Abstract

Mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) impart a neomorphic reaction that produces the oncometabolite D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D2HG), which can inhibit DNA and histone demethylases to drive tumorigenesis via epigenetic changes. Though heterozygous point mutations in patients primarily affect residue R132, there are myriad D2HG-producing mutants that display unique catalytic efficiency of D2HG production. Here, we show that catalytic efficiency of D2HG production is greater in IDH1 R132Q than R132H mutants, and expression of IDH1 R132Q in cellular and mouse xenograft models leads to higher D2HG concentrations in cells, tumors, and sera compared to R132H-expressing models. Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) analysis of xenograft tumors shows expression of IDH1 R132Q relative to R132H leads to hypermethylation patterns in pathways associated with DNA damage. Transcriptome analysis indicates that the IDH1 R132Q mutation has a more aggressive pro-tumor phenotype, with members of EGFR, Wnt, and PI3K signaling pathways differentially expressed, perhaps through non-epigenetic routes. Together, these data suggest that the catalytic efficiency of IDH1 mutants modulate D2HG levels in cellular and in vivo models, resulting in unique epigenetic and transcriptomic consequences where higher D2HG levels appear to be associated with more aggressive tumors.

Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) is a homodimeric enzyme that catalyzes the reversible NADP+-dependent oxidation of isocitrate (ICT) to α-ketoglutarate (αKG) in the cytoplasm and peroxisomes. Somatic mutations in IDH1 have been implicated in lower grade gliomas, chondrosarcomas, and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas (recently reviewed in 1). These mutations typically ablate this conventional activity, but more importantly provide a gain of neomorphic function: the NADPH-dependent conversion of αKG to the oncometabolite, D-2-hydroxyglutarate (D2HG)2. D2HG can competitively inhibit αKG-dependent enzymes such as the 5-methylcytosine hydroxylase TET2 and JmjC lysine demethylases to result in increased DNA and histone methylation in patients, respectively3–8. We have shown previously that mutations in IDH1 is sufficient to cause the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP)9, which has been established as a clinical diagnostic and prognostic feature of tumors, as glioma CIMP (G-CIMP) cases are associated with better outcomes10.

Tumor-driving IDH1 mutations affect residue R132, with R132H by far the most common in patients2,11. However, in a few tumor types, the R132C mutation is preferred or at least highly frequent, making up nearly half of the IDH1 mutations seen in central cartilaginous tumors, for example12. A variety of tumor types have more rare mutations, including IDH1 R132G, R132L, R132S, etc11. Residue 132 directly interacts with the C3 carboxylate of ICT2,13–15 and also stabilizes an important regulatory domain, the α10 helix, to help keep the protein in an open, inactive conformation or closed, active conformation depending on whether substrate is bound2,13,14,16,17. Thus, it has been shown that loss of arginine at residue 132 likely helps favor a closed conformation and to drive the equilibrium towards αKG and NADPH (versus isocitrate and NADP+) binding, explaining why there is some permissiveness in the mutations seen at residue 1322,15. However, it is still not clear if there are any differences in tumor formation or growth among these IDH1 mutations.

We and others have been interested in determining if different IDH1 mutations lead to different features in IDH1-driven tumors. Others have reported that glioma tissue (expressing IDH1 R132H/C/G mutations) and cell line models (expressing IDH1 R132H/C/G/S/L mutations) had varying concentrations of D2HG depending on the IDH1 mutation present, with R132H associated with the lowest levels of D2HG18, though no changes in overall survival were observed with patients with IDH1 R132C/G/S/L/K mutations versus R132H19. We previously reported that kinetic features may play some role in these observed differences, noting that purified IDH1 R132Q was far more catalytically efficient at D2HG production than R132H20,21 due to activating structural features22. An extensive study on astrocytomas binned as R132H mutated and non-R132H IDH1/2-mutated (which included R132C/L/G/S and IDH2 R140Q/W/G/L and R172W/K/M/G/S/T) showed that non-R132H IDH1/2-mutated tumors had overall increased DNA methylation, decreased gene expression, and better prognosis, suggesting an intriguing possibility of differences in methylation phenotype intensity within IDH1 mutants and/or among IDH1 and IDH2 mutants23. Similar findings were recapitulated in additional meta analyses24.

Here, we sought to determine the in vitro and in vivo consequences of two IDH1 mutations with profoundly different kinetic parameters. We generated ectopic mouse tumor xenografts from either glioma or chondrosarcoma cell lines we modified to stably over-expressing IDH1 WT, R132H or R132Q to allow us to perform comprehensive epigenomic and transcriptomic analyses. We found that tumors expressing IDH1 R132Q had increased D2HG levels and larger tumors compared to WT and R132H, but the glioma and chondrosarcoma xenograft tumor models showed highly variable consequences on genome methylation and gene expression, with increased pro-tumorigenic pathways upregulated upon expression of IDH1 R132Q.

Results

D2HG levels in IDH1 R132Q tumor models are higher relative to R132H.

We sought to determine how the degree of D2HG production efficiency tunes phenotype severity in models of mutant IDH1-driven tumors. We have shown previously that R132Q mutant homodimers produce D2HG more efficiently than R132H mutant homodimers20–22, though WT:mutant heterodimers may also be found as IDH1 mutations are found heterozygously in patients. Thus, we first generated 1:1 mixtures of purified WT and mutant IDH1 enzymes to allow heterodimers to form. Then we used steady-state kinetics methods to show that IDH1 R132Q heterodimers are 9.5-fold more efficient at D2HG production versus R132H heterodimers (Supplementary Fig. 1). This was driven both by an increase in kcat and decrease in Km.

Though catalytic parameters speak to the intrinsic properties of enzymes, their translation to the cellular environment is necessarily complicated by metabolic complexities. For example, D2HG levels can be mitigated via D-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (D2HGDH) activity25. As patient-derived IDH1 R132Q-driven tumor cells were unavailable due to the rarity of this mutation in patients, we sought to generate isogenic cell lines stably overexpressing either IDH1 WT, R132H, R132Q, or empty vector. As IDH1 mutations are heterozygous, endogenous IDH1 WT was desired. We selected well-characterized cancer-derived and non-cancer-derived cell lines commonly used to model IDH1 mutations in gliomas and chondrosarcomas: U87MG glioma cells, normal human astrocytes (NHA), C28 chondrocytes, and a modified HT1080 chondrosarcoma line with the endogenous IDH1 R132C mutation removed (this allowed us to maintain IDH1 expression from a single allele) to generate IDH1−/+, here designated as HT1080*. It was within these backgrounds that we generated the stably over-expressing lines. Interestingly, we were unable to generate clones that sustained high expression of IDH1 R132Q (Supplementary Fig. 2). Despite consistently lower expression of IDH1 R132Q relative to R132H, we nonetheless found that D2HG concentrations were significantly higher in this more catalytically active mutant (Fig. 1a) in both cancerous (U87MG, HT1080*) and non-cancerous cell lines (NHA, C28).

Fig. 1. Catalytic efficiency of IDH1 mutants drive D2HG levels in biochemical, cellular, and in vivo models.

a, Empty vector (purple x’s), empty vector (EV, black diamonds), IDH1 WT (orange circles), IDH1 R132H (blue squares), or IDH1 R132Q (green triangles) was stably overexpressed in glioma cells (U87MG), normal human astrocytes (NHA), chondrocytes (C28), and fibrosarcoma cells where an endogenous IDH1 R132C mutation was removed (i.e. HT1080+/−, denoted HT1080*), and cellular D2HG levels were quantified. Mouse xenografts were generated from the cancer-derived b, U87MG and c, HT1080* lines stably overexpressing IDH1 WT, R132H, or R132Q, and tumor volume was measured over time. Significant differences from IDH1 R132Q are indicated with p value stars colored according to the corresponding comparison group (WT in orange, R132H in blue). d, Tumors, and e, sera were harvested from the mice, and D2HG levels were quantified. In all figures, replicates are shown with the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) indicated. P values determined by unpaired t tests (a) or ordinary one-way ANOVA (b-e), with **** p ≤ 0.0001, *** p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05 for pairwise comparisons between IDH1 WT, R132H, and R132Q. In a, significant differences involving parental and empty vector (EV) are not highlighted to improve clarity.

We next sought to understand the consequences of mutants with differing catalytic efficiency in in vivo models of mutant IDH1 tumors. To increase the likelihood of tumor formation, used IDH1 WT-, R132H-, or R132Q-expressing glioma (U87MG) and fibrosarcoma (HT1080*) cells to generate subcutaneous xenografts in immunodeficient mice. For the U87MG series, tumors formed in 100% of the mice (27/27, 9 per group), with no significant differences in days to tumor initiation or tumor density among the IDH1 WT, R132H, or R132Q mutants (Supplementary Fig. 3). However, IDH1 R132Q U87MG tumors had significantly higher volume (Fig. 1b), mass, and growth rate (Supplementary Fig. 3) compared to both IDH1 WT and R132H.

