Abstract

Gliomas are the most common type of malignant brain tumors, with glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) having a median survival of 15 months due to drug resistance and relapse. The treatment of gliomas relies on surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Only 12 anti-brain tumor chemotherapies (AntiBCs), mostly alkylating agents, have been approved so far. Glioma subtype–specific metabolic models were reconstructed to simulate metabolite exchanges, in silico knockouts and the prediction of drug and drug combinations for all three subtypes. The simulations were confronted with literature, high-throughput screenings (HTSs), xenograft and clinical trial data to validate the workflow and further prioritize the drug candidates. The three subtype models accurately displayed different degrees of dependencies toward glutamine and glutamate. Furthermore, 33 single drugs, mainly antimetabolites and TXNRD1-inhibitors, as well as 17 drug combinations were predicted as potential candidates for gliomas. Half of these drug candidates have been previously tested in HTSs. Half of the tested drug candidates reduce proliferation in cell lines and two-thirds in xenografts. Most combinations were predicted to be efficient for all three glioma types. However, eflornithine/rifamycin and cannabidiol/adapalene were predicted specifically for GBM and low-grade glioma, respectively. Most drug candidates had comparable efficiency in preclinical tests, cerebrospinal fluid bioavailability and mode-of-action to AntiBCs. However, fotemustine and valganciclovir alone and eflornithine and celecoxib in combination with AntiBCs improved the survival compared to AntiBCs in two-arms, phase I/II and higher glioma clinical trials. Our work highlights the potential of metabolic modeling in advancing glioma drug discovery, which accurately predicted metabolic vulnerabilities, repurposable drugs and combinations for the glioma subtypes.

Keywords: glioma, metabolic modeling, drug repurposing, cancer

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

Gliomas account for 50% of the deaths in cases with primary malignant brain and central nervous system (CNS) tumors in the United States [1]. The 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) CNS classification [2] stratifies adult gliomas into three subtypes based on the mutation status of the isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2 (IDH1/2) and the co-deletion of the short arm of chromosome 1 (1p) and the long arm of chromosome 19 (19q) (1p/19q co-deletion) into: astrocytoma (AST), IDH-mutant; oligodendroglioma (ODG), IDH-mutant and 1p/19q-codeletion ; and glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype (glioblastoma multiforme; GBM). GBM shows poor 7% 5-year survival that also limits the success rate of clinical trials, compared to 32%–53% in AST and 66%–84% in ODG [1].

The standard of care for GBM treatment is surgery, and radiotherapy, followed mainly by temozolomide (TMZ) chemotherapy [3]. Current approved anti-brain chemotherapies (AntiBCs) consist of eight monotherapies (cell cycle inhibitors and anti-hypoxic agents) and two combinations: procarbazine/lomustine/vincristine (PCV) and dabrafenib/trametinib [4]. The monotherapy AntiBCs targeting the cell cycle are mostly alkylating agents (TMZ, lomustine, carmustine and cyclophosphamide) and only doxorubicin targets topoisomerase; meanwhile, three anti-hypoxic agents reduce angiogenesis by targeting the mTOR/HIF-1α/VEGF pathway: everolimus (mTOR), belzutifan (HIF-1α) and bevacizumab (VEGF). The recently approved dabrafenib/trametinib combination for BRAF-mutant low-grade glioma (LGG) is the only targeted ABC inhibiting the RAF/MEK pathway. Whether targeting the RAF/MEK by dabrafenib/trametinib or the cell cycle by PCV combination, both combinations show redundancy of the target pathways, which is another potential cause for inefficacy of positive phase II drugs in phase III GBM trials [5]. Despite these treatments, glioma patient survival stays poor, with a high recurrence rate. The need for efficacious drugs and combinations targeting alternative pathways is therefore pivotal.

Drug repurposing, i.e. redirecting approved drugs to other diseases, has been proven as a critical element to shorten the lengthy toxicity trials in cancer drug discovery. However, current preclinical drug repurposing approaches in glioma have been mainly limited to GBM [6, 7], with a high failure rate in clinical trials due to non-efficacy, poor cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) bioavailability, drug resistance and toxicity [3]. While the exact biological role of 1p/19 co-deletion is still unclear, IDH mutation in most LGG dysregulates the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) balance and glutamate biosynthesis, depleting the glutathione, activating oxidative metabolism and increasing the reactive oxygen species (ROS) sensitivity [6].

The role of metabolic rewiring in IDH-mutant glioma encouraged the use of metabolic modeling for the study of gliomas, notably AST and ODG. Metabolic modeling is commonly applied to model the metabolism of cancer cells and to select among all FDA-approved drugs, the ones that target specifically cancer vulnerabilities appearing from metabolic rewiring [8]. Whole-brain and brain cell models were reconstructed to study alterations in the metabolism in neurodegenerative disease and GBM. These published genome-scale brain metabolic models were extensively covered in our previous review [9]. In the present study, we reconstructed three glioma subtype models using patient data from the TCGA, predicted drug and drug combinations, as well as the predicted essential genes in the different subtypes. Extensive literature review and comparison against high-throughput screenings (HTSs), especially against AntiBCs, allowed confirming the model’s prediction and further prioritizing the drug candidates.

Importance of the study

Due to high relapse and drug resistance rates, the three glioma subtypes suffer from poor survival rate, calling for new therapies. We present genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) of the three well-defined glioma subtypes that predicted repurposable FDA-approved single drugs and combinations for gliomas. We confirmed our predicted drugs using published in vitro and xenograft drug screenings and found that antimetabolites and TXNRD1-inhibitors induced a growth reduction comparable to AntiBCs in vitro and in xenografts. Furthermore, fotemustine showed a higher effectiveness in GBM clinical trials than AntiBCs. Additionally, we predicted 17 drug combinations mostly to be efficient on all three subtypes, with eflornithine/rifamycin and cannabidiol/adapalene being GBM- and LGG-specific, which is coherent with the known LGG-specific glutamate and glutathione depletion. This work presents the first GEMs that go beyond glioblastoma into the glioma subtypes, accurately capture the intra-heterogeneity and further predict repurposable combinations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Model building

Two types of models were built using rFASTCORMICS [10]: sample models to assess the subtype intra- and inter-heterogeneity and consensus models for the three glioma subtypes used for essential gene and drug prediction (see Supplementary Methods for more details). rFASTCORMICS was thereby fed with RNA-Seq data (116 GBM samples and 257 LGG samples) from The Cancer Genome Atlas Program (TCGA) data [11], stratified based on the 2021 WHO CNS classification [2], with the generic model Recon3D [12] as input reconstruction and the composition of CSF [13] as medium constraint. Other models and data formats were tested, but this setting allowed better separation between the sample models of the three glioma subtypes (Supplementary Methods, Figures S1–S4 and Table S1), matching to literature-retrieved metabolic exchanges (Figure S5) and balanced capturing of common essential genes (Figure S6). To confirm the models’ predictions in terms of metabolite exchanges, essential gene and drug predictions were compared with literature and databases, notably DepMap [14].

Prediction of metabolite exchanges

Different uptake and release reactions in the glioma subtype models allowed for assessing the model quality by comparing the exchange reactions with literature evidence. The minimum and maximum fluxes for the input and output reactions of the three consensus subtype models were computed using the fluxVariability function of the COBRA Toolbox v.3.0 [15] while maximizing for biomass production (biomass reaction). Narrow-bounded exchange reactions were selected as any perturbation is predicted to alter the cell growth of the models.

Prediction of essential genes

Single gene deletion from the COBRA Toolbox v.3.0 [15] was used with biomass optimization to predict essential genes. Only genes whose knockout (KO) is predicted to reduce the growth by at least 50% were selected and compared to a list of common essential genes (defined by the Cancer Dependency Map, DepMap, as genes found to be essential in >90% of cell lines in pan-cancer CRISPR-Cas9 screens), retrieved from DepMap 22Q1 [14].

