Abstract

Background

Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression is recognized as a key biomarker in the treatment of non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with anti-PD(L)1 inhibitors. Previous work has highlighted that outcomes in patients with NSCLC treated with anti-PD(L)1 inhibitors generally improve with increasing PD-L1 expression. The objectives of these analyses are to quantitate the effect of PD-L1 expression on outcomes, to characterize the potentially nonlinear relationship between PD-L1 expression and outcomes, and to assess potential differences in these relationships across subgroups.

Patients and Methods

We performed a retrospective, pooled analysis of 11 clinical trials submitted to the US FDA between 2015 and 2022 that included patients with advanced NSCLC treated with anti-programmed death 1 or anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) monotherapy in the first-line (1L) or second-line (2L) treatment setting. The clinical outcomes explored were overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and objective response rate (ORR).

Results

The primary analysis population included 3806 patients with advanced NSCLC, of which 2040 were treated in 1L and 1766 in 2L. For patients with a PD-L1 score of 100% in the 1L setting, the hazard ratio versus a patient with 1% PD-L1 was 0.55 (95% CI, 0.43 to 0.70) for OS and 0.50 (95% CI, 0.41 to 0.61) for PFS. For patients with a PD-L1 score of 100% in the 2L setting, the hazard ratio versus a patient with 0% PD-L1 was 0.55 (95% CI, 0.43 to 0.71) for OS and 0.51 (95% CI, 0.41 to 0.63) for PFS. Subgroup analyses suggested that this relationship may vary by subgroup, particularly by region.

Conclusions

These analyses suggest PD-L1 expression has an appreciable impact on clinical outcomes for patients with NSCLC treated with ICI. As the impact of PD-L1 expression on outcomes may vary across regions, it is critical that future trials are multiregional and enroll a diverse patient population.

Keywords: immune checkpoint inhibitor, non–small cell lung cancer, NSCLC, PD-1, PD-L1

Previous studies have shown that outcomes in patients with non–small cell lung cancer treated with anti-PD(L)1 inhibitors generally improve with increasing programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression. This article focuses on the effect of PD-L1 expression on outcomes, to characterize the potentially nonlinear relationship between PD-L1 expression and outcomes, and to assess potential differences in these relationships across subgroups.

Implications for Practice.

The results of this analysis may help inform discussions between oncologists and patients when considering treatment options, as well as help to inform the design of future clinical trials.

Introduction

Although lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related death in the world,1 the advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has led to significant progress in the treatment of patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer (advanced NSCLC). Agents targeting programmed death 1 (PD-1) or programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) were initially approved as monotherapy in the second-line (2L) setting for advanced NSCLC on the basis of improved overall survival (OS) compared to docetaxel.2–9, More recently, PD-(L)1 inhibitors, administered alone, in combination with platinum-doublet chemotherapy, in combination with anti-CTLA4 inhibitors, or in combination with platinum-doublet chemotherapy and anti-CTLA4 inhibitors, have been incorporated into standard first-line (1L) treatment regimens for advanced NSCLC without targetable alterations in the epidermal growth factor receptor or anaplastic lymphoma kinase genes.2–4,10–20 In the 1L setting, monotherapy regimens are approved for use in patients with a specified PD-L1 expression.

Multiple anti-PD-(L)1 agents, including pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, and cemiplimab, have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for advanced NSCLC with PD-L1 expression on ≥50% of tumor cells3,16,21 and PD-L1 expression has been described as a continuous biomarker with posited correlation to immunotherapy efficacy in patients with NSCLC.22 The 50% cut-point for PD-L1 expression was first described for the Dako 22C3 assay in patients with advanced NSCLC treated with pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-001.23 A recent multicenter, academic, retrospective analysis of 187 patients with NSCLC and high PD-L1 expression ≥50% demonstrated that clinical outcomes to first-line pembrolizumab were improved with increasing expression of PD-L1.24 In particular, NSCLCs with a PD-L1 level of ≥90% had significant increases in overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and OS compared to NSCLCs with a PD-L1 level of 50%-89%.

Prior analyses of the relationship between PD-L1 expression and outcomes in NSCLC have generally been limited to reported PD-L1 expression groupings (eg, >1%, ≥50%) with limited ability to investigate these relationships by subgroup.25,26 We seek to expand upon previous findings by examining pooled FDA clinical trial databases in pooled analyses to evaluate the impact of increasing PD-L1 expression on efficacy outcomes for patients with advanced NSCLC. The objectives of these analyses are to quantitate the effect of PD-L1 expression on outcomes on a granular level, to characterize the potentially nonlinear relationship between PD-L1 expression and outcomes, and to assess potential differences in the strength of this relationship across subgroups.

