Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), condylar and mandibular movements in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients treated with mandibular advancement device (MAD) and to identify the influence of these anatomic factors on upper airway (UA) volume and polysomnographic outcomes after treatment.

Materials and methods

Twenty OSA patients were prospectively treated with MAD. Clinical examinations, cone-beam computed tomography, and polysomnography were performed before MAD treatment and after achieving therapeutic protrusion. Polysomnographic variables and three-dimensional measurements of the TMJ, mandible, and upper airway were statistically analyzed.

Results

Condylar rotation, anterior translation, and anterior mandibular displacement were directly correlated with total UA volume, while vertical mandibular translation was inversely correlated with the volume of the inferior oropharynx. MAD treatment resulted in an increase in the volume and area of the superior oropharynx. There was no statistically significant correlation between condylar rotation and translation and polysomnographic variables. With MAD, there was a significant increase in vertical dimension, changes in condylar position (rotation and translation), and mandibular displacement. The central and medial lengths of the articular eminence were inversely correlated with condylar rotation and translation, respectively. The lateral length of the eminence was directly correlated with condylar translation, and the lateral height was directly correlated with condylar rotation and translation.

Conclusion

Condylar and mandibular movements influenced UA volume. The articular eminence played a role in the amount of condylar rotation and translation.

Clinical relevance

Individualized anatomical evaluation of the TMJ proves to be important in the therapy of OSA with MAD.

Keywords: Mandibular advancement device, Mandibular condyle, Obstructive sleep apnea, Upper airway, Cone-beam computed tomography, Temporomandibular joint

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a respiratory disorder characterized by partial or complete obstruction of the upper airway (UA), which prevents normal ventilation during sleep. This obstruction leads to partial reduction (hypopnea) or complete cessation (apnea) of respiratory flow, resulting in cortical arousals and/or a drop in blood oxygen saturation [1]. Polysomnography (PSG) is considered the gold standard for diagnosing OSA [2]. This examination monitors respiratory and sleep parameters, including the evaluation of the Apnea–Hypopnea Index per hour (AHI) [3]. Based on AHI values, OSA can be classified as mild (AHI = 5–15 events/hour), moderate (AHI = 15–30 events/hour), and severe (AHI > 30 events/hour) [1].

Treatment selection for OSA is based on the severity of the disease, as well as patient cooperation and interest [4]. Intraoral appliances (IOA) have emerged as an alternative for patients with mild to moderate OSA who are resistant to continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment [5]. Among several IOAs, mandibular advancement devices (MADs) are appliances that generate mandibular protrusion, thereby increasing the volume of the UA and improving the clinical symptoms of OSA [5]. Knowledge of the biomechanics of MADs and the anatomy of structures that can influence the treatment of OSA is essential for therapeutic success since individual characteristics of each patient can impact the prognosis and success of this approach.

Cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) proves to be an important tool for analyzing soft and skeletal tissues, allowing for precise, simple, and fast three-dimensional evaluation of craniofacial anatomical structures and the UA. This three-dimensional (3D) analysis facilitates both the planning and the predictability of OSA treatment. Additionally, CBCT provides lower radiation doses and reduced costs compared to conventional computed tomography [6, 7].

The treatment with MAD aims to improve the signs and symptoms of OSA through mandibular advancement, making the anatomy of the temporomandibular complex an important factor to be evaluated for clinical decision-making regarding the treatment to be applied. However, the exact correlation between the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), mandibular advancement therapies, and UA patency is not yet fully understood [8, 9]. In this context, the objective of this study is to evaluate, using 3D images, the anatomical structures of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), condylar and mandibular movements with MAD use for OSA treatment, as well as to assess the possible correlation of these anatomic factors with UA volume and PSG parameters.

Materials and methods

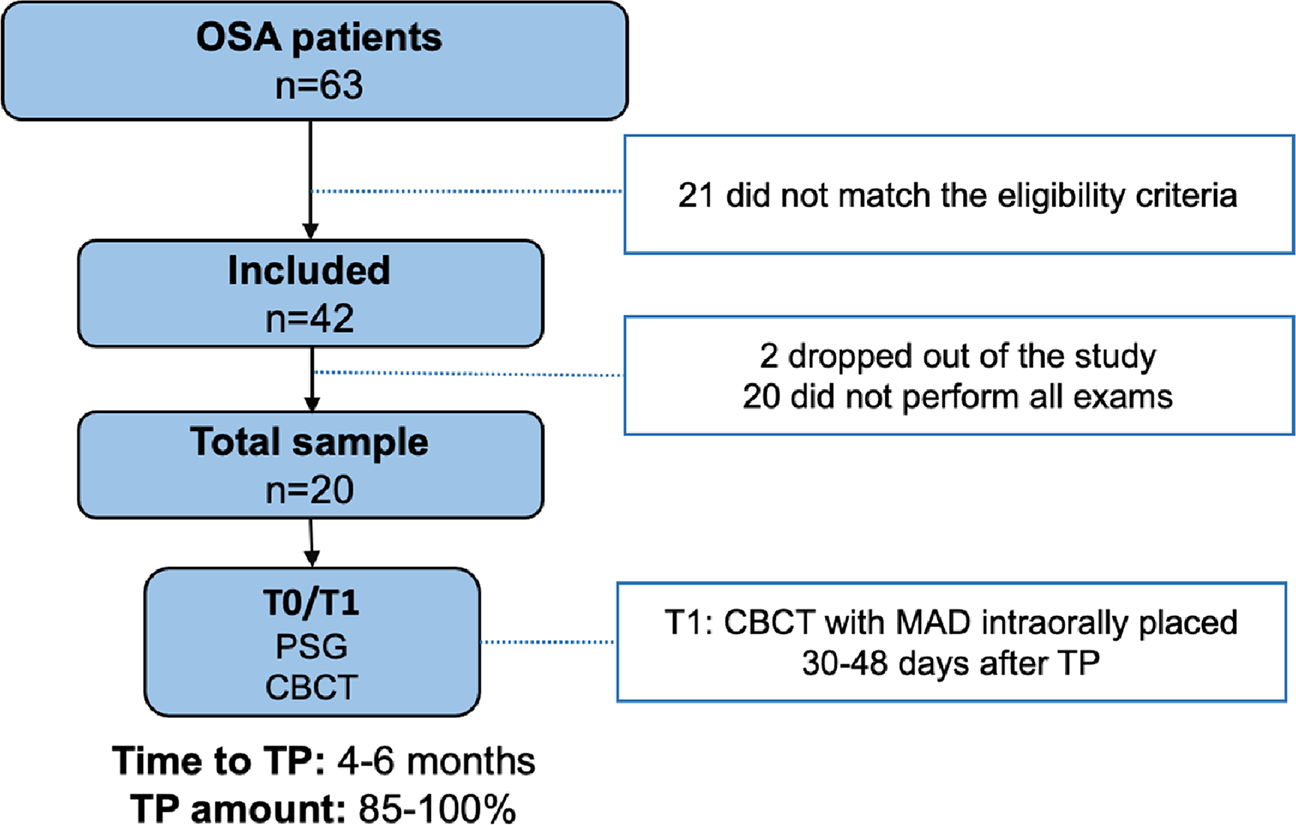

This observational longitudinal study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil (number 0301/10), and all patients were provided with a written Informed Consent Form (IFC), which they were required to sign in order to participate in the study. Patients who had previously been diagnosed with OSA and were referred for MAD therapy were selected. Initially, 63 patients were recruited, but 21 patients did not meet the study’s eligibility criteria, resulting in the selection of 42 patients. However, 20 patients did not undergo all the necessary exams, and 2 patients dropped off from the study, resulting in a final sample of 20 patients (9 males and 11 females) (Fig. 1). The patients underwent clinical, polysomnographic, and CBCT examinations before starting MAD treatment (T0) and after achieving therapeutic protrusion (TP) (T1), with the exams being performed with the appliance placed in the oral cavity. At T0, the sample included 15 patients with mild OSA, 3 with moderate OSA, and 2 with severe OSA (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Study flowchart. CBCT, cone beam computed tomography; MAD, mandibular advancement device; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea; PSG, polysomnography; TP, therapeutic protrusion

Table 1.

Demographic and anthropometric distribution according to OSA severity in the study sample

| T0 –OSA Severity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Total sample (n = 20) | Mild (n = 15) | Moderate (n = 3) | Severe (n = 2) | |

|

| ||||

| Age | 48.35 ± 10.42 | 48.27 ± 11.50 | 50 ± 8.88 | 46.5 ± 4.5 |

| Weight | 72.90 ± 15.41 | 72.87 ± 16.07 | 65.33 ± 14.01 | 84.5 ± 5.5 |

| Height | 1.64 ± 0.10 | 1.62 ± 0.09 | 1.65 ± 0.18 | 1.72 ± 0.02 |

| BMI | 27.10 ± 4.29 | 9.93 ± 4.95 | 23.8 ± 1.73 | 28.7 ± 2.4 |

| Gender (M/F) | 9/11 | 6/9 | 1/2 | 2/0 |

T0 patient follow-up before initiating treatment, OSA obstructive sleep apnea, BMI body mass index, M male, F female

The study analyzed demographic, tomographic, and polysomnographic variables. The demographic variables included information such as sex, age, weight, height, and body mass index (BMI) of the individuals. The three-dimensional image variables encompassed linear and angular measurements of the cranial base, TMJ, and mandible, as well as linear and volumetric measurements of the airways. Finally, the polysomnographic variables consisted of the AHI and minimum and average oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2).

Inclusion criteria

Eligible for the research were adult patients of both genders, aged between 18 and 65 years, with a body mass index (BMI) ≤ 35 kg/m2, and clinically and polysomno-graphically diagnosed with OSA (AHI ≥ 5/h) according to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders. They also had a negative diagnosis for temporomandibular disorders, as determined by the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders—RDC/TMD questionnaire (adapted to the Portuguese language) [10], and a minimum mandibular protrusion of 7 mm (measured from maximal retrusion to maximal protrusion), clinically assessed with the George Gauge® device (Great Lakes Orthodontics).

Exclusion criteria

Patients using psychoactive medication or medications that induce or reduce sleep or could modify the electroencephalographic pattern were excluded from the study. Those who had undergone any previous surgical treatment for OSA were also excluded. Additionally, patients with unsatisfactory dental conditions (such as active periodontal disease, cavities, or an insufficient number of teeth for MAD retention) and/or a crown-to-root ratio of 1 to 1 or inverted (2 to 1) were excluded.

