Abstract

Protein subcellular localization prediction is of great significance in bioinformatics and biological research. Most of the proteins do not have experimentally determined localization information, computational prediction methods and tools have been acting as an active research area for more than two decades now. Knowledge of the subcellular location of a protein provides valuable information about its functionalities, the functioning of the cell, and other possible interactions with proteins. Fast, reliable, and accurate predictors provides platforms to harness the abundance of sequence data to predict subcellular locations accordingly. During the last decade, there has been a considerable amount of research effort aimed at developing subcellular localization predictors. This paper reviews recent subcellular localization prediction tools in the Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Virus-based categories followed by a detailed analysis. Each predictor is discussed based on its main features, strengths, weaknesses, algorithms used, prediction techniques, and analysis. This review is supported by prediction tools taxonomies that highlight their rele- vant area and examples for uncomplicated categorization and ease of understandability. These taxonomies help users find suitable tools according to their needs. Furthermore, recent research gaps and challenges are discussed to cover areas that need the utmost attention. This survey provides an in-depth analysis of the most recent prediction tools to facilitate readers and can be considered a quick guide for researchers to identify and explore the recent literature advancements.

Keywords: Subcellular localization predictions, Machine learning/deep learning, Protein predictions, Bioinformatics

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Proteins are complex molecules. They are comprised of long chains of amino acids that perform a variety of functions in different organisms. The function of a protein depends on the compartment or organelle where it is located. Each subcellular compartment has a well-defined function within a cell that has a distinct physicochemical environment. Physic- ochemical properties drives the proper functioning of the proteins [1]. Also, it is essential for proteins to be destined for their specific locations or compartments to perform their functions [2]. Knowledge of proteins in different organelles and their subcellular locations is essential to gain insight into how the cell functions as the primary unit of life [3].

Experimental methods to explore the knowledge of pro- teins in different organelles and their subcellular locations are relatively expensive, labour-intensive and time-consuming process. Due to this, a large informational gap exists be- tween known proteins and their location information [4]. Alternately, computational subcellular location and predic- tion tools have the advantage of being cost-effective, time- efficient, and capable of complementing resource-consuming experimental techniques adequately [5]. During the past decade, researchers have been working considerably to de- sign computational tools and techniques to explore various aspects of location information and subcellular localization predictions.

Computational methods that are widely used in subcel- lular localization prediction tools are roughly divided into; Sequence-based methods, Annotation/ Information/ Knowl- edge/ Homology-based methods, and Structure-based meth- ods [6]. Sequence-based predictors make use of known sort- ing signals, amino acid composition information, or often- times both [7]. Whereas, annotation-based predictors make use of information about functional domains and motifs, protein-protein interactions, homologous proteins, annotated Gene Ontology (GO) terms, and textual information pri- marily from SwissProt keywords or PubMed abstracts [8]. These methods are favourable for predicting the functions of interacting proteins and proteins from coexpressed genes but are seriously restricted by the potentially large noise in protein–protein interaction data and the insufficient number of annotated proteins [9]. However, sequence-based methods are widely adopted in protein function prediction due to the relatively easy access of abundant high-quality sequence data in public databases and its significant ability to predict the function of remotely relevant proteins and the homologous proteins of distinct functions [10].

Predicting tools that use experimentally verified annotated protein sequences to predict subcellular locations are known as Homology-based predicting tools or Template-based Pre- dictors [11]. On the other hand, sequence-based methods tend to predict locations based on protein sequences only i.e. Template-free predictions. The disadvantage of homology- based methods is the limited availability of templates of a large number of proteins [12]. Un-annotated proteins pose significant challenges to homology-based methods as they do not have a relevant template to rely on. In such challenging situations, Ab-initio predicting tools provide solutions for subcellular localization predictions. [13].

Sequence-based methods are further categorized into similarity-based methods. Similarity-based methods e.g. re- lying on BLAST [14] and HMMER, typically assign an unannotated protein to the function of another protein similar in sequence to that protein [15]. The main drawback is these tools are heavily dependent on sequence homology and their performance degrades or breaks down completely when only remote or no convincing homology is available. Methods like Support Vector Machines (SVM) [16], [17], and deep neural networks such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) [18], [19], Long Short Term Memory Networks (LSTMs) [20], [21], Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) PSLOP [22] are considerably advancing to propose handy solution for non-homologous or template free predictions.

A further category is meta-predictors which integrate the prediction results of multiple tools [23], [24]. There are also hybrid methods that combine sequence-based and annotation-based information to harness the advantages of both approaches [25], [26], [27]. Fig. 1 illustrates the flowchart and a step-by-step procedural guide for a machine learning approach for sub-cellular localization prediction along with Template-based as well as Template-free method- ologies.

Fig. 1.

Abstract level step-by-step flowchart for subcellular localization predictions.

There are few recent surveys that cover protein subcellular localization predictions tools and techniques [28], [29], [30],

[31], [32], [33], [34]. However, these surveys are either only descriptive or carry a limited domain spectrum with small sets of tools. Also, greater help is taken from textual analysis only which requires readers to go through heavy written content to explore recent predictors. Therefore, this article is established based on three diverse taxonomies and other diagrammatic illustrations to facilitate readers better. In the light of already published literature:

The highlighted contributions of the paper are enumerated as follows:

-

1)

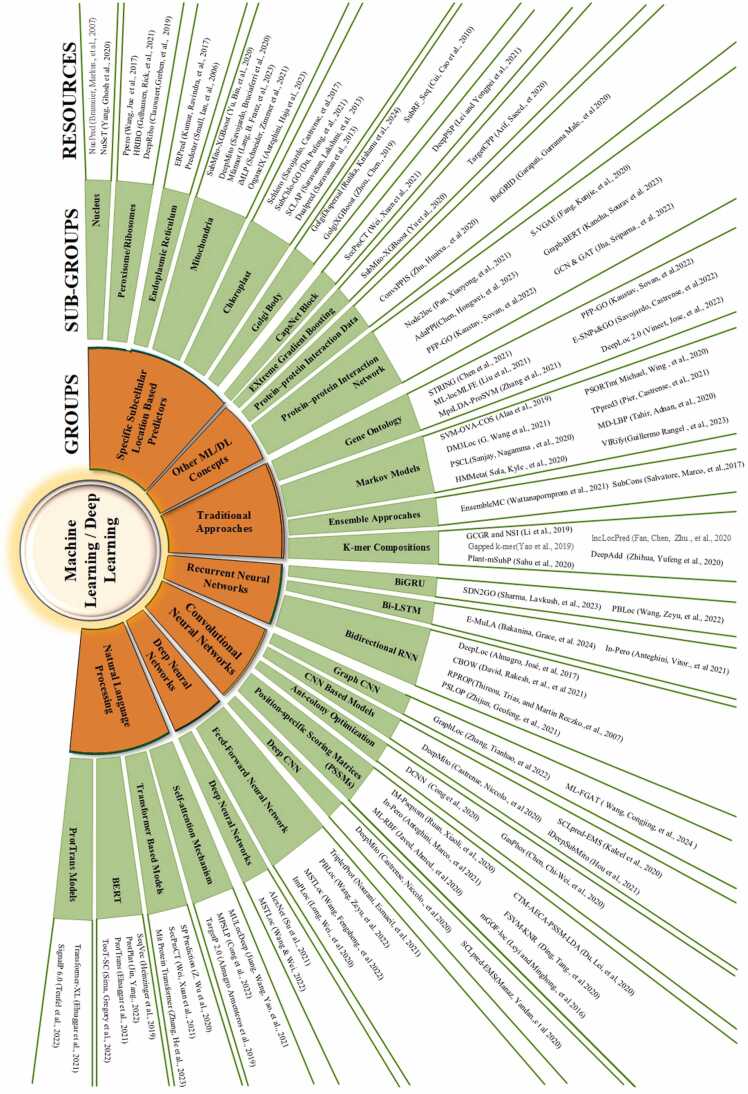

A comprehensive, precise and well-directed machine learning and deep learning-based classification dia- gram is designed that covers 7 primary areas of ML/DL methods followed by 28 sub-classifications. All these classifications are supported by more than 100 recent and dynamic subcellular localization prediction tools. This diagram (Fig. 2) mostly covers 5 to 7 years old diverse tools and techniques of protein subcellular localization.

-

2)

This survey provides two taxonomies for single- category supported predicting tools and multi-category based predicting tools to give a very clear and con- cise illustration that is further distinguished based on colours assigned to the method involved. These tax- onomies are quick guides for users to look for method- ology adapted, predictor class, and relevant tools.

