Abstract

A protein homologous to the Escherichia coli MutY glycosylase, referred to as mtMYH, has been purified from calf liver mitochondria. SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, western blot analysis as well as gel filtration chromatography predicted the molecular mass of the purified calf mtMYH to be 35–40 kDa. Gel mobility shift analysis showed that the purified mtMYH formed specific binding complexes with A/8-oxoG, G/8-oxoG and T/8-oxoG, weakly with C/8-oxoG, but not with A/G and A/C mismatches. The purified mtMYH exhibited DNA glycosylase activity removing adenine mispaired with G, C or 8-oxoG and weakly removing guanine mispaired with 8-oxoG. The mtMYH glycosylase activity was insensitive to high concentrations of NaCl and EDTA. The purified mtMYH cross-reacted with antibodies against both intact MutY and a peptide of human MutY homolog (hMYH). DNA glycosylase activity of mtMYH was inhibited by anti-MutY antibodies but not by anti-hMYH peptide antibodies. Together with the previously described mitochondrial MutT homolog (MTH1) and 8-oxoG glycosylase (OGG1, a functional MutM homolog), mtMYH can protect mitochondrial DNA from the mutagenic effects of 8-oxoG.

INTRODUCTION

Base excision repair by Escherichia coli MutY glycosylase corrects the base-base mismatches A/G and A/C as well as adenine and guanine paired with 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-deoxyguanine (8-oxoG) that arise through DNA replication errors and DNA recombination (1–9). Together with MutM and MutT, the MutY protein helps to protect the bacteria from the mutagenic effects of 8-oxoG (10,11), the most stable product known caused by oxidative damage to DNA (12,13). The formation of 8-oxoG in DNA, if unrepaired, can lead to the misincorporation of adenine opposite the 8-oxoG lesion resulting in a C:G→A:T transversion (14–17). The MutT protein has nucleoside triphosphatase activity that eliminates 8-oxo-dGTP from the nucleotide pool (18–20). The MutM protein (Fpg protein) provides a second level of defense by removing both mutagenic 8-oxoG adducts and ring-opened purine lesions (21,22). MutM efficiently removes 8-oxoG lesions opposite C but very poorly if opposite A. MutY glycosylase provides a third level of defense by removing the adenines or guanines misincorporated opposite 8-oxoG following DNA replication.

Information regarding mammalian MutY proteins is emerging. Mammalian MutY homologous (MYH) activities have been detected in the nuclear fractions of calf thymus, Jurkat and HeLa cells (23–25). The mammalian MYH has adenine glycosylase and binding activities on A/8-oxoG and A/G mismatches and has recently been shown to possess glycosylase activity on 2-hydroxyadenine paired with A, G, T, C and 8-oxoG (24). cDNA encoding part of the mouse MutY homolog has been cloned (GenBank accession nos AI0409068 and AA409965), although expression and characterization of the gene product remains unpublished (26). The gene for a human MutY protein (hMYH) has been cloned (27) and the predicted size of this hMYH is 59 kDa similar to the size of a band detected in HeLa nuclear extracts with an anti-MutY antibody (25). Recently the hMYH protein from the cloned cDNA has been expressed in an in vitro transcription/translation system (28) and in E.coli (26,29) and partially characterized. This expressed recombinant hMYH has adenine glycosylase activity on the A/8-oxoG mismatch but very weak activity on the A/G mismatch. Human cells have also been shown to possess MutT (hMTH1) and MutM homologs (hOGG1) (30–33). These three enzymes (hMYH, hMTH1 and hOGG1) are proposed to function in the reduction of 8-oxoG in the human genome.

In the mitochondria, 8-oxoG is one of the most abundant lesions formed by exposure to reactive oxygen species (ROS), generated as by-products of cellular respiration (13). The accumulation of oxidative lesions and alterations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) has been implicated in aging and several human diseases such as carcinogenesis, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease (34–36). Because the oxidative environment of this organelle creates unfavorable conditions for DNA stability and, unlike nuclear DNA, the mitochondrial genome is not protected by histone proteins, it is reasonable to assume that the mitochondria possess some effective means of repairing DNA damage frequently generated in their genome.

Studies have indicated that the mitochondria contain base excision repair pathways responsible for the removal of oxidatively damaged DNA lesions. It has been shown that DNA lesions caused by oxidative damage, in particular 8-oxoG, induced in Chinese hamster ovary cells are rapidly removed from the mitochondrial genome suggesting the presence of a 8-oxoG glycosylase/AP lyase (OGG1) (37). Croteau et al. partially purified a 25–30 kDa base excision endonuclease that preferentially cleaved C/8-oxoG mismatches but not A/G or A/8-oxoG (38). These OGG1 or MutM-like activities are consistent with several processed forms of OGG1 enzyme being localized to the mitochondrion from a single gene (39). In addition, hMTH1, which catalyzes the removal of 8-oxoGTP from the nucleotide pool, and endonuclease III-like (hNth) activities, which remove thymine glycol and fragmented pyrimidines, have been shown to be present in the mitochondria (39,40).

Takao et al. have shown that there are two types of human MYH protein: a mitochondrial form (Type 1) and a nuclear isoform (Type 2) (28). Type 1 hMYH, when transiently expressed, can be transported into the mitochondria and is a DNA glycosylase (28,39). Ohtsubo et al. also showed that a 57 kDa hMYH is localized to the mitochondria (24). However, Tsai-Wu et al. showed that Type 1 hMYH is localized to the nucleus excluding the nucleoli (29). Recently, it was also shown that three different forms of hMYH exist in the nucleus with masses of 52, 53 and 55 kDa, respectively (24). These controversial results remained to be resolved. In this study we demonstrate biochemically, for the first time, that calf mitochondria contains MYH-like DNA glycosylase activity. The purified native calf mitochondrial MYH has a molecular mass of 35–40 kDa and cross-reacts with both anti-MutY and anti-hMYH antibodies. These findings suggest that this protein is a mammalian mitochondrial homolog of the E.coli MutY protein, which we have named mtMYH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of mitochondria

Mitochondria were purified from calf liver using a combination of differential and Ficoll gradient centrifugation (41,42). All procedures were carried out at 4°C. Briefly, fresh calf livers (6 kg) were chopped into pieces, rinsed in 154 mM NaCl and homogenized in a Warring blender with 2 l of IM buffer (225 mM mannitol, 2 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 75 mM sucrose, 0.1 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). After centrifugation at 750 g for 30 min, supernatants were pooled, filtered through a gauze and centrifuged for a further 30 min at 7500 g to pellet the mitochondria. The mitochondria were resuspended in 50 ml IM buffer, centrifuged and washed twice. The mitochondrial pellets were resuspended in 30 ml buffer A (20 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM EDTA and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) containing 50 mM KCl with 5 ml aliquots loaded into ultracentrifuge tubes that contained 20 ml 30% (w/v) Ficoll in 225 mM mannitol, 1 mM EDTA, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 0.1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin and spun for 30 min at 95 000 g in a Beckman L8-80M Ultracentrifuge using a Beckman 50.2Ti rotor. Mitochondria were collected from the bottom of the dense yellow/brown band, washed in IM buffer by ultracentrifugation and resuspended in seven 50 ml aliquots in IM buffer and stored at –80°C until lysis.

Proteinase K treatment of mitochondria

Purified intact mitochondria were treated with Proteinase K (10 mg/ml) for 20 min at 0°C to remove any contaminating enzymes from the cytoplasm or nuclei. A control was run concurrently without Proteinase K. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 2 µg/ml Pefabloc. The mitochondria were then centrifuged at 7500 g for 20 min at 4°C, washed twice in IM buffer and lysed as described in the purification procedure.

Fractionation of mitochondria

Fractionation of calf liver mitochondria was performed as previously described (43). Briefly, 10 ml of mitochondria (∼30 mg/ml protein) was diluted to 25 ml with buffer A, to which was added 25 ml of 1.2% digitonin and stirred gently at 0°C. After 15 min, 30 ml of IM buffer was added and the solution centrifuged at 10 000 g for 10 min. The supernatant (S1) was stored on ice and the pellet was resuspended in 20 ml IM buffer and centrifuged for 10 min. The supernatant was added to the S1 supernatant fraction to form the ‘Outer Membrane fraction’. The pellet was resuspended in Lubrol WX (ICN, Costa Mesa, CA) and left to stand at 0°C. After 15 min, the solution was diluted 2-fold with IM buffer and ultracentrifuged at 144 000 g for 1 h. The pellet was resuspended in 20–30 ml IM buffer and represented the ‘Inner Membrane fraction’ while the supernatant represented the ‘Soluble Matrix fraction’.

