Abstract

Background

Early recovery is an important factor for people undergoing facial plastic surgery. However, the normal inflammatory processes that are a consequence of surgery commonly cause oedema (swelling) and ecchymosis (bruising), which are undesirable complications. Severe oedema and ecchymosis delay full recovery, and may make patients dissatisfied with procedures. Perioperative corticosteroids have been used in facial plastic surgery with the aim of preventing oedema and ecchymosis.

Objectives

To determine the effects, including safety, of perioperative administration of corticosteroids for preventing complications following facial plastic surgery in adults.

Search methods

In January 2014, we searched the following electronic databases: the Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library); Ovid MEDLINE; Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations); Ovid Embase; EBSCO CINAHL; and Literatura Latino‐Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (LILACS). There were no restrictions on the basis of date or language of publication.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs that compared the administration of perioperative systemic corticosteroids with another intervention, no intervention or placebo in facial plastic surgery.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened the trials for inclusion in the review, appraised trial quality and extracted data.

Main results

We included 10 trials, with a total of 422 participants, that addressed two of the outcomes of interest to this review: swelling (oedema) and bruising (ecchymosis). Nine studies on rhinoplasty used a variety of different types, and doses, of corticosteroids. Overall, the results of the included studies showed that there is some evidence that perioperative administration of corticosteroids decreases formation of oedema over the first two postoperative days. Meta‐analysis was only possible for two studies, with a total of 60 participants, and showed that a single perioperative dose of 10 mg dexamethasone decreased oedema formation in the first two days after surgery (SMD = ‐1.16, 95% CI: ‐1.71 to ‐0.61, low quality evidence). The evidence for ecchymosis was less consistent across the studies, with some contradictory results, but overall there was some evidence that perioperatively administered corticosteroids decreased ecchymosis formation over the first two days after surgery (SMD = ‐1.06, 95% CI:‐1.47 to ‐0.65, two studies, 60 participants, low quality evidence ). The difference was not maintained after this initial period. One study, with 40 participants, showed that high doses of methylprednisolone (over 250 mg) decreased both ecchymosis and oedema between the first and seventh postoperative days. The only study that assessed facelift surgery identified no positive effect on oedema with preoperative administration of corticosteroids. Five trials did not report on harmful (adverse) effects; four trials reported that there were no adverse effects; and one trial reported adverse effects in two participants treated with corticosteroids as well as in four participants treated with placebo. None of the studies reported recovery time, patient satisfaction or quality of life. The studies included were all at an unclear risk of selection bias and at low risk of bias for other domains.

Authors' conclusions

There is limited evidence for rhinoplasty that a single perioperative dose of corticosteroids decreases oedema and ecchymosis formation over the first two postoperative days, but the difference is not maintained after this period. There is also limited evidence that high doses of corticosteroids decrease both ecchymosis and oedema between the first and seventh postoperative days. The clinical significance of this decrease is unknown and there is little evidence available regarding the safety of this intervention. More studies are needed because at present the available evidence does not support the use of corticosteroids for prevention of complications following facial plastic surgery.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Anti‐Inflammatory Agents, Anti‐Inflammatory Agents/administration & dosage, Dexamethasone, Dexamethasone/administration & dosage, Ecchymosis, Ecchymosis/prevention & control, Edema, Edema/prevention & control, Glucocorticoids, Glucocorticoids/administration & dosage, Methylprednisolone, Methylprednisolone/administration & dosage, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Rhinoplasty, Rhinoplasty/adverse effects, Rhytidoplasty, Rhytidoplasty/adverse effects

Plain language summary

Corticosteroids for preventing complications following facial plastic surgery

Complications following facial plastic surgery

Today, facial plastic surgery is one of the most common types of surgery. People frequently chose to have it for aesthetic (beauty) reasons, so doctors need to minimise the unpleasant effects (complications) associated with these procedures. All surgical procedures produce an inflammatory response, which may cause swelling and bruising. Severe swelling and bruising are troublesome for patients, as they delay full recovery.

Why corticosteroids might help

Corticosteroids, more often known as 'steroids', are medicines that doctors prescribe to reduce inflammation in a wide range of conditions. They are commonly used in facial plastic surgery to reduce swelling and bruising, though it is not known how efficient or safe they might be.

The purpose of this review

This review tried to find out whether giving corticosteroids around the time of facial plastic surgery reduces swelling and bruising compared to another intervention, no intervention, or a fake medicine (placebo).

Findings of this review

The review authors searched the medical literature up to January 2014, and identified 10 relevant medical trials, with a total of 422 participants. Nine of these studies were on people having rhinoplasty (surgery to reshape the nose) and one was on people having a facelift.The trials investigated a variety of corticosteroid medicines, as well as different doses of corticosteroids. People in the studies were assessed for swelling and bruising for up to 10 days after surgery. None of the studies stated the funding source.

There was some low quality evidence that a single dose of corticosteroid administered prior to surgery might reduce swelling and bruising over the first two days after surgery, but this advantage was not maintained beyond two days. One study, with 40 participants, showed that high doses of corticosteroid decreased both swelling and bruising between the first and seventh postoperative days. The usefulness of these results is uncertain and there is currently no evidence regarding the safety of the treatment. Five trials did not report on harmful (adverse) effects; four trials reported that there were no adverse effects; and one trial reported adverse effects in two participants treated with corticosteroids as well as in four participants treated with placebo. None of the studies reported recovery time, patient satisfaction or quality of life.

Therefore, the current evidence does not support use of corticosteroids as a routine treatment in facial plastic surgery. More trials will need to be conducted before it can be established whether this treatment works and is safe.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| 10 mg single dose perioperative dexamethasone compared with placebo for complications following facial plastic surgery | |||

|

Patient or population: adults undergoing facial plastic surgery Settings: hospital Intervention: corticosteroids Comparison: placebo or no intervention | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (fixed effect) (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Oedema ‐ Day 1 Scale 1 to 4 |

Standardised mean difference ( 95% CI) = ‐1.16 [‐1.71, ‐0.61] | n = 60 2 studies | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 |

|

Ecchymosis ‐ Day 1 Scale 1 to 4 |

Standardised mean difference ( 95% CI) = ‐1.03 [‐1.58, ‐0.49] | n = 60 2 studies | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | |||

1 Both studies with unclear risk of selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment) and small sample size.

Background

Description of the condition

Facial plastic surgery has evolved into one of the most frequently performed collection of surgical procedures. It includes rhinoplasty, craniofacial plastic surgery and face‐lifting (Gurlek 2006; Gurlek 2009; Stuzin 2008). In the USA there were 1.5 million cosmetic plastic surgical procedures in 2009, and two of the five most common procedures were facial (eyelid and nose‐reshaping) (ASPS 2010).

Early recovery is an important factor for people undergoing facial plastic surgery, however, the inflammatory process is a normal consequence of surgery, and can delay recovery. Oedema (an abnormal accumulation of fluid (swelling) beneath the skin due to reduced lymphatic and venous drainage) and ecchymosis (a bruise or collection of blood (haematoma)) are common, but undesirable complications (Stuzin 2008). When oedema and ecchymosis are severe, this is troublesome for patients as it means that full recovery is delayed. Drainage can be employed, with the aim of avoiding postoperative complications, as this removes excess fluid and helps to avoid a build‐up of fluid that could apply pressure to the site of operation (Totonchi 2007). Corticosteroids have also been used for some time with the aim of preventing oedema and ecchymosis (Flood 1999; Habal 1985).

