Abstract

The absence of the right to health of migrants in transit has evolved into a significant global health concern, particularly in the border regions thus, this study aims to improve knowledge in this area by exploring the effects of the spatio-temporal liminal characteristics at borders in the achievement of the right to health of migrants in transit moving across two of the most transited and dangerous borders in Latin America: Colchane (Chile-Bolivia) and the Darién Gap (Colombia-Panamá). Through a qualitative descriptive multi-case study, we implemented 50 semi-structured interviews (n = 30 in Chile and n = 20 in the Darién/Necoclí) involving national, regional, and local stakeholders. The findings highlight that the fulfilment of the right to health of migrants in transit is hindered by liminal dynamics at the borders. These dynamics include closure of borders, (in)securities, uncertainty and waiting, lack of economic resources, lack of protection to all, liminal politics, and humanitarian interventions. These findings surface how the borders’ liminality exacerbates the segregation of migrants in transit by placing them in a temporospatial limbo that undermines their right to health. Our study concludes that not just the politics but also the everyday practices, relationships and social infrastructure at borders impedes the enjoyment of the right to health of distressed migrants in transit. The short-term humanitarian response; illicit dynamics at borders; migratory regulations; and border and cross-border political structures are some of the most significant determinants of health at these borderlands.

Keywords: Borders, Distress migration, Liminality, Migrants in transit, Right to health

1. Introduction

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) have undergone a transformation in numbers and migration dynamics over the last 30 years. While in 1990, LAC hosted 7 million migrants, by 2020, this figure doubled to 15 million, making it the world's fastest-growing region regarding human mobility (UNDP, 2023). In addition, economic migration during and after COVID-19, the massive exodus of Venezuelans to LAC countries, and intraregional and extracontinental migrants who transit especially to the United States (IOM, 2021) have turned some Latin American countries not only into destination points but also into transit regions (Seele et al., 2023). These dynamics have changed restrictions in countries’ migration policies, refugee legislation, and dynamics at the borders, affecting the protection of migrants’ rights (Freier and Doña-Reveco, 2022). The negative health impacts of both border restrictions and the lack of healthcare for vulnerable groups and irregular migrants are becoming a serious global health concern (Smith and Daynes, 2016), particularly in the borders between countries (Almeida Soares et al., 2023; López and Ryan, 2023).

Although we are aware of the limitations and potential dangers of labelling migrants under a single category or narrow definitions (Abubakar et al., 2018), we will use in this article the term distress migration as the best to describe the characteristics and reasons of migration for the cases presented in this study. According to Bhabha (Bhabha, 2018) distress migration refers to various situations where individuals are compelled to leave their homes due to desperation, vulnerability, and needs, from living circumstances that are experienced as unbearable or deeply unsatisfactory, even if they do not fit neatly into the more specific categories of refugees, survival migrants or forced migrants.

The transit period is one of the most difficult and risky in the migration cycle (Maldonado et al., 2018). The irregular conditions together with the political, security, and institutional dynamics in which distressed migrants are exposed during their journey put them at a continued level of vulnerability (Morales et al., 2010) and uncertainty (Pierson and Verguet, 2023). We sustain that transit in migration is not just the crossing of state borders or a simple “phase” of the migration process, but the interconnectedness of different cycles and movements between “here” and “there”, represented in a continuous mobility that is fragmented and non-linear (Bachelet, 2019; OHCHR, 2000; OHCHR, 2021). At borderlands, spatialities and temporalities merge in complex ways, changing the relationships between state, borders and territories (OHCHR, 2000). These dynamics intersect the discourses and practices of health at borders, producing different tensions that hinder the right to health at borderlands (Smith and Daynes, 2016; OHCHR, 2021). The terms “transit” also represents a denomination in time and movement, which reinforces timeless narratives, situating migrants in a liminal space (Düvell, 2012).

Restrictive migration policies, lack of protection for migrants in irregular migratory status and border closures have increased the vulnerability of distress migration in the last years (McAuliffe et al., 2022; Bojorquez et al., 2021). The unprecedented rise in the migration movements have turned border dynamics in LAC into spaces of mobility and immobility that influence the economic, social, and political dynamics of intraregional and extracontinental migrants (Iranzo, 2021; Freier and Castillo-Jara, 2022). On top of that, the closure of borders and political restrictions during and after COVID-19 have exposed distress migration to dangerous situations, increasing precarious forms of mobility. The control of the (in)ability of relief migrants to cross borders has become a geopolitical instrument that directly affects people's rights (Stoffelen, 2022 Mar). For instance, during COVID-19, a strong interaction between health, medical geography and border policies showed a critical health geopolitics that influenced directly in the dynamics of health, disease and health care of distressed migrants in transit (Sturm et al., 2021 Nov).

In this article, we define the right to health as a human right, indivisible and interdependent of other fundamental rights, which means more than the absence of disease, but having the conditions to enjoy physical and mental well-being (WHO, 2008). On this basis, we define the right to health as the “highest attainable standard of health”, which implies adequate medical care that includes all the social determinants of health (OHCHR, 2000). However, in complex contexts such as border regions, ensuring the fulfilment of the right to health poses significant challenges and mostly for the so-called “irregular migrants” (Smith and Daynes, 2016; OHCHR, 2021).

In Latin America, two growing risky borders are the Darién/Necoclí in Colombia and Colchane in Chile. Distress migration who cross these two borders are exposed to extreme natural and weather conditions (jungle and desert), different types of security issues (criminality and/or armed groups) (Cajiao et al., 2022; Roy, 2022; IOM, 2022) and the lack of state protection at the borders (Rangel, 2023; Cociña-Cholaky, 2021). Every day, between 300 and 400 and 600–800 distressed migrants transit through Colchane and the Darién, respectively (GIFMM, 2023; Scelza, 2021). From 2016 to 2022, 42 migrants have died crossing through Colchane and 226 through the Darién gap (Emol. Emol, 2022, IOM, 2022).

In 2021 and 2022 alone, 380,000 distressed migrants from 53 different countries crossed the Darién Gap (Gobierno de, 2023). A year after the COVID-19 pandemic started, a large number of migrants who were living in Chile mostly — Venezuelans and Haitians —, decided to make their second or even third migration movement to the United States in search of better social and economic opportunities (Yates, 2021). They crossed the entire continent, often using the Atacama Desert (Colchane) and the Darién Gap (Necoclí) route on their way to North America (IOM, 2020).

Along their journey, distress migration in Colchane and the Darién gap are exposed to different types of vulnerabilities and barriers to health care (Stefoni et al., 2023, Gabster and Jhangimal, 2021). They are exposed to health infections, dehydration, fractures, hypothermia, gastrointestinal problems, burns, skin problems, accidents, and even death (IOM, 2009, European Parliament 2017, HIAS, 2021). In other cases, due to security and border control, they are stranded at borders (Dowd, 2008), others are forced to return to their country of origin, exposing again to conditions of poverty, social exclusion, inadequate healthcare, and discrimination (Bojorquez et al., 2021). The effects of this pushback produce in a long-term large number of stressful, traumatic events and health problems (Vukčević Marković et al., 2023).