Organelle marker enzyme assays

Malate dehydrogenase activity (a marker enzyme in the mitochondrial matrix) was measured by monitoring the oxidation of NADH at 340 nm during the reduction of oxaloacetate to malate as previously described (40). Reactions (1 ml) contained 89 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 250 µM NADH, 20 µM oxaloacetate and the protein sample. Monoamine oxidase activity (a marker enzyme in the outer mitochondrial membrane) was determined by measuring the increase in absorbance at 314 nm with the oxidation of kynuramine to 4-hydroxyquinoline (44). The reaction buffer contained 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, 0.2% Triton X-100, 1 mM kynuramine and the protein sample in a 1 ml volume. Lactate dehydrogenase activity (a marker enzyme for the cytoplasm) was determined by measuring the decrease at 340 nm due to the oxidation of NADH (45). The reaction buffer contained 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 8 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.2 mM NADH and the protein sample in a 1 ml volume. Sodium pyruvate was added last to minimize non-specific NADH oxidation.

Purification of calf mtMYH from mitochondria

Purified mitochondria (100 ml) were diluted 3-fold with buffer T (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.6, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 500 mM KCl) containing 2 µg/ml each of the following protease inhibitors: aprotinin, pepstatin A, chymostatin A and leupeptin. For lysis, 10% Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 1% and the resulting solution sonicated for 10 s using a Fischer Scientific 550 Sonic Dismembrator. The solution was clarified by centrifugation at 100 000 g for 1 h (Fraction I).

An aliquot of 25% streptomycin sulfate (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO), in buffer T was added slowly to the clarified mitochondria solution to a final concentration of 5% and then centrifuged for 30 min at 12 000 g. To the pooled supernatant (Fraction I) was added ammonium sulfate to 40% saturation and then centrifuged for 30 min at 12 000 g. Again the supernatant was pooled, ammonium sulfate was added to 50% saturation and then centrifuged for 30 min at 12 000 g. The pellet was resuspended in 65 ml of buffer A containing 50 mM KCl and dialyzed extensively versus the same buffer. This was designated Fraction II (85 ml). Fraction II was diluted to 250 ml with buffer A containing 50 mM KCl and loaded onto a 40 ml phosphocellulose PC-11 (Whatman Laboratories, Kent, UK) column equilibrated with buffer A containing 50 mM KCl. After the column was washed with three volumes of equilibration buffer, proteins were eluted using a 500 ml linear gradient of KCl (0.05–1.0 M) in buffer A. Fractions eluting at 250 mM KCl and exhibiting A/8-oxoG binding activity were pooled (Fraction III, 20 ml) and dialyzed against buffer B (10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM EDTA and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Fraction III was applied to 13 ml single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) cellulose (Sigma Chemical Co.) column equilibrated in buffer B. After the column was washed with three volumes of buffer B, bound proteins were eluted using a 40 ml linear gradient of KCl (0.05–1.0 M) in buffer B. Fractions eluting at 150 mM KCl and exhibiting A/8-oxoG binding activity were pooled (Fraction IV, 2.5 ml), concentrated in a centricon-10 to 0.5 ml, washed five times with buffer P (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1 mM EDTA and 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) in the centricon-10 and applied to a Q-sepharose column (0.5 ml) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) equilibrated in buffer P. The column was washed with three volumes of buffer P and bound proteins eluted with buffer P containing 1 M KCl. Fractions with A/8-oxoG binding activity eluting in buffer P with 1 M KCl were pooled (Fraction V, 0.5 ml), concentrated to 0.15 ml using a centricon-10, and applied to a 24.5 ml calibrated Superose 12 (Pharmacia Biotech) gel filtration column equilibrated with buffer A containing 200 mM KCl. Fractions containing A/8-oxoG binding activity were pooled, concentrated (Fraction VI, 0.3 ml), using a centricon-10, divided into small aliquots and stored at –80°C.

Preparation of antibodies against MutY and hMYH

Antibodies against full-length E.coli MutY and an E.coli MutY peptide (residues 192–211) were raised in rabbits and prepared essentially as described previously (23). Antibodies against the hMYH peptides, α-344 (against residues 344–361, amino acid sequence FPRKASRKPPREESSATC) and α-516 (against residues 516–534 with cysteine at the N-terminus, amino acid sequence CDNFFRSHISTDAHSLNSAA) were raised in rabbits. For purification of the peptide antibodies, CNBr sepharose matrices (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were activated with 1 mM HCl, washed with 1 mM HCl and 0.125 M phosphate coupling buffer and then coupled with the synthetic peptide at 4°C overnight. The coupled matrices were washed with coupling buffer and incubated with 1 M ethanolamine, pH 8.0, blocking buffer for 5 h at 4°C. The matrices were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and packed into a 10 ml column. An equal volume of PBS was added to 6 ml of antisera, filtered and loaded onto the column with a Waters 650 FPLC system at 4°C. After washing with 40 ml of PBS, the antibodies against the hMYH peptides were eluted with elution buffer containing 63 mM glycine, pH 2.3 and 0.2 M NaCl. Samples (0.75 ml) were collected into tubes containing 0.25 ml of neutralizing buffer (0.5 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.5). Antibody titer was performed by ELISA.

Western blot (immunoblot) analysis

Protein fractions were resolved on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel (46) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (47). The membrane was subjected to the Enhanced Chemiluminescence analysis system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, except that the blocking buffer contained 10% non-fat dry milk (Carnation) and the wash solution contained 1% non-fat dry milk.

DNA substrates

Annealed 19mer duplexes were prepared as previously described (23):

5′-CCGAGGAATTZGCCTTCTG -3′

3′- GCTCCTTAAXCGGAAGACG-5′

where Z = A, 2-aminopurine (2-AP), C, G or T and X = G, C or 8-oxoG.

19mer duplexes were radiolabeled at the 3′-end of the upper strand with Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I for 30 min at 25°C in the presence of [α-32P]dCTP (50 µCi at 3000 Ci/mmol) and 20 µM of dGTP (48). The resulting blunt-end DNA duplexes were 20 bp long. The reaction mixture was passed through a G25 Quick-Spin column (Boehringer Mannheim) and the purified duplexes stored at –20°C.

DNA glycosylase assay

The DNA cleavage activity (DNA glycosylase activity followed by heating) of E.coli MutY glycosylase was assayed as previously described (49). The glycosylase activity for mtMYH was assayed using similar conditions except that different buffer and incubation times were used. Protein samples were incubated with 1.8 fmol 3′-end labeled 20mer duplex DNA in a 10 µl reaction mixture containing 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.6, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.5 mM EDTA and 15% (v/v) glycerol. After either a 30 or 60 min incubation at 37°C, the reaction products were lyophilized and dissolved in 3 µl of loading dye containing 90% (v/v) formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 0.1% (w/v) xylene cyanol and 0.1% (w/v) bromophenol blue. The DNA samples were heated at 90°C for 2 min and analyzed on 14% polyacrylamide–7 M urea sequencing gels (50). The gel was then autoradiographed. For some experiments, some samples were not heated at 90°C for 2 min before loading the gel and some samples were supplemented with 1 M piperidine and heated at 90°C for 30 min after mtMYH incubation.

Gel mobility shift analyses

The formation of protein–DNA complexes was analyzed by gel retardation assay on 8% polyacrylamide gels in 50 mM Tris–borate, pH 8.3 and 1 mM EDTA as previously described (49). Protein samples were incubated with 1.8 fmol 3′-end labeled 20mer duplex DNA in a 20 µl reaction mixture containing the same buffer used in the glycosylase assay except that 20 ng of poly(dI-dC), 20 mM NaCl and 25 mM EDTA were added. Following either a 30 or 60 min incubation at 37°C, 1.5 µl of 50% glycerol was added and the reaction products loaded directly onto the gel.

