Abstract

Accumulating evidences suggest that M2 macrophages are involved with repair processes in the nervous system. However, whether M2 macrophages can promote axon regeneration by directly stimulating axons nor its precise molecular mechanism remains elusive. Here, the current study demonstrated that typical M2 macrophages, which were generated by IL4 simulation, had the capacity to stimulate axonal growth by their direct effect on axons and that the graft of IL4 stimulated macrophages into the region of Wallerian degeneration enhanced axon regeneration and improved functional recovery after PNI. Importantly, uPA (urokinase plasminogen activator)-uPA receptor (uPAR) was identified as the central axis underlying the axon regeneration effect of IL4 stimulated macrophages. IL4 stimulated macrophages secreted uPA, and its inhibition abolished their axon regeneration effect. Injured but not intact axons expressed uPAR to be sensitive to uPA. These results unveil a cellular and molecular mechanism underlying the macrophage related axon regeneration and provide a basis of a novel therapy for PNI.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-022-04310-5.

Keywords: Peripheral nerve injury, Macrophage, Axon regeneration, Urokinase plasminogen activator, Interleukin-4

Introduction

Accumulating evidence shows that inflammation is indispensable for tissue regeneration in various organs [1–3], including the peripheral nervous system (PNS) [4] and the central nervous system (CNS) [5]. For instance, the infiltration of macrophages in the region of Wallerian degeneration (WD) is necessary for myelin clearance after spinal cord injury (SCI) as well as peripheral nerve injury (PNI) [6]. Knock out of C–C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2), the receptor for major chemokine; C–C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), abolished macrophage accumulation around dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons and in the region of WD after PNI, resulting in reduced conditioning lesion effects and decreased myelin clearance [7]. Previous studies have revealed that macrophages can be divided into two functional subgroups, M1 and M2. M1 macrophages promote inflammation and tissue destruction, whereas M2 macrophages are anti-inflammatory and promote vascularization and repair process [8–12]. Although recent studies indicate that this M1/M2 nomenclature is too simple to explain complexed immunological phenomenon in vivo [13, 14], reported evidences suggest that a certain type of macrophages or M2-like macrophages can promote the repair process in the nervous system. For example, macrophages activated with zymosan stimulated axon regeneration after SCI with concurrent neurotoxicity [15]. Macrophages differentiated with IL4 stimulation-induced neurite outgrowth of cultured neurons on the inhibitory substrate [16]. When peripheral nerve defect was reconstructed with the scaffold to release IL4, this scaffold induced more CD206, one of the typical M2 markers, expressing macrophages, Schwann cell migration, and axon regeneration, compared to the control scaffold [17]. Lentiviral delivery of chondroitinase ABC into the injured spinal cord increased CD206 expressing macrophages and modulated secondary injury processes [18]. However, whether M2 macrophages can promote axon regeneration by directly stimulating axons nor its precise molecular mechanism remains elusive. Thus, the purposes of the current study are to determine whether M2 macrophages can promote axon regeneration after PNI and to elucidate its molecular mechanism. Here, the current study demonstrated that typical M2 macrophages, which were generated by IL4 simulation, had the capacity to stimulate axonal growth by their direct effect on axons and that the graft of IL4 stimulated macrophages (IL4-MΦ) into the region of WD enhanced axon regeneration and improved functional recovery after PNI. Importantly, it was suggested that uPA-uPAR could be the central axis underlying the axon regeneration effect of IL4-MΦ.

Methods

Animals

Animals had free access to food and water throughout the study. Adult LEWIS rats (Wild-type, Charles River Laboratories Japan, Inc.) were used in this study. All procedures involving animals were approved by the local ethical committee of the Hokkaido University. IL4-MΦ were prepared from syngeneic adult LEWIS-Transgenic (CAG-Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (EGFP) rats supplied by the National BioResource Project (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan). If not specified, 10 to 16 weeks old male or female rats (180 to 300 g) were used. For animal anesthesia, a mixture of ketamine (75–100 mg/kg, KETALAR® Daiichi Sankyo Propharma Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and medetomidine (0.5 mg/kg, DOMITOR®, Orion Corporation, Espoo, Finland) was administered intraperitoneally.

Cell preparation

Macrophages for the graft experiments were prepared from peritoneal macrophages of transgenic adult LEWIS rats that ubiquitously expressed GFP. Macrophages were harvested according to a modified protocol described previously [19]. Injection of 10 mL of 4% thioglycolate medium (Thyoglicollate Medium, Brewer Modified, BD Bioscience, NJ, USA) was performed into the peritoneum of rats, followed by repeating the injection the next day. Five days later, peritoneal cells were harvested after the injection of PBS into the peritoneal cavity. The collected cells were incubated for 3 h with the macrophage medium RPMI1640 (Nacalai Tesque, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (PS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). After removing non-adherent cells, IL4 (Peprotech, NJ, USA, # 400–04, 100 ng/mL) was added to the medium for induction of IL4-MΦ. For IFNγ-MΦ induction, IFN-γ (Peprotech, 300–02, 100 ng/mL) and LPS (Sigma-Aldrich, St Luis, MO, L4391, 100 ng/mL) were added at the same time as IL4 [9, 20]. The next day, the medium was replaced with a fresh medium, followed by the collection of adherent cells, IFNγ-MΦ or IL4-MΦ, one day later.

Surgical procedures

Crush injury model

Anesthetized rats were placed in a prone position, and a longitudinal 3 cm incision was applied on the right thigh to expose the sciatic nerve. A crush injury was made distal to the sciatic notch with micro-mosquito forceps (Fine Science Tools, No. 13010–12, Canada), followed by loosely stitching the epineurium at the injury site with a 10–0 nylon suture to mark the injury site.

Acellular model

A rat sciatic nerve acellular model was established as described previously [21]. In brief, two crush injuries were made with a 25 mm interval, followed by five rounds of repeated freezing with liquid nitrogen and spontaneous thawing.

Graft procedures

To test the efficacy of the syngeneic IL4-MΦ graft, 0.5 million macrophages in 10 μL PBS or only 10 μL PBS were grafted into the acellular region using four injections with a 34-gauge needle and a NanoFil syringe (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FI) as described previously [21]. The experiment consisted of three groups: (1) IL4-MΦ grafts, (2) IFNγ-MΦ grafts, and (3) no cell grafts (n = 6 per group). Two weeks after the cell grafts, the rats were perfused for histological assessment. For the experiment of the IL4-MΦ grafts in the crush injury model, 0.5 million cells in 10 μL PBS were grafted at 7.5 mm and 17.5 mm distal to the injury site at the time of nerve injury and 5 days after injury. The tested groups were (1) IL4-MΦ grafts injected twice, (2) IL4-MΦ graft injected once, and (3) PBS injection twice (n = 6 per group). Two weeks after the cell grafts, the rats were perfused. For the experiment evaluating functional recovery, 0.5 million IL4-MΦ were grafted three times at the same time of injury, 3 days, and 7 days after injury. The experiment consisted of two groups, IL4-MΦ grafts and PBS injections (n = 10 per group). To maximize the therapeutic effect of IL4-MΦ, IL4-MΦ were grafted 3 times, and injection sites were designed to match their location to regenerating axons.