A report coined by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) shows how distress migration move along the same routes and use similar methods of transportation, often with the full or partial help of smugglers (IOM, 2009). On their journey, they may be exposed to political restrictions at the borders, abuses by smugglers, extortion, kidnapping by traffickers, physical mistreatment, and psychological and sexual abuses among other harms (Morales et al., 2010, UNHCR, 2016). Most of these migrants travel for a couple of weeks, months, or years, and some cases end up in a longer-term transit constantly disrupted by authorities, non-governmental groups, or criminal gangs, which directly have had an effect in the welfare of distressed migrants (Abubakar et al., 2018, Castañeda, 2023).

Security and safety threats along the migration journey, especially during the crossing of borders, place distressed migrants in transit in prolonged periods of insecurity and immobility (Iranzo, 2021). Neither the time spent in transit nor the destination point is clear for the distress migration, as it changes according to the migration policies at the borders and at the destination(s) (Düvell, 2012, Gil Everaert, 2020). Migrants can be constantly trapped at borders by a “bureaucratic time” of waiting, in which their rights are undermined by the closure of borders (Gil Everaert, 2020) and the lack of legal protection of the country of transit which can last for an indeterminate period of time (UNHCR, 2016, Tobar, 2021).

In this article, the analysis of borders go beyond the line of separation represented by an abstract regional division (Paasi, 2022). Borders turn on in a device that (im)mobilise distressed migrants in transit by influencing in the rhythm of their movement, showing the borders as a dispositive in which the permission to move becomes materialised (Axelsson, 2022). Therefore, the border control dynamics is not just represented at the spatio-temporal borderlands, but it goes beyond and throughout the migratory journey. This revels how health care is not just associated with the spatial dimensions of movement, but also with the temporalities of mobility trajectories (Cubides et al., 2022).

The transit through restrictive border areas place distress migration in a “state of limbo” (Jonzon et al., 2015 Jul) or “liminality” (Hartonen et al., 2022, Paynter, 2018 May 1, Fourny, 2013, Menjívar, 2006) that is displayed in the transition between the country of origin and the country of destination. The concept of liminality originally employed by Turner (Liminality and In, 1969) has been used recently by geographers, anthropologists, and social scientists to study transitions or as he coins it “thresholds” in cultural, spatial and temporal dynamics. Studies mainly in the geography discipline have shown how borders are seen as devices to analyse how temporospatial dynamics interfere with the lives of migrants (Axelsson, 2022, Paynter, 2018 May 1).

Our approach sheds light on new insights on the intersections between migration policy, health rights and border dynamics as an important triad for analysing health challenges at borders, exemplified as a liminal phase, where various spatiotemporal dynamics overlap (Stoffelen, 2022, Sturm et al., 2021). Liminality can be defined as the movement of a person or group away from a fixed social and/or cultural structure towards an intermediate position of ambiguity and indeterminacy (Del Real, 2022 Nov 18). According to Hartonen et al., the state of limbo is “legally constructed, bureaucratically machined, and spatially and temporally shifting derivative social condition caused by a lack of full political status” (Hartonen et al., 2022) (p. 1156). At borderlands, a legal liminality represents one of the greatest vulnerabilities of irregular distress migration (Menjívar, 2006, Del Real, 2022). According to Menjínvar, legal liminality refers to the grey area in-between status that places migrants in a condition of legal uncertainty that affects not only their individual, social network, and family dynamics but also their socio-cultural spheres (Menjívar, 2006). This uncertainty is controlled by borders regimes that define when, how and under which requirement, distressed migrants can be entitled of protection and rights (Smith and Daynes, 2016, Menjívar, 2006). Being in political liminality often exacerbates the vulnerability of migrants to communicable diseases, primarily attributable to overcrowded travel conditions and inadequate sanitary and hygienic practices, producing emotional distress (Vukčević Marković et al., 2023) and health problems (5,8,44). In this article, we argue how the borders’ liminality increases the vulnerabilities of distress migration, affecting levels of marginalisation, discrimination (Smith and Daynes, 2016) and health-related adversities, produced by the precariousness of migrants’ journey (Willen et al., 2019). The spaciotemporal conditions at borderlands show therefore a clear relationship between the liminal characteristics at borders and the right to health (McGuire and Georges, 2003).

A report by the United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) calls attention to the violations of many rights of migrants in transit and the need to fulfil this lack of protection under a human rights-based approach (UNHCR, 2016). International organisations and civil society attempt to fill this gap, supporting distressed migrants at these borders through humanitarian interventions (Hartonen et al., 2022, Muyskens, 2021 Jun), producing a “humanitarian frontier”, which remains even beyond the borders (Papataxiarchis, 2016). In other cases, the militarised, human trafficking, and security perspective at the borders (Smith and Daynes, 2016, Abubakar et al., 2018, Bojorquez et al., 2021) overlap with discourses about human rights and medical humanitarianism, leading to a wrong understanding of the meaning of the right to health (Willen et al., 2019).

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design

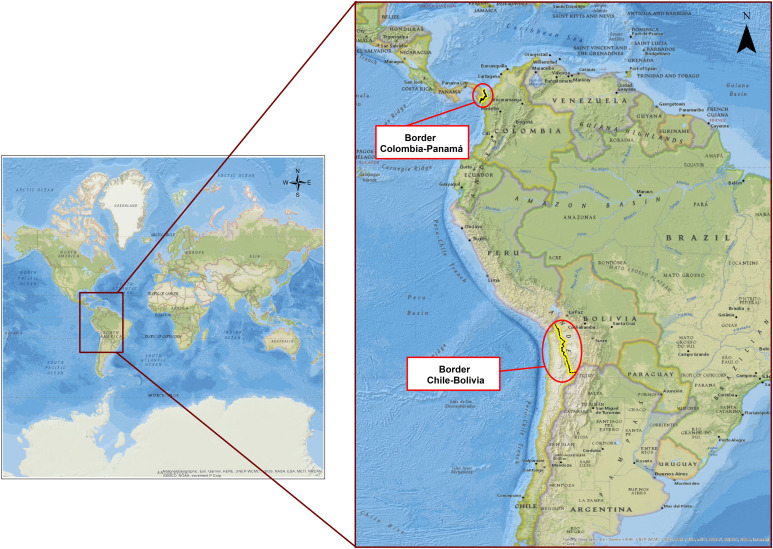

In this article, we used a qualitative descriptive multi-case study of two border regions in Latin America: Colchane in Chile and Necoclí/Darién in Colombia. These borders share significant similarities in terms of the type of migration and natural, social, and security conditions (See Map 1). We used an inductive approach to explore insights into real-world by analysing experiences, opinions and perception of a group of population that share similar characteristics (Moser and Korstjens, 2017). By using a multi-case study, we could explore in-depth the complex dynamics of borderlands in multi-case real-world settings (Crowe et al., 2011). This methodological approach enabled us to identify specific patterns that impact the realisation (or lack thereof) of the right to health for distress migration at border areas, offering valuable insights applicable to other regions with similar migratory characteristic.

