Cardiogenic shock (CS) is a heterogenous disease process with varied clinical presentation, aetiology and severity. Owing to such heterogeneity, it is difficult to prognosticate patients in CS at their initial clinical encounter. While the Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) stages of CS have been validated as a prognostic tool, they rely on several biomarkers and invasive haemodynamic variables that may delay their assessment.[1] The aim of our analysis was to assess the relationship between a universal risk factor, patient's age and mortality in CS. Patient's age is readily available at the initial encounter and remains a non-modifiable risk factor.

We queried a large national database to assess this relationship between patient's age and mortality in CS. Multiple baseline comorbidities and severity of illness were intentionally not adjusted in the hopes of providing more of a rapid, early, ‘first look’ and global prognostication for CS patients.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the National Inpatient Sample dataset from 2016 to 2018. The National Inpatient Sample, sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient healthcare database designed to produce US regional and national estimates of inpatient usage, access, cost, quality and outcomes. The study population included adult patients (age ≥18 years) hospitalised with a diagnosis of CS, as identified by the ICD-10-CM code R57.0. We excluded patients with missing age or outcome data on mortality.

The primary outcome of interest was in-hospital mortality, defined as death occurring during the index hospitalisation. Patients were grouped into age deciles. We further stratified the study population based on the presence or absence of acute MI (AMI), identified by ICD-10-CM code I21, to study if age remained a relevant association in patients with AMI and CS.

The complex samples module in IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 (IBM) was used to account for the stratified sampling design of the National Inpatient Sample datasets. Categorical variables are summarised as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges, as appropriate.

In-hospital mortality was reported for the total cardiogenic shock group, as well as separately for the AMI and no-AMI subgroups. Mortality rates were also reported for each age decile within the total group, and the AMI and no-AMI subgroups. Graphical trends of mortality rates across age deciles were created.

Results

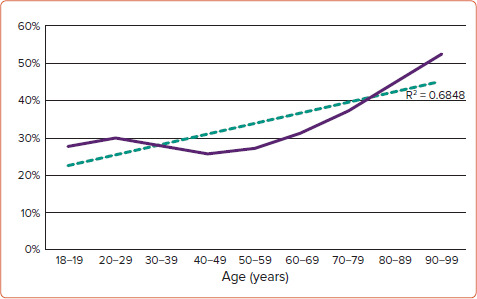

A total of 490,370 admissions for cardiogenic shock were identified during the study period. Baseline characteristics of the cohort are summarised in Table 1. Overall mortality during index hospitalisation in our cohort of CS patients was 34.5%. Mortality was higher in the AMI-CS cohort compared with the non-AMI cohort (36 versus 33.5%, p<0.001). In-hospital mortality occurred in 29.9% of patients aged 20–29 years, and rose to 52.4% among the oldest cohort (age 90–99 years). The rate of increase in mortality during index hospitalisation with age was statistically significant (R[2]=0.6848, p<0.0001). (Figure 1) These trends were similar in the AMI-CS cohort (R[2]=0.786, p<0.0001) and the non-AMI-CS cohort (R[2]=0.6895, p<0.0001).

Table 1: Baseline Characteristics of the Study Cohort.

| Characteristic | Overall | AMI-CS | Non-AMI-CS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (median) | 68 (58–77) | 69 (60–78) | 67 (57–77) |

| Male | 62% | 64% | 62% |

| HTN | 74% | 74% | 74% |

| DM | 39% | 42% | 37% |

| DLD | 42% | 48% | 37% |

| CAD | 71% | 100% | 52% |

| AF | 25% | 18% | 29% |

| PVD | 21% | 16% | 24% |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 27% | 24% | 29% |

| Obesity | 17% | 15% | 17% |

| ESRD | 8% | 7% | 8% |

| IABP | 1% | 1% | <1% |

| pVAD | 5% | 9% | 2% |

| VA-ECMO | 2% | 2% | 2% |

| Any t-MCS | 8% | 12% | 5% |

AMI-CS = acute MI and cardiogenic shock; CAD = coronary artery disease; DLD = dyslipidaemia; DM = diabetes; ESRD = end-stage renal disease; HTN = hypertension; IABP = intra-aortic balloon pump; pVAD = percutaneous ventricular assist device; PVD = peripheral vascular disease; t-MCS = temporary mechanical circulatory support; VA-ECMO = venous-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Figure 1: All Cardiogenic Shock and Mortality.