Determination of DNA cleavage in the mtMYH-bound DNA fractions

Calf mtMYH (fraction IV, 210 µg) was incubated in the standard gel mobility assay for 60 min at 37°C except that 30 fmol 3′-end labeled 20mer duplex DNA and 200 ng of poly(dI-dC) were used. After fractionation on an 8% polyacrylamide gel, the protein-bound and protein-free DNA were excised from the gel and eluted by electrophoresis into dialysis tubing containing 400 µl TBE buffer (50 mM Tris–borate, pH 8.3, 1 mM EDTA) and 12 µg/ml tRNA. The DNA samples were twice extracted with phenol, precipitated with ethanol and fractionated on a 14% polyacrylamide–7 M urea sequencing gel. The gel was then autoradiographed.

Trapping assay

Covalent trapping of mtMYH with A/8-oxoG in the presence of sodium borohydride was performed using the method of Lu et al. (51). Protein samples were incubated with 1.8 fmol 3′-end labeled 20mer duplex DNA in a 20 µl reaction mixture containing the same buffer used in the glycosylase assay and different concentrations of NaBH4. A NaBH4 stock solution (1 M) was freshly prepared and added immediately after the enzyme was added. After incubation at 37°C for 60 min, the products were separated on a 12% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of SDS (SDS–PAGE), and the gel was dried and autoradiographed.

Other methods

Protein concentrations were determined using the method of Bradford (52). Phosphoimager quantitative analyses of gel images were performed as mentioned previously (2).

RESULTS

A/8-oxoG mismatch binding activity is located in the mitochondrial matrix

To demonstrate that mammalian mitochondria contain a MYH DNA glycosylase, the binding activity of the A/8-oxoG mismatch was assayed with the mitochondrial extract. As shown in Figure 1 (lane 1), the lysate from Ficoll-purified mitochondria contained an A/8-oxoG binding activity. To assess the purity of the purified mitochondria, the level of cytosolic contamination was estimated by measuring lactate dehydrogenase activity (a cytosolic enzyme). The lactate dehydrogenase activities were 11.7 and 0.25 µmol/min/mg for crude liver homogenate and for the Ficoll-purified mitochondrial lysate (Fraction I), respectively. Therefore, a 48-fold enrichment of mitochondria was achieved. To confirm that the binding activity of the A/8-oxoG oligonucleotide was in fact located within the mitochondria, Ficoll-purified intact mitochondria were treated with proteinase K for 20 min at 0°C before lysis. When compared with Ficoll-purified mitochondria that had not been exposed to proteinase K, >90% of A/8oxo-G binding activity remained after proteinase K treatment (Fig. 1, lane 3).

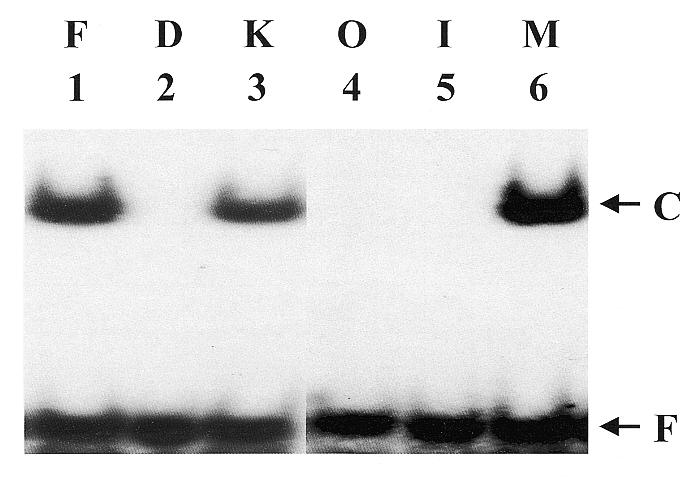

Figure 1.

Calf mtMYH is localized in the mitochondrial matrix. Lane 2 contains the A/8-oxoG mismatch oligonucleotide only (D). One hundred micrograms of protein from the non-Proteinase K treated (lane 1, F) and Proteinase K treated Ficoll-purified mitochondria lysate (lane 3, K) were assayed for binding with A/8-oxoG-containing oligonucleotide as described in Materials and Methods. The mitochondrial lysate was fractionated using digitonin as described and each fraction was assayed for A/8-oxoG mismatch binding activity. Lanes 4–6 contain reactions which contained 100 µg of the outer membrane and inter-membrane protein fraction (lane 4, O), 100 µg of the inner membrane fraction (lane 5, I) or 100 µg of the matrix protein fraction (lane 6, M). Arrows indicate the positions of free DNA (F) and enzyme-bound DNA complex (C). Quantitation of the gel is shown in Table 1.

To establish the intra-mitochondrial location of this A/8-oxoG binding activity, the mitochondria were incubated with digitonin as previously described (43) to produce sub-mitochondrial fractions: the matrix, inner membrane and outer membrane with inter-membrane space. Monoamine oxidase (44) and malate dehydrogenase (40) were assayed to ascertain the efficiency of this fractionation (Table 1). Monoamine oxidase activity was located in the outer membrane fraction whereas the majority of the malate dehydrogenase activity was detected in the matrix fraction (Table 1). A similar overflow of marker enzyme activities were found present in the sub-mitochondrial preparations of others (38) and may be due in part to the presence of other enzymes utilizing the substrates. Nevertheless, the location of the marker enzymes showed that the fractionation was effective. When the mitochondrial fractions were assayed for A/8-oxoG binding, all the activity was detected in the mitochondrial matrix fraction (Table 1; Fig. 1, lane 6).

Table 1. Localization of total A/8-oxoG binding activity within calf liver mitochondria.

| Fraction | Marker enzymes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Malate dehydrogenase (units)a | Monoamine oxidase A (units)b | mtMYH (units)c | |

| Outer membrane and inter-membrane | 174 ± 4d | 131 ± 8 | 0 |

| Inner membrane | 428 ± 9 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| Matrix | 1759 ± 63 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 75 300 ± 5400 |

The total activities shown in this table were from 10 ml of Ficoll-purified mitochondria from 0.17 kg of calf thymus and each value was obtained from three experiments.

aOne unit of activity is defined as the production of 1 µmol NAD+ per minute.

bOne unit of activity is defined as the production of 1 µmol 4-hydroxyquinolone per minute.

cOne unit of binding activity is defined as that resulting in binding of 1% (0.018 fmol) of 3′-labeled DNA 20mer with an A/8-oxoG mismatch at 37°C for 30 min.

dAll values are presented as mean values ± the standard deviation.