Map 1.

Border Colombia-Panamá and Border Chile-Bolivia (ArcGis 8.1).

The Necoclí border stands as a small but significant municipality situated within the Urabá Antioqueño region nestled in the north-western part of Colombia, with approximately 65,000 inhabitants. This border gains importance due to its position within the Gulf of Urabá, creating a crucial link that connects South America with North America through the Darién gap, a swampy jungle spanning 11,896.5 km² (See Map 2). Within this challenging terrain, a variety of indigenous communities has established their homes, who contribute to the cultural richness of the area. Starting from 2019, the Darién Gap has transformed into one of the world's most recognised migration routes for those who aim as a destiny the United States. This route is characterised by its inhospitable terrain, hazardous rivers, and exceptionally lengthy journeys and the existence of criminal factions that are active within the region (Cajiao et al., 2022, Roy, 2022, Abé, 2021).

Map 2.

Capurganá, Gulf of Urabá, Colombia (ArcGis 8.1).

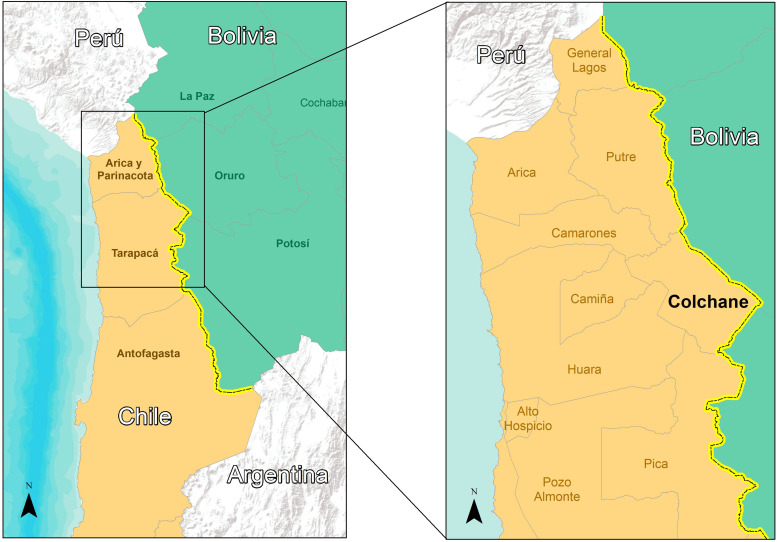

The Colchane border is a tiny city comprising 1629 persons that divides Bolivia and Chile (See Map 3). It has a formal point of entry and multiple informal crossing points. It is located in the Andean Altiplano in the Tarapacá region and is part of the Atacama Desert; therefore, all year it has extreme weather conditions. Furthermore, it has an elevation of almost 4000 m above the sea level, which makes the overall conditions very hard for vulnerable populations (i.e., children and pregnant women). The neighbouring Bolivian city is Pisiga, and the prevalent population is of the indigenous group Aimara. Starting in 2020, Colchane was key for migrants entering irregularly to Chile (Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes SJM 2020).

Map 3.

Arica, Parinacota and Tarapacá, Chile (ArcGis 8.1).

2.2. Participants and data collection

During 2021 and 2022, the co-authors of this manuscript (AJ and TRJ) conducted (n = 50) semi-structured in-depth interviews that lasted 45–60 min with members of international organisations, government, non-governmental organisations, and civil society, all engaged to varying degrees in the discourses and practices of health at the borders of Colchane and Necoclí, 30 in Chile and 20 in the Darién-Necoclí (See Table 1). The number of participants selected in each border area depended on their interest, availability, and the number of people who worked in the health field at borders, as well as on reaching thematic saturation. Our analytical framework was grounded in the United Nations’ definition of the right to health as the “highest attainable standard to physical and mental health” (OHCHR, 2000). The co-authors and the research partners did the interviews and the verbatim transcriptions and translations. All participants provided verbal or written consent forms. We did not report their names or other personal details to safeguard their anonymity. The study was approved by the Universidad del Desarrollo Ethics Committee (Chile 2021–90) and the Liebig University of Giessen (Germany AZ 167/21).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

| Category | Colchane | Darién/Necoclí | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 13 | 7 |

| Female | 17 | 13 | |

| Expertise/Institution | Politic/government | 7 | 7 |

| Academic | 8 | 1 | |

| Health practitioner | 7 | 1 | |

| International organisations and NGOs | 8 | 11 | |

2.3. Data analyses

Based on an inductive perspective, we classified the information in emerged categories produced by the participants’ testimonies and organised using the software MAXQDA (Saldana, 2021). We grouped the data into specific categories that helped us identify the main challenges in achieving the right to health of distress migration at borders. A codebook with the emergent themes was created by the first and corresponding authors and it was iteratively reviewed with the rest of the co-authors until all the team agreed on the final version that was used to code all the in-depth interviews. Considering the purpose of this article, we selected the following categories: borders, sociopolitical dynamics, and humanitarian frontier (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of categories.

| Categories | Sub-categories |

|---|---|

| Borders | Borders closure and (in)security Process of waiting and uncertainty |

| Socio-political dynamics | Regularity vs irregularity Lack of resources at the borders Discrimination and marginalisation Lack of protection to all |

| Humanitarian Frontier | The right to health as a humanitarian aid |

3. Results

3.1. Borders

3.1.1. Border closures and (in)securities

Border closures were the most common strategy used around the world to prevent the spread of the COVID-19. In LAC, more than 80 % of these countries had some restriction in their borders between 2021 and 2022 (McAuliffe, 2022). For instance, the Colombian government closed the border with Panama from March of 2020 to May 2021. However, by the end of May, the government of Panama decided to keep closed this border until July when they decided to restrict the entrance of migrant in 650 per day, leaving a total of 10,000 migrants stranded at this border between July and September 2021 (República de Panamá, 2021):

Last year we had more than 10,000 migrants stranded here. This was beyond our capacity; we are a town of 20,000 people. They had to sleep, cook, and go to the toilet on the beach. That was a big public health problem (Member Health Secretary, Necoclí Colombia).

