Abstract

Catalytic poly(ADP-ribose) production by PARP1 is allosterically activated through interaction with DNA breaks, and PARP inhibitor compounds have the potential to influence PARP1 allostery in addition to preventing catalytic activity. Using the benzimidazole-4-carboxamide pharmacophore present in the first generation PARP1 inhibitor veliparib, a series of eleven derivatives was designed, synthesized, and evaluated as allosteric PARP1 inhibitors, with the premise that bulky substituents would engage the HD regulatory domain and thereby promote PARP1 retention on DNA breaks. We found that core scaffold modifications could indeed increase PARP1 affinity for DNA; however, the bulk of the modification alone was insufficient to trigger PARP1 allosteric retention on DNA breaks. Rather, compounds eliciting PARP1 retention on DNA breaks were found to be rigidly held in a position that interferes with a specific region of the HD domain, a region that is not targeted by current clinical PARP inhibitors. Collectively, these compounds highlight a unique way to trigger PARP1 retention on DNA breaks and open a path to unveil the pharmacological benefits of such inhibitors with novel properties.

Keywords: PARP1, veliparib analogs, allostery, HXMS, X-ray crystallography

Introduction

The catalytic activity of PARP1 is associated with DNA damage detection and repair among other cellular functions [1–3]. PARP1 uses substrate NAD+ to catalyze the formation of poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) chains of varying sizes on acceptor protein residues such as Asp and Glu, and in the presence of histone PARylation factor 1 (HPF1), Ser residues [4–7]. Target proteins that commonly undergo PARylation include PARP1 itself and histones. PAR chains exert diverse structural and functional effects on target proteins. Moreover, PAR chains favor the recruitment of DNA repair proteins such as DNA polβ, OGG1, PCNA, condensin I, DNA ligase III and XRCC1 [8, 9].

PARP1 is a multi-domain enzyme. It comprises three zinc fingers (Zn1, Zn2 and Zn3), a BRCT domain (BRCA1 C-terminus), a WGR (Trp-Gly-Arg) domain, and a catalytic domain (CAT). The CAT domain is composed of two sub-domains; the regulatory helical domain (HD) and the ADP-ribosyltransferase (ART) domain, which contains the active site. The conjoint action of PARP1 DNA binding domains (Zn1–3 and WGR) allows for the recognition of DNA strand breaks, which allosterically opens the HD and reveals the active site within the ART domain, effectively triggering PARP1 catalytic activity [10–12]. PARP1 can auto-modify itself with PAR chains in the vicinity of the BRCT domain [13]. Interestingly, the BRCT domain was recently found to interact with intact DNA and thus contributes to PARP1 scanning of intact chromatin [14].

Several PARP inhibitors (PARPi) have been developed for the treatment of cancer by way of combination treatment to potentiate chemo- [15], radio- [16, 17], and immune-therapy [18]. Most importantly, they have been used as monotherapy that exploits cancer cell-specific defective double-strand break (DSB) repair as observed in cells carrying BRCA1/2 mutations (a concept referred to as synthetic lethality) [19]. Consequently, four PARPi (olaparib, niraparib, rucaparib and talazoparib) are FDA-approved for the treatment of ovarian, breast, prostate, and pancreatic cancer [20].

These inhibitors impact PARP1 dynamics on DNA breaks in various ways. PAR chain production from PARP1 recruits DNA repair factors to process the breaks and favors the release of PARP1 from damage sites [21, 22]. Inhibitors are therefore prone to prevent PARP1 release from DNA damage, simply because they prevent PAR chain production by outcompeting substrate NAD+. As a result, PARPi treatment can lead to the accumulation of PARP1 in the chromatin bound fraction. This phenomenon, termed “PARP trapping”, is thought to be the driving force of the synthetic lethality observed in cells bearing defects in DNA repair [19, 23–26]. However, our recent work demonstrated that inhibitors can also control PARP1 allosteric communication in different ways that can impact PARP1 affinity for DNA breaks (Fig. 1A) [27]. Inhibitors that destabilize the HD can invoke PARP1 allostery in a manner that strengthens PARP1 interaction with DNA strand breaks and are referred to as Type I inhibitors [27]. Type II inhibitors have no (or a minor) effect on PARP1 allostery and do not impact DNA binding affinity. Type III inhibitors have an impact on PARP1 allostery that weakens PARP1 interaction with DNA breaks. Therefore, it appears that PARP trapping induced by PARPi may be more accurately described as being the result of both PARP1 inhibition and modulation of PARP1 allostery [27]. As such, inhibitors that specifically impact PARP1 allostery represent a promising new dimension in the development of next generation PARPi [27].

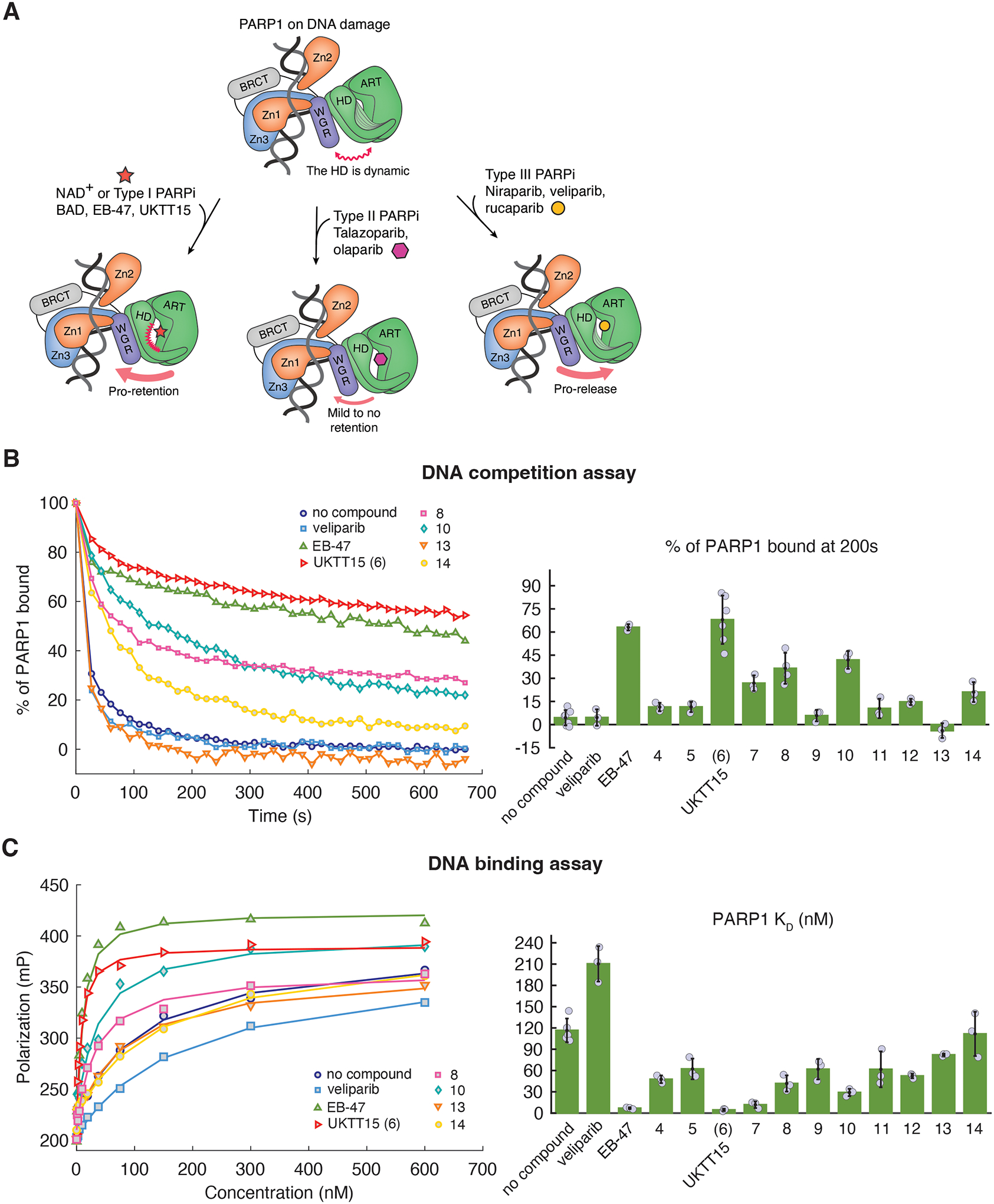

Figure 1. Veliparib core scaffold modifications modulate PARP1 allostery.

(A) PARP1 binding to DNA damage allosterically renders the HD subdomain dynamic and reveals the active site (top). The active site occupancy modulates PARP1 allostery, with substrate NAD+ or Type I inhibitors promoting PARP1 retention to breaks (left). Type II inhibitors mildly or do not promote retention (middle) and type III inhibitors promote PARP1 release from breaks (right). (B) (left panel) Representative FP DNA competition assay that measures PARP1 retention on a fluorescently labeled DNA break in the presence of unlabeled competitor DNA. UKTT15 (6) increases PARP1 retention on DNA damage, similar to EB-47, and in contrast to PARP1 in the absence of inhibitor. Compounds 8, 10, and 14 have a milder effect while compound 13 does not appear to promote PARP1 retention and might even disfavor retention (see Fig. S5 for additional representative curves). (right panel) The percentage of PARP1 still retained at 200 s is plotted. The bars represent the average values from at least three independent experiments, and the individual measurements are plotted. The error values represent the calculated standard deviations. The values are reported in Table 1 and 2. (C) Representative FP DNA binding assay showing that UKTT15 (6) increases PARP1 DNA binding affinity. Again, compounds 10 and 8 mildly increase PARP1 affinity while compounds 13 and 14 show little to no difference (see Fig. S5 for additional representative curves). The lines represent the fit of a 1:1 binding model to the data. (right panel) KD values derived from the FP DNA binding assay are plotted. The bars represent the average of at least three independent experiments. The reported errors are the calculated standard deviations. The values are reported in Table 1 and 2.

In this study, we describe our efforts to modify the allosteric properties of veliparib, a benzimidazole-4-carboxamide derivative that is a potent catalytic inhibitor of PARP1 [28–30]. Veliparib is considered a weak PARP trapper in terms of moving PARP1 to the insoluble chromatin fraction, and it exhibits Type III behavior that weakens PARP1 interaction with DNA breaks [25, 27]. Inspired by the potent enzyme inhibition produced by the benzimidazole-4-carboxamide scaffold alone (Ki = 95 nM) [31], novel derivatives of this scaffold were designed and synthesized to accomplish an improved in vitro profile as compared to veliparib, in particular with the goal of engineering Type I behavior. We hypothesized that the Type III properties of veliparib could be attributed to its relatively small size in relation to the other clinically established drugs, therefore explaining its inability to destabilize the HD and strengthen PARP1 DNA binding affinity. We anticipated that elaboration of substitutions on the benzimidazole-4-carboxamide scaffold could produce inhibitors triggering PARP1 allostery, thereby increasing PARP1 retention ability on DNA breaks. The structural insight gained during this study led to the identification and reporting of UKTT15 (6) that exhibited strong Type I behavior [27]. However, several compounds synthesized during this endeavor were also investigated. Here, we report on the impact of this compound collection on PARP1 allostery and dynamics using biochemical assays of DNA binding, and hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HXMS) analysis of PARP1 dynamics. The results indicated that increased molecular size is necessary but not sufficient to elicit Type I behavior. X-ray crystallographic analysis supports a model in which PARPi extensions need to be rigidly held in a position to interfere with the HD domain, and that different regions of the HD can be targeted to elicit Type I behavior.

