Abstract

The mental health crisis among Native Hawaiian young adults is exacerbated by colonization-related risk factors, yet cultural identity stands as a key protective element. This study explored the link between cultural identity and stress, employing cultural reclamation theory, and surveyed 37 Native Hawaiians aged 18–24 through the Native Hawaiian Young Adult Well-being Survey. Engagement with culture, the significance of Hawaiian identity, and stress were assessed, revealing significant correlations between cultural and demographic factors and stress levels. Participants displayed high cultural engagement and valued their Hawaiian identity, with gender and education levels playing a notable role in stress. These findings highlight the importance of including Native Hawaiian perspectives in mental health research and may guide the development of targeted interventions.

Keywords: Native Hawaiian, young adults, cultural identity, cultural reclamation, perceived stress

Introduction

Mental health is a serious, under-addressed issue, especially within the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (NHPI) community.1 The NHPI community experience higher rates of depression, suicide, and anxiety compared to other ethnic groups in Hawai‘i.2 Research also links mental illness to increased likelihood of developing serious health conditions. Compared to other ethnic groups, Native Hawaiians experience some of the highest rates of diabetes, heart disease, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and chronic stress.1,3 The severity of this mental health crisis is exacerbated with the intersectionality of other demographics, such as age and race. Young adults are at a greater risk of developing mental health concerns, and the millennial cohort is facing a faster decline in their mental health compared to previous generations.4,5 Furthermore, Indigenous young adults are at greater risk of developing mental health concerns, due to the inequity that their communities face and the barriers to accessing mental health treatment such as fear, shame, intergenerational trauma, and distrust of service confidentiality.6,7 In this article, “Indigenous” is used in a broad context to refer to “the original inhabitants of the land.”8

Despite the mental health crisis, Native Hawaiians have some of the lowest rates of mental health service.9 This prompts the need to consider the historical context of inequity in the Native Hawaiian community.10 Native Hawaiians continue to be impacted in similar ways to other colonized groups, including exposure to foreign disease, and loss of land, language, culture, and autonomy over their lands.11 However, Native Hawaiians continue to keep their culture alive through collective knowledge. Equating health statistics to community deficits creates the false narrative that Indigenous peoples fail to succeed in Euro-colonial societies.12–14 Furthermore, there is limited research that focuses on mental health from Native Hawaiian perspectives due to the aggregation of Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders and Asian Americans.15

Understanding Native Hawaiian identity is critical in promoting Native Hawaiian well-being because research shows that cultural identity is a protective factor against adversity for Indigenous peoples.5,14 Additionally, studies show that Native Hawaiians often prefer cultural ways of healing.16–18 From a cultural lens, well-being is understood from a holistic perspective, in which the biological, psychological, emotional, social, and spiritual dimensions are all considered.18,19 An individual is not seen as an isolated entity – contrary to the Euro-colonial value of individualism – but rather as an interrelated part in a greater system of relationships with the ‘āina (land), ‘ohana (family), akua (god(s)), and the lāhui (Native Hawaiian nation or community).20 Moreover, Native Hawaiian well-being is informed by values of collectivism, and the individual and overall community are considered the healthiest when all the dimensions of the individual and cultural relationships are in lōkahi (harmony).20 Drawing upon culture leads to overall empowerment of the community through the recognition of community strengths.21–23 In one study, a Native Hawaiian respondent described a “healthy Native Hawaiian” as an image of “The Healthy Ancestor.”24 This image is significant because it shows that Native Hawaiians understand their “natural” state as healthy.24 Therefore, reclaiming this sense of self for Native Hawaiians is imperative to revitalizing health in contemporary society.

