Abstract

Background

Ischaemic stroke can lead to many complications, but treatment options are limited. Icariin is a traditional Chinese medicine with reported neuroprotective effects against ischaemic cerebral injury; however, the underlying mechanisms by which icariin ameliorates cell apoptosis require further study.

Purpose

This study aimed to investigate the therapeutic potential of icariin after ischaemic stroke and the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Methods

N2a neuronal cells were used to create an in vitro oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) model. The effects of icariin on OGD cells were assessed using the CCK-8 kit to detect the survival of cells and based on the concentration, apoptosis markers, inflammation markers, and M2 pyruvate kinase isoenzyme (PKM2) expression were detected using western blotting, RT-qPCR, and flow cytometry. To investigate the underlying molecular mechanisms, we used the PKM2 agonist TEPP-46 and detected apoptosis-related proteins.

Results

We demonstrated that icariin alleviated OGD-induced apoptosis in vitro. The expression levels of the apoptosis marker proteins caspase-3 and Bax were upregulated and Bcl-2 was downregulated. Furthermore, icariin reduced inflammation and downregulated the expression of PKM2. Moreover, activation of the PKM2 by pretreatment with the PKM2 agonist TEPP-46 enhanced the effects on OGD induced cell apoptosis in vitro.

Conclusion

This study elucidated the underlying mechanism of PKM2 in OGD-induced cell apoptosis and highlighted the potential of icariin in the treatment of ischaemic stroke.

Keywords: Icariin, Neuron, Oxygen-glucose deprivation, Apoptosis, PKM2

Introduction

Ischaemic stroke is a leading cause of death and disability and has two characteristics: brain ischaemia and reperfusion-induced injuries (Peng et al., 2022). It is the most common type of stroke in the world. The current treatments for ischaemic stroke mainly involve intravenous and mechanical thrombolysis (Campbell et al., 2019). However, due to the narrow treatment window and the risk of bleeding, only less than 10 % of the patients with stroke are suitable for recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) treatment (Bhaskar et al., 2018). There is still a lack of effective neuroprotective agents.

Icariin (ICA) is the main bioactive flavonoid extracted from the herb Epimedii, a traditional Chinese medicine used to treat a variety of conditions, including osteoporosis and coronary heart disease (Ma et al., 2011, Yap et al., 2007, Pan et al., 2007). In recent years, many studies have shown that the ICA plays a protective role in the nervous system. By inhibiting the IRE1/XBP1s pathway, ICA might decrease the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-a in microglia to provide a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of brain injury after stroke (Mo et al., 2021). In an APP/PS1/Tau triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease, memory was improved when treated with ICA (de Almeida et al., 2023). ICA has a protective effect on the brain; however, the mechanism underlying this effect is unclear.

Pyruvate kinase (PK) is the key rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis. PK contains four isoenzymes and M2 pyruvate kinase (PKM2) is one of them (Liang et al., 2017). PKM2 is mainly expressed in rapidly proliferating cells such as embryos and tumours. In recent years, PKM2 has been shown to play an important role in apoptosis, activation of immune inflammation, and oxidative stress (Dhanesha et al., 2022). In a middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) mouse model, Jinyang Ren et al. found that the proportion of PKM2 in the ischaemic penumbral zone increased in the form of a tetramer. Inhibition of PKM2 activity can reduce infarct size and damage (Kong et al., 2023). Dhanesha et al. reported that PKM2 promoted the overactivation of neutrophils in a mouse model of cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion. Reduced infarct size and improved long-term outcomes have been observed in cerebral ischaemia-reperfusion mice with a PKM2 bone marrow knockout (Dhanesha et al., 2022).

The neuroprotective effect of ICA is well-known; however, its exact mechanism of action is not well understood and a correlation between ICA and PKM2 expression has not yet been reported. In this study, the effects of ICA on the apoptosis of oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) induced neurons and the expression of PKM2 were studied in vitro to determine whether ICA inhibits the apoptosis of OGD neurons by regulating the expression of PKM2.

