Abstract

Objective:

Pain is common among people with advanced cancer. While opioids provide significant relief, incorporating psycho-behavioral treatments may improve pain outcomes. We examined patients' experiences with pain self-management and how their self-management of chronic, cancer-related pain may be complemented by behavioral mobile health (mHealth) interventions.

Methods:

We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews with patients with advanced cancer and pain. Each participant reviewed content from our behavioral mHealth application for cancer pain management and early images of its interface. Participants reflected on their experiences self-managing cancer pain and on app content. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using a combination of inductive and deductive thematic analysis.

Results:

Patients (n = 28; 54% female; mean age = 53) across two geographic regions reported using psychological strategies (e.g., reframing negative thoughts, distraction, pain acceptance, social support) to manage chronic cancer-related pain. Patients shared their perspectives on the integration of psycho-behavioral pain treatments into their existing medical care and their experiences with opioid hesitancy. Patient recommendations for how mHealth interventions could best support them coalesced around two topics: 1.) convenience in accessing integrated pharmacological and psycho-behavioral pain education and communication tools and 2.) relevance of the specific content to their clinical situation.

Conclusions:

Integrated pharmacological and psycho-behavioral pain treatments were important to participants. This underscores a need to coordinate complimentary approaches when developing cancer pain management interventions. Participant feedback suggests that an mHealth intervention that integrates pain treatments may have the capacity to increase advanced cancer patients' access to destigmatizing, accessible care while improving pain self-management.

Keywords: advanced cancer, cancer, cancer pain, mHealth, oncology, pain-cognitive behavioral therapy, psycho-oncology

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Cancer-related pain is common among people with advanced cancer.1 Opioid therapy remains the standard of care2 for moderate to severe cancer pain3 and can bring substantial relief. However, people with advanced cancer continue to experience poorly controlled pain.4,5 The challenge of self-managing pain in the context of a fluctuating and sometimes rapidly accelerating disease course is a burden that advanced cancer patients routinely face.

Previous qualitative analyses exploring patients' experiences with cancer-related pain have identified challenges with obtaining and managing opioids, as well as a need for alternative medications and treatment approaches.6-15 Multidisciplinary treatment approaches are effective for chronic cancer-related pain management,16-18 but few studies have explored patient preferences about incorporating psycho-behavioral interventions into their cancer pain management routine. This is especially true of patients with advanced cancer, whose cancer-related pain may result from the cancer itself or its treatment and be exacerbated by patients' appraisal of the pain.19 For example, the perceived meaning of one's pain sensation may influence patients' pain experience19 (e.g. “this pain must mean my cancer is growing”).

While behavioral and pharmacological pain coping strategies used by people with advanced cancer have been explored in other research,9,15,18,20-23 patients' strategies to psychologically cope with cancer-related pain remain poorly characterized. Accordingly, it is necessary to understand how to best integrate psychological therapies into cancer pain treatment as their traditional session-based format remains infeasible for most. To achieve this, we solicited patients' participation as we developed psycho-behavioral cancer pain education and refined a mobile health (mHealth) app designed for people with advanced cancer and pain.24 mHealth apps can deliver accessible education and symptom management support to people with advanced cancer, whose symptom burden may preclude them from attending in-person treatments or engaging with extended telehealth interventions. The app integrates opioid management support and pain-cognitive behavioral therapy (pain-CBT) as adjunctive treatments to improve advanced cancer pain management.24 We took an iterative, patient-centric approach to ensure that the app interface and pain-CBT content was relevant, engaging, and useable for target users. To do this, we conducted qualitative interviews to explore advanced cancer patients' pain management experiences, evaluate the relevance of app content, and review our recent findings.

2 ∣. METHODS

2.1 ∣. Recruitment

We recruited participants from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI, MA) and Stephenson Cancer Center (SCC, OK). The study was reviewed by Institutional Review Boards at both sites (OUHSC IRB-#13–725 approved; Dana Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) IRB-#20–453 exempted). Research staff screened outpatient palliative care clinic schedules and received referrals from staff, attempting to oversample for rurality and race/ethnicity to achieve balanced perspectives. To achieve this, the study team prioritized recruiting patients with variable sociodemographic diversity during screening and approach. We confirmed eligibility, obtained permission from clinicians, and approached patients via telephone. Patients provided informed consented to participate. Recruitment occurred from January–July 2021 (DFCI) and February–June 2022 (SCC). Participants received a $25 gift card upon interview completion.

