Abstract

The objective of this study was to investigate the protective effects and mechanisms of dietary administration of sodium humate (HNa) and its zinc and selenium chelate (Zn/Se-HNa) in mitigating Salmonella Typhimurium (S. Typhi) induced intestinal injury in broiler chickens. Following the gavage of 109 CFU S. Typhi to 240 broilers from 21-d to 23-d aged, various growth performance parameters such as body weight (BW), average daily gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI), and feed ratio (FCR) were measured before and after infection. Intestinal morphology was assessed to determine the villus height, crypt depth, and chorionic cryptologic ratio. To evaluate intestinal barrier integrity, levels of serum diamine oxidase (DAO), D-lactic acid, tight junction proteins, and the related genes were measured in each group of broilers. An analysis was conducted on inflammatory-related cytokines, oxidase activity, and Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-κB) and Nuclear factor erythroid2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway-related proteins and mRNA expression. The results revealed a significant decrease in BW, ADG, and FCR in S. typhi-infected broilers. HNa tended to increase FCR (P = 0.056) while the supplementation of Zn/Se-HNa significantly restored BW and ADG (P < 0.05). HNa and Zn/Se-HNa exhibit favorable and comparable effects in enhancing the levels of serum DAO, D-lactate, and mRNA and protein expression of jejunum and ileal tight junction. In comparison to HNa, Zn/Se-HNa demonstrates a greater reduction in S. Typhi shedding in feces, as well as superior efficacy in enhancing the intestinal morphology, increasing serum catalase (CAT) activity, inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines, and suppressing the activation of the NF-κB pathway. Collectively, Zn/Se-HNa was a more effective treatment than HNa to alleviate adverse impact of S. Typhi infection in broiler chickens.

Key words: sodium humate, zinc and selenium sodium humate chelate, intestinal health, broiler chicken, Salmonella Typhimurium

INTRODUCTION

Foodborne Salmonella infections caused by contaminated poultry products have caused certain economic losses and public health problems (Greening et al., 2022). Therefore, it is necessary to take Salmonella control measures at the farm level. Among them, Salmonella typhimurium (S. typhi) infection is one of the most common strains, which can lead to high mortality in young chickens. In broiler chickens, S. Typhi can cause intestinal or subclinical diseases, showing decreased growth performance, intestinal damage and inflammation, and intestinal barrier dysfunction. A study of 2007 to 2019 of 196 Salmonella strains collected showed that 84.7 % of the strains were resistant to at least one antimicrobial and 66.8 % of the isolates were multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains (Zhang et al., 2022). Besides, in poultry production, the over use of antibiotics may aggravate Salmonella resistant (Ansari-Lari et al., 2022) and environmental pollution (Jenkins et al., 2008). Therefore, it is necessary to explore environmentally friendly and more effective prevention and treatment programs to prevent chicken Salmonella infection and ensure the safety of poultry feed. Humic acid (HA), a type of organic matter produced by microbial decomposition and transformation of animal and plant remains, which can be extracted from coal, is abundant and cheap (Liu et al., 2008; Meng et al., 2022). As its sodium salt, sodium humate (HNa) has been applied and studied in animal husbandry due to its antimicrobial, antiviral, and antidiarrheal activities (Islam et al., 2005). As we have previously shown, HNa in mice infected with Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli K88 (ETEC K88) could alleviate intestinal dysfunction by reducing the inflammatory response, increasing the integrity of the intestinal barrier, and regulating intestinal microbiota and metabolism (Wang et al., 2022a). When administered to calves as part of their diet, HNa improved the immune status, antioxidant capacity, and beneficial intestinal microbiota, thereby promoting growth and reducing diarrheal diseases (Wang et al., 2022b). In poultry production, the addition of HA has been shown to have good buffering capacity in regulating intestinal pH (Arif et al., 2018), to alleviate some of the toxic effects of Aflatoxin B1 (Jansen et al., 2006), and to stabilize intestinal microbiota and improve nutrient utilization (Shermer et al., 1998), thus it is speculated that HA may be effective in improving the intestinal health of broilers.

Aryl rings and alicyclic rings are the basic structural elements of HA macromolecules, which also contain carboxyl groups, hydroxyl groups, carbonyl groups, quinone groups, and methoxy groups (de Melo et al., 2016). Due to the deprotonation of OH/OOH by phenolic and carboxylic groups in the HA molecule, it can form a complex with metal ions (Yates and Von Wandruszka, 1999). Studies have shown that HA can bind to silver (Litvin and Minaev, 2013), platinum (Aleksandrova et al., 2020), manganese oxide (Hou et al., 2020), etc., and enhance their antibacterial effects. Zinc (Zn) and selenium (Se) are important trace elements for poultry growth and development, involved in many biological processes and signaling molecules. In recent years, chelates containing Zn (Riduan and Zhang, 2021) and Se (Ramos-Inza et al., 2022) have attracted interest in the treatment of pathogenic entities due to their higher bactericidal activity. In previous studies, we synthesized Zn/Se-loaded HNa and proved that it has a better anti-S. Typhi effect than HNa (Fan et al., 2023). Therefore, HNa and its metal chelates may have good prospects in the prevention and treatment of S. Typhi infections in broilers.

The primary mechanism by which Zn exhibits toxicity towards bacteria involves the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the disruption of the cell membrane through charge transfer, resulting in the inhibition of bacterial proliferation (Abendrot and Kalinowska-Lis, 2018). The toxicity mechanism of Se nanoparticles and Se-containing compounds to bacteria is mainly mediated by ROS, but more research is needed to elucidate their antibacterial mechanism (Martinez-Esquivias et al., 2021). Studies have shown that the chelation of Se in Zn-containing compounds may exert further synergistic effects and enhance their antibacterial activity (Mahmoodi et al., 2018; Ahmad et al., 2020). In addition to improving antibacterial properties, chelating Zn and chelating Se with organic compounds may also be more effective than inorganic Zn and selenium in promoting growth performance and health of livestock and poultry in various ways. The addition of polysaccharide-complexed zinc to diets for gestating sows improved the apparent total tract digestibility and true total tract digestibility compared with zinc sulfate (Holen et al., 2020). Supplementation of zinc pectin oligosaccharides chelate in the diet increases Zn enrichment in the metabolic organs, serum alkaline phosphatase and copper-zinc superoxide dismutase activities increased, and promotes productive performance in broilers (Wang et al., 2019). In ovo injection of selenized glucose increased the superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and the mRNA expression of glutathione peroxidase 1(GPX1), thioredoxin reductase 1(TrxR1), and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1) of newborn chickens therefore upregulated its antioxidant capacity (Zhao et al., 2023). The dietary supplementation with Se nanoparticles synthesized with alginate oligosaccharides reduced heat stress-induced oxidative damage to broilers' spleens, bursa of Fabricius, and livers by increasing Nrf2-mediated antioxidant gene expression (Ye et al., 2023).

The purpose of this study was therefore to evaluate the effects of HNa and its Zn and Se chelate, Zn/Se-HNa, on growth performance, intestinal morphology, intestinal inflammatory and antioxidant capacity of broiler chickens infected with S. typhi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee of Northeast Agricultural University (Permit No. SRM-11).

Preparation of HNa and Zn/Se-HNa

Sodium humate (purity, 75%) was provided by the Institute of Coal Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanxi, China). It consists of 75% humic acid (dry basis), 20.52% burning residue (dry basis), 4.48% water soluble substances (dry basis) and 14.22% water (air dry basis). Zn/Se-HNa were prepared by an ion-exchange reaction as previous described (Fan et al., 2023).

