Abstract

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) technology has been widely applied to cell regeneration and disease modeling. However, most mechanism of somatic reprogramming is studied on mouse system, which is not always generic in human. Consequently, the generation of human iPSCs remains inefficient. Here, we map the chromatin accessibility dynamics during the induction of human iPSCs from urine cells. Comparing to the mouse system, we found that the closing of somatic loci is much slower in human. Moreover, a conserved AP-1 motif is highly enriched among the closed loci. The introduction of AP-1 repressor, JDP2, enhances human reprogramming and facilitates the reactivation of pluripotent genes. However, ESRRB, KDM2B and SALL4, several known pluripotent factors promoting mouse somatic reprogramming fail to enhance human iPSC generation. Mechanistically, we reveal that JDP2 promotes the closing of somatic loci enriching AP-1 motifs to enhance human reprogramming. Furthermore, JDP2 can rescue reprogramming deficiency without MYC or KLF4. These results indicate AP-1 activity is a major barrier to prevent chromatin remodeling during somatic cell reprogramming.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-021-03883-x.

Keywords: AP-1, Chromatin remodeling, Human induced pluripotent stem cells, JDP2

Introduction

Somatic cells can be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) by defined factors [1–3]. The generation of iPSCs is quite inefficient and a lot of efforts have been applied on the optimization of the induction methods. As reprogramming factors were screened from 24 factors, known as a part of pluripotency transcriptional regulatory network [1], other pluripotent factors including Nanog, Esrrb, and Nr5a2 were first considered as enhancers of reprogramming [3–6]. Furthermore, chemicals and various cell types were screened to improve reprogramming [7, 8]. As extracellular environment is important for cell fate transition, optimization of culture medium greatly improves the reprogramming efficiency [9, 10]. With the progress of mechanistic study, more promoting factors and chemicals were discovered. For instance, mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) is found as an essential early step for reprogramming [11, 12]. Accordingly, TGFβ inhibitors and Smad6 were characterized to promote reprogramming [11].

Currently, the efficiency of mouse iPSC generation from fibroblasts is around 10% [10], while the efficiency is much lower in human with the same cocktail factors. Most mechanistic studies were performed in the mouse system due to its advantage in genetic manipulation and large scale reprogramming cells preparation [13, 14]. In contrast, human reprogramming system is still inefficient. In the last decades, even though many studies identified hallmarks of sequentially activated/silenced genes and phase-specific regulators in the mouse reprogramming system [15–21], the molecular mechanisms of human reprogramming still largely unknown. Takahashi K et al. found that FOXH1 can enhance the reprogramming efficiency of human fibroblasts by promoting mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition and the activation of late pluripotency [22]. Liu et al. found KLF4 is sufficient for the conversion of primed hPSCs into naive t2iLGöY hPSCs [23]. Recently, Liu et al. provided a high-resolution roadmap of human somatic cells and identified the essential role of trophectoderm-lineage-specific regulatory program during reprogramming [24]. Thus, investigating the molecular mechanisms of human reprogramming will promote the reprogramming efficiency from available and noninvasive human cells.

A commonly negligible aspect is that there are distinct mechanisms between mouse and human somatic reprogramming. For example, ‘primed’ pluripotent states derived from iPSC requires additional reprogramming factors than naïve pluripotency [25–28]. On the other hand, the mouse reprogramming was known to initiate MET before the reactivation of pluripotency genes [11, 12, 29–32], a critical early stage hallmark event. Nevertheless, in humans, MET occurs at a much later stage of reprogramming, concomitantly with NANOG, LIN28A, and other core activators of pluripotency genes [33]. In many studies, chemicals are screened for enhancing reprogramming or replacing factors [7, 34]. However, mouse somatic reprogramming efficiency cannot be induced except for chemicals [35], but there is no evidence that chemicals can work similarly in human system yet. In addition to the coding genes, long non-coding RNAs also sequentially expressed and contribute to the induction of pluripotency. LINC-ROR, a primate-specific transposable element-derived lncRNA, modulates the efficiency of reprogramming by directly target key pluripotency transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG [36]. Human L1TD1 is a lncRNA that required for human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) self-renewal, through interacting with pluripotency factors and RNA-binding protein LIN28A to modulate the pluripotency master regulator, OCT4 [37, 38]. Meanwhile, L1TD1 is dispensable for the maintenance and induction of pluripotency in mouse [39]. Besides, specie-specific transposable elements (TEs) are reactivated and trigger pluripotency induction during reprogramming. HERVH, a primate-specific TE, establishes novel transcriptional circuitry regulating pluripotency and is required for reprogramming [40, 41]. Thus, part of the reprogramming processes is shared between mice and human, while some are unique. Dissecting the mechanism of human somatic reprogramming is important for understanding conserved mechanism and specie-specific mechanism, both of which would reveal the principle of cell fate determination and benefit iPSC technology. In this study, we found a conserved mechanism between human and mouse reprogramming. Surveying the chromatin accessibility dynamics, we revealed that the closing of AP-1 motif enriching somatic accessible loci serves as important barrier for human reprogramming. Further, AP-1 repressor JDP2 can significantly enhance human reprogramming in human urine-derived cells (UCs).

Materials and methods

Collection and expansion of UCs

We collected a total of 100–200 ml of urine from each donor. UCs were collected and cultured as described previously [42]. The primary UCs were cultured and passaged in the medium consisting of REGM™ (Renal Epithelial Cell Growth Medium) BulletKit™ (CC-3190, Lonza)/DMEM/high glucose (Hyclone) containing 100 × MEM NEAA (Gibco), 100 × glutaMAX-1 (Gibco), and 10%FBS (NTC) 1:1 (the combination of this referred to as RM). The cells were passaged less than 3 times were used for human iPSC cell generation.

iPSC generation

UCs at early passages were isolated by trypsin treatment (0.25% trypsin/0.5 mM EDTA, Gibco) and 3–5 × 104 cells were seeded onto a 12-well dish and the next day infected with retroviral stocks generated with 293T transfected with packaging plasmids pCL, pMX-based vectors that encode human factors OKSM (Adgene) [42] and JDP2. For reprogramming with lentivirus vector plasmids, the full-length coding sequences of JDP2 were cloned into the pRlenti–puro and pW-TRE-EGFP-Flag expression vector, psPAX2 and pMD2.G purchased from Adgene (12260 and 12259). The induced medium during reprogramming and proliferation named E7 consisted just of insulin, transferrin, selenium (INSULIN-TRANS-SEL-G, 100X, 41400045, Invitrogen), L-ascorbic acid (49752, Sigma), FGF2 (100-18B, PeproTech), and in DMEM/F12 as described previously [43, 44], and with Osmolarity pressure (OSM) approximately 340 mmol/l adjusted with 9%NaCl (S5886, Sigma). When cells transduced 24 h, treatment with RM 24 h, changed to E7 + 250 μM NaB (S1999, Selleck) with marked D0, and then changed to E7 at day 6. When colonies appeared, the medium was changed to mTeSR1 (85850, Stem Cell). Each medium was changed every other day. The iPSC colonies were picked at around days 12–15 and cultured in mTeSR1 on Matrigel (354277, Becton Dickinson) or in hESC medium consisted of 20% KSR (10828028, Gibco), 1 mM non-essential amino acids (GIBCO), 1X GlutaMAX (GIBCO), 0.1 mM 2-Mercaptoethanol (GIBCO) and 10 µg/ml FGF2 on feeder. The culture medium was changed daily. The iPSCs were passaged with 0.5 mM EDTA (E6511, sigma). To quantify the number of iPSC colonies, we used NBT and BCIP (C3206, Beyotime) for AP staining and performed TRA-1–60 immunostaining of reprogramming as described [45, 46]. In brief, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated with TRA-1–60 (eBioscience, #13–8863-82, 1:250) and streptavidin horseradish peroxidase (Biolegend, #405210, 1:500) diluted in PBS (3%), FCS (0.3%) Triton X-100. Staining was developed with the DAB peroxidase substrate Kit (Vector labs, #SK-4100) and iPSC colonies were scanned with HP Scanning (HP Scanjet G4050).

iPSC characterization

qRT-PCR was performed to analyze the expression endogenous genes and silence of exogenous reprogramming factors. Immunofluorescence microscopy (OCT-3/4 Antibody, Santa sc-5279; Human Nanog Antibody, Cell Signaling technology # 4903) and karyotyping were performed as described [42, 47]. The primers used for qRT-PCR was used according to a previous report [48]. qPCR was performed in triplicate with a CFX96 machine (Bio-Rad) and AceQ® Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Q511-02, Vazyme) following the instructions by the manufacturer. For teratoma formation, human iPSCs grown on Matrigel in mTeSR1 were collected with EDTA treatment, then 100,0000–200,0000 human iPSCs resuspended by Matrigel and injected into hindlimb muscles of 6-week-old NOD/SCID mice[49]. After 6–8 weeks, teratomas were obtained from all injections. The teratomas were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Beyotime). Samples were embedded in paraffin and processed with H&E staining in the Experimental Pathology Department of GIBH.