Methods

Selection Criteria

We identified 11 clinical trials submitted to the US FDA between 2015 and 2020 as initial or supplemental Biologics License Applications that included patients with advanced NSCLC treated with anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 ICI monotherapy in the 1L or 2L treatment setting. All trials analyzed were randomized, active-controlled trials. Outcome measures evaluated included OS, defined as the time from randomization to death, PFS, defined as the time from randomization to disease progression or death from any cause, and ORR using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1.27 Additional data were also collected on subgroups including tumor histology (squamous vs nonsquamous), age, sex, race, smoking status, presence of brain or CNS metastases (whichever was reported in the data set), region, and number of prior lines of therapy.

PD-L1 expression was assessed in these trials with the use of 3 validated immunohistochemical assays depending on the ICI, including the pharmDx 22C3, 28-8 (Agilent Technologies, Inc.), and Ventana SP142 (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.) assays. For the purposes of this study, PD-L1 expression was defined as the percentage of tumor cells with positive membranous staining as detected by the primary assay (if multiple assays were used). Tumor-infiltrating immune cell staining was not considered.

Statistical Analysis

All efficacy analyses were conducted using the as-treated population of the ICI arms of the selected trials. Two separate analyses were conducted for the 1L and 2L settings. Distributions for time-to-event endpoints were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods. Summary statistics are provided for the following subgroups of PD-L1 expression: 0%-19%, 20%-39%, 40%-59%, 60%-79%, and 80%-100% PD-L1 expression. The usual cutoffs for PD-L1 expression in NSCLC are 1% and 50%. These categories were chosen to allow for a more granular inspection of the relationship between outcomes and PD-L1 expression. Summary statistics with more granular PD-L1 expression groupings are available in Supplementary Material.

In comparative analyses, the effect of PD-L1 score was analyzed on a continuous scale. For 1L trials, the reference category was a PD-L1 expression of 1%, and for the 2L trials, the reference category was a PD-L1 expression of 0%. The effect of PD-L1 score was assumed fixed across trials and was modeled with a restricted cubic spline (3 knots). The effect of PD-L1 on OS and PFS was assessed using a Cox model stratified by trial and adjusted by prognostic factors within each stratum. The prognostic factors were chosen based on common factors used to stratify randomization within each line (1L: ECOG status, sex, and histology; 2L: ECOG status, region, and number of prior lines of therapy). The effect of PD-L1 on ORR was assessed using a logistic regression model with trial as a fixed effect and adjusted by the same covariates as included in the models for PFS and OS. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran’s Q28 and I2 statistic.29,30

Subgroup analyses were conducted to assess whether the effect of PD-L1 expression on outcome varied by subgroup. For simplicity and interpretability, subgroup analyses were conducted assuming the effect of PD-L1 score within each model was linear. Forest plots depict unadjusted hazard ratios of the effect of a 10% increase in PD-L1 expression on outcome. Comparisons of the effect of PD-L1 expression on outcome between subgroups were estimated assuming the interaction effect of PD-L1 expression and subgroup was fixed across trials. These models were adjusted for PD-L1 expression and prognostic factors by trial. Due to limited data, races other than “White” and “Asian” were pooled into a single group (“Other”). Since this was an exploratory, retrospective cohort study, no a priori statistical analysis plan was prespecified.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted in the 1L population to assess the impact of assay on the results as well as the effect of PD-L1 expression in patients with PD-L1 expression ≥50% (“PD-L1 high”). Recursive partitioning analyses were conducted in order to assess whether additional cutpoints beyond 1% and 50% may further meaningfully subdivide the population.

Statistical analyses were performed using R 4.0.2.31 The survival32 and splines packages were used for the primary analyses and the ggplot233 and survminer34 packages were used for plotting. The rpart package35 was used to implement recursive partitioning.

Results

Study Population

ICI monotherapy arms from 11 randomized clinical trials (six 1L and five 2L) were selected for this pooled analysis using the PD-1 inhibitors pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and cemiplimab, and the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab (Supplementary Table S1). The process for selecting patients for inclusion is outlined in Supplementary Fig. S1. Patients who were not treated or whose PD-L1 expression was not reported were excluded. For analyses that adjusted for covariates, patients with any missing covariate information were removed. The primary analysis population included 3806 patients with advanced NSCLC, of which 2040 were treated in 1L and 1766 in 2L.

The 1L primary analysis population characteristics were median age of 64 years; 72% male; 76% White and 19% Asian; 68% ECOG performance score (ECOG PS) of ≥1 (Supplementary Table S2). The 2L primary analysis population characteristics were median age of 63 years; 62% male; 78% White and 17% Asian; 67% ECOG PS of ≥1 (Supplementary Table S3). Baseline clinicopathologic characteristics were generally well-balanced among the PD-L1 subcategories. The distributions of PD-L1 scores in the 1L and 2L settings are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2.