Animals, Diets, and Experimental Design

Before the treatments, 240 1-day-old Arbor Acres chickens (41.71 ± 3.28 g) were screened as Salmonella-free, and randomly assigned to four treatments, each with 6 replicate cages (ten birds per cage). Four groups participated in this 27-d experiment: 1) control (CON) group (basal diet), (II) S. Typhi challenge (S.T.) group (basal diet + S. Typhi challenge), (III) S. Typhi challenge and HNa addition (S.T.+ HNa) group (basal diet extra 2.5 g/kg HNa + S. Typhi challenge), and (IV) S. Typhi challenge and Zn/Se-HNa addition (S.T.+ Zn/Se-HNa) group (basal diet extra 2.5 g/kg Zn/Se-HNa + S. Typhi challenge). The nutritional contents of the antibiotic-free experimental diets (Tables 1 and 2) were compiled according to NY/T 33-2004(Feeding standard of chicken). The basal diet of the I, II, and III group recived 75 mg/kg Zn in the form of ZnSO4 and 30 μg/Kg Se in the form of Na₂SeO₃. The IV group was given a Zn/Se-HNa-supplemented basal diet that calculated containing 75 mg/kg Zn and 30 μg/Kg Se.

Table 1.

Ingredients and nutrient composition of the basal diet (%).

| Item | Starter (1−21 d) | Grower (22−27 d) |

|---|---|---|

| Ingredients | ||

| Corn | 56.60 | 55.80 |

| Soybean meal (46% Crude protein) | 30.50 | 25.65 |

| Corn gluten meal | 2.50 | 3.00 |

| Wheat flour | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| Soybean oil | 2.00 | 7.25 |

| Dicalcium phosphate | 0.90 | 0.80 |

| Limestone | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| Premix1 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Calculated nutrient levels | ||

| Metabolizable energy(Kcal/kg) | 2956 | 3134 |

| Crude protein | 21.50 | 19.51 |

| Calcium | 0.96 | 0.84 |

| Total phosphorus | 0.66 | 0.55 |

| Lys | 1.45 | 1.40 |

| Met | 0.54 | 0.50 |

| Thr | 0.91 | 0.80 |

The Zn/Se-free trace mineral concentrate supplied per kilogram of diet: vitamin A, 11,500 IU; cholecalciferol, 3,500 IU; vitamin K3, 5 mg; vitamin E, 30 mg; thiamin, 3.39 mg; riboflavin, 9.0 mg; pyridoxine, 8.94 mg; vitamin B12, 0.025 mg; calcium pantothenate, 14 mg; choline chloride, 800 mg; niacin, 45 mg; biotin, 0.15 mg; folic acid, 1.20 mg; Mn, 75 mg; Fe, 60.5 mg; Cu, 8 mg; I, 0.70 mg.

Table 2.

The analyzed Zn/Se content of mineral premixes and diets.

| Analyzed Zn mg/kg |

Analyzed Se mg/kg |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Zn mg/kg (from ZnSO4) | Zn mg/kgfrom (Zn/Se-HNa) | Calculated Zn mg/kg | Starter | Grower | Se mg/kg (from Na2SeO3) | Se mg/kg (from Zn/Se-HNa) | Calculated Se mg/kg | Starter | Grower |

| CON | 75 | 0 | 75 | 76 | 76 | 0.30 | 0 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| S.T. | 75 | 0 | 75 | 76 | 76 | 0.30 | 0 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| S.T.+HNa | 75 | 0 | 75 | 78 | 78 | 0.30 | 0 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.30 |

| S.T.+Zn/Se-HNa | 0 | 75 | 75 | 79 | 79 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.31 |

The temperature was gradually lowered by 0.5°C per day 35 to 22°C, the relative humidity was maintained at 65% and the birds received ad libitum feed and water throughout the experimental period. We provided artificial light (10-20 lux) in a 23-h light/1-h dark cycle during the entire experiment.

Salmonella Typhimurium Challenge

The strain of S.Typhi used in this experiment was from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, No. 14028). The S. Typhi challenge was performed based on research by Marcq et al. (2011) with minor modifications (Marcq et al., 2011). Briefly, each chicken in the infected group was orally gavaged individually with 1 mL S. Typhi suspension (1 × 109 CFU/mL) by using a syringe with an attached flexible tube daily for 3 consecutive days from 21-day-old to 23-day-old. The CON group was given the same amount of sterile brain–heart infusion broth medium by gavage at the corresponding time points. Meanwhile, all procedures were conducted under the guide of the Qiqihar Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Qiqihar, China) to avoid the potential cross-contamination of groups.

Sample Collection and Intestinal Macroscopic Characteristic

At 27 d of age, peripheral blood samples were collected from the wing vein into tubes coated with coagulant and centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C to extract serum samples and then stored at -80°C until analysis. Following blood collection, birds were given an overdose of urethane intraperitoneally, and they were then euthanized after cervical dislocation. For histopathological analysis, about 1 cm sections of jejunum and ileum were cut and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution. In the next step, longitudinal dissection of about 2 cm section was carried out, the tissues were rinsed with cold saline to remove contents and the jejunum and ileum were frozen in liquid nitrogen. Once the samples were frozen, it was stored at -80°C until mRNA and protein analysis could be performed.

S. Typhi Enumeration in Fecal

Salmonella was enumerated in fecal samples of each group (n = 6) at 27 d of age. To collect fresh fecal samples, aluminum foil sheets were placed under each pen for 2 h. Feces obtained were transferred aseptically to 15 mL sterile conical tubes. The fecal samples were weighed 0.1 g each and collected into 1.5 mL sterile polypropylene microcentrifuge tubes, 900 μL of normal saline was added, and then homogenized. A serial dilution of all homogenates in saline was performed to obtain appropriate levels of growth on Salmonella-Shigella agar medium plates for isolation. Salmonella colonies were counted after 24 hours at 37°C incubation. The enumeration results in each sample were expressed as log10 CFU/g.

Hematoxylin–Eosin Staining and Intestinal Morphology

Multiple slices of 4.0 μm sections were made and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) solution after the fixed jejunum and ileum tissues were dehydrated, transparentized, and embedded in graded ethanol, xylol, and paraffin. Villi and crypts were selected for measurement of villus height (VH) and crypt depth (CD) under a light microscope in ten well-oriented samples.

Villus height was defined as the vertical distance from the tip of the villus to the villus-crypt junction, and crypt depth was defined as the vertical distance from the villus-crypt junction to the crypt base.

Measurement of Serum Diamine Oxidase and D-lactate

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits were adopted to detect the serum diamine oxidase (DAO) activity (JM-09299C1; Jingmei Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China) and serum D-lactate concentration (J81087; Jingmei Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China).

Measurement of Secretory Immunoglobulin A, Cytokines, and Antioxidant Capacity

Cryopreserved jejunal and ileal tissues were homogenized in 0.9% saline at a ratio of 1:9 (w/v), and then centrifuged at 5,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants of the homogenates were used to quantify levels of interleukin (IL)-1β(JM-00921C1), IL-8(JM-00855C1), IL-10(JM-00855C1), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)(JM-00869C), and secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA)(JM-100784C1). ELISA kits (Jingmei Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. A Bicinchoninic Acid Assay (BCA) protein concentration assay kit (P0009, Beyotime Biotechnology, Beijing, China) was used. Results are expressed as the concentration of cytokines or sIgA in the intestinal tissue of broilers per microgram of protein. The same commercial ELISA kits were used to determine the concentrations of IL-1β, IL-10, and TNF-α in serum.