-

3)

As this survey covers broader sets of recent prediction tool categories, it facilitates readers in better under- standing their relationships, features, algorithms, and class of tools in greater detail.

-

4)

Users can select the tools they need based on the infor- mation summarized and can access them through the detailed Table provided. Apart from the applicability of the tools, only actively maintained tools are listed.

-

5)

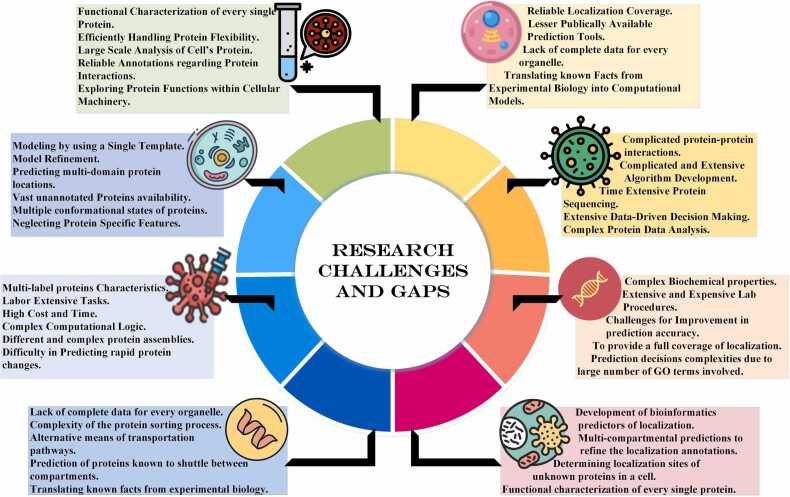

Another highlighted contribution is to provide a diverse set of research gaps and current challenges that are encountered during the prediction phases in the form of a dendrogram. This dendrogram serves as a reference to many recent research problems and loopholes for users. It provides an excellent kickstart to work on potential solutions.

-

6)

A tool-based information summary table is given that covers several locations and features predicted by a tool followed by methods and models adapted. It is sup- ported by extensive evaluations of subcellular localiza- tion prediction tools while providing detailed insights on why some tools have better prediction accuracy than others.

Fig. 2.

Categories and sub-categories of machine learning and deep learning-based subcellular localization prediction tools.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section II covers categories of subcellular localization prediction tools for both single and multi categories further supported by taxonomic illustrations, Section III covers challenges and re- search constraints, Section IV concludes the paper followed by references used.

2. Categories of subcellular localization prediction tools

Protein subcellular localization prediction is essential for revealing biological information and the functioning of the cells [35]. Cells are the basic unit of life and contain many protein molecules located in and operating within different organelles. Proteins in various organelles or subcellular lo- cations have different functionalities [36], and co-location within the same organelle is generally a requirement for cooperation between proteins. Therefore, knowledge of sub- cellular localization plays a significant role in understanding specific functionalities and biological processes [37]. A con- siderable amount of work is ongoing in the bioinformatics research community to expand our knowledge of the subcel- lular localization of proteins. However, complete knowledge is still elusive due to the highly complex nature of proteins and the processes and signals that direct them to different subcellular compartments [4].

Subcellular localization prediction tools are platforms for knowledge discovery via machine learning [38]. Massive amounts of protein data were once considered a complex scenario for subcellular location prediction [39]. Now, ma- chine learning has shifted the paradigm, and access to more data is considered vital for better prediction results. Knowl- edge of proteins in different organelles and their subcellular locations is essential to gain insight into how the cell func- tions as a primary unit of life [40]. During the past decade, researchers have been working rigorously to improve the accuracy of subcellular localization prediction tools. Com- putational prediction tools have the advantage of being cheap and extremely fast to run compared to complex and resource- consuming experimental techniques. Still, the accuracy of their predictions is often an issue [41]. Computational meth- ods that are widely used in subcellular localization predictors may be divided into four main categories; 1) Sequence- based predictors, 2) Annotation-based predictors, 3) Hybrid predictors, 4) Meta-predictors [42], [32].

Sequence-based methods utilize only amino acid se- quences from the query protein as input [43]. They rely on detecting sequence-coded signals such as N-terminal Target- ing Peptides (NTP) [44], [45] or Nuclear Localization Signals (NLS) [46]. Sequence-based predictors consider that the amino acid composition of proteins is correlated with their localization. They are subdivided into two categories, i.e. homology-based, and ab initio approaches [47]. Homology- based methods rely on homologous proteins that are anno- tated for subcellular localization, whereas ab initio methods generally adopt statistical approaches relying on the primary sequence of the query only.

Homology-based methods are also known as annotation- based methods or knowledge-based methods [48]. They are widely based on Gene Ontology (or PubMed abstracts) and Swiss-Prot keywords. Most of them are capable of search- ing/transferring the sequence (if the information is not avail- able for the query protein) from the annotation of close ho- mologs [49]. Because of this, they are generally more accu- rate in their predictions than other known methods. However, the absence of close homologous proteins often degrades the accuracy of their predictions when only remote homologs are available (also known as the twilight zone phenomenon), and prevents them from producing any prediction at all in those cases where no homologs of known location can be found [48].

Hybrid predictors are based on both sequence and homology-based methods [50], [51]. They adapt desired fea- tures from both types of methods for better prediction and results. In other words, hybrid predictors use the detection of sorting signals along with composition information, ho- mology transfer, and whatever additional information may be available [52]. Meta-predictors use other predictors’ results and combine them to deduce suitable predictions. Another aspect differentiating predictors is the number of localization classes they adopt as their targets. Unique subcellular loca- tions may be hundreds, but for many of them, only handfuls of annotated examples are available. Because of this, most systems restrict their predictions to a limited number of well- represented localizations, typically between 2 and a dozen, with some systems only focusing on one task (e.g. secreted from the cell vs. non-secreted) and others adopting multiple categories at the same time [53].

A detailed Taxonomy of subcellular localization predictors based on the four aforementioned criteria is given in Fig. 3 that illustrates tools for single-category predictors only. It in- dicates Hybrid methods in yellow, Meta-Predictors in green, Sequence-based methods in orange, and Homology-based methods in blue. Predicting tools are discussed based on three categories i.e. (Eukaryotes, Prokaryotes, and Viruses). Recent examples of tools are given for each category and their methods are discussed in subsequent sections to help researchers with better predictor choices for protein subcel- lular localization.

Fig. 3.

Tools for subcellular localization predictions for single category.

2.1. Subcellular localization prediction tools for eukaryotes

Eukaryotic Cells are distinguished based on the presence of a membrane-bounded nucleus, organelles, and numerous internal structures such as the Endoplasmic Reticulum, Golgi apparatus, secretory vesicles, etc. Eukaryotes evolved from prokaryotes. They contain a vast and diverse amount of or- ganisms, including Humans, Plants, Animals, Fungi, various kinds of algae, etc. Several subcellular localization predictors for the eukaryotic family have been developed to date. One such example is the Multi-label Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) for Humans. mLASSO- Hum [54] is a multi-label predictor that provides an inter- pretable solution for large-scale single and multi-label human proteins with the additional feature of providing biological interpretability for the prediction of protein existence at a particular location. mLASSO-Hum also avoids overfitting of the model, unlike existing homology-based predictors that often lack interpretability and suffer from overfitting due to the high dimensionality of feature vectors.

Unlike mLASSO-Hum, various other multi-label predic- tors, e.g. Hum-mPLoc 2.0 [55], mGOASVM [56] HybridGO-Loc [57] R3P-Loc [58] mPLR-Loc [59] Multi-Model Multi- Label Learning [60] Dimensionality Reduction Random Pro- jection [61] KNN-SVM ensemble classifier [62] use Gene Ontology (GO) information to train various categories of statistical algorithms. This may lead to good predicting per- formances, with the drawback of lacking interpretability, i.e. not providing a rationale behind the prediction of a protein residing at a particular location. Depending on the precise type of algorithm and training data adopted, overfitting of the training set may also be an issue. HumLoc-LBCI [41] is quite similar to mLASSO-Hum, except it uses a novel V-dimensional feature vector rather than an original U- dimensional feature vector that has proven to be more useful in prediction accuracy.

