Abstract

Chronic stress activates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis to aggravates tumorigenesis and development. Although the importance of SNS and HPA in maintaining homeostasis has already attracted much attention, there is still a lot remained unknown about the molecular mechanisms by which chronic stress influence the occurrence and development of tumor. While some researches have already concluded the mechanisms underlying the effect of chronic stress on tumor, complicated processes of tumor progression resulted in effects of chronic stress on various stages of tumor remains elusive. In this reviews we concluded recent research progresses of chronic stress and its effects on premalignancy, tumorigenesis and tumor development, we comprehensively summarized the molecular mechanisms in between. And we highlight the available treatments and potential therapies for stressed patients with tumor.

Keywords: Epinephrine, Norepinephrine, Glucocorticoids, Tumor formation, Tumor progression, Tumor inhibition

Introduction

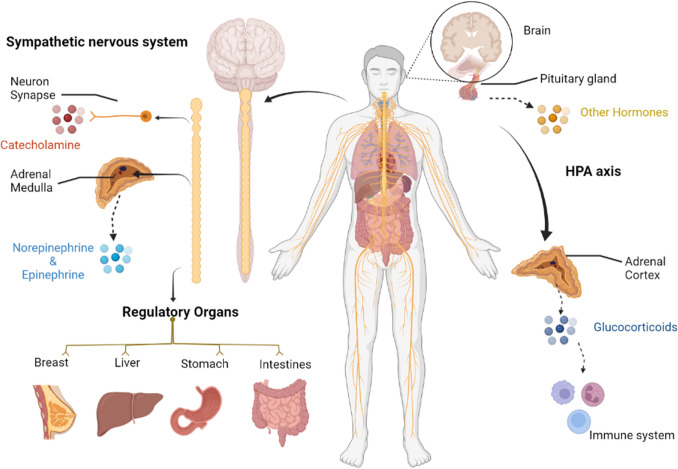

Stress, a response to outer stimulation accompanied with neuroendocrine changes. It is mainly mediated by two pathways: sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. After activation, SNS releases catecholamine, including epinephrine and norepinephrine, via the sympathetic nerve fiber and adrenal medulla, while HPA axis increases the release of glucocorticoids (GCs) from the adrenal cortex.

SNS regulates functions of organisms mostly. Sympathetic nerves are distributed in organs, blood vessels and glands. By secreting catecholamine, they regulate muscle constriction, gastrointestinal peristalsis and glands secretion. Liver, stomach, breasts and prostate are mostly innervated by sympathetic nerves. Specifically, originated from the spinal cord (T7–T12) to the coeliac ganglion, sympathetic nerve fibers distribute along the plexus into the liver. After entering the liver, the sympathetic nerves reaches the interlobular space, parenchyma, liver cells, peripheral sinusoidal cells, hilar vessels and peripheral central veins [1]. The sympathetic nerves enter stomach from 6 to 10 segments of the spinal cord, where pre-ganglionic fibers form the visceral large nerves performing neuron exchange in the coeliac ganglion [2]. Additional innervation is found in the papilla, areola and breast tissue along the vessels. It has also been seen that β-adrenergic receptors (β-ARs) (the main effector of SNS) are enriched in prostatic luminal cells and prostatic stromal cells [3]. Consistently, HPA axis is an important part of the neuroendocrine system, involved in controlling responses to stress and regulating many physical activities, such as digestion, the immune system regulation, mood regulation and energy storage and expenditure. Induced by HPA axis, GCs participate in metabolic regulation and immune regulation. Anatomically, both the SNS and HPA-axis are involved in many physiological processes, and their disorders lead the occurrence of various diseases (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

SNS and HPA axis regulates organs and tissues under stress. Under stressor, catecholamine and glucocorticoid releasing from SNS synapse, adrenal medulla and adrenal cortex play a dominant role in the regulation of stress response. SNS can manipulate almost all physiological functions of various organs including breast, liver, stomach and intestines. While HPA axis regulate metabolic and inflammatory effects through glucocorticoid

In emergency, stress hormones participate in a series of physiologic processes to regulate the physiologic status for the purpose of self-protection (fight or flight response). However, researches over the past decades has proven that chronic stress affect health in a consistent period [4]. Chronic stress induces social isolated rhesus monkeys with a high likelihood of virus infection [5]. It has also revealed that the immune system of chronic stressed animals is affected by decreasing the number of splenic cells via the FAS-mediated apoptosis [6]. Results from 5744 US adults with social stress identified that chronic stress accelerate immune aging by decreasing naïve and increasing terminally differentiated T cells [7]. Moreover, clinical studies show that chronic stress lead to cognitive decline via HPA axis. Another animal experiment supports that chronic restraint stress suppresses the hippocampal neurogenesis in adult mice by inducing the autophagic cell death of hippocampal neural stem cells [8]. Given that GCs released from adrenal cortex have the prominent role in pressure adaption and emotional modulation, it seems reasonable to attribute the dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex to GCs’ dysregulation, which is induced by chronic stress and lead to depression in the end [9]. In addition, it is noting that chronic stress innervates the distribution of SNS to aggravate the stress response [10]. Researches prove that chronic social stress could highly increase the density of sympathetic nerve fibers in rhesus monkey lymph nodes, which worsen their stressed state in return [11]. Chronic stress, therefore, is a risk factor of health.

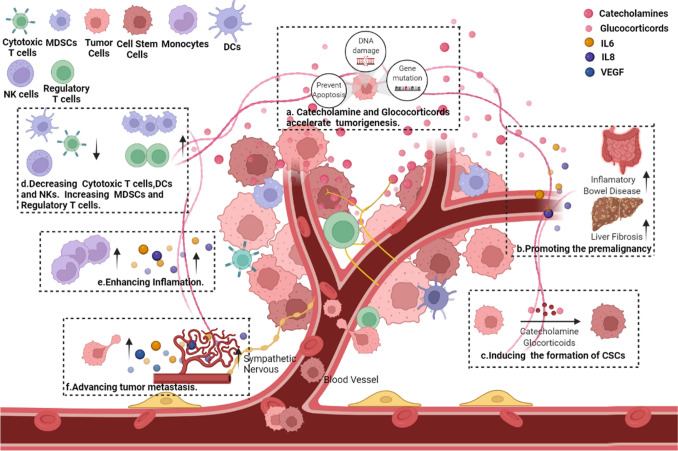

Studies reveal that chronic stress are involved in the regulation of 8 of the 14 tumor hallmarks defined in 2022 [12], including sustaining proliferative signaling, unlocking phenotypic plasticity, resisting cell death, increasing genome instability and mutation, activating tumor-promoting inflammation, avoiding immune destruction, activating invasion and metastasis and accessing vasculature [13, 14]. Animal models of chronic stress also prove that chronic stress is conducive to promoting tumorigenesis [15, 16], advance the metastases of breast cancer and gastric cancer [17, 18], and induce the formation of cancer stem cells [19, 20]. In multiple clinical trials, chronic stress is also proven to have a direct relationship with tumorigenesis and development. Induction of chronic stress could lead to elevated levels of serum/urinary catecholamine in patients with breast cancer [21, 22], and increased expression of AR in patients having hematologic tumor [23], cervical cancer [24], hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [25], colorectal cancer [26], gastric cancer [27] and breast cancer [28, 29]. Our review summaries the research progress on chronic stress for its role in advancing tumorigenesis and development through the hypersecretion of stress hormone. In the meantime, this study also describes the current treatment and potential strategies from the side of chronic stress to inhibit tumor progress.

Chronic stress and tumorigenesis

Genomic instability

Genetic mutation is an important driver of tumorigenesis, and the genomic stability is certainly affected by the signal molecules related to chronic stress. Multiple studies have suggested that high levels of catecholamine and GCs indicate a higher risk of mutations in genes. In vivo study revealed that chronic stress led a faster tumor development in mice of skin cancer model induced by UV lamp [16]. In clinical studies, patients experiencing chronic stress have significantly accelerated telomere shortening in peripheral monocytes and impaired integrity of the genome [21]. Given the studies, chronic stress advances tumorigenesis via inducing genomic instability.