RNA-seq

RNA-seq was processed as described in [50]. Briefly, total mRNA was isolated from hUCs, the cells of reprogrammed on day 0, 1, 3, 6, 9, 12 and ESCs. RNA-seq libraries were constructed using the VAHTS™ mRNA-seq v2 Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NR601, Vazyme) following the instructions by the manufacturer. Libraries were sequenced using NextSeq 500 High Output Kit v2 (75 cycles) (FC-404–1005, Illumina). Briefly, sequenced reads were aligned to the GENCODE human annotations transcriptome (v25) using Bowtie2 (version 2.2.5) [51] and RSEM (version 2.4.1) [52]. Differentially expressed genes were obtained using DESeq2 (version 1.10.1) [53] with q-value < 0.05 and fold change > 2 as the threshold. Gene ontology analysis was performed using goseq (version 1.22.0) [54].

ATAC-Seq

ATAC-seq was performed as previously described [55]. Briefly, a total of 50,000 cells were washed once with 50 μl of cold PBS and resuspended in 50 μl lysis buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.2% (v/v) IGEPAL CA-630). The suspension of nuclei was then centrifuged for 10 min at 500 g at 4 ℃, and then 50 μl transposition reaction mix (10 μl 5 × TTBL, 5 μl TTE Mix V50 and 35 μl nuclease-free H2O) of TruePrep™ DNA Library Prep Kit V2 for Illumina® (TD501, Vazyme) was added. Samples were incubated at 37 ℃ for 30 min for PCR amplified. DNA was isolated using a MinElute® PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN). ATAC-seq libraries were constructed using the TruePrep™ DNA Library Prep Kit V2 for Illumina® (TD501, Vazyme) and the library was then PCR amplified for the appropriate number of cycles. Libraries were purified with a MinElute® PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN). Library concentration was measured using VAHTS Library Quantification Kit for Illumina (NQ102, Vazyme). Finally, the ATAC library was sequenced on a NextSeq 500 using a NextSeq 500 High Output Kit v2 (150 cycles) (FC-404–2002, Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All the sequencing data were aligned to the human genome assembly (hg38) using the Bowtie2 (version 2.2.5) with the options: -p 20 --very-sensitive --end-to-end --no-unal. Reads mapping to mitochondrial DNA or unassigned sequences were discarded. For pair-end sequence data, only concordantly aligned pairs were kept. Alignment bam files were transformed into read coverage files (bigwig format) using deepTools [56] with the RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads) normalization method. Biological replicates were merged and peaks were called using MACS2 [57] with default options. Motif analysis was performed using HOMER (v4.10) [58] with “-p 4 -size given” options. Other analysis was performed using glbase [59] and custom code.

CUT&Tag

CUT&Tag was performed as previously described [60–62] and used the Hyperactive™ In-Situ ChIP Library Prep Kit for Illumina kit (Vazyme Biotech, TD901). Briefly, a total of 50,000 cells were harvested, washed twice by Wash buffer and centrifuged for 3 min at 600 × g at room temperature. 10 μl of activated Con A beads were added to per sample and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Supernatant was removed and bead-bound cells were resuspended in 50 μl Dig-wash Buffer with 1 μg the appropriate primary antibody (Flag Antibody, Sigma F1804; KLF4 Antibody, Santa Cruz sc-20691; IgG mouse, Abcam ab18413; IgG rabbit, Cell Signaling Technology #3900S) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Then removed the primary antibody, added 50 μl dig-wash buffer with 0.5 μg secondary antibody and cultured at room temperature for 1 h. After washing twice with 800 μl dig-wash buffer, 0.58 μl pG–Tn5 was added with 100 μl dig-300 buffer and incubated at room temperature for 1 h, then washed twice with 800 μl dig-wash buffer. 300 μl tagmentation buffer was added and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The reaction was stopped with 10 μl 0.5 M EDTA, 3 μl 10% SDS and 2.5 μl 20 mg/ml Proteinase K. After extraction with phenol–chloroform and ethanol precipitation, PCR amplification was performed to acquire the libraries. All libraries were sequenced by Illumina NovaSeq 6000 according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The paired-end reads were aligned to hg38 using Bowtie2 version 2.3.3.1 with options: ‘-p 20 --very-sensitive --end-to-end --no-unal --phred33 --no-mixed -X2000’ [51]. Reads mapped in a proper pair were retained using samtools version 1.10 with option: ‘-f 2’ [63]. PCR duplicates were removed with picard version 2.23.8 with default parameters. For visualization in IGV [64], BAM file were turn into BIGWIG file using deepTools bamCoverage version 2.5.4 with options: ‘-bs 20 --smoothLength 60 -p = 10 --normalizeUsingRPKM -e 300 –ignoreDuplicates’ [56]. The CUT&Tag peaks were called using MACA2 version 2.2.7.1 with the parameters’-f BAMPE -g hs --broad --nomodel’ [57].The R package clusterProfiler version 3.10.1 was used to identify Gene Ontology (GO) terms using database including Biological Functions [65]. Heatmap for CUT&Tag signal associated with peaks was created using deepTools plotHeatmap version 3.4.3 in reference-point mode [56].

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean values ± SEM or ± SD indicated in figure legends. Sample numbers and experimental repeats are indicated in figure Legends. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed, unpaired t test unless otherwise stated. The P values were calculated with the Prism 6 software. Differences in means were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. Significance levels are: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001.

Results

Chromatin accessibility dynamics reveal AP-1 TFs impedes OC events in human somatic reprogramming

