Abstract

The recently developed prime-editing (PE) technique is more precise than previously available techniques and permits base-to-base conversion, replacement, and insertions and deletions in the genome. However, previous reports show that the efficiency of prime editing is insufficient to produce genome-edited animals. In fact, prime-guide RNA (pegRNA) designs have posed a challenge in achieving favorable editing efficiency. Here, we designed prime binding sites (PBS) with a melting temperature (Tm) of 42 °C, leading to optimal performance in cells, and we found that the optimal Tm was affected by the culture temperature. In addition, the ePE3max system was developed by updating the PE architecture to PEmax and expressing engineered pegRNA (epegRNA) based on the original PE3 system. The updated ePE3max system can efficiently induce gene editing in mouse and rabbit embryos. Furthermore, we successfully generated a Hoxd13 (c. 671 G > T) mutation in mice and a Tyr (c. 572 del) mutation in rabbits by ePE3max. Overall, the editing efficiency of modified ePE3max systems is superior to that of the original PE3 system in producing genome-edited animals, which can serve as an effective and versatile genome-editing tool for precise genome modification in animal models.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-023-05003-3.

Keywords: Prime editing, Editing efficiency, Mouse, Rabbit, Precise editing

Introduction

Prime editors can precisely introduce insertions, deletions and all 12 types of point mutations without the requirement for donor DNA templates or the creation of double-strand breaks (DSBs) [1]. The PE system consists of a fusion protein of nCas9 (H840A) and reverse transcriptase (RT), along with a pegRNA [1]. To date, PE systems have been successfully used in various organisms, including mice [2], zebrafish [3] and rabbits [4]. Liu and coworkers reported a frequency of base conversion mediated by the PE3 system at the Hoxd13 locus of mouse embryos ranging from 1.1 to 18.5% [2]. Similarly, Karl successfully introduced mutations in zebrafish embryos using PE, achieving frequencies up to 30% and even observing germline transmission [3]. Our previous study also demonstrated that the PE system was inefficient at the HBB and Tyr loci in rabbit embryos [4]. However, compared with the efficiency of 20–70% observed in mammalian cells, the efficiency of PE in embryos is too low to apply in animals.

Recently, several studies have reported four optimization strategies for improving the efficiency of PE. The first strategy focuses on optimizing the length of the pegRNA components to improve editing efficiency [5–8]. It has been shown that designing PBS with a Tm of 30 °C leads to optimal performance in rice [5]. In human cells, the optimal PBS Tm ranges from 35 to 40 °C, which results in a high editing efficiency [7]. This strategy provides a convenient way to choose the optimal pegRNA. The second strategy is based on engineered prime-editing guide RNAs (epegRNAs), which are generated by incorporating structured RNA motifs into the 3′ terminus of pegRNAs [8]. This strategy enhances pegRNA stability and prevents degradation of the 3′ extension. The third strategy is based on an optimized PE2 protein (PEmax) that harbors an SpCas9 variant with increased nuclease activity, additional nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequences, and a new linker between nCas9 and reverse transcriptase [6]. The fourth strategy is based on the inhibition of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) by an engineered MMR-inhibiting protein or by introducing same-sense mutations in pegRNA in cells [6, 9]. These studies prompted us to consider whether a combination of these strategies could enhance PE efficiencies in embryos.

Materials and methods

Animals

ICR mice and New Zealand white and Lianshan black rabbits were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of Jilin University (Changchun, China). All animal studies were conducted according to experimental practices and standards approved by the Animal Welfare and Research Ethics Committee at Jilin University.

Plasmid construction

The PE2, PEmax and PE4max plasmids were obtained from Addgene (#132,775, #174,820 and #174,828). The pegRNA and epegRNA oligos were synthesized by Sangon Biotech and cloned and inserted into the pBlyescriptSKII + U6-sgRNA (F + E) empty vector (Addgene #74,707) according to a previous study [10].

