Abstract

Background

The optimal treatment approach for hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (HR+/HER2-negative MBC) with aggressive characteristics remains controversial, with lack of randomized trials comparing cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)4/6-inhibitors (CDK4/6i) + endocrine therapy (ET) with chemotherapy + ET.

Materials and methods

We conducted an open-label randomized phase II trial (NCT03227328) to investigate whether chemotherapy + ET is superior to CDK4/6i + ET for HR+/HER2-negative MBC with aggressive features. PAM50 intrinsic subtypes (IS), immunological features, and gene expression were assessed on baseline samples.

Results

Among 49 randomized patients (median follow-up: 35.2 months), median progression-free survival (mPFS) with chemotherapy + ET (11.2 months, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 7.7-15.4) was numerically shorter than mPFS (19.9 months, 95% CI: 9.0-30.6) with CDK4/6i + ET (hazard ratio: 1.41, 95% CI: 0.75-2.64). Basal-like tumors under CDK4/6i + ET exhibited worse PFS (mPFS: 11.4 months, 95% CI: 3.00-not reached [NR]) and overall survival (OS; mOS: 18.8 months, 95% CI: 18.8-NR) compared to other subtypes (mPFS: 20.7 months, 95% CI: 9.00-33.4; mOS: NR, 95% CI: 24.4-NR). In the chemotherapy arm, luminal A tumors showed poorer PFS (mPFS: 5.1 months, 95% CI: 2.7-NR) than other IS (mPFS: 13.2 months, 95% CI: 10.6-28.1). Genes/pathways involved in BC cell survival and proliferation were associated with worse outcomes, as opposite to most immune-related genes/signatures, especially in the CDK4/6i arm. CD24 was the only gene significantly associated with worse PFS in both arms. Tertiary lymphoid structures and higher tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes also showed favorable survival trends in the CDK4/6i arm.

Conclusions

The KENDO trial, although closed prematurely, adds further evidence supporting CDK4/6i + ET use in aggressive HR+/HER2-negative MBC instead of chemotherapy. PAM50 IS, genomic, and immunological features are promising biomarkers to personalize therapeutic choices.

Keywords: CDK4/6-inhibitors, chemotherapy, breast cancer, hormone receptors, intrinsic subtypes, tertiary lymphoid structures

Optimal upfront treatment for HR+/HER2− metastatic breast cancer with aggressive characteristics remains controversial. Results of the KENDO randomized trial add to evidence supporting CDK4/6-inhibitors plus endocrine therapy instead of chemotherapy.

Implications for Practice.

The KENDO randomized trial, although closed prematurely, adds to the current evidence supporting CDK4/6-inhibitors (CDK4/6i) + endocrine therapy (ET) instead of chemotherapy in hormone receptor-positive(HR+)/HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer, including in case of aggressive features/endocrine-resistance, where randomized trials comparing the 2 strategies are scarce. Additionally, translational tissue-based analyses suggested the potential for PAM50 subtypes and ROR-P categories in predicting response to chemotherapy or CDK4/6i + ET. High tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, genomic immune signatures, and, for the first time, tertiary lymphoid structures showed favorable survival trends, especially with CDK4/6i + ET, highlighting the importance of further studying the implications of tumor biology and immune composition for optimizing therapeutic choices.

Introduction

Hormone receptor-positive(HR+)/HER2-negative breast cancer (BC) represents more than 65% of all BC.1 During many years, in the metastatic setting, all major guidelines recommended endocrine therapy (ET) as the preferable upfront treatment choice, unless in case of visceral crisis, but there were no evidences based on randomized trials supporting this recommendation, especially with regard to more recent chemotherapy (CT) and ET agents.2 In that context, the KENDO trial was initially conceived as a randomized phase II study comparing ET alone versus CT + ET as first-line in HR+/HER2-negative metastatic BC (MBC). In recent years, cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)4/6-inhibitors (CDK4/6i; ie, palbociclib, ribociclib, or abemaciclib) in combination with an aromatase inhibitor (AI) or fulvestrant for the first/second-line setting, significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to ET alone,3,4 becoming the standard upfront therapy for HR+/HER2-negative MBC.5 For this reason, the KENDO trial’s protocol was amended to compare head-to-head a CDK4/6i-based first/second-line regimen to a CT of physician’s choice, in a context of aggressive/poor endocrine sensitive disease, to demonstrate the superiority of CT +/− ET in this patient population. However, a network meta-analysis in 2019, comparing all first/second-line ET-based and CT-based regimens for HR+/HER2-negative MBC in postmenopausal women, confirmed the superior PFS of ET combinations with targeted agents with respect to endocrine monotherapies and showed similar efficacy and activity to CT-based regimens, as well.2 Subsequently, palbociclib + ET demonstrated comparable outcomes to capecitabine in the PEARL randomized phase III trial in postmenopausal patients and even superior PFS in premenopausal women in the Young-PEARL randomized phase II study.6,7 The KENDO trial was then early-stopped due to unsuccessful accrual. Here we present the results for the primary endpoint, main secondary clinical endpoints, and a set of correlative biomarker analyses in tumor tissues to identify potential prognostic and predictive genomic and immunological features.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

KENDO was a multicenter, 2-arm, group-sequential response-adaptive open-label randomized phase II trial designed at the IRCCS-IRST Meldola (Italy) to compare the efficacy and safety of CT +/− ET (concomitant or as maintenance) compared to a CDK4/6i + ET as first/second-line treatment for patients with HR+/HER2-negative metastatic or locally-advanced not resectable BC, with doubtful endocrine sensitivity, primary endocrine resistance, or characteristics of aggressiveness that made patients potentially eligible for CT according to their treating physician. Patients had to be postmenopausal women, or premenopausal women undergoing treatment with GnRH analog (GnRHa), or men, aged ≥ 18 years, with measurable disease according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) 1.1,8 or disease not measurable but evaluable. A histological diagnosis of HR+ (estrogen receptor [ER] ≥ 10% of tumor cells)/HER2-negative (according to ASCO/CAP guidelines 2018)9 BC, determined by a local laboratory on the most recent available tumor tissue was required. Patients must be CT-naïve for advanced disease, but up to one prior line of ET for MBC was allowed. Collection of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) breast tissue samples from the metastatic or primary tumor was mandatory at baseline (archived or newly obtained). ER, progesterone receptor (PgR), Ki67, and HER2 status were assessed locally according to main international guidelines.9-11 Detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria and relevant definitions are reported in Supplementary Methods.

Randomization, Masking, and Study Procedures

The patients were allocated (1:1) according to block randomization until 2 events were observed in each arm, and then according to the time-to-event adaptation of the group sequential Doubly-adaptive Biased Coin Design.

Patients in arm A received a CDK4/6i in combination with an AI, or fulvestrant,12 based on previous treatments. Patients in arm B received a CT regimen at the discretion of the treating physician among those commonly accepted as standard according to local guidelines. CT could be stopped before disease progression (PD), but not before 4-6 months, if not clinically indicated, and followed by ET (an AI or fulvestrant) as maintenance treatment. ET could be administered also concomitantly to CT. Premenopausal patients treated only with ET (in arm A or as maintenance in arm B) also received a GnRHa of physician’s choice. Crossover was allowed after PD. Treatments were continued until PD, patient’s withdrawal, or unacceptable toxicity. Study procedures are fully reported in Supplementary Methods.