DeepPSL [63] is a deep learning-based predictor that automatically learns abstract and high-level feature repre-sentations of human proteins through non-linear relations among broad subcellular locations. SubCons [64] uses a Random Forest Classifier (RFS) to combine four predic- tors collectively named MultiLoc2 [65], SherLoc2 [66] and CELLO2.5 [67] and LocTree2 [68]. SubCons integrates dif- ferent features from each predictor to design a multi-method prediction tool. CELLO2.5 [67] deals with determining phys- iochemical properties, i.e. compositions of di-peptide, amino acids, partitioned amino acids, and sequence compositions. LocTree2 [68] uses a cascading mechanism to determine cellular sorting. MultiLoc2 [65] participates in integrating the output of all these four classifiers and making SubCons fully functional. SherLoc2 [66] finally links UniProt IDs depending on PubMed. Combination-based predictors with mix-and-match approaches often result in better accuracy than individual predictors used to build SubCons.

LOCALIZER [69] predicts effector localization in plants while prioritizing effector targets for further evaluation. Gen- erally, plant-based predictors are functional on both host and pathogens. However, effectors exploit plants for the sake of entering organelles. In the majority of cases, effectors do not share sequence similarities with other existing pro- teins. Therefore, LOCALIZER plays a significant role in predicting whether a plant or effector protein can localize to multiple compartments. Plant-mSubP [70] is functional based on various hybrid features related to auto-correlation and quasi-sequence-order descriptors and dipeptide compo- sition (NCC-DIPEP) to attain better accuracy for multi-target localization. DeepLoc 2.0 [71] is multi-label subcellular lo- calization predictor that uses protein language models. It uses attention pooling of a protein sequence embedding, along with Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP) for predicting class probabilities and prediction accuracies.

CBOW [72] utilizes deep neural network based NLP method, and bi-LSTM, to accurately predict protein subcel- lular locations. It provides a pipeline that not only offers a high-throughput framework for linking biological entities from unstructured text but also facilitates the extraction of protein functional features. iLoc-Animal [73] is special- ized for animal proteins based on a multi-label K-nearest neighbour classifier while using sequence-based information. Multi-label predictors like these are capable of residing or transiting among two or more different subcellular locations simultaneously and are often known as multiplex proteins.

MFannot [74] is a tool capable of predicting protein lo- cations along with predicting DNA protein-coding genes. Its subcellular localization prediction for protein relies on pro- file Hidden Markov Models. This tool identifies incomplete protein models and then applies protein fusion methods to location information via HMMER. OrganelX [16] is a hy- brid predictor that uses two different approaches i.e. protein sequence embedding Unified Representation (UniRep) [75] and the Sequence-to-Vector (SeqVec) [76]. UniRep provides amino-acid embeddings that summarizes physicochemical properties. Whereas, SeqVec (Sequence-to-Vector) is based on context-dependent transfer-learning model ELMo which is a auto-regressive model. SeqVec uses ElMo as it allows processing of sequences of variable length. Also, it uses two layers of bidirectional LSTMs that introduce the context information. OrganelX also hosts two existing algorithms sub peroxisomal (In-Pero) [77] and sub-mitochondrial (In-Mito) [77]. These two predicting algorithms predict peroxisomal and mitochondrial proteins on OrganelX behalf. OrganelX along with In-Pero and In-Mito trains a model called Is-PTS that further uses logistic regression on the SVM scores.

2.2. Subcellular localization prediction tools for prokaryotes

Prokaryotes are organisms comprised of single prokaryotic cells without Endoplasmic reticulum, microtubules, perox- isomes, etc. Most prokaryotic predictors consider Gram- positive and Gram-negative bacteria for making subcellular predictions. PRED-LIPO [78] uses the Viterbi decoding algo- rithm and is based on the Hidden Markov Model method for the prediction of lipoprotein signal peptides of Gram-positive bacteria trained on experimentally verified proteins. LipoP [79] uses forward decoding, a method based on regular ex- pression patterns. MetaLocGramN [80] utilizes features from various other predictors namely PSORTb3 [81], PSLpred [82], CELLO [67], and SOSUI-GramN [83] to take maxi- mum advantage of all their combined strengths. It produces better prediction accuracy in comparison with predictors used individually.

There are few predictors that either target gram-negative bacteria or gram-positive bacteria. One such example is Gapped k-mer [84] which is a prediction tool for gram- negative bacteria. This tool uses the Peptide information ex- traction method with the amino acid composition of protein sequences and k-peptide information. However, SP Predic-tion [85] is for gram-positive bacteria only that achieve pre- diction by using signal peptides generated through attention- based neural networks (Transformer Model). It is a ma- chine translation model that generates SP (signal peptides) sequences, followed by identification and classification of the pathway used. This tool targets intracellular and extracellular locations both.

2.3. Subcellular localization prediction tools for viruses

As viruses are not actually cells. However, localization pre- diction usually refers to locations in their host cell, or in the virion. Subcellular localization of viral proteins is critical as they serve as biomarkers for viral infections. These kinds of predictions aid in the diagnosis of viral diseases and tracking treatment effectiveness. One such recent example is E-MuLA [20], which is an Ensemble-based multi-localized attention feature extraction network tool for Viral Protein Subcellular Localization. E-MuLA performance is checked against various state-of-the-art algorithms through rigorous comparisons with LSTM, CNN, AdaBoost, decision trees, KNN.

pLoc-mVirus is a deep learning-based subcellular localiza- tion predictor specifically for multi-location virus proteins. It incorporates curated GO information and has better results than iLoc-Virus [86]. iLoc-Virus uses sequential evolution information and is considered a powerful predictor for as- sessing the quality of multi-label predictors. Another recent tool is VIRify [87] uses virus-specific protein profile hidden Markov models. TIt is capable of identifying sequences from both prokaryotic and eukaryotic viruses along with detecting and classifying taxonomic ranges relevant to them.

2.4. Subcellular localization prediction tools for multi-categories

Subcellular localization prediction tools for multiple cate- gories are tools that are capable of making predictions in different areas simultaneously. However, most of the predic- tors (as illustrated in Fig. 3) are designed to target one category at a time such as Human proteins, Animals, Algae or gram-positive, gram-negative bacteria. Whereas, multiple categories predictors (as illustrated in Fig. 4) are meant to target Eukaryotes, Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative bacteria together. Bologna Unified Subcellular Component Annotator (BUSCA) [88] integrates various computational tools to predict subcellular localization for globular and membrane proteins. Although BUSCA can produce predic- tions for Eukaryotes, gram-positive and negative bacteria, it is not yet designed for predicting proteins localized in lysosomes and peroxisomes.

Fig. 4.

Tools for subcellular localization predictions supporting multi-categories.

R3p-Loc [58] extracts features from two ProSeq and ProSeq-GO databases to prove that these two databases func- tion similarly to using Swiss-Prot and GOA databases with less training time. mPLR-Loc [59] has an additional feature in prediction decisions to give probabilistic confidence scores for the prediction decisions (information about how the pre- diction decisions are made). mGOASVM [56] uses accession numbers, amino acid (AA) sequences, and a combination of both as input. Whereas, HybridGO-loc [57] adopts a hybrid approach to use GO term occurrences with the inter-term relationships by accessing GO frequencies in correspondence with the semantic similarity between them.

MultiLoc2 [65] detects the presence or absence of desired motifs via the MotifSearch Module integrated based on the amino acid composition. Sherloc2 [66] includes an additional text search module based on the PubMed abstract linked with the UniProt IDs. CELLO 2.5 [67] uses jury voting out of four votes given by amino acid composition, di-peptide com- position, partitioned amino acid composition, and sequence composition. Finally, SCLPred [89] is designed for mapping whole sequences (non-redundant sets of protein sequences) through a single functional class. SCLPred automatically compresses sequences into hidden feature vectors without considering resorting to predefined transformations.