Tumors were formed in 22% (2/9), 30% (3/10), and 78% (7/9) of the IDH1 WT-, R132H-, or R132Q-expressing HT1080* mouse xenografts, respectively. Here, tumor volume was larger (Fig. 1c), and tumor initiation occurred significantly earlier for IDH1 R132Q mutants compared to IDH1 WT and R132H, though tumor mass and tumor density showed no significant differences (Supplementary Fig. 4).

We harvested all available tumors and sera from mice and found that D2HG levels were significantly higher in IDH1 R132Q-expressing U87MG xenografts relative to both IDH1 WT and R132H (Fig. 1d, 1e). These trends were recapitulated in the HT1080* xenografts, though significance was not reached (Fig. 1d, 1e). Expression of IDH1 R132H and WT was higher compared to R132Q as based on Western immunoblot analysis, and this was recapitulated in RNAseq analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 1). There appeared to be no obvious correlation between tumor and serum D2HG concentrations, or between tumor D2HG concentration and tumor mass as a percentage of body mass, though there might be modest correlation in serum D2HG concentration and tumor mass as a percentage of body mass (Supplementary Fig. 5). Together, these in vitro and in vivo models showed that expression of IDH1 R132Q was associated with more catalytically efficient D2HG production, higher cellular, tumor, and serum levels of D2HG, and larger tumors compared to IDH1 R132H.

Epigenomic and transcriptomic features of mutant IDH1 chondrosarcoma xenograft tumor models.

To understand the mechanism(s) behind the differences in tumor size in the IDH1 R132Q versus R132H and WT tumors, we selected a random subset of xenograft tumors for reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) analysis to analyze genome-wide DNA methylation in representative HT1080* and U87MG xenograft tumors. We first performed clustering analysis for the HT1080* tumor xenografts based on the degree of CpG methylation of the most variable probes with the highest standard deviation (S.D.) (S.D. > 0.90, n = 29,593 probes, Fig. 2a). Here, there was modest separation based on genotype, with HT1080* xenografts expressing IDH1 WT having the most notable separation. This is perhaps unsurprising given the wide span in tumor weight as a percent of body weight and low n for WT IDH1-expressing HT1080* tumors (Supplementary Table 1). Better separation among the two mutants was achieved via PCA that included D2HG tumor concentrations (Fig. 2b). When comparing distribution of methylation values for all CpG sites, there was a modest shift in hypermethylation in mutant versus WT IDH1 HT1080* tumor xenografts (Fig. 2c). We then analyzed the methylation levels of CpG sites that correlated with tumor D2HG amounts in HT1080* xenografts and identified the loci that were positively correlated with D2HG (Fig. 2d), including the CpG sites within the RIPK1 promoter (Fig. 2e). Next, we identified the pairwise differentially methylated loci among all three genotypes in HT1080* tumors (methylation difference > 20% and q-value < 0.5). Compared to IDH1 WT samples, IDH1 R132Q induced hypermethylation in a larger number of CpG sites compared to IDH1 R132H (Fig. 2f). In general, both IDH1 R132H and R132Q chondrosarcoma tumor models showed the same hypermethylation localization trends compared to WT, with promoter and intronic regions showing more hypermethylation than intergenic and exonic regions (Fig. 2h). When comparing the two mutants, however, a significant increase in hypomethylation was observed (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Fig 6), with IDH1 R132Q expression leading to hypomethylation enriched in promoter regions and CpG islands (CpGi) compared to R132H HT1080* xenografts (Fig. 2h, Supplementary Fig. 7s).

Fig. 2. IDH1 R132Q-induced methylation remodeling differs from IDH1 R132H in HT1080* tumors.

a, Hierarchical clustering of the most variable CpG sites (standard deviation > 0.90, n = 29,593) in the HT1080* RRBS cohort. b, PCA plot of the most variable CpG sites (standard deviation > 0.90) in the HT1080* RRBS cohort. The size of each dot corresponds to the level of D2HG (nmol tumor) measured in each tumor sample. Colors indicate genotype. c, Global methylation profiles of the HT1080* RRBS tumor cohort showing percent (%) methylation values of CpG sites for each sample. Black vertical lines indicate quantiles, colors indicate genotype. d, Heatmap showing the correlation between D2HG (nmol tumor) and methylation values of the top 1% of the most variable CpG sites. Pearson correlation coefficients (R) are shown on the right of the heatmap. The amount of D2HG in tumors is depicted as a bar plot above the heatmap. e, Representative IGV plot showing CpG sites within the RIPK1 promoter that positively correlate with D2HG amounts (CpG sites are highlighted in gray). f, Number of differentially methylated CpG sites (DMS, % methylation difference ≥ 20 and q-value < 0.05) are shown. Left, IDH1 R132H vs IDH1 WT; middle, IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 WT; right, IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 R132H. hyper, hypermethylated; hypo, hypomethylated. g, Violin plots showing the distribution of percent (%) methylation of hypermethylated loci in IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 WT (top left), hypomethylated loci in IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 WT (top right), hypermethylated loci in IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 R132Q (bottom left), and hypomethylated loci in IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 R132H (bottom right). For clarity, samples not included in the pairwise statistical comparisons are also plotted. h, Distribution of the genomic features for the hyper- and hypo-methylated loci for all comparisons. i-k, Gene ontology enrichment (using GREAT toolbox) of the hypermethylated (hyper) loci in IDH1 R132Q compared to i, IDH1 WT, j, hypomethylated (hypo) loci in IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 R132H, and k, hypermethylated loci in IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 R132H samples.

To compare the expression patterns of genes in the IDH1 WT-, R132H-, and R132Q-driven xenograft tumors, we obtained RNA-seq data for the subset of tumors that also underwent RRBS analysis. Consistent with both mutants being hypermethylated relative to WT, which would predict increased gene silencing, there were more down-regulated than up-regulated genes for R132H and R132Q HT1080* xenograft tumors relative to WT (Supplementary Table 2). Similarly, consistent with an increase in hypomethylation of CpG sites in R132Q versus R123H, which would predict an increase in gene expression, there were more upregulated genes in R132Q than downregulated compared to R132H (Supplementary Table 2). Together, these data suggest that in chondrosarcoma tumor models, expression of IDH1 R132 mutants led to increased hypermethylation compared to WT, while IDH1 R132Q was associated with increased regions of hypomethylation compared to IDH1 R132H.

Pathways significantly hypermethylated and down-regulated in IDH1 R132Q chondrosarcoma xenograft tumor models.

RRBS analysis identified pathways associated with hypermethylation in IDH1 R132Q versus R132H chondrosarcoma models highlighted pathways involved in cell cycle, DNA damage response, and DNA damage checkpoint signal transduction (Fig. 2k), suggesting the DNA damage response is likely downregulated upon expression of IDH1 R132Q compared to R132H. Notably, IDH1 R132Q had a significant increase in methylation 236 bases from mitotic arrest deficient 2-like protein 2 (MAD2L2) relative to R132H. Consistent with a proposed increase in gene silencing due to increased methylation, RNAseq analysis showed expression of MAD2L2 trended lower in IDH1 R132Q-expressing HT1080* tumors compared to R132H (p = 0.028, padj = 0.21). Mitotic arrest deficient 2-like protein 2 (MAD2L2), also known as REV7, plays a role in translesion DNA synthesis and double stranded DNA break repair. As an adapter protein, it promotes the progression of replication of stalled replication forks past lesions through its interaction with REV3, DNA Polymerase δ 2 (POLD2), and POLD3 to form polymerase ζ (polζ) and drive DNA repair pathways26. Loss of MAD2L2 leads to genomic damage as a result of stalled replication forks27. MAD2L2 also plays a role in promoting non-homologous end-joining (NJEJ) to repair damage found at telomeres28. MAD2L2 has been posited to be a tumor suppressor, with its downregulation associated with an increase in proliferation and migration in colorectal cancer and its expression associated with a favorable prognosis29. However, it also may have an oncogenic role in some contexts, with MAD2L2 upregulation associated with decreased migration and proliferation in ovarian cancer models30. Significant hypermethylation was also seen 469 bases from growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible protein γ (GADD45G) and GADD45G in IDH1 R132Q versus R132H HT1080* xenograft tumors, though this gene did not appear in our RNAseq analysis. GADD45G is a tumor suppressor that is involved in a host of cellular processes, including DNA repair31, cell cycle arrest32, and apoptosis33. Notably, its silencing or downregulation has been implicated in AML34 and breast cancer35. GADD45G promotes cell differentiation through negative regulation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT (PI3K/AKT) pathway, and, consequently, its downregulation leads to activation of this pathway to drive cancer36. Methylation of a related gene, GADD45A, has been identified in patients with mutant IDH1 and IDH2-driven AML.

