Abstract

Background

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a rare blood disorder, leading to various complications and impairments in patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Limited research has been conducted to evaluate the HRQOL of Chinese patients with PNH. Understanding the HRQOL in this specific population is crucial for providing effective healthcare interventions and improving patient’ health outcomes. This study aimed to assess HRQOL of Chinese patients with PNH, and identify key determinants.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted during 2022 to recruit patients with PNH in China. The study population was recruited from PNH China, one of the largest public welfare PNH patient mutual aid organization in China. Data were collected via an online questionnaire including the EQ-5D-5L (5L), and social-demographic and clinical characteristics. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize the characteristics of the participants and their HRQOL. Multiple linear and logistic regression analyses were adopted to explore key factors affecting HRQOL.

Results

A total of 329 valid questionnaires were collected. The mean (SD) age of the patients was 35.3 (10.0) years, with 52.3% of them being male. The patients reported more problems in Anxiety/Depression (81.5%) and Pain/Discomfort (69.9%) dimensions compared to the other three 5L dimensions. The mean (SD) of 5L health utility score (HUS) and EQ-VAS score were 0.76 (0.21) and 62.61 (19.20), respectively. According to multiple linear regression, initial symptoms (i.e., Anemia [fatigue, tachycardia, shortness of breath, headache] and back pain) and complication of thrombosis were significant influencing factors affecting 5L HUS. Total personal income of the past year, initial symptom of hemoglobinuria and complication of thrombosis were significantly influencing factors of VAS score. Social-demographic and clinical characteristics, such as gender, income, and thrombosis, were also found to be significantly related to certain 5L health problems as well.

Conclusion

Our study manifested the HRQOL of PNH patients in China was markedly compromised, especially in two mental-health related dimensions, and revealed several socio-demographic and clinical factors of their HRQOL. These findings could be used as empirical evidence for enhancing the HRQOL of PNH patients in China.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13023-024-03178-x.

Keywords: Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, Health-related quality of life (HRQOL), EQ-5D-5L, Influencing factors, China

Background

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is an acquired hematopoietic stem cell disorder, resulting from a somatic mutation in the X-linked gene phosphatidylinositol glycan class A (PIGA) which leads to the expansion of hematopoietic stem cell clones [1, 2]. PNH, an ultra-orphan disease due to its rarity, manifests as a chronic, multi-systemic, and progressive illness posing life-threatening risks, characterized by hemolytic anemia, hemoglobinuria, thrombotic events (TEs), severe infections, smooth muscle dystonia and bone marrow failure (BMF) [1–8]. The global prevalence of PNH is estimated to range between 10 and 20 cases per million [5]. Evidence also suggests that the worldwide incidence of PNH is estimated at 1-1.5 cases per million, with a potentially higher rate in certain regions [2, 9, 10]. For example, epidemiological data show that the disease occurs more frequently in Asia countries (e.g., Japan, Korea and China) than in western countries (e.g., US, UK, Spain) [9–11]. However, there is a lack of nationwide data in China, though one regional study in Mudanjiang region of Heilongjiang Province showed that the standardized incidence was 2.7 per 100,000 population [12].

PNH can affect individuals at any age group, showing no significant preferences towards gender, ethnicity, or geographical region. Nevertheless, it manifests most commonly in young adulthood, with the median diagnosis age in the early- to mid-thirties [5, 7, 11, 12]. Despite optimal supportive care, retrospective analyses report a substantial increase in mortality due to PNH, with 5-year and 10-year mortality rates estimated at 35% and approximately 50%, respectively [1, 5, 6].

PNH has an extensive adverse impact on various health aspects of patients. According to the International PNH Registry, PNH patients frequently experience symptoms of fatigue, headache, dyspnea, hemoglobinuria, abdominal pain, erectile dysfunction and dysphagia [13, 14]. Hence, it is essential to enhance or sustain the patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQOL), a multidimensional health outcome generally consisting of the physical, social and emotional aspects of health perception and functioning [15–17]. HRQOL information on patients with PNH could be valuable in facilitating healthcare, evaluating disease burden, and assessing the effectiveness/cost-effectiveness of health interventions (if utility instruments are adopted) for the patients.

Empirical evidence has suggested that PNH can significantly reduce HRQOL of the patients in western populations [13, 14, 18–22]. Given the disparities in medical systems, cultural background, and patient characteristics between China and western countries, the existing evidence may not be directly applicable to China. Hence, our aim was to comprehensively evaluate HRQOL of Chinese patients with PNH using the EQ-5D-5L (5L), a new version of the widely used EQ-5D, and to explore the influencing factors.

Methods

Aim

This study aimed to assess HRQOL of Chinese patients with PNH, and identify key determinants, supply objective and factual data to policymakers and researchers and call on the whole society to pay attention to PNH and implement favorable policies about rare disease.

Design and setting of the study

In 2022, a cross-sectional survey was conducted in PNH China, a legally recognized public welfare patient mutual aid organization established in April 2012. The organization comprised over 400 members, consisting of patients, their families, volunteers, and dedicated physicians and specialists. The survey assessed the patients’ HRQOL measured by 5L, socio-demographic, and clinical characteristics using a self-administered structured questionnaire through a professional online survey platform. The inclusion criteria were: (i) Accessible and willing to join in the study. (ii) Clinical diagnosis of PNH. Prior to the survey, investigators, who were managers of PNH China and well-trained PNH patients, provided a detailed introduction to the patients regarding the survey’s purpose, process, rights, and the questionnaire. After providing informed consent, patients could choose to either participate in the survey or directly opt out. If the patients were unable to complete the questionnaire, their guardians were authorized to do so on their behalf.

The study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Dalian Medical University.

EQ-5D-5L

5L contains a descriptive system including five dimensions: Mobility (MO), Self-Care (SC), Usual Activities (UA), Pain/Discomfort (PD), Anxiety/Depression (AD). Each dimension has five response levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems, and extreme problems/unable to. The system thus defines a total of 3,125 (55) health states. Each state can be translated into a single utility-based index score (i.e., health utility score) using a specific utility value set. Health utility score (HUS) is anchored on a scale from 0 (death) to 1 (full health), with a higher score indicating higher value of HRQOL [23–27]. In the study, the 5L HUS was calculated by adopting the 5L value set for China developed by Luo et al. [28] 5L also includes the EQ-VAS, recording the self-rated health status of the patients on a vertical visual analogue scale (VAS). The respondents rate their current health on a scale ranging from 0 (worst imaginable health status) to 100 (best imaginable health status) [25].

Social-demographic and clinical characteristics

The questionnaire assessed the following social-demographic characteristics: gender, age, ethnicity, educational status, marital status, fertility situation, school/employment status, total personal income for the past year and health insurance. It also inquired about clinical characteristics, including initial symptoms of PNH, common complications during the past year (i.e., stones, thrombosis, renal failure, pulmonary hypertension, BMF, femoral head necrosis), misdiagnosis, and the latest pathological grade.

Statistical analysis

The gathered data, exported in Excel format, was reviewed to eliminate any illogical patient data entries.

The social-demographic and clinical characteristics, and HRQOL of the patients were summarized using descriptive statistics with mean, standard deviations (SD), medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables; and frequencies, percentages for categorical variables.

Multiple linear regression analysis was utilized to explore the influence of above mentioned socio-demographic and clinical variables on HUS and VAS score (Table 1). To enhance the robustness of the analysis for the categorical variables, each category within a variable must have at least 16 observations according to expert opinion and statistical requirements. Variance inflation factor (VIF) was adopted to assess the multicollinearity among the independent variables, with the VIF value greater than 10 indicating the existence of multicollinearity. Multiple logistic regression was also used to assess the factors of self-reported EQ-5D problems. In the analysis, the responses to each of the five EQ-5D dimensions were classified as with and without problems. Five binary variables were thus generated and adopted as dependent variables in the five separate logistic models. An enter approach was adopted in the regression modelling, with the independent variables being coded as categorical variables and compared with a reference group.