BC11 injection

To investigate the effect of the blockade of uPA on axon regeneration induced by IL4-MΦ, BC11 hydrobromide (5.82 μg/mL) was co-injected with 0.5 million IL4-MΦ in 10 μL PBS into the rat sciatic nerve acellular model described above. As a control, 0.5 million IL4-MΦ were injected (n = 5 per group). Two weeks after the grafting, rats were perfused for histological analysis.

Histology

For immunohistochemistry, rats were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 mol/m3 phosphate buffer (PB), followed by nerve dissection and overnight fixation with 4% PFA at 4 °C. The nerves were then immersed in PB containing 30% sucrose in 0.1 mol/m3 PB and stored until sectioning. Nerves were longitudinally sectioned with a cryostat at 14-μm intervals and directly mounted on 10 slides in order. For immunocytochemistry, cultured cells were fixed with 4% PFA in 0.1 mol/m3 PB for 15 min.

Fixed cells or sections were blocked and permeabilized using 5% donkey serum containing 0.125% Triton X for 1 h and incubated overnight with primary antibodies against β-III tubulin (1:1000, rabbit from Covance, Princeton, NJ, USA), CD68 (1:500, mouse from Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), pNF (1:1000, mouse from BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), GFP(1:2000, chicken from Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), and uPAR (1:100, rabbit from Abcam) at 4 °C. For detecting axons in the acellular model, pNF was used to follow the developed protocol [21]. After washing with tris-buffered saline, sections were incubated with Alexa fluorochrome-conjugated donkey secondary antibodies (1:1000, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) and DAPI for 1 h at room temperature. For evaluation of remyelinating axons, rats were perfused with 4% PFA, followed by 2.5% glutaraldehyde. The most distal portion of the sciatic nerves was embedded in epoxy resin and sectioned axially at 1 μm, followed by staining with toluidine blue. Images were taken using an all-in-one microscope (Keyence BZ-X800, Osaka, Japan) or confocal laser microscope (Olympus FV-1000, Tokyo, Japan).

Quantification of macrophages and axons

Quantification of axons was performed as described previously [21]. Briefly, three consecutive sections on the same slide from the middle part of the nerve were used. Lines perpendicular to sections were set at the quantification points, and axons crossing each line were counted. For normalization, the sum of the axon numbers in the three sections was divided by the sum of the length of each line as the axon density. To calculate the percentage of axon regeneration, the axon density at each point was divided by the density at the uninjured site, which was 1.5 mm proximal to the injury site. To quantify the number of myelinated axons, 20 μm wide rectangular region was set to cross the center of both the tibial and peroneal parts of the sciatic nerve, and the number of myelinated axons was counted, and divided by the region area to calculate the density of myelinating axons per square millimeter. All quantification was performed in a blind fashion by concealing group identity.

Neurite outgrowth assay

Culture of DRG neurons

10–12 weeks old male or female rats (180 to 250 g) were used. Adult neurons from lumbar 4, 5, and 6 DRGs were used. For the preparation of pre-injured DRGs, rats were subjected to sciatic nerve transection a week prior to dissection. DRG neurons were cultured as described previously [22]. In brief, dissected DRGs were cut into 1 mm pieces and incubated in enzyme-containing medium consisting of DMEM/ Ham’s F-12 with 1% collagenase XI (Sigma-Aldrich, St Luis, MO) for 1 h at 37 °C. After replacing the enzyme-containing medium with 1 mL neuron culture medium consisting of DMEM/HAM’s F-12 supplemented with 2% B27 supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and 1% PS, the DRG pieces were triturated 20 times with a 1-mL pipette. Ten thousand DRGs were seeded per well in a 48-well plate. After 3 h of incubation in the neuron culture medium, half of the medium was replaced with M1 and M2 CM, followed by PFA fixation 21 h later. To make macrophage CM, IL4-MΦ and IFNγ-MΦ were cultured in a neuron culture medium for 12 h. The culture medium was then centrifuged (500 g, 5 min, and 4 °C), and the supernatant was collected as CM. Neurite elongation was detected by immunolabeling against β-III tubulin. Neurites were traced and measured using Image J [23] with the plugin software, Neuron J, as described previously [22, 24, 25]. More than 100 neurons per well were randomly selected, and the average longest neurite length was calculated. Three wells per condition were analyzed.

Culture with uPA or uPA inhibitor

To test the efficacy of uPA signaling, pre-injured lumbar DRG neurons were cultured in the neuron culture medium for 3 h, followed by the addition of uPA (0.75 μg/mL, Cloud-Clone Corp., TX, USA) with or without uPA specific inhibitor, BC11 hydrobromide (5.82 μg/mL, BC11, Biotech, MN, USA). To test the blockade of uPA in macrophage-derived CM, pre-injured lumbar DRG neurons were cultured with the neuron culture medium for 3 h, followed by the replacement of half the medium with the macrophage CM with or without BC11 (5.82 μg/mL). Neurons were fixed for 21 h to measure neurite outgrowth.

Western blotting

Ten ul of macrophage-derived CM was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Immobilon-P Membrane; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Membranes were blocked with 5% powdered milk (< 1% fat) and PBS for 1 h at room temperature on an orbital shaker and incubated overnight with primary antibodies: anti-uPA (1:125 rabbit from Cloud Clone Corp., Princeton, TX, USA), anti-IL10 (1:2000 mouse from R&D systems, MN, USA), or anti-IL6 (1:200 goat from Novus Bio, CO, USA). Unlike cell lysates, an internal control such as beta-actin and GAPDH was not available for Western blotting of CM. After washing, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1000, Novus Biologicals) for 1 h at room temperature. The bands were visualized using Ez WestLumi Plus (ATTO, Tokyo, Japan) and Quantity One v. 4.6.9 (Bio-Rad) software.

Behavioral analyses

Adult female LEWIS rats (8–10 weeks old, 160 to 220 g) were used, and all analyses were performed in a blind fashion. Gait and sensory analyses were performed at pre-injury, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks after injury.

Gait performance

Before evaluating baseline functions, rats were habituated to the apparatus for functional assessment for a week. The rats ran on the treadmill of the DigiGait Imaging System (Mouse Specific, Inc., MA, USA) for gait analysis as described previously [26]. Five trials were performed, and the average of three trials was divided by the value at pre-injury.

Sensory function

Sensory function was assessed using the electric Von Frey test and the Hargreaves test [27–31]. Mechanical thresholds of the hind paw were measured using a Dynamic Plantar Aesthesiometer (Ugo Vasil, Varese, Italy). Von Frey filaments with bending forces of 0 to 50 g were applied on the hind paw over a period of 20 s at a rate 2.5 g/s. The duration from stimulus to the withdrawal of the paw was recorded. A test consisted of three trials, and the average time was used for analysis. Thermal thresholds in the hind paw were evaluated using a Hargreaves device (Ugo Basile, Varese, Italy). Heat stimulus was applied on the paw for 10 s from 35 to 70 °C in intervals of 2.5 °C until paw withdrawal [32]. The average time of the three trials was used for analysis.

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological analysis was performed at 8 weeks postoperatively using Neuropack MEB-9102 (NihonKohden, Tokyo, Japan). Under general anesthesia, bipolar stimulating electrodes were attached proximal to the nerve injury site, and the compound muscle action potential and terminal latency were recorded by electrodes inserted into the gastrocnemius muscle [33].