Numerous studies have demonstrated how the closure of borders during and after the COVID-19 exacerbated the vulnerabilities faced by migrants (Freier and Castillo-Jara, 2022, IOM, 2020). In Colchane and the Darién, the closure of borders increased the use of irregular paths, the insecurity, and social and environmental risks of distress migration in transit:

The closure of the borders for migrants who were trying to enter to Chile, but also trying to go back to their country, increased the risks for human lives given the precariousness of the migration journey conditions (e.g., extreme weather conditions) but did not prevent them from migrating nor trying to cross the borders (SJM, International organisation, Antofagasta Chile).

Furthermore, the impact of border closures influenced the choices of numerous distressed migrants in transit to return to their countries of origin. This exacerbation of vulnerabilities subjected them to risks such as exposure to danger, social exclusion, inadequate healthcare, discrimination, and heightened poverty (Bojorquez et al., 2021). IOM reported that during COVID-19 hundreds of migrants were stranded in the Chilean-Bolivian border in Colchane, as well as over 2000 in the southern and northern borders of Panama in the Darién Gap (IOM, 2020):

Many of the Haitians who came last year decided not to continue their migratory route because there was no guarantee of reaching the United States, and many were repatriated in Mexico to Haiti. Many preferred to return to where they had their jobs before, such as Chile, Argentina or Brazil (Member of Pastoral Social, Apartadó Colombia).

The presumed security offered by border closures is not reflected in the effective decrease of criminal activities and control of armed groups (such is the case of paramilitary groups, especially the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia—AGC). In certain instances, these groups collaborate with smugglers and traffickers, further intensifying the challenges that must face distressed migrants:

Violence is always present in migrants’ journeys and this increased when the land borders were closed. Sometimes migrants relied on human smugglers or traffickers to cross safely given that the desert is a dangerous place. There is evidence of human trafficking and smuggling cases and those increased during the COVID-19 pandemic mainly due to border closeness (SJM, Santiago, Chile).

3.1.2. Process of waiting and uncertainty

Long-term transit during the migratory journey is related to insufficient financial resources to cover transport costs or to hire smugglers. Additionally, the adverse weather conditions, health-related problems, and security concerns place distressed migrants in high levels of vulnerability:

Migrants who arrived in Colchane during the worst crisis of the COVID-19 needed to wait a few days to be transported to other cities such as Iquique or Antofagasta. The weather in this region is extreme, so the heat during the day and the cold at night are unbearable. Sometimes, children needed to be prioritised because they had medical conditions that could not wait. Many families travelled with their animals and could not take them on the bus, so they had to leave them in the desert (Health provider, Arica Chile).

The process of “waiting” at borders represents for distressed migrants a “waste of time”. The dynamics of waiting lead to delays of agreements and disruption to control not just migrants’ time but their wellbeing (Axelsson, 2022, Jacobsen et al., 2021). During their “waiting”, migrants suffer from shortages of basic needs, such as water, shelter, and food, which have increased gastrointestinal diseases, skin health problems, high-risk pregnancies, and mental health disorders, putting their overall health at risk and jeopardising their continued migration. Migrants have to sleep on the streets or in tents, in some cases they have to survive by begging on the streets, creating an atmosphere of danger at the borders that interacts with the dynamics of smugglers and in some cases of criminal actors (Bojorquez et al., 2021, IOM, 2020).

The levels of uncertainty that distressed migrants are exposed turns into another determinant of health, which links directly with high levels of anxiety and mental health problems that they experience in their migration route (Müller, 2013). For instance, in Chile a member of the public sector mentioned the effects of migratory transit in the mental health of migrants:

We received families, who come sometimes withhold adults that had severe mental health issues because of the migration journey as well as other unattended chronic health issues (e.g., diabetes) (Public policy expert, Arica Chile).

The psychological services that distressed migrants in transit receive are catalogued as “psychological first aid”, which in most cases does not cover all the emotional needs of this population. According to a member of the Health Ministry in Colombia, limited mental health services are provided at the borders:

We need specific mental health programs for this population. We see that the migrant population is greatly affected emotionally and, obviously, the dynamics of migration itself make these health problems invisible. Here, we can see a population that has been in transit for more than 5 years and has not had an adequate mourning process to overcome this transit. It is not easy to leave their belongings, their work, their family, their territory and keep going in the search of a destination (Member Health Ministry, Bogotá Colombia).

3.2. Socio-Political dynamics

3.2.1. Regularity vs irregularity

Since 2015, new migratory policies emerged in LAC after the exodus of Venezuelans, creating in most cases, a temporal regularisation and social protection for Venezuelans who arrive in these countries. In Chile, migrants receive a temporary visa of two years to stay in the country. While they have this visa, either as holders or as dependents, they have the right to access health care on an equal basis with Chile's residents. In Colombia, a temporary protection to migrants from Venezuela is offered for 10 years, covering access to the social protections offered by the government. In Chile, individuals of foreign nationality, irrespective of their migratory status, will have access to the public health system if they lack valid documents or permits for staying in the country, in accordance with the provisions outlined in Article 6 and 10 of Law 18.469. However, in Colombia, migrants with an irregular status – mostly distressed migrants in transit – do not have access to public health services, though exceptions are made for a health emergency or if they are a priority population (children, pregnant women):

Pregnant women and children were prioritised since the beginning of the pandemic. The local health clinics made a tremendous effort to process the temporary local social security number (RUN) and to get their controls up to date. Some women were arriving without any prenatal control care or children with serious health issues like anaemia (Health provider, Antofagasta Chile).

Most of the distressed migrants who cross the borders of Colchane and the Darién do not have proper documentation, which hinders their ability to fully access the healthcare protections offered by the public health system. The boundary of irregularity interacts with the liminal politics to which distressed migrants are exposed, creating a diversity of vulnerabilities that influence their right to health. In terms of health services, migrants in Colombia who have not been regularised and are in transit do not have the right to enjoy health services, unless that their health problem represent an urgency:

The number of migrants who are chronic patients is increasing. However, in the framework of the health policy, they will not have access to health care because they are not registered. The government only guarantees them vital emergencies. Here there is a gap in the understanding of the law (Member international organisation, Bogotá Colombia)

In the case of Colchane, the lack of access to health care was due to the saturation of services, lack of information, as well as language and/or cultural barriers. Members of health services highlight the urgency of food subsidies and the creation of shelters, among other urgent measures (Tobar, 2021). One of the strategies that Chile has used is the “sanitary pairs” (duplas sanitarias), in which a social worker, nurse or technician work together to verify and monitor the health needs of the population. According to the interviews, the “sanitary pairs” benefit health surveillance, prevent the health system from collapsing, and help to identify cases from people who are afraid of going to the health centres:

The duplas sanitarias were a successful program in many ways as it screened population that may have never arrived at the local health clinics as most of them had issues with their migration status but also because the health system was collapsed so it could not receive such cases (Member international organisation, Santiago Chile).