2.2 ∣. Procedures

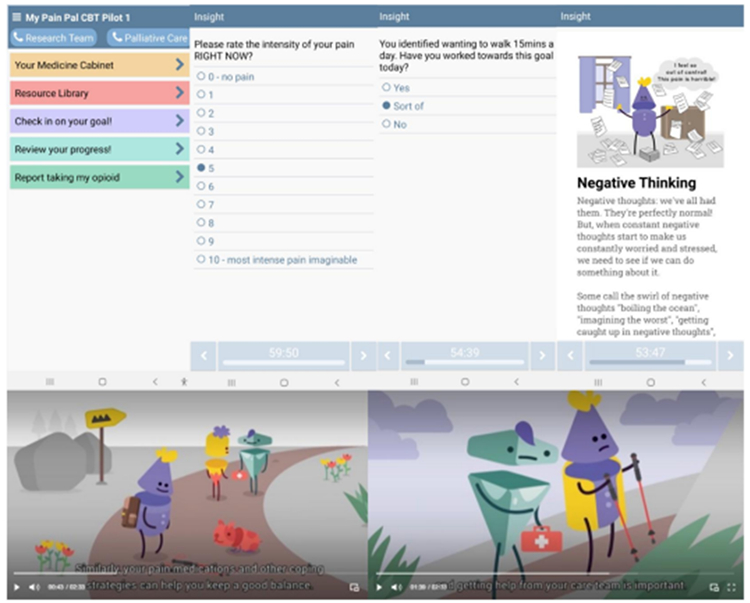

This work is a component of a larger research program intended to develop, refine, and test the STAMP + CBT mHealth app.24 We used a semi-structured interview guide (see online supplemental materials) to guide participant interviews (Figure 1). During interviews, participants reviewed app-based wireframes and web-based content. Planned and probing questions elicited participants' pain self-management strategies and reflections on the ideal role of mHealth interventions in their care. DA, a pain psychologist, trained the research team in interviewing and qualitative analysis. Interviews were conducted by the research team(DFCI: DA, MB; SCC: DA, KA), audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Recruitment stopped when data saturation was reached and no new themes were identified in data analysis meetings. Most interviews were conducted via Zoom (93%) due to COVID-19 precautions. The remaining interviews were by phone or in person per patients' preference, with interview length ranging from 22 to 78 min (Table 1).

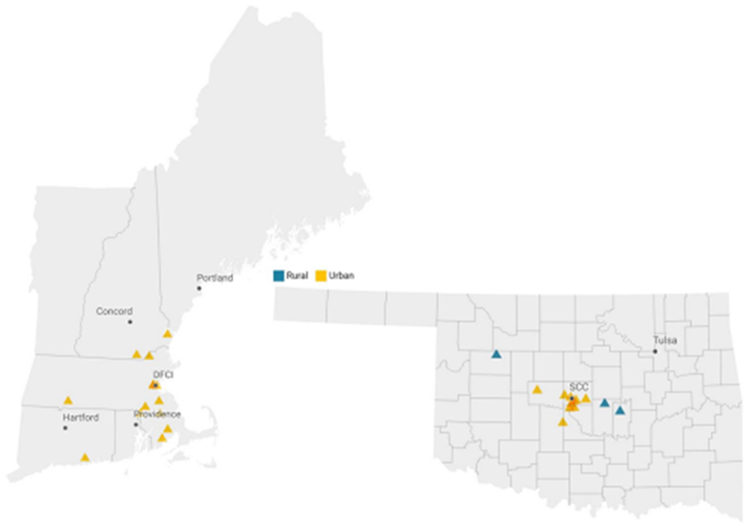

FIGURE 1.