First-Line NSCLC

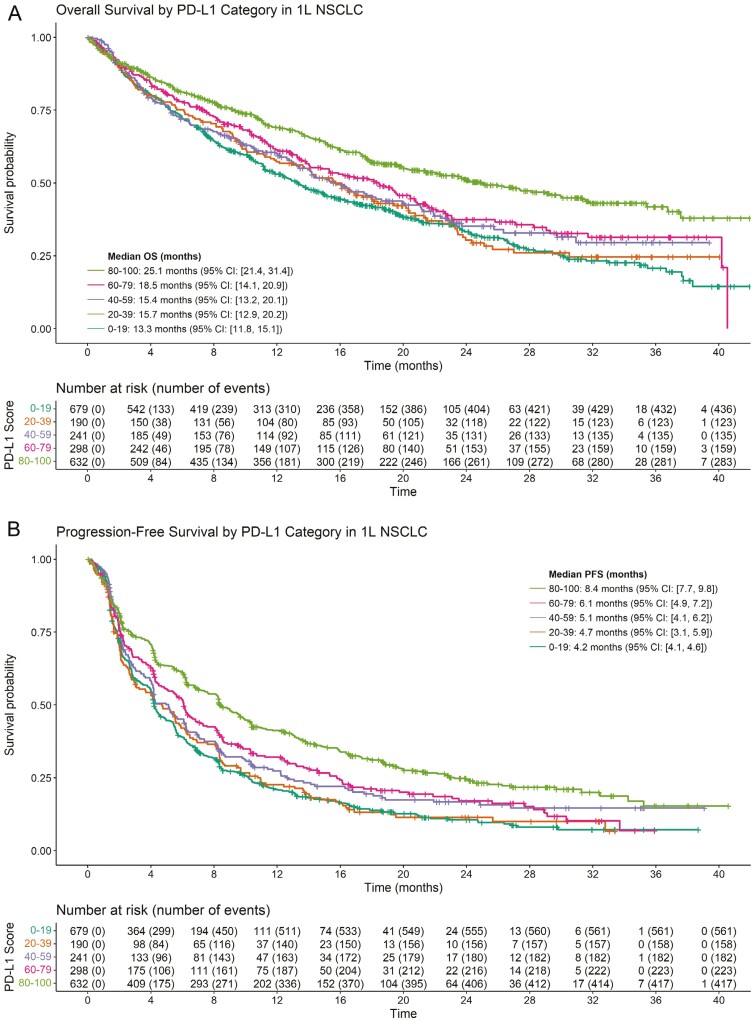

OS and PFS curves by PD-L1 expression category for patients with 1L NSCLC treated with ICI therapy are shown in Figure 1. Of 2040 1L patients treated with ICI whose PD-L1 status was known at baseline, there were 1138 OS events and 1541 PFS events. OS generally increased with increasing PD-L1 expression, with a median OS of 13.3, 15.7, 15.4, 18.5, and 25.1 months in the 0-19, 20-39, 40-59, 60-79, and 80-100 groups, respectively. Similarly, PFS generally increased with increasing PD-L1 expression, with a median PFS of 4.2, 4.2, 6.0, 6.3, and 9.1 months in the same PD-L1 categories. Supplementary Figs. S3, S4, S7 illustrate OS, PFS, and ORR by more granular PD-L1 expression groupings. Figure 2 shows the adjusted hazard ratio of PFS and OS of patients with increasing PD-L1 scores versus patients with a PD-L1 score of 1%. These plots suggest that OS and PFS generally increase as PD-L1 expression increases.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS and PFS in 1L NSCLC for patients treated with ICI monotherapy stratified by PD-L1 score (20-point increments). Results for OS are shown in (A) and results for PFS are shown in (B). (A) Overall Survival. (B) Progression-free survival.

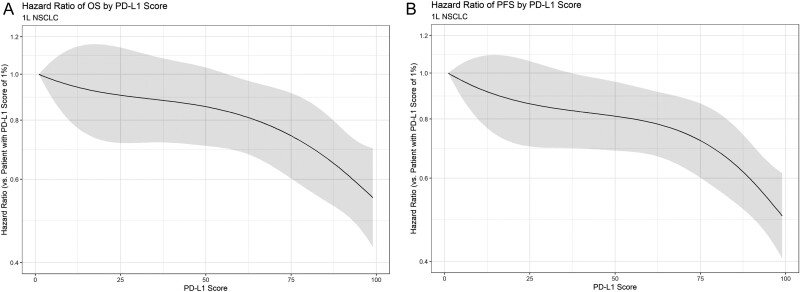

Figure 2.

Smoothed hazard ratio and 95% CIs for OS and PFS of patients with 1L NSCLC with varying PD-L1 scores. Hazard ratios are calculated as compared to a patient with a PD-L1 score of 0%. (A) Effect of PD-L1 score on OS in 1L NSCLC. (B) Effect of PD-L1 score on PFS in 1L NSCLC.