Results and Discussion

Chemical synthesis

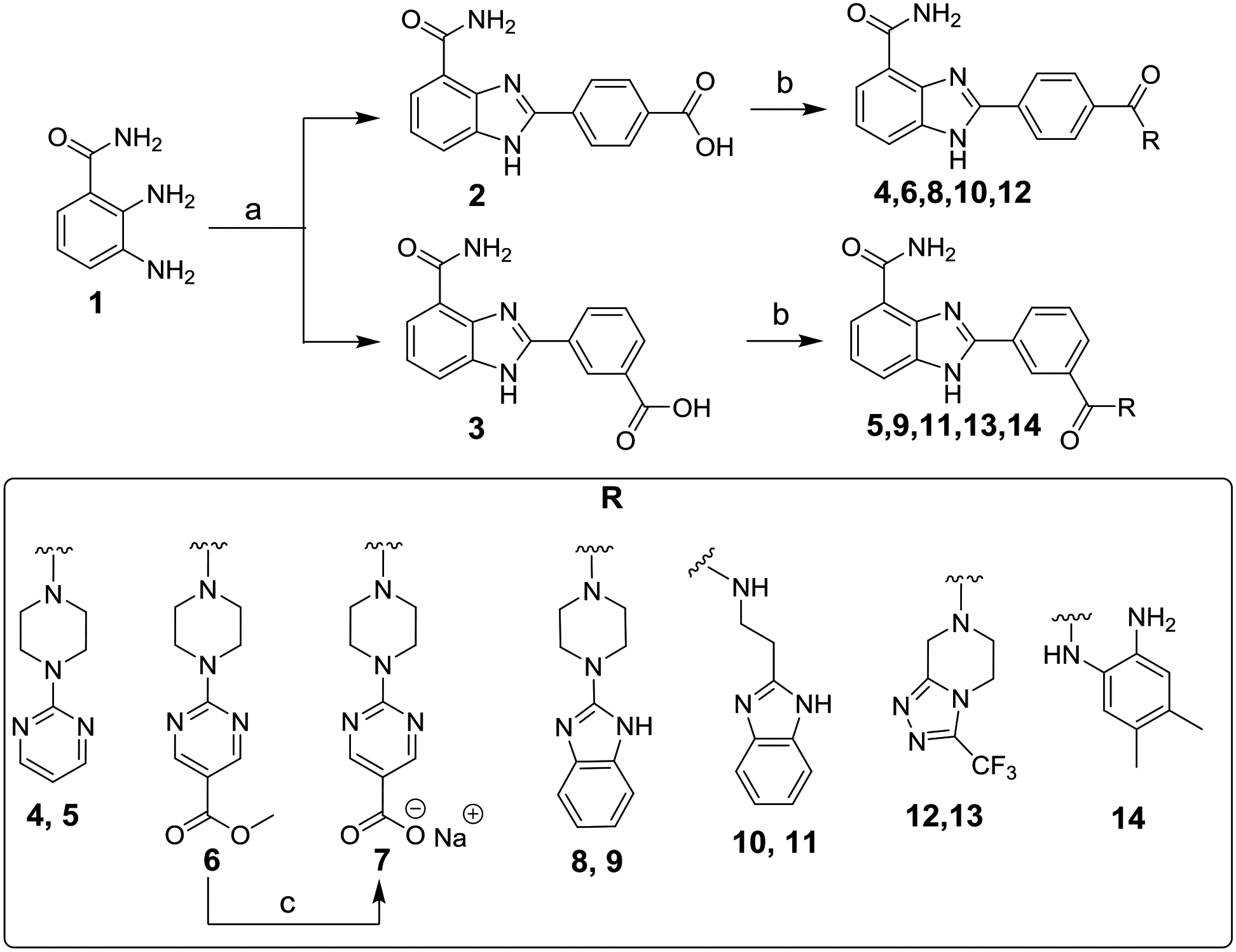

Commercially available 2,3-diaminobenzamide (1) underwent cyclization with 4-formylbenzoic acid or 3-formylbenzoic acid to obtain para-carboxy intermediate 2 or meta-carboxy intermediate 3, respectively (Scheme 1). The reaction may have proceeded via ammonium acetate-assisted imine formation and subsequent spontaneous cyclization driven by the formation of more stable substituted benzimidazole products. The 4-carboxy analogue 2 (PARP1 Ki = 290 nM) reported by White and co-workers [32] showed three-fold lower affinity than the benzimidazole-4-carboxamide core itself (Ki = 95 nM). Based on the knowledge acquired from a previous report [33], we introduced extended substituents on the benzimidazole-4-carboxamide scaffold that could possibly introduce steric clashes with the HD and thereby modulate PARP1 allostery and retention on DNA breaks. Consequently, the carboxy derivatives 2 or 3 were coupled to various amines using HBTU as the coupling reagent, to obtain analogues 4-6 and 8-14 with 23–63% yields. Hydrolysis of the ester in 6 in the presence of sodium hydroxide resulted in a carboxylic acid in its sodium salt form in 7. The structures of target compounds were confirmed by 1H NMR and HRMS and for 5, 8-10, 13, and 14 additionally by 13C NMR. The spectral data are reported in Fig. S1, S3, and S2, respectively.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Target Compounds 4–14.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 4-formylbenzoic acid for 2 or 3-formylbenzoic acid for 3, NH4OAc, DMF, 100 °C, 6 h, 86–89%; (b) appropriate amine, EtN(i-Pr)2, HBTU, DMF, overnight, 23–63%; (c) NaOH, THF/H2O (1:1), rt, overnight, 49%.

Biochemical analysis of pro-retention behavior on DNA damage

The catalytic inhibition of all target compounds was analyzed using a PARP1 enzyme assay (BPS Bioscience, San Diego, CA) and their potency was largely comparable to the inhibition demonstrated by veliparib, except for compound 11 which showed a ~100-fold decrease in potency (Fig. S4). PARP1 affinity toward a DNA break in the presence of target compounds was assessed via an equilibrium binding constant (KD) obtained with a fluorescence polarization (FP) DNA binding assay performed in solution (Fig. 1C). In addition, we used an FP DNA competition assay to test the ability of target compounds to promote PARP1 retention on DNA in the presence of competitor DNA breaks in solution (Fig. 1B). An SDS-PAGE activity assay (Fig. S5) was conducted to ensure that saturating amounts of target compounds were used in both FP assays. Tables 1 and 2 report the results obtained for all target compounds with the PARP1 enzyme assay, DNA binding affinity assay, and DNA competition assay.

Table 1. Para-extension of the benzimidazole-4-carboxamide scaffold and its impact on in vitro PARP1 inhibition potency, PARP1 DNA damage binding affinity and retention.

PARP1 IC50 values were derived from the average values of at least two independent experiments. Average KD values of DNA bound PARP1 in the presence and absence (no inhibitor) of target compounds (FP DNA binding assay) and average percentage of PARP1 bound at 200 s (FP DNA competition assay). Both KD values and percentage are averages of at least three independent experiments.

| Extension |

|

|

|

|

|

|

NA | NA | NA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | 4 | UKTT15 (6) | 7 | 8 | 10 | 12 | EB-47 | Veliparib | no compound |

| PARP1 IC50 (nM) | 11.9 | 2.8 | >10 (37% at 10 nM) | 6.2 | 3.1 | 25.4 | ND | 1.3 | NA |

| DNA competition assay (% of PARP1 bound at 200 s) | 11.4 ± 2.8 | 68.0 ± 15.7 | 26.8 ± 5.1 | 36.5 ± 10.0 | 42.5 ± 4.9 | 14.7 ± 2.0 | 63.0 ± 2.0 | 4.6 ± 5.3 | 4.4 ± 5.0 |

| DNA binding assay (KD of PARP1 in nM) | 47.7 ± 5.4 | 4.5 ± 1.7 | 11.8 ± 4.7 | 41.7 ± 11.4 | 29.0 ± 5.2 | 52.3 ± 3.2 | 6.9 ± 1.2 | 210.3 ± 25.0 | 116.6 ± 16.8 |

Table 2. Meta-extension of the benzimidazole-4-carboxamide scaffold and its impact on in vitro PARP1 inhibition potency, PARP1 DNA damage binding affinity and retention.

IC50 values were derived from the average values of at least two independent experiments. Average KD values of DNA bound PARP1 in the presence and absence (no inhibitor) of target compounds (FP DNA binding assay) and average percentage of PARP1 bound at 200 s (FP DNA competition assay). Both KD values and percentage are averages of at least three independent experiments. NA – not applicable. ND – not determined.

| Extension |

|

|

|

|

|

NA | NA | NA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | 5 | 9 | 11 | 13 | 14 | EB-47 | Veliparib | no compound |

| PARP1 IC50 (nM) | 8.9 | 3.9 | 121 | 25.4 | 17.3 | ND | 1.3 | NA |

| DNA competition assay (% of PARP1 bound at 200 s) | 11.4 ± 3.4 | 5.8 ± 3.7 | 10.5 ± 6.3 | 3.9 ± 4.8 | 21.0 ± 6.4 | 63.0 ± 2.0 | 4.6 ± 5.3 | 4.4 ± 5.0 |

| DNA binding assay (KD of PARP1 in nM) | 62.2 ± 14.6 | 61.9 ± 14.4 | 61.7 ± 25.3 | 82.1 ± 1.8 | 111.6 ± 31.2 | 6.9 ± 1.2 | 210.3 ± 25.0 | 116.6 ± 16.8 |

We began with installation of the pyrimidin-2-yl-piperazine at the 4-carboxy group to obtain 4 with approximately nine-fold decrease in the PARP1 inhibition compared to veliparib. Compound 4 did not display significant DNA retention phenotype although it mildly increased PARP1 DNA binding affinity. The equivalent substituent at the 3-carboxy group led to 5, which also did not display any pro-retention phenotype and increased PARP1 DNA binding affinity to a lesser extent than compound 4. Next, we introduced a methyl ester group on the pyrimidine ring to potentially destabilize the HD and trigger PARP1 allostery due to the bulkiness and electronegative property of the substituent.

Adding a methyl ester group at the C5-position of the pyrimidine ring of 4 led to UKTT15 (6), with PARP1 inhibitory activity that was comparable to veliparib. We recently published the allosteric mechanism of UKTT15 (6) that increases PARP1 retention on DNA breaks [27]. However, the study did not include the synthesis and structure-property analysis of a set of compounds related to UKTT15 (6), as discussed in this study. When tested, UKTT15 (6) drastically increased PARP1 retention on DNA breaks akin to other Type I PARPi such as BAD and EB-47, two NAD+ analogs [34, 35]. PARP1 DNA binding affinity in the presence of UKTT15 (6) was also greatly increased. Hydrolysis of the methyl ester group led to compound 7, which promoted a rather mild DNA pro-retention phenotype compared to UKTT15 (6). Given that compounds 4, 6 and 7 all share the same pyrimidin-2-yl-piperazine motif, it appears that the addition of a non-hydrolyzed methyl ester group is essential to trigger the intense pro-retention phenotype seen with UKTT15 (6).

An alternative isostere of pyrimidin-2-yl-piperazine was incorporated in the form of a benzimidazol-2-yl-piperazine motif either in para-(8) or meta-(9) position. Compound 8 showed a good retention phenotype, while its meta-counterpart did not. Interestingly, it appears that both para- and meta-substituted compounds increased PARP1 DNA binding affinity to the same extent despite their different retention phenotype. Although compound 8 showed a promising retention phenotype, it did not recapitulate the level of retention seen with UKTT15 (6).

Replacement of the piperazine motif for a more flexible ethylamine motif led to compound 10. Compound 10 displayed a slightly increased PARP1 DNA binding affinity and promoted DNA retention in a manner that is similar to its rigid counterpart 8. Again, compound 10 meta-counterpart (compound 11) did not display the same phenotype.

We reasoned that introducing a rigid and bulky substituent either in the para- or meta-position could potentially induce allosteric clashes with the HD, subsequently destabilizing its structure to drive PARP1 allostery. Another isostere of pyrimidin-2-yl-piperazine was incorporated in the form of 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazine (with electronegative -CF3 substitution), which led to compound 12 in the para- and 13 in the meta-position. Interestingly, both compounds showed a four-fold decrease in PARP1 inhibitory activity and did not display pro-retention ability. Despite the presence of an electronegative group (-CF3) in 12 and 13, these derivatives did not recapitulate the level of retention seen with UKTT15 (6). Of note, compound 12 demonstrated very poor aqueous solubility, which could have negatively influenced its phenotype.

Compound 14, bearing a unique 4,5-dimethyl-ortho-aminobenzamide substituent at the meta-position also showed PARP1 enzyme inhibition that was comparable to the analogues discussed above. However, compound 14 was only found to mildly promote PARP1 retention and did not significantly increase PARP1 DNA binding affinity. Taken together, these results suggested that the position of bulky substituents on the veliparib core plays an important role in determining the capacity to allosterically retain PARP1 on DNA breaks.