Statistics

Multiple-group comparisons were made using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Tukey–Kramer test, and two-group comparisons were made using the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. All analyses were performed with the JMP software (SAS, Cary, NC, USA) with a pre-specified significance level of 95%. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

IL4-MΦ promotes axon regeneration after PNI

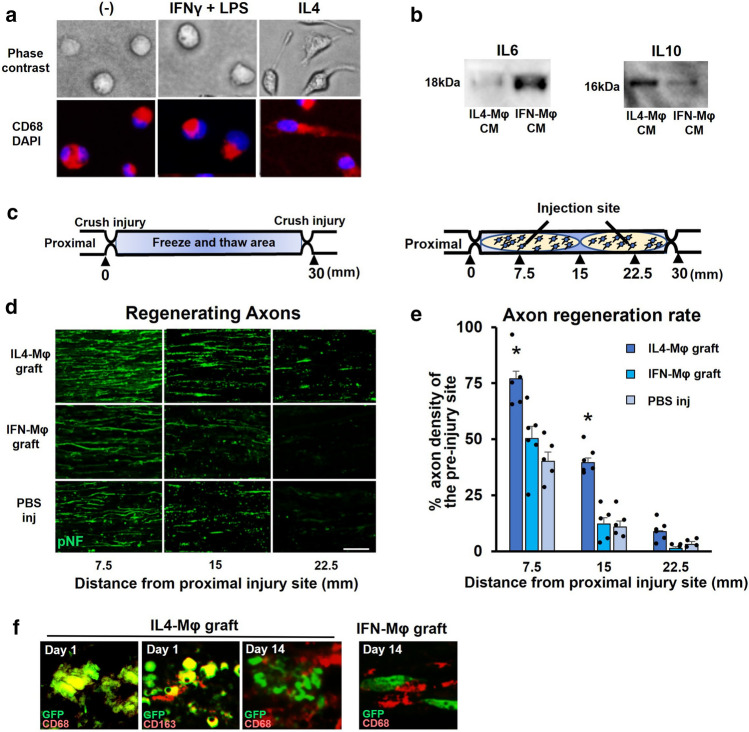

First, we aimed to determine whether IL4-MΦ had a direct axon regeneration effect in vivo. Syngeneic green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing macrophages were prepared from peritoneal macrophages of syngeneic GFP Lewis rats [19] and stimulated for 2 days with IL4 or IFNγ + LPS for generating M2 or M1 type macrophages respectively [9, 20]. Morphology of IL4-MΦ is different from IFNγ + LPS stimulated macrophages (IFN-MΦ) (Fig. 1a). Western blotting of their culture medium demonstrated that IL4-MΦ secreted IL10 but not IL6, whereas IFNγ-MΦ secreted IL6 but not IL10 (Fig. 1b). Then, these prepared macrophages were grafted into the sciatic nerve acellular model (Fig. 1c), which is an experimental model dedicated to the elucidation of the axon-promoting effects of the grafted cells [21]. Because, in this model, no live cells are present in the region of cell grafting (Fig. 1c), observed axon-promoting effect is likely due to a direct effect of grafted cells on axons rather than an indirect effect through neighboring cells. As a control, PBS injection was used. The graft of IL4-MΦ but not IFNγ-MΦ significantly promoted axon regeneration 2 weeks after injury, compared to the graft of IFNγ-MΦ and PBS injection (Fig. 1d). In subjects receiving the graft of IL4-MΦ, 77% and 40% of injured axons reached the points of 7.5 mm and 15 mm from the proximal injury site respectively, whereas only 50% and 12% of injured axons reached the points of 7.5 mm and 15 mm from the proximal injury site in subjects receiving the graft of IFNγ-MΦ (Fig. 1e). There was no significant difference in the extent of axon regeneration between the graft of IFNγ-MΦ and PBS injection. These results suggest that IL4-MΦ promotes axon regeneration by their direct effects on injured axons. When investigating the survival of grafted macrophages, both IFNγ-MΦ and IL4-MΦ did not survive for 2 weeks after grafting, as expected [34, 35], indicating that observed axonal growth was an immediate effect of grafted macrophages (Fig. 1f).

Fig. 1.

IL4-MΦ has the capacity to directly promote axon regeneration a Peritoneal macrophages were stimulated with IFNγ and LPS, or IL4 for 2 days to induce IFN-γMφ or IL-4Mφ, respectively. Phase-contrast images depicted that the morphology of IL-4Mφ differed from that of IFN-γMφ. All macrophages expressed CD68. Scale bar: 10 μm. b Western blotting of the CM. IL6 was detected in the CM of macrophages induced with IFNγ and LPS. IL10 was detected in the CM of macrophages induced with IL4. c Schema of the acellular model and the cell graft procedure. d Representative images of regenerating axons immunolabeled with pNF 2 weeks after the grafts. The IL-4Mφ graft showed more regenerating axons than the other two groups. Left is proximal. Scale bar: 50 μm. e Quantification of regenerating axons. Injection of the IL-4Mφ graft demonstrated statistically more regenerating axons than the other two groups. *P < 0.05 vs. the IFN-γMφ graft and PBS injection. One-way ANOVA with the Tukey–Kramer test was used. N = 5–6 per group. Individual dots indicate each subject. Error bars represent the SEM. f Double immunolabeled image of grafted macrophages. One day after the graft of IL-4Mφ, GFP expressing grafted cells showed CD68 and CD163 immunoreactivity, whereas none of grafted IFN-γMφ or IL-4Mφ expressed CD68 immunoreactivity 14 days after grafting. Scale bar: 10 μm