Many pathways showed significant hypermethylation in IDH1 R132Q vs. WT HT1080* xenografts, including pathways involved in altered transcription (chromatin insulator sequence binding, RNA polymerase III transcription factor binding, hypomethylation of CpG island), as well as cell movement (chemotaxis, lamellipodium assembly, axon guidance semaphorin-dependent pathways) (Fig. 2i). Indeed, RNAseq analysis of the HT1080* xenografts showed a significant decrease in transcripts associated with external encapsulating structure and axon initial segment pathways upon expression of IDH1 R132Q versus WT (Supplementary Fig. 8). Transcripts associated with morphogenesis and differentiation were also hypermethylated in IDH1 R132Q relative to WT, including significant hypermethylation 140–649 bases from Wnt pathway members, including Wnt family member 9A (WNT9A) and 10A (WNT10A), frizzled-9 (FZD9), palmitoleoyl-protein carboxylesterase (NOTUM), T-cell specific transcription factor 7 (TCF7), and NKD1 (Wnt signaling alterations also resulted from hypomethylation in R132Q tumors, vide infra). Indeed, RNAseq analysis showed that WNT9A was significantly down-regulated in IDH1 R132Q versus WT HT1080* xenografts, with FZD9 and TCF7 transcripts trending down but not achieving significance when adjusted for multiple comparisons (Supplementary Table 3).

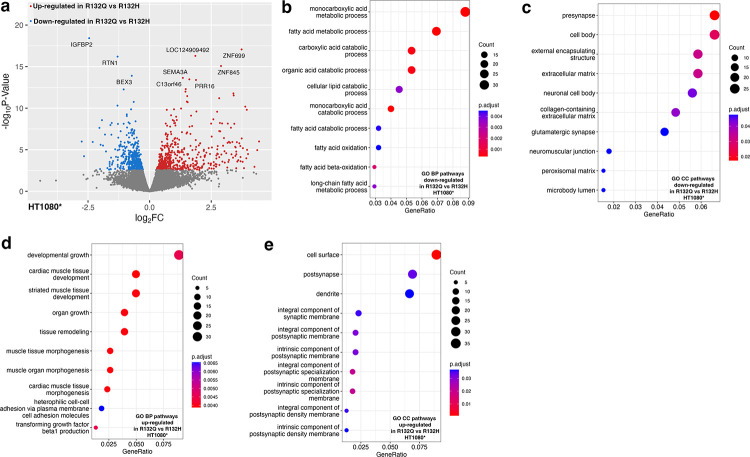

Transcripts involved in collagen/extracellular matrix (ECM) pathways were also downregulated upon R132Q expression compared to both R132H and WT HT1080* xenografts (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 8). This included a decrease in transcripts of COL9A2 upon expression of R132Q versus WT, a type IX collagen that has been shown to be downregulated in high-grade versus low-grade chondrosarcomas37 (Supplementary Table 3). Annexin-A6 (ANXA6) transcripts were also downregulated in R132Q compared to both R132H and WT chondrosarcoma models (Supplementary Table 3). ANXA6 is a membrane-bound protein that mediates cholesterol transport and homeostasis, and facilitates interactions of the membrane with actin during endocytosis and exocytosis38. Notably, it is a tumor suppressor due to its ability two negatively regulate EGFR phosphorylation39, and supportive of a lift of a negative regulator, EGFR transcripts were higher in R132Q versus R132H and WT HT1080* xenografts (Supplementary Table 3). Pathways related to lipid catabolism/oxidation were also shown to be downregulated in IDH1 R132Q versus R132H (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 8), suggesting that the use of lipids as a fuel source is more critical in R132H than R132Q; indeed, β-oxidation has been shown to be an important adaptive mechanism in IDH1 R132H tumor models40. RNAseq analysis also highlighted a decrease in transcripts associated cell surface projections (cell body) in IDH1 R132Q versus R132H HT1080* xenografts. These pathways were highlighted as being upregulated in R132H compared to WT (Supplementary Fig. 9), indicating an important feature for IDH1 R132H. Thus, compared to IDH1 R132H, IDH1 R132Q-expressing chondrosarcoma tumor models experienced significant changes in pathways involving DNA damage, Wnt and EGFR signaling, and collagen/ECM remodeling that was facilitated by altered CpG methylation and non-CpG-methylation pathways.

Fig. 3. Transcriptome analysis using RNAseq of HT1080* xenograft tumors comparing IDH1 R132Q and IDH1 R132H.

Down-regulated pathways refer to categories where the majority of genes show decreased expression levels in R132Q versus R132H IDH1. Up-regulated pathways refer to categories where the majority of genes show increased expression levels in R132Q versus R132H IDH1. Number of genes are indicated in the count, with the padjusted value indicated by color. a, Volcano plot of differentially expressed transcripts comparing expression of IDH1 R132Q versus IDH1 R132H. b, Biological pathways (BP) down-regulated in IDH1 R132Q versus IDH1 R132H. c, Cellular component (CC) pathways down-regulated in IDH1 R132Q versus IDH1 R132H. d, Biological pathways (BP) up-regulated in IDH1 R132Q versus IDH1 R132H. e, Cellular component (CC) pathways up-regulated in IDH1 R132Q versus IDH1 R132H.

Pathways significantly hypomethylated and up-regulated in IDH1 R132Q chondrosarcoma xenograft tumor models.

As hypomethylated CpG regions appeared to be an important difference between R132Q and R132H HT1080* xenografts, we also assessed the pathways affected by decreased methylation, and thus likely upregulated. Pathways predicted to be hypomethylated in IDH1 R132Q versus R132H chondrosarcoma models involved p38 MAPK, which helps regulate cell differentiation, growth, and death41, RNA pol II transcription cofactor binding, which can help drive or halt transcription, non-canonical Wnt signaling that can drive proliferation and migration in cancer42, vesicle trafficking, and fatty acid and organelle transport pathways (Fig. 2j). Similarly, GO pathways upregulated based on increased transcripts in IDH1 R132Q versus R132H HT1080* xenografts included pathways associated with growth, remodeling, morphogenesis, and transcription repression were upregulated (Fig. 3), but in general there was minimal overlap of genes significantly hypomethylated with elevated transcripts. A region < 70 bases from MRAS was shown to be hypomethylated in R132Q HT1080* xenografts compared to R132H, though this did not translate to a significant increase in MRAS transcripts in R132Q tumors. To better understand consequences of a less methylated genome in IDH1 R132Q than R132H, we also compared pathways associated hypomethylation/increased transcripts in IDH1 R132Q compared to WT. Here we observed a predicted activation due to hypomethylation of pathways including vesicle loading of neurotransmitters, and indeed RNAseq analysis highlighted an increase in pathways associated with endocytic vesicles, and neuronal projection and axon development/guidance (Supplementary Fig. 8)

RNAseq analysis showed many cancer pathways upregulated in R132Q HT1080* xenografts versus R132H outside of genes identified in RRBS analysis, including proto-oncogenes c-myc (MYC), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor c (VEGFC), ras-like proto-oncogene A (RALA), casitas B-lineage lymphoma E3 ubiquitin ligase (CBL), and ETS proto-oncogene 1 (ETS1) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs. 8, 9). Importantly, activation of c-myc via the Wnt pathway can stimulate the cell cycle in part by activating expression or stimulating the accumulation of cyclin dependent kinase 6 (CDK6) and cell-cycle regular cyclin D2 (CCND2) in early G1 phase to promote transition to S phase to support proliferation43–45. C-myc, CDK6, and CCND2 transcripts were all significantly higher in R132Q HT1080* xenografts versus R132H (Supplementary Table 3). Though changes in p53 (TP53) transcripts did not reach significance, tumor protein p53 inducible protein 3 (TP53I3) transcripts, which is induced by p53 and serves as a marker for pro-apoptosis46, were significantly lower in R132Q HT1080* xenografts than R132H (Supplementary Table 3). Indeed, transcripts of caspase-9 (CAS9), which drives apoptosis47, were marginally significantly lowered in R132Q HT1080* xenografts compared to R132H with a p < 0.05 before correcting for multiple comparisons (Supplementary Table 3). Together, these data suggest that IDH1 R132Q-expressing chondrosarcoma models relied on upregulation of intra- and extra-cellular communication driven at least in part through CpG hypomethylation, as well as increased expression of oncogenes such as MYC and EGFR and altered regulation of the Wnt pathway in mechanisms likely independent of altered DNA methylation.

Epigenomic and transcriptomic features of mutant IDH1 glioma xenograft tumor models.