Description of the intervention

It has been suggested that the administration of corticosteroids decreases postoperative inflammation. Studies in plastic surgery have reported favourable effects of steroid use (Owsley 1996), and although various doses, schedules and different routes of steroid administration have been described, overall its effectiveness is not known (Gurlek 2009; Kara 1999; Kargi 2003; Totonchi 2007). Corticosteroids can be administered intravenously, intramuscularly or orally (Kargi 2003; Totonchi 2007). The first dose is given in the preoperative phase (at the time of anaesthetic induction) and administration continues for three to seven days postoperatively (Kargi 2003). Long‐term corticosteroids, also known as 'deposit corticosteroids', are drugs that need fewer applications but have the same therapeutic equivalence and can also be used for the same purpose.

How the intervention might work

The anti‐inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of corticosteroids, in particular glucocorticoids, are well known (Kargi 2003). Corticosteroids act on the pathways of inflammation through inhibiting inflammatory cells. In this way they inhibit the formation of substances that are theoretically capable of generating adverse effects including, oedema, exudation, excessive vasodilation and capillary permeability. Glucocorticoids interact with specific steroid and intracellular receptors that control enzymes and proteins involved in the inflammatory response. The actions of glucocorticoids have been proven to reduce the clinical effects of inflammation, such as oedema, erythema (redness) and pain (Ofo 2006).

Corticosteroids are hormones that are secreted by the adrenal cortex. Synthetic analogues have been developed that affect the whole body and have many side effects. Cumulative doses and duration of application are important factors when looking at complications. It should remembered that the prolonged use of steroids can inhibit the natural production of these hormones by causing suppression of the hypothalamic‐pituitary‐adrenal axis and adrenal gland, which are the most important complications associated with use of exogenous steroids.

Steroids have well‐recognised side effects (gastritis, peptic ulcer and electrolytic changes, sodium retention and water hypertension; and behavioral changes). Osteonecrosis (bone death) of the femoral head (hip bone) has been reported with short‐term use of high‐dose steroid. So, the theoretical anti‐inflammatory benefits of steroids for reducing oedema and ecchymosis following surgery need to be weighed against the associated risks (Ofo 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

The reduction of oedema in craniomaxillofacial reconstructive and aesthetic surgery may be beneficial in improving the immediate postoperative appearance of patients, resulting in a shorter period of convalescence. More importantly, reduction of oedema may be beneficial by preventing more serious oedema‐related complications, such as upper airway obstruction, ecchymosis and pain. Corticosteroids are thought to decrease postoperative swelling (oedema) and bruising (ecchymosis) and a review of the available evidence on their efficacy and safety is warranted.

Objectives

To determine the effects, including safety, of perioperative administration of corticosteroids for preventing complications following facial plastic surgery in adults.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Types of participants

People of either sex, over 18 years of age, undergoing facial plastic surgery (i.e. surgical procedures such as rhinoplasty, craniofacial plastic surgery and face‐lifting).

Types of interventions

The intervention of interest is the administration of perioperative systemic corticosteroids compared with another intervention, no intervention or placebo. We considered the type of corticosteroid, dosage, duration and route of administration used in each study. For the purposes of this review the term 'perioperative' refers to the three phases of surgery: preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative, and commonly includes ward admission, anaesthesia, surgery, and recovery.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Swelling (oedema), measured by specific scale defined by trial authors.

Bruising (ecchymosis), measured by specific scale defined by trial authors.

Pain scored by validated scale, e.g. visual analogue scale (VAS).

Time to complete healing of wounds.

Secondary outcomes

Patient satisfaction ‐ self‐reported level of satisfaction.

Quality of life measured by validated scale, e.g. short form health survey (SF‐36).

Surgical site infection rate.

Any adverse effects related to corticosteroid administration.

Time to return to work.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

In Janury 2014 we searched the following electronic databases to identify reports of relevant RCTs:

The Cochrane Wounds Group Specialised Register (searched 23 January 2014);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 12);

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to January Week 3 2014);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, January 22, 2014);

Ovid Embase (1974 to 2014 January 22);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 23 January 2014).

Literatura Latino‐Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (LILACS) (1982 to 29 January 2014).

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) using the following exploded MeSH headings and keywords:

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Face] explode all trees 2314 #2 MeSH descriptor: [Facial Injuries] explode all trees 334 #3 MeSH descriptor: [Ear] explode all trees 917 #4 (face or facial or nose* or mouth* or "ear" or ears or "lip" or lips):ti,ab,kw 23013 #5 (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4) 24156 #6 MeSH descriptor: [Surgery, Plastic] explode all trees 104 #7 ((plastic next surg*) or (reconstructive next surg*)):ti,ab,kw 1179 #8 (#6 or #7) 1229 #9 (#5 and #8) 223 #10 ((facial near/5 surgery) or (craniofacial near/5 surgery) or (face next lift*) or face‐lift* or facelift*):ti,ab,kw 205 #11 (#9 or #10) 393 #12 MeSH descriptor: [Adrenal Cortex Hormones] explode all trees 11158 #13 (corticosteroid* or corticoid* or glucocorticoid* or steroid*):ti,ab,kw 26630 #14 (dexamethasone or methylprednisolone):ti,ab,kw 6897 #15 (#12 or #13 or #14) 35747 #16 #11 and #15 20

Search strategies for Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase and EBSCO CINAHL can be found in Appendix 1. We combined the Ovid MEDLINE search with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximizing version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the EMBASE search with the Ovid EMBASE filter developed by the UK Cochrane Centre (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the CINAHL searches with the trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 2014). There were no restrictions on the basis of date or language of publication.

We searched the Current Controlled Trials website (http://www.controlled‐trials.com/) for any reports of ongoing trials (last search 29 January 2014).

Searching other resources

We scrutinised reference lists of any identified relevant studies for additional citations. We contacted specialists in the field and tried to contact the authors of the included trials for any possible unpublished data, but with no success.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (EMKS and MVAM) independently assessed the titles and abstracts obtained from the searches for relevance against the inclusion criteria. We obtained full papers when a study appeared to satisfy the inclusion criteria, or where there was doubt regarding its exclusion. Two review authors (EMKS and MVAM) independently assessed the full text papers and reached agreement on which studies met the inclusion criteria. We resolved any disagreement over inclusion by discussion, with referral to a third review author (LMF) for adjudication, if necessary. We recorded reasons for exclusion in the table of 'Characteristics of excluded studies'.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (EMKS and MVAM) independently extracted data using a standard form and resolved any discrepancies by discussion. The review authors extracted the following information: characteristics of the study (design, setting); participants; type of surgery; interventions; outcomes (outcome measures, timing of outcomes, adverse events);and risk of bias criteria.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For this review two review authors independently assessed each included study using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011a). This tool addresses six specific domains, namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other issues (e.g. extreme baseline imbalance) (see Appendix 2 for details of the criteria on which the judgements are based). We assessed blinding and completeness of outcome data for each outcome separately. We completed a 'Risk of bias' table for each eligible study. We discussed any disagreement amongst all review authors to achieve a consensus. We presented our assessment of risk of bias using a 'Risk of bias' summary figure, which presents all of the judgements in a cross‐tabulation of study by entry. This display of internal validity indicates the weight the reader may give the results of each study.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous variables, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For continuous outcomes, we calculated the mean difference (MD) and 95% CIs, if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods. We would have analysed time to wound healing and time to return to work as survival (time‐to‐event) data, using the appropriate analytical method (as per the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2011)), but data for these outcomes were not available in the included studies.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis (unit to be randomised for interventions to be compared) was the individual participant, i.e. the number of observations in the analysis should match the number of individuals randomised.

