Abstract

This Viewpoint outlines our recent contribution in electroreductive synthesis. Specifically, we leveraged deeply reducing potentials provided by electrochemistry to generate radical and anionic intermediates from readily available alkyl halides and chlorosilanes. Harnessing the distinct reactivities of radicals and anions, we have achieved several challenging transformations to construct C–C, C–Si, and Si–Si bonds. We highlight the mechanistic design principle that underpinned the development of each transformation and provide a view forward on future opportunities in growing area of reductive electrosynthesis.

Keywords: electrosynthesis, electroreduction, alkyl halide, chlorosilane, radical-polar crossover, alkene difunctionalization, cross-electrophile coupling

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

The development of general and selective methods to generate and transform reactive intermediates such as radicals, cations, and anions remains an important objective in modern organic chemistry.1 In the realm of two-electron chemistry, reactive ionic intermediates have been traditionally accessed using organometallic reagents or strong Lewis/Brönsted acids, which are often highly reactive but can be limited by functional group tolerance and selectivity. Complimentary to two-electron chemistry, the unique electronic configuration and distinct reactivity of radicals enable their use for challenging transformations. Early work on radical intermediates employed potentially hazardous initiators, such as tin reagents and peroxides, hampering the broad adoption of radical reactions in organic synthesis.2 To address the challenges associated with highly reactive intermediates and further advance their chemistry, transition metal catalysis,3 organocatalysis,4 photoredox chemistry,5 and biocatalysis6 have emerged as increasingly powerful tools in organic synthesis. Nevertheless, the continued development of complementary approaches that can provide controlled access to both one- and two-electron paradigms remains highly desirable.

Electrochemistry can promote the formation of both radical and ionic intermediates by applying sufficient activating potentials to common organic functional groups.7 In contrast to canonical chemical redox reactions, electrochemistry provides access to a wide potential window, which is limited only by stability of the solvent and electrolyte. Importantly, modulation of the electric potential and current allows for precise control over the identity and concentration of the reactive intermediates generated at the electrodes. These attributes make electrochemistry an efficient method for accessing and controlling the reactivity of both radical and ionic intermediates. Indeed, pioneering studies over the last several decades have demonstrated the versatility of this approach in guiding unstable intermediates through reaction pathways with high chemofidelity. 8 Not surprisingly, in the past several years synthetic electrochemistry has rapidly expanded into a major subfield of modern organic chemistry and been adopted by many sectors of academic and industrial research. However, while there is a large and increasing body of literature on oxidative electrosynthesis, reductive electrochemical reactions are substantially less reported.9 We attribute this striking difference to the intrinsic challenges associated with reductive electrosynthesis. In general, electroreductive reactions require the use of sacrificial anodes or reductants, which may cause electrode fouling or interfere with desired cathodic reactions. Moreover, the low overpotentials for hydrogen and oxygen reduction often require such reactions to be run under strictly anhydrous and anaerobic conditions. Nevertheless, the prospect of gaining convenient and controlled access to reactive intermediates at deep reductive potentials has driven a renewed interest in expanding the scope of reductive electrosynthesis in recent years.

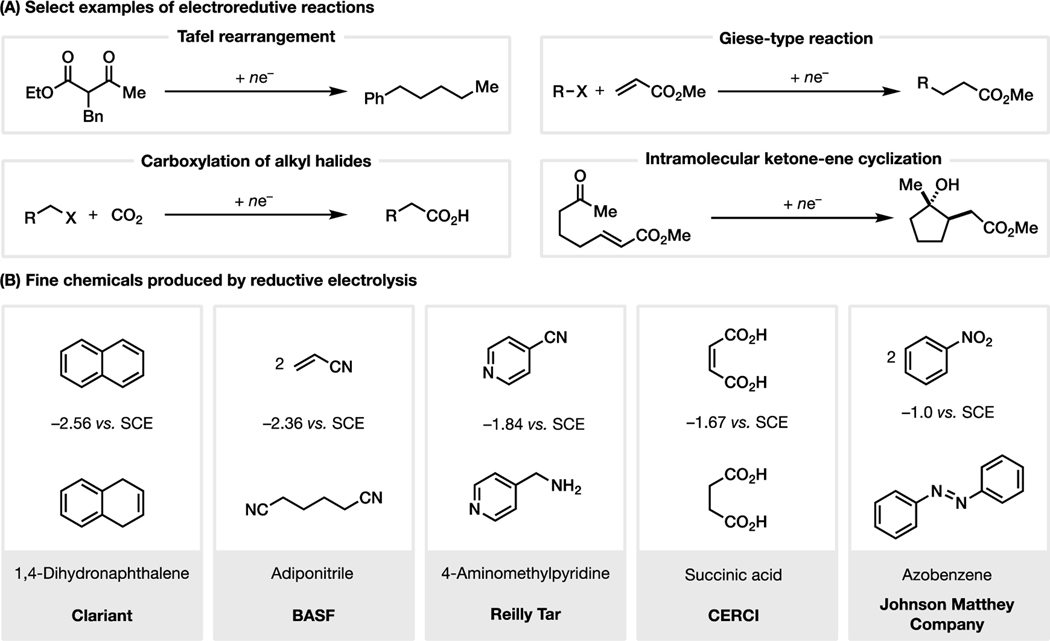

The earliest example of an electroreductive reaction was the dehalogenation of trichloromethanesulfonic acid developed by Schoebein,10 reported shortly before the venerable Kolbe electrolysis.11 Since then, other noteworthy reductive electrochemical reactions, such as the Tafel rearrangement,12 the reductive coupling of ketones,13 and the carboxylation of organohalides14 have been developed. Today, several commodity chemicals are produced via electroreductive syntheses, including 1,4-dihydronaphthalene, adiponitrile, 4-aminomethylpyridine, succinic acid, and azobenzene (Figure 1).15 Interestingly, these industrial reactions are operated at potentials ranging from −1.0 to −2.6 V, highlighting the wide potential window available to synthetic chemists.

Figure 1.

Electroreductive synthesis: (A) Select early examples of electroreductive reactions. (B) Select fine chemicals produced by reductive electrolysis in industry.

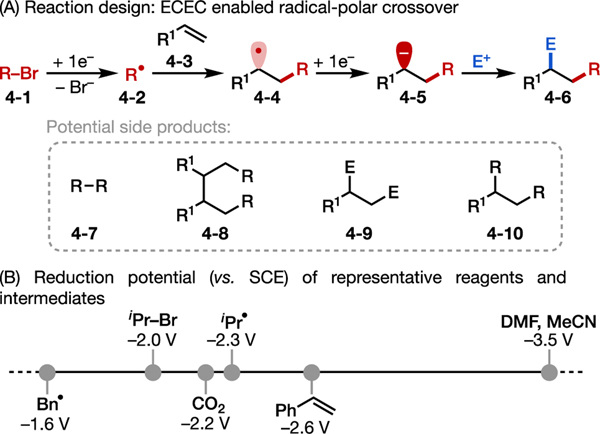

Inspired by these precedents, our laboratory is particularly interested in leveraging radicals and anions generated from common electrophilic functional groups in organic electrosynthesis. In this Viewpoint, we highlight our recent campaign in this field (Figure 2). First, we discuss our strategy for the selective electrochemical reduction of alkyl halides and its utility towards alkene carbofunctionalization and cross-electrophile coupling reactions. We then summarize our contribution to the synthesis of organosilicon compounds via electrochemical reduction of chlorosilanes. We conclude with a view forward and discuss future opportunities in reductive electrosynthesis.

Figure 2.

Electroreductive chemistry of alkyl halides and chlorosilanes contributed by our group.

2. ELECTROCHEMICAL REDUCTION OF ALKYL HALIDES

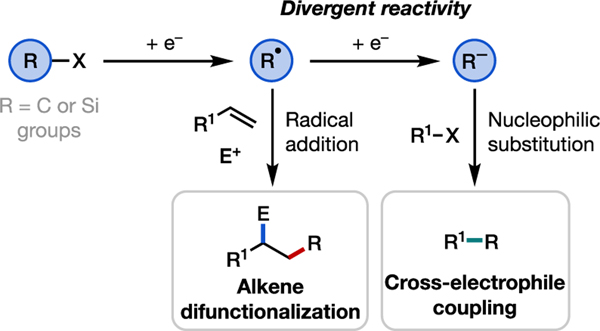

Alkyl halides are among the most prevalent functional groups in organic molecules.16 In addition to being excellent electrophiles, alkyl halides are also used as precursors for alkyl radicals (Figure 3). Unactivated alkyl halides often exhibit significantly negative single-electron reduction potentials that are challenging to access in a selective manner using traditional chemical reagents. To circumvent this issue, tin, silicon, or boron-based initiators have been used to transform alkyl halides into alkyl radicals, often via a halogen atom transfer mechanism (XAT).17 Likewise, transition metals such as Ni have also been shown to undergo oxidative addition to alkyl halides.18 Recently, these activation approaches have been integrated with photoredox catalysis to further diversify the radical transformations of alkyl halides.19

Figure 3.

