Abstract

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) has shown preliminary success in the treatment of youth in forensic settings. However, the implementation of DBT varies considerably from facility to facility. A scoping review was conducted to detail DBT intervention protocols in juvenile correctional and detention facilities. We described eight works' treatment setting, study design, youth characteristics, staff training, DBT approach, DBT skills modules, and main findings. All works involved DBT skills sessions, but few incorporated other DBT components such as individual therapy or skills coaching. Outcomes included reducing problematic behaviors such as aggression, improving mental health, and largely positive feedback regarding the DBT intervention from youth and staff. Our results consolidate the existing literature regarding DBT intervention in forensic settings for youth and inform future implementation and research of DBT in such facilities.

Keywords: dialectical behavior therapy, juvenile justice facility, justice-involved youth, descriptive review, systematic review

Introduction

Youth impacted by the juvenile legal system, particularly those incarcerated in correctional facilities, have complex mental health treatment needs. Detained youth have a lifetime prevalence of up to 95% for mental health disorders and 96% for substance use disorders (Borschmann et al., 2020). However, only approximately 30% of detained youth receive treatment (Underwood & Washington, 2016).

Social determinants of health, such as structural inequity, family poverty, community violence, educational inequity, and trauma, exacerbate factors that contribute to youth incarceration and recidivism (Anoshiravani, 2020; Hughes et al., 2020). Secure facilities offer highly structured settings to provide mental health treatment, particularly comprehensive programs such as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT).

Dialectical Behavior Therapy

DBT was initially developed to treat borderline personality disorder by empowering clients to engage with inner conflict, problem-solve, and enact change toward more appropriate behaviors (Linehan, 1993, 2015). Since its development, DBT has been used to manage various clinical expressions of emotional dysregulation and has been applied in juvenile forensic settings (Kenny et al., 2020; Linehan, 2015; Nelson-Gray et al., 2006).

The standard comprehensive DBT program consists of weekly group skills training, weekly individual therapy, DBT phone coaching, and weekly therapist consultation team meetings for 1 year (Linehan, 1993). The four core DBT skills modules, practiced in groups, are mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness. Individual therapy helps clients apply the learned skills within the context of their overall clinical needs. Clients use phone coaching for real-time skills coaching during challenging situations. Therapy consultation team meetings support therapists emotionally and educationally throughout the program. Program homework, such as diary cards, helps clients identify emotions and practice DBT skills in daily life.

The standard DBT program is comprehensive and requires effective therapists, positive environmental milieus, and strong patient–therapist relationships. Formal DBT training and supervision for therapists and staff are critical for proper DBT implementation (Linehan & Wilks, 2015).

An adaptation for DBT in correctional settings (DBT–Corrections Modified) has been described and utilized with benefit to emotion and behavior regulation and recidivism for incarcerated youth (Nyamathi et al., 2018; Shelton et al., 2011; Trestman et al., 2004). DBT–Corrections Modified adaptations include modifying the manual vocabulary and examples to be more appropriate to the client's education level and experiences. The total duration of the program is also flexible to accommodate a facility's duration of incarceration.

Tomlinson (2018) detailed DBT modifications in forensic settings worldwide using the risk-need-responsivity (RNR) model for reducing recidivism risk. The RNR model outlined the importance of increased DBT intensity for high-risk populations (e.g., people charged with violent offenses), altered programs to target “criminogenic needs” (e.g., antisocial attitudes), and tailored for individuals' strengths (e.g., motivation). Tomlinson found that alterations of DBT in forensic settings are common due to each facility's unique population needs and organizational policies. They advised facilities to adhere to the RNR model, which is consistent with best practices in rehabilitation.

DBT has also been adapted for adolescents (DBT-A; Rathus & Miller, 2014) to include as needed family therapy, multifamily skills training group, and middle path skills (e.g., finding balance between two seemingly opposites) that coincide with the mental health treatment needs of incarcerated youth.

Incarcerated youth are in a developmentally critical period and require special program modifications to improve mental health outcomes and mitigate further legal system involvement. During adolescence, there are rapid changes in brain areas associated with executive functions such as response inhibition, risk-taking behavior, and emotion regulation (Steinberg, 2005). Although adolescents are more likely to engage in risky and delinquent behaviors, they are likely to grow out of delinquent behavior as they transition into adulthood (Boyer, 2006; Fagan & Western, 2005; Steinberg et al., 2015). Thus, timely rehabilitation of children in juvenile forensic facilities is paramount.

Current Study

Implementation of DBT in juvenile forensic settings may be challenging due to underresourced facilities, lack of staff, or uncertainty about how best to implement the program (Fox & Whitt, 2008; Restum, 2005). Nonetheless, juvenile correctional and detention facilities have adapted DBT for their settings with varying success. Understanding the implementation science—the “study of methods to promote adoption and integration of evidence-based practices, interventions, and policies into routine health care and public health settings to improve the impact on population health”—of these adaptations is critical (National Cancer Institute, 2022).

This systematic narrative review of DBT programs in juvenile forensic settings aims to understand implementation challenges and successes, and highlight its utility in improving mental health and legal outcomes to inform future work in this area.