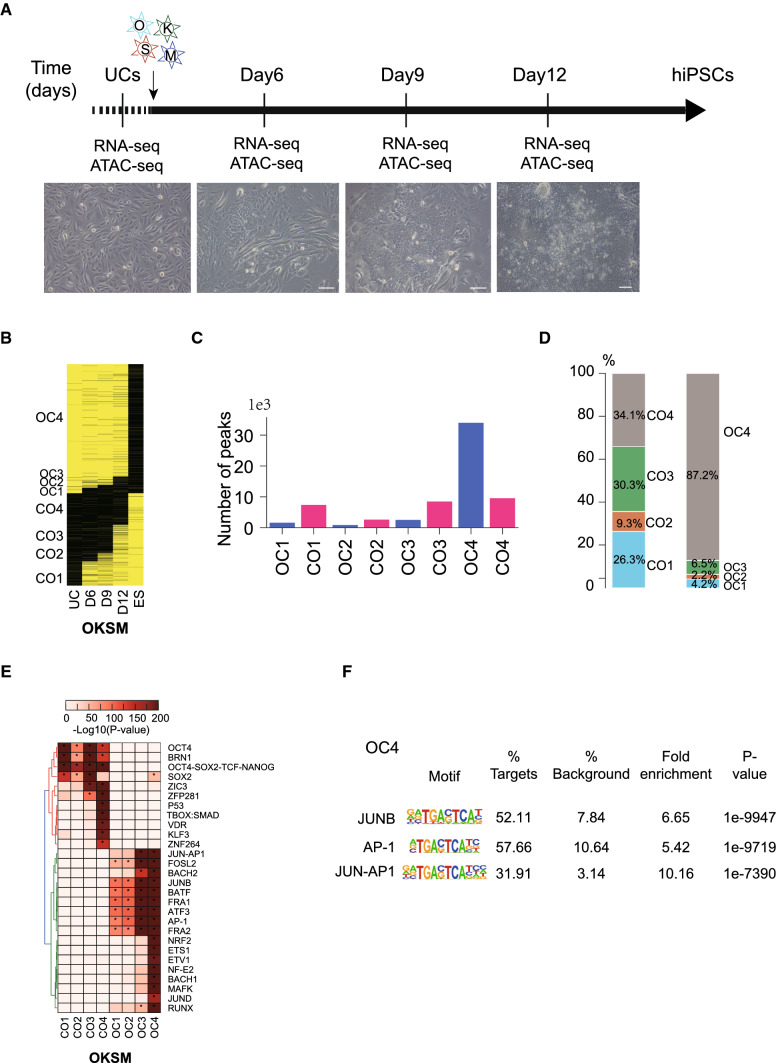

We previously characterized the chromatin accessibility dynamics during mouse somatic reprogramming by transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (ATAC-seq) [55, 66, 67]. We identified chromatin loci shifted from closed-to-open (CO) and open-to-closed (OC), including reprogramming blocking TFs, (e.g., AP-1, ETS, TEAD, RUNX, and MAD [55]) and novel facilitators (e.g., ZBTB7A/B [66]). During mouse fibroblasts reprogramming, OC dynamics is rapid while CO dynamics is slow and inefficient, suggesting the establishment of pluripotent chromatin state is a rate-limit step of mouse reprogramming. To understand the chromatin state changing dynamics during human somatic reprogramming, we performed ATAC-seq with the reprogramming process of human iPSC generation from urine cells [42, 43, 68] (Fig. 1a). By defining the CO and OC events, we found that human reprogramming shows a distinct pattern of chromatin dynamics (Fig. 1b–d). Approximately 87% somatic open loci expected to be closed during reprogramming are still open at D12 (OC4 group), suggesting human somatic reprogramming is inefficient for closing somatic relative loci (Fig. 1b–d). In contrast, during mouse reprogramming system, more than 69% somatic loci (56170/81291) are closed at the beginning of reprogramming (D1-D2) [55]. The CO loci, closed in urine cells and open in hESCs, exhibit a gradual increase with more than 65% CO loci open at D12 (Fig. 1b–d). This CO pattern is again different with the mouse one, in which more than 72% CO loci are still close at the final time point [55]. Then we concluded that in human reprogramming system, the OC process, representing the elimination of somatic chromatin properties, is possibly a rate-limit step rather than the CO process.

Fig. 1.

Chromatin accessibility dynamics in human somatic reprogramming. a Schematic for the reprogramming time course and data collection. UCs were infected with retroviral vectors containing OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and MYC and switched into reprogramming medium and then harvested for RNA-seq and ATAC-seq. b The global CO/OC status of UCs, hES and OKSM-induced reprogramming by ATAC-seq data. c Bar chart showing the number of ATAC-seq peaks for the OC/CO-defined peaks in (b). d The percentage of OC/CO-defined peaks in (b). e The motif enrichment analysis of dynamic OC/CO peaks defined in (b). f The motif enrichment analysis of OC4 from (b)

We then analyzed the transcriptional factor (TF) motif on the CO and OC loci. Each group of CO loci enriches motifs of pluripotent TFs (Fig. 1e). We noticed that loci in OC4, where the major chromatin accessibility difference occurs between D12 reprogramming cells and hESCs, enrich motifs of AP-1 family (Fig. 1f, Figure S1A).

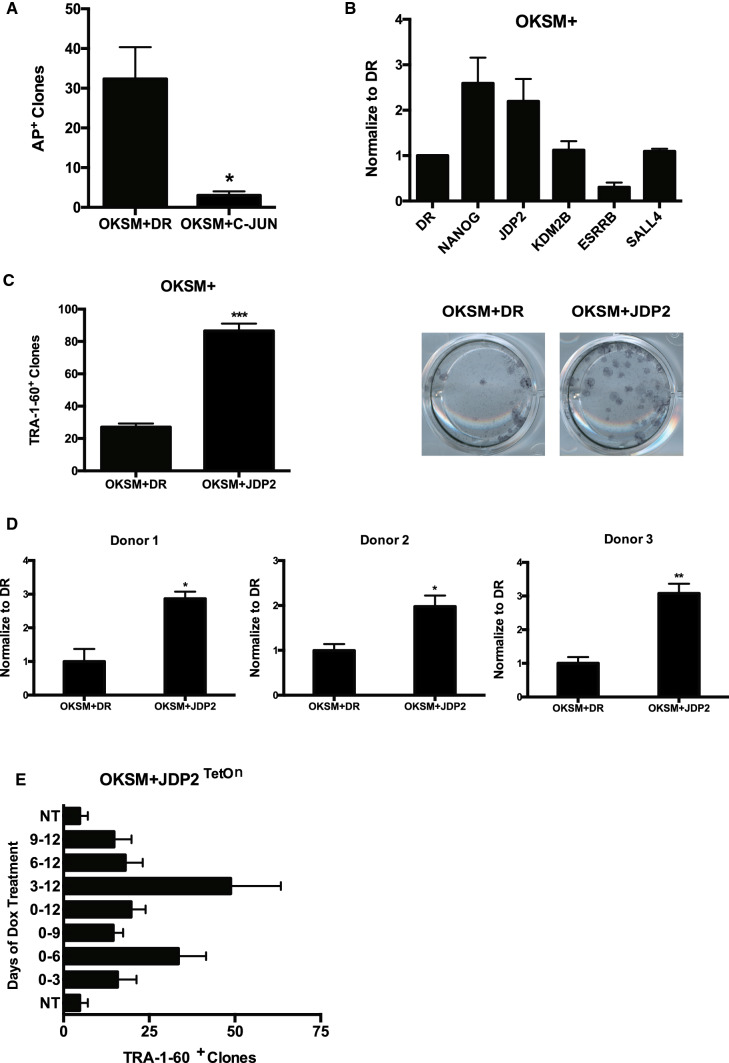

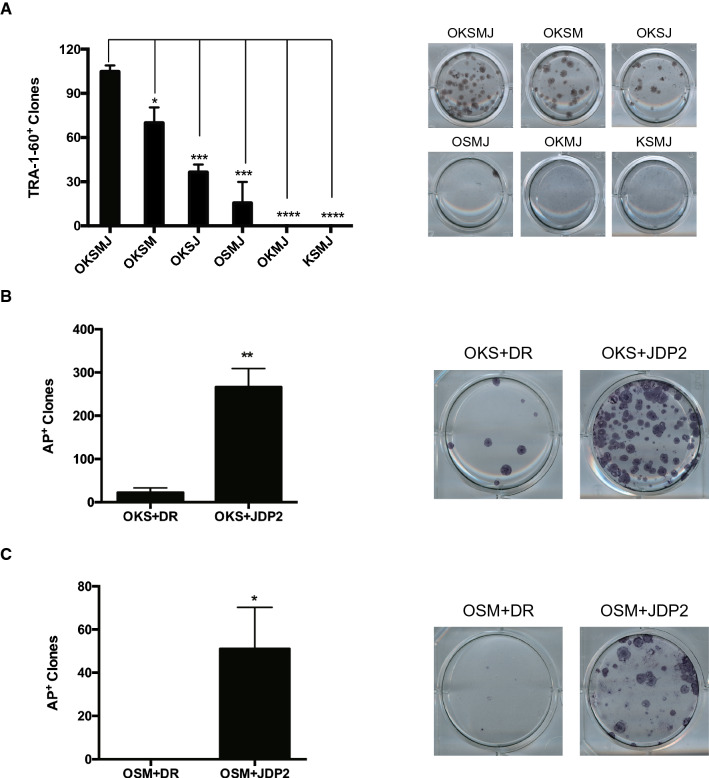

AP-1 repressor JDP2 enhances OKSM-mediated human reprogramming

We have reported that c-Jun, an important AP-1 factor, represses mouse reprogramming and induces quick differentiation of mouse ESCs [69]. In this study, we find JUN also represses human reprogramming (Fig. 2a, Figure S1B). Since there are series of AP-1 members, an efficient way to repress AP-1 activity is applying b-ZIP dimerization protein JDP2 [70]. Indeed, introduction of either JDP2 can enhance human reprogramming efficiency (Fig. 2b, c). Surprisingly, besides the reported positive control NANOG [3, 71], JDP2 can promote reprogramming at a significantly higher efficiency than known promoting factors, including ESRRB [4, 71, 72], KDM2B [73, 74] and SALL4 [71, 75] in the OKSM system (Fig. 2b, FigureS1C), emphasizing the human specific reprogramming condition.

Fig. 2.

The role of AP-1 repressor JDP2 in human reprogramming. a Bar charts showing the number of Alkaline Phosphatase (AP)-positive colonies obtained in UCs after 15 days of retroviral OKSM and AP-1 family factor JUN and added DR as a control. b Statistical bar charts showing the efficiency of different transcription factors (NANOG, JDP2, KDM2B, ESRRB and SALL4) in OKSM reprogramming system. Shown the reprogramming efficiency of different transcription factors by normalize to OKSM + DR. c JDP2 increases the efficiency in the presence of OKSM. Shown the numbers of TRA-1-60+ clones at Day 15 reprogrammed by OKSM in the presence or absence of JDP2. d Bar chart shows that JDP2 increases the efficiency from different donors. Shown the reprogramming efficiency at Day 15 reprogrammed in the presence or absence of JDP2 by normalize to OKSM + DR. e The effect of JDP2 on reprogramming at different time windows. OKSM, Retrovirus; JDP2TetOn, lentivirus carrying an inducible JDP2 code sequence under the control of TetOn promoter, Doxycycline (0.5 μg/ml) was administrated at different time windows as indicated (n = 4 wells from 2 independent experiments). The initial cell number for reprogramming is 3.5 × 104/well (p12) for OKSM protocol. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, two-tailed, unpaired t test. Statistics were from three independent experiments (n = 3 biological replicates each). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Heterogeneity is an important characteristic of urine cells exfoliated from the kidney and urinary tract epithelium. Single cell RNA-Seq analysis has the advantage of decoding the heterogeneity across distinct cell types and donor profiles of urine cells [76, 77]. Therefore, we tested the reprogramming efficiency from different donors and found JDP2 can significantly increase reprogramming efficiency of UCs from different individuals (Fig. 2d, Figure S1D).