The supernatants were then diluted into the appropriate content for examining the activities of total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD; A001-1-1), total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC; A015-1-2), CAT (A007-1-1), and the concentration of malondialdehyde (MDA; A003-1-2) using the assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China). The results were expressed as activities of antioxidant enzymes and concentration of MDA per mg of protein in the intestinal tissues of broilers. Additionally, the serum activities of T-SOD, T-AOC, CAT, and concentration of MDA were also detected using the same assay kits

Total RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Isolation of total RNA from jejunal and ileal tissues was done with Trizol reagent (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China). Microspectrophotometric (NanoDrop-1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) measurements were performed to determine the concentration and purity of the extracted RNA. Then PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (RR047A, TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China) was used to produce the complementary DNA. The cDNA obtained was subjected to real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR using ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix Kit (Vazyme Biotechnology, Nanjing, China) based on Applied Biosystems 7,500 Real-time PCR System (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). The relative mRNA abundance of the target genes was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method and normalized with the expression level of the endogenous reference gene (β-actin). The qRT-PCR primers for target genes were commercially synthesized by Sangon Biotechnology (Shanghai, China) and listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Gene-specific primers sequences for quantitative real-time PCR.

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′to3′) | GenBank Accession Number |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | F: ACCGGACTGTTACCAACACC R: CCTGAGTCAAGCGCCAAAAG |

NM_205518.1 |

| IL-1β | F: TGCCTGCAGAAGAAGCCTCG R: CTCCGCAGCAGTTTGGTCAT |

NM_204524.1 |

| IL-8 | F: AGATGTGAAGCTGACGCCAAG R: CCAAGCACACCTCTCTTCCAT |

DQ393272.2 |

| IL-10 | F: CTGTCACCGCTTCTTCACCT R: GAACTCCCCCATGGCTTTGT |

NM_012854.2 |

| TNF-α | F: GAACCCTCCGCAGTACTCAG R: AACTCATCTGAACTGGGCGG |

HQ739087.1 |

| ZO-1 | F: AGCCCCTTGGTAATGTGTGG R: TTGGGCGTGACGTATAGCTG |

XM_015278981.2 |

| OCLN | F: ATGCACCCACTGAGTGTTGG GAGGTGTGGGCCTTACACAG |

NM_205128.1 |

| CLDN1 | F: CTTCAGCACCTTCCTTTCC R: CGCTACATCTTCTGTTGGC |

NM_001013611.2 |

| NF-κB | F: AAGATCTGGTGGTGTGCCTG R: AGTGGAACCTTTCGCGGATT |

NM_001012887.2 |

| IκBα | F: CAGCACTACACTTGGCCGTA R: GGAGTAGCCCTGGTAGGTCA |

NM_001001472.2 |

| CAT | F: GGTTCGGTGGGGTTGTCTTT R: CACCAGTGGTCAAGGCATCT |

NM 001031215.1 |

| SOD1 | F: GGCAATGTGACTGCAAAGGG R: CCCCTCTACCCAGGTCATCA |

NM_205064.1 |

| Keap1 | F: CATCGGCATCGCCAACTT R: TGAAGAACTCCTCCTGCTTGGA |

XM_025145847.1 |

| NQO1 | F: CGCACCCTGAGAAAACCTCT R: AAGCACTCGGGGTTCTTGAG |

NM_001277619.1 |

| HO-1 | F: AGCTTCGCACAAGGAGTGTT R: GGAGAGGTGGTCAGCATGTC |

NM_205344.1 |

| Nrf2 | F: GGGCAAGGCGTGAAGTTTTT R: GGCTTTCTCCCGCTCTTTCT |

NM_205117.1 |

| iNOS | F: ACTGAAGGTGGCTATTGGGC R: TAGCAGTTGTTGGGTGGGTG |

D85422.1 |

β-actin, Beta actin; IL, Interleukin; TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor; ZO-1, Zonula occludens-1; OCLN, Occludin; CLDN-1, Claudin-1; NF-κB, Nuclear factor kappa beta; IκBα, NF-kappa-B inhibitor alpha; CAT,catalase; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; KEAP1, kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; NQO1, NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; iNOS, Inducible nitric oxide synthase.

Western Blot Analysis for Protein Expressions

In Radio Immunoprecipitation Assay (RIPA) lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor, cryopreserved tissue samples were homogenized. A BCA protein concentration assay kit was used to determine total protein concentration. Denatured protein was separated on an 8%-12% SDS-PAGE gel and electroransferred onto nitrocellulose (NC) membrane in equal amounts. After blocking with blocking buffer (5% skimmed milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 1% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature, the NC membranes were incubated with primary antibodies as follows: OCLN (DF7504; Affinity Biosciences, Jiangsu, China), ZO-1 (DF2250; Affinity), CLDN-1 (AF0127; Affinity), NF-κB (10745-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc., Wuhan, China), IκBα (10268-1-AP; Proteintech), NQO1(11451-1-AP; Proteintech), Nrf2 (16396-1-AP; Proteintech), HO-1 (10701-1-AP; Proteintech) and β-actin (20536-1-AP; Proteintech) overnight at 4℃, and then, after proper washing, incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000, Biosharp, BL003A) for 1 h at room temperature. Then, with ECL reagents (E412- 01; Vazyme Biotechnology) and Imager-Bio-Rad (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, United States), the expression of target proteins was detected. Finally, the integrated density (ID) of the protein bands was analyzed using Image J software. Data are presented as target protein (ID)/β-actin (ID).

Statistical Analysis

All the data derived were checked for normal distribution before conducting statistical analysis and then analyzed as one-way ANOVA (SPSS 20.0, Inc., IBM, Chicago, IL) followed by Tukey's test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. The results were presented as means with their standard errors (SEM).

RESULTS

Growth Performance

There were no significant differences pre-challenge in birth weight, BW of day 21, and ADG, ADFI, or FCR from day 1 to day 21 among all groups (P > 0.05). Mortality occurred in the S.T. group and S.T.+HNa group after the S. Typhi Challenge. Compared with the CON group, S. Typhi infection reduced final BW, 22-27 day ADG, and 22-27 day FCR (Table 4, P < 0.05). HNa did not remarkably ameliorate the negative impact of S. Typhi, but the FCR at 22-27 day tended to be decreased (P = 0.056). Dietary Zn/Se-HNa attenuated the adverse effects of S. Typhi infection and increased the final BW and ADG compared with the S.T. group (P < 0.05). No mortality was observed in the S.T.+Zn/Se-HNa group during the experimental period.

Table 4.

Effects of HNa and Zn/Se-HNa on growth preformance of broilers before and after inoculation with Salmonella typhimurium.

| Treatmentitem | I CON | II S.T. | III S.T.+HNa | IV S.T.+Zn/Se-HNa | SEM | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (BW, g/broiler/pen) | ||||||

| D 1 | 41.71 | 41.35 | 40.77 | 40.39 | 1.53 | 0.468 |

| D 21 | 849.08 | 850.71 | 848.87 | 869.09 | 3.25 | 0.065 |

| D 27 | 1450.77a | 1278.63b | 1369.35ab | 1445.33a | 22.99 | 0.024 |

| Average daily body weight gain (ADG, g/broiler/pen) | ||||||

| D 1–21 | 40.37 | 40.46 | 40.40 | 41.44 | 0.16 | 0.067 |

| D 22–27 | 100.28a | 71.32b | 86.75ab | 96.04a | 3.90 | 0.029 |

| Daily feed intake (ADFI, g/broiler/pen) | ||||||

| D 1–21 | 49.80 | 50.70 | 50.90 | 50.18 | 3.67 | 0.873 |

| D 22–27 | 132.06 | 105.98 | 118.63 | 131.43 | 4.06 | 0.375 |

| Feed conversion ratio (FCR, g feed/g BW) | ||||||

| D 1–21 | 1.23 | 1.25 | 1.26 | 1.21 | 0.01 | 0.563 |

| D 22–27 | 1.31b | 1.50a | 1.37ab | 1.36ab | 0.03 | 0.044 |

| Number of dead broilers in the trial | ||||||

| 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

(I) CON, control group (basal diet); (II)S.T., S. Typhi challenge group (basal diet + S. ‘Typhi challenge); (III) S.T.+ HNa, S. Typhi challenge and HNa addition group, and (IV) S.T.+ Zn/Se-HNa, S. Typhi challenge and Zn/Se-HNa addition group.