Laboratory Procedures and Immunopathology

For exploratory genomic analyses a minimum of ~100 ng of total RNA was used to measure the expression of 776 genes included in the Nanostring Breast Cancer 360 (BC360) assay, on a nCounter platform (Nanostring Technologies, Seattle, WA). The full list of assessed genes and signatures is reported in Supplementary Table S1. The research-based PAM50 assay was used for intrinsic subtyping and risk-of-relapse (ROR)-P score calculation13-15 (Supplementary Methods). In addition, the presence of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) was evaluated with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, by assessing the percentage of tumor stromal area occupied by lymphocytes, following international recommendations.16 The presence of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS)17 was also assessed in H&E slides from FFPE samples (Supplementary Methods). Tumor immune pattern was then defined as inflamed, excluded, or desert, according to the amount and spatial distribution of the inflammatory infiltrate present.18

Study Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

The study’s primary objective, after a protocol amendment (protocol included as Supplementary Material), was to demonstrate the superiority of CT +/− concomitant and/or maintenance ET over CDK4/6i + ET in terms of PFS. Secondary objectives reported in this analysis included: time-to-treatment-failure, overall response rates (ORR) based on best response, duration of response (DOR), clinical benefit rate (CBR), OS, toxicity (CTCAE version 5.0), correlative exploratory prognostic and predictive biomarker analyses on baseline tumor tissue (primary tumor or metastatic tissue, depending on which sample was used for study inclusion).

Descriptive statistics were reported for patients and tumor characteristics. Time-to-event data were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves and comparisons between cohorts of interest were performed using the log-rank test. Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using Cox proportional-hazard models. Two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each HR were esteemed. Logistic regressions were conducted to explore associations with ORR, CBR, and TLS by calculating odds ratios (OR) with 2-sided 95% CI. Predictivity was assessed with receiver operator characteristic curves and evaluation of area under curve (AUC) with 95% CI.

The maximally selected rank statistics (MSRS) method19 was used to identify exploratory cut-offs for genomic signatures, genes of interest or TILs, and assess their association with PFS or OS. Since the study did not reach the required sample size (n = 150), all the analyses presented in this report are intended to be hypothesis-generating, with a significance level set at P < .05, without adjustments for multiplicity.

Baseline gene expression difference between the 2 treatment cohorts was assessed with 2-class unpaired SAM analysis, with a false discovery rate (FDR) ≤ 5%.14

All study objectives, with endpoint definitions and detailed statistical analysis are reported in Supplementary Methods.

All statistical analyses were performed with R version 3.6.120 and SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp. Released 2016. IBM SPSS Statistics for MacOS, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) for MacOSX. The study is registered with EudraCT number 2016-004107-31 and clinical trial registration number NCT03227328.

Results

Population Characteristics and Treatment Details

A total of 52 patients from 10 Italian institutions were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 49 were ultimately randomized, with 17 (34.7%) being assigned to arm A, and 32 (65.3%) to arm B. More details on patient inclusion and tissue availability are reported in Supplementary Fig. S1.

All patients assigned to a specific treatment arm received at least one dose of the preplanned medication. No significant differences at baseline were observed between the 2 treatment arms in terms of main clinicopathological and tumor molecular features, except for higher proportion of TLS in arm B (P = .013). Population characteristics are fully reported in Table 1. In arm A, CT alone was only administered in 6.3% patients, while in most cases (62.5%) patients stopped CT after 4-6 months and received ET maintenance. Concomitant and/or maintenance ET consisted exclusively of an AI. The majority of patients in arm B received capecitabine-based regimens (68.8%) and none received a regimen containing both anthracycline and taxanes. The only taxane administered was paclitaxel in weekly schedule. The treatments administered are fully reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

Population characteristics.

| Population demographics | ARM A | ARM B | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| 17 | 34.7 | 32 | 65.3 | ||

| Age at randomization | |||||

| Median | 64 | — | 62 | — | .366 |

| IQR | 55-67 | 50-69 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White/Caucasian | 17 | 100.0 | 32 | 100.0 | — |

| Other | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 17 | 100.0 | 32 | 100.0 | — |

| Male | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Menopausal status at randomization | |||||

| Premenopausal | 2 | 12.5 | 6 | 21.4 | .460 |

| Postmenopausal | 14 | 87.5 | 22 | 78.6 | |

| Overall | 16 | 94.1 | 28 | 87.5 | |

| Metastatic status at randomization | |||||

| De novo | 3 | 17.6 | 12 | 37.5 | .151 |

| Relapsed | 14 | 82.4 | 20 | 62.5 | |

| Neo/adjuvant CT in relapsed patients | |||||

| Yes | 8 | 57.1 | 8 | 38.1 | .268 |

| No* | 6 | 42.9 | 13 | 61.9 | |

| Overall | 14 | 82.4 | 21 | 65.6 | |

| Neo/adjuvant ET in relapsed patients | |||||

| Yes | 14 | 82.4 | 26 | 81.3 | .924 |

| No* | 3 | 17.6 | 6 | 18.8 | |

| Study treatment line | |||||

| First | 16 | 94.1 | 28 | 87.5 | .466 |

| Second | 1 | 5.9 | 4 | 12.5 | |

| Number of metastatic sites | |||||

| <3 | 10 | 58.8 | 22 | 68.8 | .487 |

| ≥3 | 7 | 41.2 | 10 | 31.2 | |

| Tissue sample for randomization | |||||

| Primary tissue | 7 | 41.2 | 17 | 53.1 | .426 |

| Metastatic tissue | 10 | 58.8 | 15 | 46.9 | |

| Metastatic spread | |||||

| Bone-only | 3 | 17.6 | 6 | 18.8 | .969 |

| Non visceral/non-bone-only | 7 | 41.2 | 12 | 37.5 | |

| Visceral | 7 | 41.2 | 14 | 43.7 | |

| Endocrine sensitivity | |||||

| Sensitive | 13 | 76.5 | 29 | 90.6 | .178 |

| Primary resistant | 4 | 23.5 | 3 | 9.4 | |

| Secondary resistant | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Estrogen receptor (%) | |||||

| ER 10-50% | 2 | 11.8 | 3 | 9.4 | .793 |

| ER > 50% | 15 | 88.2 | 29 | 90.6 | |

| Progesterone receptor (%) | |||||

| <20 | 6 | 35.3 | 14 | 43.8 | .566 |

| ≥20 | 11 | 64.7 | 18 | 56.3 | |

| KI67 (%) | |||||

| <20 | 4 | 30.8 | 7 | 31.8 | .949 |

| ≥20 | 9 | 69.2 | 15 | 68.2 | |

| Overall | 13 | 76.5 | 22 | 68.8 | |

| PAM50 intrinsic subtype | |||||

| Luminal A | 3 | 17.6 | 7 | 24.1 | .721 |

| Luminal B | 6 | 35.3 | 10 | 34.5 | |

| HER2E | 1 | 5.9 | 4 | 13.8 | |

| Basal-like | 2 | 11.8 | 1 | 3.4 | |

| Normal-like | 5 | 29.4 | 7 | 24.1 | |

| Overall | 17 | 100.0 | 29 | 90.6 | |

| ROR-P | |||||

| Low | 3 | 17.6 | 5 | 17.2 | .988 |

| Intermediate | 9 | 52.9 | 16 | 55.2 | |

| High | 5 | 29.4 | 8 | 27.6 | |

| Overall | 17 | 100.0 | 29 | 90.6 | |

| Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (%) | |||||

| Median | 3 | — | 4.5 | — | .129 |

| IQR | 1-5 | — | 2—12.8 | — | |

| TLS# (w/wo germinal centers) | |||||

| Yes | 2 | 12.5 | 14 | 50.0 | .013 |

| No | 14 | 87.5 | 14 | 50.0 | |

| Overall | 16 | 94.1 | 28 | 87.5 | |

| Immune pattern | |||||

| Inflamed | 2 | 12.5 | 7 | 25.0 | .295 |

| Excluded | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 7.1 | |

| Desert | 14 | 87.5 | 19 | 67.9 | |

| Overall | 16 | 94.1 | 28 | 87.5 | |

Endocrine resistance was defined according to ESMO guidelines criteria.5 Immune pattern was defined according to Chen DS et al.18P-values are referred to chi-square or Fisher’s exact test in case of proportions, where indicated, or to Mann-Whitney U test in case of continuous variables. Significant P-values are reported in italics.