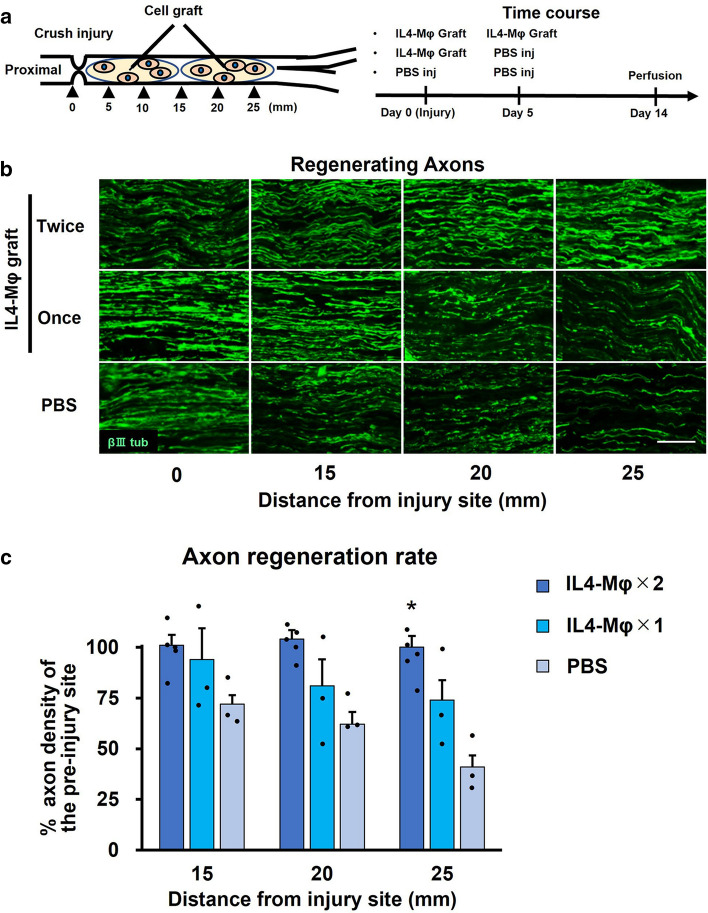

Next, to further confirm the axon regeneration effect of IL4-MΦ, we grafted IL4-MΦ into the region of WD after crush injury. Since its graft site consists of heterogenous cell populations including Schwann cells unlike the model in the preceding experiment, this graft experiment can investigate the consequence of the direct effect on axons as well as the indirect effect through other cells. Because this model is permissive enough for all axons to be able to regenerate to target organs eventually [36, 37], the axon regeneration effect of IL4-MΦ might be lost in this model. GFP-expressing syngeneic IL4-MΦ was grafted once or twice into the region of WD (Fig. 2a). PBS injection was performed as a control. Two weeks later, subjects receiving the twice graft of IL4-MΦ demonstrated the greatest axon regeneration among the three groups (Fig. 2b). The subjects receiving the twice graft of IL4-MΦ demonstrated 100% of injured axons reaching the 25 mm point distal to the injury site, whereas the subjects receiving the once graft of IL4-MΦ or PBS injection revealed 74% and 31% of injured axons regenerating at the 25 mm point distal to the injury site respectively (Fig. 2c). These findings indicate that IL4-MΦ increases the rate of axon regeneration after PNI.

Fig. 2.

IL-4Mφ graft increases the rate of axon regeneration after sciatic nerve crush injury a Left; experimental schema of the crush injury and the IL-4Mφ graft. Right; time course of the procedures. b Representative images of regenerating axons immunolabeled with βIIItubulin. Left is proximal. The twice graft of the IL-4Mφ promoted axon regeneration. Scale bar: 50 μm. c Quantification of regenerating axons. The twice graft of IL-4Mφ achieved significantly more regenerating axons than the control. Individual dots indicate each subject. N = 3–5 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS injection. One-way ANOVA with the Tukey–Kramer test was used for analysis. Error bars represent the SEM

uPA secreted from IL4-MΦ promotes neurite outgrowth by stimulating uPAR

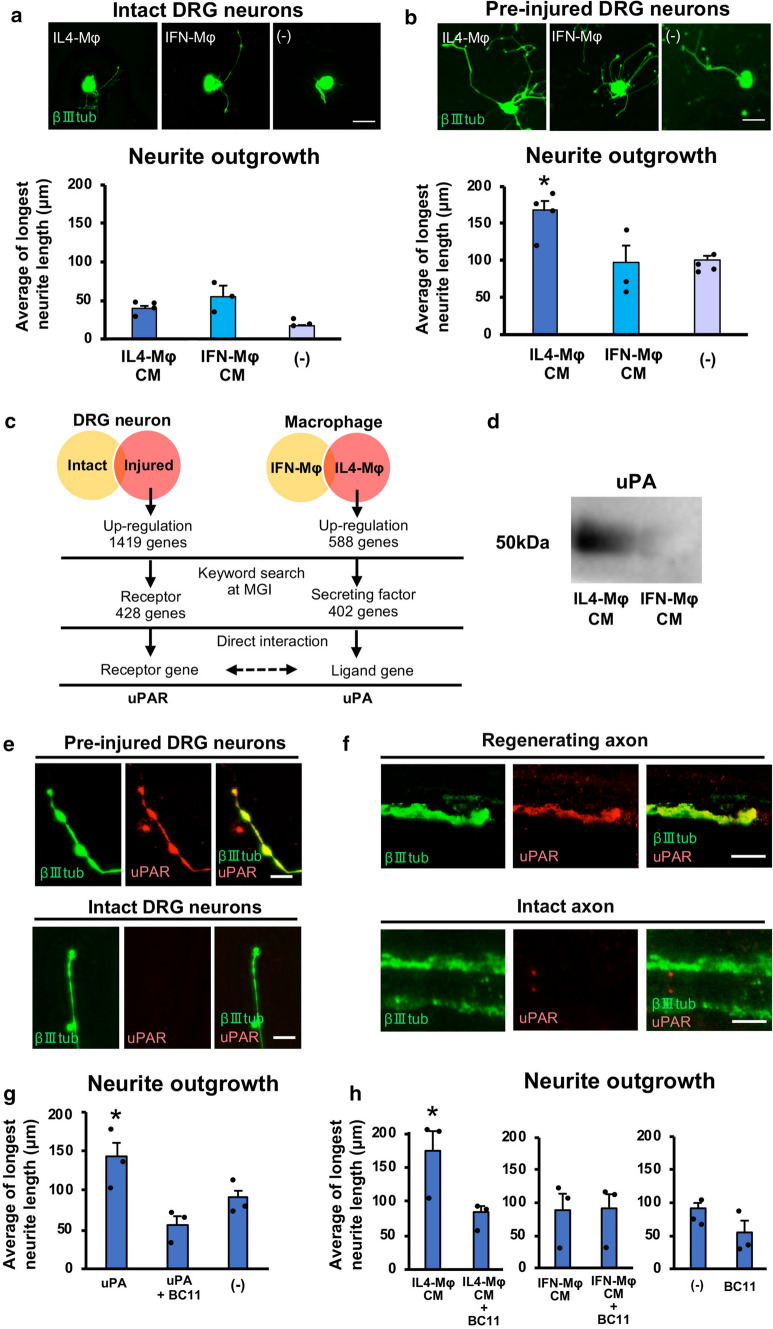

To elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying the effect of IL4-MΦ on axon regeneration, we examined the effect of conditioned medium (CM) from IL4-MΦ on neurite outgrowth of mature dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons. As a control, CM from IFNγ-MΦ or no addition of CM was tested. The average longest neurite length of DRG neurons was 39 μm, 55 μm, and 17 μm in neurons stimulated with CM derived from IL4-MΦ, IFNγ-MΦ, and no CM respectively. No statistical difference in the average of longest neurite length was detected between groups (Fig. 3a). CM derived from both IL4-MΦ and IFNγ-MΦ failed to stimulate neurite outgrowth significantly compared to control, raising a concern whether the experimental condition simulates the actual in vivo conditions. Because DRG neurons received axonal injuries prior to exposure to humoral factors from grafted IL4-MΦ in vivo, we next used pre-injured DRG neurons. Interestingly, the average longest neurite length of DRG neurons stimulated with IL4-MΦ derived CM was 167 μm, whereas that of DRG neurons stimulated with IFNγ derived CM and no CM were 98 μm and 101 μm, respectively (Fig. 3b). Namely, IL4-MΦ, but not IFNγ-MΦ derived CM, significantly elongated neurites of the injured DRG neurons compared to control. Therefore, we hypothesized that the humoral factors derived from IL4-MΦ stimulated receptors upregulated in injured DRG neurons.