S. Typhi Enumeration in Fecal

Fecal shedding of Salmonella spp was enumerated to investigate the bacteriostatic activity of HNa and Zn/Se-HNa in challenged broiler chickens (Figure 1D). In the CON group, no Salmonella colony was found. Salmonella can only have detected in the feces of the infected and treated groups. Compared with the S.T. group, dietary administration of HNa and Zn/Se-HNa reduced fecal Salmonella quantity (P < 0.05). Compared with HNa, the supply of Zn/Se-HNa reduced Salmonella to a greater extent (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effects of dietary HNa or Zn/Se-HNa supplementation on the jejunal macroscopic changes and the morphology of S. Typhi challenged broilers. (A) Images of jejunal tissues; (B) Histological section of jejunum and ileum;(C) VH, CD, and VH/CD of the intestine;(D) Salmonella spp enumeration in fecal. a-c Means with different letters differ significantly among the groups (P < 0.05). VH, villus height; CD, crypt depth.

Intestinal Tissue Morphology

There was no visible injury found at the macroscopic level of the jejunum in the CON group, whereas the S. Typhi challenge caused mucosal injury, including thinning of the intestinal wall and spots of hemorrhage. Infection-induced macroscopic lesions were alleviated when HNa and Zn/Se-HNa were administered (Figure 1A). A comparison of S.T. group broilers with the control group shows impaired villi development of jejunum and ileum, as broken and shortened villi are depicted in Figure 1B. By the histological observations, S. Typhi infection decreased the jejunum VH and VH/CD compared with the CON group and increased the ileum CD significantly (Figure 1C, P < 0.05). Compared with the S.T. group, HNa improved jejunum VH and VH/CD (P < 0.05), and Zn/Se-HNa increased VH of jejunum and VH/CD of both jejunum and ileum (P < 0.05) and decreased CD of ileum.

Intestinal Barrier Integrity

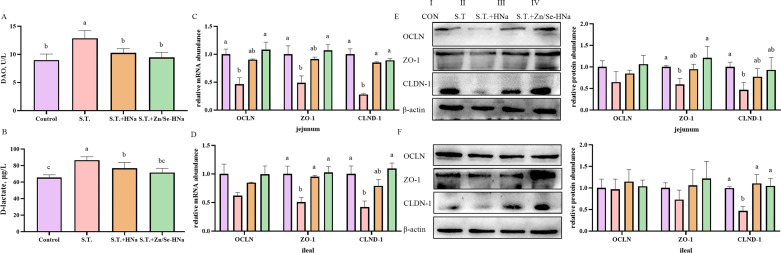

To analyze intestinal barrier integrity, the results of the evaluation of serum DAO activity, D-lactate concentration, mRNA levels of OCLN, ZO-1, CLDN-1, and related protein expression levels of jejunum and ileum in broiler chickens consuming a diet supplemented HNa or Zn/Se-HNa are summarized in Figure 2. Increases in serum DAO activity and D-lactate concentration were observed in chickens in the S.T. group compared with the CON group. Chickens that received HNa and Zn/Se-HNa showed a reduction in serum DAO activity and D-lactate concentration when compared with the S.T. group (P < 0.05). In contrast to the CON group, challenged broilers had lower levels of mRNA for jejunal and ileal CLDN-1 and ZO-1 and jejunal ZO-1 and OCLN (P < 0.05), but had no notable differences in ileal OCLN expression (P > 0.05). In the S.T.+HNa group, jejunal CLDN-1 and ileal ZO-1adverse alterations were ameliorated (P < 0.05). Zn/Se-HNa supplementation reversed reductions of jejunal and ileal CLDN-1 and ZO-1 and jejunal ZO-1 and OCLN (P < 0.05). Western blot analysis revealed that HNa addition increased ileal CLDN-1(P < 0.05). Zn/Se-HNa administration increased the abundance of jejunal ZO-1 and ileal CLDN-1 (P < 0.05). The results indicated that intestinal barrier integrity was maintained when HNa and Zn/Se-HNa were added.

Figure 2.

Effects of dietary HNa and Zn/Se-HNa supplementation on the intestinal barrier function. (A) Serum DAO activity; (B) serum D-lactate concentration; (C and D) the mRNA abundance of jejunal and ileal OCLN, ZO-1, and CLDN-1; (E and F) the relative protein abundance of jejunal and ileal OCLN, ZO-1, and CLDN-1. Values were expressed as mean with standard error represented by vertical bars. a−c Means with different letters differ significantly among the groups (P < 0.05). OCLN, occludin; ZO-1, zonula occludens-1; CLDN-1, claudin-1.

Concentrations of Inflammatory Cytokines and Intestinal sIgA

To investigate whether supplementing with HNa and Zn/Se-HNa could mitigate inflammation caused by S. Typhi infection, we measured the concentration and mRNA abundance of inflammatory cytokines in the serum, jejunum, and ileum and sIgA concentration in the jejunum and ileum (Figure 3). After S. Typhi infection, the serum and jejunum concentrations of IL1-β and TNF-α were increased, although no significant difference in IL-10 concentration was observed. The S.T. group showed higher serum IL-8 concentrations compared to the CON group (P < 0.05). As for mRNA abundance analysis, IL1-β, IL-8, and TNF-α were increased (P < 0.05). The administration of HNa resulted in suppression of the serum IL-8 and tissue IL1-β mRNA levels (P < 0.05). Zn/Se-HNa supplementation suppressed serum IL-8 and TNF-α and jejunum IL1-β and TNF-α both in cytokine and mRNA and also rescued IL-10 mRNA level (P < 0.05). In addition, jejunal sIgA concentrations were down-regulated after S. Typhi infection which could be increased by Zn/Se-HNa supplementation (P < 0.05). In combination, HNa and Zn/Se-HNa administration may alleviate inflammation through modulating the production of inflammatory-related cytokines.

Figure 3.

Effects of dietary HNa and Zn/Se-HNa supplementation on the inflammation-related and sIgA cytokines. (A–D) serum IL-1β, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α;(E) the Levels of jejunal and ileal sIgA; (F–I) the levels of jejunal and ileal IL-1β, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α; (J-M) the relative mRNA abundance of jejunal and ileal IL-1β, IL-8, IL-10, TNF-α. Values were expressed as mean with standard error represented by vertical bars. a-c Means with different letters differ significantly among the groups (P < 0.05).IL-1β, interleukin-1β; IL-8, interleukin-8; IL-10, interleukin-10; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

NF-κB Signaling Pathway

To determine whether the anti-inflammatory mechanism of HNa and Zn/Se-HNa on S. Typhi-induced intestinal inflammation act through the NF-κB pathway, the jejunum and ileum were examined for the presence of NF-κB and IκBα using western blot and qRT-PCR techniques. As exhibited in Figure 4, S. Typhi increased the mRNA levels of NF-κB in jejunal and ileal tissues and decreased IκBα in jejunal tissues (P < 0.05). Moreover, western blot analysis revealed that protein levels of jejunal and ileal NF-κB were higher in the S.T. group compared to the CON group (P < 0.05), while no significant difference was observed in IκBα levels in the intestine (P > 0.05). Zn/Se-HNa administration effectively inhibited the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway (P < 0.05), whereas HNa had no significant effect (P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of dietary HNa and Zn/Se-HNa supplementation on the NF-κB signaling pathway. (A and B) Jejunal and ileal relative mRNA abundance of NF-κB and IκBα; (C) jejunal NF-κB and IκBα relative protein abundance; (D) ileal NF-κB and IκBα relative protein abundance. Values were expressed as mean with standard error represented by vertical bars. a,b Means with different letters differ significantly among the groups (P < 0.05). NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa beta; IκBα, NF-kappa-B inhibitor alpha.