Overall identifies the number of patients per arm for whom the information is available for a specific variable.

*Includes patients with de novo metastatic disease.

#Including every lymphoid aggregates more or less organized.

Abbreviations: Arm A: CDK4/6i-based arm; Arm B: chemotherapy-based arm; ER: estrogen receptor; IQR: interquartile range; ROR-P: PAM50 risk of relapse score including subtypes and proliferation signatures.

Table 2.

Study treatments.

| Study treatment details | Study population | |

|---|---|---|

| N | % | |

| 49 | 100.0 | |

| ET + CDK4/6i | 17 | 34.7 |

| CDK4/6i | ||

| Palbociclib | 7 | 41.2 |

| Ribociclib | 6 | 35.3 |

| Abemaciclib | 4 | 23.5 |

| Endocrine partner | ||

| Aromatase inhibitor | 10 | 58.8 |

| Fulvestrant | 7 | 41.2 |

| Chemotherapy (±ET ) | 32 | 65.3 |

| Strategy | ||

| Concomitant ET + maintenance | 10 | 31.3 |

| Only maintenance ET | 20 | 62.5 |

| Chemotherapy alone | 2 | 6.3 |

| CT type | ||

| Anthracycline-based | 6 | 18.8 |

| Taxane-based | 4 | 12.5 |

| Capecitabine monotherapy | 14 | 43.8 |

| Capecitabine + vinorelbine | 8 | 25.0 |

| Time to study treatment start from metastatic diagnosis | ||

| Overall population median (months) | 1.1 | — |

| Overall population IQR (months) | 0.6-1.5 | — |

| Arm A median (months) | 0.5 | — |

| Arm A IQR (months) | 0.8-1.1 | — |

| Arm B median (months) | 1.2 | — |

| Arm B IQR (months) | 0.8-2.0 | — |

Taxane-based regimens consisted in intravenous (i.v.) weekly (qw) paclitaxel; anthracycline-based regimens include: i.v. liposomal doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide every 3 weeks (q3w) and standard doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide q3w.

Abbrteviations: CT, chemotherapy; ET, endocrine therapy; CDK4/6i, CDK4/6-inhibitors; IQR, interquartile range; arm A, ET + CDK4/6i; arm B, CT(+/−ET).

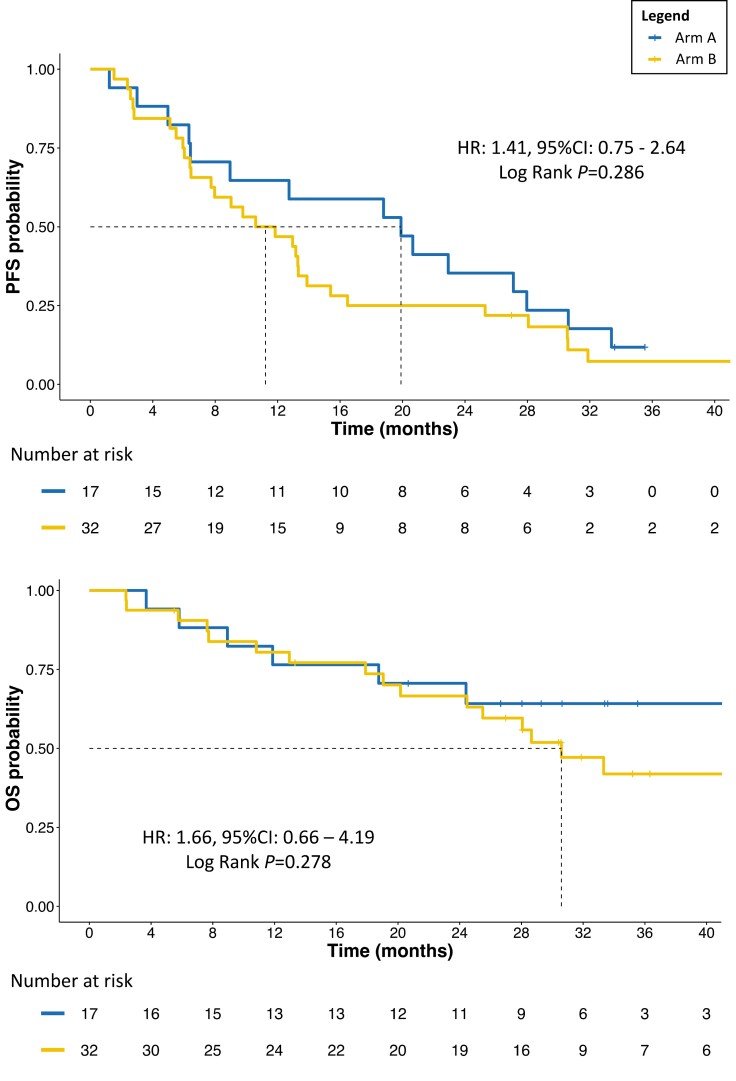

Primary Endpoint and Other Efficacy and Activity Endpoints

At a median follow-up of 35.2 months (95% CI: 30.6-43.7), 15 (88.2%) patients in arm A and 29 (90.6%) patients in arm B had experienced a PFS event, with a median PFS (mPFS) for arm A of 19.9 months (95% CI: 9.0-30.6) and mPFS for arm B of 11.2 months (95% CI: 7.7-15.4; B vs. A HR: 1.41, 95% CI: 0.75-2.64, P = .289). The median OS (mOS) for arm A was not reached (NR) at the time of analysis (95% CI: 24.4 months-not estimable[NE]), while for arm B it was 30.6 months (95% CI: 24.5-NE), although the difference was not statistically significant (P = .283; Fig. 1). Four deaths were observed during the study directly associated with tumor progression, 1 in arm A and 3 in arm B. Crossover upon PD concerned 4 patients in total, 3 from the CT arm and 1 from the CDK4/6i arm.

Figure 1.

PFS and OS according to treatment arm. Abbreviations: PFS: progression-free survival; OS: overall survival; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; arm A: CDK4/6i + ET; arm B: chemotherapy +/− concomitant or maintenance ET.

No patient stopped the treatment due to toxicity, withdrawal, or other causes unrelated to PD or death. No standard clinicopathological variables (Supplementary Methods) were found to be significantly associated with PFS and OS (all P > .05).

Although not significant (P = .260), ORR with CDK4/6i + ET doubled the ORR observed in the CT arm (31.3% vs. 16.7%), with numerically longer DOR (12.6 vs. 7.0 months, P = .368). CBR was similar between the 2 arms (Supplementary Table S2).

Safety analysis is reported in Supplementary Results.