Based on the models, the hazard ratio of OS for patients with 50% PD-L1 versus patients with 1% PD-L1 was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.69 to 0.96); the corresponding hazard ratio for PFS was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.69 to 0.96). For patients with a PD-L1 score of 100, the hazard ratio versus a patient with 1% PD-L1 was 0.55 (95% CI, 0.43 to 0.70) for OS and 0.50 (95% CI, 0.41 to 0.61) for PFS. Similar trends were found for the effect of PD-L1 on ORR (Supplementary Fig. S8). Statistical tests did not suggest a significant departure from linearity for the effect of PD-L1 in these models. In addition, no significant heterogeneity was noted for either the OS model (Q = 6.9198; I2 = 1%; P = .9969) or the PFS model (Q = 14.8982; I2 = 1%; P = .7822).

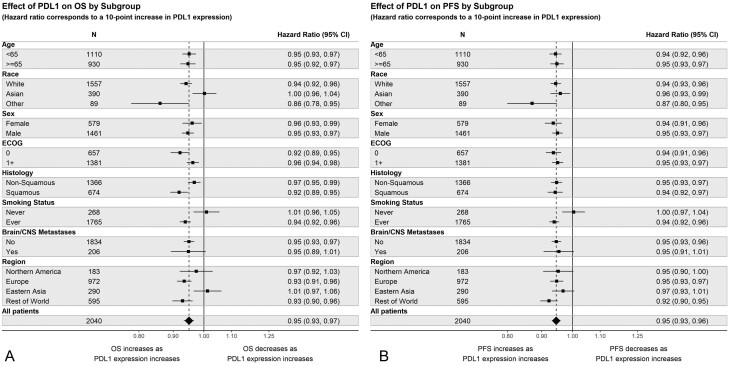

Figure 3 shows the effect of a 10% increase in PD-L1 on OS and PFS by subgroup. Covariate-adjusted comparisons of the interaction effect are presented in Supplementary Table S4. Results for ORR are presented in Supplementary Figs. S8, S9 and Supplementary Table S6. The subgroup analyses suggest that the effect of increasing PD-L1 expression on OS and PFS may differ for smokers versus nonsmokers. For instance, the estimated hazard ratio of OS for a 10-point increase in PD-L1 expression is 1.01 (95% CI, 0.96 to 1.05) for never-smokers and 0.94 (95% CI, 0.92 to 0.96) for smokers. The graphs suggest potential differences for other subgroups, although the effects are not replicated across endpoints. Notably, the effect of increasing PD-L1 on OS may differ by region.

Figure 3.

Effect of PD-L1 on outcomes by subgroup in 1L NSCLC. Hazard ratios correspond to a 10-point increase in PD-L1 expression. The effect of PD-L1 on outcomes is assumed linear within the Cox model. (A) Effect of PD-L1 on OS by subgroup. (B) Effect of PD-L1 on PFS in 1L NSCLC.

Sensitivity Analyses for the 1L NSCLC Population

Assay

The above results assume that the various assays used for the primary analyses in the respective trials have similar diagnostic performance. Previous studies that have assessed the concordance among these assays have found that there is a strong concordance between the 22C3 and 28-8 assays, while the concordance of these assays with the SP142 is poor to fair.36

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact of assay on the primary results. The above analyses were repeated using PD-L1 results from only the 22C3 and 28-8 assays. Note that all 1L studies used one of these assays for the primary analyses except for IMpower110. However, IMpower110 also collected information on the 22C3 and SP263 to inform assay comparisons.37 For this sensitivity analysis, the 22C3 results from Impower110 were used. The distribution of PD-L1 values using these assays is shown in Supplementary Fig. S10. Results from the sensitivity analyses are shown in Supplementary Figs. S11, S12. There were 2035 1L patients with known PD-L1 expression per either the 22C3 or 28-8 assays. In general, the results are similar to the primary analysis of the 1L population.

PD-L1 High Population

The emergence of combination treatment of ICI and chemotherapy has suggested that ICI monotherapy may be used in practice most frequently for patients with high PD-L1 expression. One cutoff often associated with “high expression” is usually ≥50% PD-L1 expression (Supplementary Table S1). Given this, there is particular interest in the role of PD-L1 expression for patients with ≥50% PD-L1 expression. For this reason, we also conducted sensitivity analyses on the population of patients with ≥50% PD-L1 expression. Because this cutoff is sensitive to the assay used, these analyses used PD-L1 expression as captured by the 22C3 or 28-8 assays.

Results are presented in Supplementary Fig S13. There were 1172 patients with ≥50% expression per the 22C3 or 28-8 assays. As with the primary analysis, all outcomes tend to improve with increasing PD-L1 expression. The adjusted hazard ratio of OS for patients with 100% PD-L1 versus patients with 50% PD-L1 is 0.70 (95% CI, 0.51 to 0.96). For PFS, the hazard ratio is 0.64 (95% CI, 0.49 to 0.83). A key question in this subpopulation is whether there exists a cutoff that further improves discrimination in outcomes. To this end, we conducted recursive partitioning analyses in this subset of patients. The following initial splits were identified in the ≥50% dataset (22C3 and 28-8 assays only): none for OS, <87.5 versus ≥87.5 for PFS, and < 87.5 versus ≥87.5 for ORR. These cutoffs were held when other prognostic covariates were included. Of note, ECOG was the initial split when other covariates were included for OS. Note that only values of 85 and 90 were reported in the dataset. Functionally, the identified cutpoint of 87.5 would result in PDL1 groupings of ≤85 and ≥90. This is consistent with the findings of other similar studies.24