Crystal structures of target compounds bound to PARP1

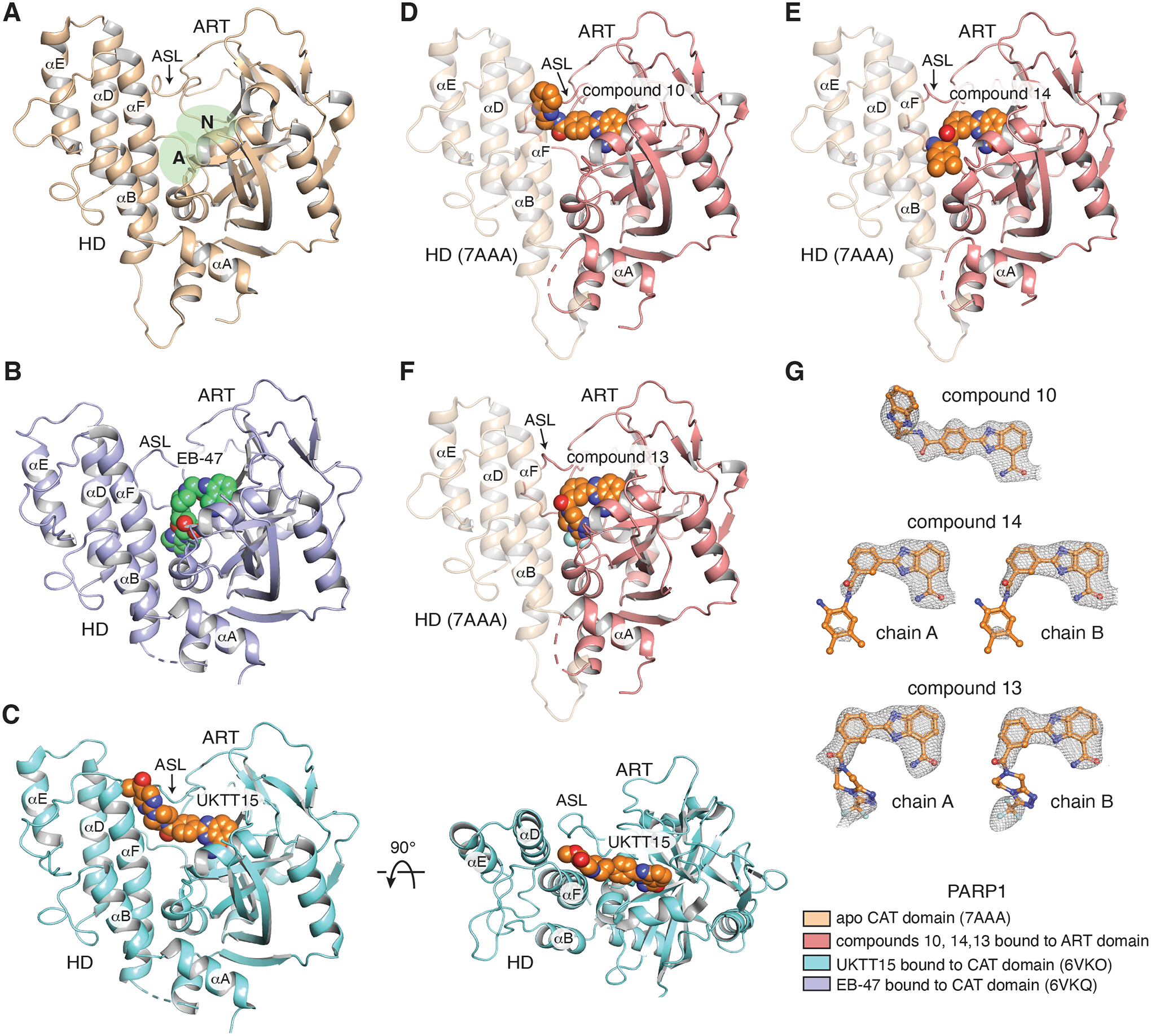

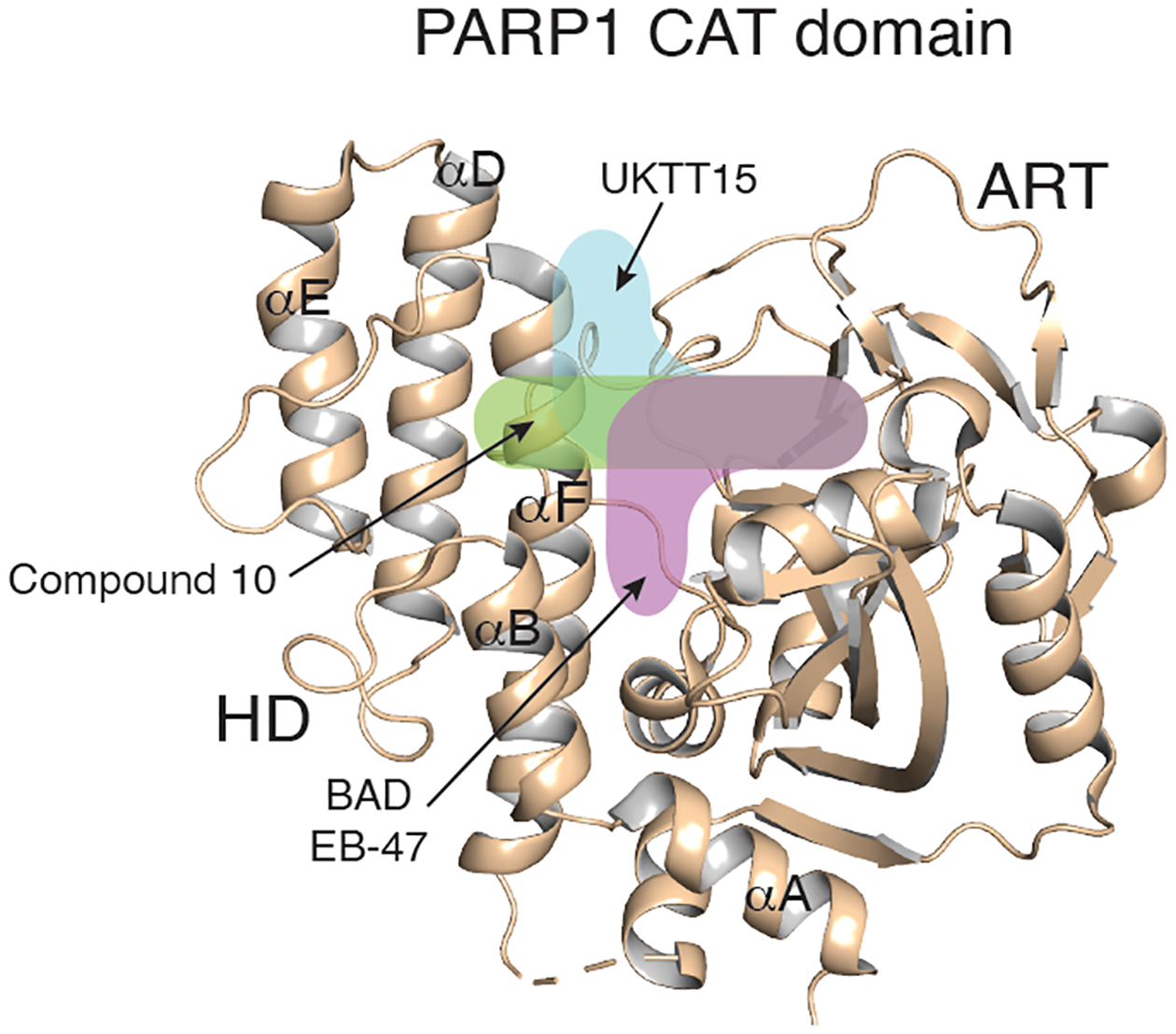

Next, we employed X-ray crystallography to gain insights into target compound binding poses in the PARP1 active site. The active site pocket of PARP1 is located in the ART domain and is composed of two distinct binding sites: the nicotinamide (N) binding pocket and the adenosine (A) binding pocket (Fig. 2A) [36]. PARPi that contact both of these two sites include EB-47 (Fig. 2B) [27], BAD [35], and olaparib [37], while veliparib being a relatively small compound only contacts the N binding pocket [37]. Talazoparib [37], niraparib [38], and rucaparib [27] all protrude from the N binding pocket and abut the central region of helix αF in the HD. The Type I behavior of EB-47 and BAD derives from their ability to engage the A binding pocket in close proximity to the base of helix αF [27, 35]. We anticipated that the veliparib derivatives with Type I behavior might also engage the A site.

Figure 2. Crystal structures of target compounds bound to PARP1 ART domain.

(A) Crystal structure of the human PARP1 CAT domain with no inhibitor bound (beige, PDB: 7AAA). The nicotinamide binding pocket (N) and adenosine binding pocket (A) of the active site are highlighted in green. The HD and ART subdomains are labeled. The location of the active site loop (ASL) is labeled and noted with an arrow. Helices of the HD are labeled. (B) Crystal structure of EB-47 (green) bound to PARP1 CAT domain (purple, PDB: 6VKQ). EB-47 contacts both N and A binding pockets of the active site. (C) (left panel) Crystal structure of UKTT15 (6) (orange) bound to PARP1 CAT domain (blue, PDB: 6VKO). UKTT15 (6) does not contact the A binding pocket, but rather occupies a pocket in between helix αF and αD in the HD and the active site loop (ASL) in the ART domain (right panel). (D, E, F) Crystal structures of compounds 10 (D), 14 (E) and 13 (F) (orange) bound to their respective PARP1 ART domain (pink). The semi-transparent HD of PARP1 is represented after having overlayed the structure of PARP1 CAT domain (beige, PDB: 7AAA). (G) Compounds 10, 14 and 13 with a 2FO-FC weighted electron density contoured at 1 σ overlaid on each copy of the compounds found in their respective structures. The color coding for the displayed structures is shown at the bottom right.

We attempted co-crystallization of compounds 10, 13, and 14 with the PARP1 ART domain, thus representing the minimal catalytic region. Crystals of the compound 14/ART complex diffracted to 2.7 Å resolution and contained 2 complexes per asymmetric unit, and crystals of the compound 13/ART complex diffracted to 3.4 Å resolution, also with 2 complexes per asymmetric unit (Table 3). Both structures indicated that the core scaffold of the inhibitor is firmly anchored in the N binding pocket, but that their respective substituents are not stably engaged in binding given the non-continuous electron density of these molecules (Fig. 2E, F, G). Accordingly, the substituents of both compounds also display high crystallographic B-factors relative to their respective compound core, which indicates that both substituents have a high degree of motion relative to a more stable core. Of note, the non-continuous electron density of the compounds cannot be attributed to spatial constraints in the crystal packing environment that might prohibit interactions with the A pocket in the ART domain, as the A pocket remains accessible in the crystal lattice (Fig. S6A, B). Therefore, we surmise that the poor pro-retention behavior of compounds 14 and 13 stems from their flexible interaction with the ART domain, which does not support HD structural changes.