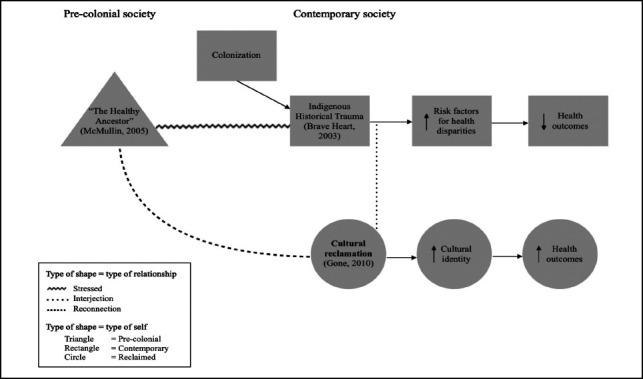

According to cultural reclamation theory, healing for Indigenous peoples occurs as they embrace their culture.25 During this process, the impacts of colonization are understood as continuous. Historical trauma is the “complex, collective, cumulative, and intergenerational psychosocial impacts that resulted from the depredations of past colonial subjugation.”26 Cultural reclamation interrupts the snowball effect of historical trauma, which would otherwise lead to higher vulnerability to health-related risk factors for Indigenous peoples.27 As Indigenous peoples embrace their culture, they also create pathways to reconnect to their ancestral past in order to make sense of themselves. This leads to an increased sense of cultural identity and overall well-being (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Author’s Interpretation of Joseph Gone’s Cultural Reclamation Theory25

This study argues that healing for Native Hawaiian young adults occurs through: (1) resistance towards colonial forces; (2) finding one’s purpose as a Native Hawaiian; and (3) meaningful engagement with Native Hawaiian culture practices. The authors acknowledge that the term “Native Hawaiian” has multiple nuances and may not fully capture or accurately represent identity for individuals within this community. In constructing measurements for cultural reclamation theory, this study expands on research about Native Hawaiian conceptualizations of health and well-being.

Methods

Data Collection

Data from the Native Hawaiian Young Adult Well-being Survey was analyzed to examine the relationship between cultural identity and stress among Native Hawaiian young adults. This study hypothesized that respondents with connection to their identity through engagement with Native Hawaiian culture will have lower perceived stress. The survey instrument and research design used for this study were approved for ethical review in the beginning of March 2022 (Hawai‘i Pacific University IRB: #56042021019). The survey instrument was available online through SurveyMonkey,™ (Survey Monkey, Inc., San Mateo, CA) and responses were collected over a 1-month period from March to April 2022.

Convenience and snowball sampling were used in this study, which aimed to recruit Hawai‘i residents, aged 18–24 years, who self-identified as Native Hawaiian. No sample size calculations were done; however, a target sample size of 100 participants was decided based on the period for data collection. Prior to the survey, respondents were asked to read an online consent and debriefing form that described the study procedures, confidentiality measures, and future use of the survey data. Self-reported and administered surveys were used as non-intrusive approaches that see respondents as the experts on their own cultural identity and mental health.28 Additionally, respondents were able to complete this survey at their own pace and in environments of their choice. All participation was voluntary and could be stopped at any point. There was no way to link any personal identifiers of respondents to their responses. The 20-question survey took approximately 10 minutes to complete. This study was funded by a $4000 grant that was used to purchase $10 Starbucks™ e-gift cards for compensating respondents and for Stata™ software Version 17 (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, TX) for statistical analysis (NIH: U01GM128435, PI: Vakalahi).

This study was grounded in Indigenous data sovereignty through involvement of Indigenous voices and transparency throughout the research process.29 Additionally, an Instagram™ account (@nhyawellbeingsurvey) was created to disseminate information on the study’s purpose, research team, study procedures and confidentiality measures, and potential plans for the collected data. Community stakeholders that regularly engage with this study’s target population were also contacted and asked if they were willing to share the survey.

Measures & Data Analysis

Native Hawaiian identity and cultural engagement questions were used as measurements for the independent variable, cultural identity (Table 1). These questions were derived from important themes within Native Hawaiian identity well-being literature18,23 and identity questions from the 2019 Native Hawaiian Survey.30 Perceived stress questions were used as measurements for the dependent variable, stress, through the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) instrument, which is the most widely used psychological instrument for measuring the perception of stress31 (Table 1). For positive PSS variables (confidence coping; ability to control irritations; and felt on top of things), responses were reverse coded prior to being summed for sum stress.

Table 1.

