Abstract

Translational control is a fundamental mechanism regulating animal germ cell development. Gonadal somatic cells provide support and microenvironment for germ cell development to ensure fertility, yet the roles of translational control in gonadal somatic compartment remain largely undefined. We found that mouse homolog of conserved fly germline stem cell factor Pumilio, PUM1, is absent in oocytes of all growing follicles after the primordial follicle stage, instead, it is highly expressed in somatic compartments of ovaries. Global loss of Pum1, not oocyte-specific loss of Pum1, led to a significant reduction in follicular number and size as well as fertility. Whole-genome identification of PUM1 targets in ovarian somatic cells revealed an enrichment of cell proliferation pathway, including 48 key regulators of cell phase transition. Consistently granulosa cells proliferation is reduced and the protein expression of the PUM-bound Cell Cycle Regulators (PCCR) were altered accordingly in mutant ovaries, and specifically in granulosa cells. Increase in negative regulator expression and decrease in positive regulators in the mutant ovaries support a coordinated translational control of somatic cell cycle program via PUM proteins. Furthermore, postnatal knockdown, but not postnatal oocyte-specific loss, of Pum1 in Pum2 knockout mice reduced follicular growth and led to similar expression alteration of PCCR genes, supporting a critical role of PUM-mediated translational control in ovarian somatic cells for mammalian female fertility. Finally, expression of human PUM protein and its regulated cell cycle targets exhibited significant correlation with ovarian cancer and prognosis for cancer survival. Hence, PUMILIO-mediated cell cycle regulation represents an important mechanism in mammalian female reproduction and human cancer biology.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-022-04254-w.

Keywords: Pumilio, Cdkn1b, RNA binding proteins, Posttranscriptional regulation, eCLIP, Granulosa cells, Cell cycle, PCCR

Introduction

Proper regulation of cell cycle is fundamental to organism growth and development, and when disrupted, often leads to diseases, notably cancers. A large number of cell cycle regulators have been identified, for example, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) and cyclins drive the cells through the four phases (G1, S, G2 and M) of the cell cycle, while negative regulators such as cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) halt proliferation by binding to CDKs and initiating cell cycle arrest [1], level and timing of gene expression of those cell cycle regulators must be precisely controlled and coordinated to ensure smooth transition through different phases of cell cycle and exit of cell cycle phases during cell proliferation and differentiation [2].

While transcription regulation and protein degradation are known to regulate the dynamic expression of key cell cycle regulators, increasing evidence also supports the role of translational control in cell cycle regulation [3–5]. Recent genome-wide analyses of gene expression using transcriptomics, proteomics, and ribosome-profiling approaches uncovered an active translation program of cell cycle genes throughout the cell cycle in yeast and cultured cells [6–8], supporting an essential role of translational control of cell cycle during cell proliferation and growth. How such a regulatory program functions in the context of physiology or contributes to mammalian organ development or human diseases remain largely unknown. Identifying key regulators of such cell cycle translational program and dissecting their regulatory pathways in tissues and animal models could reveal the extent of this new layer of cell cycle control in organ development and diseases.

Translational control is a prominent feature of gene regulation in germ cell development, many well-known translational regulators were initially discovered for their roles in fertility [5]. One of the highly conserved germ cell translational regulators, PUMILIO proteins, belong to the PUF (PUMILIO/FBF) family and play critical roles in germ cell developmental decision and differentiation in Drosophila and worms [5, 9, 10]. Vertebrate PUM proteins control translation of key molecules for frog oocyte growth and meiotic maturation via binding to the PUM Binding Element (PBE) on their 3′ UTR [11–13]. Recent characterization of mouse Pum homologs (Pum1 and Pum2) in sperm and oocyte development supports their conserved roles in mammalian germ cells [14–17]. However, mammalian PUM proteins appeared to have functions beyond germ cells in diverse developmental processes and were also implicated in neurological and developmental diseases [18–27]. We recently found that PUM proteins regulate mouse organ and body size [22], but the specific contribution of various cell types in organ size control is unclear. Given the conserved germ cell roles of PUM, reduced gonadal size may result from disruption of Pum1 germ cell function similar to many infertile mice [28] but remains to be demonstrated. While Xenopus PUM were demonstrated to be a critical regulator of meiotic regulator and oocyte maturation, it is less clear how PUM proteins regulate meiotic cell cycles and folliculogenesis during mammalian female reproduction [16, 29].

Mammalian folliculogenesis starts from the formation of primordial follicles, through development into primary follicles, followed by extraordinary growth of ovarian follicles from secondary follicles, preantral follicles to antral follicles, and finally culminates in ovulation during Graafian follicle stage [30, 31]. Follicles are functional units of mammalian female reproduction, consisting of oocytes in the center, surrounding somatic cells and outer layer of theca cells; mouse ovaries contain several thousand follicles in different developmental stages, taking up most part of the ovary volume and weight [30, 31]. Mouse folliculogenesis initiates around the birth when germ cell cyst breaks down, and recruits somatic cells to form primordial follicles. Primordial follicles are later recruited to grow into primary follicles and their granulosa cells initiate a phase of growth in which proliferation is very slow.

Follicle size increases dramatically during the growth, with somatic cells from only one layer of primordial follicle to multiple layers of mural granulosa cells and cumulus cells of mature follicles. While oocyte size increases by 300 folds during follicular growth, the number of surrounding granulosa cells also increase dramatically [30, 31]. Those supporting somatic cells undergoes phases of proliferation in support of the growth and development of oocyte. The first phase of somatic proliferation is a slow proliferation phase from primary follicle to preantral follicles and is independent of gonadotropin stimulation, the second phase of growth (the antral and Graafian follicles) is in response to FSH and estradiol at puberty, and the granulosa cells proliferate rapidly. During ovulatory phase, granulosa cells on Graafian follicles respond to LH and stop proliferation and undergo differentiation into corpus lutein cells [32–35]. Cell cycle regulators, transcriptional regulators and intracellular signaling have been found to be important for granulosa cell proliferation and differentiation to ensure sufficient number and proper differentiation of granulosa cells, both of which are important for female fertility [33, 35, 36]. Whether translational control participates in the regulation of those cell cycle regulator expression during folliculogenesis has not been explored.

Here, we report an unanticipated role of PUM1-mediated translational control in the somatic cells of the ovary, rather than the oocyte, in regulating mouse follicle growth and fertility. We identified a number of key cell cycle regulators as direct mRNA targets of PUM1 in granulosa cells. Loss of PUM1 led to altered expression of cell cycle regulators, including both negative regulators, Wee1 and Cdkn1b, and positive regulators, such as Ccnd2, revealing a novel role of PUM-mediated translational control of cell cycle during mammalian folliculogenesis.

Materials and methods

Animals

Animals were housed under controlled environmental conditions in the animal facility of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China, with free access to water and food. Illumination was provided between 12 am and 12 pm daily. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) of Nanjing Medical University. Wild type (WT) and Pum1−/− or Pum2−/− mice were generated by mating heterozygous Pum1+/− male and female mice as previously reported [22]. Pum1 and Pum2 mutant mice were in the mixed background of FVB, C57B6 and 129svj. Mice lacking Pum in oocytes (referred to as Gdf9-cre/+; Pum1F/F) were generated by crossing Pum1F/F females with Gdf9-cre males and male F1 offspring of the genotype Gdf9-Cre/+; Pum1F/+ were mated with Pum1F/F females. Mating tests of mutant or WT control females were set up with one or two females per WT control male with proven fertility per cage. The number of pups and litters produced by each female was recorded for 6 months. Differences in the number of pups per mouse or litters per mouse among genotypes were determined by t test.

Tamoxifen injection

The inducible double knockout of Pum1 and Pum2 (R26-ERT2-Cre; Pum1F/F; Pum2−/−) were generated via crossing Pum1F/F; Pum2−/− female mice with male mice carrying tamoxifen (TM)-inducible Cre recombinase (ERT2-cre). Tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648) was resuspended with peanut oil (Sigma, C8267) to a final concentration of 10 mg/ml and injected intraperitoneally into the 3-week-old female at a dose of 100 mg/kg body weight for five consecutive days.

Oocyte collection and culture

Approximately 21-day-old female mice in the same background were injected with 5 IU PMSG intraperitoneally. Mice were sacrificed 40–44 h after PMSG injection, and their ovaries were collected in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM, Gibco, USA) with Earle's salts, supplemented with 75 μg/ml penicillin G, 50 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, 0.23 mM pyruvate, and 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin. Cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) were harvested from the ovaries. Oocytes were cultured for 1, 2, 8, and 17 h, corresponding to GV, GVBD, MI, and MII stages, respectively. We used a medium containing 2.5 mM milrinone (Sigma-Aldrich) for oocyte culture to maintain GV arrest. The oocytes were then cultured in MEM at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 under mineral oil (Sigma, USA). After culture, oocytes were collected for immunoblot analysis. 20 oocytes per 50-μl drop were cultured in MEM medium. GVBD rates were recorded every 15 min after culturing in MEM medium. After GVBD, oocytes were recorded every 1 h to obtain polar body extrusion (PBE) rates.