Prediction of anti-glioma drugs and drug combinations

To predict potential single drugs and drug combinations, the drug deletion pipeline [16] was run and hence every target of the FDA-approved drugs and drug combinations was knocked out to assess the predicted effect on cell growth. Single drugs were restricted to FDA-approved drugs (2387 drugs defined by Drug Repurposing Hub [17]) due to the high failure rate in glioma clinical trials of preclinical compounds. For the drug combinations, AntiBCs and investigational anti-glioma drugs (IAGs) were tested in concert with FDA-approved drugs. Only single drugs and combinations that reduced the growth by at least 50% were considered for further analysis. Single drugs predicted to shut down the biomass production completely were not further tested in combination with other drugs. The drug targets were retrieved from DrugBank [18], PROMISCUOUS2 [19] and Drug Repurposing Hub [17]. Information on the IAGs (41 drugs) was gathered from the orpha.net database (ORPHA:182067), and AntiBCs (12 drugs) were retrieved from a review [4] and the NIH website (https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/brain).

Drug prioritization and benchmarking

Different clinical, xenograft, in vitro and pharmacokinetics (PK) data in brain cancer were collected to rank the predicted drugs based on their efficacy (see Supplementary Methods for details) and classify them into effective, ineffective and untested. Most compiled clinical trial data were on phase I/II or higher clinical trials in brain cancer (n = 50) and two-arm trials in glioma (n = 8). Two metrics were considered: overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS, duration between treatment and symptom worsening). The xenograft data included in/ex vivo drug HTSs in GBM patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) and in vivo drug screening from literature. In vitro data combined two cellular metrics: IC50 and viability reduction, and hence, a median IC50 across brain cancer cell lines was calculated for each drug as a potency measure. If available, PK data corresponding to CSF bioavailability was prioritized over blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability as the latter cannot capture the efflux rates of the brain. Single drugs that induced proliferation in vitro or cofactors to the target genes were excluded from further ranking. CSF bioavailability data were collected as LogBB (logarithm of the drug’s CSF-to-plasma concentration ratio).

RESULTS

Glioma sample models were reconstructed from TCGA-GBM and TCGA-LGG to assess if the metabolism of the 2021 WHO classification glioma subtypes was sufficiently different to be captured by qualitative metabolic models. The subtype models (iGBM, iAST, iODG) include between 32% and 35% of the reactions of the generic metabolic reconstruction Recon3D (Table 1), accurately detected metabolic variations between the IDH-mutant and -wildtype samples and allow for a clear separation between both types (Figure S3).

Table 1.

Summary of selected samples and model statistics for the consensus glioma subtype and control models

| Model | Selected samples | Reactions | Metabolites | ENTREZ Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| iAST | 116 | 3269 | 2460 | 1273 |

| iGBM | 140 | 3526 | 2621 | 1302 |

| iODG | 117 | 3331 | 2504 | 1305 |

| iCTRL | 4 | 3407 | 2585 | 1603 |

LGG and GBM models correctly predict high glutamate and thymidine uptake rates

Input and release rates of metabolites were predicted for the three consensus subtype models and compared to the literature (Table S2). Forty metabolites of the predicted 101 metabolite exchanges had narrow-bounded fluxes (with a maximum of 10% of the maximal range) and are predicted to affect cell growth directly. Four of them (Figure S7) matched known differences between the subtypes in cell line uptake, patient biomarkers and MR radiotracers (Figure 1, in cyan). High glutamate uptake was predicted in the LGG models (iAST and iODG), concordant with the known glutamate depletion due to IDH-mutant-induced rewiring [20]. iGBM predicted the highest thymidine uptake, in agreement with an elevated [18]F-FLT radiotracer uptake in GBM patients’ scans compared to AST [21] and ODG [22]. Finally, the reduced glutamine uptake in iODG conforms to the low ODG-specific glutamine dependency [23]. Together, predicted glutamate and thymidine uptake variations followed known IDH-based differences in the three subtypes. In one instance, the predicted lactate exchange is inconsistent with the literature [24] (Figure 1, in magenta). The lactate exchange inconsistency could be attributed to the inactivity of lactate exchange reactions during iGBM model building and their exclusion from the consistent subnetwork. Meanwhile, variations within the subtypes matching metabolomics data in L-phenylalanine and myo-inositol were considered minor validations (Figure 1, in gray). For the remaining exchanges, no data could be found in the literature. Notably, octadecenoate and pyruvate could serve as potential biomarkers between the glioma subtypes, but they still require validation (Figure S7). These experiments were repeated with 90% and 95% of maximation. However, the lowering of the threshold turned most exchanges to become unbounded, due to the high degree of freedom and hence could no longer capture the observations gathered from the literature. For example, glutamine exchange in iGBM was irreversible with 90% maximization, wide uptake range with 95% and high narrow-bounded with 100% maximization. 100% maximization of glutamine exchange in iGBM was the only setting matching high glutamine uptake in GBM (Figure S8).

Figure 1.

The predicted input and release rates of metabolites match the literature and experimental observations. Flux Variability Analysis allowed calculating flux ranges that guarantee an optimal growth and hence allowed finding critical metabolite exchanges (narrow-bounded fluxes). Forty out of 101 predicted exchanges were narrow-bounded, and four of the five exchange reactions matched literature and data from radiotracers for three subtypes (see Figure S7 for all reactions). Two exchange reactions matching metabolomics data were considered minor validation due to the unclear metabolic flux. Metabolite names on the y-axis with cyan, magenta and gray correspond to literature matching, contrary to literature and minor validation (Table S2), respectively.

Taking together, the metabolic models mostly captured not only metabolic variations between the subtypes but also recapitulated experimental observations.

Thioredoxin detoxification and nucleotide interconversion are potential targets for all three subtypes and arginine uptake for GBM

We further predicted vulnerabilities (essential genes) that could be exploited to reduce tumor progression. Twenty-five genes were predicted to be essential (Figure 2A) with 100% growth reduction (Figure S9). iODG yielded the highest number (n = 22), matching its known high survival rate and vulnerability [25]. Ten of these genes were identified as common essential genes by DepMap [14], suggesting pan-cancer vulnerabilities. A literature search further found five genes (TXNRD1, RRM1–2, SPLTC1, SLC27A4) to reduce viability with in vitro knockdown (KD) or KO. The KO of thioredoxin reductase (TXNRD1) reduced proliferation and migration in drug-resistant GBM [26]. Moreover, TXNRD1 expression significantly correlated with poorer diagnosis in AST [27] and ODG [28] patients. Due to their radical-scavenging activities, thioredoxin and glutathione (GSH) control oxidative homeostasis and counter mitochondrial oxidative stress. Similarly, KD of SPLTC genes involved in sphingolipid synthesis reduced the viability of GBM cell lines [29]. Likewise, the KD of RRM1 and RRM2, involved in nucleotide interconversion, caused cell death and sensitized GBM to TMZ, respectively (Table S3). However, one predicted essential gene: PYCT2, was described to increase GBM proliferation in a KD experiment [30].

Figure 2.