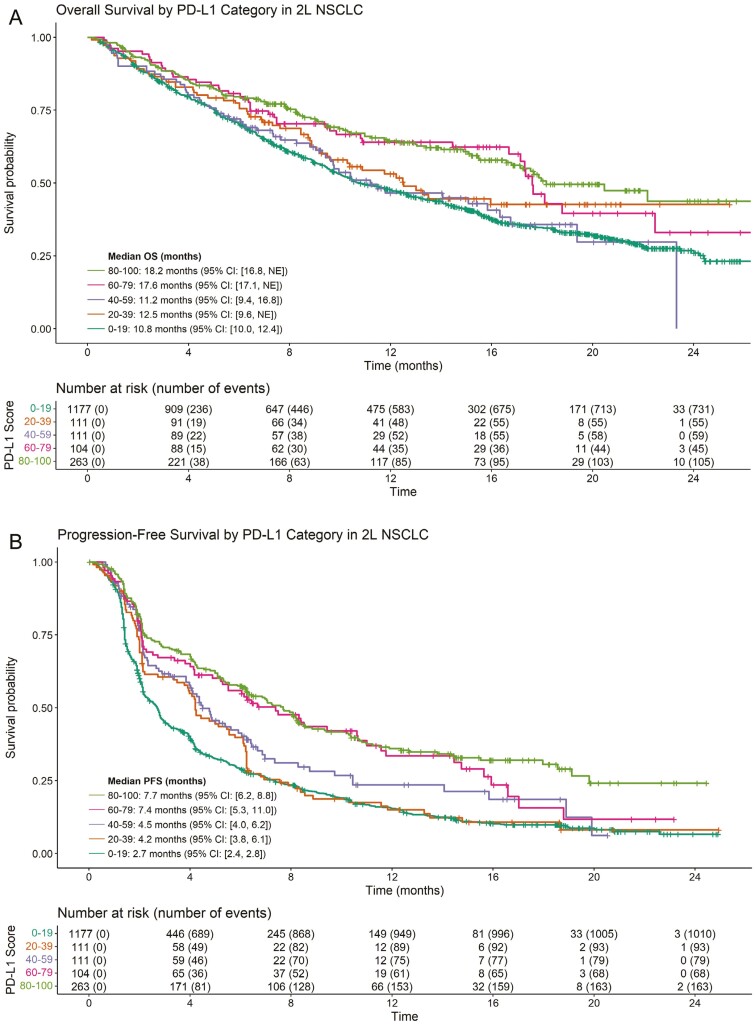

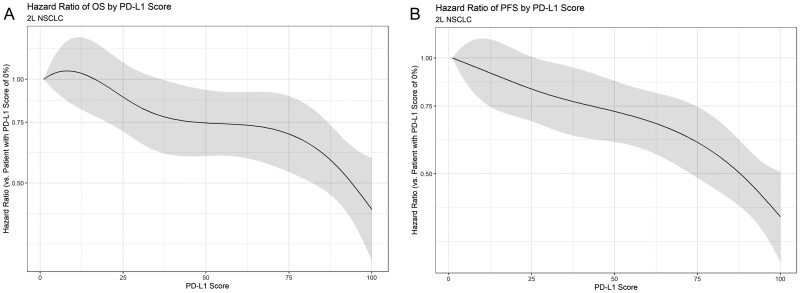

Second-Line NSCLC

OS and PFS curves by PD-L1 expression category for patients with 2L NSCLC treated with ICI therapy are shown in Figure 4. Of 1766 2L patients treated with ICI whose PD-L1 status was known at baseline, there were 999 OS events and 1413 PFS events. OS generally increased with increasing PD-L1 expression, with a median OS of 10.8, 12.5, 11.2, 17.6, and 18.2 months in the 0-19, 20-39, 40-59, 60-79, and 80-100 groups, respectively. Similarly, PFS generally increased with increasing PD-L1 expression, with a median PFS of 2.7, 4.2, 4.5, 7.4, and 7.7 months in the same PD-L1 categories. Supplementary Figs. S5--S7 illustrate OS, PFS, and ORR by more granular PD-L1 expression groupings. Figure 5 shows the adjusted hazard ratio of PFS and OS of patients with increasing PD-L1 scores versus patients with a PD-L1 score of 0%. As in the 1L setting, these plots suggest that OS and PFS generally increase as PD-L1 expression increases.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS and PFS in 2L NSCLC for patients treated with ICI monotherapy stratified by PD-L1 score (20-point increments). Results for OS are shown in (A) and results for PFS are shown in (B). (A) OS in 2L NSCLC. (B) PFS in 2L NSCLC.