Antioxidant Enzymes Activities

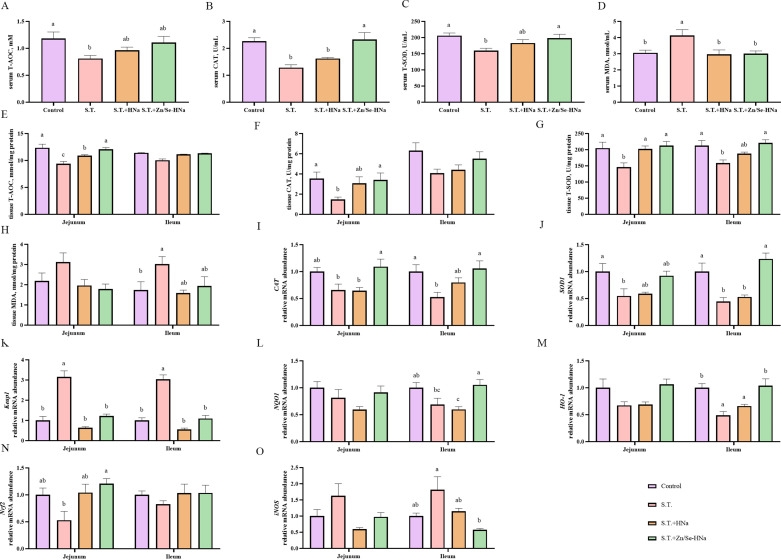

As revealed by Figure 5, the serum activities of T-AOC, CAT, and T-SOD were decreased (P < 0.05) after S. Typhi infection, but Zn/Se-HNa interventions elevated that (P < 0.05) while HNa exerted no significant effect (P > 0.05). In the S.T. group, serum MDA level was raised but decreased by HNa and Zn/Se-HNa (P < 0.05). T-AOC, CAT, and T-SOD levels were decreased in jejunal tissue of the S.T. group and ameliorated by HNa and Zn/Se-HNa (P < 0.05). In ileal tissues, T-SOD decreased and MDA increased significantly in the S.T. group while T-SOD levels were reversed in HNa and Zn/Se-HNa groups.

Figure 5.

Effects of dietary HNa and Zn/Se-HNa supplementation on the activities of antioxidant enzymes and abundance of Nrf2 pathway related mRNA. (A–D) serum T-AOC, CAT, T-SOD, MDA levels; (E–H) jejunal and ilealT-AOC, CAT, T-SOD, MDA levels; (J–O) the relative mRNA abundance of jejunal and ileal SOD1, Keap1, NQO,1 HO-1, Nrf2 and iNOS.Values were expressed as mean with standard error represented by vertical bars. a, b Means with different letters differ significantly among the groups (P < 0.05). T-AOC, totalantioxidant capacity; CAT catalase; T-SOD, total superoxide dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; KEAP1, kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; NQO1, NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1; HO1, heme oxygenase 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-relatedfactor 2.

Nrf2 Signaling Pathway

The findings of gene expression related to the Nrf2 signaling pathway in the jejunum and ileum are displayed in Figure 5 I-5O. In S.T. group, CAT and SOD1 levels decreased in jejunum and ileum, HO-1 decreased in ileum and Keap1 increased in jejunum compared with the CON group (P < 0.05). HNa decreased the Keap1 mRNA level in jejunum and the iNOS mRNA level in ileum. Zn/Se-HNa increased CAT in jejunum and ileum, increased SOD1, NQO1, HO-1, and Nrf2 levels in ileum, and decreased Keap1 levels in jejunum and ileum and iNOS in ileum.

Figure 6 presents the protein abundance of NQO1, HO-1, and Nrf2 of jejunal and ileal tissues. In the S.T. group, NQO1, HO-1, and Nrf2 of jejunal tissue were suppressed compared with CON group (P < 0.05). When compared with S.T. group, HNa showed no significant alleviation of suppression while Zn/Se-HNa increased NQO1, HO-1, and Nrf2 of jejunal tissue.

Figure 6.

Effects of dietary HNa and Zn/Se-HNa supplementation on the Nrf2 signaling pathway. (A and B) The relative protein abundance of NQO1, Nrf2, and HO1 in jejunum; (C and D) The relative protein abundance of NQO1, Nrf2, and HO1 in ileum. Values are means with their standard errors represented byvertical bars. a, b Means within a row with different letters differ significantly (P < 0.05). NQO1, NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1; HO1, heme oxygenase 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-relatedfactor 2.

DISCUSSION

Using dietary HNa and its Zn and Se chelate (Zn/Se-HNa), the present study investigated the effectiveness of these supplements for the control of S. Typhi infection and protection of intestinal health in broiler chickens, and the broiler-infected model was built by S. Typh suspension oral gavage at a 3-week-old (Marcq et al., 2011). Our findings are similar to those of previous studies (Aljumaah et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020; Fazelnia et al., 2021), which found that S. Typhi gavage negatively affected broiler final BW, ADG, and FCR among growth performance parameters. Under non-challenged rearing environments, the appropriate dose of humic substances administration caused a measurable variation in broiler performance (Ozturk et al., 2012). However, the addition of HNa in the current study had no remarkable growth-improving influences while mildly attenuated FCR. Zn/Se-HNa positively affected growth performance by increasing final BW and ADG. It is speculated that this may be due to the higher bioavailability of chelated Zn and organic Se than inorganic Zn and Se in chickens, leading to better growth performance (Michalczuk et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2023). A recent study showed a positive association between Zn and appetite, which may also contribute to the role of Zn/Se-HNa (Redhai et al., 2020). Nonetheless, further investigation is still required on Zn/Se-HNA effect on growth performance and Zn and Se bioavailability under the influence of other adverse factors, as well as normal feeding conditions.

In the present study, although broilers died in the S.T. group, consistent with previous studies, there were no obvious symptoms of salmonellosis in the flocks, which may be similar to the phenomenon of poultry carrying Salmonella within industrial (Prevost et al., 2006). Salmonella carriage refers to the ability of the bacteria to persist in the host organism without causing any symptoms. Infected animals shed large amounts of bacteria in their feces, thereby infecting other animals and contaminating meat products (Menanteau et al., 2018). Therefore, it is necessary to reduce the shedding of Salmonella in feces. By enumerating S. Typhi in feces, HNa and Zn/Se-HNa could significantly reduce the number of bacteria compared with S.T. group. In a previous in vitro experiment, we verified that Zn/Se-HNa had a stronger antibacterial effect than HNa (Fan et al., 2023). Park et al. showed in a series of aerobic and anaerobic in vitro studies that organic Zn may have a stronger inhibitory effect on Salmonella than inorganic Zn, thereby reducing Salmonella colonization and invasion in the chicken gut (Park et al., 2002; Park et al., 2004). Similarly, Zn/Se-HNa addition resulted in less shedding of bacteria than HNa addition in this experiment.