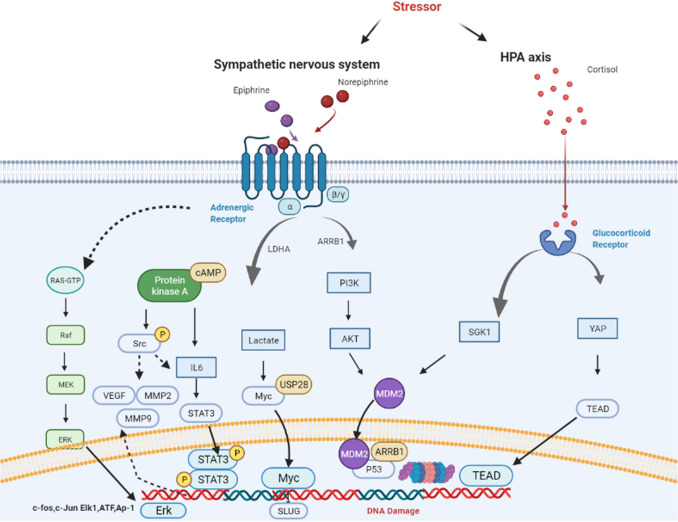

Activation of oncogenes

It is reported that the activation of β2-AR increase the expression of Src via the downstream β2-AR/PKA pathway [30]. In gastric cancer, activated β2-AR enhance the expression of ERK1/2 and then activate the JNK–MAPK signaling pathway to accelerate the development of the tumor [27]. In colorectal cancer, β2-AR also activates the downstream ERK1/2 to advance tumorigenesis and development [31]. In breast cancer, there is a forward feedback loop between β2-AR and HER2. Isoproterenol could increase the binding between STAT3 and HER2 promotor and concurrently enhance the phosphorylation of ERK via triggering the activation and nuclear translocation of STAT3. In that way, autocrine released epinephrine from breast cancer cells lead to up-regulation of β2-AR in return [14]. In addition, Myc in breast cancer is also reported under control of epinephrine and work as a participant in the formation of cancer stem cells [19]. Collectively, chronic stress could induce tumorigenesis via highly increasing the activation of oncogenes (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Regulating mechanisms of chronic stress. Upon stimulation of stressor, catecholamine and glucocorticoid releasing from SNS synapse, adrenal medulla and adrenal cortex play a dominant role in the regulation of stress response. SNS can manipulate almost all physiological functions of various organs including breast, liver, stomach and intestines. While HPA axis regulate metabolic and inflammatory effects

DNA damage

p53 is a recognized tumor suppressor gene and its deactivation is important in tumor formation due to its role of DNA repairing [32]. Numerous studies have found that chronic stress inhibits p53 function and thereby advances tumorigenesis. For example, the activation of β2-AR in breast cancer cells suppresses p53 via the β-arrestin-1/PI3K/AKT cascade, accompanying impaired genomic integrity [33]. GCs could concurrently increase the Murine Double Minute 2 (MDM2) expression and induce the expression of Serine/threonine–protein kinase 1 (SGK1) [34] to decrease the p53 function. In triple-negative breast cancer, the up-regulation of Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 1A/protein 21 (CDK1A/p21) induces the phosphorylation of ATR at Ser428 resulting in DNA damage after stimulation with GCs and norepinephrine [35]. Epinephrine also elicits DNA-strand break via impairing Poly ADP-Ribose Polymerase 1 (PARP1) activity [36]. It infers that the chronic stress could induce DNA damage to advance tumor formation.

Premalignancy

It has been identified that chronic stress affects tumor formation in a progressive manner. Current researches suggest that the chronic stress is important in premalignancy, which is the most significant in inflammatory bowel diseases. An animal study proved that chronic stress induces inflammatory bowel disease in mice [37]. Chronic stress increases the intestinal permeability by elevating corticotropin releasing factors (CRF), leading to alterations of the microbial composition and increased secretion of inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 [38, 39]. In addition, the regulatory T cells (Treg) differentiate into Foxp3+ /IL17+ /TNF-α+ T cells after stress, and stress-derived prolactin stimulates dendritic cells (DCs) in intestine to release IL-6 and IL-23 to alter Treg’s phenotype [40]. Clinical trials also identified that chronic psychological stress could increase the susceptibility of patients to inflammatory bowel disease [41, 42], and long-term inflammatory bowel disease may increase the incidence of colorectal cancer [43]. β-AR inhibition and psychological intervention have been reported as efficient approaches to improve the symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease [44]. Chronic stress also induces the formation of gastritis in mice via decreasing the production of Hydrogen sulfide (HS) and impairing the balance of the bacterial flora in the stomach [45].

Moreover, chronic stress results in incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) by increasing the release of GCs and subsequent intrahepatocellular lipid accumulation [46]. The up-regulation of GCs also lowers the expression of TGF-β in mesenchymal stem cells in turn to decrease the liver injury repair [47]. Consistently, the catecholamine secreted by sympathetic nerves causes liver injury. Recent researches reveal that the nervous system participates in the pathology of the liver. Upon chronic hepatitis or liver cirrhosis, the distribution of sympathetic nerve fibers changes with the structure of lobules, and the sympathetic nerves activated by the centrally administered corticotropin-releasing factors aggravates the CCL4-induced acute liver injury [48]. In SNS, the norepinephrine secreted by sympathetic nerves advances the incidence of fibrosis [49], and blockade of the secretion can significantly decrease the fibrosis [50]. Upon stimulation, Kupffer cells release inflammatory factors(IL6 and TNF alpha) to form an inflammatory microenvironment, while the HSCs speed up liver cirrhosis [51, 52], which collectively advance the formation of HCC. Hence, chronic stress advances the premalignancy to promote the tumor formation.

Cancer stem cells

Cancer stem cells, a small class of cells with stemness feature in tumor, advance the migration, invasion and drug resistance of tumor cells to potentiate tumor formation. In vitro studies prove that epinephrine could augment the expression of stemness markers, including sonic hedgehog (SHH), aldehyde dehydrogenase-1 (ALDH-1) and GLI family zinc finger 1 (Gli1), in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells, and enhance the cell sphere-forming capacity. In addition, in vivo study reveals that the growth of the xenograft tumor could be slowed after attenuating the stress, which is in association with the decreased activation of cAMP [53]. It is also identified that long-term activation of nicotine receptor significantly increases the release of stress hormone and the expression of tumor stemness marker SHH, accompanying increased expression of Gli1 proteins and decreased secretion of inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). While supplementation of GABA reverses above processes [54]. The release of epinephrine in breast cancer after chronic stress promotes the deubiquitination of MYC via the lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA)-dependent metabolic reprogramming, activates the SLUG promoter and thereby augment the stem cell-like features [19]. In HCC, the up-regulation of norepinephrine increases the expression of secreted frizzled related protein 1 (sFRP1) in HSCs, which in turn enhances the binding between Wnt16b and receptor FZD7 and subsequently actives the β-catenin to improve the stemness [55]. In addition, norepinephrine enhances the stemness phenotypes in oral squamous carcinoma (OSCC) and up-regulates expression of stemness markers by inducing the phosphorylation of ERK and cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB) [56]. The role of GCs in regulating tumor stem cells is majorly reported in breast cancer, which is achieved via regulating the expression of Yes associated protein (YAP) involved in the Hippo signaling pathway [57]. GCs inhibitors could reversely increase the ubiquitination and degradation of GCs receptors, leading to suppressed YAP1 expression and subsequent formation of cancer stem cells [58]. Up-regulation of GCs promotes the progression of breast cancer by activating the Hippo signaling pathway via the TEA domain transcription factor 4 (TEAD4) [59]. All these findings demonstrate that chronic stress could improve the formation of tumor stem cells to advance tumorigenesis.

Chronic stress promotes tumor development

Autophagy and apoptosis of tumor cells

Stress hormones are protective for tumor cells via inhibiting cell autophagy and apoptosis. For instance, stress hormones inhibit cell autophagy in gastric cancer cells via suppressing β2-AR-Adenosine 5´-monophosphate (AMP)–AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) axis [18]. While in breast cancer cells stress hormones reduce autophagy by regulating phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) [60]. In ovarian cancer, the activation of Ars by catecholamine activates FAK to inhibit the anoikis of cells [61]. In a mouse model of prostate cancer, chronic stress could suppress cell apoptosis by activating the anti-apoptotic pathway ADRB2/PKA/BAD [62]. The activation of ARs in pancreatic cancer cells activates the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK and BCL-2) via the RAS/AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway to modulate cancer cell cycle process and suppress cell apoptosis [63]. Taken together, chronic stress advance tumor development by decreasing the autophagy and apoptosis of tumor cells.