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T and N2a cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Meilun Biotechnology Co., Ltd) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, China) and incubated at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. The cells were seeded into six-well plates and transfected using Hieff TransTM Liposomal Transfection Reagent (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h, the cells were collected and used for genotyping by EditR [11]. All primers used for genotyping are listed in Table S5.

mRNA and gRNA preparation

The PE, PEmax and PE4max plasmids were linearized with NotI and transcribed in vitro using the HiScribe T7 ARCA (Anti-Reverse Cap Analog) mRNA kit (NEB). The pegRNA and epegRNAs were amplified and transcribed in vitro using the MAXIscript T7 kit (Ambion) and purified using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The sgRNA was synthesized by Genscript Biotech (Nanjing).

Microinjection of mouse zygotes and genotyping

Briefly, a mixture of mRNA (50 ng/μL) and sgRNA (30 ng/μL) was co-injected into the cytoplasm of pronuclear-stage zygotes. In each group, an average of approximately 20 zygotes were injected to test the base editing efficiency. The injected zygotes were transferred to potassium simplex optimized medium (KSOM) for culture at 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 100% humidity. Then, an injected single zygote was collected at the blastocyst stage. Genomic DNA was extracted in embryo lysis buffer 1% NP40 (Meilun Biotechnology Co., Ltd) at 56 °C for 60 min and then at 95 °C for 10 min in a Bio-Rad PCR Amplifier. Then, the extracted products were amplified by PCR [95 °C, 5 min for pre-degeneration; 42 cycles of (95 °C, 30 s; 58 °C, 30 s; 72 °C, 30 s); 72 °C, 5 min for extension] and identified by Sanger sequencing. All primers used for genotyping are listed in Table S5.

Estimation of editing frequency

EditR (https://moriaritylab.shinyapps.io/editr_v10/) [11] online software and the TIDEweb tool (https://tide.deskgen.com/) [12] were applied to estimate the editing frequency based on Sanger sequencing.

Off-target assay

Ten potential off-target sites (POTs) for Hoxd13 PegRNA, nine POTs for Tyr pegRNA, six POTs for Hoxd13 nick sgRNA and nine POTs for Tyr nick sgRNA were predicted to analyze site-specific edits according to Cas-OFFinder (http://www.rgenome.net/cas-offin-der/) [13]. Mutations were detected by deep sequencing via HiTOM analysis [14]. All primers employed for the off-target assay are listed in Tables S2 and S3.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

Dorsal skin from WT and mutant rabbits was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h, embedded in paraffin wax, and then sectioned to produce slides. The slides were stained with H&E and viewed under a Nikon ts100 microscope.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the means ± S.E.M.s from at least three individual analyses for all experiments. Data were analyzed by Student’s t test via GraphPad Prism software 8.0.1. A probability value smaller than 0.05 (P < 0.05) was considered statistically significant (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P 0.001; ****P < 0.0001).

