Abstract

Objective:

This article describes the methodology used for The Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference (PALICC-2) which sought to develop evidence-based clinical recommendations and when evidence was lacking, expert-based consensus statements and research priorities for the diagnosis and management of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (PARDS).

Data Sources:

Electronic searches were conducted using PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library (CENTRAL) databases from 2012 to March 2022.

Study Selection:

Content was divided into 11 sections related to PARDS, with abstract and full text screening followed by data extraction for studies which met inclusion with no exclusion criteria.

Data Extraction:

We used a standardized data extraction form to construct evidence tables, grade the evidence, and formulate recommendations or statements using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system.

Data Synthesis:

This consensus conference was comprised of a multi-disciplinary group of international experts in pediatric critical care, pulmonology, respiratory care and implementation science which followed standards set by the Institute of Medicine, using the GRADE system and Research And Development/University of California, Los Angeles (RAND/UCLA) appropriateness method, modeled after PALICC 2015. The panel of 52 content and 4 methodology experts had several web-based meetings over the course of two years. We conducted 7 systematic reviews and 4 scoping reviews to cover the 11 topic areas. Dissemination was via primary publication listing all statements, and separate supplemental publications for each subtopic that include supporting arguments for each recommendation and statement.

Conclusions:

A consensus conference of experts from around the world developed recommendations and consensus statements for the definition and management of PARDS and identified evidence gaps which need further research.

Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome, pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome, pediatric critical care, evidence-based medicine, consensus development conference

The Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference (PALICC-2) is an update of the consensus conference report published in 2015 (1). In the intervening years, several well designed observational and interventional studies have been conducted which have significantly improved our understanding of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (PARDS). The PALICC-2 update was designed to incorporate the new and emerging evidence and create comprehensive evidence-based recommendations, supplemented by consensus and good practice statements based on expert opinion where scientific evidence was lacking. PALICC-2 included an organized and structured conference series, with participation of international and multidisciplinary experts in PARDS. We describe here the process and methodology used in PALICC-2.

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

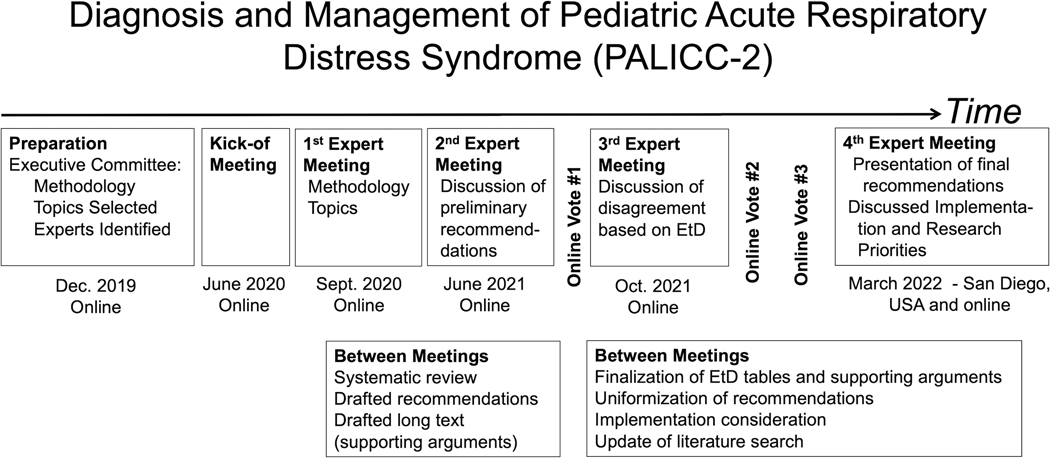

The design of the consensus conference was modeled after the first iteration of PALICC (2). Like PALICC, PALICC-2 is a Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI)-endorsed project. The executive committee of PALICC-2 was formed in 2020 and led by three co-chairs (R.K., G.E, and Y. L-F). PALICC-2 executive committee membership was extended to two methodologists (N.I. and M.M.B.). The roles of the executive committee included: pursuing funding and endorsement by scientific and professional societies, refining and updating PALICC methodology, selecting new topics, identifying topic experts, organizing virtual and in-person meetings, overseeing the systematic review and grading of evidence process, developing the tools needed for project completion (e.g., electronic data collection forms, electronic surveys), overseeing and maintaining a schedule for the modified Delphi process and for manuscript drafting, and coordinating dissemination of the PALICC-2 recommendations through multiple outlets. The timeline for the guideline activities is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline and overview of the updated international guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (PALICC-2)

