Abstract

Multiple representatives of eulipotyphlan mammals such as shrews have oral venom systems. Venom facilitates shrews to hunt and/or hoard preys. However, little is known about their venom composition, and especially the mechanism to hoard prey in comatose states for meeting their extremely high metabolic rates. A toxin (BQTX) was identified from venomous submaxillary glands of the shrew Blarinella quadraticauda. BQTX is specifically distributed and highly concentrated (~ 1% total protein) in the organs. BQTX shares structural and functional similarities to toxins from snakes, wasps and snails, suggesting an evolutional relevancy of venoms from mammalians and non-mammalians. By potentiating thrombin and factor-XIIa and inhibiting plasmin, BQTX induces acute hypertension, blood coagulation and hypokinesia. It also shows strong analgesic function by inhibiting elastase. Notably, the toxin keeps high plasma stability with a 16-h half-life in-vivo, which likely extends intoxication to paralyze or immobilize prey hoarded fresh for later consumption and maximize foraging profit.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-021-04116-x.

Keywords: Venom, Toxin, Blarinella quadraticauda, Thrombin. FXIIa

Introduction

Fossil evidence indicates that many extinct mammals possessed venom delivery apparatuses [1, 2]. Existing venomous mammals are rare [3] but include shrews [4, 5], platypuses [6, 7], slow lorises [8, 9], and vampire bats [10, 11]. Most venomous mammals are insectivores, such as hedgehogs, moles, shrews, and solenodons, which deliver toxic salivary secretions to prey through grooved teeth [12]. Compared with many invertebrate and vertebrate venomous animals, such as scorpions, spiders, snakes, and lizards [13], mammalian venom remains poorly characterized. Many shrew species contain an oral venom system [14, 15], which they utilize to overpower larger prey [16, 17]. The toxic component (BLTX) of venom from the northern short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) was first characterized in 2004 [16]. Mature BLTX is a kallikrein-like protease containing 253 amino acid (aa) residues and two N-glycosylations at Asn80 and Asn93. This toxin produces kinins by cleaving kininogens to induce dyspnea, hypotension, and hypokinesia [16]. However, another kallikrein-like protease identified from B. brevicauda venom (blarinasin) is non-toxic, despite its high similarity to BLTX, suggesting that minor differences (e.g., glycosylation) may be important for toxicity [18].

Soricinae shrews require large amounts of food to meet their energetic demands and high metabolic rates [19, 20]. The use of venom helps shrews to overpower and hoard large comatose prey [17], with hoarding behavior frequently observed in different shrew species [17, 19–25]. Generally, small prey is consumed immediately by shrews, while larger prey is paralyzed, immobilized, and hoarded for later consumption. The Asiatic Short-tailed Shrew (Blarinella quadraticauda) from the Soricidae family is distributed in southwestern China and northern Vietnam (Fig. S1A) [26]. Like its North American cousin B. brevicauda, it is a highly active and voracious insectivore and can paralyze and subdue prey using venom. In addition to preying on insects, B. quadraticauda can also kill small animals such as mice [27, 28]. The first incisors on the upper and lower jaws are long and serrated, with a clear groove formed by the two bottom incisors (Fig. S1B). In humans, B. quadraticauda bites can result in severe swelling and pain, with at least one reported case of thrombosis and hypertension induced after being bitten on the foot (Fig. S1C). Thus, evidence suggests that this venomous shrew is a potentially dangerous mammal containing procoagulant toxins. In the current study, we explored the toxic components of the venom and the underlying mechanisms related to the potential induction of thrombosis and hypertension as well as hoarding behavior.

Methods

Animals

All animal-based experiments conformed to the recommendations in the guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. All experiments complied with national legislation and were approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (SMKX-2016013). All possible effort was made to reduce sample size and minimize animal suffering. To assess salivary gland toxins of shrew, four mature B. quadraticauda shrews (four males, 4–8 g) were caught after setting traps at several sites in Ailao Mountains of Yunnan, China. After anesthesia, their submaxillary glands were immediately removed and dissected. Two pairs of the submaxillary glands were placed in 100 μl of RNA storage solution (Tiangen, China) and stored at − 20 °C, while the other two pairs were kept in liquid nitrogen.

Purification of procoagulant toxin (BQTX) from submaxillary glands

Submaxillary glands were homogenized in 0.05 M Tris–HCl containing 0.1 M NaCl (pH 7.8). The supernatant was collected and lyophilized after centrifugation at 4 °C for 10 min at 10 000 g. The lyophilized submaxillary gland powder was dissolved in 5 ml of 0.05 M Tris–HCl (pH 7.8) and filtered through a 30-kDa cut-off Centriprep filter (Millipore, USA). The filtrate was applied to a C4 reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC, Hypersil GOLD™C4, 25 × 0.46 cm, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) column. Proteins/peptides were eluted from the C4 RP-HPLC column by a water/acetonitrile elution system containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The absorbance of the eluate was monitored at both 215 and 280 nm. The effects of each eluted fraction on thrombin were assayed using chromogenic substrates, as described below. The fractions showing activity were pooled and lyophilized, then resuspended in 1 ml of 0.05 M Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), before further purification by C4 RP-HPLC. The eluted fraction of C4 RP-HPLC was lyophilized, resuspended with 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8), and applied to a Mono Q™ 5/50 GL column (Cytiva, USA) connected to an AKTA Explorer 10S fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) system (Cytiva, USA). The column was equilibrated with solvent A (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.8) and elution was performed with a linear gradient of 0–30% solvent B (20 mM Tris–HCl, 1 M NaCl, pH 7.8) over 30 min.

Mass spectrometry analysis and amino acid (aa) sequencing

The purified native protein was analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF–MS, AXIMA CFR, Kratos Analytical, UK) to determine molecular weight. The aa sequences of the N-terminus and some peptide fragments from trypsin digestion were determined by automatic Edman degradation on a pulsed liquid-phase sequencer (model 491, Applied Biosystems, USA). All procedures were performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions.

cDNA library construction and screening

Total RNA was extracted from the submaxillary glands using TRIzol (Invitrogen, USA). Using RNA as a template, the first strand of cDNA was synthesized by long distance-polymerase chain reaction (LD-PCR) with a SMART™ cDNA Library Construction Kit (Clontech, USA). The second strand was amplified using Advantage Polymerase with the 5’ PCR primer 5’-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT-3’ and CDS III/3’ PCR primer 5’-ATTCTAGAGGCCGAGGCGGCCGACATG(30)N–1 N-3’ (N = A/T/C/G, N–1 = A /C/G)provided by the kit. The Specific primer 5’-ACNTCNCCNCCNGCNGARGGN-3’ (R = A/G) designed according to the aa sequences determined by automated Edman degradation in the sense direction and the CDS III/3’ PCR primer 5’-ATTCTAGAGGCCGAGGCGGCCGACATG(30)N–1 N-3’ in the anti-sense direction were used for PCR to obtain the mature BQTX sequence. The anti-sense primer 5’-TTAGGAAGACTCACACGGTCC-3’ designed according to the mature BQTX sequence and the 5’ PCR primer 5’-AAGCAGTGGTATCAACGCAGAGT-3’ were used for PCR to obtain the signal peptide sequence of BQTX. PCR was performed as follows: 2 min at 95 °C followed by 30 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C, 40 s at 72 °C, and 10 min at 72 °C. The PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and recovered using a DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Tiangen, China) and then ligated into the pMD19-T vector (Takara Biotechnology Dalian Co. Ltd., China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. All positive clones were sequenced on a DNA Analyzer (ABI3730xl) at the Sangon Biology Company (Shanghai, China).

