Keywords: cerebral palsy, dysarthria, dysphagia, electromyography, swallowing

Abstract

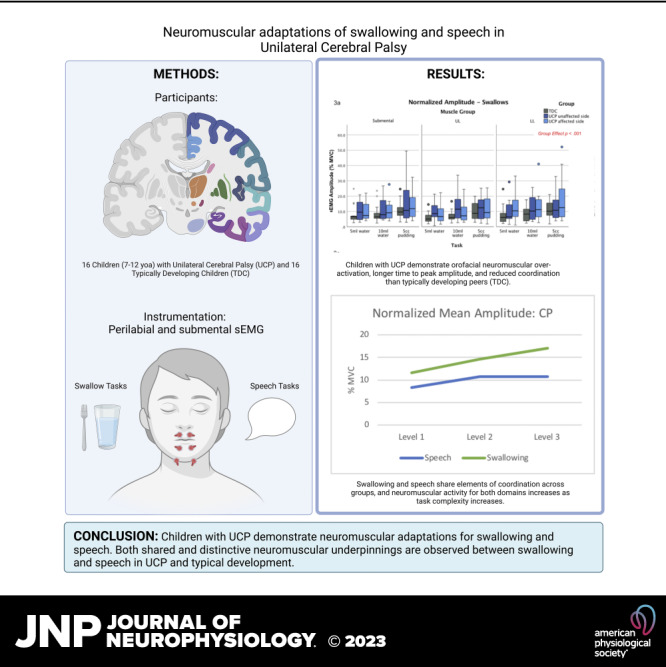

Our aims were to 1) examine the neuromuscular control of swallowing and speech in children with unilateral cerebral palsy (UCP) compared with typically developing children (TDC), 2) determine shared and separate neuromuscular underpinnings of the two functions, and 3) explore the relationship between this control and behavioral outcomes in UCP. Surface electromyography (sEMG) was used to record muscle activity from the submental and superior and inferior orbicularis oris muscles during standardized swallowing and speech tasks. The variables examined were normalized mean amplitude, time to peak amplitude, and bilateral synchrony. Swallowing and speech were evaluated using standard clinical measures. Sixteen children with UCP and 16 TDC participated (7–12 yr). Children with UCP demonstrated higher normalized mean amplitude and longer time to peak amplitude across tasks than TDC (P < 0.01; and P < 0.02) and decreased bilateral synchrony than TDC for swallows (P < 0.01). Both shared and distinctive neuromuscular patterns were observed between swallowing and speech. In UCP, higher upper lip amplitude during swallows was associated with shorter normalized mealtime durations, whereas higher submental bilateral synchrony was related to longer mealtime durations. Children with UCP demonstrate neuromuscular adaptations for swallowing and speech, which should be further evaluated for potential treatment targets. Furthermore, both shared and distinctive neuromuscular underpinnings between the two functions are documented.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Systematically studying the swallowing and speech of children with UCP is new and noteworthy. We found that they demonstrate neuromuscular adaptations for swallowing and speech compared with typically developing peers. We examined swallowing and speech using carefully designed tasks, similar in motor complexity, which allowed us to directly compare patterns. We found shared and distinctive neuromuscular patterns between swallowing and speech.

INTRODUCTION

Swallowing and Speech in Cerebral Palsy

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a group of disorders caused by nonprogressive abnormalities in the developing brain, which frequently result in difficulties in movement and muscle tone, in addition to limitations across other body systems (1). Two frequently occurring disorders in children with CP include swallowing and speech disorders (known as dysphagia and dysarthria, respectively). Swallowing disorders in this population may be characterized by variable deficits, ranging from reductions in postural support and feeding independence, difficulties in orientation, reception, and containment of food and drink in the oral cavity, to difficulties in the efficiency and safety of the pharyngeal phase (2–6). Critically, without proper treatment, these issues can lead to reductions in growth, respiratory health, gastrointestinal function, and quality of life for children with CP (7–9). Dysarthria is a motor speech disorder, frequently resulting in reduced intelligibility (10, 11) that can affect a child’s ability to communicate and has been associated with poor academic performance, impacted interpersonal relationships, and reduced employment potential in adulthood (12–14). Importantly, dysphagia and dysarthria can co-occur (15–18), resulting in even more substantial challenges for individuals with CP.

Swallowing and speech share many anatomical and physiological substrates within the head and neck, muscles, cranial nerves, central pattern generator circuitry (19–21), and even higher brain control (22–27). Although these underpinnings have been described in healthy populations for each domain (swallowing and speech) (22–25, 27), much less is known about how they may adapt or reorganize in the face of a neural lesion manifesting as CP and about potential cross-system interactions between these two systems. Better understanding of this adaptation and reorganization and the potential cross-system interactions between swallowing and speech in CP could provide critical insights for improvements in efficient and effective interventions that may influence both of these domains. Currently, most treatments for dysphagia and dysarthria for children with CP remain symptom-based or compensatory in nature [e.g., modification of food consistency, positioning, and oral motor interventions, (e.g., Refs. 28–32)]. Although these treatments may provide short-term relief or symptom management, they have limited efficacy in resolving underlying physiological deficits (33–36), which impacts long-term outcomes. As a result, children with CP may receive swallow and speech therapy for years and yet substantial impairments in these functions often persist.

Studies on the neuroplastic capacity of other body functions, such as gross motor and somatosensory functions in CP, have revealed differential patterns of peripheral and central neural reorganization (37–39) that have helped develop improved treatments in these domains. Examples include interventions such as constraint-induced movement therapy, bimanual training, and gross motor goal-directed training (40–46), which have been shown to be efficacious. Similar work aiming to determine the nervous system’s reorganizational capacity for swallowing and motor speech development in CP has not been conducted to date and could be critical in our efforts to improve treatments and long-term swallowing and speech outcomes for these children.

Underlying Mechanisms of Swallowing and Speech in Typical Development and in CP: What Do We Know and Gaps of Knowledge

Research in typical development demonstrates significant gradual maturation in the coordination of motor gestures in the early years of life for both swallowing and speech (47–51). For the neuromuscular development of swallowing, most studies have focused on timing and duration of the swallow response measured via surface electromyography and have found that older children (i.e., ∼12 yr of age) show shorter, more efficient swallowing durations compared with younger children (i.e., 4 yr of age) (52, 53). Development of the neuromuscular control of speech has been more extensively studied. A plethora of literature in this area has shown that as children develop neurophysiologically and anatomically (54), they demonstrate commensurate changes in acoustic features of speech (55) and refinement of speech motor patterns (47), reaching adult-like neuromuscular speech control (i.e., highly efficient, stable control of speech production) after 14 yr of age (54–56).

For children with CP, these underlying mechanisms are less understood. In regard to swallowing, an early small-scale study of 11 4–11 yr olds with spastic CP and 10 typically developing children found that the group with CP exhibited significantly higher amplitude of submental muscle activity during swallows of puree and chewable solids (57). However, this level of activity was not correlated with clinical behavioral swallowing outcomes. Similar higher amplitude of neuromuscular activity has also been documented for masticatory muscles during chewing in this population (58, 59). Furthermore, these overactivation patterns are usually accompanied by longer burst duration of muscle activity and overall greater variability in both duration and amplitude compared with typically developing controls (58, 59).

For the neuromuscular control of motor speech function in individuals with CP, the literature is also extremely limited, includes very small sample sizes (n < 6), has focused on adults, and, not surprisingly, provides mixed findings. Specifically, an electrophysiological study found reduced normalized mean amplitude of perilabial and submental muscle activity during consonant-vowel productions in the two participants with unilateral CP [UCP; i.e., a CP subtype caused by lesions/abnormalities that predominantly involve one hemisphere, with primarily one side of the body affected (60)] compared with the healthy adults (61). In contrast, another electrophysiological study of six young adults with spastic CP found the opposite pattern, i.e., increased normalized mean amplitude and burst duration in a variety of oral motor movements (62), as well as activation of a larger number of orofacial muscles than seen in controls (61–63). Research on the neuromuscular control of speech in children with CP is currently lacking.

These earlier studies provide preliminary evidence supporting that the neuromuscular control of swallowing and speech is different between typically developing individuals and small, heterogeneous groups of individuals with CP. Potential cross-system interactions between these two functions have rarely been explored in typical development (for an exception see references 52, 64), and have not been explored at all in children with CP. In adults, evidence has emerged that interventions in one domain may lead to cross-system benefits for the other domain [e.g., Lee Silverman Voice Treatment, Recline and Head Lift exercises, Expiratory Muscle Strength Training (65–67)]. In children, and in CP, discovering such interactions could be useful in our efforts to improve current or develop new and more efficient treatments for swallowing and speech deficits. Therefore, to start determining neuroplastic adaptations for swallowing and speech, as well as the extent to which these domains interact in children with CP, we conducted a prospective two-site cross-sectional study including a battery of behavioral swallowing and motor speech assessments, a sEMG evaluation, and a brain MRI protocol (not included in this manuscript). This paper focuses on the sEMG data and on correlations between electrophysiological parameters and behavioral outcomes.

