Abstract

To investigate the effect of genetic selection on meat quality in ducks, twenty of each fast growth ducks (LCA) and slow growth ducks (LCC) selected from F6 generation of Cherry Valley ducks (♂) x Liancheng white ducks (♀) were analyzed for carcass characteristics, meat quality (physicochemical and textural characteristics), amino acid and fatty acid profiles at 7 wk. Results showed that live body weight, slaughter weight, eviscerated yield and abdominal fat percentage of LCA were significantly higher than those in LCC ducks (P < 0.01). Moreover, the average area and diameter of myofiber were larger in LCA than LCC ducks (P < 0.01). The breast and thigh muscles of LCA exhibited significantly lower water holding capacity and thermal loss compared with LCC ducks (P < 0.01). In addition, the content of nonessential amino acids (Glu, Asp, and Arg) in breast muscles and Asp, Ser, Thr, and Met in thigh muscles was higher in LCC than LCA ducks (P < 0.05). The proportion of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) in breast muscles of LCC was higher than LCA ducks (P < 0.05). However, the content of saturated fatty acids (SFA) in breast and thigh muscles of LCA was higher compared with LCC ducks (P < 0.05). The proportion of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) in thigh muscles was significantly higher in LCC compared with LCA ducks (P < 0.01). Finally, multiple traits were evaluated by applying principal component analysis (PCA) and the results indicated that PUFA and SFA in breast muscles of LCA played important roles in meat quality, followed by Warner-Bratzler shear force (WBSF) and MUFA. However, water holding capacity (WHC) had a dominant effect in meat quality of thigh muscles in both LCA and LCC ducks.

Key words: ducks, skeletal muscle, meat quality, myofiber type, amino acid profile

INTRODUCTION

Consumers preference for duck meat because of its mild flavor and texture, as well as its high level of digestible protein, polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamins (Cao et al., 2021). Liancheng white (LW) ducks, a rare local fowl breed in China, was known for its potential nutritional and medicinal properties (Zhou et al., 2022), but they have slow growth, small size and high production costs compared to Pekin ducks (Tang et al., 2023). Meanwhile, Cherry Valley ducks (CV) have a fast growth rate, high meat yield in the early stages, large sebum deposits, and are mostly used for duck meat production (Zhang et al., 2023). The previous study revealed that the hybrid progeny exhibited advantages over the parents (Huang et al., 2023). In this experiment, the F6 hybrid duck population (CV, ♂) x (LW, ♀) were selected based on growth rate at 6W: top 10% live body weight from 50,000 ducks was selected as the fast-growing group (LCA) and lowest 10% live body weight was selected as the slow-growing group (LCC), respectively.

There are significant variations in meat quality among different breeds of ducks, as well as among different lines of ducks within the same genetic background. A previous study analyzed the meat quality between lean and fat Pekin ducks and resulted in distinct differences in meat characteristics between the 2 duck lines (Ding et al., 2021). In addition, studies showed that the quality of meat from small-body ducks was superior to that of large-body meat ducks (Kwon et al., 2014). Reportedly, the breast meat of White Kaiya ducks had better antioxidant properties compared to CV ducks (Gao et al., 2023). In the compared line of Polish Pekin, tenderness of breast muscle in Danish and French Pekin was lower, but shear force was higher than that of Pekin and Mini ducks (hybrid of Pekin duck and wild mallard) (Kokoszyński et al., 2019). Therefore, the meat quality between LCA and LCC was investigated in this study.

The present study aimed to characterize the carcass traits, meat quality, fiber characteristics, amino acid and fatty acid profiles in breast and thigh muscles of LCA and LCC ducks. This study will provide objective evaluation of breeding achievements, directions for specialized breeding of meat ducks and provide a data basis for the utilization of excellent genetic resources of ducks.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement

All procedures were implemented according to the Local Experimental Animal Care Committee and approved by the ethics committee of Nanjing Agricultural University (NO: SYXK-2021-0014).

Experimental Design

At 7 wk of age, twenty male ducks were randomly selected from LCA and LCC for slaughtered. The carcass traits, meat quality (physicochemical and textural characteristics), amino acid and fatty acid profiles between 2 duck lines were measured. The difference and relationship between LCA and LCC was analyzed.

Breeding Management

In the present study, 10,000 of ducks (LCA and LCC) were reared in free-range pens with natural lighting for 7 wk. The temperature of the poultry house was adjusted as 32 to 34°C in the first week, and then was gradually reduced as 3 to 5°C per day, and decreased to about 20°C from the third week. Ducks were fed complete compound feed with the same nutritional value and free water.

Evaluation of Carcass Traits

Throughout the rearing and slaughter process, ducks were wing-tagged with numbered metal bands for identification. At 7 wk of age, 20 males with similar live weights from each group were slaughtered to determine their live weight, carcass and meat quality traits. Prior to slaughter, ducks underwent a 12 h feed withdrawal with access to water only. Body weight was recorded before slaughter, and carcass weight was taken after bloodletting, feather extraction, beak shell and foot skin removal. The breast and thigh muscles were meticulously dissected, accurately weighed. Briefly, semi eviscerated weight is the weight of the carcass (including head, neck and feet) after removing the trachea, esophagus, crop, intestines, spleen, pancreas and reproductive organs and stomach content. Eviscerated weight is based on semi-eviscerated removal of the heart, liver, glandular stomach, muscular stomach, abdominal fat (only lungs and kidneys are retained for internal organs) and retaining the head, neck, and feet (Chang et al., 2023).

Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

The muscle samples were cleaned with saline and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. Then, samples were embedded and cut at the thickness of 5-μm by using a microtome (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Five fields of each section were randomly selected for image acquisition under a microscope (Olympus BX50, Tokyo, Japan). Myofiber diameter (MFD) and myofiber cross-sectional area (CSA) was measured by using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software.

Immunohistochemical Staining

The immunohistochemistry staining protocol was performed as previously described with minor modifications (Kim et al, 2016). The sections (5 μm) were blocked with 10% normal goat serum (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Two primary antibodies, anti-fast myosin skeletal heavy chain (MYH1A, 1:1200, ab51263; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-slow myosin skeletal heavy chain (MYH7B, 1:4000, ab11083; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) were used, respectively. Sections were incubated with the primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, followed by incubating of secondary anti-body (goat anti-mouse IgG, 1:500, ab6728, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at 37°C for 30 min. After rinsing with PBS, streptomycin-antibiotic peroxidase solution was added and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Then, the sections were incubated in DAB staining solution and photographed using a NanoZoomer scanner (Hamamatsu, Sydney, Australia).

RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR Verification

Total RNAs were extracted from muscle samples via Trizol technique (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quality and purity were determined by utilizing the Nanodrop-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). One μg of each RNA sample was reverse-transcribed to cDNA after DNase treatment by using 5 X All-In-One RT MasterMix (Applied Biological Materials Inc. Richmond, BC, Canada). The cDNA was diluted 5-fold and quantitatively equalized for PCR amplification. The relative mRNA expression levels were determined by utilized the 2 × T5 fast qPCR Mix (TsingKe, Beijing, China) following the provided instructions. The qRT-PCR program was conducted on an Applied Biosystems (ABI) Quant Studio 5 system (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) according to the protocol: 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of 95°C for 2 s, 60°C for 1 min. The melting curve was 95°C for 15 s, 65°C for 1 min, and 95°C for 15 s. Each sample underwent triplicate testing. Relative expression was normalized with the β-actin using the comparative cycle threshold method (2−△△Ct) (Schmittgen and Livak 2008). The primer sequence was listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer information of qRT-PCR.

| Gene | GenBank accession | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myh7b | XM_027442963.2 | F:GAGTCGGCTGCTGGAGGAG R:GGCGTTCTTGCTCTTGGTCTC |

119 |

| Myh1a | NM_001013396.1 | F:GAACCCTCCCAAGTATGA R:GAGACCCGAGTAGGTGTAG |

124 |

| Myh1b | NM_204228.3 | F:GGGAGACCTGAATGAAATGGAG R:CTTCCTGTGACCTGAGAGCATC |

140 |

| β-actin | EF667345.1 | F: ATTGTCCACCGCAAATGCTTC R:AAATAAAGCCATGCCAATCTCGTC |

115 |

Physicochemical Analysis

pH. The portable pH-meter (Model PC 510, Cyber scan, Singapore) was calibrated in 2 calibration buffers (pH 4.01 and 7.0). The first measurement was taken at 1 h after slaughter, and the second measurement was taken at 24 h after slaughter and the samples were stored in refrigeration at 4°C. Three locations of the muscle tissues were randomly selected and the electrode head of the pH meter was inserted at a depth of about 1 cm for measurement.

Meat color. The color of the inner surface of each breast and thigh muscles were determined immediately after dissection using the reflectance spectrophotometer Minolta CR 310 Chroma Meter (Konica Minolta Sensing Business Unit, Osaka, Japan) equipped with a 50-mm reading head. The brightness (L*), red (a*) and yellow (b*) indices were measured by the chroma meter, which was calibrated as previous study (Gumułka and Połtowicz, 2020). The surface of muscle tissue was scratched with a scalpel, removing mixed fat. Then the color was measured at 3 randomly selected locations, and each location was repeated once.

Water-holding capacity. Five g of breast and thigh muscles were weighed and padded with 16 layers of filter paper on the top and bottom and pressurized with 343 N using a strain-controlled, no-limit manometer, held for 5 min and then removed, and the weight of the meat sample was weighed after pressing according to previous study (Weng et al., 2021). The weight of samples was normalized and expressed as percentage of exudated water in relation to the initial sample weight.

Drip loss. The cylindrical slice with 1 centimeter thick and 3 cm diameter of breast muscles was weighed as weight 1 (W1) and hung in a sealable plastic bag and stored at 4°C for 24 h. After carefully wiping the meat samples' surface layer with clean filter paper to extract any juice, the sample was weighed as weight 2 (W2). The product yield was the percentage of drop weight of the sample. Drip Loss = (W1-W2)/W1 × 100%.

Warner-Bratzler shear force. The tenderness of the cooked breast or thigh samples was determined as WBSF by a testing machine (Model 5542, Instron Engineering Corp, MA). The samples were cut into strips (4.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 cm each) parallel to the longitudinal orientation of muscle fibers (Wheeler et al., 1997). The equipment was adjusted to cut through the sample's center as the following speed: pre-test 4 mm/s, test speed 2 mm/s, post-test speed 10 mm/s, distance 30 mm, trigger force 5 g.

Thermal loss. Samples were cut into pieces of about 2 × 3 × 3 cm, the muscle tissue was weighed as weight 3 (W3). The samples placed in a boiling bag in a water bath at the temperature of 80°C and were removed from the bath when the internal temperature reached 75°C according to the previous study (Qiao et al., 2017). The sample was weighed after cooling to room temperature in cold water and then weighed as weight 4 (W4). Thermal loss = (W3-W4)/W3 × 100%.

Amino Acid Composition

The hydrolysis of the protein was carried out on 100 mg of a fresh meat sample with 10 mL of 6 M HCl in an ampoule glass sealed without air for 24 h at 110°C. After the hydrolysis, the solution was diluted with 250 mL of 0.2 M hydrochloric acid, followed by filtered through a 0.22 µm filter into a vial, and the amino acid content further analyzed according to previous study (Huang et al., 2023). The auto-analyzer systems used was L-8900 model (Hitachi, Japan).

Fatty Acid Composition

The measurement of fatty acid composition was conducted according to Ingrid Lima Figueiredo (Figueiredo et al., 2016) with appropriate adjustment. Firstly, 4.0 mL of NaOH (1.5 M in methanol) and homogenate was added into 1 g triturated sample. Then, test tubes were placed in an ultrasonic bath for 15 min. After alkaline reaction, 4.0 mL of H2SO4 (1.5 M in methanol) was added and the test tubes were placed in the ultrasonic bath for 12 min once again. 2 mL of n-hexane (Yonghua, Jiangsu) was added and the tubes were vortexed for 30 s and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. After shaking, the supernatant was taken into the sample bottle and sent to the automatic gas chromatography for determination. Chromatographic separation of fatty acid methyl esters was measured using a gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with a mass detector (MSD 5977A) with a 60 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm HP-88 column. The gas chromatography condition was similar to those used by Zhang Xin (Zhang et al., 2022).

Principal Component Analysis

The principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out according to previous studies (Ding et al., 2021; Gao et al., 2023). A comprehensive multi-index evaluation model of duck meat quality of different genetic backgrounds was established. The dimensional clustering of 7 meat quality parameters (MUFA, PUFA, essential amino acids [EAA], SFA, WBSF, WHC and flavor amino acids [FAA]) of 2 duck lines (LCA and LCC) was analyzed into 2 principal components based on PCA using SPSS software. These 7 parameters were split into 2 groups: the first group comprised the WBSF, WHC and PUFA; the second group included EAA and FAA. After standardizing the data for each trait, the characteristic root and variance contribution rates of each principal component were obtained.