Method

The PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was used to design and implement a systematic search for publications evaluating DBT in juvenile forensic settings (Tricco et al., 2018). The preliminary protocol was preregistered on the Open Science Framework repository (https://osf.io/mrqb3/). A research librarian searched query terms (Appendix A1) in five databases (PsycINFO, PubMed, SCOPUS, CINAHL, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Publications). Both peer-reviewed and nonpeer-reviewed publications (gray literature) were eligible for inclusion.

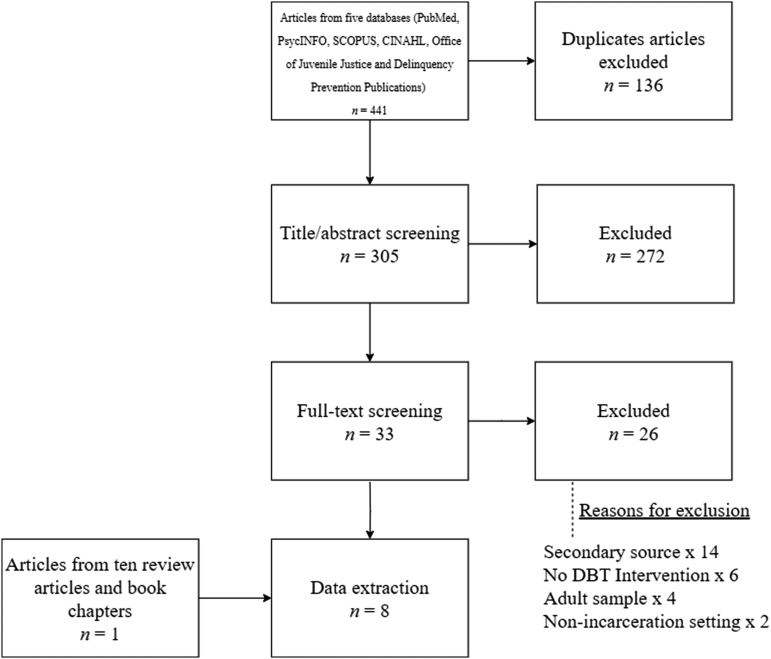

The study screening process was documented in a PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1). Our literature search yielded 441 articles, of which 136 were removed as duplicates. Three authors (P.Y., S.I.L., Z.B.) screened titles and abstracts of the remaining 305 articles. To ensure reliability, the authors first collectively screened 10 articles. The remaining articles were randomly assigned to the three authors for independent screening to determine whether they met inclusion criteria for full-text review. Inclusion criteria included (a) sample of youth in a secure forensic facility; (b) evaluation of DBT; and (c) examination of mental, behavioral, or physical health outcomes. Articles in languages other than English were excluded (n = 3).

Fig. 1.

Scoping review search strategy.

When independent screeners were uncertain, articles were collaboratively screened by at least two of the three screeners. Of the 302 articles, 269 did not meet inclusion criteria. Thirty-three articles (11%) were identified for full-text review by the same three authors. To ensure reliability, all coders collectively reviewed three articles. The remaining articles were randomly assigned to two coders each for review. Full texts were reviewed independently by two coders and discrepancies were resolved collaboratively.

Twenty-six articles did not meet inclusion criteria (secondary source n = 14; DBT not evaluated n = 6; sample did not contain youth n = 4; setting not a secure facility n = 2). Seven (21%) articles met inclusion criteria. Bibliographies of 10 secondary sources (systematic reviews, book chapters) identified during the search process were reviewed, yielding one additional article for inclusion. The overall total for the final analysis was eight articles.

Results

Study Characteristics

All eight studies were conducted in the United States and published between 2002 and 2020 (Table 1). Six studies involved long-term juvenile correctional facilities for adjudicated delinquent youth and two involved short-term juvenile detention facilities for preadjudicated youth. Study designs were 13% cross-sectional and 87% longitudinal. Sample sizes ranged from 4 to 1,031; 75% of studies had a sample size of less than 50.

Table 1.

Selected Article Characteristics

| Authors (year) | Treatment setting | Study design | Youth characteristics | Racial/ethnic composition | DBT staff training | DBT intervention approach | DBT skills modules | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banks et al. (2015) | State of Tennessee juvenile correctional facility | Pre–post and cross-sectional qualitative assessment | Sample size N = 9 % Male 0% Mean age years (range) 16 (14–18) |

19% Black, 11% Hispanic, 70% White | During the intervention, staff received weekly supervised group preparation. | Participants received weekly 90-minute skills group for 12 weeks. Participants recorded a daily diary card on feelings, behaviors, and skills use. Participants received individual and/or family therapy from DBT skills-training group leaders or clinicians not involved with skills training groups. | Mindfulness, Emotion Regulation, Interpersonal Effectiveness, and Distress Tolerance | Youth mental health There was a significant improvement in Ohio Youth Scales Problems, Satisfaction, and Depression subscales, but not the hope or functioning subscales. Youth behaviors Within the Problems subscales, there was significant improvement internalizing behaviors but not externalizing behaviors. Staff DBT feedback Treatment providers described successful implementation of DBT skills groups. |

| Fasulo et al. (2015) | Long-term juvenile detention facility in a southeastern city | Cohort qualitative assessment | Sample size N = 4 % Male 100% Range age years 15–17 |