Eukaryotic Subcellular Localization Prediction (SCL- Epred) [90] is based on an N-to-1 Neural Network Archi- tecture (N1-NN) similar to SCLpred. It is trained on tenfold cross-validation that mainly targets prediction of localization of proteins from least considered subgroups, i.e. Chroma- lveolates, Rhizaria, and Excavate supergroups (i.e. SAR- Excavates group) and SCL-Epred achieves better predictions within this area of choice. Another member of the SCLpred family of predictors is SCLpred-EMS [19], which specializes in eukaryotic protein prediction for the endomembrane sys- tem and secretory pathway versus all other amino acids se- quences, and is based on Deep N-to-1 Convolutional Neural Networks. A summary of recent protein subcellular localization prediction tools is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

A summary of subcellular localization prediction tools.

| Tools | Year | Categories | No. Locations/ Features Prediction (approx) | Methods/Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-MuLA [20] | 2024 | Virus | 06 | LSTM, CNN, KNN |

| ML-FGAT [91] | 2024 | Human Gram-positive bac- teria, Gram-negative bacte- ria, Virus, plant |

19 | Graph CNN |

| MFannot [74] | 2023 | Eukaryotes (any) | 01 | HMM, covariance |

| OrganelX [16] | 2023 | Eukaryotes (any) | 02 | SVM, Multi-class classifiers |

| Graph-BERT [92] | 2023 | Eukaryotes (any) | 03 | PPI Network, SeqVec |

| AdaPPI [93] | 2023 | Eukaryotes (any) | 05 | PPI Network |

| VIRify [87] | 2023 | Virus | 00 | protein profile HMM |

| SDN2GO [94] | 2023 | Human, Yeast | 06 | CNN, BiGRU |

| Mit Protein Trans- former [95] |

2023 | Eukaryotes (any) | 04 | Transformer Model, Deep CNN |

| DeepLoc 2.0 [71] | 2022 | Eukaryotes (any) | 10 | transformer language model |

| GraphLoc [21] | 2022 | Eukaryotes (any) | 08 | Graph CNN, BiLSTM |

| MSTLoc [96] | 2022 | Human | 08 | DNN, Deep Imaging-based Approach |

| PBLoc [97] | 2022 | Eukaryotes (any) | 10 | FFNN, BiGRU |

| SignalP 6.0 [98] | 2022 | Archaea, Eukaryotes, Gram- positive and Gram-negative bacteria |

16 | ProtTrans Models |

| MPSLP [99] | 2022 | Eukaryotes (any) | 05 | Self-attentionmechanism, DCNN, RAkEL |

| TooT-SC [100] | 2022 | Eukaryotes (any) | 12 | BERT |

| ProtPlat [101] | 2022 | Eukaryotes, Gram-negative, Gram-positive |

10 | BERT |

| SecProCT [102] | 2021 | Human | 02 | Transformer based models, CapsNet block |

| MULocDeep [103] | 2021 | Eukaryotes (any) | 10 | Self-attentionmechanism, LSTM |

| TripletProt [104] | 2021 | Human | 14 | FFNN |

| DeepPSP [104] | 2021 | Eukaryotes / Human | 01 | CapsNet block, Bi-LSTM block |

| AlexNet,VggNet, Xception, DenseNet [105] |

2021 | Human | 07 | DNN, Deep Imaging-based Approach |

| Transformer-XL, XLNet [106] |

2021 | archaea, bacteria, eukarya, viruses |

12 | ProtTrans Models |

| ProtTrans [107] | 2021 | archaea, bacteria, Eukary- otes, viruses |

12 | BERT |

| DeepPSL [63] | 2021 | Human | 10 | SAE networks |

| In-Pero [77] | 2021 | Eukaryotes (any) | 02 | PSSMs, SVM, Bi-LSTM |

| iDeepSubMito [18] | 2021 | Eukaryotes (any) | 04 | CNN, BiLSTM, ELMo |

| PSLOP [22] | 2021 | Eukaryotes (any) | 33 | BiLSTM, BiRNN, PSSM |

| SCLpred-MEM [19] | 2021 | Eukaryotes (any) | 02 | Deep N-to-1 CNN |

| PSORTdb 4.0 [108] | 2021 | Gram-positive,Gram- negative bacteria |

07 | Pattern matching |

| PSORTm [109] | 2020 | Prokaryotes and Archaea, Bacteria |

07 | HMM |

| SP Prediction [85] | 2020 | Gram-positive bacteria | 10 | ANN |

| ImPLoc [110] | 2020 | Human | 06 | FFN |

| CTM-AECA-PSSM- LDA [17] |

2020 | Eukaryotes (any) | 01 | Position-SpecificScoring Matrices (PSSMs), SVM |

| IM-Psepssm [111] | 2020 | Eukaryotes (any) | 01 | PSSMs, SVM |

| FSVM-KNR [112] | 2020 | Eukaryotes (any) | 33 | PSSMs |

| DCNN [113] | 2020 | Eukaryotes (any) | 07 | Ant-colonyoptimization, RAkEL |

| GasPhos [114] | 2020 | Human | 06 | Ant-colony optimization |

| DeepMito [115] | 2020 | Eukaryotes (any) | 01 | Deep CNN |

| ML-RBF [116] | 2020 | gram-positive bacteria and virus protein |

10 | Position-SpecificScoring Matrices (PSSMs) |

| HumLoc-LBCI [41] | 2020 | Human | 16 | GO |

| Plant-mSubP [70] | 2020 | Plants | 14 | K-mer Compositions |

| pLoc_Deep- mAnimal [117] |

2020 | Animals | 20 | BLSTM |

| SCLpred-EMS [19] | 2020 | Eukaryotes (any) | 18 | Deep N-to-1 CNN |

| BUSCA [88] | 2019 | Eukaryotes, Gram-positive bacteria,Gram-negative bacteria |

21 | Hybrid |

| SeqVec [76] | 2019 | Eukaryotes (any) | 10 | BERT, ELMo |

| TargetP 2.0 [118] | 2019 | Eukaryotic, Plants, Fungi | 04 | BiLSTM |

| GCGRandNSI [119] |

2019 | Eukaryotes (Human) | 06 | K-mer Composition, SVM |

| Gapped k-mer [84] | 2019 | Gram-negative | 06 | K-mer Composition |

| pLoc-mGneg | 2018 | Gram-Negative bacteria | 08 | MLT |

| SubCons [64] | 2017 | Human | 11 | RFC, Ensemble Method |

| DeepLoc [71] | 2017 | Eukaryotes (any) | 10 | FFN, BLSTM, A-BLSTM, Conv A-BLSTM |

| LOCALIZER [69] | 2017 | Plants | 03 | HMM |

| pLoc-mGpos [120] | 2017 | Gram-Positive bacteria | 04 | ML-GKR |

| iLoc-mGpos [120] | 2017 | Gram-Positive bacteria | 04 | KNN |

| pLoc-mVirus [121] | 2017 | Virus | 06 | ML-GKR |

| mGOF-loc [122] | 2016 | Human | 37 | PSSMs |

| mPLR-Loc [59] | 2015 | Virus and Plants | 12 | MLR |

| R3P-Loc [58] | 2014 | Eukaryotes and Plants | 22 | RP, ERR |

| HybridGO-Loc [57] | 2012 | Virus and Plants | 12 | GO, SVM |

Key:

LSTM: Long Short-Term Memory Networks, CNN: Convolutional Neural Network, KNN: K-Nearest Neighbour, HMM: Hidden Markov Model, SVM: Support Vector Machine, PPI: Protein-Protein Interactions,

BiGRRU: Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit, BiLSTM: Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Networks, BiRNN: Bidirectional Recurrent Neural Network, DCNN: Deep Convolutional Neural Networks,

RAkEL: Random k-labelsets, FFNN: Feed-Forward Neural Network, BERT: Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers, PSSMs: Position-Specific Scoring Matrices, ANN: Artificial Neural Network, ELMo: Embeddings from Language Models,

MLT: Multi-Label Theory, RFC: Random Forest classifier, MLR: Multi-Label Predictor,

MLGKR: Multi-Label Gaussian Kernel Regression, ERR: Ensemble Ridge Regression Classifier, CBOW: The Continuous Bag of Words.

Furthermore, SCLpred-MEM [123] is designed for pre- dicting membrane and non-membrane proteins. Among all other SCLpred family of predictors that are annotation-based, only SCLpredT [124] is template-based. In this case, the N-to-1 architecture is modified to accommodate template information, alongside its average quality/similarity to the query protein. DeepLoc [71] is based on convolutional motif detectors (a filter designed to position-specific scoring matri- ces for sequences) and selective attention to sequence regions (identifying protein regions) for making suitable predictions. SignalP 6.0 [98] is a tool that functions based on Signal peptides (SPs) that are short amino acid sequences. Sig- nal peptides are usually predicted through sequence data. SignalP 6.0 uses bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) protein language models (LM). BERT LM is available in ProtTrans (pretrained language models for proteins). BERT is based on transformers which is a deep learning model in which all output elements are connected with input elements and weightings between them are dy- namically calculated based upon their connections. Whereas, TargetP 2.0 [118], is a tool that predicts features embedded in the sequences and identifies N-terminal sorting signals. It detects the strongest signals and derives the classification based on that. It also uses BiLSTM to calculate the multi-attention matrix.

3. CHALLENGES AND RESEARCH GAPS

Based on the above-mentioned comprehensive study of sub- cellular localization prediction tools, various research chal- lenges and gaps are identified that require further attention and effort from researchers working within the field. As illustrated in Fig. 3, Fig. 4, homology-based methods (template-based) are generously present that predict various locations with better prediction accuracy. However, ab-initio- based predictors are quite less and the accuracy of their predictions is comparatively less than homology-based meth- ods, hybrid and meta-predictors. Ab-initio-based predictions (only amino acid sequence-based) require considerable atten- tion to cover the significant localization gap of unannotated proteins.