Immunoblot analysis

One hundred oocytes were used for each sample. Oocytes were collected after culture and frozen in PBS (Gibco, 14,109) with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 11697498,001). Ovarian protein samples were prepared using RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM pH 7.4 Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail. The extracts were heated for 5 min at 100℃ for SDS-PAGE. Blots were incubated in 5% skim milk prior to primary antibody addition: rabbit anti-PUM1 (Abcam, ab92545; 1:750), rabbit anti-α-TUBULIN antibody (Santa Cruz, sc-8035, 1:5000), mouse anti-CCNA2 (CST, #4656P, 1:1000), rabbit anti-CCND1 (CST, #2922S, 1:1000), rabbit anti-CCND2 (CST, #3741S, 1:1000), rabbit anti-CCND3 (CST, #2936S, 1:1000), rabbit anti-CCNE2 (CST, #4132S, 1:1000), rabbit anti-CDKN1B (CST, #2552P, 1:1000), rabbit anti-CDK2 (CST, #18048 T, 1:1000), rabbit anti-E2F3 (ABclonal Tech, A8811, 1:1000), rabbit anti-CDK4 (CST, #12790P, 1:1000), mouse anti-CDK6 (CST, #3136P, 1:1000), rabbit anti-WEE1 antibody (Sangon Biotech, D162496, 1:1000), or rabbit anti-DDX4 antibody (Abcam, ab13840, 1:800). Secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG HRP (CST) incubation was followed by signal detection using ECL reagents (PerkinElmer) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Densitometry analysis of immunoblot signals detected by PUM1 and α-TUBULIN antibodies) was performed with Adobe Photoshop CS5. The bar graph reflects normalized PUM1 signal from at least three different mouse ovaries against α-TUBULIN signal.

Ovarian histological analysis, follicle counting, and TUNEL assay

For histological and morphometric studies, ovaries were collected from 3-week-old and 8-week-old Pum1−/−, Gdf9-cre/ + ; Pum1F/F and WT females. Ovaries were fixed overnight in Hartman (Sigma-Aldrich), then processed and embedded in paraffin. 5-μm sections were deparaffinized, dehydrated, and rehydrated for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry following standard protocols. Antibodies are as follows: anti-PUM1 (Abcam, ab92545), anti-BrdU (Invitrogen, 03–3940), anti-phospho-Histone H3 (Ser10) (CST, 3377), and anti-Ki-67 antibody (Abcam, ab16667). Total numbers of primordial, primary, secondary, preantral, and antral follicles were counted at intervals of five sections; only follicles with an observed nucleus were scored in each section. TUNEL analysis was performed using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit from Roche according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Follicle measurements

Paraffin sections of mouse ovary were analyzed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The area and size of the follicles were measured via NIS-Elements BR software of Nikon upright microscopy. Only antral follicles with an observed nucleus were analyzed in each section. Theca cells were used as the boundary of follicles for measuring area. The diameters of the nuclei-containing oocytes were measured across the center three times and were averaged to represent the follicular size.

Immunostaining and immunofluorescence quantification

For immunofluorescence, sections were deparaffinized and sequentially rehydrated, then processed for antigen retrieval (AR) as for IHC. After AR, sections were cooled to room temperature, then blocked (IF blocking buffer—50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton-X, 5% normal serum, 0.1% BSA) for 1 h at room temperature. The primary antibody was diluted in IF blocking buffer and added overnight at 4 °C. The following day, fluorescent-conjugated antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted in IF blocking buffer (1:200) were added for 1 h at room temperature. Hoechst 33,342 (Sigma) diluted to 10 µg/ml in PBS was added for 10 min at room temperature. For measurement of cellular immunofluorescence intensity, fluorescence signals from both WT and Pum1−/− ovaries were observed under a Zeiss LSM 800 confocal microscope. Ovarian sections were prepared for the same immunostaining procedure using the same parameters. Then ImageJ (version 1.48, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to define the region of interest, and the average fluorescence intensity was measured. Data for each region were exported into GraphPad Prism7.

BrdU incorporation

Assessment of granulosa cell proliferation by BrdU incorporation was performed following published protocols by Lin et al. (2019). Mice were pretreated with gonadotrophin (5 IU PMSG for 24 h), injected intraperitoneally with 1 μg/gm BrdU (Roche, USA), then sacrificed. A primary monoclonal anti-BrdU antibody was used at 1:100 dilution. The percentages of positive cells per follicle were determined after counterstaining with hematoxylin.

Granulosa cell collection and UV crosslinking

Ovaries from 3-week-old mice (n = 99) were harvested, and the follicles were punctured with sterile injection needles to release granulosa cells, theca cells, and oocytes. We collected the cell mixture in pre-cooled HBSS, and the oocytes were isolated by mouth pipette. Granulosa cells were the main components of the remaining mix, which was immediately UV-irradiated three times at 254 nm (400 mJ/cm2) (UVP, CL1000). The granulosa cells were then washed with cool 1X PBS, and the cell pellet was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at − 80 °C. For eCLIP, 1 ml cold lysis buffer with murine RNase inhibitor and protease inhibitor was immediately added to each frozen pellet. PUM1 eCLIP was performed as previously described by Van Nostrand et al. (2016).

RNA immunoprecipitation

Mouse ovarian (n = 5) were lysed in polysome lysis buffer (PLB, 0.5% NP40, 100 mM KCl, five mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM DTT, 100 units/mL RNase Out, 400 μM VRC, and 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail, pH 7.0) with a mechanical homogenizer and centrifuged at 20,000g for 20 min at 4 °C to remove the debris. The supernatant was pre-cleared with blocked Dynabeads (Invitrogen, 10004D) and then immunoprecipitated with antibody-conjugated or normal IgG-conjugated Dynabeads at 4 °C for at least 3 h. Next, the beads were washed four times with NT2 buffer (0.05% NP40, 50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.4) supplemented with RNase and protease inhibitor. Before the final wash, the beads were divided into two portions. A small portion was used to isolate protein for enrichment identification of target protein, and the remaining portion was resuspended in 100 μL of NT2 buffer supplemented with RNase inhibitor and 30 μg of proteinase K to release the RNA at 55 °C for 30 min. The RNA was eluted using 1 mL TRIzol (Ambion, 15,596,018).

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis

Total RNA from tissue, or fractions from the sucrose density gradient centrifugation, was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Single-stranded cDNAs were generated with the cDNA synthesis kit Prime Script RT Master Mix (Takara). The cDNAs were used for qRT-PCR performed with SYBR Green Master Mix (Q141-02, Vazyme, China). Primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table S5. Gapdh and Rpl19 were used as controls for normalization.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism7 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA). Data are shown as the mean ± SEM of the mean from at least three independent experiments. Quantitative data in different groups were compared using the Student t test. Correlations of the three biological replicates were analyzed using Spearman’s rank analysis and Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Analysis of differential expression and overall survival

Oncomine database (https://www.oncomine.org/resource/login.html) was employed to visualize the expression of human PUM1 mRNA in ovary and ovarian cancer tissues by using the boxplot. The association between PUM1 protein expression and ovarian cancer or patients’ age was analyzed using UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu). The overall survival analysis of human PUM1 mRNA and protein in ovarian cancer patients was derived from UALCAN and The Human Protein Atlas (https://www.proteinatlas.org), respectively. P < 0.05 was regarded to be statistically significant.

Results

PUM1 is predominantly expressed in somatic cells of the postnatal ovary.

We started by examining the expression patterns of PUM1 protein in mouse ovaries by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Given the well-established germ cell roles of PUM proteins in frog oocyte maturation and the recent report in mouse meiosis [11, 13, 15, 37], we were surprised to find strong expression of PUM1 proteins in somatic cells of the adult ovaries but little expression in the oocytes of the follicles (Fig. S1B). PUM1 is highly expressed in granulosa cells and theca cells throughout follicular development while oocyte PUM1 could only be detected in embryonic ovaries and at the beginning of folliculogenesis, specifically in primordial follicles (Fig. S1A, B). Such strong somatic expression is specific to PUM1 as the signal was absent in Pum1 global knockout but present in germ cell-specific knockout ovaries using either Gdf9-cre or Vasa-cre (Fig. 1A, Fig. S1C, D). We further showed that both Pum1 mRNAs and protein were not detectable in the isolated oocytes but highly expressed in the granulosa cells and cumulus cells from adult ovaries (Fig. S1E, F). The detected band similar in size to PUM1 protein in the oocytes was non-specific band (Fig. S1G, H and Supplementary Table S1). This predominant somatic expression in adult ovaries contrasts with predominant germ cell roles of ovarian PUM homologs in other species and the earlier report of PUM proteins in germ cells of mouse ovaries [15], and prompted us to examine PUM1 expression in another mammalian species-golden hamster. Similarly, PUM1 protein was also highly expressed in the somatic cells of golden hamster ovaries and not in oocytes of the growing follicles (Figure S1I). Hence, predominant somatic expression of mouse ovarian PUM1 is a novel feature of mammalian PUM family proteins, raising the question if mammalian PUM1 might regulate female reproduction through ovarian somatic cells.

