinician and Veteran experiences of the implementation process to integrate feedback and improve outcomes (e.g., fidelity).31 Future research should use this approach to explore bi-directional communication across the organizational leadership structure to evaluate transformational change. Future work in this area should also build on our findings to systematize Whole Health delivery and continually improve this innovation with Veteran and VA employee feedback. Such approaches may include employee retreats, advisory councils, workshops, and cross-site dissemination of best practices.

Conclusions

This project illuminated the Whole Health integration nationally and evidenced the useability of the CFIR framework in a largescale, national project. This project identified key system-level facilitators and barriers related to initiative integration into a VA system.

Implications

These findings have implications for large healthcare systems. Namely, implementing multifaceted healthcare interventions at a system-wide level is largely influenced by the implementation structure and process to support integration and improvement at local and regional levels. Taking these contexts into account when planning interventions and allocating resources for sustainability will be key for continued efforts to use interdisciplinary approaches. Whole Health impacts patients’ perceptions of and participation in their care and has shown to improve Veteran health and well-being. This initiative may also improve the lives of VA employees as national expansion continues.5

Future research and QI efforts should consider the cost-effectiveness of integrating this innovation e.g., analyzing Whole Health FTEs/bed or staff count with process and outcome metrics. Quantitative and qualitative evaluation metrics should include Veteran use of the three core Whole Health components (number of completed PHIs) to assess the success of process improvement and adapt implementation strategies.

Supplementary Material

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

No conflicts were declared for any of the authors. This work was also supported by the Office of Academic Affiliations, Department of Veterans Affairs. VA National Quality Scholars Program and with use of facilities at seven VAs.

Biographies

Corresponding author: Dr. Christine C. Kimpel PhD, RN, MA completed two years as a pre-doctoral fellow in the VA Quality Scholars program, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System. She is currently a post-doctoral research fellow at the Vanderbilt University School of Nursing in Nashville, Tennessee. She can be reached at Christine.c.kimpel@vanderbilt.edu.

Dr. Elizabeth Allen Myer, PhD, RN-BC completed two years as a fellow in the VA Quality Scholars program located in Durham, North Carolina. She can be reached at elizabeth.myer@va.gov.

Dr. Anagha Cupples, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC, CTR completed two years as a fellow in the Atlanta VA Quality Scholars program located in Atlanta, Georgia. She can be reached at anagha.cupples@va.gov or atcupple@gmail.com.

Dr. Joanne Roman Jones, JD, PhD, RN, VA completed two years as a fellow in the VA Quality Scholars in in Durham, NC (joanne.romanjones@va.gov). She is currently an Assistant Professor at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, Manning College of Nursing and Health Sciences (joanne.romanjones@umb.edu).

Dr. Katie J. Seidler, PT, DPT, MSCI, MMCI completed two years in the VA Quality Scholars (VAQS) program as a fellow in Durham, North Carolina. She can be reached at seidlerk@gmail.com

Dr. Chelsea K. Rick, DO completed her fellowship as an Advanced Geriatric Fellow with the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System. She also completed her fellowship as a Vanderbilt Quality Scholar at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and was an Instructor of Medicine with the Division of Geriatric Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee. She can be reached at chelsea.rick@vumc.org.

Dr. Rebecca Brown, PhD, MEd, RN is a Nurse Scientist with the Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research (CCDOR), Minneapolis Adaptive Design and Engineering Program (MADE), Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. She is also an Adjunct Clinical Professor with the University of Minnesota School of Nursing. She completed two years as a fellow in the VA Quality Scholars, Minneapolis, Minnesota (rebecca.brown4@va.gov).

Caitlin Rawlins, BSN, RN is the Deputy Director of Clinical Tech Innovation as part of the VHA Innovation Ecosystem and Office of Healthcare Innovation and Learning (OHIL). She completed two years as a VA Rural Scholars Fellow (RSF) in Asheville, North Carolina (caitlin.rawlins@va.gov).

Dr. Rachel Hadler, MD is an Assistant Professor with the Departments of Anesthesiology and Family and Preventive Medicine, Emory Critical Care Center, Emory University School of Medicin in Atlanta, Georgia. She completed two years as a fellow in the Iowa City VHA, VA Quality Scholars in Iowa City, IA. She can be reached at rachel.hadler@emory.edu.

Dr. Emily Tsivitse, PhD, APRN, AGPCNP completed two years as a VA Quality Scholar Postdoctoral Fellow at the Louis Stokes VA Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio; She is also an Adjunct Professor at Case Western Reserve University in the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing located in Cleveland, Ohio. She can be reached at ekt22@case.edu/

Dr. Mary Ann C. Lawlor, PhD, MA.Ed. was a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholar. RN. She completed two years as a fellow in the VA Quality Scholar program in Cleveland, Ohio. She can be reached at MaryAnn.Lawlor@va.gov.

Amy Ratcliff, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC completed two years as a fellow in the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System VA Quality Scholars program in Nashville, Tennessee. She is also a Nurse Practitioner in the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville, Tennessee (amy.guidera@va.gov).

