Abstract

Protein tyrosine nitration (PTN) by oxidative and nitrative stress is a well-known post-translational modification that plays a role in the initiation and progression of various diseases. Despite being recognized as a stable modification for decades, recent studies have suggested the existence of a reduction in PTN, leading to the formation of 3-aminotyrosine (3AT) and potential denitration processes. However, the vital functions of 3AT-containing proteins are still unclear due to the lack of selective probes that directly target the protein tyrosine amination. Here, we report a novel approach to label and enrich 3AT-containing proteins with synthetic salicylaldehyde (SAL)-based probes: SALc-FL with a fluorophore and SALc-Yn with an alkyne tag. These probes exhibit high selectivity and efficiency in labeling and can be used in cell lysates and live cells. More importantly, SALc-Yn offers versatility when integrated into multiple platforms by enabling proteome-wide quantitative profiling of cell nitration dynamics. Using SALc-Yn, 355 proteins were labeled, enriched, and identified to carry the 3AT modification in oxidatively stressed RAW264.7 cells. These findings provide compelling evidence supporting the involvement of 3AT as a critical intermediate in nitrated protein turnover. Moreover, our probes serve as powerful tools to investigate protein nitration and denitration processes, and the identification of 3AT-containing proteins contributes to our understanding of PTN dynamics and its implications in cellular redox biology.

Introduction

Tyrosine, one of the 20 standard amino acids, plays a crucial role in neurotransmitter synthesis within the human body. Due to its aromatic phenol group, tyrosine can undergo various post-translational modifications (PTMs), including tyrosine phosphorylation catalyzed by tyrosine kinases, as first discovered by Hunter et al. in 1979.1 Additionally, tyrosine residues in proteins are susceptible to oxidative and nitrative modifications under conditions of excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), leading to the formation of 3-nitrotyrosine (3NT), 3,3′-dityrosine, 3-hydroxy-tyrosine, 3-chloro- and 3-bromotyrosine (Figure 1).2−5 The accumulation of 3NT, in particular, has been observed in various pathophysiological states and human diseases, including inflammation, allograft rejection, tumor angiogenesis, atherosclerosis, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease,6−16 indicating the close correlation of protein tyrosine nitration (PTN) with disease phenotypes. As a result, 3NT has emerged as a versatile biomarker of NO-dependent and RNS-induced oxidative stress.

Figure 1.

Protein modifications at tyrosine residues occur via different pathways.

While phosphorylation is a reversible modification, PTN has long been considered a stable PTM. However, recent studies have challenged this notion by demonstrating the potential reversibility of PTN.17 The disappearance of 3NT-containing proteins, as detected by anti-3NT antibodies, suggests the existence of a putative “denitrase” that converts 3NT back to tyrosine in cells and tissues.18,19 Although the identity of this “denitrase” remains speculative, evidence suggests that the NO2 group can be reduced to the NH2 group by a group of enzymes known as nitroreductases (NTRs).20,21 Studies have shown that 3NT can be converted to 3-aminotyrosine (3AT) through the action of endogenous NTRs like nitrate reductase and glutathione reductase in Escherichia coli.22 Furthermore, the formation of 3AT has been observed in α-synuclein from rotenone-treated PC12 cells.23 These experimental findings suggest that the conversion from 3NT to 3AT occurs in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. However, the biological significance of protein tyrosine amination (PTA) as a novel PTM remains unexplored, primarily due to the lack of effective methods for specific detection.

In this study, we present a novel analytical approach to detect and enrich 3AT-containing proteins using synthetic probes SALc-FL (with a fluorophore) and SALc-Yn (with an alkyne moiety), respectively. SALc-FL enables the direct detection of AT-containing proteins through fluorescence imaging in inflammatory macrophages. On the other hand, SALc-Yn, a bioorthogonal probe, allows for the profiling of 3AT-containing proteins. By incorporating this labeling method into a chemical proteomics workflow using mass spectrometry (MS), we successfully identified 355 proteins carrying 3AT modifications in oxidatively stressed RAW264.7 cells. Notably, we not only confirmed the presence of 3AT-modification sites within two known nitration target proteins, ANXA2 and GAPDH, through MS/MS analysis but also discovered numerous novel 3NT/3AT-modified proteins. These findings open up new avenues for investigating protein nitration and denitration processes, shedding light on the biological roles of PTN and providing valuable insights into cellular redox biology.

Results

Design and Synthesis of Salicylaldehyde (SAL)-Esters for Labeling PTA

We reasoned that 3NT-containing proteins could be detected by labeling 3AT-containing proteins, which could be generated through in vitro chemical reduction. Taking inspiration from serine/threonine ligation method developed by Li's group,25 we designed and synthesized a series of fluorescein-based SAL-esters 1a–c, considering the structural similarity shared among serine, threonine, and 3AT (Figure 2a). We evaluated the reactivity and efficiency of SAL-esters 1a–c in labeling reactions with Ac-3AT-OMe under physiological conditions. Among the SAL-esters tested, SAL-ester 1a demonstrated the highest reactivity, resulting in the detection and isolation of labeling product 2 in a yield of 31%. In contrast, only a trace amount of product was detected when using SAL-esters 1b and 1c (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Detection of PTA through 3AT labeling with SAL-esters. (a) Structures of SAL-esters 1a–f for labeling 3AT. (b) Activation of SAL-esters 1d–f through the general acid catalysis. (c) The plausible mechanism for labeling 3AT with SAL-esters. (d) Application of 1a in 3AT labeling in vitro using BSA derivatives in the presence of MMTS (20 mM), fluorescence image (top), and Coomassie blue stain (bottom).