Results

The effect of PBS Tm for pegRNA and epegRNA on prime-editing efficiency

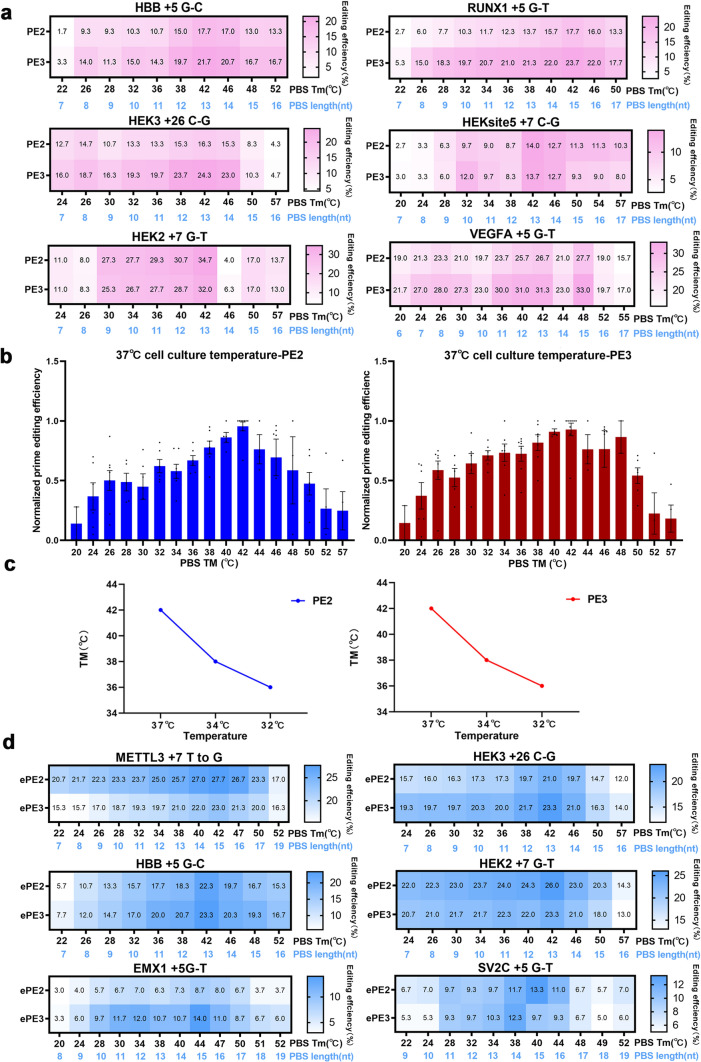

To choose the optimal pegRNA, we systematically evaluated the Tm to design optimal pegRNA. The editing efficiency of pegRNA with a PBS Tm ranging from 20 °C to 57 °C was tested in HEK293T cells using PE2 and PE3 at ten gene loci (Figs. 1a and S1a). The results indicated that PE2 and PE3 exhibited the highest efficiency when the PBS Tm was approximately 42 °C (Figs. 1a and S1a). We further conducted a comparison of the editing efficiency of PEs at various PBS Tm values for all ten targets and normalized the results. The analysis showed that PEs were most efficient at a PBS Tm of 42 °C, followed by 40 °C and 38 °C (Fig. 1b). Notably, this contrasts with findings in plant cells, where the optimal PBS Tm is 30 °C [5]. Based on differences in cultivation temperature requirements between mammalian and plant cells, we hypothesize that temperature may have an impact on the optimal PBS Tm.

Fig. 1.

Effect of the PBS Tm for pegRNA and epegRNA on prime-editing efficiency. a Comparison of the editing efficiencies of diverse PBS Tm values at six genomic loci. Data are shown as the mean with SEM, n = 3 independent experiments. b Normalized PE efficiencies using diverse PBS melting temperatures at the ten tested target sites. The highest editing efficiency was normalized to 1. c Comparison of the optimal PBS Tm at different cell culture temperatures. d PE editing efficiencies using epegRNAs at varying PBS Tm conditions

Then, we tested five loci to assess the effect of different cell culture temperatures on the optimal PBS Tm (Figs. S2a, S3a). The optimal PBS Tm decreased when the cell culture temperature was lowered to 34 or 32 °C compared to 37 °C (Fig. 1C). The normalized results indicated that the highest efficiencies were generally observed at a PBS Tm of 38 °C when the cell culture temperature was 34 °C (Fig. S2b) or at a PBS Tm of 36 °C when the cell culture temperature was 32 °C (Fig. S3b). Taken together, the results showed that the optimal PBS Tm temperatures decreased with decreasing cell culture temperatures (Fig. 1c).