Purification of calf mtMYH

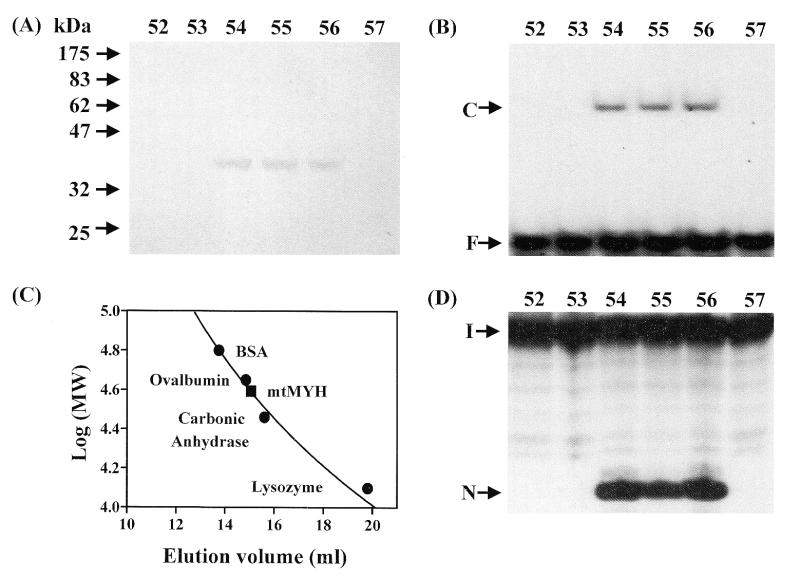

The A/8-oxoG binding activity was purified ∼475-fold from the isolated mitochondria using a combination of ammonium sulfate fractionation and four column chromatography steps (Table 2). A narrow ammonium sulfate cut was employed in the purification in order to remove other non-specific DNA binding proteins. In the final purification step, by Superose 12 gel filtration, a single protein of ∼38 kDa (Fig. 2A) co-purified with the A/8-oxoG binding activity (Fig. 2B). There was good correlation between the intensity of the protein and the A/8-oxoG binding activity (fractions 54–56 contained the 38 kDa band and activity). The molecular mass of the native A/8-oxoG binding activity protein was determined using a calibrated Superose 12 gel filtration column. A/8-oxoG binding activity protein eluted at a position of 35–40 kDa by comparison with molecular mass markers (Fig. 2C) consistent with the single band of ∼38 kDa shown by SDS–PAGE (Fig. 2A). Thus, this protein appears to be a monomer. To verify that the purified A/8-oxoG binding activity protein is similar to E.coli MutY, the adenine glycosylase activity on A/8-oxoG–containing DNA was determined in the fractions from the Superose 12 column. As shown in Figure 2D, the adenine glycosylase activity co-purified with the A/8-oxoG binding activity (Fig. 2B) and the 38 kDa protein (Fig. 2A). The adenine glycosylase activity could also be detected in the earlier fractions of the purification although it was much lower in fractions I and II (Table 2). Thus, we termed the 38 kDa protein with A/8-oxoG binding and glycosylase activities ‘mtMYH’.

Table 2. Purification of mtMYH from calf liver mitochondria.

| Fraction | Volume (ml) |

Protein (mg)a |

Specific activity | Fold purification (A/8-oxoG) binding |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicking (units/mg)b | Binding (units/mg)c | ||||

| (I) Mitochondrial lysate | 400 | 2700 | 10 | 200 | 1 |

| (II) Ammonium sulphate | 85 | 1040 | 55 | 900 | 5 |

| (III) Phosphocellulose | 20 | 40 | 1100 | 2800 | 15 |

| (IV) ssDNA cellulose | 2.5 | 3.1 | 2450 | 4800 | 25 |

| (V) Q-Sepharose | 0.5 | 0.4 | 16 250 | 18 400 | 94 |

| (VI) Superose-12 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 45 000 | 92 700 | 475 |

aProtein concentration was measured by Bradford assay.

bOne unit of nicking activity is defined as that resulting in cleavage of 1% (0.018 fmol) of 3′-labeled DNA 20mer with an A/8-oxoG mismatch at 37°C for 30 min.

cOne unit of binding activity is defined as that resulting in binding of 1% (0.018 fmol) of 3′-labeled DNA 20mer with an A/3-oxoG mismatch at 37°C for 30 min.

Figure 2.

Purification of calf mtMYH by Superose 12 column. Calf mtMYH (fraction V) was purified as described in Materials and Methods and loaded onto a 24.5 ml calibrated Superose 12 gel filtration column and 275 µl fractions were collected. (A) SDS–polyacrylamide analysis. Superose 12 column fractions were concentrated by TCA precipitation, electrophoresed on a 10% SDS–PAGE and stained with silver. The positions of the molecular weight standards (New England Biolabs prestained markers) are marked. (B) A/8-oxoG binding activity of the fractions from Superose 12 column. The positions of free DNA (F) and binding complex (C) are marked. (C) The native molecular mass of mtMYH was estimated to be 35–40 kDa. The Superose 12 column was calibrated with blue dextran (2000 kDa), BSA (66 kDa), ovalbumin (45 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa) and lysozyme (14 kDa). Molecular weight markers (marked by filled circles) were monitored by UV absorption and mtMYH (marked by a filled rectangle) was analyzed by A/8oxo-G binding activity. (D) A/8-oxoG glycosylase activity of the fractions from Superose 12 column. The samples in the loading dye were heated at 90°C for 2 min and electrophoresed in a 14% sequencing gel. The positions of intact DNA substrate (I) and cleaved products (N) are marked. The numbers above (A), (B) and (D) represent the fraction number eluted from the Superose 12 column.

Specificities of DNA binding and glycosylase activities of calf mtMYH

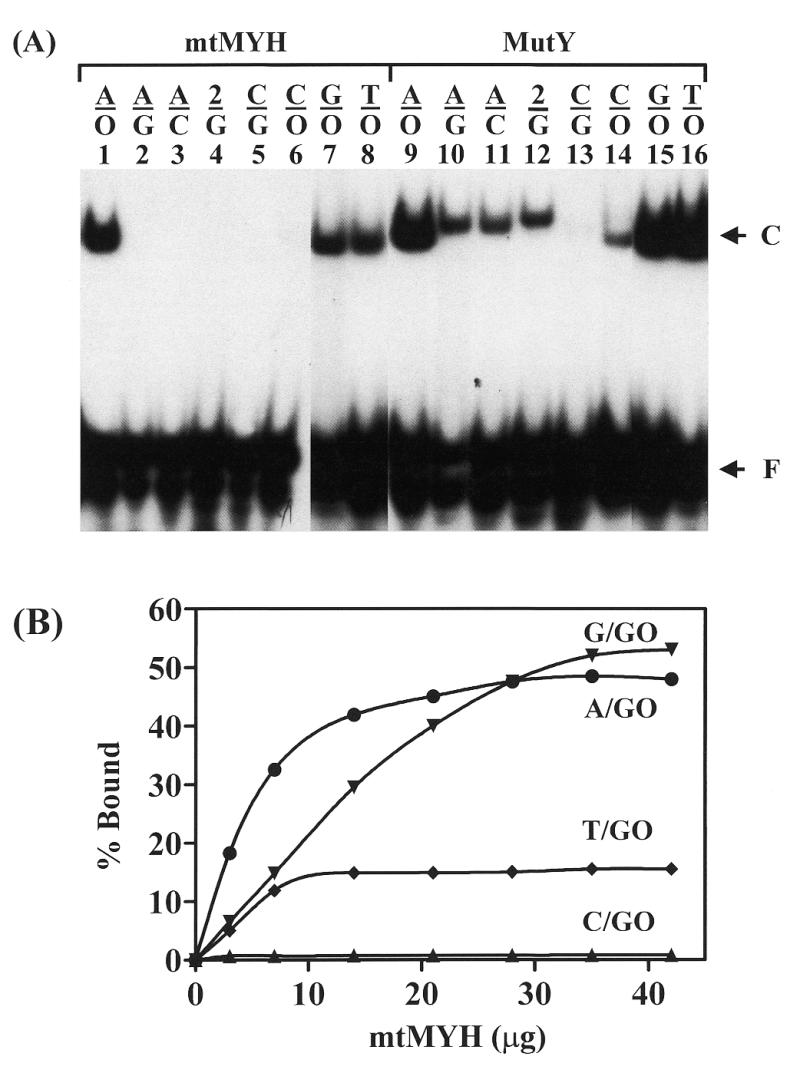

The binding and glycosylase activities of calf mtMYH and E.coli MutY with several mismatches were compared. As shown in Figure 3A, in gel retardation assays, mtMYH bound efficiently to A/8-oxoG-, G/8-oxoG- and T/8-oxoG-containing DNA (lanes 1, 7 and 8) and much more weakly to C/8-oxoG-containing DNA (lane 6). However, unlike MutY, A/G, A/C and 2AP/G mismatches were not bound by mtMYH. Because mtMYH bound all four 8-oxoG mismatches at a fixed concentration we sought to determine its relative affinity for these substrates. Figure 3B showed that substrate binding increased with increased mtMYH amount. As seen with MutY (2), the maximum binding of mtMYH with 8-oxoG-containing substrates did not reach 100% saturation. This may be due to an inherent problem with the band shift assay or the nature of the DNA substrates. At lower concentrations of mtMYH, the affinity was the best with A/8-oxoG mismatch while at higher concentrations of mtMYH, the affinity with A/8-oxoG and G/8-oxoG was similar.

Figure 3.