As illustrated in 2, the designing of prediction tools during the last 10 years has considerably grown. However, it can be witnessed that the homology modelling method is the most popular approach that provides advantages relevant to homology modelling with a simple algorithm, fast prediction speed, and high accuracy for proteins that have structure- known homologs [125]. However, the challenging part is that it strongly depends on the template structures, which means that it cannot predict structures of proteins whose homologs’ structures have not been determined [126]. Unlike homology modelling, trans modelling does not depend on the known protein structures but generates the 3D structure of a target protein only based on the established laws of physics (quantum mechanics) [127]. Available ab initio prediction methods tend to have low prediction accuracy in comparison with homology-based prediction methods [128]. Homology-based prediction methods achieve better percentages due to template-based identification of protein location. However, locating protein from sequences only is a challenging as well as tedious task to accomplish [129].

Even though trans modelling does not rely on the known protein structures, it has the possibility of finding new protein structural types [130]. Still, these methods are challenging in terms of free energy function i.e. accurate calculation of free energy would involve solving the Schrödinger’s equation, which requires a huge amount of calculation that is mostly not affordable. Secondly, the possible conformational num- ber of a protein with several hundred amino acids is estimated to be about 10300 [131]. However, great signs of progress have been made in conformational search algorithms, as well as computing power and storage space. Even though there are a lot of subcellular prediction tools and methods available, the Protein sorting process is still very complex and not yet completely understood [132]. Only a small portion of proteins have clearly identifiable sorting signals in their primary sequence [133].

As illustrated in Fig. 5, there exists a high possi- bility that homologous sequences share the same struc- ture/function. However, they might not belong to the same subcellular localization. This factor results in wrong clas- sifier training while stopping it from correctly annotating the subcellular localization [134]. Also, composition-based approaches are mostly confined to amino acid composition- based features that are eventually not representative of other important aspects for the prediction [135]. Another critical challenge linked to integrated-based methods is their ability to incorporate various features but eventually suffer from over-fitting problems [136]. Apart from these challenges, using redundant training sets, overestimating the prediction performance, lower accuracy score, unconscious bias in fea- ture selection, mispredicting the query point and human errors still create troubles for bio-informatics users [137].

Fig. 5.

Dendrogram for subcellular localization predictions challenges and research gaps.

Automating prediction processes with higher accuracy is a challenging domain in computational biology as tradi- tional approaches are labour-intensive and extremely time- consuming [138]. Generating reliable and automated meth- ods capable of overcoming computational difficulty still needs various advancements for better prediction results. Fig. 5 also indicates that structural or sequence homology can be inaccurate since proteins with significant amino acid sequence identity possibly can have different functions [139]. Interestingly, some of the proteins also carry two biochemical or biophysical functions that add more complications to the prediction process. while few of the proteins can have no functions at all [140]. There might be a case that proteins claimed to have no functions are not fully characterized as others for now.

Challenges related to protein data pose serious concerns for subcellular localization predictions. Firstly, data quality is compromised due to the limited availability of high-quality labeled datasets for training predictive models, result in hin- dering prediction accuracy. Additionally, biased predictions are challenging due to imbalanced datasets, where certain subcellular locations have more examples than others, lead- ing to biased predictions. Secondly, predicting localization for novel proteins without experimental data is challenging and requires robust and complex computational methods. Extending prediction models to handle limited experimental data or different cellular architectures is also considered difficult in subcellular localization predictions.

4. Conclusion

We have concluded that despite numerous challenges, tools for protein structure prediction and design have advanced considerably in the recent decade. This article analyzed and explored various subcellular localization predictors based on their domain, methodologies adopted, accuracy achieved, and the number of locations successfully targeted by the predictors. A very well-directed and broad-spectrum tools- based diagrammatic illustrations are given in the article that can potentially help the readers to decide the tools of their choice with up-to-date review. A brief discussion is added that covers all major categories (Eukaryotes, Prokaryotes, and Viruses) of subcellular localization prediction to facil- itate researchers and bioinformaticians with better choices for accomplishing subcellular localization predictions. Soon, the rapidly increasing amount of diverse experimental protein data and advancements in computational methods and tools that make use of these data may result in improved accuracy and reliability of subcellular localization predictions.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Maryam Gillani: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Gianluca Pollastri: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

We here by declare that we do not have any conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This work was supported by University College Dublin, Ireland.

Contributor Information

Maryam Gillani, Email: maryam.gillani@ucdconnect.ie.

Gianluca Pollastri, Email: gianluca.pollastri@ucd.ie.

References

- 1.Afify H.M., Abdelhalim M.B., Mabrouk M.S., Sayed A.Y. Protein secondary structure prediction (pssp) using different machine algorithms. Egypt J Med Hum Genet. 2021;vol. 22(1):10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torrisi M., Pollastri G., Le Q. Deep learning methods in protein structure prediction. Comput Struct Biotechnol Jour- Nal. 2020;vol. 18:1301–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao W., Mahajan S.P., Sulam J., Gray J.J. Deep learning in protein structural modeling and design. Patterns. 2020;vol. 1(9) doi: 10.1016/j.patter.2020.100142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pakhrin S.C., Shrestha B., Adhikari B., Kc D.B. Deep learning- based advances in protein structure prediction. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;vol. 22(11):5553. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu C.-H., Chen W., Chiang Y.-H., Guo K., Martin Moldes Z., Kaplan D.L., et al. End-to-end deep learning model to predict and design secondary structure content of structural proteins. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2022;vol. 8(3):1156–1165. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.1c01343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao B., Kurgan L. Deep learning in prediction of intrinsic dis- order in proteins. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;vol. 20:1286–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bongirwar V., Mokhade A. Different methods, techniques and their limitations in protein structure prediction: a review. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2022;vol. 173:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2022.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu B., Xia J., Zheng J., Tan C., Huang Y., Xu Y., et al. Protein language models and structure prediction: connection and progression. arXiv Prepr arXiv:2211 16742. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avery C., Patterson J., Grear T., Frater T., Jacobs D.J. Protein function analysis through machine learning. Biomolecules. 2022;vol. 12(9):1246. doi: 10.3390/biom12091246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suh D., Lee J.W., Choi S., Lee Y. Recent applications of deep learning methods on evolution-and contact-based protein structure pre- diction. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;vol. 22(11):6032,. doi: 10.3390/ijms22116032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.S. Kumar, D. Guruparan, P. Aaron, P. Telajan, K. Mahadevan, D. Davagandhi, and O.X. Yue, Deep learning in computational bi- ology: Advancements, challenges, and future outlook, arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.03086, 2023.