Incorporating structured RNA motifs at the 3′ end of pegRNAs improves their stability and prevents degradation, thereby significantly enhancing prime-editing efficiency [8]. However, it remains unclear whether the PBS Tm of the epegRNA affects the editing efficiency. An epegRNA with the evopreQ1 motif showed a more significant effect on improving PE efficiencies in plants than an epegRNA with the mpknot motif [15, 16]. Thus, six epegRNAs with evopreQ1 were used to test the efficiency of ePE2 and ePE3. Surprisingly, the epegRNA exhibited high editing efficiency across a wide range of PBS Tms, where a Tm of approximately 42 °C resulted in the best effect (Fig. 1d). These findings suggest that the presence of structured RNA motifs at the 3′ terminus can potentially weaken the effect of the PBS Tm. Hence, the use of epegRNAs may reduce the need for exhaustive screening and can substantially advance the application scope of prime editing.

Generation of highly efficient gene editing in mouse and rabbit embryos by stacking various optimization strategies

Next, we tested whether the combination of these strategies could enhance PE efficiencies in embryos. We considered combining three protein architectures with four pegRNAs (Fig. 2a). PEmax optimized the PE protein, while PE4max included the addition of the MMR dominant negative MLH1 protein (MLH1dn). In addition, we incorporated epegRNA with evopreQ1 RNA motifs at the 3' end of pegRNAs, and spegRNA introduced an additional mutation in pegRNA based on the suggestion of Li and coworkers at one of five positions [9]. Furthermore, epegRNA introduced additional mutations that caused espegRNA (Fig. 2a). Since the PE3 system is more efficient than the PE2 system in mammalian cells, we chose PE3 for further testing. The 12 total obtained combinations were named PE3, sPE3, ePE3, esPE3, PE3max, sPE3max, ePE3max, esPE3max, PE5max, sPE5max, ePE5max and esPE5max (Fig. 2a). Four loci (CTNB1, Cola12, Hoxd13 and Ifnar) were selected for testing the efficiency of these 12 combinations in N2a cells. The results indicated that spegRNA improved PE efficiency at CTNB1 and Ifnar but reduced editing efficiency at the Cola12 site. This suggested a need to test different mutation positions, although we only tested the introduction of an additional mutation at position 1 (counting the 3′-base of RTT as position 1) [9] (Figs. 2b and S4a). Furthermore, the use of epegRNA led to a significant improvement in the efficiency of PE editing (Figs. 2b and S4a). However, the espegRNA combination did not further improve the editing efficiency (Figs. 2b and S4a). PE3max and PE5max did not exhibit significant enhancement effects except at the Hoxd13 site. However, when used in combination with epegRNA, the efficiency of editing was further enhanced (Figs. 2b and S4a). Our results indicated that ePE3max and ePE5max significantly improved prime-editing efficiency in N2a cells, thus, they were chosen for subsequent research.

Fig. 2.

Highly efficient gene editing in mouse and rabbit embryos by ePE3max. a Diagram of PE3, sPE3, ePE3, esPE3, PE3max, sPE3max, ePE3max, esPE3max, PE5max, sPE5max, ePE5max and esPE5max. b Comparison of the editing efficiencies of 12 combinations in the N2a cell line. c Frequencies of gene editing using PE3, ePE3max and ePE5max at four sites in mouse embryos. d Frequencies of gene editing using PE3, ePE3max and ePE5max at four sites in rabbit embryos

Then, we focused on efficient ePE3max and ePE5max in mouse embryos, with conventional PE3 serving as the control. We observed highly efficient editing at the four sites in N2a cells using ePE3max and ePE5max. However, in mouse embryos, only ePE3max was effective at all four sites, with an efficiency ranging from 6 to 59% (Figs. 2c and S5). The PE3 system mediated gene editing at Cola12 and Ifnar sites with an efficiency ranging from 12 to 34% but no desired editing activity at CTNB1 and Hoxd13 loci (Figs. 2c, S5). In contrast, ePE5max did not exhibit any desired editing activity at the four loci. Therefore, our results suggest that ePE3max is more effective in mouse embryos.

