Abstract

It is widely assumed that as connective tissue, the intervertebral disc (IVD) plays a crucial role in providing flexibility for the spinal column. The disc is comprised of three distinct tissues: the nucleus pulposus (NP), ligamentous annulus fibrous (AF) that surrounds the NP, and the hyaline cartilaginous endplates (CEP). Nucleus pulposus, composed of chondrocyte-like NP cells and its secreted gelatinous matrix, is critical for disc health and function. The NP matrix underwent dehydration accompanied by increasing fibrosis with age. The degeneration of matrix is almost impossible to repair, with the consequence of matrix stiffness and senescence of NP cells and intervertebral disc, suggesting the value of glycoproteins in extracellular matrix (ECM). Here, via database excavation and biological function screening, we investigated a C-type lectin protein, CLEC3A, which could support differentiation of chondrocytes as well as maintenance of NP cells and was essential to intervertebral disc homeostasis. Furthermore, mechanistic analysis revealed that CLEC3A could stimulate PI3K-AKT pathway to accelerate cell proliferation to further play part in NP cell regeneration.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-022-04477-x.

Keywords: CLEC3A, Extracellular matrix, PI3K-AKT, Intervertebral disc degeneration

Introduction

There is an increasing number of musculoskeletal disorders and degenerative disc diseases (DDD) caused by ageing, trauma, and congenital abnormalities, which are the leading causes of disability around the world [1, 2]. Intervertebral disc degeneration (IVDD) is recognized as a common contributor to ubiquitous low back pain, which has been linked to ageing, excessive manual labour and genetic factors. [3]. The intervertebral disc (IVD) lies between the adjacent vertebral bodies to provide load support, flexibility, energy storage, and dissipation in the spine. The IVD is composed of fibrocartilagenous annulus fibrosus (AF) and nucleus pulposus (NP), which maintains homeostasis by secreting extracellular matrix (ECM) containing type II collagen and proteoglycans [4]. Besides, there is a thin layer of cartilage surrounding IVD, which often appears as pathological ossification in advanced IVDD cases [5, 6]. ECM, the majority of which is occupied by proteoglycan aggregates constrained within collagen fibrils, takes a very large proportion in bone, cartilage and IVD [5, 7]. Therefore, exploring proteoglycan and collagen consisted in musculoskeletal ECM is the demand for efficacious therapies to regenerate these tissues.

The superfamily of proteins containing C-type lectin-like domains (CTLDs) is a large group of proteins with diverse functions [8–11]. And in general, the common function of C-type lectin domain-containing (CLEC) protein lies in recognition of oligosaccharides attached to proteins in the ECM [11]. This type of specific binding mediated by these C-type lectins participates in cell–cell adhesion, immune responses, and intracellular signal transduction [12–16]. CLEC proteins comprise a diverse family of soluble and transmembrane extracellular proteins that function as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) [8, 11, 17]. Yue et al. proved that Clec11a promoted osteogenesis [15]. CLEC3A was identified as cartilage-specific antimicrobial peptides in septic arthritis, and contributed to cell proliferation through HIF1α signaling pathway [18, 19].

In this study, we aimed to further explore effective CLEC candidates as efficacious therapies for motor system disease, especially in IVDD. Through progressive screen, we discovered that CLEC3A could facilitate chondrogenesis, by accelerating cell proliferation and enhancing cartilage-specific ECM architecture. Mechanistically, CLEC3A took effect on proliferation acceleration by activating PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, while the blockade of which brought down Col2a1 expression and chondrocyte-like function. Nevertheless, exogenous CLEC3A could also stimulate osteoblastogenesis of precursor cells including BM-MSC, C3H10 and primary human NP cells. Taken together, those provide a promising possibility of CLEC3A for clinical treatment of osteoblast-, chondrocyte-related diseases and IVDD, in the meantime reminding the potential side effect of specific diseases.

Results

CLEC3A enhances osteogenesis and chondrogenesis

To decipher the roles of CLEC proteins in motor system, we first examined expression profiles of all CLEC protein-encoding genes with public expression database, BioGPS (http://biogps.org/). Through combining analysis of the Primary Cell Atlas of human (MSCs, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and embryonic stem cells as control) and home mouse GeneAtlas MOE430 (osteoblasts, osteoclasts, C3H10, 3T3L1 and C2C12), we obtained prime candidates of bone and cartilage regeneration, which were: Clec2i, Clec3a, Clec3b, Clec4a2, Clec4d, and Clec11a (Table S1 and Figure S1). These mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were later reported to contribute to the formation of various musculoskeletal tissues such as bone, cartilage, fat, muscle, ligament and tendon, while adult bone marrow-derived MSCs have been recognized as progenitors of both osteoblasts and chondrocytes, and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) as progenitor of osteoclasts [20–22]. Considering those, we verified the expression pattern of those genes in relevant cells, respectively, differentiated from bone marrow cells. Consistently, Clec2i, Clec3b, and Clec11a were verified highly expressed in osteoblasts differentiated from mouse bone marrow-derived MSC (BM-MSC), while Clec2i, Clec3a and Clec11a in chondrocytes, and Clec2i, Clec4a2 and Clec4d in osteoclast (Figure S2).