Construction of recombinant expression vector and BQTX recombinant expression and purification

The sequence encoding BQTX was obtained via PCR using two primers, i.e., 5’-CCCAAGCTTTTAGGAAGACTCACACGGTCC-3’ and 5’-CGGGGTACCGACCCAACTTCTCCACCA-3’. The enzyme-digestion sites for KpnI (GGTACC) and HindIII (AAGCTT) and the formic acid cleavage site (GACCCA) were added to the primers. The prokaryotic expression vector was constructed by inserting the DNA sequence encoding mature BQTX (402 bp) between the KpnI and HindIII sites of the pET-32a ( +) vector. Recombinant expression in Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3) was induced by 0.8 mM isopropyl-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 6 h in a 110-rpm shaker at 28 °C. After expression, E. coli cells were collected by centrifugation at 8000g for 10 min at 4 °C and resuspended in binding buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, pH 7.4), before homogenization using an Ultrasonic Cell Disruption System (XINYI-IID, XinYi, China). Finally, the supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 9289g for 1 h at 4 °C.

A Ni2+ affinity chromatography column was equilibrated in advance with a binding buffer. The collected supernatant containing fusion proteins was subsequently loaded onto the Ni2+ affinity chromatography column at a flow rate of 0.7 ml/min. The bound fusion proteins were eluted with six column volumes of elution buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 250 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, pH 7.4). We added 50% (v/v) formic acid to the solution, which was then maintained for 24 h at 55 °C to cut the fusion proteins. The eluted fraction was resuspended in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8) and salt was removed using an ultrafiltration device (Millipore, USA). The solution containing recombinant BQTX was applied to a Mono Q™ 5/50 GL column (GE Healthcare, USA) for purification in the FPLC system mentioned above.

Anti-BQTX polyclonal antibody preparation

BQTX was used to immunize guinea pigs to obtain anti-BQTX polyclonal antibodies. Here, BQTX (500 μg) in 300 μl of 0.9% NaCl was mixed with 300 μl of Freund's Complete Adjuvant. The mixture was vortexed for 1 h, and each 100 μl of the mixture was injected into the subcutaneous tissue of two adult guinea pigs (male, 280–300 g). Half of the mixture (BQTX mixed with Freund's Incomplete Adjuvant) was used for second and third immunizations. Seven days after the third immunization, blood was taken from the hearts of the guinea pigs to test the valence of the anti-BQTX antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). The dilution ratios of the plasma were 1:1 000–1:128 000.

Tissue distribution analysis of BQTX by western blot analysis

Tissues of B. quadraticauda, including submaxillary gland, heart, liver, lung, muscle, and skin, were homogenized in RIPA buffer (Sigma, USA) mixed with protease inhibitor cocktail using a glass homogenizer on ice to extract proteins. After homogenization, the tissues were centrifuged at 3000g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the protein concentrations of the supernatants were analyzed using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). Protein (50 μg) was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) with a gel concentration of 12%. The proteins were electrotransferred onto polyvinylidenefluoride (PVDF) membranes (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Germany), which were then blocked with 5% non-fat dried milk (BD, USA) dissolved in Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBST, 2.42 g/L Tris-base, 8 g/L NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.6) at room temperature for 2 h. After washing three times with TBST, the PVDF membranes were incubated with a polyclonal antibody against BQTX (diluted 1: 500) overnight at 4◦C, The membranes were subsequently washed with TBST, incubated for 1 h at room temperature in HRP-conjugated goat, anti-mouse (diluted 1: 20,000; Jackson ImmnuoResearch) secondary antibody and developed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ThermoFisher Scientific). After washing with TBST, the membranes were developed using an Enhanced Chemiluminescence Kit (Tiangen, China) with Image Quant LAS 4000 mini (GE Healthcare, USA). To assess equal loading of protein, the membranes were stripped and reprobed for β-actin (diluted 1: 1000; Affinity Biosciences).

Content and stability analysis by ELISA

ELISA was performed to analyze the amounts of BQTX in the submaxillary glands. Five different concentrations of BQTX standard (0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μg/ml) were used. In total, 100 mg of shrew submaxillary gland was homogenized in 2 ml of RIPA buffer (Sigma, USA) to extract proteins. The supernatant was then used for ELISA. BQTX stability analysis in mice was also tested by ELISA. After injection of 2 mg of BQTX into the mouse tail vein, blood was drawn from the tail at 0.5, 3, 5, 11, 17, 32, and 67 h. Plasma was collected by centrifugation at 3 000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C, and 1 μl of plasma was then used for ELISA.

Effects of BQTX on proteases

The effects of BQTX on proteases associated with blood and the digestive system, including trypsin, elastase, plasmin, thrombin, activated factor XII (FXIIa), kallikrein, activated factor XI (FXIa), activated factor X (FXa), urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), cathepsin, and chymotrypsin, were tested using corresponding chromogenic substrates. The testing enzyme was incubated with different concentrations of BQTX in 60 μl of 50 mM Tris-buffer (pH 7.4) for 5 min at 37 °C, and then a certain concentration of chromogenic substrate was added. Absorbance was monitored at 405 nm immediately and the kinetic curve was recorded using an enzyme-labeled instrument (Epoch BioTek, USA) for 30 min. Bovine pancreas trypsin, elastase, chymotrypsin, uPA, and cathepsin were obtained from Sigma (USA) and the enzyme concentration was 400 nM. The corresponding chromogenic substrates (Sigma, USA) were Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide dihydrochloride for trypsin, N-methoxysuccinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val-p-nitroanilide for elastase, N-succinyl-Gly-Gly-Phe-p-nitroanilide for chymotrypsin, Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide dihydrochloride for uPA, and Z-Arg-Arg-pNA for cathepsin. The concentration of all substrates in the reactions was 0.2 mM. The concentrations used for plasmin, kallikrein, FXIa, and FXa (Enzyme Research Laboratory, USA) were 400, 400, 400, and 10 nM, respectively, and the corresponding chromogenic substrates were Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide dihydrochloride (Sigma, USA), H–D-Pro-Phe-Arg-pNA·2HCl (Hyphen Biomed, France), H–D-Pro-Phe-Arg-pNA·2HCl (Hyphen Biomed, France), and CH3OCO-D-CHA-Gly-Arg-pNA-AcOH (Sigma, USA), respectively. The concentration of all three substrates in the reaction was 0.2 mM. Human thrombin (Sigma, USA, 10 nM) and FXIIa (Enzyme Research Laboratories, USA, 10 nM) were reacted with 0.2 mM H–D-Pro-Phe-Arg-pNA·2HCl (Hyphen Biomed, France) and H–D-Phe-Pip-Arg-pNa·2HCl (Hyphen Biomed, France), respectively. A Dixon plot curve was used to calculate the inhibition constants (Ki) of BQTX to inhibit the proteases [29]. The effects of BQTX on the hydrolytic abilities of plasmin and FXIIa on their natural substrates were assayed by SDS-PAGE. The natural substrates (20 μg of fibrinogen for plasmin and 10 μg of prekallikrein for FXIIa) were incubated with plasmin (0.1 NIH units) or FXIIa (0.01 NIH units) in 40 μl of Tris–HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) with different concentrations of BQTX (0, 40, 200, and 1 000 nM for plasmin and 0, 100 and 500 nM for FXIIa). After 30 min of incubation at 37 °C, all reactions were applied to 12% SDS-PAGE and the production of degradation products (DP) and height chain of kallikrein (HC) were quantified using ImageJ software. The effects of BQTX on the ability of thrombin to hydrolyze its natural substrate fibrinogen to produce fibrinopeptides A and B were analyzed by RP-HPLC. Human thrombin (0.1 NIH units) in 40 μl of Tris–HCl (25 mM, pH 7.4) was incubated with 500 μl of 10 mg/ml fibrinogen in Tris–HCl (50 mM, pH 7.8) containing 0.15 M NaCl with different concentrations of BQTX (0, 40, 200, and 1 000 nM). After incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, 500 μl of 20% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to stop the reaction and the mixture was centrifuged at 37 °C and 12 000 rpm for 10 min to precipitate the insoluble protein. Supernatant aliquots (700 μl) were then used for RP-HPLC analysis. The elution system consisted of solvent A (0.025 M ammonium acetate, pH 6.0) and solvent B (50% acetonitrile in 0.05 M ammonium acetate, pH 6.0), using a linear gradient of 0–100% solvent B over 100 min. The release of fibrinopeptides A and B was quantified by calculating the corresponding eluted peak areas on a C18 column (5 × 300 mm).