Table 3.

| Data Collectiona | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PARP1 ART domain + UKTT5 (compound 10) | PARP1 ART domain + UKTT10 (compound 13) | PARP1 ART domain + UKTT22 (compound 14) | PARP1 ΔVE/DNA in complex with UKTT5 (compound 10) | |

| PDB ID | 8FYY | 8FYZ | 8FZ1 | 8G0H |

| Space Group | P6122 | P61 | P61 | P21 |

| Unit Cell Dimensions | a=92.7 Å b=92.7 Å c=136.4 Å α=90.0°, β=90.0°, γ=120.0° |

a=95.9 Å b=95.9 Å c=130.7 Å α=90.0°, β=90.0°, γ=120.0° |

a=95.6 Å b=95.6 Å c=128.8 Å α=90.0°, β=90.0°, γ=120.0° |

a=108.1 Å b=110.2 Å c=117.1 Å α=90.0°, β=114.5°, γ=90.0° |

| 1 molecule / asu | 2 molecules / asu | 2 molecules / asu | 2 molecules / asu | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 |

| Resolution (Å) | 80.3–2.8 (2.95–2.80) | 47.9–3.4 (3.67–3.40) | 47.8–2.7 (2.83–2.70) | 110.17–3.80 (4.06–3.80) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (100.0) | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.9 (99.9) | 99.6 (99.4) |

| Ave. redundancy | 7.0 (6.9) | 19.8 (18.2) | 4.5 (4.5) | 4.7 (4.9) |

| Mean (I/σI)b | 7.6 (1.8) | 7.9 (2.2) | 10.3 (1.7) | 6.1 (0.7) |

| Rmerge (%)b | 23.4 (102.7) | 4.8 (202.3) | 9.9 (79.7) | 16.2 (264.2) |

| Rpim (%)b | 9.2 (41.2) | 1.1 (49.0) | 5.1 (41.8) | 8.1 (131.0) |

| Mean I CC(1/2)b | 0.989 (0.764) | 0.977 (0.474) | 0.997 (0.723) | 0.998 (0.266) |

| Model Refinement a | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 39.6–2.8 (3.21–2.80) | 47.9–3.4 (3.89–3.40) | 47.8–2.7 (2.87–2.70) | 76.59–3.80 (3.95–3.80) |

| # reflections | 8,997 (872) | 9,273 (962) | 18,418 (1,856) | 24,664 (1,286) |

| Rcrystc | 0.199 (0.274) | 0.219 (0.324) | 0.191 (0.285) | 0.257 (0.407) |

| Rfreec | 0.273 (0.315) | 0.267 (0.377) | 0.231 (0.360) | 0.312 (0.383) |

| # atoms / average B (Å2) | 1,958 / 46.1 | 3,857 / 78.8 | 3,919 / 68.6 | 11,487 / 196.7 |

| protein | 1,874 / 45.8 | 3,731 / 78.3 | 3,723 / 67.9 | 11,025 / 197.0 |

| DNA | - | - | - | 398 / 193.3 |

| solvent | 52 / 61.6 | 60 / 83.3 | 136 / 82.9 | - |

| ligand | 32 / 42.8 | 66 / 98.7 | 60 / 82.0 | 64 / 169.8 |

| Phi/Psi (%) / outliers (#)d | 97.4 / 0 | 95.7 / 0 | 96.6 / 0 | 92.2/ 1 |

| Rmsd angles (°) | 0.628 | 0.592 | 0.889 | 0.511 |

| Rmsd lengths (Å) | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.002 |

Values in parentheses refer to data in the highest resolution shell.

As calculated in SCALA [46]: is the mean intensity of j observations of reflection hkl and its symmetry equivalents; Rpim takes into account measurement redundancy when calculating Rmerge; Mean I CC(1/2) is the correlation between mean intensities calculated for two randomly chosen half-sets of the data.

Rfree = Rcryst for 5% of reflections excluded from crystallographic refinement.

As reported in MolProbity [55].

The co-crystal structure of UKTT15 (6) with the PARP1 ART domain was previously published [27]. The co-crystal structure revealed that while compound UKTT15 (6) was indeed interacting with the N pocket, it was not bound to the A pocket as observed for EB-47 and BAD. Rather, compound UKTT15 (6) extends towards the active site loop (ASL) of the ART domain, a binding pose that would presumably severely clash with the HD. The co-crystal structure of compound UKTT15 (6) with the complete CAT domain showed the compound extending to a position between helices αF and αD of the HD and the ASL region located in the ART (Fig. 2C) [27]. Helix αF bent slightly to accommodate the inhibitor. This surprising and unexpected binding mode could explain the UKTT15 ability to trigger PARP1 allostery by means of destabilizing the HD, given the poor electron density observed for the HD subdomain in the crystal structure. Mutations made on the C-terminal region of helix αF that disrupt the Type I behavior of EB-47 did not impact the increased retention of PARP1 on DNA breaks induced by UKTT15 (6), which supported that the compound is indeed interacting with the N-terminal portion of helix αF [27]. We expect that the lower pro-retention ability of compound 7 could derive from the fact that a hydrolyzed methyl ester group bearing a negative charge cannot be easily accommodated in the groove formed in between the ASL and the helices of the HD.

The co-crystal structure of compound 10 (2.8 Å resolution, 1 molecule per asymmetric unit; Table 3) bound to the ART domain revealed a similar binding mode to UKTT15 (6), with the benzimidazole moiety extending towards the ASL (Fig. 2D). Of note, the electron density of compound 10 appears continuous throughout the inhibitor (Fig. 2G). We expected that, in the presence of the HD, compound 10 would abut the N-terminal portion of helix αF, explaining its somewhat similar effect as compound UKTT15 (6) in terms of pro-retention ability. However, analysis of crystal packing in the compound 10/ART domain structure revealed that 10 contacts another compound 10 from a symmetry-related molecule, which could contribute to the specific conformation of the ligand observed in this crystal (Fig. S6C).

To address how compound 10 contacts the HD domain, we solved the crystal structure of compound 10 bound to an assembly of PARP1 domains in which the CAT domain contained a two-residue deletion in helix αB of the HD: ΔVal687-Glu688 (referred to as ΔVE) [39, 40]. The ΔVE mutant was recently used to investigate PARP1 allosteric communication, since it favors the active PARP1 conformation [40]. The crystal structure of a PARP1 domain assembly bearing the ΔVE mutation and bound to DNA damage displayed two major structural differences when compared to the apo CAT domain, and these two differences appear indicative of the PARP1 active state (Fig. S7A) [40]. First, the ΔVE structure displays the formation of an additional WGR-HD interface, which is essential to relay the allosteric pro-retention signal (Fig. S7A, insert 1). Second, the ΔVE structure shows a concerted rotation of the ART domain that reveals the active site (Fig. S7A, insert 2). These structural changes allowed Type I inhibitor EB-47 to bind in the catalytic pocket [40], and this binding had never been observed with the wild-type structures that do not represent the active conformation [12]. Therefore, the ΔVE mutant was used to gain further insight on the influence of 10 on PARP1 allostery and other regulatory domains involved in this phenomenon.

PARP1 ΔVE in complex with compound 10 was crystallized using a minimal assembly of PARP1 domains (i.e. Zn1, Zn3, WGR and CAT domains) [40]. Crystals of the compound 10/ΔVE complex diffracted to 3.9 Å (Fig. 3A; 2 molecules per asymmetric unit, Table 3). Interestingly, the crystal structure of ΔVE in the presence of compound 10 appears very similar to the crystal structure of the ΔVE mutant in the absence of an active site ligand (Fig. S7B). Of note, binding of EB-47 in the active pocket of ΔVE also did not induce any major conformational change [40] and hints that both ligands are compatible with the open conformation of PARP1 and the pro-retention state.

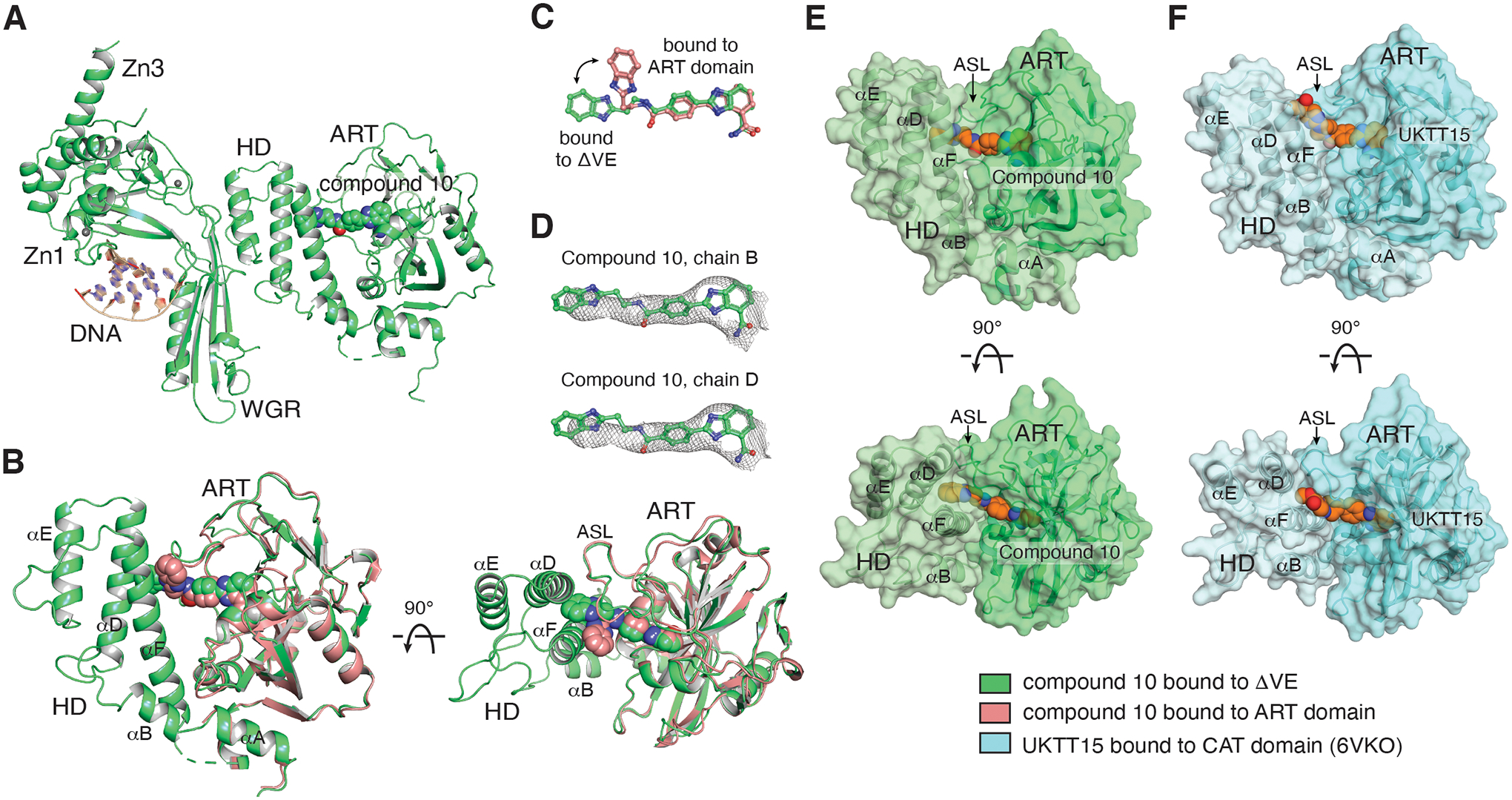

Figure 3. Compound 10 contacts helices αD and αF of the HD.

(A) The compound 10/ΔVE structure (green) was determined at 3.9 Å (one of the two complexes in the asymmetric unit is shown). (B) The compound 10/ART domain structure (pink) is superposed on the CAT domain of the ΔVE structure, highlighting that the compound contacts helices αD and αF of the HD following a rearrangement of its benzimidazole moiety (panel C). (D) Compound 10 with a 2FO-FC weighted electron density contoured at 0.6 σ overlaid on the compounds from the two catalytic domain protein chains (B and D) found in the asymmetric unit. (E) Two orthogonal views of the surface representation of the CAT domain structure of compound 10 bound to ΔVE (derived from the structure in panel A), highlighting that the compound substituent is buried at the interface of helices αD and αF and the ASL. Compound 10 is drawn with orange carbons. (F) Two orthogonal views of the surface representation of the CAT domain structure of UKTT15 (6) bound to the CAT domain (blue, PDB 6VKO), highlighting that the compound contributes to a groove in between helices αD and αF and the ASL, and that the compound remains accessible to the solvent relative to compound 10 in panel E. UKTT15 (6) is drawn with orange carbons. The color coding for the displayed structures is shown at the bottom right.

The crystal structure of compound 10 bound to ΔVE shows that 10 has inserted itself in between the HD and the ASL following a repositioning of its benzimidazole moiety (Fig. 3B, C). Despite the low resolution of the crystal structure, which limits the precise modeling of the ligand binding geometry, the electron density is sufficiently clear to confirm the overall extended binding pose, as observed for both compounds in the asymmetric unit (Fig. 3D, S7C). Compound 10 contacts helices αD and αF in a manner that differs from UKTT15 (6), which could explain the milder phenotype of compound 10. While compound 10 extends towards the hydrophobic core of the HD and appears buried (Fig. 3E), UKTT15 (6) specifically abuts the very N-terminal portion of helix αF and is exposed to the solvent (Fig. 3F). Of note, we could not determine a crystal structure of UKTT15 (6) bound to the PARP1 ΔVE complex, but we surmise that UKTT15 (6) would likely adopt a similar binding pose. Taken together, these crystal structures highlight that compound 10 stably contacts both the ART domain and the HD. However, how this binding pose specifically affects other domains to modulate PARP1 allostery remains unclear.