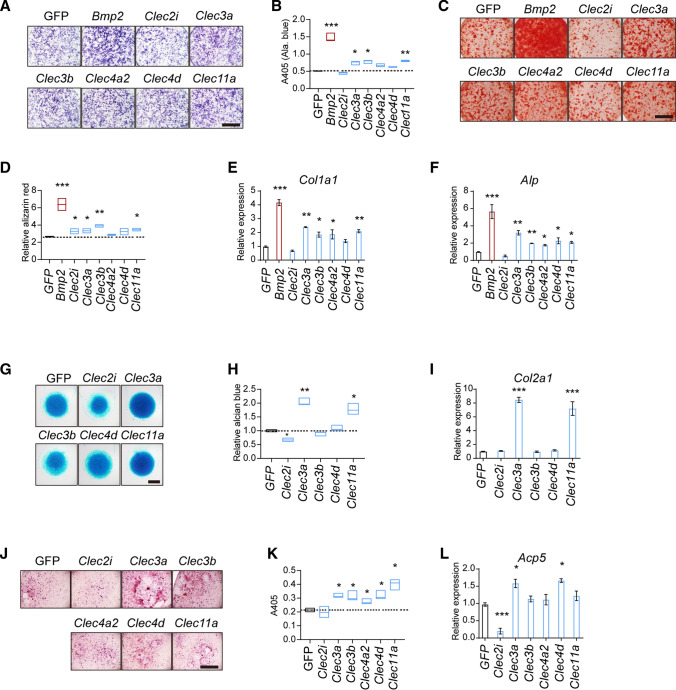

Next, we thought to examine the biological function of those listed genes. By establishing lentivirus producing system, Clec2i, Clec3a, Clec3b, Clec4a2, Clec4d, and Clec11a were over-expressed, respectively. Bone marrow-derived MSCs were isolated and infected with CLECs-expressing lentivirus, and BMP2- or GFP-expressing lentivirus as control. As shown in Fig. 1A–D, after 7- and 14-days of osteoblastic differentiation, exogenous Clec3a and Clec11a brought about a 20% increase in both alkaline phosphatase (Alp) and alizarin red staining compared with cells expressing GFP (Figs. 1A–D). We also introduced the chondrocyte micromass culture system. Clec3a and Clec11a induced remarkable promotion in matrix accumulation, which was monitored by alcian blue staining after 7 days’ culture (Fig. 1E–F). In contrast, Clec4d and Clec11a significantly increased the numbers of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)-positive osteoclasts (Fig. 1G–H). Consistently, the expression of osteoblastogenesis (Col1a1, Alp), chondrogenesis (Col2a1), and osteoclastogenesis (acid phosphatase 5, Acp5)-related genes changed accordingly (Fig. 1E, F, I and L). Taken together, Clec3a and Clec11a could influence the differentiation of both osteoblast and chondrocyte from MSC.

Fig. 1.

Functional screen of CLEC proteins in osteblastogenesis, chondrogenesis, and osteoclast differentiation. A and C Differentiation of osteoblast was evaluated by Alp staining and by Alizarin red S staining after differentiation respectively. B and D Quantitative parameters of Alp activity and Alizarin red S staining. G and H The representative photographs (E) and quantitative parameters (F) of micromass culture of chondrocytes derived from cartilage and stained using Alcian blue. J and K The representative photographs (G) and quantitative parameters (H) of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP)-staining of osteoclasts. Scale bar = 1 mm. E, F, I and L The expression of Col1a1 (E) and Alp (F) in differentiated osteoblasts; Col2a1 (I) in chondrocytes; and Acp5 (acid phosphatase 5) (L) in osteoclasts. Values represent mean ± S.D. (n = 3). p values were obtained from t tests with paired or unpaired samples: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars represent S.D

Clec3a is expressed highly in chondrocytes and chondrocyte-like cells, while weakly in osteoblast

CLEC3A is a 23-kDa protein closely related to tetranectin, which came from group IX of the C-type lectin family. As shown in a previous study, CLEC3A is considered a cartilage-specific protein that existed in articular cartilage as well as growth-plate cartilage. In addition, Masami Miki proved the abnormal expression of CLEC3A in patients bearing pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and identified the correlation between CLEC3A and the PI3K/AKT pathway [23]. D. Elezagic showed the treatment potential of CLEC3A-derived peptides as cartilage-specific antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) in septic arthritis [18], while Johannes Ruthard analyzed biomarkers potential of CLEC3A to support the clinical diagnosis of osteoarthritis [24]. In addition to function in the skeleton system, CLEC3A has been verified to bind plasminogen and contributes to its activation; and contributes to tumorigenesis and metastasis [23, 25]. The cartilage-specific CLEC3A enhances tissue plasminogen activator-mediated plasminogen activation [23, 25].