Sample size calculation and patient selection

The sample size calculation was based on the study by Consellu et al. [11], where a significant increase in the mean volume of the airways (+ 1261.6 ± 1476.2 mm3) was observed in 16 patients with OSA after treatment with MAD. Therefore, it was estimated that a minimum of 16 patients evaluated at two time points would be needed to obtain a sample with a 95% confidence interval and 90% power (paired t-tests). Thus, the total sample of the study consisted of 20 patients, with a mean age of 48.35 ± 10.42 and a mean BMI of 27.10 ± 4.29.

Polysomnographic examination

All-night PSG was performed at the Instituto do Sono de São Paulo using digital-based polysomnography equipment (Embla® N7000, Embla Systems, Inc., Broomfield, CO, USA). Surface electrodes were used to record electroencephalography, submental and tibial electromyography, bilateral electrooculogram, and electrocardiography. Breathing was monitored with a nasal cannula, and nasal flow was measured using a pressure transducer and oronasal thermistor. Respiratory effort was assessed using chest and abdomen inductance plethysmography. Pulse oximetry was used to measure oxyhemoglobin saturation. The analysis of the polysomnographic examination data and the diagnosis of OSA were performed by specialized physicians. Apnea was defined as a complete cessation of airflow for at least 10 s, while hypopnea was defined as a decrease in airflow by 30% or more for at least 10 s, followed by a reduction of 4% or more in SpO2. The Apnea–Hypopnea Index (AHI) was defined as the number of obstructive events (apnea and hypopnea) occurring per hour of sleep. S pO2 was defined as the percent of hemoglobin in the blood that is carrying oxygen. Minimum S pO2 was defined as the lowest observed SpO2 value during the examination, while mean SpO2 was defined as the average value of S pO2 recorded throughout the examination [1]. In this study, treatment success was defined as an AHI reduction below 5 obstructive events per hour. Responders were classified based on an AHI reduction ≥ 50% from baseline or achieving an AHI of < 10 events per hour [12, 13].

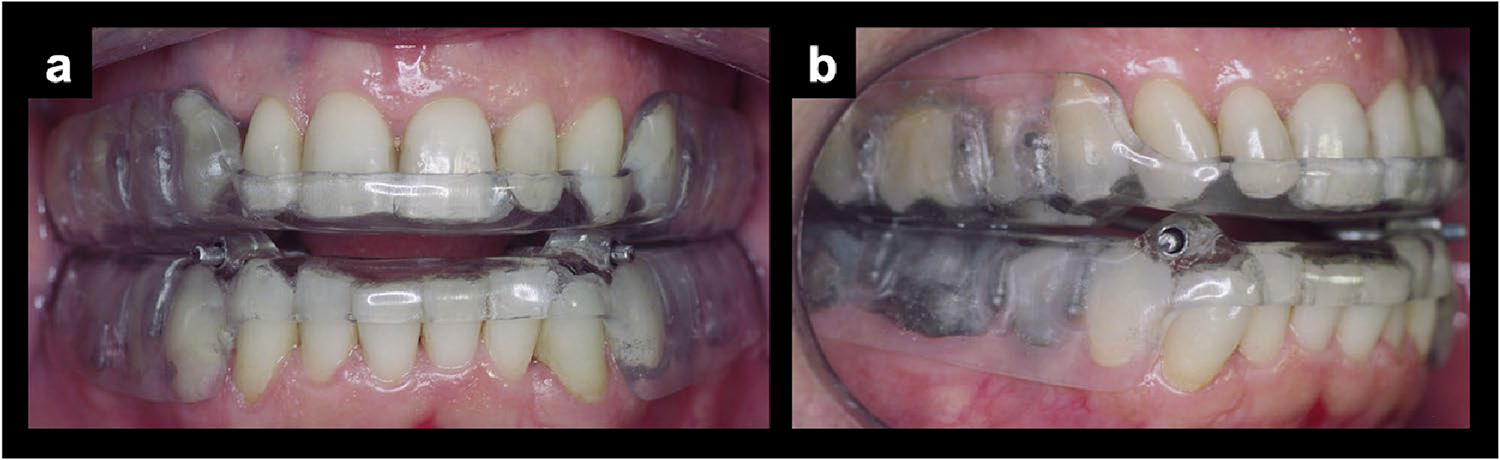

Mandibular advancement device and measurement of protrusion amount

The mandibular advancement device used in this study was the Brazilian Dental Appliance (BRD) [4], which is an individualized intraoral appliance designed to gradually advance the mandible (Fig. 2). It consists of two acrylic bases, one in each dental arch, that cover all the teeth. The appliance incorporates anteroposterior expansion screws on both sides. Additionally, the design of the appliance allows for small lateral movements by the patient [4]. The MAD was installed with an initial advancement of 50% of the maximum mandibular protrusion capacity, until reaching the therapeutic protrusion, which ranged from 85 to 100% of the maximum mandibular protrusion amount.

Fig. 2.

a Frontal view of the Brazilian Dental Appliance (BRD) placed in an OSA patient; b lateral view of the Brazilian Dental Appliance (BRD) placed in an OSA patient

Acquisition of tomographic images

The CBCT scans were performed at a private dental radiology clinic using an i-CAT® scanner (Imaging Sciences International, Hatfield, PA). The scanner was configured with 120 kVp, 3–8 mA, a voxel size of 0.4 mm, and a field of view (FOV) of 23 cm × 17 cm, allowing for full vertical framing of the head [14, 15]. The images were acquired in the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) format. The scans were performed before the initiation of OSA treatment with MAD (T0) and after achieving TP (T1). At T0, the scan was performed with the mandible occluded in maximum intercuspidation, and at T1, with the intraoral appliance in place [9, 15, 16]. During the image acquisition, the patients were required to be awake, with the head in a natural position (Frankfurt horizontal plane parallel to the ground) and with their gaze fixed on the horizon line. Additionally, they were instructed not to move, swallow, or take deep breaths during the scan to avoid changes in the airway space [17, 18].