HXMS and PARP1 dynamics in the presence of the target compounds

We next employed HXMS on PARP1 in the presence of a single-strand break and various PARPi. HXMS measures the exchange of backbone amide protons. As these protons can be in continuous exchange with the hydrogens from H2O in aqueous buffers, HXMS measures amide exchange with deuterons from buffers made with D2O (i.e., heavy water). Deuterated proteins are then proteolytically fragmented and separated for MS analysis to determine the amount of deuteration at different positions in the protein. For stably folded regions, including α-helices or the interior of β-sheets, transient local unfolding events are required to disrupt the hydrogen bonds involving amide protons. Thus, HXMS provides valuable information on local structure and dynamic changes in the protein. HXMS identified the allosteric communication that drives PARP1 activation upon binding to a DNA break [10]. Further, based on the reverse allostery induced by specific PARPi molecules, we reported an allosteric-based classification for PARPi (Fig. 1A): Type I (BAD, EB-47, and UKTT15(6)), Type II (talazoparib and olaparib) and Type III (niraparib, rucaparib, and veliparib) [27]. Here, we measured the potential allosteric communication driven by each of the three compounds 10, 13, and 14 and focused on the 100 s HX timepoint that was particularly helpful in our prior PARPi studies [27].

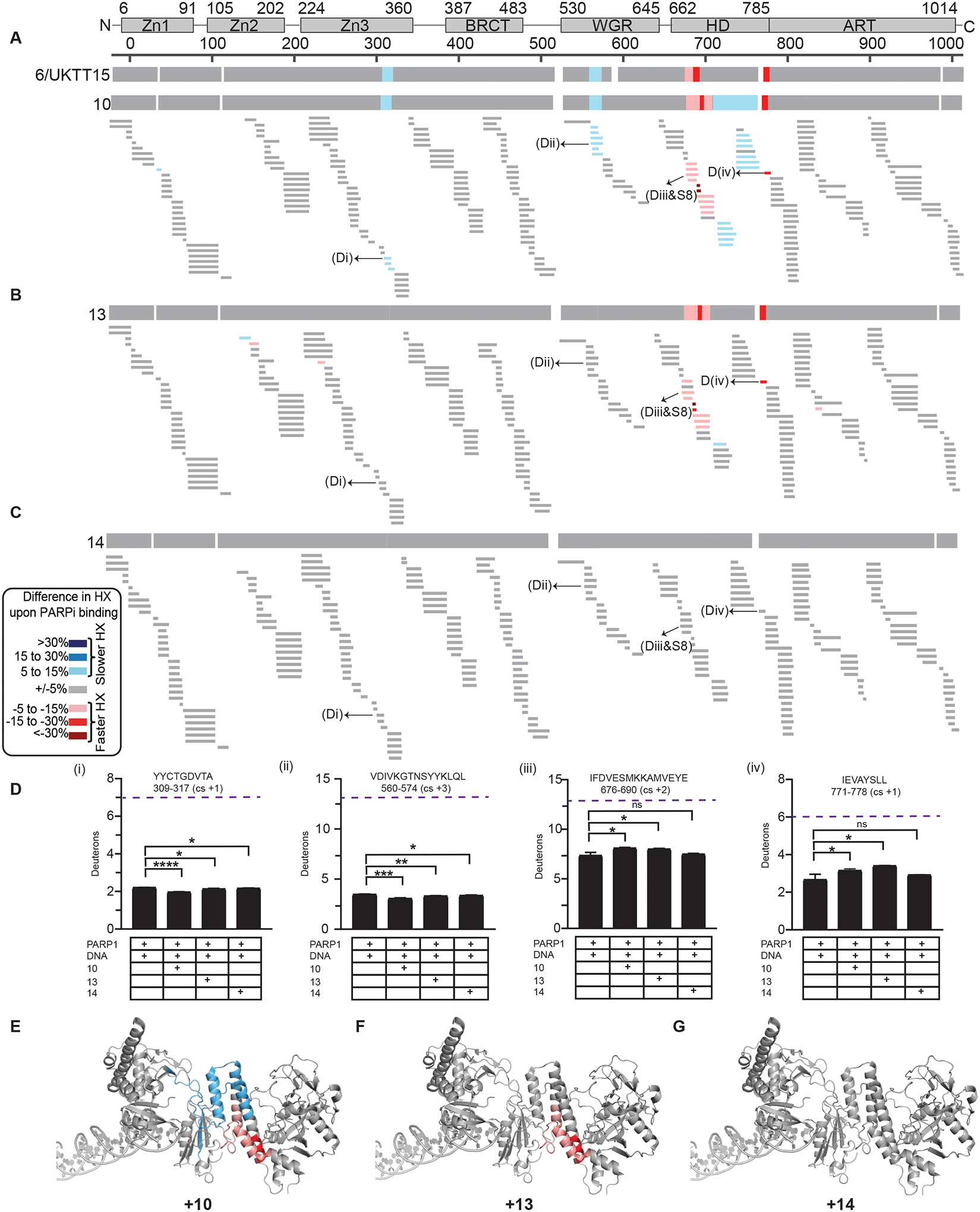

We found that compound 10 destabilized αB, the adjacent linker region, and the C-terminal portion of αF (Fig. 4A and S8), in a manner similar to that of UKTT15 (6) [27]. It also stabilized other regions of the HD, namely αD, αE, the N-terminal portion of αF, and nearby linker residues bridging these helices. Moreover, compound 10 appears to protect other regions of PARP1 such as portions of both the Zn3 and WGR domains (Fig. 4A, D, E, and S8). Indeed, similar HX behavior is conferred by EB-47 [27] and BAD [35] when PARP1 is bound to a DNA break: i.e., destabilizing the critical regions within HD (αB and αF helices) and strengthening the contacts between DNA-binding domain, WGR and HD. The ability to retain PARP1 on a DNA break, the slight increase in PARP1 DNA binding affinity (Fig. 1B–C), and our findings with HXMS collectively suggests that compound 10 is a Type I PARPi.

Figure 4. Hydrogen/deuterium exchange-mass spectrometry (HXMS).

(A) HXMS difference plots between PARP1/DNA complex and PARP1/DNA/10 complex at 100 s. The consensus HX difference plot for the binding of the 10 and UKTT15 (6) is shown on the top for comparison. (B) HXMS difference plots between PARP1/DNA complex and PARP1/DNA/13 complex at 100 s. The consensus HX difference plot for the binding of the 13 is shown on the top. (C) HXMS difference plots between PARP1/DNA complex and PARP1/DNA/14 complex at 100 s. The consensus HX difference plot for the binding of the 14 is shown on the top. For panels A-C, each thin horizontal bar represents a PARP1 peptide. (D) Panels (i-iv) represents the HX of the representative peptides of Zn3, WGR, αB, and αF for PARP1+DNA, and PARP1+DNA+PARPi. An average from three replicates with SD represented by error bars and asterisks indicating P < 0.05 from two-sided t-test between PARP1+DNA and PARP1+DNA+PARPi is shown. Purple dotted line indicates maxD i.e., number of residues minus first two residues (back-exchange within experimental timescale) and minus number of prolines due to no backbone amide hydrogen. Though no major changes in HX were observed for PARP1 in the presence of DNA and compound 14, the number of deuterons between PARP1+DNA complex and PARP1+DNA+compound 14 are statistically different for some peptides (e.g. Di and Dii) indicating that the PARPi is bound to PARP1 and exhibits some mild allostery which classifies as Type II behavior. (E) Consensus HXMS percentage differences with compounds 10 mapped to the crystal structure of PARP1 on DNA damage (PDB 4DQY). (F) Consensus HXMS percentage differences with compound 13 mapped to the crystal structure of PARP1 on DNA damage (PDB 4DQY). (G) Consensus HXMS percentage differences with compound 14 mapped to the crystal structure of PARP1 on DNA damage (PDB 4DQY).

Compound 13, on the other hand, displayed HX more consistent with a Type II inhibitor talazoparib (Fig. 4B, and S8) [27]. It confers modest deprotection of helix αB in the HD and the adjacent linker region that includes αC, and strong deprotection of the C-terminal portion of αF (Fig. 4B, D, F, and S8). Unlike compound 10, 13 did not strongly transmit towards the stability of DNA binding domains (Fig. 4B, D, and S8). A potential explanation for this observation is the non-continuous electron density due to flexible interaction with the ART, also evident from the X-ray crystallography study (Fig. 2G). Although compound 13 might appear to favor PARP1 release from DNA damage in the DNA competition assays (Fig. 1B and Table 2), it cannot be classified as a Type III inhibitor as it increases PARP1 affinity for DNA damage, in sharp contrast to veliparib (Fig. 1C and Table 2).

Compound 14 has yet a third outcome on the HX of PARP1. It neither destabilizes any regions of PARP1 HD (Fig. 4C, D, G, S8), nor markedly stabilizes the inter-domain contacts, reminiscent of the HX when PARP1 is bound to olaparib, a Type II inhibitor. We note that none of the target compounds exhibited protection of PARP1 active site peptides at the timepoint measured (100 s), which is consistent with what was observed with UKTT15 (6) and EB-47 at this early timepoint [27]. The behavior of compound 14 might be due to the non-equivalent binding relative to compound 10 and 13. Though the core scaffold of 14 is firmly making contacts at the N binding pocket, the respective substituent of the inhibitor has high degree of flexibility making compound 14 display mild pro-retention behavior (Fig. 1B and Table 2), but with no clear increase in PARP1 affinity for DNA damage (Fig. 1C and Table 2) therefore agreeing with a Type II behavior. Taken together, these results confirm compounds 13 and 14 as being modulators of PARP1 allostery, albeit to different extents.

Crystal structures of ART domain with the selected PARPi (Fig. 2) suggest that clashes with the N-terminus of αF helix could underlie the Type I inhibitor behavior of PARPi. Although compounds 10 and UKTT15 (6) both exhibit Type I behavior, they appear to influence PARP1 allostery in different ways. While both compounds stabilize portions of the Zn3 and WGR domains, UKTT15 (6) does not stabilize the central portion of the HD [27], which hints at compound 10 contacting the HD domain differently. This observation is consistent with the crystal structure of compound 10 bound to ΔVE, in which the compound substituent is buried at the interface of αD and αF (Fig. 3E, F). Overall, it appears that PARP1 allostery and retention on DNA damage can be triggered by the insertion of a compound in between the HD and the ART domain, whether this compound directly contacts the HD hydrophobic core or instead perturbs the interface of the two subdomains (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Type I inhibitors modulate PARP1 allostery via different binding poses.

The different trajectories of Type I PARPi are indicated by colored and labeled shapes overlaid on the structure of the PARP1 apo CAT domain (beige, PDB 7AAA).

Conclusions

The premise of this study was to introduce extended substituents on the benzimidazole-4-carboxamide scaffold of veliparib to trigger PARP1 allostery, that is communication from the active site to the DNA binding domains. We found that only a small subset of the derivatives we generated were able to promote PARP1 retention on damaged DNA: UKTT15 (6), 10, and 8. Crystal structures revealed that UKTT15 (6) interacts with a groove formed by HD helices αF and αD, and the ASL of the ART domain, whereas compound 10 was also found to engage the HD domain but in an adjacent region. These unique binding modes appear to be very effective at triggering PARP1 allostery given that UKTT15 (6) behavior is similar to EB-47, another type I PARPi that specifically targets the adenosine binding site. Though compound 10 contacts an adjacent region of the HD, our HXMS analysis confirmed that it can also induce allostery, albeit being slightly less effective in retaining PARP1 on a DNA break. We conclude that PARP1 DNA retention can be achieved by insertion of a compound in between the HD and the ART domain (Fig. 5), thus representing an inhibitor mechanism that can be exploited in the development of PARPi with allosteric signalling properties. The added bulkiness to the veliparib scaffold was necessary to invoke Type I behavior; however, it appears that the substituents needed to be productively engaged in stable interactions to effectively transmit an allosteric signal that could impart increased retention of a DNA break. Our study highlights the biochemical and biophysical analysis that allow PARP1 allostery to be evaluated in response to PARP inhibitors.

Methods

Chemistry.

Reagents, Solvents, and Instrumentation.