Figure 5.

Smoothed hazard ratio and 95% CIs for OS and PFS of patients with varying PD-L1 scores. Hazard ratios are calculated as compared to a patient with a PD-L1 score of 0%. (A) Effect of PD-L1 Score on OS in 2L NSCLC. (B) Effect of PD-L1 score on PFS in 2L NSCLC.

Based on the models, the adjusted hazard ratio of OS for patients with 50% PD-L1 versus patients with 0% PD-L1 was 0.85 (95% CI, 0.69 to 1.03); the corresponding hazard ratio for PFS was 0.79 (95% CI, 0.66 to 0.94). For patients with a PD-L1 score of 100, the adjusted hazard ratio versus a patient with 0% PD-L1 was 0.55 (95% CI, 0.43 to 0.71) for OS and 0.51 (95% CI, 0.41 to 0.63) for PFS. Similar trends were found for the effect of PD-L1 on ORR (Supplementary Fig. S8). As in the 1L models, statistical tests did not suggest a significant departure from linearity for the effect of PD-L1 in these models. No significant heterogeneity was noted for either the OS model (Q = 9.5898; I2 = 1%; P = .8872) or the PFS model (Q = 16.3086; I2 = 1.9%; P = .4316).

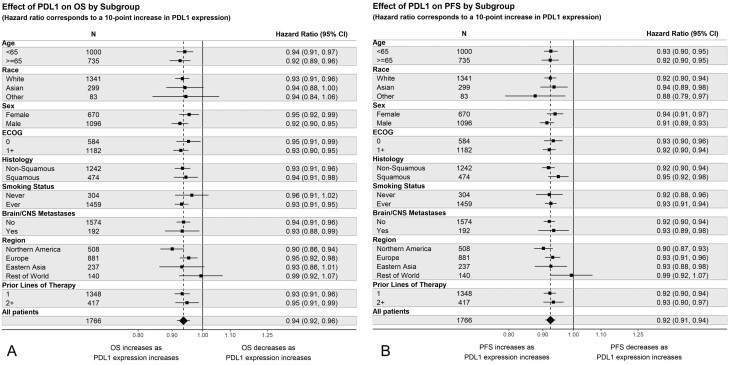

Figure 6 shows the effect of a 10% increase in PD-L1 on OS and PFS by subgroup. Covariate-adjusted comparisons of the interaction effect are presented in Supplementary Table S5. Results for ORR are presented in Supplementary Figs. S8, S9 and Supplementary Table S6. Contrary to the 1L results, these analyses do not suggest any differences in the effect of PD-L1 expression on OS or PFS across the smoking subgroups. Indeed, the effect appears to be relatively consistent across subgroups. As in the 1L analyses, the effect of increasing PD-L1 on OS may differ by region. This is supported by subgroup analyses conducted on ORR (Supplementary Fig. S9). While Figure 6 depicts overlapping CIs for these effects across the various regions, the adjusted comparisons presented in Supplementary Table S5 suggest that the effect of PD-L1 on OS and PFS may vary by region. Statistical tests for interaction further suggest that the effect of PD-L1 on OS, PFS, and ORR may be heterogeneous across regions.

Figure 6.

Effect of PD-L1 on outcomes by subgroup in 2L NSCLC. Hazard ratios correspond to a 10-point increase in PD-L1 expression. The effect of PD-L1 on outcomes is assumed linear within the Cox model. (A) Effect of PD-L1 on OS by subgroup. (B) Effect of PD-L1 on PFS by subgroup.

Discussion

This retrospective pooled analysis reports on the relationship between increasing PD-L1 expression levels and clinical outcomes to anti-PD-(L)1 monotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC treated in clinical trials. In the models explored, the effect of PD-L1 expression on outcomes appears to be linear on the log-hazards (OS and PFS) and log-odds scales (ORR). While other studies have characterized this relationship based on broad PD-L1 categories,25,26 our analyses differ in that they quantify these relationships across the continuous spectrum of PD-L1 scores. In addition, the relationship between PD-L1 expression and outcome may vary by subgroup. Across the 1L and 2L settings, analyses suggested this relationship may vary by region. Previous work has noted that immunotherapy may be more effective for smokers and patients with squamous histology.38 Our results also suggest that increasing PD-L1 expression leads to greater improvement in OS for these subgroups treated with ICI in the 1L setting, although this trend was consistent across endpoints only for the subgroup of smokers. This could be another reason why OS may vary across regions with different smoking patterns and histologic prevalence.

The strength of this analysis rests on the large sample size and granularity of the individual patient-level data from pooled clinical trials. The results presented here are retrospective, not randomized, and considered exploratory in nature. In addition, the trials included are restricted to those submitted to FDA as part of a marketing application. However, the intent of the analysis was to model the relationship between PD-L1 and outcomes rather than the treatment effect relative to a control arm. Therefore, the exclusion of other monotherapy trials is not expected to change our findings. We note that while 2L trials of ICI monotherapy were included, these results are less relevant to the current treatment era given the use of these agents in the 1L setting.