Image processing

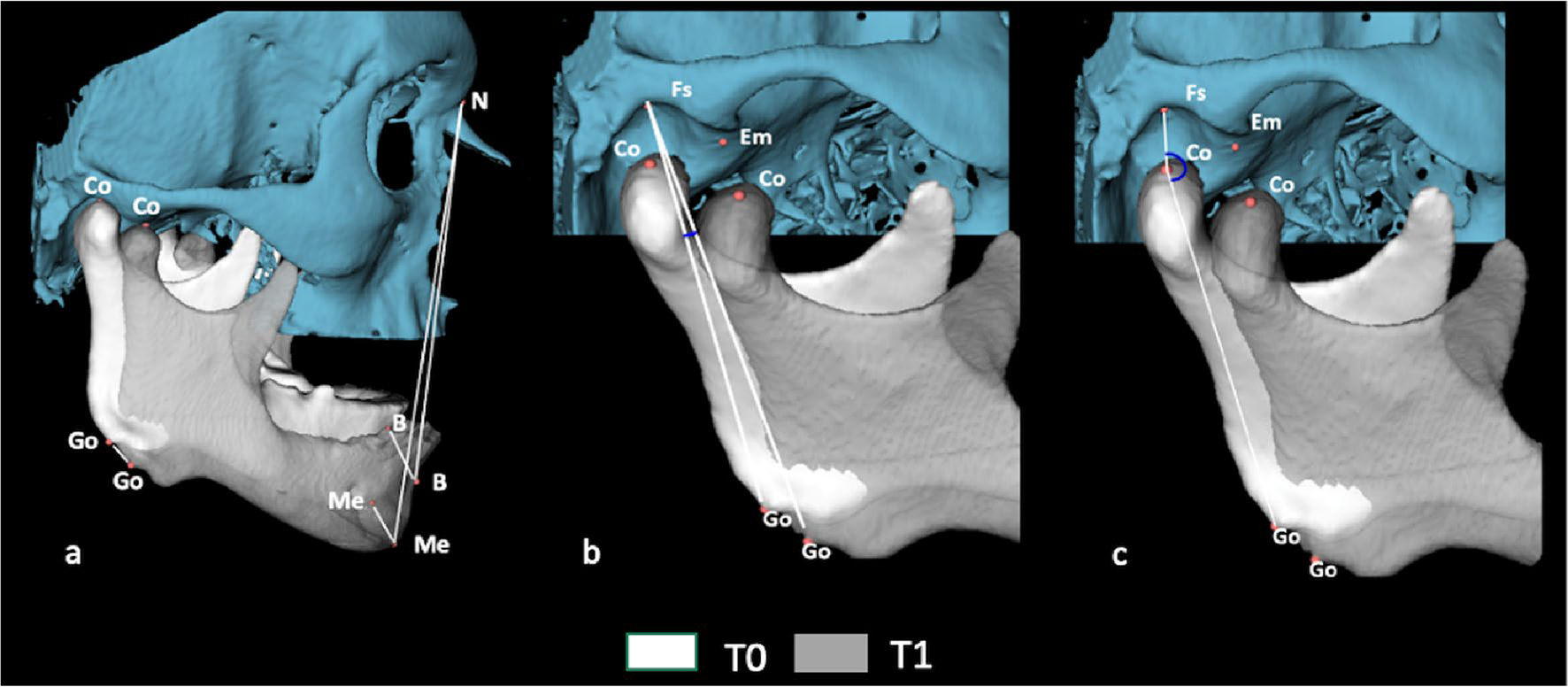

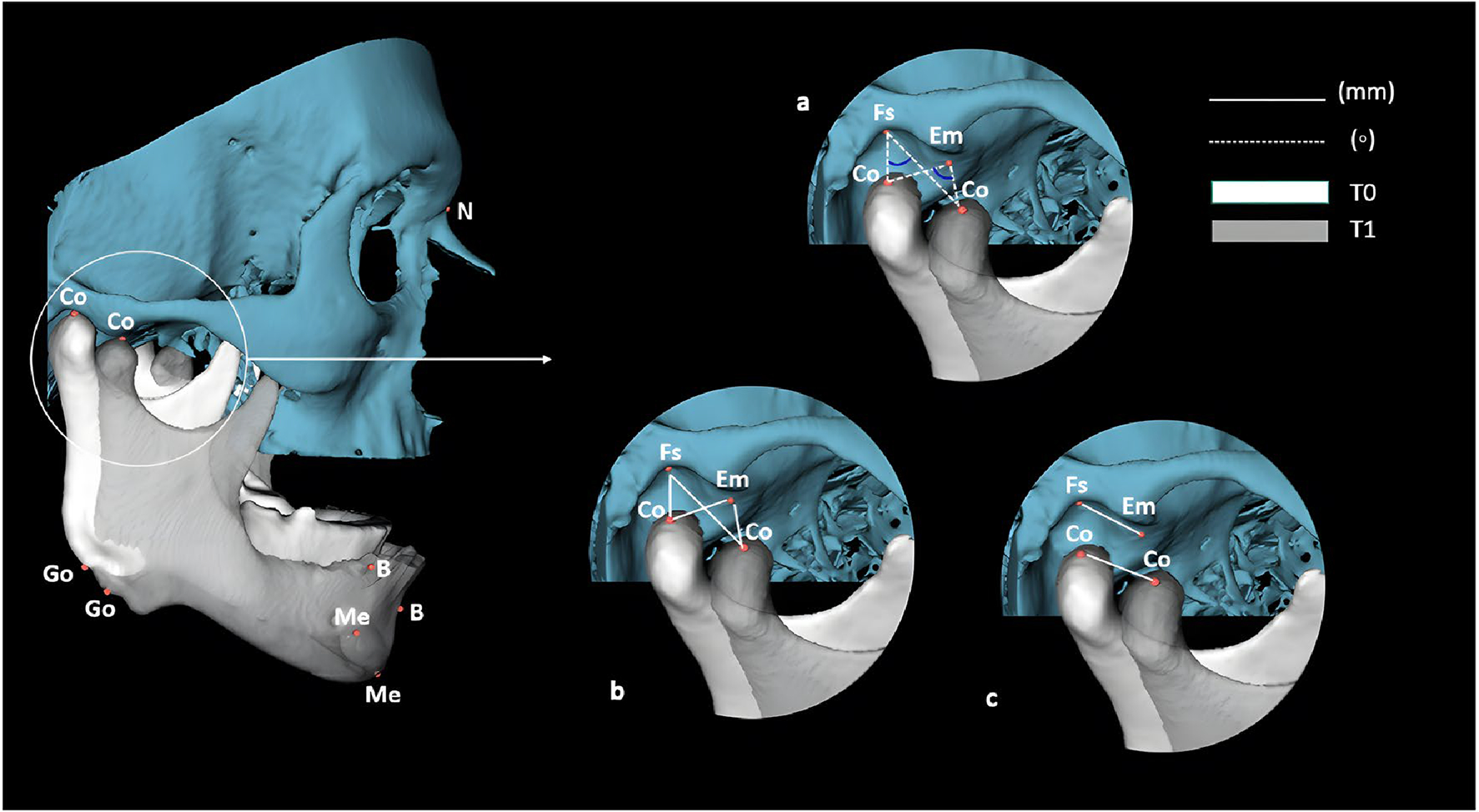

Cranial base, TMJ, and mandible measurements

For bilateral measurements, the arithmetic mean of both sides was calculated. The following parameters were analyzed in the skull base, TMJ, and mandible: vertical dimension, height of the articular eminence, condylar rotation and translation, mandibular advancement, rotation, and translation (Table 2). Linear measurements were assigned positive and negative signs. Positive values indicated anterior movements in anteroposterior displacement, while negative values indicated posterior movements. For superoinferior displacement, positive values indicated superior movements, and negative values indicated inferior movements (Figs. 3, 4, and 5).

Table 2.

3D craniofacial measurements performed in T0, T1, and image superposition

| Measurements | Definition | Figure |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Vertical dimension | ||

| N-B (mm) | Distance from the nasion (N) to the supramental (B) | 3 (a) |

| N-Me (mm) | Distance from the nasion (N) to the mentonian (Me) | 3 (a) |

| Condylar rotation | ||

| Fs.CoGo (°) | Angle formed among the fossa point (Fs), condylion (Co), and gonion (Go) | 3 (c) |

| Em.Co0Co1 (°) | Angle formed among the eminence point (Em) and condylion (Co) in T0 and T1 superimposition | 4 (a) |

| EmM.Co0Co1 (°) | Angle formed among the medial eminence point (EmM) and condylion (Co) in T0 and T1 superimposition | |

| EmLCo0Co1 (°) | Angle formed among the lateral eminence point (EmL) to the condylion (Co) in T0 and T1 superimposition | |

| Condylar translation | ||

| Fs-Co (mm) | Distance from the fossa point (Fs) to the condylion (Co) | 4 (b) |

| Co-Em (mm) | Distance from the condylion point (Co) to the eminence point (Em) | 4 (b) |

| Co-EmM (mm) | Distance from the condylion point (Co) to the eminence point (EmM) | |

| Co-EmL (mm) | Distance from the condylion point (Co) to the eminence point (EmL) | |

| Fs.Co0Co1 (°) | Angle formed from the fossa point (Fs) to the condylion point (Co) in the superimposition of T0 and T1 | 4 (a) |

| Co0-Co1 (mm) | Distance between the condylion points (Co) in the superimposition of T0 and T1 | 4 (c) |

| Mandibular advancement | ||

| SNB (°) | Angle formed among sella (S), nasion (N), and supramental (B) | |

| ANB (°) | Angle formed among subspinal (A), nasion (N), and supramental (B) | |

| B0-B1 (mm) | Distance between the supramental points (B) in the superimposition of T0 and T1 | 3 (a) |

| Me0-Me1 (mm) | Distance between the mentonian points (Me) in the superimposition of T0 and T1 | 3 (a) |

| Mandibular rotation | ||

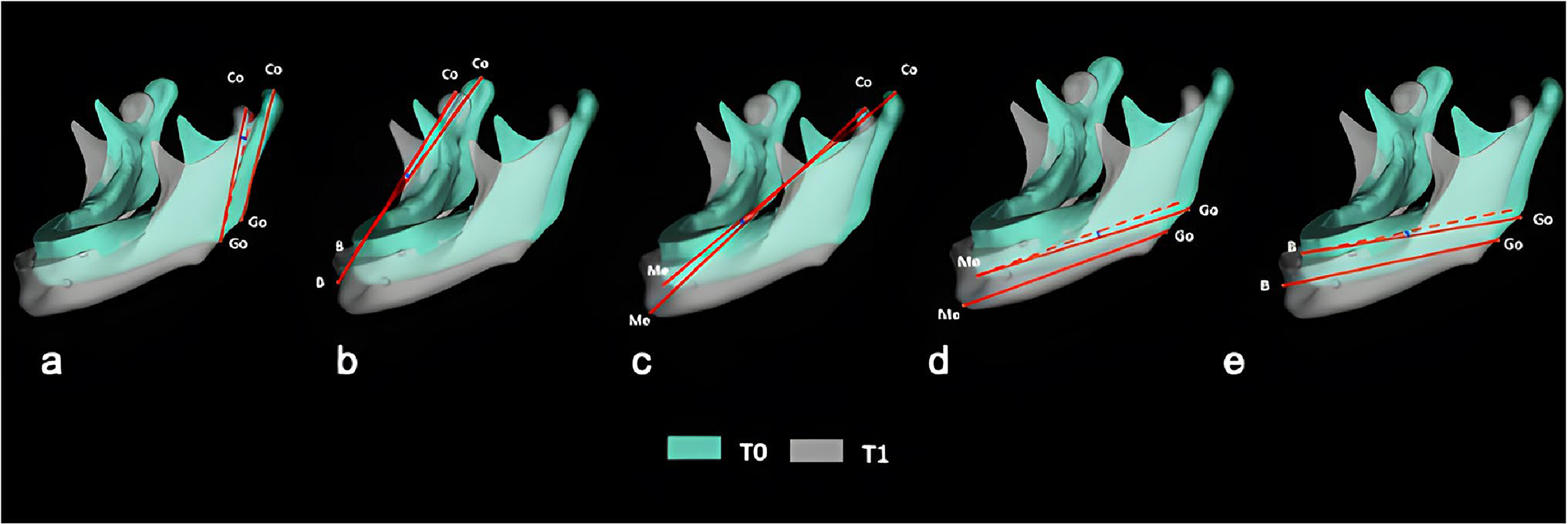

| Co0Go0.Co1Go1 (°) | Angle formed among condylion (Co) and gonion (Go) in T0 and T1 superimposition | 5 (a) |

| Co0B0.Co1B1 (°) | Angle formed among condylion (Co) and supramental (B) in T0 and T1 superimposition | 5 (b) |

| Co0Me0.Co1Me1 (°) | Angle formed among condylion (Co) and mentonian (Me) in T0 and T1 superimposition | 5 (c) |

| Go0Me0.Go1Me1 (°) | Angle formed among gonion (Go) and mentonian (Me) in T0 and T1 superimposition | 5 (d) |

| Go0B0.Go1B1 (°) | Angle formed among gonion (Go) and supramental (B) in TO and T1 superimposition | 5 (e) |

| Mandibular translation | ||

| Fs.Go0Go1 (°) | Angle formed among fossa point (Fs) and gonion (Go) in T0 and T1 superimposition | 3 (b) |

| Go0-Go1 (mm) | Distance between the gonion points (Go) in the superimposition of T0 and T1 | 3 (a) |

| Articular eminence dimension | ||

| Fs-Em (mm) | Distance from the fossa point (Fs) to the eminence point (Em) | 4 (c) |

| Fs-EmM (mm) | Distance from the fossa point (Fs) to the medial eminence point (EmM) | |

| Fs-EmL (mm) | Distance from the fossa point (Fs) to the lateral eminence point (EmL) | |

T0 follow-up before initiating treatment, T1 follow-up after initiating treatment

Fig. 3.

Angular and linear measurements performed on the skull and mandible. a Fs.Go0Go1 angle through image overlay. b Linear distances N-B, N-Me in T0 and T1; B 0-B1, Me0-Me1, and G o0-Go1 through image overlay. c Fs.CoGo angle in T0 and T1 measurements of reference points are described in Supplementary Table 1

Fig. 4.

Angular and linear measurements performed on the TMJ and mandible. a Fs.Co0Co1, Em.Co0Co1, EmMed.Co0Co1, and EmLat. Co0Co1 angles through image overlay; b linear distances Fs-Co, Co-Em, Co-EmMed, and Co-EmLat in T0 and T1; c linear distances Fs-Em, Fs-EmMed, and Fs-EmLat in T0 and C o0Co1 through image overlay. Measurements of reference points are described in Supplementary Table 1

Fig. 5.