Inflammation

The hypersecretion of epinephrine advances the proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells and promote the production of monocytes [64, 65]. The distribution of hematopoietic stem cells is also under the regulation of SNS. Studies prove that norepinephrine secreted by sympathetic nerves regulates the nuclear expression of transcription factor SP-1 in stromal cells to increase the expression of chemokine CXCL12. In addition, the expression of CXCR4 in white blood cells could also be enhanced, and the up-regulation of CXCL12 affects the distribution of white blood cells via promoting the release of hematopoietic stem cells from the marrow into the peripheral circulation [66–68]. Upon recurrent social defeated model, the activation of HPA axis and the increased release of corticosteroids in mice also affected release and distribution of bone marrow monocytes by regulating the expression of CXCL12 [69]. Moreover, there is expansion of pro-inflammatory monocytes in circulation and significantly increased numbers of peripheral Ly-6c (high) monocytes and Ly-6c (intermediate) neutrophils, which could be rescued after blocking β-AR [70]. Patients with breast cancer also have significant elevation of pro-inflammatory genes at the transcriptional level in white blood cells after stress [71]. Therefore, chronic stress accelerates tumor development by enhancing the inflammatory reactions.

Immune microenvironment

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), tumor infiltrates the lymphocytes (TILs), DCs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) communicate with tumor cells by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines in a paracrine manner [72]. Chronic stress activates the cAMP/PKA pathway and increases the secretion of IL-6 in tumor cells [73]. In ovarian cancer, the up-regulation of norepinephrine increases the secretion of IL-6 by activating the Src tyrosine kinase [74] and upregulates the release of IL-8 via increasing the expression of FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (FosB) [75]. In that way, the accumulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 advances tumor growth and recruits tumor-promoting immune cells. β-AR activation after stress increases the infiltration of TAMs via the cAMP/PKA/MCP signaling axis [17, 76]. In a social defected mouse model, β-AR inhibitor propranolol relives the spleen enlargement and the increases levels of serum IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1 [77]. Collectively, chronic stress generates an immunosuppressive microenvironment for tumor cells.

Chronic stress can decrease the clearance of tumor cells by the autoimmune system. Researches confirm that the β-AR activation after chronic stress affects the functions of Dendritic Cells (DCs) and Natural Killer cells (NK cells), decreases the number of Th17 cells via reducing the ratio of Th1/Th2, suppresses the differentiation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and elevates the count of MDSCs, which inhibits the killing effect of the autoimmune system for tumors [78]. Stress significantly lowers the activity of antigen presenting cells. For instance, chronic stress results in poorer therapeutic effect of tumor vaccine (poly (lactic-co-glycolide acid) microsphere (PLGA–MS) vaccine), through suppressing DC antigen recognition capability [79]. In a rat model of chronic stress, the up-regulation of epinephrine and prostaglandin suppresses the activity of NK cells, which indirectly advances the malignant progression of leukemia [80]. The increased GCs also decline the cytotoxicity of NK cells in turn to affect the immune function [81]. In mouse models of liver cancer, it is also proved that the increased level of GCs affected the function of NK cells by up-regulating the expression of PD-1 [82]. It is reported that the alterations of the level of GCs and the sensitivity of receptors leads to immunosenescence. The decline of native T cells demonstrates poorer immune response against new antigens, resulting in thymic involution, decline of cellular immunity and immune cell aging, which in turn causes reduced immune surveillance and finally promotes tumor immune escape [83]. Another animal study reveals that chronic stress activated the TLR2–p38 MAPK signaling pathway in native CD4+ T cells, which stimulates the release of IFN-γ and TNF-α by Th1-type cytokines and IL-17 by Th17-type cytokines, leading to a higher ratio of Th1/Th2, a larger number of Th17 cells and finally incidence of immunosuppression [84]. In squamous cell carcinoma induced by UV irradiation, chronic stress leads to a smaller number of Th cells by inhibiting Th1-type cytokines, which increases the count of Treg and subsequently advances tumor formation [15]. Epinephrine selectively suppresses the function of CD8+ T cells by stimulating the activation of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) and the releasing of Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase(IDO) and IL-10 [85]. In patients with ovarian cancer, depression results in reduced levels of IL-4, TNF-α and a lower ratio of CD4+/CD8+ [86]. The β2-AR signal activates the phosphorylation of STAT3 to suppress intercellular Fas–FasL interactions, which is highly beneficial for survival of tumor and MDSCs. In the meantime, activation of the β2-AR up-regulates the expression of immunosuppressor PD-L1 and arginase-I to suppress T cell proliferation, while the blockade of β2-AR activation results in immunosuppression impediment and improved efficacy of immunotherapy [87]. Clinical trials demonstrate that stressed patients with breast cancer have significantly high level of MDSCs and suppressed immune function [88]. The above studies indicate that chronic stress could advance tumor malignant progression via inhibiting the autoimmune system.

Tumor metastasis

Clinical studies reveal that there is a close relationship between chronic stress and tumor metastasis. The release of catecholamine after stress can increase the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) process, and the activation of fibroblasts can regulate wound healing and angiogenesis [89]. In mouse models of ovarian cancer [90], oral cancer [91] and prostate cancer [92], chronic stress increases the metastasis of the tumors. In patients with gastric cancer [93], breast cancer [94, 95] and melanoma [96], the activation of β-AR is also reported to advance the tumor metastatic capability. In addition, the β-AR antagonists(propranolol and ICI 118,551) are proven significantly suppressive for tumor metastasis of gastric cancer [97] and ovarian cancer [98]. Similar effect could also be found in patients with colorectal cancer [99, 100]. There are multiple factors involved in the action of chronic stress for tumor metastasis, such as tumor cell metastasis, tumor microenvironment, angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis [93].

Tumor cell metastasis

It is reported that chronic stress remarkably enhances the migration of tumor cells, where catecholamine, especially norepinephrine, elicits a strong stimulatory effect, while γ-GABA poses the opposite effect to inhibit tumor metastasis [101]. In ovarian cancer, the hypersecretion of norepinephrine and epinephrine up-regulate the expression of MMP2/9 via activating the IL6–STAT3 pathway, thereby advancing tumor cell migration and invasion [98]. In breast cancer, the chronic stress-induced activation of miR-337-3p/STAT3 axis increases metastasis of the tumor cells [102]. The high level of catecholamine in gastric cancer up-regulates the expression of transcription factor STAT3 and concurrently affects its interaction with c-JUN at AP1 site to increase MMP-7 expression [103]. The activation of β-AR in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) could augment the intracellular expression of MMP2, MMP-9 and VEGF, which could be effectively blocked via β-AR or MMP inhibitors [104]. Binding between transcription factor Y-Box1 (YB-1) and β2-AR leads to phosphorylation of the YB-1 by PI3K/AKT-β-catenin1 pathway, increasing nuclear YB-1 expression and thereby augmenting the expression of downstream EMT markers, such as E-cadherin, N-cadherin and Vimentin [105]. In breast cancer, the nuclear localization of HER2 was identified to be significantly associated with the overexpression of β2-AR. Catecholamine activates the expression and proteolytic activity of ADAM10, leading to shedding of HER2 extracellular domain and subsequent intramembranous cleavage of HER2 intracellular domain by presenilin-dependent γ-secretase Nuclear translocation of HER2 intracellular domain enhances transcription of tumor metastasis-associated gene COX-2 [106]. It has also been revealed that salbutamol (β2-AR specific agonist) activates ERK to induce EMT process [107]. The hypersecretion of norepinephrine after chronic stress could stimulates TGF-β1 secretion in breast cancer and enhances cancer cell ability of migration and invasion [108]. β1-AR blocker Atenolol significantly prevents the migratory capability of cells in breast cancer and prostatic cancer [109]. Our previous study reveals that chronic stress promotes prostate cancer metastasis via a sympathetic–cAMP–FAK signaling pathway. Chronic stress, therefore, could directly promote the metastasis of tumor cells [110].