Cultural Identity and Perceived Stress Scale Variables from the Native Hawaiian Young Adult Well-being Survey

| Variable Name | Variable Question | Variable Coding |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural Engagement | On a day-to-day basis, how often do you engage with Hawaiian culture (values, practices, traditions)? | 4 - Almost always, 5–7 days a week 3 - Often, 1–4 days a week 2 - Sometimes, once a month 1 - Rarely, few times a year 0 - Never |

| Community Engagement | On a day-to-day basis, how often do you engage with others in the Hawaiian community? | |

| Cultural Engagement Importance | Being able to engage with Hawaiian culture (values, practices, and activities) is important to me. | 5 - Strongly Agree. 4 - Agree 3 - Neither Agree or Disagree 2- Disagree 1- Strongly Disagree |

| Community Engagement Importance | Being able to engage with others in the Hawaiian community is important to me | |

| Learn Hawaiian History | I enjoy learning about Hawaiian history | |

| Healthy Cultural Engagement | I feel healthier when I engage with Hawaiian culture | |

| Pride Hawaiian Identity | I feel proud to be Hawaiian | |

| Community Belonging | I feel like I belong within the Hawaiian community | |

| Community Affect | I feel affected by the successes and/or stressors of others in the Hawaiian community | |

| In the last month… | ||

| Upset from Unexpected Events | How often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly? | 4 - Very often 3 - Fairly often 2 - Sometimes 1 - Almost never 0 - Never |

| Difficulty Controlling Important Things | How often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life? | |

| Nervous and Stressed Feelings | How often have you felt nervous and stressed? | |

| Confidence Coping | How often have you felt confident in your ability to handle your personal problems? | |

| Things Going Well | How often have you felt that things were going your way? | |

| Difficulty Coping with Tasks | How often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do? | |

| Able to Control Irritations | How often have you been able to control irritations in your life? | |

| Felt on Top of Things | How often have you felt that you were on top of things? | |

| Angered by Outside Things | How often have you been angered because of things that happened that were outside of your control? | |

| Unable to Overcome Difficulties | How often have you felt difficulties piling up so high that you could not overcome them? | |

| Sum Stress* | Total stress (sum of scores* from each PSS question) | |

For positive PSS variables (Confidence Coping, Ability to Control Irritations, and Felt on Top of Things), responses were reverse coded prior to being summed for Sum Stress.

Data from the Native Hawaiian identity and cultural engagement variables were run through multi-linear regressions for each PSS variable. Demographic controls were added to regressions considering social determinants of health.32,33 Demographics were coded into the following dummy variables: female, higher education, student, and employed. No question asked respondents about their specific age within the 18–24 age range, so age was not included as a control.

Results

A total of 43 respondents fully completed the survey. The majority of these respondents identified as female (74%), completed high school (83%), were full-time students (63%), and were employed part-time (51%) during the time of the survey (Table 2). “Other” responses; “No” or missing responses for any of the inclusion questions; duplicate or irrelevant responses; and responses that were not fully completed (3 or more skipped questions) were excluded from analyses, which decreased the number of observations within our regression (N=37). It is also possible that not every respondent answered every question for the variables used.

Table 2.

Demographics of Native Hawaiian Young Adult Well-being Survey Participants

| Characteristic | N = 43a No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender Identity | |

| Male | 8 (19) |

| Female | 32 (74) |

| Non-binary | 2 (5) |

| Other | 1 (2) |

| Highest Education | |

| Some high school | 2 (5) |

| High school or equivalent | 16 (37) |

| Some college | 12 (28) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 8 (19) |

| Other | 5 (12) |

| Current Education | |

| Full-time student | 27 (63) |

| Part-time student | 4 (9) |

| Trade school | 1 (2) |

| Not enrolled in school | 10 (23) |

| Other | 1 (2) |

| Employment | |

| Full-time | 11 (26) |

| Part-time | 22 (51) |

| Self-employed | 1 (2) |

| Actively looking | 4 (9) |

| Unemployed | 2 (5) |

| Other | 3 (7) |

Observation values for sample demographics (N=43) differ from observation values (N=37) in the regression models due to the construction of the dummy variables used in the regression models. It is also possible that not every respondent answered every question for the variables used.