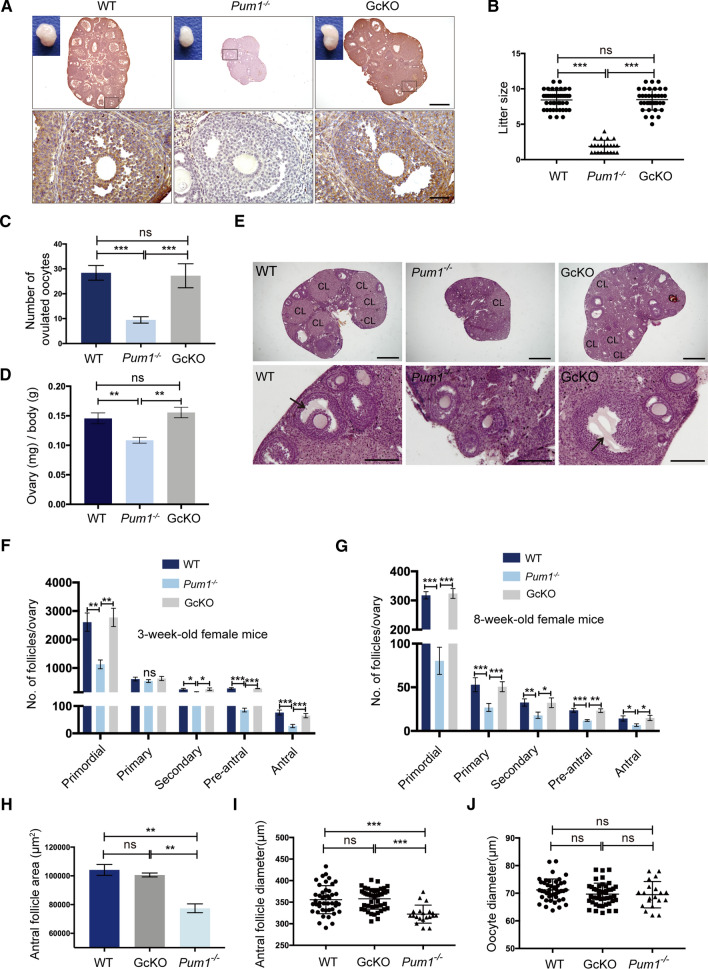

Fig. 1.

Global Pum1 knockout affected female fertility, resulting in a significant reduction in follicle number and size, in contrast, oocyte-specific Pum1 knockout with Gdf9-cre had little effect. A Widespread somatic expression of PUM1 was detected by immunohistochemistry in the wildtype ovary (WT), lost in absence of Pum1 (global Pum1 knockout) but reappeared in Gdf9-cre; Pum1F/F (GcKO) ovaries. The follicles in the black frame were magnified. Scale bars: 500 μm (upper panel) and 50 μm (lower panel). B Litter size (the number of live pups born) from the females of these three genotypes were examined and compared during a 6-month breeding experiment. Wild type (WT; n = 12), Pum1−/−(n = 7) and GcKO (n = 10). ***P < 0.001; ns, not statistically significant. C The numbrer of superovulated oocytes were measured from females of WT (n = 8), Pum1−/− (n = 7) and GcKO (n = 5) mice. ***P < 0.001. D Reduced ovary weight relative to body weight from adult Pum1−/− (n = 5) female mice when compared with WT (n = 6) or GcKO (n = 5) mice. E Representative images of ovarian sections from 8-week-old WT, Pum1−/− and GcKO mice, stained with hematoxylin/eosin (H&E). The black arrows indicated antral follicles. Scale bars: upper panel 500 μm; lower panel 100 μm. CL referes to corpus luteum. F Average number of different types of follicles in 3-week-old WT (n = 3), Pum1−/− (n = 3) and GcKO (n = 3) ovaries. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, not statistically significant. G Average number of primordial, primary, secondary, pre-antral, and antral follicles in 2-month-old WT (n = 3), Pum1−/− (n = 3) and GcKO (n = 3) ovaries. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. H Antral follicle areas were significantly reduced in Pum1-deficient ovaries. **P < 0.01. I Average antral follicular diameter from the ovaries of the three genotypes. Each value represents the average of at least three measurements. Unpaired t test was performed using GraphPad. ***P < 0.001. J Diameters of oocytes from ovaries of the three genotypes were compared. ns not statistically significant

Pum1 is required for follicle development and fertility but not for meiotic maturation

To functionally delineate contribution of somatic PUM1 versus oocyte PUM1 to female fertility, specifically to folliculogenesis and oocyte maturation, we compared the effect of global Pum1 knockout (Pum1−/−) and postnatal germ cell (oocyte)-specific Pum1 knockout (Gdf9-cre; Pum1F/F, GcKO) on female fertility and folliculogenesis. While the total litter number was not significantly different among the three groups (Fig. S2A), global deletion of Pum1 led to significantly smaller litter size (1.87 ± 0.18) compared to WT (8.43 ± 0.20) yet the litter size in the GcKO mice with oocyte-specific loss of Pum1 was not reduced (8.47 ± 0.25) (Fig. 1B). These results suggest that somatic Pum1 rather than oocyte Pum1 in the postnatal females is responsible for fertility reduction in Pum1 global knockout mice.

To determine if defects in ovulation and/or folliculogenesis might contribute to the reduced fertility in Pum1−/− mice, we first compared the number of MII oocytes from superovulated 3-week-old female mice among the three genotypes. The number of MII oocytes harvested from WT and GcKO mice was 28.4 ± 1.3 and 27.2 ± 2.2, respectively, while only 9.5 ± 0.6 oocytes were recovered from Pum1−/− mice (P < 0.001, Fig. 1C). Consistent with reduced ovulation, the number of corpora lutea in 3-week-old Pum1−/− mice was also reduced (Fig. S2B). We next compared the follicle development in both 3-week-old and 8-week-old mice of all three genotypes. The overall morphology of ovarian follicles appeared normal in Pum1−/− ovaries (Fig. 1E, S2C), but Pum1−/− ovaries were smaller in size and weight than those of WT or GcKO mice (Fig. 1A, D, E), with a significantly reduced number of growing follicles (Fig. 1F, G). We detected a significant reduction not only in the number of primordial follicles in Pum1−/− females when compared to WT (Fig. 1F, G), as reported previously [15], but also in the number of secondary, pre-antral and antral follicles (Fig. 1F, G). The number of primary follicles in 3-week-old ovaries was not very different among the three groups (Fig. 1F), but was lower in 8-week-old Pum1−/− mice compared to WT and GcKO mice (Fig. 1G). The number of primordial, primary, secondary, pre-antral and antral follicles in GcKO mice, in contrast, was not different from those of WT ovaries (Fig. 1F, G) [15], further supporting a somatic function for PUM1 during follicle growth and development.

In addition, the area and diameter of antral follicle were also significantly lower in Pum1−/− ovaries than those of WT and GcKO ovaries, though oocyte size was not significantly different (Fig. 1H–J and S2D). Taken together, global Pum1 deletion led to a reduction in the number of secondary, preantral, and antral follicles as well as in antral follicle size. At the same time, postnatal loss of oocyte Pum1 in growing follicles did not impact follicle number or size, or fertility. Our findings uncovered a novel somatic role of PUM1 in mammalian folliculogenesis, and dispensability of postnatal oocyte Pum1 in mice.

Given that Pumilio (Pum) is involved in Xenopus oocyte maturation [11–13], we next examined whether Pum1 loss affects oocyte meiotic maturation by measuring germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) and polar body extrusion (PBE). GV stage oocytes released from ovaries in culture were synchronized to allow resumption of meiosis and the first polar body's extrusion in vitro. Most of the oocytes from WT, GcKO, and Pum1−/− females underwent GVBD within 2 h, with no difference among the groups (Fig. S2E). The time to first PBE for Pum1−/− and GcKO females were also indistinguishable from WT female mice (Fig. S2F). Hallmark meiotic events such as spindle assembly and chromosome alignment at metaphase I and II (MII) also appeared unaffected in Pum1−/− and GcKO females (Fig. S2G–I). Hence, PUM1 is dispensable for oocyte meiotic resumption and maturation in mice.