Interaction assays between BQTX and plasmin, FXIIa, and thrombin by surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

BIAcore 2000 (GE Healthcare, USA) was used to analyze the interactions between BQTX and plasmin, FXIIa, and thrombin. The BQTX protein was coupled with a CM5 sensor chip (GE, USA). BQTX was diluted to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml by 200 μl of sodium acetate (10 mM, pH 5). The target response unit (RU) was set to 2 000. The BQTX solution was flowed across the activated surface of the CM5 sensor chip by N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 1-ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl] carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. The remaining activated sites on the CM5 sensor chip were blocked by 75 μl of ethanolamine (1 M, pH 8.5). A series of plasmin, FXIIa, or/and thrombin concentrations were applied to analyze their interactions with BQTX on the surface of the CM5 sensor chip at a flow rate of 10 μl/min. The dissociation constant (KD) for binding as well as the association (Ka) and dissociation (Kd) rate constants were determined by the BIA evaluation program (GE Healthcare, USA).

Molecular docking

BQTX was docked into the exosite I of human thrombin. The human thrombin model was homologically constructed from known structures (PDB ID: 4NZQ). With the assistance of another two complex structures (PDB ID: 1A2C and 1HAH), the binding site was locally placed for further docking processes. Based on primary and secondary structure analysis of BQTX D1 and 2, the three-dimensional structures of BQTX D1 and 2 were developed by homology modeling methods. The above models were optimized by short molecular dynamics to eliminate steric clashes by side-chain packing. The modified BQTX D1 and 2 models were docked into exosite I site of human thrombin by the alignment of these structures. The docking processes were performed with the standard pipeline protocol of Discovery Studio (v3.1). During the docking process, common parameters were used to obtain more accurate results and ZRank scored the top 2000 poses with a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) cutoff of 10.0 Angstroms.

Effects of BQTX on blood coagulation

Healthy human plasma samples (ten healthy volunteers, half male and half female, aged 26.4 ± 2.6 years) were collected with informed consent from participants prior to the study from the Kunming Blood Center, Yunnan, China. All the experimental protocols were approved by the institutional Review Board of the Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (SYXK-2014-0007). Aggregation experiments were performed as described previously [30]. Briefly, washed platelets were resuspended in Tyrode’s buffer (145 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM D-glucose, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) with or without the addition of 40 nM thrombin. After 5 min of incubation at 37 °C with various concentrations of BQTX, platelet aggregation was initiated by the addition of an agonist and measured in an aggregometer [31] (LBY-NJ4, Techlink, Beijing). To test plasma recalcification, 20 μl of plasma was incubated with BQTX (0, 40, 200, or 1 000 nM) in 60 μl of HEPES buffer (20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) for 10 min. Then, 60 μl of 25 mM CaCl2 preheated at 37 °C for 10 min was added and clotting was monitored at 650 nm. Clotting time was calculated by measuring the time to half maximal increase in absorbance. The activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) and prothrombin time (PT) kits were purchased from the Jianchen Biology Company (Nanjing, China). For the APTT assay, 50 μl of APTT reagent was incubated with 50 μl of plasma with BQTX (0, 125, 250, or 500 nM) at 37 °C. After 3 min incubation, 50 μl of CaCl2 (25 mM) preheated at 37 °C for 5 min was added and clotting time was monitored at 405 nm. For the PT test, 50 μl of plasma was incubated for 3 min with different concentrations of BQTX (0, 125, 250 or 500 nM) at 37 °C, with 100 μl of PT reagent (preheated at 37 °C for 15 min) then added and clotting time monitored at 405 nm.

Bleeding time measurement

Adult BALB/c mice (male, 22–25 g) were injected with BQTX (0.4, 0.2, and 0.1 mg/kg), saline (0.9% sodium chloride solution), or 6-aminocaproic acid (6-aa, 0.4 mg/kg) via the tail vein. At 30 min after injection, the mouse tails were transected at 2 mm from the tip and vertically immersed in saline at 37 °C. The time when continuous blood flow ceased was measured within a maximum observation time of 10 min [32].

Mouse-tail thrombosis model induced by carrageen

Adult BALB/c mice (male, 22–25 g) were injected with BQTX (0.4, 0.2, and 0.1 mg/kg), saline, or 6-aa (0.4 mg/kg) via the tail vein. The same volumes of saline and 6-aa were used as blank and positive controls, respectively. At 30 min after injection, the mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 0.25 ml of 1% carrageenan (Type I, SIGMA, USA), and were then maintained at 17 °C. The thrombosis region lengths in the tails were measured and photographed at 24 h after the carrageenan injection. Thrombosis formation in the paws was also recorded, with apparent thrombosis formation defined as the grayscale change in the paw. ImageJ (NIH, USA) software was used to analyze grayscale values.

FeCl3-induced carotid artery thrombus formation

Adult C57BL/6 J mice (male, 22–25 g) were anaesthetized with 2.0% isoflurane. Their core body temperature was maintained at 37 °C during surgery. BQTX (0.4, 0.2, and 0.1 mg/kg), saline, or 6-aa (0.4 mg/kg) was injected into the mice via the tail vein. At 30 min after injection, the left common carotid arteries were exposed by cervical incision and separated from the adherent tissue and vagus nerve. Thrombosis was induced by applying a piece (2 × 2 mm) of filter paper pre-soaked with 10% (w/v) FeCl3 solution to the exposed carotid artery. Blood flow in the carotid arteries of all groups was measured by laser speckle perfusion imaging (PeriCam PSI, HR, Sweden) at 4 and 8 min after FeCl3 induction. The perfusion unit of the region of interest (ROI) was also recorded to quantify blood flow changes.

Effects of BQTX on rhesus macaque blood pressure

Adult rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) (male, 7.5–8.5 kg) were purchased from the Kunming Primate Research Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Yunnan, China. The macaques were housed under controlled temperature (25 °C) and light conditions (12-h light/dark cycle, lights on at 08:00) and were provided with standard laboratory monkey chow supplemented with fresh fruit and water. Prior to the study, the macaques were taken from their home cages and transported to primate restraint chairs in a surgery room. The monkeys had been previously trained to be quiet on the restraint chair. Arterial blood pressure of the conscious macaques was directly and continuously monitored using a calibrated pressure transducer connected to a multi-parameter physiological monitor (Advisor V9204; Surgivet, Waukesha, WI, USA). After ~ 30 min of acclimation, systolic and diastolic blood pressure were continuously recorded for 20–30 min before and 100–120 min after the animals were intravenously administered with different concentrations of BQTX (dissolved in 500 ml of 0.9% sodium chloride solution) in the right forearm. All experiments complied with national legislation and were approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (SMKX-2016013).

Formalin-induced paw licking model

Adult BALB/c mice (male, 22–25 g) were injected with BQTX (5, 1, and 0.2 mg/ml), saline, or morphine (0.2 mg/kg) through the tail vein. At 30 min after injection, all mice were injected with 20 μl of 5% (v/v) formalin in the plantar surface of the right hind paw and placed individually in open cages. Time spent licking the right hind paw in phase I (0–5 min) and phase II (15–30 min) was recorded by a digital video camera [33].

Abdominal writhing model induced by acetic acid

Adult BALB/c mice (male, 22–25 g) were injected through the tail vein with 5, 1, and 0.2 mg/kg BQTX or 0.2 mg/kg morphine. After 30 min, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.1 ml/10 g body weight of acetic acid (concentration of 0.6% (v/v)) and immediately placed in open cages. Abdominal constrictions were recorded by digital video camera [33].

Thermal pain model

A tail withdrawal mouse model was used to determine the effect of BQTX on reaction time to a thermal stimulus. A photothermal pain detector (YLS-12A, China) was applied to measure tail withdrawal latency, i.e., time taken to withdraw the tail from a light beam. Mice with a tail withdrawal latency of 4–8 s were selected for this experiment. Before photothermal heating of the tail, the mice were injected with BQTX (5, 1, and 0.2 mg/kg), morphine (0.2 mg/kg), or saline in the tail vein. A light beam from the detector was focused on the middle of the tail and the time to tail-flick was recorded [33].