- 12.Yang Z., Zeng X., Zhao Y., Chen R. Alphafold2 and its applications in the fields of biology and medicine. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;vol. 8(1):115. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01381-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryant P., Pozzati G., Elofsson A. Improved prediction of protein- protein interactions using alphafold2. Nat Commun. 2022;13:1265. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28865-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senior A.W., Evans R., Jumper J., Kirkpatrick J., Sifre L., Green T., et al. Improved pro- tein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature. 2020;vol. 577(7792):706–710. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1923-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makigaki S., Ishida T. Sequence alignment using machine learning for accurate template-based protein structure prediction. Bioinformatics. 2020;vol. 36(1):104–111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anteghini M., Haja A., Dos Santos V.A.M., Schomaker L., Sac- centi E. Organelx web server for sub-peroxisomal and sub-mitochondrial protein localization and peroxisomal target signal detection. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2023;vol. 21:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2022.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du L., Meng Q., Chen Y., Wu P. Subcellular location prediction of apoptosis proteins using two novel feature extraction methods based on evolutionary information and lda. BMC Bioinforma. 2020;vol. 21:1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12859-020-3539-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou Z., Yang Y., Li H., Wong K.-c, Li X. ideepsubmito: iden- tification of protein submitochondrial localization with deep learning. Brief Bioinforma. 2021;vol. 22(6) doi: 10.1093/bib/bbab288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaleel M., Zheng Y., Chen J., Feng X., Simpson J.C., Pollas- tri G., et al. Sclpred-ems: subcellular localization prediction of endomembrane system and secretory pathway proteins by deep n- to-1 convolutional neural networks. Bioinformatics. 2020;vol. 36(11):3343–3349. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakanina Kissanga G.-M., Zulfiqar H., Gao S., Yussif S.B., Momanyi B.M., Ning L., et al. E-mula: an ensemble multi-localized attention feature extraction network for viral protein subcellular localization. Information. 2024;vol. 15(3) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang T., Gu J., Wang Z., Wu C., Liang Y., Shi X. Protein subcellu- lar localization prediction model based on graph convolutional network. Interdiscip Sci Comput Life Sci. 2022;vol. 14(4):937–946. doi: 10.1007/s12539-022-00529-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao Z., Pan G., Sun C., Tang J. Predicting subcellular location of protein with evolution information and sequence-based deep learning. BMC Bioinforma. 2021;vol. 22:1–23. doi: 10.1186/s12859-021-04404-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen Y.Q., Burger G. Unite and conquer: enhanced prediction of protein subcellular localization by integrating multiple specialized tools. BMC Bioinforma. 2007;vol. 8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu J., Kang S., Tang C., Ellis L.B., Li T. Meta-prediction of protein subcellular localization with reduced voting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;vol. 35(15) doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shatkay H., Höglund A., Brady S., Blum T., Dönnes P., Kohlbacher O. Sherloc: high-accuracy prediction of protein subcellular localization by integrating text and protein sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2007;vol. 23(11):1410–1417. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guda C., Subramaniam S. Target: a new method for predicting protein subcellular localization in eukaryotes. Bioinformatics. 2005;vol. 21(21):3963–3969. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhasin M., Raghava G. Eslpred: Svm-based method for subcellular localization of eukaryotic proteins using dipeptide composition and psi- blast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;vol. 32(suppl_2):W414–W419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen Y., Ding Y., Tang J., Zou Q., Guo F. Critical evaluation of web-based prediction tools for human protein subcellular localization. Brief Bioinforma. 2019;vol. 21(11):1628–1640. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbz106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barberis E., Marengo E., Manfredi M. Protein subcellular localiza- tion prediction. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;vol. 2361:197–212. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1641-3_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar R., Dhanda S.K. Bird eye view of protein subcellular localization prediction. Life. 2020;vol. 10(12) doi: 10.3390/life10120347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan G., Sun C., Liao Z., Tang J. Springer US; New York, NY: 2021. Machine and deep learningdeep learning (DL) for prediction of subcellular localization; pp. 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakai K., Wei L. Recent advances in the prediction of subcellular localization of proteins and related topics. Front Bioinforma. 2022;vol. 2 doi: 10.3389/fbinf.2022.910531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahmoud S.S., Portelli B., D’Agostino G., Pollastri G., Serra G., Fogolari F. A comparison of mutual information, linear models and deep learning networks for protein secondary structure prediction. Curr Bioinforma. 2023;vol. 18(8):631–646. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan T.-C., Yue Z.-X., Xu H.-Q., Liu Y.-H., Hong Y.-F., Chen G.-X., et al. A systematic review of state-of-the-art strategies for machine learning-based protein function prediction. Comput Biol Med. 2023;vol. 154 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.106446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torrisi M., Pollastri G., Le Q. Deep learning methods in protein structure prediction. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;vol. 18:1301–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2019.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.M. Torrisi and G. Pollastri, Protein structure annotations, Essentials of Bioinformatics, Volume I: Understanding Bioinformatics: Genes to Proteins, pp. 201–234, 2019.