Angular mandibular measurements through image overlay. a Co0Go0.Co1Go1, b Co0B0.Co1B1, c Co0Me0.Co1Me1, d Go0Me0.Go1Me1, e Go0B0.Go1B1. Measurements of reference points are described in Supplementary Table 1

The T0 and T1 data were processed using open-source imaging platforms. Two open-source software programs were used for processing the T0 and T1 data following the steps described below:

1. Segmentation—construction of 3D volumetric label maps for T0 scans

The ITK-SNAP 3.8 software (https://www.itksnap.org) was utilized for the segmentation of the cranial base, TMJ, mandible, and airways, essential for image processing. Additionally, it was employed for the conversion of DICOM files to NifTI files [19]. The segmentation involved the use of the active contour method to outline anatomical structures based on the grayscale intensity of the CBCT image and its boundaries. The threshold was adjusted scan by scan, as ITK-SNAP allows for the customization of parameters for the automatic detection of intensities and boundaries. Moreover, it enables users to interactively edit contours [20, 21] (Supplementary Figure 1).

2. Head orientation

Three-dimensional surface models of the T0 segmentations were created and employed for head orientation using the Slicer software. The orientation process involved aligning the models with the Frankfurt horizontal, sagittal, and transporionic planes, which corresponded to the axial, sagittal, and coronal planes, respectively, within a standard coordinate system in the Slicer software. The matrix generated from this systematic orientation procedure was subsequently applied to the T0 scan and 3D volumetric label map (segmentation), ensuring a consistent head orientation [16, 21, 22] (Supplementary Figure 2).

3. Registration

To align the T1 scans with the previously oriented T0 scans, a manual approximation was performed using the transform module in the Slicer software [16, 22]. Sub-sequently, an automatic voxel-based registration method [23] was applied within the Slicer software. This method utilized the segmentation of stable anatomical structures as a mask for the reference region, instructing the software on which areas to search for corresponding voxels to achieve registration. The matrix generated from this step was then applied to the pre-labeled and approximated T1 3D volumetric label maps to achieve the same registration as T0. Following registration, 3D surface models of the mandible for T0 and T1 (.vtk files) were generated for each tested mask. Image registration was employed to assess the 3D spatial differences between T0 and T1, based on their overlapped images [16, 21, 22] (Supplementary Figure 3).

4. Segmentation—construction of 3D volumetric label maps for T1 scans

The segmentation of the registered T1 scans was also performed using ITK-SNAP software, following the same methodology as described for T0 [16, 21] (Supplementary Figure 1).

5. Pre-labeling and placement of landmarks on the T0 and T1 images

Sixteen 3D points were directly defined on the tomographic images using a 3D marker in the ITK-SNAP software as a pre-labeling step (Supplementary Table 1). These pre-labeling landmarks were subsequently utilized as reference points for the placement of landmarks in the 3D surface models within the Slicer software (Supplementary Figure 4) [21, 22, 24].

6. Automated quantification of 3D components (AQ3DC software tool)

Upon establishing the reference points, linear, angular, area, and volumetric measurements of the cranial base, TMJ, mandible, and airway were obtained. These measurements were performed using the AQ3DC tool, which represents the automated version of Q3DC in Slicer software. The units of these measurements were expressed in millimeters (mm) for linear dimensions, degrees (°) for angular measurements, square millimeters (mm2) for area measurements, and cubic millimeters (mm3) for volumetric measurements (Supplementary Figure 5) [22].

Quantification of measurements in the upper airway

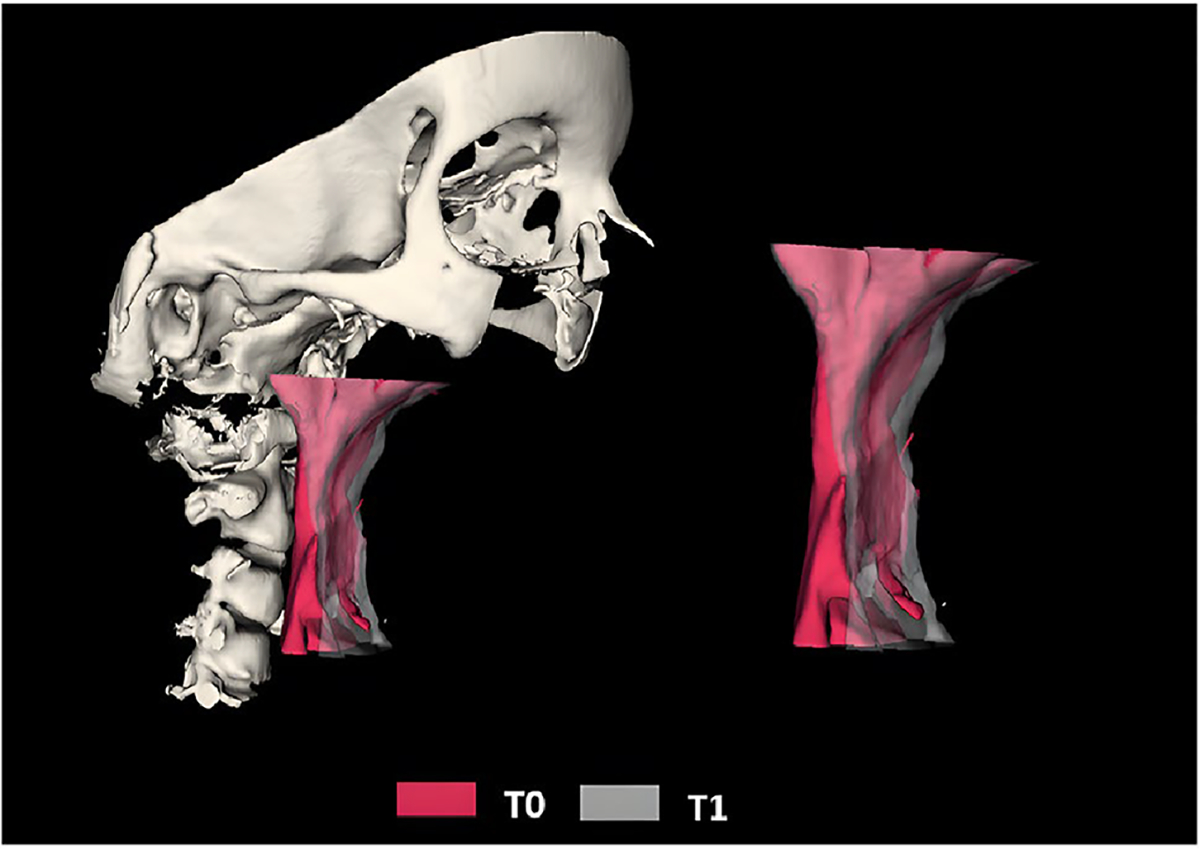

The volume and area of the UA, superior oropharynx, and inferior oropharynx were calculated. The upper boundary of the UA was defined superiorly by the basion (Ba) and posterior nasal spine (PNS) points, while the lower boundary was defined by a tangent line to the most inferior and anterior point of the fourth cervical vertebra (C4), parallel to the Frankfurt plane. The UA was divided into two regions, namely the superior oropharynx and the inferior oropharynx, separated by a tangent line to the most inferior and anterior point of the second cervical vertebra (C2), also parallel to the Frankfurt plane (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Superimposition of the upper airway at T0 and T1. Measurements of reference points are described in Supplementary Table 1

Study error

The tomographic measurements were conducted by a single examiner with a 15-day interval between each assessment, followed by an analysis of intra-operator agreement. The data were exported to Microsoft Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS®) version 20.0 for Windows (IBM Corporation, Sommers, NY). The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) with a 95% confidence interval was employed to evaluate systematic errors concerning the numerical data.

Statistical analysis

The data were stored in Microsoft Excel and exported to the SPSS® version 20.0 software for Windows. Analysis was conducted using a 95% confidence interval. The variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation and assessed for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov normality test. Paired t-tests were used to compare measurements at T0 and T1 (for parametric data), while Pearson’s correlation was employed to evaluate correlations.

Results

Study error

The intra-examiner repeatability of angular, linear, and volumetric measurements demonstrated excellent results in terms of correlation coefficients, with values exceeding 0.9 for the intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs).

Therapeutic protrusion

The average therapeutic protrusion was 94.4 ± 4.6%. This value was determined based on the improvement in signs and symptoms of OSA documented in the medical records, with the treatment time to achieve it varying between 4 and 6 months.

Vertical dimension

The utilization of MAD resulted in a significant increase in the superoinferior distances of N-B (p < 0.001) and N-Me (p < 0.001), indicating that MAD affects the vertical dimension of the patients while in use (Table 3).

Table 3.

3D craniofacial measurements performed at T0 and T1

| Measurements | T0 | T1 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Vertical dimension | |||

| N-B (mm) | |||

| Anteroposterior | −2.27 ± 5.73 | 0.25 ± 5.43 | 0.001 |

| Superoinferior | −94.48 ± 7.86 | −104.69 ± 8.76 | < 0.001 |

| N-Me (mm) | |||

| Anteroposterior | −7.34 ± 6.47 | −5.54 ± 6.17 | 0.015 |

| Superoinferior | −112.68 ± 7.94 | −121.98 ± 8.57 | < 0.001 |

| Mandibular advancement | |||

| SNB (°) | 79.62 ± 4.65 | 81.08 ± 4.01 | 0.004 |

| ANB (°) | 3.67 ± 3.06 | 1.98 ± 3.06 | < 0.001 |

| Condylar rotation | |||

| Fs.CoGo (°) | 165.4734 ± 9.021 | 138.5842 ± 9.752 | < 0.001 |

| Condylar translation | |||

| Fs-Co (mm) | |||

| Anteroposterior | −0.1316 ± 0.805 | 6.7899 ± 2.115 | < 0.001 |

| Superoinferior | −2.9115 ± 0.804 | −7.0327 ± 1.471 | < 0.001 |

| Co-Em (mm) | |||

| Anteroposterior | 8.3142 ± 1.440 | 1.4298 ± 2.270 | < 0.001 |

| Superoinferior | −4.1650 ± 0.955 | 0.0188 ± 1.136 | < 0.001 |

| Co-EmM (mm) | |||

| Anteroposterior | 1.3175 ± 1.458 | −5.9888 ± 2.565 | < 0.001 |

| Superoinferior | −6.4870 ± 1.507 | −2.1043 ± 1.728 | < 0.001 |

| Co-EmL (mm) | |||

| Anteroposterior | 9.3748 ± 1.858 | 2.8267 ± 2.375 | < 0.001 |

| Superoinferior | −5.6791 ± 1.112 | −1.2964 ± 1.355 | < 0.001 |

| Upper airway measurements | |||

| Total volume | 12,155.15 ± 4204.16 | 13,529.62 ± 4899.07 | 0.108 |

| Total area | 5061.85 ± 1154.82 | 5298.92 ± 1170.70 | 0.131 |

| Superior oropharynx volume | 7657.00 ± 2347.81 | 9296.67 ± 3448.11 | 0.005 |

| Superior oropharynx area | 3299.55 ± 714.18 | 3625.28 ± 793.83 | 0.005 |

| Inferior oropharynx volume | 4474.16 ± 2258.51 | 4174.14 ± 2129.35 | 0.485 |

| Inferior oropharynx area | 2088.55 ± 676.64 | 1971.69 ± 633.55 | 0.257 |

| Polysomnographic variables | |||

| AHI | 12.66 ± 9.02 | 6.18 ± 8.65 | < 0.001 |

| SpO2 mean | 95.38 ± 1.03 | 94.99 ± 1.30 | 0.143 |

| SpO2 min | 84.20 ± 4.50 | 87.10 ± 5.30 | 0.002 |

T0 follow-up before initiating treatment, T1 follow-up after initiating treatment, AHI Apnea–Hypopnea Index, SpO2 mean mean oxyhemoglobin saturation, SpO2 min minimum oxyhemoglobin saturation

p < 0.05, paired t-test (mean ± SD)