Thioredoxin detoxification and nucleotide interconversion are predicted as potential drug targets for glioma. (A) Twenty-five genes were predicted to reduce tumor growth in silico KO. Six of the 25 essential genes have been previously tested in in vitro KO or KD studies glioma (literature, Table S3), where five genes lowered proliferation (down arrows), and only one (PCYT2) increased proliferation (up arrows). Genes with no support in the literature are marked as dots. Moreover, 10 of the 25 predicted essential genes are common essentials (found essential genes in most cancer cell lines from CRISPR screens) and are marked as a big dot or arrow in (A). (B) Thirty-three FDA-approved drugs were predicted to reduce cell growth and could hence be repurposable for glioma. The 33 single drugs have 60 targets, of which 12 are essential genes (‘Essential drug targets’). Classifying the drugs based on approved indication and mode-of-action (MOA) (see color code of the font) showed that nearly a third are antimetabolites and fotemustine (with *) has both TXNRD1-inhibitor and alkylating MOA. For example, in (B), cladribine is marked as ‘C’ letter in gray box, while its approved indication and MOA is represented in red in the drug name color.

Besides the potential vulnerabilities, 33 FDA-approved drugs could, according to our models, be considered repurposable for glioma (Table S8). The 33 predicted drugs include 14 non-brain anti-cancer drugs (anticancers), 10 antivirals, 6 hormones/cofactors, 2 psychoactives and 1 lipid-lowering agent. The 14 anticancers are 10 antimetabolites, an ANPEP-inhibitor, 2 TXNRD1-inhibitors (such as fotemustine, also being an alkylating agent) and an alkylating agent. These drugs target 12 essential genes and 48 non-essential genes (Figure 2). Among them, TXNRD1 is targeted by arsenic trioxide and fotemustine (approved in some countries against melanoma brain metastasis [31]), and RRM1-2 by seven antimetabolites. RRM1-2 showed higher dependency probability (the likelihood that the KO of a gene reduces cell growth or induces cell death) than AntiBCs’ targets in the glioma cell lines (Figure S10). Furthermore, we predicted valganciclovir that affects arginine transporter SLC6A14 as a GBM-specific single drug.

The drug target genes differ among the three subtypes for the same drugs due to differences between the subtype models in gene and reaction compositions during model building. Some of the various targets of several drugs were included in some models and excluded in other based on the expression data. The glioma subtype model genes were compared to other brain metabolic models discussed in our previous review [9] using the Human Protein Atlas [32] brain-specific gene categories. The glioma subtype models showed comparable completeness and specificity to curated and semi-curated brain metabolic models (Figure S11).

Taken together, metabolic modelling accurately captured pan-glioma single vulnerabilities, such as thioredoxin detoxification and nucleotide interconversion. Additionally, metabolic modelling proposes arginine uptake as a druggable vulnerability for GBM.

Glutamate and polyamine biosynthesis are predicted suitable target pathways for drug combinations in LGG and GBM, respectively

FDA-approved drugs were tested in silico in combination with a set of 53 AntiBCs and IAGs to find meaningful synergistic drug combinations. Seventeen combinations (Figure 3A) composed of 19 drugs (hereafter will be referred to as combination drugs), including one anticancer antimetabolite (fluorouracil), antiviral antimetabolite (zidovudine), 13 carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAi) and two herbal antioxidants (cannabidiol and resveratrol) with multi-target actions (Table S4 and Tables S9–10). As every two drugs in the combinations have independent targets, Bliss combination index was selected to find synergistic, antagonistic and additive combinations [33] using growth reduction (1-grRatio, see Materials and Methods for details) as drug effect. Fifteen combinations with CAi were predicted to be synergistic in the three subtypes. CA converts CO2 to bicarbonate and is matching the known anti-glioma action of CAi by decreasing extracellular acidosis responsible for drug resistance. Besides CA, zonisamide and resveratrol target MAOA and MOAB genes, which convert oxygen and water into hydrogen peroxide, thereby increasing intracellular hypoxia, with MAOA inhibition found to decrease glioma proliferation and angiogenesis [34]. Two combinations displayed subtype-specific synergism (eflornithine/rifamycin for GBM and cannabidiol/adapalene for LGG), achieved 100% growth reduction their corresponding subtypes and did not affect ATP production and biomass maintenance in the healthy model iCTRL (Figure S12). Eflornithine (also known as α-difluoromethylornithine or DFMO) inhibits ornithine decarboxylase (ODC1), coding for an enzyme of the polyamine biosynthesis pathway, while rifamycin targets SLCO genes associated with GSH exchange reduction (Figure 3B). Meanwhile, adapalene inhibits glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 1 (GOT1) that governs glutamate biosynthesis from alpha-ketoglutarate, while cannabidiol increases ROS by depleting glutathione production. Both glutamate and GSH biosynthesis depletion align with the known LGG-specific vulnerabilities [20]. Among the combinations drug targets, ABCC1 and ABCG2 of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters predicted to remove the toxic byproducts of lipid peroxidation (4-hydroxy-2-nonenal) and heme biosynthesis (protoporphyrin), respectively. The predicted GBM-specific protoporphyrin is consistent with impaired heme biosynthesis in LGG cell line [35]. Similarly, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal was detected in GBM and AST samples affirming the predicted pan-glioma profile of the lipid peroxidation [36]. Altogether, metabolic modeling predicted combinations targeting alternative reactions for potential synergism, many of these reactions match known subtype-specific biosynthesis vulnerabilities. Of these combinations, the combined targeting of glutamate and GSH biosynthesis is a potentially druggable combination in LGG; meanwhile, targeting polyamine synthesis combined with GSH exchange is a potentially druggable combination in GBM.

Figure 3.

Eflornithine/rifamycin and cannabidiol/adapalene are predicted safe synergistic combinations for GBM and LGG, respectively. (A) Drug combination predictions were performed between two drug sets: (a) FDA-approved drugs after excluding predicted single drugs with a predicted lethal on the models and (b) approved AntiBCs and IAGs (marked with *). Combinations with growth reduction above 50% are depicted. All combinations, but two, reduce tumor growth across glioma subtypes (top two). (B) Analysis of the targets from the 17 synergistic combinations showed that dual KO of ODC1-SLCO (SLCO1A2, SLCO1B1, SLCO2A1 and SLCO2B1) genes are GBM-specific, while GOT1 and cannabidiol targets are LGG-specific. The drug names are colored based on the targeted pathway. Abbreviations: GSH, glutathione; biosyn, biosynthesis.

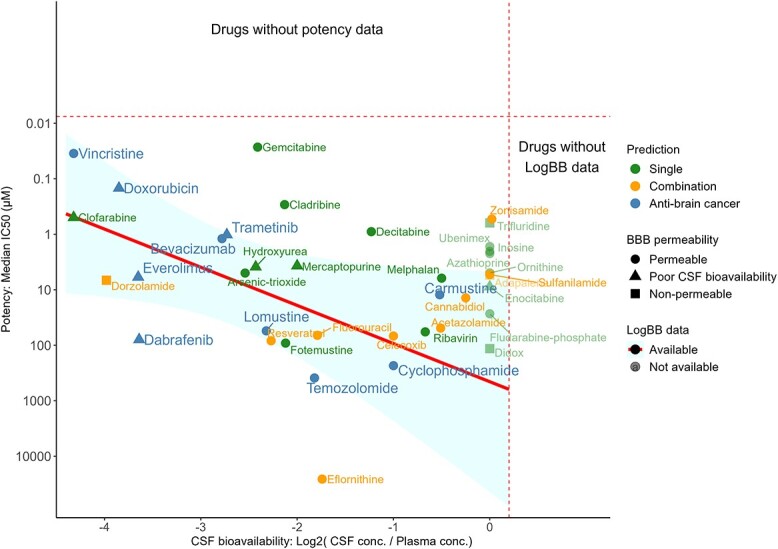

Gemcitabine, cladribine and decitabine have better CSF bioavailability and in vitro potency than AntiBCs

To select the most promising drugs and drug combinations, we ranked the drugs from HTS and literature data using IC50, viability reduction, BBB permeability, CSF bioavailability, ABC transporter affinity, in/ex vivo xenograft testing, main MOA, phase I/II clinical trials or higher and possible drug–drug interactions, aggregated from HTS and the literature (Supplementary File 2, Tables S8–S16, Supplementary Methods on data gathering and drug ranking and Table S5 for the screening databases). Ten single drugs were excluded for being cofactors to the target genes or induced proliferation in vitro (Table S8). As expected, the CSF bioavailability of AntiBCs is inversely correlated with potency (Figure 4 and Figure S13). Many single drugs, such as fotemustine, arsenic trioxide and hydroxyurea, showed comparable balanced outcomes to AntiBCs. In contrast, three antimetabolites (decitabine, gemcitabine and cladribine) achieved good potency and bioavailability. These three antimetabolites, especially gemcitabine, notably reduced cell viability compared to most AntiBCs (Figure S14). Some drugs showing high potency, such as clofarabine (predicted) and doxorubicin (AntiBC), however, had poor bioavailability. Taken together, most drug candidates achieved comparable results (TXNRD1-inhibitors) or outperformed (antimetabolites) AntiBCs drugs in terms of potency and bioavailability.