Table 1.

Assignment of independent variables

| Variables | Variable definitions | Variable type |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male (0), Female (1) | Dichotomous variables |

| Age | Respondent’s age at the time of interview | Continuous quantitative variable |

| Ethnicity | Han (0), Other ethnicities (1) | Dichotomous variables |

| Educational status | Junior high school and below (1,0,0) | Multi-categorical variable |

| High school, technical secondary school or vocational high school, etc. (0,1,0) | ||

| Junior college, college degree (0,0,0) | ||

| Postgraduate or above (0,0,1) | ||

| Marital status | Have a partner (0), Single (1) | Dichotomous variables |

| Fertility situation | No (0), Yes (1) | Dichotomous variables |

| School/employment status | No (0), Yes (1) | Dichotomous variables |

| Total personal income for the past year | <35,128 CNY (0), ≥ 35,128 CNY (1) | Dichotomous variables |

| Health insurance | National Basic Medical Insurance [NO (0), Yes (1)], Commercial health insurance [NO (0), Yes (1)] | Dichotomous variables |

| Initial symptom | Hemoglobinuria [NO (0), Yes (1)] | Dichotomous variables |

| Anemia (Fatigue, Tachycardia, Shortness of breath, Headache) [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Jaundice [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Pancytopenia, bone marrow hematopoietic failure [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Abdominal pain [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Back pain [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Erectile dysfunction [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Dysphagia [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Cognitive disorder [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Several common complications during the past year | Stones [NO (0), Yes (1)] | Dichotomous variables |

| Thrombosis [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Renal failure [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Pulmonary hypertension [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Bone marrow failure (BMF) [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Necrosis of the femoral head [NO (0), Yes (1)] | ||

| Misdiagnosis | No (0), Yes (1) | Dichotomous variables |

| The latest pathological grade | Classic PNH (0,0) | Multi-categorical variable |

| PNH in the setting of another specified bone marrow disorder (1,0) | ||

| Sub-clinical PNH (0,1) |

35,128: The 2021 annual average per capita disposable income of Chinese residents

CNY: Chinese Yuan

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 24). The statistical significance of this study was set at 0.05 level.

Results

A total of 332 patients filled the questionnaire. Data from three patients with logical errors were excluded, and the other 329 patients from 26 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities were included in the subsequent analysis.

Social-demographic and clinical characteristics of PNH patients

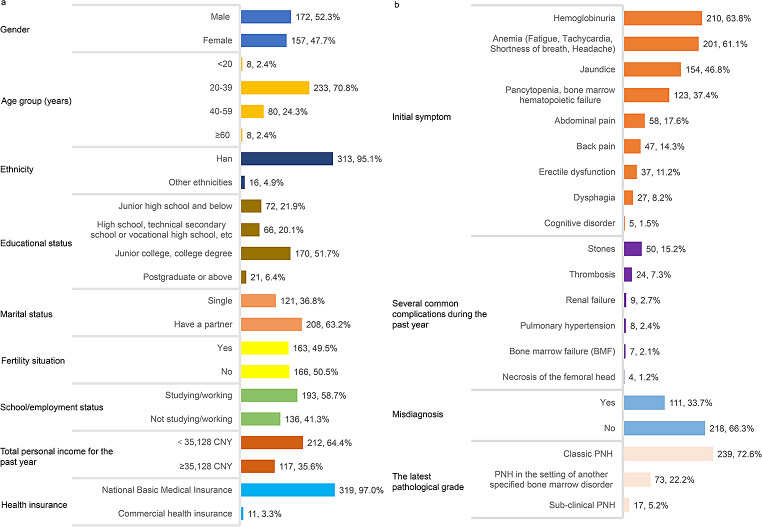

The characteristics of the PNH patients are summarized in Fig. 1. Their mean (SD) age was 35.3 (10.0) years and median age (IQR) was 34.0 (28.0–40.0) years, with 52.3% of the patients being male. The majority of them (70.8%) were between 20 and 39 years, and 58.1% of the patients had attained an education level of junior college or above. A significant majority of patients (64.4%) reported an annual income that fell below the 2021 annual average per capita disposable income of Chinese residents (i.e., 35,128 CNY) [29].

Fig. 1.

Indicators of social-demographic and clinical characteristics of all survey patients (N = 329). Age (years old): Mean = 35.3, SD = 10.0, Median = 34.0, IQR = 28.0–40.0, Range = 16.0–74.0. 35,128: the 2021 annual average per capita disposable income of Chinese residents. CNY: Chinese Yuan

Among the patients, 72.6% were diagnosed with classic PNH and 22.2% were diagnosed with PNH in the setting of another specified bone marrow disorder. A significant proportion of patients (63.8%) exhibited hemoglobinuria as an initial symptom. Anemia (fatigue, tachycardia, shortness of breath, headache) constituted the initial symptoms for 61.1% of the patients. Additionally, 15.2% of the patients experienced stone-related complications, and 7.3% presented with thrombosis during the past year. A misdiagnosis was reported by 33.7% of patients. (Fig. 1)

The median duration (IQR) from onset of symptoms to the time of the survey was 89.0 (44.0–155.5) months, and the mean duration (SD) was 104.7 (74.9) months. In the past year, 80.2% of 329 patients surveyed received treatment, whereas 19.8% did not. Among the patients with treatment, 91.3% were administered medication for symptomatic supportive care. Furthermore, 62.1% of these patients underwent red blood cell/platelet transfusion, and 18.2% were treated with novel complement inhibitors, all of which were provided as clinical donations. The proportion of low-dose combined chemotherapy was 1.1%; and hematopoietic stem cell transplant treatment was 0.4%.