Calf mtMYH and MutY binding to mismatch-containing DNA substrates. (A) Gel retardation assay with different substrates. Oligonucleotide substrates (3′-end labeled 20mers, 1.8 fmol) were assayed for binding for 60 min at 37°C with 7 µg of partially purified mtMYH (fraction IV eluted from the ssDNA cellulose column) (lanes 1–8) or 3.6 nM MutY (lanes 9–16). 2 represents 2-aminopurine (2AP) and O is for 8-oxoG. Oligonucleotides containing the mismatches are indicated on the top of each lane. The arrows indicate protein bound complex (C) and free DNA (F). Lanes 7, 8, 15 and 16 are from a non-concurrent experiment. (B) Binding affinity of mtMYH with 8-oxoG-containing DNA. A/8-oxoG, C/8-oxoG, G/8-oxoG and T/8-oxoG mismatches were assayed for binding for 60 min at 37°C with increasing amounts of partially purified mtMYH (fraction IV). The symbols are as follows: A/8-oxoG (circles), C/8-oxoG (triangles), G/8-oxoG (inverted triangles) and T/8-oxoG (diamonds). Data were from phosphoimager quantitative analyses of gel images. Percentages of DNA bound from two experiments were plotted as a function of protein amount.

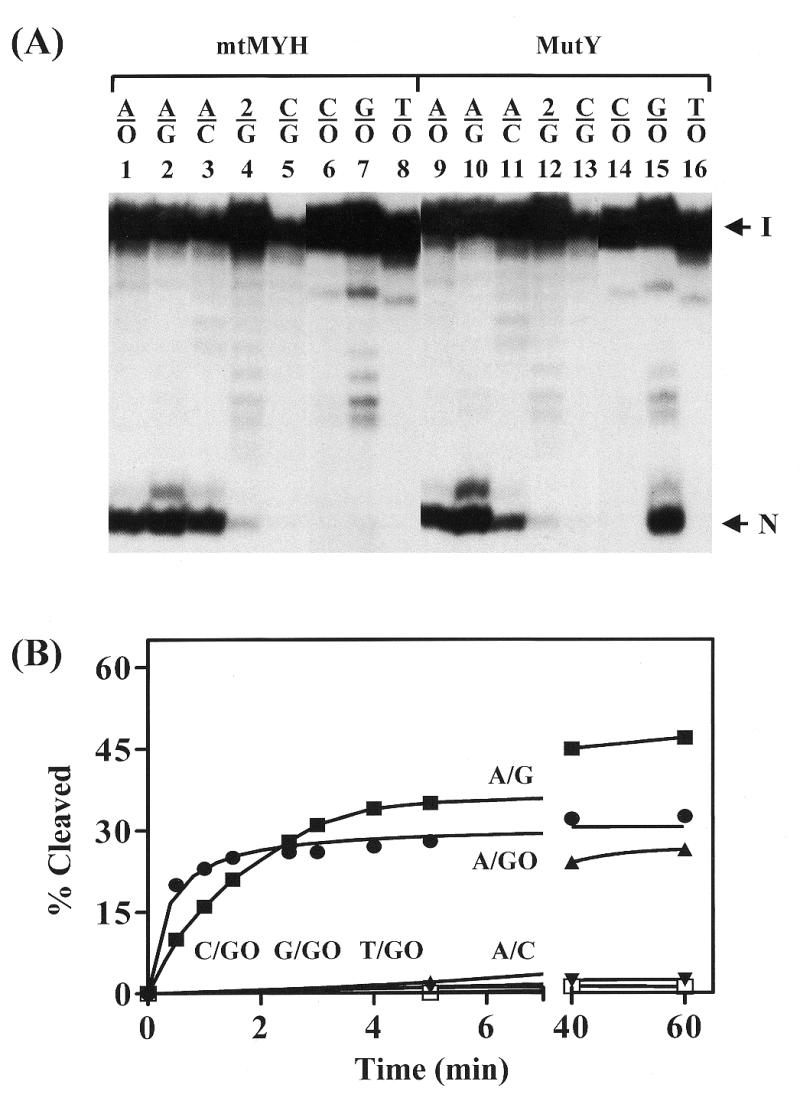

Given that MutY can cleave several mismatches with different efficiency (4), we compared mtMYH and MutY glycosylase activities on different DNA mismatches. As shown in Figure 4A, similar to MutY, mtMYH cleaved A/8-oxoG and A/G efficiently but cleaved 2AP/G weakly (lanes 1, 2, 4, 9, 10 and 12). However, when compared to MutY, A/C mismatch was a better substrate and G/8-oxoG was a poorer substrate for mtMYH (Fig. 4A, lanes 3, 7, 11 and 15). The minor band above the major cleaved product was also a product of the glycosylase activity and was derived from an impurity of DNA substrates that appeared above the intact DNA (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Glycosylase activities of calf mtMYH and MutY on different mismatches. (A) Cleavage of mismatch-containing oligonucleotides. Oligonucleotide substrates (3′-end labeled 20mers, 1.8 fmol) containing indicated mismatches were incubated with 7 µg of partially purified mtMYH (fraction IV) (lanes 1–8) or 3.6 nM MutY (lanes 9–16) for 30 min at 37°C. Oligonucleotides used were the same as Figure 3A. Lanes 6, 7, 8, 14, 15 and 16 are from a non-concurrent experiment. The samples in the loading dye were heated at 90°C for 2 min and electrophoresed in a 14% sequencing gel. Arrows indicate the intact DNA substrate (I) and the cleaved DNA fragment (N). The minor band above the cleaved product was derived from an impurity of DNA substrates that appeared above the intact DNA. (B) Time course of cleavage of different mismatches. A/C, A/G, A/8-oxoG, C/8-oxoG, G/8-oxoG and T/8-oxoG mismatches were assayed for cleavage for various times at 37°C with 7 µg of partially purified mtMYH (fraction IV). The symbols are as follows: A/C (filled triangles), A/G (filled squares), A/8-oxoG (filled circles), C/8-oxoG (open squares), G/8-oxoG (filled inverted triangles) and T/8-oxoG (filled diamonds). Percentage cleaved was calculated from phosphoimager analyses of gel images. Data were from phosphoimager quantitative analyses of gel images. Percentages of DNA cleaved from three experiments were plotted as a function of time.

Time course studies to determine the extent of glycosylase activity of mtMYH on different DNA substrates over the 60 min period were shown in Figure 4B. No cleavage was observed with C/8-oxoG and T/8-oxoG mismatches even with long time incubation. The reactivity of mtMYH on G/8-oxoG-containing DNA is very weak. At short reaction times the rate of cleavage of calf mtMYH was much faster for A/8-oxoG mismatch than other substrates. However, at reaction times longer than 3 min, the reactivity on A/G is greater than on the A/8-oxoG mismatch.

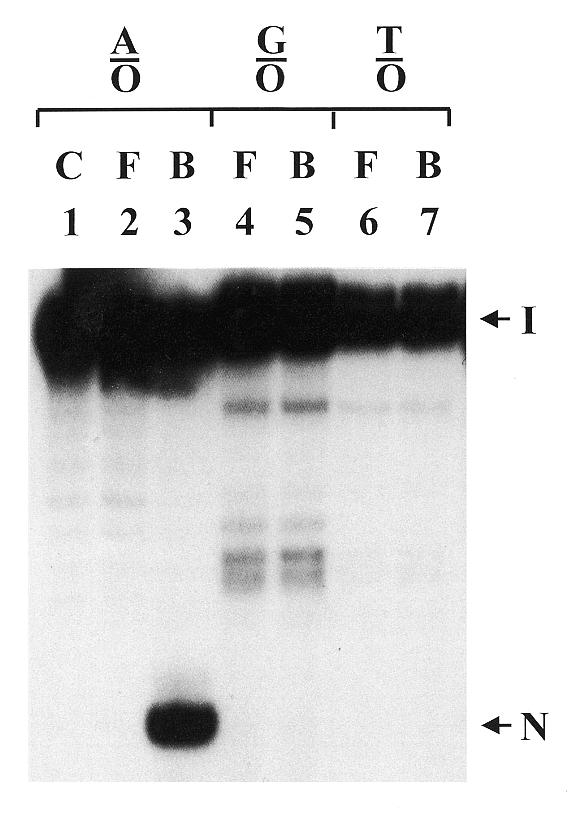

To examine whether the binding activity and glycosylase activity of mtMYH work simultaneously we excised the mtMYH-bound and mtMYH-free DNA bands shown in Figure 3A and analyzed them on a sequencing gel (Fig. 5). On A/8-oxoG and G/8-oxoG mismatches, mtMYH did not dissociate from the DNA substrate after the glycosylase action as the cleaved product was only present in the enzyme-bound fraction but was not observed in the enzyme-free fraction (Fig. 5, lanes 2–5). No cleaved product was present in enzyme-bound and enzyme-free fractions with the T/8-oxoG substrate (Fig. 5, lanes 6 and 7).