Tumor microenvironment

The mesenchymal cells in tumor microenvironment, bone marrow mesenchymal cells and stromal cells are involved in tumor metastasis. The hypersecretion of norepinephrine and epinephrine induces DNA damage in mouse fibroblasts, resulting in increased cellular transformation and tumor progression [111]. The epinephrine-induced up-regulation of 6-O-sulfotransferase-1 (6-OST-1) under the control of the Src-ERK1/2 signaling pathway increases the synthesis of the sulfated structures of heparan sulfate in mouse fibroblasts, contributing to higher activity of tumor metastasis [112]. Sympathetic nerves regulate the macrophage infiltration in the tumor microenvironment via changing the expressions of the chemokine CCL2 and receptor CCR2, which is also important for tumor metastasis [17]. β2-AR agonist isoproterenol promotes the infiltration of macrophages to the lung during premetastatic phase [113]. While α1-AR antagonist Naftopidil significantly suppresses the proliferation of stromal cells, resulted to decreased IL-6 level [114]. The above studies reveal that chronic stress advances tumor metastasis via cooperating with some important cells in the tumor microenvironment.

Angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis

Angiogenesis is important in tumor metastasis by generating new blood vessels to facilitate tumor metastasis and provide necessary nutrients for tumor growth. Chronic stress induced activation of β-ARs promotes tumor angiogenesis [115]. Activation of the β2-AR–cAMP–PKA signaling pathway elevates the secretion of proangiogenic factors (IL-6, IL-8 and VEGF) to improve angiogenesis and subsequent tumor metastasis [116, 117]. Induced by stress hormone, β2-AR activation increases VEGF secretion and elevates the expression of the Plexin-A1/VEGFR2 signaling pathway, beneficial for the angiogenesis in gastric cancer cells [118]. In xenograft tumor of prostate cancer, activated β-AR signal induced by stress promotes angiogenesis through the histone deacetylase2 (HDAC2)-mediated suppression of Thrombospondin Protein 1 (TSP1) [119]. The degree of depression in patients with ovarian cancer is positively associated with the levels of VEGF in tumor and IL-6, MMPs in plasma and ascites [120–122]. The hypersecretion of VEGF in breast cancer also advances angiogenesis and bone metastasis, which could be significantly reversed with β-AR inhibitors [123]. Moreover, dopamine works against norepinephrine, which could effectively block tumor angiogenesis via activating its specific receptor Dopamine Receptor 2 (DR2) to reduce cAMP level and inhibit VPF/VEGF induced Src kinase activation [124].

The lymphatic vessel remodeling induced by communication between stress-induced neural signaling and inflammation promotes the lymphatic metastasis of tumor cells [125]. In mouse models of breast cancer, the activation of AR increased VEGF expression in tumor and stromal cells, beneficial for the activation of COX2 from TAMs and the remodeling of lymphatic architecture in the tumor microenvironment, which thereby promoted tumor cell metastasis [126]. Social isolation is identified to be associated with increased density of lymphatic vessels in patients with breast cancer [127]. Therefore, chronic stress accelerates tumor metastasis by increasing angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effects of chronic stress on tumor microenvironment. a Catecholamine and glucocorticoids accelerate tumorigenesis through promoting DNA damage, gene mutation and preventing tumor cells from autophagy and apoptosis. b Chronic stress promotes the premalignancy such as liver fibrosis and inflammatory bowel diseases through releasing IL-6 and IL-8. c Tumor cells in the microenvironment can be transformed into cancer stem cells(CSCs). d Chronic stress can suppress the anti-tumor immunity response through decreasing the numbers of cytotoxic T cells, dendritic cells(DCs),Natural Killer cells(NK cells) and increasing regular T cells and myeloid-derived suppression cells (MDSCs). e Chronic stress enhances the releasing of inflammatory factors including IL-6 and IL-8 and increases the number of monocytes to facility the inflammation. f Chronic stress advances tumor migration and metastasis via increasing the migration capability of tumor cells, regulating angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis and promoting the formation of tumor microenvironment

Cellular metabolism

Chronic stress exhibits certain effect on the metabolism of tumor cells. It was reported that chronic stress promoted a faster development of NAFLD by regulating lipid metabolism [46, 128]. Chronic stress-induced epinephrine could promote breast cancer stem-like properties via lactate dehydrogenase A-dependent (LDHA-dependent) metabolic rewiring, which increases the secretion of lactate and USP28-mediated stabilization of MYC [19]. GCs aid the body’s energy metabolism by regulating glucose and free fatty acids, and they maintain the energy homeostasis in liver and adipose tissues via regulating the lipid metabolism. The hypersecretion of GCs by the HPA axis in stress conditions advances the tumorigenesis and development by regulating proteins associated with lipid metabolism [129]. The purine metabolic disorder in CD4+ T cells after stress exposure triggers severe mitochondrial fission, which promotes the de novo synthesis of purine via IRF-1 accumulation in CD4+ T cells, subsequently leading to suppressed CD4+ T cell function and accelerated tumor formation [130]. Therefore, chronic stress correlates with tumor formation and development via regulating the metabolic activity in the body.

Other hormones

Other hormones induced by chronic stress could regulate tumorigenesis and development. As we mentioned above: dopamine is suppressive for tumor-angiogenesis [124]. γ-GABA is another inhibitory neurotransmitter that can block the formation of cAMP to inhibit the generation of tumor stem cells in NSCLC and subsequently impede tumor development [53]. Glutamate and neuropeptide-Y promote metastasis of tumor through direct suppression of the anti-tumor immune response [131]. Nicotine and its derivative participate in tumor formation, development and metastasis by stimulating the secretion of stress hormones from tumor cells [132]. The HPA-mediated up-regulation of thyroid hormones (THs) in mouse models of chronic restraint stress could lower the capability of T cells of proliferation and subsequently advance tumor development [133]. The CRF released by the hypothalamus increases the potentials of proliferation and invasion in breast cancer cells [134]. The increased production of leptin from adipocytes under the control of sympathetic nerves is suppressive for tumor growth [135]. Activation of 5-HT1D after stress exposure up-regulates FoxO6 expression by either transcriptional activation or interaction with phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 1 (PIK3R1) to activate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, thereby to promote the malignant progression of HCC [136]. 5-HT1D also stabilizes PIK3R1 by inhibiting its ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Our previous study proved that, increased secretion of Neuropeptide Y correlates with poor prognosis in prostate cancer patients. In addition, the stress-induced norepinephrine increased Neuropeptide Y secretion, which promoted infiltration of MDSCs and TAMs and concurrent IL-6 releasing, accelerating the malignant progression of tumor [137]. It has been reported that acute restraint stress increases the level of the plasma neuropeptide hormones, kisspeptin. Accordingly, administration of kisspeptin-10 significantly impairs T cell function through kisspeptin/GPR54 signaling pathway. Kisspeptin plays a nonredundant role in the stress-induced tumor immune evasion [138]. Other hormones induced by stress conditions are also involved in occurrence and development of tumors.

Treatment strategy

Blockage of β-AR

Given the involvement of neurotransmitters induced by chronic stress in the occurrence and development of tumor, β-AR antagonists are considered as effective agents against tumor with wide application prospectives [139, 140]. β-AR antagonists are inexpensive, safe and receive good adherence in patients [141]. β-AR antagonists significantly inhibit the progression of lung and breast cancers in animals [142, 143]. In addition, they enhance the efficacy of chemotherapeutic Topoisomerase I inhibitor SN-38 in neuroblastoma cells [144] and decrease the resistance of pancreatic cancer cells to Gemcitabine [145]. They could also regulate the activation of the Wnt signaling pathway [146]. The inhibition of β2-AR/β-arrestin-1 signaling pathway decreases the accumulation of DNA damage and subsequently inhibit tumor cell survival [147]. In clinical trials, β-AR antagonists were also shown to play a suppressive role in tumor progression. The blockade of β-AR signal delivery has been identified to decrease tumor burden [148] in hematologic tumor [149], prostate cancer [150], melanoma [151], pancreatic carcinoma [152] and neuroblastoma [144], to reduce metastasis of primary prostate cancer [153], and lower the recurrence of melanoma [154]. In triple-negative breast cancer, they also contribute to improved therapeutic outcomes with current treatments[155] and decrease the recurrence [156]. It was also reported that β-AR antagonists could suppress the growth, metastasis and recurrence in prostate and breast cancers [157, 158]. In addition β-AR antagonists are preferably used in children who received chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Those treatments are cardiotoxic and can cause hypertension or stroke in their later life [159]. Studies also reveals that β-AR antagonists reduce the cardiotoxicity of Trastuzumab [160, 161] and improve the efficacy of immunotherapies [162].