While pooling data allows for evaluation across multiple ICI therapies, such an approach relies on the assumption that the effect of PD-L1 expression on clinical outcomes is common across all studies within a particular setting. Estimation of this effect is likely to be affected by differences in patient populations, treatment effect, and assessment of PD-L1 expression. As a result, this study is limited by the use of different PD-L1 immunohistochemical antibody assays and our reliance on tumor cell PD-L1 expression as the overall measure of PD-L1 expression. This approach disregards PD-L1 expression measured in tumor-infiltrating immune cells, which is used in the SP142 assay for scoring. While it has been reported that there is a high concordance of tumor cell scores between the 22C3 and 28-8 pharmDx assays, this is not the case with SP142 and either 22C3 or 28-8.39

Our results are consistent with findings from a pooled analysis previously described in a patient population with NSCLC treated with 1L pembrolizumab at 4 academic centers.24 The larger sample size of the current pooled FDA cohort allowed for greater granularity to demonstrate that clinical outcomes improve along a continuum with increasing PD-L1 expression levels. As such, pathology reporting of specific PD-L1 expression levels rather than reporting in discrete categories (>1%, >50%, etc) would allow for a more granular understanding and could potentially aid in treatment decisions.

Our findings suggest 2 important considerations for trial designs of immunotherapy agents. First, as the impact of PD-L1 expression on outcomes may vary across regions or other patient characteristics, it is critical that future trials are multiregional and enroll a diverse patient population.40 For instance, of the 3806 patients included in these pooled analyses, only 72 were Black. Given the small sample size, no inference about the relationship between PD-L1 expression and outcomes could be conducted for this racial subpopulation. Second, these analyses highlighted the magnitude of the effect of increasing PD-L1 expression on outcomes. Previous trials have used this relationship to their advantage by enriching trial populations for high PD-L1 expression (Supplementary Table S1). However, this leaves open the question of how many patients are needed at lower PD-L1 levels to ensure that a treatment effect can be demonstrated at these lower PD-L1 levels. Trialists will need to consider this in future designs that seek to establish efficacy in populations that include such patients.

PD-L1 expression plays an important role in determining treatment considerations, particularly in the 1L treatment for patients with advanced NSCLC without targetable mutations. Options include chemotherapy in combination with anti-PD-(L)1 ICI regardless of PD-L1 expression and anti-PD-(L)1 ICI monotherapy or dual ICI combination therapy in patients with PD-L1 expression. 2–4,11–21 While our findings suggest that PD-L1 is a continuous biomarker for efficacy, only PD-L1 cutoff levels of 1% and 50% have thus far been used as thresholds for anti-PD-(L)1 ICI monotherapy for NSCLC receiving FDA approval.2,3 A recent FDA pooled analysis suggested that treatment outcomes of patients with PD-L1 expression between 1% and 49% may be improved with the combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy, vs immunotherapy alone.9 These data, taken with the current analyses, suggest that appropriate control arms for patients with PD-L1 expression of 1%-49% may include chemoimmunotherapy regimens, rather than immunotherapy alone. Further ongoing analyses, as well as the ongoing INSIGNIA trial (NCT03793179) may help elucidate the preferred regimen for patients with PD-L1 expression ≥1%.

This study was limited to the evaluation of the impact of PD-L1 expression on outcomes of ICI montotherapy. Further studies evaluating the relationship between high PD-L1 expression and clinical outcomes to anti-PD-(L)1 ICI monotherapy versus chemo-immunotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC are warranted, as no direct comparisons between these 2 therapeutic modalities have been performed. In addition, real-world data could generate additional evidence regarding the relationship between PD-L1 expression and clinical outcomes in NSCLC.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at The Oncologist online.

Contributor Information

Jonathon Vallejo, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA.

Harpreet Singh, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA; Oncology Center of Excellence, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA.

Erin Larkins, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA.

Nicole Drezner, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA.

Biagio Ricciuti, Lowe Center for Thoracic Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Pallavi Mishra-Kalyani, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA.

Shenghui Tang, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA.

Julia A Beaver, Clinical Development, Treeline Biosciences, Treeline Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA.

Mark M Awad, Lowe Center for Thoracic Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

Biagio Ricciuti acted as a consultant to Regeneron. Julia A. Beaver completed work on this publication while she was an employee at the U.S. FDA; at the time of publication, she is an employee at Treeline Biosciences. Mark M. Awad acts as a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Genentech, AstraZeneca, Mirati, Novartis, Blueprint Medicine, Abbvie, Gritstone, NextCure, and EMD Serono, and receives research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Genentech, AstraZeneca, and Amgen. The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception/design, provision of study material or patients, collection and/or assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, and final approval of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and its online Supplementary Material. The authors cannot make the data available due to privacy restrictions. The authors do not plan to make other documentation or code available.