To examine whether the enhanced reprogramming efficiency is deliver method dependent, we introduced pRlenti-hJDP2, a lentiviral vector to the reprogramming system of urine cells and validated the augmented efficiency (Figure S1E). To probe the act window of JDP2, we performed a time course experiment and showed that JDP2 exerts its promoting effect mainly at the two phases, D0–D6 and D3–D12 (Fig. 2e), overlapping at D3-D6. These results demonstrate that JDP2 increase reprogramming efficiency at early phase of reprogramming.

iPS cell lines induced with JDP2 or control DsRed (DR) were constructed, sharing identical morphology and can be passaged stably (Figure S2A). These iPSC lines have no expression of transgenic reprogramming factors (Figure S2B) and express endogenous pluripotent genes including OCT4, SOX2 and NANOG at the equal level of hESC lines (Figure S2C), supporting their pluripotency. Expression of OCT4 and NANOG is confirmed with protein level (Figure S2D). OKSM-JDP2 derived iPSCs have normal karyotype (Figure S2E). Teratoma assay showed that OKSM-JDP2 iPSCs can form all three germ layers (Figure S2F).

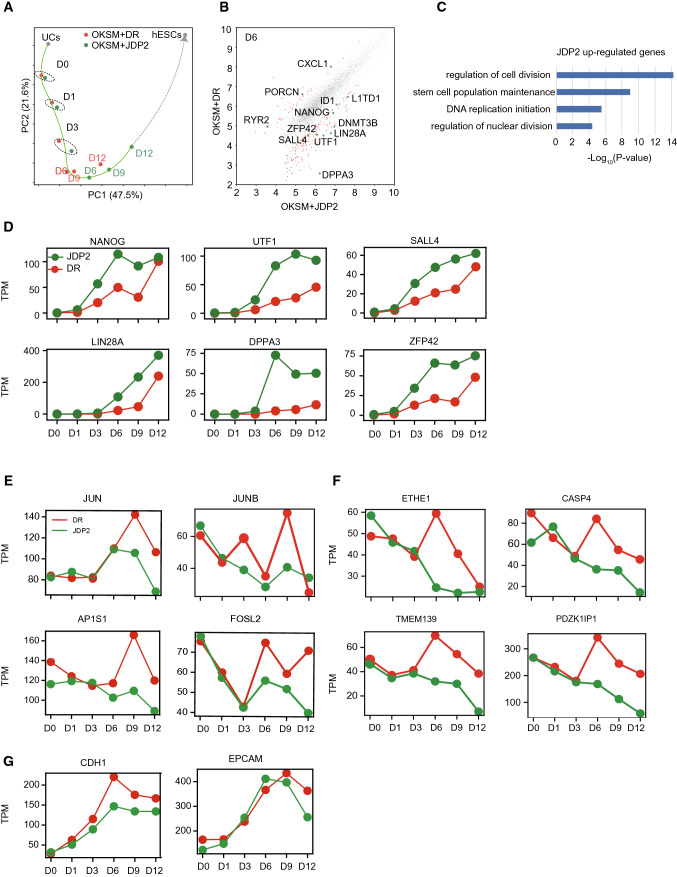

AP-1 repressor JDP2 accelerates OKSM-mediated reprogramming

We performed RNA-seq with a time course series of both OKSM + JDP2 and OKSM + DR reprogramming cells (Fig. 3a). Principle components analysis (PCA) showed that JDP2 accelerates OKSM-mediated reprogramming. By analyzing the differential-expressing genes of D6 samples, it shows that a series of pluripotent genes such as NANOG, UTF1 and LIN28A are increased (Fig. 3b). GO term enrichment shows that JDP2 upregulated genes enrich terms including stem cell population maintenance (Fig. 3c). These pluripotent genes were upregulated by JDP2 along with the reprogramming process (Fig. 3d). We also find overexpressing JDP2 can inhibit somatic gene expression, especially AP-1 family related genes such as JUN, JUNB, FOSL2 and other somatic gene ETHE1, CASP4 (Fig. 3e, f), but limited for CDH1 and EPCAM expression (Fig. 3g). These results demonstrate JDP2 promotes OKSM-mediated reprogramming though facilitating pluripotent gene reactivation and inhibiting somatic gene expression.

Fig. 3.

RNA-seq analysis in OKSM medicated-reprogramming with JDP2. a PCA of OKSM and OKSMJ-induced reprogramming by RNA-seq data. b The differentiate expressed genes between OKSM and OKSMJ-induced reprogramming at day 6. c Gene ontology (GO) analysis for JDP2 upregulated genes compare DR at day 6. d Expression level for the represented genes during OKSM- and OKSMJ-induced reprogramming from (c). e, f Expression level for the represented somatic related genes in reprogramming. g Expression level for MET- related genes in reprogramming

JDP2 plays a major role in silencing JUN-AP1 representing somatic accessible chromatin

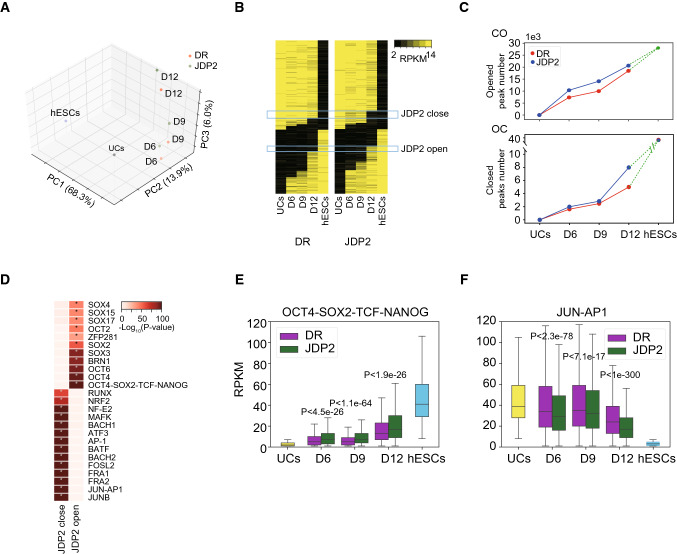

To investigate whether the JDP2 improving human reprogramming is associated with accelerated OC process by repressing AP-1 activity, we then compared the chromatin accessibility dynamics of OKSM + DR- and OKSM + JDP2-induced reprogramming. PCA shows that both reprogramming systems process similar route from urine cells (UCs) to hESCs (Fig. 4a). JDP2 slightly promotes CO process by open additional ~ 11% loci whereas greatly enhances OC process by closing more ~ 60% loci at D12 (Fig. 4b, c), suggesting JDP2 plays an important role in changing the OC dynamics. Further analysis shows that JDP2-close loci indeed enrich AP-1 motifs (Fig. 4d, Figures S3A-C), indicating JDP2 accelerates OC process by antagonist AP-1 activity.

Fig. 4.

JDP2 plays a major role in silencing JUN-AP1 representing somatic accessible chromatin. a PCA of OKSM and OKSMJ (OKSM + JDP2) -induced reprogramming by ATAC-seq data. b The global CO/OC status of OKSM (left) and OKSMJ (right) -induced reprogramming by ATAC-seq data. c The global chromatin accessibility change between UC, OKSM and OKSMJ-induced reprogramming at day 6. d TF motifs enriched for different opened/closed loci between OKSM- and OKSMJ-induced reprogramming from (b), *p < 1e-50. e, f Boxplot shows ATAC-seq signals for OCT4-SOX2-TCF-NANOG (e) and JUN-AP1 (f) motifs during OKSM- and OKSMJ-induced reprogramming. P values are from Mann–Whitney U test

On the other hand, JDP2-open loci enrich motifs of OCT4-SOX2-TCF-NANOG and several POU, SOX factors (Fig. 4d, Figures S3A-C), suggesting that JDP2 facilitates CO process and promotes pluripotent network reestablishment. Then, we selected loci containing OCT4-SOX2-TCF-NANOG and JUN-AP1 motifs as representative pluripotent and somatic sites, respectively (Fig. 4e, f). By calculating the RPKM of these sites from ATAC-seq data, we found that hESCs and UCs exclusively open pluripotent sites and somatic sites, respectively (Fig. 4e, f). During the reprogramming process, JDP2 helps releasing pluripotent sites and condensing the somatic sites (Fig. e, f). These results demonstrate that JDP2 plays a major role in silencing JUN-AP1 targeted somatic accessible chromatin, benefiting reprogramming factors to open their targets.