Materials and methods

Materials

The icarrin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Cell counting kit-8 was purchased from YEOSEN (China). Antibodies against Bax, caspase-3, Bcl-2, and PKM2 were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Antibodies against GAPDH and β-actin were obtained from Cell Signalling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA), and secondary antibodies were obtained from Bioworld Biotechnology (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The TEPP-46 was purchased from Monmouth Junction (Waltham, MA, USA). PCR primers were synthesised at Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Cell culture

Mouse neuroblastoma N2a cell lines were obtained from the Cell Centre of the Institute of Basic Medicine, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and cultured in the dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10 % Foetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1 % Penicillin-Streptomycin (PS) in humidified air, with 5 % CO2 and at 37 °C.

Oxygen-glucose deprivation

The OGD model was applied to N2a neurons, as reported previously (Zhang et al., 2020). Briefly, the N2a cell culture medium was replaced with DMEM without glucose. Cells were cultured in a hypoxia chamber (Billups Rothenberg, Del Mar, CA, USA) with a gas mixture containing 95 % N2 and 5 % CO2 for 15 min. Valves were sealed, and the chambers were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. The cells were then transferred from the glucose-free medium to normal medium and cultured under normal conditions for another 24 h. Control cells were cultured in normal medium and environment at all times.

Cell counting assay

Cell viability was measured using the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 10 μl of CCK-8 solution was added to each well and incubated at 37 ℃ for 2.5 h in a 96-well plate, and the absorbance was then measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (TECAN Trading AG, Switzerland). The experiment was repeated thrice. Cell viability was calculated as follows:

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from N2a cells using a lysis buffer. A total of 100 μl lysate was added to each well of the 6-well plate and incubated on ice for 30 min and collected with a cell scraper. Then the lysate was centrifuged at 4 ℃ for 10 min. The protein concentrations were detected using a BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the separated proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) as previously described. After blocking for 2 h with 5 % non-fat milk at room temperature, the PVDF membranes were incubated with the corresponding primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C before being incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. The proteins were detected with the ECL Detection Kit (Millipore, Bedford, MA) and the images were captured by the Gel-Pro system (Tanon Technologies, Shanghai, China). The intensity of the blots was quantified by densitometry using ImageJ software.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from N2a cells using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription from RNA to cDNA was performed using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara, Dalian, China). Quantitative PCR was performed in a StepOne Plus PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA) using a SYBR green kit (Takara). The primers used were as follows:

| Primer | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | CCTCGTGCTGTCGGACCCATA | CAGGCTTGTGCTCTGCTTGTGA |

| IL-6 | ATGAACTCCTTCTCCACAAGC | CTACATTTGCCGAAGAGCCCTCAGGCTGGACTG |

| TNF-a | ATGAAATATACAAGTTATATG | TCCAGCTGCTCCTCCACTTG |

| Bax | AGGATGCGTCCACCAAGAAGCT | TCCGTGTCCACGTCAGCAATCA |

| Caspase-3 | GGTTCATCCAGTCCCTTTGC | AATTCCGTTGCCACCTTCCT |

| β-Actin | TCCAGCTGCTCCTCCACTTG | TCCAGCTGCTCCTCCACTTG |

| PKM2 | GCCGCCTGGACATTGACTC | CCATGAGAGAAATTCAGCCGAG |

Cell apoptosis

Cell apoptosis was measured using an Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/propidium iodide (PI) apoptosis kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. N2a cells were collected and washed twice with pre-cold PBS, and were then incubated with 100 μL binding buffer added with 5 μL Annexin V and 10 μL PI for 15 min in the dark at room temperature. Flow cytometry analysis was performed within 2 h.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad; USA) was used to plot the figures based on the data presented as mean ± SEM and for statistical analysis. Differences among the groups were tested by one-way ANOVA and t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