Zip codes of participants recruited from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Stephenson Cancer Center. Zip codes were categorized as rural or urban using RUCA code designations.25 One participant in urban Texas is not shown. Created with Datawrapper. RUCA, Rural-Urban Communting Area.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics and interview statistics.

| Variable | N(%) or M(SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| DFCI participants (N = 14) |

SCC participants (N = 14) |

|

| Female | 8 (57%) | 7 (50%) |

| Age | 54.3 (9.7) years | 51.6 (12.4) years |

| Race | ||

| White | 14 (100%) | 12 (86%) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1 (7%) | |

| Black/African American | 1 (7%) | |

| Current/historical opioid use | ||

| Short-acting | 13 (93%) | 14 (100%) |

| Long-acting | 8 (57%) | 8 (57%) |

| Cancer type | ||

| Head and neck | 3 (21%) | 2 (14%) |

| Breast | 2 (14%) | 1 (7%) |

| Colorectal | 3 (21%) | 2 (14%) |

| Lung | 3 (21%) | 1 (7%) |

| Hemopoietic | 2 (14%) | |

| Kidney | 2 (14%) | 1 (7%) |

| Prostate | 1 (7%) | |

| Neuroendocrine | 1 (7%) | |

| Pancreatic | 1 (7%) | |

| Cervical | 1 (7%) | |

| Ovarian | 1 (7%) | |

| Polycythemia Vera | 1 (7%) | |

| Other(Desmoid fibromatosis) | 1 (7%) | 1 (7%) |

| Interview length(minutes) | ||

| M(SD) | 51.86 (16.06) | 42.57 (12.11) |

| Range | 24–78 | 22–64 |

| Zoom interviews | 14 (100%) | 12 (86%) |

| Rural residence | 0 | 3 (21%) |

2.3 ∣. Data analysis

To generate insights about the primary study aim (validation of app content related to pain coping among patients with advanced cancer), we used inductive and deductive thematic analysis26-28 and created topic summaries focused on intervention elements and pain coping strategies. This approach allowed us to efficiently identify and apply insights from participant feedback to the app content.

Taking a deductive approach, DA and KA developed an interview guide shaped by interest and theory-driven user-acceptability items,29 which KA used to create an initial codebook. Focusing on semantic meaning, KA modified the codebook through simultaneous inductive coding and application of the deductive codebook to DFCI interviews. When new codes were identified, KA assimilated them into the codebook and recoded previous interviews. DA and KA identified preliminary topics, their component codes, and exemplar quotes, comparing only between subjects. Using the codebook created by KA, KS repeated this process at SCC. SD combined and refined topic summaries across sites and between subjects.

3 ∣. RESULTS

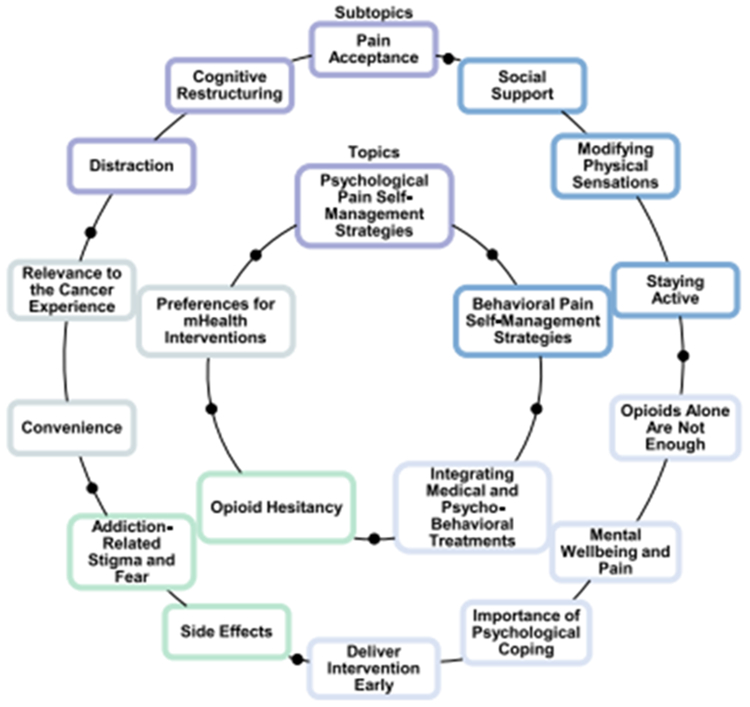

We interviewed 28 participants(DFCI n = 14; SCC n = 14). They were diagnosed with various cancer types and most were white (DFCI:100%; SCC:86%; Table 1). More SCC participants lived in rural locations than DFCI participants (Figure 2). Of the identified topic summaries, four primary topics are discussed here: psychological pain-self management strategies, perspectives on integrating medical and psychological treatments, opioid hesitancy, and preferences for content and functionalities within pain-focused mHealth interventions(see Table 2; Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Example app wireframes and educational content reviewed by participants.