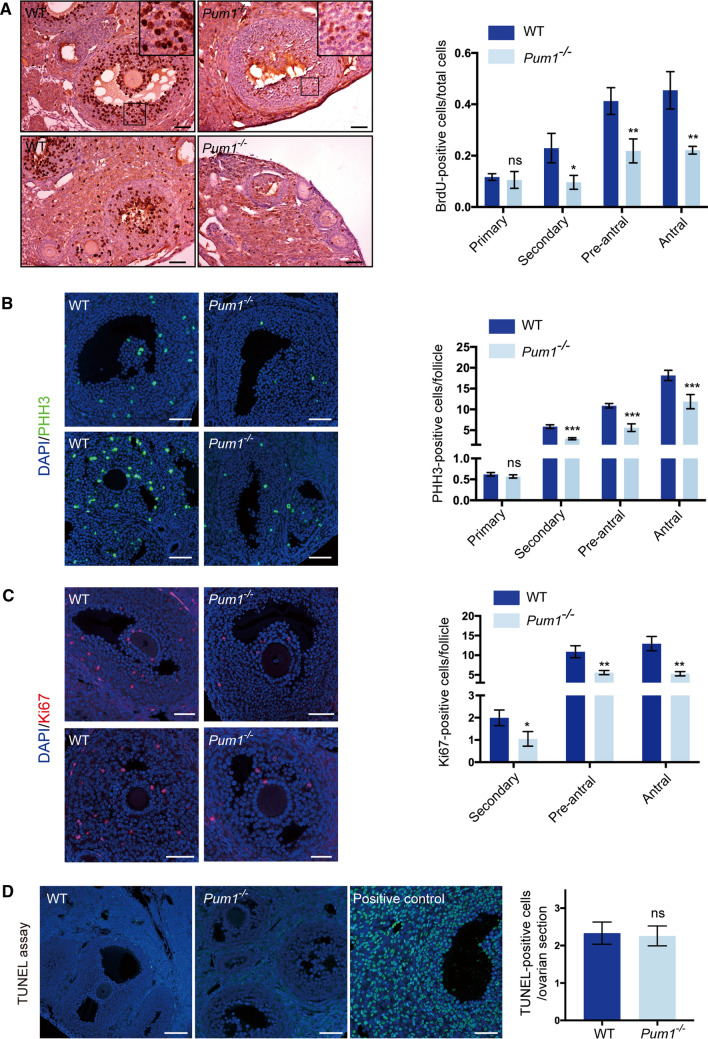

Pum1 mutant follicles exhibit reduced granulosa cell proliferation

Given that Pum1−/− ovaries exhibited a reduction in the number and size of developing follicles and PUM1 is highly expressed in granulosa cells throughout folliculogenesis, we asked if granulosa cell proliferation or apoptosis are affected by the loss of Pum1. Loss of PUM1 protein resulted in significantly reduced bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation (a marker of active DNA replication) in secondary, pre-antral, and antral follicles (Fig. 2A) but not in primary follicles. We also observed a reduction in the number of phospho-histone 3 (PHH3) positive, actively dividing cells in secondary, pre-antral, and antral follicles, and Ki67 positive cells in secondary, pre-antral, and antral follicles of Pum1−/− ovaries (Fig. 2B, C). BrdU and PHH3 positivity in primary follicles were not significantly different between WT and Pum1−/− females, while too few ki67 positive cells were detected in primary follicles of either genotype for comparison (Fig. 2C). TUNEL assay of WT and Pum1−/− ovaries showed no difference in the number of apoptotic cells (Fig. 2D). Thus, reduced proliferation but not increased apoptosis of granulosa cells during follicle development appeared to underlie the abnormal folliculogenesis observed in Pum1−/− mice.

Fig. 2.

Granulosa cell proliferation was significantly reduced in Pum1-null ovaries. A Proliferation of follicular granulosa cells was assessed by BrdU labeling. Ovarian sections from 2-month-old wild type (WT; n = 3) and Pum1−/− (n = 3) mice are shown on the left. The scale bar is 50 μm for all images. Quantification of BrdU-positive cells in different stages of follicles between WT and mutant ovaries is shown in the graph. Data are the mean ± SEM of three mice. **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. B Immunofluorescence staining for Phospho-H3 (PPH3) in the ovaries of WT and Pum1−/− mice. Quantification of PPH3-positive nuclei in the primary, secondary, pre-antral, and antral follicles of WT (n = 4) and Pum1−/− (n = 4) mice. ***P < 0.001; ns, not statistically significant. C Immunofluorescence analysis of Ki67 (red) and DAPI (blue) in adult WT and Pum1−/− ovarian sections and the merged images. Scale bars in all images are 50 μm. The number of Ki67-positive granulosa cells is significantly reduced in secondary and antral follicles of mutant ovaries. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. D Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TDT)-mediated dUTP-biotin nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining assay showed apoptotic cells in WT (n = 3) and Pum1−/− (n = 3) ovaries marked by green staining. DAPI was used to visualize DNA (blue). Apoptotic cells induced with DNase I treatment were used as positive controls. Scale bar: 100 μm. The number of apoptotic cells was not significantly different between WT and Pum1−/− ovaries. Data are presented as mean ± SEM

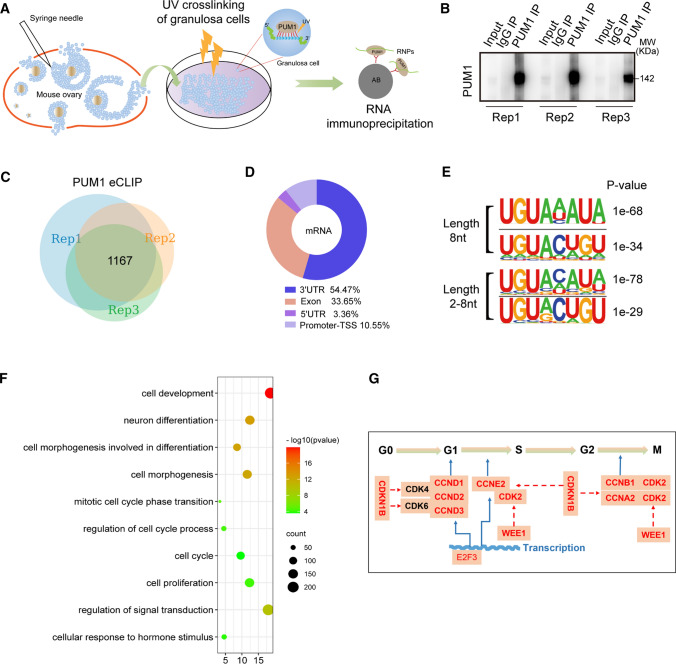

PUM1 binds to mRNA transcripts of cell cycle regulators in granulosa cells

Given that PUM1 is highly expressed in somatic cells, mainly granulosa cells, of the ovary and that Pum1 knockout caused reduced folliculogenesis and ovulation, we hypothesized that granulosa cell PUM1 regulates folliculogenesis by binding to mRNAs whose protein expression is critical for folliculogenesis. To dissect the molecular mechanism by which PUM1 regulate folliculogenesis, we performed enhanced UV crosslinking immunoprecipitation (eCLIP) of PUM1 ribonucleoprotein complexes in granulosa cells [38] to identify the mRNA targets of PUM1. We isolated somatic ovarian cells, mainly granulosa cells from the ovarian follicles instead of the entire ovaries to avoid potential contribution from residual oocyte PUM1 protein (Fig. 3A). A total of 99 mice were used for three biological replicates; granulosa cells from each group (33 WT mice) were pooled for eCLIP experiments. RNAs excised from three PUM1 IP lanes and the corresponding region of the input lane were used to construct PUM1 eCLIP libraries and PUM1 input library, respectively (Fig. 3B). The eCLIP sequencing results from the three replicates and the input libraries were evaluated for reproducibility (Fig. S3 and Supplementary Tables S2, S3) [38, 39]. Comparison of average peak height (Fig. S3A) and peak number (Fig. S3B), from the three biological replicates, indicated high reproducibility, with correlation coefficency r values higher than 0.79 for peak heights and 0.93 or higher for peak number between replicates (Fig. S3A, S3B). Furthermore, pairwise comparisons of normalized binding frequencies on the 3′ UTR of common targets among all three replicates by Spearman correlation analysis resulted in rho values between 0.9 and 1.0, indicating high reproducibility among the three eCLIP experiments (Fig. S3C).

Fig. 3.

Identification of PUM1 targets in murine granulosa cells by eCLIP. A Schematic illustration of the strategy used to identify PUM 1 targets by ultraviolet (UV) crosslinking of mouse ovarian granulosa cells and immunoprecipitation of PUM1-RNA complexes. B Immunoblot of three independent eCLIP experiments with mouse ovarian granulosa cells, showing immunoprecipitated PUM1 significantly enriched over input and IgG IP lanes. C Venn diagram of overlapping PUM1 eCLIP genes from three biological replicates revealed 1167 shared target genes. D Distribution of PUM1 eCLIP peaks showed PUM1 eCLIP peaks mightly enriched on the 3′ UTR of target mRNA. E Most significantly enriched binding motifs for PUM1 eCLIP data at a length of 8nt or 2-8nt identified by the HOMER algorithm. F PUM1 target genes were enriched for cell proliferation/growth/differentiation pathways (DAVID). G Cell cycle regulators for G1-S-G2-M transitions are highly enriched among ovarian granulosa cell PUM1 targets. The cell cycle genes identified in the DAVID pathway of H was marked by red font.