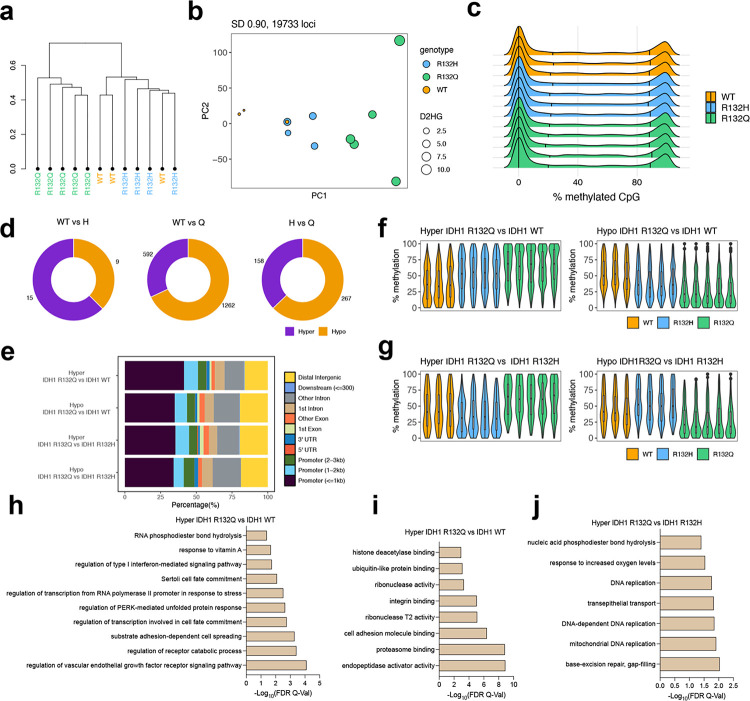

U87MG xenografts, which had more power due to more tumors forming, showed distinct clustering for IDH1 R132Q xenografts based on the most variable CpG methylation sites (S.D. > 0.90), with some clustering seen for IDH1 WT and R132H tumors (Fig. 4a). PCA that included D2HG levels showed better separation for the U87MG xenografts than HT1080* (Fig. 4b). Surprisingly, there was no observed increase in hypermethylation for all probes among the mutants compared to WT (Fig. 4c). Notably, in U87MG xenografts, there were fewer CpG sites that were differentially methylated in the IDH1 mutants compared to WT tumors. Therefore, we filtered the RRBS data and restricted our differential methylation analyses to variable CpG sites (n = 42,310, % methylation difference ≥ 10% and q-value < 0.05). In IDH1 R132Q-expressing U87MG tumor xenografts, a large percentage of the differentially methylated sites were hypomethylated (n = 1,262) compared to both IDH1 WT and R132H (Fig. 4d, 4f). Trends in location of hypermethylation and hypomethylation in the glioma models were similar to chondrosarcoma models, with most alterations occurring near promoter regions followed by distal intergenic and other intron regions (Fig. 4e). Compared to HT1080* xenografts, U87MG xenografts had more hypomethylation and hypermethylation in regions outside the CpG islands and shores in addition to the CpG islands (Supplementary Fig. 7). Expression of IDH1 R132H had the majority of hypermethylation in these other sites compared to IDH1 WT U87MG xenografts.

Fig. 4. IDH1 mutants exhibit a subtler influence on the methylomes of U87MG tumors.

a, Hierarchical clustering of the most variable CpG sites (standard deviation > 0.90, n = 19,733) within the U87MG RRBS cohort. b, PCA plot of the most variable CpG sites (standard deviation > 0.90) within the U87MG RRBS cohort. The size of each dot corresponds to the level of D2HG (nmol tumor) measured in each tumor sample. Colors indicate genotype. c, Global methylation profiles of the U87MG RRBS tumor cohort showing percent methylation values of CpG sites for each sample. Black vertical lines indicate quantiles, colors indicate genotype. d, Number of differentially methylated CpG sites (DMS, % methylation difference ≥ 10 and q-value < 0.05) are shown. Of note, RRBS data is filtered to include variable loci (standard deviation > 10, n = 42,310) prior to differential methylation analysis. e, Distribution of the genomic features for the hyper- and hypo-methylated loci for all comparisons. f, Violin plots showing the distribution of percent (%) methylation of hypermethylated loci in IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 WT (top left), hypomethylated loci in IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 WT (top right), hypermethylated loci in IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 R132Q (bottom left), and hypomethylated loci in IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 R132H (bottom right). For clarity, samples not included in the pairwise statistical comparisons are also shown. g-i, Gene ontology enrichment (using GREAT toolbox) showing enriched biological processes in hypermethylated (hyper) loci in IDH1 R132Q compared to IDH1 WT (h), molecular function in IDH1 R132Q vs IDH1 R132H, and biological processes in hypermethylated loci in IDH1 R132Q compared to IDH1 R132H (i).

Pathways significantly hypermethylated and down-regulated in IDH1 R132Q glioma xenograft tumor models.

RRBS analysis highlighted regions associated with nucleic acid phosphodiester bond hydrolysis, DNA replication, and DNA repair were hypermethylated in R132Q U87MG tumor xenografts versus R132H (Fig. 4i), reminiscent of DNA damage pathways hypermethylated in R132Q HT1080* tumors (Fig. 2k). This suggests that silencing DNA damage repair seems to be an important strategy in both IDH1 R132Q-expressing tumor models. When comparing IDH1 R132Q glioma xenografts with WT, pathways associated with cell adhesion, integrin binding, cell spreading, protein folding stress, protein degradation, transcription regulation stress responses, and VEGFR signaling were highlighted as being hypermethylated (Fig. 4g, 4h). Integrins mediate cell adhesion, and their altered regulation can have an impact on cell growth, migration, differentiation, adhesion, and apoptosis, and their hypermethylation has been implicated in tumors48. RNAseq analysis showed that no pathways emerged as being significantly downregulated in IDH1 R132Q U87MG xenografts compared to R132H, though compared to WT, many similarities in downregulated pathways emerged for both mutants. Both showed a significant downregulation of transcripts in pathways associated with chemotaxis, ECM organization, angiogenesis, negative regulation of cell migration, and small molecule metabolism (Fig. 5, Supplementary Figs. 10, 11). Together, these data suggest that expression of both IDH1 mutants in glioma xenograft models share many transcriptionally down-regulated pathways, though IDH1 R132Q uniquely shows hypermethylation of DNA damage pathways.

Fig. 5. Transcriptome analysis using RNAseq of U87MG xenograft tumors comparing IDH1 R132Q and IDH1 R132H.

Down-regulated pathways refer to categories where the majority of genes show decreased expression levels in R132Q versus R132H IDH1. Up-regulated pathways refer to categories where the majority of genes show increased expression levels in R132Q versus R132H IDH1. Number of genes are indicated in the count, with the padjusted value indicated by color. a, Volcano plot of differentially expressed transcripts comparing expression of IDH1 R132Q versus IDH1 R132H. b, Biological pathways (BP) up-regulated in IDH1 R132Q versus IDH1 R132H. c, Cellular component (CC) pathways up-regulated in IDH1 R132Q versus IDH1 R132H. d, Molecular function (MF) pathways up-regulated in IDH1 R132Q versus IDH1 R132H.

Pathways significantly hypomethylated and up-regulated in IDH1 R132Q glioma xenograft tumor models.

There were many upregulated pathways that may have helped drive the larger, earlier-forming tumors observed in IDH1 R132Q U87MG xenografts compared to R132H, including cell migration, motility, cell signaling pathways. A comparison of upregulated pathways in IDH1 R132Q versus WT U87MG xenografts recapitulated this reliance on these pathways, with transcripts of genes related to cell migration, motility and negative regulation of differentiation again upregulated (Supplementary Fig. 10). The PI3K-AKT pathway emerged as a critical driver of these pro-tumorigenic features; PI3K-AKT signaling via upregulation of EGFR, interleukin 6 (IL6), and janus kinase 1 (JAK1), were all significantly upregulated in IDH1 R132Q U87MG xenograft tumors versus R132H (Supplementary Table 4). Previously, the PI3K-AKT pathway has been shown to be downregulated in R132H-driven tumors and tumor models49,50 and it was suggested that D2HG production inhibited AKT phosphorylation, though our data suggests a different mechanism may be at play. Notably, our RNAseq analysis also showed evidence of JAK-STAT pathway activation in IDH1 R132Q-expressing glioma models; EGFR and IL6 transcripts were both significantly elevated upon R132Q expression and appeared to contribute to JAK1 activation with increased transcripts of this kinase, followed by a nonsignificant trend of increased STAT3 transcripts, with a p = 0.005 before correcting for multiple comparisons (Supplementary Table 4).

The PI3K/AKT pathway, through activation of growth factor receptors like EGFR and integrins, can also activate mouse double minute 2 E3 ubiquitin ligase (MDM2), which in turn can degrade p5351. Notably, IDH1 R132Q-expressing U87MG tumor xenografts had significantly increased transcripts of many elevated integrin family members, EGFR, and MDM2 (Supplementary Table 4) compared to R132H. When comparing R132Q to WT, all transcripts except MDM2 were also significantly increased (MDM2 transcripts trended upwards, though significance was not reached), and both TP53 and TP53I3 transcripts were significantly decreased (Supplementary Table 4).

Notably, transcripts of n-Ras (NRAS) were shown to be significantly upregulated in IDH1 R132Q-expressing U87MG xenografts compared to WT, which was not observed in a comparison of R132H vs WT (Supplementary Table 4). Transcripts of transforming growth factor β−1 (TGFB1) and transforming growth factor α (TGFA), downstream targets of n-Ras, were also uniquely upregulated upon expression of R132Q compared to WT (Supplementary Fig. 10, Supplementary Table 4), indicating activation of important tumor driving pathways that can drive cancer growth and metastasis52. Many of these oncogenes are also implicated in focal adhesion, a pathway that helps regulate cell grown, migration, and ECM remodeling. Specifically, c-Jun (JUN), Rho associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase 2 (ROCK2), EGFR, integrins, and collagens transcripts were all significantly upregulated upon IDH1 R132Q expression compared to WT in U87MG xenografts (Supplementary Table 4). Importantly, a comparison of R132H versus WT instead highlighted pathways associated with ECM reorganization as being upregulated, with no significant changes in the key oncogenes IDH1 R132Q appears to rely heavily upon (Supplementary Fig. 11, Supplementary Table 4).