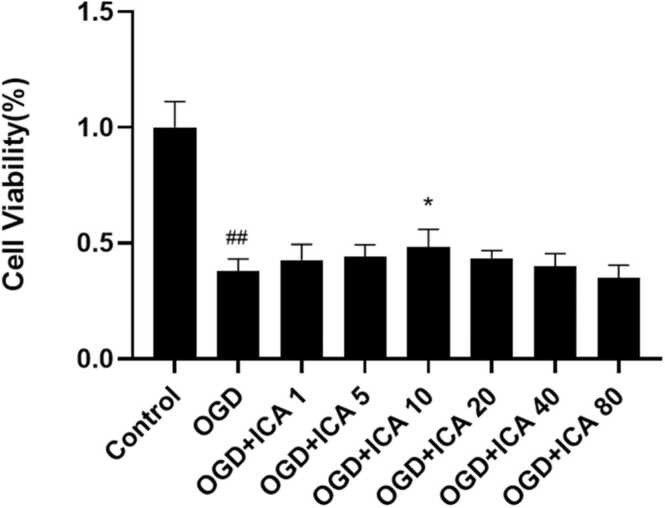

ICA reduced OGD-induced cell injury in N2a cells

To observe the effect of ICA on OGD-induced injury in vitro, N2a cells were treated with ICA in different concentrations, including 0, 1, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μM. A CCK-8 working solution was used to test the viability of N2a cells, and we found the highest value of ICA at a concentration of 10 μM. Moreover, ICA significantly enhanced neuronal viability and suppressed neuronal mortality in a dose-dependent manner compared with the OGD group (P < 0.05). In summary, ICA protected neurons from OGD-induced injury in vitro (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

ICA protects against OGD-induced neuronal injury in vitro. Neurons were treated with different concentrations of ICA (1, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μM) during the period of OGD and reperfusion; cell viability was detected with the CCK-8 assay. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The experiment was repeated thrice. ## P < 0.01, vs. control group; *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, vs. OGD group; *** P < 0.05, vs. OGD + ICA group.

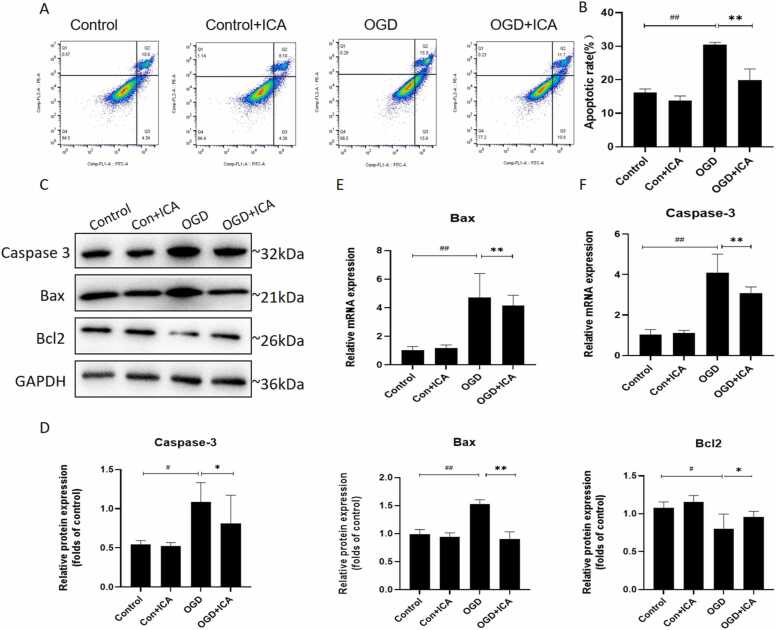

ICA reduced OGD-induced cell apoptosis in N2a cells

To determine the percentage of apoptotic cells after OGD, we used the Annexin V-FITC and PI double-staining kit. ODG-induced N2a cell apoptosis was significantly increased compared to that in the control group (P < 0.01, Fig. 2A–B). However, after treatment with ICA, the apoptosis rate of N2a cells significantly decreased (P < 0.01, Fig. 2A–B). We investigated the inhibitory effect of ICA on OGD-induced neuronal apoptosis. Western blotting and RT-qPCR were used to detect apoptosis-related markers, and we found that the expression levels of Bax and caspase-3 increased, while the expression of Bcl-2 decreased after OGD treatment (P < 0.01, Fig. 2C-F), which was reversed after ICA treatment (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, Fig. 2C–F). These results confirmed that ICA protected N2a cells from OGD-induced apoptosis.