50% Black, 25% Hispanic, 25% White | Clinicians are clinical psychology graduate students. They received weekly supervision by a licensed psychologist and an academic faculty member. | Participants received twice weekly, 1-hour sessions over 12 weeks. | Managing the Moment, Building Coping Strategies, and Enhancing Resiliency | DBT skills use Session summaries and participant quotes showed acceptance and growth toward each of the three skills. |

| Fox et al. (2020) | Washington State juvenile rehabilitation residential facilities | Cross-sectional | Sample size N = 1,031 % Male 88.9% Mean age years (range) 17.1 (11–21) |

56% White, 54% youth of color (not specified) | Prior to intervention, staff attend a 2-day training on DBT. During the intervention, staff attended biweekly team consultation meetings. | Participants received weekly individual sessions and weekly skills group. | Mindfulness, Interpersonal Effectiveness, Emotion Regulation, Distress Tolerance, and Middle Path | Youth behaviors Increased environmental adherence led to a significant reduction in the odds of any recidivism and in the odds of felony recidivism, but not misdemeanor recidivism within 18 months of release. The rate of counseling sessions and skills groups was unrelated to recidivism within 18 months of release. |

| Shelton et al. (2011) | Connecticut state correctional facility | Pre–post | Sample size N = 26 % Male 100% Mean age years (range) 17.9 (16–19) |

39% Black, 35% Hispanic, 4% Other, 23% White | Did not mention in article. | Participants received 16-week DBT-CM intervention, frequency unknown. | Mindfulness, Interpersonal Effectiveness, Distress Tolerance, and Emotion Regulation | Youth behaviors Participants had a statistically significant reduction in one of the two physical aggression measures (Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire) and using distancing as a coping strategy (Ways of Coping Checklist). There was a significant decrease in disciplinary tickets. Youth mental health There was no difference in negative or positive affect measures (Positive and Negative Affect Schedule). |

| Shelton et al. (2009) | Connecticut state correctional facility | Pre–post | Sample size DBT group: n = 22 No DBT/case management group: n = 16 % Male DBT group: 100% No DBT/case management group: 100% Mean age years DBT group: 17.9 No DBT/case management group: 18.2 |

DBT group: 40% Black, 27% Hispanic, 27% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 5% White No DBT/case management group: 6% Asian, 25% Black, 38% Hispanic, 13% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, 19% White |

Unspecified staff training. | Participants received 16-week DBT-CM intervention with twice weekly skills groups followed by random assignment to weekly 30-minute individual DBT coaching or weekly 30-minute individual case management for 8 weeks | Unspecified DBT skills | Youth behaviors After the 16-week skills group, there was a significant decrease in physical aggression (Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire), which was sustained on follow-up (unspecified if 6-months or 12-months). During the intervention, there was no significant difference in the number of disciplinary tickets. Youth mental health At the 6-month follow-up, there was a significant decrease in severity of psychopathology (Brief Psychiatric Rating). |

| Trupin et al. (2002) | Washington State Juvenile Rehabilitation Administration residential treatment cottages | Pre–post | Sample size DBT in mental health unit: n = 22 DBT in general population unit: n = 23 No DBT/standard treatment general population unit: n = 45 % Male DBT in mental health unit: 0% DBT in general population unit: 0% No DBT/standard treatment general population unit: 0% Mean age years DBT in mental health unit: 14.8 DBT in general population unit: 15.5 No DBT/standard treatment general population unit: n = 15.2 |

DBT in mental health unit: 15% American Indian, 15% Black, 10% Hispanic, 50% White DBT in general population unit: 9% American Indian, 22% Black, 14% Hispanic, 50% White No DBT/standard treatment general population unit: 9% American Indian, 23% Black, 7% Hispanic, 59% White |

Prior to intervention, staff from the mental health unit received 80 hours of DBT training. Staff from the general population unit received 16 hours of DBT training. Staff received weekly 1–2 hours of on-site instruction and case consultation throughout the intervention. | Participants received once or twice per week 60–90-minute group skills training for 4 weeks per skill for 10 months. Participants completed a daily diary card on skills use. | Core Mindfulness, Interpersonal Effectiveness, Distress Tolerance, Emotion Regulation, and Self-Management | Youth behaviors After the intervention, youth in the mental health unit had a reduction in behavior problems. Ninety days after intake, community risk assessment scores decreased across all groups but no significant decrease in the DBT groups. During the intervention, youth in the mental health unit were more likely to access rehabilitative services in the institution. Staff outcomes Compared with the previous non-DBT months, there was a reduction in mental health unit staff punitive actions during the 10 DBT months. During the intervention, there was a significant increase in general population staff punitive actions. |

| Wakeman (2010) | 92-bed juvenile correctional facility | Pre–post | Sample size Study 1: n = 8 Study 2: n = 38 % Male Study 1: 0% Study 2: 0% Mean age years (range) Study 1: 16 (14–18) Study 2: 16 (13–18) |

Study 1: 88% Black, 13% White Study 2: 3% Biracial (Black and White), 58% Black, 40% White |