Dealing with missing data

Irrespective of the type of data, we reported dropout rates in the Characteristics of included studies table and we used intention‐to‐treat analysis if necessary. (Higgins 2011b).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by looking at type of corticosteroid, dosage, duration and route of administration and type of facial plastic surgery. We examined statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). This examines the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance. Values of I2 under 25% indicate a low level of heterogeneity; values of I2 between 25% and 75% are considered moderate; values of I2 higher than 75% indicate high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates we plan to assess publication bias by drawing a funnel plot (trial effect versus trial size), if a sufficient number of studies are included in the review.

Data synthesis

Methods of synthesising the studies depended on quality, design and heterogeneity. We explored both clinical and statistical heterogeneity. In the absence of clinical and statistical heterogeneity (I2 less than 25%) we applied a fixed‐effect model to pool data. In the presence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 between 25% to 75%) we planned to apply a random‐effects model for meta‐analysis (Higgins 2003). Where synthesis was inappropriate (I2 greater than 75%) we presented a narrative overview.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Depending upon heterogeneity and the data available, we planned to conduct meta‐analysis by subgroups:

different types of surgery (for example, rhinoplasty and facelift surgery);

intravenous or oral intervention;

type of corticosteroid preparation (e.g. prednisolone, betamethasone, cortisone, dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, prednisone and triamcinolone);

low and high dose interventions ‐ a low dose of corticosteroid will be defined as a total dose per day of 300 mg or less of hydrocortisone (or equivalent); otherwise the dose will be considered to be a high dose.

In this version of the review the available data allowed us to perform subgroup analyses by type of corticosteroid preparation and low or high doses.

Sensitivity analysis

We included all eligible trials in the initial analysis and planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to evaluate the effect of trial quality (risk of bias). This was done by excluding the trials most susceptible to bias based on our risk of bias assessment, namely: those with inadequate allocation concealment; high levels of post‐randomisation losses or exclusions; and uncertain or unblinded outcome assessment (Deeks 2011). However, due to the few meta‐analyses that could be performed, this analysis was not performed in this version of the review. In future updates if further studies can be summarized, we will perform the sensitivity analysis

Presentation of results

We presented the main results of the review in a 'Summary of findings' table, which provides key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined, and the sum of available data on the main outcomes, as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration (Schünemann 2011a). The main outcomes were summarised in the 'Summary of findings' table, which also includes an overall grading of the evidence relating to each of the main outcomes, using the GRADE approach (Schünemann 2011b).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified 172 records from the searches. After closer examination of the titles and abstracts of these references, we excluded all but 15 studies from further analysis. We obtained full‐text copies of these studies for further assessment after which, 10 of them were found to fulfil all the inclusion criteria for this review (Griffies 1989; Gurlek 2006; Gurlek 2009; Hoffmann 1991; Kara 1999; Kargi 2003; Koc 2011; Owsley 1996; Ozdel 2006; Totonchi 2007), four were excluded (Berinstein 1998; Echavez 1994; Rapaport 1995; Saedi 2011), and one is awaiting classification (see Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification ).

Included studies

Design of the studies

The 10 studies included in the review were prospective, randomised, double‐blinded trials. Four trials were conducted in the USA (Griffies 1989; Hoffmann 1991; Owsley 1996; Totonchi 2007), and six in Turkey (Gurlek 2006; Gurlek 2009; Kara 1999; Kargi 2003; Koc 2011; Ozdel 2006). All studies were single‐centred and none reported sample size calculations in their methods.

Participants and duration of trial

All 10 included studies had small sample sizes, ranging between 20 and 60 participants of both sexes. Most studies included only adults; two studies included participants from 15 years of age (Hoffmann 1991;Totonchi 2007). We decided to include these studies because we believe that they do not introduce risk of bias. All participants were healthy and underwent surgery for aesthetic reasons. The age range and sex distribution for each study are presented in the Characteristics of included studies table. Nine studies included only participants who underwent rhinoplasty (Griffies 1989; Gurlek 2006; Gurlek 2009; Hoffmann 1991; Kara 1999; Kargi 2003; Koc 2011; Ozdel 2006; Totonchi 2007); only one study assessed people undergoing facelift surgery (Owsley 1996).

Two studies only assessed outcomes for the first two days following surgery (Griffies 1989; Ozdel 2006); the remaining eight studies had follow‐ups of seven to 10 days.

Types of interventions

We observed great heterogeneity in the doses and corticosteroid administration routes among the studies. In three studies, 10 mg of dexamethasone was administered (Griffies 1989; Kara 1999; Ozdel 2006). None of the included studies evaluated long‐term corticosteroids.

In Gurlek 2006 the 40 participants were randomised into five groups (eight in each group). Each group received one of the following for three days: betamethasone 8 mg, dexamethasone 8 mg, methylprednisolone 40 mg, tenoxicam 20 mg, or placebo.

In Gurlek 2009 40 participants were randomly divided into five groups (eight in each group). Each group received one of the following interventions: a single 250 mg dose of methylprednisolone, a single 500 mg dose of methylprednisolone, four 250 mg doses of methylprednisolone, four 500 mg doses of methylprednisolone, or placebo.

In Hoffmann 1991 the intervention group (24 participants) received 10 mg intravenous (IV) dexamethasone in a single dose, and 50 mg of oral prednisone on the first postoperative day, tapering to 10 mg/day for five days (i.e. 40 mg, 30 mg, 20 mg, 10mg). The control group (25 participants) received placebo.

In Kargi 2003 60 participants were allocated into six groups (10 in each group). Each group received one of the following: a single dose of 8 mg IV dexamethasone one hour before the operation; a single dose of 8 mg IV dexamethasone at the beginning of the operation; three doses of 8 mg IV dexamethasone, the first dose one hour before the operation and subsequent doses at 24 and 48 hours after the operation; three doses of 8 mg IV dexamethasone, the first dose at the beginning of the operation and subsequent doses 24 and 48 hours after the operation; three doses of 8 mg IV dexamethasone, the first dose immediately after the operation and subsequent doses 24 and 48 hours after the operation; or no dexamethasone before or after the operation.

In Koc 2011, participants were divided into three groups: the first group (15 participants) received a single dose of 1 mg/kg IV methylprednisolone; the second group (15 participants) received a single dose of 3 mg/kg IV methylprednisolone preoperatively; and the third group (10 participants) acted as the control group with no intervention.

In Owsley 1996 the intervention group (15 participants) received 500 mg of methylprednisolone IV as a perioperative loading dose followed intraoperatively by 2 ml of 10 mg/ml triamcinolone (Kenalog) solution that was sprayed onto the face and neck wound at the subcutaneous plane prior to incision closure. This was followed by oral administration of methylprednisolone in a six‐day dose‐taper format, beginning with 24 mg on postoperative day 1 and decreasing by 4 mg per day. The control group (15 participants) received only topical buffered 0.25% marcaine with epinephrine (1:200,000) sprayed on the subcutaneous wound bed.

In Totonchi 2007, participants were randomised into three groups (16 participants in each group) that received one of the following: 10 mg IV dexamethasone intraoperatively followed by a six‐day oral tapering dose of methyl‐prednisone; arnica three times a day for four days; or neither agent (this group served as the control).