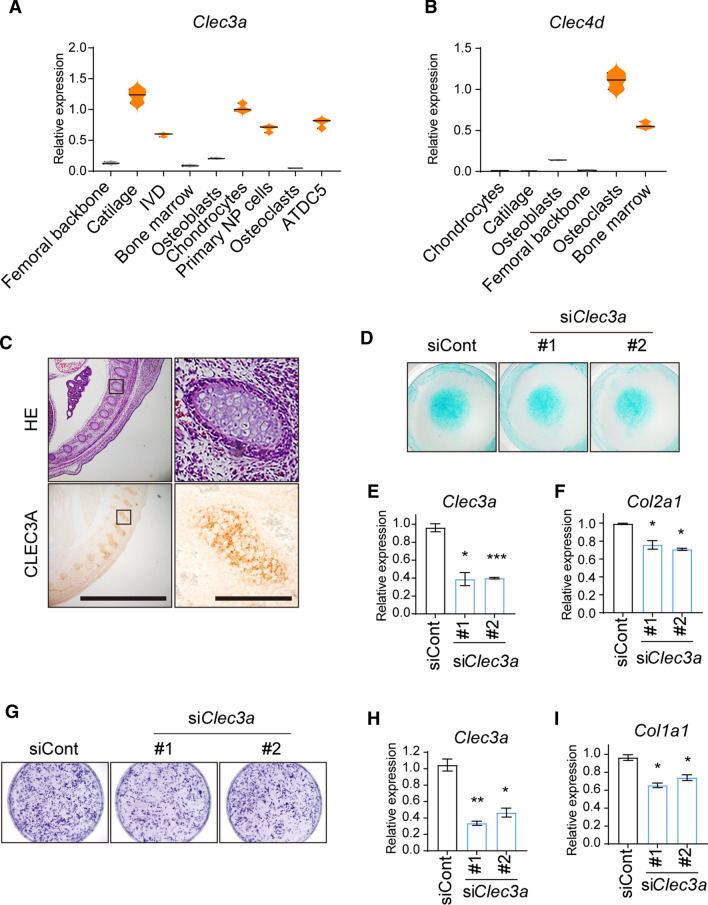

Next, we aimed to explore the expression pattern of Clec3a in chondrocytes and associated tissues and cells. We examined Clec3a expression in femoral backbone from 4-wk-old wild-type mice, articular cartilage of newborn wild-type mice, IVD from 12-wk-old wild-type mice, bone marrow from 6-wk-old wild-type mice, osteoblasts isolated from parietal bone of 1-wk-old wild-type mice, chondrocytes isolated from the articular cartilage of newborn wild-type mice, primary NP cells from IVD of 12-wk-old wild-type mice, osteoclasts differentiated from bone marrow of 6-wk-old wild-type mice, and ATDC5 cells (osteosarcoma cell line). Using quantitative RT-PCR, we observed the dramatic abundance of Clec3a in mouse cartilage, IVD, chondrocytes, and NP cells compared with osteoblasts and bone, as well as very rare in osteoclasts which present high Clec4d expression as control (Fig. 2A and B). Consistently, IHC analysis reconfirmed the existence of Clec3a in mouse vertebral cartilage at the age of E14.5 (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Clec3a is indispensable for differentiation of both chondrocyte and osteoblast. A and B The expression of Clec3a and Clec4d as control in identified tissues, primary cells, and cell lines. C Hematoxylin–eosin staining and immunohistochemistry analysis of CLEC3A distribution on vertebral cartilage at the age of E14.5 WT mouse. Scale bars = 200 and 20 μm. D The representative photographs of micromass culture of chondrocytes derived from cartilage and stained using Alcian blue. E and F The expression of Clec3a (E) and Col2a1 (F) in differentiated in chondrocytes. G Alp staining was used to monitored differentiation level of osteoblast. (H and I) The expression of Clec3a (H) and Col2a1 (I) in differentiated osteoblasts. p values were obtained from t tests with paired or unpaired samples: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars represent S.D

Clec3a deficiency could restrain differentiation of both chondrocyte and osteoblast

To further ascertain the biological function of CLEC3A in chondrocyte and osteoblast, we next examined the effects of siRNAs against Clec3a on chondrocyte differentiation and osteoblastogenesis. ATDC5 cells were transferred by two Clec3a-specific siRNAs and control siRNAs, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2D–F, the knock-down of Clec3a could suppress chondrocyte differentiation determined by alcian blue staining, and declined expression level of chondrocyte marker gene, Col2a1 in parallel with Clec3a. Consistently, Alp staining and Col1a1 expression demonstrated those siRNAs could also impair osteoblastogenesis of C3H10 (Fig. 2G–I). Taken together, those indicate that the existence of CLEC3A is requisite for the differentiation and function of both chondrocyte and osteoblast.

Despite there is no Clec3a expression in normal macrophages and/or osteoclasts, both of which are myeloid cell lineage. Considering the crosstalk between osteoblast and osteoclast has been well assumed, we next thought to detect whether Clec3a produced by osteoblasts and/or chondrocytes took part in the communication. The conditioned medium (CM) was collected from osteoblasts producing CLEC3A and GFP as control, and used to treat bone marrow-derived osteoclasts in the presence of macrophage colony stimulating factor. After 3, 5 and 7 days, multinucleated TRAP-positive osteoclasts exhibited that CM with Clec3a expressing promoted more matured osteoclasts formation (Figures S3A-B). Consistently, the expression of characteristic osteoclast marker genes, including Acp5, Ctsk (cathepsin K), Dc-stamp (dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein) and Oscar (osteoclast-associated receptor) were significantly enhanced by CM with Clec3a expressing (Figures S3C-F). Surprisingly, we discovered similar osteoclastogenesis promoting function in co-culture with chondrocytes (data not shown), suggesting the biological consistency of CLEC3A.