The Current Study

Similar to prior research on neural reorganization in early brain damage (40, 68), we initiated this work with a focus on unilateral CP. This is the most common CP subtype, provides a relatively homogeneous subgroup, and offers a less complex system structurally and functionally than other subgroups of CP, thereby serving as a foundation to begin understanding neurophysiological reorganization in this population before exploring other CP groups (16, 69). Furthermore, swallowing and speech both have bilateral neural control and rely in part on brainstem networks (24, 70). Thus UCP, where primarily one hemisphere is affected and lesions are variable, may be a potentially useful model to determine neurophysiological reorganization for swallowing and speech development. Indeed, children with UCP may exhibit difficulties in both domains, but, as we recently showed, they typically have a wide range of swallowing and motor speech skills (16), which could further provide insights into varying degrees and patterns of neuromuscular adaptations needed for these functions. We further observed preliminary correlations between reduced speech intelligibility and clinical swallowing difficulties in these children (16), and the next step is to examine the underlying neuromuscular and neurophysiological mechanisms underpinning these outcomes. Delineating these mechanisms could be important in our efforts to design more effective and physiologically based interventions that are currently limited for this population (33, 35, 71).

Thus, our first aim in this study was to examine differences in patterns of neuromuscular activity during swallowing and speech tasks between school age children with UCP and typically developing children (TDC). Based on prior evidence (4, 5, 17, 57–59), we hypothesized that children with UCP would exhibit higher amplitude and reduced neuromuscular coordination compared with TDC across examined tasks. Second, we aimed to determine commonalities and differences in neuromuscular activation patterns between tasks of swallowing and speech designed to increase in neuromuscular complexity in a parallel fashion. We hypothesized that there would be both common and separate activation patterns across tasks. A third exploratory aim was to determine potential relationships between muscle activity patterns during swallow and speech tasks (e.g., normalized amplitude, time to peak amplitude, and bilateral synchrony) and clinical/behavioral measures of swallowing and motor speech skills in the UCP group.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study is a cross-sectional electromyographic study, which is part of the larger two-site research study mentioned earlier.

Participants

Children with UCP and TDC were recruited at two academic clinical centers from fall 2015 to fall 2020: Purdue University, in West Lafayette IN, and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, in Columbus OH. Children were recruited through flyers, word of mouth, ads, social media, and through the Cerebral Palsy Research Network Clinical Registry.

Inclusion criteria for all participants included: 7–12 yr of age, scoring within normal limits on nonverbal cognition testing (greater than 70 on the Test of Nonverbal Intelligence; TONI) (72) and being able to lie still for 30–40 min (criterion for the MRI portion of the larger study). Children with UCP also had to satisfy the additional inclusion requirements of 1) a diagnosis of spastic or ataxic UCP confirmed by a pediatric neurologist, 2) a mean length of utterance greater than or equal to 3.5 morphemes, and 3) being orally fed. Exclusion criteria for both groups included history of neurological diagnoses (other than CP for the CP group), head/neck surgery or radiation, hearing impairment, or any MRI contraindications (e.g., neurostimulators, intracranial or intraorbital metallic foreign bodies; claustrophobia, etc.). Dyskinetic CP was another exclusion criterion for the UCP group, because excessive movements could interfere with sEMG and MRI data collection procedures (conducted as part of the larger study).

This study was approved by the Purdue University Institutional Review Board (Protocol No. 1410015417) for both sites. Children’s parents provided written informed consent, and all children gave assent.

Behavioral Assessments

The behavioral assessments and outcomes have been described in detail in Malandraki et al. (16). In short, these included 1) screenings (i.e., hearing and nonverbal intelligence screenings), 2) CP-specific functional evaluations of gross motor skill, manual function, eating and communication abilities by certified therapists [i.e., ratings of Gross Motor Function Classification System (73), Manual Ability Classification System (74), Eating and Drinking Ability Classification System (75), Communication Function Classification System (CFCS) (76)], 3) a clinical swallowing assessment, and 4) a motor speech skills assessment.

The clinical swallowing assessment included an evaluation of clinical feeding and swallowing competencies and signs of difficulty using the dysphagia disorder survey (DDS) (77) and a refined clinical measure of eating efficiency, known as normalized mealtime duration (nMD) (16). Both measures were based on observations during a “snack time” including self-administered standardized volumes/quantities of a liquid (water), a nonchewable solid (pudding), and a chewable solid (pretzel). Motor speech skills were evaluated through measures of speech intelligibility (78, 79) and speech rate (78) using the Test of Children’s Speech Plus (TOCS+) (78). Children were recorded while repeating a prerecorded model of randomly generated sets of words and sentences using a delayed imitation paradigm (82). Three different adult listeners, blinded to group, were randomly assigned to orthographically transcribe each child’s productions independently, and intelligibility scores were calculated as percent of words correctly transcribed for words and sentences, per TOCS+ procedures and guidance (78, 79). Speech rate (including pauses) was calculated by syllables produced per minute for the five longest utterances produced by each child via the TOCS+ sentences (82).

Experimental Data Collection: Electrophysiological (Neuromuscular) Assessment of Swallowing and Speech

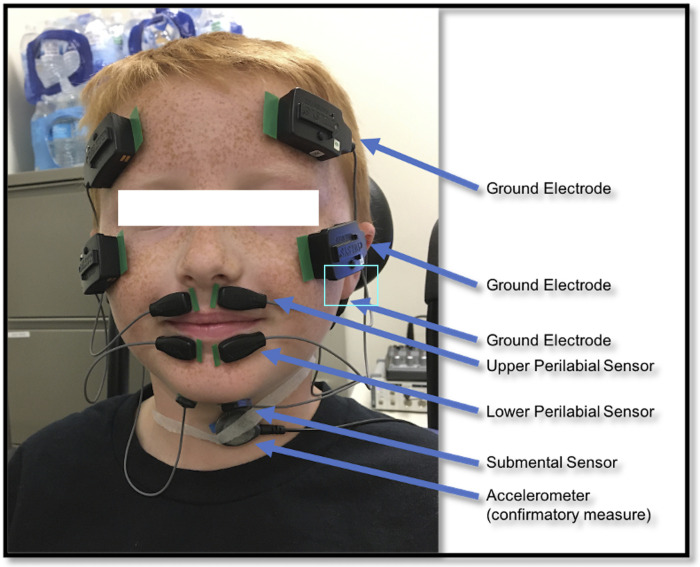

Children also participated in a surface electromyographic (sEMG) evaluation of two groups of muscles bilaterally (see Fig. 1), the perilabial muscles (including superior and inferior orbicularis oris) and the submental (under the chin) muscles (i.e., the mylohyoid, geniohyoid, and anterior belly of the digastric), during swallowing and speech tasks. Data were acquired using bio-amp system PowerLab 16/30 (ADInstruments, Inc., Colorado Springs, CO) and pairs of double differential wireless electrodes (Trigno Mini Sensors, Delsys). Surface electromyography was selected as a noninvasive method to record motor unit action potentials (83). When placed on orofacial or submental areas, sEMG records the summation of motor unit action potentials from groups of muscles in those areas, and thus, allows us to investigate how the underlying muscles are organized in relation to target behaviors. Perilabial and submental muscle groups were targeted because they are the most involved in each domain (speech and swallowing, respectively) and are also accessible for evaluation through noninvasive sEMG. Specifically, perilabial muscles were primarily selected because of their role during speech, i.e., they are known to be continuously activated during speech with peaks of activation associated with bilabial sounds (82, 83). Submental muscles were primarily selected because of their role during pharyngeal swallowing (hyolaryngeal excursion) (84–86). Both of these muscle groups also play some role in the other domain [e.g., perilabial muscles are active during food reception (84) and remain active during the pharyngeal swallow, likely to maintain labial closure; 87], and submental muscles facilitate anterior tongue positioning during speech (90, 92, 93). Given the complex, interdigitated anatomical arrangement of these muscles, the potential role of cross talk must be considered. We followed guidance of prior work on optimal interelectrode distances for the submental area (83) and for the perilabial muscles (85) to minimize cross talk. We recorded activity of these muscle groups for both functions using a series of swallow and speech tasks that gradually increase in neuromuscular complexity in a parallel fashion (92, 93) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

sEMG sensor configuration. sEMG, surface electromyography.

Table 1.

Experimental tasks advancing gradually in neuromuscular complexity

| Complexity Level | Swallow Domain Tasks | Speech Domain Tasks* |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | 5-mL thin liquid | 2-syllable words (“baba” and “mama”) |

| Level 2 | 10-mL thin liquid | 4-syllable words (“babababa” and “mamamama”) |

| Level 3 | 5-mL pudding | Short sentences (“Mom pats the puppy.” and “Monkey drives the purple and yellow boat.”) |

The techniques used for sEMG data acquisition and processing were consistent with prior work by our laboratory and others (83, 96). Specifically, for data collection, children were seated comfortably in a Rifton chair with back and foot support to ensure a relaxed and supported seating posture. After they were familiarized with the equipment, their skin on the perilabial and submental areas was cleaned with an alcohol wipe and with tape to optimize skin adherence and conductivity of the electrodes (83, 97). Then pairs of the double differential wireless electrodes were placed bilaterally over the upper and lower lip and on the submental area (under the chin). The upper lip pair of electrodes were placed between the midline and the corner of the mouth (84) with corresponding grounds placed on the forehead. The lower lip electrodes were placed horizontally below the vermillion border of the lower lip, between the midline and corner of the mouth, with ground electrodes placed on the cheekbones. Finally, the submental pair of electrodes were placed below the chin over the platysma, parallel to the mandibular line, with the corresponding grounds placed on the mastoid process (Fig. 1). The data acquisition system was calibrated to record sEMG signals from the electrodes at a 2-kHz sampling rate with a 550-microvolt range. A bandpass filter of 10–500 Hz was used during signal acquisition to enable optimal detection and resolution of the signal (83). A mains filter was also used to attenuate extraneous noise in the environment to increase signal-to-noise ratio.