3.2.2. Lack of resources at the borders

The migrants in transit have drastically changed the everyday life dynamics in Colchane and Necoclí in terms of job offers, cultural diversity, and political and funding priorities. These regions cannot cope alone with the massive migration that crosses their territory, as their physical and human infrastructure is not equipped to address all the challenges posed by distressed migrants. The distance of border regions from central political decisions, the absence of information and instruments to control health services, and the migratory dynamics and demographic conditions are some of the reasons for the lack of governmental attention at the borders:

The government allocates some resources for the provision of services for those people who have no documents, but in a very small proportion. As a third level municipality, we do not have the amount to support the health protection of migrants, but we have to assume it with the resources we have. We have been providing health care to a population of more or less 2400–2500 Venezuelans, some of whom are in transit; others have decided to stay here (Member Health Secretary Apartado, Colombia).

The lack of protection for both border residents and migrants in transit increased during COVID-19, which was covered by the intervention of humanitarian aid:

At the beginning of the pandemic, the attention at the border between Bolivia and Chile was minimal as it is a hostile location for bringing aid and human capital. Finding an extra doctor who wanted to stay and relocate to that region was complex. Furthermore, the resources allocated for the migrant humanitarian crisis arrived months after the pandemic. There were not enough shelters available to protect the recent arrival with the capacity to isolate COVID-19 cases, so, the international organisations were the ones who attended to the emergency at the beginning (Politics expert, Santiago de Chile).

3.2.3. Discrimination and marginalisation

Local communities have been affected by the large number of migrants who cross these borders, mostly in their access to social services. The increase in street vendors, crime, and begging are affecting public spaces, which is complemented by the number of migrants having to sleep on the streets. The local communities who do not profit economically from migrants reject the fact that they are crossing their territory, especially when the massive flow of distressed migrants has produced negative effects on their business, such as hotels and tourism companies:

Market trends, currency, and types of work have changed in Necoclí. The currency that now circulates the most is the dollar, which has created a huge inflation in the market. The market revolves around the needs that migrants will have in the jungle, jobs revolve around illegality, begging and human trafficking (Member international organisation, Necoclí Colombia).

Another aspect that affects the health protection of migrants at these borders is the level of discrimination from healthcare professionals and administrative staff towards the distressed migrants, as well as different kinds of obstacles to accessing health services such as cultural differences, language barriers, and lack of clear and accurate information:

Cultural aspects and discrimination play significant roles in understanding the obstacles to healthcare services. For example, we raise children differently and sometimes we judge, or we do not agree on how migrants teach or take care of their children. However, that should not be a barrier for providing health care or other social services (Health clinic staff, Iquique Chile).

3.2.4. Protection to all types of migrants

The types of migrants who now cross these borders also show a challenging reality for international agencies and governments. In the past, mostly men used to migrate alone or in groups and now, they are migrating with their families, pregnant women, elderly people and children. The situation of pregnant women in Colchane and Necoclí is dramatic during their transit. Some of them risk their life and the life of their babies by crossing these dangerous migratory routes:

The arrival of pregnant women in Chile with almost 40 weeks pregnant was something that we saw during the hardest months of the pandemic. Some of them were coming from other neighbour countries like Colombia and Peru and did not receive any prenatal care there. We prioritised the attention to these women, and we referred them to the proper channels of follow-up appointments so their children also could have all the health care needed (Director of Health Clinic, Antofagasta, Chile).

In Colchane and the Darién, a large number of children travel alone without adequate protection from the governments. In Colchane, UNICEF, Hogar de Cristo, and shelters that are part of the Ministry of Social Development have offered transitional centres for these children, offering them basic needs and social protection. In Necoclí, the Red Cross and UNICEF have offered special prioritisation to children by providing kits and psychosocial attention. However, these borders do not monitor the legal status of these children, nor do they track unaccompanied children.

In comparison to 2021, the rates of children and women migrating through the Darién was 37 % and 33 % higher respectively than in 2022 (Gobierno de Panamá, 2023). Only between January to August 2023, nearly 64,000 children under 18 crossed the Darién Gap (Pappier and Yates, 2023). The Red Cross in Necoclí reported:

At the beginning, the migration was mainly from men. When these men settled down, they returned and brought their family. Now, we see a lot of children and adolescents who are unaccompanied or who lost their parents on the way, or families who have dissolved because they leave their children in the hands of others. For example, I came here and told the neighbour to bring my child. In this situation, the level of responsibility of these neighbours is not the same (Member international organisation Bogotá, Colombia)

In the case of Colchane, migration is for family reunification purposes (i.e., people who have already entered the country return for their children, pregnant wives and older adults). There is also a tendency to see large families, children with health problems, pregnant women, and stateless children at this border, which is also a tendency in the Darién/Necoclí.

3.3. Humanitarian frontier

3.3.1. The right to health as a humanitarian aid

In the middle of the humanitarian crisis of Colchane and the Darién produced by the big number of distressed migrants who have crossed these borders between 2021 and 2022, the international infrastructure called for humanitarian emergency. Since then, various forms of humanitarian assistance, with a particular focus on emergency relief have been provided at the borders.

Now, the right to health of migrants at the borders is replaced by discourses of intermittency, temporality, and humanitarian dynamics provided by international organisations. At borders, multiple international organisations offer migrants “kits for the way” such as toiletries, baby kits, water purification tablets, tents, and backpacks. In addition, they offer humanitarian intervention in medical care, psychological first aid, and legal advice. These interventions framed the distress migration under a status of temporariness, labelling them as an otherness that belongs neither here nor there:

At the beginning of the pandemic, only the International Red Cross was treating injuries and giving away clothes, but it was not enough. Other NGOs had to close their doors because they could not isolate COVID-19 cases. It took a while to coordinate with the government and to receive public funding (Health provider, Arica Chile).

The approach of the humanitarian aid does not fulfil the political and practical framework of the right to health:

Health is a human right and not the provision of a service or humanitarian assistance. When one talks about health, one should understand that it is a human right in itself rather than a service detached from other rights (Member of international organisation, Necoclí, Colombia).

The massive presence of international organisations generates a humanitarian border that creates unique dynamics that are exclusive to border regions. Humanitarian practices come into conflict with governmental dynamics, resulting in the emergence of a parallel realm that diverges significantly from the everyday experiences of the local population residing at the borders:

In these regions that have suffered from state neglect, international organisations come to help migrants, but in many cases, they do not strengthen the capacity of governments to deal with these problems. Ideally, they should come and help us to reinforce our governments, such as in the areas of corruption and resource management (Member of Health Ministry, Bogotá Colombia).