Statistical Analysis

The data collected during the research on the composition of the carcass and meat quality of ducks were statistically characterized. The difference of carcass traits, meat quality, amino acid and fatty acid profiles between 2 duck lines (LCA and LCC) was analyzed by the student's independent-sample t-test. The results were plotted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software.

RESULTS

Analysis of Slaughter Performance in LCA and LCC Ducks

The results for live body weight and carcass traits of LCA and LCC are presented in Table 2. The live body weight, slaughter weight, wing weight, breast muscle weight, thigh muscle weight, eviscerated yield and abdominal fat percentage of 7-wk-old LCA was significantly higher than those of LCC (Table 2) (P < 0.01). LCA had higher semi eviscerated yield and breast muscle yield than LCC, but lower thigh muscle yield than LCC (Table 2) (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of slaughter performance between the LCA and LCC.

| Items | LCA | LCC | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live body weight (kg) | 2.50 ± 0.21A | 1.79 ± 0.29B | 0.000 |

| Slaughter weight (kg) | 2.29 ± 0.20A | 1.59 ± 0.21B | 0.000 |

| Wing weight (g) | 220.95 ± 35.79A | 156.96 ± 24.97B | 0.000 |

| Breast muscle weight (g) | 184.90 ± 31.22A | 108.99 ± 29.29B | 0.000 |

| Thigh muscle weight (g) | 202.86 ± 11.69A | 152.48 ± 18.60B | 0.000 |

| Semi eviscerated yield (%) | 79.80 ± 3.71a | 77.18 ± 3.22b | 0.022 |

| Eviscerated yield (%) | 71.44 ± 3.46A | 65.79 ± 3.05B | 0.000 |

| Breast muscles in carcass (%) | 10.32 ± 1.38a | 9.16 ± 1.65b | 0.021 |

| Thigh muscles in carcass (%) | 11.42 ± 0.97B | 13.04 ± 1.45A | 0.000 |

| Abdominal fat yield (%) | 2.39 ± 0.56A | 1.64 ± 0.74B | 0.002 |

Rows marked with different superscript letters differ significantly between groups (P < 0.05).

Rows marked with different superscript letters differ extremely significantly between groups (P < 0.01).

Morphological Analysis of Muscle Fibers in LCA and LCC Ducks

The fiber diameter and cross-sectional area were measured to compare the morphology of muscle fibers between LCA and LCC. The average area and diameter of myofiber in LCA ducks were significantly higher than those in LCC (Figures 1B and 1C) (P < 0.01). Moreover, the diameter of breast muscle fiber (24.60 ± 5.63μm) was remarkably smaller than that of thigh muscle fiber (42.18 ± 5.95μm) (Figure 1A) (P < 0.01).

Figure 1.

The morphology of myofibers in LCA and LCC. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining in breast muscles (BM) and thigh muscles (TM) from LCA and LCC. Magnification of 200 × was used (Bar = 100 μm). Analysis of muscle fiber diameter (B) and muscle fiber cross-sectional area (C) was conducted. Vertical bars represent mean ± standard error (n = 3). P < 0.01 is shown as **.

Analysis of Myosin Heavy Chain-Based Fiber Characteristics in LCA and LCC Ducks

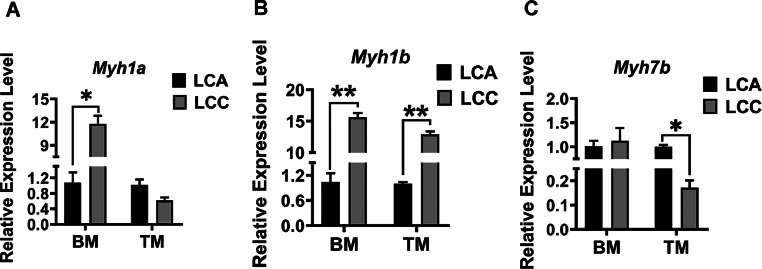

The type of myofiber in breast muscles and thigh muscles was compared between the LCA and LCC ducks (Figures 2). Breast muscles contained almost 100% glycolytic fibers and no oxidative fibers (Figures 2A), whereas thigh muscles contained both glycolytic and a few oxidative fibers in both LCA and LCC (Figures 2B). Results showed that breast muscles in LCA and LCC had more oxidizing muscle fiber (Figures 2). Next, the mRNA expression of myosin heavy chain-related genes isoform Myh7b (type I, slow-twitch), Myh1a (type IIb, fast-twitch) and Myh1b (type IIa, fast-twitch) in LCA and LCC were detected by qRT-PCR. As shown in Figure 3, the expression pattern of MyHC genes was different in breast and thigh muscles. The expression level of Myh1a was higher in breast muscles of LCC than LCA (Figure 3A) (P < 0.05), and the expression level of Myh1b in breast and thigh muscles of LCC was significantly higher compared to LCA (Figure 3B) (P < 0.01). In addition, the expression level of Myh7b in thigh muscles of LCC was lower than LCA (Figure 3C) (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

The type of muscle fibers in LCA and LCC. Immunohistochemical analyses for breast muscle (A) and thigh muscle (B) using anti-fast (MYH1A) and anti-slow (MYH7B) myosin skeletal heavy chain (Bar = 100 μm). Red arrows point to myofibers with positive immunostaining for glycolytic fibers; Green arrows point to myofibers with positive immunostaining for oxidative fibers.

Figure 3.

Relative mRNA expression of myosin heavy chain (MyHC) isoform genes in LCA and LCC. The mRNA expression of Myh1a, type IIb, fast-twitch (A), Myh1b, type IIa, fast-twitch (B) and Myh7b, type I, slow-twitch (C) was measured. The given values are reported as means ± standard error (n = 3). P < 0.05 is shown as *; p < 0.01 is shown as **.

