Abstract

An emerging body of literature describes the prevalence and consequences of hypercapnic respiratory failure. While device qualifications, documentation practices, and previously performed clinical studies often encourage conceptualizing patients as having a single “cause” of hypercapnia, many patients encountered in practice have several contributing conditions. Physiologic and epidemiologic data suggest that sleep-disordered breathing – particularly obstructive sleep apnea – often contributes to the development of hypercapnia. In this review, we summarize the frequency of contributing conditions to hypercapnic respiratory failure among patients identified in critical care, emergency, and inpatient settings with an aim toward understanding the contribution of OSA to the development of hypercapnia.

Keywords: Hypercapnia, Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure, Hypoventilation, Respiratory Insufficiency, Sleep Apnea, Non-invasive Ventilation, Positive Airway Pressure

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old female with no previously obtained spirometry or sleep testing presented with confusion. She was admitted to the ICU for non-invasive ventilation after a venous blood gas obtained in the emergency room showed a pH of 7.25 and a PaCO2 of 72mm Hg. She is a current smoker and has body mass index of 36 kg/m2. A chest CT scan was negative for pulmonary embolism but showed mild centrilobular emphysema. An echocardiogram shows right ventricle enlargement, elevated left-ventricular diastolic filling pressures, and a normal ejection fraction. The patient improved with non-invasive ventilation, diuresis, steroids, and antibiotics. She was discharged on 1liter/min of supplemental oxygen. The sleep clinic is contacted to facilitate a sleep study. How important is it to diagnose co-morbid OSA, and how urgently should a sleep study be performed?

Introduction

The health impact of hypercapnic respiratory failure (an increase in arterial blood carbon dioxide resulting from insufficient alveolar ventilation to match the metabolic production of carbon dioxide) is under-appreciated, irrespective of clinical circumstance. An emerging body of evidence suggests that hypercapnic respiratory failure is common1 and associated with significant morbidity2 and mortality risk3. One in four hospitalized patients who receive a diagnostic code for hypercapnic respiratory failure are readmitted within 30 days4. Even amongst inpatients whose arterial blood gas (ABG) is consistent with compensated hypercapnia (normalization of blood pH), roughly one in three die within one year5.

Changes in the physiology of breathing during sleep usually lead to the development of hypercapnia initially at night. An increasing body of research highlights the role of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), particularly OSA, in developing hypercapnia. In this paper, we review the pertinent physiologic principles governing the occurrence of hypercapnia. We then review the existing literature to answer the common clinical scenario outlined in the case above – when a patient is identified as having hypercapnic respiratory failure, what is the likely contribution of sleep apnea in the development of their condition? We also discuss challenges encountered in research assessing the impact of OSA on hypercapnic respiratory failure risk that limit the strength of the current evidence pointing to the role of OSA in hypercapnia seen in hospitalized settings.

Background

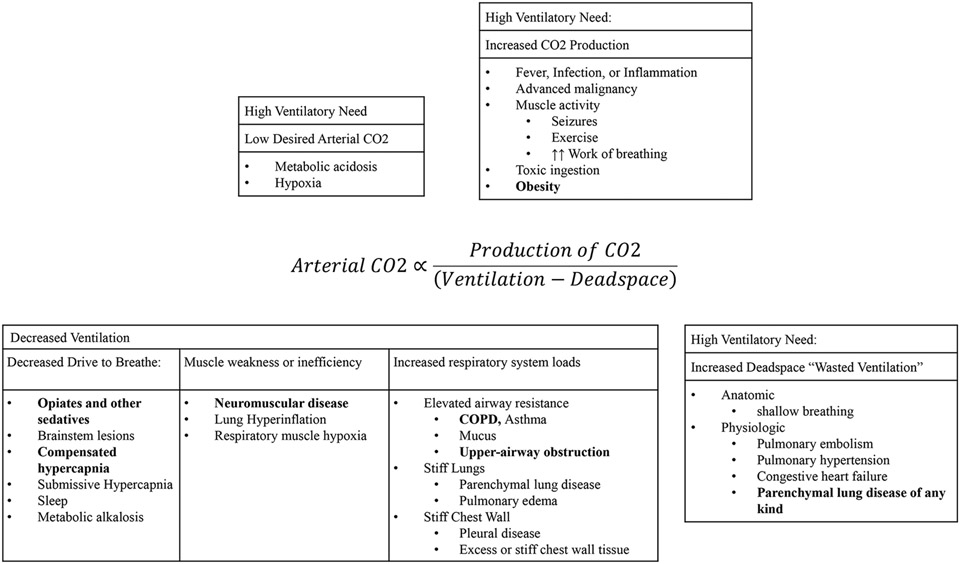

Hypercapnic (synonymously, hypercarbic6) respiratory failure occurs when the amount of inhaled air participating in gas exchange (alveolar ventilation, ) is insufficient to match carbon dioxide production () from cellular metabolism. The resulting rise in the partial pressure of CO2 in arterial blood (PaCO2) to above 45 mmHg (at sea level) operationally defines hypercapnic respiratory failure. Numerous disease states can contribute to the development of hypercapnic respiratory failure through differing physiologic mechanisms (Figure 1)7:

Figure 1: Determinants of the arterial blood CO2 tension.

The efficiency of ventilation refers to the portion of ventilation (air moved by the respiratory system) that participates in gas exchange. Deadspace (Vd) is synonymous with “wasted ventilation” that does not participate in gas exchange. Therefore, the unwasted ventilation is one minus the deadspace fraction (Vd/Vt, Vt refers to the overall tidal volume). The production of CO2 () depends on the overall metabolic rate, and the portion of that is aerobic vs anaerobic. Each condition can contribute to hypercapnia through multiple mechanisms (e.g. COPD may result in elevated deadspace, resistive respiratory system loads, and mechanical disadvantage from hyperinflation) and multiple diseases can contribute to each physiologic abnormality.

(From Sleep Med Clin 9 (2014) 289–300 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2014.05.014 Berger et al., but originally appearing in the Journal of Applied Physiology.)

Increasing the rate of CO2 production that must be exhaled (increased )

Reducing the efficiency of ventilation (by increasing dead space or reducing desired arterial CO2 tension)

Increasing the work required for a given amount of ventilation due to either increased resistance to airflow (such as obstructive airway disease) or increased elastic or inertial loads (such as stiff lungs or excess chest wall mass, respectively)

Decreasing the capacity of the respiratory apparatus to do work (neuro-muscular disease or mechanical disadvantage)

Disrupting the usual feedback loops that lead to increased ventilation in response to rising blood CO2.

Hypercapnic respiratory failure is difficult to diagnose. Except for the use of capnography in some procedural and intensive care settings, arterial CO2 levels are not monitored or estimated as part of routine care. Clinicians must actively look for hypercapnia and order appropriate diagnostic testing. Signs and symptoms of hypercapnic respiratory failure, such as confusion, lethargy, tachycardia, and shortness of breath (or its absence), are non-specific. Furthermore, empiric supportive respiratory care often temporarily stabilizes patients without properly understanding the cause(s) of hypercapnia. Thus, hypercapnic respiratory failure is frequently missed in clinical practice8-10.