Similarly, four loci (HEXA, Tyr, HBB and Flad-1) were selected for testing ePE3max and ePE5max in rabbit embryos (Fig. 2d). It is worth noting that in our previous study, the PE3 system was inefficient at Tyr and HBB [4]. Consistent with these findings, the PE3 system successfully edited the HEXA site, exhibiting editing efficiencies ranging from 4.1 to 16.1%, but no desired editing activity was observed at the HBB, Tyr, and Flad-1 sites (Figs. 2d and S6). ePE3max was effective at all four sites, with an efficiency ranging from 5.2 to 93.5% in rabbit embryos (Figs. 2d and S6). ePE5max was observed to be efficient except at the HBB site, with an efficiency ranging from 1.1 to 91.2% (Figs. 2d and S6). The results suggest that ePE3max is more effective in rabbit embryos.

These results indicated that, compared to PE3 and ePE5max, the ePE3max system showed a higher editing efficiency in mouse and rabbit embryos. This finding further suggested the potential application of ePE3max for constructing animal models for human genetic diseases.

ePE3max can induce efficient prime editing in mice and rabbits

To test ePE3max efficiency in animals, Hoxd13 (c. 671 G > T) and Tyr (c. 572 del) were selected for targeted prime editing mediated by ePEmax3 in mice and rabbits (Fig. 3a, d). A previous study showed that the efficiency of PE3-mediated mutations in Hoxd13 was less than 10% in mice [2]. Similarly, the low PE3 system efficiency at the Tyr site made it unsuitable for embryo transfer in our previous study [4]. Hoxd13 mutation can lead to the pathogenesis of syndactyly disease, an autosomal dominant disease [17]. One of 3 mouse pups carried the desired Hoxd13 heterozygous mutation, with an editing efficiency of 43% (Fig. 3b). Unfortunately, the heterozygous mouse died within 2 days after birth and exhibited finger fusion (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Highly efficient gene editing in mice and rabbits by ePE3max. a Target sequence at the mouse Hoxd13 locus. PAM region (red) and target mutation (blue). b Sanger sequencing chromatograms of DNA from WT and mutant mice (#1). The red arrow indicates the mutant nucleotide. c Syndactyly phenotypes were determined in the #1 mutant mouse. d The target sequence at the rabbit Tyr (c. 572 del) locus. PAM region (red). e Sanger sequencing chromatograms of DNA from WT and mutant rabbits (#1, #2, and #3). The red arrow indicates the mutant nucleotide. f Photograph of F0 rabbits at 2 days. g H&E staining of dorsal skin from WT, #1 and #3 rabbits. The black arrows highlight melanin in the basal layer of the epidermis of WT and #1 chimera rabbits. Scale bars 100 μm

The Tyr mutation is a causal genetic mutation responsible for human ocular albinism (OA) and oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) [18]. OCA1 is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by reduced or absent melanin pigment in the skin, hair, and eyes due to deficient tyrosinase catalytic activity [19]. Three kits carrying desired Tyr mutations were obtained, and targeted deep sequencing showed that the mutation efficiencies in pups #1, #2 and #3 were 70.46%, 86.35% and 100%, respectively (Fig. 3e). Moreover, one homozygous mutant (#3) exhibited a complete albino phenotype, and the chimeric mutants (#1 and #2) exhibited a mosaic distribution of black and white skin and hair, which was consistent with their mutant genotype (Fig. 3f). Furthermore, histological H&E staining revealed the local or complete absence of melanin in the skin of representative #1 or #3 mutants (Fig. 3g).

To determine off-target mutations in PE-edited mice and rabbits, we used Cas-OFFinder to predict potential off-target sites of pegRNA and nick sgRNA for Hoxd13 and Tyr targets with less than three nucleotide mismatches in the genomes of mice and rabbits. Strikingly, no mutations were detected at the potential off-target site (Fig. S7), indicating the efficiency and precision of PE in mice and rabbits. These results showed that ePE3max could induce efficient gene editing and can serve as a promising prime-editing tool for the generation of mouse and rabbit disease models.