Table 1. Efficiency and Yield of Labeling Reaction with SAL-Esters 1a–fa.

| entry | SAL-ester | yield |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1a | 12 h, 31% |

| 2 | 1b | 12 h, trace amountb |

| 3 | 1c | 12 h, trace amountc |

| 4 | 1d | 3 h, 36% |

| 5 | 1e | 3 h, 63% |

| 6 | 1f | 3 h, 50% |

Conditions: phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0), DMSO (2%, v/v), room temperature. The concentration of SAL-ester was 10 mM, and the concentration of Ac-3AT-OMe was 10 mM.

The majority of 1b was consumed by hydrolysis in the buffer.

No desired product was isolated due to the low reaction conversion.

In order to enhance the labeling efficiency, we introduced a hydroxyl group at the R3 position adjacent to the functional aldehyde in SAL-esters 1d–f, based on the general acid catalysis mechanism (Figure 2b). The labeling reaction likely proceeds through a two-step process (Figure 2c). In the first step, a Schiff base intermediate is formed between the SAL-ester and 3AT due to the low pKa of the aryl ammonium ion (4.75).26 In the second step, the imine intermediate undergoes 5-trig-endocyclization, equilibrating with its N,O-acetal form, which is subsequently converted into the labeling products through acyl transfer and hydrolysis. By utilizing SAL-esters 1d–f, we investigated their efficiency in labeling Ac-3AT-OMe in an aqueous buffer, achieving labeled product yields as high as 63% within 3 h at room temperature (Table 1).

To comprehensively evaluate the selectivity of SAL-esters in the labeling reaction, we selected 1a and 1d–f to assess their reactivity toward different amino acids containing nucleophilic residues. Surprisingly, these compounds exhibited low reactivity toward serine, threonine, and lysine under physiological conditions but were susceptible to attack by cysteine to varying degrees. Although SAL-esters 1d–f showed higher labeling efficiency than 1a, 1a displayed greater stability toward cysteine, likely attributing to the less reactive formyl group in 1a. Therefore, we utilized SAL-ester 1a to demonstrate in vitro PTN labeling using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a model protein, which contains 20 tyrosine residues.27 Nitration of BSA to generate 3NT-BSA was performed according to literature methods,28 followed by reduction with sodium dithionite. Using SAL-ester 1a, we selectively detected 3AT-BSA after blocking cysteine residues with S-methylmethanethiosulfonate (MMTS) (Figure 2d).

Design and Synthesis of SALc-FL and SALc-Yn for Selective PTA Labeling

To address the issue of reactivity with cysteine residues, we designed and synthesized two carbamate derivatives, SALc-FL (with a red fluorophore) and SALc-Yn (bearing an alkyne tag). The rationale behind using carbamate groups was to improve selectivity while maintaining reactivity similar to that of phenolic ester probes. The synthesis of these two molecules is illustrated in Scheme 1, and their labeling efficiency and selectivity were evaluated.

Scheme 1. Synthetic Routes of SALc-FL and SALc-Yn.

Under aqueous conditions, SALc-FL and SALc-Yn effectively labeled 3AT with yields of 44 and 67%, respectively (Table 2, Figures S1 and S2). It is noteworthy that SALc-FL and SALc-Yn exhibited remarkable inertness toward lysine, serine, and cysteine. In the selectivity test, UPLC-MS analysis showed no reaction or putative product after 24 h (Tables S1 and S2). These findings indicate that SALc-FL and SALc-Yn are promising molecular probes for detecting PTA. Furthermore, they can be utilized to identify and quantitate 3AT-containing proteins, opening up new possibilities for studying this novel PTM.

Table 2. Reactivity of SALc-FL and SALc-Yn for Labeling Ac-3AT-OMe.

Conditions: SALc-FL (10 mM), Ac-3AT-OMe (10 mM), sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0), DMSO (2%, v/v), room temperature.

SALc-Yn (10 mM), Ac-3AT-OMe (10 mM), sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0), MeOH (10%, v/v), room temperature.

Detection of PTN and Endogenous PTA with SALc-FL in Complex Biological Samples

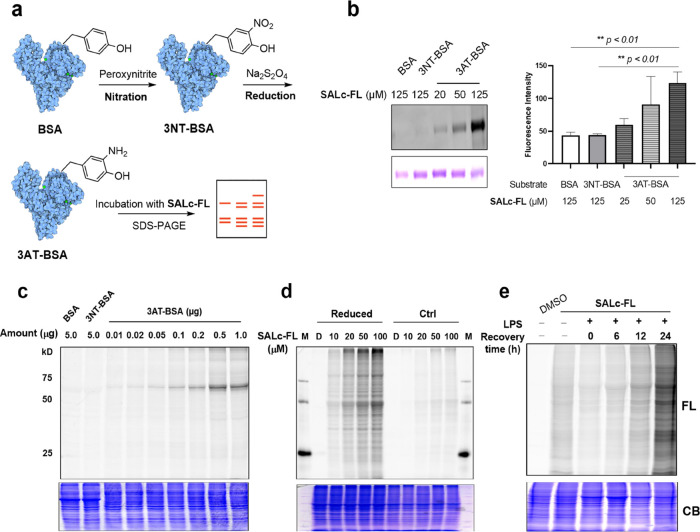

Using SALc-FL, we conducted labeling experiments on chemically derivatized BSA, both as a purified protein and as a spiked-in protein in cell lysates without cysteine blockade. Interestingly, SALc-FL specifically labeled 3AT-BSA, while BSA and 3NT-BSA did not show any labeling (Figure 3b). To further assess the probe’s performance, we included lysozyme, which contains only three tyrosine residues, in the chemical derivatization process for 3NT and 3AT. When these proteins and their corresponding derivatives were spiked into whole cell lysates, SALc-FL successfully detected 3AT-containing proteins despite the complex background containing various nucleophile species (Figures 3c and S3).