Hypercapnic respiratory failure and sleep are intertwined11. Several physiologic changes to the respiratory system promote the development of hypercapnia during sleep12,13. First, the respiratory control system becomes less responsive to increases in blood CO2, particularly during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep14. Mechanical changes to the respiratory system also occur15. Supine positioning reduces lung volumes, particularly in patients with excess abdominal adiposity16, which predisposes the upper airway to narrowing or collapse and thereby causes obstructive hypopneas or apneas17. Skeletal muscles, except the diaphragm, are hypotonic during REM. In healthy individuals, this contributes to a 13% decrease in the tidal volume and minute ventilation18. The metabolic production of CO2 drops during sleep, but the minute ventilation drops even more, resulting in a rise in blood CO2 levels19. In healthy individuals, the arterial CO2 tension can increase up to 4-6mmHg during sleep20. However, individuals who rely more on accessory muscles, such as those with muscular dystrophies, phrenic nerve injuries, or hyperinflation, experience a greater decrease in ventilation during REM sleep. Pathologic nocturnal hypoventilation is defined by an increase in CO2 to 55 mmHg (or above 50 mmHg and more than 10 mmHg above awake, supine CO2) sustained for ten or more minutes measured using end-tidal or transcutaneous CO2 monitoring.21

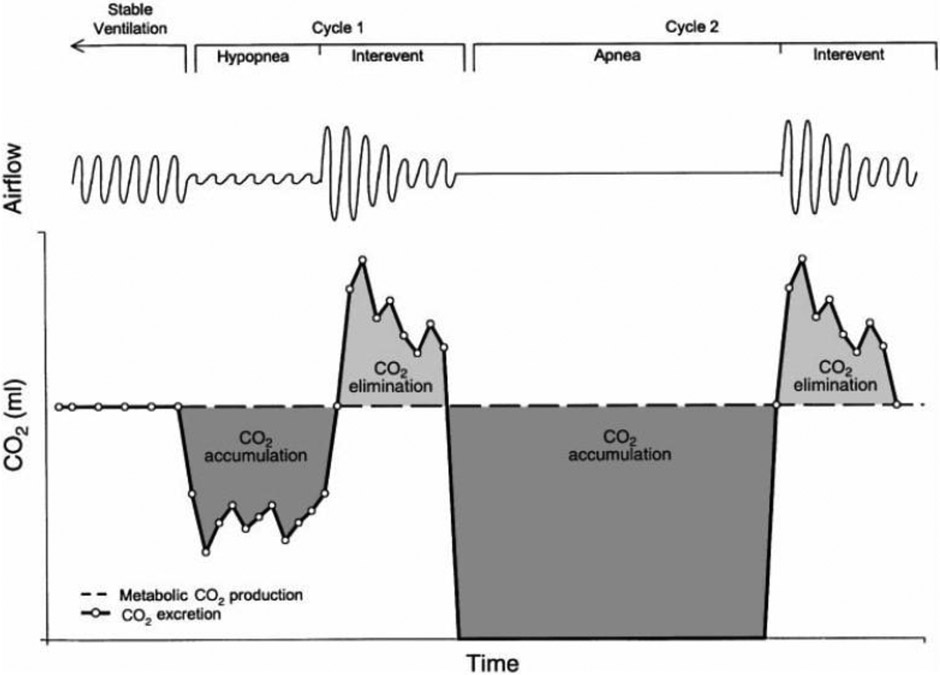

Nocturnal hypoventilation is often an initial manifestation of a disease state that will subsequently lead to daytime hypoventilation22,23, but sleep-disordered breathing can also lead to hypercapnia on its own. Increases in blood CO2 levels occur during obstructive apneas because ventilation halts while metabolic CO2 production continues (Figure 2). Ventilation must increase between apneic events to unload the accumulating CO2. Otherwise, the blood CO2 level will rise24. Hypercapnia develops when obstructive respiratory events are either frequent or prolonged enough or the inter-event increase in ventilation is limited12. Therefore, “pure” sleep hypoventilation and hypoventilation resulting from sleep apnea exist on a spectrum rather than as discrete categories, particularly in patients who do not appropriately increase their ventilation between apneas12. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) epitomizes this spectrum. Patients with OHS and severe OSA resolve their hypercapnia following treatment of obstructive respiratory events by continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)25. In contrast, patients with a more “pure hypoventilation” without significant OSA are recommended Bilevel PAP (BPAP)26,27. A similar spectrum of resolution of hypercapnia in response to OSA treatment likely occurs in other “overlap syndromes,” such as COPD and OSA28,29, though insufficient evidence exists for strong management recommendations30.

Figure 2: CO2 Loading During Apneas and Hypopneas.

Apneas and hypopneas can lead to an accumulation of CO2 in the arterial blood, particularly if the inter-event ventilation is not able to increase because metabolic CO2 production continues while alveolar ventilation drops. According to this model, more frequent events (a higher Apnea-Hypopnea Index), longer events, or a limited ability to increase the amount of ventilation between obstructions will lead to progressive nocturnal CO2 accumulation. In combination with any underlying respiratory system abnormalities, bicarbonate retention by the kidneys to minimize the change to blood pH is then hypothesized to lessen the tendency to normalize the nocturnal loading, eventual leading to daytime hypercapnic respiratory failure.

From Berger et al J Appl Physiol 88:257-264 (2000)12,94; with permission.

In summary, changes in the mechanics and regulation of breathing during sleep lead to the initial development of hypercapnia at night. Sleep apnea, mainly when severe or co-occurring with limited ability to increase inter-event alveolar ventilation, contributes to nocturnal CO2 accumulation. In specific diseases, such as OHS with severe OSA, addressing sleep apnea prevents or resolves hypercapnic respiratory failure. Indirect evidence suggests that treating OSA might reduce or prevent respiratory decompensations in patients with other causes, multifactorial causes, or undifferentiated cases of hypercapnic respiratory failure31-33. However, the degree of benefit would depend on how large the contribution of OSA is amongst different etiologies of hypercapnic respiratory failure. The remainder of this article focuses on quantifying the role of untreated OSA in hypercapnic respiratory failure encountered in various clinical settings.

Epidemiology

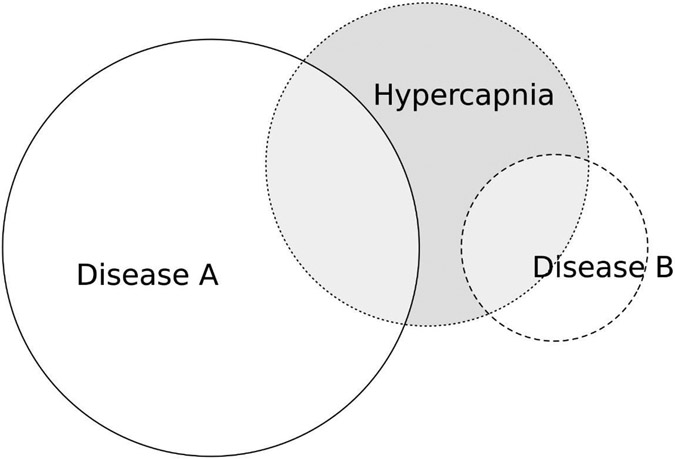

Research on hypercapnic respiratory failure has generally focused on what factors differ between patients with or without hypercapnia among patients who have specific diseases that can cause hypercapnic respiratory failure, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD34), obesity with sleep-disordered breathing (obesity-hypoventilation syndrome, OHS35-37), restrictive chest wall disease38,39, or neuromuscular disease (NMD40,41). However, clinicians often face an “inverse problem”42,43 where hypercapnic respiratory failure has been identified, but the conditions that have led to hypercapnia must be determined (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Spatial Representation of the “Inverse Problem” of Conditional Probability.

The probability of having a disease among patients identified with hypercapnia [represented as: P(disease ∣ hypercapnia) in statistical notation] may be much different from the probability that a patient with a disease develops hypercapnia [P(hypercapnia ∣ disease)]. This is an important difference because clinicians often recognize hypercapnia before knowing the cause, and thus, P (disease ∣ hypercapnia) is the expected rate for finding that disease in subsequent investigations. In this case, only 1 in 5 cases of “Disease A” develop hypercapnia, while 1 in 2 cases of “Disease B” do. However, because Disease A is much more common, the likelihood of hypercapnia being caused by Disease A is double that of Disease B. It has been suggested that Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome is the most common current cause of hypercapnia (see Table 3), despite most patients with obesity and OSA not developing hypercapnia37. Figure generated using ‘eulurr’ package95.

This question is important for clinicians because hypercapnic respiratory failure is often identified in acute care settings (ICU, Emergency Department, or Inpatient Ward), where definitive diagnostic studies such as spirometry, polysomnography, and electromyography have not been performed and cannot be obtained immediately. In the specific case of OSA, care must be transitioned to an outpatient sleep physician to diagnose and manage OSA, as the qualification criteria for respiratory assist devices (in the United States) limit empiric management44. The urgency of this referral depends on whether OSA is commonly an important cause of hypercapnia or not.