Discussion

Insufficient editing efficiencies have largely limited the application of PE systems in the construction of genome-edited animals. In this study, we demonstrated that the PBS Tm of pegRNA affects the editing efficiency and found that the optimal Tm was affected by the culture temperature. Then, we tested various strategies for increasing the prime-editing efficiency in N2a cells, and ePE3max and ePE5max showed a significantly improved editing efficiency. However, only ePE3max exhibited a relatively high editing efficiency in mouse and rabbit embryos. Our results indicated that optimized ePE3max achieves an outstanding editing frequency and targeting precision in inducing mutations in mice and rabbits.

PegRNA contains a spacer that specifies the target site, an sgRNA scaffold and a 3′ extension that contains a PBS sequence and an RT template for introducing the desired edits. The PBS is complementary to part of the spacer region that may cause pegRNA circularization, which may hamper the prime-editing process. We reasoned that temperature may affect the formation and breaking of hydrogen bonds, thereby affecting the structure and stability of RNA. At the optimal temperature, the combination of DNA, sgRNA and PBS can achieve a balance, thereby promoting gene editing by PE. Although the optimal PBS Tm for the epegRNA is also 42 °C, its effect on editing efficiency is not significant over a wide range. The results suggest that the structured RNA motif not only protects against pegRNA degradation but also weakens spacer and PBS circularization. Thus, epegRNA is more conducive to actual promotion and application because its use means that it is no longer necessary to test the efficiency of various PBS and RT template combinations. However, some more structured motifs have been shown to enrich epegRNA, such as the Csy4 recognition site [20], xrRNA [21] and G-quadruplexes [22]. It is necessary to determine the most efficient motif through future testing.

The overexpression of MLH1dn can increase prime-editing efficiency in cells, but it is less effective in embryos. The PEmax architecture has a length of 6.4 kb. Upon the addition of MLH1dn, the vector has a length of more than 8.7 kb; thus, the coding sequence is too large for in vitro transcription. In addition, we noted the efficiency difference of ePE5max in mouse and rabbit embryos, suggesting that prime-editing differences exist between species. In addition, we need to better understand how cell state and/or cell type can influence prime-editing efficiency and how different DNA repair mechanisms result in efficient or ineffective prime editing.

In summary, the utilization of ePE3max greatly enhances the editing efficiency of the PE system in mouse and rabbit models and holds significant promise as a valuable tool for constructing animal models.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Peiran Hu and Nannan Li for assistance at the Embryo Engineering Center for critical technical assistance.

Author contributions

ZL, LL, and YQ conceived and designed the experiments. YQ, DW, and WN performed the experiments. YQ, JL and DZ analyzed the data. XG, ZS, MW and YQ contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. ZL, YQ and ZZ wrote the paper. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31970574).

Availability of data and materials

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in this article are represented fully within the article or can be provided by the authors upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All the procedures using mice and rabbits were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Jilin University.

Consent for publication

All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yuqiang Qian, Di Wang and Wenchao Niu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Liangxue Lai, Email: lai_liangxue@gibh.ac.cn.