Analysis of Physical Property of Meat in LCA and LCC Ducks

The physical properties of breast and thigh muscles are shown in Table 3. Results indicated that LCA had higher L* value, particularly in thigh muscles (Table 3) (P < 0.01). However, the b* value in breast and thigh muscles of LCA was significantly lower than that of LCC (Table 3) (P < 0.01). Breast muscles in LCA exhibited a higher shear force, pH and pH24 and significantly lower water-holding capacity, thermal and drip loss compared to LCC (Table 3) (P < 0.01). Thigh muscles in LCA showed significantly lower water-holding capacity, a* value, b* value, thermal loss and significantly higher pH, pH24, L* value and Warner-Bratzler shear force than those of LCC (Table 3) (P < 0.01).

Table 3.

Physicochemical characteristics of breast and thigh muscle in LCA and LCC.

| Items | LCA |

LCC |

P value |

LCA |

LCC |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast muscles | Thigh muscles | |||||

| pH | 6.12 ± 0.30A | 5.92 ± 0.10B | 0.010 | 6.43 ± 0.20A | 6.22 ± 0,20B | 0.002 |

| pH24 | 5.82 ± 0.11a | 5.74 ± 0.11b | 0.030 | 6.35 ± 0.15A | 5.93 ± 0.26B | 0.000 |

| L* | 34.00 ± 6.23 | 31.77 ± 3.26 | 0.173 | 35.64 ± 5.58A | 28.31 ± 3.20B | 0.000 |

| a* | 16.15 ± 3.68 | 15.48 ± 2.03 | 0.488 | 14.03 ± 2.44B | 17.08 ± 2.04A | 0.004 |

| b* | 10.95 ± 2.09b | 12.76 ± 2.72a | 0.027 | 13.40 ± 2.93B | 17.82 ± 2.02A | 0.000 |

| WHC (%) | 31.10 ± 4.82B | 42.58 ± 4.47A | 0.000 | 27.48 ± 3.92B | 39.50 ± 3.90A | 0.000 |

| Thermal loss (%) | 18.29 ± 2.08B | 28.63 ± 2.17A | 0.000 | 17.23 ± 2.05B | 20.88 ± 3.72A | 0.000 |

| WBSF (N) | 25.64 ± 7.01 | 22.40 ± 2.91 | 0.068 | 30.23 ± 5.74A | 25.48 ± 2.44B | 0.002 |

| Drip loss (%) | 3.10 ± 1.52B | 6.00 ± 2.65A | 0.001 | |||

WHC, water holding capacity; WBSF, Warner–Bratzler shear force.

Rows marked with different superscript letters differ significantly between groups (P < 0.05).

Rows marked with different superscript letters differ extremely significantly between groups (P < 0.01).

Analysis of Amino Acid Profile in LCA and LCC Ducks

The amino acid composition of breast and thigh muscles in LCA and LCC are shown in Table 4. The amount of EAA in breast and thigh muscles of 7-wk-old male ducks was determined to be between 7.27 and 9.00 mg/g (Table 4). In this study, 16 amino acids detected in muscle tissue, and glutamic (Glu), aspartic (Asp), lysine (Lys) and leucine (Leu) showed the highest concentration, of which Glu and Asp were belonging to flavor amino acids and Lys and Leu were belonging to EAA (Table 4). The content of serine (Ser), glycine (Gly) and alanine (Ala) in breast muscles of LCC was significantly higher than that of LCA (Table 4) (P < 0.01). The content of Glu, Asp and arginine (Arg) in breast muscles of LCC was higher than that of LCA (Table 4) (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the content of Asp, Ser, threonine (Thr) and methionine (Met) in thigh muscles of LCC was higher than that of LCA (Table 4) (P < 0.05).

Table 4.

Amino acids composition of breast and thigh muscle in LCA and LCC (mg/g).

| Items | LCA |

LCC |

P value |

LCA |

LCC |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast muscles | Thigh muscles | |||||

| Nonessential amino acid | ||||||

| Glutamic acid (Glu) 1 | 3.04 ± 0.82b | 3.90 ± 0.56a | 0.040 | 3.14 ± 0.53 | 3.62 ± 0.28 | 0.063 |

| Aspartic acid (Asp)* | 1.86 ± 0.4b | 2.41 ± 0.36a | 0.030 | 1.91 ± 0.30b | 2.22 ± 0.18a | 0.043 |

| Arginine (Arg) | 1.35 ± 0.37b | 1.74 ± 0.26a | 0.040 | 1.40 ± 0.26 | 1.58 ± 0.16 | 0.141 |

| Alanine (Ala)* | 1.15 ± 0.23B | 1.58 ± 0.24A | 0.005 | 1.23 ± 0.16 | 1.43 ± 0.17 | 0.059 |

| Glycine (Gly)* | 0.83 ± 0.17B | 1.31 ± 0.33A | 0.005 | 0.92 ± 0.13 | 1.16 ± 0.27 | 0.073 |

| Serine (Ser) | 0.78 ± 0.13B | 1.09 ± 0.16A | 0.002 | 0.85 ± 0.11b | 1.01 ± 0.09a | 0.014 |

| Essential amino acid (EAA) | ||||||

| Lysine (Lys) | 1.84 ± 0.53 | 2.27 ± 0.35 | 0.097 | 1.88 ± 0.32 | 2.09 ± 0.16 | 0.155 |

| Leucine (Leu) | 1.72 ± 0.49 | 2.14 ± 0.34 | 0.086 | 1.73 ± 0.29 | 1.95 ± 0.16 | 0.116 |

| Valine (Val) | 0.99 ± 0.29 | 1.21 ± 0.18 | 0.126 | 1.01 ± 0.16 | 1.09 ± 0.10 | 0.268 |

| Isoleucine (Ile) | 0.95 ± 0.31 | 1.13 ± 0.18 | 0.190 | 0.94 ± 0.17 | 1.05 ± 0.09 | 0.190 |

| Phenylalanine (Phe)* | 0.85 ± 0.25 | 1.06 ± 0.18 | 0.091 | 0.86 ± 0.14 | 0.97 ± 0.09 | 0.133 |

| Tyrosine (Tyr)* | 0.74 ± 0.22 | 0.89 ± 0.12 | 0.133 | 0.75 ± 0.13 | 0.84 ± 0.07 | 0.129 |

| Threonine (Thr) | 0.92 ± 0.22b | 1.20 ± 0.18a | 0.024 | 0.96 ± 0.14b | 1.11 ± 0.10a | 0.048 |

| Histidine (His) | 0.57 ± 0.15 | 0.73 ± 0.14 | 0.066 | 0.57 ± 0.08 | 0.63 ± 0.05 | 0.126 |

| Methionine (Met) | 0.49 ± 0.12 | 0.64 ± 0.14 | 0.051 | 0.51 ± 0.10b | 0.63 ± 0.05a | 0.019 |

| Cystine (Cys) | 0.14 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.172 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.820 |

| Ʃ EAA | 7.27 ± 2.08 | 9.00 ± 1.40 | 0.092 | 8.09 ± 1.70 | 8.23 ± 0.70 | 0.832 |

| Ʃ FAA | 7.31 ± 1.92b | 9.57 ± 1.41a | 0.027 | 8.40 ± 1.54 | 8.63 ± 0.82 | 0.714 |

Rows marked with different superscript letters differ significantly between groups (P < 0.05).