Prior to intervention, staff were trained by Behavioral Tech, LLC, in a three-tiered system. Tier 1 staff received 80 hours of instruction and weekly meetings for 9 months prior to treatment implementation. Tier 2 staff received 20 hours of online instruction and a 2-day workshop. Tier 3 staff received the same 2-day workshop as Tier 2. There were an additional 4 hour-and-a-half trainings for staff who did not patriciate in the Tier 3 training. Staff received weekly consultation team meetings. | Participants received twice weekly 75-minute skills training groups for 4 weeks for a total of 16 weeks. Participants with significant mental health concerns received individual psychotherapy. Participants had limited individual therapy and on-site skills coaching. Participants completed diary cards on skills use, thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. | Core Mindfulness, Distress Tolerance, Interpersonal Effectiveness, and Emotion Regulation | Youth mental health In the first study across three study time points, there were no significant differences in depression scores, anxiety scores, anger scores, or suicide risk. In the second study across three study time points, there were significant reductions in self-reported depression scores, self-reported anxiety scores, and suicide risk. However, there was not a significant difference in staff-reported depression scores, staff-reported anxiety scores, self-reported anger scores, and staff-reported anger scores. Youth behaviors In the second study, there was not a significant decrease in disciplinary charges between the first half and the second half of the intervention DBT skills use At the end of the second study, 36 of the 38 participants provided positive qualitative feedback about the Core Mindfulness skills group. Youth DBT feedback Throughout the intervention, participant skills group leaders and coleaders completed feedback surveys indicating dissatisfaction with the intervention as a form of treatment and did not believe it helped students, but did enjoy leading the groups. |

| Walden et al. (2019) | Short-term juvenile detention facility in a mid-sized midwestern city | Pre–post and cross-sectional qualitative assessment | Sample size N = 113 % Male 69% Mean age years (range) 15.4 (11–18) |

2% Asian, 58% Black, 20% Unknown, 20% White | Prior to intervention, staff received 6 hours of training followed by additional trainings 2, 6, and 12 months after the intervention began. | Participants received self-contained weekly 90-minute skills training groups for up to 12 weeks. Participants completed a daily diary on behavior, skills use, and emotions. | Mindfulness, Interpersonal Effectiveness, Emotion Regulation, and Distress Tolerance. Mindfulness was implemented in-between each skill model | DBT skills use From Week 1 to Week 3 and over time, there was a significant increase in reported use of Mindfulness, Distress Tolerance, Emotion Regulation, and Interpersonal Effectiveness. At Weeks 1, 2, and 3, use of Mindfulness skills was significantly higher than use of other-module skills. When asked about engagement with skills at the end of the intervention, participants were able to discuss their use of Mindfulness skills to help them consider the consequences of their actions. Youth DBT feedback When asked about treatment buy-in at the end of the intervention, participants reported that engaging in therapy implied weakness and was not practical. |

CM, corrections modified; DBT, dialectical behavior therapy.

Two studies compared DBT with the facility's standard treatment; the other six studies did not include a comparison condition. Participating youth ranged from 11 to 21 years old. Three studies included only females, three only males, and two included both sexes. Consistent with the disproportionate representation of racial and ethnic minoritized youth in the juvenile legal system, Black and Hispanic participants were overrepresented in study samples compared with the general population (Harris et al., 2009). A summary of key DBT components and assessed outcomes can also be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of Articles: Key Dialectical Behavior Therapy Components and Assessed Outcomes

| Banks et al. (2015) | Fasulo et al. (2015) | Fox et al. (2020) | Shelton et al. (2009) | Shelton et al. (2011) | Trupin et al. (2002) | Wakeman (2010) | Walden et al. (2019) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of facility | Correctional | Detention | Residential | Correctional | Correctional | Residential | Correctional | Detention |

| Length of program | 12 weeks | 12 weeks | Throughout duration of commitment | 16 weeks group followed by 8 weeks individual | 16 weeks | 10 months | 16 weeks | 12 weeks |

| Group DBT skills | Core skills | Managing the Moment, Building Coping Strategies, and Enhancing Resiliency | Core skills+DBT-A middle path | Skills included but content not specified | Core skills | Core skills+self-management | Core skills | Core skills+mindfulness skills between subsequent modules |

| Individual DBT therapy | Yes | Yes | Yes (DBT or case management) | Limited to those with the highest risk for mental health concerns | ||||

| Team consultation/training | Yes | Yes | Yes | Training provided but content not specified | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Diary card | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Real-time coaching | Yes | |||||||

| Mental health outcome | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Behavior outcome | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Skills use | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Staff-related outcomes | Yes | |||||||

| Implementation outcomes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Core skills include mindfulness, emotional regulation, interpersonal effectiveness, and distress tolerance. Blank cells represent that the article did not include or mention the component or outcome.

DBT-A, DBT for adolescence.

DBT Program Characteristics

All studies incorporated DBT models modified in timing and/or components. All studies incorporated DBT skills groups ranging from 30 to 90 minutes weekly to biweekly for 12 to 40 weeks. Fox et al. (2020) did not specify the length of intervention. Walden et al. (2019) implemented self-contained skills training due to the average youth detention period of 3 weeks.

Six of the seven studies that listed skills modules included at least the four core modules: mindfulness, emotional regulation, interpersonal effectiveness, and distress tolerance. Only Fox et al. (2020) implemented the DBT-A “middle path” skill. Trupin et al. (2002) implemented the “self-management” skill. Fasulo et al. (2015) self-defined three skills: managing the moment, building coping strategies, and enhancing resiliency. Shelton et al. (2009) did not specify which skills modules were used. In Walden et al. (2019), mindfulness modules were delivered in between every module.