Levels of Cultural Engagement & Importance of Native Hawaiian Identities

When asked about their engagement with Native Hawaiian culture through cultural values, practices, and activities, the average was close to “Often (1–4 days/wk)” (x = 2.67; SD = 0.92; Table 3). When respondents were asked about their engagement with others in the Native Hawaiian community, the average response was closer to “Often” (x = 2.93; SD = 0.96; Table 3).

Table 3.

Cultural Engagement & Native Hawaiian Identity and PSS Descriptive Statistics from the Native Hawaiian Young Adult Well-being Survey

| Variable | Mean (x) |

Std. Dev. (SD) |

Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural engagement | 2.67 | 0.92 | 1 | 4 |

| Community engagement | 2.93 | 0.96 | 1 | 4 |

| Cultural engagement importance | 3.69 | 0.51 | 2 | 4 |

| Community engagement importance | 3.65 | 0.53 | 2 | 4 |

| Learn Hawaiian history | 3.77 | 0.48 | 2 | 4 |

| Healthy cultural engagement | 3.49 | 0.70 | 2 | 4 |

| Pride Hawaiian identity | 3.93 | 0.26 | 3 | 4 |

| Belonging community | 3.28 | 0.85 | 1 | 4 |

| Community affect | 3.21 | 0.77 | 1 | 4 |

| Upset from Unexpected Events | 2.51 | 0.86 | 1 | 4 |

| Difficulty Controlling Important Things | 2.47 | 0.92 | 1 | 4 |

| Nervous and Stressed Feelings | 3.16 | 0.87 | 1 | 4 |

| Confidence Coping | 2.53 | 0.80 | 0 | 4 |

| Things Going Well | 2.09 | 0.72 | 0 | 4 |

| Difficulty Coping with Tasks | 2.23 | 1.02 | 0 | 4 |

| Able to Control Irritations | 2.23 | 0.78 | 1 | 4 |

| Felt on Top of Things | 2.32 | 0.97 | 0 | 3 |

| Angered by Outside Things | 2.33 | 0.98 | 0 | 4 |

| Unable to Overcome Difficulties | 2.37 | 0.98 | 1 | 4 |

| Sum Stress | 22.25 | 2.83 | 17 | 30 |

Moderate Perceived Stress & Confidence in Coping

According to the PSS scoring criteria, scores ranging from 0–13 indicate low perceived stress, 14–26 indicate moderate perceived stress, and 27–40 indicate high perceived stress. For overall perceived stress scores, the average score is in the middle of the moderate perceived stress range (x = 22.26; SD = 2.83; Table 3).

Respondents indicated the highest average for the nervous and stressed feelings variable (x = 3.16; SD = 0.87; Table 3) and the lowest average for the things going well variable (x = 2.09; SD = 0.72; Table 3). However, the confidence coping variable yielded the second highest average after the nervous and stressed feelings variable (x = 2.53; SD = 0.80; Table 3).

For the cultural identity and engagement variables, respondents indicated high levels of cultural engagement and importance of Native Hawaiian identity. The pride in Native Hawaiian identity variable yielded the highest average level of agreement (x = 3.93; SD = 0.26; Table 3). No respondent answered “Neither Agree or Disagree,” “Disagree,” or “Strongly Disagree.” Levels of agreement were lowest for the community affect variable. When asked about feeling affected by the stressors and/or successes of others in the Native Hawaiian community, the average response was near “Agree” (x = 3.21; SD = 0.77; Table 3).

For the perceived stress variables, respondents indicated moderate levels of overall perceived stress. The community affect cultural identity variable had a negative statistically significant impact on overall perceived stress. For the confidence coping stress variable, there were positive statistically significant relationships with the community engagement importance variable and education dummy variable, and a negative statistically significant relationship with gender (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multi-linear Regression Results Comparing Cultural Identity Variables to Significant Perceived Stress Variables, Native Hawaiian Young Adult Well-being Survey

| Sum Stress | Confidence Coping | |

|---|---|---|

|

β Coefficient (Standard Error)

P-Value |

β Coefficient (Standard Error)