TABLE 2.

Topics and sample quotes.

| Topic | Sample quotes |

|---|---|

| Psychological pain self-management strategies | |

| Cognitive restructuring | “Sometimes you can't stop those negative thoughts, but you can go, ‘Okay, you've had your five minutes of fame, it's time to try and think about something happier.’” Female, 37, pancreatic cancer “…I was really worked up about this oral pain thing… I just had to get out of my head. Be like, you don't even—it's never been that [cancer progression]. Why would it be that today, let it go.” Female, 49, thyroid cancer |

| Distraction | "Distraction is something that I use a lot when I'm in a lot of pain is putting on TV or focus on somebody else's problems or on that kind of stuff." Female, 50, breast cancer |

| Pain acceptance | “Well you don't want the pain to take control. Being able to mentally deal with it on a day to day, especially when I know the pain isn't going to go away…” Male, 52, renal cell cancer |

| Social support | “…[some friends] came over for dinner… and I was exhausted when they left last night, and ready to go die in bed as soon as they walked out the door, but, it was nice to have the company, and to get to see people that care about me.” Female, 37, pancreatic cancer |

| Integrating medical and psychological treatments | |

| Opioids alone are not enough | "…all I've basically been given… is pretty much just the pain medications… I believe, then [when stressed] you're—it's just compounding your pain that you're having or your misery that you're having… So, it's more than just taking your medications." Male, 62, lymphoma |

| Awareness that mental wellbeing impacts pain | “I think if you're not rested, it impacts—you're more susceptible to pain level being higher.” Male, 71, prostate cancer "And I think a patient would appreciate it because emotions are very well tied to pain care and taking pain meds, and they affect your body." Female, 37, desmoid fibromatosis |

| Importance of psychological coping | “The mental aspect of that stuff, and I'm sure you guys know this, but you can get pretty low. You can get kinda in your head with cancer. So, I would think pain management is a big thing, but also the mental health aspect would, be something that I would definitely use– ‘Cause I, I wish—I've been there. [sniffles] it can be terrible.” Male, 53, head and neck cancer "So you're feeling crummy is adding on to your actual physical pain, the real pain you have, never mind your mental and mental pain increases your real—your physical pain from your nerves that you're having." Male, 62, lymphoma |

| Opioid hesitancy | |

| Addiction-related stigma and fear | “It took me forever to find a doctor that was willing to write that prescription… and he could just tell that I really needed it. It's just nice not to have them threaten all the time. You know, like, ‘Well, we might have to—we might have to cut you back,’ and, ‘We might have to do this.’ And I just go, and I know they're gonna treat me like a human that needs help, that's in pain. That I'm not trying to get a fix, or crush it down in a spoon, or nothing like that.” Female, 46, desmoid fibromatosis “I didn't really aggressively try to manage that pain. Because, at points, I get really scared of becoming addicted to pain medication. Which seems really silly for a terminal cancer patient. But it's just like, I'm not to the point where I'm, like, actively dying yet. So, I don't want to be like, hindered by addiction.” Female, 27, ovarian cancer |

| Side effects | “If I have to take—everything that I'm on makes me drowsy. So, sometimes I have to pick and choose what I'm gonna alleviate” Female, 38, neuroendocrine cancer |

| mHealth preferences | |

| Relevant | "I mean and most people, almost everybody can relate to what they're saying, pain affects your mood, your negative thinking, negative thinking affects your pain." Male, 62, cervical cancer “I feel like there might be some older people that are a little turned off by the animation [app content], but, for me, it—like I said, it's kinda just simple and relatable. Information that is definitely pertaining to my particular experience.” Female, 37, pancreatic cancer |

| Convenient tools and resources | “I think it'd be helpful to have it there on the phone so you can track it [pain and symptoms] …” Male, 71, prostate cancer “If I get off schedule, it throws me into a couple days of, you know, ‘oh my goodness’ kinda thing. And having all of the—the reminders, and the tools, and to cope would be nice.” Female, 37, pancreatic cancer "But this [video] is very informative also to help because I think pain and stress are very—with cancer, they're not helpful. So, it's something that we need the education on… I don't know all of my medicines and I'm just trusting my doctor. But if I have a better knowledge, or better management, it would help me." Female, 37, colorectal cancer |

FIGURE 3.