RAND/UCLA= Research And Development/University of California, Los Angeles

EXPERT PANEL COMPOSITION

The 27 original PALICC members were invited to participate in PALICC-2. Three declined due to time constraints or a change in research focus, and 28 new panelists were identified based on their record of peer reviewed publications on the topic of interest. Additional consideration was given to ensure representation from all continents, including regions where practitioners work in medical resource-limited settings (RLS). The final expert panel was composed of 52 panel and 4 methodology experts (24 women, 32 men) from multiple disciplines (52 physicians, 1 respiratory therapist, 1 nurse, 1 physical therapist, 1 PhD researcher) and geographic settings (15 countries, including six from low/middle income and health resource limited countries). The final panel also included two implementation science experts (K.S and R.B). Expert panel members conducted within-group work (i.e., completing the systematic review of the literature for each assigned topic, completing evidence tables, drafting supporting arguments for each recommendation using the Evidence-to-Decision [EtD] framework), as well as between-group work (i.e., reviewing, discussing, and voting on all recommendations put forth by all groups). To improve the generalizability of the recommendations, one expert from the RLS group participated in the work of each group as a liaison, unless the group experts already included at least one regional expert with experience in a RLS. The panel discussed including patient representatives in the guideline. However, finding disease specific and widely representative patient/parent panel members proved to be difficult and impractical within the constraints of the guideline development process. Panel members, therefore, relied on the published literature on what outcomes are important to parents of critically ill children (3).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST MANAGEMENT AND SPONSORSHIP

Expert panel members were asked to disclose any conflicts of interest (COI) before the start of the systematic reviews, during the voting process, and at the time of journal submission. If a COI was identified for a specific topic, that panel member was removed from the voting pool for that topic. All funding for PALICC-2 was from authors’ institutions; no aspect of the work conducted was sponsored by a commercial entity. Expert panel members and medical librarians conducted all work voluntarily, with no compensation.

FORMULATING CLINICAL QUESTIONS

The committee used expert opinion to identify clinical questions of importance to patients at risk for or with PARDS, their caregivers, and clinicians who care for such children. Outcomes to be considered in the guideline were developed using a modified Delphi process with one round of discussion and voting. A list of outcomes of interest for each of the clinical questions was created by surveying the panel. Outcomes were then rated as “critical”, “important”, or “less important” on a scale from 1 to 9 (4). During this rating process the panelists were considering the importance of outcomes in PARDS. Panelists were able to add or edit the list of outcomes for specific interventions. For example, outcomes that are used for decision making are likely to be different when considering monitoring strategies compared to the outcomes considered when deciding whether to initiate ECMO. Outcome rating was informed by the recently published core outcome set in pediatric critical care and there was significant overlap between the core outcome set and the outcomes rated as critical/important (3). As suggested by the GRADE method, only outcomes that were considered ‘critical’ or ‘important’ were considered while formulating the recommendations (Table 1).

Table 1.