P-Value |

|

| Cultural Engagement | −0.23 (0.64) P=.73 |

−0.14 (0.17) P=.43 |

| Community Engagement | 0.37 (0.54) P = .50 |

−0.10 (0.15) P = .50 |

| Cultural Engagement Importance | −0.65 (1.31) P = .62 |

−0.31 (0.35) P = .39 |

| Community Engagement Importance | 0.48 (1.10) P = .67 |

0.66 (0.30) P = .038 |

| Learn Hawaiian History | 0.44 (0.86) P = .62 |

−0.40 (0.23) P = .095 |

| Healthy Cultural Engagement | −1.16 (0.78) P = .150 |

0.22 (0.21) P = .32 |

| Pride Hawaiian Identity | −1.89 (1.79) P = .301 |

−0.85 (0.48) P = .092 |

| Belonging Community | −0.82 (0.52) P= .130 |

−0.14 (0.14) P= .33 |

| Community Affect | −1.41 (0.63) P = .037 |

0.19 (0.17) P = .29 |

| Gender | 0.50 (1.14) P = .67 |

−0.77 (0.31) P = .021 |

| Education | 0.29 (0.88) P= .74 |

0.53 (0.24) P = .035 |

| Student | −0.02 (1.10) P = .99 |

0.33 (0.30) P = .28 |

| Employment | 0.5 (1.92) P = .80 |

−0.64 (0.52) P = .23 |

| Constant | 43.61 (9.15) | 7.33 (2.47) |

| N | 37 | 37 |

| F(13, 23) | 2.37 | 1.77 |

| Prob > F | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| R2 | 0.57 | 0.5 |

| Adj R2 | 0.33 | 0.22 |

| Root MSE | 2.34 | 0.63 |

Only the Sum Stress and Confidence Coping models are included in this table from the PSS variables because no statistically significant variables were yielded in the other models.

Demographic Variables: Community Affect, Community Engagement Importance, Gender, & Education

Although multi-linear regressions were run for each PSS variable with the Native Hawaiian identity and cultural engagement variable, only the sum stress and confidence coping models are included in this table because no statistically significant variables were yielded in the other models (Table 4). First, a negative relationship (β = −1.41, SE = 0.63, P=.037) was found between the sum stress variable and the community affect variable (Table 4). Second, positive relationships were found between the confidence coping and community engagement importance variable (β = 0.66, SE = 0.30, P=.038), and the education variable (β = 0.53, SE = 0.24, P=0.035; Table 4). Therefore, as the importance of engaging with others in the Native Hawaiian community and education levels increase, confidence in ability to cope with stress is also more likely to increase. Additionally, a negative relationship was found between the confidence coping and gender variables (β=−0.77, SE = 0.31, P=.021; Table 4). Respondents who identified as male were more likely to have higher confidence in ability to cope with stress compared to respondents who identified as female. Additionally, because the majority of this sample identified as female, when looking at gender differences in education level, 63% percent of the total 32 female respondents received some form of higher education, while only 37% of the total 3 male respondents received some form of higher education.

Discussion

This study of Native Hawaiian young adults found that (1) respondents indicated high levels of engagement with Native Hawaiian culture and importance of Native Hawaiian identity; and (2) respondents displayed levels of overall perceived stress that were similar to levels of confidence in their abilities to cope with stress.

While respondents indicated experiencing feelings of nervousness and defeat at moderately high rates, they also indicated feeling similar levels of confidence in coping with these feelings. Additionally, the majority of respondents yielded scores in the moderate perceived stress range, although their expected perceived stress levels may be higher given the impacts of colonization, including the disproportionate rates of mental and physical health conditions among Native Hawaiians.1,2 Confidence in ability to cope with stress may be an act of resistance in itself, especially since research often emphasizes the deficits within the Native Hawaiian community.9,10 Furthermore, although Native Hawaiians continue to experience loss of land, language, culture, and autonomy over their lands due to colonization,11 when asked about key components to Native Hawaiian identity, such as the ability to engage with Native Hawaiian culture and others in the Native Hawaiian community, cultural learning, sense of pride and health, and sense of belonging to the Native Hawaiian community, levels of agreement were high across the board. Finding one’s purpose as an Indigenous person may be reflected through this, and further insight may be found in the high levels of pride associated with being Native Hawaiian among respondents. Lastly, meaningful engagement with Indigenous practices may be reflected in the high frequencies of engagement with Native Hawaiian values, practices, and traditions and others in the Native Hawaiian community indicated by respondents, as well as high levels of agreement that the ability to participate in these engagement processes is important.