Figure 3.

Application of SALc-FL to detect PTA and PTN. (a) Schematic illustration of the chemically modified BSA. (b) Labeling of BSA, 3NT-BSA, and 3AT-BSA by SALc-FL (left), fluorescence image (top), Coomassie blue stain (bottom), and quantification analysis of the fluorescent intensity (right), the error bars represent the mean ± SD (n = 3, **P < 0.01). (c) Assessment of the labeling specificity of SALc-FL (100 μM) by incubating with a mixture of RAW264.7 cell lysate and BSA, nitrated BSA (3NT-BSA), or nitrated and reduced BSA (3AT-BSA), respectively, fluorescence image (top), and Coomassie blue stain (bottom). (d) Detection of 3NT-containing proteins in the brain extracts from EAE mouse, fluorescence image (top), and Coomassie blue stain (bottom). Brain proteins were reduced with 100 mM Na2S2O4 (reduced) or not (Ctrl) before the labeling reaction. Proteins were treated with indicated concentrations of SALc-FL (10–100 μM) or DMSO (D) as the negative control. “M” means protein marker ladders. (e) In vitro labeling of endogenous 3AT-containing proteins with SALc-FL (100 μM) in lysates of LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells with recovery for 0–24 h, fluorescence image (top), and Coomassie blue stain (bottom).

Furthermore, SALc-FL was employed to detect PTN in brain samples from a mouse model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a model for multiple sclerosis.29 The oxidative injury in human multiple sclerosis lesions has been extensively documented,30 and PTN has been reported to cause toxic gain-of-function in neuronal cells.31 After sodium dithionite reduction, SALc-FL successfully detected 3NT-containing proteins in EAE mouse brain tissue (Figure 3d). These results demonstrate that SALc-FL can be widely applied to pure proteins, cell lysates, and brain tissues for the detection of PTA and PTN, with good sample compatibility and high efficiency.

In response to proinflammatory stimuli like bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), murine macrophages undergo oxidative stress and accumulate PTN.32 It has been reported that under physiological conditions and in the presence of reductants such as ascorbic acid with hemoglobin/myoglobin and rotenone, the conversion from 3NT to 3AT can occur.23,28 With this in mind, we aimed to capture some of the nitrated proteins that could potentially be converted to 3AT by the native reducing environment in live cells, either through enzyme-dependent or independent denitration processes.33

Since SAL-carbamate probe SALc-FL was found to be noncytotoxic at concentrations below 50 μM (Figure S4), it could be used to detect endogenous 3AT-containing proteins. We stimulated RAW264.7 cells with LPS, allowed the cells to recover from oxidative injuries (by removing LPS), and subsequently performed the labeling reaction in cell lysates using SALc-FL. While a few 3AT-containing proteins were detected in a time-dependent manner after 12 h of recovery (Figure 3e), the presence of 3AT-containing proteins was observed using confocal fluorescence imaging as early as 6 h post-stimulation (Figures 4 and S5). These findings indicate that SALc-FL can effectively detect endogenous 3AT-containing proteins in live cells, allowing for the study of PTN dynamics and the potential denitration processes that occur.

Figure 4.

Confocal fluorescence imaging of 3AT-containing proteins in RAW264.7 cells with SALc-FL. RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with LPS (200 ng/mL) for 16 h and then recovered for 0 or 6 h. All cells were stained with SALc-FL (10 μM, λex = 561 nm, λem = 622 nm).

Applications of SALc-Yn for Detecting PTA

In addition to the rhodamine-based probe SALc-FL, we also designed SALc-Yn with a bioorthogonal handle that enables fluorescence visualization and target identification. To evaluate the labeling efficiency of SALc-Yn, a model peptide containing 3AT was synthesized (Figure 5a). The labeling specificity was assessed by monitoring the mass fragments of the peptide in each step (Figure S6). SALc-Yn selectively labeled the model peptide LISWY(3AT)DNEF with the modification site (+150.0793 Da) detected by using MS analysis (Figure 5b). To confirm the specificity of the probe for 3AT labeling in the presence of nucleophilic amino acids, another peptide LCAYGKG containing cysteine and lysine residues was employed in the labeling reaction. MS analysis identified a labeled product with a mass-to-charge ratio of 861.42 ([M + H]+), aligning with the anticipated mass of the probe-modified peptide (Figure S7). High-resolution tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) further verified the precise site of labeling, clearly identifying the 3AT residue as the modification site.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of labeling efficiency by SALc-Yn. (a) Schematic of synthetic peptides with different modifications on tyrosine residues. (b) Confirmation of the adduct formed between the probe and 3AT-modified peptides by LC-MS/MS. (c) The labeling effect of the probe on purified GAPDH (left) and cytochrome c (right). Anti-NT means anti-nitrotyrosine antibody; “FL” represents fluorescence intensity; “CB” represents Coomassie blue staining. (d) Target-specific labeling on 3AT-GAPDH in RAW264.7 cell lysates with SALc-Yn (100 μM), fluorescence image (left), and Coomassie blue stain (right). (e) The immunoblot analysis for nitrotyrosine level in RAW264.7 cell lysates derived from the nontreated, LPS-treated with or without recovery (left), and the signals were quantified densitometrically (right); the error bars represent the mean ± SD (n = 3; **P < 0.01, LPS versus control; #P < 0.05, recovery versus LPS). (f) The in-gel fluorescence detection of PTA with SALc-Yn in the RAW264.7 cell lysates derived from the nontreated, LPS-treated with or without recovery (left), and quantification of the fluorescent intensity (right); the error bars represent the mean ± SD (n = 3; **P < 0.01, recovery versus LPS).