PALICC-2 Outcome Priorities

| PALICC-2 Outcome Priorities | |

|---|---|

|

Critical (Median score 7–9 on Liker scale) |

Mortality Ventilator-Free Days |

|

Important (Median score 5–7 on Liker scale) |

Functional Status New or progressive non-pulmonary organ dysfunction Health Related Quality of Life Neurocognitive function Length of mechanical ventilation New morbidity or technology dependence |

|

Less important

(Median score 1–3 on Liker scale) |

Improvement in Oxygenation Need for non-conventional therapies (iNO, HFOV, ECMO) Duration of oxygen therapy Extubation failure Need for tracheostomy Sedative exposure Adverse events: barotrauma Adverse events: cardiac arrest Adverse events: nosocomial infections Ventilator-induced respiratory muscle weakness ICU acquired weakness ECMO/ECLS Limitation of life sustaining measures (withdrawal/withholding therapy) ICU Length of Stay Hospital Length of Stay PICU readmissions Pulmonary function Nutrition status and growth Health-care costs Family outcomes (financial, psychological, resource use). |

The panel selected a list of relevant outcomes using a Likert scale from 1 (not important) to 9 (critical). Only outcomes in the “Critical” or “Important” categories were considered. Each subgroup was also allowed to select 1–2 outcomes of interest specific to that topic even if they were rated as ‘less important’ during the first vote.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEWS

We set out to answer 11 key questions (KQ) that are shown in Table 2. Of note, KQ 10 and KQ 11 are new additions for PALICC-2. Scoping (as opposed to systematic) reviews were conducted for KQ1, KQ6, KQ9 and KQ11. We have used the guidance provided in the Cochrane handbook (5) and the criteria provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (6) to determine when to use scoping reviews as opposed to systematic reviews. We performed scoping reviews for reviews pertaining to the definition section and when there was no direct evidence after a literature review in which case we produced best practice statements, research statements and policy statements as applicable.

Table 2.

Key questions addressed in PALICC-2

| List of Key questions addressed in PALICC-2 |

|---|

| 1) How should PARDS be defined, and what are the variables that best characterize the global burden of PARDS? |

| 2) What are pediatric specific elements of the pathobiology of PARDS, and what is the association between pathobiology and severity, and risk stratification in PARDS? |

| 3) What is the effectiveness and comparative effectiveness of different ventilation strategies for children with PARDS? |

| 4) What is the effectiveness and comparative effectiveness of pulmonary-specific ancillary treatments in children with PARDS? |

| 5) What is the effectiveness and comparative effectiveness of non-pulmonary treatments in children with PARDS? |

| 6) What is the role of different monitoring strategies in patients with PARDS? |

| 7) What is the effectiveness of noninvasive ventilatory support in PARDS? |

| 8) What is the effectiveness of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in children with PARDS? |

| 9) What are the morbidity and long-term outcomes in PARDS? |

| 10) How can informatics, data science, and computerized decision support tools improve the diagnosis and management of PARDS? |

| 11) How should the recommendations for the diagnosis and management of PARDS be adapted to the context of RLS? |

We developed Patient/Intervention/Comparator/Outcome (PICO) questions specific to each topic, which are described in each of the papers in this supplement (7–17). While writing the manuscript, the authors reviewed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines for systematic reviews and scoping reviews, as applicable (18, 19). The protocol for the systematic reviews was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021236582).

We searched PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and/or CINAHL, as appropriate, from 2012 (last year of the PALICC literature search) to November-December 2020, with an update conducted in March-April 2022. The start dates for the newly added KQ10 and KQ11 were 1980 (reflective of the relatively new fields of informatics, data science and computerized decision support tools in medicine) and database inception, respectively. Electronic searches were conducted by medical librarians at the William H. Welch Medical Library, Baltimore, Maryland; the library of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine, Montreal, Canada; and the Health Sciences Library at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California. Different sections were assigned to different medical librarians and each search was completed by only one librarian. Search strategies, date ranges, and number of resulting citations are detailed in the supplemental materials in the individual manuscripts.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported original data collected from critically ill patients less than 18 years old, with PARDS or at risk for PARDS, evaluated an exposure or intervention specific to each topic, and assessed an outcome. Such outcomes included mortality, ventilator-free days, length of mechanical ventilation, functional status, health-related quality of life, new or progressive (non-pulmonary) organ failure, neurocognitive function, and new morbidity or technology dependence. Patients with PARDS or at risk for PARDS were classified using the 2015 PALICC definition (1), the 2012 Berlin definition (20), or the 1994 American-European Consensus Conference (AECC) definition of (P)ARDS (21).