Chemicals used for the synthesis of intermediates and target compounds were purchased from several commercial sources such as Enamine LLC (Monmouth Jct., NJ), Ark Pharm (Arlington Heights, IL), Combi-Blocks (San Diego, CA), Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA), Accela Chembio (San Diego, CA), Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, WI), Chem-Impex Int. Inc. (Wood Dale, IL), Oakwood Products (West Columbia, SC), Oxchem Corporation (Wood Dale, IL), and Synthonix (Wake Forest, NC) and were used as received without further purification. Reactions were monitored using thin layer chromatographic (TLC) analysis with silica gel on aluminum backed plates (250-micron particle size, purchased from Agela Technologies) by visually inspecting changes in the Rf values using UV light at 254 nm. Intermediates and target compounds were subjected to 1H NMR experiments using Bruker 400 UltrashieldTM spectrometer (1H at 400 MHz) equipped with a z-axis gradient probe. 1H NMR chemical shifts were reported with reference to tetramethylsilane peak (TMS as an internal standard) in parts per million (δ ppm). The 1H NMR data were represented as: chemical shift (multiplicity s (singlet), bs (broad singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), dd (doublet of doublets), dt (doublet of triplets), tt (triplet of triplets), h (hextate), m (multiplet), number of protons and coupling constant). Final compounds were purified using flash chromatography using Reveleris® X2 flash chromatography system (BUCHI Corporation, New Castle, DE). HRMS data was procured using Waters Xevo G2-XS QToF MS with an electro spray ionization (ESI) source, coupled to an H-Class UPLC (Waters). Samples were prepared by dissolving solids in methanol, sequentially infused into the MS using auto-sampler (by bypassing the column) and eluted with acetonitrile and water containing 0.1% formic acid in each mobile phase. Melting points (uncorrected) were determined using Stuart digital melting point apparatus SMP20 (Cole-Parmer, Staffordshire, UK).

General Procedure A [41].

To a solution of 2,3-diaminobenzamide in DMF, appropriate benzaldehyde (1.1 eq) was added, followed by the subsequent addition of ammonium acetate (1.5 eq). The mixture was then heated at 100°C for 6 h after which the solvent was evaporated under vacuum. Later, the solid obtained was washed with methanol and water to obtain the desired product.

General Procedure B.

A mixture of carboxylic acid, HBTU (1.1 eq), EtN(i-Pr)2 (2 eq), appropriate amine (1.1 eq) and DMF were added to a flask and stirred overnight. Subsequently, DMF was removed via addition of ethyl acetate into the reaction mixture and extraction of the mixture 3X with saturated NaHCO3 and 3X with brine solution. The resultant organic layer was dried using MgSO4. A slurry of filtrate with silica was prepared and concentrated. It is not necessary to remove excess base by acidic extraction of the reaction mixture because the base assisted in purification of crude product (applicable only when the crude product is purified by flash chromatography). The mixture was then subjected to flash chromatographic purification using DCM:MeOH (usually in the ratio of 90:10; run time varied depending on column size) as mobile phase, with gradient elution to obtain products in 23–63% yields.

4-(4-Carbamoyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)benzoic acid (2).

The reaction was performed according to general procedure A using 2,3-diaminobenzamide 1 (1.0 g, 6.62 mmol), 4-formyl benzoic acid (1.10 g, 7.28 mmol) and ammonium acetate (0.77 g, 9.92 mmol) as starting materials to obtain 2 as a light to dark yellow powder (1.6 g, 86% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.65 (s, 1H), 13.25 (bs, 1H), 9.32 (s, 1H), 8.37 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 8.15 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.94–7.74 (m, 3H), 7.40 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H); ESI-MS (low resolution) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C15H12N3O3, 282.1, found: 282.1.

3-(4-Carbamoyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)benzoic acid (3).

The reaction was performed according to general procedure A using 2,3-diaminobenzamide 1 (0.50 g, 3.31 mmol), 3-formylbenzoic acid (0.55 g, 3.64 mmol) and ammonium acetate (0.38 g, 4.96 mmol) as starting materials to obtain 3 as an off-white solid (0.83 g, 89% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.66 (s, 1H), 13.35 (s, 1H), 9.34 (s, 1H), 8.82 (s, 1H), 8.51 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.11 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.95–7.81 (m, 2H), 7.81–7.71 (m, 2H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H); ESI-MS (low resolution) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C15H12N3O3, 282.1, found: 282.1.

2-(4-(4-(Pyrimidin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-4-carboxamide (4).

It was prepared according to general procedure B, by coupling 2 (100 mg, 0.36 mmol) with pyrimidin-2-yl-piperazine (64 mg, 0.39 mmol), as a pale yellow powder (96 mg, 63% yield), mp 282–285 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.56 (s, 1H), 9.35 (s, 1H), 8.40 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H), 8.34 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.93–7.74 (m, 3H), 7.68 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.69 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 3.96–3.65 (m, 6H), 3.56–3.40 (m, 2H); HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C23H22N7O2, requires 428.1829; found: 428.1856.

2-(3-(4-(Pyrimidin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-4-carboxamide (5).

It was prepared according to general procedure B, by coupling 3 (100 mg, 0.36 mmol) with pyrimidn-2-yl-piperazine (64 mg, 0.39 mmol), as a white powder (45 mg, 30% yield), mp 205–208 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.54 (s, 1H), 9.33 (s, 1H), 8.40 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 2H), 8.36 (dt, J = 7.7, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.31 (s, 1H), 7.90 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.81 (s, 1H), 7.76 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (dt, J = 7.6, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (t, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 3.98–3.67 (m, 6H), 3.58–3.43 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.09, 161.59, 158.49, 151.65, 137.19, 129.93, 129.83, 129.31, 128.46, 125.97, 123.56, 123.05, 111.03, 44.10, 43.61, 42.36, 42.11; HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C23H22N7O2, requires 428.1829; found: 428.1844.

Methyl 2-(4-(4-(4-carbamoyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)benzoyl)piperazin-1-yl)pyrimidine-5-carboxylate (6).

It was prepared according to general procedure B, by coupling 2 (100 mg, 0.36 mmol) with methyl 2-(piperazin-1-yl)pyrimidine-5-carboxylate (87 mg, 0.39 mmol), as a pale yellow powder (105 mg, 61% yield), mp 278–279 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.54 (s, 1H), 9.35 (s, 1H), 8.81 (s, 2H), 8.34 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.91 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (s, 1H), 7.77 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.05–3.84 (m, 4H), 3.84–3.71 (m, 5H), 3.59–3.43 (m, 2H). HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C25H24N7O4, requires 486.1884; found: 486.1904.

Sodium 2-(4-(4-(4-carbamoyl-1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)benzoyl)piperazin-1-yl)pyrimidine-5-carboxylate (7).

Compound 14 was prepared by treating 8 (100 mg, 0.21 mmol) with NaOH (17 mg, 0.42 mmol) and THF/H2O in 1:1 ratio. The reaction was then subjected to reverse phase flash purification by using 0–100% methanol in water as the mobile phase, in a gradient manner to obtain 14 as a pale-yellow powder which was re-dissolved in water and subjected to freeze drying process. (50 mg, 49% yield), mp >310 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.43 (s, 1H), 8.77 (s, 2H), 8.56–8.35 (m, 2H), 7.87 (ddd, J = 13.9, 7.8, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 7.81–7.71 (m, 1H), 7.71–7.58 (m, 2H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.02–3.36 (m, 8H); HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C24H22N7O4 (due to neutralization of salt by solvent), requires 472.1728; found: 472.1748.

2-(4-(4-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-4-carboxamide (8).

It was prepared according to general procedure B, by coupling 2 (100 mg, 0.36 mmol) with 2-(piperazin-1-yl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (79 mg, 0.39 mmol), as a pale-yellow powder (75 mg, 45% yield), mp 205–208 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.56 (s, 1H), 11.51 (s, 1H), 9.35 (s, 1H), 8.35 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.95–7.74 (m, 3H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.30–7.17 (m, 2H), 7.04–6.84 (m, 2H), 3.94–3.46 (m, 8H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.06, 166.55, 156.22, 151.60, 141.89, 137.95, 135.85, 130.58, 128.39, 127.46, 123.63, 123.13, 123.10, 115.65, 46.69, 46.56, 46.48, 46.41; HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C26H24N7O2, requires 466.1986; found: 466.2006.

2-(3-(4-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-4-carboxamide (9).

It was prepared according to general procedure B, by coupling 3 (100 mg, 0.36 mmol) with 2-(piperazin-1-yl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole (79 mg, 0.39 mmol), as a white powder (45 mg, 27% yield), mp 239–241 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.54 (s, 1H), 11.51 (s, 1H), 9.34 (s, 1H), 8.42–8.26 (m, 2H), 7.90 (dd, J = 7.6, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.86–7.61 (m, 4H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.32–7.13 (m, 2H), 7.08–6.80 (m, 2H), 3.97–3.46 (m, 8H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.08, 166.53, 156.21, 151.61, 141.83, 137.10, 135.81, 129.91, 129.35, 128.46, 125.93, 123.60, 123.09, 115.61, 46.64, 46.52, 46.32, 45.88; HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C26H24N7O2, requires 466.1986; found: 466.2004.

2-(4-((2-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)ethyl)carbamoyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-4-carboxamide (10).

It was prepared according to general procedure B, by coupling 2 (100 mg, 0.36 mmol) with 2-(1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)ethan-1-amine (63 mg, 0.39 mmol), as a pale yellow powder (40 mg, 26% yield), mp 288–290 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.55 (s, 1H), 12.34 (s, 1H), 9.33 (s, 1H), 8.88 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H), 8.33 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 8.05 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.94–7.74 (m, 3H), 7.62–7.34 (m, 3H), 7.13 (dd, J = 6.2, 2.9 Hz, 2H), 3.77 (q, J = 6.7 Hz, 2H), 3.13 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.53, 166.13, 153.29, 151.49, 141.88, 136.41, 135.84, 131.86, 128.47, 127.21, 123.67, 123.21, 123.11, 115.65, 38.61, 29.29; HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C24H21N6O2, requires 425.1721; found: 425.1732.

2-(3-((2-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)ethyl)carbamoyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-4-carboxamide (11).

It was prepared according to general procedure B, by coupling 3 (100 mg, 0.36 mmol) with 2-(1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)ethan-1-amine (63 mg, 0.39 mmol), as a white powder (35 mg, 23% yield), mp 226–228 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.63 (s, 1H), 12.35 (s, 1H), 9.37 (s, 1H), 8.95 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 8.73 (t, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.39 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.93–7.80 (m, 2H), 7.76 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.61–7.32 (m, 3H), 7.19–7.07 (m, 2H), 3.79 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 3.15 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H); HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C24H21N6O2, requires 425.1721; found: 425.1740.

2-(4-(3-(Trifluoromethyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazine-7-carbonyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-4-carboxamide (12).

It was prepared according to general procedure B, by coupling 2 (100 mg, 0.36 mmol) with 3-(trifluoromethyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazine (75 mg, 0.39 mmol), as a white powder (60 mg, 37% yield), mp >310°C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.58 (s, 1H), 9.34 (s, 1H), 8.37 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.95–7.70 (m, 5H), 7.39 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 4.42–3.76 (m, 4H); HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C21H17F3N7O2, requires 456.1390; found: 456.1395.

2-(3-(3-(Trifluoromethyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazine-7-carbonyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-4-carboxamide (13).

It was prepared according to general procedure B, by coupling 3 (100 mg, 0.36 mmol) with 3-(trifluoromethyl)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazine (75 mg, 0.39 mmol), as a white powder (55 mg, 34% yield), mp 233–235 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.47 (s, 1H), 9.29 (s, 1H), 8.46–8.33 (m, 2H), 7.90 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.81–7.63 (m, 4H), 7.37 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 5.04 (s, 2H), 4.42–3.80 (m, 4H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.80, 166.55, 151.55, 151.14, 143.20, 142.82, 141.82, 136.11, 135.82, 130.05, 129.89, 129.28, 128.92, 126.33, 123.61, 123.10, 120.28, 117.60, 115.64, 43.95, 43.85, 43.72; HRMS (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C21H17F3N7O2, requires 456.1390; found: 456.1418.

2-(3-((2-Amino-4,5-dimethylphenyl)carbamoyl)phenyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole-4-carboxamide (14).