Rows marked with different superscript letters differ extremely significantly between groups (P < 0.01).

Represents flavor amino acids. ∑EAA, sum of Leu, Lys, Val, Phe, Ile, Tyr, Thr, His, Met, and Cys. ∑FAA, sum of Glu, Pro, Ala, Ser, Gly, and Ile. Specially, Glu, glutamic acid; Asp, aspartic acid; Arg, arginine; Pro, proline; Ala, alanine; Ser, serine; Gly, glycine; Leu, leucine; Lys, lysine; Val, valine; Phe, phenylalanine; Ile, isoleucine; Tyr, tyrosine; Thr, threonine; His, histidine; Met, methionine; Cys, cysteine

Analysis of Fatty Acid Profile in LCA and LCC Ducks

The fatty acid compositions of breast and thigh muscles in LCA and LCC are expressed in Table 5. The composition of fatty acids of breast muscles in both LCA and LCC were oleic acid (C18:1n9c), palmitic acid (C16:0), linoleic acid (C18:2n6c) and stearic acid (C18:0), which accounted for more than 80% of the total fatty acids. The content of PUFA in breast muscles of LCC was higher than LCA (Table 5) (P < 0.05). However, the SFA in breast muscles of LCA was higher compared with LCC (Table 5) (P < 0.05), which was mainly influenced by palmitic (C16:0) and stearic acid (C18:0). The same trend was observed in thigh muscles between LCA and LCC (Table 5). Results suggested that the content of MUFA in thigh muscles of LCC was significantly higher compared with LCA (Table 5) (P < 0.01). But, the content of SFA in thigh muscles was significantly lower compared to LCA (P < 0.01). The content of the following fatty acids was significantly higher in thigh muscles of LCA compared with LCC: lauric (C12:0), pentadecanoic (C15:0), heptadecanoic (C17:0), arachidic (C20:0), eicosadienoic (C20:2) and arachidonic (C20:4n6) (Table 5) (P < 0.01).

Table 5.

Major fatty acids composition (% of total FA) of breast and thigh muscle in LCA and LCC.

| Fatty acids | LCA |

LCC |

P value |

Fatty acids | LCA |

LCC |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast muscles | Thigh muscles | ||||||

| C12:0 | 0.56 ± 0.11 | 0.57 ± 0.05 | 0.943 | C12:0 | 0.76 ± 0.11A | 0.38 ± 0.05B | 0.008 |

| C14:0 | 0.50 ± 0.06b | 0.72 ± 0.05a | 0.019 | C14:0 | 0.94 ± 0.32a | 0.63 ± 0.04b | 0.015 |

| C15:0 | 0.08 ± 0.004A | 0.05 ± 0.004B | 0.001 | C15:0 | 0.09 ± 0.01A | 0.06 ± 0.00B | 0.001 |

| C16:0 | 24.51 ± 0.19A | 22.98 ± 0.16B | 0.000 | C16:0 | 24.46 ± 1.37a | 20.42 ± 0.40b | 0.016 |

| C17:0 | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.325 | C17:0 | 0.23 ± 0.01A | 0.16 ± 0.01B | 0.000 |

| C18:0 | 14.40 ± 0.81 | 12.34 ± 0.60 | 0.068 | C18:0 | 12.82 ± 0.58 | 11.88 ± 0.64 | 0.291 |

| C20:0 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.169 | C20:0 | 0.19 ± 0.01 A | 0.13 ± 0.01B | 0.000 |

| C24:0 | 0.32 ± 0.05a | 0.19 ± 0.02b | 0.014 | C24:0 | 9.07 ± 1.24 | 8.07 ± 0.85 | 0.514 |

| Ʃ SFA | 52.93 ± 2.37a | 44.79 ± 2.46b | 0.028 | Ʃ SFA | 48.51 ± 1.26A | 33.71 ± 0.35B | 0.000 |

| C16:1 | 1.01 ± 0.16b | 1.57 ± 0.06a | 0.014 | C16:1 | 2.10 ± 0.33 | 2.02 ± 0.17 | 0.834 |

| C17:1 | 0.92 ± 0.09A | 0.45 ± 0.10B | 0.007 | C14:1 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.212 |

| C18:1n9t | 0.13 ± 0.01b | 0.20 ± 0.03a | 0.068 | C18:1n9t | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.079 |

| C18:1n9C | 24.97 ± 2.28 | 26.23 ± 1.75 | 0.038 | C18:1n9C | 24.15 ± 2.04B | 33.30 ± 0.94A | 0.001 |

| C24:1n9 | 0.85 ± 0.12 | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 0.134 | C24:1n9 | 0.68 ± 0.06 | 0.64 ± 0.08 | 0.632 |

| Ʃ MUFA | 25.64 ± 2.04 | 29.93 ± 2.42 | 0.192 | Ʃ MUFA | 27.26 ± 1.84B | 35.56 ± 1.08A | 0.002 |

| C18:2n6C | 17.69 ± 0.48B | 22.24 ± 0.82A | 0.001 | C18:2n6C | 22.21 ± 1.42 | 21.16 ± 0.32 | 0.504 |

| C18:3n6 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.643 | C18:3n6 | 0.16 ± 0.08 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.281 |

| C20:2 | 0.72 ± 0.05a | 0.49 ± 0.07b | 0.021 | C20:2 | 0.46 ± 0.02A | 0.35 ± 0.02B | 0.003 |

| C20:3n6 | 0.83 ± 0.11 | 0.62 ± 0.08 | 0.160 | C20:3n6 | 0.38 ± 0.08 | 0.30 ± 0.03 | 0.423 |

| C20:4n6 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.159 | C20:4n6 | 0.14 ± 0.01A | 0.09 ± 0.00B | 0.000 |

| C22:6n3 | 1.11 ± 0.09a | 0.81 ± 0.08b | 0.041 | C22:6n3 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.076 |

| Ʃ PUFA | 19.92 ± 0.39b | 23.46 ± 1.26a | 0.020 | Ʃ PUFA | 23.50 ± 1.37 | 22.45 ± 0.81 | 0.875 |

Abbreviations: SFA, saturated fatty acid include C12:0, C14:0, C15:0, C16:0, C17:0, C18:0, C20:0, and C24:0; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acid include C16:1, C17:1, C18:1n9t, C18:1n9c, andC24:1n9; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid include C18:2n6, C18:3n3, C18:3n6, C20:2, C20:3n6, C20:4n6, and C22:6n3.