- 37.Ovchinnikov S., Huang P.-S. Structure-based protein design with deep learning. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2021;vol. 65:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2021.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh I., Pollastri G., Tosatto S.C. Correct machine learning on protein sequences: a peer-reviewing perspective. Brief Bioinform. 2016;vol. 17(5):831–840. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbv082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin A.J., Mooney C., Walsh I., Pollastri G. Contact map predic- tion by machine learning. Introd Protein Struct Predict: Methods Algorithms. 2010:137–163. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elofsson A. Progress at protein structure prediction, as seen in casp15. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2023;vol. 80 doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2023.102594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen Y., Ding Y., Tang J., Zou Q., Guo F. Critical evaluation of web-based prediction tools for human protein subcellular localization. Brief Bioinforma. 2020;vol. 21(5):1628–1640. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbz106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang Y., Wang D., Wang W., Xu D. Computational methods for protein localization prediction. Comput Struct Biotech- nology J. 2021;vol. 19:5834–5844. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding H., Deng E.-Z., Yuan L.-F., Liu L., Lin H., Chen W., et al. ictx-type: a sequence-based predictor for identifying the types of conotoxins in targeting ion channels. BioMed Res Int. 2014;vol. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/286419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bannai H., Tamada Y., Maruyama O., Nakai K., Miyano S. Exten- sive feature detection of n-terminal protein sorting signals. Bioinformat- ics. 2002;vol. 18(2):298–305. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petsalaki E.I., Bagos P.G., Litou Z.I., Hamodrakas S.J. Predsl: a tool for the n-terminal sequence-based prediction of protein subcellular localization. Genom, Proteom Bioinforma. 2006;vol. 4(1):48–55. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(06)60016-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cokol M., Nair R., Rost B. Finding nuclear localization signals. EMBO Rep. 2000;vol. 1(5):411–415. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei L., Ding Y., Su R., Tang J., Zou Q. Prediction of human protein subcellular localization using deep learning. J Parallel Distrib Comput. 2018;vol. 117:212–217. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu Z., Hunter L. in Biocomputing 2005. World Scientific,; 2005. Go molecular function terms are predictive of subcellular localization; pp. 151–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Briesemeister S., Rahnenführer J., Kohlbacher O. Going from where to why—interpretable prediction of protein subcellular localiza- tion. Bioinformatics. 2010;vol. 26(9):1232–1238. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nielsen H. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins by bioinfor- matic algorithms. Protein Sugar Export Assem Gram- Posit Bact. 2017:129–158. doi: 10.1007/82_2015_5006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pun C.S., Lee S.X., Xia K. Persistent-homology-based machine learning: a survey and a comparative study. Artif Intell Re- view. 2022;vol. 55(7):5169–5213. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nielsen H., Tsirigos K.D., Brunak S., von Heijne G. A brief history of protein sorting prediction. Protein J. 2019;vol. 38:200–216. doi: 10.1007/s10930-019-09838-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Imai K., Nakai K. Prediction of subcellular locations of proteins: where to proceed. Proteomics. 2010;vol. 10(22):3970–3983. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wan S., Mak M.-W., Kung S.-Y. mlasso-hum: a lasso-based interpretable human-protein subcellular localization predictor. J Theor Biol. 2015;vol. 382:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2015.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shen H.-B., Chou K.-C. A top-down approach to enhance the power of predicting human protein subcellular localization: Hum-mploc 2.0. Anal Biochem. 2009;vol. 394(2):269–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.07.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wan S., Mak M.-W., Kung S.-Y. mgoasvm: multi-label protein subcellular localization based on gene ontology and support vector ma- chines. BMC Bioinforma. 2012;vol. 13(1):16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wan S., Mak M.-W., Kung S.-Y. Hybridgo-loc: mining hybrid features on gene ontology for predicting subcellular localization of multi- location proteins. PloS One. 2014;vol. 9(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wan S., Mak M.-W., Kung S.-Y. R3p-loc: a compact multi- label predictor using ridge regression and random projection for protein subcellular localization. J Theor Biol. 2014;vol. 360:34–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wan S., Mak M.-W., Kung S.-Y. mplr-loc: an adaptive decision multi-label classifier based on penalized logistic regression for protein subcellular localization prediction. Anal Biochem. 2015;vol. 473:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.He J., Gu H., Liu W. Imbalanced multi-modal multi-label learning for subcellular localization prediction of human proteins with both single and multiple sites. PloS One. 2012;vol. 7(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wan S., Mak M.-W., Zhang B., Wang Y., Kung S.-Y. Vol. 2013. IEEE; 2013. An ensem- ble classifier with random projection for predicting multi-label protein subcellular localization; pp. 35–42. (IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li L., Zhang Y., Zou L., Li C., Yu B., Zheng X., et al. An ensemble classifier for eukaryotic protein subcellular location prediction using gene ontology categories and amino acid hydrophobicity. PLoS One. 2012;vol. 7(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang W., Qu Q., Zhang Y., Wang W. The linear neighborhood propagation method for predicting long non-coding rna–protein interac- tions. Neurocomputing. 2018;vol. 273:526–534. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salvatore M., Warholm P., Shu N., Basile W., Elofsson A. Subcons: a new ensemble method for improved human subcellular localization predictions. Bioinformatics. 2017;vol. 33(16):2464–2470. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blum T., Briesemeister S., Kohlbacher O. Multiloc2: integrating phylogeny and gene ontology terms improves subcellular protein local- ization prediction. BMC Bioinforma. 2009;vol. 10(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Briesemeister S., Blum T., Brady S., Lam Y., Kohlbacher O., Shatkay H. Sherloc2: a high-accuracy hybrid method for predicting subcellular localization of proteins. J Proteome Res. 2009;vol. 8(11):5363–5366. doi: 10.1021/pr900665y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu C.-S., Chen Y.-C., Lu C.-H., Hwang J.-K. Prediction of protein subcellular localization. Protein Struct Funct Bioinform. 2006;vol. 64(3):643–651. doi: 10.1002/prot.21018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goldberg T., Hamp T., Rost B. Loctree2 predicts localization for all domains of life. Bioinformatics. 2012;vol. 28(18):i458–i465. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sperschneider J., Catanzariti A., DeBoer K., Petre B., Gardiner D., Singh K., et al. vol. 7. Nature Publishing Group; 2017. Localizer: subcellular localization prediction of both plant and effector proteins in the plant cell; pp. 1–14. (sci rep). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sahu S.S., Loaiza C.D., Kaundal R. Plant-msubp: a computational framework for the prediction of single-and multi-target protein subcel- lular localization using integrated machine-learning approaches. AoB Plants. 2020;vol. 12(3) doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plz068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Almagro Armenteros J.J., Sønderby C.K., Sønderby S.K., Nielsen H., Winther O. Deeploc: prediction of protein subcellular localization using deep learning. Bioinformatics. 2017;vol. 33(21):3387–3395. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.David R., Menezes R.-J.D., De Klerk J., Castleden I.R., Hooper C.M., Carneiro G., et al. Identifying protein subcellular locali- sation in scientific literature using bidirectional deep recurrent neural network. Sci Rep. 2021;vol. 11(1):1696. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80441-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin W.-Z., Fang J.-A., Xiao X., Chou K.-C. iloc-animal: a multi- label learning classifier for predicting subcellular localization of animal proteins. Mol Biosyst. 2013;vol. 9(4):634–644. doi: 10.1039/c3mb25466f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lang B.F., Beck N., Prince S., Sarrasin M., Rioux P., Burger G. Mitochondrial genome annotation with mfannot: a critical analysis of gene identification and gene model prediction. Front Plant Sci. 2023;vol. 14:1222186. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1222186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alley E.C., Khimulya G., Biswas S., AlQuraishi M., Church G.M. Unified rational protein engineering with sequence-based deep represen- tation learning. Nat Methods. 2019;vol. 16(12):1315–1322. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0598-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Heinzinger M., Elnaggar A., Wang Y., Dallago C., Nechaev D., Matthes F., et al. Modeling aspects of the language of life through transfer-learning protein sequences. BMC Bioinforma. 2019;vol. 20(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-3220-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anteghini M., Martins dos Santos V., Saccenti E. In-pero: ex- ploiting deep learning embeddings of protein sequences to predict the localisation of peroxisomal proteins. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;vol. 22(12):6409. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bagos P.G., Tsirigos K.D., Liakopoulos T.D., Hamodrakas S.J. Prediction of lipoprotein signal peptides in gram-positive bacteria with a hidden markov model. J Proteome Res. 2008;vol. 7(12):5082–5093. doi: 10.1021/pr800162c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rahman O., Cummings S.P., Harrington D.J., Sutcliffe I.C. Methods for the bioinformatic identification of bacterial lipoproteins encoded in the genomes of gram-positive bacteria. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;vol. 24:2377–2382. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Magnus M., Pawlowski M., Bujnicki J.M. Metalocgramn: a meta- predictor of protein subcellular localization for gram-negative bacte- ria. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA) Proteins Proteom. 2012;vol. 1824(12):1425–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yu N.Y., Wagner J.R., Laird M.R., Melli G., Rey S., Lo R., et al. Psortb 3.0: improved protein subcellular localization prediction with refined localization subcategories and predictive capabilities for all prokaryotes. Bioinformatics. 2010;vol. 26(13):1608–1615. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bhasin M., Garg A., Raghava G.P.S. Pslpred: prediction of subcellular localization of bacterial proteins. Bioinformatics. 2005;vol. 21(10):2522–2524. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Imai K., Asakawa N., Tsuji T., Akazawa F., Ino A., Sonoyama M., et al. Sosui-gramn: high performance prediction for sub- cellular localization of proteins in gram-negative bacteria. Bioinforma- tion. 2008;vol. 2(9):417. doi: 10.6026/97320630002417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yao Y.-h, Lv Y.-p, Li L., Xu H.-m, Ji B.-b, Chen J., et al. Protein sequence information extraction and subcellular localization prediction with gapped k-mer method. BMC Bioinforma. 2019;vol. 20:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12859-019-3232-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wu Z., Yang K.K., Liszka M.J., Lee A., Batzilla A., Wernick D., et al. Signal peptides generated by attention-based neural networks. ACS Synth Biol. 2020;vol. 9(8):2154–2161. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Xiao X., Wu Z.-C., Chou K.-C. iloc-virus: a multi-label learning classifier for identifying the subcellular localization of virus proteins with both single and multiple sites. J Theor Biol. 2011;vol. 284(1):42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rangel-Pineros G., Almeida A., Beracochea M., Sakharova E., Marz M., Muñoz Reyes, et al. Virify: an integrated detection, annotation and taxonomic classification pipeline using virus- specific protein profile hidden markov models. PLOS Comput Biol. 2023;vol. 19(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1011422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Savojardo C., Martelli P.L., Fariselli P., Profiti G., Casadio R. Busca: an integrative web server to predict subcellular localization of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;vol. 46(W1):W459–W466. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mooney C., Wang Y.-H., Pollastri G. Sclpred: protein subcellu- lar localization prediction by n-to-1 neural networks. Bioinformatics. 2011;vol. 27(20):2812–2819. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mooney C., Cessieux A., Shields D.C., Pollastri G. Scl-epred: a generalised de novo eukaryotic protein subcellular localisation predictor. Amino Acids. 2013;vol. 45:291–299. doi: 10.1007/s00726-013-1491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang C., Wang Y., Ding P., Li S., Yu X., Yu B. Ml-fgat: Iden- tification of multi-label protein subcellular localization by interpretable graph attention networks and feature-generative adversarial networks. Comput Biol Med. 2024;vol. 170 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.107944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jha K., Karmakar S., Saha S. Graph-bert and language model- based framework for protein–protein interaction identification. Sci Rep. 2023;vol. 13(1):5663. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-31612-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen H., Cai Y., Ji C., Selvaraj G., Wei D., Wu H. Adappi: identification of novel protein functional modules via adaptive graph convolution networks in a protein–protein interaction network. Brief Bioinforma. 2023;vol. 24(1) doi: 10.1093/bib/bbac523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sharma L., Deepak A., Ranjan A., Krishnasamy G. A novel hybrid cnn and bigru-attention based deep learning model for protein function prediction. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2023;vol. 22(1):20220057. doi: 10.1515/sagmb-2022-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang B., He L., Wang Q., Wang Z., Bao W., Cheng H. International conference on intelligent computing. Springer; 2023. Mit pro- tein transformer: Identification mitochondrial proteins with transformer model; pp. 607–616. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang F., Wei L. Multi-scale deep learning for the imbalanced multi- label protein subcellular localization prediction based on immunohisto- chemistry images. Bioinformatics. 2022;vol. 38(9):2602–2611. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang Z., Lin T., Yang X., Liang Y., Shi X. Protein subcellular localization prediction by combining protbert and bigru. IEEE Int Conf Bioinforma Biomed (BIBM) 2022;2022:86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Teufel F., Almagro Armenteros J.J., Johansen A.R., Gíslason M.H., Pihl S.I., Tsirigos K.D., et al. Signalp 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;vol. 40(7):1023–1025. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-01156-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cong H., Liu H., Cao Y., Chen Y., Liang C. Multiple protein subcellular locations prediction based on deep convolutional neural net- works with self-attention mechanism. Interdiscip Sci Comput Life Sci. 2022;vol. 14(2):421–438. doi: 10.1007/s12539-021-00496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.S. Ataei and G. Butler, Predicting the specific substrate for trans- membrane transport proteins using bert language model, in 2022 IEEE Conference on Computational Intelligence in Bioinformatics and Com- putational Biology (CIBCB), pp. 1–8, 2022.