Feeling impacted by the stressors and/or successes by others in the Native Hawaiian community had a significant negative relationship with overall perceived stress. Moreover, as feeling affected by the other stressors and/or successes by others in the Native Hawaiian community increases, overall perceived stress is more likely to decrease, and vice versa. Revisiting the cultural value of collectivism,20 this finding may indicate that respondents whose conceptualization of well-being aligns with a Native Hawaiian framework of well-being feel less stressed. More exploration into the different dimensions of Native Hawaiian well-being, particularly related to collectivism, may be valuable. Building upon collectivism, indicating high importance in ability to engage with others in the Native Hawaiian community had a significant positive relationship with confidence in ability to cope with stress. Moreover, respondents who indicated high importance in community engagement had higher levels of confidence in ability to cope with stress, whereas respondents who indicated low importance in community engagement had lower levels of confidence in ability to cope with stress. Further insight may be found in the role of social support in Native Hawaiian well-being found and specific ways Native Hawaiian young adults engage within the community.

Gender and education were 2 variables that were significant in relation to confidence in ability to cope with stress. Male respondents had higher confidence in their coping abilities, than female respondents. Additionally, education had a significant positive relationship with confidence in ability to cope with stress. Respondents who received some level of higher education had higher confidence in their coping abilities than those with high education or less. Although male respondents had higher confidence in their coping abilities, a higher percentage of female respondents received some form of higher education. Further exploration into these gendered differences and comparison of coping skills for each gender identity among Native Hawaiian young adults may be valuable for further analysis. Differences in accessibility to higher education may also be valuable to explore.

Revisiting the context of colonization may provide insight into the lack of significant relationships between the other cultural identity and stress variables. Native Hawaiians face barriers that prevent them from actively participating in cultural engagement processes, such as the need to continually advocate for the importance of accessing and protecting sacred lands in which these processes are rooted, and difficulty navigating institutional and social systems that are shaped by colonization.34 Lack of significance may also relate to the prevalence of deficits-based research on Native Hawaiians. Because the Native Hawaiian community is often overgeneralized by this type of research, learning through the lens of these narratives may create a negative sense of self among Native Hawaiians, which reinforces the need for more strengths-based research.12–14 Analysis of responses from the open-ended identity and well-being questions and focus groups may provide further insight into Native Hawaiian young adult conceptualizations of Native Hawaiian identity and well-being and their experiences with stress and mental health. Future studies should further examine factors that contribute to confidence in coping abilities among Native Hawaiian young adults, as well as the specific types of stress they experience, by incorporating quantitative data from this study using explanatory sequential analysis or qualitative data from focus group interviews.

Limitations

This study has several limitations, including a limited sample size; use of online platforms and monetary compensation as primary recruitment tools; use of “Native Hawaiian” as an identifier; and limited stress measurement. Due to this study’s convenience and snowball sampling methods, and low sample variability, the survey results cannot be generalized. Additionally, while there is typically a high use of social media among young adults,35 use of Instagram™ may have created selection bias. Use of SurveyMonkey™ may also have created a barrier for potential respondents who may not know how to use or access this survey platform. Next, utilizing “Native Hawaiian” as a self-identification label within this survey may not have been inclusive of all Native Hawaiians. Lastly, this study used perceived stress as the measurement for stress, but there may be other types of stress experienced by Native Hawaiian young adults that are not captured by the PSS.