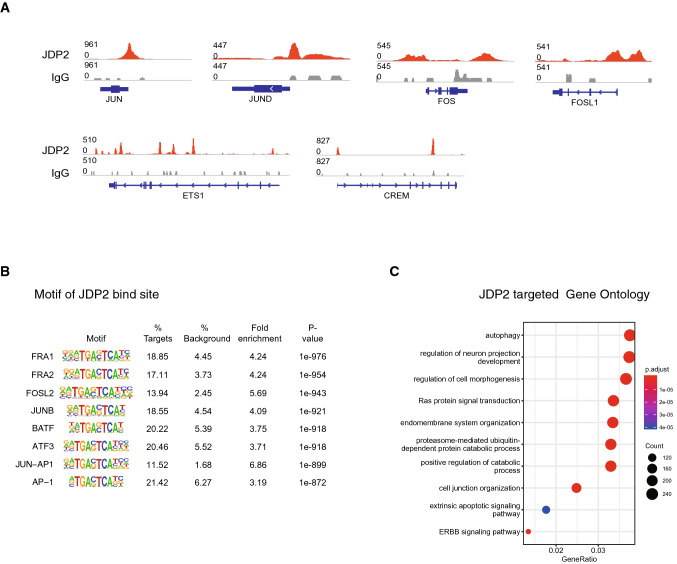

To discover JDP2's chromatin target, we performed the CUT&Tag experiment of JDP2 with a Flag label in OKSM + JDP2-induced reprogramming. We noticed JDP2 binds to many AP-1 related genes that we have previously shown to impair reprogramming, for example, JUN, JUND, FOS, FOSL1, and ETS1 (Fig. 5a). Motif analysis identified JDP2-binding motif is the classical AP-1-related motif (Fig. 5b, Figures S3D). Gene Ontology analysis indicates JDP2-targeted genes enrich terms including autophagy and regulation of cell morphogenesis (Fig. 5c). These results demonstrate that JDP2 plays a major role in binding and silencing JUN-AP1 sites to promote reprogramming.

Fig. 5.

JDP2 can directly bind to AP-1 family site promoting human reprogramming. a Genome browser track of JDP2 CUT&Tag peaks at day 3 of reprogramming. b Presence of a consensus JDP2-binding sequence in the peaks of the indicated genes. c Gene Ontology analysis of the JDP2-targeted genes of CUT&Tag data obtained from day 3 of reprogramming

JDP2 can promote reprogramming without MYC and KLF4 during human reprogramming

As JDP2 enhances human reprogramming, we further investigate the potential of JDP2 as a reprogramming factor. To this end, we performed human reprogramming by dropping out each factor individually. Interestingly, we found that JDP2 can enhance OKS-mediated human reprogramming significantly (Fig. 6a, b). Despite no iPSCs generated with OCT4/SOX2/MYC (OSM), JDP2 reprogram OSM-expressing cells with a low efficiency (Fig. 6a, c). These results indicate JDP2 is an efficient reprogramming factor in human system, suggesting the elimination of AP-1 activity is a major barrier for human somatic reprogramming.

Fig. 6.

JDP2 can promote reprogramming without MYC and KLF4 during human reprogramming. a Drop out experiments for each factor in OKSM + JDP2-medicated human reprogramming(left), TRA-1-60 staining shown in the right. b JDP2 enhances human reprogramming in the absence of MYC(left), AP staining shown in the right. c JDP2 enhances human reprogramming in the absence of KLF4 (left), AP staining shown in the right. Data are represented as mean ± SEM, two-tailed, unpaired t test. Statistics were from three independent experiments (n = 3 biological replicates each). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01

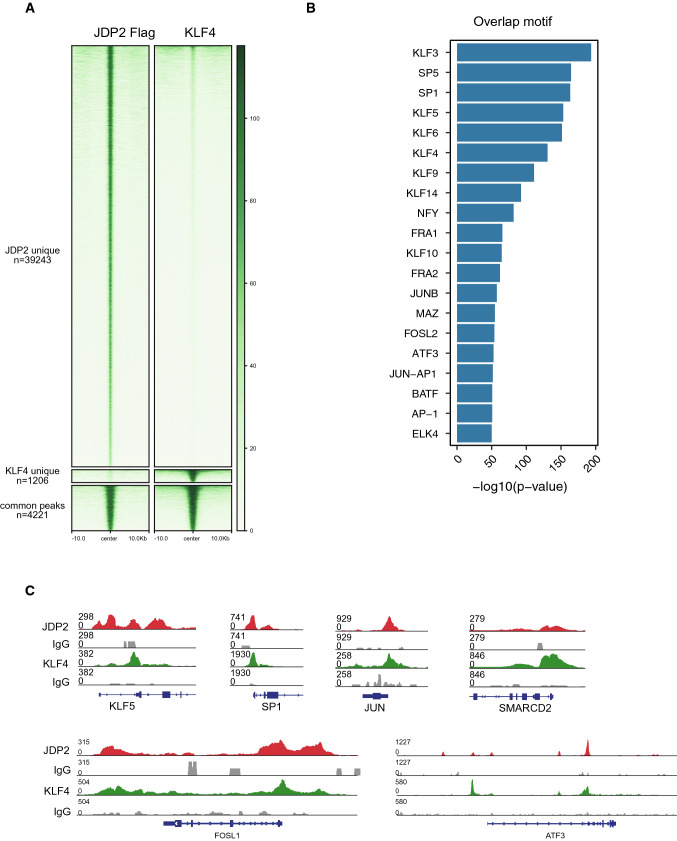

MYC is known as an unnecessary factor in mouse reprograming [10, 78]. To further investigate the difference between JDP2 and KLF4 as reprogramming factors, we performed the CUT&Tag experiment of JDP2 and KLF4 under OSM + JDP2 and OSM + KLF4 systems, correspondingly. We showed a substantial overlap of JDP2 and KLF4 targets (Fig. 7a). Interestingly, KLF4 occupies 9.7% of the JDP2-binding sites, while JDP2 deposits on 77.8% of the Klf4-targeted loci (Fig. 7a). Motif analysis identified that KLF and AP-1 family transcription factors enrich these overlapping sites (Fig. 7b). Correspondingly, the common binding sites of JDP2 and KLF4 on day 3 include KLF5 [79] and SMARCD2 [80], which is shown in previous KLF4 studies (Fig. 7c). Further, we found the common binding sites also include many AP-1 related genes, such as JUN, FOSL1 and ATF3 (Fig. 7c). In conclusion, our data show KLF4 has unique ability to promote reprogramming, and JDP2 can partially rescue the loss of KLF4 in urine cell reprogramming.

Fig. 7.

JDP2 can partly bind to KLF4 binding site promoting human reprogramming. a Heatmap representation of JDP2 and KLF4 occupancy at all annotated gene promoters (10 kb flanking TSSs of Refseq genes) in OSM + JDP2/OSM + KLF4-induced reprogramming at day 3. JDP2 was fused with a 3xFlag tag, co-expressed with OSM during reprogramming and precipitated using an anti-Flag antibody; KLF4 was precipitated using a anti-KLF4 antibody with OSM + K during reprogramming. b Motifs of JDP2 and KLF4 shared binding sites during reprogramming. c Genome browser track of JDP2, KLF4 CUT&Tag common binding site at day 3 of reprogramming (OSM + J/OSM + K)

Discussion

Chromatin remodeling is a fundamental process during cell fate transitions [21, 55]. Somatic reprogramming requires the close of the somatic loci and the open of the pluripotent loci. In addition, it is more important to close the accessible somatic loci rather than open the pluripotent loci for iPSCs in mouse reprogramming system. As an example, we have previously reported OC dynamics is rapid while CO dynamics is slow and inefficient in mouse fibroblasts reprogramming [55]. However, in our study, we observed the opposite trend of chromatin accessibility dynamics, demonstrating the vital difference between mouse and human reprogramming. We then propose that the OC dynamics, which represents somatic program erasure while processes slowly, is a rate-limited step of human iPSCs induction. A major cause inducing chromatin accessibility dynamic changing is the transcriptional factor regulation. These results suggest that additional factors or small molecule compounds would enhance the efficiency of human reprogramming via breaking the OC barrier.