Both clinicians and researchers are interested in what portion of hypercapnic respiratory failure cases would be averted if OSA were prevented or treated because this guides the extent to which addressing sleep-disordered breathing should be prioritized in this group. In each patient, OSA can be an important driver, a weak contributor, or unrelated to the development of hypercapnia. Frequent co-occurrence alone is, therefore, insufficient evidence that OSA is an important cause of hypercapnia. However, an important role is supported if OSA is more common in patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure than otherwise appropriately matched patients who don't have hypercapnia45,46. The current literature, with few exceptions47, does not contain matched control groups. Inferences about the excess risk caused by OSA therefore rely on implied comparisons, which limits the strength of evidence.

In the following section, we consider the evidence supporting OSA’s role as a cause of hypercapnic respiratory failure in various settings. The patient mix and the methodologies of studies differ between the intensive care, inpatient, emergency, and outpatient settings. Thus, we have subdivided our discussion into those groups.

Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

The diagnosis of hypercapnic respiratory failure is often made in the ICU, where patients with the most severe respiratory decompensation that require ventilatory support are encountered. A summary of studies evaluating comorbidities of patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure in the ICU is shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Prevalence of OSA among ICU survivors of hypercapnic respiratory failure

| Author | Year, Location | Enrollment Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Method of Assessment |

Loss to Follow-up |

Rate of Mod- Severe OSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective without Protocolized Comorbidity Assessment. | ||||||

| Contou et al48 | France, 2008-2011 | pH <7.35 and PaCO2 > 45 mmHg | Invasive Mechanical Ventilation or DNI | Chart review | Not Applicable | 30 of 242 (12%) |

| Prospective Studies with Protocolized Ascertainment | ||||||

| Adler et al.51 | France 2012-2015 | PaCO2 over 47.25 mmHg. NIV or IMV treatment | neuromuscular disease, prognosis < 3 months, iatrogenic hypercapnia, persistent confusion | PSG 3 months after discharge | 53% | 28 of 37 (75%) |

| Thille et al. 50 | Prior to 2018 (precise dates not reported) | pH<7.35 and PaCO2 45 mmHg treated with NIV or IMV | none | PSG 3 months after discharge | 54% | 14 of 16 (88%) |

| Ouanes-Besbes et al. 49 | Tunisia, 2015-2018 | pH < 7.35 and PaCO2 > 47.5 mmHg | Previously diagnosed OSA. | HSAT 3 weeks after discharge | 24% | 104+ of 164 (63%); 34 not tested (STOP-BANG <3) |

| Gursel et al.52 | Turkey, not reported. | Hypercapnia treated with NIV | None | Respiratory Polygraph during ICU | 0% | 20 of 31 (64%), hypopneas not assessed. |

PaCO2: Arterial gas tension of CO2. IMV: Invasive Mechanical Ventilation. NIV: Non-Invasive Ventilation. DNI: Do Not Intubate advanced directive. PSG: Polysomnogram. HSAT: Home Sleep Apnea Testing. Mod-Severe OSA: Apnea-hypopnea index over 15 events/hour. STOP-BANG: risk stratification score for OSA.

All studies included patients using an arterial blood gas criterion (either a PaCO2 over 45 mmHg or 6 kPa) and either a pH consistent with uncompensated respiratory acidosis (Contou et al.48 and Ouanes-Besbes et al.49) or requirement that patients received non-invasive (NIV) or invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV, Thille et al.50 Adler et al.51 Gursel et al.52). OSA/OHS was uncommon (12% of 230 patients) in the single study that relied on clinician attribution (Contou et al.48).

In contrast, moderate or severe OSA was very common in the three studies where patients underwent sleep testing ranging from 63%-88% (75% of 37 patients in Adler et al.51, 88% of 16 patients in Thille et al.50, and 63% in Ouanes-Besbes et al.49). Notably, these three studies used either in-lab polysomnography three months after ICU discharge (Adler et al.51 and Thille et al.50) or home sleep apnea tests three weeks after discharge (Ouanes-Besbes et al.49). All had very low rates of follow-up among patients invited for testing (46%51, 47%50, and 76% 49, respectively).

This low follow-up rate, even among the patients who consent to participate in research, suggests that many patients are lost when transitioning from inpatient to outpatient care and thus may not receive definitive evaluation in routine clinical care. These patients often encounter issues preventing timely access to follow-up, and recognition for the need for treatment may be lacking for both patients and providers. This is particularly problematic given the high likelihood of early readmissions for patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure4. Gursel et al.52 reported that respiratory polygraphy during ICU admission identified OSA in 8 of 11 patients diagnosed with OHS and 12 of 21 patients with COPD and hypercapnia (overall rate of OSA of 64%). Alternatively, Adler and colleagues reported that the absence of hyperinflation (as assessed by plethysmography) might select survivors of hypercapnia with a particularly high likelihood of moderate-severe OSA53. However, plethysmography is also not easily performed in acute care settings.

Overall, OSA is identified in ICU patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure at a roughly 5-fold higher rate (63-88%) when sleep testing is performed compared to when clinicians’ assessment of the cause is used (12%). While OSA is likely common and unrecognized among all ICU patients (for example, Bucklin and colleagues54 estimate that 40% of ICU have moderate or severe OSA), a more likely explanation is that OSA at least contributes to the development of hypercapnia in many more cases than are commonly recognized in practice or coded in documentation.

While it is common to document the “single cause” of hypercapnic respiratory failure, as encouraged by device-qualification practices (which often require the absence of other contributors in the US, thus dissuading searching for and documenting their presence44), there is both physiologic and epidemiologic evidence that multiple conditions often contribute to the occurrence of hypercapnia. Physiologically, the model of CO2 loading during apneas (Figure 2) predicts that limitations on the ability to increase inter-apnea ventilation will lead to the early development of hypercapnia24. This is corroborated empirically, as hypercapnia develops in patients with OSA-COPD overlap syndrome with milder obstruction than in the pure COPD case and milder obesity55. In the three prospective ICU cohorts, very high rates of multiple contributors were noted. Adler et al. found that 36% of their cohort had COPD and OSA, 61% had OSA and congestive heart failure (CHF), and 54% had CHF and COPD51.

In summary, the available evidence on ICU patients treated for hypercapnic respiratory failure suggests a very high rate of undiagnosed sleep apnea that is often not recorded as a contributor to hypercapnic respiratory failure. The prospective ascertainment of comorbidity status is a notable strength of these studies, though low follow-up rates for sleep studies limit the strength of conclusions.

Emergency Department and Inpatient Ward

Several studies have investigated hypercapnic respiratory failure in hospitalized and emergency room patients, mostly relying on retrospective health record data (Table 2).

Table 2:

Prevalence of OSA among patients presenting to the emergency room or admitted to the hospital with hypercapnic respiratory failure

| Author | Year/ Location |

Enrollment Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Method of Assessment |

Loss to Follow-up |

Prevalence of OSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective, arterial blood gas assessment in all patients, but no structured OSA assessment | ||||||

| Nowbar et al8 | USA, before 2004(not stated) | Arterial blood gas PaCO2 > 2 SD above norm. | Severe obstruction (FEV1/FVC < 0.5); lung resection | Inferred from lack of other identified causes | Not Applicable | 31% |

| Retrospective, all patients received polysomnography | ||||||

| Johnson et al.61 | USA 2015-2018 | Inpatient PSG ordered, PaCO2 > 45 or TcCO2/EtCO2 > 50 mmHg for 10+ minutes | No titration study performed | Inpatient PSG | None | 65%† |

| Prospective with structured comorbidity ascertainment | ||||||

| Chung et al.47 | Australia 2013-2017 | PaCO2 over 45 mmHg | Iatrogenic causes, trauma, post-arrest. | HSAT (case-control study) ‡ | 90% | 28% in cases (vs 34% in controls) |

| Retrospective Studies | ||||||

| Chung et al.1,56 | Australia 2013-2017 | PaCO2 over 45 mmHg | Iatrogenic causes, trauma, post-arrest. | Diagnosis code | Not Applicable | 6% |

| Cavalot et al.2 | Canada 2017 | ABG: CO2 > 45 & pH < 7.35 or VBG: CO2 > 50 & pH < 7.34 | cystic fibrosis, neuromuscular disease, ILD, lung cancer, drug overdose, or tracheostomy. | Diagnosis code | Not Applicable | 19.3% |