Fig. 2.

ICA reduces OGD-induced cell apoptosis in N2a cells. (A-B) Neurons were exposed to OGD with or without ICA; apoptosis was then analysed using flow cytometry with the Annexin V/PI double staining kit. (C–F) Western blot and RT-qPCR were used to detect the expression levels of apoptotic markers (caspase-3, Bcl-2, and Bax) at protein and mRNA levels. Protein expression was quantified by densitometry. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n ≥ 3). ## P < 0.01, # P < 0.05, vs. control group; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, vs. OGD group.

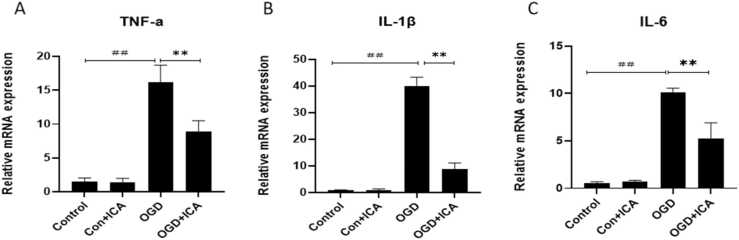

ICA reduced OGD-induced cell inflammation in N2a cells

To determine whether ICA can improve neuronal inflammation after OGD, the mRNA expression of TNF-a, IL-6, and IL-1β were detected after 3 h in case of OGD and after 24 h when considering reperfusion. We found that the expression of TNF-a, IL-6, and IL-1β were obviously increased after OGD (P < 0.05, Fig. 3A–C). However, after ICA treatment, these results were reversed (P < 0.05, Fig. 3A–C). These results indicate that ICA plays an important anti-inflammatory role in N2a cells after OGD.

Fig. 3.

ICA reduces OGD-induced cell inflammation in N2a cells. The mRNA expressions of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in N2a cells after OGD/R were detected using RT-QPCR; β-actin served as an internal control. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n ≥ 3). ## P < 0.01, # P < 0.05, vs. control group; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, vs. OGD group.

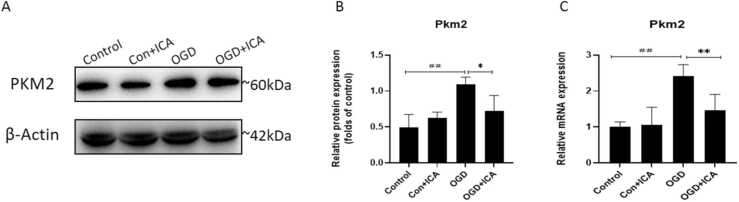

ICA down-regulated the expression of PKM2 after OGD in N2a cells

Western blotting and RT-qPCR were used to detect the effects of ICA on PKM2 expression in the neurons of each group. Compared to the control group, the expression levels of the PKM2 protein and mRNA in the OGD group were significantly increased (P < 0.01). After ICA intervention, the expression levels of the PKM2 protein and mRNA decreased compared to those in the OGD group (P < 0.01, Fig. 4A–C). These results indicate that ICA could regulate the expression of PKM2 in OGD neurons.

Fig. 4.

ICA up-regulates the expression of PKM2 after OGD in N2a cells. (A-B) Western blot was used to detect the levels of protein expression of PKM2, and the protein expression was quantified by densitometry. (C) The expression of the mRNA levels of PKM2. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n ≥ 3). ## P < 0.01, # P < 0.05, vs. control group; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, vs. OGD group.