4. Discussion and conclusions

In this article, we demonstrated how border restrictions, liminal socio-political dynamics at borders and humanitarian frontiers influence the achievement of right to health of distressed migrants. Our research underscores how exclusionary political patterns at the borders perpetuate the liminal nature of border areas by categorising migrants in transit as “non-persons” without legal status (Dal Lago et al., 2009), effectively absolving the state of any obligation towards their right to health (Inda and Dowling, 2013). Short-term humanitarian response, irregular dynamics, and the cross-border political structure often leave distressed migrants in transit in a spatio-temporal limbo that extends along their migratory journey, undermining their fundamental right to health. In some cases, their well-being is further affected by government structures and regulations that were originally intended to protect their rights (Abubakar et al., 2018). Our findings show that these dynamics go beyond physical borders, impacting migrants’ health throughout their journeys. This dynamic shows borders as spatially mobile arrangements which are both externalised and networked throughout borders (Axelsson, 2022).

According to Fourny (Fourny, 2013), the liminality of the borders enables the self-construction of ideas through different hybrid forms, which for the matters of this article are represented in a hybrid between documented and undocumented; international and national interventions, regularity and irregularity; borders restriction and socio-spatial resistances, among others. Distress migration in transit are in-between these hybrid forms, creating a disruption of an essential sense of security and integrity; a detachment of autonomy and freedom of choice; and with the inability to construct a future that lies ahead (Hartonen et al., 2022). The political liminality in which distressed migrants are exposed at borders increases levels of vulnerability of being treated as “irregular” people who have no rights (Angeleri, 2022). We observe that borders hinder the indivisibility and inalienability of the right to health by delineating, differentiating, and separating one territory from another, establishing rules that contradict the universality and equity of the right to health by prioritising regular migrants over irregular migrants (McGuire and Georges, 2003).

Our results, improve the knowledge of border studies by analysing the effects of spacio-temporal liminal dynamics at borders in achieving the right to health of distressed migrants in transit. We found that the migratory regulations and political structure turn into one of the most significant health determinants for distressed migrants in transit, showing clearly the liminal conditions at borders as health variables (McGuire and Georges, 2003). Political dynamics, the securitisation of borders, the closure of borders in the Necoclí/Darién and Colchane and the active presence of humanitarian interventions at the borders in which the right to health is merely related to emergency relief and not the protection of people's dignity (Moyn, 2020).

Findings of this study show tensions between human rights, politics at the borders, and humanitarian intervention discourses, being not necessarily mutually reinforced. The dynamics at borders show an apparent protection through the installation of a humanitarian infrastructure that offers temporal health solutions only by providing emergency relief and giving a subjective sense of health protection at borders, which lasts as long as distressed migrants are in these borders. While international organisations pretend partially to protect the rights of migrants in transit by using humanitarian perspectives, border policies delegitimise migrants as rights-holders by closing borders, establishing restrictive measures under a securitisation perspective (Jaramillo Contreras, 2023). In this context of liminality, humanitarian health aid overlap with health rights, forgetting that the two perspectives have different purposes (Barnett, 2011).

While specific political, social, and cultural factors may exist at each border, the overarching patterns outlined in this article help us comprehend the challenges involved in addressing the right to health of distressed migrants. This article has limitations. As it is a qualitative study conducted in two different geographical locations, we cannot generalise the findings to all the participants in these two border regions that are far away from each other. However, this multi-case study illustrates how public, international, and local actors are similarly involved in migration at borders, revealing common determinants that directly impact the right to health of distressed migration. Beyond the two border regions studied in this article, we can affirm that other border regions may present similar determinants that may impact the right to the highest attainable standard of health for distressed migrants in transit (Doocy et al., 2019; Bojorquez et al., 2022).

As conclusions, this study demonstrates that not only the politics, but also the everyday practices relationships, and social infrastructure exerted by institutions, resident communities, and irregular fractions at borders impede the enjoyment of distressed migrants’ right to health. Future research could build upon this foundation by investigating the impact of spatio-temporal liminal conditions on the universalisation of the right to health. Additionally, it is essential to explore the inherent tension between the inalienability of human rights and the practical restrictions at borders when applying the rights-based approach to healthcare.

Our study findings are relevant to current health policy discussions and practices in Latin American regions mainly for three reasons: (i) Latin American countries are based on a politic mostly centralised, which is represented in border's negligence from the side of the state (ii) Borders are perceived along of the time as points of security protection, but not as points of political and social articulation between countries (iii) the politics of migration in LAC demonstrate how the liminal condition of health protection in migrants represent an apparent protection covered by politics of exclusion. We identified how categories such as humanitarian aid, policies at borders and everyday social dynamics at borders are key indicators to consider in applying health public policies at borders.

Funding

This work was funded by the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft- DFG), (grant number 468252559) coordinated by MK, part of the University Justus-Liebig of Giessen. BC was funded by ANID Chile Fondecyt Regular 1201461. TRJ was funded by ANID Chile Fondecyt Regular 1231102, ANID ATE230065 and by ANID MILENIO N◦ NCS2021_013.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Andrea Carolina Jaramillo Contreras: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Báltica Cabieses: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Michael Knipper: Investigation, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. Teresita Rocha-Jiménez: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the members of the team in Latin America (Chile, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia) who were part of the project entitled “Migrant Health at the Borders in Times of COVID-19: Assessing Gaps, Needs and Priorities in the Implementation of Human Rights-based Health Policies and Programs in the Andean Region of Latin America”.

References

- Abé N. Crossing the Darién gap: a deadly jungle on the trek to America. Der Spiegel [Internet]. 2021 Oct 22 [cited 2023 Mar 1]; Available from: https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/crossing-the-darien-gap-a-deadly-jungle-on-the-trek-to-america-a-a5a01a5f-bd44-4d48-b115-0b481ae83906.

- Abubakar I, Aldridge R, Devakumar D, Orcutt M, Burns R, Barreto M, et al. The UCL–Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet Comm. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Almeida Soares D, Placeres A, Arcêncio RA, Fronteira I. Evidence on tuberculosis in migrants at Brazil's international borders: a scoping review. J. Migr. Health. 2023;7 doi: 10.1016/j.jmh.2023.100167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angeleri S. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2022. Irregular Migrants and the Right to Health [Internet]https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/irregular-migrants-and-the-right-to-health/BF98CA548D0F08125CCAC39CE958309C [cited 2024 Jan 17]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson L. Border time spaces: understanding the regulation of international mobility and migration. 2022;104(1):59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelet S. Looking for One's. Life”. Migr Soc. 2019 Jun 1;2(1):40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett M. Cornell University Press.; 2011. Empire of Humanity: a History of Humanitarianism Ithaca. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha J. Wiley; 2018. Can We Solve the Migration crisis? 140 p. [Google Scholar]

- Bojorquez I, Cabieses B, Arósquipa C, Arroyo J, Novella AC, Knipper M, et al. Migration and health in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Lancet. 2021 Apr;397(10281):1243–1245. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00629-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojorquez I, Sepúlveda J, Lee D, Strathdee S. Interrupted transit and common mental disorders among migrants in Tijuana, Mexico. Int. J. Social Psychiatry. 2022;68(5):1018–1025. doi: 10.1177/00207640221099419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajiao A, Tobo P, Restrepo MB. La Frontera del Clan. Fund Ideas Para Paz FIP. 2022.