| Meservey et al.4 | USA 2016 | Diagnostic Code for Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure | Advanced cancer, trauma, stroke, seizure, cardiac arrest, advanced neurologic disease, serious non-pulmonary illness. | Chart review | Not Applicable | 24% |

| Vonderbank et al.3 | Germany 2015-2016 | Arterialized capillary blood gas CO2 > 45 mmHg | None | Health record review | Not Applicable | 10.8% |

| Wilson et al.5 | USA 2018 | PaCO2 > 50 mmHg and pH > 7.35 | Admitted at psychiatric or inpatient rehabilitation hospitals. | EMR problem list | Not Applicable | 22.4% |

| Domaradzki et al.63 | USA 2009-2015 | Diagnostic code for COPD or respiratory failure & VBG | tracheostomy | Home CPAP (or BPAP) | Not Applicable | 10% (and 5%) |

| Bülbül et al.62 | Turkey 2009-2010 | Initial and follow-up (stable) PaCO2 > 45 mmHg | Acute hypercapnia | Inferred from lack of other identified causes | Not Applicable | 25% |

| Fox et al.96 | Israel 2012-2017 | Referral for NIV on discharge | Death during admission | Chart Review | Not Applicable | 5% |

| Segreelles Calvo et al.97 | Spain 2008-2009 | PaCO2 over 45 mmHg and pH <7.35 | None | Chart Review | Not Applicable | 6% |

| Brandão et al.98 | Portugal 2012-2013 | NIV use outside an ICU (90% Hypercapnic) | Elective admissions | Chart Review | Not Applicable | 23% |

ABG: arterial blood gas. VBG: peripheral venous blood gas. SD: standard deviation, FEV1/FVC: Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second over Forced Vital Capacity. EMR: electronic medical record. CPAP: Constant Positive Airway Pressure. BPAP: Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure.

Only patients referred for inpatient sleep testing included.

Cases come from the hospital, but controls are taken from the general population.

Chung and colleagues leveraged data from a single hospital serving a defined population in Liverpool, Australia, to publish several informative studies1,47,56. They included patients with a measured arterial PaCO2 over 45 mmHg within 24 hours of hospital presentation, after excluding iatrogenic causes, from 2013-2017. By standardizing the rate of hypercapnia to the region’s demographics, they estimated the yearly period prevalence of hypercapnia in acute care settings to be 163 per 100,000 person-years, and the prevalence roughly doubling with each decade of age above 501.

Next, they investigated conditions that may have led to the development of hypercapnia. In the cohort, obstructive lung disease codes were the most common diagnostic code (n=389, 44.6%), followed by CHF (n=278, 31.8%)56. In contrast to other studies, only 6.0% (n=52) had a sleep-disordered breathing diagnosis code, and only 13% had diagnostic codes for multiple contributing conditions.

They then selected a subset of patients with hypercapnia (cases) and a matched sample of patients in the community (controls) to determine which diseases occurred in excess among people with hypercapnic respiratory failure47. Among the subsample, 43% of patients with hypercapnia (vs 12% of controls) reported they had OSA. However, home sleep apnea tests found moderate-severe OSA at equivalent rates between cases and controls (28% cases, 34% controls). Response rates with follow-up testing were very low in both cases and controls (roughly 1 in 10), reinforcing the difficulty of establishing the diagnosis of OSA once patients are discharged from the hospital.

Comparatively little is known about the epidemiology of sleep-breathing disorders among hospitalized patients.57,58 Several groups have attempted to estimate the prevalence of OSA among general inpatients, and compare it with the prevalence of OSA in those patients with hypercapnia. Using a screening program based on STOP-BANG and high-resolution pulse oximetry, the estimated prevalence of sleep apnea among patients with obesity was 19.7% at a single center59. Higher rates (48%) are seen in patients with cardiovascular disease60. Among the subset of hospitalized patients referred for inpatient sleep testing, Johnson et al.61 found that patients usually had either nocturnal or diurnal hypoventilation (65% of 326 patients) on inpatient polysomnogram with CO2 monitoring. Patients also had high rates of sleep apnea (17% mild, 21% moderate, and 56% severe), OHS (59%, operationally defined as other factors not entirely explaining the hypoventilation), and other comorbidities (68% had CHF and 35% had COPD).

Several other studies show similar distributions of comorbidities as assessed by diagnostic codes. Rates of recognized OSA vary from 10-25%, with either COPD2,3,62,63 or CHF5 being the most common comorbidity. The frequency of obesity ranges from a mean BMI of 36.4 kg/m2 (Meservey et al.4) to a median of 25.8 kg/m2 (Cavalot et al.2) and age (from the mean of 60.5 years in Wilson et al. 5 to median age of 70 years in Domardzki et al.63). All studies have shown high rates of death (1-year mortality of roughly 30% in Wilson et al.5, 25% in Vonderbank et al.3) and re-presentation to the hospital (23% were readmitted within 30 days, usually for recurrent hypercapnic respiratory failure4; 66% within one year2).

The unreliability of diagnostic codes is a significant challenge for this literature because many respiratory conditions are not diagnosed, and many are misdiagnosed, particularly in obese patients64-66. This makes it challenging to disentangle the influence of these conditions on each other, the rates of (mis)diagnosis, and the likelihood of hypercapnia67. In addition, the definition of OHS – hypercapnic respiratory failure occurring in the context of sleep-disordered breathing and in the absence of other contributing conditions26 – is particularly challenging to apply in health record-based epidemiologic research because OHS is under-recognized8,66 and one cannot infer which contributing conditions have been considered and excluded, particularly in the presence of missing data.

Despite these limitations, several patterns emerge. First, hypercapnia is common in acute care settings, is associated with substantial morbidity, and often occurs in the context of multiple potentially contributing diagnoses, including OSA. Data on the excess rate of OSA among patients with hypercapnia are conflicting and vary substantially based on the method used for ascertaining OSA.

Outpatients

Determining the contribution of sleep-disordered breathing to outpatient hypercapnic respiratory failure is challenging because neither elevated arterial CO2 levels nor sleep breathing abnormalities are reliably assessed in the outpatient population. One approach to investigating the community-dwelling population with hypercapnic respiratory failure is to evaluate the proportion of patients receiving home NIV. However, only a subset of patients receiving home NIV have hypercapnic respiratory failure, given that NIV is started before overt respiratory failure for conditions such as neuromuscular disease. Conversely, not all patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure qualify for, or obtain, home NIV.

Twenty-two identified studies evaluated the composition of patients enrolled in home mechanical ventilation programs and commented on OSA or the prevalence of related comorbidities (Table 3). The estimated population prevalence of hypercapnia presenting to the hospital by Chung and colleagues (163 per 100,000)1 is between 3-100 times higher than estimates of the prevalence of patients in domiciliary home ventilation programs (1-47 per 100,00068). It is reported that 25-50% of patients in home mechanical ventilation programs are enrolled after a hospitalization for acute (on chronic) respiratory failure69-72.

Table 3:

Constitution of Home Non-Invasive Ventilation Programs

| Author | Location Year |

Enrollment Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Method of Assessment |