Statistical analyses

Data visualization and statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism software. The data were presented as means ± Standard Deviation. Differences in the results of the two groups were evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Dunnett’s test. The differences with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 were considered statistically significant.

Results

BQTX characterization and tissue distribution

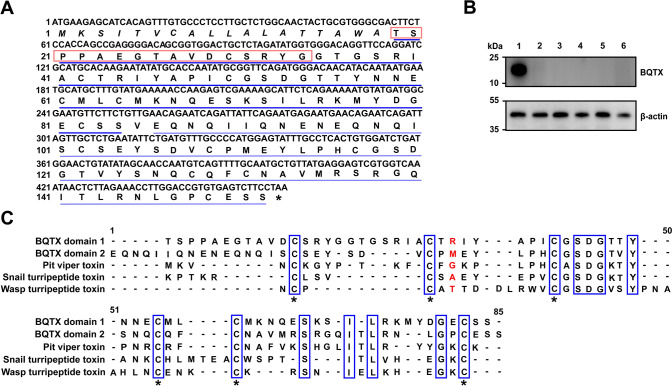

A 14-kDa protein (named BQTX), which showed potentiating activity on thrombin, was purified from the submaxillary glands of B. quadraticauda, as illustrated in Fig. S2A–E. Based on mass spectrometry, the molecular weight of native BQTX was 14 746.7 Da (Fig. S2E). Partial amino acid (aa) sequences were determined using Edman degradation. The cDNA encoding a BQTX precursor of 152 aa residues, including an 18-aa predicted signal peptide and mature BQTX, was cloned from the cDNA library of the B. quadraticauda submaxillary gland (Fig. 1A). Western blot analysis indicated that BQTX was specifically distributed in the submaxillary gland, but not in other tissues, such as the heart, liver, lung, muscle, and skin (Fig. 1B). Based on BLAST search, BQTX exhibited similarities with Kazal-type serine protease inhibitor toxins identified from the venoms of snake, wasp, and snail [34–36], notably the same cysteine motif (Fig. 1C). Recombinant BQTX, which showed similar functions as native BQTX, was expressed in E. coli and then purified (Fig. S3A–D). Using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), the amount of BQTX in the submaxillary gland was 7–10 μg/mg (Fig. S3E).

Fig. 1.

Amino acid (aa) sequence and tissue distribution of BQTX. A cDNA sequence encoding BQTX precursor. Signal peptide is shown in italics. Amino acid sequences of N-terminal and interior fragments, determined by automated Edman degradation, are boxed. Two domains of BQTX are underlined. B Tissue distribution of BQTX was determined by western blot analysis. Lane 1, submaxillary gland; Lane 2, heart; Lane 3, liver; Lane 4, lung; Lane 5, skin; Lane 6, muscle. To assess equal loading of protein, the membranes were stripped and reprobed for β-actin. C Sequence alignment of domains 1 and 2 of BQTX with serine protease inhibitor toxins from snake, wasp, and snail venom. Identical residues are highlighted in blue rectangles. The P1 residues are shown in red. *cysteine

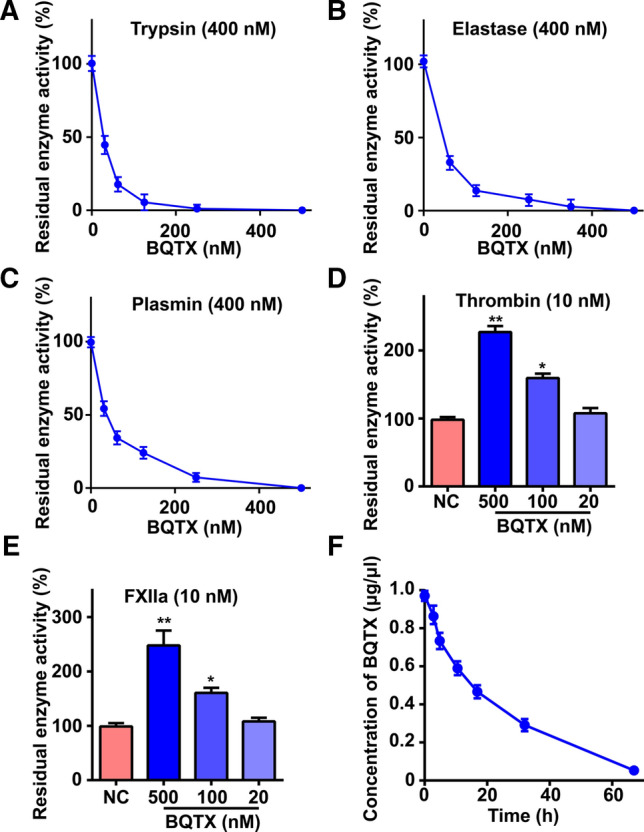

BQTX inhibits plasmin, elastase, and trypsin and potentiates thrombin and factor XIIa

The effects of BQTX on serine proteases related to blood coagulation and fibrinolysis were investigated. BQTX showed a strong inhibitory ability against trypsin (Fig. 2A), elastase (Fig. 2B), and plasmin (Fig. 2C), with inhibition constants (Ki) of 63.18, 24.56, and 72.15 nM, respectively (Fig. S4A–C). In contrast, BQTX significantly potentiated thrombin and activated factor XII (FXIIa) activity in a dose-dependent manner. At a concentration of 0.5 μM, BQTX increased the enzymatic activity of thrombin and FXIIa by 1.5- and 1.8-fold, respectively (Fig. 2D, E). BQTX had no effect on kallikrein, activated factor XI (FXIa), activated factor X (FXa), urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA), cathepsin, or chymotrypsin (Fig. S4D). Coincident with its strong inhibitory abilities against proteases, BQTX showed high stability in vivo, with a 16-h half-life in plasma (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Effects of BQTX on serine proteases and its stability in plasma. A–E Effects of BQTX on hydrolytic ability of trypsin, elastase, plasmin, thrombin, and FXIIa were determined using synthetic substrates. Testing enzyme was incubated with different concentrations of BQTX in 60 μl of Tris-buffer for 5 min at 37 °C, and then a certain concentration of chromogenic substrate was added. Absorbance was monitored at 405 nm immediately. Data represent mean ± SD of five independent experiments, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test (D and E). F BQTX showed high stability in vivo. BQTX (2 mg) was injected into mouse tail vein. Blood was drawn from tail every 2 h, and plasma was collected and used for ELISA

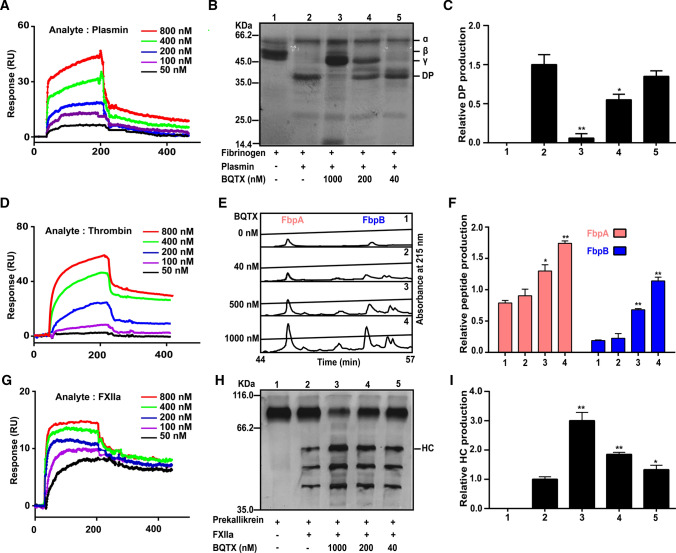

BQTX binds to plasmin, thrombin, and FXIIa with high affinity

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) was used to analyze the interactions of BQTX with plasmin, thrombin, and FXIIa. Results showed that BQTX could directly bind to plasmin, thrombin, and FXIIa (Fig. 3A, D, and G). The association (Ka), dissociation (Kd), and dissociation constant (KD) values for BQTX-plasmin interactions were 2.19 × 105 M−1 s−1, 2.6 × 10−3 s−1, and 11.9 nM, respectively, while those for BQTX-thrombin interactions were 2.01 × 104 M−1 s−1, 1.15 × 10−3 s−1, and 57 nM, respectively. BQTX showed the highest affinity with FXIIa, with Ka, Kd, and KD values of 2.01 × 105 M−1 s−1, 9.03 × 10−4 s−1, and 4.49 nM, respectively. BQTX significantly inhibited the hydrolysis of plasmin on fibrinogen (Fig. 3B, C), which is a natural substrate of plasmin in the physiological environment. At a concentration of 1 μM, BQTX almost completely blocked the hydrolysis of plasmin on fibrinogen. Notably, BQTX potentiated the enzymatic activities of thrombin and FXIIa by enhancing the hydrolytic ability of the enzymes on natural substrates (fibrinogen and prekallikrein) (Fig. 3E, F, H, and I). At a concentration of 0.2 μM, BQTX resulted in a two-fold increase the hydrolytic ability of thrombin and FXIIa on fibrinogen and prekallikrein, respectively.