However, there are some reports holding the view that the β-AR antagonists had no benefit for suppression of tumor progression [163]. Based on our opinion, β2-AR antagonists’ anti-tumor effect is contributed from the increased β2-AR expression in tumor cells [63]. Given the complexity of the regulation of tumor biology between individuals upon chronic stress, a measurement for the expression level of stress hormone receptors in patients is recommended before clinical usage of their receptor antagonists.

There are some other agents targeting the HPA axis or the SNS, such as dopamine [124], COX-2 inhibitor [164, 165], that can be used to aid anti-tumor effects induced by β-AR antagonists. All of them receive good effects in both clinical trials and animal experiments (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical trials of beta-blocker in cancer patients and its outcomes

| Cancer type | Studies | Time | Drugs | Sample size | Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | Edoardo Botteri et al. [145] | 1997 | Beta blocker | 800 | BB intake was associated with a significantly decreased risk of BC-related recurrence |

| Amal Melhem-Bertrandt et al. [152] | 1995 | Beta blocker | 1413 | BB intake was associated with improved RFS in all patients with breast cancer and in patients with TNBC | |

| Rita Haldar et al. [94] | 2018 | Beta blocker | 38 | BB treatment reduced serum levels of the above pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as activity of multiple inflammation-related transcription factor | |

| Shaashua et al. [165] | 2017 | Beta blocker & COX 2 Inhibitor | 38 | BB intake combined with COX2 intake inhibiting multiple cellular and molecular pathways related to metastasis and disease recurrence in early-stage breast cancer | |

| Multiple myeloma | Knight et al. [146] | 2019 | Beta blocker (Propranolol) | 25 | Peri-Hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) propranolol inhibits cellular and molecular pathways associated with adverse outcomes. Propranolol is a potential candidate for adjunctive therapy in cancer-related treatment |

| Prostate cancer | Helene Hartvedt et al. [147] | 2000 | Beta blocker | 263 | BB use was associated with reduced PCa-specific mortality (HR: 0.14, 95% CI 0.02–0.85, P ¼ 0.032). No effect on overall mortality was seen (HR, all patients: 0.88, 95% CI 0.56–1.38, P ¼ 0.57) |

| Melanoma | Vincenzo De Giorgi et al. [148] | 2011 | Beta blocker | 30 patients with BB intake; 91 patients without BB intake | 1-year-long Beta Blockers treatment is associated with a reduced risk of progression of thick malignant melanoma (P = 0.002) |

| Hollestein et al. [151] | 2013 | Beta blocker | 709 | BB's intake has a significantly reduced hazard ratio of 0.47 (95% CI 0.32–0.68; P < 0.0001) or 0.87 (95% CI 0.78–0.98; P ¼ 0.01) for each year | |

| De Giorgi et al. [160] | 2018 | Beta blocker (Propranolol) | 53 | Use of propranolol at the time of diagnosis was significantly inversely associated with recurrence of melanoma with approximately an 80% risk reduction for propranolol users (hazard ratio, 0.18; 95% CI 0.04–0.89; P = 0.03) | |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | Chaudhary et al. [217] | 2019 | Beta blocker | 77 | Use of beta-blockers is associated with decreased distant metastases and potentially improved OS and DMFS |

| Ovarian cancer | Ramondetta et al. | 2019 | Beta blocker (Propranolol) | 32 | Use of propranolol during primary treatment of EOC is feasible and treatment resulted in decrease in markers of adrenergic stress response. In combination with chemotherapy, propranolol potentially results in improved QOL over baseline |

| Prostate cancer | Grytli et al. [95] | 2009 | Beta blocker | 655 | BB use was associated with reduced PCa-specific mortality in patients with high-risk or metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis |

Psychological intervention

Psychological intervention is a good approach to improve the psychological status and physical symptoms in patients [166, 167]. Roughly it can be divided into four therapies: cognitive–behavioral stress management, meaning-centered group psychotherapy, stress management and psychological counseling, and exercise-based stress reduction. All the therapies have been shown to increase the life quality of patients. Cognitive–behavioral stress management modifies the postoperative psychological status in women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. In the meantime, partial immune function recovered, and the pro-inflammatory reactions induced by chronic stress could be significantly reversed [168]. In the molecular level, psychological intervention leads to higher in vivo activity of NK cells while significant reductions in TNF-α and IL-6 levels [169–171]. However, such therapy is not significant in some male patients, probably due to less mood fluctuations in men [172]. Stress management and psychological counseling, such as the managing cancer and living meaningfully (CALM) therapy, was proven as an effective intervention to alleviate depressive symptoms in patients with advanced cancer [173]. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy leads to greater reductions in psychological or spiritual distress (such as anxiety and fear) in patients with advanced cancer [174]. Exercise intervention remarkably improves the quality of life in patients, and decrease tumor burden in mice [175]. Collectively, psychological intervention is an effective approach to improve the survival in patients. However, whether it is beneficial in suppressing tumor progression and eliminating tumor burden remains on debate. In despite of this, proper intervention or life management is still conducive to modifying unhealthy lifestyle habits, such as smoking, alcohol abuse and staying up. In addition, it might be promising to combine with β-AR antagonists in treatment for tumor, and relevant animal experiment and clinical trial are in demand (Table 2).

Table 2.

Psychosocial stress-reducing interventions in cancer patients and its outcomes

| Cancer type | Studies | Time | Intervention/Drugs | Sample size | Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate cancer | Wootten et al. [171] | 2014 | Self-guided online psychological intervention | 142 | The online psychological intervention called My Road Ahead combined with the online peer discussion forum had significantly improved reductions in distress compared with those who received access to the online intervention alone or the forum alone |

| Chambers et al. [174] | 2016 | Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) | 94 | MBCT in this format was not more effective than minimally enhanced usual care in reducing distress in men with advanced prostate cancer | |

| Advanced cancer | Rodin et al. [175] | 2016 | Managing cancer and living meaningfully (CALM) | 305 | CALM is an effective intervention that provides a systematic approach to alleviating depressive symptoms in patients with advanced cancer and addresses the predictable challenges these patients face |

| Breitbart et al. [176] | 2015 | Meaning-centered group psychotherapy | 253 | This large randomized controlled study provides strong support for the efficacy of MCGP as a treatment for psychological and existential or spiritual distress in patients with advanced cancer | |

| Breast cancer | Carayol et al. [177] | 2012 | Physical exercises | 17 | Exercise intervention improved fatigue, depression, and QoL in patients with breast cancer receiving adjuvant therapy. Prescription of relatively low doses of exercise (< 12 MET h/week) consisting in ∼ 90–120 min of weekly moderate physical exercise seems more efficacious in improving fatigue and QoL than higher doses. Key |

| Antoni et al. [170] | 2013 | Cognitive-behavioral stress management (CBSM) | 199 | A 10-week CBSM intervention can reverse anxiety-related up-regulation of pro-inflammatory gene expression in circulating leukocytes | |

| Witek Janusek et al. [172] | 2018 | Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) | 192 | MBSR provides not only psychological benefit, but also optimizes immune function supportive of cancer control | |

| Lengacher et al. [173] | 2016 | Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) | 322 | The MBSR(BC) program significantly improved a broad range of symptoms among BCSs up to 6 weeks after MBSR(BC) training, with generally small to moderate overall effect sizes |