Natalie R. Holt PhD completed two years as a fellow in the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System VA Quality Scholars program in Nashville, Tennessee. She is also a Clinical Psychologist at Tennessee Valley Healthcare System. She can be reached at natalieholt93@gmail.com.

Dr. Carol Callaway-Lane, DNP, ACNP-BC is the Director of the National Geriatric Scholars Program Quality Improvement Workshop and Practicum. She is also an Associate program director of the Nashville VA Quality Scholars Program and Co-director of the Lung Cancer Screening Program in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville, Tennessee, USA (carol.callaway-lane@va.gov).

Dr. Kyler Godwin, PhD, MPH is the Chief of the Implementation and Innovations Program, Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center. She is also the Director of the VA Quality Scholars Coordinating Center (kyler.godwin@va.gov). She is also the Vice Chair of Quality Improvement and Innovation and Associate Professor, the Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, TX (Kyler.godwin@bcm.edu).

Dr. Anthony H. Ecker, PhD is a Clinical Psychologist and Investigator with the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, South Central Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center. He is also an Assistant Professor at the Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, TX (aecker@bcm.edu).

Contributor Information

Christine C. Kimpel, VA Quality Scholars program, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System. Vanderbilt University School of Nursing in Nashville, Tennessee

Elizabeth Allen Myer, VA Quality Scholars program located in Durham, North Carolina..

Anagha Cupples, Atlanta VA Quality Scholars program located in Atlanta, Georgia..

Jones Joanne Roman, VA completed two years as a fellow in the VA Quality Scholars in in Durham, NC; University of Massachusetts, Boston, Manning College of Nursing and Health Sciences.

Katie J. Seidler, VA Quality Scholars (VAQS) program as a fellow in Durham, North Carolina.

Chelsea K. Rick, Advanced Geriatric Fellow with the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System. Vanderbilt Quality Scholar at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and was an Instructor of Medicine with the Division of Geriatric Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee.

Rebecca Brown, Center for Care Delivery and Outcomes Research (CCDOR), Minneapolis Adaptive Design and Engineering Program (MADE), Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Healthcare System.; University of Minnesota School of Nursing. She completed two years as a fellow in the VA Quality Scholars, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Caitlin Rawlins, Deputy Director of Clinical Tech Innovation as part of the VHA Innovation Ecosystem and Office of Healthcare Innovation and Learning (OHIL).; VA Rural Scholars Fellow (RSF) in Asheville, North Carolina

Rachel Hadler, Departments of Anesthesiology and Family and Preventive Medicine, Emory Critical Care Center, Emory University School of Medicin in Atlanta, Georgia.; Iowa City VHA, VA Quality Scholars in Iowa City, IA.

Emily Tsivitse, VA Quality Scholar Postdoctoral Fellow at the Louis Stokes VA Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio;; Case Western Reserve University in the Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing located in Cleveland, Ohio.

Mary Ann C. Lawlor, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholar. RN. VA Quality Scholar program in Cleveland, Ohio.

Amy Ratcliff, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System VA Quality Scholars program in Nashville, Tennessee.; Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville, Tennessee

Natalie R. Holt, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System VA Quality Scholars program in Nashville, Tennessee Tennessee Valley Healthcare System.

Carol Callaway-Lane, National Geriatric Scholars Program Quality Improvement Workshop and Practicum; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Kyler Godwin, Implementation and Innovations Program, Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center.; Department of Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, TX

Anthony H. Ecker, Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, South Central Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center. Menninger Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, TX

References

- 1.US Department of Veterans Affairs. Whole Health Library. Updated July 29, 2021. Available at: https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTHLIBRARY/about/index.asp. Accessed December 22, 2022.

- 2.National Center for Complimentary and Integrative Health. Complementary, alternative, or integrative health: What’s in a name? Updated April 2021. Available at: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name. Accessed January 14, 2023.

- 3.US Department of Veterans Affairs. About VHA. Updated August 15, 2022. Available at: https://www.va.gov/health/aboutvha.asp. Accessed May 31, 2023.

- 4.Krejci LP, Carter K, Gaudet T. Whole Health: The Vision and Implementation of Personalized, Proactive, Patient-driven Health Care for Veterans. Medical Care. 2014: S5–S8. DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bokhour BG, Haun JN, Hyde J, Charns M, Kligler B. Transforming the Veterans Affairs to a Whole Health System of Care: Time for Action and Research. Medical Care. 2020; 58(4): 295–300. DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Congress. CADCA. S.524 - Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016. Updated July 22, 2016. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/524/text. Accessed June 6, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards ER, Barnes S, Govindarajulu U, Geraci J, Tsai J. Mental health and Substance Use Patterns Associated with Lifetime Suicide Attempt, Incarceration, and Homelessness: A Latent Class Analysis of a Nationally Representative Sample of US Veterans. Psychological Services. 2021; 18(4): 619. DOI: 10.1037/ser0000488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin LA, Peltzman T, McCarthy JF, Oliva EM, Trafton JA, Bohnert AS. Changing Trends in Opioid Overdose Deaths and Prescription Opioid Receipt among Veterans. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2019; 57(1): 106–110. DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson V, Diehle J, Dunn R, Jones N, Greenberg N. The Impact of Military Service on Health and Well-being. Occupational Medicine. 2019; 69(1): 64–70. DOI: 10.1093/occmed/kqy139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Veterans Affairs. Personal Health Inventory. Updated April 2020. Available at: https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/10-773_PHI_May2020.pdf. Accessed December 22 2022.