Figure 4.

Gemcitabine, cladribine and decitabine showed stronger in vitro potency and CSF bioavailability than AntiBCs. Potency (y-axis) and CSF bioavailability (x-axis) data were collected from the literature and screening databases (see Figure S13 for detailed potency per database). Potency (median IC50 across the brain cancer cell lines) was calculated for single and combination drugs and the AntiBCs. Similarly, CSF bioavailability was collected in LogBB, which is the logarithm of the CSF-to-plasma concentration ratio. Rightward on the x-axis and upward on the y-axis represent increasing potency and CSF bioavailability, respectively. Drugs without potency or LogBB data are on the top and right sides separated by the dashed lines, respectively.

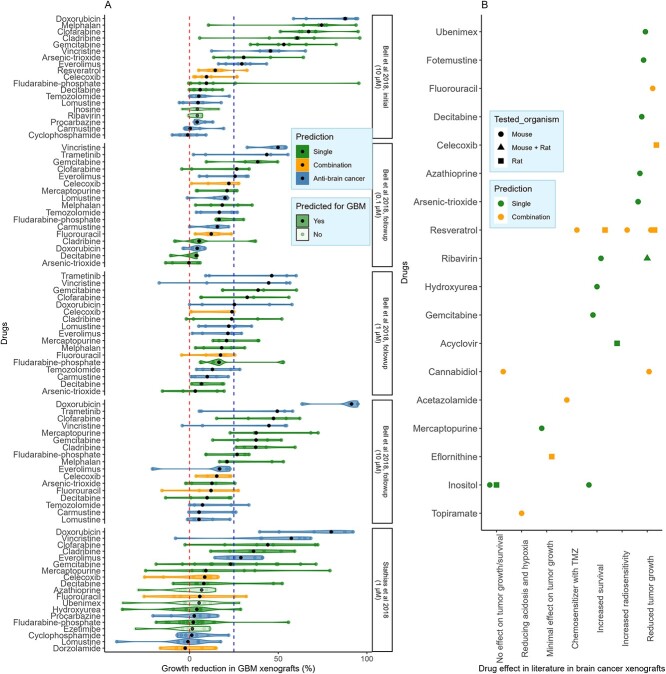

Cladribine and clofarabine reduced growth in GBM PDXs, while fotemustine reduced xenograft growth (data from literature)

Three drug HTS in GBM PDXs [37, 38] (Figure 5A) and PDXs data from the literature (Figure 5B and Table S12) were used to test the drugs in biological contexts closer to in vivo. Four non-alkylating AntiBCs (vincristine, trametinib, everolimus and doxorubicin) (Figure 4) surpassed 25% PDXs growth reduction. Correspondingly, three antimetabolites (gemcitabine, cladribine and clofarabine) induced a growth reduction comparable to or higher than these four AntiBCs. However, decitabine showed non-conclusive results between the drug screenings and the literature (Table S12). Fotemustine, which was not tested in HTS PDXs experiments, reduced growth in vivo in literature [39]. However, several drugs that showed low growth reductions in the GBM PDXs were predicted only by the LGG subtypes consensus models. Four combination drugs (fluorouracil, celecoxib, resveratrol and acetazolamide) (Tables S12 and S13) sensitized glioma to TMZ in vitro and in vivo. Of these, celecoxib caused a moderate in vivo growth reduction (with a median of 9%–22%). In summary, the three antimetabolites presented steady in vitro potency and in vivo growth reduction, and clofarabine outperformed two-thirds of the AntiBCs in PDXs.

Figure 5.

Clofarabine has a more robust growth reduction than two-thirds of the AntiBCs in GBM PDXs. Xenograft data were collected from HTS tested in GBM PDXs (A) and literature tested in brain cancer generally (B). Clofarabine, gemcitabine and cladribine attained a more robust or comparable growth reduction than half of the AntiBCs in the HTS. Additionally, some drugs not predicted by iGBM (in light green) showed moderate growth reduction in the GBM PDXs.

Fotemustine alone and eflornithine, celecoxib and valganciclovir in combination improved median OS compared to AntiBCs in phase II glioma trials, while antimetabolites showed no improvement

Drugs were classified into effective, ineffective and untested for in vitro and xenografts using the criteria in Table S6. All single and combination drugs except rifamycin were tested in vitro, while only half were tested in xenografts. Of the tested drugs, half and two-thirds were found effective in in vitro and xenografts, respectively (Figure 6A). Among the two-arm, phase I/II trials (Table S11), two single drugs (fotemustine and valganciclovir) and two combination drugs (eflornithine and celecoxib) improved the primary survival outcome compared to the ABC arm (Figure 6B). On the other hand, three predicted single drugs show no or minimal activity as monotherapy in single-arm, phase II trials: gemcitabine [40] (AST and GBM), cladribine [41] (AST and ODG) and melphalan [42] (AST and GBM). Additionally, when combined with carmustine, mercaptopurine and fluorouracil showed an antagonistic [43] and a non-additional [44] effect, respectively. The five drugs which failed in phase II trials are either substrate or inducer to the ABC transporters (Table S15), which might cause drug resistance, and all are cell cycle inhibitors.

Figure 6.

Among the tested predicted drugs, half and two-thirds were effective in vitro and xenografts, respectively, with four drugs showing comparable survival to AntiBCs in two-arm, phase I\II clinical trials. (A) Predicted single and combination drugs were classified into effective, ineffective and untested against AntiBCs using the criteria in Table S5. (B) Two-arm, phase II clinical trials in gliomas were selected to compare the predicted drugs to the ABC arm as monotherapy or in combination. Among the single drugs, fotemustine monotherapy and valganciclovir in combination improved median OS. Likewise, eflornithine and celecoxib improved mOS and median PFS, respectively. Only valganciclovir achieved statistical significance versus the ABC arm. On the other hand, two antimetabolites (gemcitabine and cladribine) and melphalan failed in single-arm trials with no reported survival, while mercaptopurine and fluorouracil reduced and kept mOS when combined with carmustine, respectively. Statistical significance of the predicted drug arm versus the AntiBCs arm was reported independently for each trial. Abbreviations: rGBM: recurrent GBM, nGBM: newly diagnosed GBM, rLGG: recurrent LGG, TMZ: temozolomide, SOC: standard-of-care, PCV: Procarbazine/lomustine/vincristine combination.