AP-1 takes a center stage in chromatin accessibility and several specific members of the AP-1 complex like JUN, FOS were redundant in mouse embryo fibroblasts during reprogramming [21, 55, 81]. Therefore, cells failed to reprogram when maintaining the MEF chromatin state or overexpressing c-Jun and other somatic AP-1 TFs [19, 55, 69]. In our study, AP-1 family also plays a key role in human OKSM-mediated reprogramming.

In human cancer, JDP2 is an inhibitor to repress the ROS production in the cellular adaptive response [82]. Human medulloblastoma cells can be reprogrammed to incomplete iPSCs (iPSC-like) by the combination of OCT4 and JDP2. iPSC-like exhibits weaker pluripotency staining, except for SOX2, and only two germ layers of the teratoma [82]. In our study, UCs can be reprogrammed to human iPSCs completely comparable with hESC. In addition, it is critical for cooperative binding of OSK in mouse reprogramming. OSK in combinations with MYC displayed strong promoter bias, whereas combinations of OSK binding without MYC have a bias of targeted active enhancers in mouse system [19]. Whether JDP2 can replace one or more reprogramming factors is also interesting. In our study, we have found that replacing MYC with AP-1 repressor JDP2 significantly enhances OKS-mediated human reprogramming. Besides, using JDP2 instead KLF4 induces reprogramming with a low efficiency. These observations are different from mouse reprogramming that we previously reported [67, 69]. Further investigation on AP-1 towards somatic cell reprogramming would focus on using dominant-negative repressor of AP-1 members to avoid functional redundancy among its family members [69] as well as targeting AP-1 with specific chemical compounds.

Consequently, AP-1 activity is observed among OC loci and an AP-1 repressor is applied to manipulate OC chromatin dynamics. Indeed, JDP2 accelerates OC dynamics by facilitating closing of those somatic accessible loci harboring AP-1 motif. The promoting OC dynamics also benefit the CO process which is mostly mediated by reprogramming pluripotent factors OCT4/SOX2. These results demonstrate that AP-1 serves as a conserved mechanism to block the transition from somatic cell fate to pluripotent one, suggesting chromatin accessibility is a reliable method to reveal regulators during cell fate transition.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all members who volunteer to donate urine cells to this study. We thank all members in the laboratory for experiment assistant and constructive discussion. We appreciate for Guangzhou Branch of the Supercomputing Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences. We also thank Dr. Peng Li for providing NOD/SCID mice, Zhizheng Zhai for the help of teratoma experiments, and Tian Zhang for the help of human reprogramming experiments.

Author contributions

YTL, JPH, JL, and JKC: designed the experiments. YTL: carried out the collection and expansion of UCs, iPSC reprogramming, iPSC characterization experiments. YTL: performed RNA-seq, ATAC-seq and CUT&Tag experiments. HL and LG: carried out RNA and ATAC sequence. YTL and JC: carried out qPCR. YTL and YJL: derived iPSC lines. YTL and BW: carried out plasmid construction. JPH and RHC: analyzed RNA-seq, ATAC-seq and CUT&Tag data. YTL and JKC: interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. JW and DQP: helped to improve it. JKC: conceived and supervised the whole study. All the authors revised and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFA0110200 and 2018YFE0204800), the Key Research and Development Program of Guangzhou Regenerative Medicine and Health Guangdong Laboratory (2018GZR110104003 and 2018GZR110105012), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (201804020052), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771424, 31401084 and 31830060), and the Frontier Science Research Program of the CAS (ZDBS-LY-SM007), Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province, China (2020B1212060052).

Availability of data and material

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

All of the animal experiments were performed with the approval and according to the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all individuals for being included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jing Liu, Email: Liu_jing@gibh.ac.cn.

Jiekai Chen, Email: Chen_jiekai@gibh.ac.cn.