Zhanjun Li, Email: lizj_1998@jlu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Anzalone AV, Randolph PB, Davis JR, Sousa AA, Koblan LW, Levy JM, et al. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature. 2019;576(7785):149–157. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1711-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y, Li X, He S, Huang S, Li C, Chen Y, et al. Efficient generation of mouse models with the prime editing system. Cell Discov. 2020;6:27. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0165-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petri K, Zhang W, Ma J, Schmidts A, Lee H, Horng JE, et al. CRISPR prime editing with ribonucleoprotein complexes in zebrafish and primary human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40(2):189–193. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-00901-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qian Y, Zhao D, Sui T, Chen M, Liu Z, Liu H, et al. Efficient and precise generation of Tay-Sachs disease model in rabbit by prime editing system. Cell Discov. 2021;7(1):50. doi: 10.1038/s41421-021-00276-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin Q, Jin S, Zong Y, Yu H, Zhu Z, Liu G, et al. High-efficiency prime editing with optimized, paired pegRNAs in plants. Nat Biotechnol. 2021;39(8):923–927. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-00868-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen PJ, Hussmann JA, Yan J, Knipping F, Ravisankar P, Chen PF, et al. Enhanced prime editing systems by manipulating cellular determinants of editing outcomes. Cell. 2021;184(22):5635–52.e29. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhuang Y, Liu J, Wu H, Zhu Q, Yan Y, Meng H, et al. Increasing the efficiency and precision of prime editing with guide RNA pairs. Nat Chem Biol. 2022;18(1):29–37. doi: 10.1038/s41589-021-00889-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson JW, Randolph PB, Shen SP, Everette KA, Chen PJ, Anzalone AV, et al. Engineered pegRNAs improve prime editing efficiency. Nat Biotechnol. 2022;40(3):402–410. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-01039-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Zhou L, Gao BQ, Li G, Wang X, Wang Y, et al. Highly efficient prime editing by introducing same-sense mutations in pegRNA or stabilizing its structure. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1669. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29339-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Z, Chen S, Shan H, Zhang Q, Chen M, Lai L, et al. Efficient and precise base editing in rabbits using human APOBEC3A-nCas9 fusions. Cell Discov. 2019;5:31. doi: 10.1038/s41421-019-0099-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kluesner MG, Nedveck DA, Lahr WS, Garbe JR, Abrahante JE, Webber BR, et al. EditR: a method to quantify base editing from sanger sequencing. CRISPR J. 2018;1(3):239–250. doi: 10.1089/crispr.2018.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brinkman EK, Chen T, Amendola M, van Steensel B. Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(22):e168. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bae S, Park J, Kim JS. Cas-OFFinder: a fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2014;30(10):1473–1475. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Q, Wang C, Jiao X, Zhang H, Song L, Li Y, et al. Hi-TOM: a platform for high-throughput tracking of mutations induced by CRISPR/Cas systems. Sci China Life Sci. 2019;62(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11427-018-9402-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou J, Meng X, Liu Q, Shang M, Wang K, Li J, et al. Improving the efficiency of prime editing with epegRNAs and high-temperature treatment in rice. Sci China Life Sci. 2022;65(11):2328–2331. doi: 10.1007/s11427-022-2147-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Chen L, Liang J, Xu R, Jiang Y, Li Y, et al. Development of a highly efficient prime editor 2 system in plants. Genome Biol. 2022;23(1):161. doi: 10.1186/s13059-022-02730-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai L, Liu D, Song M, Xu X, Xiong G, Yang K, et al. Mutations in the homeodomain of HOXD13 cause syndactyly type 1-c in two Chinese families. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e96192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oetting WS, Mentink MM, Summers CG, Lewis RA, White JG, King RA. Three different frameshift mutations of the tyrosinase gene in type IA Oculocutaneous albinism. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;49(1):199–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spritz RA, Oh J, Fukai K, Holmes SA, Ho L, Chitayat D, et al. Novel mutations of the tyrosinase (TYR) gene in type I oculocutaneous albinism (OCA1) Hum Mutat. 1997;10(2):171–174. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)10:2<171::AID-HUMU11>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Yang G, Huang S, Li X, Wang X, Li G, et al. Enhancing prime editing by Csy4-mediated processing of pegRNA. Cell Res. 2021;31(10):1134–1136. doi: 10.1038/s41422-021-00520-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang G, Liu Y, Huang S, Qu S, Cheng D, Yao Y, et al. Enhancement of prime editing via xrRNA motif-joined pegRNA. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1856. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29507-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Wang X, Sun W, Huang S, Zhong M, Yao Y, et al. Enhancing prime editing efficiency by modified pegRNA with RNA G-quadruplexes. J Mol Cell Biol. 2022 doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjac022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in this article are represented fully within the article or can be provided by the authors upon request.