Studies were excluded if the study population consisted of infants born preterm (<37 weeks gestation) or adults (all participants ≥18 years of age, or mixed pediatric and adult population with inability to separate data for patients <18 years). Other exclusion criteria included: animal-only studies, not original data (e.g., reviews, editorials, commentaries, meeting proceedings), case reports or case series with sample size ≤10 participants, abstract-only, and non-English language publications with inability to determine eligibility. To explore new relevant concepts that remain underrepresented in contemporary pediatric literature related to the PARDS definition, ECMO and invasive mechanical ventilation, we reviewed meta-analyses and systematic reviews conducted in adult patients. Each of the corresponding manuscripts in this supplement specifically detail if adult data was used to inform any of the recommendations or statements.

Using the Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia), the studies were first screened by one expert based on titles and abstract, then two independent panelists reviewed full text articles. A third reviewer resolved differences at each stage. PRISMA flowcharts are presented for each systematic or scoping review. Key data elements were extracted from each study using an electronic form developed in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) browser (22) and exported into evidence tables. Studies included in the final reviews were evaluated for risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias 2 (RoB2) tool for RCTs (23) and the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool for non-randomized studies (24).

GRADING OF EVIDENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF RECOMMENDATIONS

We used GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool online software (McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) to develop evidence profiles for each PICO question (25–27). The evidence profiles summarized the quality of evidence and results for each outcome of importance. To pool quantitative data, where applicable, we performed meta-analysis using Review Manager software (RevMan), version 5.3 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). Where appropriate we performed a diagnostic test accuracy metanalysis (DTA) using the software OpenMeta[Analyst] (28).

When RCTs were available, only these were used to create the evidence profiles. Observational studies were used only when relevant outcome data were not available from RCTs (29–31). Evidence from non-randomized studies of interventions (NRSI) were considered ‘complimentary’ to evidence from RCTs if the information size from the randomized trials was thought to be sufficient. Evidence form NRSI were considered ‘sequential’ if evidence from RCTs was not available. This is especially the case for rates of adverse events which are often underreported in RCTs (32). Finally, evidence from the NRSI were considered ‘replacement’ if there were no RCTs on the topic or if the evidence from trials was very small or of poor quality due to high risk of bias (31).

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework to determine the certainty of evidence, defined as the degree of confidence that an estimate of the effect is correct, for each outcome (33). In the GRADE framework, evidence quality depends on overall risk of bias, precision, consistency, directness of the evidence, risk of publication bias, presence of dose-effect, magnitude of effect and the effect of plausible residual confounding. The certainty of evidence was categorized as high, moderate, low, or very low (Table 3). The overall certainty of evidence was determined across all outcomes considered critical or important for decision making (see Table 1).

Table 3.

Certainty of Evidence (Confidence in estimates) Grades (39)