Primary topics identified in qualitative, semi-structured interviews with patients with advanced cancer and pain reflecting on their experiences self-managing pain and using mHealth apps for pain management support.

3.1 ∣. Psychological pain self-management strategies

Most participants described cancer-related pain as emotionally taxing. They used various psychological strategies to manage the pain itself and its impact on their quality of life. Interacting with the pain-CBT app content and wireframes prompted further reflection on psychological pain self-management strategies.

3.1.1 ∣. Cognitive restructuring

Some participants intuitively reframed negative thoughts about pain by practicing cognitive restructuring and mindfulness techniques (“If that negative thought comes in, I'm like, ‘Okay. That made me sad, but let's continue on the body [Redirect focus to the body]’” Female, 38, neuroendocrine cancer). Reframing negative thoughts required participants to understand the impact that their thoughts, mood, or stress had on their pain.

3.1.2 ∣. Distraction

To cope with pain, many participants turned to distractions, such as following a routine, watching TV, prayer or spirituality, and socializing:

There are times that regardless of what you're doing, the pain will cut through. But a lot of the times, with the smaller things, like– having folks standing around—does help. I mean, I think takes your mind off of [the pain].

(Male, 71, prostate cancer)

In general, participants felt that “keeping busy takes your mind off your pain,” (Male, 62, lymphoma) and believed that distraction supported their pain coping.

3.1.3 ∣. Pain acceptance

Many participants discussed pain acceptance. Some found it helpful to acknowledge that pain was a part of life with cancer and could be managed but not eliminated:

Most of the time what I try to do is sort of box it in a little place, you know? Like, yep, this is my pain. It's always here, whatever. I know that I have no control over this. It's either going to progress or not progress…It's just, like, an acknowledgment.

(Female, 50, breast cancer)

Many noted that pain acceptance could reduce pain suffering. They described working toward pain acceptance in the course of reframing their pain thoughts, striving to stay involved in usual activities, and practicing distraction.

3.1.4 ∣. Social support

Chronic cancer-related pain and the realities of advanced cancer made some participants feel isolated. A majority emphasized the importance of social support, especially from peers with advanced cancer and family members. For example, one male stated, “It helped me when I connected with two people who went through exactly what I've been through. It provided relief that I'm not the only one. Even though I know I'm not, you still feel isolated” (Male, 48, lymphoma).

3.2 ∣. Integrating medical and psychological treatments

A majority of participants who concurrently used opioid and psychological therapies emphasized that opioids were more effective when combined with psychological treatments and strategies to increase wellness. Many espoused the importance of psychological coping while medically managing cancer pain because “emotions are very well tied to pain care and taking pain meds…” (Female, 37, desmoid fibromatosis). Some shared personally impactful advice that they had received from mental healthcare providers, while others discussed their need for mental health support after diagnosis. Engaging with the mHealth intervention prompted some participants to reflect on how useful the intervention would have been to them soon after diagnosis, suggesting a dearth of adequate and accessible psycho-behavioral pain treatment early in their cancer trajectory. (“I hope you guys get this up and running, you know, as soon as possible… I wish I could have had it, um, back then.” Male, 53, head and neck cancer).

3.3 ∣. Opioid hesitancy

Despite clear need for analgesia, participants' ability to integrate medical and psychological care was impeded by their own and providers' opioid hesitancy. Addiction-related stigma and fear complicated access to opioids and caused participants and their providers to resist initiating opioid use or to under dose. A few participants noted that family members' history of addiction caused opioid hesitancy(“I didn't really aggressively try to manage that pain….Because, at points, I get really scared of becoming addicted to pain medication…. Just ‘cause I do have a family history of [addiction].” Female, 27, ovarian cancer). Participants’ concerns about side effects also generated opioid hesitancy (Table 2).

3.4 ∣. Preferences for content and functionalities within mHealth interventions

While reviewing the pain-CBT mHealth intervention, participants commented on the app's relevance to the advanced cancer experience and its convenience.

3.4.1 ∣. Relevance

Many participants felt that intervention content reflected their emotional experience of cancer-related pain (“The way I think, it's in there [article about cognitive restructuring].”Female, 51, cervical cancer). Participants also noted when intervention content captured their pain and cancer experience:

I can identify with what the video, you know, says, that it [pain and other symptoms] leaves you unknowing whether it’s, you know it’s gonna happen today, tomorrow, there’s not like a schedule.