- Castañeda H. Routledge; 2023. Migration and Health Critical Perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- Cociña-Cholaky M, Andrade-Moreno M. El gobierno de Chile debe abordar la crisis humanitaria desde el enfoque de los derechos humanos [Internet]. IDEHPUCP. 2021 [cited 2023 Jul 31]. Available from: https://idehpucp.pucp.edu.pe/analisis1/el-gobierno-de-chile-debe-abordar-la-crisis-humanitaria-desde-el-enfoque-de-los-derechos-humanos/.

- Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach. BMC. Med. Res. Methodol. 2011;11(100):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubides JC, Jorgensen N, Peiter PC. Time, space and health: using the life history calendar methodology applied to mobility in a medical-humanitarian organisation. Glob. Health Action. 2022 Dec 31;15(1) doi: 10.1080/16549716.2022.2128281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Düvell F. Transit migration: a blurred and politicised concept. Popul. Space Place. 2012;18(4):415–427. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Lago A, Orton M, Dal Lago A. IPOC; Milano: 2009. Non-persons: The exclusion of Migrants in a Global Society. 288 p. [Google Scholar]

- Del Real D. Seemingly inclusive liminal legality: the fragility and illegality production of Colombia's legalization programmes for Venezuelan migrants. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2022 Nov 18;48(15):3580–3601. doi: 10.1080/1369183x.2022.2029374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doocy S, Page KR, De La, Hoz F, Spiegel P, Beyrer C. Venezuelan migration and the border health crisis in Colombia and Brazil. J. Migr. Hum. Secur. 2019;7(3):79–91. Sep. [Google Scholar]

- Dowd R. Trapped in transit: the plight and human rights of stranded migrants [Internet]. UNHCR and ILO; 2008 [cited 2022 Nov 30] p. 1–30. (New Issues in Refugee Research Paper 156). Report No.: 156. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/research/working/486c92d12/trapped-transit-plight-human-rights-stranded-migrants-rebecca-dowd.html.

- Emol. Emol. 2022 [cited 2023 May 22]. Colchane acumula el 60% de las muertes de migrantes irregulares en frontera norte | Emol.com. Available from: https://www.emol.com/noticias/Nacional/2022/12/19/1081424/colchane-aumento-muertes-migrantes-frontera.html.

- European Parliament. Secondary movements of asylum seekers in the EU asylum system [Internet]. 2017. (Briefing). Available from: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2017/608728/EPRS_BRI(2017)608728_EN.pdf.

- Fourny MC. The border as liminal space. J. Alp Res. Rev. Géographie Alp. 2013;101(2) [Google Scholar]

- Freier LF, Castillo-Jara S. Human mobility and the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America. In: The Routledge History of Modern Latin American Migration. Andreas E. Feldmann, Xochitl Bada, Jorge Durand, Stephanie Schütze. New York: Routledge; 2022. p. 488.

- Freier LF, Doña-Reveco C. Introduction: latin American political and policy responses to Venezuelan displacement. Int. Migr. IOM. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- Gabster A, Jhangimal M. Rapid health evaluation in migrant peoples in transit through Darien, Panama: protocol for a multimethod qualitative and quantitative study. Ther. Adv. Infect. Dis. 2021;8:1–15. doi: 10.1177/20499361211066190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIFMM. Actualización semanal. Situación de personas refugiadas y migrantes en tránsito en Necoclí Antioquia. 2023 Jan.

- Gil Everaert I. Inhabiting the meanwhile: rebuilding home and restoring predictability in a space of waiting. J. Ethics Migr. Stud. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de Panamá. Irregulares en tránsito frontera Panamá [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.migracion.gob.pa/inicio/estadisticas.

- Hartonen VR, Väisänen P, Karlsson L, Pöllänen S. A stage of limbo: a meta-synthesis of refugees’ liminality. Appl. Psychol. 2022;71(3):1132–1167. [Google Scholar]

- HIAS. Rapid needs assessment Necoclí. 2021 p. 1–6.

- Inda JX, Dowling J. Standford University Press; 2013. Governing Inmigration Through crime: A reader; pp. 1–36. Introduction: Governing migrant illegality. J.A. Dowling&J.X. Inda. [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Irregular migration and mixed flows. IOM`s Approach. 2009. Report No.: 98 session.

- IOM. Tendencias Migratorias durante la Covid-19 en Centroamérica, Norteamérica, y El Caribe [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/tendencias_migratorias_durante_la_covid-19_en_centroamerica_norteamerica_y_el_caribe_-_oim_.pdf.

- IOM. Return and reintegration platform. 2020 [cited 2023 Jun 13]. Covid-19 Impact on Stranded Migrants. Available from: https://returnandreintegration.iom.int/en/resources/report/covid-19-impact-stranded-migrants.

- IOM . Buenos Aires and San José. OIM; 2021. Large movements of highly vulnerable migrants in the Americas. [Google Scholar]

- IOM. Office of the Special Envoy for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela. 2022 [cited 2023 Jun 13]. Venezuelan migrants and refugees defy deadly desert conditions on their journey to Chile. Available from: https://respuestavenezolanos.iom.int/en/stories/venezuelan-migrants-and-refugees-defy-deadly-desert-conditions-their-journey-chile.

- IOM. Missing migrant project [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Feb 12]. Available from: https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/americas.

- Iranzo A. Sub-Saharan migrants ‘in transit’: intersections between mobility and immobility and the production of (in)securities. Mobilities. 2021;16(5):739–757. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen CM, Karlsen MA, Khosravi S. Waiting and the Temporalities of Irregular Migration. First Edition. Routledge; 2021. Introduction: unpacking the temporalities of irregular migration; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo Contreras A. Routed Magazine. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 2]. The health protection of irregular migrants at the borders: the case of the Darién Gap. Available from: https://www.routedmagazine.com/post/health-protection-irregular-migrants-borders-darién-gap.

- Jonzon R, Lindkvist P, Johansson E. A state of limbo – in transition between two contexts: health assessments upon arrival in Sweden as perceived by former Eritrean asylum seekers. Scand. J. Public Health. 2015 Jul;43(5):548–558. doi: 10.1177/1403494815576786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López M, Ryan L. What are you doing here?’: narratives of border crossings among diverse Afghans going to the UK at different times. Front. Sociol. 2023;8 doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2023.1087030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liminality Turner V., In Communitas. Chicago Aldine Publishing; 1969. The Ritual process: Structure and Anti-structure; pp. 94–113. [Google Scholar]

- Müller C. Discussing mobility in liminal spaces and border zones: an analysis of Abbas Khider's »Der falsche Inder« (2008) and »Brief in die Auberginenrepublik« (2013). 2019 Nov 1 [cited 2022 Dec 12]; Available from: https://miami.uni-muenster.de/Record/e58d50fb-fa39-4b15-b541-f9f98606930a.