Figure 5.

Analysis of DNA cleavage in mtMYH-bound DNA fractions. Calf mtMYH (210 µg) was incubated in the standard gel mobility assay for 60 min at 37°C with 30 fmol 3′-end labeled 20mer duplex DNA and 200 ng of poly(dI-dC). After analysis on an 8% polyacrylamide gel, the enzyme-bound and enzyme-free DNA bands were excised from the gel and electroeluted. The fractions with equal amount of radioactivity in the loading dye were heated at 90°C for 2 min and fractionated on a 14% polyacrylamide–7 M urea sequencing gel. The mismatches used were A/8-oxoG (A/O), G/8-oxoG (G/O) and T/8-oxoG (T/O). DNA with A/8-oxoG was run on the control lane (C). F and B represent samples from enzyme-free and enzyme-bound DNA bands, respectively. Arrows indicate the intact DNA substrate (I) and the cleaved DNA fragment (N).

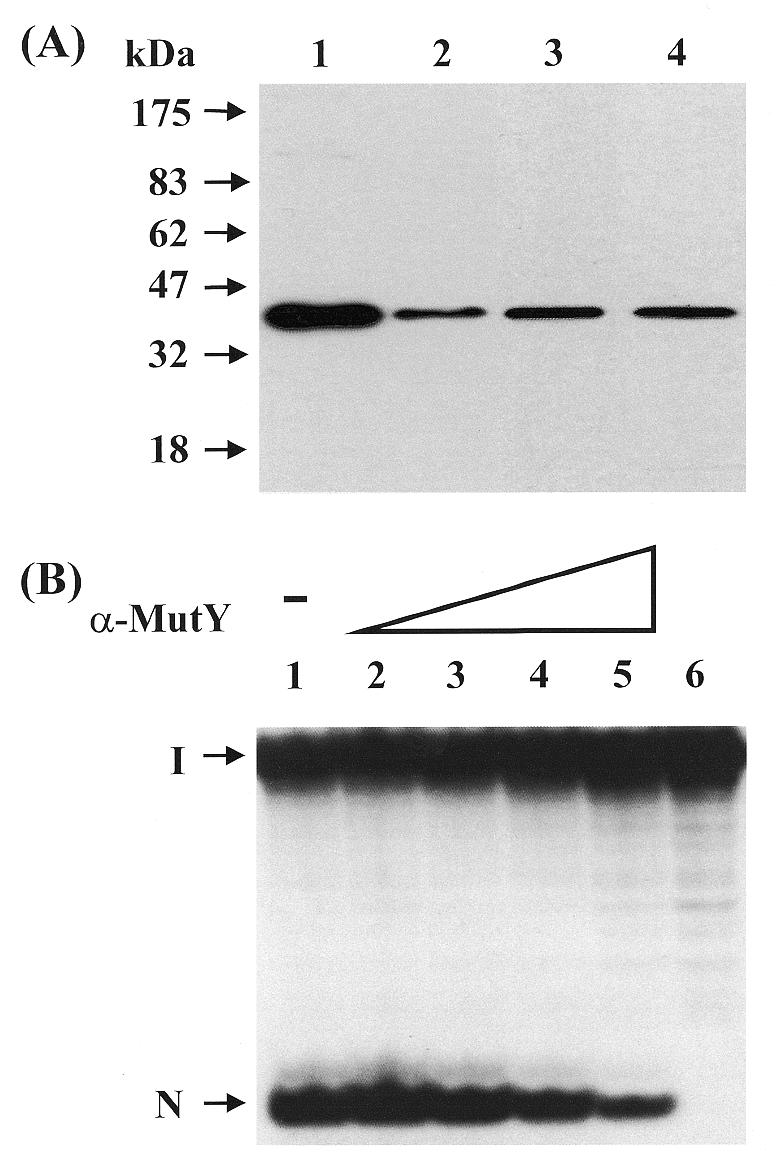

Calf mtMYH cross-reacts with antibodies raised against E.coli MutY and hMYH but only the E.coli MutY antibodies inhibit the DNA glycosylase activity of hMYH

To test for homology of calf mtMYH with E.coli MutY and hMYH, we performed western blotting with polyclonal antibodies raised against full-length E.coli MutY, an E.coli MutY peptide (residues 192–211) and two hMYH peptides (residues 344–361, termed α-344, and residues 516–534, termed α-516). Calf mtMYH cross-reacted with both the anti-full-length MutY and the anti-MutY peptide antibodies (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 3). Thus, calf mtMYH showed considerable homology to E.coli MutY. Calf mtMYH also showed some homology with hMYH because it cross-reacted with the α-516 hMYH peptide antibodies (Fig. 5, lane 4) but not α-344 hMYH peptide antibodies (data not shown). Both α-516 and α-344 antibodies were raised against peptides representing the C-terminus of hMYH.

Figure 6.

Calf mtMYH cross-reacts with antibodies against E.coli MutY and hMYH and the anti-MutY antibodies inhibit its glycosylase activity. (A) Western blot analysis of mtMYH with different antibodies. Proteins were separated on a 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane and allowed to react with antibodies against E.coli MutY and hMYH. Protein fractions used were purified MutY (lane 1) and mtMYH (fraction IV) (lanes 2–4). Antibodies used were: lanes 1 and 2, anti-MutY antibodies; lane 3, anti-MutY peptide antibodies (residues 192–211); and lane 4, anti-hMYH peptide antibodies α-516 (residues 516–534). Lanes 3 and 4 are non-concurrent experiments. Molecular mass standards (New England Biolabs prestained markers) were run in a parallel lane. (B) Inhibition of mtMYH glycosylase activity with anti-MutY antibodies. Calf mtMYH protein was incubated with antibodies against E.coli MutY (α-MutY) for 60 min at 0°C prior to reaction with 3′-end labeled A/8-oxoG-containing substrate for 60 min at 37°C. The cleavage products, after denaturation, were analyzed on a 14% polyacrylamide–7 M urea sequencing gel that was then autoradiographed. The amounts of MutY antibodies used were: lane 1, none; lane 2, 0.05 µg; lane 3, 0.25 µg; lane 4, 1.25 µg and lane 5, 2.5 µg. Lane 6 contains the DNA substrate alone. The arrows indicate the intact DNA (I) and cleavage product (N).

Since calf mtMYH cross-reacted with antibodies raised against both MutY and hMYH in western blot analysis, it was of interest to see whether either antibody could inhibit the enzymatic activity of mtMYH. Pre-incubation of calf mtMYH with increasing amounts of the α-516 antibodies did not inhibit the glycosylase activity of mtMYH (data not shown) whereas pre-incubation with the antibodies raised against the intact MutY protein did (Fig. 6B). The amount of full-length E.coli MutY antibody required for ∼60% inhibition of calf mtMYH glycosylase acitivity (Fig. 6B, lane 5, 2.5 µg) was double that required for the same amount of inhibition of E.coli MutY glycosylase activity using the same antibody (23). The mtMYH glycosylase activity was not inhibited by antibody purification buffer alone or by the control serum (data not shown).

Further characterization of calf mtMYH

Because MYH glycosylase of Schizosaccharomyces pombe is sensitive to EDTA and NaCl (53), we tried to find the optimal reaction conditions for mtMYH. Calf mtMYH glycosylase activity was active in concentration ranges of NaCl and EDTA from 0–320 mM and 0–32 mM, respectively (data not shown). Thus, high concentrations of salt and EDTA did not inhibit the mtMYH glycosylase activity.