Fig. 3.

BQTX directly interacts with plasmin, thrombin, and FXIIa, and inhibits/potentiates hydrolytic abilities of proteases. A BQTX was immobilized on CM5 sensor chip by covalent bond. Plasmin (30 μl) diluted with HEPES-EB buffer (pH 7.4) was applied to surface of CM5 with a flow rate of 10 μl/min. B Representative SDS-PAGE analysis of fibrinogen hydrolysis by plasmin. Lane 1, 20 μg of fibrinogen; lane 2, 20 μg of fibrinogen was incubated with 0.1 NIH units of plasmin in Tris–HCl (50 mM, pH 7.4) for 30 min; lane 3–5: 20 μg of fibrinogen was incubated with 0.1 NIH units of plasmin and 1 000, 200, and 40 nM BQTX for 30 min in Tris–HCl (50 mM, pH 7.4), respectively. C Quantification of release of degradation products (DP) of ‘B’. D SPR analysis of interaction between BQTX and thrombin. E Representative RP-HPLC analysis of release of fibrinopeptide A and fibrinopeptide B (FbpA and FbpB). Panel 1, 40 μl of human thrombin (0.1 NIH units) in 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4) was added to 500 μl of 10 mg/ml fibrinogen in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.8) containing 0.15 M NaCl. After incubation for 30 min at 37 °C, 500 μl of 20% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) was added to stop reaction, with mixture then centrifuged 4 °C for 10 min at 12 000 rpm to precipitate insoluble protein. A 700-μl aliquot of supernatant was injected into RP-HPLC C18 column. 1, 2, 3, and 4 indicate RP-HPLC analysis after treatment with 0, 40, 200, and 1 000 nM BQTX, respectively. F Quantification of release of FbpA and FbpB of ‘E’. G SPR analysis of interaction between BQTX and FXII. H Representative SDS-PAGE analysis of prekallikrein hydrolysis by FXIIa. Lane 1: 10 μg of prekallikrein; lane 2: 10 μg of prekallikrein was incubated with 0.01 NIH units of FXIIa in Tris–HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) for 30 min; lane 3, 4 and 5: 10 μg of prekallikrein was incubated with 0.01 NIH units of FXIIa and 1 000, 200, and 40 nM BQTX in Tris–HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) for 30 min, respectively. I Quantification of release of height chain of kallikrein (HC) of ‘H’. Data represent mean ± SD of five independent experiments, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test (C, F, and I)

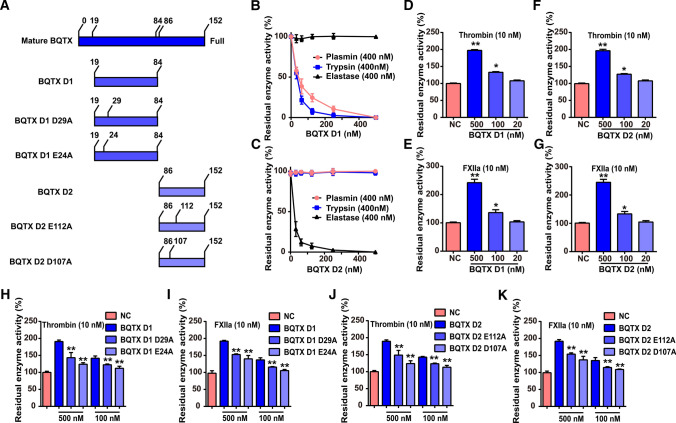

Two Kazal domains of BQTX specifically target different serine proteases

The two Kazal-structure domains (D1 and D2) of BQTX (Fig. 4A) were recombinantly expressed in E. coli and purified (Fig. S5). BQTX D1 showed a strong inhibitory ability against plasmin and trypsin (Fig. 4B), while BQTX D2 only inhibited elastase without affecting plasmin and trypsin (Fig. 4C). Both BQTX D1 and D2 potentiated the enzymatic activities of thrombin and FXIIa (Fig. 4D–G) but had no effect on kallikrein, FXIa, FXa, uPA, chymotrypsin, or cathepsin (Fig. S6A, B). To explore the key sites of BQTX D1 and D2 on thrombin and FXIIa activity, two BQTX D1 and D2 mutation sites were designed and expressed according to protein docking models (Figs. 4A, S7 and S8). Respectively, Glu24 and Asp29 in BQTX D1 were mutated into Ala (BQTX D1 E24A and BQTX D1 D29A). Asp107 and Glu112 in BQTX D2 were mutated into A (BQTX D2 D107A and E112A). The BQTX D1 E24A and BQTX D2 D107A mutants significantly reduced the potentiation of the enzymatic activities of thrombin and FXIIa (Fig. 4H–K), thus suggesting key roles of Glu24 and Asp107 in BQTX-thrombin/FXIIa interactions.

Fig. 4.

Two Kazal domains of BQTX specifically target different serine proteases. A Schematic of mature BQTX, BQTX domain 1 (D1), BQTX domain 1 29th D mutated to A (D1 D29A), BQTX domain 1 24th E mutated to A (D1 E24A), BQTX domain 2 (D2), BQTX domain 2 112th E mutated to A (D2 E112A), and BQTX domain 2 107th D mutated to A (D2 D107A). B BQTX D1 showed inhibitory ability against plasmin and trypsin. (C) BQTX D2 inhibited elastase without affecting plasmin and trypsin. D, E BQTX D1 enhanced hydrolytic ability of thrombin and FXIIa. F, G BQTX D2 enhanced hydrolytic ability of thrombin and FXIIa. H, I Effects of BQTX D1 mutants on hydrolytic ability of thrombin and FXIIa were determined. J, K Effects of BQTX D2 mutants on hydrolytic ability of thrombin and FXIIa were determined. Data represent mean ± SD of six independent experiments, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test (D–K)