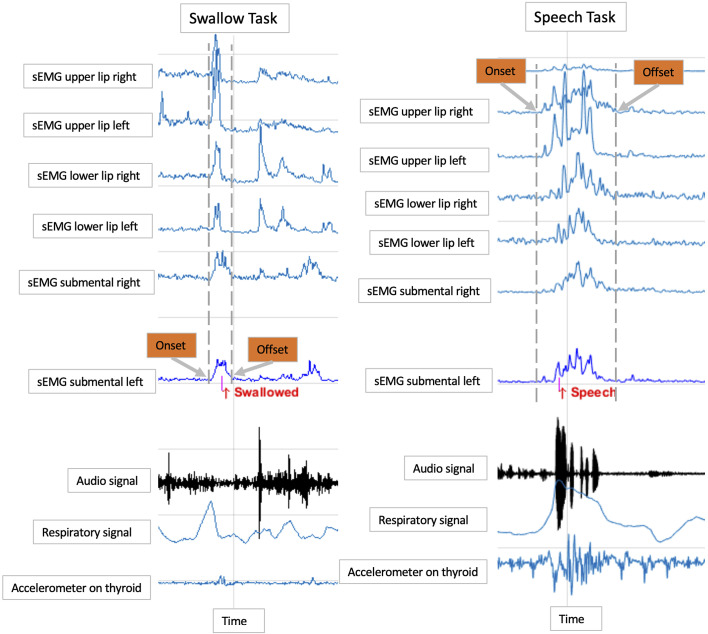

Swallows were confirmed through three complementary methods: respiratory inductance plethysmography using a band with piezoelectric sensors placed around the rib cage under the axilla to record the movement of the rib cage during respiration and swallow events (19, 97), an accelerometer sensor placed laterally next to the thyroid notch to signal laryngeal movement during swallows (98), and an observer’s button that was pressed at first sign of laryngeal elevation indicating a swallow event (97). Speech events were confirmed via a time-synched acoustic signal recorded using an omnidirectional external microphone. Examples of sEMG and other (task confirmatory) signals recorded during a swallow and speech event are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Smoothed sEMG signals of a 5-mL swallow task and a two-syllable word (baba) speech task, along with events’ confirmatory measures. sEMG, surface electromyography.

Data collection began with a 30-s rest period to establish a quiet baseline signal. Following this period, we instructed children to complete criterion reference maneuvers, i.e., maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) of the submental and perilabial muscles, which were later used for sEMG amplitude normalization, i.e., a critical method to ensure comparability of the sEMG amplitude values across subjects. To elicit MVC of the perilabial muscles, children completed three trials of exaggerated lip pursing, which has been used in numerous previous studies to normalize sEMG amplitude values of perilabial muscle activity (83, 97, 99). For maximal submental MVC, they completed three trials of maximum lingual pressure using the Iowa Oral Performance Instrument (IOPI; IOPI Medical) (98). The maximum tongue press task was selected because it elicits high activation of the submental muscle group (83, 100, 101) and can be accurately and reliably measured using the IOPI. sEMG amplitudes were normalized to the highest of the three MVC values for each muscle group/task and are reported as %MVC (102).

Experimental tasks for swallowing and speech were specially designed to gradually, and in a parallel fashion, increase neuromuscular complexity to ensure robust comparisons between domains (see Table 1). The order of the swallow and speech tasks was counterbalanced between children. For swallow tasks, children were instructed to take the bolus, prepare it for swallowing, and then hold the bolus until signaled by a research assistant to swallow. This bolus hold was critical for the sEMG signal of the swallow events to be clearly identified and reliably analyzed. For speech tasks, they were asked to repeat prerecorded stimuli of the words or sentences (heavy in bilabial sounds). Swallow tasks were repeated three times; each word was repeated twice, and the sentences were repeated 10 times each. For the word-level speech tasks (levels 1 and 2), we analyzed the simplest phonological units (i.e., baba and babababa) to ensure similar, low, demands on working memory between swallowing and speech tasks (103, 104) (Table 1). Before initiating the experimental tasks, all children completed practice trials of all tasks. The tasks were explained and, if needed, modeled by an experimenter before each practice and all participants (including those with UCP) were able to complete all tasks successfully. Accurate completion of this process was confirmed through the sEMG signal and the confirmatory signals, which were being recorded during the practice trials, as well. For the swallows, specifically, at times when a child swallowed without holding the bolus (rare occurrence), the trial was repeated.

Electrophysiological Data Analysis

sEMG processing.

The raw signal files were exported to MATLAB (MATLAB Inc., Natick, MA). These files were loaded in MATLAB R2017a through custom-written MATLAB scripts including all necessary pre- and postprocessing sEMG analysis steps (83, 84, 105). Artifact identification, defined as high and sudden signal spikes in amplitude that could not be attributed to muscle activity or variations in slope width time, was completed automatically by the script through predefined criteria determined through prior pilot data analysis and consistent with our previously published research protocols (96, 97). All automatically identified artifacts were reviewed by a trained experimenter to ensure accuracy. After artifact removal, the signal was bandpass filtered between 20 and 300 Hz and notch filtered at 60 Hz (83, 84). The raw signal was full-wave rectified and smoothed with an 80-ms window.

For analysis, swallow and speech events were initially visually identified from the sEMG signal by a trained research assistant with the use of the aforementioned confirmatory measures (i.e., respiratory inductance plethysmography, accelerometry, and an observer’s manual trigger for the swallows, and an audio signal recorded via microphone for the speech events). All sEMG data were collected in conjunction with these four confirmatory measures, which were time-locked to the signal via the PowerLab bio-amp system.

To visually identify the swallow events, the trained research assistant ensured that the burst of identified muscle activity occurred at the same time as the swallowing apnea captured via respiratory plethysmography and/or the vertical movement of the thyroid notch captured with the accelerometer, and the live tag entered (via manual user trigger, i.e., button push) at the time of the swallow. To visually identify speech events, we used the time-locked audio signal (captured via the microphone) corresponding to the muscle burst. After the visual identification of the events, the precise onset and offset of muscle activity for each trial was then defined as a change greater than 2 SDs from the baseline of the sEMG signal and was determined through a custom-written MATLAB script and prespecified algorithm (95, 105). This algorithm is designed to identify a change in baseline that is greater than 2 SDs within the researcher-identified window and determines the onset and offset of sEMG activity. This is a method used in our prior work and ensures reliability of measurement (97, 105). All sEMG analysis was conducted by trained research assistants who were required to achieve over 85% reliability on outcome variables with the PI and senior researcher (last author) before initiating analysis.

Outcome variables.

Normalized mean sEMG amplitude (area under the curve). Normalized mean sEMG amplitude (area under the curve), as a percentage of MVC (maximum voluntary contraction), is an indication of the level of muscle contraction (106, 107). The smoothed sEMG signal amplitude of swallowing tasks was normalized to the submental muscles MVC value (IOPI) (97), and the smoothed sEMG signal amplitude of the speech tasks to the perilabial muscles MVC value (lip pursing) (105). This normalization procedure allows valid comparisons of sEMG amplitudes across tasks and across subjects. Therefore, all amplitude values are reported as a percentage MVC values and are averages from all trials completed per task. In addition, to allow for valid comparisons between swallowing and speech tasks (given the different durations between tasks), we further normalized these %MVC values to the duration of each task.

Time-to-sEMG peak amplitude. Time-to-peak sEMG amplitude indicates how quickly muscles can reach their maximum level of activation from the very beginning of the contraction and provides information similar to reaction time (106). To calculate time to peak, the latency between the onset of muscle activity and the peak amplitude was calculated for each swallowing or speech event in all channels.

Bilateral synchrony. Cross-correlations between sEMG channels of muscle pairs have been used as an index of coordinative synchrony when studying muscle pairs of the head and neck in several populations, including adults (108, 109), infants and children with typical development (64, 110), and children who stutter (84). In these studies, right and left muscle pairs are cross-correlated to quantify the extent to which the muscle pairs activate together in time, thus reflecting temporal coordination between sides (i.e., coordinative synchrony). Given the primary clinical group of interest in the present study (unilateral CP), characterized by primarily unilateral brain lesions, and the bilaterally controlled head and neck functions of interest, it was considered critical to investigate this additional outcome variable. Thus, as an index of bilateral synchrony, we computed pairwise zero-lag cross-correlation coefficients for each bilateral pair of submental or upper lip channels (left and right) during swallowing or speech tasks. The resulting correlation coefficients were squared, and averages of these coefficients across tasks for each condition were then calculated for each participant.

Statistical Analysis

A priori power analysis using G*Power 3.0 identified that a sample size of ∼15 participants per group would detect an effect size of 1.06 or larger between-group means in each domain, 80% of the time (swallowing and speech) for the primary outcome measure (normalized amplitude).