Fig. 3.

uPA secreted from IL-4Mφ stimulates uPAR on injured neurons to promote neurite elongation a Neurite outgrowth of intact DRG neurons with IL-4Mφ derived CM (IL-4Mφ CM), IFN-γMφ CM, and no addition of CM. There was no significant difference in the average of the longest neurite length among the tested conditions. N = 3 wells per group. Error bars represent the SEM. Scale bar: 100 μm. b Neurite outgrowth of pre-injured DRG neurons under the same condition. Neurites stimulated with IL-4Mφ CM were significantly longer than in other conditions. N = 3 wells per group. Error bars represent the SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. IFN-γMφ CM and no CM. One-way ANOVA with the Tukey–Kramer test was used for analysis. Scale bar: 100 μm. c Flowchart to describe the steps used to identify candidate signaling underlying the effect of IL-4Mφ on injured DRG neurons. Gene expression data from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) for DRG neurons [38] and macrophages [39] were used. Genes upregulated only in the injured neurons and IL-4Mφ were screened, followed by narrowing down the gene list using the keywords, receptor, and secreting factor at the MGI. Then, a search for any direct interaction between two groups of genes led to the identification of uPA and uPAR. d Western blotting of uPA. uPA was detected in IL-4MφCM but not in IFN-γMφCM. e Representative images of double immunolabeling for βIIItubulin and uPAR on neurites of DRG neurons. Upper images are from pre-injured neuron and demonstrate a neurite expressing uPAR immunoreactivity. Lower images are from the intact neuron and show no uPAR immunoreactivity in neurite. At least 50 neurons per condition were examined. Scale bar: 10 μm. f Representative images of double immunolabeling for βIIItubulin and uPAR in the longitudinal sections of rat sciatic nerves. At the area of axon regeneration, which was at 5 mm from the injury site 3 days after injury, a regenerating axon expressed uPAR, whereas, on the intact nerve, no uPAR was detected. At least 50 neurons per condition were examined. Scale bar: 10 μm. g Pre-injured DRG neurons were stimulated with uPA with or without the uPA specific inhibitor, BC11. Quantification of neurite length demonstrated that uPA increased the average of the longest neurite length significantly and that BC11 abolished its effect. *P < 0.05 vs. uPA + BC11. N = 3 wells per group. Error bars represent the SEM. One-way ANOVA with the Tukey–Kramer test was used for analysis. h The blockade of uPA on IL4-MφCM was tested by the addition of BC11 to the culture media of pre-injured neurons. Quantification of neurite length revealed that treatment with BC11 significantly decreased the longest neurite length promoted by IL4-MφCM. BC11 did not affect the neurite length of pre-injured neurons, regardless of the presence or absence of IFNγ-MφCM. *P < 0.05 vs. M2CM + BC11. N = 3 wells per group. Error bars represent the SEM. Student’s t test was used for analysis

To explore this hypothesis, we mined RNA sequencing data of injured DRG neurons [38] and IL4-MΦ macrophages [39]. We screened the humoral factors upregulated only in IL4-MΦ and the receptors upregulated only in the injured DRGs, followed by a search for any direct ligand-receptor interactions between these two groups of molecules (Fig. 3c). Among more than 1450 molecules, we found one candidate signaling pathway, urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA)-uPA receptor (uPAR), which qualifies our criteria (Fig. 3c). In fact, uPA was present in the IL4-MΦ derived CM, but not in the IFNγ-MΦ derived CM (Fig. 3d). The elongating neurites from pre-injured DRG neurons expressed uPAR, whereas short neurites from intact DRG neurons did not (Fig. 3e). Moreover, regenerating but not intact axons expressed uPAR (Fig. 3f). These results indicate that IL4-MΦ secrete uPA, and injured axons upregulate the expression of its receptor, uPAR.

Next, we determined whether uPA-uPAR signaling is the central axis of the neurite-elongating effect of IL4-MΦ derived CM. When stimulating injured DRG neurons with uPA, neurite length was 57% increased from 91 to 143 μm, and the addition of BC11, an uPA specific inhibitor, abolished its effect completely (Fig. 3g). Furthermore, when inhibiting uPA contained in IL4-MΦ derived CM with BC11, its neurite elongation effect was completely abolished from 174 to 83 μm (Fig. 3h). Collectively, these results suggest that uPA-uPAR signaling is the molecular axis of axon regeneration induced by IL4-MΦ.

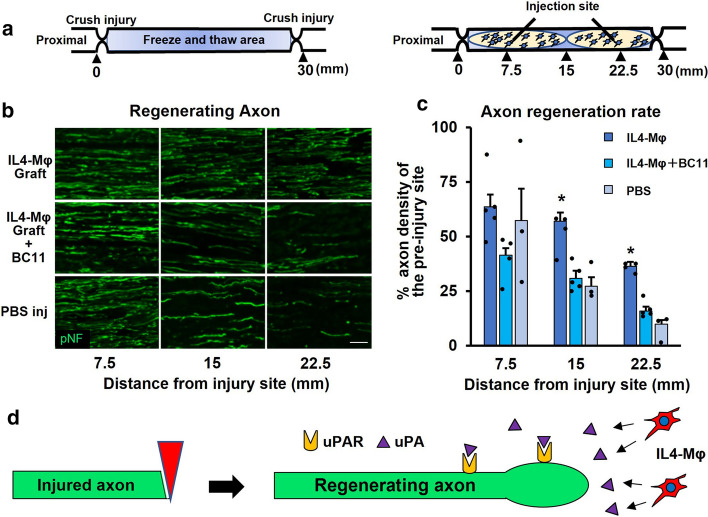

Inhibition of uPA abolishes axon regeneration effect of IL4-MΦ

To determine whether uPA is responsible for the axon regeneration effect of IL4-MΦ in vivo, BC11 was co-injected with IL4-MΦ into the sciatic nerve acellular region (Fig. 4a). As shown in the preceding experiment, the graft of IL4-MΦ demonstrated significantly greater axon regeneration than PBS injection. It was 110% and 163% more regenerating axons at 15 mm and 22.5 mm points from the proximal injury site than PBS injection. BC11 co-injection significantly decreased its axon regeneration effect from 110 to 0% and from 163 to 60% at 15 mm and 22.5 mm points from the proximal injury site respectively (Fig. 4b, c). This result indicates that uPA-uPAR signaling is the molecular axis of axon regeneration induced by IL4-MΦ. The molecular mechanism of IL4-MΦ on regenerating axons is summarized in Fig. 4d.

Fig. 4.