Outcome measurements

Seven studies used the same scale of 0 to 4 for evaluating the degree of oedema and ecchymosis. The scale for periorbital ecchymosis (bruising around the eyes) was as follows: 0 (none), 1 (present in the medial canthus (area adjacent to the nose where upper and lower eyelids join)), 2 (extending to the pupil), 3 (extending past the pupil), 4 (extending to the lateral canthus (i.e. the area where upper and lower eyelids join that is opposite the medial canthus). The scale for eyelid oedema was as follows: 0 (none), 1 (minimal), 2 (extending to the iris), 3 (extending to the pupil), 4 (massive oedema) (Gurlek 2006; Gurlek 2009; Hoffmann 1991; Kara 1999; Kargi 2003; Koc 2011; Ozdel 2006).

Although Griffies 1989 also used a 0 to 4 scale, it was different from that used in the studies cited above (severity of oedema and ecchymosis were rated as (+) 1 for medial third of periorbital region, (+) 2 for lower two‐thirds, (+) 3 for lower and upper two‐thirds and (+) 4 for the entire periorbital region.

Totonchi 2007 used a 0 to 5 scale for bruising (no change, yellow, light purple, dark purple, very dark purple) and 0 to 3 for oedema (no oedema. mild, moderate and severe oedema).

Owsley 1996 evaluated facial oedema alone, with full‐face frontal and oblique photographs on postoperative days 1, 4 and 10, using a scale of 1 to 4, where 1 was the minimum and 4 the maximum.

None of the studies reported the remaining two primary outcomes, that is, pain, and time taken to achieve healing. Adverse effects were reported in six of the included studies (Griffies 1989; Gurlek 2006; Gurlek 2009; Hoffmann 1991; Kara 1999; Kargi 2003); none of the others reported secondary outcomes. None of the trials reported patient satisfaction, quality of life, surgical site infection rate or time taken to return to activities.

Excluded studies

Four studies were excluded, one because the control group received an active decongestant drug (Saedi 2011); another because there was an important difference in the baseline characteristics between the two groups (a greater number of participants underwent additional procedures in the steroid group) (Rapaport 1995); one due to insufficient data about baseline characteristics and outcome measurement (Echavez 1994); and the final one because data were reported inconsistently (Berinstein 1998) (authors contacted unsuccessfully) (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

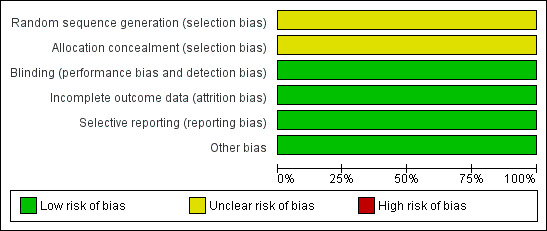

Risk of bias in included studies

As all the studies presented unclear risk of bias in one domain; no high‐quality studies were included in this review (Figure 1).

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Although all 10 included studies were defined as randomised, none of them described the way in which the randomisation sequence had been obtained or how concealment of allocation had been accomplished. Therefore, they were all classified as presenting an unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

The studies included in this review reported that blinding of the participants and the outcome observer had been implemented, which gave them a low risk of performance and detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

The trials analysed all randomised participants. None of the ten included studies reported if there were any losses during the follow up.

Selective reporting

All the included studies reported oedema and ecchymosis, two of the primary outcomes. Five of the ten articles included in this review did not report adverse effects as an outcome.

Other potential sources of bias

The 10 included studies appeared to be free of other sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Although most of the studies used the same four‐point scale for measuring oedema and ecchymosis, the results were presented in different ways (means, graphs and median), which made it difficult to conduct meta‐analyses. We have tried to contact all authors for more information, but have received no response.

Corticosteroids compared with placebo or with no medication

Ten trials with 422 participants were included in this comparison (Griffies 1989; Gurlek 2006; Gurlek 2009; Hoffmann 1991; Kara 1999; Kargi 2003; Koc 2011; Ozdel 2006; Totonchi 2007).

Oedema (swelling)

Rhinoplasty

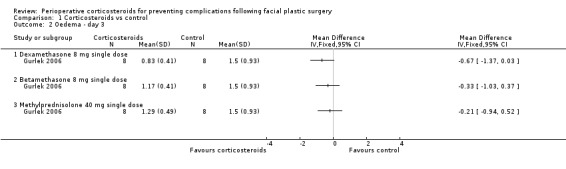

Two studies with unclear methodological quality compared 10 mg dexamethasone given just before surgery with placebo and rated the outcome on the first day after the intervention (day 1) (Griffies 1989; Ozdel 2006). The analysis of these trials was performed using the standardised mean difference (SMD) because the scales used to report the results were different. Pooling of the two studies revealed a statistically significant difference in favour of corticosteroids, SMD ‐1.16, (95% CI ‐1.71 to ‐0.61) with no heterogeneity (I2= 0%) (Analysis 1.1). Gurlek 2006 compared three different corticosteroids (dexamethasone 8 mg, betamethasone 8 mg and methylprednisolone 40 mg) with placebo administered preoperatively and found no significant differences among the three corticosteroid groups on day 1, SMD ‐0.30 (95% CI ‐1.29 to 0.68), SMD ‐0.93 (95% CI ‐1.98 to 0.12) and SMD ‐1.08 (95% CI ‐2.15 to ‐0.01), respectively (Analysis 1.1). However, the lack of statistical significance may be due to the small sample size. Similarly, on days 3 and 7 there were no significant differences in oedema between any of the three corticosteroid groups (Analysis 1.2; Analysis 1.3).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids vs control, Outcome 1 Oedema ‐ day 1.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids vs control, Outcome 2 Oedema ‐ day 3.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids vs control, Outcome 3 Oedema ‐ day 7.