- 11.Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Zeliadt SB, Mohr D. Whole Health System of Care Evaluation: A progress report on outcomes of the WHS pilot at 18 flagship sites. 2020. Available at: https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/EPCC_WHSevaluation_FinalReport_508.pdf. Accessed December 22, 2022.

- 12.Reed DE, Bokhour BG, Gaj L, et al. Whole health use and interest across veterans with co-occurring chronic pain and PTSD: An examination of the 18 VA medical center flagship sites. Global Advances in Health and Medicine. 2022; 11. DOI: 10.1177/21649561211065374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Congress US. Joint Explanatory Statement of the Committee of Conference on S 524, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act (CARA). Published 2016. Available at: https://docs.house.gov/billsthisweek/20160704/114-CRS524-JES.pdf. Accessed December 22, 2022.

- 14.Haun JN, Melillo C, Cotner BA, McMahon-Grenz J, Paykel JM. Evaluating a Whole Health Approach to Enhance Veteran Care: Exploring the Staff Experience. Journal of Veterans Studies. 2021; 7(1): 163–173. DOI: 10.21061/jvs.v7i1.201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering Implementation of Health Services Research Findings into Practice: A Consolidated Framework for Advancing Implementation Science. Implementation science. 2009; 4(1). DOI: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, Lowery J. The Updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Based on User Feedback. Implementation Science. 2022; 17(1): 1–16. DOI: 10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A Systematic Review of the Use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implementation Science. 2015; 11(1): 1–13. DOI: 10.1186/s13012-016-0437-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Directions and Examples. Content last reviewed September 2020. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/tool2b.html [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patrician PA, Dolansky M, Estrada C, et al. Interprofessional education in action: the VA Quality Scholars fellowship program. Nursing Clinics. 2012; 47(3): 347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Splaine ME, Ogrinc G, Gilman SC, et al. The Department of Veterans Affairs National Quality Scholars Fellowship Program: Experience from 10 Years of Training Quality Scholars. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2009; 84(12): 1741–1748. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bfdcef [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Splaine ME, Aron DC, Dittus RS, et al. A Curriculum for Training Quality Scholars to Improve the Health and Health Care of Veterans and the Community at Large. Quality Management in Healthcare. 2002; 10(3):10–18. DOI: 10.1097/00019514-200210030-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horstman MJ, Miltner RS, Wallhagen MI, et al. Developing Leaders and Scholars in Health Care Improvement: The VA Quality Scholars Program Competencies. Academic Medicine. 2020; 96(1): 68–74. DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0—Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence—Revised Publication Guidelines from a Detailed Consensus Process. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2016; 222(3): 317–323. DOI: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwabenbauer AK, Knight CM, Downing N, Morreale-Karl M, Mlinac ME. Adapting a Whole Health Model to Home-Based Primary Care: Bridging Person-Driven Priorities with Veteran and Family-Centered Geriatric Care. Families, Systems, & Health. 2021; 39(2): 374–393. DOI: 10.1037/fsh0000613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berwick DM. Launching Accountable Care Organizations—The Proposed Rule for the Medicare Shared Savings Program. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011; 364(16): e32. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1103602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cattel D, Eijkenaar F, Schut FT. Value-Based Provider Payment: Towards a Theoretically Preferred Design. Health Economics, Policy and Law. 2020; 15(1): 94–112. DOI: 10.1017/S1744133118000397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyers DC, Durlak JA, Wandersman A. The Quality Implementation Framework: A Synthesis of Critical Steps in the Implementation Process. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012; 50: 462–480. DOI: 10.1007/s10464-012-9522-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson EM, Possemato K, Martens BK, et al. Goal Attainment among Veterans with PTSD Enrolled in Peer-Delivered Whole Health Coaching: A Multiple Baseline Design Trial. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice. 2022; 15(2): 197–213. DOI: 10.1080/17521882.2021.1941160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hale-Gallardo J, Kreider CM, Castañeda G, et al. Meeting the Needs of Rural Veterans: A Qualitative Evaluation of Whole Health Coaches’ Expanded Services and Support during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(20): 13447. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph192013447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Purcell N, Zamora K, Bertenthal D, Abadjian L, Tighe J, Seal KH. How VA Whole Health Coaching can Impact Veterans’ Health and Quality of Life: A Mixed-Methods Pilot Program Evaluation. Global Advances in Health and Medicine. 2021; 10: DOI: 10.1177/2164956121998283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finley EP, Huynh AK, Farmer MM, et al. Periodic Reflections: A Method of Guided Discussions for Documenting Implementation Phenomena. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2018; 18(1): 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.