Most Common Cause |

Prevalence of OSA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohorts on Home NIV; Polysomnography Performed | ||||||

| Poh Tan et al. (a)74 | AUS, 2005-2010 | Records review of a clinic, sole provider of services to their region. | Home mechanical or non-invasive prescribed | Routine PSG performed at NIV initiation. | NMD | 15% 240 with OHS as reason for Vent; but OSA present in most patients of all other classifications. |

| Patout et al73 | UK and France, 2008-2014 | Established via inpatient study at 2 centers (London and Rouen | CPAP, ASV, tracheostomy | Patients received inpatient titration studies at initiation | OHS | 29.5% of 1746 with OHS. 12.7% with Overlap Syndrome. 10.5% with OSA (non-OHS) listed as a cause. |

| Cohorts on Home NIV; provider determination of cause or survey | ||||||

| Cantero et al.70 | 2016-2018, Switzerland | Receipt of Home NIV – which generally though not always requires hypercapnia. (all regional providers) | Adaptive servo ventilation, tracheostomy | Clinical determination of pulmonologist | COPD | 26% OHS 11% COPD-Overlap 4% with OSA as part of ‘other’ SDB |

| Budweiser et al99 | 2002-2004 Germany | Home NIV for 3 or more months (single center) | None reported | Clinician diagnosis | COPD | 30% of 231 with OHS or OVS |

| Neill et al76, also Garner et al100 | 2018 New Zealand | Receipt of Home NIV (country-wide) | None reported | Clinician diagnosis | OHS | 47.3% of 1188 with OHS additional 23% with Overlap Syndrome |

| Hannan101 et al. (a) | 2013, Australia | Provision of Home NIV | Non-English speaking, survey nonresponse (43.4%) | Patient self-report | NMD | 31% with OHS |

| Hannan101 et al. (b) | 2013, Canada | Provision of Home NIV | Non-English speaking, survey nonresponse (43.4%) | Patient self-report | NMD | 8.1% with OHS |

| Rose et al102. | Canada, 2012-2013 | Ventilation provision (Service providers identified prescribers, then surveyed) | None | Provider determination | NMD | 14% with OHS |

| Maquillon et al103 | Chile, 2008-2017 | Admission for inpatient initiation of NIV (Nationwide) | Smoking, drug use, lack of power or resources at home. | Provider determination | COPD | 23.9% with OHS |

| Schwarz et al104 | UK, 2008-2018 | Death while enrolled in a large weaning and HMV service; PaCO2 > 45 mmHg | Still alive (roughly half of enrolled patients) | Provider determination | NMD | 17% with OHS 4% with Overlap Syndrome |

| Lloyd-Owen et al.68 | 16 European countries, 2002 | Survey estimates of NIV or IMV for 3+ months delivered at home. | Negative pressure vent., phrenic stim., positional therapies. | Provider determination. | COPD | <31% OHS (lumped with “chest wall restriction”) |

| Laub and Midgren71 | Sweden, 1995-2005 | National register of patient receiving Home Ventilation | None | Diagnosis provided to register | OHS | 28% of 422 OHS |

| Nasilowsky et al105 | Poland, 2000-2010 | Treated at an Experienced HMV program | None | Provider determination; survey | NMD | 11% with hypoventilation syndromes* |

| Valko et al106 | Hungary, 2018 | Survey to centers providing HMV | None | Provider determination; survey | OHS | 60% with hypoventilation syndromes* |

| Windisch et al107 | Germany, prior to 2003 | 4 hospitals, established in HMV clinic | First visit with HMV clinic, acute decompensation, tracheostomy | Provider determination | COPD | 5.3% OHS of 226 |

| Biggelaar et al.108 | Netherlands 1991-2020 | 4 centers that provision home NIV | None | Diagnosis provided to register | NMD | ~15% ‘Sleep Disorders’ indication. |

| Cohorts on Home NIV; Documentation of Comorbidity present | ||||||

| Jimenez, Akrivo, et al.109 | Mich. USA, 2012-2021 | PaCO2/PtCO2 45+mmHg and pH over 7.35; | Tracheostomy, not on NIV at first visit. | Diagnostic Codes | NMD | 14% of 48 OHS |

| Povitz et al72 | Canada 2000-2012. | Request for NIV or IMV equipment from provincial administrative data | Private acquisition of supplies; long-term care facility residents | Diagnostic codes; | NMD | 15.9% ‘Obesity’ (OSA and OHS not directly assessed) |

| Borel et al. 69 | France 2003-2008 | Initiation of NIV at one of five facilities; obesity is the main explanation of NIV. | Neuromuscular disorder, severe pulmonary fibrosis, FEV1/VC < 30% | Chart review | OHS | 67% of 107 OHS |

| Tissot et al.110 | France 2009-2014 | Referral for NIV (3 hospitals) | Death or loss to follow-up within 6 months | Patient survey | OHS | 42% of 264 OHS |

| Poh Tan et al. (b)111 | Singapore, 2009-2015 | Single center HMV service | None | Chart Review | NMD (ALS) | 2% of 112 with OSA listed as contributor |

| Rentala et al.112 | Finland, 2012-2015 | Referral for home NIV | None | Chart Review | OHS | 47.3% OHS 57.1% OSA as contributor |

Includes obesity hypoventilation, congenital central hypoventilation syndrome, and central apneas.

PtCO2: Transcutaneous Partial Pressure of CO2. HMV: home mechanical ventilation. SDB: Sleep Disordered Breathing

Mirroring the ICU and inpatient literature, studies with universal assessment of sleep breathing when home NIV is initiated generally show that most patients have OSA73,74, while studies relying on clinician documentation of the “primary cause” of hypercapnia result in much lower estimates. Several cohorts listed NMD, COPD, and OHS as the most common indications for non-invasive ventilation.

Longitudinal studies report an overall increase in the prevalence of patients receiving home mechanical ventilation over the past several decades and also an increase in the proportion of those patients who have obesity hypoventilation syndrome70,75,76. Demographic and comorbidity data suggest that OSA likely contributes to many more patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure than is documented. For example, the patients who are labeled as having “COPD” as their primary cause for mechanical ventilation in these cohorts tend to have much higher BMI (generally, above 30 kg/m2) and less severe airflow limitation on spirometry obstruction, as compared to the cohorts when OSA was excluded, e.g., the trial by Kohnlein et al. and analyses of the NETT trial, where mean BMI 24-25 kg/m2 34,77,78. This pattern would be expected if many of these patients have an overlap syndrome, which results in hypercapnia at milder obstruction79.

Even among patients with neuromuscular disease, sleep apnea may contribute to the earlier occurrence of respiratory failure. Boentert et al.41 showed that OSA was present in 45.6% of patients with ALS before they developed an indication for NIV, and patients with OSA had 1.9 times higher odds of having nocturnal hypoventilation, which is known to predict the subsequent development of daytime hypoventilation23. Duchenne muscular dystrophy is another condition where OSA is highly prevalent early in the course of the disease but progresses to nocturnal hypoventilation and ultimately hypercapnic respiratory failure80,81. Lastly, extremely high rates of sleep-disordered breathing (above 60%82) and nocturnal hypoventilation (30%83,84) are seen in patients with spinal cord injuries, where PAP treatment has been shown to improve respiratory events and autonomic symptoms85. While the complex respiratory control abnormalities86 and simultaneous onset SDB and muscle weakness hamper the ability to isolate the contribution of OSA, both the epidemiologic and physiologic evidence support the role of OSA in accelerating the development of hypercapnia in patients with spinal cord injury. However, under recognition of SDB likely results from challenges accessing traditional sleep lab testing due to complex care needs of patients with neuromuscular disease87. Innovative management pathways may facilitate early recognition of patients with nocturnal hypoventilation88, who are difficult to identify with clinical criteria83 and have been shown to benefit from NIV in randomized trials89.

In summary, though significant limitations exist with applying the data from home-mechanical ventilation to the question of OSA’s contribution to hypercapnia in outpatients, the available data suggests that OSA is frequently present in patients that providers have not labeled as having OHS as their primary indication. Furthermore, both the prevalence of domiciliary ventilation and the diagnosis of OHS are increasing, likely as a result of the increasing prevalence of obesity90.

Summary

A burgeoning literature describing the epidemiology of hypercapnic respiratory failure has developed over the last two decades. Sleep apnea is prevalent among patients recognized to have hypercapnia in a variety of settings but is often not diagnosed. Both physiologic understanding and epidemiologic evidence support that OSA is a contributing cause in many cases, though better ascertainment of potentially contributing conditions would improve the strength of evidence. Additionally, hypercapnic respiratory failure is common (167 per 100,000 persons in Chung et al.1, which is roughly as common as decompensated cirrhosis91), occurs in patients with multiple morbidities92, and is associated with high healthcare expenditure93, morbidity, and mortality. As sleep apnea is treatable and likely contributes to the occurrence of hypercapnic respiratory failure with consequent increases in healthcare burden, determining the exact contribution of OSA and the effectiveness of improved identification or management of OSA in this population should be a public health priority.

Key Points:

The diagnostic evaluation of patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure has typically focused on finding a single cause for the hypercapnia, but many patients have multiple contributing conditions.

The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure is poorly recognized. Over two-thirds of patients with hypercapnia in acute settings have underlying OSA if tested, but only 10-25% are diagnosed in routine clinical care.