Beyond cell cycle inhibitors, of the four clinically effective drugs (fotemustine, valganciclovir, eflornithine and celecoxib), only valganciclovir reached statistical significance in the primary outcome in newly diagnosed GBM (nGBM) [45] and recurrent GBM (rGBM) [46, 47]. After the first-line treatment of TMZ and radiotherapy, fotemustine monotherapy slightly exceeded bevacizumab by 1.3 months achieving 8.7 months median OS (mOS) in a phase II trial in rGBM [48]. Eflornithine added to the PCV combination improved the mOS in recurrent LGG with about two and a half years against the PCV combination alone [49]. To a lesser extent, celecoxib combined with TMZ increased median PFS by 3 months in nGBM versus TMZ alone [50] and is the only known ABC transporter inhibitor of the four clinically effective drugs. While none of the 17 predicted combinations had been tested in brain cancer, three combinations (fluorouracil/zidovudine, fluorouracil/celecoxib and fluorouracil/resveratrol) were found synergistic in non-brain cancer in vitro; however, the last two failed as a combination in various clinical trials (Table S7). Eflornithine/rifamycin and cannabidiol/adapalene were ranked first and second for GBM- and LGG-specific subtypes, respectively. Despite the clinical activity of celecoxib in GBM, fluorouracil/celecoxib was ranked fourth due to predicted major drug–drug interaction (DDI) by DrugBank (Table S16) and the absence of an additional effect of the combination in phase III colon cancer trial [51]. Meanwhile, zonisamide showed the strongest in vitro potency among the combination drugs, and the fluorouracil/zonisamide was predicted with minor DDI of increased arrhythmia; hence, this combination was ranked third. All in all, metabolic modeling predicted drug candidates with a steady effective-to-ineffective ratio in in vitro (49%), in xenografts (64%) and in clinical trials (44%). Unlike the redundancy of the AntiBCs combinations’ target pathways, predicted combinations covered multiple alternative pathways, increasing potential synergism, of which three combinations were tested in non-brain cancer.

DISCUSSION

We have built GEMs (iGBM, iAST and iODG) for the three glioma subtypes based on the 2021 WHO classification and have predicted new repurposable, single drugs and combinations. While the sensitivity of essential gene predictions of the metabolic models remains low, the specificity is high [52, 53]. The low sensitivity is often attributed to the fact that in silico single gene KOs only capture essentiality related to metabolism and most specifically to the optimization function and fail capturing essentiality to other processes such as regulatory processes. The large efforts invested in the curation and standardization of genome-scale metabolic reconstruction, notably MEMOTE [54] and MetaNetX [55] as well as the benchmarking of context-specific model algorithms [56–58], and the curation of GPR rules [59] and improvement of biomass formulation [53] are likely to further improve the accuracy of the predictions [52, 60]. Furthermore, unlike some other computational drug repurposing approaches, metabolic modeling allowed understanding the effect of a KD or KO on a system level and confronting it to the earlier knowledge. Various sanity checks allowed for biologically relevant predictions that included: model selection based on subtype separation, matching metabolic exchanges and gene KD/KO with literature and evaluation against AntiBCs in vitro, in xenografts and in clinical trials. While model-building used the rFASTCORMICS algorithm [10], a member of the FASTCORE family that were benchmarked by us and others in various studies [57, 58], data collected of gene KD/KO and metabolic exchanges were kept only for validations as recommended in this review [61]. The models recapitulated metabolite exchanges and subtype-specific uptake for radiotracers in patients and medium metabolites measured in vitro. Similarly, IDH-mutant models (iAST and iODG) accurately predicted vulnerabilities consistent with the known 2HG-induced NADPH depletion, such as targeting glutamate and GSH biosynthesis [20] with the cannabidiol/adapalene combination, which would aggravate the depletion.

Cell cycle and hypoxia are the two common target pathways for glioma chemotherapy, with both AntiBCs combinations targeting redundant pathways diminishing a potential synergism. However, cell cycle inhibitors are ABC transporter substrates and hence are transporting the drugs out of the tumor causing drug resistance [62, 63] (Figure 7). Meanwhile all anti-hypoxic AntiBCs, except belzutifan, are ABC transporter inhibitors. Despite poor CSF bioavailability, only non-alkylating AntiBCs surpassed 25% growth reduction in xenograft experiments at 10 μM or lower, which is coherent with the mediocre performance in improving the OS in glioma patients. The subtype models allowed predicting single drugs and drug combinations that could enlarge the panel of therapeutic options in glioma. The single drug candidates predicted in this study principally target oxidative stress through the KD of TXNRD1, and arginine uptake and nucleotide interconversion (antimetabolites).

Figure 7.

Predicted drugs target the same genes as the AntiBCs or downstream genes, mainly covering four biological pathways: hypoxia, oxidative stress, cell cycle and polyamine biosynthesis. AntiBCs mainly affect hypoxia and cell cycle via growth factors and unselective alkylation, respectively. Meanwhile, the predicted CAis and antimetabolites selectively target DNA biosynthesis and CA, respectively. The transcription factor NRF2, a target of AntiBCs, regulates a third of predicted targets in the oxidative stress pathway (in olive green) [64–66]. Furthermore, predicted drugs and AntiBCs share common targets such as glutathione reductase (GSR) between cannabidiol and carmustine, monoamine oxidase A/B (MAO-A/B) are common between procarbazine, zonisamide and resveratrol and SLC22A6/8 between dabrafenib and zidovudine. Most predicted drugs and cell cycle inhibitor AntiBCs that were shown to be clinically inefficient are ABC transporter substrates, while clinically effective predicted drugs are either non-substrate (eflornithine), inhibitor (celecoxib) or have an unknown effect (fotemustine and valganciclovir) on ABC transporter. Unlike clinically ineffective antimetabolites (cladribine, gemcitabine, mercaptopurine and fluorouracil), fotemustine targets both cell cycle and TXNRD1. Meanwhile, polyamine synthesis is targeted uniquely by the clinically effective drugs predicted for GBM (valganciclovir and eflornithine), the phase I/II ADPI-PEG20 IAG. Furthermore, cannabidiol, rifamycin, celecoxib and others inhibit the ABC transporters (ABCC1 and ABCG2) responsible for AntiBCs resistance as well as byproducts detoxification such as the efflux of lipid peroxidation (4-hydroxy-2-nonenal) and heme biosynthesis (protoporphyrin) byproducts. 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal and protoporphyrin predicted for pan-glioma and GBM, respectively, matching the literature in the predicted subtypes. Abbreviations: GSH: reduced glutathione, GSSG: oxidized glutathione, TXN: thioredoxin, αKG: alpha-ketoglutarate.

TXNRD1 is predicted to be a vulnerability present across all glioma subtypes, and its expression was shown to highly correlate to AST [27] and ODG [28] patients’ survival. Moreover, fotemustine (TXNRD1-inhibitor and alkylating agent) monotherapy displayed comparable survival to bevacizumab in a two-arm, phase II clinical trial in rGBM [48]. In a network meta-analysis of 11 AntiBCs and IAGs in rGBM, fotemustine ranked best in effectiveness as mOS [67]. Another TXNRD1-inhibitor, arsenic trioxide, was tested as local interstitial monotherapy in a single-arm, phase I/II GBM trial with the first promising results [68], outperformed alkylating AntiBCs in vivo and in vitro and an ABC transporter inhibitor.

The antiviral valganciclovir, one of our drug candidates, is predicted to target arginine uptake in GBM. In vitro, arginine deprivation reduced GBM invasiveness [69] and currently, the arginine-degrading agent, ADI-PEG20, has been tested in a phase I GBM trial (NCT04587830) [70]. While valganciclovir significantly enhanced mOS when combined with the AntiBCs in both nGBM and rGBM phase II trials, its hypothetical cytotoxic link to arginine uptake inhibition has yet to be proven.