Conclusion

The relationship between cultural identity and stress among Native Hawaiian young adults was analyzed using data from the Native Hawaiian Young Adult Well-being Survey, an original survey designed for this study. The following themes were found from the data, which may inform more effective mental health interventions for Native Hawaiian young adults: (1) respondents indicated high levels of engagement with Native Hawaiian culture and importance of Native Hawaiian identity; and (2) respondents displayed levels of overall perceived stress that were similar to levels of confidence in their abilities to cope with stress. Additionally, low statistical significance was found between the community affect variable in relation to the sum stress variable, as well as between the community engagement importance, gender, and education variable in relation to the confidence coping variable.

According to cultural reclamation theory, high levels of cultural engagement and importance of Native Hawaiian identity may reflect finding one’s personal purpose as an Indigenous person and meaningful engagement with Indigenous practices. Compounded with similar levels of confidence in ability to cope and overall perceived stress, the former may also be acts of resistance to colonization, given the ways Native Hawaiians may be expected to fail in contemporary society.13,20 Revisiting the context of colonization supports the need for more strengths-based research. Overall, stress management and strong cultural identity is present among this sample.

Catherine Jara

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) (Award numbers: U01 GM138435, U54GM138062). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health. We would also like to acknowledge the following for their support throughout this project: Lynette Cruz, Dr. Halaevalu Vakalahi, Dr. Scott Okamoto, Leilani De Lude, Emilia Kandagawa, Uncle Hiapo, Dennis Chun, and Jacqui Sovde.

Glossary

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- NHPI

Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander

- PSS

Perceived Stress Scale

Biography

Catherine Jara received her BSW from Hawai‘i Pacific University. She aims to increase visibility and representation of NHPI and Indigenous voices through strengths-based research. This study was originally developed for her senior capstone project, which she was awarded funding for as the 2022 Health Research Concept Competition (HRCC) winner from her university’s biomedical research center.

Throughout her undergraduate career and gap year, she has worked on multiple research projects that explored Native Hawaiian identity and well-being with her mentor, Dr. Ngoc Phan. She also presented at the 2022 and 2023 Western Political Science Association and 2023 Hawai‘i Sociological Association conferences.

Catherine Jara is currently a first-year Sociology PhD student at University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she continues to explore questions related to Native Hawaiian identity and belonging. She intends on returning home to continue giving back to her Native Hawaiian community.

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identify a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Guerrero APS, Chock S, Lee AK, Sugimoto-Matsuda J, Kelly AS. Mental health disparities, mechanisms, and intervention strategies. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(6):549–556. doi: 10.1097/yco.0000000000000551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrade NN, Hishinuma ES, McDermott JF, et al. The National Center on Indigenous Hawaiian Behavioral Health Study of prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Native Hawaiian adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(1):26–36. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000184933.71917.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Look MA, Maskarinec GG, de Silva M, Seto T, Mau ML, Kaholokula JK. Kumu hula perspectives on health. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2014;73(12):21–25. Suppl 3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kemp E, Chen H, Childers C. Mental health engagement: Addressing a crisis in young adults. Health Mark Q. 2021:1–21. doi: 10.1080/07359683.2021.2004339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Povey J, Raphiphatthana B, Torok M, et al. Involvement of Indigenous young people in the design and evaluation of digital mental health interventions: A scoping review protocol. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1) doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01685-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price M, Dalgleish J. Help-seeking among Indigenous Australian adolescents: exploring attitudes, behaviours and barriers. Youth Studies Australia. 2013;32(1):10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robards F, Kang M, Usherwood T, Sanci L. How marginalized young people access, engage with, and navigate health-care systems in the digital age: Systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(4):365–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schachter J, Funk A. Sovereignty, indigeneity, identities: Perspectives from Hawai‘i. Social Identities. 2012;18(4):399–416. doi: 10.1080/13504630.2012.673869. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ta VM, Juon H-soon, Gielen AC, Steinwachs D, Duggan A. Disparities in use of mental health and Substance Abuse Services by Asian and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander women. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2007;35(1):20–36. doi: 10.1007/s11414-007-9078-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Endo Inouye T, Estrella R. Toward health equity for Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islanders: The health through action model. The Foundation Review. 2014;6(1) doi: 10.9707/1944-5660.1188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The United Nations declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. Reflections on the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. 2008. [DOI]