Condylar and mandibular measurements

A significant change in condylar positioning was observed, as indicated by rotational (p < 0.001) and translational (p < 0.001) movements, with a tendency for forward and downward movement. In terms of mandibular displacement, a significant forward advancement of point B was noted, in line with the increase in SNB angles (p = 0.004) and ANB angles (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

A direct correlation was observed between condylar rotation (Em.Co0Co1) and mandibular translation (Fs. Go0Go1 and Go0Go1 AP), indicating that higher condylar rotation leads to greater anterior mandibular displacement. Additionally, higher condylar rotation (Em.Co0Co1) resulted in larger amounts of mandibular advancement (B0-B1 and Me0Me1) with the use of MAD (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation of condylar rotation and translation with mandibular advancement, translation, and rotation

| Mandibular measurements | Condylar measurements | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Rotation Fs.Co0Co1 | Rotation Em.Co0Co1 | Rotation EmM.Co0Co1 | Rotation EmLCo0Co1 | Translation Δ Fs.CoGo | Translation Δ Fs-Co AP | Translation Δ Fs-Co SI | Translation Δ Co-Em AP | Translation Δ Co-Em SI | Translation Δ Co-EmM AP | Translation Δ Co-EmM SI | Translation Δ Co-EmL AP | Translation Δ Co-EmL SI | Translation Co0Co1 AP | Translation Co0Co1 SI | |

| p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Rotation | |||||||||||||||

| Co0Go0.Co1Go1 | 0.496 (0.162) | 0.998 (0.001) | 0.973 (0.008) | 0.680 (0.098) | 0.135 (0.346) | 0.897 (−0.031) | 0.123 (0.356) | 0.81 (0.057) | 0.077 (−0.404) | 0.988 (0.004) | 0.379 (−0.208) | 0.887 (0.034) | −0.084 (0.396) | 0.993 (0.002) | 0.107 (0.371) |

| Co0B0.Co1B1 | 0.763 (0.072) | 0.560 (−0.139) | 0.967 (0.010) | 0.426 (0.189) | 0.981 (0.006) | 0.84 (−0.048) | 0.582 (0.131) | 0.903 (0.029) | 0.46 (−0.175) | 0.748 (−0.077) | 0.927 (−0.022) | 0.985 (−0.005) | 0.245 (−0.273) | 0.845 (−0.047) | 0.621 (0.118) |

| Translation | |||||||||||||||

| Fs.Go0Go1 | 0.354 (0.219) | 0.000 (0.730)** | 0.596 (0.126) | 0.102 (0.377) | 0.891 (0.033) | <0.001 (0.767)* | 0.193 (−0.304) | 0.001 (−0.672)* | 0.064 (0.422) | 0.003 (−0.626)* | 0.518 (0.154) | 0.006 (−0.596)* | 0.148 (0.336) | 0.00 (0.737)** | 0.231 (−0.281) |

| Go0Go1 AP | 0.479 (0.168) | 0.000 (0.743)** | 0.358 (0.217) | 0.030 (0.486)* | 0.89 (−0.033) | <0.001 (0.842)* | 0.019 (−0.52)* | <0.001 (−0.745)* | 0.003 (0.621)* | <0.001 (−0.762)* | 0.181 (0.312) | <0.001 (−0.703)* | 0.012 (0.551)* | 0.000 (0.840)** | 0.033 (−0.478)* |

| Go0Go1 SI | 0.573 (−0.134) | 0.805 (−0.059) | 0.019 (−0.521)* | 0.716 (−0.087) | 0.301 (0.243) | 0.229 (−0.282) | <0.001 (0.686)* | 0.057 (0.432) | 0.004 (−0.61)* | 0.145 (0.338) | 0.001 (−0.662)* | 0.038 (0.467)* | 0.014 (−0.541)* | 0.211 (−0.292) | <0.001 (0.686)* |

| Advancement | |||||||||||||||

| B0-B1 AP | 0.218 (0.288) | 0.004 (0.618)** | 0.025 (0.499)* | 0.306 (0.241) | 0.929 (0.021) | <0.001 (0.808)* | 0.002 (−0.647)* | <0.001 (−0.758)* | <0.001 (0.721)* | <0.001 (−0.712)* | 0.02 (0.514)* | <0.001 (−0.768)* | 0.002 (0.643)* | 0.000 (0.802)** | 0.002 (−0.653)* |

| B0-B1 SI | 0.636 (−0.113) | 0.992 (−0.002) | 0.040 (−0.463)* | 0.231 (−0.281) | 0.602 (0.124) | 0.387 (−0.205) | 0.046 (0.451)* | 0.414 (0.193) | 0.096 (−0.382) | 0.227 (0.283) | −0.104 (0.374) | 0.238 (0.277) | 0.184 (−0.31) | 0.483 (−0.167) | 0.021 (0.511)* |

| Me0.Me1 AP | 0.174 (0.335) | 0.002 (0.686)** | 0.049 (0.470)* | 0.016 (0.560)* | 0.989 (0.003) | <0.001 (0.825)* | 0.006 (−0.589)* | <0.001 (−0.74)* | <0.001 (0.685)* | 0.007 (−0.584)* | 0.122 (0.357) | <0.001 (−0.727)* | 0.006 (0.59)* | 0.000 (0.834)** | 0.007 (−0.584)* |

| Me0.Me1 SI | 0.093 (−0.020) | 0.601 (−0.125) | 0.018 (−0.523)* | 0.230 (−0.281) | 0.294 (0.247) | 0.22 (−0.287) | 0.003 (0.636)* | 0.185 (0.309) | 0.012 (−0.548)* | 0.041 (0.461)* | 0.007 (−0.581)* | 0.096 (0.383) | 0.011 (−0.555)* | 0.196 (−0.302) | 0.001 (0.667)* |

| Vertical dimension | |||||||||||||||

| ΔN-B SI | 0.677 (−0.099) | 0.918 (0.025) | 0.046 (−0.452)* | 0.19 (−0.306) | 0.999 (0) | 0.327 (−0.231) | 0.052 (0.441) | 0.35 (0.221) | 0.123 (−0.357) | 0.184 (0.31) | 0.142 (−0.34) | 0.178 (0.314) | 0.226 (−0.283) | 0.417 (−0.192) | 0.031 (0.483)* |

| ΔN-Me SI | 0.998 (0) | 0.718 (−0.086) | 0.026 (−0.496)* | 0.187 (−0.308) | 0.757 (0.074) | 0.173 (−0.317) | 0.004 (0.609)* | 0.142 (0.34) | 0.024 (−0.502)* | 0.029 (0.489)* | 0.018 (−0.525)* | 0.061 (0.426) | 0.022 (−0.509)* | 0.154 (−0.331) | 0.004 (0.616)* |

AP anteroposterior, SI superoinferior, Δ variation

p < 0.05, Pearson’s correlation

Anterior condylar translation (ΔFs-Co AP, ΔCo-Em AP, and Co0Co1 AP) also showed a direct correlation with mandibular translation and advancement. Increased anterior movement of the condyles was associated with higher values of mandibular translation and advancement. Conversely, inferior translation measures (ΔFs-Co SI, ΔCo-Em SI, and Co0Co1 SI) were mostly correlated with lower values of anterior translation and mandibular advancement. The inferior translation measures (ΔFs-Co SI, ΔCo-Em SI, and Co0Co1 SI) were primarily associated with an increase in the vertical dimension with the use of MAD (Table 4).

Articular eminence dimension

In terms of the articular eminence measurements, it was observed that a larger central length of the articular eminence (Fs-Em AP) was associated with smaller amounts of condylar rotation (Em.Co0Co1) (p = 0.034, r = − 0.476). The medial length displayed an inverse correlation with condylar translation values (Fs.Co0Co1) (p = 0.038, r = − 0.466). Conversely, the lateral length of the articular eminence demonstrated a direct correlation with three measurements of condylar translation (Fs.Co0Co1, ΔCo-Em SI, ΔCo-EmM SI), while exhibiting an inverse correlation in only one measurement (ΔCo-EmL AP). In general, a longer lateral length of the articular eminence was associated with greater condylar translation, particularly in terms of the inferior displacement of the condyles.

The height in the lateral portion (Fs-EmL SI) of the articular eminence exhibited correlations with condylar rotation and translation. A higher height in the lateral region was associated with larger amounts of condylar rotation (ΔFs. CoGo) (p = 0.025, r = 0.5) and translation (Fs.Co0Co1) (p = 0.426, r = 0.188) with the use of MAD.