While antimetabolites have been successful in cancer treatment and despite the high in vitro potency and viability reduction, four antimetabolites (cladribine, gemcitabine and mercaptopurine from the single drugs and fluorouracil from the combinations drugs) failed in phase II glioma trials. Another predicted antimetabolite, clofarabine, showed in vivo growth reduction, but has not been tested clinically. While BBB permeability and CSF bioavailability infer drug penetrance, ABC transporter affinity was found to be more crucial for drug diffusion into core tumor regions, even under leaky BBB [71]. Similarly, ABC transporter substrates are more likely to possess low serum concentration due to drug metabolism. Both clinically ineffective predicted drugs and cell cycle inhibitors AntiBCs are ABC transporter substrates, which might explain their inefficacy to due to limited drug distribution to the core tumor [71]. Finally, despite having the highest potency, CSF bioavailability and ABC transporter inhibitor affinity, decitabine presented moderate in vitro viability and weak xenograft growth reduction. Nevertheless, decitabine prodrugs are currently in two phase II trials for IDH-mutant glioma (NCT03666559 and NCT03922555). Overall, predicted single drugs implicated in oxidative stress and polyamine metabolism pathways are more target-specific than AntiBCs’ transcription factors, of which fotemustine, arsenic trioxide and valganciclovir represent repurposable single drugs for glioma with a clinical profile comparable to AntiBCs.

We further searched for drugs that could increase the potency of AntiBCs and IAGs to predict drug combinations that allow targeting pathways characterized by many isozymes and alternative reactions that must be inhibited simultaneously, avoiding pathway redundancy of the AntiBCs combinations. The predicted drug combinations allowed targeting CA, GSH exchange, glutamate, polyamine and GSH biosynthesis. In addition to inhibiting ABC transporters, anti-hypoxic AntiBCs reduce angiogenesis through mTOR/HIF-1α/VEGF or RAF/MEK pathways, while anti-hypoxic combination drugs target their downstream CA and MAO-A/B genes. The relatively high potency and xenograft growth reduction of anti-hypoxic AntiBCs compared to alkylating AntiBCs is clinically consistent with the superior median overall response rate of anti-angiogenic agents compared to alkylating agents (6.1%) in rGBM phase II trials [72]. CA2, CA9 and CA12 are highly expressed in GBM, especially CA9, which is not expressed in a healthy brain [73] and is significantly correlated with poor survival in GBM [73] and the AST grade [74]. The proposed 17 drug combinations include pairs of a total of 19 drugs. In brain cancer, 18 out of 19 combinations drugs (except rifamycin) have been tested individually. However, none of the 17 proposed combinations has been assessed in vivo or in vitro for brain cancer, which warrants their testing. Even though three combinations had synergistic effects in vitro in non-brain cancer, two failed in clinical trials. Among the 17 predicted combinations, three IAGs: cannabidiol, eflornithine and fluorouracil, were predicted to have a synergistic effect with adapalene (GOT1-inhibitor), rifamycin (SLCO-inhibitor) and zonisamide (CAi), respectively. With cannabidiol and rifamycin being ABC transporter inhibitors, cannabidiol/adapalene and eflornithine/rifamycin combinations present potential combinations for relapsed glioma from AntiBCs resistance. Additionally, iGBM accurately predicted ABCG2 transporter responsible for efflux activity against protoporphyrin, as GBM-specific vulnerability, matching the impaired heme biosynthesis in IDH-mutant glioma [29]. Among the 19 combination drugs, zonisamide (selective CA9-inhibitor, approved for seizures) had the highest potency and CSF bioavailability and target additionally MAOA/B increasing its anti-hypoxic action like procarbazine. While adapalene has poor CSF bioavailability, the recent nanoparticle formulation of adapalene increased its CSF bioavailability [75]. Similarly, the lack of survival of eflornithine monotherapy in GBM but not AST in a phase II clinical trial [49] highlights the importance of testing the eflornithine/rifamycin combination in GBM.

Some of the shared genes between Recon3D reconstruction and DepMap’s common essential genes are enriched for other functions unrelated to growth (Table S17). As the formulation of the biomass was shown to impact essential gene predictions [53], a tailored biomass formulation should improve accuracy. Besides curating the biomass growth formulation and updating GPR rules, disease- specific reactions could be added before model building to improve essentiality analysis and drug prediction [53]. For example, adding IDH-mutant biochemical reactions would allow more accurate modeling of the LGG. Similarly, formulating evaluation tests of predicted essential genes on the DepMap scores would allow reproducible predictions and evaluations between studies. Moreover, Flux Variability Analysis of metabolic exchanges could be improved using random sampling, especially for reactions with a wide flux range [76]. While the iCTRL model was built from four healthy brain samples from TCGA-GBM, building a healthy brain model from the GTEx expression data [77] with CSF medium or using the brain model from the whole-body model [13] could advance evaluating the safety of the predicted drugs. In summary, metabolic modeling predicted combinations that overcome the target redundancy of the AntiBCs combinations with alternative, accurate glioma subtype–specific targets. The top two combinations present a safety profile and ABC substrate inhibition for one of the two drugs, with variations in subtype specificity that call for further testing.

CONCLUSION

GBM and LGG suffer from poor patient survival and accurate preclinical models, respectively, that hinder new therapies’ discovery. Moreover, AntiBCs lack either adequate potency or CSF bioavailability. In addition, two-thirds of AntiBCs are ABC transporter substrates, increasing their drug resistance and core tumor diffusion. In this work, we present glioma subtype–specific GEMs to predict single drugs and combinations that are promising candidates to be translated into clinical trials. Among others, LGG GEMs accurately predicted glutamate and GSH biosynthesis vulnerabilities, while GBM GEM accurately predicted glutamine dependency and heme biosynthesis. Unlike the target redundancy of the combination AntiBCs, predicted combinations target alternative reactions, potentiating their synergism. Of the predicted 33 single drugs (19 combinations drugs), half were effective in vitro, and 17 [8] were tested against GBM PDXs, of which 11 [5] were effective. Similarly, predicted drugs show comparable or improved CSF bioavailability to AntiBCs. Despite five cell cycle inhibitors failing in phase II glioma clinical trials due to conceivably being ABC transporter substrates, two single drugs (fotemustine and valganciclovir) and two combination drugs (eflornithine and celecoxib) exceeded the primary survival outcome alone or combined with AntiBCs in phase I/II clinical trials. Our work warrants fotemustine as pan-glioma monotherapy and eflornithine/rifamycin and cannabidiol/adapalene as promising new combinations for GBM and LGG, respectively.

Key Points

Glioma metabolic modeling accurately captured inter-subtype metabolic variations.

Fotemustine showed very good performance in a meta-analysis in OS.

Fotemustine alone and eflornithine in combination showed improved survival in glioma trials.

The prediction of glutamate depletion by adapalene in IDH-mutant glioma agrees with literature.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Simone P. Niclou and Sabrina Fritah for their feedback on the sample stratification. The experiments presented in this paper were carried out using the HPC facilities of the University of Luxembourg [78].

Author Biographies

Ali Kishk is a PhD graduate from the University of Luxembourg in Systems Biology. His research focuses on drug repurposing for cancer using metabolic modeling.

Maria Pires Pacheco specialises in metabolic modelling and especially the development of workflows for the integration of omics data in metabolic models.

Tony Heurtaux is Research Scientist at the Department of Life Sciences and Medicine (University of Luxembourg) and the Luxembourg Centre of Neuropathology. His research work is focused on molecular and cellular biology of glial cells.

Thomas Sauter is full professor at the Department of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Luxembourg. His research is focused on computational systems biology.

Contributor Information

Ali Kishk, Department of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Luxembourg, L-4367 Belvaux, Luxembourg.

Maria Pires Pacheco, Department of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Luxembourg, L-4367 Belvaux, Luxembourg.

Tony Heurtaux, Department of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Luxembourg, L-4367 Belvaux, Luxembourg; Luxembourg Centre of Neuropathology, L-3555 Dudelange, Luxembourg.