Since cleavage of the A/8-oxoG mismatch was observed without heat treatment and was not enhanced by incubation with 1 M piperidine at 90°C for 30 min (data not shown), it appeared that mtMYH had both glycosylase and AP lyase activities. If mtMYH has an AP lyase activity and uses the similar reaction mechanism as MutY does (54), an imino (Shiff base) intermediate should be reduced by NaBH4 to form a covalent protein–DNA complex. To test this, trapping reactions to detect covalently bound enzyme–DNA complexes were performed with mtMYH and A/8-oxoG-containing DNA in the presence of different concentrations of NaBH4. A very weak mtMYH–DNA covalent complex was detected in the presence of (10–50 mM) NaBH4 (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

It is important to protect mtDNA from oxygen radicals produced by the mitochondria themselves (13). The frequency of oxidative damage to DNA has been estimated at 104 lesions/day in a human cell (12). Levels of 8-oxoG in mtDNA have been shown to be higher than that of nuclear DNA and to increase with aging (13). It has been shown that DNA polymerase γ, the replicative polymerase for mtDNA, readily misincorporates 8-oxoGMP opposite adenine (55). In this study, we have demonstrated that calf liver mitochondria contains a MutY-like protein, mtMYH, that can bind A/8-oxoG-containing DNA and remove adenine from this mismatch. The biological significance of calf mtMYH is therefore similar to that of E.coli MutY and hMYH in removal of adenines misincorporated opposite the 8-oxoG lesions and reduces the C:G→A:T transversions.

Our fractionation data show that mtMYH from calf thymus is localized in the mitochondrial matrix which is in disagreement with Ohtsubo et al. who used electron microscopic immunocytochemistry to show that human MYH was associated with the inner mitochondrial membrane (24). A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that MYH is a soluble matrix protein but localizes near the inner mitochondrial membrane. Mitochondrial DNA is composed of a 16.5 kb circular genome encoding 13 structural genes, 22 transfer RNA genes and two ribosomal RNA genes. Since several mitochondrial genomes have been completely sequenced and potential ORFs assigned to proteins other than the base excision repair enzymes (56), it seems likely that calf mtMYH is transported into the mitochondria from the cytoplasm and is encoded from a nuclear gene.

Calf mtMYH possesses adenine glycosylase activity with A/8-oxoG, A/G and A/C mismatches and weak guanine glycosylase activity with G/8-oxoG. Interestingly, DNA containing A/G and A/C mismatches were cleaved but not bound by mtMYH. Thus it is likely that mtMYH does not remain bound to these substrates after cleavage. The reaction with the A/8-oxoG mismatch is totally different. After cleavage, the enzyme remains bound to the A/8-oxoG substrate with high affinity (Fig. 5). Thus, mtMYH has a slow turnover rate with A/8-oxoG-containing DNA. Because mtMYH has different turnover rates on different DNA substrates, the reactions, measured at 37°C for 30 min (Fig. 4A), cannot reflect the true reactivity. Over a short reaction period the rate of cleavage of calf mtMYH was much faster for the A/8-oxoG mismatch than other substrates. This substrate reactivity is similar to that of E.coli MutY (2,57,58).

In view of the fact that mitochondrial OGG1-like protein will cleave 8-oxoG-containing mismatches and not mismatches paired with G, it is of biological importance that mtMYH binds tightly to A/8-oxoG mismatches but not A/G or A/C mismatches. After the removal of adenine from A/8-oxoG by mtMYH, the remaining abasic site/8-oxoG mismatch is a substrate for the OGG1-like protein (30,31,38). If mtMYH were to release this mismatch, before DNA polymerase γ inserts a cytosine opposite the 8-oxoG lesion, mtOGG1 would incise both the AP site and the 8-oxoG lesion resulting in a double-strand break in the mitochondrial DNA. Strong binding to A/8-oxoG by mtMYH after cleavage minimizes this potentially lethal action.

The tight binding of mtMYH to the catalytically inactive substrate T/8-oxoG and weak substrate G/8-oxoG may have biological significance. OGG1 is able to remove 8-oxoG from T/8-oxoG and G/8-oxoG efficiently in vitro (30,31,38). Our laboratory has data to indicate that MutY protein can block and regulate MutM activity (2). Similar to the E.coli MutY/MutM interaction, MYH binding to T/8-oxoG and G/8-oxoG may inhibit OGG1 activity with these substrates. The inhibition of OGG1 activity is especially important if T/8-oxoG and G/8-oxoG mismatches arise from misincorporation of T and G opposite oxidized guanines on the template strand as well as if T/8-oxoG mismatches are derived from the deamination of 5-methylcytosine opposite 8-oxoG (59). The removal of 8-oxoG from T/8-oxoG and G/8-oxoG mismatches, when 8-oxoG is on the parental strand, will lead to G:C→A:T transitions and G:C→C:G transversions. Hence, it is reasonable that OGG1 activity with these mismatches is attenuated before other repair pathways remove the base opposite 8-oxoG.

Calf mtMYH shares some common properties with E.coli MutY and eukaryotic MutY homologs but also has some unique characteristics. Similar to MutY and all the characterized eukaryotic MutY homologs (4,23,25,26,28,29,53), calf mtMYH exhibits binding and glycosylase activities towards mismatches containing A/8-oxoG and like E.coli MutY (4), S.pombe MYH (53) and partially purified calf nuclear MYH (23), also has good adenine glycosylase activity with A/G-containing DNA. However, A/G glycosylase activity is not detected with hMYH expressed by an in vitro transcription/translation system (28) and is very weak from E.coli expressed hMYH (26,29). Although mtMYH binding to A/C-containing DNA is very weak, mtMYH also shows good glycosylase activity with the A/C mismatch.

Calf mtMYH cross-reacts with antibodies raised against the MutY peptide (residues 192–211). Since the amino acids within this region of MutY include four cysteine residues which are conserved between MutY and endonuclease III and are apparently involved in ligation to the [4Fe–4S]2+ cluster (60–63) it may suggest that mtMYH has an iron–sulphur center. Calf mtMYH must also share some conserved domains with hMYH since it cross-reacts with the α-516 antibodies raised against the C-terminal of hMYH. These antibodies fail to inhibit the DNA glycosylase activity of mtMYH implying that the C-terminal domain does not contain the active center.

The molecular mass (35–40 kDa) of purified calf mtMYH is smaller than that of the calf thymus nuclear MYH (60 kDa) (23), recombinant hMYH (∼59 kDa) (25) and different hMYH isoforms (52, 53, 55 and 57 kDa) from HeLa and Jurkat cells (23–25,27,28,39). The question remains, however, whether the purified calf mtMYH is encoded by a different sequence from that of nuclear MYH or is a degraded or processed form of a larger mtMYH. There were two bands (one ∼40 kDa and the other 50 kDa) detected by western blotting with antibodies against hMYH in the early stages of purification of MYH from calf liver mitochondria (data not shown). It is worth noting that the cDNA of hNth1 predicts the protein size to be 38 kDa, similar to mitochondrial Nth1 (64,65), whereas cDNA of four hOGG1 isoforms (1a, b, c and 2) predicts the masses to be 38, 35.5, 45 and 46 kDa which are larger than the reported purified mitochondrial OGG1 homolog (25–30 kDa) (38,66). In human, Type 1 hMYH was shown to be present in the mitochondria by Takao et al. (39) but in the nucleus by Tsai et al. (29). The translation product of the hMYHα3 transcript was also calculated to be 60 kDa, ∼3 kDa larger than the reported 57 kDa (24). The origin of mtMYH awaits further investigation and cloning of its gene.