Health-related quality of life of PNH patients

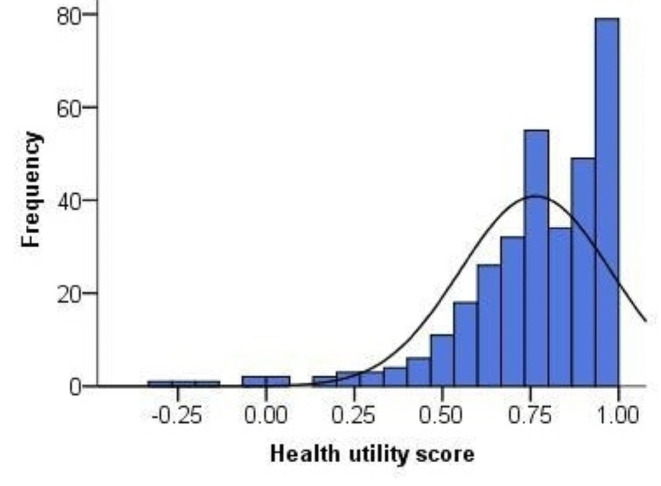

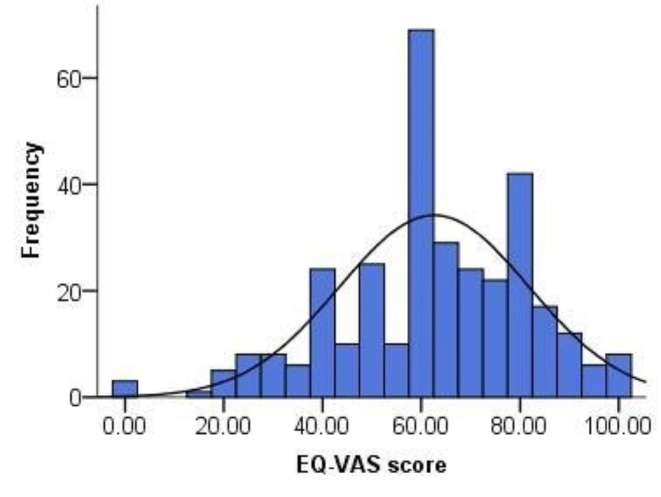

The proportion of reporting problems in AD dimension (81.5%) was higher than the prevalence in the other dimensions (PD: 69.9%, UA: 53.5%, MO: 51.4%, SC: 13.4%) (Table 2), and thus only 9.1% of the patients reported full health defined by the 5L (i.e., no problems in all the 5 dimensions). The distribution of the 5L HUS was negatively skewed (Fig. 2), with the mean (SD) and median (IQR) values being 0.76 (0.21) and 0.78 (0.68–0.91). Similarly, the distribution of VAS score was also negatively skewed (Fig. 3), with the mean (SD) and median (IQR) values being 62.61 (19.20) and 62.00 (50.00–79.00), respectively.

Table 2.

Sample distribution of EQ-5D-5L [N (%)] of Chinese PNH patients

| Dimensions | Mobility | Self-care | Usual Activities | Pain/Discomfort | Anxiety/Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No problems | 160 (48.6) | 285 (86.6) | 153 (46.5) | 99 (30.1) | 61 (18.5) |

| Slight problems | 119 (36.2) | 35 (10.6) | 133 (40.4) | 175 (53.2) | 143 (43.5) |

| Moderate problems | 38 (11.6) | 4 (1.2) | 34 (10.3) | 41 (12.5) | 82 (24.9) |

| Severe problems | 9 (2.7) | 5 (1.5) | 7 (2.1) | 10 (3.0) | 36 (10.9) |

| Extreme problems/Unable to | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.6) | 4 (1.2) | 7 (2.1) |

Fig. 2.

Frequency distribution of EQ-5D-5L health utility score. (Mean = 0.76, SD = 0.21, Median = 0.78, IQR = 0.68–0.91)

Fig. 3.

Frequency distribution of EQ-5D-5L-VAS score. (Mean = 62.61, SD = 19.20, Median = 62.00, IQR = 50.00–79.00)

Tables 3 and 4 present the 5L HUS and EQ-VAS score across various subgroups. Males had the mean (SD) HUS and VAS score of 0.79 (0.20) and 63.46 (19.47), which are higher than those of females: 0.73 (0.22) for HUS and 61.68 (18.91) for VAS. Compared to the patients older than 20 years, those younger patients reported the highest mean (SD) HUS of 0.80 (0.13) while having the lowest VAS score of 57.75 (20.50). Those with a higher socio-economic status (e.g., better educated, higher income and people who are studying or working) generally exhibited higher HUS and VAS score. The patients who showed initial symptoms and presented with common PNH symptoms had worse HRQOL than those who did not manifest these symptoms. For instance, the patients who exhibited hemoglobinuria as their initial symptom had lower mean (SD) HUS and VAS score of 0.75 (0.22) and 60.42 (19.63), respectively, compared to those who did not show signs of hemoglobinuria with the score being 0.78 (0.19) and 66.48 (17.83). Furthermore, compared to the patients without complications during the past year, those with complication(s) had lower HRQOL. For example, the patients without thrombosis had the mean HUS (SD) of 0.78 (0.20) and VAS score of 63.57 (18.38). In contrast, those with thrombosis reported the mean (SD) HUS of 0.59 (0.32) and VAS score of 50.42 (24.93). Among the patients with different kinds of pathological grades, the patients in the setting of another specified bone marrow disorder exhibited the lowest mean (SD) HUS and VAS score of 0.74 (0.21) and 58.81 (21.31); the patients with the subclinical type had the highest mean (SD) HUS and VAS score of 0.81 (0.23) and 72.59 (21.87).

Table 3.

The EQ-5D-5L health utility score (HUS) and EQ-VAS score of various subgroups (social-demographic characteristics)

| Variables | N | HUS | VAS score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 172 | 0.79 | 0.20 | 63.46 | 19.47 |

| Female | 157 | 0.73 | 0.22 | 61.68 | 18.91 |

| Age group (years) | |||||

| < 20 | 8 | 0.80 | 0.13 | 57.75 | 20.50 |

| 20–39 | 233 | 0.77 | 0.21 | 62.73 | 18.89 |

| 40–59 | 80 | 0.75 | 0.22 | 62.63 | 20.12 |

| ≥ 60 | 8 | 0.70 | 0.34 | 63.88 | 20.67 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Han | 313 | 0.76 | 0.22 | 62.72 | 19.09 |

| Other ethnicities | 16 | 0.80 | 0.14 | 60.50 | 21.76 |

| Educational status | |||||

| Junior high school and below | 72 | 0.70 | 0.31 | 56.07 | 20.44 |

| High school, technical secondary school or vocational high school, etc. | 66 | 0.76 | 0.19 | 60.48 | 19.54 |

| Junior college, college degree | 170 | 0.78 | 0.17 | 65.51 | 17.79 |

| Postgraduate or above | 21 | 0.82 | 0.14 | 68.24 | 19.26 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Have a partner | 208 | 0.76 | 0.21 | 63.07 | 19.31 |

| Single | 121 | 0.77 | 0.22 | 61.82 | 19.05 |

| Fertility situation | |||||

| Yes | 163 | 0.76 | 0.22 | 62.69 | 19.48 |

| No | 166 | 0.77 | 0.21 | 62.54 | 18.97 |

| School/employment status | |||||

| Yes | 193 | 0.80 | 0.19 | 65.46 | 18.63 |

| No | 136 | 0.71 | 0.24 | 58.57 | 19.34 |

| Total personal income for the past year | |||||

| <35,128 CNY | 212 | 0.73 | 0.24 | 59.29 | 19.29 |

| ≥ 35,128 CNY | 117 | 0.82 | 0.14 | 68.63 | 17.56 |

| Health insurance | |||||

| National Basic Medical Insurance | |||||

| Yes | 319 | 0.76 | 0.21 | 62.22 | 19.17 |

| No | 10 | 0.77 | 0.25 | 75.00 | 16.60 |

| Commercial health insurance | |||||

| Yes | 11 | 0.86 | 0.12 | 69.09 | 27.55 |

| No | 318 | 0.76 | 0.22 | 62.39 | 18.86 |

HUS: Health utility score

VAS: Visual analogue scale

SD: Standard deviation

35,128: The 2021 annual average per capita disposable income of Chinese residents

CNY: Chinese Yuan

Table 4.