Gut microbiota-based therapy

There is a significant association between chronic stress and the microbiota–gut–brain axis. Therefore, regulation for gut microbiota is expected to be a treatment against stress. The gut microbiota affects the level of colonic GCs involved in HPA axis regulation, and subsequent the systemic immune system, intestines, blood–brain barrier, microbial metabolism and the autonomic nerves system (ANS) [176, 177]. Early life stress results in an altered brain–gut axis, with hypersecretion of GCs, activation of the systemic immune response and a significant alteration of the fecal microbiota [178]. Selective complementation with fatty acid precursors or a strain of the Lactobacilli genus alleviates the depression phenotype [179]. Gut microbiome-derived lactate increases the anxiety-like behaviors through GPR81 receptor-mediated lipid metabolism [180]. Alteration of the gut microbiome composition is potentially effective for treatment of chronic stress. For instance, oral rifaximin alters the microbiome composition in the ileum (dominant Lactobacillus species) and prevents visceral hyperalgesia in response to chronic stress [181]. Caspase-1 inhibitor Minocycline ameliorates the depressive-like behaviors in mice exposed to stress through an increase in relative abundance of Akkermansia spp [182]. Xiaoyaosan, a traditional Chinese medicine prescription for treating depression, could slow cancer progression by ameliorating gut dysbiosis in mice having colorectal cancer xenografts and exposed to chronic stress [183]. Probiotics Clostridium butyricum relieves the visceral hypersensitivity in mice induced by chronic stress, and also remodels the microbiota to decrease the depressive behaviors [184]. In addition, prebiotic treatment significantly decreases the corticosterone and proinflammatory cytokine levels induced by chronic stress in mice, and subsequently alleviates depression-like behaviors [185]. Therefore, prebiotic/probiotic treatment might be a good option for alleviating stress reactions in tumor patients. However, the specific bacterial species required, administration dose and combination strategy require to be confirmed before clinical application.

Therapy targeting nerve fibers

Because of the crucial role of the SNS in chronic stress-induced tumorigenesis [186], anti-neuron treatment and nerve ablation might be options in treatment of chronic stress-related tumor. Studies prove that treatment targeting the nerve fibers was effective in suppressing tumor growth and metastasis in prostate cancer and gastric cancer [146, 187, 188]. Surgical or pharmacological denervation of the stomach in mice of gastric cancer markedly reduces tumor formation and malignant progression, enhances the systemic chemotherapeutic efficacy and prolonged the survival time [146]. Surgical denervation has been proven as a safe approach in patients with hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Most of the available drugs at present are used to target neurogenesis-related genes. The Wnt signaling pathway stimulates the release of neuron growth factors (NGF) to promote the growth of nerves in solid tumors [189]. Inhibition of NGF release has shown good clinical effect in treatment for pancreatic cancer [190]. Studies on anti-neuron treatment for tumor are mainly based on regulation of the NGF and precursor of nerve growth factor (proNGF) [191]. By comparison with other therapies, agents targeting NGF are well tolerated and safer. They are also effective in pain relief. Multiple NGF and its receptor blockers and antibodies are in development. Tanezumab is NGF antibody developed by Pfizer that has been applied in clinical trials for its analgesic activity in patients with chronic rheumatoid and back pain. In addition, NGF blockade is proven to effectively reduce the tumor-induced bone destruction in mouse models [192]. p73 is a transcription factor with a dual role in neuronal development and cancer. It could simultaneously induce neurodifferentiation and stem cell formation during melanoma progression and be potentially developed as a therapeutic target [193]. Moreover, as lateral hypothalamus (LH)–lateral habenula (LHb) synaptic potential is determinant in stress-induced depression, LH/LHb is served as another pair of potential therapeutic target in depression [194]. The current anti-neuron treatment is at an early stage and limited to animal studies. There is no clinical trial supporting the effect of targeting nerve fibers in human tumor growth [195], requiring further exploration.

Discussion

This review summarizes the research progress on chronic stress for its role in regulation of tumorigenesis and development. The specific role of GCs in the tumorigenesis and development requires further exploration. Given the anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive activities, GCs have been applied in clinic for treatment of tumor [196] or used as an adjunct to reduce the inflammatory reactions after immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [197]. The up-regulation of miR-708 induced by GCs receptor agonists is proven to remarkably inhibit the expression of inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit beta (IKKβ), suppress nuclear factor-kappa-B (NF-κB) activity and its downstream target genes (COX-2, cMYC, CD24 and CD44), which subsequently reduced tumor progression in breast cancer [198]. However, there were researches reporting the tumor promoting effect of GCs early in 2007, that is GCs and epinephrine cooperated to induce DNA damage and interfere with the repair in cells [199]. Elevated GCs during chronic restraint stress could mediate MDM2 activity and p53 function through the induction of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase (SGK1) [34]. GCs receptors is activated in the distant metastatic site in patients with breast cancer, and the high expression of the receptors were significantly associated with the shortening of the survival time in patients [196]. Depression-like behaviors could be induced with a significant elevation of GCs after chronic stress [200–202], and alleviated by decline of GCs [203, 204]. Low levels of GCs in early tumor onset in animals leads to accumulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines resulting in accelerated tumorigenesis [205]. After stress exposure, the elevation of GCs subverts therapy-induced anticancer immunosurveillance [206]. The dual role of GCs in tumor might be associated with the tumor heterogeneity, and others cells tumor microenvironment. Research reported that GCs could regulate tumorigenesis and development by either direct or indirect effects. While the direct inhibitory effects of GCs was inhibited by fat tissues [207]. More studies are required to support the regulation of tumor by GCs. In addition, we should be more cautious to apply GCs in clinic.

Catecholamine also has various effects during tumor progression. The stress-induced catecholamine has a tumor-promoting effect, while the exercise-induced epinephrine/norepinephrine can inhibit tumor development [208]. In a cohort study involving approximately 1.44 million people from the European and American countries, moderate to intense exercise decreases the risk of cancer formation, which has also been validated in multiple cancers, including breast cancer, colon cancer, rectal cancer, esophageal carcinoma, lung cancer, liver cancer, renal cancer, bladder cancer and head and neck cancer [209, 210]. A study in breast cancer reveals that 2-h acute exercise is superior to 6-month light exercise training in tumor suppression [211], indicatives a close relationship between the training intensity and the tumor-suppressive effect. Another study finds that wrist flexion exercise results in significantly elevated levels of epinephrine and norepinephrine, and concurrent inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and VEGF [212]. The activity of NK cells [213] and the number of CD8+ cells [214] after exercise are found to increase remarkably, which is opposite to the changing trend in chronic stress. An animal experiment where mice are allowed to exercise using a treadmill or toys, the activated β-AR/CCL2 could decrease the PD-L1 resistance to anti-tumor immune therapy, with concurrent significantly reduced tumor burden. Remarkably, the researchers states that low-concentration of catecholamine is observed as a tumor suppressor, and reversely high concentration shows the tumor promoting effect [215]. Cellular research demonstrated that the up-regulation of epinephrine and norepinephrine suppresses the growth of breast cancer cells by increasing the YAP expression involved in the Hippo signaling pathway [216]. It is also indicated that exercise could decrease the risk of premalignancy in inflammatory bowel disease [217]. All these studies suggest that the effect of catecholamine in tumorigenesis and development might be affected by hormone concentration, action site and other factors that are concurrently produced. The specific mechanism needs to be further investigated.

The molecular mechanism by which chronic stress regulates the tumorigenesis and development has not been well recognized. More comprehensive and in-depth studies are in demand to identify the action time of catecholamine, risk threshold for in vivo concentration, the optimal intervention time of receptor antagonist/psychological intervention, therapeutic outcome, and how the stress hormone receptor antagonists cooperate with other therapies to achieve the greatest benefit.

Acknowledgements

We would like to give our sincere gratitude to the reviewers for their constructive comments.

Authors’ contributions

CW,YMS and WWH contributed to writing this manuscript, CW and JPN contributed to searching for material. YY and WWH designed this manuscript. All authors listed have made a substantial contribution to the work. All authors have read and approved the article.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 82073280 to WWH). Seeking Outstanding Youth Program, Lingang Laboratory (No: LG-QS-202205-09 to WWH). The National Key New Drug Innovation Program, the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (No: 2018ZX09201017-006 to YY). New Drug Leading Scholar Program, China Pharmaceutical University (to YY).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

This manuscript has been approved for publication by all authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Chen Wang and Yumeng Shen are co-first authors.

Contributor Information

Weiwei Hu, Email: huweiwei@cpu.edu.cn.