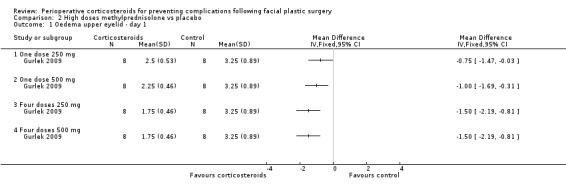

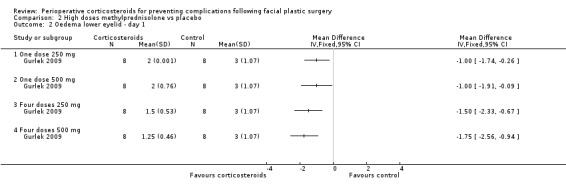

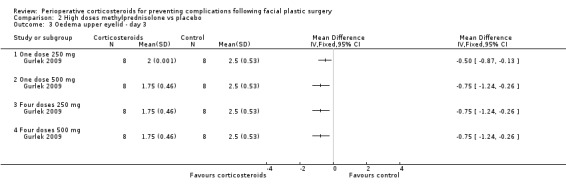

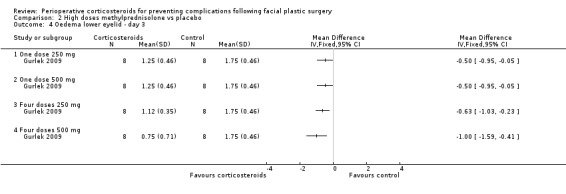

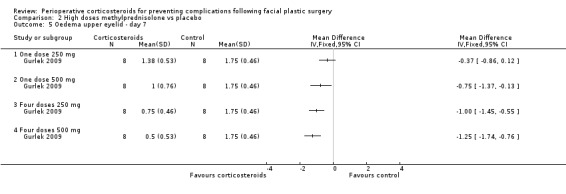

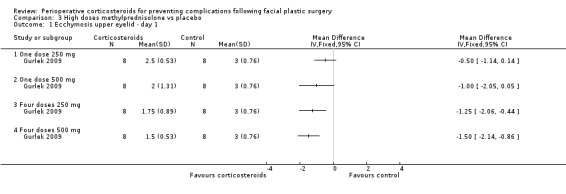

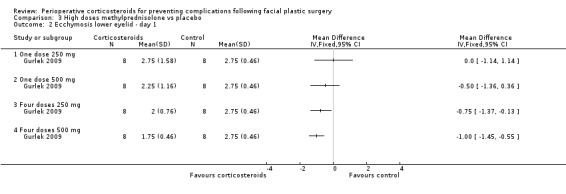

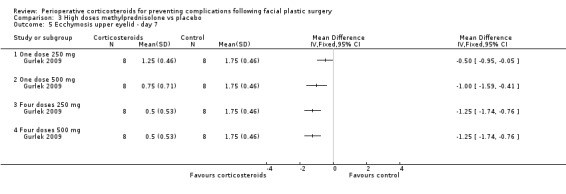

Gurlek 2009 compared four different doses of methylprednisolone (one dose of 250 mg; one dose of 500 mg; four doses of 250 mg; four doses of 500 mg) with placebo. The high doses of corticosteroid produced a statistically significant reduction in the extent of oedema for both upper and lower eyelids on days 1 and 3 when compared with placebo (P value<0.05) (Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4). On day 7 the group receiving 250 mg showed no statistical difference between the steroid and placebo for upper eyelid oedema. However, the difference was statistically significant for all other doses for both upper and lower eyelids (Analysis 2.5; Analysis 2.6).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo, Outcome 1 Oedema upper eyelid ‐ day 1.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo, Outcome 2 Oedema lower eyelid ‐ day 1.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo, Outcome 3 Oedema upper eyelid ‐ day 3.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo, Outcome 4 Oedema lower eyelid ‐ day 3.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo, Outcome 5 Oedema upper eyelid ‐ day 7.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo, Outcome 6 Oedema lower eyelid ‐ day 7.

Hoffmann 1991 did not provide the standard deviations for the outcome measures, which precluded inclusion of this trial in the meta‐analysis. The trial authors reported that the mean for oedema measurements in the upper and lower eyelids decreased significantly in the group that received steroids compared to placebo on postoperative day 1: (0.85 versus 1.61, P value 0.003; and 1.19 versus 1.92, P value 0.002, respectively), and on day four (0.31 versus 1.14, P value < 0.001; and 0.85 versus 1.33, P value 0.03). On day 7, the oedema in the upper eyelid continued to be diminished in the steroids group, but not to a statistically significant degree, while the oedema in the lower eyelid had nearly equalised.

Kara 1999 reported this outcome through graphs, which made it impossible to extract data for analysis. The eyelid oedema in the steroid groups was significantly lower than that in the placebo group on the first and second postoperative days. On day 2, the oedema increased in the steroid groups and decreased in the placebo group. The trial authors concluded that use of a single dose of 10 mg of dexamethasone intraoperatively in rhinoplasty procedures had a significant effect on decreasing upper and lower eyelid oedema over the first two postoperative days, in comparison with a placebo. However, the effect of the dexamethasone was lost after the first two days.

Kargi 2003 also reported this outcome through graphs. The trial authors reported that there was no significant difference between the groups that received corticosteroids one hour before the operation and the groups that received it at the beginning of the operation. When administration of different corticosteroid doses was compared with placebo, oedema was found to be reduced in all the steroid groups during the first two postoperative days (P value <0.05). When a single dose was compared with triple‐dose administration, the latter was found to be more effective in decreasing oedema during the first five to seven days (P value<0.05) There was no significant difference between any of the groups by day 10.

Koc 2011 reported the results using medians and interquartile ranges which precluded inclusion of this trial in the meta‐analysis. In the groups that received the steroid preoperatively (1 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg), periorbital oedema and ecchymosis were significantly lower than in the control group (P value < 0.05) on days 1, 3 and 7. No significant differences were seen clinically or statistically with regard to prevention or reduction of the periorbital oedema between the two corticosteroid groups.

Totonchi 2007 used another type of scale to rate the degree of swelling, and provided insufficient data for meta‐analysis. The corticosteroid group presented significantly less oedema than was seen in the control group two days after surgery (mean 1.02 versus 1.96, P value < 0.001). This difference was no longer significant on day 8 (mean 0.08 versus 0.25, P value 0.25).

Facelift surgery

Just one study compared steroids (500 mg methylprednisolone IV followed with 6 days orally ) with placebo in facelift surgery. Owsley 1996 did not observe any statistically significant difference between the groups on days 1, 4, 6 or 10, regarding facial oedema measured on a scale of 1 to 4 (where 1 was the minimum and 4 the maximum) (day1: means of 3.2 versus 3.1, day 4 or 6: 2.3 versus 2.3 and day 10: 1.6 versus 1.5, P value > 0.4) . These authors did not report any other outcomes.

Ecchymosis (bruising)

Rhinoplasty

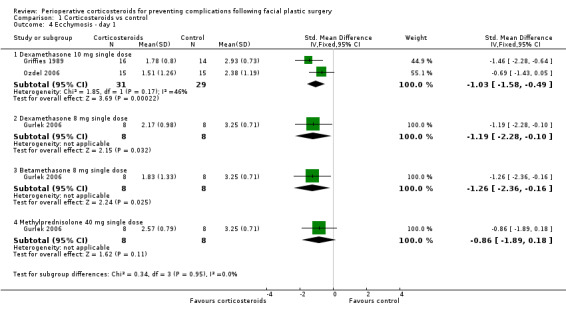

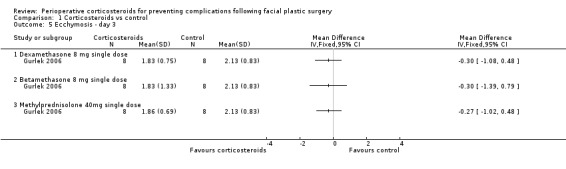

In the evaluations of ecchymosis, two studies compared a single preoperative 10 mg dose of dexamethasone with a control (Griffies 1989; Ozdel 2006). On the first postoperative day, there was a significant difference favouring the corticosteroid group (SMD ‐1.03, 95% CI ‐1.58 to ‐0.49) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 46%, P value 0.17). Gurlek 2006 observed a significant difference only on the first postoperative day, between dexamethasone (SMD ‐1.19, 95% CI ‐2.28 to ‐0.10) and placebo or betamethasone 8 mg (SMD ‐1.26, 95% CI ‐2.36 to ‐0.16) and placebo. On days 3 and 7, there was no significant difference between the intervention and placebo groups (Analysis 1.4; Analysis 1.5; Analysis 1.6)

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids vs control, Outcome 4 Ecchymosis ‐ day 1.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids vs control, Outcome 5 Ecchymosis ‐ day 3.

1.6. Analysis.

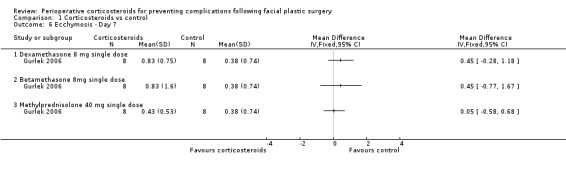

Comparison 1 Corticosteroids vs control, Outcome 6 Ecchymosis ‐ Day 7.