The EQ-5D-5L health utility score (HUS) and EQ-VAS score of various subgroups (clinical characteristics)

| Variables | N | HUS | VAS score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Initial symptom | |||||

| Hemoglobinuria | |||||

| Yes | 210 | 0.75 | 0.22 | 60.42 | 19.63 |

| No | 119 | 0.78 | 0.19 | 66.48 | 17.83 |

| Anemia (Fatigue, Tachycardia, Shortness of breath, Headache) | |||||

| Yes | 201 | 0.73 | 0.23 | 60.30 | 18.95 |

| No | 128 | 0.82 | 0.18 | 66.23 | 19.09 |

| Jaundice | |||||

| Yes | 154 | 0.74 | 0.22 | 60.95 | 19.68 |

| No | 175 | 0.78 | 0.20 | 64.07 | 18.69 |

| Pancytopenia, bone marrow hematopoietic failure | |||||

| Yes | 123 | 0.73 | 0.24 | 61.38 | 20.32 |

| No | 206 | 0.78 | 0.19 | 63.34 | 18.50 |

| Abdominal pain | |||||

| Yes | 58 | 0.68 | 0.28 | 56.72 | 20.91 |

| No | 271 | 0.78 | 0.19 | 63.87 | 18.61 |

| Back pain | |||||

| Yes | 47 | 0.61 | 0.33 | 54.36 | 19.15 |

| No | 282 | 0.79 | 0.18 | 63.99 | 18.89 |

| Erectile dysfunction | |||||

| Yes | 37 | 0.76 | 0.24 | 63.92 | 17.94 |

| No | 292 | 0.76 | 0.21 | 62.45 | 19.37 |

| Dysphagia | |||||

| Yes | 27 | 0.66 | 0.29 | 56.37 | 15.91 |

| No | 302 | 0.77 | 0.20 | 63.17 | 19.39 |

| Cognitive disorder | |||||

| Yes | 5 | 0.81 | 0.13 | 53.40 | 33.31 |

| No | 324 | 0.76 | 0.22 | 62.75 | 18.95 |

| Several common complications during the past year | |||||

| Stones | |||||

| Yes | 50 | 0.71 | 0.21 | 60.02 | 22.24 |

| No | 279 | 0.77 | 0.21 | 63.08 | 18.61 |

| Thrombosis | |||||

| Yes | 24 | 0.59 | 0.32 | 50.42 | 24.93 |

| No | 305 | 0.78 | 0.20 | 63.57 | 18.38 |

| Renal failure | |||||

| Yes | 9 | 0.58 | 0.33 | 55.11 | 22.05 |

| No | 320 | 0.77 | 0.21 | 62.82 | 19.11 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | |||||

| Yes | 8 | 0.64 | 0.24 | 48.88 | 23.64 |

| No | 321 | 0.77 | 0.21 | 62.95 | 18.99 |

| Bone marrow failure (BMF) | |||||

| Yes | 7 | 0.44 | 0.28 | 40.14 | 10.88 |

| No | 322 | 0.77 | 0.21 | 63.10 | 19.05 |

| Necrosis of the femoral head | |||||

| Yes | 4 | 0.75 | 0.11 | 53.75 | 22.04 |

| No | 325 | 0.76 | 0.22 | 62.72 | 19.17 |

| Misdiagnosis | |||||

| Yes | 111 | 0.75 | 0.24 | 62.68 | 17.83 |

| No | 218 | 0.77 | 0.20 | 62.58 | 19.90 |

| The latest pathological grade | |||||

| Classic PNH | 239 | 0.77 | 0.21 | 63.06 | 18.07 |

| PNH in the setting of another specified bone marrow disorder | 73 | 0.74 | 0.21 | 58.81 | 21.31 |

| Sub-clinical PNH | 17 | 0.81 | 0.23 | 72.59 | 21.87 |

| Total | 329 | 0.76 | 0.21 | 62.61 | 19.20 |

HUS: Health utility score

VAS: Visual analogue scale

SD: Standard deviation

Influencing factors of EQ-5D-5L health utility score and EQ-VAS scores

Negative correlation with HUS was observed with three clinical factors including initial symptoms of anemia (fatigue, tachycardia, shortness of breath, headache) (B=-0.057, 95%CI: [-0.105,-0.010], p = 0.017), back pain (B=-0.146, 95%CI: [-0.214,-0.078], p = 0.000), and complication of thrombosis (B=-0.161, 95%CI: [-0.245,-0.077], p = 0.000) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with EQ-5D-5L health utility score of Chinese PNH patients

| Independent variable | Coefficient (95%CI) | P | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.908 (0.781,1.035) | 0.000 | |

| Gender (Male) | |||

| Female | -0.044(-0.091,0.003) | 0.067 | 1.258 |

| Age | -0.002(-0.004,0.001) | 0.228 | 1.604 |

| Ethnicity (Han) | |||

| Other ethnicities | -0.001(-0.101,0.100) | 0.988 | 1.079 |

| Educational status (Junior college, college degree) | |||

| Junior high school and below | -0.031 (-0.091,0.029) | 0.315 | 1.420 |

| High school, technical secondary school or vocational high school, etc. | -0.011 (-0.071,0.049) | 0.720 | 1.343 |

| Postgraduate or above | 0.010 (-0.080,0.101) | 0.823 | 1.129 |

| Marital status (Have a partner) | |||

| Single | 0.011 (-0.046,0.067) | 0.716 | 1.727 |

| Fertility situation (No) | |||

| Yes | 0.013 (-0.046,0.073) | 0.654 | 2.005 |

| School/employment status (No) | |||

| Yes | 0.046 (-0.006,0.099) | 0.083 | 1.534 |

| Total personal income for the past year (<35,128 CNY) | |||

| ≥ 35,128 CNY | 0.048 (-0.009,0.104) | 0.096 | 1.657 |

| Hemoglobinuria (No) | |||

| Yes | -0.015 (-0.063,0.033) | 0.527 | 1.219 |

| Anemia (Fatigue, Tachycardia, Shortness of breath, Headache) (No) | |||

| Yes | -0.057 (-0.105,-0.010) | 0.017 | 1.208 |

| Jaundice (No) | |||

| Yes | 0.006 (-0.042,0.055) | 0.804 | 1.346 |

| Pancytopenia, bone marrow hematopoietic failure (No) | |||

| Yes | -0.030 (-0.076,0.016) | 0.199 | 1.133 |

| Abdominal pain (No) | |||

| Yes | -0.003 (-0.065,0.060) | 0.935 | 1.301 |

| Back pain (No) | |||

| Yes | -0.146 (-0.214,-0.078) | 0.000 | 1.317 |

| Erectile dysfunction (No) | |||

| Yes | 0.029 (-0.047,0.105) | 0.456 | 1.331 |

| Dysphagia (No) | |||

| Yes | -0.052 (-0.137,0.032) | 0.226 | 1.236 |

| Stones (No) | |||

| Yes | -0.040 (-0.101,0.021) | 0.198 | 1.102 |

| Thrombosis (No) | |||

| Yes | -0.161 (-0.245,-0.077) | 0.000 | 1.101 |

| Misdiagnosis (No) | |||

| Yes | -0.036 (-0.083,0.010) | 0.122 | 1.097 |

| The latest pathological grade (Classic PNH) | |||

| PNH in the setting of another specified bone marrow disorder | -0.028 (-0.082,0.026) | 0.307 | 1.154 |

| Sub-clinical PNH | -0.009 (-0.109,0.091) | 0.862 | 1.129 |

| Adjusted R 2 | 0.193 |

CI: Confidence interval

VIF: Variance inflation factor

P: p value

35,128: The 2021 annual average per capita disposable income of Chinese residents