After confirming the specificity of the labeling reaction at the peptide level, we further investigated the labeling efficiency of SALc-Yn toward chemically modified proteins, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), and cytochrome c, both known for PTN.34,35 This evaluation was performed using either purified proteins (Figure 5c) or cell lysates containing spiked-in proteins (Figure 5d). The gel-fluorescent assay demonstrated that SALc-Yn can robustly detect 3AT-containing proteins with exceptional sensitivity and efficiency. To further investigate the labeling sites, cytochrome c was sequentially subjected to nitration, reduction, labeling with SALc-Yn, digestion with trypsin, and LC-MS/MS analysis. The 3NT-, 3AT-, and SALc-Yn-modified peptide sequences were identified (Figure S8). Notably, residues Y49, Y68, Y75, and Y98 were conclusively recognized as modification sites (Table S3). This precise mapping of modified residues provides valuable insights into the targeted sites where the probe interacts with 3AT-modified cytochrome c. These results highlight the potential of SALc-Yn as a valuable tool for labeling and visualizing 3AT-containing proteins, allowing for the identification and characterization of proteins modified by PTN.

To further validate the presence of endogenous 3AT-containing proteins, we employed SALc-Yn to monitor their levels and used 3NT antibodies to assess the levels of 3NT-containing proteins during LPS stimulation in murine macrophages. We observed a significant increase in the levels of 3NT-containing proteins in cells stimulated with LPS (P < 0.01), which returned to basal levels after 24 h of recovery (Figure 5e). Interestingly, although there was no noticeable difference in the levels of 3AT-containing proteins between the LPS-stimulated and control groups, an induced level of 3AT-containing proteins was detected in the recovery group (Figure 5f). These results suggest that the decrease in the levels of 3NT-containing proteins observed in the recovery group is likely due to the conversion of 3NT- to 3AT-containing proteins, which corresponds to the increased levels of 3AT-containing proteins labeled by SALc-Yn. These findings provide supporting evidence for the presence of endogenous 3AT-containing proteins and suggest a potential role for enzymatic or nonenzymatic denitration processes in the conversion of 3NT to 3AT under physiological conditions. The combination of SALc-Yn and 3NT antibodies allows for the simultaneous monitoring of both PTN and its potential denitration products, providing valuable insights into the dynamics of these PTMs.

Proteome-Wide Profiling of Endogenous 3AT-Containing Proteins

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the biological implications of 3AT-containing proteins, we utilized SALc-Yn to profile these proteins in activated macrophages. In general, RAW264.7 cells were subjected to a 16 h treatment with LPS, followed by a 24 h recovery period to induce the formation of 3AT-containing proteins. Concurrently, the LPS stimulation of RAW264.7 cells led to the generation of 3NT-modified proteins in the cell lysates, which were utilized for the production of 3AT-containing proteins through chemical reduction with sodium dithionite. Subsequently, all cell lysates were incubated with SALc-Yn, followed by biotin incorporation through a “click chemistry” for subsequent pull-down with streptavidin resin. The enriched peptides were identified and quantified by utilizing label-free quantification (LFQ) methods (Figure 6a). The effectiveness of the enrichment method was evaluated through anti-biotin immunoblotting analysis, which showed a clear difference between the control sample and the ones subjected to either chemical reduction or the cell recovery (Figure S9a). Moreover, hierarchical clustering analysis confirmed what we observed in the immunoblotting. Notably, the observed difference between the samples underwent chemical reduction and those post-recovery (Figure S9b) was marginal. There was substantial overlap between the two groups, with 355 proteins (82%) common to both, suggesting that a significant portion of 3NT-modified proteins were reduced to their 3AT-modified counterparts during cell recovery (Figure 6b,c). We observed that 431 proteins exhibited more than a 2-fold enrichment in the samples subjected to chemical reduction, whereas 358 proteins displayed heightened abundance in the samples undergoing a 24 h recovery period (Supplemental Data S1–2). Labeled peptides were detected with consistent modification sites in both sets of samples (Figures 6d and S10), which implies the potential role for the cell recovery in promoting the conversion from 3NT to 3AT. Among those 358 proteins, many are well-known tyrosine nitration targets, such as peroxiredoxin 2, ANXA2, histone H3, and Aldolase A,24,36,37 yet numerous proteins were found as novel targets for both tyrosine nitration and amination, which include the DEAD-box protein family (DDX1, DDX5, DDX3x, DDX18, and DDX21), known for their involvement in ATP binding, ATP hydrolysis, and RNA binding.38 These data further support the effectiveness of the SALc-Yn probe in discovering 3AT-containing proteins in complex biological samples.

Figure 6.