Four studies (50%) incorporated individual therapy (Banks et al., 2015; Fox et al., 2020; Shelton et al., 2009; Wakeman, 2010). Fox et al. (2020) involved weekly individual DBT therapy. Individual therapy in Banks et al. (2015) was part of the facility's standard treatment and did not necessarily involve a DBT therapist. In Shelton et al. (2009), individual therapy took place after the group skills, as opposed to concurrently as described in the DBT manual (Linehan, 1993). In Wakeman (2010), only a subset of youth, referred by staff, received individual therapy.

Seven studies (88%) described staff training or team consultation meetings; only Shelton et al. (2011) did not. Fox et al. (2020), Trupin et al. (2002), and Wakeman (2010) incorporated both preintervention training and weekly or biweekly consultation meetings. Walden et al. (2019) incorporated preintervention training and three additional trainings 2, 6, and 12 months after the intervention began. Banks et al. (2015) described weekly consultation meetings, but not preintervention training. In Fasulo et al. (2015), the clinicians were clinical psychology students and received weekly supervision by a licensed clinical psychologist and an academic faculty member. Shelton et al. (2009) indicated staff were trained but did not specify how.

Only Wakeman (2010) discussed phone coaching, which was replaced by on-site skills coaching. Four studies (50%) described the use of diary cards where participants recorded their daily DBT skills use and behaviors, emotions, or thoughts (Banks et al., 2015; Trupin et al., 2002; Wakeman, 2010; Walden et al., 2019).

Youth Outcomes

Four studies assessed mental health-related outcomes (Banks et al., 2015; Shelton et al., 2009, 2011; Wakeman, 2010). Wakeman (2010) described two evaluations of a 16-week DBT skills intervention (Ns = 8 and 38). Significant reductions in self-reported depression, anxiety, and suicide risk scores, but not in staff-reported scores or self-reported anger scores, were observed from pre- to postintervention only in the second study (N = 38).

Shelton et al. (2009) found a significant decrease in the severity of psychopathy (Brief Psychiatric Rating scale; Overall & Gorham, 1962) in the intervention group (n = 22) compared with the standard-of-care control group (n = 16) from preintervention to the 6-month follow-up; no changes in psychopathy were observed from preintervention to immediately after the 16-week skills group or at the 12-month follow-up.

Banks et al. (2015) found significant improvement in depression subscales (Beck Depression Inventory-II; Beck et al., 1996) after the 12-week intervention (N = 9). Shelton et al. (2011) did not find a difference between negative or positive affect measures (Positive and Negative Affect Scales; Watson et al., 1988).

Five studies assessed youth behavioral outcomes (Banks et al., 2015; Fox et al., 2020; Shelton et al., 2009, 2011; Trupin et al., 2002). Fox et al. (2020) showed that youth who were exposed to more supportive DBT milieu management, but not more individual therapy or skills group sessions, had reduced rates of recidivism within 18 months of release (N = 1,031). Trupin et al. (2002) found a reduction in composite behavior problems in the mental health unit (n = 22) but not in the general population unit (n = 23) during the 10-month intervention. They also found a reduction in community risk assessment scores in both groups 90 days after intake.

Shelton et al. (2011) found a reduction in disciplinary tickets after the intervention compared with a period before the intervention (N = 26). Shelton et al. (2009) also found a reduction in disciplinary tickets after the intervention compared with 12 months prior, but not 6 months after the intervention; the analysis sample included adolescents and adults, ages 16–59 years. Shelton et al. (2009, 2011) found reductions in physical aggression (Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire; Buss & Perry, 1992) from pre- to postintervention, which was sustained at follow-up (Shelton et al., 2009). Banks et al. (2015) found a significant improvement in internalizing but not externalizing behaviors (Ohio Youth Scales; Ogles et al., 2004) after the intervention.

Three studies assessed positive behaviors (Shelton et al., 2009, 2011; Trupin et al., 2002). In Trupin et al. (2002), youth in the mental health unit were more likely to access rehabilitative services, such as completing a general equivalency degree or drug and alcohol program, during the DBT intervention compared with the year prior. Shelton et al. (2011) found that participants were more likely to use distancing as a coping strategy (Ways of Coping Checklist; Folkman & Lazarus, 1988) immediately after the intervention, whereas Shelton et al. (2009) found that youth were more likely to use accepting responsibility (Ways of Coping Checklist) at follow-up.

Two studies assessed DBT skills use (Fasulo et al., 2015; Walden et al., 2019). Walden et al. (2019) found a significant increase in reported use of mindfulness, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, and emotion regulation skills between intervention week 1 and week 3 (N = 113). They also reported significantly greater use of mindfulness skills compared with the other DBT skills during the same period. In qualitative interviews after the 12-week intervention, youth described situations where they might use DBT skills but expressed difficulty implementing the skills outside of group sessions. Fasulo et al. (2015) qualitatively described four youths' progression through and use of skills during 24 group sessions.