We identified 1167 common targets among all three replicates with at least two-fold enrichment over input in eCLIP peaks and these common targets were used for all the downstream analysis (Fig. 3C). Upon mapping the peaks from the 1167 shared targets, we found that more than half of PUM1 peaks were located in the 3′ UTR, consistent with its role in posttranscriptional regulation (Fig. 3D). We then utilized a motif discovery algorithm, Hypergeometric Optimization of Motif EnRichment (HOMER), to examine the consensus sequence of PUM1 binding sites. Among the most enriched 8nt motifs or 2-8nt motifs, UGUANAUA (N represents A/C/U) was ranked highest in all three replicates respectively, (Fig. 3E). This motif was identical to the canonical PUM proteins’ conserved binding motif as previously reported [9, 27, 40], supporting the high quality of these eCLIP experiments. Previously reported PUM1 targets, such as Pum2 and the long noncoding RNA Norad, indeed contain highly enriched reproducible peaks among three replicates, while Lin28a, a non-target of PUM, does not [22, 41] (Fig. S3D). We also validated our eCLIP results by RIP-qPCR (RNA Immunoprecipitation) of selected targets (Fig. S3E).

We next performed gene ontology (GO) analysis on the 1167 PUM1 targets. Granulosa cells were known to undergo extensive cell proliferation and differentiation to support follicular development. Remarkably, pathways in cell proliferation, the mitotic cell cycle phase transition, cell cycle and cell proliferation, are among the significantly enriched pathways, consistent with the proliferation defects we observed in Pum1−/− granulosa cells (Fig. 3F). Also, PUM1 targets in ovarian granulosa cells were significantly enriched for cellular response to hormone stimulus pathway, suggesting PUM1 may also regulate hormone-regulated differentiation of granulosa cells. We focused on the mechanisms by which PUM1 regulates granulosa cell proliferation in the current study.

Our previous work showed that PUM protein regulates organ and body size via translational repression of Cdkn1b, but it is not known how different type of cells within an organ contribute to organ size regulation and if PUM coordinates regulation of positive and negative of cell cycle regulators. We hence focused on PUM1 targets from cell cycle phase transition pathway and found that besides CDKN1B, a number of other key regulators of cell cycle phase transition were also bound by PUM1 (Fig. 3G). As matter of fact, most of the key regulators of cell phase transition from G1-S-G2-M, including both positive and negative regulators, were bound by PUM1, prompting us to investigate if PUM1 promotes cell cycle phase transition through co-ordinated regulation of key regulators of cell phase transition at posttranscriptional level.

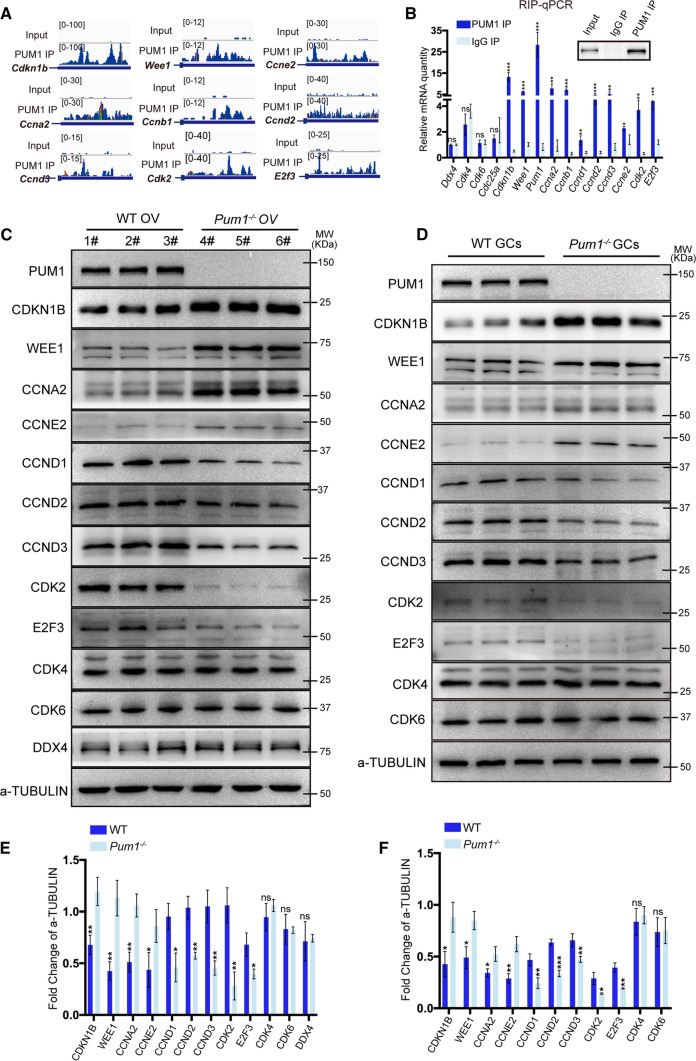

PUM1 is essential for integrated translational regulation of cell cycle regulators in ovarian granulosa cells

We next determined how the loss of Pum1 impacted the expression of those cell proliferation targets in the ovary and granulosa cells. Our study found that the proliferation of granulosa cells in Pum1−/− ovaries were significantly reduced, contributing to the reduced number and size of growing follicles and reduced fertility. Critical components of the cell cycle machinery responsible for cell cycle progression in eukaryotes, were enriched in the list of PUM1 cell cycle targets. As shown in Figs. 4A and S3F, these cell cycle-related genes showed significant peak enrichment on their 3′ UTRs relative to input. To validate those cell cycle targets, we first performed PUM1 granulosa cells RIP-qPCR on the cell cycle targets and found that those cell cycle mRNAs were indeed significantly enriched relative to IgG control (e.g., Cdkn1b, Wee1, Ccna2, Ccnb1, Ccne2, Ccnd1, Ccnd2, Ccnd3, Cdk2, and E2f3) (Fig. 4B). We termed these targets the PUM1-Bound Cell Cycle Regulators (PCCR), representing major cell cycle genes coordinately regulated by PUM1 [3]. The known PUM binding motif (PUMILIO Binding Element, PBE) was enriched on the 3′ UTRs of PPCR mRNAs, with a significant portion (37.5%) containing at least one PBE (Fig. S3G–H). Out of 48 PCCR genes, five genes (Ccnb1, Cdkn1b, Wee1, Ccne2, Ccny) contained two PBEs (Fig. S3H).

Fig. 4.

PUM1 binds the 3′ UTR of mRNAs coding for cell cycle regulatory proteins (PCCR), whose protein levels were significantly altered in absence of Pum1. A IGV genome tracks showing PUM1 binding peak distributions on the 3′ UTR of cell cycle-associated PCCR genes. B Validation of PUM1-bound transcripts by RIP-qPCR. Error bars indicate SD. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05. C Immunoblot analysis of selected PCCR targets expression in Pum1−/− ovaries. 1#-6# represents different mice. OV, ovary. D Cell cycle-associated PCCR proteins expression was examined in Pum1−/− granulosa cells. GCs, granulosa cells. Relative protein expression in wild type (WT) and Pum1−/− ovaries E or granulosa cells F by densitometric analysis of immunoblot. Three biological samples were analyzed, and the data were presented as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, not statistically significant

We next determined the effect of loss of PUM1 on the PCCR expression and proliferation of granulosa cells. Two PCCR genes, Cdkn1b and Wee1, containing unique PUM1 binding peaks on their 3′ UTR (Fig. 4A), are known to negatively regulate the cell cycle by inhibiting the activity of CDKs. CDKN1B is bound to the cyclin–CDK complex, resulting in a conformational change [42]. Cdkn1b was reported to be regulated by PUM in the testis and fibroblast cells, but its role in the ovary and granulosa cells has not been examined [22]. WEE1 is best known for its role in the direct phosphorylation and inhibition of CDK1 and CDK2 during the G2/M transition [43]. Immunoblot analysis showed that expression of CDKN1B and WEE1 was increased in both Pum1−/− ovaries (Fig. 4C, E) and Pum1−/− granulosa cells (Fig. 4D, F) in comparison to WT. Such an increase in protein levels of cell cycle inhibitor CDKN1B and WEE1 were expected to slow the cell cycle progression, hence contributing to reduce proliferation in granulosa cells. Transcript levels of Cdkn1b and Wee1 were not significantly different between Pum1−/− and WT (Fig. S4C), supporting regulation at the posttranscriptional level. Consistently, we also found that the overall CDKN1B immunofluorescence intensity appeared also higher in Pum1−/− granulosa cells than those in WT (Fig. S4A).

There are four major classes of cyclins, G1-cyclin, G1/S-cyclin, S-cyclin, and M-cyclin [44]. Four cyclins were identified as targets of PUM1 by eCLIP (Fig. 4A, B): Ccnd and Ccne2 are G1-cyclins, Ccna2 is an S-cyclin, and Ccnb1 is an M-cyclin. Cyclical synthesis and degradation of cyclin proteins result in the cyclic assembly and activation of the cyclin-Cdk complexes that drive cell cycle progression. Protein levels of CCNA2 and CCNE2 were significantly higher in both Pum1−/− ovaries and granulosa cells compared to WT (Fig. 4C–F), while CCND1, CCND2, and CCND3 protein levels were lower in Pum1−/− ovaries and granulosa cells compared to WT (Fig. 4C–F). The mRNA levels of these ovarian cyclins were not significantly different between Pum1−/− and WT (Fig. S4C). Protein expression of CCND2, a previously identified regulator of granulosa cell proliferation [35], was significantly lower in Pum1−/− granulosa cells (Fig. S4B). These findings suggest that PUM1 regulates the protein levels of these cell cycle mRNA targets to modulate cell cycle progression at multiple transition points.