CNY: Chinese Yuan

The analysis of VAS score revealed that the patients with the income more than 35,128 CNY in the past year exhibited higher score (B = 5.708, 95%CI: [0.464,10.951], p = 0.033). VAS score was negatively predicted by the initial symptom of hemoglobinuria (B=-5.226, 95%CI: [-9.708,-0.745], p = 0.022) and presence of thrombosis (B=-10.330, 95%CI: [-18.198,-2.463], p = 0.010) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Factors associated with EQ-VAS score of Chinese PNH patients

| Independent variable | Coefficient (95%CI) | P | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 70.136 (58.285,81.987) | 0.000 | |

| Gender (Male) | |||

| Female | -0.153 (-4.532,4.226) | 0.945 | 1.258 |

| Age | 0.025 (-0.223,0.273) | 0.843 | 1.604 |

| Ethnicity (Han) | |||

| Other ethnicities | -5.460 (-14.875,3.956) | 0.255 | 1.079 |

| Educational status (Junior college, college degree) | |||

| Junior high school and below | -5.356 (-10.975,0.263) | 0.062 | 1.420 |

| High school, technical secondary school or vocational high school, etc. | -4.038 (-9.681,1.605) | 0.160 | 1.343 |

| Postgraduate or above | 1.660 (-6.814,10.135) | 0.700 | 1.129 |

| Marital status (Have a partner) | |||

| Single | 0.354 (-4.960,5.667) | 0.896 | 1.727 |

| Fertility situation (No) | |||

| Yes | -0.190 (-5.712,5.333) | 0.946 | 2.005 |

| School/employment status (No) | |||

| Yes | 1.961 (-2.944,6.866) | 0.432 | 1.534 |

| Total personal income for the past year (<35,128 CNY) | |||

| ≥ 35,128 CNY | 5.708 (0.464,10.951) | 0.033 | 1.657 |

| Hemoglobinuria (No) | |||

| Yes | -5.226 (-9.708,-0.745) | 0.022 | 1.219 |

| Anemia (Fatigue, Tachycardia, Shortness of breath, Headache) (No) | |||

| Yes | -4.248 (-8.643,0.147) | 0.058 | 1.208 |

| Jaundice (No) | |||

| Yes | -0.285 (-4.817,4.248) | 0.902 | 1.346 |

| Pancytopenia, bone marrow hematopoietic failure (No) | |||

| Yes | -0.844 (-5.134,3.446) | 0.699 | 1.133 |

| Abdominal pain (No) | |||

| Yes | -1.494 (-7.329,4.342) | 0.615 | 1.301 |

| Back pain (No) | |||

| Yes | -6.092 (-12.487,0.303) | 0.062 | 1.317 |

| Erectile dysfunction (No) | |||

| Yes | 6.600 (-0.520,13.719) | 0.069 | 1.331 |

| Dysphagia (No) | |||

| Yes | -3.645 (-11.542,4.251) | 0.364 | 1.236 |

| Stones (No) | |||

| Yes | -2.579 (-8.281,3.123) | 0.374 | 1.102 |

| Thrombosis (No) | |||

| Yes | -10.330 (-18.198,-2.463) | 0.010 | 1.101 |

| Misdiagnosis (No) | |||

| Yes | -1.491 (-5.811,2.830) | 0.498 | 1.097 |

| The latest pathological grade (Classic PNH) | |||

| PNH in the setting of another specified bone marrow disorder | -4.300 (-9.341,0.740) | 0.094 | 1.154 |

| Sub-clinical PNH | 5.157 (-4.201,14.515) | 0.279 | 1.129 |

| Adjusted R 2 | 0.123 |

CI: Confidence interval

VIF: Variance inflation factor

P: p value

35,128: The 2021 annual average per capita disposable income of Chinese residents

CNY: Chinese Yuan

Variance inflation factor (VIF) value of all variables in the two linear models was less than 10, indicating the absence of multicollinearity.

Influencing factors of EQ-5D-5L problems

Significant factors influencing the 5L problems were shown in Table 7. Patients with initial symptoms of anemia (fatigue, tachycardia, shortness of breath, headache) experienced an increased risk of reporting problems in MO (OR [95%CI]: 2.37[1.40,4.02], p = 0.001), SC (OR [95%CI]: 3.69[1.46,9.38], p = 0.006), and UA (OR [95%CI]: 3.06[1.78,5.26], p = 0.000) dimensions. Compared to the patients with an income below 35,128 CNY, those who earned higher had experienced fewer SC problems (OR [95%CI]: 0.32[0.11,0.94], p = 0.038). Compared to male, female faced a higher risk of UA problems (OR [95%CI]: 1.79[1.04,3.08], p = 0.036). Moreover, compared with the patients who were neither studying nor employed, the patients who were studying or employed experienced less UA problems (OR [95%CI]: 0.51[0.28,0.94], p = 0.032). Compared with the patients without complications of thrombosis and stones during the past year, the patients with complications of stones (OR [95%CI]: 2.78[1.15,6.71], p = 0.023) and thrombosis (OR [95%CI]: 5.30[1.15,24.55], p = 0.033) experienced an increased risk of PD problems. The patients with sub-clinical PNH tended to report fewer AD problems than the patients with classic PNH (OR [95%CI]: 0.23[0.07,0.73], p = 0.013).

Table 7.

Multivariate analyses evaluating associations of factors with each of the five health dimensions

| Dimensions | Mobility | Self-Care | Usual Activities | Pain/Discomfort | Anxiety/Depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | |

| Gender (Male) | ||||||||||

| Female | 1.67(0.99,2.82) | 0.055 | 0.96(0.44,2.10) | 0.915 | 1.79(1.04,3.08) | 0.036 | 1.13(0.64,2.01) | 0.666 | 1.67(0.85,3.27) | 0.136 |

| Age | 1.03(0.99,1.06) | 0.118 | 1.03(0.98,1.07) | 0.230 | 1.02(0.99,1.05) | 0.236 | 1.02(0.98,1.05) | 0.395 | 1.01(0.97,1.04) | 0.806 |

| Ethnicity (Han) | ||||||||||

| Other ethnicities | 1.41(0.46,4.32) | 0.544 | 0.52(0.06,4.72) | 0.565 | 1.96(0.59,6.54) | 0.274 | 1.44(0.41,5.01) | 0.567 | 0.96(0.24,3.90) | 0.959 |

| Educational status (Junior college, college degree) | ||||||||||

| Junior high school and below | 0.63(0.32,1.23) | 0.172 | 1.19(0.49,2.93) | 0.700 | 0.54(0.27,1.08) | 0.081 | 0.80(0.38,1.68) | 0.559 | 0.48(0.20,1.17) | 0.107 |

| High school, technical secondary school or vocational high school, etc. | 1.37(0.69,2.70) | 0.368 | 0.80(0.29,2.19) | 0.662 | 1.55(0.76,3.16) | 0.232 | 1.63(0.77,3.45) | 0.206 | 0.44(0.19,1.01) | 0.053 |

| Postgraduate or above | 0.91(0.34,2.46) | 0.847 | 1.62(0.30,8.64) | 0.574 | 1.66(0.59,4.64) | 0.335 | 0.65(0.23,1.82) | 0.410 | 2.30(0.48,11.03) | 0.297 |

| Marital status (Have a partner) | ||||||||||

| Single | 0.63(0.33,1.19) | 0.156 | 0.93(0.36,2.41) | 0.887 | 0.58(0.30,1.13) | 0.107 | 0.62(0.32,1.23) | 0.173 | 2.07(0.89,4.82) | 0.090 |

| Fertility situation (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.96(0.49,1.86) | 0.895 | 1.33(0.49,3.63) | 0.582 | 0.82(0.41,1.63) | 0.570 | 0.82(0.40,1.70) | 0.602 | 1.23(0.54,2.80) | 0.621 |

| School/employment status (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.58(0.32,1.05) | 0.071 | 0.58(0.25,1.34) | 0.202 | 0.51(0.28,0.94) | 0.032 | 0.68(0.36,1.29) | 0.239 | 0.61(0.28,1.31) | 0.200 |

| Total personal income for the past year (<35,128 CNY) | ||||||||||

| ≥ 35,128 CNY | 0.74(0.39,1.38) | 0.339 | 0.32(0.11,0.94) | 0.038 | 0.85(0.44,1.64) | 0.630 | 1.07(0.55,2.08) | 0.846 | 0.77(0.35,1.68) | 0.508 |