Blockade of uPA attenuates the axon regeneration effect of IL-4Mφ a Schema of the acellular model and the cell graft procedure. b Representative images of regenerating axons immunolabeled with βIIItubulin 2 weeks after grafting. The graft of IL-4Mφ with BC11 demonstrated reduced axon regeneration, compared to the graft of IL-4Mφ alone. Left is proximal. Scale bar: 50 μm. c Quantification of regenerating axons. The graft of IL-4Mφ revealed statistically more axon regeneration than no cell graft, whereas the graft of IL-4Mφ with BC11 demonstrated no significant difference in axon regeneration than no cell graft. Individual dots indicate each subject. N = 3–5 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS. One-way ANOVA with the Tukey–Kramer test was used for analysis. Error bars represent SEM. d Schema of the uPA-uPAR axis in the activity of IL-4Mφ on axon regeneration

IL4-MΦ graft promotes functional recovery after PNI

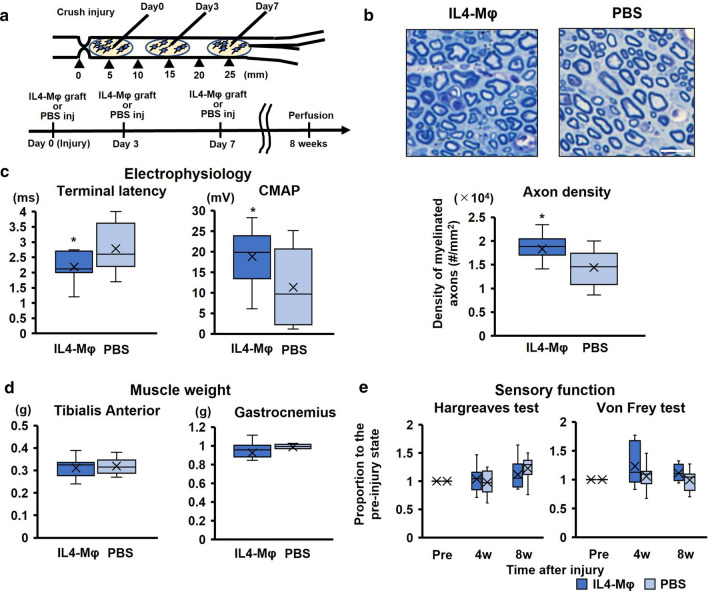

To elucidate the therapeutic potential of IL4-MΦ, we determined whether the graft of syngeneic IL4-MΦ promoted functional recovery after PNI using the crush injury model. Because all axons regenerate and functional deficits disappear eventually in crush injury model [36, 37], the usage of this model investigates therapeutic effects on the rate of axon regeneration rather than the number of regenerating axons. Adult Lewis rats received crush injuries in the ipsilateral sciatic nerves, followed by application of the graft of IL4-MΦ at the same time of injury, 3 days, and 7 days after injury (Fig. 5a). Control rats received PBS injections in the same manner. Every four weeks after injury, the rats underwent functional tests, followed by perfusion at 8 weeks after injury. The rats receiving the graft of IL4-MΦ revealed significantly more myelinated axons at the distal end of the sciatic nerve than the control rats (Fig. 5b). Average density of myelinated axons in subjects treated with the graft of IL4-MΦ was 27% more than that of control subjects, further supporting the fact that IL4-MΦ promotes axon regeneration. Electrophysiological evaluation of the sciatic nerves demonstrated that the amplitude of the gastrocnemius muscle in the subjects treated with the graft of IL4-MΦ was 66% greater than those in the control subjects. The terminal latency was 27% shorter in the treated subject than the control subjects (Fig. 5c), indicating better motor recovery by application of the IL4-MΦ graft. The gait analysis showed no apparent difference in most of the gait parameters between the two groups except for two parameters, the paw drag and the swing duration (Suppl. Fig. 1), which were improved by the application of the IL4-MΦ graft. Likewise, there was no difference in the weights of leg muscles and sensory functions between the two groups (Fig. 5d, e). These results indicate that the graft of IL4-MΦ promotes functional recovery after PNI by accelerating the rate of axon regeneration.

Fig. 5.

The graft of IL-4Mφ promotes functional recovery after PNI a Upper; schema of the crush injury and the IL-4Mφ graft. Lower; time course of the procedures. N = 10 per group. b Upper; toluidine blue-stained axial images of the distal end of sciatic nerves. The IL-4Mφ graft induced more myelinating axons. Scale bar: 10 μm. Lower; quantification of the density of myelinated axons. The rats with the IL-4Mφ graft showed statistically more myelinating axons than control rats. N = 10 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS injection. Student’s t test was used for analysis. Box and Whisker Plot. c Electrophysiological functions recorded at the gastrocnemius muscle when stimulating sciatic nerve proximal to the injury site. The rats with the IL-4Mφ graft revealed significantly shorter terminal latency and greater compound muscle action potential (CMAP) than the control rats. N = 10 per group. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS injection. Student’s t test was used. Box and Whisker Plot. d Weight of the tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles. There was no statistical difference between the two groups as assessed using the Student’s t test. N = 10 per group. Box and Whisker Plot. e Sensory functions evaluated by the Hargreaves and von Frey test. There was no statistical difference detected between the two groups at 4 and 8 weeks after the injury as evaluated using the Student’s t test. N = 10 per group. Box and Whisker Plot

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that IL4-MΦ could promote axon regeneration and improve functional recovery after PNI by secreting uPA to stimulate uPAR in injured axons, providing the evidence of the therapeutic potential of IL4-MΦ and its precise molecular mechanism. Although it is not clear that IL4-MΦ mimics a certain type of macrophages existing in the spontaneous repair process after PNI, the current finding indicates the possibility that M2-like macrophages could be involved with axon regeneration after PNI.

Despite the fact that it was reported that M2 macrophages contributed to the regenerative process in the nervous system more than a decade ago [16, 17], the definite factor responsible for their therapeutic effect remains to be identified. The general knockout of IL10, a typical humoral factor secreted by M2 macrophages, impairs axon regeneration [40], however, whether IL10 promotes axonal regeneration remains unclear. The reason why no definite factor has been identified so far is that only intact neurons were tested in the in vitro experiments in the studies. In the present study, to simulate the in vivo situation, pre-injured neurons were tested, allowing us to detect the effect of CM on neurite outgrowth. This indicates the importance of the use of pre-injured neurons in vitro for axon regeneration research.

In the current study, uPA-uPAR was identified as a molecular mechanism underlying the axon-promoting effect of IL4-MΦ. uPA-uPAR has been reported to be involved in axonal development and regeneration in the CNS as well as the PNS, mainly by plasminogen activator-mediated extracellular proteolytic cascades [41, 42]. Recently, it has also been demonstrated that uPA initiates intracellular signaling via direct interaction with uPAR in CNS and PNS injury model [43–46]. However, most of the previous studies have focused on the acute injury site where uPA is abundant from heterogeneous cell populations accumulating at the injury site but not the region of WD where axons need to grow for a long distance. Although the current study did not elucidate the role of uPA in the region of WD, it gives a clue about how uPA secreting cells could affect the repair process in the region of WD and how artificially differentiated macrophages can exert the regenerative effects in the region of WD.

Because uPAR does not have transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains, to initiate intracellular signals, uPAR needs co-receptors, such as the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP1), integrins, and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [47, 48]. For example, the binding of uPA to uPAR of embryonic cortical neurons induces LRP1-mediated membrane recruitment of activated integrin β1, which leads to activation of the Rho family small GTPase Rac1, resulting in enhanced neurite outgrowth [43]. In the case of neuroblastoma cells, stimulated uPAR activates ERK1/2 signaling via EGFR and enhanced neuritogenesis [49]. Because activation of Rac1 and ERK1/2 promotes neurite outgrowth of adult DRG neurons [50, 51], it is likely that uPAR stimulated axon regeneration observed in the present study is mediated by activation of Rac1 or ERK1/2. Further study needs to clarify the actual cell signaling in adult DRG neurons when stimulated with uPA.