Prepared according to general procedure B, by coupling 2 (100 mg, 0.36 mmol) with 4,5-dimethylbenzene-1,2-diamine (53 mg, 0.39 mmol), as a white powder (60 mg, 42% yield). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 13.60 (s, 1H), 9.84 (s, 1H), 9.38 (d, J = 3.5 Hz, 1H), 8.82 (s, 1H), 8.44 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.15 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.93 – 7.87 (m, 1H), 7.85 (s, 1H), 7.80 – 7.69 (m, 2H), 7.38 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.97 (s, 1H), 6.62 (s, 1H), 4.76 (s, 2H), 2.12 (d, J = 9.9 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.55, 165.81, 151.70, 144.23, 141.86, 135.86, 135.77, 130.20, 129.74, 129.68, 128.73, 128.38, 126.98, 123.60, 123.32, 123.09, 123.05, 116.43, 116.40, 115.65, 55.38. ESI-MS (low resolution) (m/z): [M + H]+ calcd for C23H22N5O2, requires 400.1; found: 400.1.

Biochemical and Biophysical Assay Protocols.

PARP1 enzyme inhibition assay.

The IC50 values for target compounds against PARP1 enzyme were calculated from a 10-point concentration-response curve using the BPS PARP1 Chemiluminescence Activity Assay Kit (Catalog #80551) (BPS Bioscience).

Expression constructs and mutagenesis.

The following PARP1 constructs were expressed from a pET28 expression vector (Novagen) with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag: PARP1 WT (residues 1–1014), ART domain (residues 661–1011 Δ678–787) and Zn1-Zn3 ΔZn2 domains (residues 1–366 Δ97–206). The WGR-CAT domain (518–1014) with the ΔVE mutation was expressed from a pET24 expression vector (Novagen) with a C-terminal hexahistidine tag. All mutations and deletions were performed using the QuickChange protocol (Stratagene) and verified by automated Sanger DNA sequencing.

Protein expression and purification.

PARP1 WT and mutant proteins were expressed and purified as described previously using three chromatography steps: Ni2+-affinity, heparin, and gel filtration [12, 42, 43].

Crystallization and data collection.

PARP1 ART domain was mixed with either compound 14, compound 13 or compound 10 in the following buffer: 25 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0,1 mM TCEP at the following concentrations: ART domain (30 mg/mL) and compound 14 (1.1 mM in DMSO, 10% final), ART domain (20 mg/mL) and compound 13 (0.73 mM in DMSO, 10% final), ART domain (10 mg/mL) and compound 10 (0.365 mM in DMSO, 7% final). All crystals were grown by sitting drop vapor diffusion at 20°C by mixing the PARP1 ART domain/compound complex with an equal amount of 20% PEG3000, 0.1 M sodium citrate pH 5.5 (pH adjusted with citric acid). Crystals were cryo-protected in 20% PEG3000, 0.1 M sodium citrate pH 5.5, 20% sucrose and 1.1 mM of target compound prior to flash cooling in liquid nitrogen.

The PARP1 ΔVE/DNA complex was formed by mixing Zn1-Zn3 ΔZn2 and WGR-CAT ΔVE at 300 μM each with a 5-bp DNA duplex at 165 μM (5’-CGACG-3’) in the following buffer: 25 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, and 0.1 mM TCEP. Crystals were grown by sitting drop vapor diffusion at 20°C by mixing the PARP1 ΔVE/DNA complex with an equal amount of 12% PEG 6000 and 100 mM MES pH 6.5. To obtain compound 10 bound to a PARP1 ΔVE/DNA complex, compound 10 (in DMSO, final concentration of 625 mM) was spiked into wells containing PARP1 ΔVE/DNA crystals (5% DMSO final). The compound heavily precipitated upon addition to the wells. Nevertheless, the crystals were kept in the presence of the compound for three days and then were rapidly transferred to a solution of 10% PEG 6000, 100 mM MES pH 6.5, 25% glycerol, 0.1 mM TCEP, 75 mM NaCl and 700 μM compound 10 (6% DMSO final) prior to flash cooling in liquid nitrogen.

X-ray diffraction data for all PARP1/compound complexes was collected at beamline 8.3.1 of the Advanced Light Source. The data was processed using XDS [44].

Structure determination of PARP1/compound complexes.

All PARP1/compound complex structures were determined by molecular replacement (MR) using the program PHASER as implemented in the CCP4 suite [45, 46]. The structure of PARP1 CAT domain bound to A968427 (PDB 3GJW) was used as search model for the ART domain after deleting the HD and ligand A968427 from the PDB file [47]. The structure of PARP1 apo ΔVE (PDB 7S6M) was used as search model for the PARP1 ΔVE/compound 10 complex [40]. All models were constructed using COOT and refined in REFMAC5 (CCP4 suite) and/or phenix.refine (Phenix suite) using TLS, geometric restraints, and NCS (when applicable) [48–51]. All atoms of compounds 13 and 14 were modeled in their respective crystal structures, despite a lack of clear electron density for their substituent groups, in contrast to the compound core electron density that was well defined. As such, it should be noted that the substituents are very mobile, as corroborated by high crystallographic B-factors relative to the compound core, and that they are likely to adopt a variety of conformations.

Fluorescence polarization.

Both the DNA competition assay and the DNA binding assays were essentially performed as described previously [35] and are described in greater detail in this section. All fluorescence polarization experiments were performed at least three times. Figures associated with each experiment display representative curves.

For the DNA competition assay, 40 nM PARP1 WT was incubated with 20 nM of dumbbell DNA with a central nick carrying an internal fluorescent FAM group (5′-GCT GAG C/FAMT/T CTG GTG AAG CTC AGC TCG CGG CAG CTG GTG CTG CCG CGA-3′) for 30 min at room temperature in 12 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 60 mM KCl, 8 mM MgCl2, 4% glycerol, 5.7 mM BME, 0.075 mg/ml BSA, and 5% DMSO and with or without veliparib, EB-47, or target PARPi compounds (100 μM). A competitor unlabeled DNA of the same sequence was added at 2 μM and FP was measured over time on a VictorV plate reader (Perkin Elmer).

For the DNA binding assay, increasing concentrations of PARP1 WT were incubated for 30 min at RT with 5 nM of an 18-bp DNA duplex (5′-GGGTTGCGGCCGCTTGGG-3′) that carried a fluorescent FAM group on the 5′ terminus of the complementary strand in the following buffer: 12 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 4% glycerol, 5.7 mM BME, 0.075 mg/ml BSA, and 5% DMSO and with or without veliparib, EB-47 or target PARPi compounds (150 μM). FP was measured on a VictorV plate reader (Perkin Elmer) and a 1:1 binding model was fit to the data using Matlab (MathWorks).

SDS-PAGE PARP1 activity assay.

The SDS-PAGE PARP1 activity assay was performed essentially as described [52]. PARP1 WT (300 nM) was preincubated with 300 nM of an 18-bp DNA duplex with or without veliparib, EB-47 or target compounds (75 μM) for 10 min at RT in the presence of 5% DMSO. 4 mM NAD+ was added to the reaction and the mixture was incubated for 1 min or 5 min before quenching with the addition of SDS loading buffer containing 0.1 M EDTA. The reactions were resolved on SDS-PAGE and stained with Imperial Protein Stain (Pierce).

Hydrogen/deuterium exchange-mass spectrometry (HXMS).

5 μM of single-strand break DNA (5′ GCT GGC TTC GTA AGA AGC CAG CTC GCG GTC AGC TTG CTG ACC GCG) was added to 2.6 μM of PARP1. PARP1 and DNA were incubated for 30 min. To make the PARP1/DNA/PARPi complex, 5.2 μM of respective PARPi was added to PARP1/DNA complex and incubated for another 30 min. At room temperature, 15 μL of deuterium on-exchange buffer (10 mM HEPES, pD 7.0, 150 mM NaCl, in D2O, pD = pH + 0.4138) was added to the PARP1, the PARP1/DNA complex, and the PARP1/DNA/ PARPi complex. This yielded a final D2O concentration of 75%. At 100 s, 20 μL was aliquoted into 30 μL of ice-cold quench buffer (1.66 M guanidine hydrochloride, 10 % glycerol, and 0.8 % formic acid to make a final pH of 2.4–2.5) and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The non-deuterated (ND) samples of PARP1 were prepared in 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, 150 mM NaCl buffer and each 20 μL aliquot was quenched into 30 μL of quench buffer. To mimic the on-exchange experiment, the fully deuterated (FD) samples were prepared in 75 % deuterium in triplicate (n=3) and denatured under acidic conditions (0.5 % formic acid). For every amide proton along the entire polypeptide chain to undergo full exchange, the samples were incubated for 48 h. At 0 °C, 50 μL of samples were melted and rapidly injected into pepsin column and pumped with an initial flow rate of 50 μL min−1 for 2 min followed by 150 μL min−1 for another 2 min. Via coupling, pepsin (Sigma) was immobilized to POROS 20 AL support (Applied Biosystems) in a 64 μL column (2 mm × 2 cm, Upchurch). TARGA C8 5 μm Piccolo HPLC column (1.0 × 5.0 mm, Higgins Analytical) was used to trap the peptic peptides and later these peptides were analyzed through C18 HPLC column (0.3 × 75 mm, Agilent) with a 12– 100% buffer B gradient at 6 μL/ min (Buffer A: 0. 1% formic acid; Buffer B: 0. 1% formic acid, 99.9% acetonitrile). The effluent was electrosprayed into the Exactive Plus EMR- Orbitrap (Thermo Fisher Scientific). MS data acquisition over the mass range 200 −2000 m/z were acquired on the Exactive Plus EMR- Orbitrap (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 60,000 resolution. The effluent was electrosprayed with ion spray voltage of 3.5 kV and capillary temperature operated at 250 °C.

PARP1 peptide identification.

ND samples were injected into LTQ orbitrap XL, (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for tandem mass spectroscopy (MS/MS) to identify PARP1 peptides. At 200– 2000 m/z scan range at 15,000 resolution the ions were fragmented by CID with normalized collision energy 35. The SEQUEST from Bioworks was employed to identify the potential PARP1 peptides. A 4 ppm of peptide tolerance and 0.1 AMU of fragment tolerance was used against an extensive decoy sequence database (custom database) containing the sequence of PARP1, pepsin and other common contaminants identified in our prior HXMS studies. In our search non-specific digestion was employed to search the PARP1 peptic peptides. To generate an exclusion list from the first MS/MS of ND, a MATLAB based program called ExMS2 was used with Ppep score of 0.1. With this exclusion list, MS/MS on second ND second was employed to collect the MS2 scan of the less intense peptides that were not identified in the previous ND sample. To increase the number of unique peptides and sequence coverage of the protein, the above steps were repeated four times. All the output files generated through SEQUEST were pooled and a final list of PARP1 peptides containing sequence, RT, and charge were generated by EXMS2.

HXMS analysis and plotting.

Peptide information generated through ExMS2 was added into the peptide source tab of HDExaminer (Sierra Analytics). This identifies the deuterated peptides for every protein state (PARP1, PARP1/DNA, and PARP1/DNA/PARPi). For each peptide, we compared the extent of deuteration as measured in the FD sample to the theoretical maximal deuteration i.e., if no back exchange occurs (loss of deuterium after quench). FD revealed a back-exchange in our experiments of 27–30%. To further assess the quality of each peptide the mass spectra was manually checked. An in-house script written in MATLAB was used to obtain the difference plot for the deuteration levels between any two protein states. The subtracted percent deuteration between two protein states is plotted as per the color legend (seen at Fig. 4A–C) in stepwise increments. Data analysis statistics for all the protein states are included in Table 4 and HXMS supplemental data file per HXMS community suggestions [53].

Table 4.