- 12.McKivett A, Paul D, Hudson N. Healing conversations: Developing a practical framework for clinical communication between Aboriginal communities and Healthcare Practitioners. J Immigr Minor Health. 2018;21(3):596–605. doi: 10.1007/s10903-018-0793-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas D, Mitchell T, Arseneau C. Re-evaluating resilience: From individual vulnerabilities to the strength of cultures and collectivities among indigenous communities. Resilience. 2015;4(2):116–129. doi: 10.1080/21693293.2015.1094174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kana‘iaupuni SM. Ka‘akālai Kū Kanaka: A call for strengths-based approaches from a Native Hawaiian perspective. Educ Res. 2004;33(9):26–32. doi: 10.3102/0013189x033009026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaholokula JK, Okamoto SK, Yee BW. Special issue introduction: Advancing native Hawaiian and other pacific islander health. Asian Am J Psychol. 2019;10(3):197–205. doi: 10.1037/aap0000167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcus MA, Westra HA, Eastwood JD, Barnes KL. What are young adults saying about mental health? an analysis of internet blogs. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Look M, Trask-Batti M, Agres R, Mau M, Kaholokula J. Honolulu, HI: Center for Native and Pacific Health Disparities Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCubbin LD. Resilience among Native Hawaiian Adolescents: Ethnic Identity, Psychological Distress and Well-Being. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin, Madison; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mokuau N, Braun KL, Daniggelis E. Building family capacity for Native Hawaiian women with breast cancer. Health Soc Work. 2012;37(4):216–224. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hls033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGregor DP, Morelli PT, Matsuoka JK, Rodenhurst R, Kong N, Spencer MS. An ecological model of Native Hawaiian well-being. Pac Health Dialog. 2003;10(2):106–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mokuau N. Culturally based solutions to preserve the health of Native Hawaiians. J Ethn Cult Divers Soc Work. 2011;20(2):98–113. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2011.570119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antonio MC, Hishinuma ES, Ing CT, et al. A resilience model of adult Native Hawaiian Health utilizing a newly multi-dimensional scale. Behav Med. 2020;46(3–4):258–277. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2020.1758610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burrage RL, Antone MM, Kaniaupio KN, Rapozo KL. A culturally informed scoping review of Native Hawaiian mental health and emotional well-being literature. Indigenous Health Equity and Wellness. 2021:15–27. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2020.1770656. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMullin J. The call to life: Revitalizing a healthy Hawaiian identity. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(4):809–820. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gone JP. The Red Road to Wellness: Cultural Reclamation in a native first nations community treatment center. Am J Community Psychol. 2010;47(1–2):187–202. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gone JP. Redressing first nations historical trauma: Theorizing mechanisms for indigenous culture as mental health treatment. Transcult Psychiatry. 2013;50(5):683–706. doi: 10.1177/1363461513487669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brave Heart MY. The historical trauma response among natives and its relationship with substance abuse: A Lakota illustration. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):7–13. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan-Myrth N. Health Research in indigenous communities: Overcoming anthropology’s colonial legacy. Pract Anthropol. 2004;26(4):3–7. doi: 10.17730/praa.26.4.g144423p1k789t34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kukutai T, Taylor J. Kukutai T, Taylor J, editors. Data sovereignty for Indigenous Peoples: Current Practice and future needs. Indigenous Data Sovereignty. 2016. [DOI]

- 30.Phan N. Native Hawaiian Survey. 2019. Accessed November 5, 2023. www.nhsurvey.org.

- 31.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385. doi: 10.2307/2136404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Subica AM, Aitaoto N, Link BG, Yamada AM, Henwood BF, Sullivan G. Mental Health Status, need, and unmet need for mental health services among U.S. Pacific Islanders. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(7):578–585. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quinn M, Robinson C, Forman J, Krein SL, Rosland A-M. Survey instruments to assess patient experiences with access and coordination across Health Care Settings. Medical Care. 2017;55(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haunani-Kay T. The struggle for Hawaiian sovereignty: Introduction. Cult Surv Q. 2000;24(1):8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atske S. Social media use in 2021. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech.; 2022. Published May 11, Accessed January 28, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/ [Google Scholar]