Strategies and select reagents used to generate alkyl radicals from alkyl halides.

Advantageously, the highly biased potentials accessible with electrochemistry offer an efficient means to directly reduce alkyl halides to alkyl radicals without the use of additional activating agents.20 Furthermore, depending on the substrate structure and applied potential, electrochemistry can also turn on two-electron reduction pathways, thus granting access to alkyl anions and the reactions associated with these intermediates. The electroreductive activation of alkyl halides has been extensively studied using cyclic voltammetry,21 which laid the foundation for a number of pioneering contributions by Perichon and others20 to the development of Giese,22 carboxylation,23 and alkylation reactions.24 Nevertheless, the types of transformations enabled by this strategy remain limited, and the exploration of these methods in complex environments relevant to medicinal and materials applications is rare.

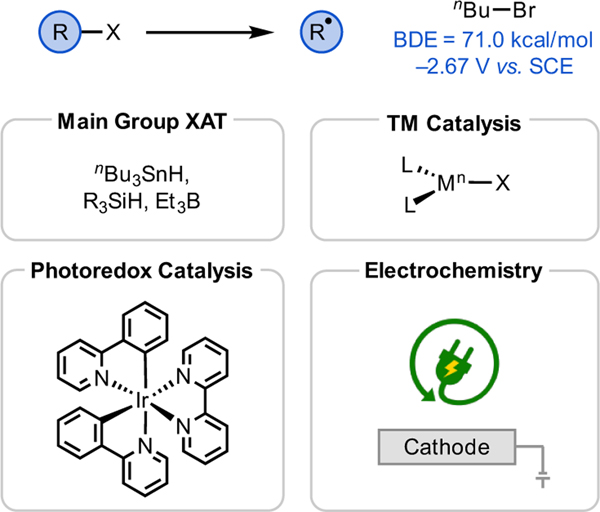

2.1. Reductive Carbofunctionalization of Alkenes

Our initial research focused on the electroreductive carbofunctionalization of alkenes with alkyl bromides. Electrochemistry has been explored as an efficient approach for the difunctionalization of alkenes,25 but prior work has primarily interrogated oxidative transformations by activating nucleophile reagents.25,26 We envisioned a radical-polar crossover mechanism for the desired carbofunctionalization by means of an electrochemical-chemical-electrochemical-chemical (ECEC) process (Figure 4A).27 Specifically, selective cathodic reduction of an alkyl bromide would form an alkyl radical capable of adding into an alkene to deliver a new carbon-centered radical (4–4). This radical would be further reduced at the cathode to generate a carbanion (4–5), which could then be intercepted by a second electrophile (E+) to afford the product 4–6. To achieve this reaction in high regio- and chemo-selectivity, possible side products (4–7 to 4–10) derived from the radical and anion intermediates must be inhibited. Thus, the choice of E+ is key so that the alkyl bromide is selectively reduced (instead of E+) and so that resultant carbanion (4–5) selectively reacts with E+ (instead of the alkyl bromide). In addition, the alkene substrate should stabilize both radical and anionic intermediates to facilitate the initial radical addition and subsequent reduction over radical dimerization. With these criteria in mind, knowledge of the reduction potentials of various electrophiles and radicals is critical to reagent selection (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Electroreductive carbofunctionalization of alkenes with alkyl bromides.27 (A) Reaction design princeple. (B) Reduction potentials of some relevant reagents and intermediates.

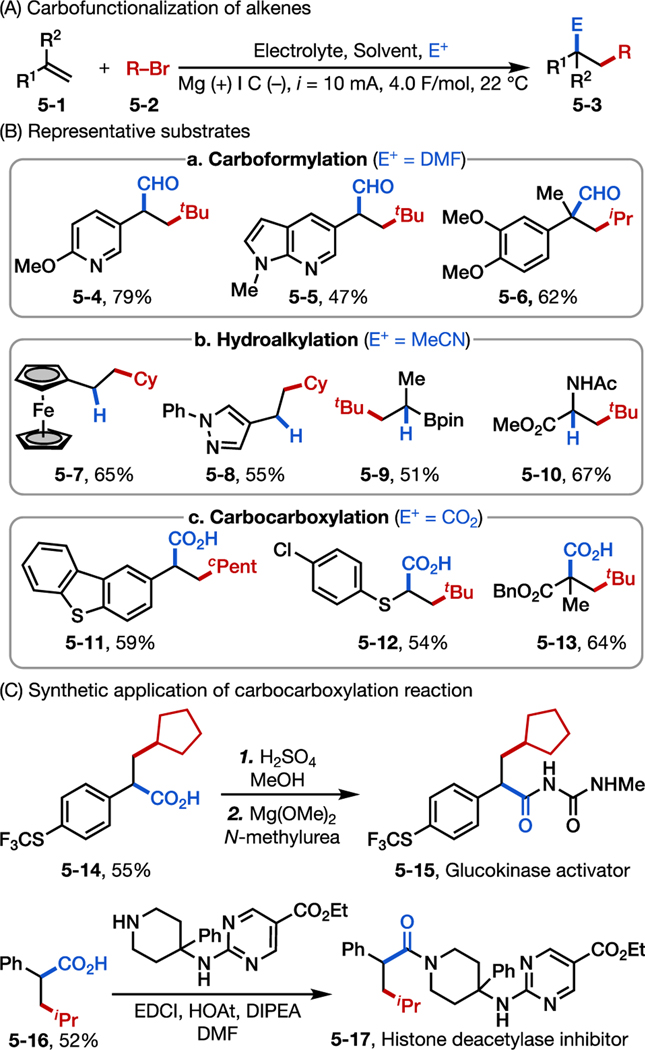

Following these criteria, we developed various reductive carbofunctionaliztion reactions of terminal alkenes (Figure 5A).27 These reactions typically employ graphite as the working electrode and a sacrificial magnesium anode that releases Mg2+ into the solution during electrolysis (Figure 5A). For example, using N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) as both the solvent and a formyl group donor allowed us to realize the intermolecular carboformylation of alkenes (Figure 5B, box a). This reaction is compatible with various electronically disparate conjugated alkenes, including styrenes and vinyl-N-heteroarenes. Acyclic and cyclic secondary and tertiary alkyl bromides were tolerated. Using a solvent with acidic protons, such as acetonitrile (MeCN), further allowed us to access anti-Markovnikov hydroalkylated products (Figure 5B, box b). Although several transition-metal based catalysts are available for similar transformations,28 this electrochemical reaction provides a complementary approach to hydroalkylation of alkenes via a distinct mechanism. Owing to the radical or anion stabilization effect, non-styrenyl alkenes such as vinyl pinacol boronic esters and 2-acetamidoacrylate could also be used (products 5–9 and 5–10, respectively).

Figure 5.

Electroreductive carbofunctionalization of alkenes: reaction development. (A) Optimal reaction condition. (B) Representative reaction scope. (C) Synthesis of precursor of bioactive molecules.

Finally, motivated by prior work demonstrating that CO2 can be used in electrochemical carboxylation,14, 23, 29 in particular the dicarboxylation30 and hydrocarboxylation31 of alkenes, we extended this approach to the carbocarboxylation of alkenes using CO2 as the second electrophile (Figure 5B, box c)27. Of note, the resultant α-arylacetic acid products (5–11, 5–14, 5–15) are prevalent scaffolds in bioactive molecules.32 The diversity and availability of alkenes and alkyl bromides further allowed us to synthesize a series of analogs to bioactive molecules and their precursors in a modular and expedient manner33 (Figure 5C), highlighting the benefit of this electrochemical method.