Both the height and length of the articular eminence did not demonstrate correlations with mandibular measurements, including rotation, translation, advancement, as well as the vertical dimension with the use of MAD (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation of eminence dimensions with condylar and mandibular rotation, translation, as well as vertical measurements

| Condylar and mandibular measurements | Eminence dimensions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Length Fs-Em AP | Height Fs-EmSI | Length Fs-EmM AP | Height Fs-EmM SI | Length Fs-EmL AP | Height Fs-EmL SI | |

| p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | |

|

| ||||||

| Condylar rotation | ||||||

| ΔFs.CoGo | 0.751 (−0.076) | 0.939 (0.018) | 0.649 (−0.109) | 0.089 (0.39) | 0.542 (−0.145) | 0.025 (0.5)* |

| Em.Co0Co1 | 0.034 (−0.476)* | 0.550 (0.142) | 0.780 (−0.067) | 0.366 (0.214) | 0.646 (0.109) | 0.488 (0.165) |

| EmMed.Co0Co1 | 0.347 (−0.222) | 0.571 (−0.135) | 0.384 (−0.206) | 0.817 (−0.055) | 0.283 (0.252) | 0.824 (0.053) |

| EmLat.Co0Co1 | 0.976 (0.007) | 0.953 (−0.014) | 0.485 (0.166) | 0.808 (0.058) | 0.094 (−0.384) | 0.741 (0.079) |

| Condylar translation | ||||||

| Fs.Co0Co1 | 0.603 (0.124) | 0.656 (−0.106) | 0.038 (−0.466)* | 0.521 (0.152) | 0.034 (0.476)* | 0.426 (0.188)* |

| ΔFs-Co AP | 0.467 (−0.173) | 0.819 (−0.055) | 0.397 (−0.2) | 0.396 (0.201) | 0.098 (0.381) | 0.495 (0.162) |

| ΔFs-Co SI | 0.617 (−0.119) | 0.767 (0.071) | 0.705 (0.09) | 0.923 (−0.023) | 0.125 (−0.355) | 0.637 (0.112) |

| ΔCo-Em AP | 0.992 (0.002) | 0.882 (−0.035) | 0.133 (0.348) | 0.808 (−0.058) | 0.078 (−0.403) | 0.447 (−0.18) |

| ΔCo-Em SI | 0.598 (0.125) | 0.49 (−0.164) | 0.622 (−0.118) | 0.995 (0.002) | 0.025 (0.5)* | 0.445 (−0.181) |

| ΔCo-EmM AP | 0.667 (0.102) | 0.201 (0.201) | 0.802 (−0.06) | 0.89 (0.033) | 0.416 (−0.192) | 0.587 (−0.129) |

| ΔCo-EmM SI | 0.131 (0.35) | 0.322 (−0.233) | 0.134 (−0.347) | 0.219 (−0.287) | 0.003 (0.621)* | 0.19 (−0.306) |

| ΔCo-EmL AP | 0.817 (0.055) | 0.98 (0.006) | 0.199 (0.3) | 0.381 (−0.207) | 0.019 (−0.52)* | 0.527 (−0.15) |

| ΔCo-EmL SI | 0.537 (0.147) | 0.363 (−0.215) | 0.892 (−0.032) | 0.568 (−0.136) | 0.143 (0.339) | 0.284 (−0.252) |

| Co0Co1 AP | 0.632 (−0.114) | 0.779 (−0.067) | 0.374 (−0.210) | 0.491 (0.164) | 0.059 (0.429) | 0.581 (0.131) |

| Co0Co1 SI | 0.852 (−0.044) | 0.539 (0.539) | 0.778 (0.067) | 0.924 (−0.023) | 0.073 (−0.410) | 0.638 (0.112) |

| Mandibular rotation | ||||||

| Co0Go0.Co1Go1 | 0.862 (−0.042) | 0.619 (−0.118) | 0.387 (−0.205) | 0.335 (0.227) | 0.926 (−0.022) | 0.334 (0.228) |

| Co0B0.Co1B1 | 0.0233 (0.279) | 0.940 (−0.018) | 0.864 (0.041) | 0.493 (−0.163) | 0.612 (−0.121) | 0.817 (0.055) |

| Co0Me0.Co1Me1 | 0.117 (0.362) | 0.967 (−0.010) | 0.624 (0.117) | 0.387 (−0.205) | 0.956 (0.013) | 0.782 (0.066) |

| Go0Me0.Go1Me1 | 0.600 (0.125) | −0.275 (0.256) | 0.094 (0.385) | 0.613 (−0.121) | 0.739 (0.080) | 0.558 (−0.139) |

| Go0B0.Go1B1 | 0.867 (0.040) | 0.428 (−0.188) | 0.311(0.239) | 0.941 (−0.018) | 0.636 (−0.113) | 0.712 (−0.088) |

| Mandibular translation | ||||||

| Fs.Go0Go1 | −0.202 (0.298) | 0.658 (0.105) | 0.963 (−0.011) | 0.856 (0.043) | 0.479 (0.168) | 0.470 (0.171) |

| Go0Go1 AP | 0.346 (−0.222) | 0.990 (0.003) | 0.846 (0.046) | 0.880 (0.036) | 0.300 (0.244) | 0.741 (0.079) |

| Go0Go1 SI | 0.134 (−0.347) | 0.634 (−0.114) | 0.465 (0.173) | 0.388 (0.204) | 0.167 (−0.322) | 0.736 (−0.080) |

| Mandibular advancement | ||||||

| B0-B1 AP | 0.270 (−0.259) | 0.633 (−0.114) | 0.568 (−0.136) | 0.696 (0.093) | 0.067 (0.417) | 0.489 (0.164) |

| B0-B1 SI | 0.449 (−0.180) | 0.668 (0.102) | 0.599 (−0.125) | 0.463 (0.174) | 0.713 (−0.088) | 0.744 (0.078) |

| Me0.Me1 AP | 0.157 (−0.348) | 0.697 (−0.098) | 0.506 (−0.168) | 0.379 (0.221) | 0.204 (0.315) | 0.892 (0.035) |

| Me0.Me1 SI | 0.309 (−0.240) | 0.425 (−0.189) | 0.459 (−0.176) | 0.265 (0.262) | 0.198 (−0.300) | 0.492 (0.163) |

| Vertical dimension | ||||||

| Δ N-B SI | 0.427 (−0.188) | 0.721 (0.085) | 0.698 (−0.093) | 0.622 (0.117) | 0.727 (−0.083) | 0.791 (−0.063) |

| Δ N-Me SI | 0.294 (−0.247) | 0.493 (0.163) | 0.593 (−0.127) | 0.449 (0.18) | 0.214 (−0.29) | 0.896 (−0.031) |

AP anteroposterior, SI superoinferior, Δ variation

p < 0.05, Pearson correlation

Upper airway and polysomnographic values

Out of the 20 patients evaluated, 17 were categorized as responders (AHI < 10), and among them, 14 demonstrated successful treatment with an AHI < 5. However, all patients exhibited a significant reduction in AHI (p < 0.001) (Table 3). Three patients did not achieve an AHI < 10 or a 50% reduction in AHI, and as a result, they were classified as non-responders. The mean S pO2 did not show a significant improvement with treatment (p = 0.181), while the minimum SpO2 demonstrated a significant increase with the use of MAD (p < 0.001). Additionally, there was a significant increase in both the volume and area of the superior oropharynx (p = 0.005) (Table 3). The mean S pO2 did not show a significant improvement with treatment (p = 0.181), while the minimum S pO2 demonstrated a significant increase with the use of MAD (p < 0.001). Additionally, there was a significant increase in both the volume and area of the superior oropharynx (p = 0.005) (Table 3).

Condylar rotation demonstrated a direct correlation with the increase in total UA volume and the volume of the superior oropharynx. Additionally, condylar translation generally displayed a direct correlation with the increase in UA volume, encompassing both the total volume and the volumes of the superior and inferior oropharynx. However, there was no statistically significant correlation observed between condylar rotation and translation with AHI, mean S pO2, and minimum SpO2 (Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlation of upper airway volume and polysomnographic values with condylar and mandibular rotation and translation

| Condylar and mandibular measurements | Polysomnographie variables and UA volume | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| ΔAHI | ΔSpO2 mean | ΔSpO2 min | Δtotal UA vol | ΔSO vol | ΔIO vol | |

| p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | |

|

| ||||||

| Condylar rotation | ||||||

| ΔFs.CoGo | 0.528 (−0.15) | 0.897 (−0.031) | 0.802 (0.06) | 0.569 (0.135) | 0.578 (0.132) | 0.675 (0.1) |

| Em.Co0Co1 | 0.953 (0.014) | 0.562 (−0.138) | 0.77 (−0.07) | 0.111 (0.367) | 0.44 (0.052) | 0.495 (0.162) |

| EmM.Co0Co1 | 0.392 (0.203) | 0.553 (−0.141) | 0.981 (0.006) | 0.165 (0.323) | 0.504 (0.159) | 0.068 (0.416) |

| EmL.Co0Co1 | 0.52 (−0.153) | 0.558 (−0.139) | 0.626 (0.116) | 0.011 (0.555)* | < 0.001 (0.711)* | 0.51 (0.157) |

| Condylar translation | ||||||

| Fs.Co0Co1 | 0.236 (−0.278) | 0.539 (0.146) | 0.165 (0.323) | 0.123 (0.356) | 0.4789 (0.168) | 0.029 (0.487) |

| ΔFs-Co AP | 0.203 (−0.297) | 0.944 (−0.017) | 0.378 (0.208) | < 0.001 (0.766)* | < 0.001 (0.714)* | 0.005 (0.599)* |

| ΔFs-Co SI | 0.338 (0.226) | 0.652 (0.108) | 0.373 (−0.211) | < 0.001(−0.744)* | < 0.001 (−0.68)* | 0.005 (−0.601)* |

| ΔCo-Em AP | 0.516 (0.154) | 0.773 (0.069) | 0.158 (−0.328) | < 0.001(−0.717)* | 0.005 (−0.606) | 0.003 (−0.637)* |

| ΔCo-Em SI | 0.176 (−0.315) | 0.849 (−0.045) | 0.375 (0.21) | < 0.001 (0.77)* | < 0.001 (0.681)* | 0.001 (0.661)* |

| ΔCo-EmM AP | 0.21 (0.293) | 0.345 (0.223) | 0.269 (−0.259) | < 0.001 (−0.72)* | < 0.001(−0.759)* | 0.048 (−0.448)* |

| ΔCo-EmM SI | 0.97 (0.009) | 0.406 (−0.197) | 0.354 (0.219) | 0.036 (0.47)* | 0.075 (0.406) | 0.063 (0.424) |

| ΔCo-EmLAP | 0.208 (0.294) | 0.819 (0.055) | 0.27 (−0.259) | < 0.001(−0.756)* | 0.002 (−0.651)* | 0.002 (−0.658)* |

| ΔCo-EmL SI | 0.42 (−0.191) | 0.855 (−0.044) | 0.374 (0.21) | 0.001 (0.671)* | 0.001 (0.644)* | 0.03 (0.487)* |

| Co0Co1 AP | 0.191 (−0.305) | 0.871 (−0.039) | 0.349 (0.221) | < 0.001 (0.746)* | < 0.001 (0.698)* | 0.008 (0.577)* |

| Co0Co1 SI | 0.264 (0.262) | 0.665 (0.103) | 0.487 (−0.165) | 0.003 (−0.621)* | 0.003 (−0.623)* | 0.007 (−0.587)* |