To evaluate intestinal barrier function, and integrity, we determined the intestinal morphology, tight junction (TJ) related mRNA and protein of jejunum and ileum and serum DAO and D-lactate levels. In the present study, S. Typhi caused intestinal pathological damage, as the manifestations were by observed macroscopic lesion, shortened VH, and decreased VH/CD ratio, corresponding to decreased nutrient digestion and absorption. An intestinal mucosal barrier comprised of tight junction proteins is the first line of defense against harmful bacteria. The present study found that S. Typhi infection impaired intestinal barrier integrity, as indicated by the increased serum DAO and D-lactate levels, as well as the partially down-regulated OCLN, ZO-1, and ClND-1 mRNA and corresponding protein levels in the small intestine. These observations are partially consistent with previous evidence suggesting that S. Typhi infection leads to intestinal morphology impairment, intestinal barrier integrity damage and intestinal permeability increase in broilers (Leyva-Diaz et al., 2021; Yadav et al., 2022). Previous research indicated that HNa can alleviate intestinal damage caused by pathogenic microorganisms (Wang et al., 2022b). Here, we found that HNa supplementation significantly reduced the jejunal hemorrhagic spot, restituted VH and VH/CD in the jejunum, decreased serum levels of DAO and D-lactate, and up-regulated some TJ-related mRNA and protein expression as compared with S.T. group broilers. Importantly, Zn/Se-HNa is more effective than HNa in increasing ileal VH and VH/CD and decreasing ileal CD. Several studies have shown that Zn is involved in the repair of damaged intestinal epithelial cells and prevention of increased intestinal permeability caused by pathogen invasion in broiler chickens (Zhang et al., 2012; Shao et al., 2014). The possible mechanism is that Zn directly regulates DNA and protein synthesis, inhibits apoptosis, and regulates cell proliferation (Truong-Tran et al., 2001). A study showed that an equal amount of organic Se supplementation was more effective in increasing TJ protein expression than inorganic Se (Chen et al., 2021). Therefore, the protective mechanism of Zn/Se-HNA on intestinal barrier can be explained by the interaction of Zn, Se, and HNa.

There is often a simultaneous interaction between oxidative stress and inflammation as they are part of normal defense mechanisms against pathogens (Lauridsen, 2019). To elucidate why dietary HNa and Zn/Se-HNa could alleviate intestinal barrier damage, broilers infected with S. Typhi were further evaluated for changes in inflammatory cytokines, intestinal mucosal immunity, and antioxidant enzymes activities. After infection, the levels of serum IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α, as well as intestinal IL-1β, and TNF-α found to be increased, while the levels of sIgA and IL-10 mRNA in the jejunum were observed to be decreased in the current investigation. HNa showed a weaker inhibitory effect on pro-inflammatory cytokines and a lower promoting effect on sIgA and anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-10, than Zn/Se-HNa. This may be a result of the fact that the protective effect of Zn in the inflammatory response is partly due to its inhibitory effect on the excessive secretion of proinflammatory factors (Prasad, 2008). It is suggested that HA contributes to antioxidant defense for its phenolic groups acting as electron donors, scavenging free metals, inhibiting the formation of free radicals by transition metal catalysis, and controlling lipid peroxidation and DNA fragmentation (Khil'Ko et al., 2011). Analyzing the scavenging of 2,2’-azinobis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate (ABTS), the activity of 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radicals, the activity of superoxide radicals, iron chelating activity, and scavenging of hydroxyl radicals, the antioxidant and cytoprotective activity of HAs in 3T3-L1 cell was verified (Zykova et al., 2022). It is believed that humic substances reduced the adverse effects of tritium for it could mitigate the radiotoxic effect and enhance microorganisms' adaptive responses through a reduction in ROS content (Rozhko et al., 2020). Based on our previous study in calves, HNa supplementation enhanced serum antioxidant enzymes levels and decreased the serum inflammatory cytokine concentrations, indicating that the positive effect of HNa may act through inflammatory mediators and anti-oxidative stress defense (Wang et al., 2022b). Similarly in the current study, HNa and Zn/Se-HNa provision reduced intestinal damage by increasing serum and intestinal T-AOC, CAT, and T-SOD activities and the decrease of MDA. As a result of these findings, HNa and Zn/Se-HNa may alleviate intestinal damage through the increased activity of antioxidant enzymes.

NF-κB is a major transcription factor in inflammatory diseases and a transcription factor of the Rel-homology-domain family where IκBα binds (Dunham-Snary et al., 2012). IκBα, as an inhibitor of NF-κB, forms an inactive NF-κB/IκBα complex in the cytoplasm. Upon stimulation, IκBα is degraded, thus abolishing its inhibition act, following nuclear translocation of active NF-κB and leading to the expression of proinflammatory genes (Hall et al., 2006). The current results demonstrated that during S. Typhi infection, HNa suppressed jejunal NF-κB mRNA expression. Zn/Se-HNa resulted in a remarkable reduction of jejunal IκBα mRNA and an increase of jejunal and ileal NF-κB mRNA and protein. Some studies suggest that HA and humate may improve inflammation by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway. HAs alleviate dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis through inhibiting activation of the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-NF-κB pathway (Huang et al., 2023). In S. Typhi infected Mice, supplementation with HNa alleviated intestinal barrier damage via modulating gut microbiota, downregulating TLR4/NF-κB and NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) signaling pathways (Wang et al., 2023). The nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a key modifier in both antioxidant inflammation (Yan et al., 2018). It maintaining cellular redox balance, and the inactive form of Nrf2 usually co-exists with Keap1 in the cytoplasm. When oxidative stress occurs in the body, ROS increases, the complex oxidative stress response system in the body is activated, Nrf2 releases from Keap1 and then enters the nucleus, and a series of antioxidant enzymes are induced to alleviate the damage to the body (Zhang et al., 2004). In the mice cerebral ischemia model, HA showed potential as a therapeutic agent through preventing oxidative stress by increasing SOD and nuclear respiratory factor-1 (NRF-1) levels and decreasing MDA concentration (Ozkan et al., 2015). According to an interesting study, a high concentration of fulvic acid (a type of humic acid) induced Nrf2, Keap-1, CAT, and SOD-1 gene expression, enhanced the production of ROS inside the zebrafish larvae and caused tissue damage and death while at low to medium concentrations may improve larval health (Lieke et al., 2021). Jejunal and ileal mRNA and protein expression of Nrf2 and downstream target molecules were activated by HNa and Zn/Se-HNa. Studies indicated that the protective effects of Zn involve antioxidant mechanisms; whether it is through Zn alone (as an antioxidant), Zn induction of metallothionein, or Zn inhibition of redox-sensitive transcription factors (Jarosz et al., 2017). In addition, there was a direct and significant relationship between serum Se levels and the expression of some other Nrf2-related genes, including GSTP1 and SOD2 (Reszka et al., 2015). However, most of the related indexes showed that there was no significant difference in antioxidant activity between the HNa and Zn/Se-HNa supplication groups.

In conclusion, as a result of S. Typhi infection, tight junction proteins and genes were downregulated, leading to injury, inflammation, and a disrupted antioxidant defense system in the intestine in broiler chickens. This study indicated that dietary supplementation of HNa and its Zn and Se chelate may have potential as a treatment for S. Typhi infection in broilers. Furthermore, Zn/Se-HNa demonstrated a more effective containment effect in S. Typhi shedding, barrier damage, and intestinal inflammation compared to HNa, while no remarkable promotion in antioxidant profile. Zn/Se-HNa showed favorable results compared with HNa in current study. In addition, further investigation under nonchallenge condition should be conducted to explore whether Zn/Se-HNa is more suitable as a feed additive for broiler chickens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported by the China Agriculture Research System (CARS36) of the MOF and MARA.