Cdk2 and E2f3 mRNA were also enriched in the PUM1 eCLIP, with CDK2 and E2F3 protein levels, but not mRNA levels, significantly lower in Pum1−/− ovaries and granulosa cells compared to WT (Figs. 4C, D; S4C). Two cell cycle regulators, Cdk4 and Cdk6, were not enriched in the PUM1 eCLIP nor in PUM1 RIP (Figs. 4B and S3I), and immunoblot confirmed that CDK4 and CDK6 protein expression were not significantly different between Pum1−/− and WT ovaries and granulosa cells (Fig. 4C, D). Given that PUM1 protein is not present in postnatal oocytes of growing follicles, germ cell-specific Ddx4 was used as negative control for RIP and western blot (Fig. 4B, C) for the specificity of PUM1 binding to PCCR genes and expression change of PCCR proteins in the absence of Pum1. Together, our results established that PUM1 regulates cell cycle progression in granulosa cells via binding to a network of mRNA transcripts, important for cell cycle progression and differentiation.

Postnatal knockdown of Pum1 confirms its roles in granulosa cell proliferation via translational control of PUM1 cell cycle targets

While our data support that PUM1-mediated posttranscriptional regulation in granulosa cells contributes to folliculogenesis and normal fertility, it is also possible that the developmental loss of Pum1, as well as the potential compensatory effect of Pum2, the other member of PUM family, in the absence of Pum1, may contribute to the observed folliculogenesis and fertility defect in the global Pum1 knockout. Although Pum2 is dispensable for female fertility with two reported different mutant alleles [17, 45], it is not known to what extent PUM1 and PUM2 overlap in their ovarian function to regulate folliculogenesis.

To study Pum family genes’ postnatal ovarian function, we constructed an inducible Pum1 and Pum2 double knockout model using R26-CreERT2; Pum1F/F; Pum2−/− females with tamoxifen-induced inactivation of Pum1. Three-week-old female mice were intraperitoneally injected with tamoxifen (Cre-ERT2Tam; Pum1F/F; Pum2−/−) or peanut oil (Cre-ERT2Oil; Pum1F/F; Pum2−/−) for five consecutive days and sacrificed 48 h after PMSG injection (Fig. S5A).

Histological analyses of tamoxifen-induced double knockout ovaries showed severe defects in follicle maturation. Tamoxifen-inducible ovaries were significantly smaller and had fewer antral follicles than controls (Fig. 5A, B). As expected, the number of primordial follicles was not significantly different in the tamoxifen-treated or control ovaries, and there was no effect on primary follicles (Fig. 5B). Reduced Pum1 expression led to increased number of secondary and pre-antral follicles relative to the control group (Fig. 5B); thus, the reduction of PUM1 protein in Pum2−/− ovaries impeded follicle development and caused an accumulation of secondary and pre-antral follicles. Besides, significantly fewer MII oocytes were ovulated from tamoxifen-treated females following HCG injection (Fig. 5C). The oviductal ampulla region of control mice was also more prominent than that in tamoxifen-treated females after gonadotropin stimulation (Fig. S5D), consistent with reduced superovulation in the tamoxifen-induced double knockout ovaries. The efficiency of tamoxifen-induced Pum1 knockout was evaluated at Pum1 genomic DNA, RNA, and protein levels (Figs. 5F, G; S5B), with more than 50% reduction in PUM1 protein level (Figs. 5G; S5C, G).

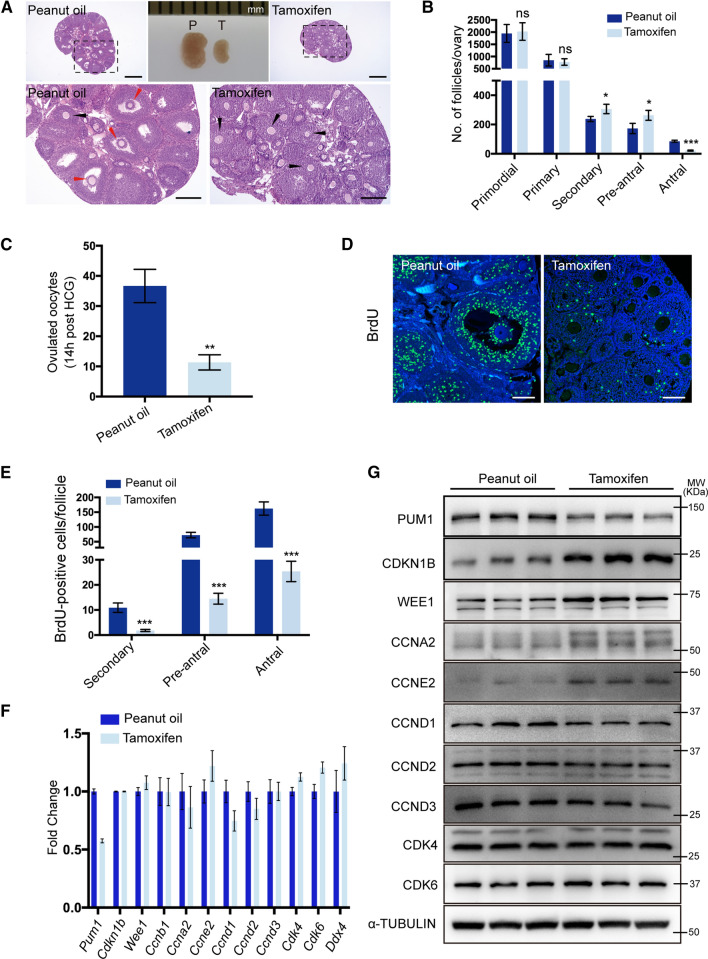

Fig. 5.

Tamoxifen-induced Pum1 knockout in the background of Pum2−/− mice resulted in follicle maturation defects. A Hematoxylin and eosin-stained ovarian sections showed that ovaries of tamoxifen-treated mice contained few antral follicles. Peanut oil-treated littermates of the same genotype (Ert2-cre/ + ; Pum1F/F; Pum2−/−) were used as controls. White arrow, secondary follicle; Black arrow, pre-antral follicle; Red arrow, antral follicle. Scale bar: 500 μm (upper panel); 200 μm (lower panel). B Quantitative analysis of primordial follicles, primary follicles, secondary follicles, pre-antral follicles, and antral follicles at three weeks of age. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with peanut oil or tamoxifen for five consecutive days (n = 3 for each group, data are mean ± SEM). ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, not statistically significant. C Number of ovulated oocytes from Ert2-cre/ + ; Pum1F/F; Pum2−/− female mice treated with peanut oil (n = 3) or tamoxifen (n = 3). Oocytes were collected at 14 h after HCG. D Representative images of ovarian granulosa cell proliferation assay using BrdU labeling after peanut oil or tamoxifen induction. The incorporated BrdU was stained with an anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (green), DAPI was applied as a nuclear counterstain (blue). Scale bar, 100 μm. E Quantification of BrdU-positive cells in secondary follicles, pre-antral follicles, and antral follicles, respectively. Each group consisted of three mice, and three discontinuous ovarian sections were analyzed for each Ert2-cre mouse. ***P < 0.001. F RT-qPCR analysis of mRNA expression of various cell cycle factors after intraperitoneal injection of peanut oil or tamoxifen. G Immunoblot analysis of PCCR protein expression in Ert2-cre/ + ; Pum1F/F; Pum2−/− female ovaries after treatment with tamoxifen or peanut oil

We further assessed BrdU incorporation in the ovaries of 3-week-old female Cre-ERT2; Pum1F/F; Pum2−/− mice (Fig. 5D). The number of BrdU-positive granulosa cells was significantly reduced in secondary, pre-antral, and antral follicles in the tamoxifen-treated mice compared to controls (Fig. 5E). The number of PHH3-positive granulosa cells was similarly decreased in tamoxifen-treated mouse ovaries compared to controls (Fig. S5E, F). TUNEL assay showed no significant difference in the number of apoptotic granulosa cells in the ovaries of tamoxifen- and control-treated mice (data not shown).

To evaluate the potential effect of tamoxifen injection on folliculogenesis, we performed a control experiment on Pum1F/F; Pum2−/− mice treated with tamoxifen or oil. Other than a slight reduction in ovary weight and the number of preantral follicles, there was no significant difference in the number of different follicle types or in granulosa cell proliferation between tamoxifen-treated and control Pum1F/F; Pum2−/− mice (Fig. S6). Together, these findings supported that Pum1 knockdown in Pum2−/− mice significantly reduced granulosa cell proliferation, folliculogenesis, and fertility and that ovarian somatic PUM1 plays a significant role in female fertility.

Furthermore, we observed protein expression changes in PCCR genes in induced Pum1 and Pum2 double mutant ovaries and granulosa cells, consistent with those in Pum1−/− ovaries and granulosa cells. CDKN1B and WEE1 protein levels were increased, and the other positive cell cycle regulators of PCCR genes were decreased in tamoxifen-treated Cre-ERT2; Pum1F/F; Pum2−/− ovaries compared with control ovaries (Fig. 5G, Fig. S5G). The mRNA levels of the PCCR genes were also not significantly affected after tamoxifen treatment of Cre-ERT2; Pum1F/F; Pum2−/− mice (Fig. 5F).