While the importance of OSA in obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) is well-established, its role in contributing to hypercapnia is under-investigated. Addressing this knowledge gap is crucial because sleep apnea is treatable, and hypercapnic respiratory failure is common and associated with substantial morbidity and mortality.

Epidemiologic research on hypercapnic respiratory failure faces several challenges, including inaccuracy of health record-based comorbidity assessment, substantial follow-up loss between inpatient and outpatient settings, and oversimplified attribution of the cause of respiratory failure.

Clinics Care Points.

Hypercapnic respiratory failure is common, becoming more prevalent, and sleep apnea contributes to its development.

Sleep apnea is found in most patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure if sleep testing is sought, even though far fewer are recognized to have OSA.

Patients who have OSA and other causes of hypercapnia tend to develop hypercapnia at a milder stage of the disease, suggesting OSA contributes to its occurrence.

While the current documentation requirements and the existing evidence base encourage categorizing patients as having a single cause, recognizing that many patients with hypercapnic respiratory failure have multiple contributing comorbidities may allow more patients to receive beneficial treatments.

Significant loss to follow-up is seen in all studies when patients identified in acute settings are recommended to return for sleep testing after discharge, suggesting that approaches to encourage higher follow-up rates or more immediate testing are needed for clinical care and research.

Disclosures:

B.W.L. receives research funding from the American Thoracic Society ASPIRE Fellowship and the National Institutes of Health under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award 5T32HL105321

J.P.B. no conflicts of interest.

K.M.S. Sundar is co-founder of Hypnoscure LLC—a software application for population management of sleep apnea through the University of Utah Technology Commercialization Office.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Brian W. Locke, Division of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Occupational Pulmonary Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Jeanette P. Brown, Division of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Occupational Pulmonary Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Krishna M. Sundar, Division of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Occupational Pulmonary Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, Utah.

References:

- 1.Chung Y, Garden FL, Marks GB, Vedam H. Population Prevalence of Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure from Any Cause. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(8):966–967. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202108-1912LE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cavalot G, Dounaevskaia V, Vieira F, et al. One-Year Readmission Following Undifferentiated Acute Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure. COPD J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2021;18(6):602–611. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2021.1990240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vonderbank S, Gibis N, Schulz A, et al. Hypercapnia at Hospital Admission as a Predictor of Mortality. Open Access Emerg Med OAEM. 2020;12:173–180. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S242075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meservey AJ, Burton MC, Priest J, Teneback CC, Dixon AE. Risk of Readmission and Mortality Following Hospitalization with Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure. Lung. 2020;198(1):121–134. doi: 10.1007/s00408-019-00300-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson MW, Labaki WW, Choi PJ. Mortality and Healthcare Utilization of Patients with Compensated Hypercapnia. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(12):2027–2032. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202009-1197OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis GM. “Hypercapnia” versus “Hypercarbia.”. Anesthesiology. 1961;22(2):324–324. doi: 10.1097/00000542-196103000-00030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapitan KS. Ventilatory failure. Can you sustain what you need? Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(4):396–399. doi: 10.1513/annalsats.201305-132ot [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nowbar S, Burkart KM, Gonzales R, et al. Obesity-associated hypoventilation in hospitalized patients: prevalence, effects, and outcome. Am J Med. 2004;116(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Randerath W, Ahmed S BaHammam, BaHammam AS. Overlooking Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome: The Need for Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome Staging and Risk Stratification. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(10):1211–1212. doi: 10.1513/annalsats.202006-683ed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan V. Holding our breath: Exploring the causes of hypercapnic respiratory failure resulting in mortality. Respirology. 2023;28(2):97–98. doi: 10.1111/resp.14413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kryger MH. Sleep Apnea: From the Needles of Dionysius to Continuous Positive Airway Pressure. JAMA Intern Med. 1983;143(12):2301–2303. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1983.00350120095020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger KI, Rapoport DM, Ayappa I, Goldring RM. Pathophysiology of Hypoventilation During Sleep. Sleep Med Clin. 2014;9(3):289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2014.05.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piper AJ, Yee BJ. Hypoventilation syndromes. Compr Physiol. 2014;4(4):1639–1676. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guyenet PG, Bayliss DA. Neural Control of Breathing and CO2 Homeostasis. Neuron. 2015;87(5):946–961. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCartney A, Phillips D, James M, et al. Ventilatory neural drive in chronically hypercapnic patients with COPD: effects of sleep and nocturnal noninvasive ventilation. Eur Respir Rev. 2022;31(165):220069. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0069-2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hegewald MJ Impact of obesity on pulmonary function: current understanding and knowledge gaps. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;27(2):132–140. doi: 10.1097/mcp.0000000000000754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owens RL, Malhotra A, Eckert DJ, White DP, Amy S Jordan, Jordan AS. The influence of end-expiratory lung volume on measurements of pharyngeal collapsibility. J ApplPhysiol. 2010;108(2):445–451. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00755.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stradling J, Chadwick GA, Chadwick GA, Frew AJ, Frew AJ. Changes in ventilation and its components in normal subjects during sleep. Thorax. 1985;40(5):364–370. doi: 10.1136/thx.40.5.364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin CK, Lin CC, Lin CC. Work of breathing and respiratory drive in obesity. Respirology. 2012;17(3):402–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02124.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robin ED, Whaley RD, Crump CH, Travis DM. Alveolar Gas Tensions, Pulmonary Ventilation, and Blood pH During Physiologic Sleep In Normal Subjects. Surv Anesthesiol. 1959;3(2). doi: 10.1097/00132586-195904000-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Troester M, Quan S, Berry R, Plante D, Abreu A, Alzoubaidi M. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Version 3. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hillman DR, Singh B, McArdle N, Eastwood PR. Relationships between ventilatory impairment, sleep hypoventilation and type 2 respiratory failure. Respirol Carlton Vic. 2014;19(8):1106–1116. doi: 10.1111/resp.12376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orlikowski D, Prigent H, Quera Salva MA, et al. Prognostic value of nocturnal hypoventilation in neuromuscular patients. Neuromuscul Disord. 2017;27(4):326–330. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2016.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berger KI, Ayappa I, Sorkin IB, Norman RG, Rapoport DM, Goldring RM. CO(2) homeostasis during periodic breathing in obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol Bethesda Md 1985. 2000;88(1):257–264. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.1.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masa JF, Mokhlesi B, Iván Benítez, et al. Long-term clinical effectiveness of continuous positive airway pressure therapy versus non-invasive ventilation therapy in patients with obesity hypoventilation syndrome: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2019;393(10182):1721–1732. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32978-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mokhlesi B, Masa JF, Brozek JL, et al. Evaluation and Management of Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(3):e6–e24. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201905-1071ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Masa JF, Corral J, Caballero C, et al. Non-invasive ventilation in obesity hypoventilation syndrome without severe obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax. 2016;71(10):899. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng Y, Yee BJ, Wong K, Grunstein RR, Piper AJ. A pilot randomized trial comparing CPAP versus bilevel PAP spontaneous mode in the treatment of hypoventilation disorder in patients with obesity and obstructive airway disease. J Clin Sleep Med JCSM Off Publ Am Acad Sleep Med. 2021;18(1):99–107. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borel JC, Pépin JL, Pison C, et al. Long-term adherence with non-invasive ventilation improves prognosis in obese COPD patients. Respirology. 2014;19(6):857–865. doi: 10.1111/resp.12327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nowalk NC, Neborak JM, Mokhlesi B. Is bilevel PAP more effective than CPAP in treating hypercapnic obese patients with COPD and severe OSA? J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18(1):5–7. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pepin JL, Timsit JF, Tamisier R, et al. Prevention and care of respiratory failure in obese patients. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(5):407–418. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(16)00054-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaw R, Bhateja P, y Mar HP, et al. Postoperative complications in patients with unrecognized obesity hypoventilation syndrome undergoing elective noncardiac surgery. Chest. 2016;149(1):84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Channick JE, Jackson NJ, Zeidler MR, Buhr RG. Effects of obstructive sleep apnea and obesity on 30-day readmissions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional mediation analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022;19(3):462–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mathews AM, Nicholas G. Wysham, Wysham NG, et al. Hypercapnia in Advanced Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Secondary Analysis of the National Emphysema Treatment Trial. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis J COPD Found. 2020;7(4):336–345. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.7.4.2020.0176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mokhlesi B, Tulaimat A, Faibussowitsch I, Wang Y, Evans AT, Arthur T. Evans. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: prevalence and predictors in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2007;11(2):117–124. doi: 10.1007/s11325-006-0092-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran K, Wang L, Gharaibeh S, et al. Elucidating Predictors of Obesity Hypoventilation Syndrome in a Large Bariatric Surgery Cohort. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020;17(10):1279–1288. doi: 10.1513/annalsats.202002-135oc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaw R, Hernandez AV, Walker E, Aboussouan L, Mokhlesi B. Determinants of hypercapnia in obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review and metaanalysis of cohort studies. Chest. 2009;136(3):787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Branthwaite MA. Cardiorespiratory consequences of unfused idiopathic scoliosis. Br J Dis Chest. 1986;80:360–369. doi: 10.1016/0007-0971(86)90089-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sawicka EH, Branthwaite MA Respiration during sleep in kyphoscoliosis. Thorax. 1987;42(10):801. doi: 10.1136/thx.42.10.801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tilanus TBM, Groothuis JT, TenBroek-Pastoor JMC, et al. The predictive value of respiratory function tests for non-invasive ventilation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Respir Res. 2017;18(1):144–144. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0624-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boentert M, Glatz C, Helmle C, Okegwo A, Young P, Young P. Prevalence of sleep apnoea and capnographic detection of nocturnal hypoventilation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89(4):418–424. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-316515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Llewelyn H, Ang HA, Lewis K, Al-Abdullah A. Making the diagnostic process evidence-based. In: Llewelyn H, Ang HA, Lewis K, Al-Abdullah A, eds. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Diagnosis. Oxford University Press; 2014:0. doi: 10.1093/med/9780199679867.003.0013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fienberg SE. When did Bayesian inference become" Bayesian"? Bayesian Anal. 2006;1(1):1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gay PC, Owens RL, Wolfe LF, et al. Executive Summary: Optimal NIV Medicare Access Promotion: A Technical Expert Panel Report From the American College of Chest Physicians, the American Association for Respiratory Care, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, and the American Thoracic Society. Chest. 2021;160(5):1808–1821. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki E, Yamamoto E, Tsuda T. On the Relations Between Excess Fraction, Attributable Fraction, and Etiologic Fraction. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(6):567–575. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pearl J. Probabilities of causation: three counterfactual interpretations and their identification. In: Probabilistic and Causal Inference: The Works of Judea Pearl. ; 2022:317–372. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chung Y, Garden FL, Marks GB, Vedam H Causes of hypercapnic respiratory failure: a population-based case-control study. BMC Pulm Med. Published online 2023. doi: 10.1186/s12890-023-02639-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Contou D, Fragnoli C, Córdoba-Izquierdo A, et al. Noninvasive ventilation for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure: intubation rate in an experienced unit. Respir Care. 2013;58(12):2045–2052. doi: 10.4187/respcare.02456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ouanes-Besbes L, Hammouda Z, Besbes S, et al. Diagnosis of Sleep Apnea Syndrome in the Intensive Care Unit: A Case Series of Survivors of Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18(4):727–729. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202005-425RL [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thille AW, Córdoba-Izquierdo A, Maitre B, Boyer L, Brochard L, Drouot X. High prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome in patients admitted to ICU for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure: a preliminary study. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(2):267–269. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4998-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Adler D, Pépin JL, Dupuis-Lozeron E, et al. Comorbidities and Subgroups of Patients Surviving Severe Acute Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure in the Intensive Care Unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(2):200–207. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201608-16660C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gursel G, Zerman A, Aydogdu M, et al. Diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea with respiratory polygraph in hypercapnic ICU patients. Crit Care. 2015;19:1–201.25560635 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adler D, Dupuis-Lozeron E, Janssens JP, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea in patients surviving acute hypercapnic respiratory failure is best predicted by static hyperinflation. PloS One. 2018;13(10):e0205669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bucklin AA, Ganglberger W, Quadri SA, et al. High prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in the intensive care unit — a cross-sectional study. Sleep Breath. Published online August 16, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s11325-022-02698-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Resta O, Barbaro MPF, Brindicci C, Nocerino MC, Caratozzolo G, Carbonara M. Hypercapnia in overlap syndrome: possible determinant factors. Sleep Breath Schlaf Atm. 2002;6(1):11–17. doi: 10.1007/s11325-002-0011-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chung Y, Garden FL, Marks GB, Hima Vedam. Causes of hypercapnic respiratory failure and associated in-hospital mortality. Respirology. Published online October 9, 2022. doi: 10.1111/resp.14388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sharma SK, Stansbury R. How we do it: Sleep Disordered Breathing in Hospitalized patients - A game Changer? Chest. Published online October 18, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharma SK. Hospital sleep medicine: the elephant in the room? J Clin Sleep Med JCSM Off Publ Am Acad Sleep Med. 2014;10(10):1067–1068. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharma S, Mukhtar U, Kelly C, Mather PJ, Quan SF. Recognition and Treatment of Sleep-Disordered Breathing in Obese Hospitalized Patients May Improve Survival. The HoSMed Database. Am J Med. 2017;130(10):1184–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.03.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suen C, Wong J, Ryan CM, et al. Prevalence of Undiagnosed Obstructive Sleep Apnea Among Patients Hospitalized for Cardiovascular Disease and Associated In-Hospital Outcomes: A Scoping Review. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):989. doi: 10.3390/jcm9040989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson KG, Rastegar V, Scuderi N, Johnson DC, Visintainer P PAP therapy and readmission rates after in-hospital laboratory titration polysomnography in patients with hypoventilation. J Clin Sleep Med. 18(7):1739–1748. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bülbül Y, Ayik S, Ozlu T, Orem A. Frequency and predictors of obesity hypoventilation in hospitalized patients at a tertiary health care institution. Ann Thorac Med. 2014;9(2):87–91. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.128851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Domaradzki L, Gosala S, Iskandarani K, Van de Louw A. Is venous blood gas performed in the Emergency Department predictive of outcome during acute on chronic hypercarbic respiratory failure? Clin Respir J. 2018;12(5):1849–1857. doi: 10.1111/crj.12746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Collins BF, Collins BF, Ramenofsky DH, et al. The Association of Weight With the Detection of Airflow Obstruction and Inhaled Treatment Among Patients With a Clinical Diagnosis of COPD. Chest. 2014;146(6):1513–1520. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scott S, Currie J, Albert P, Calverley PMA, Wilding JPH. Risk of Misdiagnosis, Health-Related Quality of Life, and BMI in Patients Who Are Overweight With Doctor-Diagnosed Asthma. Chest. 2012;141(3):616–624. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marik PE, Chen C. The clinical characteristics and hospital and post-hospital survival of patients with the obesity hypoventilation syndrome: analysis of a large cohort. Obes Sci Pract. 2016;2(1):40–47. doi: 10.1002/osp4.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Manuel DG, Rosella LC, Stukel TA. Importance of accurately identifying disease in studies using electronic health records. BMJ. 2010;341:c4226. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lloyd-Owen SJ, Donaldson GC, Ambrosino N, et al. Patterns of home mechanical ventilation use in Europe: results from the Eurovent survey. Eur Respir J. 2005;25(6):1025–1031. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00066704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Borel JC, Burel B, Tamisier R, et al. Comorbidities and mortality in hypercapnic obese under domiciliary noninvasive ventilation. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(1):e52006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cantero C, Adler D, Pasquina P, et al. Long-Term Noninvasive Ventilation in the Geneva Lake Area: Indications, Prevalence, and Modalities. Chest. 2020;158(1):279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.02.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laub M, Midgren B. Survival of patients on home mechanical ventilation: a nationwide prospective study. Respir Med. 2007;101(6):1074–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Povitz M, Rose L, Shariff SZ, et al. Home Mechanical Ventilation: A 12-Year Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Respir Care. 2017;63(4):380–387. doi: 10.4187/respcare.05689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patout M, Lhuillier E, Kaltsakas G, et al. Long-term survival following initiation of home non-invasive ventilation: a European study. Thorax. 2020;75(11):965–973. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2019-214204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tan GP, Tan GP, McArdle N, et al. Patterns of use, survival and prognostic factors in patients receiving home mechanical ventilation in Western Australia: A single centre historical cohort study. Chron Respir Dis. 2018;15(4):356–364. doi: 10.1177/1479972318755723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Escarrabill J, Tebé C, Mireia Espallargues, et al. Variabilidad en la prescripción de la ventilación mecánica a domicilio. Arch Bronconeumol. 2015;51(10):490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2014.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Neill AM, Tristram R Ingham, Meredith Perry, Daniel Aldridge, James Miller, Bernadette Jones. Noninvasive ventilation in New Zealand: a national prevalence survey. Intern Med J. Published online November 3, 2022. doi: 10.1111/imj.15960 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wijkstra PJ, Duiverman ML. Home Mechanical Ventilation: A Fast-Growing Treatment Option in Chronic Respiratory Failure. Chest. 2020;158(1):26–27. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Köhnlein T, Windisch W, Windisch W, et al. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for the treatment of severe stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective, multicentre, randomised, controlled clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(9):698–705. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(14)70153-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Verbraecken J, McNicholas WT. Respiratory mechanics and ventilatory control in overlap syndrome and obesity hypoventilation. Respir Res. 2013;14(1):132–132. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hoque R. Sleep-disordered breathing in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: an assessment of the literature. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(6):905–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li L, Umbach DM, Li Y, et al. Sleep apnoea and hypoventilation in patients with five major types of muscular dystrophy. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2023;10(1):e001506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chiodo A, Sitrin RG, Kristy A. Bauman, Bauman KA. Sleep disordered breathing in spinal cord injury: A systematic review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39(4):374–382. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2015.1126449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Graco M, Ruehland W, Schembri R, et al. Prevalence of central sleep apnoea in people with tetraplegic spinal cord injury: a retrospective analysis of research and clinical data. Sleep. Published online September 11, 2023. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsad235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bauman Kristy A., Bauman KA, Kurili A, et al. Simplified Approach to Diagnosing Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Nocturnal Hypercapnia in Individuals With Spinal Cord Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97(3):363–371. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brown JP, Kristy A. Bauman, Bauman KA, et al. Positive airway pressure therapy for sleep-disordered breathing confers short-term benefits to patients with spinal cord injury despite widely ranging patterns of use. Spinal Cord. 2018;56(8):777–789. doi: 10.1038/s41393-018-0077-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sankari A, Vaughan S, Bascom AT, Martin JL, Badr MS. Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Spinal Cord Injury: A State-of-the-Art Review. Chest. 2019;155(2):438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wolfe LF, Benditt JO, Aboussouan L, et al. Optimal NIV Medicare access promotion: patients with thoracic restrictive disorders: a technical expert panel report from the American College of chest physicians, the American association for respiratory care, the American Academy of sleep medicine, and the American thoracic Society. Chest. 2021;160(5):e399–e408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Graco M, Gobets David F, O’Connell C, et al. Management of sleep-disordered breathing in three spinal cord injury rehabilitation centres around the world: a mixed-methods study. Spinal Cord. 2022;60(5):414–421. doi: 10.1038/s41393-022-00780-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ward S, Chatwin M, Heather S, Simonds A. Randomised controlled trial of non-invasive ventilation (NIV) for nocturnal hypoventilation in neuromuscular and chest wall disease patients with daytime normocapnia. Thorax. 2005;60(12):1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Finkelstein EA, Khavjou O, Thompson HF, et al. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(6):563–570. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sepanlou SG, Sepanlou SG, Safiri S, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017 : a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(3):245–266. doi: 10.1016/s2468-1253(19)30349-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Adler D, Cavalot G, Brochard L Comorbidities and Readmissions in Survivors of Acute Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41(06):806–816. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1710074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Toussaint M, Wijkstra PJ, McKim D, et al. Building a home ventilation programme: population, equipment, delivery and cost. Thorax. 2022;77(11):1140–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Berger KI, Ayappa I, Sorkin IB, Norman RG, Rapoport DM, Goldring RM. CO2 homeostasis during periodic breathing in obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88(1):257–264. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.1.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Larsson J, Gustafsson P. A case study in fitting area-proportional euler diagrams with ellipses using eulerr. In: ; 2018:84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fox BD, Bondarenco M, Shpirer I, Natif N, Perl S Transitioning from hospital to home with non-invasive ventilation: who benefits? Results of a cohort study. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2022;9(1):e001267. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2022-001267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Segrelles Calvo G, Zamora García E, Girón Moreno R, et al. Non-invasive Ventilation in an Elderly Population Admitted to a Respiratory Monitoring Unit: Causes, Complications and One-year Evolution. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;48(10):349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.arbr.2012.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Brandão ME, Conde B, Silva JC, Reis R, Afonso A. Non-invasive ventilation in the treatment of acute and chronic exacerbated respiratory failure: What to expect outside the critical care units? Rev Port Pneumol Engl Ed. 2016;22(1):54–56. doi: 10.1016/j.rppnen.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Budweiser S, Hitzl AP, Jörres RA, et al. Health-related quality of life and long-term prognosis in chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure: a prospective survival analysis. Respir Res. 2007;8(1):92–92. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Garner DJ, Berlowitz DJ, Douglas J, et al. Home mechanical ventilation in Australia and New Zealand. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(1):39–45. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00206311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hannan LM, Sahi H, Road J, McDonald CF, Berlowitz DJ, Howard ME. Care Practices and Health-related Quality of Life for Individuals Receiving Assisted Ventilation. A Cross-National Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(6):894–903. doi: 10.1513/annalsats.201509-590oc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rose L, McKim DA, Katz SL, et al. Home mechanical ventilation in Canada: a national survey. Respir Care. 2015;60(5):695–704. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Maquilon C, Antolini M, Valdés N, et al. Results of the home mechanical ventilation national program among adults in Chile between 2008 and 2017. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):394. doi: 10.1186/s12890-021-01764-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schwarz EI, Mike Mackie, Mackie M, et al. Time-to-death in chronic respiratory failure on home mechanical ventilation: A cohort study. Respir Med. 2020;162:105877. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nasiłowski J, Wachulski M, Trznadel W, et al. The evolution of home mechanical ventilation in poland between 2000 and 2010. Respir Care. 2015;60(4):577–585. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Valkó L, Baglyas S, Gál J, Lorx A. National survey: current prevalence and characteristics of home mechanical ventilation in Hungary. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18(1):190–190. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0754-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Windisch W, Freidel K, Schucher B, et al. The Severe Respiratory Insufficiency (SRI) Questionnaire: a specific measure of health-related quality of life in patients receiving home mechanical ventilation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(8):752–759. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00088-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.van den Biggelaar RJM, Hazenberg A, Cobben NAM, Gommers DAMPJ, Gaytant MA, Wijkstra PJ. Home mechanical ventilation: the Dutch approach. Pulmonology. 2022;28(2):99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2021.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jimenez JV, Ackrivo J, Hsu JY, et al. Lowering PCO2 with Non-invasive Ventilation is Associated with Improved Survival in Chronic Hypercapnic Respiratory Failure. Respir Care. Published online May 3, 2023:respcare.10813. doi: 10.4187/respcare.10813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tissot A, Jaffre S, Sandrine Jaffre, et al. Home Non-Invasive Ventilation Fails to Improve Quality of Life in the Elderly: Results from a Multicenter Cohort Study. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0141156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tan GP, Soon LHY, Ni B, et al. The pattern of use and survival outcomes of a dedicated adult Home Ventilation and Respiratory Support Service in Singapore: a 7-year retrospective observational cohort study. J Thorac Dis Vol 11 No 3 March 29 2019. J Thorac Dis. Published online 2019. Accessed January 2, 2019. https://jtd.amegroups.org/article/view/27412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rantala HA, Leivo-Korpela S, Kettunen S, Lehto JT, Lehtimäki L. Survival and end-of-life aspects among subjects on long-term noninvasive ventilation. Eur Clin Respir J. 2021;8(1):1840494. doi: 10.1080/20018525.2020.1840494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]