Rows marked with different superscript letters differ significantly between groups (P < 0.05).

Rows marked with different superscript letters differ extremely significantly between groups (P < 0.01).

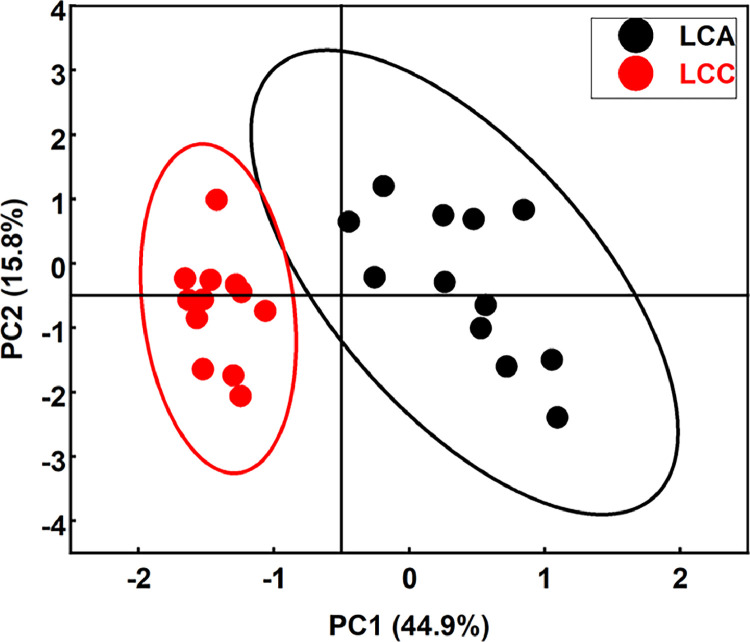

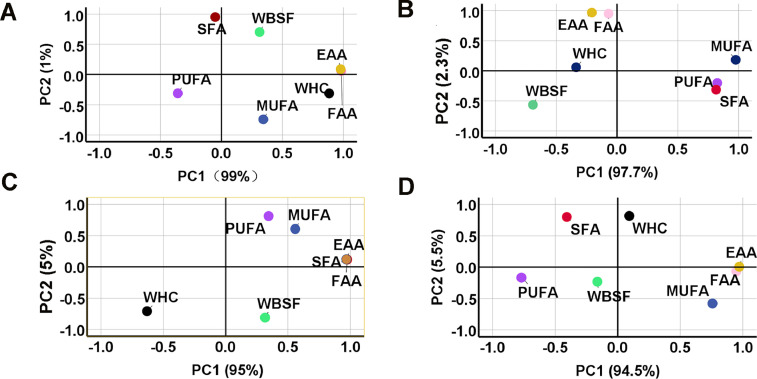

PCA of Nutritional Composition in LCA and LCC Ducks

As shown in Figure 4, LCA and LCC were clustered together and the range of the 2 lines had a clear demarcation line. The variance contribution rate of the first and second principal components were 44.9% and 15.8%, respectively (Figure 4). The first group included the 5 meat-traits (PUFA, SFA, MUFA, WHC, and WBSF) and the second group included the remaining 2 traits (EAA and FAA). PUFA and SFA in breast muscles of LCA may play an important role in meat quality, followed by WBSF and MUFA (Figure 5A). In addition, WHC may have a dominant effect in thigh muscles both in LCA and LCC (Figures 5C and 5D). In breast muscles of LCC, the MUFA, PUFA, and SFA explained the highest factor score among the 7 quality parameters (Figure 5B).

Figure 4.

Projection of one individual of each breed in the plane defined by the 2 principal components. Each black dot represents 1 individual of LCA and each red dot represents 1 individual of LCC.

Figure 5.

Different colored dots represent different meat quality parameters. PCA scores plot of meat traits for breast muscle in LCA (A) and LCC (B), and thigh muscle in LCA (C) and LCC (D). EAA, essential amino acid; FAA, flavor amino acid; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acid; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; SFA, saturated fatty acid; WBSF, Warner-Bratzler shear force; WHC, water holding capacity.

DISCUSSION

LCA and LCC are new breeding lines with Cherry Valley ducks and Liancheng white ducks. After F6 hybrid population selection, LCA and LCC show significant differences in carcass traits, meat quality, and flavor. Slaughter performance is an important index to evaluate the performance in livestock and poultry (Huang et al., 2016). In addition, previous study showed differences in carcass and meat quality of 2 Pekin duck lines (Ding et al., 2021). The results of this study showed that the slaughter yield of LCA and LCC were 91.47% and 88.52% respectively, and the evisceration yield of LCA and LCC were 71.44% and 65.79%. Slaughter performance was strongly influenced by live weight, and all slaughter indices of LCA were significantly higher than those of LCC, which indicated that LCA had fast growth rate and high meat yield.

Muscle fiber characteristics are closely related to fresh meat quality in poultry (Lee et al., 2010). This study found that the average area and diameter of myofiber in breast and thigh muscles of LCA were significantly higher than those in LCC. A previous study showed that there was a significant positive correlation between muscle fiber diameter and shear force (Chen et al., 2007). The results of the present study supported these findings. The fiber type composition within skeletal muscles directly influenced meat quality attributes, such as color, tenderness, pH, and various other key factors (Mo et al., 2023). Reports suggested that the main fiber type was type IIB, IIA and type I in poultry (Lee, Joo and Ryu 2010; Lefaucheur 2010). Our results showed that breast muscles in both LCA and LCC were almost composed of fast-twitch fibers, and that the thigh muscles contained both fast-twitch and slow-twitch muscle fibers, which was consistent with the previous studies (Weng et al., 2022). It seems that the above differences were caused by different muscle tissue locations (Weng et al., 2021). The various types of muscle fibers have different biological functions, slow-twitch oxidative fibers primarily rely on fat oxidation to produce energy, while fast-twitch glycolytic fibers quickly produce energy through glycolysis (Lefaucheur, 2010; Choe et al., 2008). As a result, muscles with oxidative fibers taste better and contain more fat than muscles with more fast-twitch glycolytic fibers. In this experiment, the expression level of Myh1b in the breast and thigh muscles of LCC was significantly higher compared to LCA, Myh1b stands for type IIa, fast-twitch glycolytic fibers, suggesting that LCC had better taste compared with LCA ducks.