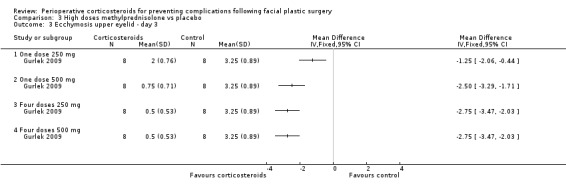

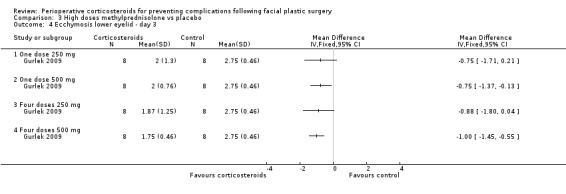

Gurlek 2009 compared four high doses of methylprednisolone preoperatively (one dose of 250 mg or 500 mg, or four doses of 250 mg or 500 mg) with placebo. Overall there were significant reductions in the extent of ecchymosis with corticosteroid treatment seen on days 1, 3 and 7 (P value<0.05) mainly with the last two high doses, that is, four doses of 250 mg or 500 mg (Analysis 3.1; Analysis 3.2; Analysis 3.3; Analysis 3.4; Analysis 3.5; Analysis 3.6).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo, Outcome 1 Ecchymosis upper eyelid ‐ day 1.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo, Outcome 2 Ecchymosis lower eyelid ‐ day 1.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo, Outcome 3 Ecchymosis upper eyelid ‐ day 3.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo, Outcome 4 Ecchymosis lower eyelid ‐ day 3.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo, Outcome 5 Ecchymosis upper eyelid ‐ day 7.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo, Outcome 6 Ecchymosis lower eyelid ‐ day 7.

In Hoffmann 1991 an early trend toward diminished postoperative ecchymosis was noted in the corticosteroid group, but this was not statistically significant on day 1 (1.39 versus 1.83, P value 0.15), day 4 (1.61 versus 2.02, P value 0.15) or day 7 (1.54 versus 1.18, P value 0.24).

In Kara 1999 the authors observed a statistically significant difference in upper eyelid ecchymosis in the first two days for both the preoperative and postoperative steroid groups (dexamethasone 10 mg) versus the placebo group (P value < 0.05), but steroid administration had no influence on ecchymosis of the lower eyelid (results in graphs).

Kargi 2003 compared different corticosteroid dose administrations with placebo, and found reduced ecchymosis in all the steroid groups during the first two days. Administration of a triple‐dose was more effective at decreasing ecchymosis during the first five to seven days than a single dose. There was no significant difference between any of the groups by day 10 (results in graphs).

Koc 2011 reported results using medians and interquartile ranges. Periorbital ecchymosis was significantly lower in groups using 1 mg/kg or 3 mg/kg methylprednisolone preoperatively than in the control group (P value < 0.05) on days 1, 3 and 7, with no significant difference observed between corticosteroid groups.

In Totonchi 2007, on postoperative day 2, there were no significant differences in the ratings of extent or intensity of ecchymosis between the steroid group (10 mg dexamethasone) and the control group. On postoperative day 8, the corticosteroid group demonstrated a significantly greater extent of ecchymosis (2.73 versus 2.17, P value < 0.05) and a higher intensity of ecchymosis (1.85 versus 1.02, P value < 0.01) compared with the control group.

Facelift surgery

The only study that compared administration of corticosteroids to placebo in relation to facelift surgery did not report this outcome (Owsley 1996).

Adverse events

Most studies did not report whether there were any adverse effects or complications. In four studies (Griffies 1989; Gurlek 2006; Gurlek 2009; Kargi 2003), the authors stated that no adverse effects were observed. In Hoffmann 1991 one participant in the corticosteroid group experienced gastrointestinal bleeding due to gastritis and five participants experienced postoperative wound infection; one in the corticosteroid group (4.2%) and four in the control group (16%).

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review included 10 trials that addressed two outcomes of interest to the review, namely, swelling and bruising. Nine of the studies were on rhinoplasty, and used several types and doses of corticosteroids. There was some evidence that a single preoperative dose of 10 mg dexamethasone decreased oedema and ecchymosis over the first two postoperative days; this difference was not observed after this period The clinical importance of this small difference in the first days after surgery cannot be established. No study reported cosmetic results in the medium‐term or long‐term, or information about quality of life or patient satisfaction.

There was some evidence that high doses of methylprednisolone (greater than 250 mg) decreased both ecchymosis and oedema observed on postoperative days 1, 3 and 7. No evidence was presented regarding pain, time taken to achieve healing, or quality of life, and the data were insufficient to reach any conclusion about the safety of the intervention.

Only one of the included studies evaluated the use of steroids in facelift surgery. This study had a small sample size (30 participants), and the authors did not find any difference in postoperative oedema, which was the only outcome assessed.

Questions about the safety of corticosteroids in facial plastic surgery remain unanswered. Five of the ten included studies did not report on adverse effects, four studies reported they had not observed any adverse effects and only one study reported events appropriately. This study reported one instance of gastric bleeding, and one of wound infection in the intervention group, and three cases of infection in the control group.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Although corticosteroids have been used in facial plastic surgery for decades (Ofo 2006), the published trials provide little evidence regarding their efficacy and safety. With the exception of studies on rhinoplasty and a single study on facelifts, we found no studies involving other facial surgical procedures. Moreover, important outcomes, such as pain, quality of life and time taken to achieve healing, were not evaluated in the studies included in this review. For any type of intervention, the risks and benefits need to be compared. Although administration of a single dose of corticosteroid may offer little risk, the paucity of available evidence means that risk cannot be ruled out. In addition, there are uncertainties regarding the clinical importance of the effect of the intervention, since the outcomes have not been adequately evaluated, and the benefits, if there were any, were apparent only on the first days of the postoperative period.

Quality of the evidence

Although ten studies were included, all of them had small sample sizes and presented an unclear risk of bias. No high‐quality studies were included. Furthermore, the included studies used many different steroid preparations and dosage schedules, and did not use a validated instrument for measuring the swelling and bruising. The authors presented their results in different forms, and, in some studies, only graphically. All of these factors together made it impossible to carry out a comprehensive meta‐analysis.

Potential biases in the review process

We conducted an extensive literature search without language restrictions. Therefore, we believe that it is unlikely that any studies with the potential for inclusion will have been missed, and we believe that there was no significant bias in the review process.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The results from this systematic review are consistent with those of two other systematic reviews that have been published on the use of steroids in rhinoplasty, even though our conclusions differ. One of the reviews located seven studies and included four in a meta‐analysis (Hatef 2011), it concluded that perioperative steroid use decreased postoperative oedema and ecchymosis associated with rhinoplasty. The other review included four studies and concluded that corticosteroids reduced periorbital oedema postoperatively (Youssef 2013), especially over the first three days, but that they had little effect after the third day.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is limited evidence that in rhinoplasty a single perioperative dose of corticosteroids decreases formation of oedema and ecchymosis over the first two days following surgery, but the difference is not observed after this period. There is limited evidence that high doses of corticosteroids decrease both ecchymosis and oedema between the first and seventh days after rhinoplasty. The clinical significance of this decrease is unknown, since the relevant trials did not report clinical outcomes such as patients satisfaction and quality of life. There is limited evidence regarding the safety of this intervention. Therefore, the evidence currently available does not support use of corticosteroids for preventing complications following facial plastic surgery.

Implications for research.

Further randomised trials with adequate methodology, standardised dosing and assessment of outcomes using validated instruments are needed. Studies should address the various types of facial plastic surgery separately, with long‐term follow‐up, and describe outcomes such as adverse effects, time to healing of wounds and patient satisfaction. There is a need to develop standardised and validated instruments for assessing oedema and ecchymosis.