| Hemoglobinuria (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.04(0.61,1.77) | 0.886 | 0.93(0.42,2.05) | 0.858 | 0.89(0.51,1.54) | 0.671 | 0.77(0.43,1.39) | 0.387 | 0.82(0.41,1.66) | 0.587 |

| Anemia (Fatigue, Tachycardia, Shortness of breath, Headache) (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 2.37(1.40,4.02) | 0.001 | 3.69(1.46,9.38) | 0.006 | 3.06(1.78,5.26) | 0.000 | 1.68(0.97,2.92) | 0.065 | 1.22(0.64,2.34) | 0.546 |

| Jaundice (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.98(0.57,1.68) | 0.932 | 0.62(0.27,1.46) | 0.275 | 1.68(0.96,2.93) | 0.069 | 1.15(0.64,2.05) | 0.646 | 1.24(0.63,2.48) | 0.534 |

| Pancytopenia, bone marrow hematopoietic failure (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.45(0.87,2.42) | 0.156 | 1.35(0.65,2.81) | 0.422 | 1.23(0.72,2.08) | 0.455 | 1.16(0.65,2.05) | 0.620 | 0.80(0.41,1.56) | 0.518 |

| Abdominal pain (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.59(0.30,1.18) | 0.134 | 0.45(0.15,1.33) | 0.150 | 0.58(0.29,1.20) | 0.143 | 0.93(0.41,2.08) | 0.853 | 1.44(0.51,4.05) | 0.494 |

| Back pain (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.41(0.66,3.03) | 0.375 | 2.57(0.94,7.03) | 0.066 | 2.15(0.95,4.84) | 0.066 | 2.02(0.77,5.31) | 0.153 | 2.06(0.62,6.83) | 0.236 |

| Erectile dysfunction (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.93(0.41,2.13) | 0.870 | 0.92(0.28,3.02) | 0.884 | 0.60(0.26,1.40) | 0.234 | 0.78(0.30,1.99) | 0.601 | 1.13(0.39,3.30) | 0.824 |

| Dysphagia (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.73(0.67,4.44) | 0.257 | 2.02(0.56,7.19) | 0.281 | 1.01(0.38,2.66) | 0.982 | 3.43(0.90,13.03) | 0.070 | 1.08(0.29,4.02) | 0.914 |

| Stones (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.40(0.70,2.81) | 0.344 | 0.92(0.35,2.46) | 0.872 | 2.03(0.98,4.22) | 0.058 | 2.78(1.15,6.71) | 0.023 | 1.75(0.64,4.75) | 0.273 |

| Thrombosis (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 2.08(0.80,5.40) | 0.133 | 2.22(0.66,7.55) | 0.200 | 1.56(0.60,4.08) | 0.363 | 5.30(1.15,24.55) | 0.033 | 4.03(0.51,31.98) | 0.187 |

| Misdiagnosis (No) | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1.33(0.79,2.23) | 0.286 | 1.89(0.90,3.97) | 0.093 | 1.05(0.62,1.79) | 0.851 | 1.21(0.68,2.14) | 0.516 | 1.14(0.58,2.24) | 0.697 |

| The latest pathological grade (Classic PNH) | ||||||||||

| PNH in the setting of another specified bone marrow disorder | 1.33(0.73,2.43) | 0.357 | 1.20(0.50,2.84) | 0.683 | 1.86(0.99,3.50) | 0.055 | 1.57(0.80,3.06) | 0.190 | 0.92(0.43,1.94) | 0.822 |

| Sub-clinical PNH | 1.41(0.47,4.26) | 0.540 | 2.77(0.62,12.32) | 0.182 | 0.63(0.19,2.10) | 0.456 | 0.33(0.10,1.07) | 0.066 | 0.23(0.07,0.73) | 0.013 |

CI: Confidence interval

OR: Odds Ratio

P: p value

35,128: The 2021 annual average per capita disposable income of Chinese residents

CNY: Chinese Yuan

Discussion

The study expounded the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of Chinese PNH patients and assessed their HRQOL based on a sample with better representativeness. Furthermore, we explored the determinants influencing HRQOL of the patients within the Chinese context. Hence, the study has deepened the understanding of the profile and HRQOL of PNH patients in China.

Consistent with previous findings [8, 13, 30–32], 95.1% of the patients fell between 20 and 59 years, and 70.8% were even between 20 and 39 years in our study. These suggest that PNH predominantly manifests in early adulthood and could affect individuals during their most productive years. A worrying 64.4% of the patients reported annual income below the 2021 annual average per capita disposable income of Chinese residents, implying potential economic strain or burden due to the disease [33–35]. Hence, to reduce its impact on productivity, the efficient control of the disease, particularly the management of hemolysis (the major characteristic of PNH [36–39]), is required.

Of significant note, our study revealed that 63.8% of the patients initially presented with hemoglobinuria, a clinical hallmark of PNH [8, 18]. This observation has interesting resonance with the report by Lee et al. [40] that hemoglobinuria was a significant predictor of thromboembolism in Asian patients with PNH. Similarly, other studies [36, 41] have also shown that PNH-related symptoms, such as hemoglobinuria or dyspnea, increase the risk of thrombosis. Those reinforce the exigency of research to delineate the relationship between clinical manifestations of PNH and thrombosis susceptibility, thereby facilitating the evolution of efficacious prophylactic and therapeutic approaches.

Consistent with previous evidence [14, 42–44], the misdiagnosis rate was as high as 33.7% in our study. This means that the accurate diagnosis of PNH remains challenging, though its symptoms are common [30, 36, 45–49]. The high rate may have serious implications including prolonged pain, exacerbating mental health challenges and rising medical costs [35]. Therefore, we urgently need to refine existing PNH diagnosis and treatment strategies to raise clinician awareness and enhance the timely and accurate diagnosis.

Compared to HRQOL of the general Chinese population measured by 5L [50], our sample demonstrated a markedly inferior HRQOL. Specifically, the proportions of reporting problems in four dimensions (AD: 81.5% vs. 47.2%, PD: 69.9% vs. 44.8%, UA: 53.5% vs. 25.1%, and MO: 51.4% vs. 26.8%) were much higher which could be attributed to the fear of PNH leading to a feeling of “life limitation” and “frailty” in these patients [51]. The average 5L HUS and VAS score (i.e., 0.76 & 62.61) also trailed significantly behind those of the general Chinese population who achieved mean of 0.93 and 84.57. Such divergences underscore the unique challenges faced by PNH patients in China, particularly in the AD dimension, highlighting the considerable psychological burden associated with PNH. Hence, a holistic healthcare approach integrating both mental and physical aspects is imperative for PNH patients in China. It is noteworthy that the proportion of SC problems was lower in our study (13.4% vs. 23.7%). This may be due to their high level of concern for their own health, regular medical follow-up, and the need for disease management. Moreover, the mean age of the general Chinese population was older (42.8 years vs. 35.3 years), and older individuals are more frequently encounter self-care challenges.

The regression results showed that demographic characteristics, gender, school/employment status, total personal income, and clinical characteristics such as initial symptoms of hemoglobinuria, anemia (fatigue, tachycardia, shortness of breath, headache), and back pain, complications of stones, thrombosis, and pathological grade were significant factors exerting differential effects on HUS, VAS score, or certain EQ-5D dimensions in Chinese PNH patients.

Gender was the key factor associated with UA problems (OR = 1.79), which may be attributed to multiple factors including cultural and social expectations. Meanwhile, the patients with PNH at school or in the work environment were at lower risk of UA problems relative to patients who were not at school or employed (OR = 0.51). This may be because these settings provide better support and adaptation, as well as opportunities to promote patients’ participation in daily activities and to maintain function [52–54]. High-income patients were less likely to face SC problems (OR: 0.32) and performed better on VAS score (p < 0.05), which may be because they could afford high-quality medical services. The finding is consistent with earlier studies and further confirms the strong association between socioeconomic factors and health status [53–57].