Staff Outcomes

One study evaluated the number of staff punitive actions (e.g., room confinement) during the intervention period in the DBT mental health unit and the DBT general population unit (Trupin et al., 2002). A reduction in punitive action from mental health unit staff compared with previous nonintervention periods was observed. In the general population unit, they found an increase in staff punitive action during the intervention period.

Implementation Outcomes

Outcomes of implementation research are operationalized based on Proctor et al. (2011). Three studies evaluated implementation outcomes of the adapted DBT intervention (Banks et al., 2015; Wakeman, 2010; Walden et al., 2019). In Banks et al. (2015), DBT implementation was considered feasible based on qualitative interviews with staff group leaders on organization factors, program factors, change agents, and staff factors. Treatment providers described the helpfulness of the structured DBT skills training manual and supervision.

In Walden et al. (2019), implementation suggested challenges in acceptability and appropriateness. Youth qualitatively described challenges with treatment buy-in at the end of the intervention. Themes implied that engaging in therapy was associated with weakness and utilization of DBT skills during emotionally intense settings, such as physical fights, was not practical.

Wakeman (2010) also highlighted challenges in implementation acceptability and appropriateness. Most participants (95%) provided positive qualitative feedback about the mindfulness skills groups, describing it as fun and helpful, but also as lasting too long (75 minutes); youth also noted skills were difficult to remember. Youth skills group leaders (n = 6–10) completed Likert-scale feedback surveys throughout the treatment. Overall, leaders were dissatisfied with the intervention and did not believe it helped youth, but expressed that they enjoyed leading the groups.

Discussion

This systematic narrative review adds to the scientific literature regarding effective mental health programs for incarcerated youth and highlights the dearth of evidence available about the use of DBT in youth correctional facilities. Youth incarceration is a window of opportunity for delivering much-needed mental health treatment, and it is imperative that we optimize the use of the current punitive correctional youth system while reducing the harm this system inflicts on children, families, and communities.

Our review shows promising results about the effectiveness of DBT in reducing mental health concerns among incarcerated youth, reducing rates of recidivism, and improving staff caregiving skills. Of note, Trupin et al. (2002) demonstrated a decrease in the use of punitive actions by staff during DBT use, though some studies did not show a reduction in disciplinary actions after DBT. Shelton et al. (2009, 2011) focused on youth with impulsive behavior issues and demonstrated a decrease in aggressive behaviors. Few programs incorporated a comprehensive DBT program with all four core components (i.e., group skills, individual therapy, peer consultation, coaching); however, benefits existed even for programs that implemented group skills only.

Interestingly, DBT dosage did not vary considerably between detention facilities and correctional facilities. The two reviewed detention facilities implemented 12-week programs (Fasulo et al., 2015; Walden et al., 2019). Most correctional facilities implemented 16-week programs, with one program implementing a 12-week program and one program implementing a 10-month program. Unlike community settings, adapting DBT in forensic settings requires consideration of the clients' average length of incarceration. One detention facility made each session self-contained due to the short average length of detention (approximately 3 weeks) at their facility so that even youth who attended one session had the potential to benefit (Walden et al., 2019).

Adequate implementation of comprehensive DBT in correctional facilities, and not just as stand-alone individual or group skills services, offers an opportunity to address the interpersonal conflict that commonly occurs among youth and between youth and staff. Some of the studies included in our review highlight the importance of equipping correctional staff with effective strategies to support youth and minimize the use of restraints, encourage effective communication, and reduce the negative power dynamics that can arise in correctional facilities.

Shifting the focus from solely treating youths' mental health to also creating social change in the way that staff, clinicians, and other caregivers in these facilities interact with youth can produce additional benefits to the implementation of therapeutic interventions. For example, Baetz et al. (2021) found that implementation of trauma-informed practices in juvenile detention was helpful in reducing the harm of incarceration only when (a) a threshold number of youth were trained and (b) when both youth and staff were trained.

DBT can empower correctional staff with nonpunitive and effective caregiving skills that can improve communication, collaboration, and consistency among correctional and clinical staff, ultimately empowering youth with clinical and communication skills to improve their self-advocacy abilities.

The reviewed articles described challenges associated with implementing DBT in juvenile forensic settings as well as implementation strategies used to address challenges (Waltz et al., 2015). Commonly noted challenges included cost of DBT implementation, facility/staff resources, youth buy-in, and postadjudication processes (e.g., transfer, early release). Three of the reviewed articles were led by graduate students and/or student clinicians (Banks et al., 2015; Fasulo et al., 2015; Wakeman, 2010). Lack of funding for DBT in the facilities may have led well-meaning graduate students to incorporate innovative DBT programs in these settings. However, this may have led to the implementation of novice therapy to incarcerated youth, who are some of the most vulnerable members of society.

Other programs also noted challenges in youth buy-in, which may have contributed to disruptive behavior during group sessions (Wakeman, 2010; Walden et al., 2019). Using the “engage consumers” strategies, clinicians can integrate youth experiences, such as cultural identities and life experiences, to promote intervention buy-in (Kaput, 2018). Fasulo et al. (2015) qualitatively described the initial challenges in establishing rapport with the youth. The clinicians used the “adapt and tailor to context” strategy, for example by incorporating youth-requested music to facilitate mindfulness exercises. Clinicians also intentionally deemphasized change strategies due to the youths' history of resisting attempts from authority to change their behaviors and invalidate their experiences.