Genomic Correlative Biomarker Analyses

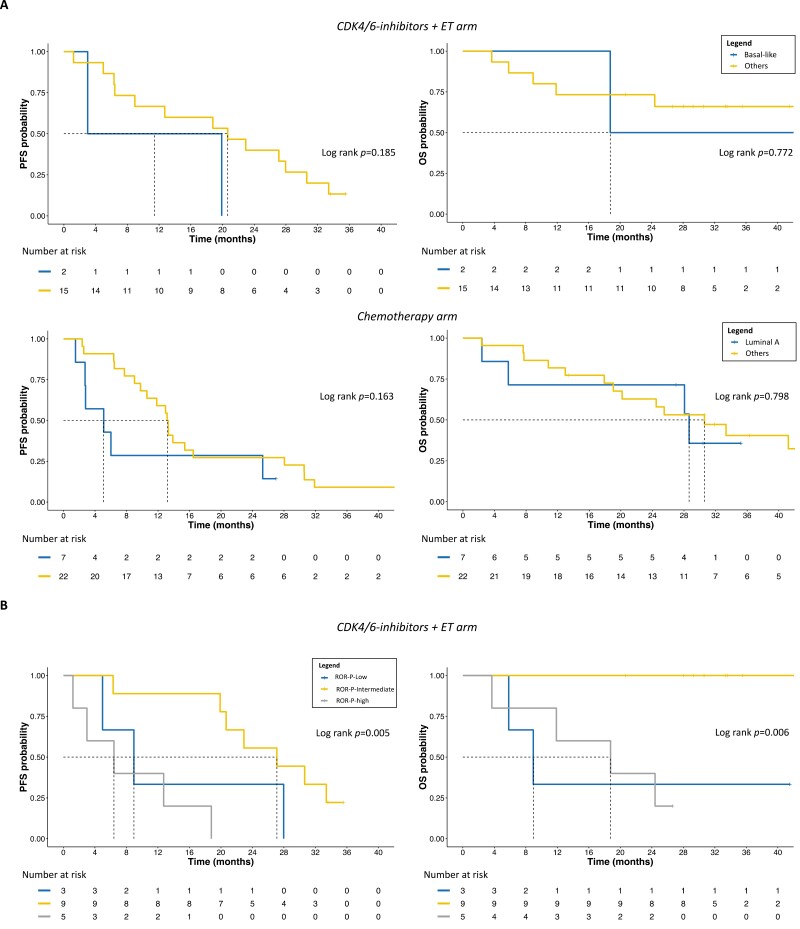

When we applied the PAM50 algorithm for intrinsic subtyping in baseline tumor samples, overall, 26 (56.5%) tumors were found to be luminal and 20 (43.5%) were non-luminal (Table 1). The most prevalent PAM50 ROR-P score category was ROR-intermediate (54.3%; Table 1). No significant gene expression differences (all FDR > 5%) and no differences in the distribution of PAM50 intrinsic subtypes (IS) and ROR-P categories were observed between the 2 cohorts (Supplementary Fig. S2; Table 1). In general, luminal versus non-luminal tumors were not dissimilar in terms of PFS and OS (Supplementary Fig. S3). However, when dissecting by the treatment arm, we noticed that under CDK4/6 inhibition and ET, basal-like tumors showed the numerically worse PFS (median 11.4 months, 95% CI: 3.00-NE) and OS (median 18.8 months, 95% CI: 18.8-NE), compared to the other subtypes (mPFS: 20.7 months, 95% CI: 9.00-33.4; mOS: NR, 95% CI: 24.4-NE; Fig. 2). Conversely, in the CT arm, luminal A tumors performed numerically worse in PFS (median 5.1 months, 95% CI: 2.7-NE) than other IS (median 13.2 months, 95% CI: 10.6-28.1). Nevertheless, OS was similar between luminal A (median 28.7 months, 95% CI: 5.8-NE) and other IS (median 30.6 months, 95% CI: 20.2-NE; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

PFS and OS according to PAM50 IS and ROR-P. Abbreviations: A, PFS and OS in arm A and B based on PAM50 IS; B, PFS and OS in arm A, according to ROR-P category; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; IS, intrinsic subtypes; ET, endocrine therapy; ROR, risk-of-relapse score.

When comparing the performance of each IS according to the treatment arm, we noticed that luminal B and HER2-enriched (HER2E) tumors showed very similar PFS and OS (not shown). Differently, luminal A, if treated with CT rather than CDK4/6i + ET, showed numerically worse PFS (mPFS 5.1 [95% CI: 2.7-NE] vs. 20.7 months [95% CI: 6.3-NE]) and OS (mOS 28.7 [95% CI: 5.8-NE] vs. NR [95% CI: NE-NE]), whereas basal-like showed the opposite (mPFS 13.3 [95% CI: NE-NE] vs. 11.4 months [3.0-NE]; mOS 41.2 [95% CI: NE-NE] vs. 18.8 months [95% CI: 18.8-NE]; Supplementary Fig. S3). To note, one of the 2 basal-like tumors in arm A was associated with a germline BRCA2 mutation and showed significantly higher PFS and OS than the other basal-like in the same arm (mPFS 19.9 vs. 3.0 months and mOS 47.4 vs. 18.8 months, respectively).

In terms of ROR-P, despite not being associated with PFS and OS as continuous variable (P > .05 in all cases), in arm A, ROR-P-intermediate versus ROR-P-low/-high tumors showed significantly better PFS (HR: 0.21, 95% CI: 0.06-0.67, P = .009) and OS (HR < 1.0, 95% CI not evaluable, log-rank P = .001; Fig. 2). In arm B, there were no significant differences in PFS and OS, or specific trends, based on ROR-P (log-rank P = .558 and P = .839, respectively).

We performed several univariate survival analyses to evaluate the association with PFS and OS of all genes of interest, as continuous variables. CD24 was the only gene showing a significant association with PFS in both arms A (HR: 1.50, P = .040) and B (HR: 1.46, P = .025). The association was independent of the treatment arm and main clinicopathological/molecular features (adjusted HR: 2.23, 95% CI: 1.36-3.65, P = .001). More details are reported in Supplementary Results.

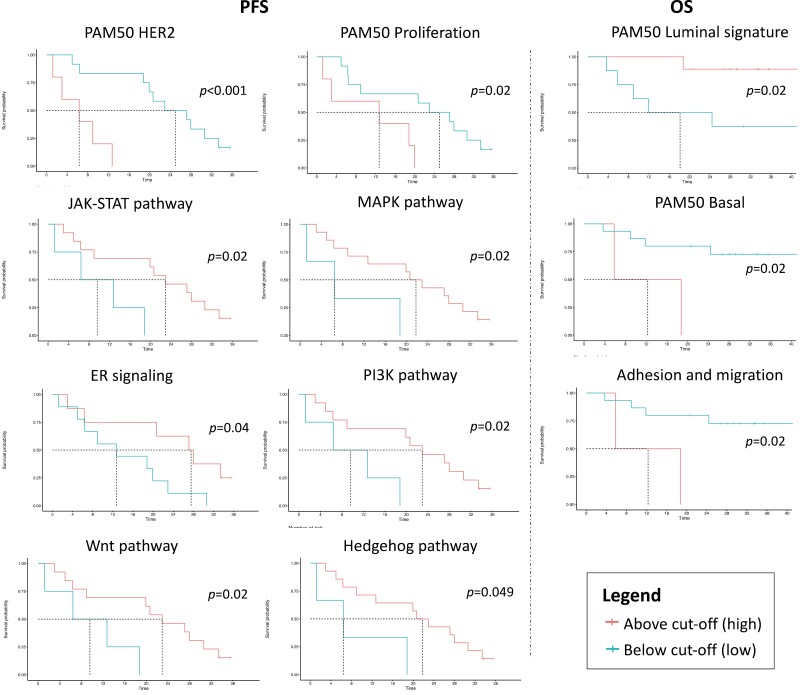

We subsequently calculated several biologic signatures of interest associated with biological pathways or BC biology (Supplementary Table S1). When considered as continuous variables, none of them was associated with PFS or OS. When dichotomizing them by using the MSRS method, we observed that in the CDK4/6i-treated cohort, higher levels of hedgehog, JAK-STAT, MAPK, PI3K, and Wnt pathway signatures, PAM50 HER2 and proliferation, and ER signaling signatures were significantly associated to better PFS and OS (except the HER2 and Wnt signatures; Fig. 3). Higher levels of adhesion, migration, and PAM50 basal signatures were significantly associated with worse OS, while higher levels of the PAM50 luminal signature provided better OS (Fig. 3). Differently, in arm B, only higher levels of the PAM50 luminal and Notch pathway signatures were significantly associated with better PFS (P = .02 and P = .04), with the former also associated with better OS (P = .02; not shown).