Yong Yang, Email: yy@cpu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Chida Y, Sudo N, Takaki A, Kubo C. The hepatic sympathetic nerve plays a critical role in preventing Fas induced liver injury in mice. Gut. 2005;54:994–1002. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.058818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang K, Zhao XH, Liu J, Zhang R, Li JP. Nervous system and gastric cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2020;1873:188313. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.188313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen R, et al. Prostate cancer risk prediction models in Eastern Asian populations: current status, racial difference, and future directions. Asian J Androl. 2019;21:1–4. doi: 10.4103/aja.aja. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mravec B, Tibensky M, Horvathova L. Stress and cancer. Part I: mechanisms mediating the effect of stressors on cancer. J Neuroimmunol. 2020;346:577311. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2020.577311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Article R. Invited minireview: Stress-induced remodeling of lymphoid innervation. Bone. 2008;23:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.06.011.Invited. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 is required for chronic stress-induced immune suppression. NeuroImmunoModulation. 2013;21:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000354610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klopack ET (2022) Social stressors associated with age-related T lymphocyte percentages in older US adults : Evidence from the US Health and Retirement Study. 1–5 10.1073/pnas.2202780119/-/DCSupplemental.Published [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Jung S, et al. Autophagic death of neural stem cells mediates chronic stress-induced decline of adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive deficits. Autophagy. 2020;16:512–530. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2019.1630222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones R. Role of prefrontal cortex glucocorticoid receptors in stress and emotion. Bone. 2014;23:1–7. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1562.Multipotent. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sloan EK, et al. Social stress enhances sympathetic innervation of primate lymph nodes: Mechanisms and implications for viral pathogenesis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8857–8865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1247-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G, Yang HSQKSODT. Social temperament and lymph node innervation. Bone. 2005;23:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.10.010.Social. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanahan D. Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:31–46. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Androulidaki A, et al. Corticotropin releasing factor promotes breast cancer cell motility and invasiveness. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi M, et al. The β2-adrenergic receptor and Her2 comprise a positive feedback loop in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125:351–362. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0822-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saul AN, et al. Chronic stress and susceptibility to skin cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1760–1767. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker J, et al. Chronic stress accelerates ultraviolet-induced cutaneous carcinogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:919–922. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sloan EK, et al. The sympathetic nervous system induces a metastatic switch in primary breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7042–7052. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhi X, et al. Adrenergic modulation of AMPK-dependent autophagy by chronic stress enhances cell proliferation and survival in gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2019;54:1625–1638. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2019.4753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui B, et al. Stress-induced epinephrine enhances lactate dehydrogenase A and promotes breast cancer stem-like cells. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:1030–1046. doi: 10.1172/JCI121685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasegawa H, Saiki I. Psychosocial stress augments tumor development through β-adrenergic activation in mice. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2002;93:729–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2002.tb01313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biegler KA, Anderson AKL, Wenzel LB, Osann K, Nelson EL. Longitudinal change in telomere length and the chronic stress response in a randomized pilot biobehavioral clinical study: Implications for cancer prevention. Cancer Prev Res. 2012;5:1173–1182. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.James GD, Van Berge-Landry H, Valdimarsdottir HB, Montgomery GH, Bovbjerg DH. Urinary catecholamine levels in daily life are elevated in women at familial risk of breast cancer. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:831–838. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Putu D, Shoveller J, Montaner J, Feng C, Nicoletti R, Shannon K. Neural regulation of hematopoiesis, inflammation and cancer. Physiol Behav. 2016;176:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.01.026.Neural. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson EL, et al. Stress, immunity, and cervical cancer: Biobehavioral outcomes of a randomized clinical trail. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2111–2118. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang CH, Chen SJ, Liu CY. Risk of developing depressive disorders following hepatocellular carcinoma: a nationwide population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alonso C, et al. Maladaptive intestinal epithelial responses to life stress may predispose healthy women to gut mucosal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:163–172. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, et al. Chronic stress promotes gastric cancer progression and metastasis: an essential role for ADRB2. Cell Death Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2030-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barron TI, Connolly RM, Sharp L, Bennett K, Visvanathan K. Beta blockers and breast cancer mortality: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2635–2644. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang A, et al. β2-Adrenoceptors on tumor cells play a critical role in stress-enhanced metastasis in a mouse model of breast cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;57:106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armaiz-Pena GN, et al. Src activation by adrenoreceptors is a key switch for tumour metastasis. Nat Commun. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin Q, et al. Effect of chronic restraint stress on human colorectal carcinoma growth in mice. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roy S, et al. The role of p38 MAPK pathway in p53 compromised state and telomere mediated DNA damage response. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2018;836:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2018.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flint MS, Bovbjerg DH. DNA damage as a result of psychological stress: implications for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:3–5. doi: 10.1186/bcr3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng Z, et al. Chronic restraint stress attenuates p53 function and promotes tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:7013–7018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203930109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reeder A, et al. Stress hormones reduce the efficacy of paclitaxel in triple negative breast cancer through induction of DNA damage. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:1461–1470. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas M, et al. Impaired PARP activity in response to the β-adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol. Toxicol Vitr. 2018;50:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baritaki S, de Bree E, Chatzaki E, Pothoulakis C. Chronic stress, inflammation, and colon cancer: a CRH system-driven molecular crosstalk. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1669. doi: 10.3390/jcm8101669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei L, et al. Chronic unpredictable mild stress in rats induces colonic inflammation. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao X, et al. Chronic stress promotes colitis by disturbing the gut microbiota and triggering immune system response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E2960–E2969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720696115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu W, et al. Prolactin mediates psychological stress-induced dysfunction of regulatory T cells to facilitate intestinal inflammation. Gut. 2014;63:1883–1892. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melinder C, Hiyoshi A, Fall K, Halfvarson J, Montgomery S. Stress resilience and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study of men living in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2017;7:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mawdsley JE, Rampton DS. Psychological stress in IBD: new insights into pathogenic and therapeutic implications. Gut. 2005;54:1481–1491. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.064261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salvo-Romero E, et al. Overexpression of corticotropin-releasing factor in intestinal mucosal eosinophils is associated with clinical severity in Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-77176-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.March-Luján VA, et al. Impact of BMGIM music therapy on emotional state in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1591. doi: 10.3390/jcm10081591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han Y, et al. Hydrogen sulfide-mediated resistance against water avoidance stress-induced gastritis by maintenance of gastric microbial homeostasis. Microbiologyopen. 2020;9:1–18. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takada S, et al. Stress can attenuate hepatic lipid accumulation via elevation of hepatic β-muricholic acid levels in mice with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Lab Investig. 2021;101:193–203. doi: 10.1038/s41374-020-00509-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang X, et al. Chronic restraint stress decreases the repair potential from mesenchymal stem cells on liver injury by inhibiting TGF-β1 generation. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:1–10. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakade Y, Yoneda M, Nakamura K, Makino I, Terano A. Involvement of endogenous CRF in carbon tetrachloride-induced acute liver injury in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;282:1782–1788. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00514.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oben JA, et al. Hepatic fibrogenesis requires sympathetic neurotransmitters. Gut. 2004;53:438–445. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.026658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dubuisson L, et al. Inhibition of rat liver fibrogenesis through noradrenergic antagonism. Hepatology. 2002;35:325–331. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.31166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Article R. Role of the Microenvironment in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Bone. 2008;23:1–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.002.Role. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao W, et al. Activated hepatic stellate cells promote hepatocellular carcinoma development in immunocompetent mice. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2651–2661. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nasrullah M. (2016) Regulation of non small-cell lung cancer stem cell like cells by neurotransmitters and opioid peptides. Physiol Behav. 2018;176:139–148. doi: 10.1038/nn.4087.Stress. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bruffaerts R, Mortier PH, Kiekens G, Auerbach RP, Cuijpers P, Demyttenaere K, Green JG, Nock MK, Kessler RC. Nicotine induces self-renewal of pancreatic cancer stem cells via neurotransmitter-driven activation of sonic hedgehog signaling. Physiol Behav. 