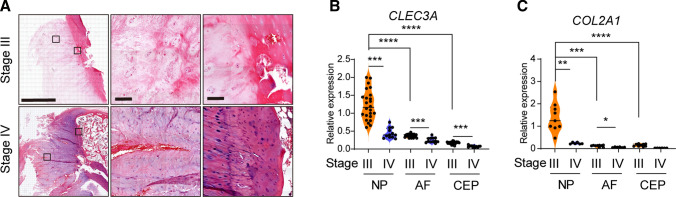

CLEC3A is downregulated in degenerated human IVD

Considering the abundant expression of Clec3a in mouse IVD and primary NP cells, we attempted to evaluate the correlation between CLEC3A level and the health and integrity of IVD. We performed histological analysis of IVD from patients suffering from degenerative disc disease at stage III and IV (Figure S4). As shown in Fig. 3A, angiogenesis was initially detected in annulus fibrosus at stage III, and got further deteriorated until stage IV (Fig. 3A, top). To make matters worse, blood vessel was found growing deeply into nucleus pulposus (Fig. 3A, bottom). Meanwhile, severe abnormal ossification appeared in surrounding cartilage (Fig. 3A, bottom). These findings suggested the progressive dysfunction and deterioration of intervertebral disc. We collected NP, AF and the edge cartilage from 12 patients bearing IVDD at stage III and IV (Table 1). By quantitative RT-PCR, we discovered the comparatively high expression level of both CLEC3A and COL2A1 in primary NP cells (Fig. 3B and C). In the meantime, expression level of both CLEC3A and COL2A1 decreased dramatically at stage IV compared to stage III (Fig. 3B and C). Collectively, these results indicate that CLEC3A loss was correlated with reshaping and degradation of IVD.

Fig. 3.

Phenotypic and expression analysis of intervertebral disc in IVDD patients. A Hematoxylin–eosin staining of tibia of intervertebral disc degeneration with intervertebral disc degeneration at stage III and stage IV determined by MRI grade, showing nucleus pulposus, surrounding fibrocartilagenous annulus fibrosus and cartilage surrounding IVD. Bars = 2 mm and 100 μm. B and C Analysis of Clec3a (B) and Col2a1 (C) transcriptional levels by quantitative RT-PCR using RNA isolated from primary NP, AF and CEP of cases in Table 1. p values were obtained from t tests with paired or unpaired samples: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars represent S.D

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the study population used for primary NP cells and sections

| No | Geneder | Age | MRI grade |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 75 | 3 |

| 2 | M | 43 | 3 |

| 3 | M | 74 | 3 |

| 4 | F | 48 | 3/4 |

| 5 | F | 52 | 3 |

| 6 | M | 59 | 3 |

| 7 | F | 66 | 4 |

| 8 | M | 54 | 4 |

| 9 | M | 71 | 4 |

| 10 | F | 52 | 3 |

| 11 | M | 52 | 3 |

| 12 | M | 45 | 3 |

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) grade was defined as Pfirrmann grading system

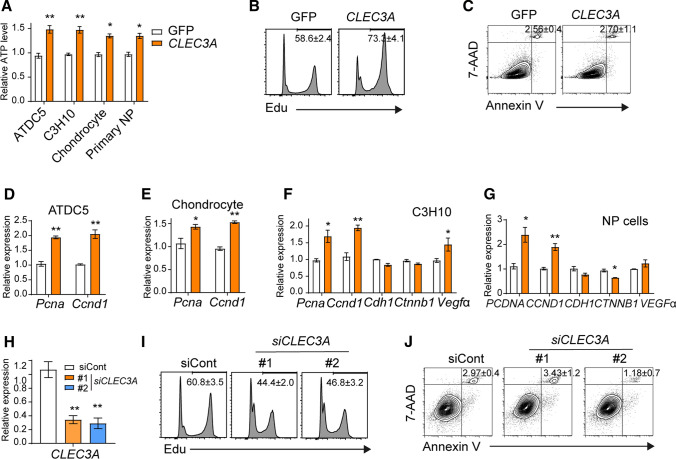

CLEC3A modulated cell proliferation and differentiation of NP cells via PI3K-AKT pathway