Our findings confirm that the initial symptoms of PNH (i.e., hemoglobinuria, anemia [fatigue, tachycardia, shortness of breath, headache] and back pain) have a significantly negative impact on HRQOL of the patients. The symptoms not only lead to physical discomfort, but also aggravate psychological burden, thus affecting the patient’s overall HRQOL [8, 34, 35, 51, 58, 59]. The logistic analysis further revealed that the patients with the symptoms performed significantly worse on several HRQOL dimensions (MO, SC, UA) than the patients without the symptoms. These results thus highlight the importance of early identification, diagnosis and treatment of the patients with PNH to relieve the impact of the symptoms.

Thrombosis was a key factor affecting HRQOL, specifically on the PD dimension in our study. The finding is consistent with relevant findings from the international PNH registry [13] and further validates the clinical importance of preventing thrombosis in PNH management. Also, the patients with stones faced more problems on the PD dimension (OR = 2.78). These problems may not only limit a patient’s daily activities, but may also lead to mood swings and reduced sleep quality, thereby exacerbating anxiety and depressive symptoms [5, 35, 59–62]. Notably, patients with classic PNH were at higher risk of AD problems compared with those with sub-clinical PNH, suggesting that they may require more medical and psychological support.

Our research has identified key factors that influence specific dimensions of HRQOL in Chinese patients with PNH, such as physical functioning and mental health. Addressing these specific areas requires targeted and comprehensive measures. Firstly, existing health policies need to place greater emphasis on the recognition and management of early symptoms to mitigate the long-term impact of PNH. This can be achieved by integrating advanced screening technologies in primary care, increasing public health education, and developing more precise diagnostic and treatment guidelines. Secondly, the health system needs to integrate more effective disease management strategies, including patient education, psychological support, and the optimal allocation of medical resources. Furthermore, enhancing healthcare providers’ ability to recognize early symptoms of PNH is crucial. We recommend regular professional training and workshops to improve medical personnel’s sensitivity to PNH diagnoses. Collaboration with hematologists is also suggested to promote shared learning experiences and ensure a multidisciplinary approach to PNH management. Strengthening public awareness of PNH is also necessary. Media campaigns, community educational activities, and cooperation with patient support groups can effectively increase societal attention to this disease. Through these measures, we hope to improve the HRQOL for patients with PNH.

Our study has several limitations. First, the PNH patients recruited were all from a single institution, though it is the largest one for the patients in China. Second, we can not infer clear causality between HRQOL and the factors assessed due to the cross-sectional design. Although the associations provide useful initial insights into HRQOL in Chinese patients with PNH, an in-depth exploration of its longitudinal impact is still warranted. Third, the current sample size may have limited the detailed analysis of all variables.

Conclusion

In summary, the study described the profile and HRQOL of PNH patients in China, and elucidated the significant socio-demographic and clinical characteristics affecting their HRQOL. The findings could be adopted as the evidence for enhancing health status of PNH patients in China.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the study participants for their time and insight.

Abbreviations

- PNH

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria

- PIGA

Phosphatidylinositol glycan class A

- TEs

Thrombotic events

- BMF

Bone marrow failure

- HRQOL

Health-related quality of life

- 5L

EQ-5D-5L

- CNY

Chinese Yuan

- MO

Mobility

- SC

Self-Care

- UA

Usual Activities

- PD

Pain/Discomfort

- AD

Anxiety/Depression

- HUS

Health utility score

- VAS

Visual analogue scale

- SD

Standard deviations

- IQR

Interquartile ranges

- VIF

Variance inflation factor

- CI

Confidence interval

- P

p value

- OR

Odds Ratio

Author contributions

HY, SD, RF, ZL, NY and SC designed the studies. YY, PM, JS, NZ, HH, SC assisted with data collection and participated in survey. HY, SD, PW analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. PW, NY, SC revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in the present work.

Funding

“A Real World Study on the Situation of Children’s Medical Security in Liaoning Province Based on Interrupted Time Series Analysis, LJKMR20221296” and “Dalian Medical University Maternal Diseases on Newborns Interdisciplinary Research Cooperation Project Team Funding, JCHZ2023016”.

The funder did not influence on the conceptualization, study design or protocol, data analysis, the interpretation and collection of data, the conclusions drawn, preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to publish.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from PNH China, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study and so are not publicly available. The data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of PNH China.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of Dalian Medical University. Informed consent has been obtained of all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Huaxin Yu, Shengnan Duan and Pei Wang contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Contributor Information

Ni Yuan, Email: nier1209@163.com.

Sijia Che, Email: info@pnhchina.org.

References

- 1.Brodsky RA. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2014;124(18):2804–11. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-522128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill A, DeZern AE, Kinoshita T, et al. Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17028. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panse J. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: where we stand. Am J Hematol. 2023;98(Suppl 4):S20–32. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szlendak U, Budziszewska B, Spychalska J, et al. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: advances in the understanding of pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2022;132(6):16271. doi: 10.20452/pamw.16271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cançado RD, Araújo ADS, Sandes AF, et al. Consensus statement for diagnosis and treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2021;43(3):341–8. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2020.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillmen P, Lewis SM, Bessler M, et al. Natural history of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(19):1253–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511093331904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stern RM, Connell NT. Ravulizumab: a novel C5 inhibitor for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Ther Adv Hematol. 2019;10:2040620719874728. doi: 10.1177/2040620719874728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker C, Omine M, Richards S, et al. Diagnosis and management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2005;106(12):3699–709. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Socié G, Schrezenmeier H, Muus P, et al. Changing prognosis in paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria disease subcategories: an analysis of the International PNH Registry. Intern Med J. 2016;46(9):1044–53. doi: 10.1111/imj.13160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu F, Du Y, Han B. A comparative analysis of clinical characteristics of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria between Asia and Europe/America. Int J Hematol. 2016;103(6):649–54. doi: 10.1007/s12185-016-1995-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muñoz-Linares C, Ojeda E, Forés R, et al. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: a single Spanish center’s experience over the last 40 year. Eur J Haematol. 2014;93(4):309–19. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Rare Diseases in China. 2019;547–554.