Together, these data highlight likely a non-methylation-based reliance of IDH1 R132Q-expressing U87MG xenografts on the activation of PI3K/AKT, EGFR, and Ras pathways and deactivation of p53 to lead to increased cell growth and migration.

Discussion

We showed that hypermethylation and hypomethylation changes in both tumor models favored near promoter regions, followed by distal intergenic and other intronic sites, with typically all chromosomes affected. We also showed a bias of hypermethylation and hypomethylation in CpG islands and other sites, with shores having the least methylation changes in all pair-wise comparisons. These results were typical of previous findings, with most notable differences reported being in CpG islands, with IDH1-mutated gliomas having a notable increase in methylation in this region, in addition to more overall methylation53. Previous analysis with R132H-driven cell lines also showed hypermethylation with wide distribution with a bias towards CpG islands and shores, and hypomethylation occurring more at CpG island edges54. AML patients with IDH1 or IDH2 mutations had hypermethylated promoter and CpG islands55.

Both increased hypermethylation and hypomethylation are well-documented in cell and xenograft models of R132H IDH1-mutated tumors, as well as patient-derived tumor tissue3,9,53–60. The mechanisms and consequences of increased hypomethylation in mutant IDH1 tumors and tumor models are still not understood53,54,56,57. Our observed significant increase in hypomethylation in IDH1 R132Q HT1080* tumors compared to R132H and the subsequent increase in expression of many pro-tumorigenic genes indicate more study on the role of hypomethylation is warranted. We found that correlation between DNA methylation and gene expression was relatively poor, and others have reported the same finding, citing that locations that acquire hypermethylation may often affect regions that already are transcriptionally less active54. Of course, changes in D2HG-driven histone methylation as well as indirect changes in protein activation via phosphorylation will also affect the transcriptome4. Our limited power in the WT IDH1 HT1080* tumors due to lack of tumor formation in 7/9 biological replicates also likely complicated analysis, as one of the WT tumors was unusually large (Supplementary Table 1).

CpG hypermethylation was much more impactful in mutant IDH1-expressing chondrosarcoma xenograft models than glioma xenograft models. The decreased methylation in mutant IDH1 U87MG xenografts compared to WT was surprising. A possible reason for this is due to the low passage number in the U87MG cells; after successfully introducing the mutations, the U87MG cells were injected into mice at a passage number range of 6–12, while HT1080* lines were used at passage 21. We9 and others61 have shown that the degree of methylation changes over time, with high passage number associated with increased hypermethylation. However, deletion of IDH1 mutations have been reported both in vitro and in vivo58, and indeed, further expansion of our U87MG line, but not our HT1080*, led to the loss of expression of the R132Q mutation as determined by anti-HA-tag immunoblotting and by the absence of the D2HG metabolite in GC-MS analysis. To ensure that IDH1 R132Q was still expressed and to allow head-to-head comparisons of U87MG cells at similar passage number, xenograft injections occurred at this lower passage despite suboptimal conditions for RRBS analysis. Despite this challenge, a trend unique to IDH1 R132Q emerged in both chondrosarcoma and glioma xenografts – hypermethylation of pathways associated with DNA damage. There is support that hypermethylation of DNA damage pathways is unique to the IDH1 R132Q mutant; H3 histone hypermethylation studies with in vivo IDH1 R132H-expressing tumor models have suggested up-regulation of DNA damage response, cell cycle control, and cell development regulation pathways, with increased transcripts for ATM, BRCA1, FANCD2, RAD5162. The HT1080* xenografts also highlight hypermethylation of DNA damage and G1 checkpoint signaling, suggesting that IDH1 R132Q may help confer protection from cell cycle arrest.

In addition to hypermethylation of DNA damage, additional pathways appeared important to both chondrosarcoma and glioma xenograft models. Transcripts of EGFR were uniquely elevated upon IDH1 R132Q expression. This elevation of EGFR was surprising, as gliomas with both EGFR amplification and R132H IDH1 mutations are reported as less common 63,64 or even mutually exclusive65, and we had assumed this might extend to other IDH1 mutants as well. Specifically, IDH1 R132H expression is often associated with downregulation of MAPK, PI3K/mTOR, and EGFR pathways compared to h-Ras/non-mutant-IDH1-driven glioblastoma models4. We have shown previously that Ras, EGFR, and PI3K pathways were associated with hypermethylation in astrocytes expressing mutant IDH1 compared to WT9. Interestingly, others have shown that gene copy numbers calculated from methylation profiling studies indicated that a small population of rapidly progressing mutant IDH1-driven astrocytomas had different profiles than the more common slower-progressing mutant-IDH1-driven tumors66. Specifically, this included increased copy numbers in EGFR, MYC, MET, CDK6, and CDKN2A/B in the patients tested66. Importantly, we found that transcripts of EGFR, MYC, and CDK6 were significantly upregulated upon IDH1 R132Q expression in chondrosarcoma xenografts compared to R132H and/or WT, while these genes were not upregulated when comparing IDH1 R132H versus WT. Similarly, we observed significantly increased transcripts of EGFR and MET upon IDH1 R132Q expression in glioma xenografts compared to R132H and/or WT, with an increase in CDK6 nearly achieving significance, while these genes were not significantly affected in IDH1 R132H compared to WT (Supplementary Tables 3, 4). CDKN2A/B were not identified in either series. Thus, this suggests that IDH1 R132Q confers features reminiscent of more aggressive, typically non-IDH1-driven tumors through mechanisms not likely directly involving CpG hypermethylation.

Altered Wnt signaling can ultimately result in dysregulation of differentiation and morphogenesis to help drive tumor progression42,67–70. Hypermethylation and/or down-regulation of Wnt signaling modulators and pathway members to result in aberrant Wnt signaling has been reported as a consequence of IDH1 R132H expression by us9 and others54,71–73. Hypermethylation of Wnt signaling in general has been implicated in a variety of cancers68,74, including hypermethylation of WNT9A and FZD9 genes67,75. WNT9A has tumor suppressor features in that it drives the differentiation of chondrocytes69 and can inhibit cell proliferation70. We found here that alterations in the Wnt pathway represented another persistent phenotype in our xenograft models, with primarily hypermethylation (and some hypomethylation) of gene pathway members upon expression of IDH1 R132Q in chondrosarcoma models. Notably, transcripts of many Wnt pathway members were significantly up- and down-regulated upon IDH1 R132Q expression in both xenograft models (Supplementary Tables 3, 4), suggesting that non-epigenetic changes may also alter the regulation of this pathway.

We were unsurprised to find unique methylation and transcription patterns when comparing HT1080* versus U87MG xenografts, as variation of both have been widely reported in both tumor and tumor models of mutant IDH1-driven cancers. The HT1080* cells originated from an IDH1R132C/+ background, and likely had some epigenetic changes prior to deletion of the IDH1 R132C allele. These modified HT1080* cells thus also have only half the endogenous WT allele amount compared to U87MG cells, and there have been differences reported between hemizygous and heterozygous features of tumor models76. The preference for the IDH1 R132C mutation in chondrosarcoma versus IDH1 R132H in glioma tumors also highlight a possible preference of D2HG levels in among tumor types, with perhaps glioma cells being more susceptible to the toxicity of D2HG and thus preferring the low D2HG levels associated with IDH1 R132H, as we have shown that IDH1 R132C is slightly more catalytically efficient at driving the neomorphic reaction20. There is some debate about which mutant IDH-driven tumor type is associated with more hypermethylation. Some have shown that IDH-driven gliomas have more hypermethylation than AML, melanomas, and cholangiocarcinomas (chondrosarcomas were not assessed due to not being available in TCGA)53, while others have cited AML as having the highest methylation56. Others have reported differences in preferred CpG methylation sites among glioma patients.61 It has been shown previously that heterozygous knock-in models (HCT116R132H/+) had similar loci methylated than cell lines stably over-expressing R132H (HOG)54. Further evidence of variation among tumors include the finding that tumors clustered more based on their tissue of origin than top methylated probe bias56. Understanding the unique DNA and histone methylation features among different tumor tissue and among different IDH1 and IDH2 mutants remain important areas of research.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents.

β-Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced trisodium salt (NADPH), β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate disodium salt (NADP+) tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) (TCEP), agarose, L-norvaline, and 100 kD Amicon centrifugal filters were purchased from Millipore Sigma (Burlington, MA). Triton X-100, magnesium chloride (MgCl2), α-ketoglutaric acid sodium salt (αKG), DL-isocitric acid trisodium salt hydrate, dithiothreitol (DTT), isopropyl 1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG), Pierce protease inhibitor tablets, chloroform, isopropanol, PEI STAR transfection reagent, chloroquine diphosphate, T-PER Tissue Protein Extraction Reagent, β-tubulin polyclonal antibody, Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate, and H3K9me3 polyclonal antibody were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Β-mercaptoethanol (BME) was bought from MP Biomedicals (Santa Ana, CA). Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin was obtained from Qiagen (Valencia, CA), and stain-free gels (4–12%) were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). High glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (PSG) 100X, L-glutamine, and TrypLE express enzyme were purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, NY). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was obtained from Cytiva (Marlborough, MA). Matrigel was purchased from Corning (Corning, NY). Recombinant anti-HA-tag and anti-γ-H2A.X antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Waltham, MA). Pre-cast 4–20% gels, polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes, Precision Plus Protein Dual Color Standards ladder, and 4X Laemmli sample buffer were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). MEGAPREP 3 kit was purchased from Bioland Scientific (Paramount, CA). Goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) HRP was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). GentleMACS M Tubes were purchased from Miltenyi Biotec (San Diego, CA).