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS institute, Cary NC). For aims 1 and 2, which examine differences between participants with UCP and TDC participants across tasks and between tasks of similar neuromuscular complexity across domains, we used linear mixed-models via the MIXED procedure (SAS institute, Cary NC). Clinical group, muscle location, and task were fixed effects, with random subject and subject-by-task effects to account for the multiple observations per subject. In addition, we employed Kenward-Roger approximation for denominator degrees of freedom. When appropriate, the data were log-transformed before analysis (i.e., to adjust for a skewed response with nonconstant variance). Post hoc comparisons of means were performed using Tukey’s multiple comparison adjustment. For exploratory aim 3, we investigated correlations between all sEMG outcome variables and behavioral outcomes (nMD, DDS, intelligibility, and speech rate) using Pearson and Spearman correlations. For all aims, we used a significance level of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographics and Clinical/Behavioral Data Section

Nineteen children with UCP were recruited for the larger CP study referenced above. We recruited more than the 15 children indicated in our power analysis in anticipation of potential data collection difficulties in our clinical population. One child was excluded for not scoring within normal limits on intelligence testing, and two participants’ sEMG data files were not properly saved and were unable to be salvaged, so they were also excluded. Therefore, 16 children with unilateral cerebral palsy (UCP; 10 males and 6 females) were included. Similarly, one TD child did not complete the sEMG portion, and two TDC’s files were not properly saved, thus 16 typically developing children (TDC; 10 males and 6 females) participated in this study (see Table 2). The children with UCP ranged in age from 7;2 (yr;mo) to 12;2 (M = 9.98; SD = 1.45). The TDC ranged in age from 7;6 to 12;3 (M = 9.80, SD = 1.52). Detailed demographic and clinical data of these children is included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographics of participants

| Summary of Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|

| UCP (n = 16) | TDC (n = 16) | |

| Sex | 10 males/6 females | 10 males/6 females |

| Age range (yr; mo) | 7;2–12;2 | 7;6–12;3 |

| Race | White = 11 Black = 3 Asian or Pacific Islander = 1 Not reported = 1 |

White = 16 |

| TONI scores | 75–113 | 88–136 |

| Left/right lesions | 10/4* | N/A |

| GMFCS scores | Level I = 11 Level II = 5 |

N/A |

| MACS scores | Level I = 2 Level II = 13 Level III = 1 |

N/A |

| EDACS scores | Level I = 9 Level II = 5 Level III = 2 |

N/A |

| Type of lesion | Cortical/subcortical = 10 Malformation = 2 Periventricular/white matter = 3 Unknown: 1 |

N/A |

| Isometric strength of anterior tongue (measured with IOPI) | Above normal range = 0 Normal range = 9 Below normal range = 7 |

Above normal range = 2 Normal range = 14 Below normal range = 0 |

*Side of lesion was unclear on the anatomical MRIs of two children. EDACS, eating and drinking classification system; GMFCS, gross motor function classification system; IOPI, Iowa oral performance instrument; MACS, manual ability classification scale; n, number of participants; TDC, typically developing children; TONI, test of nonverbal intelligence; UCP, unilateral cerebral palsy.

Notes: Maximum isometric strength of the anterior tongue ranges are based on 85% confidence intervals of tongue strength in TDC (111).

Aim 1: Comparisons between Groups

To address aim 1 (comparing muscle activity patterns between groups), linear mixed models were used to investigate if there were interactions or main effects for our three fixed-effect factors—clinical group, task, and muscle location for each of the outcome variables. For the UCP group, both for physiological reasons and based on the fact that activation between sides was statistically different, unaffected and affected sides of each muscle group were considered separately in the analysis. For the TDC, values for left and right channels were averaged, because no significant differences were found between left and right sides for this group. Therefore, the “group” variable had three levels for comparison (TDC, UCP unaffected, and UCP affected). Also, there were occasional missing observations, comprising less than 0.5% of the full electromyographic dataset. These missing values were addressed with Kenward-Rogers approximation for denominator degrees of freedom.

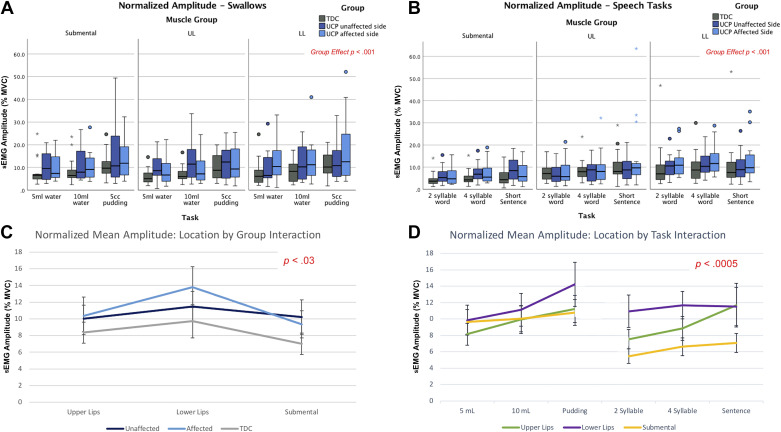

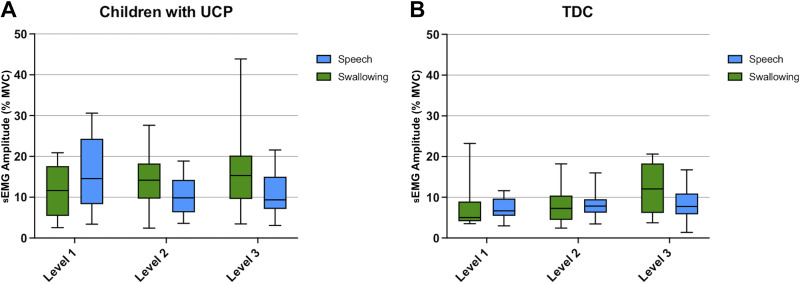

Normalized mean sEMG amplitude.

Normalized mean sEMG amplitude values for all swallowing and speech tasks are depicted in Fig. 3, A and B, with details on statistical models in Supplemental Table S1. Of primary relevance to aim 1, we found a significant main effect for “group” [F(2,157) = 6.73, P = 0.0016]. Pairwise comparisons indicate that normalized mean amplitude across tasks and muscle locations was higher in both the affected and unaffected sides of the children with UCP compared with TDC (see gray line on Fig. 3C). Please note that all box plots depict raw data.

Figure 3.

A and B: normalized mean sEMG amplitude (% MVC) of all muscle groups during tasks of speech and swallowing for both groups. C: interaction plot depicting muscle location by group interaction for normalized mean sEMG amplitude (% MVC), with standard error bars. D: interaction plot depicting muscle location by task interaction for normalized mean sEMG amplitude (% MVC), with standard error bars. All small colored symbols (small asterisks, dots) above box plots are data points. MVC, maximum voluntary contraction; sEMG, surface electromyography.

Furthermore, in the full model, we observed a significant two-way interaction between “group” (TDC, UCP affected, and UCP unaffected) and muscle location [F(4,346) = 2.67, P = 0.03], primarily driven by the UCP group. As seen in Fig. 3C, i.e., a statistical interaction plot depicting this relationship, children with UCP exhibited overall higher normalized mean amplitude of perilabial muscle activity on their affected side (light blue line) compared with their unaffected side (dark blue line) across swallowing and speech tasks; while the submental muscle group demonstrated overall higher amplitude on the unaffected compared with the affected side in this group. Our analysis also revealed a significant interaction between muscle group location and task [F(10,375) = 3.26, P = 0.0005] (Fig. 3D). As seen in Fig. 3D, normalized mean amplitude gradually increased as neuromuscular task complexity increased within both the swallowing and speech domains. In addition, submental muscle group activity was higher for swallowing tasks than speech, while the normalized mean amplitude of the perilabial muscles was more similar across tasks in both domains.

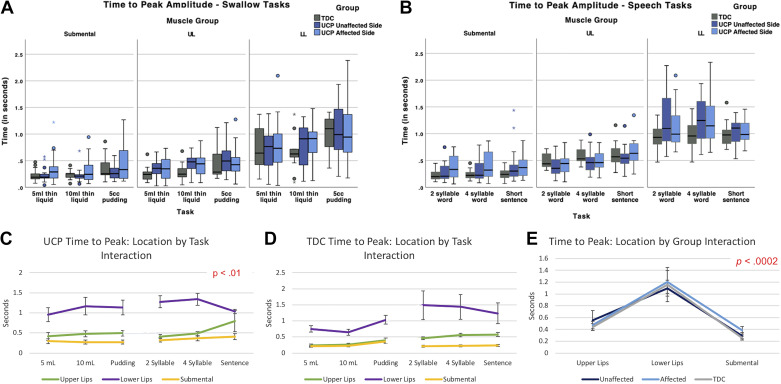

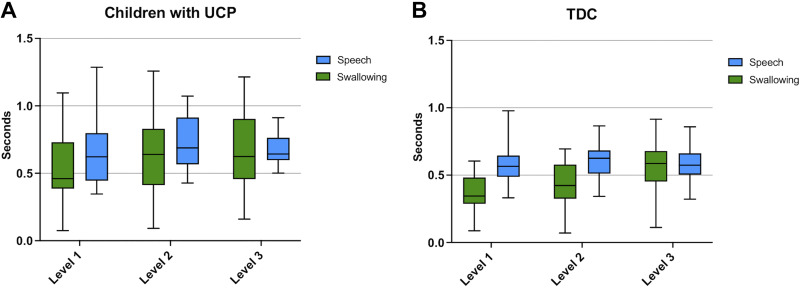

Time-to-peak sEMG amplitude.