References

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A.. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):5-29. 10.3322/caac.21254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp. Administration USFaD. Keytruda (Pembrolizumab) [Package Insert], Full Prescribing Information. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Genentech Inc. Administration USFaD. Tecentriq (Atezolizumab) [Package Insert], Full Prescribing Information. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bristol-Myers’s Squibb Company. Administration USFaD. Opdivo (Nivolumab) [Package Insert], Full Prescribing Information. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627-1639. 10.1056/nejmoa1507643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(2):123-135. 10.1056/nejmoa1504627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, et al. ; POPLAR Study Group. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10030):1837-1846. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00587-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim D-W, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1540-1550. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Akinboro O, Vallejo JJ, Mishra-Kalyani PS, et al. Outcomes of Anti-PD-(L1) Therapy in Combination with Chemotherapy Versus Immunotherapy (IO) Alone for First-Line (1L) Treatment of Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) with PD-L1 Score 1-49%: FDA Pooled Analysis. Wolters Kluwer Health; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. ; OAK Study Group. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):255-265. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, et al. First-line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(25):2415-2426. 10.1056/nejmoa1613493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078-2092. 10.1056/nejmoa1801005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hellmann MD, Paz-Ares L, Bernabe Caro R, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(21):2020-2031. 10.1056/nejmoa1910231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mok TS, Wu YL, Kudaba I, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10183):1819-1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Paz-Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy for squamous non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(21):2040-2051. 10.1056/nejmoa1810865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. ; KEYNOTE-024 Investigators. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1–positive non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823-1833. 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, et al. ; IMpower150 Study Group. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(24):2288-2301. 10.1056/NEJMoa1716948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jassem J, de Marinis F, Giaccone G, et al. Updated overall survival analysis from IMpower110: atezolizumab versus platinum-based chemotherapy in treatment-naive programmed death-ligand 1–selected NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(11):1872-1882. 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals I. Libtayo (Cemiplimab) [Package Insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/761097s016lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20. LP AP. Imfinzi (Durvalumab) [Package Insert]. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed October 31, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/761069s033lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sezer A, Kilickap S, Gümüş M, et al. Cemiplimab monotherapy for first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 of at least 50%: a multicentre, open-label, global, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397(10274):592-604. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00228-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gandhi L, Lubiniecki G, Balmanoukian A, et al. MK-3475 (Anti-PD-1 Monoclonal Antibody) for Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): Antitumor Activity and Association with Tumor PD-L1 Expression. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014:S154-S154. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2018-2028. 10.1056/nejmoa1501824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aguilar E, Ricciuti B, Gainor J, et al. Outcomes to first-line pembrolizumab in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and very high PD-L1 expression. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(10):1653-1659. 10.1093/annonc/mdz288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu Y, Wan B, Chen X, et al. ; written on behalf of AME Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. The association of PD-L1 expression with the efficacy of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy and survival of non-small cell lung cancer patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8(4):413-428. 10.21037/tlcr.2019.08.09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. An R, Zhao F, Wang L, Shan J, Wang X.. Predictive effect of molecular and clinical characteristics for the OS and PFS efficacy of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy in patients with NSCLC: a meta-analysis and systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e047663. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 11). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-247. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cochran WG. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10(1):101-129. 10.2307/3001666 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Higgins JP, Thompson SG.. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta‐analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539-1558. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG.. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Therneau T, Lumley T.. R Survival Package. R package version 3.5-7. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wickham H. ggplot2. WIREs Comput Stat. 2011;3(2):180-185. 10.1002/wics.147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kassambara A, Kosinski M, Biecek P, Fabian S.. Package ‘survminer’. Drawing Survival Curves using “ggplot2”(R package version 03 1). Package version 0.4.9. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Therneau T, Atkinson B, Ripley B, Ripley MB.. Package ‘rpart’. 2015. Accessed April 20, 2016. Available online: cran.ma.ic.ac.uk/web/packages/rpart/rpart pdf.

- 36. Prince EA, Sanzari JK, Pandya D, Huron D, Edwards R.. Analytical concordance of PD-L1 assays utilizing antibodies from FDA-approved diagnostics in advanced cancers: a systematic literature review. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;5:953-973. 10.1200/PO.20.00412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Herbst RS, Giaccone G, de Marinis F, et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of PD-L1–selected patients with NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1328-1339. 10.1056/nejmoa1917346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Teng F, Meng X, Kong L, Yu J.. Progress and challenges of predictive biomarkers of anti PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy: a systematic review. Cancer Lett. 2018;414:166-173. 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hendry S, Byrne DJ, Wright GM, et al. Comparison of four PD-L1 immunohistochemical assays in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(3):367-376. 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.11.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Food, Administration D. Enhancing the Diversity of Clinical Trial Populations—Eligibility Criteria, Enrollment Practices, and Trial Designs Guidance for Industry. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and its online Supplementary Material. The authors cannot make the data available due to privacy restrictions. The authors do not plan to make other documentation or code available.