Figure 3.

Significant associations with survival outcomes of selected PAM50 and BC360 signatures in arm A. The cut-offs were calculated using the Maximally Selected Rank Statistics method. Abbreviations: PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; ER, estrogen receptor.

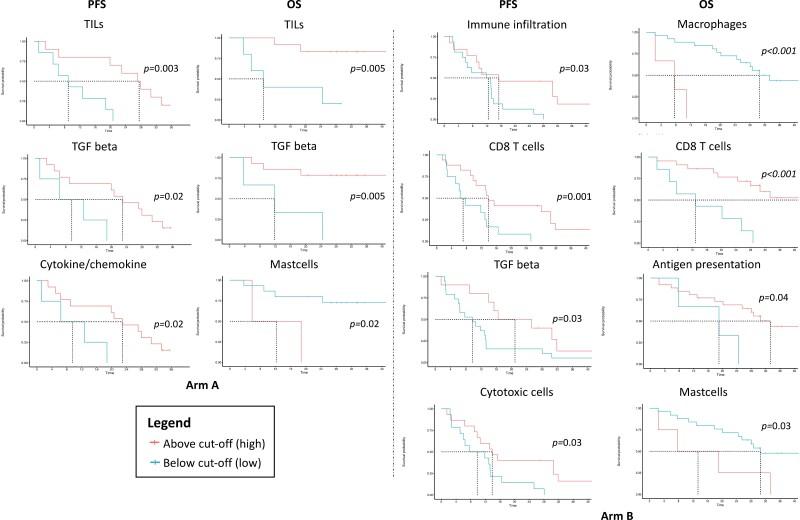

Immune Biomarker Analyses

None of the immunologic signatures assessed (Supplementary Table S1) was significantly associated with PFS, or OS, as continuous variable. When dichotomizing them according to the MSRS method, we observed that higher levels of the TGF-beta signature were significantly associated with better PFS and OS in arm A and PFS in arm B, higher levels of a cytokine/chemokine signature were associated with better PFS in arm A, and higher levels of a mast cells signature was associated with worse OS in both arms. In arm B, higher levels of a macrophages signature and an antigen presentation signature were associated with worse and better OS, respectively, whereas higher levels of an immune infiltration signature and cytotoxic cells were associated with better PFS and higher levels of a CD8 T-cell signature were associated with better PFS and OS (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Significant associations with PFS/OS of TILs and immune signatures. The cut-offs were calculated using the Maximally Selected Rank Statistics method. Abbreviations: PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; TILs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.

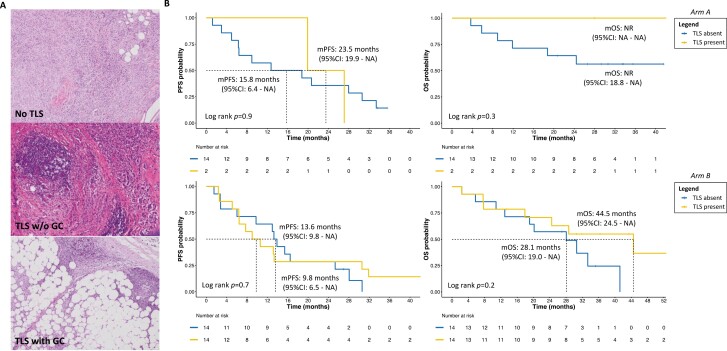

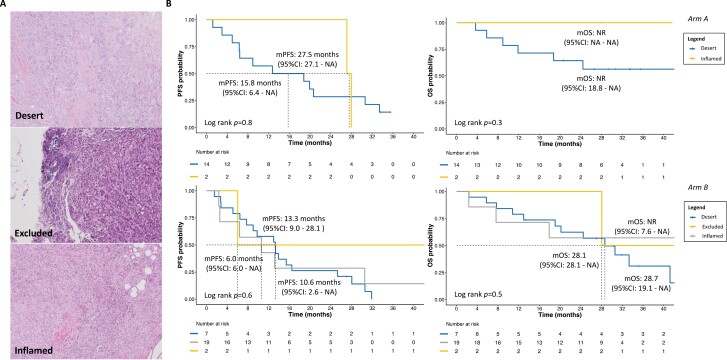

Regarding immunologic feature at immunohistochemistry (IHC), after applying the MSRS method, we observed that higher TIL levels were significantly associated with better PFS (P = .003) and OS (P = .005) in arm A, but not in arm B (Fig. 4). Also, in arm A, the immune desert pattern and absence of TLS were numerically associated with poorer outcomes than immune inflamed pattern and presence of TLS, with or without germinal centers (GC; Figs. 5, 6 and Supplementary Results). In arm B, patients with immune inflamed tumors, compared to immune desert and excluded did not reach mOS at the time of analysis, and the presence of TLS showed numerically longer OS (Figs. 5, 6; Supplementary Results).

Figure 5.

Survival trends according to TLS presence and treatment arm. (A) Representative images of TILs infiltration without TLS, with TLS and GC or without GC, at hematoxylin and eosin staining. All pathology images in these panels are magnified at 10×. (B) Exploratory Kaplan-Meier curves of PFS and OS according to study population, based on presence/absence of TLS. The “TLS present” category included TLS with/without clearly visible GC. Abbreviations: TILs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; TLS, tertiary lymphoid structures, including every lymphoid aggregates more or less organized; w/o, without; GC, germinal center; m, median; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached; NA, not assessable.

Figure 6.

Survival trends according to immune pattern and treatment arm. (A) Representative images of different immune infiltration patterns at hematoxylin and eosin staining. All pathology images in these panels are magnified at 10X. (B) Exploratory Kaplan-Meier curves of PFS and OS according to study population, based on immune infiltration pattern. Abbreviations: m, median; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; CI, confidence interval; NR, not reached; NA, not assessable.

A trend for association with ORR was observed for the immune inflamed pattern and TLS presence in arm A (OR > 1.0 in both cases), not in arm B.

In our cohort, TILs were weakly positively correlated to the HER2E score, antigen presentation, macrophages, CD8 T cells, immune infiltration and cytotoxic cells signatures and LAG3 (representing exhausted T cells) levels and moderately positively correlated to CD19 levels (Supplementary Fig. S4; Supplementary Table S3).

Finally, TILs (OR: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.12-1.75, P = .004), CD19 (OR: 1.81, 95% CI: 1.17-2.81, P = .008), and CXCL13 (OR: 2.57, 95% CI: 1.47-4.51, P = .001) mRNA levels were significantly associated to the presence of TLS, differently from PAM50 signatures, other immune genes/signatures and ROR-P (all P > .05). CD19 and CXCL13 predicted TLS presence with an AUC of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.66-0.95) and 0.83 (95% CI: 0.70-0.97), respectively, demonstrating very good predictive capacity. Exploratory cut-offs obtained with Youden Index are reported in Supplementary Fig. S4.

Discussion

The KENDO randomized phase II trial did not complete the planned accrual, thus lacking sufficient statistical power to demonstrate the superiority of upfront CT +/− ET with respect to CDK4/6i + ET in HR+/HER2-negative MBC with characteristics of aggressiveness and/or endocrine resistance. Instead, although not statistically significant, clinically meaningful PFS and OS improvements with CDK4/6i + ET were observed. Results were in line with recent evidence from 3 randomized trials, including the recent RIGHT-Choice, where a first-line ribociclib-based regimen was superior to multiagent CT in patients with aggressive disease, including visceral crisis.6,7,21 Notably, ET was never added to CT or administered as maintenance after stopping CT before PD in previous trials. In the KENDO, it did not seem to add any additional benefit. We then performed a large set of exploratory correlative biomarker analyses to evaluate the prognostic and/or predictive role of genomic tumor and immune features, on baseline tumor samples.