2.2. Cross-Electrophile Coupling for C(sp3)–C(sp3) Bond Formation

In recent years, cross-electrophile coupling (XEC) has become a versatile and efficient approach for the construction of C–C bonds from readily available electrophiles, such as organohalides34 Despite advances in Ni-catalyzed XEC reactions for C(sp2)–C(sp2)35 and C(sp2)–C(sp3) bond formation36, selective XEC of two alkyl halides to construct C(sp3)–C(sp3) bonds remains challenging.37 Current methods relying on transition metal catalysis are frequently plagued by undesired competitive homocoupling37a, b, c in addition to other side reactions associated with metal–alkyl intermediates.

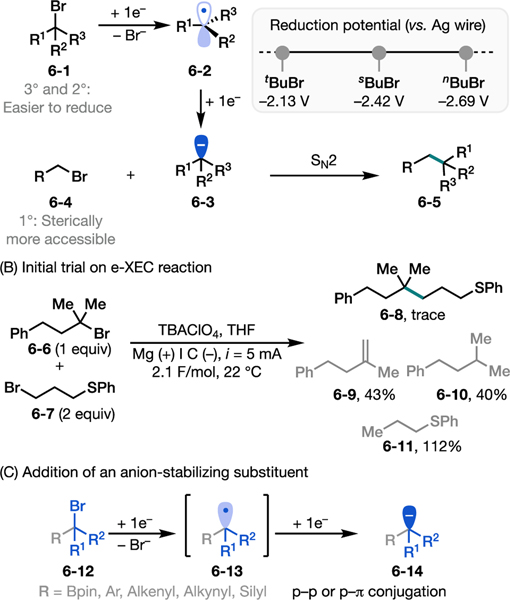

Taking advantage of the marked differences in the electronic and steric properties of alkyl halides with disparate (i.e., primary, secondary, or tertiary) substitution patterns, we envisioned an electrochemically driven XEC (e-XEC) as a new and complementary approach to achieve selective substrate activation toward the desired cross coupling.38 Specifically, a more substituted alkyl bromide (secondary or tertiary; 6–1) could undergo two successive one-electron reductions at the cathode preferentially in the presence of a more reductively inert primary alkyl halide (6–4), generating a carbanion intermediate (6–3) after loss of Br−. This intermediate would then preferentially react with a sterically more accessible primary alkyl bromide (6–4) in an SN2 pathway to furnish the XEC product (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Electrochemically driven XEC reaction.38 (A) Reaction design principle. (B) Initial trial with unactivated alkyl bromides: alkyl radical reduction is in competition with radical side reactions. (C) The use of anion stabilizing substituents promotes the desired reactivity.

Cognizant of the difficulty of reducing simple alkyl radicals to carbanions (Figure 6B), we strategically employed tertiary alkyl halides with an anion-stabilizing substituent at the α position to ensure the success of this reaction design (Figure 6C). Density functional theory (DFT) calculations and cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements suggested that groups such as boryl, aryl, and alkenyl facilitate the overall two-electron reduction by means of conjugative or hyperconjugative stabilization of the resultant carbanions. Importantly, these substituents, such as Bpin, could be further elaborated into other useful functional groups.39

Mechanistically, our design principle is fundamentally different from previously reported Ni-XEC reactions,37a, b, c allowing us to bypass the traditional limitations associated with Ni catalysis. Indeed, when we monitored the reaction of a tertiary α-bromoboronate ester (7–1) with a primary alkyl bromide (7–2) (Figure 7A), the e-XEC reaction showed excellent chemoselectivity, with no evidence of homocoupling (a typical side reaction in Ni catalyzed systems) and only traces (≤5%) of hydrodehalogenation and elimination products. Notably, decreasing the amount of primary alkyl bromide to 1.05 equivalents, the reaction still proceeded in good yield (68%) with excellent chemoselectivity.

Figure 7.

Electrochemical XEC of alkyl halides: reaction development. (A) Optimal reaction conditions. (B) Representative reaction scope. (C) Formal benzylic C-H bond methylation

Following optimization of the reaction conditions, we extended the scope of the transformation to a broad range of alkyl halides (Figure 7B). Functional groups such as alkyl chloride, carbamate, ester, nitrile, and heteroarenes are preserved under these highly reducing reaction conditions. In tandem with initial photochemical benzylic C–H chlorination,40 we further applied our e-XEC methodology to achieve the formal benzylic C–H methylation of 7–14 in good yield (Figure 7C).

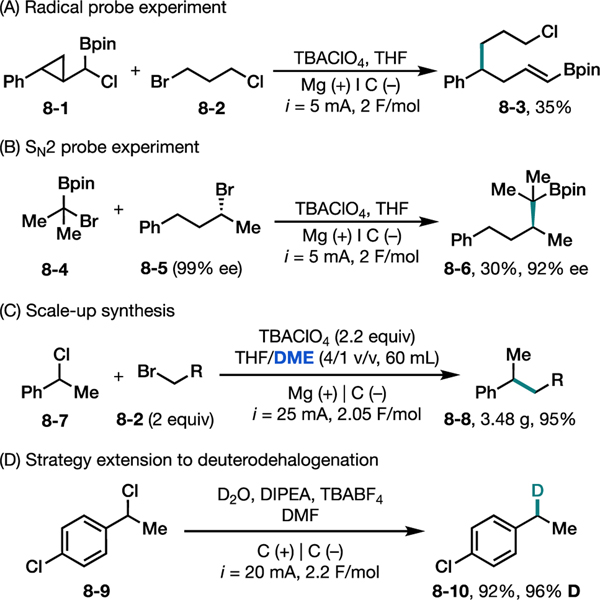

Control experiments with radical and anion probes supported our proposed mechanism for the e-XEC reaction (Figures 8A–8B). For instance, when the radical probe substrate 8–1 with a cyclopropyl ring was employed, the ring opening product 8–3 was observed, supporting the presence of a radical intermediate under the reaction conditions. Furthermore, subjecting chiral alkyl bromide 8–5 to the reaction conditions led to enantioenriched product 8–6, suggesting C–C bond formation via a concerted SN2 mechanism operating through a carbanion intermediate. Finally, we successfully carried out the e-XEC reaction on a 20-mmol scale using a modified procedure with dimethoxyethane (DME) as a co-solvent, producing nearly 4 g of 8–8 in excellent yield (Figure 8C).

Figure 8.

(A) and (B) Control experiments to probe the mechanism of electrochemical XEC of alkyl halides, (C) synthesis scale-up, and (D) development of deuterohalogenation.

The same reaction strategy has recently been applied to the development of a deuterodehalogenation reaction of benzylic halides (Figure 8D).41 Through systematic optimization of homogenous reductants, it was found that diisopropylethyl amine (DIPEA) could undergo anodic oxidation on a carbon electrode to counterbalance the desired cathodic reduction of alkyl halides, thus avoiding the use of a sacrificial metal anode. Under this parallel paired electrolysis system, a variety of simple and complex benzylic bromides and chlorides were efficiently deuterated using D2O as the deuterium source.

3. ELECTROCHEMICAL REDUCTION OF CHLOROSILANES

Having achieved electroreductive transformations of alkyl halides, we were interested in extending this mechanistic platform to the reductive activation of chlorosilanes to construct Si–R (R = C, Si) bonds. Silicon-containing compounds have attracted great interest in organic chemistry, medicinal chemistry, and materials science.42 For example, organosilanes are more stable alternatives to organoboranes in cross-coupling reactions (i.e., Hiyama coupling).43 In addition, the strategic incorporation of silicon bioisosteres into bioactive compounds has become a common strategy to optimize the lipophilicity, biological activity, and overall therapeutic potential of drug molecules.44 Oligosilanes are also key intermediates in the preparation of industrially valuable materials such as silicon carbide.45 As such, practical methods to synthesize Si–C or Si–Si bonds from abundant feedstocks are highly desirable.

Chlorosilanes are among the most available silyl reagents in organic synthesis and are traditionally used as electrophiles to construct Si–O, Si–Si, or Si–C bonds.46 In comparison, the reductive activation of chlorosilanes to generate silyl radicals and silyl anions remains challenging due to the strength of the Si–Cl bond (BDE = 110 kcal/mol) and its low single-electron reduction potential (–3.1 V vs SCE).47 We envisioned that reduction of chlorosilane could be achieved using electrochemistry and the resultant radical intermediate could then be interfaced in a radical-polar crossover mechanism to achieve either alkene difunctionalization or cross-electrophile coupling, in a manner akin to the alkyl halide reactivity described in Section 2 (see Figure 2). In particular, depending on the structure of the chlorosilane and the reaction conditions, one could selectively access either one-electron or two-electron reduction pathways to yield either silyl radicals or anions. In the following sections, we highlight our contributions in developing a general and mild approach for the synthesis of organosilanes and oligosilanes via the electrochemical reduction of chlorosilanes.