Protein expression, and purification.

Human IDH1 WT, R132H, and R132Q cDNA constructs a pET-28b(+) plasmid were transformed in E. coli BL21 Gold DE3 cells. After incubation in 0.5–1 liters of terrific broth containing 30 μg/mL of kanamycin (37°C, 200, rpm), induction began with 1 mM IPTG (final concentration) after briefly cooling cultures to 25 °C. after reaching an A600 of 0.9–1.2. After 18 h incubation (19 °C, 130 rpm), cell pellets were harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5 at 4°C, 500 mM NaCl, 0.1% NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 1 protease inhibitor tablet) for cell lysis via sonication. Crude lysates were clarified via centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 1h. The resulting lysate was loaded on to a pre-equilibrated Ni-NTA column, followed by 150 mL of wash buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5 at 4 °C, 500 mM NaCl, 15 mM imidazole, 5 mM BME). Protein was then eluted with elution buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5 at 4°C, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol, 10 mM BME). Protein was concentrated if needed and dialyzed overnight in 50 mM Tris pH 7.5 @ 4°C, 100 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol, and 1 mM DTT. > 95% purity was ensured via SDS-PAGE analysis, and IDH1 was flash frozen using liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. All kinetic analysis was performed < 1 month from cell pelleting.

Enzyme kinetic analysis.

An Agilent Cary UV/Vis 3500 spectrophotometer (Santa Clara, CA) was used to perform steady-state kinetic assays at 37 °C. To allow heterodimers to form, a 1:1 mixture (200 nM final concentration of both WT and mutant IDH1) was incubated on ice for 1 h after gentle mixing. However, we note that a mixture of homodimers and heterodimers, depending on their binding equilibria, may exist. To measure the conventional reaction (conversion of ICT to αKG), a cuvette containing IDH1 assay buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5 at 37 °C, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT), and the mixture of WT and mutant (R132H or R132Q) IDH1 (200 nM) were preincubated for 3 min at 37 °C. NADP+ (200 μM) and varying concentrations of ICT were added to initiate the reactions and the change in absorbance due to NADPH formation was monitored at 340 nm. The same conditions were used for the neomorphic reaction (conversion of αKG to D2HG) except NADPH and αKG were used to initiate the reaction and the consumption of NADPH was monitored. The pH of αKG was adjusted to 7.0 prior to use. The slope of the linear range of the change in absorbance over time was calculated and converted to nanomolar NADPH using the molar extinction coefficient for NADPH of 6.22 cm−1 mM−1 to determine kobs (i.e. nM NADPH/nM enzyme s−1) at each substrate concentration. Each kobs was fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) to calculate kcat and Km. In all cases, two biological replicates (2 protein preparations) were used to measure kobs over multiple days, ensuring both preparations were tested at the full range of concentrations of substrate to ensure batch-to-batch reproducibility. Kinetic parameters are reported as standard error (S.E.) resulting from deviation from the mathematical fit of the equation.

Cell line generation and culturing.

LEIH-IDH1-R132H, LEIH-IDH1-WT, and LEIH-IDH1-EV plasmids conferring hygromycin resistance and containing a C-terminal HA-tag were obtained from William Kaelin Jr. (Dana Farber Cancer Institute). The LEIH vector has an EF1a promoter for high expression. We used site-directed mutagenesis to introduce the R132Q mutation by removing the IDH1 WT insert from the LEIH vector, inserting this into a pET17b vector and performing mutagenesis using a KAPA HiFi Hot Start Ready Mix PCR kit (Roch, Boston, MA) using the following mutagenesis primers: forward -- 5’-CTGTATTGATCCCCATAAGCATGCTGACCTATGATGATAGGTTTTACC; reverse – 5’-GGTAAAACCTATCATCATAGGTCAGCATGCTTATGGGGATCAATACAG. The IDH1 insert was then returned to the LEIH vector. All LEIH plasmids confer kanamycin resistance in bacteria and were amplified in DH5α (Thermo Scientific, Fisher Waltham, MA). Plasmids were purified using MEGAPREP 3 (Bioland Scientific, Paramount, CA). Plasmid whole genome sequencing was performed by Retrogen Inc. (San Diego, CA). The hygromycin-resistant genes linked to IDH1 via the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) allow its continuous growth in a low concentration of hygromycin, which was supplemented to the media at the selection dose of 100 μg/mL (final concentration). Only cells that survived were selected, and fresh media was added to flasks with a concentration of 60 μg/mL hygromycin to prevent silencing of the mutation over time. Lentiviral particles were produced in HEK293T Lenti-X cells (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Cells (5×106) were seeded in a 15 cm culture flask and allowed to reach ~70% confluency. LEIH vectors of interest were co-transfected with the lentiviral packaging, envelope, and infection system plasmids pVSVG, pRev, and pGal/Pol (Addgene, Watertown, MA). The transfected cells were incubated for 16 h, and the media was collected and passed through a 45 μM vacuum filter (Corning, Corning, NY). To concentrate the viral particles, centrifugation of the sample in a 100kD Amicon centrifugal filter was used (Sigma Aldrich St. Louis and Burlington, MA), and the viral particles were stored at −80 °C.

U87MG cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). HT1080 cells, which contain an endogenous R132C mutation (IDH1R132C/+) were modified by Kun-Liang Guan (University of California, San Diego) to knock-out the mutant allele to generate (IDH1−/+)77, here notated as HT1080*, which were then provided to us. Normal human astrocytes (NHA) were obtained from Russ Pieper (University of California, San Francisco), and C28 cells were obtained from Johnathan Trent (University of Miami). Routine mycoplasma testing (PCR mycoplasma detection kit, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) was performed as infrequently as every 6 months and as frequently as monthly. Cells stably over-expressing IDH1 WT, R132H, or R132Q were prepared in each of these four cell lines by culturing cells in T75 flasks and allowing them to reach ~60% confluency in DMEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% FBS. Subsequently, the media was replaced with fresh DMEM, and 20 μL of a fresh aliquot of LEIH virus was added directly to the flasks. After 72 h past transfection, media was replaced with DMEM containing 10% FBS and 60 μg/mL hygromycin for cell selection. To assess the success of transfection, we extracted the total protein from the mutant cells and conducted western immunoblotting using a recombinant anti-HA tag antibody (Abcam, Waltham, MA).

For routine culturing, the U87MG, HT1080*, NHA, and C28 cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) containing 10% FBS (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA) and hygromycin at 60 μg/mL (final concentration). HT1080 and U87MG cells were seeded in the concentration of 2×105 of U87MG in a T75 flask. Cells were allowed to reach ~60% confluency before splitting, with fresh media was added every 48 h.

Ethics Statement.

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the San Diego State University (SDSU) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol approval number 22–06-007s).

Animals.

Female athymic nude mice (6–8 weeks old) were purchased from Jackson Labs (Glasgow, Scotland). Female mice were selected based on previously reported protocols for mutant IDH1 xenograft generation78. Mice underwent a mandatory period of 1-week acclimatization at the SDSU Animal Facility. The animals were housed in individually ventilated cages (ABSL2) with a maximum of 4 mice per cage. The mice housing environment was maintained throughout the study with a temperature range of 22 to 25°C, humidity between 40 to 60%, and a light cycle of 12 hours of light and 12 hours of darkness. Cages, bedding, water, and food were individually irradiated for sterility. Animal procedures and maintenance were carried out in accordance with SDSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Xenograft generation and analysis.

For xenografts, 2×106 U87MG IDH1-WT, IDH1-R132H, or IDH1-R132Q cells suspended in Matrigel (354263 Corning, Corning, NY) and PBS (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) (1:1) or 2 × 106 HT1080* IDH1-WT, IDH1-R132H, or IDH1-R132Q cells suspended in PBS were implanted subcutaneously into the left flanks of 6–8-week-old female athymic Nu/Nu mice (Jackson Laboratory). Based on previous work on generating xenografts with HT1080 cells79,80, Matrigel was not used for the HT1080* cells. Vehicle controls (1:1 Matrigel/PBS or PBS alone) were injected subcutaneously into the corresponding right flanks. Twice weekly, mice were weighed, and tumor volume was measured with a Vernier caliper and calculated using the following equation: Tumor Volume (mm3) = ½ length2 (long axis) × width (short axis). Mice were sacrificed once tumors reached 20 mm in length or 120 days of growth. Blood was collected in BD microtainer SST tubes (BD Franklin Lakes, NJ) and processed according to manufacturer’s protocol. Tumors were weighed. Serum and tumor tissue were flash-frozen for downstream analysis.