BC IS are biologic entities with prognostic and predictive role, beyond standard IHC parameters,15 including in HR+ MBC.22 Luminal A is the subtype usually associated with the best prognosis, whereas basal-like is the subtype experiencing the worst, according to the published literature.22 Although in HR+/HER2-negative BC the vast majority of tumors are molecularly luminal A or B, in advanced stage the proportion of aggressive, less ET-sensitive, non-luminal IS is higher than in early setting.23 In fact, in our study, where >50% tumor samples came from metastatic biopsies, 43.5% tumors were non-luminal. In the KENDO trial, despite the absence of PFS and OS difference between luminal and non-luminal tumors globally, interesting trends were observed according to treatment arm. Namely, basal-like tumors under CDK4/6i + ET had shorter PFS and OS compared to other subtypes, while in the CT cohort, luminal A were those performing worse. Consistent findings were observed when comparing separately luminal A in arm A versus B and basal-like in arm A versus B, although the restricted number of cases requires caution. Validation in more adequately powered studies is needed to draw more solid conclusions.

To note, one of the 2 basal-like tumors in arm A was germline BRCA2-mutant and showed exceptional survival outcomes. Similar responses in BRCA-mutant patients were observed in some reports, although the evidence is conflicting and mostly pointing toward worse prognosis, so far.24-26

Interestingly, ROR-P was prognostic only in the CDK4/6i arm. ROR-P takes into account the expression of proliferation-related and tumor biology-related genes. It might be possible that such a parameter could be able to identify tumors with biological features that make them specifically sensitive to a combination of drugs that both target tumor biology (ie, ET) and proliferation (ie, CDK4/6i). In fact, it was the intermediate cohort to perform better in PFS/OS, suggesting that ROR-P-low tumors might have biological features that make them less sensitive to CDK4/6 inhibition (eg, less proliferative) and ROR-P-high might be too aggressive, requiring more escalated strategies. In this perspective, biologically driven approaches might be envisioned; for example, basal-like might undergo treatment with CT-based regimens, luminal A/B and ROR-P-high tumors might receive additional target therapies (eg, AKT, HDAC, or mTOR inhibitors) in combination with a CDK4/6i + ET backbone, etc. Interestingly, the ongoing SOLTI-HARMONIA (NCT05207709) is the first randomized phase III trial attempting to tailor the treatment choice for HR+/HER2-negative MBC by selecting patients based on PAM50 IS, thus according to tumor biology beyond IHC HR status.

Noteworthy, higher levels of expression of some genes and especially genomic signatures associated with cancer proliferation and survival (eg, PI3K, MAPK, Hedgehog, Wnt, JAK-STAT, and ER signaling) seemed to be prognostically favorable under CDK4/6i + ET, with detrimental or no effect under CT. A biological environment more prone to respond to a therapeutic regimen targeting ER signaling/ER-mediated proliferation and high proliferating cells might be at the basis of this finding. Considering that baseline gene expression did not differ between the 2 study cohorts, this result seems to further support the concept that treatment strategies adapted on tumor biology, should be actively explored in a complex disease like HR+/HER2-negative MBC, where targeting single gene mutations has been beneficial only in a minority of cases.27-32 In this view, the recent identification of complex BC biological profiles in ctDNA, significantly prognostic and predictive of response to CDK4/6i,33 points toward a similar trajectory.

The only gene which expression was found to be significantly associated with prognosis in both cohorts was CD24. This gene codifies for a small glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored cell surface molecule, that is predominantly found in immune cells but is also frequently upregulated in human tumors.34 Besides immunomodulatory features,35 in solid tumors, CD24 is also considered an indicator of cancer stemness, controlling cell migration, invasiveness, and proliferation.34

This is, as far as we know, the first report on CD24 prognostic role in HR+/HER2-negative MBC in a prospectively-recruited human patient cohort. This result is coherent with higher CD24 mRNA levels being associated with shorter relapse-free survival and higher risk of developing distant metastases in the TCGA dataset.36 In our study, higher levels of CD24 were independently associated with worse PFS. Notably, the targeting of CD24 protein has already proved to be viable in other cancer models.35 Being a surface antigen, either immune-checkpoint inhibitors, chimeric antigen receptor T cells, or novel potent antibody-drug conjugates targeting CD24 might be innovative strategies worthy of pursuing also in HR+ BC.37-39

Finally, we explore the immune composition of baseline tumor samples detecting TILs, TLS with/without GC, and several genomic immune signatures. In general, only a minority of tumors were inflamed and TILs levels were mostly low.40 In this context, TLS were present in less than half of patient and the presence of GC was rare. TLS have been associated with better prognosis in several cancers, including BC, and might also correlate with better response to immunotherapy.17,41-43 However, detecting TLS is not easy because of heterogenous methodologies, definitions and, especially in BC, pathologists’ inexperience, and scarcity of dedicated training resources.41,44 We found that CD19 and CXCL13 mRNA levels were significantly associated with TLS, with very good predictive capabilities. This finding is consistent with other evidences44,45 and might represent a way to overcome classical pathology detection issue, with a standardized and reproducible methodology, if further confirmed in wider BC cohorts.

Notably, at least in this population, correlations between IHC and genomic immune signatures or immune cell-representing genes were poor, except for the moderate positive correlation between CD19 and TILs. Interestingly, higher levels of TILs, presence of TLS, and immune inflamed pattern were associated with better outcomes in the CDK cohort, along with TGF-beta and cytokine/chemokine-related signatures, but not in the CT arm. Conversely, higher levels of signatures associated with CD8/cytotoxic immune response and immune infiltration were associated with better outcomes only in the CT cohort. It is not clear whether these findings are related to chance or not, but implications might be that, first, different types of immune response might be at the basis of differential interaction with CT or CDK4/6i-based regimens. Second, CT disrupts the immune system much more than CDK4/6i, as also testified by higher rates of febrile neutropenia.2 This might have an implication on the prognostic impact of immune infiltrates. Moreover, CDK4/6i seem to exert some immunomodulatory effect which might also play a role in their anti-tumor efficacy.46 The therapeutic relevance of this interplay requires more study.

This trial is not exempt from limitations. The more obvious is the lack of power to infer the primary endpoint. While this is a key limitation, it is also important to consider that very few studies have compared in a randomized fashion CDK4/6i + ET with CT. Moreover, some of the most effective CT regimens for HR+/HER2-negative BC were used in the KENDO. Another limitation is that being the study underpowered, most of the analyses carried out did not reach statistical significance, hence only apparently relevant numerical trends could be discussed in most cases, making our results essentially hypothesis-generating. At the same time, we believe that the statistically significant results observed acquire more relevance in this context. Worth nothing, while in principle the trial was open to recruit patients in the first and second-line setting, ~90% of ultimately included patients received the study treatment in first line, making final results sufficiently homogenous in this regard. Importantly, randomization substantially worked in balancing the 2 treatment cohorts with regard to main baseline features, making differential prognostic findings on genomic and immunologic biomarkers between the 2 cohorts more intriguing.