Thomas Sauter, Department of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Luxembourg, L-4367 Belvaux, Luxembourg.

FUNDING

This research was funded in part by the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR), grant reference [PRIDE21/16763386/CANBI02].

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization, A.K., M.P.P. and T.S.; Methodology, A.K. and M.P.P.; Formal Analysis, A.K.; Investigation, A.K., M.P.P. and T.S.; Resources, A.K.; Data Curation, A.K.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, A.K.; Writing—Review & Editing, A.K., M.P.P., T.H., T.S.; Visualization, A.K., M.P.P., T.H. and T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All analyzed data are publicly available from the Resources Table in Supplementary Table 1. Analysis code is available under https://github.com/sysbiolux/GliomaGEM/

References

- 1. Ostrom QT, Price M, Neff C, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2015–2019. Neuro-Oncology 2022;24:v1–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro-Oncology 2021;23(8):1231–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. King JL, Benhabbour SR. Glioblastoma multiforme—a look at the past and a glance at the future. Pharmaceutics 2021;13(7):1053–73. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13071053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sun J, Wei Q, Zhou Y, et al. A systematic analysis of FDA-approved anticancer drugs. BMC Syst Biol 2017;11(Suppl 5):87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mandel JJ, Yust-Katz S, Patel AJ, et al. Inability of positive phase II clinical trials of investigational treatments to subsequently predict positive phase III clinical trials in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2018;20(1):113–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Persico P, Lorenzi E, Losurdo A, et al. Precision oncology in lower-grade gliomas: promises and pitfalls of therapeutic strategies targeting IDH-mutations. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14(5):1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bjerkvig R, Bougnaud S, Niclou SP. Animal models for low-grade gliomas. In: Duffau H (ed). Diffuse Low-Grade Gliomas in Adults: Natural History, Interaction with the Brain, and New Individualized Therapeutic Strategies. Springer London, 2013, Vol. 9781447122135. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moškon M, Režen T. Context-specific genome-scale metabolic modelling and its application to the analysis of COVID-19 metabolic signatures. Metabolites 2023;13(1):126–53. 10.3390/METABO13010126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kishk A, Pacheco MP, Heurtaux T, et al. Review of current human genome-scale metabolic models for brain cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Cells 2022;11(16):2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pacheco MP, Bintener T, Ternes D, et al. Identifying and targeting cancer-specific metabolism with network-based drug target prediction. EBioMedicine 2019;43:98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rahman M, Jackson LK, Johnson WE, et al. Alternative preprocessing of RNA-sequencing data in the cancer genome atlas leads to improved analysis results. Bioinformatics 2015;31(22):3666–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brunk E, Sahoo S, Zielinski DC, et al. Recon3D enables a three-dimensional view of gene variation in human metabolism. Nat Biotechnol 2018;36(3):272–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thiele I, Sahoo S, Heinken A, et al. Personalized whole-body models integrate metabolism, physiology, and the gut microbiome. Mol Syst Biol 2020;16(5):e8982–e9005. 10.15252/msb.20198982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pacini C, Dempster JM, Boyle I, et al. Integrated cross-study datasets of genetic dependencies in cancer. Nat Commun 2021;12(1):1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heirendt L, Arreckx S, Pfau T, et al. Creation and analysis of biochemical constraint-based models using the COBRA toolbox v.3.0. Nat Protoc 2019;14(3):639–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bintener T, Pacheco MP, Kishk A, et al. Drug Target Prediction Using Context-Specific Metabolic Models Reconstructed from rFASTCORMICS. In: Baiocchi M (ed). Methods in Molecular Biology. US: Springer, 2022, Vol. 2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Corsello SM, Bittker JA, Liu Z, et al. The drug repurposing hub: a next-generation drug library and information resource. Nat Med 2017;23(4):405–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Guo AC, et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res 2018;46:D1074–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gallo K, Goede A, Eckert A, et al. PROMISCUOUS 2.0: a resource for drug-repositioning. Nucleic Acids Res 2020;49(D1):D1373–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McBrayer SK, Mayers JR, DiNatale GJ, et al. Transaminase inhibition by 2-Hydroxyglutarate impairs glutamate biosynthesis and redox homeostasis in glioma. Cell 2018;175(1):101–116.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jacobs AH, Thomas A, Kracht LW, et al. 18F-Fluoro-l-thymidine and 11C-Methylmethionine as markers of increased transport and proliferation in brain tumors. J Nucl Med 2005;46(12):1948–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nikaki A, Angelidis G, Efthimiadou R, et al. 18F-fluorothymidine PET imaging in gliomas: an update. Ann Nucl Med 2017;31(7):495–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chiu M, Taurino G, Bianchi MG, et al. Oligodendroglioma cells lack glutamine synthetase and are auxotrophic for glutamine, but do not depend on glutamine anaplerosis for growth. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19(4):1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chaumeil MM, Radoul M, Najac C, et al. Hyperpolarized 13C MR imaging detects no lactate production in mutant IDH1 gliomas: implications for diagnosis and response monitoring. Neuroimage Clin 2016;12:180–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Simeonova I, Huillard E. In vivo models of brain tumors: roles of genetically engineered mouse models in understanding tumor biology and use in preclinical studies. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014;71(20):4007–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pires V, Bramatti I, Aschner M, et al. Thioredoxin reductase inhibitors as potential antitumors: mercury compounds efficacy in glioma cells. Front Mol Biosci 2022;9:889971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Haapasalo H, Kyläniemi M, Paunu N, et al. Expression of antioxidant enzymes in astrocytic brain tumors. Brain Pathol 2003;13(2):155–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hannu H, Helena B, Niina P, et al. Antioxidant enzymes in oligodendroglial brain tumors: association with proliferation, apoptotic activity and survival. J Neuro-Oncol 2006;77(2):131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bernhart E, Damm S, Wintersperger A, et al. Interference with distinct steps of sphingolipid synthesis and signaling attenuates proliferation of U87MG glioma cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2015;96(2):119–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Osawa T, Shimamura T, Saito K, et al. Phosphoethanolamine accumulation protects cancer cells under glutamine starvation through downregulation of PCYT2. Cell Rep 2019;29(1):89–103.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garbe C. Ipilimumab with fotemustine in metastatic melanoma. Lancet Oncol 2012;13(9):851–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sjöstedt E, Zhong W, Fagerberg L, et al. An atlas of the protein-coding genes in the human, pig, and mouse brain. Science 2020;367(6482):1091–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Duarte D, Vale N. Evaluation of synergism in drug combinations and reference models for future orientations in oncology. Curr Res Pharmacol Drug Discov 2022;3:100110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kushal S, Wang W, Vaikari VP, et al. Monoamine oxidase A (MAO A) inhibitors decrease glioma progression. Oncotarget 2016;7(12):13842–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Traylor JI, Pernik MN, Sternisha AC, et al. Molecular and metabolic mechanisms underlying selective 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced fluorescence in gliomas. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(3):580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jaganjac M, Cindrić M, Jakovčević A, et al. Lipid peroxidation in brain tumors. Neurochem Int 2021;149:105118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stathias V, Jermakowicz AM, Maloof ME, et al. Drug and disease signature integration identifies synergistic combinations in glioblastoma. Nat Commun 2018 9:1 2018;9(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bell JB, Eckerdt F, Dhruv HD, et al. Differential response of glioma stem cells to arsenic trioxide therapy is regulated by MNK1 and mRNA translation. Mol Cancer Res 2018;16(1):32–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vassal G, Boland I, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, et al. Activity of fotemustine in medulloblastoma and malignant glioma xenografts in relation to O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase and alkylpurine-DNA N-glycosylase activity. Clin Cancer Res 1998;4(2):463–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gertler SZ, MacDonald D, Goodyear M, et al. NCIC-CTG phase II study of gemcitabine in patients with malignant glioma (IND.94). Ann Oncol 2000;11(3):315–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rajkumar SV, Burch PA, Nair S, et al. Phase II North Central Cancer Treatment Group study of 2- chlorodeoxyadenosine in patients with recurrent glioma. Am J Clin Oncol 1999;22(2):168–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chamberlain MC, Prados MD, Silver P, Levin VA. A phase II trial of oral melphalan in recurrent primary brain tumors. Am J Clin Oncol 1988;11(1):52–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Halperin EC, Herndon J, Schold SC, et al. A phase III randomized prospective trial of external beam radiotherapy, mitomycin C, carmustine, and 6-mercaptopurine for the treatment of adults with anaplastic glioma of the brain. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1996;34(4):793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shapiro WR, Green SB, Burger PC, et al. A randomized comparison of intra-arterial versus intravenous BCNU, with or without intravenous 5-fluorouracil, for newly diagnosed patients with malignant glioma. J Neurosurg 1992;76(5):772–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stragliotto G, Pantalone MR, Rahbar A, et al. Valganciclovir as add-on to standard therapy in glioblastoma patients. Clin Cancer Res 2020;26(15):4031–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pantalone MR, Rahbar A, Söderberg-Naucler C, Stragliotto G. Valganciclovir as add-on to second-line therapy in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14(8):1958–70. 10.3390/cancers14081958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Stragliotto G, Rahbar A, Solberg NW, et al. Effects of valganciclovir as an add-on therapy in patients with cytomegalovirus-positive glioblastoma: a randomized, double-blind, hypothesis-generating study. Int J Cancer 2013;133(5):1204–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brandes AA, Finocchiaro G, Zagonel V, et al. AVAREG: a phase II, randomized, noncomparative study of fotemustine or bevacizumab for patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2016;18(9):1304–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Levin VA, Ictech SE, Hess KR. Clinical importance of eflornithine (α-difluoromethylornithine) for the treatment of malignant gliomas. CNS Oncol 2018;7(2):CNS16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Penas-Prado M, Hess KR, Fisch MJ, et al. Randomized phase II adjuvant factorial study of dose-dense temozolomide alone and in combination with isotretinoin, celecoxib, and/or thalidomide for glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2015;17(2):266–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Meyerhardt JA, Shi Q, Fuchs CS, et al. Effect of celecoxib vs placebo added to standard adjuvant therapy on disease-free survival among patients with stage III colon cancer: the CALGB/SWOG 80702 (alliance) randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021;325(13):1277–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Strain B, Morrissey J, Antonakoudis A, Kontoravdi C. How reliable are Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell genome-scale metabolic models? Biotechnol Bioeng 2023;120(9):2460–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Moscardó García M, Pacheco M, Bintener T, et al. Importance of the biomass formulation for cancer metabolic modeling and drug prediction. iScience 2021;24(10):103110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lieven C, Beber ME, Olivier BG, et al. MEMOTE for standardized genome-scale metabolic model testing. Nat Biotechnol 2020;38(3):272–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Moretti S, Tran VDT, Mehl F, et al. MetaNetX/MNXref: unified namespace for metabolites and biochemical reactions in the context of metabolic models. Nucleic Acids Res 2021;49:D570–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Machado D, Herrgård M. Systematic evaluation of methods for integration of transcriptomic data into constraint-based models of metabolism. PLoS Comput Biol 2014;10(4):e1003580–91. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pacheco MP, Pfau T, Sauter T. Benchmarking procedures for high-throughput context specific reconstruction algorithms. Front Physiol 2016;6:410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vieira V, Ferreira J, Rocha M. A pipeline for the reconstruction and evaluation of context-specific human metabolic models at a large-scale. PLoS Comput Biol 2022;18(6):e1009294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Di FM, Damiani C, Pescini D. GPRuler: metabolic gene-protein-reaction rules automatic reconstruction. PLoS Comput Biol 2021;17(11):e1009550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bernstein DB, Akkas B, Price MN, Arkin AP. Evaluating E. Coli genome-scale metabolic model accuracy with high-throughput mutant fitness data. Mol Syst Biol 2023;19(12):11566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kaste JAM, Shachar-Hill Y. Model validation and selection in metabolic flux analysis and flux balance analysis. Biotechnol Prog 2024;40(1):e3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wijaya J, Fukuda Y, Schuetz JD. Obstacles to brain tumor therapy: key ABC transporters. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18(12):2544–78. 10.3390/ijms18122544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fukuda Y, Schuetz JD. ABC transporters and their role in nucleoside and nucleotide drug resistance. Biochem Pharmacol 2012;83(8):1073–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Heurtaux T, Bouvier DS, Benani A, et al. Normal and pathological NRF2 signalling in the central nervous system. Antioxidants 2022;11(8):1426–61. 10.3390/antiox11081426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Deblasi JM, Denicola GM. Dissecting the crosstalk between nrf2 signaling and metabolic processes in cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(10):3023–42. 10.3390/cancers12103023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dodson M, Castro-Portuguez R, Zhang DD. NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol 2019;23:101107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. McBain C, Lawrie TA, Rogozińska E, et al. Treatment options for progression or recurrence of glioblastoma: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;2021(12):CD013579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Han D, Teng L, Wang X, et al. Phase I/II trial of local interstitial chemotherapy with arsenic trioxide in patients with newly diagnosed glioma. Front Neurol 2022;13:1001829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Pavlyk I, Rzhepetskyy Y, Jagielski AK, et al. Arginine deprivation affects glioblastoma cell adhesion, invasiveness and actin cytoskeleton organization by impairment of β-actin arginylation. Amino Acids 2015;47(1):199–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bomalaski JS, Chen KT, Chuang MJ, et al. Phase IB trial of pegylated arginine deiminase (ADI-PEG 20) plus radiotherapy and temozolomide in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol 2022;40(16_suppl):2057. [Google Scholar]