Chemoproteomic profiling of 3AT-containing proteins in activated RAW264.7 cells. (a) General workflow for profiling 3AT-containing proteins. (b) The number of identified 3AT-containing proteins by the LFQ analysis method. (c) Venn diagram shows the identified 3AT-containing proteins and (d) SALc-Yn-labeled peptides from the samples with chemical reduction (“LPS”) and 24 h recovery (“Rec”). (e) Venn diagram showing the cellular compartment distribution of 355 identified proteins via GO analysis. (f) Protein class enrichment of 3AT-containing proteins. (g) Western-blot analysis showing the enrichment of HSP90α/β, GAPDH, and H3. RAW264.7 cells were treated with probe SALc-Yn (+) or the same volume of DMSO (−) for the negative control for 3AT-containing protein labeling. (h) Validation of endogenous 3AT-modified GAPDH by immunoprecipitation (IP). “FL” represents for fluorescent image; “CB” represents for Coomassie blue stain.

Following the identification of 3AT-containing proteins, we conducted a Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis to categorize and elucidate their functional roles. The analysis unveiled that 3AT-modified proteins are widespread in several vital cellular compartments, with a notable presence in the nucleus and mitochondria (Figure 6e). These findings are consistent with previous studies that detected nitrated proteins across various cell regions, including the cytoplasm, nucleus, and mitochondria.39 Furthermore, 3AT-modified proteins are involved in crucial cellular processes such as the activation of proteasomes, chaperone-mediated protein folding, and ATP-dependent mechanisms (Figure 6f), indicating that they could play various roles in cells. In addition to GO analysis, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis suggested these 3AT-modified proteins participate in a broad spectrum of biological activities, including the ribosomes, carbon metabolism, and Parkinson’s disease (Figure S11). These findings advance our understanding of the divergent functions which 3AT-modified proteins may exert, as well as their possible significance in overarching cellular dynamics and disease states.

To validate the identification of 3AT-modified proteins, we specifically selected known nitration targets, including histone H3,24 GAPDH,34 and HSP90α/β,40 which exhibited different enrichment ratios in both groups. The proteins labeled with SALc-Yn in lysates from LPS-stimulated and recovered RAW264.7 cells were conjugated with biotin and subjected to immunoblotting before and after streptavidin enrichment. The results demonstrated the successful capture of all three proteins by SALc-Yn (Figure 6g). To further confirm the identification, we performed immunoprecipitation (IP) using an anti-GAPDH antibody. The immunoblot analysis revealed a decrease in the level of nitrated-GAPDH after recovery, while the corresponding fluorescent intensity for 3AT-GAPDH increased significantly. These data provide evidence of the conversion from 3NT-modified GAPDH to its 3AT-modified counterpart during the recovery phase following LPS stimulation in RAW264.7 cells (Figure 6h).

Additionally, SALc-Yn was employed to visualize endogenous 3AT-containing proteins in RAW264.7 cells after LPS stimulation and recovery. After conjugation with rhodamine azide, the fluorescence signal was observed in both the cytoplasm and nucleus (Figure S12). This observation is consistent with the results obtained from chemical proteomic profiling using SALc-Yn, which indicated that most labeled proteins are localized in the cytoplasm. Thus, SALc-Yn has the capability to detect endogenous 3AT-containing proteins and provide insights into their potential cellular distribution.

Validation of the 3NT and 3AT-Modification Sites with MS

To validate the 3NT and 3AT-modification sites, we performed overexpression experiments on two proteins: GAPDH, known to have 3NT modification sites at Y312 and Y316, and ANXA2, a reported nitrated protein. Flag-tagged versions of these target proteins were overexpressed in RAW264.7 cells, with or without doxycycline treatment, to induce the target protein expression (Figure S13a). Immunoblot analysis confirmed the successful establishment of stable cell lines expressing target proteins. Subsequently, these proteins were efficiently enriched after overexpression (Figure S13b). To identify peptides with different modification sites, we performed in-gel digestion on the isolated target proteins obtained through gel electrophoresis. The resulting peptides were then subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis to determine the specific modification sites.

As a result, a total of 15 3NT-containing peptides were identified, with 12 peptides originating from ANXA2 and three peptides from GAPDH (Table S4). These peptides exhibited various modification sites, indicating the presence of multiple tyrosine nitration sites in these proteins. The annotated MS/MS spectra of the 3NT or 3AT peptides can be found in Supplemental Data S5–6. Notably, most of the 3NT-modified sites were also identified as 3AT-modified sites. For instance, Y316 of GAPDH was found to be both a 3NT and 3AT-modified site (Figure 7). Similarly, Y312 of GAPDH, as well as Y30, Y75, Y109, and Y188 of ANXA2, were identified with both 3NT and 3AT modifications (Figure S14). Furthermore, several tyrosine residues were also labeled by probe SALc-Yn in pull-down ANXA2 and GAPDH, such as Y30 and Y316 of ANXA2, and Y312 of GAPDH, respectively. Further studies are required to investigate the effects of these modifications on protein structure and function. Such investigations will provide insights into the functional implications of these modifications and their potential roles in cellular processes and disease pathways.

Figure 7.

Identification of tyrosine modification sites via the overexpression method. Annotated MS/MS spectra of representative 3NT-(green) and 3AT-modified (blue) peptides, and the modified Y were highlighted in different colors.

Discussion and Conclusions

In summary, we focused on the identification and characterization of 3AT-containing proteins, a novel PTM resulting from the reduction of 3NT modifications. The low abundance of 3NT and 3AT modifications in proteins under stressed conditions presents challenges in investigating denitration pathways. To address this, we have developed probes SALc-FL and SALc-Yn, which demonstrated superior labeling selectivity for 3AT-containing proteins in complex biological samples.