| GRADE level | Definition |

|---|---|

| High | We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. |

| Moderate | We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different |

| Low | Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. |

| Very Low | We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect |

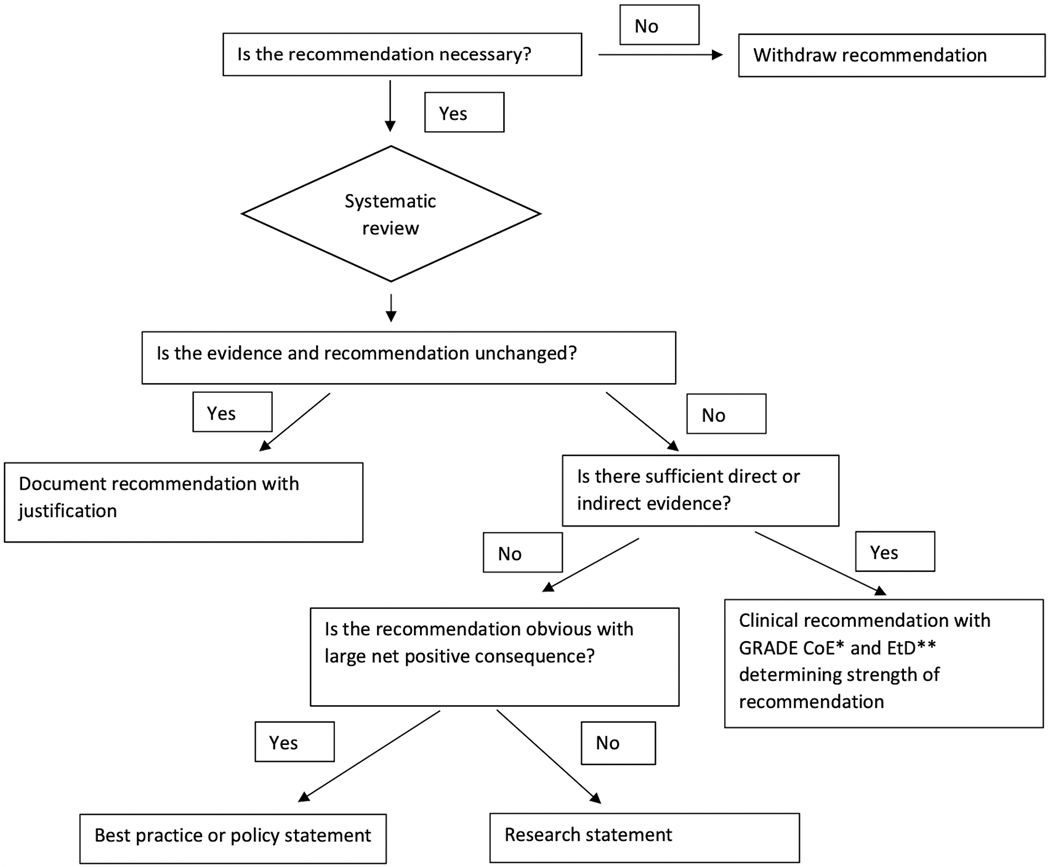

The process of forming a recommendation or statement began by reviewing the recommendations from the 2015 PALICC guideline publications. An initial vote was conducted on all 2015 PALICC recommendations to identify areas of highest controversy, as well as to allow panelists from all groups to suggest potentially new topic areas. All 2015 PALICC recommendations were updated either because of new evidence since 2015, or to comply with format changes for consistency in presentation. Recommendations that were outdated and potentially harmful if their implementation was continued were withdrawn (Figure 2), and several new recommendations and consensus-based statements were generated.

Figure 2.

PALICC-2 recommendation flowsheet

*CoE: Certainty of evidence

**EtD: Evidence to decision framework

Recommendations were described as ‘strong’ or ‘conditional’ (also referred to as ‘weak’) and the categorization was based on the GRADE EtD framework, which includes the following items: priority of the clinical problem, magnitude of the desirable effects, magnitude of the undesirable effects, overall certainty of the evidence, variability in patient values, the balance of desirable and undesirable effects of the intervention, resource/cost considerations, impact on equity, acceptability of the intervention, and feasibility of implementing the recommendation (34). The implications of the strength of recommendations for different stakeholders is provided in Table 4. In brief, a strong recommendation implies that the balance of benefits, harms, and other considerations in the EtD framework is such that the vast majority (>90%) of patients/families and providers would want the recommended course of action. A weak or conditional recommendation, on the other hand, implies that the balance of various considerations in the EtD framework still favors the recommended course of action in the majority (>50%) of patients/families. However, with a conditional recommendation, individual patient/family values or considerations of cost and feasibility may lead to a course of action other than that recommended in the guideline.

Table 4.