Effects of the PKM2-specific agonist TEPP-46 on apoptosis-related protein expression in ICA-treated OGD neurons

TEPP-46 is a specific activator of PKM2 (Palsson-McDermott et al., 2015). The levels of apoptosis-related proteins caspase-3, Bax, and Bcl-2 in each group were detected by western blotting. After TEPP-46 treatment, the expressions of Bax and caspase-3 in the OGD+ICA group were significantly increased, and the differences were statistically significant compared to the OGD + ICA group (all P < 0.05). The level of Bcl-2 was downregulated, but the difference was not statistically significant compared to that in the OGD+ICA group (P > 0.05, Fig. 5A–B). These results suggest that ICA inhibits the apoptosis of OGD neurons by regulating the expression of PKM2 and reducing the levels of pro-apoptotic proteins.

Fig. 5.

Effects of PKM2-specific agonist TEPP-46 on apoptosis-related protein expression in ICA-treated OGD neurons. (A) Western blot was used to measure the protein levels of PKM2 and apoptosis markers (caspase-3, Bcl-2, and Bax) in the different groups after TEPP-46 treatment. (B) Quantitative analysis of PKM2 and apoptosis markers by densitometry. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n ≥ 3). ## P < 0.01, vs. control group; * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, vs. OGD group; *** P < 0.05, vs. OGD + ICA group.

Discussion

Ischaemic stroke is the most common type of stroke (Minnerup et al., 2012) and neuronal damage is a huge social burden (Kong et al., 2022). However, this treatment is limited at present (Zhu et al., 2021a). Over a long period of clinical practice, many researchers have found that traditional Chinese medicine and natural drugs have a protective effect against ischaemic stroke, and their side effects are very small (Zhu et al., 2021b, Wang et al., 2021). ICA is an active ingredient extracted from epimedium. Studies have found that ICA could inhibit I/R-induced NF-κB activation and pro-inflammatory/pro-apoptosis factors production, suggesting that ICA plays a positive role in anti-inflammation and anti-apoptosis (Dai et al., 2021). In this study, the N2a cell model of OGD was used to observe the effect of ICA on ischaemic stroke injuries. ICA could inhibit OGD-induced N2a cell inflammation and apoptosis by regulating PKM2, providing a reference for molecular targeting studies to relieve ischaemic stroke.

The morphological features of apoptosis are varied (Kerr et al., 1972). As known, there are many genes and signalling pathways related to apoptosis that are involved in this process (Uzdensky, 2019, Tian et al., 2018). Bcl-2 is an anti-apoptotic protein (Warren et al., 2019). Bax is a pro-apoptotic protein (Pistritto et al., 2016, Shehadah et al., 2013, Wang et al., 2022). Caspase-3 is present in the cell as an inactive proenzyme, which is cleaved and activated by intrinsic (mitochondrial) and extrinsic (death receptor) pathways (D'Amelio et al., 2010), and caspase-3 is normally regarded as the last step of cell death (Gibbs et al., 2016). In the present study, apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2, Bax, and caspase-3) were identified as important targets regulated by ICA treatment after ischaemic stroke. Western blot results indicated that ICA treatment effectively regulated the expression of apoptotic proteins in the OGD-induced cell model. These data suggest that the beneficial action of ICA against post-stroke brain damage was partly mediated via modulation of the apoptotic protein-mediated mechanism of apoptosis.

Inflammation is also an important mechanism of ischaemic stroke (Zhu et al., 2022). When ischaemic stroke occurs, microglia and neutrophils are successively activated, exacerbating oxidative stress and blood-brain barrier damage, and a series of biologically active substances that mediate neurotoxicity and cause secondary brain damage are released (Ahn et al., 2022, Khoshnam et al., 2017). Primary neuronal cell death in the ischaemic core generally mediates secondary immune or inflammatory response (Fu et al., 2015). Therefore, inhibiting the activation of inflammation is essential for neuroprotection and for reducing cell death (Shichita et al., 2017). In our study, the mRNA expression of inflammatory genes in OGD-induced neurons was up-regulated, and ICA treatment significantly downregulated the expression of inflammatory genes in OGD neurons (P < 0.05). These results suggested that ICA reduced apoptosis after ischaemic stroke by downregulating the expression of inflammatory genes.