The excellent selectivity of those two probes toward 3AT over other amino acids can be explained by the disparity in pKa values between the aryl ammonium ion (4.75) and the aliphatic ammonium ion (9.21 for serine, 9.10 for threonine, and 10.54 for lysine). Under physiological conditions, 3AT remains neutral and retains its nucleophilicity, whereas serine, threonine, and lysine, being in their zwitterionic forms, exhibit significantly reduced nucleophilicity. In addition, we noticed that SALc-Yn gave a faster reaction with 3AT and exhibited superior compatibility under biological conditions compared to the previously reported serine/threonine ligation method that needs to be carried out at a high substrate concentration and in a pyridine/acetic acid mixture.25

The SALc-FL probe enabled the detection and visualization of endogenous 3AT-containing proteins in live cells without the need for in vitro chemical derivatization. This allowed for the monitoring and investigation of protein tyrosine aminotyrosine (PTA), a novel PTM associated with oxidative stress induced by LPS in macrophage cells. On the other hand, the SALc-Yn probe provided versatility by allowing conjugation with different moieties such as fluorophores or biotin for the detection or pull-down identification of endogenous 3AT-containing proteins.

Chemical proteomics analysis using SALc-Yn revealed 431 proteins with 3NT modification in the sample subjected to chemical reduction and 358 proteins with 3AT-modification in the sample after a 24 h recovery period. Gratifyingly, 82% of the proteins with the modification were reproducibly detected in both groups, suggesting that the reduction of 3NT-modified proteins to 3AT-containing proteins becomes a major pathway during the cell recovery process. This comprehensive identification of 3AT-modified proteins provides valuable insights into a potential denitration pathway, and our results revealed that the originally proposed “denitrase” activity could actually involve a reduction of 3NT-proteins to 3AT-proteins. Those 3AT-containing proteins are likely key players during denitration and could have vital biological functions yet to be discovered. The probes SALc-FL and SALc-Yn serve as novel tools to validate the existence of endogenous 3AT-containing proteins, contributing to our understanding of their biological functions and their involvement in the denitration pathway.

In addition to studying PTN, there have been ongoing efforts to elucidate the structure–function relationship and understand the association between specific nitration events and pathological phenotypes. Current analytical methods for PTN detection primarily focus on profiling 3NT-containing proteins and determining their distribution. However, obtaining site-specific information at the molecular level is essential to investigate the relationship between 3NT formation and protein functional alterations. Established approaches for PTN analysis, such as immunochemical methods combined with gel electrophoresis followed by MS analysis,41 have limitations regarding the reproducibility of gel electrophoresis and the specificity of 3NT-immunochemistry,42 which complicates subsequent MS analysis. In contrast, the SALc-FL and SALc-Yn probes offer complementary tools for investigating PTN. The efficient derivatization from 3NT- to 3AT-containing proteins using chemical reductants allows for the investigation of PTN at the molecular level. Thus, probes SALc-FL and SALc-Yn not only serve as powerful tools to investigate the effect of 3AT modification on protein structures and functions but also contribute to advancing our understanding of the biological effects of nitrated proteins.

In conclusion, this research provides valuable insights into the field of PTN and offers innovative tools and approaches for studying and characterizing 3AT-containing proteins and their functional implications. Understanding the biological mechanisms and pathways linked to PTN and the subsequent reduction to aminotyrosine is foundational in uncovering the potential impact on signal transduction. This extensive knowledge forms a solid basis for future investigations into the relevance of these PTMs in cellular function and pathology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. J. Shen from the School of Chinese Medicine, The University of Hong Kong (HKU), for providing EAE mouse brain extracts for the labeling reactions. We thank Dr. Q. Zhao from the Department of Applied Biology and Chemical Technology, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, for collecting MS data for the labeling reaction with the synthetic peptide (LCAYGKG). We thank the Centre for Genomic Science at HKU for support in fluorescent visualization. This work was funded by The University of Hong Kong, The University Development Fund, the Morningside Foundation, the Westlake Education Foundation, and the Hong Kong Research Grants Council under the Area of Excellence Scheme (AoE/P-705/16), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32150005 to C.C.W), Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2022YFA0806000 to C.C.W), Clinical Research Operating Fund of Central High-level Hospitals (2022-PUMCH-E-001 to C.C.W), Medical and Scientific Innovation Project of the Chinese Academy of Medical Science (2022-12M-1-004 to C.C.W), and Talent Program of the Chinese Academy of Medical Science (2022-RC310-10 to C.C.W).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.4c01028.

UPLC traces of starting materials and the reaction between Ac-3AT-OMe and SALc-FL (and SALc-Yn); assessment of labeling specificity of SALc-FL; cytotoxicity of SALc-FL and SALc-Yn; confocal fluorescence imaging of 3AT-containing proteins labeled with SALc-FL in RAW264.7 cells; LC-MS/MS analysis of synthetic peptides; enrichment efficiency of 3AT-modified proteins; representative MS/MS spectra of SALc-Yn-labeled peptides; KEGG enrichment analysis of the identified 3AT-containing proteins; immunofluorescent staining of LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells; immunoblot analysis of protein expression and immunoprecipitation; reactivity and selectivity of SALc-FL (and SALc-Yn); identification of SALc-Yn labeled sites in 3AT-modified cytochrome c; modified peptides detected with high peptide spectrum match; and experimental procedures, synthesis, characterization of compounds, MS/MS spectra, and NMR spectra (PDF)

List of protein targets and proteomic data (XLSX)