Aging is one of the factors to affect the therapeutic effect of IL4-MΦ. Previous studies reveal that the capability of spontaneous axon regeneration after PNI diminishes in aged rodents, and it could be due to the reduced function of Schwann cells [52]. Therefore, even though IL4-MΦ secretes a sufficient amount of uPA in an aged subject, axons may not be able to respond to it due to the lack of sufficient support from Schwann cells. In addition, macrophages seem to be more pro-inflammatory with aging [53]. Therefore, aging might reduce the amount of uPA secreted from IL4-MΦ or decrease the efficiency of induction of the IL4-MΦ.

Generally, motor function is more susceptible to impairment than sensory function after PNI, especially in the case of proximal injury [54]. This is because the denervated muscle loses its sensitivity for reinnervation if regenerating axons reach the muscle after the critical period, whereas sensory organs do not have such a critical period for reinnervation [55] 54. Therefore, it is desirable to develop a strategy to accelerate the speed of axon regeneration. Because, in a crush injury model, all injured axons eventually regenerate [36, 37], the current result showing the promotion of axon regeneration after crush injury indicates that the IL4-MΦ graft accelerated the speed of axon regeneration rather than its amount. Thus, IL4-MΦ graft could be an effective therapeutic approach for crush injuries, as well as injuries requiring surgical reconstruction or sutures.

Even though the graft of IL4-MΦ is attractive as a cell therapy for PNI, autograft might not be the best for clinical translation. From the practical point of view, it is desirable to perform the graft of IL4-MΦ at the same time as reconstruction or suture surgery, which is usually at the acute stage of injury. However, it takes a while to prepare a sufficient number of patient-derived IL4-MΦ. Therefore, future studies need to investigate the effect of allo-graft of IL4-MΦ, explore alternative methods to generate IL4-MΦ in vivo, or evaluate the effect of uPA administration. Importantly, the duration of uPAR upregulated in injured axons needs to be clarified to determine the period in which injured axons have sensitivity to IL4-MΦ therapy.

Conclusion

Typical M2 macrophages, IL4-MΦ, has the capacity to promote axon regeneration by its direct effect on axons, and the graft of IL4-MΦ into the region of WD improves functional recovery after PNI. Importantly, L4-MΦ secretes uPA to stimulate uPAR upregulated in injured axons, resulting in the promotion of axon regeneration. These findings unveil the cellular and molecular mechanism underlying macrophage-related axon regeneration and provide a basis for a novel therapy for PNI.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Suppl. Fig. 1: Gait analysis of the graft of IL-4Mφ after PNI The gait analysis was performed at pre-injury, and at 4 and 8 weeks after the crush injuries using DigiGait. No statistical difference was detected between the rats injected with the IL-4Mφ graft and the control rats in most of the gait parameters except paw drag and swing duration at 8 weeks after injury. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS injection. Student’s t test was used for analysis. N = 10 per group. Error bars represent SEM. (JPG 150 KB)

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Endo for their assistance with immunohistochemistry. We are thankful to the National BioResource Project-Rat for providing LEWTg (CAG-EGFP) rats, the Genome Information Research Center for providing Sprague Dawley-Tg (CAG-EGFP) rats, and the Open Facility, Hokkaido University Sousei Hall for access to the cryostat.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: YM and KK. Methodology: YM, KK and AT. Investigation: YM, KK, YN, MH, GM, TS, YY and AT. Funding acquisition: KK and NI. Project administration: KK and NI. Supervision: KK and NI. Writing—original draft: YM and KK.

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (17K11527), the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (JP20gm6210004), the General Insurance Association of Japan (2017–2020), the Kobayashi Foundation, and the SEI Group CSR Foundation.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

All experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the local ethical committee of the Hokkaido University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Campana L, Esser H, Huch M, Forbes S. Liver regeneration and inflammation: from fundamental science to clinical applications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang S, Bories G, Lantz C, Emmons R, Becker A, Liu E, et al. Immunometabolism of phagocytes and relationships to cardiac repair. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:42. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2019.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parimon T, Hohmann MS, Yao C. Cellular senescence: pathogenic mechanisms in lung fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(12):6214. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zigmond RE, Echevarria FD. Macrophage biology in the peripheral nervous system after injury. Prog Neurobiol. 2019;173:102–121. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mesquida-Veny F, Del Rio JA, Hervera A. Macrophagic and microglial complexity after neuronal injury. Prog Neurobiol. 2021;200:101970. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2020.101970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perrin FE, Lacroix S, Aviles-Trigueros M, David S. Involvement of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha and interleukin-1beta in Wallerian degeneration. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 4):854–866. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niemi JP, DeFrancesco-Lisowitz A, Roldan-Hernandez L, Lindborg JA, Mandell D, Zigmond RE. A critical role for macrophages near axotomized neuronal cell bodies in stimulating nerve regeneration. J Neurosci. 2013;33(41):16236–16248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3319-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez FO, Gordon S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6(13):787–795. doi: 10.12703/P6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(3):787–795. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41(1):14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivashkiv LB. Epigenetic regulation of macrophage polarization and function. Trends Immunol. 2013;34(5):216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krzyszczyk P, Schloss R, Palmer A, Berthiaume F. The role of macrophages in acute and chronic wound healing and interventions to promote pro-wound healing phenotypes. Front Physiol. 2018;9:419. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ydens E, Amann L, Asselbergh B, Scott CL, Martens L, Sichien D, et al. Profiling peripheral nerve macrophages reveals two macrophage subsets with distinct localization, transcriptome and response to injury. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23(5):676–689. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0618-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gay D, Ghinatti G, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Ferrer RA, Ferri F, Lim CH, et al. Phagocytosis of Wnt inhibitor SFRP4 by late wound macrophages drives chronic Wnt activity for fibrotic skin healing. Sci Adv. 2020;6(12):eaay3704. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aay3704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gensel JC, Nakamura S, Guan Z, van Rooijen N, Ankeny DP, Popovich PG. Macrophages promote axon regeneration with concurrent neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2009;29(12):3956–3968. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3992-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kigerl KA, Gensel JC, Ankeny DP, Alexander JK, Donnelly DJ, Popovich PG. Identification of two distinct macrophage subsets with divergent effects causing either neurotoxicity or regeneration in the injured mouse spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2009;29(43):13435–13444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mokarram N, Merchant A, Mukhatyar V, Patel G, Bellamkonda RV. Effect of modulating macrophage phenotype on peripheral nerve repair. Biomaterials. 2012;33(34):8793–8801. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartus K, James ND, Didangelos A, Bosch KD, Verhaagen J, Yanez-Munoz RJ, et al. Large-scale chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan digestion with chondroitinase gene therapy leads to reduced pathology and modulates macrophage phenotype following spinal cord contusion injury. J Neurosci. 2014;34(14):4822–4836. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4369-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiménez-García L, Herránz S, Luque A, Hortelano S. Thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages preparation and arginase activity measurement in IL-4 stimulated macrophages. Bio-protocol. 2015 doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.1585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stein M, Keshav S, Harris N, Gordon S. Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: a marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J Exp Med. 1992;176(1):287–292. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Endo T, Kadoya K, Suzuki Y, Kawamura D, Iwasaki N. A novel experimental model to determine the axon-promoting effects of grafted cells after peripheral nerve injury. Front Cell Neurosci. 2019 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2019.00280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadoya K, Tsukada S, Lu P, Coppola G, Geschwind D, Filbin MT, et al. Combined intrinsic and extrinsic neuronal mechanisms facilitate bridging axonal regeneration one year after spinal cord injury. Neuron. 2009;64(2):165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meijering E, Jacob M, Sarria JC, Steiner P, Hirling H, Unser M. Design and validation of a tool for neurite tracing and analysis in fluorescence microscopy images. Cytometry A. 2004;58(2):167–176. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Endo T, Kadoya K, Kawamura D, Iwasaki N. Evidence for cell-contact factor involvement in neurite outgrowth of DRG neurons stimulated by Schwann cells. Exp Physiol. 2019 doi: 10.1113/EP087634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akula SK, McCullough KB, Weichselbaum C, Dougherty JD, Maloney SE. The trajectory of gait development in mice. Brain Behav. 2020;10(6):e01636. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirose K, Iwakura N, Orita S, Yamashita M, Inoue G, Yamauchi K, et al. Evaluation of behavior and neuropeptide markers of pain in a simple, sciatic nerve-pinch pain model in rats. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(10):1746–1752. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1428-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32(1):77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nirogi R, Goura V, Shanmuganathan D, Jayarajan P, Abraham R. Comparison of manual and automated filaments for evaluation of neuropathic pain behavior in rats. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2012;66(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deuis JR, Dvorakova LS, Vetter I. Methods used to evaluate pain behaviors in rodents. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:284. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson KD, Gunawan A, Steward O. Quantitative assessment of forelimb motor function after cervical spinal cord injury in rats: relationship to the corticospinal tract. Exp Neurol. 2005;194(1):161–174. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banik RK, Kabadi RA. A modified Hargreaves' method for assessing threshold temperatures for heat nociception. J Neurosci Methods. 2013;219(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sayanagi J, Tanaka H, Ebara M, Okada K, Oka K, Murase T, et al. Combination of electrospun nanofiber sheet incorporating methylcobalamin and PGA-collagen tube for treatment of a sciatic nerve defect in a rat model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102(3):245–253. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.00254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paul CD, Devine A, Bishop K, Xu Q, Wulftange WJ, Burr H, et al. Human macrophages survive and adopt activated genotypes in living zebrafish. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1759. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-38186-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roszer T. Understanding the biology of self-renewing macrophages. Cells. 2018;7(8):103. doi: 10.3390/cells7080103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bridge PM, Ball DJ, Mackinnon SE, Nakao Y, Brandt K, Hunter DA, et al. Nerve crush injuries—a model for axonotmesis. Exp Neurol. 1994;127(2):284–290. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen LE, Seaber AV, Glisson RR, Davies H, Murrell GA, Anthony DC, et al. The functional recovery of peripheral nerves following defined acute crush injuries. J Orthop Res. 1992;10(5):657–664. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100100508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perkins JR, Antunes-Martins A, Calvo M, Grist J, Rust W, Schmid R, et al. A comparison of RNA-seq and exon arrays for whole genome transcription profiling of the L5 spinal nerve transection model of neuropathic pain in the rat. Mol Pain. 2014;10:7. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerrick KY, Gerrick ER, Gupta A, Wheelan SJ, Yegnasubramanian S, Jaffee EM. Transcriptional profiling identifies novel regulators of macrophage polarization. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siqueira Mietto B, Kroner A, Girolami EI, Santos-Nogueira E, Zhang J, David S. Role of IL-10 in resolution of inflammation and functional recovery after peripheral nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2015;35(50):16431–16442. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2119-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siconolfi LB, Seeds NW. Induction of the plasminogen activator system accompanies peripheral nerve regeneration after sciatic nerve crush. J Neurosci. 2001;21(12):4336–4347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04336.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siconolfi LB, Seeds NW. Mice lacking tPA, uPA, or plasminogen genes showed delayed functional recovery after sciatic nerve crush. J Neurosci. 2001;21(12):4348–4355. doi: 10.1523/Jneurosci.21-12-04348.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merino P, Diaz A, Jeanneret V, Wu F, Torre E, Cheng L, et al. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) binding to the uPA receptor (uPAR) promotes axonal regeneration in the central nervous system. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(7):2741–2753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.761650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lino N, Fiore L, Rapacioli M, Teruel L, Flores V, Scicolone G, et al. uPA-uPAR molecular complex is involved in cell signaling during neuronal migration and neuritogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2014;243(5):676–689. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merino P, Yepes M. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator induces neurorepair in the ischemic brain. J Neurol Exp Neurosci. 2018;4(2):24–29. doi: 10.17756/jnen.2018-039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Klimovich PS, Semina EV, Karagyaur MN, Rysenkova KD, Sysoeva VY, Mironov NA, et al. Urokinase receptor regulates nerve regeneration through its interaction with alpha5beta1-integrin. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;125:110008. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith HW, Marshall CJ. Regulation of cell signalling by uPAR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(1):23–36. doi: 10.1038/nrm2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Landowski LM, Pavez M, Brown LS, Gasperini R, Taylor BV, West AK, et al. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins in a novel mechanism of axon guidance and peripheral nerve regeneration. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(3):1092–1102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.668996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rysenkova KD, Klimovich PS, Shmakova AA, Karagyaur MN, Ivanova KA, Aleksandrushkina NA, et al. Urokinase receptor deficiency results in EGFR-mediated failure to transmit signals for cell survival and neurite formation in mouse neuroblastoma cells. Cell Signal. 2020;75:109741. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saleh A, Smith DR, Tessler L, Mateo AR, Martens C, Schartner E, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE) activates divergent signaling pathways to augment neurite outgrowth of adult sensory neurons. Exp Neurol. 2013;249:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanabe K, Bonilla I, Winkles JA, Strittmatter SM. Fibroblast growth factor-inducible-14 is induced in axotomized neurons and promotes neurite outgrowth. J Neurosci. 2003;23(29):9675–9686. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09675.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Painter MW, Brosius Lutz A, Cheng YC, Latremoliere A, Duong K, Miller CM, et al. Diminished Schwann cell repair responses underlie age-associated impaired axonal regeneration. Neuron. 2014;83(2):331–343. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Beek AA, Van den Bossche J, Mastroberardino PG, de Winther MPJ, Leenen PJM. Metabolic alterations in aging macrophages: ingredients for inflammaging? Trends Immunol. 2019;40(2):113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma CH, Omura T, Cobos EJ, Latremoliere A, Ghasemlou N, Brenner GJ, et al. Accelerating axonal growth promotes motor recovery after peripheral nerve injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(11):4332–4347. doi: 10.1172/JCI58675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sakuma M, Gorski G, Sheu SH, Lee S, Barrett LB, Singh B, et al. Lack of motor recovery after prolonged denervation of the neuromuscular junction is not due to regenerative failure. Eur J Neurosci. 2016;43(3):451–462. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Suppl. Fig. 1: Gait analysis of the graft of IL-4Mφ after PNI The gait analysis was performed at pre-injury, and at 4 and 8 weeks after the crush injuries using DigiGait. No statistical difference was detected between the rats injected with the IL-4Mφ graft and the control rats in most of the gait parameters except paw drag and swing duration at 8 weeks after injury. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS injection. Student’s t test was used for analysis. N = 10 per group. Error bars represent SEM. (JPG 150 KB)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.