3.1. Reductive Disilylation of Alkenes

Silyl radicals are typically strongly nucleophilic and can react with various π-electrophiles such as alkenes, providing an expedient approach to generating Si–C bonds.48 Typically, silyl radicals have been generated by hydrogen atom abstraction from hydrosilanes via chemical49or photochemical47, 50 initiation, but these methods are often limited by the availability of hydrosilanes.51 Activation of Si–X (X = Si,52 B,53 or P54, etc.55) bonds has emerged as an alternative approach to access silyl radicals, though these precursors are often synthesized from chlorosilanes. The electroreductive generation of silyl radicals directly from readily available chlorosilanes is an attractive alternative to these methods, but there are few examples in organic synthesis. In an early report, Hengge56 and Shono57 demonstrated the overall two-electron reduction of chlorosilanes to generate silyl anions via silyl radicals, but the interception of intermediate silyl radicals for C-Si bond formation remained underexplored.58

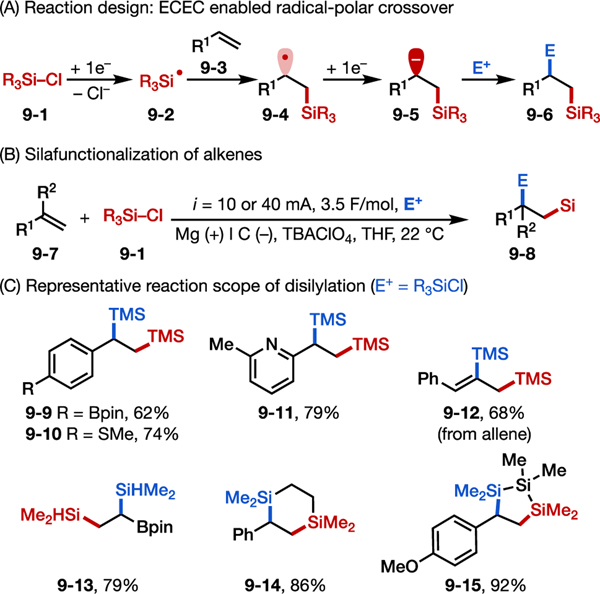

In our design, reduction of chlorosilanes would enable an ECEC mechanism similar to the one encountered with alkyl halides (Figure 9A).59 Specifically, chlorosilane reduction would generate a silyl radical (9–2) capable of rapidly adding across an alkene to furnish a new carbon-centered radical (9–4). Reduction of this new radical species to form anion 9–5 followed by termination with a suitable electrophile (E+) would then generate the desired product.

Figure 9.

Electroreductive disilylation of alkenes.58 (A) Reaction design principle. (B) Optimal reaction conditions. (C) Representative reaction scope.

We first developed the electroreductive disilylation of styrenes using two equivalents of trimethylsilyl chloride (TMSCl) as both silyl radical precursor and anion-terminating electrophile (Figures 9B–9C). A wide range of electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups were found to be tolerated on the alkene (e.g., 9–9 and 9–10), and heterocycles such as vinylpyridine were also suitable substrates (9–11). Allenes were smoothly converted to disilanes (e.g., 9–12). In addition to styrenes, vinyl boronates also proved to be excellent radical acceptors, undergoing disilylation to yield gem-(B, Si) substitution (9–13). By using dichlorodisilanes as reagents, we could access silacycles (e.g., 9–14 and 9–15), which are often challenging to synthesize.60

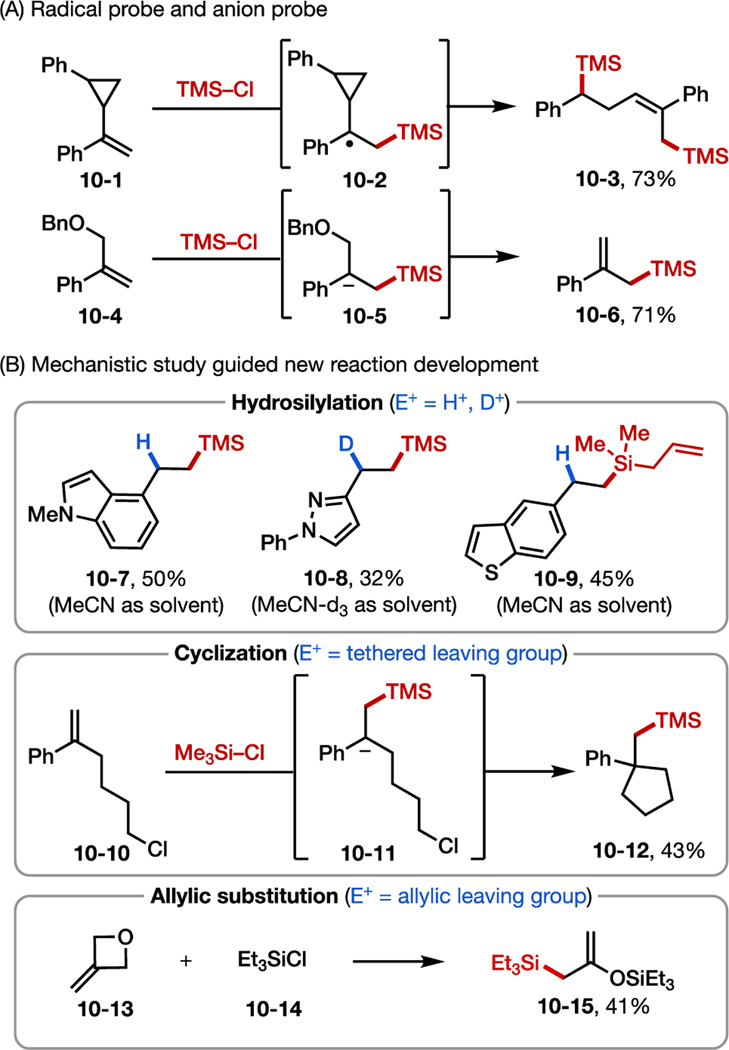

Cyclic voltammetry studies revealed that reduction of TMSCl occurs at a higher potential than styrene and should be favored under the experimental conditions. Further, the use of radical probe 10–1 or anion probe 10–4 as substrates resulted in ring opening of the cyclopropane (10–3) and formation of an allylic silane (10–6), respectively, suggesting the formation of both radical and anionic intermediates along the reaction path (Figure 10A). Multivariate linear regression analysis revealed that the reaction rate is dependent on both the electronic properties of the alkene and the stability of the benzylic radical. Altogether, these observations support that dual C–Si bond formation occurs via the proposed radical-polar crossover mechanism (Figure 9A).

Figure 10.

(A) Radical and anion probe substrates used to investigate the mechanism of reductive alkene disilylation. (B) Extension of this reactivity to other substrates.

We envisioned that in the presence of a judiciously selected second electrophile (E+) other than TMSCl, other silylation reactions may be achieved (Figure 10B). Specifically, if the chosen electrophile is more challenging to reduce than chlorosilane but is highly reactive towards quenching the carbanion (9–5 in Figure 9) generated upon radical-polar crossover, a diverse range of cross-selective alkene difunctionalizations could be possible. For example, when MeCN (or MeCN-d3) was used as solvent instead of THF, hydro- and deuteron-silylation products (e.g., 10–7 to 10–9) could be obtained by capturing the resultant benzylic anion with a proton (or a deuterium).61 Additionally, when a leaving group was attached either adjacent or distal to the site of the benzylic anion, intramolecular elimination or substitution took place to deliver silyl-substituted cyclic alkanes (e.g., 10–12) or allylsilanes (e.g., 10–15).