Time-to-peak sEMG amplitude values for all swallowing and speech tasks across muscle groups are depicted in Fig. 4, A and B, with statistical values also in Supplemental Table S1. Of primary interest to this aim, we found a significant main effect for “group” [F(2,429.4) = 4.21, P = 0.0154], indicating that, across tasks, all muscle pairs of the UCP group (on both affected and unaffected sides) required a longer time to reach their peak amplitude of activity than those of TDC.

Figure 4.

A and B: time to sEMG peak amplitude of muscle groups during tasks of swallowing and speech for both groups. C and D: interaction plots depicting muscle location by group by task interaction for normalized mean sEMG amplitude (% MVC), with standard error bars. E: interaction plot depicting muscle location by group interaction for normalized mean sEMG amplitude (% MVC), with standard error bars. All small colored symbols (small asterisks, dots) above box plots are data points. MVC, maximum voluntary contraction; sEMG, surface electromyography; TDC, typically developing children; UDP, unilateral cerebral palsy; TDC, typically developing children; UDP, unilateral cerebral palsy.

In addition, our full analysis revealed a significant three-way interaction between “group” (TDC, UCP affected side, and UCP unaffected side), muscle location, and task [F(20,1007) = 2.44, P < 0.01]. As seen in Fig. 4, C and D, children with UCP required longer time to reach the peak amplitude of lower lip muscle activity during swallows than TDC (purple line in both images), whereas time-to-peak amplitude for the upper lip muscles (green line) and the submentals (yellow line) was relatively similar across tasks for both groups. Children with UCP also required a longer time to reach peak amplitude than TDC for the upper lip muscles (green line) for swallowing tasks and sentences.

The model also revealed two significant two-way interactions: the first was between “group” and muscle location [F(4,491.5) = 5.51, P < 0.01; Fig. 4E]. Time-to-peak sEMG amplitude was longer for the lower lip muscle group than the upper lip or submental muscle area across groups and domains. For the unaffected side, the upper lip showed a longer time to peak than for the lower lip or submental. The second two-way interaction was between muscle location and task [F(10,415.9) = 2.20, P < 0.02]. The lower lip muscles (purple line) required more time to reach peak amplitude than the submental (yellow line) and upper lip (green line) muscles, and overall, a slight numerical increase in time-to-peak amplitude was observed as complexity of tasks increased, with the exception of the lower lip muscles during sentences (Fig. 4, C and D).

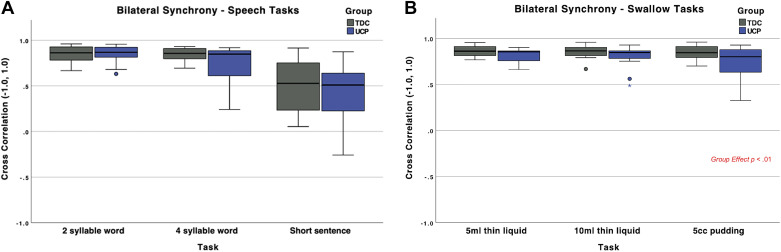

Bilateral synchrony.

As a reminder, bilateral synchrony between the left and right sides (indexed by correlations between left and right muscle pairs) was calculated for the submental muscles for all swallow tasks and for the upper lip muscles for the speech tasks, given their relative contributions to each domain. Mean values of bilateral synchrony are depicted in Fig. 5, A and B, with full statistics information in Supplemental Table S1.

Figure 5.

A and B: bilateral synchrony of muscle groups during tasks of swallowing and speech. All small colored symbols (small asterisks, dots) above box plots are data points. TDC, typically developing children; UDP, unilateral cerebral palsy.

The linear mixed-effect model for bilateral synchrony of swallowing revealed no interactions, but a main effect for “group.” Specifically, children with UCP had lower bilateral synchrony of the submental pair of muscles than the TDC group across all swallowing tasks [F(2, 88) = 9.45, P = 0.0028] (Fig. 5).

The model for speech showed no statistically significant differences between groups in bilateral synchrony of the upper lip pair of muscles [F(2,87) = 2.47, P = 0.1198] (Fig. 5, A and B).

Aim 2: Comparisons of Parallel Tasks between Domains

For aim 2 (i.e., comparing parallel tasks between swallowing and speech domains), linear mixed models were computed for two of the outcome measures—normalized mean sEMG amplitude and time to peak amplitude—to examine neuromuscular complexity-based interactions or main effects between parallel tasks across the two domains. Separate models were computed for children with UCP and TDC because we found significant differences between groups in aim 1. As bilateral synchrony was calculated for only the submental muscles for swallowing tasks and the upper lip muscles for speech tasks, a linear mixed model with only task was used with each pair of parallel tasks compared.

Normalized mean sEMG amplitude.

For normalized mean sEMG amplitude, we found a significant main effect for domain (swallowing vs. speech) [F(1,87.5) = 5.24, P < 0.02], in parallel with our findings from aim 1, and no main effect for neuromuscular complexity. Specifically, children with UCP overall had higher normalized mean amplitude across swallowing tasks compared with speech tasks (except for level 1; Fig. 6), with no significant differences as complexity increased. For the TDC group, no main effect for domain was found [F(1,90.1) = 1.84, P < 0.18], indicating similar normalized mean amplitude across parallel swallowing and speech tasks. Furthermore, for the TDC, we observed a significant effect of complexity level [F(2,90.1) = 3.16, P < 0.05], with normalized mean amplitude increasing with task complexity in both domains.

Figure 6.

Normalized mean sEMG amplitude across tasks of swallowing and speech at the three parallel levels of complexity for children with UCP (A) and TDC (B). sEMG, surface electromyography; TDC, typically developing children; UCP, unilateral cerebral palsy.

Time-to-peak sEMG amplitude.

For time-to-peak sEMG amplitude, in the UCP group, we also observed a significant main effect for domain (swallowing vs. speech) [F(1,90.47) = 9.40, P < 0.01], with children with UCP primarily demonstrating longer time to reach peak amplitude of muscle activity for speech than swallowing tasks, though there was considerable variability, as seen in the plots depicted in Fig. 7A. For the TDC, there was also a significant main effect for domain [F(1,478.9) = 56.13, P < 0.01], where again TDC required longer time to reach their peak amplitude of muscle activity for speech than for swallowing tasks. Furthermore, we saw a significant main effect for neuromuscular complexity for both children with UCP [F(1,90.48) = 9.40, P < 0.04] and TDC [F(2,26.56) = 23.86, P < 0.01], with generally longer time to reach peak amplitude for more complex tasks for both groups.

Figure 7.

Time-to-peak sEMG amplitude across tasks of swallowing and speech at the three levels of complexity for children with UCP (A) and TDC (B). sEMG, surface electromyography; TDC, typically developing children; UCP, unilateral cerebral palsy.

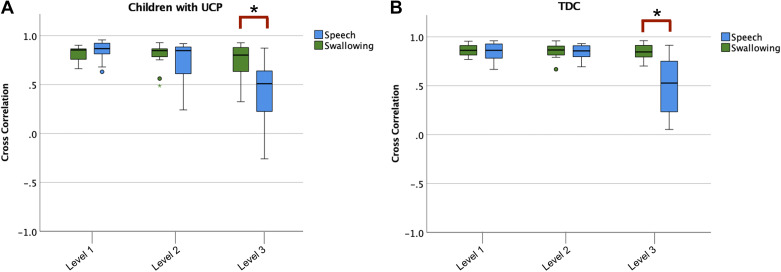

Bilateral synchrony.

For bilateral synchrony, there were no significant differences across the level 1 and level 2 neuromuscular complexity tasks (Fig. 8). However, there was a statistically significant difference between the level 3 tasks (5-mL pudding vs. sentences) for both the submental muscles pair (t = 6.27, P < 0.01) and upper lip muscles pair (t = 3.99, P < 0.01).

Figure 8.

Bilateral muscle synchrony across tasks of swallowing and speech at the three levels of complexity for children with UCP (A) and TDC (B). *P < 0.05. All small colored symbols (small asterisks, dots) below box plots are data points. TDC, typically developing children; UCP, unilateral cerebral palsy.