To conclude, in the KENDO trial, in line with current evidence, there was no apparent benefit from using CT instead of CDK4/6i + ET in first/second line of chemo-naïve patients with aggressive/scarcely endocrine sensitive HR+/HER2-negative MBC. Exploratory biomarker analyses suggested a potential role for biological tumor features (eg, PAM50 IS, ROR-P) and microenvironment immunological composition (eg, TILs and TLS) in guiding therapeutic choices in this context. CD24 seemed to be a potential therapeutic target, and mRNA-based CD19 and CXCL13 could act as methodologically standardized predictors of TLS presence. Adequately powered studies are now needed to confirm all of these exploratory findings.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at The Oncologist online.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and their families/caregivers for their participation. We thank the following KENDO study investigators for their contribution in study accrual: Dr. Laura Amaducci (Faenza), Dr. Lorenzo Gianni (Rimini), Dr. Fabrizio Artioli (Carpi), Dr. Luigi Cavanna (Piacenza), Dr. Daniele Generali (Cremona), Dr. Andrea Bonetti (Legnago), Dr. Giancarlo Bisagni (Reggio Emilia), Dr. Antonio Frassoldati (Ferrara), and Dr. Filippo Giovanardi (Reggio Emilia), all in Italy. Dr. Francesco Schettini is supported by a Rio Hortega contract from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII). However, the findings and hypothesis generated are solely of the article’s authors.

Contributor Information

Francesco Schettini, Translational Genomics and Targeted Therapies in Solid Tumors Group, August Pi I Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain; Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Michela Palleschi, Department of Medical Oncology, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) “Dino Amadori,” Meldola, Italy.

Francesca Mannozzi, Unit of Biostatistics and Clinical Trials, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) “Dino Amadori,” Meldola, Italy.

Fara Brasó-Maristany, Translational Genomics and Targeted Therapies in Solid Tumors Group, August Pi I Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain.

Lorenzo Cecconetto, Department of Medical Oncology, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) “Dino Amadori,” Meldola, Italy.

Patricia Galván, Translational Genomics and Targeted Therapies in Solid Tumors Group, August Pi I Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain.

Marita Mariotti, Department of Medical Oncology, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) “Dino Amadori,” Meldola, Italy.

Alessia Ferrari, UO Medicina Oncologia, Ospedale Ramazzini, Azienda USL di Modena, Carpi, Italy.

Emanuela Scarpi, Unit of Biostatistics and Clinical Trials, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) “Dino Amadori,” Meldola, Italy.

Anna Miserocchi, Unit of Biostatistics and Clinical Trials, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) “Dino Amadori,” Meldola, Italy.

Oriana Nanni, Unit of Biostatistics and Clinical Trials, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) “Dino Amadori,” Meldola, Italy.

Esther Sanfeliu, Medical Oncology Department, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Department of Pathology, Biomedical Diagnostic Center, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain.

Aleix Prat, Translational Genomics and Targeted Therapies in Solid Tumors Group, August Pi I Sunyer Biomedical Research Institute (IDIBAPS), Barcelona, Spain; Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Cancer Institute and Blood Diseases, Hospital Clínic of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Breast Cancer Unit, Institute of Oncology Barcelona (IOB), Quirónsalud, Barcelona, Spain; Reveal Genomics, Barcelona, Spain.

Andrea Rocca, Department of Medical, Surgical and Health Sciences, University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy.

Ugo De Giorgi, Department of Medical Oncology, IRCCS Istituto Romagnolo per lo Studio dei Tumori (IRST) “Dino Amadori,” Meldola, Italy.

Funding

This work was supported by research grant from Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco (grant number FARMA125RHR). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding authors had full access to all of the data in the study and final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Conflict of Interest

Francesco Schettini reports honoraria from Novartis, Gilead and Daiichy-Sankyo for educational events/materials and travel expenses from Novartis, Gilead and Daiichy-Sankyo. Michela Palleschi reports honoraria for educational events/materials from Novartis, Daiichy-Sankyo, Gilead and travel, accommodations, and/or expenses from Grant from Novartis. Ugo De Giorgi reports a consulting or advisory role for Amgen, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Clovis Oncology, Dompé Farmaceutici, Eisai, Ipsen, Janssen, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and PharmaMar; research funding (institution) from AstraZeneca, Roche, and Sanofi; and travel, accommodations, and/or expenses from Ipsen and Pfizer. Aleix Prat has received grants or contracts from Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Roche, NanoString Technologies, Medica Scientia Innovation Research, Celgene, Astellas, and Pfizer; has received grants or contracts paid to his institution from Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Roche, Novartis, Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, and AstraZeneca; has received consulting fees from Roche, Pfizer, Novartis, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Puma, Oncolytics Biotech, MSD, Guardant Health, Peptomyc, Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, and AstraZeneca; has received payment or honoraria from Roche, Pfizer, Novartis, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, NanoString Technologies, and Daiichi Sankyo; has received payment or honoraria paid to his institution from NanoString Technologies; has participated on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Oncolytics Biotech, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Peptomyc, and Roche; has served in a leadership or fiduciary role for Reveal Genomics and IOB Quironsalud; has stock ownership in Reveal Genomics, IOB Quironsalud, and Oncolytics Biotech; has served on the executive board for Reveal Genomics and SOLTI Cooperative Group; has served on the patronage committee for the SOLTI Foundation and Actitud Frente al Cáncer Foundation; and their institution has patents for HER2DX (pending), ERBB2 (issued), WO2018/103834A1, and CES WO/2018/096191. The other authors have nothing to declare.

Author Contributions

A.R., U.d.G., O.N., M.P., F.S., and F.M. conceived the study. P.G. realized RNA extraction and transcriptomic analysis on the nCounter platform. TILs, TLS, and immune pattern were assessed by E.Sa., F.S., and M.P. performed the statistical analyses. F.S. carried out the bioinformatic analysis. F.S., M.P., F.B.M., A.P., and U.d.G. interpreted study results. F.S., U.d.G., and M.P. wrote the first manuscript draft. All authors except for F.S., F.B.M., P.G., E.Sa., and A.P. participated in patients’ recruitment and within-study management. All authors had access to study data and participated in revising and writing the final manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript version.

Data Availability

Anonymized clinicopathological data for this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Anonymized nCounter gene expression data are available as Supplementary Material.

Code Availability

No proprietary codes were used for the analyses of this study. R codes are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Consent for Publication

All patients gave their consent for publication of anonymized study results at the time of accepting participation in the KENDO trial.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and in full conformity with relevant regulations, ICH Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (CPMP/ICH/135/95) July 1996, the Directive 2001/20/EEC of the European Parliament and other relevant local legislation and applicable regulatory requirements. All patients had to sign an informed written consent before entering the study. The KENDO trial was approved by the Comitato Etico della Romagna-CEROM (Protocol Code: IRST174.19; IRST-Identifier Code: L2P1388).

Previous Presentation

The primary endpoint and the results contained in the “Immune biomarker analyses” section, have been presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium 2023 as poster presentation n. PO3-14-06 Immunologic features and association with prognosis in hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative (HR+/HER2−) metastatic breast cancer (MBC) treated with chemotherapy (CT) or CDK4/6-inhibitors (CDK4/6i) + endocrine therapy (ET). Schettini F., Palleschi M., Mannozzi F. et al. San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium December 5-9, 2023.