DISCLOSURES

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abendrot M., Kalinowska-Lis U. Zinc-containing compounds for personal care applications. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2018;40(4):319–327. doi: 10.1111/ics.12463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad A., Ullah S., Ahmad W., Yuan Q., Taj R., Khan A.U., Rahman A.U., Khan U.A. Zinc oxide‑selenium heterojunction composite: Synthesis, characterization and photo-induced antibacterial activity under visible light irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2020;203 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aleksandrova G., Lesnichaya M., Dolmaa G., Sukhov B., Regdel D. The effect of organic matter humification (aromaticity and oxidation degree) on structural and nanomorphological characteristics of humic nanocomposites of metallic platinum. Environ. Res. 2020;190 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aljumaah M.R., Alkhulaifi M.M., Abudabos A.M., Alabdullatifb A., El-Mubarak A.H., Al S.A., Stanley D. Organic acid blend supplementation increases butyrate and acetate production in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium challenged broilers. Plos One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari-Lari M., Hosseinzadeh S., Manzari M., Khaledian S. Survey of Salmonella in commercial broiler farms in Shiraz, southern Iran. Prev. Vet. Med. 2022;198 doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2021.105550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arif M., Rehman A., El-Hack M.E.A., Saeed M., Al-Owaimer A. Growth, carcass traits, cecal microbial counts, and blood chemistry of meat-type quail fed diets supplemented with humic acid and black cumin seeds. Asian Australasian J. Anim. Ences. 2018;31:1930–1938. doi: 10.5713/ajas.18.0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S., Xue Y., Shen Y., Ju H., Zhang X., Liu J., Wang Y. Effects of different selenium sources on duodenum and jejunum tight junction network and growth performance of broilers in a model of fluorine-induced chronic oxidative stress. Poult. Sci. 2021;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Melo B.A., Motta F.L., Santana M.H. Humic acids: Structural properties and multiple functionalities for novel technological developments. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2016;62:967–974. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham-Snary K.J., Westbrook D.G., Sammy M.J., Ratcliffe W., Ballinger S.W. Conceptual background and bioenergetic/mitochondrial aspects of oncometabolism. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2012;53:S94. [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Li J., Ren X., Wang D., Liu Y. Preparation, characterization, bacteriostatic efficacy, and mechanism of zinc/selenium-loaded sodium humate. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023;107:7417–7425. doi: 10.1007/s00253-023-12803-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazelnia K., Fakhraei J., Yarahmadi H.M., Amini K. Dietary supplementation of potential probiotics Bacillus Subtilis, Bacillus Licheniformis, and Saccharomyces Cerevisiae and synbiotic improves growth performance and immune responses by modulation in intestinal system in broiler chicks challenged with Salmonella Typhimurium. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins. 2021;13:1081–1092. doi: 10.1007/s12602-020-09737-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greening B.J., Whitham H.K., Aldous W.K., Hall N., Garvey A., Mandernach S., Kahn E.B., Nonnenmacher P., Snow J., Meltzer M.I., Hoffmann S. Public health response to multistate salmonella typhimurium outbreak associated with prepackaged chicken salad, United States, 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022;28:1254–1256. doi: 10.3201/eid2806.211633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall G., Hasday J.D., Rogers T.B. Regulating the regulator: NF-kappaB signaling in heart. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:580–591. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holen J.P., Johnston L.J., Urriola P.E., Garrett J.E., Shurson G.C. Comparative digestibility of polysaccharide-complexed zinc and zinc sulfate in diets for gestating and lactating sows. J. Anim. Sci. 2020;98 doi: 10.1093/jas/skaa079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou M., Liu W., Zhang L., Zhang L., Xu Z., Cao Y., Kang Y., Xue P. Responsive agarose hydrogel incorporated with natural humic acid and MnO(2) nanoparticles for effective relief of tumor hypoxia and enhanced photo-induced tumor therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2020;8:353–369. doi: 10.1039/c9bm01472a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Huang Y., Wang C., Zhang W., Qu Y., Li D., Wu W., Gao F., Zhu L., Wu B., Zhang L., Cui X., Li T., Geng Y., Liao X., Luo X. The organic zinc with moderate chelation strength enhances the expression of related transporters in the jejunum and ileum of broilers. Poult Sci. 2023;102 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.102477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Xu P., Shao M., Wei B., Zhang C., Zhang J. Humic acids alleviate dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis by positively modulating gut microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1147110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam K.M.S., Schumacher A., Gropp J.M. Humic acid substances in animal agriculture. Pakistan J. Nutr. 2005;4:126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen V.R.C., Van Rensburg C.E., Van Ryssen J.B., Casey N.H., Rottinghaus G.E. In vitro and in vivo assessment of humic acid as an aflatoxin binder in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2006;85:1576–1583. doi: 10.1093/ps/85.9.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosz M., Olbert M., Wyszogrodzka G., Mlyniec K., Librowski T. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of zinc. Zinc-dependent NF-kappaB signaling. Inflammopharmacology. 2017;25:11–24. doi: 10.1007/s10787-017-0309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins M.B., Truman C.C., Siragusa G., Line E., Bailey J.S., Frye J., Endale D.M., Franklin D.H., Schomberg H.H., Fisher D.S., Sharpe R.R. Rainfall and tillage effects on transport of fecal bacteria and sex hormones 17beta-estradiol and testosterone from broiler litter applications to a Georgia Piedmont Ultisol. Sci. Total Environ. 2008;403:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khil'Ko S.L., Efimova I.V., Smirnova O.V. Antioxidant properties of humic acids from brown coal. Solid Fuel Chem+ 2011;45:367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Lauridsen C. From oxidative stress to inflammation: redox balance and immune system. Poult. Sci. 2019;98:4240–4246. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyva-Diaz A.A., Hernandez-Patlan D., Solis-Cruz B., Adhikari B., Kwon Y.M., Latorre J.D., Hernandez-Velasco X., Fuente-Martinez B., Hargis B.M., Lopez-Arellano R., Tellez-Isaias G. Evaluation of curcumin and copper acetate against Salmonella Typhimurium infection, intestinal permeability, and cecal microbiota composition in broiler chickens. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021;12:23. doi: 10.1186/s40104-021-00545-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieke T., Steinberg C., Bittmann S., Behrens S., Hoseinifar S.H., Meinelt T., Knopf K., Kloas W. Fulvic acid accelerates hatching and stimulates antioxidative protection and the innate immune response in zebrafish larvae. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;796 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvin V.A., Minaev B.F. Spectroscopy study of silver nanoparticles fabrication using synthetic humic substances and their antimicrobial activity. Spectrochim Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013;108:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2013.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.F., Zhao Z.S., Jiang G.B. Coating Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles with humic acid for high efficient removal of heavy metals in water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:6949–6954. doi: 10.1021/es800924c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi N.M., Karimi B., Mazarji M., Moghtaderi H. Cadmium selenide quantum dot-zinc oxide composite: Synthesis, characterization, dye removal ability with UV irradiation, and antibacterial activity as a safe and high-performance photocatalyst. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2018;188:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcq C., Cox E., Szalo I.M., Thewis A., Beckers Y. Salmonella Typhimurium oral challenge model in mature broilers: bacteriological, immunological, and growth performance aspects. Poult Sci. 2011;90:59–67. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-01017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Esquivias F., Guzman-Flores J.M., Perez-Larios A., Gonzalez S.N., Becerra-Ruiz J.S. A review of the antimicrobial activity of selenium nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2021;21:5383–5398. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2021.19471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menanteau P., Kempf F., Trotereau J., Virlogeux-Payant I., Gitton E., Dalifard J., Gabriel I., Rychlik I., Velge P. Role of systemic infection, cross contaminations and super-shedders in Salmonella carrier state in chicken. Environ. Microbiol. 2018;20:3246–3260. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F., Huang Q., Cai Y., Yuan G., Xiao L., Han F.X. Effect of humic acid derived from leonardite on the redistribution of uranium fractions in soil. Peerj. 2022;10:e14162. doi: 10.7717/peerj.14162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalczuk M., Batorska M., Sikorska U., Bien D., Urban J., Capecka K., Konieczka P. Selenium and the health status, production results, and product quality in poultry. Anim Sci J. 2021;92:e13662. doi: 10.1111/asj.13662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan A., Sen H.M., Sehitoglu I., Alacam H., Guven M., Aras A.B., Akman T., Silan C., Cosar M., Karaman H.I. Neuroprotective effect of humic Acid on focal cerebral ischemia injury: an experimental study in rats. Inflammation. 2015;38:32–39. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-0005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk E., Ocak N., Turan A., Erener G., Altop A., Cankaya S. Performance, carcass, gastrointestinal tract and meat quality traits, and selected blood parameters of broilers fed diets supplemented with humic substances. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012;92:59–65. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.Y., Woodward C.L., Birkhold S.G., Kubena L.F., Nisbet D.J., Ricke S.C. In vitro comparison of anaerobic and aerobic growth response of salmonella typhimurium to zinc addition. J. Food Safety. 2002;22:219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Park S.Y., Woodward C.L., Birkhold S.G., Kubena L.F., Nisbet D.J., Ricke S.C. The combination of zinc compounds and acidic pH limits aerobic growth of a Salmonella typhimurium poultry marker strain in rich and minimal media. J. Environ. Sci. Health B. 2004;39:199–207. doi: 10.1081/pfc-120027449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad A.S. Zinc in human health: effect of zinc on immune cells. Mol. Med. 2008;14:353–357. doi: 10.2119/2008-00033.Prasad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevost K., Magal P., Beaumont C. A model of Salmonella infection within industrial house hens. J. Theor. Biol. 2006;242:755–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Inza S., Plano D., Sanmartin C. Metal-based compounds containing selenium: An appealing approach towards novel therapeutic drugs with anticancer and antimicrobial effects. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022;244 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redhai S., Pilgrim C., Gaspar P., Giesen L.V., Lopes T., Riabinina O., Grenier T., Milona A., Chanana B., Swadling J.B., Wang Y.F., Dahalan F., Yuan M., Wilsch-Brauninger M., Lin W.H., Dennison N., Capriotti P., Lawniczak M., Baines R.A., Warnecke T., Windbichler N., Leulier F., Bellono N.W., Miguel-Aliaga I. An intestinal zinc sensor regulates food intake and developmental growth. Nature. 2020;580:263–268. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2111-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reszka E., Wieczorek E., Jablonska E., Janasik B., Fendler W., Wasowicz W. Association between plasma selenium level and NRF2 target genes expression in humans. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2015;30:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riduan S.N., Zhang Y. Recent advances of zinc-based antimicrobial materials. Chem. Asian J. 2021;16:2588–2595. doi: 10.1002/asia.202100656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozhko T.V., Kolesnik O.V., Badun G.A., Stom D.I., Kudryasheva N.S. Humic substances mitigate the impact of tritium on luminous marine bacteria. involvement of reactive oxygen species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21 doi: 10.3390/ijms21186783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y., Lei Z., Yuan J., Yang Y., Guo Y., Zhang B. Effect of zinc on growth performance, gut morphometry, and cecal microbial community in broilers challenged with Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. J. Microbiol. 2014;52:1002–1011. doi: 10.1007/s12275-014-4347-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shermer C.L., Maciorowski K.G., Bailey C.A., Byers F.M., Ricke S.C. Caecal metabolites and microbial populations in chickens consuming diets containing a mined humate compound. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998;77:479–486. [Google Scholar]