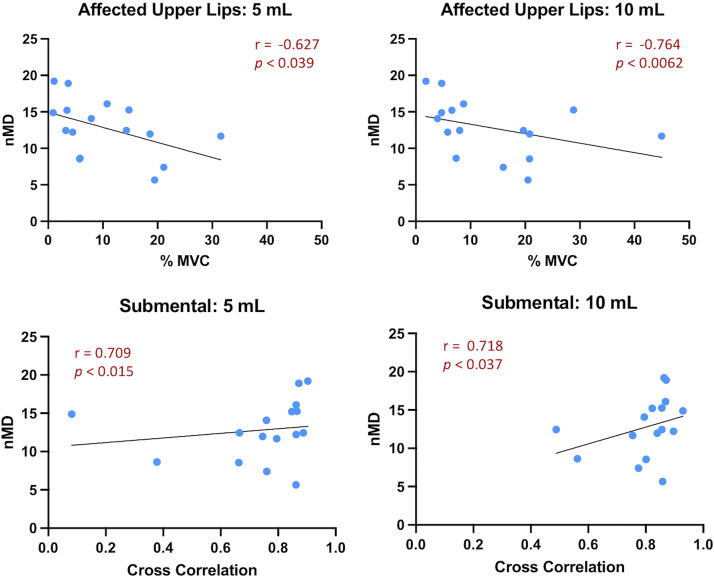

Aim 3 (Exploratory Aim): Correlations between sEMG Outcome Variables and Clinical/Behavioral Measures for UCP Group

Supplemental Tables S2 and S3 summarize the exploratory correlations calculated between the sEMG variables for each task (within domain) and the clinical/behavioral measures for each domain (swallow and speech) for the UCP group. Given the small sample size and the variability of behavioral scores (16), we only report herein correlations (r) above 0.6, and we acknowledge that they have to be interpreted with caution. For swallows, four such correlations were observed (Fig. 9). Specifically, there were two negative correlations between normalized mean sEMG amplitude (%MVC) of the affected upper lip muscles during thin liquid swallows and normalized mealtime duration (5-mL swallows: r = −0.63, P < 0.03; 10-mL swallows: r = −0.76, P < 0.01, respectively), indicating that higher amplitude of affected upper lip muscles during liquid swallows was associated with shorter (faster) normalized mealtime duration. There were also two positive correlations between bilateral synchrony of the submental muscles during liquid swallows and normalized mealtime duration (5-mL swallows: r = 0.71, P < 0.01; 10-mL swallows: r = 0.72, P < 0.01 respectively), indicating that higher submental bilateral synchrony during liquid swallows was associated with longer (slower) normalized mealtime duration. For speech, no such correlations were observed (Supplemental Table S3).

Figure 9.

Correlations (r) above 0.6 between sEMG variables and behavioral measures of swallowing tasks for the UCP group. MVC, maximum voluntary contraction; nMD, normalized mealtime duration; sEMG, surface electromyography; UCP, unilateral cerebral palsy.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we aimed to delineate mechanisms of neuromuscular adaptations related to swallowing and speech and investigate relationships between these two important systems in a sample of children with unilateral CP compared with TDC. We have previously shown that children with UCP have a range of swallowing and motor speech skills varying from functional to significantly impaired (16, 57). However, the underlying mechanisms that may drive this range of behavior are unclear. To start investigating this, we compared neuromuscular activation patterns of children with UCP with varying degrees of swallowing and motor speech skills and typically developing peers during carefully designed tasks that advanced in neuromuscular complexity in a parallel fashion. Furthermore, we wanted to explore if there were relationships between muscle activation patterns and clinical behavioral measures of swallowing and speech in the UCP group.

Patterns of Neuromuscular Activity in UCP and TDC: Group Comparisons

Consistent with our hypotheses, the group with UCP demonstrated several differences in basic muscle activation patterns than their typically developing peers, for all three of our sEMG outcome variables: normalized mean amplitude, time-to-peak amplitude, and bilateral synchrony, and across both domains of swallowing and speech.

For normalized mean amplitude, a correlate of muscular effort, children with UCP demonstrated higher muscular effort than TDC across muscle groups and tasks in both swallowing and speech domains. Within the UCP group, there were slight differences on the side (affected or unaffected) that had higher amplitude for each muscle pair; however, both sides exhibited higher amplitude than that produced by the TDC. This increased amplitude of activity, or overactivation pattern, has also been noted in earlier work comparing orofacial neuromuscular activity of children with CP (across types) and TDC during mastication (58, 59), swallowing (57), and loud speech (63). This overactivation could be an adaptive or maladaptive neuromuscular pattern resulting from either early disruptions in the central motor pathways and/or by the presence of spasticity common in CP, including in UCP (112). Early (pre- or perinatal) disruptions in the corticobulbar and corticospinal tracts, structures that are key contributors to muscle tone and posture and promote normal muscle development, are often observed in CP (113). In children with UCP, specifically, several central rewiring mechanisms of the corticospinal tracts have been described (114) and similar mechanisms are likely to be present for the corticobulbar system as well, driving these neuromuscular adaptations. In addition, individuals with CP have difficulties inhibiting muscle activation in the presence of spasticity (112), resulting in both increased activation and overuse of multiple muscle groups. Although spasticity in the bulbar system is not as often overtly observed (especially in the muscles of interest in this study) as in the limbs, its presence cannot be ruled out. Thus, underlying spasticity could potentially contribute to the observed increased orofacial muscle activity levels during swallowing and speech events in our UCP group.

In addition to increased muscular effort, children with UCP also required increased time to reach their peak amplitude of muscle activity. This was more pronounced for the lower lip muscle group overall. Although, to our knowledge, this has not been previously documented for the bulbar systems of interest in children with CP, similar timing/coordination issues have been documented for the limb muscles in this population. For example, Downing and colleagues (115) examined temporal characteristics of lower extremity weakness using force sensors in six children with CP (GMFCS level 1–3) compared with TDC. They found that the children with CP needed increased time to produce and reduce lower limb movements and rate of force relaxation was significantly negatively correlated with measures of overall gross motor function (115). Another study also focused on the lower limbs found evidence of premature activation of the gastrocnemius paired with a longer mean duration of activity during ambulation (116). These increases in muscle activation duration and delays in peak amplitude seen in children with CP across the extremities and the bulbar system could be a centrally generated neuromuscular adaptation (113) or could reflect subtle differences in muscle properties of children with CP and typical peers. Indeed, children with CP are known to demonstrate not only increased variation in the size of muscle fibers but also lower shortening velocities, which could be reflected in increased time to reach peak amplitude of activity (117, 118). Further studies exploring both central adaptations through neuroimaging techniques and peripheral (muscular) tissue composition and properties through ultrasound or dynamic MRI approaches could provide critical additional insights to help explain these results in greater depth.

It is well known that both speech and swallowing motor neuron pools are bilaterally innervated (24, 119, 120), which is often reflected in the high temporal coordination between left and right muscle pairs (a.k.a. bilateral synchrony). This variable is measured using zero-lag cross-correlation coefficients computed between sEMG envelopes obtained from left and right muscle pairs and has been extensively used in assessing the coordination/synchrony of orofacial muscle activity for speech (51, 64, 84, 118). Several developmental speech studies have shown robust bilateral orofacial muscle coordination for speech tasks in typical development, even as early as the age of 2 yr (64, 84). To our knowledge, cross-correlational orofacial indices have not been previously assessed in children with UCP for either speech or swallowing. We did not see a difference in bilateral synchrony of the upper lip muscle groups for the speech tasks between our groups; however, the UCP group showed reduced temporal coordination between the left and right submental muscle areas for swallowing. This finding suggests that, for the submental muscle groups and swallowing, asymmetrical neural commands are delivered to the right and left submental motor neuron pools of the UCP group, providing further evidence for the potential contribution of central neural rewiring mechanisms in these children. This pattern is not seen for the perilabial muscle coordination during speech, possibly indicating differential central rewiring for each muscle group, and perhaps as a function of task.

Shared and Separate Neuromuscular Activity Patterns: Domain Comparisons

We also examined commonalities and differences in neuromuscular activation across tasks of swallowing and speech with relatively similar neuromuscular complexity. We sought to start exploring potential cross-system interaction between swallowing and speech by examining if these domains have fully distinct or partially shared neuromuscular mechanisms. Our data revealed both shared and separate patterns of neuromuscular activation between these two systems, which differed in the children with UCP and TDC.

First, TDC required similar muscular effort for parallel tasks of swallowing and speech, and that effort increased as neuromuscular complexity increased in both domains. This common (across domains) graded performance is a novel finding that provides confirmation that the tasks used were meaningful for the domain comparisons and that muscle groups are activating differently based on task demands. For time-to-peak sEMG amplitude, TDC demonstrated both differences and similarities between domains; i.e., they needed more time to reach peak sEMG amplitude for speech tasks than swallows, but again, demonstrated increases in the time to reach peak amplitude with increased task complexity within each domain. For our third outcome variable, bilateral synchrony, TDC demonstrated similar, robust coordination between left and right sides for all tasks, with the exception of sentences for the upper lip muscle pair. This exception is not unexpected, since sentences have varied phonetic targets, not all of which require lip activity. In sum, in typical development, it appears that there are several similarities in basic muscle activation patterns between the two domains, particularly in amplitude/effort and bilateral coordination, when tasks of parallel neuromuscular complexity are compared. At a preliminary level, these results support some level of shared neuromuscular underpinnings of swallowing and speech in TDC. Early work comparing patterns of orofacial muscle activity during speech and nonspeech tasks (e.g., chewing and swallowing) in typically developing infants, children (52, 64, 121–123), and adults (109, 121, 124) has overall supported separate neuromuscular control patterns for speech versus nonspeech tasks. However, these earlier investigations used tasks that were noncontrolled and difficult to directly compare between domains (e.g., chewing and speech). In our study, we developed carefully designed swallowing and speech experimental tasks of relatively parallel neuromuscular complexity, which we believe were critical in starting to delineate commonalities and differences of neuromuscular swallowing and speech control in typical development.