Author Contributions

∇ L. Chen and T. Yang contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Eckhart W.; Hutchinson M. A.; Hunter T. An activity phosphorylating tyrosine in polyoma T antigen immunoprecipitates. Cell 1979, 18 (4), 925–933. 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90205-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abello N.; Kerstjens H. A. M.; Postma D. S.; Bischoff R. Protein tyrosine nitration: selectivity, physicochemical and biological consequences, denitration, and proteomics methods for the identification of tyrosine-nitrated proteins. J. Proteome Res. 2009, 8 (7), 3222–3238. 10.1021/pr900039c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coval M. L.; Taurog A. Purification and iodinating activity of hog thyroid peroxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1967, 242 (23), 5510–5523. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)99388-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaloni A.; Mass spectrometry approaches for the molecular characterization of oxidatively/nitrosatively modified proteins; In Redox Proteomics: From Protein Modifications to Cellular Dysfunction and Diseases; Wiley-Interscience, 2006,; pp. 59–99. [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman E. R.; Levine R. L., ;. Chemical modification of proteins by reactive oxygen species; In Redox Proteomics: From Protein Modifications to Cellular Dysfunction and Diseases; Wiley-Interscience, 2006,; pp 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev V. A.; Mikkelsen R. B. Protein tyrosine nitration in cellular signal transduction pathways. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2010, 30 (6), 420–429. 10.3109/10799893.2010.513991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galen M. P.; Irina A. I.; Brian C. C.; Raymond Q. M.; Ashwani K. K.; Jennifer W.; Jeannette V.-V. Sepiapterin decreases acute rejection and apoptosis in cardiac transplants independently of changes in nitric oxide and inducible nitric-oxide synthase dimerization. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 329 (3), 890–899. 10.1124/jpet.108.148569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan-Crow L. A.; Crow J. P.; Kerby J. D.; Beckman J. S.; Thompson J. A. Nitration and inactivation of manganese superoxide dismutase in chronic rejection of human renal allografts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996, 93 (21), 11853–11858. 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlides S.; Tsirigos A.; Vera I.; Flomenberg N.; Frank P. G.; Casimiro M. C.; Wang C.; Fortina P.; Addya S.; Pestell R. G.; Martinez-Outschoorn U. E.; Sotgia F.; Lisanti M. P. Loss of stromal caveolin-1 leads to oxidative stress, mimics hypoxia and drives inflammation in the tumor microenvironment, conferring the “reverse Warburg effect”: A transcriptional informatics analysis with validation. Cell Cycle 2010, 9 (11), 2201–2219. 10.4161/cc.9.11.11848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upmacis R. K. Atherosclerosis: a link between lipid intake and protein tyrosine nitration. Lipid Insights 2008, 2, 75. 10.4137/LPI.S1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turko I. V.; Li L.; Aulak K. S.; Stuehr D. J.; Chang J.-Y.; Murad F. Protein tyrosine nitration in the mitochondria from diabetic mouse heart: implications to dysfunctional mitochondrial in diabetes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278 (36), 33972–33977. 10.1074/jbc.M303734200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H.; Halliwell B. Evidence for nitric oxide-mediated oxidative damage in chronic inflammation Nitrotyrosine in serum and synovial fluid from rheumatoid patients. FEBS Lett. 1994, 350 (1), 9–12. 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M. R.; Berry R. W.; Binder L. I. Site-specific nitration and oxidative dityrosine bridging of the τ protein by peroxynitrite: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry 2005, 44 (5), 1690–1700. 10.1021/bi047982v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan M. W. A review of approaches to the analysis of 3-nitrotyrosine. Amino Acids 2003, 25 (3–4), 351–361. 10.1007/s00726-003-0022-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B.; Rizzo V. TNF-alpha potentiates protein-tyrosine nitration through activation of NADPH oxidase and eNOS localized in membrane rafts and caveolae of bovine aortic endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. 2007, 292 (2), H954–H962. 10.1152/ajpheart.00758.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. J. Mitochondrial dysfunction in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease revealed by transcriptomics and proteomics. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr 2009, 41 (6), 487–491. 10.1007/s10863-009-9254-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamisaki Y.; Wada K.; Bian K.; Balabanli B.; Davis K.; Martin E.; Behbod F.; Lee Y. C.; Murad F. An activity in rat tissues that modifies nitrotyrosine-containing proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998, 95 (20), 11584–11589. 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krainev A. G.; Williams T. D.; Bigelow D. J. Enzymatic reduction of 3-nitrotyrosine generates superoxide. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1998, 11 (5), 495–502. 10.1021/tx970201p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeck T.; Fu X.; Hazen S. L.; Crabb J. W.; Stuehr D. J.; Aulak K. S. Rapid and selective oxygen-regulated protein tyrosine denitration and nitration in mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279 (26), 27257–27262. 10.1074/jbc.M401586200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel L. C.; Montalto de Mecca M.; Castro J. A. Nitroreductive metabolic activation of some carcinogenic nitro heterocyclic food contaminants in rat mammary tissue cellular fractions. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47 (1), 140–144. 10.1016/j.fct.2008.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning T. M.; Su A. L.; El-Bayoumy K. Nitroreduction: a critical metabolic pathway for drugs, environmental pollutants, and explosives. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35 (10), 1747–1765. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.2c00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerding H. R.; Karreman C.; Daiber A.; Delp J.; Hammler D.; Mex M.; Schildknecht S.; Leist M. Reductive modification of genetically encoded 3-nitrotyrosine sites in alpha synuclein expressed in E.coli. Redox Biol. 2019, 26, 101251 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei H.; Schieler J. L.; Rochet J.-C.; Regnier F. Identification of rotenone-induced modifications in α-synuclein using affinity pull-down and tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 2006, 78 (7), 2422–2431. 10.1021/ac051978n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Zhang Y.; Sun H.; Maroto R.; Brasier A. R. Selective affinity enrichment of nitrotyrosine-containing peptides for quantitative analysis in complex samples. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16 (8), 2983–2992. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Lam H. Y.; Zhang Y.; Chan C. K. Salicylaldehyde ester-induced chemoselective peptide ligations: enabling generation of natural Peptidic linkages at the serine/threonine sites. Org. Lett. 2010, 12 (8), 1724–1727. 10.1021/ol1003109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolovsky M.; Riordan J. F.; Vallee B. L. Conversion of 3-nitrotyrosine to 3-aminotyrosine in peptides and proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1967, 27 (1), 20–25. 10.1016/S0006-291X(67)80033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujacz A. Structures of bovine, equine and leporine serum albumin. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2012, 68 (Pt 10), 1278–1289. 10.1107/S0907444912027047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balabanli B.; Kamisaki Y.; Martin E.; Murad F. Requirements for heme and thiols for the nonenzymatic modification of nitrotyrosine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999, 96 (23), 13136–13141. 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu C. S.; Farooqi N.; O’Brien K.; Gran B. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) as a model for multiple sclerosis (MS). Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 164 (4), 1079–1106. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassmann H.; van Horssen J. Oxidative stress and its impact on neurons and glia in multiple sclerosis lesions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862 (3), 506–510. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jandy M.; Noor A.; Nelson P.; Dennys C. N.; Karabinas I. M.; Pestoni J. C.; Singh G. D.; Luc L.; Devyldere R.; Perdomo N.; Mitchell C. E.; Adams L.; Fuse M. A.; Mendoza F. A.; Marean-Reardon C. L.; Mehl R. A.; Estevez A. G.; Franco M. C. Peroxynitrite nitration of Tyr 56 in Hsp90 induces PC12 cell death through P2 × 7R-dependent PTEN activation. Redox Biol. 2022, 50, 102247 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y.; Zweier J. L. Superoxide and peroxynitrite generation from inducible nitric oxide synthase in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997, 94 (13), 6954–6958. 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. J.; Chang C. M.; Lin W. P.; Cheng D. L.; Leong M. I. H2O2/nitrite-induced post-translational modifications of human hemoglobin determined by mass spectrometry: redox regulation of tyrosine nitration and 3-nitrotyrosine reduction by antioxidants. Chembiochem 2008, 9 (2), 312–323. 10.1002/cbic.200700541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamalai V.; Miyagi M. Mechanism of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase inactivation by tyrosine nitration. Protein Sci. 2010, 19 (2), 255–262. 10.1002/pro.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Heredia J. M.; Díaz-Moreno I.; Nieto P. M.; Orzáez M.; Kocanis S.; Teixeira M.; Pérez-Payá E.; Díaz-Quintana A.; De la Rosa M. A. Nitration of tyrosine 74 prevents human cytochrome c to play a key role in apoptosis signaling by blocking caspase-9 activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1797 (6–7), 981–993. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall L. M.; Manta B.; Hugo M.; Gil M.; Batthyàny C.; Trujillo M.; Poole L. B.; Denicola A. Nitration transforms a sensitive peroxiredoxin 2 into a more active and robust peroxidase. J. Chem. Biol. 2014, 289 (22), 15536–15543. 10.1074/jbc.M113.539213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacksteder C. A.; Qian W.-J.; Knyushko T. V.; Wang H.; Chin M. H.; Lacan G.; Melega W. P.; Camp D. G.; Smith R. D.; Smith D. J.; Squier T. C.; Bigelow D. J. Endogenously nitrated proteins in mouse brain: links to neurodegenerative disease. Biochemistry 2006, 45 (26), 8009–8022. 10.1021/bi060474w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder P.; Jankowsky E. From unwinding to clamping-the DEAD box RNA helicase family. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12 (8), 505–516. 10.1038/nrm3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Loo B.; Labugger R.; Skepper J. N.; Bachschmid M.; Kilo J.; Powell J. M.; Palacios-Callender M.; Erusalimsky J. D.; Quaschning T.; Malinski T.; Gygi D.; Ullrich V.; Lüscher T. F. Enhanced peroxynitrite formation is associated with vascular aging. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192 (12), 1731–1744. 10.1084/jem.192.12.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco M. C.; Ye Y.; Refakis C. A.; Feldman J. L.; Stokes A. L.; Basso M.; Fernández Melero; de Mera R. M.; Sparrow N. A.; Calingasan N. Y.; Kiaei M.; Rhoads T. W.; Ma T. C.; Grumet M.; Barnes S.; Beal M. F.; Beckman J. S.; Mehl R.; Estévez A. G. Nitration of Hsp90 induces cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110 (12), E1102–E1111. 10.1073/pnas.1215177110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokulrangan G.; Zaidi A.; Michaelis M. L.; Schöneich C. Proteomic analysis of protein nitration in rat cerebellum: effect of biological aging. J. Neurochem. 2007, 100 (6), 1494–1504. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikov G.; Bhat V.; Wishnok J. S.; Tannenbaum S. R. Analysis of nitrated proteins by nitrotyrosine-specific affinity probes and mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 2003, 320 (2), 214–222. 10.1016/S0003-2697(03)00359-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.