(Female, 37, pancreatic cancer)

The few participants who did not feel that intervention content was relevant stated that they already knew the information or felt their symptom burden precluded engagement. Two felt that their severest symptoms would prevent app use or influence their willingness to engage. Importantly, a majority of participants felt that the mHealth intervention itself was appropriate for people with advanced cancer.

3.4.2 ∣. Convenience

Participants appreciated convenient access to resources and tools.

Using mHealth resources.

Most participants could see themselves using the intervention. They felt that having resources and tracking tools on their smartphones would be convenient, so much so that they would be open to using the intervention in times of discomfort:

If I was, you know, experiencing, the pain like I was, or, discomfort and all that, yeah, I would definitely be reaching out for any type of help or, any type of care like that.

(Male, 53, head and neck cancer)

A few participants were uncomfortable using smartphones, were not interested in adding a new intervention to their care, or felt their symptom burden was too significant.

Tools to communicate with healthcare teams.

Multiple participants felt that the mHealth intervention would help them track their symptoms and better communicate with their providers:

If I was using this app and—able to, express to them in like, a numerical this is what I've been feeling over the past couple of days, that might help with being able to prescribe something that managed it a little bit better.

(Female, 27, ovarian cancer)

Participants felt that the intervention could bridge gaps in communication, saying, “I mean the doctors need to know. You know, you don't see them every day” (Female, 64, breast) and emphasizing that “I like being able to—if you are hurting—being able to get ahold of somebody fairly quickly” (Male, 53, head and neck cancer).

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

Participants used several key psychological coping strategies—including cognitive restructuring, distraction, pain acceptance, and social support—and preferred multidisciplinary pain care over unimodal opioid therapy. While psychological strategies were instrumental to their eventual coping with chronic cancer-related pain, most indicated that developing these strategies took time. Consequently, participants expressed a strong desire for earlier access to pain psychological interventions to reduce pain suffering. Participants wanted convenient and relevant interventions with accessible education about psycho-behavioral treatments for cancer pain, symptom tracking, and tools to communicate about their pain with clinicians. Participants viewed mHealth interventions as a potential tool to fulfill these needs because they could review content on demand and remotely share current symptoms with their providers.

While some psychological pain coping strategies used by advanced cancer patients have been identified (e.g., manipulating catastrophic thoughts,13 adjusting hopes or expectations,22,30 distraction18,20), strategies like acceptance and patient preferences regarding the integration of their existing psychological pain self-management strategies with current pharmacological standard of care practices have not been previously explored or described. Our participants endorsed the usefulness of additional support to successfully integrate opioid therapy with non-pharmacologic pain management strategies. Such descriptions can assist the development of pain management interventions that will be more acceptable to patients with advanced cancer and in turn may provide more successful pain management.

There are existing descriptions of advanced cancer patients' pain self-management through opioid therapy and behavioral strategies. Our participants had experiences with opioid hesitancy that are similar to those identified in other studies (e.g., opioid stigma,7,31 variability in daily opioid dosing regimens,9,11,12,20-23 breakthrough pain11,15). They also used behavioral pain strategies that overlap with those described by other researchers (e.g., adapting routines,20,23 staying active,21,22 and non-pharmacological strategies to modify physical sensations with tools, devices, or complementary alternative medicine9,20,22).

Participants' comfort with technology despite substantial symptom burden suggests that mHealth interventions may have the capacity to circumvent barriers to obtaining advanced-cancer-specific psycho-behavioral pain treatments. Participants' perceptions that the app reflected their experiences is likely the result of iterative, user-centered development, which may improve usability. We will conduct further app testing to evaluate whether integrating psycho-behavioral treatments with medication support improves pain outcomes for patients and whether barriers related to low technology literacy can be further reduced.

4.1 ∣. Study strengths and limitations

Limitations include recruitment bias and the speculative nature of participants' assessments of intervention usability. Participants were recruited from academic medical centers and approached remotely, which may have contributed to poor racial and ethnic diversity. Additionally, participants who agreed to participate in the study may have had higher levels of comfort with technology or familiarity with psychological coping skills for pain. Though the median age of cancer diagnosis in the U.S. is 66,32 the median age of our sample was 53. While some older adults may be uncomfortable with mHealth interventions, the majority of participants in our sample were open to the intervention. Offering computerized approaches,13,33,34 in-person training, instructions and help guides, and simplified visual design may improve accessibility of technology-based interventions to older adults.35,36 Participants reviewed app content and wireframes as opposed to testing a functional app. Therefore, opinions about the usability of the app may differ in future testing.