For children with UCP, we also observed both differences and similarities between the two domains. First, this group demonstrated a higher amplitude of activity and a shorter time to reach peak amplitude for swallowing than speech tasks, indicating different neuromuscular activity patterns between domains for these two variables. There were also no differences in normalized amplitude with increased complexity. This indicates that children with UCP used similar (relatively high) magnitude of effort for all tasks (from simplest to most complex) across domains, showcasing the aforementioned overactivation and lack of specificity in activation patterns that are seen in other orofacial tasks as well (58, 59). The children with UCP also demonstrated overall more variability than TDC across neuromuscular complexity levels and domains but similar bilateral coordination between left and right sides for most tasks. Findings again start to delineate both commonalities and differences in neuromuscular control of speech and swallowing in children with UCP. It would be important to further understand these commonalities and differences, as they may provide grounds for developing separate or cross-system or multimodal interventions in the future. Critically, adding measures of central control mechanisms in future work would also be key in more clearly delineating the identified patterns.

Relationship between sEMG Outcome Variables and Behavioral Data in UCP

Our sample included children with UCP with a range of motor speech and swallowing skills, reported in detail in a prior publication (16). To start understanding the mechanisms behind this range of behaviors, we explored whether the neuromuscular patterns we observed in each domain were related to the behavioral outcomes in this group. Given the relatively small sample size and the variability of the behavioral scores (16), this analysis is exploratory at this stage and is interpreted with caution.

This exploratory analysis showed that increased muscular effort (especially of the affected upper lip area) during liquid swallows may be related to shorter (or faster) normalized mealtime duration (nMD), while higher bilateral synchrony of the submental muscle group during liquid swallows may be related to longer (slower) nMD. Although these findings may seem contradictory, upon validation with future larger-scale work, they may explain differential types of adaptations developed within this population. Normalized mealtime duration is a measure of eating efficiency obtained during a snack/meal, which has been shown to vary substantially in children with UCP (16), with some children exhibiting slower and some faster nMD than their typically developing peers. This could mean that both slow and fast pace of consuming a snack/meal are adaptive/maladaptive behaviors for these children (16). In the current study, we found that higher muscular effort was correlated with faster normalized mealtime duration, whereas higher bilateral synchrony was related to slower nMD. Therefore, this relationship may represent a trade-off that children are making between efficiency and effort. There appears to be some variability in which element children prioritize during meals, which could explain the varying patterns we previously observed. For speech tasks, there were no correlations >0.6 observed. Overall, and as already mentioned, these correlational results should be interpreted with caution, given the exploratory nature of this aim, and the potential differences between behavior during isolated swallows/speech events versus a whole meal or conversation. Continuing this exploration with a larger sample of children with UCP during more naturalistic experimental conditions and examining longitudinal data would shed light on these preliminary relationships and how they may develop or adapt over time. Furthermore, in the future it would be clinically useful to collect similar data from younger typically developing age groups. This would allow for the current UCP data to be compared with earlier development data and help determine whether the behavioral and neuromuscular patterns observed are consistent with a developmental delay or are atypical.

Limitations

We acknowledge that this study has limitations that need to be considered in future work. First, we had a relatively small sample of children with UCP, most of whom had mild to moderate deficits in speech and swallowing (16), and thus our findings can only be generalized to similar groups of children. However, it is noteworthy that we still found robust differences in neuromuscular activation patterns in this group of children with UCP when compared with typically developing peers. In addition, speaking and swallowing with multiple sensors attached to the face and neck, as required during our experimental paradigm, is not as natural as spontaneous nonexperimental tasks. Also, we had some technical difficulties with the lower lip sensors, particularly in participants who drooled, and the length of our experimental protocol was long (∼2 h) and could have contributed to fatigue for some of our participants. Using more resilient (to drooling) and less intrusive orofacial sEMG sensors and a shorter paradigm should be considered in similar future work. Finally, we acknowledge that measuring the muscle activity of isolated swallow and speech events within an experimental task is different than examining mealtime behavior or a full speech sample. Therefore, the exploratory relationships we reported in aim 3 should be interpreted with caution. Future research could extend this work by examining neuromuscular activation in more naturalistic settings.

Conclusion

Children with UCP demonstrate the remarkable capacity of the human nervous system to recover and reorganize after damage and disease. This study revealed three key findings: 1) children with UCP use more orofacial muscular effort and take longer to reach their peak effort for swallowing and speech tasks when compared with typically developing peers, 2) both shared and separate muscle activation patterns are observed between speech and swallowing in both TDC and children with UCP, though more shared patterns are seen in TDC, and 3) children with UCP appear to develop a range of neuromuscular activation patterns that are differentially correlated with measures of clinical swallowing function. These findings offer first insights into the neuromuscular adaptations of this population for two critical bulbar functions and provide unique evidence on robust shared and separate neuromuscular underpinnings for swallowing and speech. Further investigating central adaptation patterns and engaging a longitudinal design in the future will be critical in efforts to further elucidate these findings.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental Tables S1–S3: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21502305.v1

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21DC015867 (to G. A. Malandraki), by an American Academy of Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine (AACPDM) and Pedal-with-Pete Foundation research grant (to G. A. Malandraki), and by a pilot grant provided by the Purdue University College of Health and Human Sciences (to G. A. Malandraki).