Few of the reviewed articles discussed quality metrics. Fox et al. (2020) described challenges in standardized quality control for individual counseling and skills groups due to limited staff resources. Trupin et al. (2002) described five times more DBT training to staff working in the mental health unit than in the general population unit, muddying the interpretation of results due to unequal staff training, but this may be an important reminder of the type of “adapt and tailor to the context” strategy needed in youth correctional settings.

In summary, our review's conclusions should be carefully examined as the existing evidence base is limited in that most studies had small sample sizes of youth in a single facility and used within-subjects designs without control or active comparison conditions. Fully powered samples and more rigorous designs (e.g., randomized control trials) are needed.

Future directions in research assessing the effectiveness of DBT in youth correctional facilities should incorporate additional layers of cultural and structural components that may be needed to increase the impact of this intervention. For example, ensuring that trauma is compassionately and effectively addressed is of utmost importance to reduce the behaviors that tend to result in aggression and recidivism (Kerig, 2019). Implementation of DBT must also take into consideration that youth in correctional settings may have never been exposed to mindfulness or overall mental health awareness frameworks, as most children have not. Effective use of these skills requires culturally relevant applications that are codeveloped with youth voices.

Incorporating family members in the assessment and treatment of incarcerated youth is also strongly recommended by national advocacy efforts and is a component of DBT-A, yet our review found only one publication describing family involvement in treatment (Development Services Group, 2018). Finally, future research and policy must consider the social and monetary cost of implementing therapeutic models in correctional settings as opposed to nourishing communities with services that keep youth in the community, enhance public safety, and are less expensive than traditional services for this population (Dopp et al., 2018).

Acknowledgment

We thank Christine S. Gaspard, MSLS, librarian liaison to the School of Medicine at UT Health San Antonio for her assistance developing and administering the search strategy.

Appendix A1

Database Search Query Terms

“dialectical behavioral therapy” OR “DBT” AND “juvenile detention” OR “juvenile justice” OR “juvenile corrections” OR “juvenile facility” OR “incarcerated youth” OR “juvenile offender” OR “youth detention”

Authors' Contributions

P.Y.: conceptualization (lead), data curation (equal), formal analysis (lead), investigation (equal), methodology (lead), project administration (lead), visualization (lead), writing—original draft (equal), and writing—review and editing (equal). J.B.F.: supervision (equal), validation (equal), visualization (supporting), writing—original draft (equal), and writing—review and editing (equal). S.I.L.: data curation (equal), formal analysis (supporting), investigation (equal), visualization (supporting), and writing—review and editing (equal). Z.B.: data curation (equal), investigation (equal), and writing—review and editing (equal). A.T.: supervision (equal) and writing—review and editing (supporting). B.R.-R.: supervision (equal), validation (equal), visualization (supporting), writing—original draft (equal), and writing—review and editing (equal).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Funding Information

J.B.F. received grant support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA050798).

References

- Anoshiravani, A. (2020). Addressing the unmet health needs of justice system-involved youth. The Lancet Public Health, 5(2), e83. 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30251-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baetz, C. L., Surko, M., Moaveni, M., McNair, F., Bart, A., Workman, S., Tedeschi, F., Havens, J., Guo, F., Quinlan, C., & Horwitz, S. M. (2021). Impact of a trauma-informed intervention for youth and staff on rates of violence in juvenile detention settings. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(17–18), NP9463–NP9482. 10.1177/0886260519857163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks, B., Kuhn, T., & Blackford, J. (2015). Modifying dialectical behavior therapy for incarcerated female youth: A pilot study. Journal of Juvenile Justice, 4(1), 1–14. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles/251064.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Ball, R., & Ranieri, W. (1996). Comparison of beck depression inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment, 67(3), 588–597. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borschmann, R., Janca, E., Carter, A., Willoughby, M., Hughes, N., Snow, K., Stockings, E., Hill, N. T. M., Hocking, J., Love, A., Patton, G. C., Sawyer, S. M., Fazel, S., Puljević, C., Robinson, J., & Kinner, S. A. (2020). The health of adolescents in detention: A global scoping review. The Lancet Public Health, 5(2), e114–e126. 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30217-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, T. W. (2006). The development of risk-taking: A multi-perspective review. Developmental Review, 26(3), 291–345. 10.1016/j.dr.2006.05.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 452–459. 10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Development Services Group, Inc. (2018). Family engagement in juvenile justice (Report No. 251737). Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/model-programs-guide/literature-reviews/family_engagement_in_juvenile_justice.pdf