- Maldonado C, Martínez J, Martínez R. Protección social y migración Una mirada desde las vulnerabilidades a lo largo del ciclo de la migración y de la vida de las personas. CEPAL. 2018:120. [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe M, Freier LF, Skeldon R, Blower J. The great disrupter: covid19’s impact on migration, mobility and migrants globally. In: World Migr. Report 2022. M. McAuliffe and A. Triandafyllidou, Geneva; 2022.

- McAuliffe M, Triandafyllidou. World Migration Report 2022. McAuliffe, M. and A. Triandafyllidou. Geneva: International Organization For Migration (IOM); 2021.

- McGuire S, Georges J. Undocumentedness and liminality as health variables. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2003 Jul;26(3):185–195. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar C. Liminal legality: Salvadoran and Guatemalan immigrants’ lives in the United States. Am. J. Sociol. 2006;111(4):999–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Morales A, Acuña G, Wing-Ching K. Migración y salud en zonas fronterizas: Colombia y el Ecuador. CEPAL Ser. 2010;92:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 1: introduction. Eur. J. General Pract. 2017;23(1):271–273. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyn S. Humanitarianism and Human Rights A World of Differences? Cambridge University Press; 2020. Human Rights and Humanitarianization. [Google Scholar]

- Muyskens K. Intervening on behalf of the human right to health: who, when, and how? Hum. Rights Rev. 2021 Jun;22(2):173–191. doi: 10.1007/s12142-021-00620-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHCHR. CESCR general comment no. 14: the right to the highest attainable standard of health (art. 12). 2000. (adopted at the twenty-second session of the committee on economic, social and cultural rights, on 11 August 2000 (Contained in Document E/C.12/2000/4)).

- Ferrero L, Quagliariello C, Vargas AC, editors. Embodying Borders: A Migrant's Right to Health, Universal Rights and Local Policies [Internet] Berghahn Books; 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/j.ctv2tsxjts 1st ed.[cited 2024 Apr 8]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- Paasi A. Examining the persistence of bounded spaces: remarks on regions, territories, and the practices of bordering. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2022;104(1):9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Papataxiarchis E. Being ‘there’ At the front line of the ‘European refugee crisis. Anthropol. Today. 2016;32(3) [Google Scholar]

- Pappier J, Yates C. migrationpolicy.org. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 4]. How the treacherous darien gap became a migration crossroads of the Americas. Available from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/darien-gap-migration-crossroads.

- Paynter E. The liminal lives of Europe's transit migrants. Contexts. 2018 May 1;17(2):40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pierson L, Verguet S. When should global health actors prioritise more uncertain interventions? Harvard/MIT global health and population: lancet global health; 2023 p. e615–22. (Health Policy). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rangel JP. FIP. 2023 [cited 2023 Jul 24]. Los dilemas de la migración: el caso Necoclí. Available from: https://ideaspaz.org/publicaciones/opinion/2023-02/los-dilemas-de-la-migracion-el-caso-necocli.

- República de Panamá. Panamá cierra temporalmente fronteras con Colombia [Internet]. Noticias. 2021 [cited 2023 Aug 11]. Available from: https://mire.gob.pa/panama-cierra-temporalmente-frontera-con-colombia/.

- Roy D. Crossing the darién gap: migrants risk death on the journey to the U.S. [Internet]. 2022. Available from: https://www.cfr.org/article/crossing-darien-gap-migrants-risk-death-journey-us.

- Saldana J. Sage Publications; USA: 2021. Introduction: Latin American Political and Policy Responses to Venezuelan Displacement. An Introduction to Codes and Coding. Fourth Edition. Arizona State University. [Google Scholar]

- Scelza B. la diaria. 2021 [cited 2023 Jun 28]. Crisis migratoria en Chile: 17 muertos en lo que va del año en la frontera. Available from: https://ladiaria.com.uy/mundo/articulo/2021/10/crisis-migratoria-en-chile-17-muertos-en-lo-que-va-del-ano-en-la-frontera/.

- Seele A, Lacarte V, Ruiz Soto A, Chaves-González D, Mora MJ, Tanco A. migrationpolicy.org. 2023 [cited 2023 Aug 2]. In a dramatic shift, the americas have become a leading migration destination. Available from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/latin-america-caribbean-immigration-shift.

- Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes SJM. Dinámicas fronterizas en el norte de Chile el año 2020: Pandemia, medidas administrativas y vulnerabilidad migratoria [Internet]. Arica Chile: Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes; Report No.: Informe número 5. Available from: https://www.migracionenchile.cl/publicaciones-2020/.

- Smith J, Daynes L. Borders and migration: an issue of global health importance. Lancet Comment. 2016;4(February) doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00243-0. e85–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefoni C, Jaramillo M, Bravo A, Macaya-Aguirre G. Colchane. La construcción de una crisis humanitaria en la zona fronteriza del norte de Chile. Estud Front [Internet]. 2023 Feb 13 [cited 2023 Aug 2];24. Available from: https://ref.uabc.mx/ojs/index.php/ref/article/view/1070.

- Stoffelen A. Managing people's (in)ability to be mobile: geopolitics and the selective opening and closing of borders. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2022 Mar;47(1):243–256. [Google Scholar]

- Sturm T, Mercille J, Albrecht T, Cole J, Dodds K, Longhurst A. Interventions in critical health geopolitics: borders, rights, and conspiracies in the COVID-19 pandemic. Polit. Geogr. 2021 Nov;91 doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2021.102445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobar S. Sistematización de acciones y planes de fronteras. 2021.

- UNDP. 2023 [cited 2023 May 31]. Being a migrant in Latin America and the Caribbean | United Nations Development Programme. Available from: https://www.undp.org/latin-america/stories/being-migrant-latin-america-and-caribbean.

- UNHCR. Situation of Migrants in Transit [Internet]. 2016. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/tools-and-resources/ahrc3135-report-situation-migrants-transit.

- Vukčević Marković M, Bobić A, Živanović M. The effects of traumatic experiences during transit and pushback on the mental health of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2023;14(1) doi: 10.1080/20008066.2022.2163064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. The right to health. 2008. (Fact sheet 31).

- Willen SS, Knipper M, Abadía-Barrero CE, Davidovitch N. Syndemic vulnerability and the right to health. Lancet Migr. Sindemic. 2019;3:964–977. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30261-1. 389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates C. migrationpolicy.org. 2021 [cited 2023 Jun 12]. Haitian migration through the Americas: a decade in the making. Available from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/haitian-migration-through-americas.