- Truong-Tran A.Q., Carter J., Ruffin R.E., Zalewski P.D. The role of zinc in caspase activation and apoptotic cell death. Biometals. 2001;14:315–330. doi: 10.1023/a:1012993017026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., He Y., Liu K., Deng S., Fan Y., Liu Y. Sodium humate alleviates enterotoxigenic escherichia coli-induced intestinal dysfunction via alteration of intestinal microbiota and metabolites in mice. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.809086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Zheng Y., Fan Y., He Y., Liu K., Deng S., Liu Y. Sodium humate-derived gut microbiota ameliorates intestinal dysfunction induced by Salmonella Typhimurium in mice. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023;11 doi: 10.1128/spectrum.05348-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., You Z., Du Y., Zheng D., Jia H., Liu Y. Influence of sodium humate on the growth performance, diarrhea incidence, blood parameters, and fecal microflora of pre-weaned dairy calves. Animals (Basel) 2022;12 doi: 10.3390/ani12010123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.C., Yu H.M., Xie J.J., Cui H., Nie H., Zhang T., Gao X.H. Effect of dietary zinc pectin oligosaccharides chelate on growth performance, enzyme activities, Zn accumulation, metallothionein concentration, and gene expression of Zn transporters in broiler chickens1. J. Anim. Sci. 2019;97:2114–2124. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.T., Yang W.Y., Samuel W.Y., Chen J.W., Chen Y.C. Modulations of growth performance, gut microbiota, and inflammatory cytokines by trehalose on Salmonella Typhimurium-challenged broilers. Poult. Sci. 2020;99:4034–4043. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav S., Teng P.Y., Choi J., Singh A.K., Vaddu S., Thippareddi H., Kim W.K. Influence of rapeseed, canola meal and glucosinolate metabolite (AITC) as potential antimicrobials: effects on growth performance, and gut health in Salmonella Typhimurium challenged broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Li J., Zhang L., Sun Y., Jiang J., Huang Y., Xu H., Jiang H., Hu R. Nrf2 protects against acute lung injury and inflammation by modulating TLR4 and Akt signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018;121:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.04.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates L.M., Von Wandruszka R. Decontamination of polluted water by treatment with a crude humic acid blend. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1999;33:2076–2080. [Google Scholar]

- Ye X.Q., Zhu Y.R., Yang Y.Y., Qiu S.J., Liu W.C. Biogenic selenium nanoparticles synthesized with alginate oligosaccharides alleviate heat stress-induced oxidative damage to organs in broilers through activating Nrf2-mediated anti-oxidation and anti-ferroptosis pathways. Antioxidants (Basel) 2023;12 doi: 10.3390/antiox12111973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Shao Y., Liu D., Yin P., Guo Y., Yuan J. Zinc prevents Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium-induced loss of intestinal mucosal barrier function in broiler chickens. Avian Pathol. 2012;41:361–367. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2012.692155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D.D., Lo S.C., Cross J.V., Templeton D.J., Hannink M. Keap1 is a redox-regulated substrate adaptor protein for a Cul3-dependent ubiquitin ligase complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;24:10941–10953. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.24.10941-10953.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Ge H., He J., Hu M., Xu Z., Jiao X., Chen X. Salmonella typhimurium ST34 isolate was more resistant than the ST19 isolate in China, 2007 - 2019. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2022;19:62–69. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2021.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M., Li J., Shi Q., Shan H., Liu L., Geng T., Yu L., Gong D. The effects of in ovo feeding of selenized glucose on selenium concentration and antioxidant capacity of breast muscle in neonatal broilers. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2023;201:5764–5773. doi: 10.1007/s12011-023-03611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zykova M.V., Brazovskii K.S., Bratishko K.A., Buyko E.E., Logvinova L.A., Romanenko S.V., Konstantinov A.I., Krivoshchekov S.V., Perminova I.V., Belousov M.V. Quantitative structure-activity relationship, ontology-based model of the antioxidant and cell protective activity of peat humic acids. Polymers (Basel) 2022;14 doi: 10.3390/polym14163293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]