Cross-Electrophile Coupling for Si(sp3)–Si(sp3) Bond Formation

Disilanes and oligosilanes have received increasing interest in organic synthesis and materials science.62For example, disilanes are useful reagents to construct C–Si bonds.63 Materials containing oligosilanes exhibit unique electronic and luminescent characteristics as a result of σ-bond electron delocalization along the Si–Si chains.64 Even still, methods to construct Si–Si bonds are underdeveloped. Classic Wurtz coupling of halosilanes using alkali metals (i.e., Na or Li) remains the most practiced method to form Si–Si bonds, but the functional group tolerance and reaction selectivity are limited under the harsh conditions employed.65 Dehydrogenative coupling of silanes has emerged as an attractive alternative, although current methods are limited to homodimerization and polymerization.66 Silylboranates have also been used for Si–Si bond formation, yet methods for preparing of these reagents remain limited.67

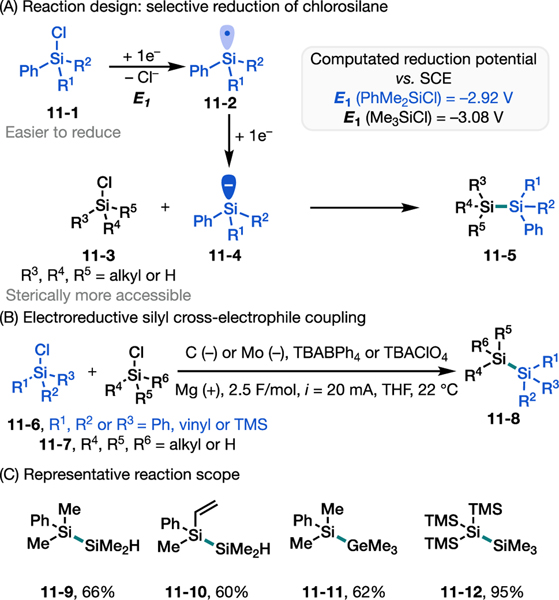

We were interested in applying the principles of e-XEC to achieve Si–Si cross-electrophile coupling, starting from chlorosilanes with distinct redox potentials and steric properties (Figure 11A).68 For example, a chlorosilane with an aromatic stabilizing group (11–1) would preferentially undergo an overall two-electron reduction to form a silyl anion (11–4) in the presence of a di- or tri-alkylchlorosilane (11–3); the ensuing silyl anion would then selectively attack the sterically less encumbered di- or tri-alkylchlorosilane to complete the Si–Si bond formation (11–5). It should be noted that the electrochemical activation of chlorosilanes was previously explored in a few pioneering studies,55, 56 but the reaction scope and its synthetic applications were not established, particularly in the context of cross coupling and oligosilane synthesis.

Figure 11.

Electroreductive silyl cross-electrophile coupling.68 (A) Reaction design of electroreductive disilylation of alkenes and DFT calculations support for the proposed mechanism. (B) Optimal reaction conditions. (C) Representative reaction scope.

We developed optimal reaction conditions (Figure 11B) for several silyl cross-coupling reactions between a variety of chlorosilanes (Figure 11C). We found that the combination of a molybdenum cathode and tetrabutylammonium tetraphenylborate or perchlorate (TBABPh4 or TBAClO4) as electrolyte affords desired products in high yield with excellent selectivities, under otherwise similar conditions to those used for the disilylation of alkenes. For example, using a nearly 1:1 ratio of the precursor chlorosilanes, the formation of heterocoupling products over the homocoupling products was favored with >20:1 selectivity (e.g., 11–9 and 11–10). The reaction scope was further expanded to Si–Ge bond formation using Me3Ge–Cl (11–11). Notably, supersilyl chloride (TMS3SiCl) could also be preferentially reduced and coupled with TMSCl to afford TMS4Si (11–12) in nearly quantitative yield.

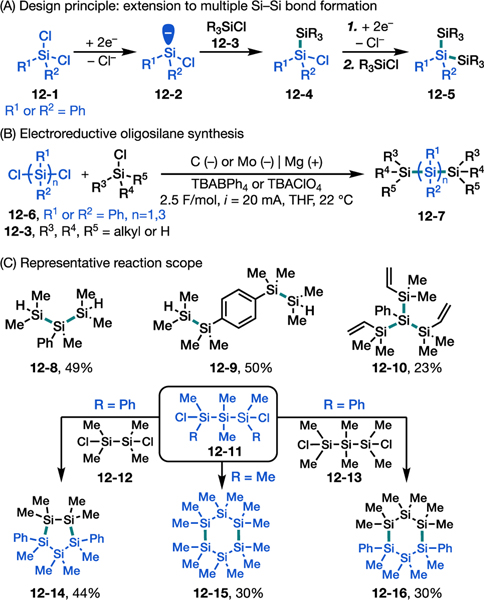

We next sought to extend this approach to the synthesis of more challenging compounds including acyclic and cyclic oligosilanes. In particular, to generate and control the reactivity of multivalent silyl anion intermediates (e.g., dianions) from polychlorosilanes (e.g., 12–1) is difficult using the canonical Wurtz method.69 We envisioned that electrochemistry could provide a complementary synthetic logic to oligosilane synthesis by bypassing this restriction (Figure 12). For example, dichlorosilanes such as 12–1 could serve as a silyl dianion equivalent via sequential reduction (12–2) and reaction with monochlorosilanes (12–3) to form one Si–Si bond (12–4). This reductive coupling step could be repeated for 12–4 to form a second Si–Si bond (12–5). Following reaction optimization (Figure 12B), this concept was successfully demonstrated in the synthesis of various oligosilanes via multiple consecutive Si–Si bond-forming events (e.g., 12–8 to 12–10) from corresponding di- and tri-chlorosilanes (Figure 12C). Furthermore, the concept was adapted for the synthesis of cyclic oligosilanes such as cyclopentasilane 12–14 and cyclohexasilane 12–15 and 12–16. These compounds are either synthesized using excess Li metal (12–15)70 or, to our knowledge, have not been previously isolated (12–14 and 12–16),71 highlighting the usefulness of electroreductive chemistry in organosilane synthesis.

Figure 12.

Extension of electroreductive silyl cross-electrophile coupling to oligosilanes and cyclic silanes. (A) Reaction design principle. (B) Optimal reaction conditions. (C) Representative reaction scope.

SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK

In recent years, reductive electrochemistry has drawn substantial interest as a valuable tool in organic synthesis. Our contributions in this area have focused on leveraging deeply reducing potentials to access radical and anionic intermediates that can engage in the formation of C–C, C–Si, and Si–Si bonds. To this end, electrochemically enabled radical-polar crossover has proven to be a general and effective strategy for the successful development of various alkene difunctionalization and cross coupling reactions. Despite these early successes, several outstanding questions remain. For example, further mechanistic studies are needed to elucidate the factors that govern one- and two-electron reduction of alkyl halides and chlorosilanes. Additionally, expansion of electroreductive chemistry to include electrophiles such as ketones,72 epoxides,73 imines,74 and heterocyclic arenes75 is desirable. Further, the development of enantioselective variants76 remains an attractive yet challenging objective. Finally, interfacing electroreductive chemistry with transition metal catalysis77 and electrode modification78 are also promising directions for exploration. We anticipate that the recent renewed interest in reductive electrosynthesis in the organic chemistry community will continue to improve our ability to synthesize complex molecules and enrich our understanding of the activities of reactive intermediates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Financial support was provided by NIGMS (R01GM130928). We thank Katie Meihaus, Andrew J. Ressler, Samson Zacate, and Minsoo Ju for manuscript editing. We dedicate this paper to Prof. Guosheng Liu at SIOC on the occasion of his 50th birthday.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Moss RA; Platz MS; Jones M Jr. Reactive Intermediate Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- (2) (a).Jasperse CP; Curran DP; Fevig TL Radical reactions in natural product synthesis. Chem. Rev 1991, 91, 1237–1286. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yan M; Lo JCJ; Edwards T; Baran PS Radicals: Reactive Intermediates with Translational Potential. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 12692–12714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hartwig J. Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis. University Science Books, New York, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- (4) (a).List B. Introduction: Organocatalysis. Chem. Rev 2007, 107, 5413–5415. [Google Scholar]; (b) MacMillan DWC The advent and development of organocatalysis. Nature 2008, 455, 304–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5) (a).Prier CK; Rankic DA; MacMillan DWC Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis with Transition Metal Complexes: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 5322–5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Narayanam JMR; Stephenson CRJ Visible Light Photoredox Catalysis: Applications in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 102–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6)(a).Hanefeld U; Hollmann F; Paul CE Biocatalysis making waves in organic chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev 2022, 51, 594–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Miller DC; Athavale SV; Arnold FH Combining Chemistry and Protein Engineering for New-to-Nature Biocatalysis. Nat. Synth 2022, 1, 18–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Schäfer HJ Anodic and Cathodic CC-Bond Formation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1981, 20, 911–934. [Google Scholar]