- 13.Schrezenmeier H, Muus P, Socié G, et al. Baseline characteristics and disease burden in patients in the International Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria Registry. Haematologica. 2014;99(5):922–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.093161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrezenmeier H, Röth A, Araten DJ, et al. Baseline clinical characteristics and disease burden in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH): updated analysis from the International PNH Registry. Ann Hematol. 2020;99(7):1505–14. doi: 10.1007/s00277-020-04052-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Z, Wang P, Hong J et al. Health-related quality of life among Chinese patients with Crohn’s disease: a cross-sectional survey using the EQ-5D-5L. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2022;20(1):62. Published 2022 Apr 12. 10.1186/s12955-022-01969-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, Health-Related Quality of Life, and quality of life: what is the difference? PharmacoEconomics. 2016;34:645–9. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0389-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin S, Njai R, Barker L, et al. Summarizing health-related quality of life (HRQOL): development and testing of a one-factor model. Popul Health Metrics. 2016;14:22. doi: 10.1186/s12963-016-0091-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young NS, Meyers G, Schrezenmeier H, et al. The management of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: recent advances in diagnosis and treatment and new hope for patients. Semin Hematol. 2009;46(1 Suppl 1):S1–16. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panse J, Sicre de Fontbrune F, Burmester P, et al. The burden of illness of patients with paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria receiving C5 inhibitors in France, Germany and the United Kingdom: patient-reported insights on symptoms and quality of life. Eur J Haematol. 2022;109(4):351–63. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peipert JD, Kulasekararaj AG, Gaya A, et al. Patient preferences and quality of life implications of ravulizumab (every 8 weeks) and eculizumab (every 2 weeks) for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(9):e0237497. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai D, Hadker N, Francis A, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life reported among patients with Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria: impact of treatment with Pegcetacoplan and C5-Inhibitors. Blood. 2022;140:11445–46. doi: 10.1182/blood-2022-163821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quist SW, Postma AJ, Myrén KJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ravulizumab compared with eculizumab for the treatment of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria in the Netherlands. Eur J Health Econ. 2023;24(9):1455–72. doi: 10.1007/s10198-022-01556-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou T, Guan H, Wang L, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with different diseases measured with the EQ-5D-5L: a systematic review. Front Public Health. 2021;9:675523. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.675523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson AJ, Turner AJ. A comparison of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L. PharmacoEconomics. 2020;38(6):575–91. doi: 10.1007/s40273-020-00893-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christiansen ASJ, Møller MLS, Kronborg C, et al. Comparison of the three-level and the five-level versions of the EQ-5D. Eur J Health Econ. 2021;22(4):621–8. doi: 10.1007/s10198-021-01279-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan CW, He JY, Zhu YB, et al. Comparison of EQ-5D-5L and EORTC QLU-C10D utilities in gastric cancer patients. Eur J Health Econ. 2023;24(6):885–93. doi: 10.1007/s10198-022-01523-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan CW, Ma Q, Sun HP, et al. Tea consumption and health-related quality of life in older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(5):480–6. doi: 10.1007/s12603-016-0784-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo N, Liu G, Li M, et al. Estimating an EQ-5D-5L value set for China. Value Health. 2017;20(4):662–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Statistical Bulletin of the People’s Republic of China on National Economic and Social Development in 2021. China Stat. 2022;(03):9–26.

- 30.Moyo VM, Mukhina GL, Garrett ES, et al. Natural history of paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria using modern diagnostic assays. Br J Haematol. 2004;126(1):133–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ge M, Li X, Shi J, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors of Asian patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: results from a single center in China. Ann Hematol. 2012;91(7):1121–8. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1413-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu R, Li L, Li L, et al. Analysis of clinical characteristics of 92 patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: a single institution experience in China. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34(1):e23008. doi: 10.1002/jcla.23008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng WY, Sarda SP, Mody-Patel N, et al. Real-world Healthcare Resource utilization (HRU) and costs of patients with Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria (PNH) receiving Eculizumab in a US Population. Adv Ther. 2021;38(8):4461–79. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01825-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bektas M, Copley-Merriman C, Khan S, et al. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: current treatments and unmet needs. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(12–b Suppl):S14–20. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2020.26.12-b.s14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bektas M, Copley-Merriman C, Khan S, et al. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: patient journey and burden of disease. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(12–b Suppl):S8–14. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2020.26.12-b.s8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jang JH, Kim JS, Yoon SS, et al. Predictive factors of Mortality in Population of patients with Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria (PNH): results from a Korean PNH Registry. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31(2):214–21. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Röth A, Maciejewski J, Nishimura JI, et al. Screening and diagnostic clinical algorithm for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: Expert consensus. Eur J Haematol. 2018;101(1):3–11. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brodsky RA. How I treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2021;137(10):1304–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Latour RP, Mary JY, Salanoubat C, et al. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: natural history of disease subcategories. Blood. 2008;112(8):3099–106. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JW, Jang JH, Lee JH, HIGH PREVALENCE AND MORTALITY ASSOCIATED WITH THROMBOEMBOLISM IN ASIAN PATIENTS WITH PAROXYSMAL NOCTURNAL HEMOGLOBINURIA (PNH) et al. HAEMATOLOGICA-THE Hematol J. 2010;95:205–06. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee JW, Jang JH, Kim JS, et al. Clinical signs and symptoms associated with increased risk for thrombosis in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria from a Korean Registry. Int J Hematol. 2013;97(6):749–57. doi: 10.1007/s12185-013-1346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brodsky RA. How I treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2009;113(26):6522–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-195966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luzzatto L. PNH phenotypes and their genesis. Br J Haematol. 2020;189(5):802–5. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gulbis B, Eleftheriou A, Angastiniotis M, et al. Epidemiology of rare anaemias in Europe. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;686:375–96. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9485-8_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hill A, Rother RP, Wang X, et al. Effect of eculizumab on haemolysis-associated nitric oxide depletion, dyspnoea, and measures of pulmonary hypertension in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Br J Haematol. 2010;149(3):414–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yenerel MN, Muus P, Wilson A, et al. Clinical course and disease burden in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria by hemolytic status. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2017;65:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waheed A, Kaufhold S, Liu C-R, et al. A systematic literature review of clinical and economic outcomes for patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria in clinical trials and real-world settings. Blood. 2022;140:11451–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2022-167531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cella D, Sarda SP, Hsieh R, et al. Changes in hemoglobin and clinical outcomes drive improvements in fatigue, quality of life, and physical function in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: post hoc analyses from the phase III PEGASUS study. Ann Hematol. 2022;101(9):1905–14. doi: 10.1007/s00277-022-04887-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chatzileontiadou S, Hatjiharissi E, Angelopoulou M, et al. Thromboembolic events in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH): real world data of a Greek nationwide multicenter retrospective study. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1128994. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1128994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang TQ, Wu HY, Cai YF, et al. Researches on the Status of Life Quality of Chinese Population and its influencing factors based on EQ-5D-5L and SF-6D scales. Chin Health Service Manage. 2020;8(08):631–4. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fattizzo B, Cavallaro F, Oliva EN, et al. Managing fatigue in patients with Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria: a patient-focused perspective. J Blood Med. 2022;13:327–35. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S339660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Norström F, Virtanen P, Hammarström A, et al. How does unemployment affect self-assessed health? A systematic review focusing on subgroup effects. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1310. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thornton RL, Glover CM, Cené CW, et al. Evaluating strategies for reducing Health disparities by addressing the Social Determinants of Health. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(8):1416–23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:381–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim S, Love F, Quistberg DA, et al. Association of health literacy with self-management behavior in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(12):2980–2. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rani PK, Raman R, Subramani S, et al. Knowledge of diabetes and diabetic retinopathy among rural populations in India, and the influence of knowledge of diabetic retinopathy on attitude and practice. Rural Remote Health. 2008;8(3):838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lemes Dos Santos PF, Dos Santos PR, Ferrari GS, et al. Knowledge of diabetes mellitus: does gender make a difference? Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2014;5(4):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rother RP, Bell L, Hillmen P, et al. The clinical sequelae of intravascular hemolysis and extracellular plasma hemoglobin: a novel mechanism of human disease. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1653–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weitz I, Meyers G, Lamy T, et al. Cross-sectional validation study of patient-reported outcomes in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Intern Med J. 2013;43(3):298–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clarke DM, Currie KC. Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: a review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Med J Aust. 2009;190(S7):S54–60. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lamé IE, Peters ML, Vlaeyen JW, et al. Quality of life in chronic pain is more associated with beliefs about pain, than with pain intensity. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(1):15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Escalante CP, Chisolm S, Song J, et al. Fatigue, symptom burden, and health-related quality of life in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome, aplastic anemia, and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Cancer Med. 2019;8(2):543–53. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from PNH China, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under licence for the current study and so are not publicly available. The data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with the permission of PNH China.