Pyruvate kinase (PK) catalyses the last step of glycolysis (David et al., 2010). Studies have found that PKM2 plays an important role in tumour cell proliferation; however, recent research has indicated that PKM2 also regulates apoptosis (Liang et al., 2017). Many studies have reported that PKM2 phosphorylates Bcl-2 and directly inhibits apoptosis (Liang et al., 2017). However, conflicting reports have revealed a role for PKM2 in apoptosis (Doddapattar et al., 2022, Dhanesha et al., 2022). We hypothesised that these contradictory conclusions might arise from a lack of differentiation between the effects of PKM2 originating from various tissue sources, as resident immune cells in the brain and immune cells of the myeloid origin express PKM2. Therefore, it is crucial to determine the function of PKM2 in different cells and tissues during the progression of ischaemic stroke.

In this study, compared with the control group, the expression of PKM2 in the OGD group was significantly increased (P < 0.01), and ICA significantly inhibited the expression of PKM2 in OGD neurons (P < 0.05). The PKM2 specific activator TEPP-46 was used to enhance the expression of PKM2 in vitro, and the results showed that TEPP-46 significantly increased the protein expressions of caspase 3 and Bax in ICA-treated OGD neurons (P < 0.05) but had no significant effect on the Bcl-2 protein level (P > 0.05). These results suggest that ICA inhibits the apoptosis of OGD neurons by regulating the expression of PKM2 and reducing the levels of pro-apoptotic proteins.

Conclusion

ICA is effective in preventing neuronal death after ischaemic stroke, protecting cells from apoptosis by regulating the expression of PKM2 and reducing the levels of pro-apoptotic proteins.

Ethical Statement

“I certify that this manuscript is original and has not been published and will not be submitted elsewhere for publication while being considered by Neuroscience. And the study is not split up into several parts to increase the quantity of submissions and submitted to various journals or to one journal over time. No data have been fabricated or manipulated (including images) to support your conclusions. No data, text, or theories by others are presented as if they were our own. The submission has been received explicitly from all co-authors. And authors whose names appear on the submission have contributed sufficiently to the scientific work and therefore share collective responsibility and accountability for the results.”

Funding

This study was funded by the Health Institute of Nanjing (Grant nos. ZKX19013 and ZKX21025).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lina Kang: Writing – review & editing. Jie Ni: Supervision. Qianzhi Shi: Data curation, Formal analysis. Lu Zhang: Investigation, Writing – original draft. Dujuan Sha: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Renfang Zou: Methodology. Jiayi Si: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Shan Chen: Methodology, Writing – original draft.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the laboratory staff for helping with this study.

Author contributions

Dj Sha and J Ni developed the study concept and experimental design. S Chen drafted the manuscript and performed the experiments. QZ Shi and RF Zou corrected the draft, and L Zhang performed data acquisition and analysis. Ln Kang and Jy Si supervised the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