Our user-centered approach to app development is a strength of this study. By seeking the feedback of target end-users, we sought to enhance intervention acceptability. This application of user-centered design is especially appropriate for intervention development for individuals with advanced cancer, who sometimes experience exclusion from chronic pain contexts due to a paucity of cancer-pain-specific treatments and the concurrent, exclusionary impact of factors like rurality or membership within medically-underserved populations. Geographic diversity across study sites contributed to the richness of the qualitative data—participants in Oklahoma more readily discussed barriers to care, opioid stigma, and the impact of symptoms on their lives.

4.2 ∣. Clinical implications

The majority of participants desired additional psycho-behavioral support that would be directly integrated with their medical cancer pain treatments. Such perspectives can inform the development and iteration of many scalable interventions intended to increase both the accessibility and integration of psycho-behavioral treatments to support cancer pain care.

4.3 ∣. Conclusions

Participants used various psychological strategies to self-manage pain, desired multidisciplinary pain treatments, and had strong preferences about the benefits of integrating pain-focused behavioral interventions into their care. Future work is needed to explore the efficacy of mHealth interventions that integrate psychosocial and medical treatments to improve the self-management of advanced cancer-related pain.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the participants for their role in the research. This work was supported by the National Palliative Care Research Center (PI Azizoddin), the National Institutes of Health-National Cancer Institute [NIH-NCI R21CA263838; NIH-NCI K08CA26693] (PI Azizoddin), and the Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust/Health Promotion Research Center [TSET-HPRC R23-02].