2017;176:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.10.003.Nicotine. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin XH, et al. Norepinephrine-stimulated HSCs secrete sFRP1 to promote HCC progression following chronic stress via augmentation of a Wnt16B/β-catenin positive feedback loop. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01568-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang B, et al. The stress hormone norepinephrine promotes tumor progression through β2-adrenoreceptors in oral cancer. Arch Oral Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2020.104712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sorrentino G, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor signalling activates YAP in breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2017 doi: 10.1038/ncomms14073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim SL, Choi HS, Kim JH, Lee DS. The antiasthma medication ciclesonide suppresses breast cancer stem cells through inhibition of the glucocorticoid receptor signaling-dependent YAP pathway. Molecules. 2020 doi: 10.3390/molecules25246028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.He L, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor signaling activates TEAD4 to promote breast cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2019;79:4399–4411. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu Z, et al. Stress-related hormone reduces autophagy through the regulation of phosphatidylethanolamine in breast cancer cells. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:149–149. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-8176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sood AK, et al. Adrenergic modulation of focal adhesion kinase protects human ovarian cancer cells from anoikis. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1515–1523. doi: 10.1172/JCI40802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hassan S, et al. Behavioral stress accelerates prostate cancer development in mice. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:874–886. doi: 10.1172/JCI63324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang D, et al. β 2-adrenoceptor blockage induces G 1/S phase arrest and apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells via Ras/Akt/NFκB pathway. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nasrullah M. (2016) Chronic variable stress activates hematopoietic stem cells. Physiol Behav. 2018;176:139–148. doi: 10.1038/nm.3589.Chronic. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dutta P, et al. Myocardial infarction accelerates atherosclerosis. Nature. 2012;487:325–329. doi: 10.1038/nature11260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Méndez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, Frenette PS. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature. 2008;452:442–447. doi: 10.1038/nature06685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Article R. Circadian control of the immune system. Bone. 2008;23:1–7. doi: 10.1038/nri3386.Circadian. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scheiermann C, Kunisaki Y, Lucas D, Chow A, Jang J, Zhang D, Hashimoto D, Merad MPSF. Adrenergic nerves govern circadian leukocyte. Immunity. 2013;37:290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.021.ADRENERGIC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Niraula A, Wang Y, Godbout JP, Sheridan JF. Corticosterone production during repeated social defeat causes monocyte mobilization from the bone marrow, glucocorticoid resistance, and neurovascular adhesion molecule expression. J Neurosci. 2018;38:2328–2340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2568-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Powell ND, et al. Social stress up-regulates inflammatory gene expression in the leukocyte transcriptome via β-adrenergic induction of myelopoiesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:16574–16579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310655110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Irwin MR, Cole SW. Reciprocal regulation of the neural and innate immune systems. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:625–632. doi: 10.1038/nri3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bondar T, Medzhitov R. The origins of tumor-promoting inflammation. CCELL. 2013;24:143–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hodge DR, Hurt EM, Farrar WL. The role of IL-6 and STAT3 in inflammation and cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2502–2512. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nilsson MB, et al. Stress hormones regulate interleukin-6 expression by human ovarian carcinoma cells through a Src-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29919–29926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611539200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shahzad MMK, et al. Stress effects on FosB- and interleukin-8 (IL8)-driven ovarian cancer growth and metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35462–35470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.109579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Armaiz-Pena GN, et al. Adrenergic regulation of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 leads to enhanced macrophage recruitment and ovarian carcinoma growth. Oncotarget. 2015;6:4266–4273. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sheean G, et al. (2008) Beta adrenergic blockade decreases the immunomodulatory effects of social disruption stress. Bone. 2013;23:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.011.Beta. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Qiao G, Chen M, Bucsek MJ, Repasky EA, Hylande BL. Adrenergic signaling: a targetable checkpoint limiting development of the antitumor immune response. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1–15. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sommershof A, Scheuermann L, Koerner J, Groettrup M. Chronic stress suppresses anti-tumor TCD8+ responses and tumor regression following cancer immunotherapy in a mouse model of melanoma. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;65:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Inbar S, et al. Do stress responses promote leukemia progression? an animal study suggesting a role for epinephrine and prostaglandin-e2 through reduced nk activity. PLoS ONE. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhao Y, et al. Depression promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression through a glucocorticoid-mediated upregulation of PD-1 expression in tumor-infiltrating NK cells. Carcinogenesis. 2019;40:1132–1141. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgz017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rosenne E. In vivo suppression of NK cell cytotoxicity by stress and surgery in F344 rats: glucocorticoids have a minor role compared to catecholamines and prostaglandins. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;23:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.12.007.In. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ayroldi E, Cannarile L, Adorisio S, Delfino DV, Riccardi C. Role of endogenous glucocorticoids in cancer in the elderly. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 doi: 10.3390/ijms19123774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhao J, et al. TLR2 involved in naive CD4+ T cells rescues stress-induced immune suppression by regulating Th1/Th2 and Th17. NeuroImmunoModulation. 2015;22:328–336. doi: 10.1159/000371468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Muthuswamy R, et al. Epinephrine promotes COX-2-dependent immune suppression in myeloid cells and cancer tissues. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;62:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lutgendorf SK et al (2014) Depressed and anxious mood and T-cell cytokine expressing populations in ovarian cancer patients. 131: 319–335 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.12.012.Depressed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Mohammadpour H, et al. Β2 adrenergic receptor-mediated signaling regulates the immunosuppressive potential of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Clin Invest. 2019;129:5537–5552. doi: 10.1172/JCI129502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mundy-Bosse BL, Thornton LM, Yang HC, Andersen BL, Carson WE. Psychological stress is associated with altered levels of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in breast cancer patients. Cell Immunol. 2011;270:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chakroborty D, Sarkar C, Basu B, Dasgupta PS, Basu S. Catecholamines regulate tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3727–3730. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thaker PH, et al. Chronic stress promotes tumor growth and angiogenesis in a mouse model of ovarian carcinoma. Nat Med. 2006;12:939–944. doi: 10.1038/nm1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xie H, et al. Chronic stress promotes oral cancer growth and angiogenesis with increased circulating catecholamine and glucocorticoid levels in a mouse model. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:991–997. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Aslam N, Nadeem K, Noreen RJAC. Adrenergic nerves activate an angio-metabolic switch in prostate cancer. Abeloff’s Clin Oncol. 2015;5(8):938–944. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liu GX, et al. Isoprenaline induces periostin expression in gastric cancer. Yonsei Med J. 2016;57:557–564. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2016.57.3.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Madel MB, Elefteriou F. Mechanisms supporting the use of beta-blockers for the management of breast cancer bone metastasis. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:1–18. doi: 10.3390/cancers13122887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Haldar R, et al. Perioperative inhibition of β-adrenergic and COX2 signaling in a clinical trial in breast cancer patients improves tumor Ki-67 expression, serum cytokine levels, and PBMCs transcriptome. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;73:294–309. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Moretti S, et al. Β-Adrenoceptors are upregulated in human melanoma and their activation releases pro-tumorigenic cytokines and metalloproteases in melanoma cell lines. Lab Investig. 2013;93:279–290. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pan C, et al. Depression accelerates gastric cancer invasion and metastasis by inducing a neuroendocrine phenotype via the catecholamine/β2-AR/MACC1 axis. Cancer Commun. 2021 doi: 10.1002/cac2.12198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Landen CN, et al. Neuroendocrine modulation of signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10389–10396. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bruffaerts R, Mortier PH, Kiekens G, Auerbach RP, Cuijpers P, Demyttenaere K, Green JG, Nock MK, Kessler RC. Stress impairs the efficacy of immune stimulation by CpG-C: potential neuroendocrine mediating mechanisms and significance to tumor metastasis and the perioperative period. Physiol Behav. 2017;176:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.02.025.Stress. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Haldar R, et al. Perioperative COX2 and β-adrenergic blockade improves biomarkers of tumor metastasis, immunity, and inflammation in colorectal cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2020;126:3991–4001. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Drell TL, IV, et al. Effects of neurotransmitters on the chemokinesis and chemotaxis of MDA-MB-468 human breast carcinoma cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;80:63–70. doi: 10.1023/A:1024491219366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Du P, et al. Chronic stress promotes EMT-mediated metastasis through activation of STAT3 signaling pathway by miR-337-3p in breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-02981-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shi M, et al. Catecholamine up-regulates MMP-7 expression by activating AP-1 and STAT3 in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yang EV, et al. Norepinephrine up-regulates the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, and MMP-9 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10357–10364. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]