In the present study, LCA had much higher breast muscle yield than LCC ducks, and also had differences in various muscle quality-related traits between LCA and LCC. The value of pH typically ranged from 5.6 to 6.5 after slaughter in poultry muscle (Kokoszyński et al., 2022), and the pH value in breast muscles was lower than thigh muscles (Heo et al., 2015). Coincidence with previous study, this study showed that pH value in breast muscles ranged from 5.9 to 6.1, while pH value in thigh muscles was 6.2 and 6.4. The a*-value is commonly used to indicate the freshness of muscle, while the L*-value is negatively correlated with the meat's water-holding capacity (Joo et al., 2013). We found that LCA had higher L* value in breast and thigh muscles than LCC, which was in agreement with the results of reported meat color values of duck meat.

Amino acids are important components of proteins, and studies have shown that different amino acid species have different metabolic functions and nutritional value in meat (Zhang et al., 2023). In addition, the content of amino acids has an important relationship with flavor (Ardö, 2006), Glu is a multifunctional amino acid that plays a key role in central neurotransmission and intermediate carbohydrate metabolism (Ghirri and Bignetti 2012). In this study, the content of Glu and Asp in breast and thigh muscles of LCC was higher than those of LCA, which indicating LCC was tasty. A recent study suggested that the accretion of amino acids in fast-growing birds was relatively different from that in slow-growing birds (Tran et al., 2021). Moreover, the amino acids here took similar orders of magnitude with a previous study (Cao et al., 2021). Fatty acids in muscle are among the major factors that influence quality of meat (Haraf et al., 2021), the content and composition of fatty acids affect the meat's color, juiciness, flavor and nutritional value, among other attributes (Kamal et al., 2022). Saturated fatty acids (SFA) are negatively correlated with flavor, with myristic acid (C14:0) and palmitic acid (C16:0) being detrimental to human health (Katan et al., 1994; Venn et al., 2020). The content of myristic acid in the breast muscles of LCA was significantly higher than that of LCC. It was found PUFA in lipids dissolved muscle fiber bundles during oxidation, which improved meat quality, and generate taste compounds, such as aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, esters, and aliphatic compounds, through a series of oxidative processes (Benet et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2022). Similarly, the content of linoleic and oleic acid in the breast muscles of LCC were significantly higher than those of LCA, and PUFA content of LCC was higher than LCA, indicating that LCC had well flavor. In terms of fatty acid composition and content, LCC was found to be better compared with LCA.

Finally, PCA was performed to explore possible clustering trends and the most important variables of meat quality parameters of LCA and LCC. These data showed that PUFA and SFA of breast muscle in LCA and LCC played important roles in meat quality. PCA between CV and White Kaiya ducks showed that EAA and FAA could be defined as the first cluster, explaining the highest weight (factor score) among the 7 quality parameters (Gao et al., 2023). There are also differences in meat quality traits among different lines, indicated that fat traits are the most important traits between lean and fat Pekin ducks (Ding et al., 2021). In this study, WHC may have a dominant effect of thigh muscle both in LCA and LCC.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, results showed that LCA had larger body weight, higher slaughter weight, as well as eviscerated yield than those of LCC ducks, indicating that LCA had high yield and fast growth. Further analysis on the meat quality showed that the content of fatty acid and amino acid related to flavor was higher in LCC compared with LCA. This study provides an objective evaluation of specialized breeding of meat ducks and new insights for the utilization of excellent germplasm resources and hybrid breeding in ducks.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32372825) and the Revitalization of the Seed Industry to Unveil the Marshal Project (core seed source research project) (JBGS (2021)112).