- 101.Jin Y., Yang Y. Protplat: an efficient pre-training platform for protein classification based on fasttext. BMC Bioinforma. 2022;vol. 23(1):66,. doi: 10.1186/s12859-022-04604-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Du W., Zhao X., Sun Y., Zheng L., Li Y., Zhang Y. Secproct: In silico prediction of human secretory proteins based on capsule network and transformer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;vol. 22(16) doi: 10.3390/ijms22169054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jiang Y., Wang D., Yao Y., Eubel H., Künzler P., Møller I.M., et al. Mulocdeep: a deep-learning framework for protein subcellular and suborganellar localization prediction with residue-level interpretation. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;vol. 19:4825–4839. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nourani E., Asgari E., McHardy A.C., Mofrad M.R. Tripletprot: deep representation learning of proteins based on siamese networks. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinforma. 2022;vol. 19(6):3744–3753. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2021.3108718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Su R., He L., Liu T., Liu X., Wei L. Protein subcellular localization based on deep image features and criterion learning strategy. Brief Bioinforma. 2021;vol. 22(4) doi: 10.1093/bib/bbaa313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Elnaggar A., Heinzinger M., Dallago C., Rehawi G., Wang Y., Jones L., et al. Prottrans: toward understanding the language of life through self- supervised learning. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;vol. 44(10):7112–7127. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3095381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Elnaggar A., Heinzinger M., Dallago C., Rehawi G., Wang Y., Jones L., et al. Prottrans: toward understanding the language of life through self-supervised learning. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2021;vol. 44(10):7112–7127. doi: 10.1109/TPAMI.2021.3095381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lau W.Y.V., Hoad G.R., Jin V., Winsor G.L., Madyan A., Gray K.L., et al. Psortdb 4.0: expanded and redesigned bacterial and archaeal protein subcellular localization database incorporating new secondary localizations. Nucleic Acids Re- Search. 2021;vol. 49(D1):D803–D808. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Peabody M.A., Lau W.Y.V., Hoad G.R., Jia B., Maguire F., Gray K.L., et al. Psortm: a bacterial and archaeal protein subcellular localization prediction tool for metagenomics data. Bioinformatics. 2020;vol. 36(10):3043–3048. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Long W., Yang Y., Shen H.-B. Imploc: a multi-instance deep learning model for the prediction of protein subcellular localization based on immunohistochemistry images. Bioinformatics. 2020;vol. 36(7):2244–2250. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ruan X., Zhou D., Nie R., Guo Y., et al. Predictions of apop- tosis proteins by integrating different features based on improving pseudo-position-specific scoring matrix. Bio Med Res Int. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/4071508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ding Y., Tang J., Guo F. Human protein subcellular localization identification via fuzzy model on kernelized neighborhood representa- tion. Appl Soft Comput. 2020;vol. 96 [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cong H., Liu H., Chen Y., Cao Y. Self-evoluting framework of deep convolutional neural network for multilocus protein subcellular localization. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2020;vol. 58:3017–3038. doi: 10.1007/s11517-020-02275-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chen C.-W., Huang L.-Y., Liao C.-F., Chang K.-P., Chu Y.-W. Gasphos: protein phosphorylation site prediction using a new feature selection approach with a ga-aided ant colony system. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;vol. 21(21):7891. doi: 10.3390/ijms21217891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Savojardo C., Bruciaferri N., Tartari G., Martelli P.L., Casadio R. Deepmito: accurate prediction of protein sub-mitochondrial localization using convolutional neural networks. Bioinformatics. 2020;vol. 36(1):56–64. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Javed F., Ahmed J., Hayat M. Ml-rbf: Predict protein subcellular locations in a multi-label system using evolutionary features. Chem Intell Lab Syst. 2020;vol. 203 [Google Scholar]

- 117.Shao Y.-T., Chou K.-C. Ploc_deep-manimal: a novel deep cnn-blstm network to predict subcellular localization of animal proteins. Nat Sci. 2020;vol. 12(05):281–291. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Armenteros J.J.A., Salvatore M., Emanuelsson O., Winther O., Von Heijne G., Elofsson A., et al. Detecting sequence signals in targeting peptides using deep learning. Life Sci Alliance. 2019;vol. 2(5) doi: 10.26508/lsa.201900429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Li B., Cai L., Liao B., Fu X., Bing P., Yang J. Prediction of protein subcellular localization based on fusion of multi-view features. Molecules. 2019;vol. 24(5) doi: 10.3390/molecules24050919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Xiao X., Cheng X., Su S., Mao Q., Chou K.-C., et al. ploc-mgpos: incorporate key gene ontology information into general pseaac for predicting subcellular localization of gram-positive bacterial proteins. Nat Sci. 2017;vol. 9(09):330. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cheng X., Xiao X., Chou K.-C. ploc-mvirus: predict subcellular localization of multi-location virus proteins via incorporating the optimal go information into general pseaac. Gene. 2017;vol. 628:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.L. Wei, M. Liao, X. Gao, J. Wang, and W. Lin, mgof-loc: A novel ensemble learning method for human protein subcellular localization prediction, Neurocomputing, vol. 217, pp. 73–82, 2016. SI: ALLSHC.

- 123.Kaleel M., Ellinger L., Lalor C., Pollastri G., Mooney C. Sclpred- mem: subcellular localization prediction of membrane proteins by deep n-to-1 convolutional neural networks. Protein: Struct, Funct, Bioinforma. 2021;vol. 89(10):1233–1239. doi: 10.1002/prot.26144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Adelfio A., Volpato V., Pollastri G. Sclpredt: Ab initio and homology-based prediction of subcellular localization by n-to-1 neural networks. SpringerPlus. 2013;vol. 2(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pearce R., Zhang Y. Toward the solution of the protein structure prediction problem. J Biol Chem. 2021;vol. 297(1) doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Noé F., De Fabritiis G., Clementi C. Machine learning for protein folding and dynamics. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2020;vol. 60:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2019.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Bryant P., Pozzati G., Zhu W., Shenoy A., Kundrotas P., Elofsson A. Predicting the structure of large protein complexes using alphafold and monte carlo tree search. Nat Commun. 2022;vol. 13(1):6028,. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33729-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Askr H., Elgeldawi E., Aboul Ella H., Elshaier Y.A., Gomaa M.M., Hassanien A.E. Deep learning in drug discovery: an integrative review and future challenges. Artif Intell Rev. 2023;vol. 56(7):5975–6037. doi: 10.1007/s10462-022-10306-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Schön J.C. Structure prediction in low dimensions: concepts, issues and examples. Philos Trans R Soc A. 2023;vol. 381(2250):20220246. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2022.0246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Woolfson D.N. A brief history of de novo protein design: minimal, rational, and computational. J Mol Biol. 2021;vol. 433(20) doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Levinthal C. How to fold graciously. Mossbauer Spectrosc Biol Syst. 1969;vol. 67:22–24. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Imai K., Nakai K. Tools for the recognition of sorting signals and the prediction of subcellular localization of proteins from their amino acid sequences. Front Genet. 2020:1491. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.607812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kustatscher G., Collins T., Gingras A.-C., Guo T., Hermjakob H., Ideker T., et al. Understudied proteins: opportunities and challenges for functional pro- teomics. Nat Methods. 2022;vol. 19(7):774–779. doi: 10.1038/s41592-022-01454-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Jeffery C.J. Current successes and remaining challenges in protein function prediction. Front Bioinforma. 2023;vol. 3 doi: 10.3389/fbinf.2023.1222182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Watson J.L., Juergens D., Bennett N.R., Trippe B.L., Yim J., Eise- nach H.E., et al. Broadly applicable and accurate protein design by integrating structure prediction networks and diffusion generative models. BioRxiv. 2022 2022–12. 2022–12. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Pearce R., Zhang Y. Deep learning techniques have significantly im- pacted protein structure prediction and protein design. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2021;vol. 68:194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Qiu J., Li L., Sun J., Peng J., Shi P., Zhang R., et al. Large ai models in health informatics: applications, challenges, and the future. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2023 doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2023.3316750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Kumar R., Dhanda S.K. Bird eye view of protein subcellular localization prediction. Life. 2020;vol. 10(12):347. doi: 10.3390/life10120347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Depienne C., Mandel J.-L. 30 years of repeat expansion disorders: what have we learned and what are the remaining challenges? Am J Hum Genet. 2021;vol. 108(5):764–785. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Roca-Martinez J., Lazar T., Gavalda-Garcia J., Bickel D., Pancsa R., Dixit, et al. Challenges in describing the conformation and dynamics of proteins with ambiguous behavior. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;vol. 9:959956. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.959956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]