To explore how CLEC3A loss influences the morphology and function of the intervertebral disc, we first compared the cell proliferation with or without excess CLEC3A. Using Cell-titer Glo assay and EdU staining, we first found that additional CLEC3A expression would stimulate cell proliferation in ATDC5, C3H10, chondrocyte, and primary NP cells (Fig. 4A and B). In contrast, CLEC3A overexpression had no effect on the longevity of primary NP cells (Fig. 4C). Consistently, cell cycle facilitating genes, PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen) and CCND1 (cyclin D1) were stimulated by CLEC3A in chondrocyte, osteoblast, C3H10 and primary NP cells (Fig. 4D–G). We also noticed a slight variation tendency of expression level of cell adhesion and junction protein-encoding genes, Cdh1 (cadherin 1) and Ctnnb1 (catenin beta 1), and angiogenesis cytokine, Vegfα (vascular permeability factor, alpha), suggesting possible contributions of CLEC3A in cell interaction, migration, as well as angiogenesis (Fig. 4F–G). However, considering that severe degraded IVD (stage IV) possessed a lower CLEC3A level (Fig. 3B), blood vessels observed should not be due to induction of VEGFα secreted by primary NP cells (Figs. 3A, 4F, and G). Consist with those data, knock-down of CLEC3a in primary NP cells could also arrest cell proliferation, along with normal cell survival (Fig. 4H–J).

Fig. 4.

CLEC3A could accelerate cell proliferation. A The incorporation of cell proliferation of GFP- and CLEC3a-producing ATDC5, C3H10 and primary NP cells, respectively. Cell proliferation was analyzed by Cell tilter Glo after 48 h culture. B and I The incorporation of cell proliferation using Edu assay in primary NP cells. D–H Analysis of transcriptional levels of Clec3a, Pcna, Ccnd1, Cdh1, Ctnnb1, and Vegfα by quantitative RT-PCR, respectively. C and J Analysis of apoptosis in cells indicated. p values were obtained from t tests with paired or unpaired samples: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars represent S.D

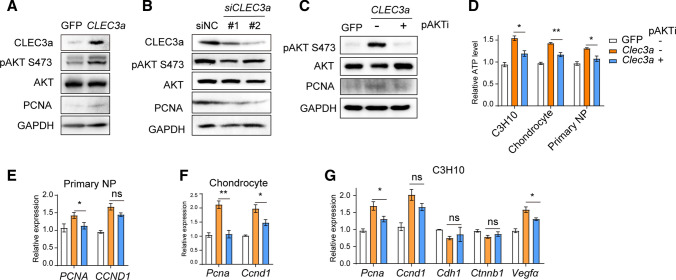

Pervious observation had demonstrated that PI3K-AKT signaling pathway could be activated by ECM, and in the following step promoted both cell proliferation, cell metabolism and intercellular communication [20, 26]. In addition, Chong et al. had discovered the suppression of CLEC3A declared protein level of AKT1, which then restrained cell proliferation and angiogenesis, and eventually inhibited tumorigenesis of osteosarcoma [19]. We also examined the total AKT1 protein level in primary NP cells by western blotting, which was almost equilibrium in both CLEC3A overexpression and know-down (Fig. 5A and B). Nevertheless, CLEC3A could stimulate the phosphorylation of AKT, which represented the activation status of PI3K-AKT signaling axis, which modulated cell proliferation, intracellular interaction and angiogenesis pathway by PI3K–AKT pathway (Fig. 5A and B).

Fig. 5.

CLEC3A stimulates activation PI3K–AKT pathway. A–C Western blot analysis of CLEC3a, total protein and phosphorylation of AKT and PCNA in primary NP cells with Clec3a overexpression (A), knock-down (B), and MK2206 treatment. D Cell proliferation of GFP- and CLEC3a-producing C3H10, primary chondrocytes and NP cells treated with or without MK2206, respectively. Cell proliferation was analyzed by Cell tilter Glo after 48 h culture. E–G Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of transcriptional levels of indicated genes in primary NP cells (E), chondrocytes (F) and C3H10 cells (G). p values were obtained from t tests with paired or unpaired samples: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. Error bars represent S.D

To demonstrate whether CLEC3A commanded NP cells through PI3K-Akt pathway, MK-2206, the most popular PI3K-Akt inhibitor was employed to restrain excessive activation of pAKT in CLEC3A-overexpressing primary NP cells (Fig. 5C), in C3H10 and primary chondrocytes (data not shown). Strikingly, inhibition of signaling using pAKTi (MK-2206) impaired the proliferation promotion effect of excess CLEC3A (Fig. 5D). Consistent with those, PCNA and CCND1 were suppressed by MK2206 in primary NP cells, chondrocytes and C3H10 (Fig. 5E–G). These findings collectively demonstrated that CLEC3A enhanced cell proliferation via PI3K-AKT pathway in NP cells.

Our findings not only elaborate on the function of CLEC3A in IVD homeostasis, but also provide the possibility of CLEC3A for clinical treatment of osteoblast-, and chondrocyte-related diseases.

Discussion

Increasing evidence has shown that ECM plays important role in aging-related intervertebral disc degeneration. Deciphering the mechanisms by which ECM modulates IVD is the key to understanding the pathogenesis of IVDD. Here, we provide evidence that CLEC3A and its stimulated PI3K-AKT signaling are required for the maintenance of nucleus pulposus and articular cartilage homeostasis.