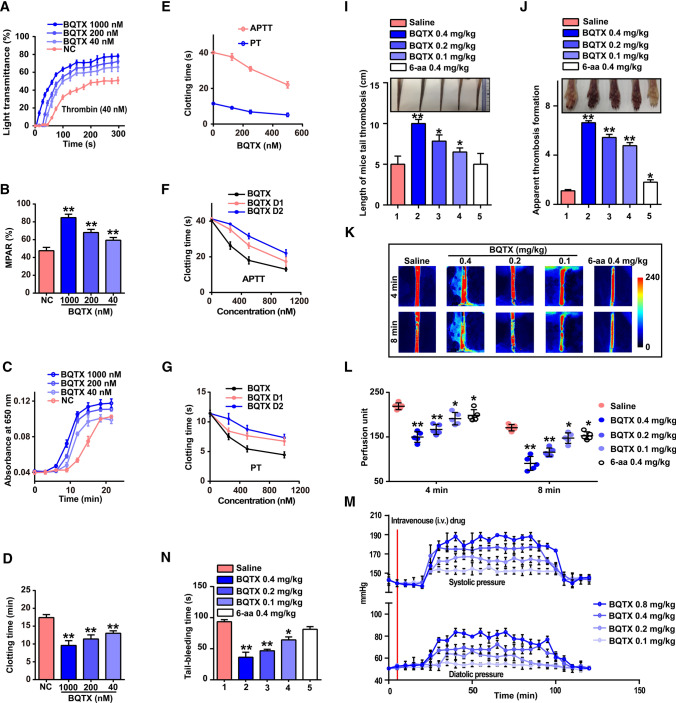

BQTX induces acute thrombosis

Given the ability of BQTX to potentiate thrombin and FXIIa (Fig. 2D, E), we considered that it may promote coagulation. As illustrated in Fig. 5A, B, BQTX enhanced the ability of thrombin to induce platelet aggregation, further confirming its potentiation of thrombin. BQTX dose-dependently reduced recalcification and clotting times (Fig. 5C, D). This toxin and its two Kazal domains (BQTX D1 and D2) dose-dependently reduced activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) and prothrombin time (PT) in human plasma (Fig. 5E–G), indicating their procoagulant functions. In mice, BQTX reduced tail bleeding time in a dose-dependent manner, with reductions of 35%, 49%, and 63% at doses of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 mg/kg, respectively (Fig. 5H). In the tail thrombosis model (induced by carrageen), BQTX treatment at doses of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4 mg/kg increased tail thrombosis by 30%, 56%, and 100%, respectively (Fig. 5I), while paw thrombosis increased by 3.75-, 4.45-, and 5.65-fold, respectively (Fig. 5J). Carotid artery blood flow in mice was significantly decreased by BQTX. Specifically, after 0.4 mg/kg BQTX administration for 4 and 8 min, blood flow decreased by 35% and 60%, respectively, implying rapid enhancement in thrombus formation in vivo (Fig. 5K, L). Overall, BQTX showed a stronger procoagulant effect than the plasminogen activation inhibitor 6-aminocaproic acid (6-aa) [37].

Fig. 5.

BQTX induces acute thrombosis and persistent hypertension. A BQTX enhanced platelet aggregation induced by thrombin. Washed human platelets were pretreated with BQTX (1 000, 200, and 40 nM) for 5 min and then stimulated with thrombin (40 nM) for 5 min. n = 8 per group. B Maximum platelet aggregation rate (MPAR) of ‘A’ was calculated. C BQTX dose-dependently reduced plasma recalcification time. Plasma (20 μl) was pretreated with BQTX (0, 40, 200, or 1 000 nM) in 60 μl of HEPES buffer for 10 min. Then, 60 μl of 25 mM CaCl2 preheated at 37 °C for 10 min was added. n = 10 per group. D Clotting time of ‘C’ was calculated by measuring time to half maximal increase in absorbance. E BQTX dose-dependently reduced activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) and prothrombin time (PT), n = 8 per group. F, G BQTX D1 and BQTX D2 dose-dependently reduced APTT and PT, n = 8 per group. Data represent mean ± SD of five independent experiments, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test (B and D). H BQTX decreased mouse (BALB/c) tail bleeding time. At 20 min after BQTX (0.4, 0.2, and 0.1 mg/kg), 6-aa (0.4 mg/kg), or saline administration, mouse tails were transected at approximately 2 mm from tail tip. Bleeding tails were immediately immersed in normal saline, and time from initiation to termination of bleeding was recorded as bleeding time. n = 6 per group. I, J BQTX aggravated mouse (BALB/c) tail and paw thrombosis induced by carrageen. Mice received (i.v.) BQTX (0.4, 0.2, and 0.1 mg/kg), 6-aa (0.2 mg/kg), or saline. At 30 min after injection, mice were administered (i.p.) 0.25 ml of 1% carrageenan, then maintained at 17 °C. Thrombosis region lengths in tails and grayscale change in paws were measured and photographed at 24 h after carrageenan injection. n = 6 per group. K, L Effects of BQTX on FeCl3-induced carotid artery thrombus formation in C57BL/6J mice. Representative images of carotid artery blood flow (top) and quantification (bottom) are shown. Red: blood flow; Blue and black area: background; Color bar on right indicates perfusion unit scale (0–240). Left common carotid arteries were exposed by cervical incision and separated from adherent tissue and vagus nerve. Injury was induced by contact with a cross-section of a filter paper strip (2 × 2 mm) saturated with 10% FeCl3 (W/V) for 90 s. n = 5 per group. Animal experiments were repeated three times independently. M Effects of BQTX on blood pressure in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). After macaques were acclimated for 30 min, both systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels were continuously recorded for 20–30 min before and 100–120 min after intravenous administration of different concentrations of BQTX in right forearm, n = 3 per group. Data represent mean ± SD, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test (H, I, J, and L)

BQTX induces persistent hypertension and hypokinesia

As illustrated in Fig. 5M, an intravenous (i.v.) injection of BQTX increased rhesus macaque blood pressure. After administration of 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 mg/kg BQTX, systolic pressure increased by 11, 19, 31, and 40 mmHg, and diastolic pressure increased by 2, 12, 20, and 25 mmHg, respectively. The increase in blood pressure started 15 min after BQTX administration and persisted for ~ 100 min. Most mice administered with BQTX showed significant hypokinesia, which likely resulted from persistent hypertension and acute thrombosis induced by the toxin.

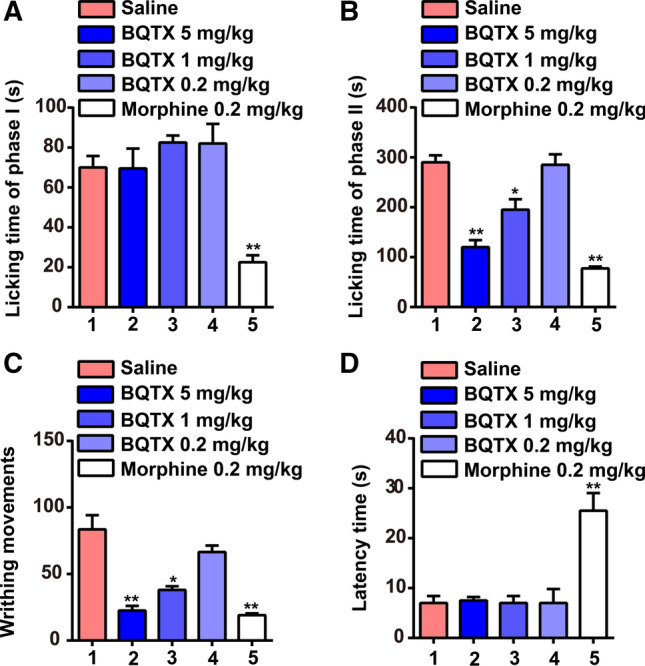

BQTX exerts significant analgesic functions

As BQTX demonstrated a strong inhibitory ability against elastase, and inhibitors of elastase display analgesic functions [38], we further investigated the analgesic abilities of BQTX using mouse models. A plantar subcutaneous injection of 5% formalin in the mice induced nociceptive behavior, which occurred in two phases. Phase I occurred within the first 10 min of injection and disappeared almost completely by 5–10 min (Fig. 6A). In phase II (late phase), the nociceptive response reoccurred 10–30 min after the formalin injection (Fig. 6B). However, BQTX treatment significantly attenuated the nociceptive behaviors during phase II in the formalin-induced paw licking mouse model but had no effect during phase I. Nociceptive behaviors during phase II decreased by 59%, 33%, and 2% under doses of 5, 1, and 0.2 mg/kg of BQTX, respectively (Fig. 6B). In addition, an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 0.1 ml/10 g body weight of a 1.5% (v/v) solution of acetic acid induced a writhing response in mice between 0 and 30 min. However, BQTX administration at doses of 5, 1, and 0.2 mg/kg decreased writhing movements by 76%, 54%, and 20%, respectively (Fig. 6C). BQTX administration did not alter thermal stimulus reaction time during 90 min of observation (Fig. 6D).

Fig. 6.