Implications of Strengths of Recommendations to Stakeholders

| Stakeholder | Strong Recommendation | Conditional Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | Vast majority of individuals/families in this situation would want the recommended course of action and only a small proportion would not. | The majority of individuals/families in this situation would want the suggested course of action, but many would not. |

| Clinicians | Most individuals/families should receive the recommended course of action. | Recognize that different choices will be appropriate for different patients and their families, and that you must help each patient arrive at a management decision consistent with her or his values and preferences. |

| Policy makers | The recommendation can be adapted as policy in most situations including for the use as performance indicators. | Policy making will require substantial debates and involvement of many stakeholders. Policies are also more likely to vary between regions. |

Proposals for recommendations, good practice statements, and consensus-based statements were developed by each group and presented to the large panel in a virtual meeting. Table 5 describes the different types of recommendations and statements the panel considered when reviewing the results of the systematic/scoping reviews. Each of these recommendations and statements were pooled and scored by the entire expert panel using the Research And Development/University of California, Los Angeles (RAND/UCLA) appropriateness scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree) (35). Scoring was conducted anonymously using an online tool (Qualtrics, Provo, Utah). Scores of 1, 2, and 3 represented disagreement; scores of 4, 5, and 6 represented equipoise; and scores of 7, 8, and 9 represented agreement. Comment areas were provided for each recommendation, to justify disagreement or equipoise. Recommendations that did not meet 90% agreement (score ≥ 7) were reviewed by subgroups and re-presented to the large panel in another web-based meeting. These recommendations were then re-submitted for voting in a second round. The same process was repeated after the second round of voting, again re-discussing recommendations that did not meet 90% agreement, prior to a third round of voting. The third round of voting also included any recommendation that was reworded or refined for clarity as part of the recommendation harmonization process. Agreement on the final recommendation/statement was defined a priori as ≥80% of the experts rating the recommendation a 7, 8, or 9.

Table 5:

Recommendation types used in the PALICC-2 guideline

| Recommendation type | Description | Method | Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical recommendations (CR) | Recommendations on clinical interventions and diagnostic tests. | GRADE framework, Consensus using UCLA-RAND system | Certainty of evidence, strength of recommendation |

| Good practice statements (GPS) | Absence of direct evidence but it is obvious that implementing the statement will result in a large net positive effect. | GRADE framework, Consensus using UCLA-RAND system | Ungraded, Good practice statements |

| Research statement (RS) | Inadequate evidence after a systematic review and where the panelists believed that any recommendation would be speculative. | Consensus using UCLA-RAND system | Ungraded, Research statement |

| Policy statements (PS) | Position on issues that pertain to bioethics, public health policy, health care finance and delivery and medical education/training. | Consensus using UCLA-RAND system | Ungraded, Policy statements |

| Definition statement (DS) | Offered in the context of updating the definition of pediatric ARDS. | Consensus using UCLA-RAND system | Ungraded, Definition statement |

We offered ‘good practice statements’ in the absence of direct evidence, using guidelines provided by GRADE, when it was clear that implementing such statements will result in large net positive effect (36). Good practice statements usually do not have any direct evidence, either because the statement may seem very obvious thereby making research in the topic a waste of resources or any research, especially an RCT, may be unethical or impractical to conduct (36). We have followed the convention of not rating the certainty of evidence for good practice statements and have labeled these statements as ‘Ungraded, Good practice statements’ (37).

For clinical topics about specific interventions where no direct or indirect evidence was found after a systematic review and where the panelists believed that any recommendation would be speculative, the panel has offered a ‘research statement’ calling for more research to be conducted on the topic.

We offered policy statements where the guideline panel is describing its position on issues that pertain to bioethics, public health policy, health care finance and delivery and medical education/training. Like the good practice statements, we did not expect such recommendations to have any direct evidence and therefore, these recommendations are also ‘ungraded’.

Definition statements were offered in the context of updating the definition of pediatric ARDS. Definition statements were primarily based on analysis of data from observational studies and clinical trials that described the impact of different variables on patient centered outcomes. Clinical attributes and indices that had a major impact on prognosis were used in formulating the definition of pediatric ARDS. For this we used the GRADE guidance on describing the certainty of evidence for prognostic studies (38, 39), although these statements are also ‘ungraded’. A summary of all types of recommendations and statements is provided in Table 5.