References

- Ahn W., Chi G., Kim S., Son Y., Zhang M. Substance P reduces infarct size and mortality after ischemic stroke, possibly through the M2 polarization of microglia/macrophages and neuroprotection in the ischemic rat brain. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10571-022-01284-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar S., Stanwell P., Cordato D., Attia J., Levi C. Reperfusion therapy in acute ischemic stroke: dawn of a new era? BMC Neurol. 2018;18(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12883-017-1007-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell B.C.V., De Silva D.A., Macleod M.R., Coutts S.B., Schwamm L.H., Davis S.M., Donnan G.A. Ischaemic stroke. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2019;5(1):70. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M., Chen B., Wang X., Gao C., Yu H. Icariin enhance mild hypothermia-induced neuroprotection via inhibiting the activation of NF-kappaB in experimental ischemic stroke. Metab. Brain Dis. 2021;36(7):1779–1790. doi: 10.1007/s11011-021-00731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amelio M., Cavallucci V., Cecconi F. Neuronal caspase-3 signaling: not only cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17(7):1104–1114. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David C.J., Chen M., Assanah M., Canoll P., Manley J.L. HnRNP proteins controlled by c-Myc deregulate pyruvate kinase mRNA splicing in cancer. Nature. 2010;463(7279):364–368. doi: 10.1038/nature08697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida F.M., Marques S.A., Dos Santos A.C.R., Prins C.A., Dos Santos Cardoso F.S., Dos Santos Heringer L., Mendonca H.R., Martinez A.M.B. Molecular approaches for spinal cord injury treatment. Neural Regen. Res. 2023;18(1):23–30. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.344830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanesha N., Patel R.B., Doddapattar P., Ghatge M., Flora G.D., Jain M., Thedens D., Olalde H., Kumskova M., Leira E.C., Chauhan A.K. PKM2 promotes neutrophil activation and cerebral thromboinflammation: therapeutic implications for ischemic stroke. Blood. 2022;139(8):1234–1245. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021012322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doddapattar P., Dev R., Ghatge M., Patel R.B., Jain M., Dhanesha N., Lentz S.R., Chauhan A.K. Myeloid cell PKM2 deletion enhances efferocytosis and reduces atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2022;130(9):1289–1305. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.320704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Liu Q., Anrather J., Shi F.D. Immune interventions in stroke. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015;11(9):524–535. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs W.S., Weber R.A., Schnellmann R.G., Adkins D.L. Disrupted mitochondrial genes and inflammation following stroke. Life Sci. 2016;166:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J.F., Wyllie A.H., Currie A.R. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br. J. Cancer. 1972;26(4):239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshnam S.E., Winlow W., Farzaneh M., Farbood Y., Moghaddam H.F. Pathogenic mechanisms following ischemic stroke. Neurol. Sci. 2017;38(7):1167–1186. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-2938-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L., Li W., Chang E., Wang W., Shen N., Xu X., Wang X., Zhang Y., Sun W., Hu W., Xu P., Liu X. mtDNA-STING axis mediates microglial polarization via IRF3/NF-kappaB signaling after ischemic stroke. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.860977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X., Yao X., Ren J., Gao J., Cui Y., Sun J., Xu X., Hu W., Wang H., Li H., Glebov O.O., Che F., Wan Q. tDCS regulates ASBT-3-OxoLCA-PLOD2-PTEN signaling pathway to confer neuroprotection following rat cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023;60(11):6715–6730. doi: 10.1007/s12035-023-03504-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J., Cao R., Wang X., Zhang Y., Wang P., Gao H., Li C., Yang F., Zeng R., Wei P., Li D., Li W., Yang W. Mitochondrial PKM2 regulates oxidative stress-induced apoptosis by stabilizing Bcl2. Cell Res. 2017;27(3):329–351. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H., He X., Yang Y., Li M., Hao D., Jia Z. The genus Epimedium: an ethnopharmacological and phytochemical review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;134(3):519–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnerup J., Sutherland B.A., Buchan A.M., Kleinschnitz C. Neuroprotection for stroke: current status and future perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012;13(9):11753–11772. doi: 10.3390/ijms130911753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Z.T., Zheng J., Liao Y.L. Icariin inhibits the expression of IL-1beta, IL-6 and TNF-alpha induced by OGD/R through the IRE1/XBP1s pathway in microglia. Pharm. Biol. 2021;59(1):1473–1479. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2021.1991959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palsson-McDermott E.M., Curtis A.M., Goel G., Lauterbach M.A., Sheedy F.J., Gleeson L.E., van den Bosch M.W., Quinn S.R., Domingo-Fernandez R., Johnston D.G., Jiang J.K., Israelsen W.J., Keane J., Thomas C., Clish C., Vander Heiden M., Xavier R.J., O'Neill L.A. Pyruvate kinase M2 regulates Hif-1alpha activity and IL-1beta induction and is a critical determinant of the warburg effect in LPS-activated macrophages. Cell Metab. 2015;21(1):65–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y., Kong L.D., Li Y.C., Xia X., Kung H.F., Jiang F.X. Icariin from Epimedium brevicornum attenuates chronic mild stress-induced behavioral and neuroendocrinological alterations in male Wistar rats. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 2007;87(1):130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng T., Li S., Liu L., Yang C., Farhan M., Chen L., Su Q., Zheng W. Artemisinin attenuated ischemic stroke induced cell apoptosis through activation of ERK1/2/CREB/BCL-2 signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022;18(11):4578–4594. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.69892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistritto G., Trisciuoglio D., Ceci C., Garufi A., D'Orazi G. Apoptosis as anticancer mechanism: function and dysfunction of its modulators and targeted therapeutic strategies. Aging. 2016;8(4):603–619. doi: 10.18632/aging.100934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehadah A., Chen J., Kramer B., Zacharek A., Cui Y., Roberts C., Lu M., Chopp M. Efficacy of single and multiple injections of human umbilical tissue-derived cells following experimental stroke in rats. PLoS One. 2013;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shichita T., Ito M., Morita R., Komai K., Noguchi Y., Ooboshi H., Koshida R., Takahashi S., Kodama T., Yoshimura A. MAFB prevents excess inflammation after ischemic stroke by accelerating clearance of damage signals through MSR1. Nat. Med. 2017;23(6):723–732. doi: 10.1038/nm.4312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y.S., Zhong D., Liu Q.Q., Zhao X.L., Sun H.X., Jin J., Wang H.N., Li G.Z. Upregulation of miR-216a exerts neuroprotective effects against ischemic injury through negatively regulating JAK2/STAT3-involved apoptosis and inflammatory pathways. J. Neurosurg. 2018;130(3):977–988. doi: 10.3171/2017.5.JNS163165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzdensky A.B. Apoptosis regulation in the penumbra after ischemic stroke: expression of pro- and antiapoptotic proteins. Apoptosis. 2019;24(9-10):687–702. doi: 10.1007/s10495-019-01556-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Hu J., Chen X., Lei X., Feng H., Wan F., Tan L. Traditional Chinese medicine monomers: novel strategy for endogenous neural stem cells activation after stroke. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021;15 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.628115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wu H., Han Z., Sheng H., Wu Y., Wang Y., Guo X., Zhu Y., Li X., Wang Y. Guhong injection promotes post-stroke functional recovery via attenuating cortical inflammation and apoptosis in subacute stage of ischemic stroke. Phytomedicine. 2022;99 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren C.F.A., Wong-Brown M.W., Bowden N.A. BCL-2 family isoforms in apoptosis and cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(3):177. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1407-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap S.P., Shen P., Li J., Lee L.S., Yong E.L. Molecular and pharmacodynamic properties of estrogenic extracts from the traditional Chinese medicinal herb, Epimedium. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113(2):218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Cao X., Bao X., Zhang Y., Xu Y., Sha D. Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript protects synaptic structures in neurons after ischemic cerebral injury. Neuropeptides. 2020;81 doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2020.102023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Jian Z., Zhong Y., Ye Y., Zhang Y., Hu X., Pu B., Gu L., Xiong X. Janus Kinase inhibition ameliorates ischemic stroke injury and neuroinflammation through reducing nlrp3 inflammasome activation via JAK2/STAT3 pathway inhibition. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.714943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T., Wang L., Feng Y., Sun G., Sun X. Classical active ingredients and extracts of Chinese herbal medicines: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and molecular mechanisms for ischemic stroke. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/8868941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T., Wang L., Wang L.P., Wan Q. Therapeutic targets of neuroprotection and neurorestoration in ischemic stroke: applications for natural compounds from medicinal herbs. Biomed. Pharm. 2022;148 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.112719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]