Western immunoblotting.

Using a Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Protein expression levels were determined by western blot analysis using the following primary antibodies: anti-HA-tag (1:5000) and β-tubulin (1:5000). Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) HRP (1:5000) and anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked Antibody (1:5000).

Protein was extracted from tumor tissue by combining 100–200 mg of tumor tissue with 500 μL of T-PER in gentleMACS M tubes, and samples were dissociated mechanically using a gentle MACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA). All tubes were incubated on ice for 15 min post-tissue homogenization. After incubation, samples were transferred to autoclaved 1.7 mL microtubes and clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was then transferred to fresh 1.7 mL microtubes and stored at −20 °C. Protein was extracted from cell lines by culturing cells in T75 flasks and allowed them to reach ~60% confluency in DMEM + 10% FBS. Cells were washed twice with PBS and detached from the flask using TrypLE Express enzyme. The enzyme activity was neutralized using complete media (1:1). Cells were transferred to 15 mL conical and clarified using centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 10 min, after which the supernatant was discarded. Homemade RIPA buffer (200 μL of 10 mM Tris pH 8.0, 140 nM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) treated with a Pierce Protease Inhibitor Mini Tablet was added to the cell pellet supplemented and incubated on ice for 15 min. The cell lysates were then transferred to an autoclaved 1.7 mL microtube and clarified by centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 20 min. All cell line protein samples were stored at −20 °C.

In all cases, protein samples were normalized to 100 μg/mL and were mixed with 4x Laemmli Sample Buffer and incubated at 95 °C for 10 min. Protein samples were loaded to 4–20% precast gel for sample separation at 120 V for 60 min. Protein samples were transferred to PVDF membrane using a Trans-Blot Turb Transfer System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) for 7 min at 1.0 A, 25V. Membranes were blocked for 3 h in 5% skim milk in 0.1% PBST, followed by the addition of primary antibodies in fresh 5% skim milk in 0.1% PBST. Membranes were incubated with agitation at 4 °C overnight. Following 3× washing for 10 min each in PBS, the membranes were treated with fresh 5% skim milk in 0.1% PBST with secondary antibody and incubated for 3 h. Following 3× washing for 10 min each in PBS, membranes were treated with Clarity Western ECL substrate for imaging on a ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Metabolite analysis by mass spectrometry.

U87MG, HT1080*, C28, and NHA cells were allowed to reach ~60% confluency in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After washing the cells three times with cold PBS, 0.45 mL of 20 μM L-norvaline in 50% methanol (50% v/v in water) was added to serve as an internal standard. Flasks were incubated on dry ice for 30 min and then thawed on ice for 10 min. Cells were lifted from the flask using a cell scraper, transferred to an eppendorf tube, and shipped in dry ice to Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute Protein Production and Analysis Facility to perform metabolite measurements. Dried methanol extracts were first derivatized by adding 50 μl 20 mg/mL methoxyamine-hydrochloride prepared in dry pyridine (Sigma Aldrich St. Louis and Burlington, MA) and incubation for 20 min at 80 °C. After cooling, 50 μL N-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-N-methyltrifluoroacetamide (Sigma Aldrich St. Louis and Burlington, MA) was added, and samples were re-incubated for 60 min at 80 °C before centrifugation for 5 min at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to an autosampler vial for gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis. A Thermo TSQ 9610 GC-MS/MS (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) with an injection temperature of 250 °C, injection split ratio 1/10, and injection volume 0.5 μL was used. GC oven temperature started at 130 °C for 4 min, rising to 243 °C at 6 °C/min and to 280 °C at 60 °C/min with a final hold at this temperature for 2 min. The GC flow rate with helium carrier gas was 50 cm/s, and a GC 15 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm SHRXI-5ms column was used (Shimadzu, Columbia, MA). GC-MS interface temperature was 300 °C, and the ion source temperature was 200 °C, with 70 V/150 μA ionization voltage/current. The mass spectrometer was set to scan m/z range 50–600, with ~1 kV detector sensitivity. For analysis of pyruvate, the derivatization procedure was modified by the substitution of ethylhydroxylamine for methoxyamine, and the initial GC-MS oven temperature was 110 °C for 4 min, rising to 230 °C at 6 °C/min and after that as above. Metabolites were quantified against varied amounts of standard mixtures run in parallel and data were analyzed using Metaquant. Quantities were corrected for recovery using the L-norvaline internal standard. These methods have been previously reported81.

PCA analysis.

Dimensionality reduction method was carried out on all samples using Principle Component Analysis (PCA) in RStudio 2023.06.0 Build 421. Metabolites were read as .csv files and assigned as data matrices and PCA was carried out on sample groups using the prcomp function. Missing values were removed using na.omit and PCA plots were generated using ggplot282.

RRBS.

100–200 mg of tumor tissue from 22 U87MG and HT1080 xenografts tumors was weighed and then shipped in dry ice for RRBS analysis at Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA). There, tissues were subjected to proteinase K digest solution (0.5% SDS, 0.5mg/ml proteinase K, 100 mM EDTA, in TE pH 8) by allowing the samples to rotate overnight at 55°C. For library preparation and sequencing, 100 ng of gDNA was digested with TaqaI (NEB Ipswich, MA) at 65 °C for 2 h followed by MspI treatment (NEB Ipswich, MA) at 37°C overnight. Following enzymatic digestion, samples were used for library generation using the Ovation RRBS Methyl-Seq System (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The digested DNA was randomly ligated, and, following fragment end repair, bisulfite was converted using the EpiTect Fast DNA Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen 59824) following the Qiagen protocol. After conversion and clean-up, samples were amplified, resuming the Ovation RRBS Methyl-Seq System protocol for library amplification and purification. Libraries were measured using the Agilent 2200 TapeStation System and quantified using the KAPA Library Quant Kit ABI Prism qPCR Mix (Roch, Boston, MA). Libraries were sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA) at SE75.

RRBS data processing and analysis.

Methylation calls were produced using Bismark and imported into the MethylKit R package (v. 1.28.0)83. CpGs with more than ten reads were included in the downstream analysis. Filtered counts were normalized and CpG dinucleotides were merged (destrand = FALSE). Most variable CpGs across tumors were calculated as having a standard deviation > 0.90. Samples were visualized using PCA and hierarchical clustering using the Ward method. For HT1080* tumors, to perform pairwise comparisons in methylation levels, samples of interest were merged into one object containing common CpGs. Pearson correlation was used to assess concordance between D2HG amount in the tumors and DNA methylation levels of CpG sites. Differential methylation analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test and differentially methylated CpGs were selected based on q < 0.05 and percent methylation difference > 20%. For U87MG tumors, CpGs were first filtered to include the most variable sites (CpGs with standard deviation > 10) and differential methylation analysis was performed as described, with a notable exception that CpGs were selected based on q < 0.05 and methylation difference > 10%. Feature annotation was done using ChIPseeker (v. 1.38.0) R package84,85. Genomic annotation for hg38 were retrieved using the TxDb.Hsapiens.UCSC.hg38.knownGene R package86. GREAT analysis software tool (with default parameters)87,88 was applied to determine enriched GO terms near the differentially methylated CpGs. The entire filtered CpG sites used for differential methylation analysis was used as the genomic background for GREAT analysis.

RNA-seq.

RNA samples were processed at the University of California, San Diego Institute for Genomic Medicine (IGM). RNA samples were extracted from 22 tumor tissues using QIAzol Lysis Reagent (QIAGEN, Germantown, MD). 100–200 mg of the tumor tissue was placed in gentle MACS M tubes (Miltenyi Biotec San Diego, CA). 500 μL of QIAzol Lysis Reagent was added to the tissue, and the samples were dissociated mechanically using a gentle MACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA). All tubes were incubated at room temperature for 5 min, and cell lysate was transferred to an autoclaved Eppendorf tube. Chloroform (0.2 mL) was added, followed by 30 s vortexing and a 5 min incubation at room temperature. Following separation by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, the top of three total layers containing RNA was transferred to a new autoclaved Eppendorf tube. After adding 0.5 mL of isopropanol samples were mixed by vortexing for 15 s and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Tubes were then clarified by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was aspirated and 1 mL of 75% ethanol was added to the pellet that was mixed with vortexing for 15–30 s. Samples were then separated by centrifugation at 7,500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed, and the RNA pellets were air-dried for 5 min and then dissolved in 50–70 μL of RNase-free water. The integrity of RNA was assessed on a 1% agarose gel in 1x TAE buffer (0.4 M tris acetate pH 8.3 at room temperature, 0.01 M EDTA). An RNA quality control check was conducted at IGM and only high-quality RNA samples with RIN ≥ 7.4 were used to generate the RNA-seq libraries. Libraries were generated using the Illumina Ribo-Zero Plus rRNA Depletion Kit with IDT for Illumina RNA UD Indexes (Illumina, San Diego, CA). All samples were processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Generated libraries were multiplexed and sequenced with 150 base pair (bp) Paired End (PE150) to a depth of approximately 25 million reads per sample on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000. Samples were finally demultiplexed using bcl2fastq v2.20 Conversion Software (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

RNA-seq data processing and analysis.