- Dopp, A. R., Schaeffer, C. M., Swenson, C. C., & Powell, J. S. (2018). Economic impact of multisystemic therapy for child abuse and neglect. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 45(6), 876–887. 10.1007/s10488-018-0870-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan, A. A., & Western, J. (2005). Escalation and deceleration of offending behaviours from adolescence to early adulthood. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 38(1), 59–76. 10.1375/acri.38.1.59 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fasulo, S. J., Ball, J. M., Jurkovic, G. J., & Miller, A. L. (2015). Towards the development of an effective working alliance: The application of DBT validation and stylistic strategies in the adaptation of a manualized complex trauma group treatment program for adolescents in long-term detention. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 69(2), 219–239. 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2015.69.2.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(3), 466–475. https://doi.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.466 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, A. M., Miksicek, D., Veele, S., & Rogers, B. (2020). An evaluation of dialectical behavior therapy for juveniles in secure residential facilities. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 59(8), 478–502. 10.1080/10509674.2020.1808557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, K. C., & Whitt, A. L. (2008). Telemedicine can improve the health of youths in detention. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 14(6), 275–276. 10.1258/jtt.2008.008002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, C. T., Steffensmeier, D., Ulmer, J. T., & Painter-Davis, N. (2009). Are Blacks and Hispanics disproportionately incarcerated relative to their arrests? Racial and ethnic disproportionality between arrest and incarceration. Race and Social Problems, 1(4), 187–199. 10.1007/s12552-009-9019-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, N., Ungar, M., Fagan, A., Murray, J., Atilola, O., Nichols, K., Garcia, J., & Kinner, S. (2020). Health determinants of adolescent criminalisation. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(2), 151–162. 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30347-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaput, K. (2018). Evidence for student-centered learning. Education Evolving. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED581111

- Kenny, T. E., Carter, J. C., & Safer, D. L. (2020). Dialectical behavior therapy guided self-help for binge-eating disorder. Eating Disorders, 28(2), 202–211. 10.1080/10640266.2019.1678982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerig, P. K. (2019). Linking childhood trauma exposure to adolescent justice involvement: The concept of posttraumatic risk-seeking. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 26(3), e12280. 10.1111/cpsp.12280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M. M. (1993). Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder (pp. xii, 180). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M. M. (2015). DBT® skills training manual, 2nd ed (pp. xxiv, 504). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M. M., & Wilks, C. R. (2015). The course and evolution of dialectical behavior therapy. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 69(2), 97–110. 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2015.69.2.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. (2022, August 4). About Implementation Science. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/is/about

- Nelson-Gray, R. O., Keane, S. P., Hurst, R. M., Mitchell, J. T., Warburton, J. B., Chok, J. T., & Cobb, A. R. (2006). A modified DBT skills training program for oppositional defiant adolescents: Promising preliminary findings. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(12), 1811–1820. 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi, A., Shin, S. S., Smeltzer, J., Salem, B., Yadav, K., Krogh, D., & Ekstrand, M. (2018). Effectiveness of dialectical behavioral therapy on reduction of recidivism among recently incarcerated homeless women: A pilot study. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(15), 4796–4813. 10.1177/0306624X18785516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogles, B. M., Dowell, K., Hatfield, D., Melendez, G., & Carlston, D. L. (2004). The Ohio scales. In M. E. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment: Instruments for children and adolescents, volume 2 (3rd ed., pp. 275–304). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Overall, J. E., & Gorham, D. R. (1962). The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychological Reports, 10, 799–812. https://doi.org/10.2466%2Fpr0.1962.10.3.799 [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(2), 65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathus, J. H., & Miller, A. L. (2014). DBT® skills manual for adolescents (pp. xvi, 392). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Restum, Z. G. (2005). Public health implications of substandard correctional health care. American Journal of Public Health, 95(10), 1689–1691. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton, D., Kesten, K., Zhang, W., & Trestman, R. (2011). Impact of a dialectic behavior therapy–corrections modified (DBT-CM) upon behaviorally challenged incarcerated male adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 24(2), 105–113. 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2011.00275.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton, D., Sampl, S., Kesten, K. L., Zhang, W., & Trestman, R. L. (2009). Treatment of impulsive aggression in correctional settings. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 27(5), 787–800. 10.1002/bsl.889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L. (2005). Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 69–74. 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., & Monahan K. C. (2015). Psychosocial maturity and desistance from crime in a sample of serious juvenile offenders (report No: 029840). OJJDP Juvenile Justice Bulletin. https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh176/files/pubs/248391.pdf

- Tomlinson, M. F. (2018). A theoretical and empirical review of dialectical behavior therapy within forensic psychiatric and correctional settings worldwide. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 17(1), 72–95. 10.1080/14999013.2017.1416003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trestman, R. L., Gonillo, C., & Davis, K. (2004). Dialectical Behavior Therapy–Corrections Modified (DBT-CM) skills training manual [Unpublished treatment manual]. University of Connecticut Health Center. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O'Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trupin, E. W., Stewart, D. G., Beach, B., & Boesky, L. (2002). Effectiveness of a dialectical behaviour therapy program for incarcerated female juvenile offenders. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 7(3), 121–127. 10.1111/1475-3588.00022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, L. A., & Washington, A. (2016). Mental illness and juvenile offenders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(2), 228. 10.3390/ijerph13020228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman, E. E. (2010). Modified core mindfulness skills training in an adolescent female correctional sample [Doctoral thesis, University of Alabama Libraries]. https://ir.ua.edu/handle/123456789/961

- Walden, A. L., Stancil, N., & Verona, E. (2019). Reaching underserved youth: A pilot implementation of a skills-based intervention in short-term juvenile detention. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 47(2), 90–103. 10.1080/10852352.2019.1582147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz, T. J., Powell, B. J., Matthieu, M. M., Damschroder, L. J., Chinman, M. J., Smith, J. L., Proctor, E. K., & Kirchner, J. E. (2015). Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implementation Science, 10, 109. 10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]