Loss of both Pum1 and Pum2 in postnatal oocytes does not affect meiotic maturation, folliculogenesis, or fertility

While inducible knockdown of Pum1 in Pum2-null mice supports our hypothesis that PUM1 acts in granulosa cells to control folliculogenesis, we have not ruled out the possibility that PUM2 might compensate for PUM1 in oocytes in the global knockout of Pum1, making oocyte Pum1 dispensable for fertility. We hence generated oocyte-specific Pum1 knockout mice on a Pum2−/− background (Gdf9-cre/ + ; Pum1F/F; Pum2−/−, GDKO). Similar to the oocyte-specific Pum1 knockout (GcKO), postnatal loss of both Pum1 and Pum2 in GDKO oocytes during folliculogenesis did not lead to any detectable defects in female fertility, ovarian morphology, ovulation, follicle number, or oocyte meiotic maturation (Fig. S7), consistent with little oocyte PUM expression in postnatal growing follicles.

Taken together, postnatal deletion of Pum1 caused reduced granulosa cell proliferation and folliculogenesis, while oocyte-specific deletion of Pum1 and/or Pum2 had little effect. These findings support our hypothesis that mammalian PUM proteins control folliculogenesis and ovarian size through their action in ovarian somatic cells, where they modulate the translation of a network of cell cycle regulator mRNAs (PCCR).

PUM1-mediated translational control of PCCR network in ovarian cancer

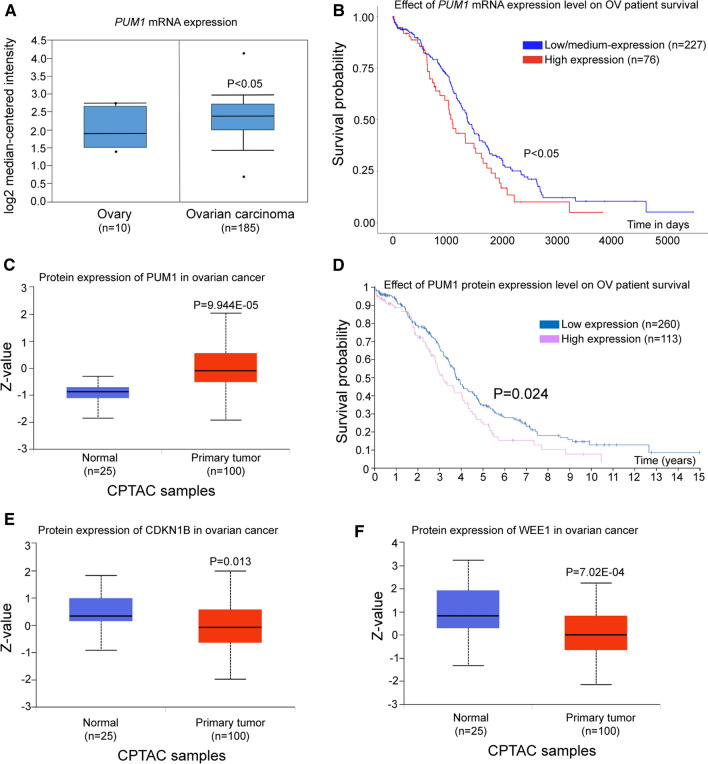

Given that ovarian somatic cells contribute to majority of ovarian cancer and are responsible for most ovarian cancer-related death, we asked if PUM1-mediated translational regulation of PCCR genes might be present in human ovary, specifically if human PUM1 may play a role in the progression of ovarian cancer through its conserved roles in promoting granulosa cell proliferation. We found that the expression level of PUM1 mRNA was significantly upregulated in ovarian tumor tissues compared with normal ovary (P < 0.05, Fig. 6A). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis with the log-rank test for overall survival from UALCAN was used to evaluate the relationship between PUM1 transcript expression and patient prognosis (P < 0.05; Fig. 6B), and the analysis revealed ovarian cancer patients with high levels of PUM1 (n = 76) exhibited shorter overall survival time than patients with low and medium levels of PUM1 (n = 227). Consistent with the mRNA expression, data from CPTAC showed that PUM1 protein expression were also significantly increased in ovarian cancer compared to normal tissues (P = 9.944E−05; Fig. 6C). Moreover, ovarian cancer patients with high PUM1 protein (n = 113) expression displayed shorter overall survival compared with low PUM1 expression (n = 260) in the Human Protein Atlas database (P = 0.024; Fig. 6D). These TCGA and CPTAC data indicated PUM1 mRNA and protein were increased in ovarian cancer, and its high expression was correlated with poor prognosis. We further explored whether PCCR proteins expression were changed accordingly in ovarian cancer, indeed CDKN1B and WEE1 protein were significantly downregulated in ovarian cancer cohort where PUM1 protein was upregulated (Fig. 6E, F), supporting that PUM1-mediated translational control of PCCR network plays a conserved role in human ovarian cell proliferation and contributed to cancer progression [46]. In summary, PUM1 overexpression and belated PCCR gene network expression change were significantly associated with progression and poor prognosis of human ovarian cancer, and PUM1–PCCR network should be further investigated for their potentials as prognostic biomarkers as well as therapeutic targets for ovarian cancer.

Fig. 6.

PUM1-mediated translational control of cell cycle genes contributed to ovarian cancer progression and prognosis. A Oncomine database analysis of the expression of PUM1 mRNA in normal ovary tissue and ovarian carcinoma tissue. The P value was shown. B Overall survival curves with low-medium or high expression of PUM1 transcripts were analyzed of 303 ovarian cancer patients (The Kaplan–Meier survival plot from UALCAN using TCGA ovarian cancer data set). C Human PUM1 protein expression in ovarian cancer compared with normal controls from CPTAC (Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium) based on UALCAN database. The P valued was shown. D Survival curve based on the expression of PUM1 protein in ovarian cancer patients from the Human Protein Atlas web-portal (log-rank test P value = 0.024). E CDKN1B and F WEE1 protein expression was significantly down-regulated in ovarian cancer in compared to normal tissues from the CPTAC database

Discussion

Understanding the dynamic bases of protein expression change in cell cycle regulation is crucial in both normal and pathological conditions, while progress has been made in yeast and human cell lines studies, it remains a challenge to dissect how translational control contributes to organ growth and organogenesis due to complexity of different cell types and timing of proliferation. Here, we report a translational control mechanism in somatic supporting cells that regulates ovarian folliculogenesis, female fertility in mice and contributes to ovarian cancer progression. We demonstrated a previously unappreciated role of the RNA-binding protein PUM1 in granulosa cells, but not the oocyte, regulating granulosa cell proliferation, folliculogenesis, and fertility. The predominant expression of PUM1 in mammalian ovarian granulosa cells, absence of PUM1 protein in the oocytes of growing follicles, and normal fertility in the absence of oocyte PUM1 and PUM2 support a model in which mouse PUM1 predominantly acts to regulate folliculogenesis not through oocytes but via somatic granulosa cells. We found that PUM1 protein binds to PBE motifs in the 3′ UTR of many transcripts in granulosa cells, including genes involved in negative and positive regulation of the cell cycle. Knockout of Pum1 led to decreases in protein expression of positive cell cycle regulators and increases in protein expression of negative cell cycle regulators, arguing that PUM1 regulates folliculogenesis and female fertility via integrated translational control of cell cycle regulators essential for granulosa cell proliferation.

PUM1 belongs to a conserved RNA-binding protein family, the PUF (PUMILIO/FBF) family, which are critical translational regulators in germ cell development in diverse species [9, 11, 47–51]. Recent studies of mouse PUM family proteins, Pum1 and Pum2, showed that PUM1 regulates both male and female germline development while Pum2 appears to be dispensable for both male and female germ cell development and fertility [11, 14–17, 22, 23, 52]. PUM proteins have been shown to function as critical translational regulators in Xenopus oocyte development, and meiotic maturation [11–13], and mouse Pum1 knockout also affects the primordial follicle pool, meiosis, and reproductive competency [15, 16]. Highly conserved roles of PUM homologs in the reproduction of both invertebrates and vertebrates and demonstration of PUM protein as a translational regulator of meiotic maturation in frog suggested that PUM may function similarly in mouse germ cells. However, the reported roles of mouse PUM1 and PUM2 outside gonads make it imperative to consider contribution of somatic cells to gonadal size and function [22–24, 27]. To our surprise, PUM1 was predominantly expressed in the somatic cells of the mouse ovary but undetectable in oocytes after the primordial follicle stage. Loss of postnatal Pum1 or both Pum1 and Pum2 specifically in the oocytes did not affect female fertility or folliculogenesis [15]. That oocyte PUM does not appear required for postnatal folliculogenesis lends strong support to a role for somatic cell PUM in folliculogenesis and female fertility.