Notes

It is with regret that we have to inform the readers of this review that Professor Bernardo S Hochman has passed away. However he had contributed significantly to this review and we have respectfully continued to include him as an author.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Cochrane Wounds Group Editors (Julie Bruce, Liz McInnes, Gill Worthy), the peer referees (Richard Baker, Bryan Chung and Chris Munson) and the copy editor (Jenny Bellorini) for their contribution. We would particularly like to acknowledge the help and support of Sally Bell‐Syer of the Cochrane Wounds Group.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase and EBSCO CINAHL

Ovid MEDLINE

1 exp Face/ (115903) 2 exp Facial Injuries/ (34945) 3 exp Ear/ (84237) 4 (face or facial or nose*1 or mouth*1 or ear*1 or lip*1).tw. (320590) 5 or/1‐4 (474758) 6 exp Surgery, Plastic/ (22501) 7 (plastic surg* or reconstructive surg*).tw. (22238) 8 or/6‐7 (39209) 9 5 and 8 (10727) 10 ((facial adj5 surgery) or (craniofacial adj5 surgery) or face lift* or face‐lift*).tw. (5380) 11 or/9‐10 (14767) 12 exp Adrenal Cortex Hormones/ (329363) 13 (corticosteroid* or corticoid* or glucocorticoid* or steroid*).tw. (270321) 14 (dexamethasone or methylprednisolone).tw. (52025) 15 or/12‐14 (495880) 16 11 and 15 (127) 17 randomized controlled trial.pt. (359010) 18 controlled clinical trial.pt. (86881) 19 randomized.ab. (260290) 20 placebo.ab. (141107) 21 clinical trials as topic.sh. (166531) 22 randomly.ab. (186021) 23 trial.ti. (111455) 24 or/17‐23 (827068) 25 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (3865236) 26 24 not 25 (759681) 27 16 and 26 (17)

Ovid Embase

1 exp FACE/ (74336) 2 exp face injury/ (50591) 3 exp EAR/ (92690) 4 (face or facial or nose*1 or mouth*1 or ear*1 or lip*1).tw. (434010) 5 or/1‐4 (564729) 6 exp plastic surgery/ (203566) 7 (plastic surg* or reconstructive surg*).tw. (34469) 8 or/6‐7 (217117) 9 5 and 8 (40017) 10 ((facial adj5 surgery) or (craniofacial adj5 surgery) or face lift* or face‐lift*).tw. (7086) 11 or/9‐10 (43484) 12 exp CORTICOSTEROID/ (725138) 13 exp corticosteroid therapy/ (27312) 14 (corticosteroid* or corticoid* or glucocorticoid* or steroid*).tw. (377568) 15 (dexamethasone or methylprednisolone).tw. (70258) 16 or/12‐15 (918222) 17 11 and 16 (1076) 18 Randomized controlled trials/ (45343) 19 Single‐Blind Method/ (18854) 20 Double‐Blind Method/ (122319) 21 Crossover Procedure/ (39619) 22 (random$ or factorial$ or crossover$ or cross over$ or cross‐over$ or placebo$ or assign$ or allocat$ or volunteer$).ti,ab. (1342535) 23 (doubl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. (150163) 24 (singl$ adj blind$).ti,ab. (14626) 25 or/18‐24 (1408770) 26 exp animals/ or exp invertebrate/ or animal experiment/ or animal model/ or animal tissue/ or animal cell/ or nonhuman/ (20920497) 27 human/ or human cell/ (15259115) 28 and/26‐27 (15212456) 29 26 not 28 (5708041) 30 25 not 29 (1216932) 31 17 and 30 (59) 32 (2012* or 2013* or 2014*).em. (2973868) 33 31 and 32 (14)

EBSCO CINAHL

S29S16 AND S28 S28S17 or S18 or S19 or S20 or S21 or S22 or S23 or S24 or S25 or S26 or S27 S27TX allocat* random* S26(MH "Quantitative Studies") S25(MH "Placebos") S24TX placebo* S23TX random* allocat* S22(MH "Random Assignment") S21TX randomi* control* trial* S20TX ( (singl* n1 blind*) or (singl* n1 mask*) ) or TX ( (doubl* n1 blind*) or (doubl* n1 mask*) ) or TX ( (tripl* n1 blind*) or (tripl* n1 mask*) ) or TX ( (trebl* n1 blind*) or (trebl* n1 mask*) ) S19TX clinic* n1 trial* S18PT Clinical trial S17(MH "Clinical Trials+") S16S11 and S15 S15S12 or S13 or S14 S14TI ( dexamethasone or methylprednisolone ) or AB ( dexamethasone or methylprednisolone ) S13TI ( corticosteroid* or corticoid* or glucocorticoid* or steroid* ) or AB ( corticosteroid* or corticoid* or glucocorticoid* or steroid* ) S12(MH "Adrenal Cortex Hormones+") S11S9 or S10 S10TI ( (facial N5 surgery) or (craniofacial N5 surgery) or face lift* or face‐lift* or facelift* ) or AB ( (facial N5 surgery) or (craniofacial N5 surgery) or face lift* or face‐lift* or facelift* ) S9S5 and S8 S8S6 or S7 S7TI ( plastic surg* or reconstructive surg* ) or AB ( plastic surg* or reconstructive surg* ) S6(MH "Surgery, Plastic+") S5S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 S4TI ( face or facial or nose* or mouth* or ear* or lip* ) or AB ( face or facial or nose* or mouth* or ear* or lip* ) S3(MH "Ear+") S2(MH "Facial Injuries+") S1(MH "Face+")

Appendix 2. Criteria for judgements for risk of bias

1. Was the allocation sequence randomly generated?

Low risk of bias

The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as: referring to a random‐number table; using a computer random‐number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots.

High risk of bias

The investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process. Usually, the description would involve some systematic, non‐random approach, for example: sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; sequence generated by some rule based on date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by some rule based on hospital or clinic record number.

Unclear

Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias.

2. Was the treatment allocation adequately concealed?

Low risk of bias

Participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation: central allocation (including telephone, web‐based and pharmacy‐controlled randomisation); sequentially‐numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially‐numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes.

High risk of bias

Participants or investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments and thus introduce selection bias, such as allocation based on: using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially‐numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure.

Unclear

Insufficient information to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias. This is usually the case if the method of concealment is not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement, for example if the use of assignment envelopes is described, but it remains unclear whether envelopes were sequentially‐numbered, opaque and sealed.

3. Blinding ‐ was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Low risk of bias

Any one of the following.

No blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome and the outcome measurement are not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken.

Either participants or some key study personnel were not blinded, but outcome assessment was blinded and the non‐blinding of others unlikely to introduce bias.

High risk of bias

Any one of the following.

No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome or outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken.

Either participants or some key study personnel were not blinded, and the non‐blinding of others is likely to introduce bias.

Unclear

Either of the following.

Insufficient information to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias.

The study did not address this outcome.

4. Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

Low risk of bias

Any one of the following.

No missing outcome data.

Reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to introduce bias).

Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups.

For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with the observed event risk is not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate.

For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes is not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size.

Missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods.

High risk of bias

Any one of the following.

Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups.

For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk is enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate.

For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size.

‘As‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation.

Potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation.

Unclear

Either of the following.

Insufficient reporting of attrition/exclusions to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias (e.g. number randomised not stated, no reasons for missing data provided).

The study did not address this outcome.

5. Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Low risk of bias

Either of the following.

The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way.

The study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon).

High risk of bias

Any one of the following.

Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported.

One or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. sub scales) that were not pre‐specified.

One or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect).

One or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis.

The study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study.

Unclear

Insufficient information provided to permit a judgement of low or high risk of bias. It is likely that the majority of studies will fall into this category.