References

- 1.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131(5):861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, Stewart R, Slukvin II, Thomson JA. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318(5858):1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng B, Jiang J, Kraus P, Ng JH, Heng JC, Chan YS, Yaw LP, Zhang W, Loh YH, Han J, Vega VB, Cacheux-Rataboul V, Lim B, Lufkin T, Ng HH. Reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells with orphan nuclear receptor Esrrb. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(2):197–203. doi: 10.1038/ncb1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heng JC, Feng B, Han J, Jiang J, Kraus P, Ng JH, Orlov YL, Huss M, Yang L, Lufkin T, Lim B, Ng HH. The nuclear receptor Nr5a2 can replace Oct4 in the reprogramming of murine somatic cells to pluripotent cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(2):167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanna J, Saha K, Pando B, van Zon J, Lengner CJ, Creyghton MP, van Oudenaarden A, Jaenisch R. Direct cell reprogramming is a stochastic process amenable to acceleration. Nature. 2009;462(7273):595–601. doi: 10.1038/nature08592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li W, Li K, Wei W, Ding S. Chemical approaches to stem cell biology and therapeutics. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13(3):270–283. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. A decade of transcription factor-mediated reprogramming to pluripotency. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(3):183–193. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Liu J, Han Q, Qin D, Xu J, Chen Y, Yang J, Song H, Yang D, Peng M, He W, Li R, Wang H, Gan Y, Ding K, Zeng L, Lai L, Esteban MA, Pei D. Towards an optimized culture medium for the generation of mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(40):31066–31072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.139436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Liu J, Chen Y, Yang J, Liu H, Zhao X, Mo K, Song H, Guo L, Chu S, Wang D, Ding K, Pei D. Rational optimization of reprogramming culture conditions for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells with ultra-high efficiency and fast kinetics. Cell Res. 2011;21(6):884–894. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li R, Liang J, Ni S, Zhou T, Qing X, Li H, He W, Chen J, Li F, Zhuang Q, Qin B, Xu J, Li W, Yang J, Gan Y, Qin D, Feng S, Song H, Yang D, Zhang B, Zeng L, Lai L, Esteban MA, Pei D. A mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition initiates and is required for the nuclear reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(1):51–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samavarchi-Tehrani P, Golipour A, David L, Sung HK, Beyer TA, Datti A, Woltjen K, Nagy A, Wrana JL. Functional genomics reveals a BMP-driven mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in the initiation of somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(1):64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wernig M, Lengner CJ, Hanna J, Lodato MA, Steine E, Foreman R, Staerk J, Markoulaki S, Jaenisch R. A drug-inducible transgenic system for direct reprogramming of multiple somatic cell types. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(8):916–924. doi: 10.1038/nbt1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maherali N, Ahfeldt T, Rigamonti A, Utikal J, Cowan C, Hochedlinger K. A high-efficiency system for the generation and study of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(3):340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Polo JM, Anderssen E, Walsh RM, Schwarz BA, Nefzger CM, Lim SM, Borkent M, Apostolou E, Alaei S, Cloutier J, Bar-Nur O, Cheloufi S, Stadtfeld M, Figueroa ME, Robinton D, Natesan S, Melnick A, Zhu J, Ramaswamy S, Hochedlinger K. A molecular roadmap of reprogramming somatic cells into iPS cells. Cell. 2012;151(7):1617–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Liu H, Liu J, Qi J, Wei B, Yang J, Liang H, Chen Y, Wu Y, Guo L, Zhu J, Zhao X, Peng T, Zhang Y, Chen S, Li X, Li D, Wang T, Pei D. H3K9 methylation is a barrier during somatic cell reprogramming into iPSCs. Nat Genet. 2013;45(1):34–42. doi: 10.1038/ng.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golipour A, David L, Liu Y, Jayakumaran G, Hirsch CL, Trcka D, Wrana JL. A late transition in somatic cell reprogramming requires regulators distinct from the pluripotency network. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(6):769–782. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rais Y, Zviran A, Geula S, Gafni O, Chomsky E, Viukov S, Mansour AA, Caspi I, Krupalnik V, Zerbib M, Maza I, Mor N, Baran D, Weinberger L, Jaitin DA, Lara-Astiaso D, Blecher-Gonen R, Shipony Z, Mukamel Z, Hagai T, Gilad S, Amann-Zalcenstein D, Tanay A, Amit I, Novershtern N, Hanna JH. Deterministic direct reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Nature. 2013;502(7469):65–70. doi: 10.1038/nature12587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chronis C, Fiziev P, Papp B, Butz S, Bonora G, Sabri S, Ernst J, Plath K. Cooperative binding of transcription factors orchestrates reprogramming. Cell. 2017;168(3):442–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Malley J, Skylaki S, Iwabuchi KA, Chantzoura E, Ruetz T, Johnsson A, Tomlinson SR, Linnarsson S, Kaji K. High-resolution analysis with novel cell-surface markers identifies routes to iPS cells. Nature. 2013;499(7456):88–91. doi: 10.1038/nature12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knaupp AS, Buckberry S, Pflueger J, Lim SM, Ford E, Larcombe MR, Rossello FJ, de Mendoza A, Alaei S, Firas J, Holmes ML, Nair SS, Clark SJ, Nefzger CM, Lister R, Polo JM. Transient and permanent reconfiguration of chromatin and transcription factor occupancy drive reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21(6):834–845. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Sasaki A, Yamamoto M, Nakamura M, Sutou K, Osafune K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotency in human somatic cells via a transient state resembling primitive streak-like mesendoderm. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3678. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu X, Nefzger CM, Rossello FJ, Chen J, Knaupp AS, Firas J, Ford E, Pflueger J, Paynter JM, Chy HS, O'Brien CM, Huang C, Mishra K, Hodgson-Garms M, Jansz N, Williams SM, Blewitt ME, Nilsson SK, Schittenhelm RB, Laslett AL, Lister R, Polo JM. Comprehensive characterization of distinct states of human naive pluripotency generated by reprogramming. Nat Methods. 2017;14(11):1055–1062. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu X, Ouyang JF, Rossello FJ, Tan JP, Davidson KC, Valdes DS, Schroder J, Sun YBY, Chen J, Knaupp AS, Sun G, Chy HS, Huang Z, Pflueger J, Firas J, Tano V, Buckberry S, Paynter JM, Larcombe MR, Poppe D, Choo XY, O'Brien CM, Pastor WA, Chen D, Leichter AL, Naeem H, Tripathi P, Das PP, Grubman A, Powell DR, Laslett AL, David L, Nilsson SK, Clark AT, Lister R, Nefzger CM, Martelotto LG, Rackham OJL, Polo JM. Reprogramming roadmap reveals route to human induced trophoblast stem cells. Nature. 2020;586(7827):101–107. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2734-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brons IG, Smithers LE, Trotter MW, Rugg-Gunn P, Sun B, de Sousa C, Lopes SM, Howlett SK, Clarkson A, Ahrlund-Richter L, Pedersen RA, Vallier L. Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature. 2007;448(7150):191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature05950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang K, Maruyama T, Fan G. The naive state of human pluripotent stem cells: a synthesis of stem cell and preimplantation embryo transcriptome analyses. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(4):410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nichols J, Smith A. Naive and primed pluripotent states. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(6):487–492. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ware CB, Nelson AM, Mecham B, Hesson J, Zhou W, Jonlin EC, Jimenez-Caliani AJ, Deng X, Cavanaugh C, Cook S, Tesar PJ, Okada J, Margaretha L, Sperber H, Choi M, Blau CA, Treuting PM, Hawkins RD, Cirulli V, Ruohola-Baker H. Derivation of naive human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(12):4484–4489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319738111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Chen S, Jiang Q, Deng J, Cheng F, Lin Y, Cheng L, Ye Y, Chen X, Yao Y, Zhang X, Shi G, Dai L, Su X, Peng Y, Deng H. TFAP2C facilitates somatic cell reprogramming by inhibiting c-Myc-dependent apoptosis and promoting mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(6):482. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2684-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu X, Sun H, Qi J, Wang L, He S, Liu J, Feng C, Chen C, Li W, Guo Y, Qin D, Pan G, Chen J, Pei D, Zheng H. Sequential introduction of reprogramming factors reveals a time-sensitive requirement for individual factors and a sequential EMT-MET mechanism for optimal reprogramming. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(7):829–838. doi: 10.1038/ncb2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pei D, Shu X, Gassama-Diagne A, Thiery JP. Mesenchymal-epithelial transition in development and reprogramming. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(1):44–53. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0195-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu X, Zhang L, Mao SQ, Li Z, Chen J, Zhang RR, Wu HP, Gao J, Guo F, Liu W, Xu GF, Dai HQ, Shi YG, Li X, Hu B, Tang F, Pei D, Xu GL. Tet and TDG mediate DNA demethylation essential for mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14(4):512–522. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cacchiarelli D, Trapnell C, Ziller MJ, Soumillon M, Cesana M, Karnik R, Donaghey J, Smith ZD, Ratanasirintrawoot S, Zhang X, Ho Sui SJ, Wu Z, Akopian V, Gifford CA, Doench J, Rinn JL, Daley GQ, Meissner A, Lander ES, Mikkelsen TS. Integrative analyses of human reprogramming reveal dynamic nature of induced pluripotency. Cell. 2015;162(2):412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, Ding S. Small molecules that modulate embryonic stem cell fate and somatic cell reprogramming. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31(1):36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou P, Li Y, Zhang X, Liu C, Guan J, Li H, Zhao T, Ye J, Yang W, Liu K, Ge J, Xu J, Zhang Q, Zhao Y, Deng H. Pluripotent stem cells induced from mouse somatic cells by small-molecule compounds. Science. 2013;341(6146):651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1239278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loewer S, Cabili MN, Guttman M, Loh YH, Thomas K, Park IH, Garber M, Curran M, Onder T, Agarwal S, Manos PD, Datta S, Lander ES, Schlaeger TM, Daley GQ, Rinn JL. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-RoR modulates reprogramming of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42(12):1113–1117. doi: 10.1038/ng.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narva E, Rahkonen N, Emani MR, Lund R, Pursiheimo JP, Nasti J, Autio R, Rasool O, Denessiouk K, Lahdesmaki H, Rao A, Lahesmaa R. RNA-binding protein L1TD1 interacts with LIN28 via RNA and is required for human embryonic stem cell self-renewal and cancer cell proliferation. Stem Cells. 2012;30(3):452–460. doi: 10.1002/stem.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emani MR, Narva E, Stubb A, Chakroborty D, Viitala M, Rokka A, Rahkonen N, Moulder R, Denessiouk K, Trokovic R, Lund R, Elo LL, Lahesmaa R. The L1TD1 protein interactome reveals the importance of post-transcriptional regulation in human pluripotency. Stem cell reports. 2015;4(3):519–528. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwabuchi KA, Yamakawa T, Sato Y, Ichisaka T, Takahashi K, Okita K, Yamanaka S. ECAT11/L1td1 is enriched in ESCs and rapidly activated during iPSC generation, but it is dispensable for the maintenance and induction of pluripotency. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(5):e20461. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang J, Xie G, Singh M, Ghanbarian AT, Rasko T, Szvetnik A, Cai H, Besser D, Prigione A, Fuchs NV, Schumann GG, Chen W, Lorincz MC, Ivics Z, Hurst LD, Izsvak Z. Primate-specific endogenous retrovirus-driven transcription defines naive-like stem cells. Nature. 2014;516(7531):405–409. doi: 10.1038/nature13804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohnuki M, Tanabe K, Sutou K, Teramoto I, Sawamura Y, Narita M, Nakamura M, Tokunaga Y, Watanabe A, Yamanaka S, Takahashi K. Dynamic regulation of human endogenous retroviruses mediates factor-induced reprogramming and differentiation potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(34):12426–12431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413299111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou T, Benda C, Duzinger S, Huang Y, Li X, Li Y, Guo X, Cao G, Chen S, Hao L, Chan YC, Ng KM, Ho JC, Wieser M, Wu J, Redl H, Tse HF, Grillari J, Grillari-Voglauer R, Pei D, Esteban MA. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from urine. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(7):1221–1228. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011010106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen G, Gulbranson DR, Hou Z, Bolin JM, Ruotti V, Probasco MD, Smuga-Otto K, Howden SE, Diol NR, Propson NE, Wagner R, Lee GO, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Teng JM, Thomson JA. Chemically defined conditions for human iPSC derivation and culture. Nat Methods. 2011;8(5):424–429. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beers J, Gulbranson DR, George N, Siniscalchi LI, Jones J, Thomson JA, Chen G. Passaging and colony expansion of human pluripotent stem cells by enzyme-free dissociation in chemically defined culture conditions. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(11):2029–2040. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manos PD, Ratanasirintrawoot S, Loewer S, Daley GQ, Schlaeger TM. Live-cell immunofluorescence staining of human pluripotent stem cells. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/9780470151808.sc01c12s19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Onder TT, Kara N, Cherry A, Sinha AU, Zhu N, Bernt KM, Cahan P, Marcarci BO, Unternaehrer J, Gupta PB, Lander ES, Armstrong SA, Daley GQ. Chromatin-modifying enzymes as modulators of reprogramming. Nature. 2012;483(7391):598–602. doi: 10.1038/nature10953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang L, Huang W, Su H, Xue Y, Su Z, Liao B, Wang H, Bao X, Qin D, He J, Wu W, So KF, Pan G, Pei D. Generation of integration-free neural progenitor cells from cells in human urine. Nat Methods. 2013;10(1):84–89. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xue Y, Cai X, Wang L, Liao B, Zhang H, Shan Y, Chen Q, Zhou T, Li X, Hou J, Chen S, Luo R, Qin D, Pei D, Pan G. Generating a non-integrating human induced pluripotent stem cell bank from urine-derived cells. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e70573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Esteban MA, Wang T, Qin B, Yang J, Qin D, Cai J, Li W, Weng Z, Chen J, Ni S, Chen K, Li Y, Liu X, Xu J, Zhang S, Li F, He W, Labuda K, Song Y, Peterbauer A, Wolbank S, Redl H, Zhong M, Cai D, Zeng L, Pei D. Vitamin C enhances the generation of mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(1):71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Z, Yang X, He J, Liu J, Wu F, Yu S, Liu Y, Lin R, Liu H, Cui Y, Zhou C, Wang X, Wu J, Cao S, Guo L, Lin L, Wang T, Peng X, Qiang B, Hutchins AP, Pei D, Chen J. Kdm2b regulates somatic reprogramming through variant PRC1 complex-dependent function. Cell Rep. 2017;21(8):2160–2170. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 2010;11(2):R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li D, Liu J, Yang X, Zhou C, Guo J, Wu C, Qin Y, Guo L, He J, Yu S, Liu H, Wang X, Wu F, Kuang J, Hutchins AP, Chen J, Pei D. Chromatin accessibility dynamics during iPSC reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21(6):819–833. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ramirez F, Ryan DP, Gruning B, Bhardwaj V, Kilpert F, Richter AS, Heyne S, Dundar F, Manke T. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W160–165. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, Liu XS. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9(9):R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38(4):576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hutchins AP, Jauch R, Dyla M, Miranda-Saavedra D. glbase: a framework for combining, analyzing and displaying heterogeneous genomic and high-throughput sequencing data. Cell Regen (Lond) 2014;3(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2045-9769-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaya-Okur HS, Janssens DH, Henikoff JG, Ahmad K, Henikoff S. Efficient low-cost chromatin profiling with CUT&Tag. Nat Protoc. 2020;15(10):3264–3283. doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-0373-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaya-Okur HS, Wu SJ, Codomo CA, Pledger ES, Bryson TD, Henikoff JG, Ahmad K, Henikoff S. CUT&Tag for efficient epigenomic profiling of small samples and single cells. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1930. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09982-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu B, Xu Q, Wang Q, Feng S, Lai F, Wang P, Zheng F, Xiang Y, Wu J, Nie J, Qiu C, Xia W, Li L, Yu G, Lin Z, Xu K, Xiong Z, Kong F, Liu L, Huang C, Yu Y, Na J, Xie W. The landscape of RNA Pol II binding reveals a stepwise transition during ZGA. Nature. 2020;587(7832):139–144. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2847-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, Genome Project Data Processing S The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G, Mesirov JP. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(1):24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16(5):284–287. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu S, Zhou C, Cao S, He J, Cai B, Wu K, Qin Y, Huang X, Xiao L, Ye J, Xu S, Xie W, Kuang J, Chu S, Guo J, Liu H, Pang W, Guo L, Zeng M, Wang X, Luo R, Li C, Zhao G, Wang B, Wu L, Chen J, Liu J, Pei D. BMP4 resets mouse epiblast stem cells to naive pluripotency through ZBTB7A/B-mediated chromatin remodelling. Nat Cell Biol. 2020;22(6):651–662. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-0516-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang B, Wu L, Li D, Liu Y, Guo J, Li C, Yao Y, Wang Y, Zhao G, Wang X, Fu M, Liu H, Cao S, Wu C, Yu S, Zhou C, Qin Y, Kuang J, Ming J, Chu S, Yang X, Zhu P, Pan G, Chen J, Liu J, Pei D. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic fibroblasts by Jdp2-Jhdm1b-Mkk6-Glis1-Nanog-Essrb-Sall4. Cell Rep. 2019;27(12):3473–3485. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mali P, Chou BK, Yen J, Ye Z, Zou J, Dowey S, Brodsky RA, Ohm JE, Yu W, Baylin SB, Yusa K, Bradley A, Meyers DJ, Mukherjee C, Cole PA, Cheng L. Butyrate greatly enhances derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by promoting epigenetic remodeling and the expression of pluripotency-associated genes. Stem Cells. 2010;28(4):713–720. doi: 10.1002/stem.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu J, Han Q, Peng T, Peng M, Wei B, Li D, Wang X, Yu S, Yang J, Cao S, Huang K, Hutchins AP, Liu H, Kuang J, Zhou Z, Chen J, Wu H, Guo L, Chen Y, Li X, Liao B, He W, Song H, Yao H, Pan G, Pei D. The oncogene c-Jun impedes somatic cell reprogramming. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(7):856–867. doi: 10.1038/ncb3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Aronheim A, Zandi E, Hennemann H, Elledge SJ, Karin M. Isolation of an AP-1 repressor by a novel method for detecting protein-protein interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(6):3094–3102. doi: 10.1128/MCB.17.6.3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Buganim Y, Markoulaki S, van Wietmarschen N, Hoke H, Wu T, Ganz K, Akhtar-Zaidi B, He Y, Abraham BJ, Porubsky D, Kulenkampff E, Faddah DA, Shi L, Gao Q, Sarkar S, Cohen M, Goldmann J, Nery JR, Schultz MD, Ecker JR, Xiao A, Young RA, Lansdorp PM, Jaenisch R. The developmental potential of iPSCs is greatly influenced by reprogramming factor selection. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15(3):295–309. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang F, Ren Y, Li H, Wang H. ESRRB plays a crucial role in the promotion of porcine cell reprograming. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(2):1601–1611. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liang G, He J, Zhang Y. Kdm2b promotes induced pluripotent stem cell generation by facilitating gene activation early in reprogramming. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(5):457–466. doi: 10.1038/ncb2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang T, Chen K, Zeng X, Yang J, Wu Y, Shi X, Qin B, Zeng L, Esteban MA, Pan G, Pei D. The histone demethylases Jhdm1a/1b enhance somatic cell reprogramming in a vitamin-C-dependent manner. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9(6):575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tsubooka N, Ichisaka T, Okita K, Takahashi K, Nakagawa M, Yamanaka S. Roles of Sall4 in the generation of pluripotent stem cells from blastocysts and fibroblasts. Genes Cells: Devot Mol Cell Mech. 2009;14(6):683–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li D, Wang L, Hou J, Shen Q, Chen Q, Wang X, Du J, Cai X, Shan Y, Zhang T, Zhou T, Shi X, Li Y, Zhang H, Pan G. Optimized approaches for generation of integration-free iPSCs from human urine-derived cells with small molecules and autologous feeder. Stem cell reports. 2016;6(5):717–728. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Y, Zhao Y, Zhao Z, Li D, Nie H, Sun Y, Feng X, Zhang T, Ma Y, Nie J, Cai G, Chen X, Zuo W. Single-cell RNA-Seq analysis identified kidney progenitor cells from human urine. Protein Cell. 2021;12(4):305–312. doi: 10.1007/s13238-020-00816-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nakagawa M, Koyanagi M, Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Okita K, Mochiduki Y, Takizawa N, Yamanaka S. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(1):101–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Di Giammartino DC, Kloetgen A, Polyzos A, Liu Y, Kim D, Murphy D, Abuhashem A, Cavaliere P, Aronson B, Shah V, Dephoure N, Stadtfeld M, Tsirigos A, Apostolou E. KLF4 is involved in the organization and regulation of pluripotency-associated three-dimensional enhancer networks. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(10):1179–1190. doi: 10.1038/s41556-019-0390-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sardina JL, Collombet S, Tian TV, Gomez A, Di Stefano B, Berenguer C, Brumbaugh J, Stadhouders R, Segura-Morales C, Gut M, Gut IG, Heath S, Aranda S, Di Croce L, Hochedlinger K, Thieffry D, Graf T. Transcription factors drive Tet2-mediated enhancer demethylation to reprogram cell fate. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23(5):727–741. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Biddie SC, John S, Sabo PJ, Thurman RE, Johnson TA, Schiltz RL, Miranda TB, Sung MH, Trump S, Lightman SL, Vinson C, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Hager GL. Transcription factor AP1 potentiates chromatin accessibility and glucocorticoid receptor binding. Mol Cell. 2011;43(1):145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chiou SS, Wang SS, Wu DC, Lin YC, Kao LP, Kuo KK, Wu CC, Chai CY, Lin CL, Lee CY, Liao YM, Wuputra K, Yang YH, Wang SW, Ku CC, Nakamura Y, Saito S, Hasegawa H, Yamaguchi N, Miyoshi H, Lin CS, Eckner R, Yokoyama KK. Control of oxidative stress and generation of induced pluripotent stem cell-like cells by jun dimerization protein 2. Cancers (Basel) 2013;5(3):959–984. doi: 10.3390/cancers5030959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.