Experts in implementation science reviewed all recommendations and statements during the initial and subsequent meetings and provided suggestions to improve clarity with a lens of ensuring that the crafted recommendations and statements could unambiguously be implemented in clinical practice.

CONCLUSIONS

The publication of the PALICC PARDS definition and recommendations in 2015, along with identification of key areas of uncertainty, created a roadmap for research that has been used since then by investigators around the world (1). With the availability of new data published in the last seven years, PALICC-2 brought together a group of investigators, medical librarians, and methodologists, who updated the PALICC literature search, tackled novel concepts that have emerged since 2015, and updated the methodology to reflect contemporary guideline development processes, including systematic review of the literature and evidence profiles using the GRADE and evidence-to-decision framework methodology.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Katie Lobner, MLIS, Alix Pincivy, MSI, Philippe Dodin, MSI and Lynn Kysh, MLIS, MPP, for assisting with literature searches. We also thank the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators Network and the European Society of Pediatric and Neonatal intensive Care for their scientific support.

The Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference (PALICC-2) group members are listed in Appendix 1 (see Supplemental Digital File).

Footnotes

Copyright Form Disclosure: Dr. Emeriaud’s institution received funding from Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Santé and MAquet. Dr. Barbaro’s institution received funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01HL153519); he disclosed that he is the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) Registry Chair. Dr. Bembea’s institution received funding from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and a Grifols Investigator Sponsored Research Grant. Drs. Barbaro and Bembea received support for article research from the NIH. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

The Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference (PALICC-2) Group:

Guillaume Emeriaud, Yolanda M López-Fernández, Narayan Prabhu Iyer, Melania M Bembea, Asya Agulnik, Ryan P. Barbaro, Florent Baudin, Anoopindar Bhalla, Werther Brunow de Carvahlo, Christopher L Carroll, Ira M Cheifetz, Mohammod J Chisti, Pablo Cruces, Martha A.Q. Curley, Mary K Dahmer, Heidi J Dalton, Simon J Erickson, Sandrine Essouri, Analía Fernández, Heidi R Flori, Jocelyn R Grunwell, Philippe Jouvet, Elizabeth Y Killien, Martin CJ Kneyber, Sapna R Kudchadkar, Steven Kwasi Korang, Jan Hau Lee, Duncan J Macrae, Aline Maddux, Vicent Modesto i Alapont, Brenda Morrow, Vinay M Nadkarni, Natalie Napolitano, Christopher JL Newth, Martí Pons-Odena, Michael W Quasney, Prakadeshwari Rajapreyar, Jerome Rambaud, Adrienne G. Randolph, Peter Rimensberger, Courtney M. Rowan, L Nelson Sanchez-Pinto, Anil Sapru, Michael Sauthier, Steve L Shein, Lincoln S Smith, Katerine Steffen, Muneyuki Takeuchi, Neal J Thomas, Sze Man Tse, Stacey Valentine, Shan Ward, R Scott Watson, Nadir Yehya, Jerry J Zimmerman, and Robinder G Khemani

REFERENCES:

- 1.Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference G: Pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: consensus recommendations from the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2015; 16:428–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bembea MM, Jouvet P, Willson D, et al. : Methodology of the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2015; 16:S1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fink EL, Maddux AB, Pinto N, et al. A Core Outcome Set for Pediatric Critical Care. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(12):1819–1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. : What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2008; 336:995–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, J. C, M. C, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018; 18: 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yehya N, Smith L, Thomas NJ, et al. Definition, Incidence, and Epidemiology of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: From the second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med;XX(XX) :XX-XX [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Grunwell JR, Dahmer MK, Sapru A, et al. Pathobiology, Severity, and Risk Stratification of Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: From the Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med;XX(XX) :XX-XX [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Fernández A, Modesto V, Rimensberger PC, et al. Ventilatory Support in patients with Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: From the Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med;XX(XX) :XX-XX [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Rowan CM, Randolph AG, Iyer NP, et al. Pulmonary specific ancillary treatment for pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: From the second pediatric acute lung injury consensus conference . Pediatr Crit Care Med;XX(XX) :XX-XX [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Valentine S, Kudchadkar S, Ward S, et al. Non-Pulmonary Treatments for Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: From the Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference . Pediatr Crit Care Med;XX(XX) :XX-XX [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Bhalla A, Baudin F, Takeuchi M, et al. Monitoring in Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: From the Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference . Pediatr Crit Care Med;XX(XX) :XX-XX [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Carroll CL, Napolitano N, Pons-Òdena M, et al. Non-invasive respiratory support for Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: From the second pediatric acute lung injury consensus conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med;XX(XX) :XX-XX [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Rambaud J, Barbaro R, Macrae DJ, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome: From the second pediatric acute lung injury consensus conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med;XX(XX) :XX-XX [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Killien EK, Tse SM, Watson S, et al. Long-term Outcomes of Children with Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: From the Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med;XX(XX) :XX-XX [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Sanchez-Pinto, Sauthier M, Rajapreyar P, et al. Leveraging Clinical Informatics and Data Science to Improve Care and Facilitate Research in Pediatric Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: From the Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med;XX(XX) :XX-XX [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Morrow B, Agulnik A, Brunow de Carvahlo W, et al. Diagnostic, management, and research considerations for pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome in resource limited settings: From the second pediatric acute lung injury consensus conference. Pediatr Crit Care Med;XX(XX) :XX-XX [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. : Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009; 62:1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. : Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012; 307:2526–2533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. : The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 1994; 149:818–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. : Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42:377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, et al. : RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2019; 366:l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. : ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2016; 355:i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. : GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2011; 64:383–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schunemann HJ, Jaeschke R, Cook DJ, et al. : An official ATS statement: grading the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in ATS guidelines and recommendations. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2006; 174:605–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool McMaster University, 2015 (developed by Evidence Prime, Inc.), 2015. Available at gradepro.org. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wallace BC, Dahabreh IJ, Trikalinos TA, et al. : Closing the Gap between Methodologists and End-Users: R as a Computational Back-End. Journal of Statistical Software 2012; 49:1–15 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gershon AS, Lindenauer PK, Wilson KC, et al. : Informing Healthcare Decisions with Observational Research Assessing Causal Effect. An Official American Thoracic Society Research Statement. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2021; 203:14–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuello-Garcia CA, Morgan RL, Brozek J, et al. : A scoping review and survey provides the rationale, perceptions, and preferences for the integration of randomized and nonrandomized studies in evidence syntheses and GRADE assessments. J Clin Epidemiol 2018; 98:33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schunemann HJ, Tugwell P, Reeves BC, et al. : Non-randomized studies as a source of complementary, sequential or replacement evidence for randomized controlled trials in systematic reviews on the effects of interventions. Res Synth Methods 2013; 4:49–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qureshi R, Mayo-Wilson E, Li T: Summaries of harms in systematic reviews are unreliable Paper 1: An introduction to research on harms. J Clin Epidemiol 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Sultan S, et al. : GRADE guidelines: 11. Making an overall rating of confidence in effect estimates for a single outcome and for all outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol 2013; 66:151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alonso-Coello P, Oxman AD, Moberg J, et al. : GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: Clinical practice guidelines. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2016; 353:i2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, et al. : The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s Manual. Santa Monica, CA, RAND Corporation, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guyatt GH, Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ, et al. : Guideline panels should seldom make good practice statements: guidance from the GRADE Working Group. J Clin Epidemiol 2016; 80:3–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guyatt GH, Schunemann HJ, Djulbegovic B, et al. : Guideline panels should not GRADE good practice statements. J Clin Epidemiol 2015; 68:597–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iorio A, Spencer FA, Falavigna M, et al. : Use of GRADE for assessment of evidence about prognosis: rating confidence in estimates of event rates in broad categories of patients. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2015; 350:h870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Schunemann HJ, Brozek J, Guyatt G, et al. (Eds). The GRADE Working Group, 2013. Available at guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.