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

SMD, KS, KA, ARB, MB, JAT, RRE, and DRA have no conflicts to disclose. ACE receives research funding from Medtronic. MA receives funding through a research fellowship from Yorkshire Cancer Research. KLS serves on the editorial board of Anesthesiology, has received funding from Anesthesiology to attend an ANZCA meeting, has received payment or honoraria as a Grand Rounds speaker, and is the Vice Chair of Faculty Development in the Department of Anesthesiology, Brigham and Women's Hospital.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Upon reasonable request, the data supporting the findings of the study will be made available by the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Van den Beuken-van Everdingen MHJ, Hochstenbach LMJ, Joosten EAJ, Tjan-Heijnen VCG, Janssen DJA. Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2016;51(6):1070–1090. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, et al. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(9):592–596. 10.1056/NEJM199403033300902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization WHO. WHO Guidelines for the Pharmacological and Radiotherapeutic Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Adolescents; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deandrea S, Corli O, Consonni D, Villani W, Greco MT, Apolone G. Prevalence of breakthrough cancer pain: a systematic review and a pooled analysis of published literature. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;47(1):55–76. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deandrea S, Montanari M, Moja L, Apolone G. Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(12):1985–1991. 10.1093/annonc/mdn419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adam R, Bruin M, Burton CD, Bond CM, Clausen MG, Murchie P. What are the current challenges of managing cancer pain and could digital technologies help? BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2018;8(2):204–212. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bulls HW, Hamm M, Wasilko R, et al. Manifestations of opioid stigma in patients with advanced cancer: perspectives from patients and their support providers. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18(10):e1594–el602. 10.1200/OP.22.00251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorfman CS, Shelby RA, Stalls JM, et al. Improving symptom management for survivors of young adult cancer: development of a novel intervention. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2022;00(00):472–487. 10.1089/jayao.2022.0100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hackett J, Godfrey M, Bennett MI. Patient and caregiver perspectives on managing pain in advanced cancer: a qualitative longitudinal study. Palliat Med. 2016;30(8):711–719. 10.1177/0269216316628407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwon JH. Overcoming barriers in cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1727–1733. 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manzano A, Ziegler L, Bennett M. Exploring interference from analgesia in patients with cancer pain: a longitudinal qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2013;23(13-14):1877–1888. 10.1111/jocn.12447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid CM, Gooberman-Hill R, Hanks GW. Opioid analgesics for cancer pain: symptom control for the living or comfort for the dying? A qualitative study to investigate the factors influencing the decision to accept morphine for pain caused by cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(1)44–48. 10.1093/annonc/mdm462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somers TJ, Kelleher SA, Dorfman CS, et al. An mHealth pain coping skills training intervention for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients: development and pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;16(3):e66. 10.2196/mhealth.8565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winger JG, Ramos K, Steinhauser KE, et al. Enhancing meaning in the face of advanced cancer and pain: qualitative evaluation of a meaning-centered psychosocial pain management intervention. Palliat Support Care. 2020;18(3):263–270. 10.1017/S1478951520000115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright EM, El-Jawahri A, Temel JS, et al. Patient patterns and perspectives on using opioid regimens for chronic cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2019;57(6):1062–1069. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaza C, Baine N. Cancer pain and psychosocial factors: a critical review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2002;24(5):526–542. 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00497-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorin S, Krebs P, Badr H, et al. Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions to reduce pain in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(5):539–547. 10.1200/jco.2011.37.0437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Syrjala KL, Jensen MP, Mendoza ME, Yi JC, Fisher HM, Keefe FJ. Psychological and behavioral approaches to cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1703–1711. 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.4825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heathcote LC, Eccleston C. Pain and cancer survival: a cognitive-affective model of symptom appraisal and the uncertain threat of disease recurrence. Pain. 2017;158(7):1187–1191. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeager KA, Bauer-Wu S, Dilorio C, Quest TE, Sterk CE, Vena C. Managing one's symptoms: a qualitative study of low-income African Americans with advanced cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39(4):303–312. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erol O, Unsar S, Yacan L, Pelin M, Kurt S, Erdogan B. Pain experiences of patients with advanced cancer: a qualitative descriptive study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;33:28–34. 10.1016/j.ejon.2018.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siv D, Nooijer K, Cramm JM, et al. Self-management of patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review of experiences and attitudes. Palliat Med. 2020;34(2):160–178. 10.1177/0269216319883976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibbins J, Bhatia R, Forbes K, Reid CM. What do patients with advanced incurable cancer want from the management of their pain? A qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2014;28(1):71–78. 10.1177/0269216313486310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azizoddin DR, DeForge SM, Baltazar A, et al. Development and prepilot testing of STAMP + CBT: an mHealth app combining pain cognitive behavioral therapy and opioid support for patients with advanced cancer and pain. Support Care Cancer. 2024;32(2). 10.1007/s00520-024-08307-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Economic Research Service. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2020. Accessed August 17, 2020. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V, Clarke V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int J Transgender Health. 2023;24(1):1–6. 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2020;18(3):328–352. 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tariman JD, Donna L, Berry BH, Wolpin S, Schepp K. Validation and testing of the Acceptability E-scale for web-based patient-reported outcomes in cancer care. Appl Nurs Res. 2011;24(1):53–58. 10.1016/j.apnr.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulman-Green D, Bradley EH, Knobf MT, Prigerson H, DiGiovanna MP, McCorkle R. Self-management and transitions in women with advanced breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2011;42(4):517–525. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azizoddin D, Knoerl R, Adam R, et al. Cancer pain self-management in the context of a national opioid epidemic: experiences of patients with advanced cancer using opioids. Cancer. 2021;127(17):3254–3263. 10.1002/cncr.33645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Surveyillnce E, and End Results (SEER) Program. Cancer Stat Facts. National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somers TJ, Kelleher SA, Westbrook KW, et al. A small randomized controlled pilot trial comparing mobile and traditional pain coping skills training protocols for cancer patients with pain. Pain Res Treat. 2016;2016. 10.1155/2016/2473629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Somers TJ, Abernethy AP, Edmond SN, et al. A pilot study of a mobile health pain coping skills training protocol for patients with persistent cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2015;50(4):553–558. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gomez-Hernandez M, Ferre X, Moral C, Villalba-Mora E. Design guidelines of mobile apps for older adults: systematic review and thematic analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2023;11:e43186. 10.2196/43186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morey SA, Stuck RE, Chong AW, Barg-Walkow LH, Mitzner TL, Rogers WA. Mobile health apps: improving usability for older adult users. Ergon Des Q Hum Factors Appl. 2019;27(4):4–13. 10.1177/1064804619840731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Upon reasonable request, the data supporting the findings of the study will be made available by the corresponding author.