BQTX shows analgesic effects. A, B Pretreatment with BQTX (5 and 1 mg/kg) selectively attenuated mouse (BALB/c) nociceptive behavior in phase II (10–30 min) following right hind paw injection of 20 μl of 5% formalin. Formalin was injected 30 min after BQTX (5, 1, and 0.2 mg/kg), morphine (0.2 mg/kg), or saline pretreatment. Phase II licking time following BQTX treatment decreased significantly compared with that in saline-pretreated mice. Phase I (0–10 min) licking time did not differ significantly from that observed in corresponding saline group. n = 5 per group. C BQTX reduced writhing response to acetic acid in BALB/c mice. Number of writhes was counted between 0 and 30 min after i.p. injection of 0.1 ml/10 g body weight of acetic acid (concentration of 0.6% (v/v)). Mice received an injection (i.v.) of BQTX (5, 1, and 0.2 mg/kg), morphine (0.2 mg/kg), or saline 30 min before acetic acid injection. n = 5 per group. D Effects of BQTX and morphine on reaction time to thermal stimulus in BALB/c mice. BQTX had no effect on thermal pain. Mice were pretreated (i.v.) with saline, morphine (0.2 mg/kg), or BQTX (5, 1, and 0.2 mg/kg), with reaction times measured 30 min after injection. n = 5 per group. Animal experiments were repeated three times independently. Data represent mean ± SD, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test (A–D)

Discussion

Although shrews contain oral venom systems, little is known about the composition or toxic mechanisms of the venom. To the best of our knowledge, the only previously identified shrew toxin is BLTX, a kallikrein-like protease obtained from the venom of the northern short-tailed shrew, which likely produces toxic effects by promoting kinin production [16]. Here, we identified a double-knot protease inhibitor toxin (BQTX) with two Kazal-type domains, which was specifically distributed in the submaxillary gland of the B. quadraticauda shrew. By acting as a thrombin and FXIIa potentiator and plasmin inhibitor, BQTX exerted toxic effects on circulation disorder and hypertension. In addition, the toxin showed strong analgesic effects by inhibiting elastase. Importantly, due to its high stability in plasma, with a 16-h half-life, BQTX likely helps shrews paralyze or immobilize prey for hoarding and later consumption.

BQTX showed high homology with Kazal-type serine protease inhibitor toxins found in the other venom of other animals, such as snakes, wasps, and snails, implying an evolutionary correlation with non-mammalian venomous toxins (Fig. 1C). P1 residue which is located at the second position behind the second cysteine residue of the Kazal domain contributes mainly to the inhibitory specificity [39–42]. BQTX contained two domains with a typical Kazal structure, i.e., two different P1 sites (Arg and Met), suggesting it may target different serine proteases. Indeed, BQTX showed strong inhibitory abilities against multiple serine proteases, including trypsin, elastase, and plasmin (Fig. 2A–C), contributing to its high stability in vivo (Fig. 2F). Notably, BQTX showed a strong inhibitory ability against plasmin, with a Ki value of 10–9 M (Fig. S4C). Several plasmin inhibitors from natural resources have been reported, including TSPI from Oxyuranus scutellatus [43], Textilinin-1 from Pseudonaja textilis [44], DrKIn-II from Daboia russelii [45], AvKTI from Araneus ventricosus [46], Bi-KTI from the Bombus ignites [47], and bdellins and bdellastasin from Hirudo medicinalis [48]. However, most of these plasmin inhibitors are Kunitz type. Kazal protease inhibitors with plasmin-inhibiting activity are rare. As far as we know, BQTX is the first Kazal-type inhibitor identified from vertebrate venom to inhibit plasmin.

Most protease inhibitors from bloodsucking animals inhibit coagulation to ensure blood flow at the feeding site by acting as inhibitors of coagulation factors, such as thrombin, FXIa, FXa, and FXIIa [10, 48]. Our results showed that BQTX potentiated the enzymatic activity of thrombin and FXIIa to promote coagulation and hypertension (Figs. 2 and 5). Exosite I, the site where thrombin recognizes fibrinogen, is rich in alkaline amino acids and close to the substrate-binding pocket [49]. Here, the docking model showed that BQTX interacted with the exosite I region of thrombin and the exosite I-like region of FXIIa to reduce the steric hindrance of the substrate pocket, making substrate entry easier. The potentiation of thrombin and FXIIa was reversed by mutating the key residues of BQTX that interact with the exosite I or exosite I-like regions (Fig. 4). We reported a similar mechanism in previous studies showing that transferrin potentiates the enzymatic activity of thrombin and FXIIa by combining the exosite I of thrombin and exosite I-like region of FXIIa [50, 51]. Recent research has also shown that secreted modular calcium-binding protein 1 (SMOC1) has a Kazal domain that binds to thrombin and potentiates its activity [52]. Neutrophil elastase is associated with pain and its inhibitors are considered as painkillers [38]. As an elastase inhibitor, BQTX showed a strong ability to inhibit pain-related behaviors in several animal models (Fig. 6B, C). Thus, BQTX may suppress prey reactions to be undetectable for successful predation. Some preys are larger than shrews [21, 24, 53–55] and take longer to be overpowered. Obviously, longer-lasting intoxication effects can facilitate shrew foraging behavior. Given its high stability and half-life in vivo, BQTX may extend the intoxication effects of the shrew venom to maximize foraging profit.

In conclusion, B. quadraticauda venom induced blood hypercoagulation and hypertension by inhibiting the fibrinolytic system and promoting the coagulation system. These results enhance our current understanding of mammalian venom and its underlying mechanisms of action. Importantly, the discovery of the BQTX toxin, which induced acute thrombosis and persistent hypotension, while maintaining high stability in blood to maximize foraging profit, demonstrates that B. quadraticauda is a potentially dangerous mammal. Thus, greater attention should be paid to this species, especially by thrombotic or hypertensive individuals.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge English language support from Dr. Peter Muiruri Kamau and all the participants of this study.

Author contributions

ZL, XT, WC, XJ, ZD, LL, and XH performed research; XJ, ZC, KH, and QL Collected Blarinella quadraticauda specimens and analyzed toxicological effects; W.C. provided B. quadraticauda bite case report; RL, XT, ZL, MR, and PK wrote the paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (31930015, 32100907, 81770464, and 32070443), Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB31000000 and KFJ-STS-SCYD-304), Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (HZ2021020), and Yunnan Province (2019FA006, 2019FB127, 2019ZF003, and 202003AD150008), as well as the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2018YFA0801403).