In conclusion, we are the first to purify and characterize a MutY homolog from the mammalian mitochondria which supports previous evidence of mitochondrial repair of oxidative DNA damage. Together with the previously described mitochondrial MTH1 (40) and OGG1 homolog (38), mtMYH can protect the mtDNA from 8-oxoG-induced mutagenesis.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr Xianghong Li for her help of eluting the DNA bands from gels and Patrick Wright for proof-reading this manuscript. This work was supported by Grant CA 78391 from the National Cancer Institute and Grant GM 35132 from the National Institutes of General Medical Science, National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Au K.G., Cabrera,M., Miller,J.H. and Modrich,P. (1988) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 9163–9166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li X., Wright,P.M. and Lu,A.-L. (2000) J. Biol. Chem., 275, 8448–8455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu A.-L. and Chang,D.-Y. (1988) Genetics, 118, 593–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu A.-L., Tsai-Wu,J.-J. and Cillo,J. (1995) J. Biol. Chem., 270, 23582–23588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michaels M.L., Cruz,C., Grollman,A.P. and Miller,J.H. (1992) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 89, 7022–7025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michaels M.L., Tchou,J., Grollman,A.P. and Miller,J.H. (1992) Biochemistry, 31, 10964–10968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radicella J.P., Clark,E.A. and Fox,M.S. (1988) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 85, 9674–9678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su S.-S., Lahue,R.S., Au,K.G. and Modrich,P. (1988) J. Biol. Chem., 263, 6829–6835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Q.M., Ishikawa,N., Nakahara,T. and Yonei,S. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 4669–4675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michaels M.L. and Miller,J.H. (1992) J. Bacteriol., 174, 6321–6325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tchou J. and Grollman,A.P. (1993) Mutat. Res., 299, 277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraga C.G., Shigenaga,M.K., Park,J.-W., Degan,P. and Ames,B.N. (1990) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 4533–4537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shigenaga M.K., Hagen,T.M. and Ames,B.N. (1994) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 91, 10771–10778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng K.C., Cahill,D.S., Kasai,H., Nishimura,S. and Loeb,L.A. (1991) J. Biol. Chem., 267, 166–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moriya M. (1993) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 90, 1122–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moriya M., Ou,C., Bodepudi,V., Johnson,F., Takeshita,M. and Grollman,A.P. (1991) Mutat. Res., 254, 281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wood M.L., Dizdaroglu,M., Gajewski,E. and Essigmann,J.M. (1990) Biochemistry, 29, 7024–7032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akiyama M., Maki,H., Sekiguchi,M. and Horiuchi,T. (1989) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 86, 3949–3952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhatnagar S. and Bessman,M.J. (1988) J. Biol. Chem., 263, 8953–8957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maki H. and Sekiguchi,M. (1992) Nature, 355, 273–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chetsanga C.J. and Lindahl,T. (1979) Nucleic Acids Res., 6, 3673–3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tchou J., Kasai,H., Shibutani,S., Chung,M.-H., Grollman,A.P. and Nishimura,S. (1991) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 4690–4694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGoldrick J.P., Yeh,Y.-C., Solomon,M., Essigmann,J.M. and Lu,A.-L. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol., 15, 989–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohtsubo T., Nishioka,K., Imaiso,Y., Iwai,S., Shimokawa,H., Oda,H., Fujiwara,T. and Nakabeppu,Y. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 1355–1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeh Y.-C., Chang,D.-Y., Masin,J. and Lu,A.-L. (1991) J. Biol. Chem., 266, 6480–6484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slupska M.M., Luther,W.M., Chiang,J.H., Yang,H. and Miller,J.H. (1999) J. Bacteriol., 181, 6210–6213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slupska M.M., Baikalov,C., Luther,W.M., Chiang,J.-H., Wei,Y.-F. and Miller,J.H. (1996) J. Bacteriol., 178, 3885–3892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takao M., Zhang,Q.M., Yonei,S. and Yasui,A. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 3638–3644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai-Wu J.-J., Su,H.-T., Wu,Y.-L., Hsu,S.-M. and Wu,C.H.H. (2000) J. Cell Biochem., 77, 666–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arai K., Morishita,K., Shinmura,K., Kohno,T., Kim,S.R., Nohmi,T., Taniwaki,M., Ohwanda,S. and Yokota,J. (1997) Oncogene, 41, 2857–2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radicella J.P., Dherin,C., Desmaze,C., Fox,M.S. and Boiteux,S. (1997) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 8010–8015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenquist T.A., Zharkov,D.O. and Grollman,A.P. (1997) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 7429–7434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakumi K., Furuichi,M., Tsuzuki,T., Kakuma,T., Kawabata,S.-I., Maki,H. and Sekiguchi,M. (1993) J. Biol. Chem., 268, 23524–23530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grossman L.I. and Shoubridge,E.A. (1996) Bioessays, 18, 983–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei Y.H. (1998) Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med., 217, 53–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zorov D.B. (1996) Biochem. Biophys. Acta, 1275, 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.LeDoux S.P., Wilson,G.L., Beecham,E.J., Stevnsner,T., Wassermann,K. and Bohr,V.A. (1992) Carcinogenesis, 13, 1967–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Croteau D.L., ap Rhys,C.M., Hudson,E.K., Dianov,G.L., Hansford,R.G. and Bohr,V.A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem., 272, 27338–27344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takao M., Aburatani,H., Kobayashi,K. and Yasui,A. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 2917–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang D., Nishida,J., Iyama,A., Nakabeppu,Y., Furuichi,M., Fujiwara,T., Sekiguchi,M. and Takeshige,K. (1995) J. Biol. Chem., 270, 14659–14665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bertrand C., Dumoulin,R., Divry,P., Mathieu,M. and Vianey-Saban,C. (1992) Clin. Chim. Acta, 210, 75–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hovius R., Lambechts,H., Nicolay,K. and deKruijff,B. (1990) Biochem. Biophys. Acta, 1021, 217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenwalt J.W. (1974) Methods Enzymol., 31, 310–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiessbach H., Smith,T.E., Daly,J.W., Witkop,B. and Udenfriend,S. (1960) J. Biol. Chem., 235, 1160–1163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kochhar S., Hunzicker,P.E., Leong-Morgenthaler,P. and Hovius,R. (1992) J. Biol. Chem., 267, 8499–8513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laemmli U.K. (1970) Nature, 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Towbin H.T., Staehlin,T. and Gordon,J. (1979) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 76, 4350–4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maniatis T., Fritsch,E.F. and Sambrook,J. (1982) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 49.Lu A.-L. and Chang,D.-Y. (1988) Cell, 54, 805–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maxam A.M. and Gilbert,W. (1980) Methods Enzymol., 65, 499–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu A.-L., Yuen,D.S. and Cillo,J. (1996) J. Biol. Chem., 271, 24138–24143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bradford M. (1976) Anal. Biochem., 72, 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu A.-L. and Fawcett,W.P. (1998) J. Biol. Chem., 273, 25098–25105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gogos A., Cillo,J., Clarke,N.D. and Lu,A.-L. (1996) Biochemistry, 35, 16665–16671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pavlov Y.I., Minnick,D.T., Izuta,S. and Kunkel,T.A. (1994) Biochemistry, 33, 4695–4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shinmura K., Kasai,H., Sasaki,A., Sugimura,H. and Yokota,J. (1997) Mutat. Res., 385, 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.David S.S. and Williams,S.D. (1998) Chem. Rev., 98, 1221–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Noll D.M., Gogos,A., Granek,J.A. and Clarke,N.D. (1999) Biochemistry, 38, 6374–6579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vanyushin B.F. and Kirnos,M.D. (1977) Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 475, 323–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guan Y., Manuel,R.C., Arvai,A.S., Parikh,S.S., Mol,C.D., Miller,J.H., Lloyd,S. and Tainer,J.A. (1998) Nat. Struct. Biol., 5, 1058–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuo C.-F., McRee,D.E., Fisher,C.L., O’Handley,S.F., Cunningham,R.P. and Tainer,J.A. (1992) Science, 258, 434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Michaels M.L., Pham,L., Nghiem,Y., Cruz,C. and Miller,J.H. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 3841–3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsai-Wu J.-J., Radicella,J.P. and Lu,A.-L. (1991) J. Bacteriol., 173, 1902–1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stierum R.H., Croteau,D.L. and Bohr,V.A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem., 274, 7128–7136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aspinwall R., Rothwell,D.G., Roldan-Arjona,T., Anselmino,C., Ward,C.J., Cheadle,J.P., Sampson,J.R. and Lindahl,T. (1997) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aburatani H., Hippo,Y., Ishida,T., Takashima,R., Matsuba,C., Kodama,T., Takao,M., Yasui,A., Yamamoto,K., Asano,M. et al. (1997) Cancer Res., 57, 2151–2156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]