The quality of the raw RNAseq data was evaluated using FASTQC v0.12.189. Based on the FASTQC reports, potential adapter contamination and low-quality sequences were identified and trimmed using Cutdapt v4.890. Cutadapt parameters were set for paired-end reads, with a quality cutoff of 20 and a minimum filter length of 20. The genome index was constructed using the hg38 reference genome assembly obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) with the Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference (STAR) aligner version v2.7.11b91. Subsequently, quality-filtered reads were aligned to this genome index using STAR. The aligned reads were sorted by read name using sambamba v1.01 to prepare them for counting92. featureCounts v2.0.6 was utilized to count the number of reads per annotated gene93. The raw gene counts underwent normalization using DESeq2 for subsequent analyses94. DESeq2 was also used to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the mutants when compared to the wild type. Significant DEGs are defined as genes exhibiting an adjusted p-value (FDR) below 0.05. Pathway analysis was performed to identify significantly enriched gene sets from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), as well as the Gene Ontology (GO) databases covering biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components using ClusterProfiler v4.10.195–97. Significantly enriched, upregulated, and downregulated pathway alterations in the mutants when compared to the wild type are determined by an adjusted p-value (FDR) below 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

LEIH vectors containing WT and R132H IDH1 were a gift from William Kaelin Jr. (Dana Farber Cancer Institute). HT1080* were a gift from Kun-Liang Guan (UC San Diego). Normal human astrocytes (NHA) were a gift from Russ Pieper (UC San Francisco). C28 cells were a gift from Johnathan Trent (University of Miami). This work was funded by a Research Scholar Grant, RSG-19-075-01-TBE, from the American Cancer Society (C.D.S.), National Institutes of Health R35 GM137773 (C.D.S.), the California Metabolic Research Foundation (SDSU), the German Cancer Aid, Max Eder Program grant, 70114934 (S.T.), and the Rees-Stealy Research Foundation (E.A.). The Sanford Burnham Prebys Protein Production and Analysis Facility is supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA030199. The UC San Diego IGM Genomics Center utilized an Illumina X Plus that was purchased with funding from a National Institutes of Health SIG grant (#S10 OD026929).

Footnotes

Code availability

All bioinformatics software and tools used here are publicly available.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary information is included.

References

- 1.Murugan A. K. & Alzahrani A. S. Isocitrate Dehydrogenase IDH1 and IDH2 Mutations in Human Cancer: Prognostic Implications for Gliomas. Br J Biomed Sci 79, 10208 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dang L. et al. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature 462, 739–744 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sasaki M. et al. D-2-hydroxyglutarate produced by mutant IDH1 perturbs collagen maturation and basement membrane function. Genes Dev 26, 2038–49 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doll S., Urisman A., Oses-Prieto J. A., Arnott D. & Burlingame A. L. Quantitative Proteomics Reveals Fundamental Regulatory Differences in Oncogenic HRAS and Isocitrate Dehydrogenase (IDH1) Driven Astrocytoma. Mol Cell Proteomics 16, 39–56 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Figueroa M. E. et al. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell 18, 553–67 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chowdhury R. et al. The oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate inhibits histone lysine demethylases. EMBO Rep 12, 463–9 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu W. et al. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer cell 19, 17–30 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu C. et al. IDH mutation impairs histone demethylation and results in a block to cell differentiation. Nature 483, 474–8 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turcan S. et al. IDH1 mutation is sufficient to establish the glioma hypermethylator phenotype. Nature 483, 479–83 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes L. A. E. et al. The CpG island methylator phenotype: what’s in a name? Cancer Res 73, 5858–5868 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao J. et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal 6, pl1 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleven A. H. G. et al. IDH1 or −2 mutations do not predict outcome and do not cause loss of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine or altered histone modifications in central chondrosarcomas. Clin Sarcoma Res 7, 8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu X. et al. Structures of human cytosolic NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase reveal a novel self-regulatory mechanism of activity. J Biol Chem 279, 33946–57 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pietrak B. A tale of two subunits: how the neomorphic R132H IDH1 mutation enhances production of alphaHG. Biochemistry 50, 4804–12 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rendina A. R. et al. Mutant IDH1 enhances the production of 2-hydroxyglutarate due to its kinetic mechanism. Biochemistry 52, 4563–77 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang B., Zhong C., Peng Y., Lai Z. & Ding J. Molecular mechanisms of ‘off-on switch’ of activities of human IDH1 by tumor-associated mutation R132H. Cell Res 20, 1188–200 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xie X. et al. Allosteric mutant IDH1 inhibitors reveal mechanisms for IDH1 mutant and isoform selectivity. Structure 25, 506–513 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pusch S. et al. D-2-Hydroxyglutarate producing neo-enzymatic activity inversely correlates with frequency of the type of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutations found in glioma. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2, 19 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poetsch L. et al. Characteristics of IDH-mutant gliomas with non-canonical IDH mutation. J Neurooncol 151, 279–286 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avellaneda Matteo D. et al. Molecular mechanisms of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mutations identified in tumors: The role of size and hydrophobicity at residue 132 on catalytic efficiency. J Biol Chem 292, 7971–7983 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avellaneda Matteo D. et al. Inhibitor potency varies widely among tumor-relevant human isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 mutants. Biochem J 475, 3221–3238 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mealka M. et al. Active site remodeling in tumor-relevant IDH1 mutants drives distinct kinetic features and potential resistance mechanisms. Accepted to Nat Comm 2024.01.10.574970 doi: 10.1101/2024.01.10.574970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tesileanu C. M. S. et al. Non-IDH1-R132H IDH1/2 mutations are associated with increased DNA methylation and improved survival in astrocytomas, compared to IDH1-R132H mutations. Acta Neuropathol 141, 945–957 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Nunno V. et al. Clinical and Molecular Features of Patients with Gliomas Harboring IDH1 Non-canonical Mutations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Ther 39, 165–177 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Achouri Y. et al. Identification of a dehydrogenase acting on D-2-hydroxyglutarate. Biochem J 381, 35–42 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clairmont C. S. & D’Andrea A. D. REV7 directs DNA repair pathway choice. Trends Cell Biol 31, 965–978 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paniagua I. et al. MAD2L2 promotes replication fork protection and recovery in a shieldin-independent and REV3L-dependent manner. Nat Commun 13, 5167 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boersma V. et al. MAD2L2 controls DNA repair at telomeres and DNA breaks by inhibiting 5’ end resection. Nature 521, 537–540 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y. et al. MAD2L2 inhibits colorectal cancer growth by promoting NCOA3 ubiquitination and degradation. Mol Oncol 12, 391–405 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu K., Zheng X., Shi H., Ou J. & Ding H. MAD2L2, a key regulator in ovarian cancer and promoting tumor progression. Sci Rep 14, 130 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith M. L. et al. Interaction of the p53-regulated protein Gadd45 with proliferating cell nuclear antigen. Science 266, 1376–1380 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X. W. et al. GADD45 induction of a G2/M cell cycle checkpoint. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 96, 3706–3711 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harkin D. P. et al. Induction of GADD45 and JNK/SAPK-dependent apoptosis following inducible expression of BRCA1. Cell 97, 575–586 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guo D. et al. GADD45g acts as a novel tumor suppressor, and its activation suggests new combination regimens for the treatment of AML. Blood 138, 464–479 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X. et al. Gadd45g initiates embryonic stem cell differentiation and inhibits breast cell carcinogenesis. Cell Death Discovery 7, 271 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang P. Gadd45g insufficiency drives the pathogenesis of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nature Communications 15, 2989 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rozeman L. B. et al. cDNA expression profiling of chondrosarcomas: Ollier disease resembles solitary tumours and alteration in genes coding for components of energy metabolism occurs with increasing grade. The Journal of Pathology 207, 61–71 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Enrich C. et al. Annexin A6—Linking Ca2+ signaling with cholesterol transport. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1813, 935–947 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao J., Wan S., Chen S. & Yang L. ANXA6: a key molecular player in cancer progression and drug resistance. Discov Oncol 14, 53 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas D. et al. Dysregulated Lipid Synthesis by Oncogenic IDH1 Mutation Is a Targetable Synthetic Lethal Vulnerability. Cancer Discovery 13, 496–515 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han J., Wu J. & Silke J. An overview of mammalian p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases, central regulators of cell stress and receptor signaling. F1000Res 9, F1000 Faculty Rev-653 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen Y., Chen Z., Tang Y. & Xiao Q. The involvement of noncanonical Wnt signaling in cancers. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 133, 110946 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myant K. & Sansom O. Efficient Wnt mediated intestinal hyperproliferation requires the cyclin D2-CDK4/6 complex. Cell Div 6, 3 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bouchard C. et al. Direct induction of cyclin D2 by Myc contributes to cell cycle progression and sequestration of p27. The EMBO Journal 18, 5321–5333 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.García-Gutiérrez L., Delgado M. D. & León J. MYC Oncogene Contributions to Release of Cell Cycle Brakes. Genes (Basel) 10, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]