Data availability

Data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All animal-based experiments conformed to the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. All experiments complied with national legislation and were approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (SYXK-2014-0007 and SMKX-2016013).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the image in Fig. S1C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhiyi Liao, Xiaopeng Tang, Wenlin Chen and Xuelong Jiang have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Fox RC, Scott CS. First evidence of a venom delivery apparatus in extinct mammals. Nature. 2006;435(7045):1091–1093. doi: 10.1038/nature03646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rode-Margono J, Nekaris K. Cabinet of curiosities: venom systems and their ecological function in mammals, with a focus on primates. Toxins. 2015;7(7):2639–2658. doi: 10.3390/toxins7072639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ligabue-Braun R, Verli H. Venomous mammals: a review. Toxicon. 2012;59(7):680–695. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dufton MJ. Venomous mammals. Pharmacol Therapeut. 1992;53(2):199–215. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90009-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowen CV, Debay D. In Vivo detection of human TRPV6-rich tumors with anti-cancer peptides derived from soricidin. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e58866. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whittington CM, Papenfuss AT. Novel venom gene discovery in the platypus. Genome Biol. 2010;11(9):R95. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-9-r95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torres AM, Bansal P. Structure and antimicrobial activity of platypus ‘intermediate’ defensin-like peptide. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(9):1821–1826. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grow NB, Nekaris KAI. Does toxic defence in Nycticebus spp. relate to ectoparasites? The lethal effects of slow loris venom on arthropods. Toxicon. 2015;95(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nekaris KAI, Moore RS. Mad, bad and dangerous to know: the biochemistry, ecology and evolution of slow loris venom. J Venom Anim Toxins. 2013;19(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1678-9199-19-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma D, Mizurini DM. Desmolaris, a novel factor XIa anticoagulant from the salivary gland of the vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) inhibits inflammation and thrombosis in vivo. Blood. 2013;122(25):4094–4106. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-517474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Low D, Sunagar K. Dracula's children: molecular evolution of vampire bat venom. J Proteomics. 2013;89(26):95–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folins KE, Müller J. Canine grooves: morphology, function, and relevance to venom. J Vertebr Paleontol. 2007;27(2):547–551. doi: 10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[547:CGMFAR]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ariano-Sánchez D. Envenomation by a wild Guatemalan Beaded LizardHeloderma horridum charlesbogerti. Clin Toxicol. 2008;46(9):897–899. doi: 10.1080/15563650701733031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaila F, Kaila E. Evolution of venom across extant and extinct eulipotyphlans L’évolution du venin chez les eulipotyphles modernes et éteints. CR Palevol. 2013;12(7):531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.crpv.2013.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicholas RC, Daniel P. Solenodon genome reveals convergent evolution of venom in eulipotyphlan mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116(15):25745–25755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1906117116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kita M, Nakamura Y. Blarina toxin, a mammalian lethal venom from the short-tailed shrew Blarina brevicauda: Isolation and characterization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(20):7542–7547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402517101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kowalski K, Rychlik L. The role of venom in the hunting and hoarding of prey differing in body size by the Eurasian water shrew, Neomys fodiens. J Mammal. 2008;99(2):351–362. doi: 10.1093/jmammal/gyy013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kita M, Okumura Y. Purification and characterisation of blarinasin, a new tissue kallikrein-like protease from the short-tailed shrew Blarina brevicauda: comparative studies with blarina toxin. Biol Chem. 2005 doi: 10.1515/bc.2005.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Churchfield S. The natural history of shrews. Q Rev Biol. 1990;66(4):505–506. doi: 10.1086/417393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor JRE. Evolution of energetic strategies in shrews. In: Jan MW, editor. Evolution of shrews. 1. Mammal Research Institute: Bialowieza; 1998. pp. 309–346. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton WJ. The food of the soricidae. J Mammal. 1930;11(1):26–39. doi: 10.2307/1373782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hotopp KP. Land snails and soil calcium in central appalachian mountain forest. Southeastern Nat. 2002;1(1):27–44. doi: 10.1656/1528-7092(2002)001[0027:lsasci]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dehnel A. Aufspeicherung von Nahrungsvorräten durch Sorex araneus Linnaeus 1758; Gromadzenie zapasów pożywienia u Sorex araneus Linnaeus 1758. Acta Theriol. 1960;4:265–268. doi: 10.4098/AT.arch.60-14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin IG. Factors affecting food hoarding in the short-tailed shrew Blarina brevicauda. Mammalia. 1984;48(1):65–72. doi: 10.1515/mamm.1984.48.1.65. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rychlik L. Prey size, prey nutrition, and food handling by shrews of different body sizes. Behav Ecol. 2002;13(2):216–223. doi: 10.1093/beheco/13.2.216. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang XL, Wang YX. A review of the systematics and distribution of Asiatic short-tailed shrews, genus Blarinella (Mammalia: Soricidae) Mamm Biol. 2003;68(4):193–204. doi: 10.1078/1616-5047-00085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He K, Li YJ. A multi-locus phylogeny of Nectogalini shrews and influences of the paleoclimate on speciation and evolution. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2010;56(2):734–746. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin IG. Venom of the short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) as an insect immobilizing agent. J Mammal. 1982;5(1):189–192. doi: 10.2307/1380494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arinos M, Richardson M. Purification and properties of a coagulant thrombin-like enzyme from the venom of Bothrops leucurus. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2007;146(4):565–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Z, Lan G. A potent anti-thrombosis peptide (vasotab TY) from horsefly salivary glands. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;54(8):83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yue M, Luo D. Misshapen/NIK-related Kinase (MINK1) is involved in platelet function, hemostasis and thrombus formation. Blood. 2015;127(7):927–937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-07-659185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xia Q, Wang X. Inhibition of platelet aggregation by curdione from Curcuma wenyujin essential Oil. Thromb Res. 2012;130(3):409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang S, Xiao Y. Discovery of a selective NaV1.7 inhibitor from centipede venom with analgesic efficacy exceeding morphine in rodent pain models. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(43):17534–17539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306285110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fernández J, Gutiérrez J. Characterization of a novel snake venom component: Kazal-type inhibitor-like protein from the arboreal pitviper Bothriechis schlegelii. Biochimie. 2016;125:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watkins M, Hillyard DR. Genes expressed in a turrid venom duct: divergence and similarity to conotoxins. J Mol Evol. 2006;62(3):247–256. doi: 10.1007/s00239-005-0010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan Z, Fang Q. Insights into the venom composition and evolution of an endoparasitoid wasp by combining proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):19604. doi: 10.1038/srep19604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ablondi FB, Hagan JJ. Inhibition of plasmin, trypsin and the streptokinase-activated fibrinolytic system by 6-aminocaproic acid. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959;82(1):153–160. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vicuña L, Strochlic DE. The serine protease inhibitor SerpinA3N attenuates neuropathic pain by inhibiting T cell–derived leukocyte elastase. Nat Med. 2015;21(5):518–523. doi: 10.1038/nm.3852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bode W. Natural protein proteinase inhibitors and their interaction with proteinases. Eur J Biochem. 1992;204(2):433–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waisberg M, Mizurini DM. Plasmodium falciparum infection induces expression of a mosquito salivary protein (Agaphelin) that targets neutrophil function and inhibits thrombosis without impairing hemostasis. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(9):e1004338. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aaron M, LeBeau PS. Prostate-specific antigen is a "chymotrypsin-like" serine protease with unique P1 substrate specificity. Biochemistry. 2009;48(15):3490–3496. doi: 10.1021/bi9001858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng LS, Cao Y. SPINK6 promotes metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma via binding and activation of epithelial growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 2016;77(2):579–589. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pierre LS, Earl ST. Common evolution of waprin and kunitz-like toxin families in Australian venomous snakes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65(24):4039–4054. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8573-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viala VL, Hildebrand D. Venomics of the Australian eastern brown snake (Pseudonaja textilis): detection of new venom proteins and splicing variants. Toxicon. 2005;107:252–265. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng AC. Tsai IH (2014) Functional characterization of a slow and tight-binding inhibitor of plasmin isolated from Russell's viper venom. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 1840;1:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wan H, Lee KS. A spider-derived Kunitz-type serine protease inhibitor that acts as a plasmin inhibitor and an elastase inhibitor. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Choo YM, Lee KS. Antifibrinolytic Role of a Bee Venom Serine Protease Inhibitor That Acts as a Plasmin Inhibitor. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e32269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Söllner C, Mentele R, Eckerskorn C, Fritz H, Sommerhoff CP. Isolation and characterization of hirustasin, an antistasin-type serine-proteinase inhibitor from the medical leech Hirudo medicinalis. Eur J Biochem. 2010;219(3):937–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Myles T, Church FC. Role of thrombin anion-binding exosite-I in the formation of thrombin-serpin complexes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(47):31203–31208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang X, Zhang Z. Transferrin plays a central role in coagulation balance by interacting with clotting factors. Cell Res. 2020;30(2):119–132. doi: 10.1101/646075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang X, Fang M. Iron-deficiency and estrogen are associated with ischemic stroke by up-regulating transferrin to induce hypercoagulability. Cir Res. 2020;127(5):651–663. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.316453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lagos F, Elgheznawy A. Secreted modular calcium binding protein 1 binds/activates thrombin to account for platelet hyper-reactivity in diabetes. Blood. 2021;137(12):1641–1651. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020009405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robert EW. The short-tailed shrew and field mouse predation. J Mammal. 2008;25(4):359–364. doi: 10.2307/1374897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buchalczyk T, Pucek Z. Food storage of the European water shrew, Neomys fodiens (Pennant, 1771); Gromadzenie pokarmu przez rzsorka, Neomys fodiens (Pennant, 1771) Acta Theriol. 1963;7:376–379. doi: 10.4098/AT.arch.63-22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tomasi TE. Function of venom in the short-tailed shrew Blarina brevicauda. J Mammal. 1978;59(4):852–854. doi: 10.2307/1380150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request from the corresponding author.

Not applicable.