- (8) (a).Moeller KD Synthetic Applications of Anodic Electrochemistry. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 9527–9554. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sperry JB; Wright DL The application of cathodic reductions and anodic oxidations in the synthesis of complex molecules. Chem. Soc. Rev 2006, 35, 605–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Francke R; Little RD Redox Catalysis in Organic Electrosynthesis: Basic Principles and Recent Developments. Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 2492–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yan M; Kawamata Y; Baran PS Synthetic Organic Electrochemical Methods Since 2000: On the Verge of a Renaissance. Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 13230–13319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Yoshida J-I; Shimizu A; Hayashi R. Electrogenerated Cationic Reactive Intermediates: The Pool Method and Further Advances. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 4702–4730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wiebe A; Gieshoff T; Möhle S; Rodrigo E; Zirbes M; Waldvogel SR Electrifying Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 5594–5619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Novaes LFT; Liu J; Shen Y; Lu L; Meinhardt JM; Lin S. Electrocatalysis as an Enabling Technology for Organic Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev 2021, 50, 7941–8002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9)(a).Park SH; Ju M; Ressler AJ; Shim J; Kim H; Lin S. Reductive Electrosynthesis: A New Dawn. Aldrichimica Acta 2021, 54, 17–27. [Google Scholar]; (b) Claraz A; Masson G. Recent Advances in C(sp3)–C(sp3) and C(sp3)–C(sp2) Bond Formation through Cathodic Reactions: Reductive and Convergent Paired Electrolyses. ACS Org. Inorg. Au 2022, 2, 126–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Huang B; Sun Z; Sun G. Recent progress in cathodic reduction-enabled organic electrosynthesis: Trends, challenges, and opportunities. eScience 2022, 2, 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Kolbe H. Beiträge zur Kenntniss der gepaarten Verbindungen. Ann. Chem. Pharm 1845, 54, 145–188. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kolbe H. Observations on the Oxidizing Effect of Oxygen When it is Developed by Means of an Electric Column.J. Prakt. Chem 1847, 41, 137–139. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Tafel J; Hahl H. Vollständige Reduktion Des Benzylacetessigesters. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges 1907, 40, 3312–3318. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Little RD; Fox DP; Van Hijfte L. Electroreductive Cyclization. Ketones and Aldehydes Tethered to α, β-Unsaturated Esters (Nitriles). Fundamental Investigations. J. Org. Chem 1988, 53, 2287–2294. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Folet J-C; Duprilot J-M; Perichon J; Robin Y; Devynck J. Electrocatalyzed carboxylation of organic halides by a cobalt-salen complex. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985, 26, 2633–2636. [Google Scholar]

- (15) (a).Sequeira CAC; Santos DMF Electrochemical Routes for Industrial Synthesis. J. Braz. Chem. Soc 2009, 20, 387–406. [Google Scholar]; (b) Botte GG Electrochemical Manufacturing in the Chemical Industry. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2014, 23, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- (16) (a).Sasson Y. Formation of Carbon–Halogen Bonds (Cl, Br, I) in Patai’s Chemistry of Functional Groups, Part 11, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gribble GW Naturally Occurring Organohalogen Compounds--A Survey. J. Nat. Prod 1992, 55, 1353–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17) (a).Chatgilialoglu C; Ferreri C; Landais Y; Timokhin VI Thirty Years of (TMS)3SiH: A Milestone in Radical-Based Synthetic Chemistry. Chem. Rev 2018, 118, 6516–6572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Neumann WP Tri-n-butyltin Hydride as Reagent in Organic Synthesis. Synthesis 1987, 1987, 665–683. [Google Scholar]; (c) Brown HC; Midland MM Organic Syntheses uia Free-Radical Displacement Reactions of Organoboranes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1972, 11, 692–700. [Google Scholar]

- (18).For representative reviews, see: (a) Fu GC Transition-Metal Catalysis of Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions: A Radical Alternative to SN1 and SN2 Processes. ACS Cent. Sci 2017, 3, 692–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chuentragool P; Kurandina D; Gevorgyan V. Catalysis with Palladium Complexes Photoexcited by Visible Light. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 11586–11598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Diccianni J; Lin Q; Diao T. Mechanisms of Nickel-Catalyzed Coupling Reactions and Applications in Alkene Functionalization. Acc. Chem. Res 2020, 53, 906–919. For a select example of the mechanistic study of Ni catalysis towards alkyl halide activation, see: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Diccianni JB, Katigbak J, Hu C; Diao T. Mechanistic characterization of (xantphos) Ni(I)-mediated alkyl bromide activation: oxidative addition, electron transfer, or halogen-atom abstraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 1788–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).For representative examples, see: (a) Giedyk M; Narobe R; Weiß S; Touraud D; Kunz W; König B. Photocatalytic activation of alkyl chlorides by assembly-promoted single electron transfer in microheterogeneous solutions. Nat. Catal 2020, 3, 40–47. [Google Scholar]; (b) Aragón J; Sun S; Pascual D; Jaworski S; Lloret-Fillol J. Photoredox Activation of Inert Alkyl Chlorides for the Reductive Cross-Coupling with Aromatic Alkenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2022, 61, e202114365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Constantin T; Zanini M; Regni A; Sheikh NS; Julia F; Leonori D. Aminoalkyl radicals as halogen-atom transfer agents for activation of alkyl and aryl halides. Science 2020, 367, 1021–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lovett GH; Chen S; Xue X-S; Houk KN; MacMillan DWC Open-Shell Fluorination of Alkyl Bromides: Unexpected Selectivity in a Silyl Radical-Mediated Chain Process. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 20031–20036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Chaussard J; Folest J-C; Nedelec J-Y; Perichon J; Sibille S; Troupel M. Use of Sacrificial Anodes in Electrochemical Functionalization of Organic Halides. Synthesis 1990, 1990, 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- (21) (a).Lambert FL; Ingall GB Voltammetry of organic halogen compounds. IV. The reduction of organic chlorides at the vitreous (glassy) carbon electrode. Tetrahedron. Lett 1974, 36, 3231–3234. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cleary JA; Mubarak MS; Vieira KL; Anderson MR; Peters DG Electrochemical Reduction of Alkyl Halides at Vitreous Carbon Cathodes in Dimethylformamide. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem 1986, 198, 107–124. [Google Scholar]; (c) Andrieux CP; Gallardo I; Saveant J-M Outer-Sphere Electron-Transfer Reduction of Alkyl Halides. A Source of Alkyl Radicals or of Carbanions? Reduction of Alkyl Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1989, 111, 1620–1626. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ozaki S; Matsushita H; Ohmori H. Indirect Electroreductive Addition of Alkyl Radicals to Activated Olefins using a Nickel(II) Complex as an Electron-transfer Catalyst. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 1993, 649–651. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wagenknecht JH Electroreduction of alkyl halides in the presence of CO2. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem 1974, 52, 489–492. [Google Scholar]

- (24) (a).Lu Y-W; Nédélec J-Y; Folest J-C; Périchon J. Electrochemical coupling of activated olefins and alkyl dihalides: formation of cyclic compounds. J. Org. Chem 1990, 55, 2503–2507. [Google Scholar]; (b) Satoh S; Taguchi T; Itoh M; Tokuda M. Electrochemical Vicinal Addition of Two Alkyl Groups to Phenyl Substituted Olefins and Diethyl Fumarate. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 1979, 52, 951–952. [Google Scholar]

- (25) (a).Mei H; Yin Z; Liu J; Sun H; Han J. Recent Advances on the Electrochemical Difunctionalization of Alkenes/Alkynes. Chin. J. Chem 2019, 37, 292–301. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sauer GS; Lin S. An Electrocatalytic Approach to the Radical Difunctionalization of Alkenes. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 5175–5187. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Siu JC; Fu N; Lin S. Catalyzing Electrosynthesis: A Homogeneous Electrocatalytic Approach to Reaction Discovery. Acc. Chem. Res 2020, 53, 547–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Zhang W; Lin S. Electroreductive Carbofunctionalization of Alkenes with Alkyl Bromides via a Radical-Polar Crossover Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 20661–20670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28) (a).Lu X; Xiao B; Zhang Z; Gong T; Su W; Yi J; Fu Y; Liu L. Practical carbon-carbon bond formation from olefins through nickel-catalyzed reductive olefin hydrocarbonation. Nat. Commun 2016, 7, 11129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Pang H; Wang Y; Gallou F; Lipshutz BH Fe-Catalyzed Reductive Couplings of Terminal (Hetero)Aryl Alkenes and Alkyl Halides under Aqueous Micellar Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 17117–17124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang Z; Yin H; Fu GC Catalytic enantioconvergent coupling of secondary and tertiary electrophiles with olefins. Nature 2018, 563, 379–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Silvestri G; Gambino S; Filardo G; Gulotta A. Sacrificial Anodes in the Electrocarboxylation of Organic Chlorides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1984, 23, 979–980. [Google Scholar]