HXMS data summary.

| Data set | PARP1 |

|---|---|

| HX reaction details | 10 mM HEPES, 150 mL NaCl in D2O, pD 7.0 (pD = pH + 0.4138) at 25 °C |

| HX time course | 100 s |

| HX control samples | 3 Non-deuterated (ND) and 3 Fully deuterated (FD) |

| Back-exchange | 30% |

| Number of peptides | 208 |

| Sequence coverage | 94% |

| Average peptide length/ Redundancy | 15.8/3.2 (calculated as the total number of peptides for which HX were obtained over the total number of amides) |

| Replicates | 3 |

| Repeatability | 0.14 (average standard deviation from replicate measurements of the deuterium content of all peptides from 100 s) |

| Significant differences in HX | unpaired student t-test of a difference between compared conditions using p-value <0.05 |

| Data set | PARP1+DNA |

| HX reaction details | 10 mM HEPES, 150 mL NaCl in D2O, pD 7.0 (pD = pH + 0.4138) at 25 °C |

| HX time course | 100 s |

| HX control samples | 3 Non-deuterated (ND) and 3 Fully deuterated (FD) |

| Back-exchange | 30% |

| Number of peptides | 211 |

| Sequence coverage | 94% |

| Average peptide length/ Redundancy | 15.8/3.2 (calculated as the total number of peptides for which HX were obtained over the total number of amides) |

| Replicates | 3 |

| Repeatability | 0.12 (average standard deviation from replicate measurements of the deuterium content of all peptides from 100 s) |

| Significant differences in HX | unpaired student t-test of a difference between compared conditions using p-value <0.05 |

| Data set | PARP1+DNA+Compund10 |

| HX reaction details | 10 mM HEPES, 150 mL NaCl in D2O, pD 7.0 (pD = pH + 0.4138) at 25 °C |

| HX time course | 100 s |

| HX control samples | 3 Non-deuterated (ND) and 3 Fully deuterated (FD) |

| Back-exchange | 30% |

| Number of peptides | 212 |

| Sequence coverage | 94% |

| Average peptide length/ Redundancy | 15.8/3.2 (calculated as the total number of peptides for which HX were obtained over the total number of amides) |

| Replicates | 3 |

| Repeatability | 0.08 (average standard deviation from replicate measurements of the deuterium content of all peptides from 100 s) |

| Significant differences in HX | unpaired student t-test of a difference between compared conditions using p-value <0.05 |

| Data set | PARP1+DNA+Compound13 |

| HX reaction details | 10 mM HEPES, 150 mL NaCl in D2O, pD 7.0 (pD = pH + 0.4138) at 25 °C |

| HX time course | 100 s |

| HX control samples | 3 Non-deuterated (ND) and 3 Fully deuterated (FD) |

| Back-exchange | 30% |

| Number of peptides | 221 |

| Sequence coverage | 94% |

| Average peptide length/ Redundancy | 15.8/3.2 (calculated as the total number of peptides for which HX were obtained over the total number of amides) |

| Replicates | 3 |

| Repeatability | 0.07 (average standard deviation from replicate measurements of the deuterium content of all peptides from 100 s) |

| Significant differences in HX | unpaired student t-test of a difference between compared conditions using p-value <0.05 |

| Data set | PARP1+DNA+Compund14 |

| HX reaction details | 10 mM HEPES, 150 mL NaCl in D2O, pD 7.0 (pD = pH + 0.4138) at 25 °C |

| HX time course | 100 s |

| HX control samples | 3 Non-deuterated (ND) and 3 Fully deuterated (FD) |

| Back-exchange | 30% |

| Number of peptides | 201 |

| Sequence coverage | 94% |

| Average peptide length/ Redundancy | 15.8/3.2 (calculated as the total number of peptides for which HX were obtained over the total number of amides) |

| Replicates | 3 |

| Repeatability | 0.08 (average standard deviation from replicate measurements of the deuterium content of all peptides from 100 s) |

| Significant differences in HX | unpaired student t-test of a difference between compared conditions using p-value <0.05 |

Supplementary Material

Funding

This study is supported by NIH grant R01-CA259037 (to B.E.B., J.M.P. and T.T.T.). E.R.-T. is supported by a Fonds de recherche du Québec en santé (FRQS) training award. Macromolecular X-ray diffraction was collected at the Advanced Light Source (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory). Efforts to apply crystallography to characterize eukaryotic pathways relevant to human cancers are supported in part by National Cancer Institute grant Structural Biology of DNA Repair (SBDR) CA92584. Structural biology applications used in this project were compiled and configured by SBGrid [54]. R.B. was supported by an Early Career Award from Basser Center for BRCA.

Abbreviations

- ART

ADP-ribosyltransferase

- ASL

active site loop

- BAD

benzamide adenine dinucleotide

- BRCT

BRCA1 C-terminus

- CAT

catalytic domain

- DSB

double-strand break

- HD

helical domain

- HPF1

histone PARylation factor 1

- HXMS

hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry

- NAD+

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- PAR

poly(ADP-ribose)

- PARP

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

Footnotes

Competing interests

B.E.B., J.M.P., and T.T.T. are co-founders of Hysplex, Inc. with interests in PARP inhibitor development, B.E.B is on the scientific advisory board of Denovicon Therapeutics.

CRediT Author Contribution

Uday Kiran Velagapudi: Validation, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing –review and editing. Élise Rouleau-Turcotte: Validation, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing –review and editing. Ramya Billur: Validation, investigation, methodology, formal analysis, writing –review and editing. Xuwei Shao: Data curation, formal analysis, writing –review and editing. Manisha Patil: Data curation, formal analysis, writing –review and editing. Ben Black: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, formal analysis, project administration, writing – original draft, writing –review and editing. John Pascal: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, formal analysis, project administration, writing – original draft, writing –review and editing. Tanaji Talele: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, formal analysis, project administration, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Data Availability

Crystallography atomic coordinates and structure were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession codes 8FYY, 8FYZ, 8FZ1 and 8G0H. The HXMS data in this study have been deposited in the Pride database under accession code PXD047072. All other source data is included in the paper and any further information will be provided upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.De Vos M, Schreiber V and Dantzer F (2012) The diverse roles and clinical relevance of PARPs in DNA damage repair: current state of the art. Biochem Pharmacol. 84, 137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibson BA and Kraus WL (2012) New insights into the molecular and cellular functions of poly(ADP-ribose) and PARPs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 13, 411–424. doi: 10.1038/nrm3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray Chaudhuri A and Nussenzweig A (2017) The multifaceted roles of PARP1 in DNA repair and chromatin remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 18, 610–621. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alemasova EE and Lavrik OI (2019) Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by PARP1: reaction mechanism and regulatory proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 3811–3827. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonfiglio JJ, Fontana P, Zhang Q, Colby T, Gibbs-Seymour I, Atanassov I, Bartlett E, Zaja R, Ahel I and Matic I (2017) Serine ADP-Ribosylation Depends on HPF1. Mol Cell. 65, 932–940 e936. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniels CM, Ong SE and Leung AK (2015) The Promise of Proteomics for the Study of ADP-Ribosylation. Mol Cell. 58, 911–924. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamaletdinova T, Fanaei-Kahrani Z and Wang ZQ (2019) The Enigmatic Function of PARP1: From PARylation Activity to PAR Readers. Cells. 8 doi: 10.3390/cells8121625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dantzer F, de La Rubia G, Menissier-De Murcia J, Hostomsky Z, de Murcia G and Schreiber V (2000) Base excision repair is impaired in mammalian cells lacking Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1. Biochemistry. 39, 7559–7569. doi: 10.1021/bi0003442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noren Hooten N, Kompaniez K, Barnes J, Lohani A and Evans MK (2011) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) binds to 8-oxoguanine-DNA glycosylase (OGG1). J Biol Chem. 286, 44679–44690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.255869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawicki-McKenna JM, Langelier MF, DeNizio JE, Riccio AA, Cao CD, Karch KR, McCauley M, Steffen JD, Black BE and Pascal JM (2015) PARP-1 Activation Requires Local Unfolding of an Autoinhibitory Domain. Mol Cell. 60, 755–768. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eustermann S, Wu WF, Langelier MF, Yang JC, Easton LE, Riccio AA, Pascal JM and Neuhaus D (2015) Structural Basis of Detection and Signaling of DNA Single-Strand Breaks by Human PARP-1. Mol Cell. 60, 742–754. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langelier MF, Planck JL, Roy S and Pascal JM (2012) Structural basis for DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation by human PARP-1. Science. 336, 728–732. doi: 10.1126/science.1216338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayyappan V, Wat R, Barber C, Vivelo CA, Gauch K, Visanpattanasin P, Cook G, Sazeides C and Leung AKL (2021) ADPriboDB 2.0: an updated database of ADP-ribosylated proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D261–d265. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudolph J, Muthurajan UM, Palacio M, Mahadevan J, Roberts G, Erbse AH, Dyer PN and Luger K (2021) The BRCT domain of PARP1 binds intact DNA and mediates intrastrand transfer. Mol Cell. 81, 4994–5006.e4995. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matulonis UA and Monk BJ (2017) PARP inhibitor and chemotherapy combination trials for the treatment of advanced malignancies: does a development pathway forward exist? Ann Oncol. 28, 443–447. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee HJ, Yoon C, Schmidt B, Park DJ, Zhang AY, Erkizan HV, Toretsky JA, Kirsch DG and Yoon SS (2013) Combining PARP-1 inhibition and radiation in Ewing sarcoma results in lethal DNA damage. Mol Cancer Ther. 12, 2591–2600. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Tuli R, Surmak AJ, Reyes J, Armour M, Hacker-Prietz A, Wong J, DeWeese TL and Herman JM (2014) Radiosensitization of Pancreatic Cancer Cells In Vitro and In Vivo through Poly (ADP-ribose) Polymerase Inhibition with ABT-888. Transl Oncol. 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.04.003 doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konstantinopoulos PA, Waggoner S, Vidal GA, Mita M, Moroney JW, Holloway R, Van Le L, Sachdev JC, Chapman-Davis E, Colon-Otero G, Penson RT, Matulonis UA, Kim YB, Moore KN, Swisher EM, Farkkila A, D’Andrea A, Stringer-Reasor E, Wang J, Buerstatte N, Arora S, Graham JR, Bobilev D, Dezube BJ and Munster P (2019) Single-Arm Phases 1 and 2 Trial of Niraparib in Combination With Pembrolizumab in Patients With Recurrent Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 5, 1141–1149. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lord CJ and Ashworth A (2017) PARP inhibitors: Synthetic lethality in the clinic. Science. 355, 1152–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curtin NJ and Szabo C (2020) Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibition: past, present and future. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 19, 711–736. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Amours D, Desnoyers S, D’Silva I and Poirier GG (1999) Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem J. 342 (Pt 2), 249–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prokhorova E, Zobel F, Smith R, Zentout S, Gibbs-Seymour I, Schutzenhofer K, Peters A, Groslambert J, Zorzini V, Agnew T, Brognard J, Nielsen ML, Ahel D, Huet S, Suskiewicz MJ and Ahel I (2021) Serine-linked PARP1 auto-modification controls PARP inhibitor response. Nat Commun. 12, 4055. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24361-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, Kyle S, Meuth M, Curtin NJ and Helleday T (2005) Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 434, 913–917. doi: 10.1038/nature03443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, Santarosa M, Dillon KJ, Hickson I, Knights C, Martin NM, Jackson SP, Smith GC and Ashworth A (2005) Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 434, 917–921. doi: 10.1038/nature03445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murai J, Huang SY, Das BB, Renaud A, Zhang Y, Doroshow JH, Ji J, Takeda S and Pommier Y (2012) Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by Clinical PARP Inhibitors. Cancer Res. 72, 5588–5599. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murai J, Huang SY, Renaud A, Zhang Y, Ji J, Takeda S, Morris J, Teicher B, Doroshow JH and Pommier Y (2014) Stereospecific PARP trapping by BMN 673 and comparison with olaparib and rucaparib. Mol Cancer Ther. 13, 433–443. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zandarashvili L, Langelier MF, Velagapudi UK, Hancock MA, Steffen JD, Billur R, Hannan ZM, Wicks AJ, Krastev DB, Pettitt SJ, Lord CJ, Talele TT, Pascal JM and Black BE (2020) Structural basis for allosteric PARP-1 retention on DNA breaks. Science. 368 doi: 10.1126/science.aax6367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Penning TD, Zhu GD, Gandhi VB, Gong J, Liu X, Shi Y, Klinghofer V, Johnson EF, Donawho CK, Frost DJ, Bontcheva-Diaz V, Bouska JJ, Osterling DJ, Olson AM, Marsh KC, Luo Y and Giranda VL (2009) Discovery of the Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor 2-[(R)-2-methylpyrrolidin-2-yl]-1H-benzimidazole-4-carboxamide (ABT-888) for the treatment of cancer. J Med Chem. 52, 514–523. doi: 10.1021/jm801171j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferraris DV (2010) Evolution of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) inhibitors. From concept to clinic. J Med Chem. 53, 4561–4584. doi: 10.1021/jm100012m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang YQ, Wang PY, Wang YT, Yang GF, Zhang A and Miao ZH (2016) An Update on Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1 (PARP-1) Inhibitors: Opportunities and Challenges in Cancer Therapy. J Med Chem. 59, 9575–9598. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]