6. Other sources of potential bias

Low risk of bias

The study appears to be free of other sources of bias.

High risk of bias

There is at least one important risk of bias. For example, the study:

had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; or

had extreme baseline imbalance; or

has been claimed to have been fraudulent; or

had some other problem.

Unclear

There may be a risk of bias, but there is either:

insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; or

insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Corticosteroids vs control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Oedema ‐ day 1 | 3 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Dexamethasone 10 mg single dose | 2 | 60 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.16 [‐1.71, ‐0.61] |

| 1.2 Dexamethasone 8 mg single dose | 1 | 16 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.30 [‐1.29, 0.68] |

| 1.3 Betamethasone 8 mg single dose | 1 | 16 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.93 [‐1.98, 0.12] |

| 1.4 Methylprednisolone 40 mg single dose | 1 | 16 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.08 [‐2.15, ‐0.01] |

| 2 Oedema ‐ day 3 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 Dexamethasone 8 mg single dose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 Betamethasone 8 mg single dose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Methylprednisolone 40 mg single dose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Oedema ‐ day 7 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Dexamethasone 8 mg single dose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Betamethasone 8 mg single dose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Methylprednisolone 40 mg single dose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Ecchymosis ‐ day 1 | 3 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Dexamethasone 10 mg single dose | 2 | 60 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.03 [‐1.58, ‐0.49] |

| 4.2 Dexamethasone 8 mg single dose | 1 | 16 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.19 [‐2.28, ‐0.10] |

| 4.3 Betamethasone 8 mg single dose | 1 | 16 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.26 [‐2.36, ‐0.16] |

| 4.4 Methylprednisolone 40 mg single dose | 1 | 16 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.86 [‐1.89, 0.18] |

| 5 Ecchymosis ‐ day 3 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 Dexamethasone 8 mg single dose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 Betamethasone 8 mg single dose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.3 Methylprednisolone 40mg single dose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Ecchymosis ‐ Day 7 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 Dexamethasone 8 mg single dose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.2 Betamethasone 8mg single dose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.3 Methylprednisolone 40 mg single dose | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 2. High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Oedema upper eyelid ‐ day 1 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 One dose 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 One dose 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Four doses 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Four doses 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Oedema lower eyelid ‐ day 1 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 One dose 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 One dose 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Four doses 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.4 Four doses 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Oedema upper eyelid ‐ day 3 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 One dose 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 One dose 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Four doses 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.4 Four doses 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Oedema lower eyelid ‐ day 3 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 One dose 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 One dose 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Four doses 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.4 Four doses 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Oedema upper eyelid ‐ day 7 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 One dose 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 One dose 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.3 Four doses 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.4 Four doses 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Oedema lower eyelid ‐ day 7 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 One dose 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.2 One dose 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.3 Four doses 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.4 Four doses 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 3. High doses methylprednisolone vs placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Ecchymosis upper eyelid ‐ day 1 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 1.1 One dose 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.2 One dose 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.3 Four doses 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 1.4 Four doses 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2 Ecchymosis lower eyelid ‐ day 1 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2.1 One dose 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.2 One dose 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.3 Four doses 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 2.4 Four doses 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3 Ecchymosis upper eyelid ‐ day 3 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 One dose 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 One dose 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 Four doses 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.4 Four doses 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Ecchymosis lower eyelid ‐ day 3 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 One dose 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 One dose 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 Four doses 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.4 Four doses 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Ecchymosis upper eyelid ‐ day 7 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 One dose 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 One dose 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.3 Four doses 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.4 Four doses 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 Ecchymosis lower eyelid ‐ day 7 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6.1 One dose 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.2 One dose 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.3 Four doses 250 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6.4 Four doses 500 mg | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Griffies 1989.

| Methods | Prospective, double‐blind, randomised pilot study. Single centre ‐ USA | |

| Participants | 30 participants undergoing rhinoplasty with osteotomies: 7 women and 23 men; age range 18‐45 years | |

| Interventions | 2 groups: 10 mg dexamethasone IV before operation vs placebo | |

| Outcomes | Periorbital oedema and ecchymosis at 24 h, measured by 4‐point scale | |

| Notes | 1 outcome observer | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Dropout rates were not reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes described |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Gurlek 2006.

| Methods | A double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled trial. Single centre ‐ Turkey | |

| Participants | 40 participants undergoing rhinoplasty with osteotomies: no information about gender distribution; age range 22‐30 years | |

| Interventions | 5 groups: betamethasone 8 mg (n = 8); dexamethasone 8 mg (n = 8); methylprednisolone 40 mg (n = 8); tenoxicam 20 mg (n = 8); or placebo (n = 8) for 3 days | |

| Outcomes | Ecchymosis and oedema, measured by 4‐point scale on days 1, 3 and 7 | |

| Notes | 3 observers assessed the outcome independently | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Dropout rates were not reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes described |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Gurlek 2009.

| Methods | A double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled trial. Single centre ‐ Turkey | |

| Participants | 40 participants undergoing open rhinoplasty with osteotomy: 14 women and 26 men; mean age 24.5 years (range 19‐35 years) | |

| Interventions | Participants were randomly divided into 5 groups (8 participants each) and treated as follows: Group 1: a single dose of 250 mg methylprednisolone Group 2: a single dose of 500 mg methylprednisolone Group 3: 4 doses of 250 mg methylprednisolone Group 4: 4 doses of 500 mg methylprednisolone Group 5: placebo |

|

| Outcomes | Ecchymosis and oedema, measured by 4‐point scale on days 1, 3 and 7 | |

| Notes | 3 observers assessed the outcome independently | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Dropout rates were not reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes described |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Hoffmann 1991.

| Methods | A double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled trial. Single centre ‐ USA | |

| Participants | 49 participants undergoing rhinoplasty: no information about gender distribution; age range 15‐70 years | |

| Interventions | 2 groups: a single dose of 10 mg dexamethasone IV plus 50 mg oral prednisone on the first postoperative day, tapering 10 mg/day in five days (i.e.:40 mg,30 mg,20 mg, 10mg)(n = 24); or placebo (n = 25) | |

| Outcomes | Ecchymosis and oedema, measured by 4‐point scale on days 1, 4 and 7 | |

| Notes | 2 observers assessed the outcome independently | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Dropout rates were not reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes described |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Kara 1999.

| Methods | Double‐blind, randomised trial with placebo control. Single centre ‐ Turkey | |

| Participants | 55 participants undergoing rhinoplasty: 35 women and 20 men Mean age: preoperative corticosteroid group = 23.2 ± 1.8 years; postoperative corticosteroid group = 22.7 ± 1.5 years; placebo group = 25.2 ± 1.3 years |

|

| Interventions | 3 groups: Preoperative corticosteroid group: 10 mg dexamethasone given IV just before surgery (n = 18) Postoperative corticosteroid group: 10 mg dexamethasone given IV at the end of surgery (n = 20) Placebo group: saline given preoperatively or postoperatively (n = 17) |

|

| Outcomes | Intraoperative blood loss was recorded for each participant. Postoperative scoring of eyelid swelling and ecchymosis began after approximately 24 h and lasted into postoperative day 9. Ecchymosis and oedema were measured by a 4‐point scale | |

| Notes | 2 observers assessed the outcomes independently | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding (performance bias and detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double‐blinded |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Dropout rates were not reported |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | All outcomes reported |

| Other bias | Low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias |

Kargi 2003.

| Methods | Double‐blind, randomised study with placebo control. Single centre ‐ Turkey | |

| Participants | 60 participants undergoing rhinoplasty: sex distribution and age not reported | |