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ardö Y. Flavour formation by amino acid catabolism. Biotechnol. Adv. 2006;24:238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benet I., Guàrdia U., Ibañez M.D., Solà C., Arnau J., Roura J. Low intramuscular fat (but high in PUFA) content in cooked cured pork ham decreased Maillard reaction volatiles and pleasing aroma attributes. Food Chem. 2016;196:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z., Gao W., Zhang Y., Huo W., Weng K., Zhang Y., Li B., Chen G., Xu Q. Effect of marketable age on proximate composition and nutritional profile of breast meat from Cherry Valley broiler ducks. Poult. Sci. 2021;10011 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y., Zhang J., Jin Y., Deng J., Shi M., Miao Z. Effects of dietary supplementation of chinese yam polysaccharide on carcass composition, meat quality, and antioxidant capacity in broilers. Animals (Basel) 2023;13:503. doi: 10.3390/ani13030503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.D., Ma Q.G., Tang M.Y., Ji C. Development of breast muscle and meat quality in Arbor Acres broilers, Jingxing 100 crossbred chickens and Beijing fatty chickens. Meat Sci. 2007;772:220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe J., Choi H., M Y., Lee S., Shin H., G H., Ryu Y., Hong C., C K., Kim B.C. The relation between glycogen, lactate content and muscle fiber type composition, and their influence on postmortem glycolytic rate and pork quality. Meat Sci. 2008;80:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding S.R., Li G.S., Chen S.R., Zhu F., Hao J.P., Yang F.X., Hou Z.C. Comparison of carcass and meat quality traits between lean and fat Pekin ducks. Anim Biosci. 2021;347:1193–1201. doi: 10.5713/ajas.19.0612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo I.L., Claus T., Oliveira Santos Júnior O., Almeida V.C., Magon T., Visentainer J.V. Fast derivatization of fatty acids in different meat samples for gas chromatography analysis. J. Chromatogr. A. 2016;1456:235–241. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Cao S., Yang L., Li Z. Flavor formation based on lipid in meat and meat products: a review. J. Food Biochem. 2022;46:e14439. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.14439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao W., Cao Z., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Zhao W., Chen G., Li B., Xu Q. Comparison of carcass traits and nutritional profile in two different broiler-type duck lines. Anim Sci J. 2023;941:e13820. doi: 10.1111/asj.13820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghirri A., Bignetti E. Occurrence and role of umami molecules in foods. Int J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012;63:871–881. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2012.676028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumułka M., Połtowicz K. Comparison of carcass traits and meat quality of intensively reared geese from a Polish genetic resource flock to those of commercial hybrids. Poult. Sci. 2020;99:839–847. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2019.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraf G., Wołoszyn J., Okruszek A., Goluch Z., Wereńska M., Teleszko M. The protein and fat quality of thigh muscles from Polish goose varieties. Poult. Sci. 2021;1004 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo K.N., Hong E.C., Kim C.D., Kim H.K., Lee M.J., Choo H.J., Choi H.C., Mushtaq M.M., Parvin R., Kim J.H. Growth performance, carcass yield, and quality and chemical traits of meat from commercial korean native ducks with 2-way crossbreeding. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015;283:382–390. doi: 10.5713/ajas.13.0620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Guo Q., Wu Y., Jiang Y., Bai H., Wang Z., Chen G., Chang G. Carcass traits, proximate composition, amino acid and fatty acid profiles, and mineral contents of meat from Cherry Valley, Chinese crested, and crossbred ducks. Anim. Biotechnol. 2023;347:2459–2466. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2022.2096625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Cai H., Liu G., Yan H., Chang W., Zhang S. Effects of dynamic segmentation of nutrient supply on growth performance and intestinal development of broilers. Anim Nutr. 2016;24:276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo S.T., Kim G.D., Hwang Y.H., Ryu Y.C. Control of fresh meat quality through manipulation of muscle fiber characteristics. Meat Sci. 2013;954:828–836. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal R., Chandran P.C., Dey A., Sarma K., Padhi M.K., Giri S.C., Bhatt B.P. Status of Indigenous duck and duck production system of India - a review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2022;551:15. doi: 10.1007/s11250-022-03401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katan M., Zock B., Mensink P.L., P R. Effects of fats and fatty acids on blood lipids in humans: an overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60(6 Suppl):1017S–1022S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.6.1017S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G., Yang D., S H., Jeong J.Y. Comparison of characteristics of myosin heavy chain-based fiber and meat quality among four bovine skeletal muscles. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2016;36:819–828. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2016.36.6.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoszyński D., Wasilewski R., Stęczny K., Kotowicz M., Hrnčar C., Arpášová H. Carcass composition and selected meat quality traits of Pekin ducks from genetic resources flocks. Poult. Sci. 2019;987:3029–3039. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokoszyński D., Żochowska-Kujawska J., Kotowicz M., Skoneczny G., Kostenko S., Włodarczyk K., Stęczny K., Saleh M., Wegner M. The composition of the carcass, physicochemical properties, texture and microstructure of the meat of D11 Dworka and P9 Pekin ducks. Animals. 2022;12:1714. doi: 10.3390/ani12131714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H., Choo J., Choi Y.K., Kim Y.I., Kim E.J., Heo H.K., Choi K.N., Lee H.C., Kim S.K., Kim C.J., Kang B.G., An C.W., K B. Carcass characteristics and meat quality of Korean native ducks and commercial meat-type ducks raised under same feeding and rearing conditions. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci. 2014;27:1638–1643. doi: 10.5713/ajas.2014.14191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefaucheur L. A second look into fibre typing–relation to meat quality. Meat Sci. 2010;84:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.H., Joo S.T., Ryu Y.C. Skeletal muscle fiber type and myofibrillar proteins in relation to meat quality. Meat Sci. 2010;861:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo M., Zhang Z., Wang X., Shen W., Zhang L., Lin S. Molecular mechanisms underlying the impact of muscle fiber types on meat quality in livestock and poultry. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023;10 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2023.1284551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y., Huang J., Chen Y., Chen H., Zhao L., Huang M., Zhou G. Meat quality, fatty acid composition and sensory evaluation of Cherry Valley, Spent Layer and Crossbred ducks. Anim. Sci. J. 2017;88:156–165. doi: 10.1111/asj.12588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen T.D., Livak K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H., Zhang H., Liu D., Li S., Wang Z., Yu D., Guo Z.B., Hou S., Zhou Z. Changes in physical architecture and lipids compounds in skeletal muscle from Pekin duck and Liancheng white duck. Poult. Sci. 2023;102 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.103106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran D.H., Schonewille J.T., Pukkung C., Khempaka S. Growth performance and accretion of selected amino acids in response to three levels of dietary lysine fed to fast- and slow-growing broilers. Poult. Sci. 2021;1004 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venn-Watson S., Lumpkin R., Dennis E.A. Efficacy of dietary odd-chain saturated fatty acid pentadecanoic acid parallels broad associated health benefits in humans: could it be essential? Scientific Reports. 2020;10:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64960-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng K., Huo W., Gu T., Bao Q., Hou L.E., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Xu Q., Chen G. Effects of marketable ages on meat quality through fiber characteristics in the goose. Poult. Sci. 2021;1002:728–737. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.11.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng K., Huo W., Li Y., Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Chen G., Xu Q. Fiber characteristics and meat quality of different muscular tissues from slow- and fast-growing broilers. Poult. Sci. 2022;1011 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler T., Shackelford L., Johnson S.D., Miller L.P., Miller M.F., Koohmaraie R.K. A comparison of Warner-Bratzler shear force assessment within and among institutions. J. Anim. Sci. 1997;75:2423–2432. doi: 10.2527/1997.7592423x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.D., Hu Y., Hu S., Ma X., Hu J., Hu J., He B., Li H., Liu L., Wang H. Comparative analysis of amino acid content and protein synthesis-related genes expression levels in breast muscle among different duck breeds/strains. Poult. Sci. 2023;102 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.102277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Li L., Xin Q., Zhu Z., Miao Z., Zheng N. Metabolomic characterization of Liancheng white and Cherry Valley duck breast meat and their relation to meat quality. Poult. Sci. 2023;10211 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.103020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Deng Y., Ma J., Hu S., Hu J., Hu B., Liu H., Li L., He H., Wang J. Effects of different breeds/strains on fatty acid composition and lipid metabolism-related genes expression in breast muscle of ducks. Poult. Sci. 2022;1015 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.101813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., Yang Y., Wang L., Ye S., Liu J., Gong P., Qian Y., Zeng H., Chen X. Integrated multi-omic data reveal the potential molecular mechanisms of the nutrition and flavor in Liancheng white duck meat. Front Genet. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.939585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]