- (30) (a).Senboku H; Komatsu H; Fujimura Y; Tokuda M. Efficient Electrochemical Dicarboxylation of Phenyl-substituted Alkenes: Synthesis of 1-Phenylalkane-1,2-dicarboxylic Acids. Synlett 2001, 2001, 418–420. [Google Scholar]; (b) Alkayal A; Tabas V; Montanaro S; Wright IA; Malkov AV; Buckley BR Harnessing Applied Potential: Selective β-Hydrocarboxylation of Substituted Olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 1780–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Dérien S; Clinet J-C; Duñach E; Périchon J. Electrochemical incorporation of carbon dioxide into alkenes by nickel complexes. Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 5235–5248. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Harrington PJ; Lodewijk E. Twenty Years of Naproxen Technology. Org. Process Res. Dev 1997, 1, 72–76. [Google Scholar]

- (33) (a).Haynes N-E; Corbett WL; Bizzarro FT; Guertin KR; Hilliard DW; Holland GW; Kester RF; Mahaney PE; Qi L; Spence CL; Tengi J; Dvorozniak MT; Railkar A; Matschinsky FM; Grippo JF; Grimsby J; Sarabu R. Discovery, structure-activity relationships, pharmacokinetics, and efficacy of glucokinase activator (2R)-3-cyclopentyl-2-(4-methanesulfonylphenyl)-N-thiazol-2-yl-propionamide (RO0281675). J. Med. Chem 2010, 53, 3618–3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jones SS; Yang M; Tamang DL Pyrimidine hydroxy amide compounds as histone deacetylase inhibitors. US 2015105384 A1, 2015.

- (34).For representative reviews, see: (a) Everson DA; Weix DJ Cross-electrophile coupling: principles of reactivity and selectivity. J. Org. Chem 2014, 79, 4793–4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang X; Dai Y; Gong H. Nickel-catalyzed reductive couplings. Top. Curr. Chem 2016, 374, 43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lucas EL; Jarvo ER Stereospecific and stereoconvergent cross-couplings between alkyl electrophiles. Nat. Rev. Chem 2017, 1, 0065. [Google Scholar]

- (35).For select recent examples, see: (a) Kang K; Loud NL; DiBenedetto TA; Weix DJ, A General, Multimetallic Cross-Ullmann Biheteroaryl Synthesis from Heteroaryl Halides and Heteroaryl Triflates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 21484–21491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kang K; Huang L; Weix DJ, Sulfonate Versus Sulfonate: Nickel and Palladium Multimetallic Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Aryl Triflates with Aryl Tosylates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 10634–10640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Weix DJ, Methods and Mechanisms for Cross-Electrophile Coupling of Csp2 Halides with Alkyl Electrophiles. Acc. Chem. Res 2015, 48, 1767–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).For representative examples of the XEC reaction with two alkyl halides, see: (a) Yu X; Yang T; Wang S; Xu H; Gong H. Nickel-catalyzed reductive cross-coupling of unactivated alkyl halides. Org. Lett 2011, 13, 2138–2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu H; Zhao C; Qian Q; Deng W; Gong H. Nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling of unactivated alkyl halides using bis(pinacolato)diboron as reductant. Chem. Sci 2013, 4, 4022–4029. [Google Scholar]; (c) Smith RT; Zhang X; Rincón JA; Agejas J; Mateos C; Barberis M; García-Cerrada S; de Frutos O; MacMillan DWC Metallaphotoredox-Catalyzed Cross-Electrophile Csp3 −Csp3 Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 17433–17438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Nedelec JY; Ait-Haddou-Mouloud H; Folest JC; Perichon J. Electrochemical cross-coupling of alkyl halides in the presence of a sacrificial anode. J. Org. Chem 1988, 53, 4720–4724. For XEC reaction with other electrophiles for C(sp3)–(sp3) bonds formation, see: [Google Scholar]; (e) Liu W; Lavagnino MN; Gould C; Alcázar J; MacMillan DWC A biomimetic SH2 cross-coupling mechanism for quaternary sp3-carbon formation. Science 2021, 374, 1258–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zhang B; Gao Y; Hioki Y; Oderinde MS; Qiao JX; Rodriguez KX; Zhang H-J; Kawamata Y; Baran PS Ni–Electrocatalytic C(sp3)−C(sp3) Doubly Decarboxylative Coupling. Nature 2022, 606, 313–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Kang K; Weix DJ Nickel-Catalyzed C(sp3)-C(sp3) Cross-Electrophile Coupling of In Situ Generated NHP Esters with Unactivated Alkyl Bromides. Org. Lett 2022, 24, 2853–2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Fu H; Cao J; Qiao T; Qi Y; Charnock SJ; Garfinkle S; Hyster TK An asymmetric sp3–sp3 cross-electrophile coupling using ‘ene’-reductases. Nature, 2022, 610, 302–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Zhang W; Lu L; Zhang W; Wang Y; Ware SD; Mondragon J; Rein J; Strotman N; Lehnherr D; See KA; Lin S. Electrochemically Driven CrossElectrophile Coupling of Alkyl Halides. Nature 2022, 604, 292–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Sandford C; Aggarwal VK Stereospecific functionalizations and transformations of secondary and tertiary boronic esters. Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 5481–5494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).McMillan AJ; Sieńkowska M; Di Lorenzo P; Gransbury GK; Chilton NF; Salamone M; Ruffoni A; Bietti M; Leonori D. Practical and selective sp3 C−H bond chlorination via aminium radicals. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2021, 60, 7132–7139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Wood DP; Lin S. Deuterodehalogenation Under Net Reductive or Redox-Neutral Conditions Enabled by Paired Electrolysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2023, e202218858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42) (a).Cheng C; Hartwig JF Catalytic Silylation of Unactivated C–H Bonds. Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 8946–8975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brook MA Silicon in Organic, Organometallic, and Polymer Chemistry; Wiley–Interscience: New York, 2000. [Google Scholar]; (c) Klare HFT; Albers L; Süsse L; Keess S; Müller T; Oestreich M. Silylium Ions: From Elusive Reactive Intermediates to Potent Catalysts. Chem. Rev 2021, 121, 5889–5985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Denmark SE; Sweis RF Cross-coupling reactions of organosilicon compounds: New concepts and recent advances. Chem. Pharm. Bull 2002, 50, 1531–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Franz AK; Wilson SO Organosilicon Molecules with Medicinal Applications. J. Med. Chem 2013, 56, 388–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45) (a).Yajima S; Hayashi J; Omori M. Continuous silicon carbide fiber of high tensile strength. Chem. Lett 1975, 4, 931–934. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yajima S. Development of Ceramics, Especially Silicon Carbide Fibres, from Organosilicon Polymers by Heat Treatment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 1980, 294, 419–426. [Google Scholar]

- (46) (a).Lalonde M; Chan TH Use of Organosilicon Reagents as Protective Groups in Organic Synthesis. Synthesis 1985, 9, 817–845. [Google Scholar]; (b) Vulovic B; Cinderella AP; Watson DA Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Monochlorosilanes and Grignard Reagents. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 8113–8117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Weyenberg DR; Toporcer LH; Bey The Disilylation of Styrene and α-Methylstyrene. The Trapping of Short-Lived Intermediates from Alkali Metals and Aryl Olefins. J. Org. Chem 1965, 30, 4096–4101 [Google Scholar]

- (48).Li J-S; Wu J. Recent Developments in the PhotoMediated Generation of Silyl Radicals and Their Application in Organic Synthesis. ChemPhotoChem. 2018, 2, 839–846. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Shang X; Liu ZQ Recent developments in free-radical-promoted C-Si formation: Via selective C-H/Si-H functionalization. Org. Biomol. Chem 2016, 14, 7829–7831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).For representative examples, see: (a) Zhou R; Goh YY; Liu H; Tao H; Li L; Wu J. Visible-Light-Mediated Metal-Free Hydrosilylation of Alkenes through Selective Hydrogen Atom Transfer for Si−H Activation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 16621–16625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hou J; Ee A; Cao H; Ong HW; Xu JH; Wu J. Visible-Light-Mediated Metal-Free Difunctionalization of Alkenes with CO2 and Silanes or C(sp3 )−H Alkanes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2018, 57, 17220–17224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Finholt AE; Bond AC; Wilzbach KE; Schlesinger HI The Preparation and Some Properties of Hydrides of Elements of the Fourth Group of the Periodic System and of their Organic Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1947, 69, 2692–2696. [Google Scholar]