| Mandibular rotation | ||||||

| Co0Go0.Co1Go1 | 0.97 (0.009) | 0.975 (−0.008) | 0.434 (−0.185) | 0.239 (−0.276) | 0.317 (−0.236) | 0.222 (−0.286) |

| Co0B0.Co1B1 | 0.913 (−0.026) | 0.769 (−0.07) | 0.549 (−0.143) | 0.504 (−0.159) | 0.454 (−0.174) | 0.501 (−0.131) |

| Co0Me0.Co1Me1 | 0.62 (−0.118) | 0.826 (−0.052) | 0.654 (−0.107) | 0.206 (−0.296) | 0.319 (−0.235) | 0.169 (−0.32) |

| Go0Me0.Go1Me1 | 0.245 (−0.273) | 0.987 (−0.004) | 0.188 (−0.307) | 0.43 (−0.187) | 0.954 (−0.011) | 0.095 (−0.383) |

| Go0B0.Go1B1 | 0.547 (−0.126) | 0.925 (−0.023) | 0.195 (−0.302) | 0.895 (−0.031) | 0.923 (0.023) | 0.601 (−0.124) |

| Mandibuular translation | ||||||

| Fs.Go0Go1 | 0.397 (−0.2) | 0.964 (−0.011) | 0.28 (0.254) | 0.008 (0.573)* | 0.006 (0.593)* | 0.086 (0.393) |

| Go0Go1 AP | 0.171 (−0.319) | 0.925 (0.023) | 0.275 (0.257) | < 0.001 (0.691)* | < 0.001 (0.706)* | 0.033 (0.479)* |

| Go0Go1 SI | 0.575 (0.133) | 0.695 (0.093) | 0.221 (−0.286) | 0.077 (−0.404) | 0.397 (−0.2) | 0.015 (−0.537)* |

| Mandibular advancement | ||||||

| B0-B1 AP | 0.275 (−0.256) | 0.654 (−0.107) | 0.263 (0.263) | < 0.001 (0.705)* | 0.003 (0.623)* | 0.004 (0.62)* |

| B0-B1 SI | 0.62 (0.118) | 0.863 (0.041) | 0.834 (0.05) | 0.36 (−0.216) | 0.561 (−0.138) | 0.346 (−0.222) |

| Me0.Me1 AP | 0.425 (−0.189) | 0.873 (0.038) | 0.537 (0.147) | < 0.001 (0.707)* | 0.004 (0.612)* | 0.003 (0.629)* |

| Me0.Me1 SI | 0.306 (0.241) | 0.976 (−0.007) | 0.977 (0.007) | 0.333 (−0.228) | 0.442 (−0.182) | 0.412 (−0.194) |

AP anteroposterior, SI superoinferior, Δ variation, SO superior oropharynx, IO inferior oropharynx

p < 0.05, Pearson correlation

By examining the mandibular movements during the use of MAD, it was observed that higher values of anterior mandibular translation (Fs.Go0Go1, Go0Go1 AP) were associated with a greater increase in total UA volume and the volume of the superior oropharynx. Conversely, vertical mandibular translation (Go0Go1 SI) was correlated with a decrease in volume specifically in the inferior oropharynx. Additionally, a greater anterior mandibular displacement (B0-B1 AP, and Me0.Me1 AP) was associated with larger volumes in the UA, superior oropharynx, and inferior oropharynx (Table 6).

When examining the correlation between UA dimensions and polysomnographic changes, positive correlations were observed between improvements in the minimum S pO2 values and various UA parameters, including UA total volume, UA total area, as well as the volumes and areas of the superior and inferior oropharynx (Table 7).

Table 7.

Correlation of upper airway volume and area with polysomnographic values

| Polysomnographic variables | Upper airway variables | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| ΔTotal UA vol | ΔTotal UA area | ΔSO vol | ΔSO area | ΔIO vol | ΔIO area | |

| p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | p-value (r-value) | |

|

| ||||||

| ΔAHI | 0.128 (−0.352) | 0.254 (−0.268) | 0.137 (−0.344) | 0.356 (−0.218) | 0.260 (−0.265) | 0.239 (−0.276) |

| ΔSpO2 mean | 0.908 (−0.028) | 0.800 (0.060) | 0.735 (−0.081) | 0.538 (−0.146) | 0.829 (0.051) | 0.283 (0.252) |

| ΔSpO2 min | 0.007 (0.586)** | 0.004 (0.611)* | 0.031 (0.483)* | 0.005 (0.601)** | 0.012 (0.551)* | 0.018 (0.523)* |

Δ variation, SO superior oropharynx, IO inferior oropharynx

p < 0.05, Pearson’s correlation

Discussion

This study utilized three-dimensional imaging to evaluate the anatomical structures of the mandible, TMJ, and airways, as well as the correlation of TMJ, mandibular, and condylar movements with UA and polysomnographic parameters during the use of MAD for OSA treatment. The findings revealed that the MAD led to an increase in UA volume by advancing the mandible, which may be associated with positional changes, rotation, and/or translation of the condyles within the temporomandibular joint [25]. Consequently, the temporomandibular complex, encompassing the condyles, articular eminence, and fossa, plays a crucial role in determining the position and displacement of the mandible, as well as the extent of mandibular advancement, UA volume augmentation, and treatment efficacy of MAD. Gaining insight into these factors is vital for tailoring OSA treatment with MAD to individual patients. However, studies investigating the correlation of MADs with condylar movements (rotation and translation), patterns of mandibular displacement, TMJ anatomical structures, and UA volume using CBCT imaging are limited in the existing literature.

Treatment with MAD resulted in an increase in the vertical dimension, as indicated by the measurements of N-B and N-Me, as well as mandibular advancement observed through measurements of SNB and ANB, indicating anterior displacement of the mandible associated with mandibular downward displacement. Although MAD promotes anterior movement of the mandible, the amount of vertical mandibular displacement outweighs the advancement [16, 26, 27]. These vertical changes may be attributed to the thickness of the acrylic material covering the occlusal surfaces [26], leading to a posterior positioning of the mandible [26, 27].

Appliances with greater vertical dimensions have been observed to potentially compromise the inferior oropharynx due to downward and backward displacement of the mandible. In this study, it was found that the MAD led to an increase in vertical dimension with significant changes in condylar position and mandibular displacement. This finding emphasizes the need to consider individualized MAD fabrication with smaller vertical dimensions.

In addition to the vertical changes, a change in condylar position was observed after MAD treatment, assessed through condylar translation and rotation. Previous studies [28] that analyzed sagittal mandibular movements and their relation to the mandibular condyle found that sagittal mandibular movements converge at the condyle. This means that mandibular advancement and condylar movements, represented by rotation and translation, are directly related.

Although rotation and translation movements are inherent to mandibular advancement promoted by this device, we observed a significant direct correlation between condylar rotation and mandibular translation and advancement, as well as an inverse correlation with vertical dimension. Conversely, condylar translation showed a significant direct correlation with advancement and vertical dimension, but an inverse correlation with mandibular translation. These findings can be justified by the fact that MAD promotes mandibular protrusion, resulting in the condyle moving downward and forward in relation to the articular fossa [29]. Consequently, the mandible experiences rotation and posterior displacement [30], leading to an increase in vertical dimension [26].

The influence of the articular eminence on condylar and mandibular movements was analyzed. An inverse correlation was observed between the central length of the eminence and condylar rotation, as well as between the medial length of the eminence and condylar translation. Conversely, the lateral length and height showed a direct correlation with condylar rotation and translation. In their evaluation of condylar movements, Bruno et al. [27] observed that during translation, the condyle moves forward, surpassing the eminence [29]. This finding demonstrates that the dimensions of the eminence can influence condylar rotation and translation, resulting in a change in condylar positioning with a tendency for forward and downward displacement. These changes impact mandibular movements, leading to a counterclockwise mandibular movement. Additionally, the anteroinferior displacement of the condyle allowed for an increase in UA volume.

The MAD treatment resulted in a significant reduction in AHI (p < 0.001), with 85% of the sample classified as responders. Consistent with other studies [16, 31, 32], these results underscore the effectiveness of MADs in reducing AHI, particularly in cases of mild to moderate OSA [5]. Additionally, a significant increase in minimum S pO2 was observed, while mean SpO2 did not show significant changes. Similar findings were reported in previous studies [5, 16, 32, 33]. After MAD therapy, a significant increase in the volume and area of the superior oropharynx was observed. Gurgel et al. [16], Pahkala et al. [31], and Marco-Pitarch et al. [32] also reported an increase in oropharyngeal volume after MAD therapy. This increase is attributed to the anterior positioning of the mandible, which widens the upper airways, particularly in the regions that define the anatomical boundaries of the oropharynx, such as the soft palate, tongue, and the lateral pharyngeal walls located behind the tongue [32]. However, similar effects were not observed in the total volume and area, or the volume and area of the inferior oropharynx. These findings are consistent with those described in the literature [16] and are associated with the clockwise mandibular rotation resulting from the mandibular advancement device, which prevents an increase in the volume of the inferior oropharynx [16, 26]. The present study demonstrated that a greater increase in total airway dimensions, as well as superior and inferior oropharynx dimensions, was associated with a larger improvement in minimum oxygen saturation. However, no correlation between UA dimensions and AHI was identified, possibly due to a relatively small average variation in UA volume of only 1374.47 mm3. Similar findings were reported by Camañes-Gonzalvo et al. [34]. The authors reported a positive correlation between upper airway volume and minimum oxygen saturation, while average upper airway volume changes of 5000 mm3 were found to be correlated with the AHI. The lack of correlation between AHI and UA volumetric dimensions also represents an important finding. It indicates that the multifactorial complexity of OSA, individual anatomical variability, oropharyngeal muscle dynamics during sleep, and different severity stages of OSA are crucial factors to be explored in future studies. In addition, the correlation between condylar rotation and translation movements with polysomnographic and airway findings was evaluated, revealing a significant correlation between condylar rotation and translation and changes in total volume, as well as the volume of the superior and inferior oropharynx. However, no significant correlation between condylar movements and polysomnographic values was identified.

Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred option for evaluating soft tissues of the pharynx, it is costly. CBCT has been shown to be a precise and comparable technique to MRI [32] and is used to identify craniofacial characteristics that may influence the outcomes of mandibular advancement therapy for OSA [35]. Therefore, tomographic images were used to evaluate craniofacial anatomical structures and airways in the present study.