- 71. de Gooijer MC, Kemper EM, Buil LCM, et al. ATP-binding cassette transporters restrict drug delivery and efficacy against brain tumors even when blood-brain barrier integrity is lost. Cell Rep Med 2021;2(1):100184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ellingson BM, Wen PY, Chang SM, et al. Objective response rate targets for recurrent glioblastoma clinical trials based on the historic association between objective response rate and median overall survival. Neuro-Oncology 2023;25(6):1017–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Proescholdt MA, Merrill MJ, Stoerr EM, et al. Function of carbonic anhydrase IX in glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro-Oncology 2012;14(11):1357–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yoo H, Sohn S, Nam BH, et al. The expressions of carbonic anhydrase 9 and vascular endothelial growth factor in astrocytic tumors predict a poor prognosis. Int J Mol Med 2010;26(1):3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Medina DX, Chung EP, Bowser R, Sirianni RW. Lipid and polymer blended polyester nanoparticles loaded with adapalene for activation of retinoid signaling in the CNS following intravenous administration. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2019;52:927–33. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Herrmann HA, Dyson BC, Vass L, et al. Flux sampling is a powerful tool to study metabolism under changing environmental conditions. NPJ Syst Biol Appl 2019;5(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lonsdale J, Thomas J, Salvatore M, et al. The genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet 2013;45(6):580–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Varrette S, Bouvry P, Cartiaux H, Georgatos F. Management of an academic HPC cluster: The UL experience. In: Smari W, Zeljkovic V (eds). Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on High Performance Computing and Simulation, HPCS 2014. New York City, US: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2014, 1001829. 10.1109/HPCSim.2014.6903792 [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All analyzed data are publicly available from the Resources Table in Supplementary Table 1. Analysis code is available under https://github.com/sysbiolux/GliomaGEM/