Currently, the TGFβ signaling-based treatments for IVD degeneration have been in clinical practice, which includes direct repairment of IVD degeneration, and indirectly by combination with tissue engineering technology. Previously study had shown that the dynamic changing expression of TGFβs and TGFβ receptors during both embryonic development and degeneration of the IVD [27–30]. Peck SH et al. demonstrated the increase of TGFβ1 expression from embryonic to the perinatal period in mouse IVD [27]. However, the changes in the expression of TGFβ signaling in IVD remain exclusive. Nerlich AG et al. reported the correlation between increased TGFβ1 expression and IVD degeneration [28]. But Schroeder M et al. described the TGFβs expression declined in degenerated NP tissues, while increased in degenerated AF tissues [29]. Analogously, Abbott RD et al. observed the loss of TGFβRI in severely degenerated NP cells [30]. We also observed the decline of TGFβ1 RNA in severe IVDD patients mentioned in Fig. 5 (Figure S5A). Analogously, the inhibition of PI3K-Akt also attenuated the cell migration ability by trans-well assays (Fig. 5F-G). And even more interestingly, the expression of Tgfβ1, Tgfβ2 and Tgfβ3 could be strengthened by CLEC3A, while the inhibition of PI3K–Akt pathway by MK2206 could attenuate the increase (Figure S5B).

Both TGFβ and PI3K–AKT pathways could be regulated by ECM, suggesting the possible facilitation function of CLEC3A as an important component of ECM. Different from the direct PI3K–AKT activation function by TGFβ, AKT and/or PI3K–AKT could modulate TGFβ pathway in a multiple way. Huang et al. point out that activated AKT could phosphorylate Smad3, the key transcription factor in TGFβ transduction pathway, and switches its downstream regulation genes [31]. Nevertheless, excessed AKT appears to arrest the function of SMAD3 in TGFß-stimulated nuclear signaling by both the physical binding and sequestration of Smad3 in the cytoplasm, and PI3K–AKT–mTOR signaling axis [32, 33]. Considering those multiple relationships among TGFβ, AKT and ECM in IVD, traditional TGFβ treatment strategy and therapeutic potential of CLEC3A and PI3K-AKT activator treatment are confronted with many challenges needed to be solved.

The findings of this study have to be seen in light of some limitations. The biological functions of CLEC3A were explored only in vitro, and the primary NP cells derived from IVDD patients were introduced to describe the clinical relevance between CLEC3A and IVDD. The Clec3a-deficient genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) combined with the puncture IVD model should be obtained in further studies. In addition, omics analysis of degenerative IVD samples from IVDD patients and mouse models would contribute to further investigation of the molecular mechanism of CLEC3A in regulating the development of IVD and the pathological process of IVDD.

In conclusion, the present study suggested that CLEC3A could promote cell proliferation and improve cell differentiation. Mechanistically, CLEC3A may be involved in IVD-protecting process not only as an ECM protein, but also through regulating the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, which next influences TGFβ pathway. Thus, CLEC3A may contribute to the development of IVD, as well as a potential therapeutic target for IVDD treatment.

Star methods

Patient samples

All NP specimens were obtained from patients with degenerative disc disease (Table S). For RT-PCR, 12 patients (7 males and 5 females; mean age 57.6 ± 11.3 years were obtained; for histological analysis, 2 patients (2 females, age = 67 and 51); for primary NP cells, two patients were obtained (2 females, age = 67 and 51). The degree of IVDD was assessed according to modified Pfirrmann grading system by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [34]. Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, and informed consents were obtained from each donor.

Mouse

All mice analyzed were maintained on the C57BL/6 background, and maintained under pathogen-free conditions at the Experimental Animal Centre of Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Cell culture

ATDC5, C3H10T1/2, CP-H174 and BT474 cells were obtained from ATCC, and cultured as mentioned. Primary cultures of murine osteoblasts were isolated from calvariae of newborn mice. For quantitative analysis of Alp activity, osteoblasts were incubated with Alamar Blue and were then incubated with phosphatase substrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and measured with the luminometer (Envision). Primary BMSCs were isolated from the long bone of mice at 8-wk-old. Bone marrow was flushed with PBS and then pelleted at 400 ×g for 5 min. The pellet was suspended in RPMI medium with 10% FBS and cultured. For primary chondrocytes, articular cartilage from newborn wild-type mice was digested for 1 h in 100 mg of Dispase II (D4693, Sigma-Aldrich), and 50 mg collagenase (C0130, Sigma). Two-dimensional micromass culture was initiated by spotting 1 X 105 chondrocytes in 10 μl to a well of a 12-well plate and maintained in a chondrogenic differentiation medium (DMEM supplemented with 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium, 500 nM/ml TGFβ3 (243-B3-200, R&D Systems), 10 nM dexamethasone, and 0.1 mM L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate. After a 5-day differentiation, the micromass culture was stained with 1% Alcian blue. ATDC5, C3H10T1/2, primary murine chondrocytes and osteoblasts α-MEM (Corning, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) at 37 °C under 5% CO2 and 20% O2. The mouse intervertebral disc (IVD) was collected from the tails of 2-wk-old mice. The primary nucleus pulposus (NP) were digested by 1% type II collagenase for 30 min at 37 °C and cultured in DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in the incubator at 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Human NP cells were isolated from patients by collagenase I, II and IV, and were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/F12 containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% CO2.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from cells or tissues using TRIzol (T9424, Sigma) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using the High-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative RT-PCR reaction was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche) and the StepOnePlus system (Applied Biosystems). Relative expression of target genes was calculated according to the Ct value with normalization to Gapdh.