- (52) (a).Yu X; Lübbesmeyer M; Studer A. Oligosilanes as Silyl Radical Precursors through Oxidative Si–Si Bond Cleavage using Redox Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2021, 60, 675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yu X; Daniliuc CG; Alasmary FA; Studer A. Direct Access to a-Aminosilanes Enabled by Visible-Light-Mediated Multicomponent Radical Cross-Coupling. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2021, 60, 23335–23341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Matsumoto A; Ito Y. New generation of organosilyl radicals by photochemically induced homolytic cleavage of silicon-boron bonds. J. Org. Chem 2000, 65, 5707–5711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Lamas MC; Studer A. Radical alkylphosphanylation of olefins with stannylated or silylated phosphanes and alkyl iodides. Org. Lett 2011, 13, 2236–2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55) (a).Studer A; Amrein S. Silylated Cyclohexadienes: New Alternatives to Tributyltin Hydride in Free Radical Chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2000, 39, 3080–3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu NX; Li BX; Wang C; Uchiyama M. Sila- and Germacarboxylic Acids: Precursors for the Corresponding Silyl and Germyl Radicals. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2020, 59, 10639–10644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Hengge E; Litscher G. A New Electrochemical Method of Forming Si-Si Bonds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 1976, 15, 370. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Shono T; Kashimura S; Ishifune M; Nishida R. Electroreductive formation of polysilanes. J. Chem. Soc., Chem, Commun 1990, 17, 1160–1161. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Few electrochemical reductions of chlorosilanes towards C-Si bonds formation have been reported via an anion mechanism (a) Shono T; Ishifune M; Kinugasa H; Kashimura S. Electrochemically Promoted Cyclocoupling of 1,3-Dienes or Styrenes with Aliphatic Carboxylic Esters. J. Org. Chem 1992, 57, 5561–5563. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kunai A; Ueda T; Toyoda E; Ishikawa M. Electrochemical reduction of dichlorosilanes in the presence of 2, 3-dimethylbutadiene. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 1994, 67, 287–289. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Lu L; Siu JC; Lai Y; Lin S. An electroreductive approach to radical silylation via the activation of strong Si–Cl bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 21272–21278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).He G; Shynkaruk O; Lui MW; Rivard E. Small inorganic rings in the 21st Century: From fleeting intermediates to novel isolable entities. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 7815–7880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61) (a).Obligacion JV; Chirik PJ Earth-abundant transition metal catalysts for alkene hydrosilylation and hydroboration. Nat. Rev. Chem 2018, 2, 15–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Oestreich M. Transfer Hydrosilylation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 494–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62) (a).Miller RD; Michl J. Polysilane high polymers. Chem. Rev 1989, 89, 1359–1410. [Google Scholar]; (b) Marschner C. Oligosilanes. In Functional Molecular Silicon Compounds I: Regular Oxidation States; Scheschkewitz D, Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 163–228. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mignani G; Krämer A; Puccetti G; Ledoux I; Soula G; Zyss J; Meyrueix R. A new class of silicon compounds with interesting nonlinear optical effects. Organometallics 1990, 9, 2640–2643. [Google Scholar]; (d) Surampudi S; Yeh M-L; Siegler MA; Hardigree JFM; Kasl TA; Katz HE; Klausen RS Increased carrier mobility in end-functionalized oligosilanes. Chem. Sci 2015, 6, 1905–1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Reviews on activation of disilanes: (a) Cheng C; Hartwig JF Catalytic silylation of unactivated C–H bonds. Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 8946–8975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xiao P; Gao L; Song Z. Recent Progress in the Transition‐Metal‐Catalyzed Activation of Si−Si Bonds to Form C−Si Bonds. Chem. Eur. J 2019, 25, 2407–2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Shimada M; Yamanoi Y; Matsushita T; Kondo T; Nishibori E; Hatakeyama A; Sugimoto K; Nishihara H. Optical properties of disilane-bridged donor–acceptor architectures: Strong effect of substituents on fluorescence and nonlinear optical properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 1024–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Jones RG, Holder SJ Synthesis of polysilanes by the wurtz reductive-coupling reaction. In Silicon-Containing Polymers, Springer, Dordrecht. 2000, 353–373 [Google Scholar]

- (66) (a).Corey JY; Zhu XH; Bedard TC; Lange LD Catalytic Dehydrogenative Coupling of Secondary Silanes with Cp2MCl2. Organometallics 1991, 10, 924–929. [Google Scholar]; (b) Itazaki M; Ueda K; Nakazawa H. Iron-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Coupling of Tertiary Silanes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2009, 48, 3313–3316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Shishido R; Uesugi M; Takahashi R; Mita T; Ishiyama T; Kubota K; Ito H. General Synthesis of Trialkyl- and Dialkylarylsilylboranes: Versatile Silicon Nucleophiles in Organic Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 14125–14133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Guan W; Lu L; Jiang Q; Gittens A; Wang Y; Novaes L; Klausen R; Lin S. Electrochemical logic to synthesize disilanes and oligosilanes from chlorosilanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2023, DOI: 10.1002/anie.202303592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Press EM; Marro EA; Surampudi SK; Siegler MA; Tang JA; Klausen RS Synthesis of a Fragment of Crystalline Silicon: Poly(Cyclosilane). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 568–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Chen SM; Katti A; Blinka A; West R. Convenient Syntheses of Dodecamethylcyclohexasilane und Decamethylcyclopentasilane. Synthesis, 1985, 6, 684–686. [Google Scholar]

- (71).Synthesis of structurally similar compounds have been reported which require addition of reagents like 18-crown-ether: Purkait TK, Press EM, Marro EA, Siegler MA, & Klausen RS Low-Energy Electronic Transition in SiB Rings. Organometallics, 2018, 38, 1688–1698. [Google Scholar]

- (72).Hu P; Peters BK; Malapit CA; Vantourout JC; Wang P; Li J; Mele L; Echeverria P-G; Minteer SD; Baran PS Electroreductive Olefin-Ketone Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 20979–20986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73) (a).Wang Y; Tang S; Yang G; Wang S; Ma D; Qiu Y. Electrocarboxylation of Aryl Epoxides with CO2 for the Facile and Selective Synthesis of β-Hydroxy Acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2022, e202207746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huang C; Ma W; Zheng X; Xu M; Qi X; Lu Q. Epoxide Electroreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 1389–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Turro RF; Brandstätter M; Reisman SE Nickel-Catalyzed Reductive Alkylation of Heteroaryl Imines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2022, e202207597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75) (a).Hayashi K; Griffin J; Harper KC; Kawamata Y; Baran PS Chemoselective, Metal-free, (Hetero)Arene Electroreduction Enabled by Rapid Alternating Polarity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 5762–5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Peters BK; Rodriguez KX; Reisberg SH; Beil SB; Hickey DP; Kawamata Y; Collins M; Starr J; Chen L; Udyavara S; Klunder K; Gorey TJ; Anderson SL; Neurock M; Minteer SD; Baran PS Scalable and Safe Synthetic Organic Electroreduction Inspired by Li-Ion Battery Chemistry. Science 2019, 363, 838–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).DeLano TJ; Reisman SE Enantioselective Electroreductive Coupling of Alkenyl and Benzyl Halides via Nickel Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 6751–6754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).For representative examples, see: (a) Hamby TB; LaLama MJ; Sevov CS Controlling Ni redox states by dynamic ligand exchange for electroreductive Csp3–Csp2 coupling. Science 2022, 376, 410–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gao Y; Hill DE; Hao W; McNicolas BJ; Vantourout JC; Hadt RG; Reisman SE; Blackmond D; Baran PS Electrochemical Nozaki–Hiyama–Kishi Coupling: Scope, Applications, and Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143, 9478–9488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wu X; Gannett CN; Liu J; Zeng R; Novaes LFT; Wang H; Abruña HD; Lin S. Intercepting Hydrogen Evolution with Hydrogen-Atom Transfer: Electron-Initiated Hydrofunctionalization of Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022. 144, 17783–17791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Harwood SJ; Palkowitz MD; Gannett CN; Perez P; Yao Z; Sun L; Abruña HD; Anderson SL; Baran PS Modular Terpene Synthesis Enabled by Mild Electrochemical Couplings. Science 2022, 375, 745–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]