DISCLAIMERS

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or AACPDM/Pedal-with-Pete Foundation.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.G., A.S., and G.A.M. conceived and designed research; R.E.H.A., S.S.M., B.B., W.B-H., J.P.L., and G.A.M. performed experiments; R.E.H.A., S.S.M., B.A.C., B.B., and G.A.M. analyzed data; R.E.H.A., S.S.M., B.A.C., L.G., A.S., and G.A.M. interpreted results of experiments; R.E.H.A. and S.S.M. prepared figures; R.E.H.A. and G.A.M. drafted manuscript; R.E.H.A., S.S.M., B.A.C., B.B., W.B-H., J.P.L., L.G., A.S., and G.A.M. edited and revised manuscript; R.E.H.A., S.S.M., B.A.C., B.B., W.B-H., J.P.L., L.G., A.S., and G.A.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all participants and their families. In addition, the authors thank our pediatric neurologist Dr. Kristyn Tekulve for confirming the UCP children’s diagnosis, the Speech Language Pathologists, Angela Dixon and Jennifer Cardinal for their help with the motor speech assessments, and our consultant Dr. Andrew Gordon for support throughout the project completion. Many thanks are also due to Cagla Kantarcigil, Valerie Steinhauser, Paige Cornillie, Jennine Bryan, Natalie Tomerlin, Mackenzie Zorn, Caroline Sarbieski, Nicole Dejong, Yaxin Fang, and Tian Xia for their help with data collection and/or analysis. Finally, we are very thankful to Community Products LLC, dba Rifton Equipment for donating the Rifton chair used in this research, and to the Children’s Hemiplegia and Stroke Association (CHASA) and the United Cerebral Palsy Association of Greater Indiana for their valuable support with recruitment. The graphical abstract was created with Biorender.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bax M, Goldstein M, Rosenbaum P, Leviton A, Paneth N, Dan B, Jacobsson B, Damiano D; Executive Committee for the Definition of Cerebral Palsy. Proposed definition and classification of cerebral palsy, April 2005. Dev Med Child Neurol 47: 571–576, 2005. doi: 10.1017/S001216220500112X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Benfer KA, Weir KA, Bell KL, Ware RS, Davies PSW, Boyd RN. Longitudinal cohort protocol study of oropharyngeal dysphagia: relationships to gross motor attainment, growth and nutritional status in preschool children with cerebral palsy. BMJ Open 2: e001460, 2012. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benfer KA, Weir KA, Bell KL, Ware RS, Davies PSW, Boyd RN. Oropharyngeal dysphagia and cerebral palsy. Pediatrics 140: e20170731, 2017. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kantarcigil C, Sheppard JJ, Gordon AM, Friel KM, Malandraki GA. A telehealth approach to conducting clinical swallowing evaluations in children with cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil 55: 207–217, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mishra A, Sheppard JJ, Kantarcigil C, Gordon AM, Malandraki GA. Novel mealtime duration measures: Reliability and preliminary associations with clinical feeding and swallowing performance in self-feeding children with cerebral palsy. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 27: 99–107, 2018. doi: 10.1044/2017_AJSLP-16-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reilly S, Skuse D, Poblete X. Prevalence of feeding problems and oral motor dysfunction in children with cerebral palsy: a community survey. J Pediatr 129: 877–882, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(96)70032-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reyes FI, Salemi JL, Dongarwar D, Magazine CB, Salihu HM. Prevalence, trends, and correlates of malnutrition among hospitalized children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 61: 1432–1438, 2019. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Troughton KE, Hill AE. Relation between objectively measured feeding competence and nutrition in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 43: 187–190, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rogers B. Feeding method and health outcomes of children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr 145: S28–S32, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Braza MD, Sakash A, Natzke P, Hustad KC. Longitudinal change in speech rate and intelligibility between 5 and 7 years in children with cerebral palsy. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 28: 1139–1151, 2019. doi: 10.1044/2019_AJSLP-18-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yorkston KM. Treatment efficacy. J Speech Hear Res 39: S46–S57, 1996. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3905.s46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schölderle T, Staiger A, Lampe R, Strecker K, Ziegler W. Dysarthria in adults with cerebral palsy: clinical presentation and impacts on communication. J Speech Lang Hear Res 59: 216–229, 2016. doi: 10.1044/2015_JSLHR-S-15-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schölderle T, Staiger A, Schumacher B, Ziegler W. The impact of dysarthria on laypersons’ attitudes towards adults with cerebral palsy. Folia Phoniatr Logop 71: 309–320, 2019. doi: 10.1159/000493916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schölderle T, Haas E, Ziegler W. Dysarthria syndromes in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 63: 444–449, 2021. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Love RJ, Hagerman E, Taimi EG. Speech performance, dysphagia and oral reflexes in cerebral palsy. J Speech Hear Disord 45: 59–75, 1980. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4501.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Malandraki GA, Mitchell SS, Hahn Arkenberg RE, Brown B, Craig BΑ, Burdo-Hartman W, Lundine JP, Darling-White M, Goffman L. Swallowing and motor speech skills in unilateral cerebral palsy: novel findings from a preliminary cross-sectional study. J Speech Lang Hear Res 65: 3300–3315, 2022. doi: 10.1044/2022_JSLHR-22-00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Parkes J, Hill N, Platt MJ, Donnelly C. Oromotor dysfunction and communication impairments in children with cerebral palsy: a register study. Dev Med Child Neurol 52: 1113–1119, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang BJ, Carter FL, Altman KW. Relationship between dysarthria and oral-oropharyngeal dysphagia: the present evidence. Ear Nose Throat J 97: E1–E8, 2020. doi: 10.1177/0145561320951647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McFarland DH, Lund JP. Modification of mastication and respiration during swallowing in the adult human. J Neurophysiol 74: 1509–1517, 1995. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.4.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lund JP, Kolta A. Brainstem circuits that control mastication: do they have anything to say during speech? J Commun Disord 39: 381–390, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Price CJ. A review and synthesis of the first 20 years of PET and fMRI studies of heard speech, spoken language and reading. NeuroImage 62: 816–847, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Babaei A, Ward BD, Siwiec RM, Ahmad S, Kern M, Nencka A, Li S-J, Shaker R. Functional connectivity of the cortical swallowing network in humans. NeuroImage 76: 33–44, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eickhoff SB, Heim S, Zilles K, Amunts K. A systems perspective on the effective connectivity of overt speech production. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 367: 2399–2421, 2009. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2008.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Malandraki GA, Sutton BP, Perlman AL, Karampinos DC, Conway C. Neural activation of swallowing and swallowing-related tasks in healthy young adults: an attempt to separate the components of deglutition. Hum Brain Mapp 30: 3209–3226, 2009. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martin RE, MacIntosh BJ, Smith RC, Barr AM, Stevens TK, Gati JS, Menon RS. Cerebral areas processing swallowing and tongue movement are overlapping but distinct: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurophysiol 92: 2428–2443, 2004. doi: 10.1152/jn.01144.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Riecker A, Mathiak K, Wildgruber D, Erb M, Hertrich I, Grodd W, Ackermann H. fMRI reveals two distinct cerebral networks subserving speech motor control. Neurology 64: 700–706, 2005. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152156.90779.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saarinen T, Laaksonen H, Parviainen T, Salmelin R. Motor cortex dynamics in visuomotor production of speech and non-speech mouth movements. Cereb Cortex 16: 212–222, 2006. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Croft RD. What consistency of food is best for children with cerebral palsy who cannot chew? Arch Dis Child 67: 269–271, 1992. doi: 10.1136/adc.67.3.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gisel EG, Schwartz S, Haberfellner H. The Innsbruck Sensorimotor Activator and Regulator (ISMAR): construction of an intraoral appliance to facilitate ingestive functions. ASDC J Dent Child 66: 180–187, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pennington L, Miller N, Robson S, Steen N. Intensive speech and language therapy for older children with cerebral palsy: a systems approach. Dev Med Child Neurol 52: 337–344, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ray J. Functional outcomes of orofacial myofunctional therapy in children with cerebral palsy. Int J Orofacial Myology 27: 5–17, 2001. doi: 10.52010/ijom.2001.27.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Larnert G, Ekberg O. Positioning improves the oral and pharyngeal swallowing function in children with cerebral palsy. Acta Paediatr 84: 689–692, 1995. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arvedson JC, Clark HM, Lazarus CL, Schooling T, Frymark T. The effects of oral-motor exercises on swallowing in children: an evidence-based systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 52: 1000–1013, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pennington L, Parker NK, Kelly H, Miller N. Speech therapy for children with dysarthria acquired before three years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7: CD006937, 2016. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006937.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Snider L, Majnemer A, Darsaklis V. Feeding interventions for children with cerebral palsy: a review of the evidence. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 31: 58–77, 2011. doi: 10.3109/01942638.2010.523397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miller N, Pennington L, Robson S, Roelant E, Steen N, Lombardo E. Changes in voice quality after speech-language therapy intervention in older children with cerebral palsy. Folia Phoniatr Logop 65: 200–207, 2013. doi: 10.1159/000355864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Eyre JA, Taylor JP, Villagra F, Smith M, Miller S. Evidence of activity-dependent withdrawal of corticospinal projections during human development. Neurology 57: 1543–1554, 2001. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.9.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wilke M, Staudt M, Juenger H, Grodd W, Braun C, Krägeloh‐Mann I. Somatosensory system in two types of motor reorganization in congenital hemiparesis: topography and function. Human Brain Mapp 30: 776–788, 2009. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gordon AM. To constrain or not to constrain, and other stories of intensive upper extremity training for children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 53: 56–61, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gordon AM, Hung Y-C, Brandao M, Ferre CL, Kuo H-C, Friel K, Petra E, Chinnan A, Charles JR. Bimanual training and constraint-induced movement therapy in children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy a randomized trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 25: 692–702, 2011. doi: 10.1177/1545968311402508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Novak I, Mcintyre S, Morgan C, Campbell L, Dark L, Morton N, Stumbles E, Wilson S-A, Goldsmith S. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: state of the evidence. Dev Med Child Neurol 55: 885–910, 2013. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sakzewski L, Ziviani J, Boyd RN. Efficacy of upper limb therapies for unilateral cerebral palsy: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 133: e175–e204, 2014. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hoare BJ, Wallen MA, Thorley MN, Jackman ML, Carey LM, Imms C. Constraint‐induced movement therapy in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4: CD004149, 2019. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004149.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Friel KM, Ferre CL, Brandao M, Kuo H-C, Chin K, Hung Y-C, Robert MT, Flamand VH, Smorenburg A, Bleyenheuft Y, Carmel JB, Campos T, Gordon AM. Improvements in upper extremity function following intensive training are independent of corticospinal tract organization in children with unilateral spastic cerebral palsy: a clinical randomized trial. Front Neurol 12: 660780–780, 2021. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.660780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Simon-Martinez C, Mailleux L, Hoskens J, Ortibus E, Jaspers E, Wenderoth N, Sgandurra G, Cioni G, Molenaers G, Klingels K, Feys H. Randomized controlled trial combining constraint-induced movement therapy and action-observation training in unilateral cerebral palsy: clinical effects and influencing factors of treatment response. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 13: 1756286419898065, 2020. doi: 10.1177/1756286419898065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maitre NL, Jeanvoine A, Yoder PJ, Key AP, Slaughter JC, Carey H, Needham A, Murray MM, Heathcock J, Burkhardt S, Emery L, Hague K, Levengood K, Lewandowski DJ, Nelin MA, Pennington C, Pietruszewski L, Purnell J, Sowers B; BBOP Group. Kinematic and somatosensory gains in infants with cerebral palsy after a multi-component upper-extremity intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Brain Topogr 33: 751–766, 2020. doi: 10.1007/s10548-020-00790-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Green JR, Moore CA, Reilly KJ. The sequential development of jaw and lip control for speech. J Speech Lang Hear Res 45: 66–79, 2002. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Green JR, Moore CA, Higashikawa M, Steeve RW. The physiologic development of speech motor control. J Speech Lang Hear Res 43: 239–255, 2000. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4301.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Smith A. Speech motor development: integrating muscles, movements, and linguistic units. J Commun Disord 39: 331–349, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Saletta M, Gladfelter A, Vuolo J, Goffman L. Interaction of motor and language factors in the development of speech production. In: Routledge Handbook of Communication Disorders, edited by Bahr R, Silliman E. New York: Routledge, 2015, p. 381–392. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Smith A, Goffman L. Stability and patterning of speech movement sequences in children and adults. J Speech Lang Hear Res 41: 18–30, 1998. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4101.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Green JR, Moore CA, Ruark JL, Rodda PR, Morvée WT, Vanwitzenburg MJ. Development of chewing in children from 12 to 48 months: longitudinal study of EMG patterns. J Neurophysiol 77: 2704–2716, 1997. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.5.2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Vaiman M, Segal S, Eviatar E. Surface electromyographic studies of swallowing in normal children, age 4–12 years. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 68: 65–73, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Vorperian HK, Wang S, Chung MK, Schimek EM, Durtschi RB, Kent RD, Ziegert AJ, Gentry LR. Anatomic development of the oral and pharyngeal portions of the vocal tract: an imaging study. J Acoust Soc Am 125: 1666–1678, 2009. doi: 10.1121/1.3075589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]