Protein preparation and Western Blotting

Cell extracts were prepared with EBC buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 120 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, and protease inhibitor mixture (S8820, Sigma-Aldrich)). Protein lysates (50 µg) were separated on 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gels, transferred onto PVDF membranes, and blocked with 5% blotting grade milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween (20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6), 137 mM NaCl, and 0.5% Tween 20), probed with the indicated primary antibodies, incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies, and detected using a chemiluminescence assay (EMD Millipore, Billerica). Membranes were exposed using BioRad ChemiDoc XRS.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h and incubated in 15% DEPC-EDTA (pH 7.8) for decalcification. Then, specimens were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 6 μm and stained with Hematoxylin–eosin (HE). Immunohistochemistry was performed using indicated antibodies according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were captured using a microscope (Olympus BX51, Tokyo, Japan).

Transfection of siRNA

The siRNA of target genes was ordered from GenePharma. Target sequence listed as follow: siClec3a-1: 5ʹ-CUGAUGACAACACUUUAAATT-3ʹ; siClec3a-2: 5ʹ-CUCUCAGGGUUUGGGAUAUTT-3); transfection of indicated siRNA was performed according to the protocol of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX. To perform acinar cell transfection, freshly isolated cells were allowed to recover in Waymouth medium for 4 h and then co-cultured with siRNA and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX for another 6 h.

Generation of plasmids, lentivirus, and protein-expressing cells

The indicated mouse genes encoding sequence was PCR amplified and introduced into pCDNA3.1 and/or pLVX plasmids. The lentivirus was produced by co-transfection of target plasmids with VSVG and Δ8.9 plasmids into HEK293T cells following the protocol from Open Biosystems (GE Healthcare). The lentivirus was infected into indicated cells, which would be selected upon puromycin (2 ng/ml).

Cell viability assay

Cells were plated into 96-well plates for 6 days. Cell viability was then measured by using Cell-titer Glo Assay (G7571, Promega).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation assays were performed with Click-iT™ Plus EdU Alexa Fluor™ 488 Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Life Technology, C10632). 5 × 105 cells were seeded onto filters and cultured for 16 h. Add EdU (10 μM in DMSO) to the culture medium for 1 h, harvest cells and proceed immediately according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell apoptosis assay

Cell apoptosis was measured with Annexin V-APC Apoptosis Detection Kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (KGA1026, KeyGEN Biotech). The stained cells were acquired for analysis on LSRFortessa (BD), and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc.).

Antibodies

Antibodies were used as follows: anti-AKT (2920S), pAKT S473 (4060S) were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc; anti-GAPDH (HRP-60004) was from Proteintech; anti-Clec3a (PA5-97,595) were from Thermo.

Data mining using public database

The gene expression data for data mining was downloaded from the public expression database BioGPS (http://biogps.org/). Human CLEC protein-encoding genes were exhibited in MSCs, osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and embryonic stem cells as control from the Primary Cell Atlas which were processed by the meta-analysis of a large number of publicly available microarray datasets (745 samples, from over 100 separate studies of human primary cells) (1). The mean expression level was calculated to represent each gene. Mouse CLEC protein-encoding genes were exhibited in osteoblasts, osteoclasts, C3H10, 3T3L1 and C2C12 from the GeneAtlas MOE430, which were processed from a diverse array of normal tissues, organs, and cell lines in mice.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed more than twice, and the data are presented as the mean ± SD. A student t test was used to compare the effects of all treatments. Statistically significant differences are indicated as follows: “*” for p < 0.05, “**” for p < 0.01 and “***” for p < 0.001.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