In this study, CBCT acquisitions were conducted with patients in an upright position. Gurgel et al. [35] highlighted the significance of body position during CBCT acquisition, reporting the influence of position, posture, and gravity on UA dimensions. The authors found no difference in UA volume evaluations between healthy and OSA patients in the supine position, but in the upright position, UA dimensions were significantly reduced in the OSA group. These results suggest that patient positioning during CBCT acquisition may introduce more bias in case–control studies than in cohort studies, owing to differences in muscle responses to gravity when comparing healthy and OSA individuals [35]. To address potential limitations and biases related to the upright position, we meticulously standardized the initial and final tomographic image acquisitions in the present study. Additionally, we emphasize the challenge of establishing parallels with previous findings, as similar investigations assessing the correlation between 3D images, the severity of OSA, and MAD therapy are still scarce. The absence of a control group may represent another limitation. However, from an ethical standpoint, it is not justifiable to subject patients in this group to MAD treatment and two computed tomography exams without a specific indication. The present study importantly elucidates that the anatomic characteristics of the articular eminence may influence condylar and mandibular movements, as well as mandibular advancement, which are correlated with UA volume. These findings highlight that the anatomy and movement of the TMJ complex, in conjunction with MAD therapy, may directly and indirectly influence UA patency. Consequently, these factors should be considered and clinically evaluated during the planning and decision-making process for OSA treatment with MAD. The outcomes of this study demonstrated that individual anatomical characteristics may have an impact on UA improvement during MAD treatment. Therefore, the clinical evaluation of specific anatomical particularities is essential to individualize the treatment of OSA and enhance the success of MAD use.

Conclusion

The articular eminence influenced condylar rotation and translation, while the rotational and translational movements of the condyle, as well as mandibular translation and advancement, affected the upper airway volume, but did not have an impact on PSG parameters. The anatomy of the TMJ complex plays a significant role in the UA during MAD therapy, emphasizing the importance of individualized anatomical evaluation of patients prior to selecting OSA treatment options.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brasil (CAPES)—Funding Code 001.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo, Brazil (number 0301/10). All volunteers were provided with a written Informed Consent Form (IFC), which they were required to sign in order to participate in the study.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-024-05513-9.

References

- 1.Medicine AAoS (1999) Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definitions and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep 22:667–689 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gulotta GIG, Vicini C, Polimeni A, Greco A, de Vincentiis M, Visconti IC, Meccariello G, Cammaroto G, De Vito A, Gobbi R, Bellini C, Firinu E, Pace A, Colizza A, Pelucchi S, Magliulo G (2019) Risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children: state of the art. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16:01–20. 10.3390/ijerph16183235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi N (2020) Diagnosis and management of obstructive sleep apnea: a review. JAMA 323:1389–1400. 10.1001/jama.2020.3514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fabbro CD, Chaves CM Jr, Bittencourt LRA, Tufik S (2010) Clinical and polysonographic assessment of the BRD Appliance in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Dental Press J Orthod 15:107–117 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramar KDL, Katz SG, Lettieri CJ, Harrod CG, Thomas SM, Chervin RD (2015) Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and snoring with oral appliance therapy: an update for 2015. J Clin Sleep Med 11:773–827. 10.5664/jcsm.4858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruwier APR, Albert A, Maes N, Limme M, Charavet C, Milicevic M, Raskin S, Poirrier A (2016) Three-dimensional analysis of craniofacial bones and soft tissues in obstructive sleep apnea using cone beam computed tomography. Int Orthod 14:449–461. 10.1016/j.ortho.2016.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheikhi MMF, Ahmadi A (2012) Assessing the anatomical variations of lingual foramen and its bony canals with CBCT taken from 102 patients in Isfahan. Dent Res J suppl 1:s.45–51 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doff MHJHA, Pruim GJ, Huddleston Slater JJR, Stegenga B (2010) Long-term oral- appliance therapy in obstructive sleep apnea: a cephalometric study of craniofacial changes. J Dent 38:1010–1018. 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim YJHJ, Hwang YI, Park YH (2010) Three-dimensional analysis of pharyngeal airway in preadolescent children with different anteroposterior skeletal patterns. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 137:306.e1–307. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2009.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lucena LBKM, da Costa LJ, de Góes PS (2006) Validation of the Portuguese version of the RDC/TMD Axis II questionnaire. Braz Oral Res 20:312–317. 10.1590/s1806-83242006000400006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cossellu GBR, Sarcina M, Mortellaro C, Farronato G (2015) Three-dimensional evaluation of upper airway in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome during oral appliance therapy. J Craniofac Surg 26:745–748. 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knappe SWSL (2018) Mandibular positioning techniques to improve sleep quality in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: current perspectives. Nat Sci Sleep 10:65–72. 10.2147/NSS.S135760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camañes-Gonzalvo S, Bellot-Arcís C, Marco-Pitarch R, Montiel-Company JM, García-Selva M, Agustín-Panadero R, Paredes-Gallardo VP-CF (2022) Comparison of the phenotypic characteristics between responders and non-responders to obstructive sleep apnea treatment using mandibular advancement devices in adult patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 64:101644. 10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scarfe WC, Farman AG, Sukovic P (2006) Clinical applications of cone-beam computed tomography in dental practice. J Can Dent Assoc 72:75–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moshiri M, Scarfe WC, Hilgers ML, Scheetz JP, Silveira AM, Farman AG (2007) Accuracy of linear measurements from imaging plate and lateral cephalometric images derived from cone-beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 132:550–560. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.09.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurgel MCL, Pereira R, Costa F, Ruellas A, Bianchi J, Cunali P, Bittencourt L, Junior CC (2022) Three-dimensional craniofacial characteristics associated with obstructive sleep apnea severity and treatment outcomes. Clin Oral Investig 26:875–887. 10.1007/s00784021-04066-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tso HHLJ, Huang JC, Maki K, Hatcher D, Miller AJ (2009) Evaluation of the human airway using cone-beam computerized tomography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 108:768–776. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El H, Palomo JM (2010) Measuring the airway in 3 dimensions: a reliability and accuracy study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 137:S50 e1–9. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.1.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yushkevich PA, Gerig G (2017) ITK-SNAP: an intractive medical image segmentation tool to meet the need for expert-guided segmentation of complex medical images. IEEE Pulse 8:54–57. 10.1109/MPUL.2017.2701493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cevidanes LH, Ruellas AC, Jomier J, Nguyen T, Pieper S, Budin F, Styner M, Paniagua B (2015) Incorporating 3-dimensional models in online articles. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 147:S195–204. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruellas AC, Yatabe MS, Souki BQ, Benavides E, Nguyen T, Luiz RR, Franchi L, Cevidanes LH (2016) 3D mandibular superimposition: comparison of regions of reference for voxel-based registration. PLoS ONE 11:e0157625. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruellas ACDOTC, Gomes LR, Yatabe MS, MacRon L, Lopinto J, Goncalves JR, GaribCarreira DG, Alonso N, Souki BQ, Coqueiro RDS, Cevidanes LHS (2016) Common 3- dimensional coordinate system for assessment of directional changes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 149:645–656. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cevidanes LH, Bailey LJ, Tucker GR Jr, Styner MA, Mol A, Phillips CL, Proffit WR, Turvey T (2005) Superimposition of 3D cone-beam CT models of orthognathic surgery patients. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 34:369–375. 10.1259/dmfr/17102411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MoB IM, Rios H, Cevidanes L, Aristizabal JF, Rey D, Kim-Berman H, Yatabe M, Benavides E, Alvarez MA, Volk S, Ruellas AC (2019) Accuracy and reliability of mandibular digital model registration with use of the mucogingival junction as the reference. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 127:351–360. 10.1016/j.oooo.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mah J, Hatcher D (2004) Three-dimensional craniofacial imaging. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 126:308–309. 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LrM MP, Míguez-Contreras M, Garcia M (2019) Antero-posterior mandibular position at different vertical levels for mandibular advancing device design. BMC Oral Health 19:85. 10.1186/s12903-019-0783-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruno GDSA, Conte E, Caragiuli M, Mandolini M, Landi D, Gracco A (2020) A procedure for analyzing mandible roto-translation induced by mandibular advancement devices. Materials 13:1826. 10.3390/ma13081826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shigemoto SBN, NishigawaK SY, Tajima T, Okura K, Matsuka Y (2014) Effect of an exclusion range of jaw movement data from the intercuspal position on the estimation of the kinematic axis point. Med Eng Phys 36:1162–1167. 10.1016/j.medengphy.2014.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heidsieck DSPKJ, de Ruiter MHT, Hoekema A, de Lange J (2018) Biomechanical effects of a mandibular advancement device on the temporomandibular joint. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 46:288–292. 10.1016/j.jcms.2017.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muto TKM, Kanazawa M, Kawakami J (1994) The position of the mandibular condyle at maximal mouth opening in normal subjects. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 52:1269–1272. 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90049-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pahkala RSJ, Myllykangas R, Tervaniemi J, Vartiainen VM, Suominen AL, Muraja-Murro A (2020) The impact of oral appliance therapy with moderate mandibular advancement on obstructive sleep apnea and upper airway volume. Sleep Breath 24:865–873. 10.1007/s11325-019-01914-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ga-SM M-P, Plaza-Espín A, Puertas-Cuesta J, Agustín-Panadero R, Fernández-Julián E, Marco-Algarra J, Fons-Font A (2021) Dimensional analysis of the upper airway in obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome patients treated with mandibular advancement device: a bi- and three-dimensional evaluation. J Oral Rehabil 48:927–936. 10.1111/joor.13176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Gaver H, OdBS DM, De Backer J, Verbraecken J, De Backer WA, Van de Heyning PH, Braem MJ, Vanderveken OM (2022) Functional imaging improves patient selection for mandibular advancement device treatment outcome in sleep-disordered breathing: a prospective study. J Clin Sleep Med 18:739–750. 10.5664/jcsm.9694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camañes-Gonzalvo S, Marco-Pitarch R, Plaza-Espín A, Puertas-Cuesta J, Agustín-Panadero R, Fons-Font A, Fons-Badal C, G-S M, (2021) Correlation between polysomnographic parameters and tridimensional changes in the upper airway of obstructive sleep apnea patients treated with mandibular advancement devices. J Clin Med 10:5255. 10.3390/jcm10225255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gurgel ML, Junior CC, Cevidanes LHS, de Barros Silva PG, Carvalho FSR, Kurita LM, Cunha TCA, Dal Fabbro C, Costa FWG (2023) Methodological parameters for upper airway assessment by cone-beam computed tomography in adults with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath 27:1–30. 10.1007/s11325-022-02582-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.