References

- 1. Schettini F, Giuliano M, Giudici F, et al. Endocrine-based treatments in clinically-relevant subgroups of hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(6):1458. 10.3390/cancers13061458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Giuliano M, Schettini F, Rognoni C, et al. Endocrine treatment versus chemotherapy in postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(10):1360-1369. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30420-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gao JJ, Cheng J, Bloomquist E, et al. CDK4/6 inhibitor treatment for patients with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced or metastatic breast cancer: a US Food and Drug Administration pooled analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(2):250-260. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30804-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schettini F, Giudici F, Giuliano M, et al. Overall survival of CDK4/6-inhibitors-based treatments in clinically relevant subgroups of metastatic breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(11):1089-1097. 10.1093/jnci/djaa071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gennari A, André F, Barrios CH, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee. ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for the diagnosis, staging and treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(12):1475-1495. 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Martin M, Zielinski C, Ruiz-Borrego M, et al. Palbociclib in combination with endocrine therapy versus capecitabine in hormonal receptor-positive, human epidermal growth factor 2-negative, aromatase inhibitor-resistant metastatic breast cancer: a phase III randomised controlled trial-PEARL. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(4):488-499. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Park YH, Kim T-Y, Kim GM, et al. ; Korean Cancer Study Group (KCSG). Palbociclib plus exemestane with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist versus capecitabine in premenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (KCSG-BR15-10): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(12):1750-1759. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30565-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 11). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-247. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wolff AC, Hammond MEH, Allison KH, et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(20):2105-2122. 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.8738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hammond MEH, Hayes DF, Dowsett M, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(16):2784-2795. 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.6529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dowsett M, Nielsen TO, A’Hern R, et al. ; International Ki-67 in Breast Cancer Working Group. Assessment of Ki67 in breast cancer: recommendations from the International Ki67 in Breast Cancer working group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(22):1656-1664. 10.1093/jnci/djr393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines for Breast Cancer, vers.4.2023. 2023. Accessed June 5, 2023.https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf

- 13. Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MCU, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1160-1167. 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schettini F, Chic N, Brasó-Maristany F, et al. Clinical, pathological, and PAM50 gene expression features of HER2-low breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2021;7(1):1. 10.1038/s41523-020-00208-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schettini F, Brasó-Maristany F, Kuderer NM, Prat A.. A perspective on the development and lack of interchangeability of the breast cancer intrinsic subtypes. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2022;8(1):85. 10.1038/s41523-022-00451-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salgado R, Denkert C, Demaria S, et al. ; International TILs Working Group 2014. The evaluation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer: recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(2):259-271. 10.1093/annonc/mdu450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu X, Tsang JYS, Hlaing T, et al. Distinct tertiary lymphoid structure associations and their prognostic relevance in HER2 positive and negative breast cancers. Oncologist. 2017;22(11):1316-1324. 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen DS, Mellman I.. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature. 2017;541(7637):321-330. 10.1038/nature21349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hothorn T, Zeileis A.. Generalized maximally selected statistics. Biometrics. 2008;64(4):1263-1269. 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.00995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lu Y-S, Bin Mohd Mahidin E, Azim H. et al. GS1-10 Primary results from the randomized Phase II RIGHT Choice trial of premenopausal patients with aggressive HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer treated with ribociclib + endocrine therapy vs physician’s choice combination chemotherapy. Oral Presentation at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium 2022.

- 22. Schettini F, Martínez-Sáez O, Falato C, et al. Prognostic value of intrinsic subtypes in hormone-receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. ESMO Open. 2023;8(3):101214. 10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.101214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Falato C, Schettini F, Pascual T, Brasó-Maristany F, Prat A.. Clinical implications of the intrinsic molecular subtypes in hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2023;112:102496. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2022.102496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ballot E, Galland L, Mananet H, et al. Molecular intrinsic subtypes, genomic, and immune landscapes of BRCA-proficient but HRD-high ER-positive/HER2-negative early breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res. 2022;24(1):80. 10.1186/s13058-022-01572-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bruno L, Ostinelli A, Waisberg F, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor outcomes in patients with advanced breast cancer carrying germline pathogenic variants in DNA repair-related genes. JCO Precis Oncol. 2022;6:e2100140. 10.1200/PO.21.00140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Militello AM, Zielli T, Boggiani D, et al. Mechanism of action and clinical efficacy of CDK4/6 inhibitors in BRCA-mutated, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers: case report and literature review. Front Oncol. 2019;9:759. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. André F, Ciruelos E, Rubovszky G, et al. ; SOLAR-1 Study Group. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(20):1929-1940. 10.1056/NEJMoa1813904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Litton JK, Hurvitz SA, Mina LA, et al. Talazoparib versus chemotherapy in patients with germline BRCA1/2-mutated HER2-negative advanced breast cancer: final overall survival results from the EMBRACA trial. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(11):1526-1535. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.2098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Robson M, Im S-A, Senkus E, et al. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(6):523-533. 10.1056/NEJMoa1706450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Doebele RC, Drilon A, Paz-Ares L, et al. ; trial investigators. Entrectinib in patients with advanced or metastatic NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours: integrated analysis of three phase 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(2):271-282. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30691-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Drilon A, Laetsch TW, Kummar S, et al. Efficacy of larotrectinib in TRK fusion-positive cancers in adults and children. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):731-739. 10.1056/NEJMoa1714448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Subbiah V, Wolf J, Konda B, et al. Tumour-agnostic efficacy and safety of selpercatinib in patients with RET fusion-positive solid tumours other than lung or thyroid tumours (LIBRETTO-001): a phase 1/2, open-label, basket trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(10):1261-1273. 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00541-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prat A, Brasó-Maristany F, Martínez-Sáez O, et al. Circulating tumor DNA reveals complex biological features with clinical relevance in metastatic breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Altevogt P, Sammar M, Hüser L, Kristiansen G.. Novel insights into the function of CD24: a driving force in cancer. Int J Cancer. 2021;148(3):546-559. 10.1002/ijc.33249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Panagiotou E, Syrigos NK, Charpidou A, Kotteas E, Vathiotis IA.. CD24: A novel target for cancer immunotherapy. J Pers Med. 2022;12(8):1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jing X, Cui X, Liang H, et al. CD24 is a potential biomarker for prognosis in human breast carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;48(1):111-119. 10.1159/000491667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schettini F, Barbao P, Brasó-Maristany F, et al. Identification of cell surface targets for CAR-T cell therapies and antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer. ESMO Open. 2021;6(3):100102. 10.1016/j.esmoop.2021.100102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Garcia-Corbacho J, Indacochea A, González Navarro A, et al. Determinants of activity and efficacy of anti-PD1/PD-L1 therapy in patients with advanced solid tumors recruited in a clinical trials unit: a longitudinal prospective biomarker-based study. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023;72:1709–1723. 10.1007/s00262-022-03360-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schepisi G, Gianni C, Palleschi M, et al. The new frontier of immunotherapy: chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell and macrophage (CAR-M) therapy against breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15(5):1597. 10.3390/cancers15051597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Loi S, Drubay D, Adams S, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis: a pooled individual patient analysis of early-stage triple-negative breast cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(7):559-569. 10.1200/JCO.18.01010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang B, Liu J, Han Y, et al. The presence of tertiary lymphoid structures provides new insight into the clinicopathological features and prognosis of patients with breast cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:868155. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.868155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zhang N-N, Qu F-J, Liu H, et al. Prognostic impact of tertiary lymphoid structures in breast cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):536. 10.1186/s12935-021-02242-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vaghjiani RG, Skitzki JJ.. Tertiary lymphoid structures as mediators of immunotherapy response. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(15):3748. 10.3390/cancers14153748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Munoz-Erazo L, Rhodes JL, Marion VC, Kemp RA.. Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer – considerations for patient prognosis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17(6):570-575. 10.1038/s41423-020-0457-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Martinet L, Le Guellec S, Filleron T, et al. High endothelial venules (HEVs) in human melanoma lesions: major gateways for tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1(6):829-839. 10.4161/onci.20492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Goel S, DeCristo MJ, Watt AC, et al. CDK4/6 inhibition triggers anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2017;548(7668):471-475. 10.1038/nature23465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized clinicopathological data for this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Anonymized nCounter gene expression data are available as Supplementary Material.