LL designed experiments, YJ interpreted data; XC and FF performed most of the experiments; ZL assisted in some experiments; YJ provided the key materials; LQ was assisted in some discussion; XC and YJ wrote the manuscript; LL and Hongxing Shen provided the overall guidance.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from National Natural Science Foundation (81972127, 81802216), Shanghai Science and Technology Fund (20DZ2201300), Incubating Program for Clinical Research and Innovation of Renji Hospital (PYZY16-010).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Xiuyuan Chen, Yucheng Ji, Fan Feng, Zude Liu, Lie Qian, Hongxing Shen and Lifeng Lao declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Renji Hospital, School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiuyuan Chen, Yucheng Ji and Fan Feng contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Huang YC, Urban JP, Luk KD. Intervertebral disc regeneration: do nutrients lead the way? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(9):561–566. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rezwan K, Chen QZ, Blaker JJ, et al. Biodegradable and bioactive porous polymer/inorganic composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2006;27(18):3413–3431. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urban JP, Roberts S. Degeneration of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5(3):120–130. doi: 10.1186/ar629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priyadarshani P, Li Y, Yao L. Advances in biological therapy for nucleus pulposus regeneration. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24(2):206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vergroesen PP, Kingma I, Emanuel KS, et al. Mechanics and biology in intervertebral disc degeneration: a vicious circle. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23(7):1057–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowdell J, Erwin M, Choma T, et al. Intervertebral disk degeneration and repair. Neurosurgery. 2017;80(3S):S46–S54. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyw078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song Y, Wang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Advanced glycation end products regulate anabolic and catabolic activities via NLRP3-inflammasome activation in human nucleus pulposus cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21(7):1373–1387. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drickamer K. C-type lectin-like domains. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9(5):585–590. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weis WI, Taylor ME, Drickamer K. The C-type lectin superfamily in the immune system. Immunol Rev. 1998;163:19–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1998.tb01185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wevers BA, Geijtenbeek TB, Gringhuis SI. C-type lectin receptors orchestrate antifungal immunity. Future Microbiol. 2013;8(7):839–854. doi: 10.2217/fmb.13.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zelensky AN, Gready JE. The C-type lectin-like domain superfamily. FEBS J. 2005;272(24):6179–6217. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nasu J, Uto T, Fukaya T, et al. Pivotal role of the carbohydrate recognition domain in self-interaction of CLEC4A to elicit the ITIM-mediated inhibitory function in murine conventional dendritic cells in vitro. Int Immunol. 2020;32(10):673–682. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxaa034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weng TY, Li CJ, Li CY, et al. Skin delivery of Clec4a small hairpin rna elicited an effective antitumor response by enhancing CD8(+) immunity in vivo. Mol Therapy Nucl Acids. 2017;15(9):419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen ST, Lin YL, Huang MT, et al. CLEC5A is critical for dengue-virus-induced lethal disease. Nature. 2008;453(7195):672–676. doi: 10.1038/nature07013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yue R, Shen B, Morrison SJ. Clec11a/osteolectin is an osteogenic growth factor that promotes the maintenance of the adult skeleton. Elife. 2016 doi: 10.7554/eLife.18782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M, Guo J, Zhang L, et al. Molecular structure, expression, and functional role of Clec11a in skeletal biology and cancers. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(10):6357–6365. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukuhara H, Furukawa A, Maenaka K. New binding face of C-type lectin-like domains. Structure. 2014;22(12):1694–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elezagic D, Morgelin M, Hermes G, et al. Antimicrobial peptides derived from the cartilage-specific C-type Lectin Domain Family 3 Member A (CLEC3A) potential in the prevention and treatment of septic arthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27(10):1564–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren C, Pan R, Hou L, et al. Suppression of CLEC3A inhibits osteosarcoma cell proliferation and promotes their chemosensitivity through the AKT1/mTOR/HIF1alpha signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2020;21(4):1739–1748. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.10986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C, Smith MP, Zhou GK, et al. Phlpp1 is associated with human intervertebral disc degeneration and its deficiency promotes healing after needle puncture injury in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(10):754. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1985-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kfoury Y, Scadden DT. Mesenchymal cell contributions to the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16(3):239–253. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinho S, Frenette PS. Haematopoietic stem cell activity and interactions with the niche. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(5):303–320. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0103-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miki M, Oono T, Fujimori N, et al. CLEC3A, MMP7, and LCN2 as novel markers for predicting recurrence in resected G1 and G2 pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Med. 2019;8(8):3748–3760. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruthard J, Hermes G, Hartmann U, et al. Identification of antibodies against extracellular matrix proteins in human osteoarthritis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;503(3):1273–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lau D, Elezagic D, Hermes G, et al. The cartilage-specific lectin C-type lectin domain family 3 member A (CLEC3A) enhances tissue plasminogen activator-mediated plasminogen activation. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(1):203–214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.818930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoxhaj G, Manning BD. The PI3K-AKT network at the interface of oncogenic signalling and cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(2):74–88. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0216-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peck SH, McKee KK, Tobias JW, et al. Whole transcriptome analysis of notochord-derived cells during embryonic formation of the nucleus pulposus. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):10504. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10692-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nerlich AG, Bachmeier BE, Boos N. Expression of fibronectin and TGF-beta1 mRNA and protein suggest altered regulation of extracellular matrix in degenerated disc tissue. Eur Spine J. 2005;14(1):17–26. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0745-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroeder M, Viezens L, Schaefer C, et al. Chemokine profile of disc degeneration with acute or chronic pain. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;18(5):496–503. doi: 10.3171/2013.1.SPINE12483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abbott RD, Purmessur D, Monsey RD, et al. Degenerative grade affects the responses of human nucleus pulposus cells to link-N, CTGF, and TGFβ3. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2013;26(3):E86–94. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e31826e0ca4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang F, Shi Q, Li Y, et al. HER2/EGFR-AKT signaling Switches TGFβ from inhibiting cell proliferation to promoting cell migration in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2018;78(21):6073–6085. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conery AR, Cao Y, Thompson EA, et al. Akt interacts directly with Smad3 to regulate the sensitivity to TGF-beta induced apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(4):366–372. doi: 10.1038/ncb1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song K, Wang H, Krebs TL, et al. Novel roles of Akt and mTOR in suppressing TGF-beta/ALK5-mediated Smad3 activation. Embo j. 2006;25(1):58–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, et al. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26(17):1873–1878. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200109010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.