Discussion

The key finding of our analysis is that mortality during index hospitalisation among patients presenting in CS consistently rises with each decade of life. Age provides a universally available ‘first look’ assessment, and this relationship exists in both the AMI and non-AMI-CS cohorts.

Our findings are in line with the previously published Cardiogenic Shock Working Group cohort, where higher age was associated with increased mortality in patients with CS across all SCAI stages, regardless of the aetiology of shock.[2] The most likely contributor to increased mortality with each decade of life is a higher burden of comorbidities. Outcomes in older adults may also be confounded by the types of therapy/interventions offered to patients at advanced age. Studies have shown that the older adult population is less likely to receive mechanical support during index hospitalisation for CS.[3] Meta-analysis of patients receiving Impella support showed higher rate of vascular complication and major bleeding with advanced age.[4] Similar findings have been seen in patients requiring venous-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, with an association between increasing age and mortality in this population.[5]

Various demographic and severity of illness predictors of mortality in patients with CS have previously been reported. Female sex and black or Hispanic race have both been shown to be associated with higher 30-day mortality post-CS.[6,7] The CardShock study found seven independent variables associated with CS mortality: AMI aetiology, age, previous MI, confusion, low left ventricular ejection fraction and increased blood lactate levels.[8] Similarly, complete lactate clearance and percentage lactate clearance have been associated with in-hospital survival.[9] The SCAI stages of CS provide a comprehensive severity of illness assessment for patients presenting in shock, and increasing SCAI stage is associated with worse in-hospital outcomes.[1,10] While it is well validated, it relies on physical examination, laboratory data and haemodynamic variables and, hence, may not be readily applicable as a ‘first look’ assessment.

The strength of our analysis is its large sample size, as well as broad applicability given inclusion of all patients with CS. Its true value is in providing patients, their caregivers and bedside clinicians with a rapid method for prognostication at the initial encounter. A lack of multivariable modelling is a limitation of our analysis, but it also makes our findings more generalisable. In due course, the precise risk of mortality for any given patient can be estimated by other, more comprehensive scores.

References

- 1.Jentzer JC, van Diepen S, Barsness GW et al. Cardiogenic shock classification to predict mortality in the cardiac intensive care unit. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:2117–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanwar M, Thayer KL, Garan AR et al. Impact of age on outcomes in patients with cardiogenic shock. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:688098. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.688098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratcovich HL, Josiassen J, Helgestad OKL et al. Outcome in elderly patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Shock. 2022;57:327–35. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iannaccone M, Albani S, Giannini F et al. Short term outcomes of Impella in cardiogenic shock: a review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Cardiol. 2021;324:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung M, Zhao Y, Strom JB et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use in cardiogenic shock: impact of age on in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and costs. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:e214–21. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloom JE, Andrew E, Nehme Z et al. Gender disparities in cardiogenic shock treatment and outcomes. Am J Cardiol. 2022;177:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2022.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ya’qoub L, Lemor A, Dabbagh M et al. Racial, ethnic, and sex disparities in patients with STEMI and cardiogenic shock. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:653–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harjola VP, Lassus J, Sionis A et al. Clinical picture and risk prediction of short-term mortality in cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:501–9. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marbach JA, Di Santo P, Kapur NK et al. Lactate clearance as a surrogate for mortality in cardiogenic shock: insights from the DOREMI trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e023322. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.023322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawler PR, Berg DD, Park JG et al. The Range of cardiogenic shock survival by clinical stage: data from the critical care cardiology trials network registry. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:1293–302. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]