In the oocyte, transcription is silenced from the late GV stage until embryonic genome activation (EGA) upon fertilization. Meanwhile, several specialized RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) induce translational activation of maternal mRNAs required for oocyte maturation [29, 53]. The widely studied model organism for oocyte translational regulation of meiosis is Xenopus, where many RBPs are involved in translational control. Pumilio1 (Pum1) specifically regulates the translation of cyclin B1 mRNA during Xenopus oocyte maturation, in cooperation with cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein (CPEB). Pumilio2 (Pum2) represses RINGO/Spy mRNA translation through interacting with DAZL in Xenopus oocytes [12, 29, 53, 54]. Mammalian orthologues of several RNA binding proteins important for oocyte maturation in frogs have been reported to play conserved roles in mice [53, 55]. Thus, it was surprising to find that PUM proteins were not essential for mouse oocyte meiotic resumption and maturation, suggesting the oocyte function of PUM1 is not conserved in mammals.

While our observed reduction in primordial follicles in the Pum1 knockout mouse is consistent with the previously reported phenotype of a Pum1 mutant [15], we uncovered a novel follicular growth defect in secondary and preantral follicles. This difference in the severity of the folliculogenesis defect between these two mice and Pum1's role predominantly in somatic cells rather than oocytes from our study could be related to the different Pum1 knockout alleles used besides potential background difference. Our Pum1 knockout mice are missing exon 9 and exon 10 of Pum1, leading to a prematurely terminated peptide without the highly conserved RNA binding domain through a frame-shift mutation [22]. The Pum1 knockout mutation described by Mak et al. deleted exons 8, 9, and 10 [14, 15], and the resulting mutant transcript could still code for a partially functional protein with key important domains undisrupted.

The presence of a protein band similar in size to PUM1 in WT oocytes and Pum1 knockout oocytes raised the possibility of an alternatively spliced but functional oocyte-specific isoform of PUM1 that escaped our knockout strategy. Several lines of evidence argue against this scenario. First, oocyte PUM1 expression was very low and undetectable by immunohistochemistry of ovary sections (Fig. S1). Second, an oocyte-specific isoform of PUM1 that skips exon 9 and 10 is inconsistent with the lack of Pum1 transcripts in Pum1 knockout oocytes by RT-qPCR (Fig. S2J). Our IP mass spec analysis of the oocyte band confirmed the nature of such a non-specific protein band (Fig. S1G and Supplementary Table S1). Thus, our data support an absence of PUM1 expression in oocytes in growing follicles after the primordial follicle stage. Our genetic experiments specifically removing PUM1 from the oocyte using either Vasa-Cre (active in oocytes from embryonic day 15.5) or GDF9-Cre (primordial oocytes) in a WT or Pum2 knockout background showed that there was no significant effect on folliculogenesis or fertility, demonstrating the dispensability of mouse PUM gene family in the postnatal oocytes for female fertility.

Granulosa cell proliferation and function are regulated by hormones during folliculogenesis and are necessary for ovarian follicle development, maturation, and atresia [34, 35, 58, 59]. However, the mechanism underlying granulosa cell proliferation is not fully understood. We uncovered a PUM-mediated posttranscriptional mechanism that regulates the proliferation of granulosa cells by binding to a network of mRNAs involved in the cell cycle. The decreased proliferation of granulosa cells in Pum1−/− mice likely accounts for the defect in follicle development. We found the total number of growing and mature follicles was decreased at prepuberty and to a significant extent in adult Pum1−/− mice compared to WT mice. While we could not exclude the possibility that systemic influence such as hormone regulation impacted by Pum1 knockout mutation contributed to the fertility reduction, we would like to argue that Pum1 loss in ovarian somatic cells, especially granulosa cells are mainly responsible for the reduced ovulation and fertility of Pum1 mutant mice. Our inducible Pum1 knockout experiment showed postnatal reduction of Pum1 expression at 3-wk-old mice led to similar reduction in follicular growth and in granulosa cell proliferation, hence excluding the contribution of possible systemic hormonal regulatory defect resulting from developmental defect in global Pum1 knockout. Remarkably, loss of Pum1 also caused a distinct reduction of antral follicle numbers, even with the same number of primary follicles in WT and Pum1−/− females.

Consistent with a role for somatic cell PUM1 in the ovary, Pum1 KO exhibited a defect in granulosa cell proliferation and the number of granulosa cells, resulting in reduced antral follicle size. Somatic gonadal cells play a crucial role in embryonic gonadal development and sex determination [56, 57]. We found that somatic gonadal cells also play a key role in postnatal gonadal development and gonadal size with this work.

While PUM proteins are known for their conserved roles in reproduction and are hypothesized to regulate the expression of many mRNAs at posttranscriptional level [3], details of those networks of mRNAs remain uncharacterized in mammalian tissues or organs. Prompted by a predominantly somatic expression of PUM1 and significantly reduced granulosa cell proliferation and follicle number and size in the absence of Pum1, we identified 1167 transcripts bound by PUM1 in granulosa cells, consistent with other known regulons regulated by RNA binding proteins [3, 24, 40]. PUM1 mRNA targets were enriched for pathways involved in developmental processes and cell proliferation, similar to what is reported for other species [40]. Transcripts in the cell cycle phase transition pathway (Supplementary Table S4) were enriched, revealing a PUM-mediated cell cycle regulon (PCCR), including previously reported downstream targets of PUM proteins in cell cycle regulation, such as Cdkn1b [22] and E2F3 [60]. Loss of Pum1 led to increase in protein level of some PCCR targets as well as decrease in protein level of some other PCCR targets, suggesting PUM1 could act in both promotion and repression of translation in the same cells, depending on the targets [9, 24]. Given that some of the PCCR genes are also expressed in oocytes, we not only performed Western on Pum1 knockout ovaries but also on purified mutant granulosa cells. Overall, the protein expression changes in granulosa cells are consistent with those in ovaries, only differing in the degree of change. Both CDKN1B and E2F3 exhibited stronger change in granulosa cells than ovaries, but their changes in absence of Pum1 are in opposite direction with increased expression of CDKN1B and decreased expression of E2F3. The mechanisms of such opposite effect of PUM1 are unclear and may result from the different protein partners of PUM1 on different transcripts, future study with ribosome-profiling and protein–protein interaction could elucidate the mechanisms by which PUM produces opposite effects on its target translation. What is remarkable is that opposite effects of PUM1 on the cell cycle regulator translation appears well-coordinated based on the nature of cell cycle regulators, so that PUM1 promote translation of positive cell cycle regulators yet repress negative cell cycle regulators. We hence proposed that PUM1-mediated translational control provided an integrated layer of control of cell cycle regulation to promote cell proliferation.

CDK activity is determined by cyclical fluctuations in cyclin levels controlled by various mechanisms, such as inhibitory phosphorylation of WEE1 and a structural rearrangement of the CDK active site by CDKN1B (P27) binding. CDKN1B is a CDK inhibitor (CDKI) that regulates cyclin–CDK complex assembly and catalytic activity. Studies have found that CDKN1B mainly binds and inactivates cyclin D, E, A, and B-dependent kinase complexes [42, 43]. WEE1 catalyzes the inhibitory phosphorylation of cyclin–CDK complexes and delays S phase onset and G2/M transition [43]. Our study indicated that CDKN1B and WEE1 are post-transcriptionally regulated by PUM1, such that PUM1 indirectly upregulates cyclin–CDK kinase complexes through repression of CDKN1B and WEE1 translation. The cyclinD-E2F-Rb-cyclinE feedback is carefully regulated by PUM1 and ensures G1 progression and G1/S transition. Lin et al. detected a gradual increase in PUM1 expression during cell cycle progression [22]. In the late S phase and early M phase, the translational repression of PUM1 along with ubiquitination degradation would cause a reduction of CCNA and CCNB proteins to facilitate G2/M progression. While the roles of transcriptional regulation of cell cycle machinery via localized growth pathways in cell proliferation and organ size control are well-established [61, 62], it is less clear to what extent posttranscriptional regulation plays in cell cycle progression and organ size control. Translational control has emerged as an important enabler of cell fate and developmental transition, such as stem cells and differentiation during development [5]. Our study revealed PUM1 as a global translational regulator of granulosa cell proliferation, achieving integrated translational control of cell cycle via binding to various cell cycle regulators. Granulosa cell proliferation of preovulatory follicles could be induced by increasing the expression level of CCDN2 relative to CDKN1B but terminated by downregulating CCND2 level and upregulating CDKN1B under hormonal control [35], Reduced expression of CCND2, increased expression of CDKN1B in the absence of PUM1 and the resultant reduced granulosa cell proliferation and follicular growth is consistent with such a mechanism of balanced expression of positive and negative cell cycle regulators. PUM-mediated translational control may represent a fine-tuning control mechanism of follicular growth to maintain homeostasis and fertility. Future study of integrated PUM-mediated translational regulation under hormonal regulation or environmental stress may shed further light on fertility maintenance and reproductive homeostasis.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Youqiang Su for his help and advice throughout the project. We also would like to thank Drs. Takeshi Kurita, Alec Wang, and Monica Laronda for discussion and comments on this manuscript. We thank Drs. Mingxi Liu and Francesca Duncan for discussion, and Jianmin Li for providing hamster tissue.

Author contributions

EYX initiated this project, EYX and ZH provided the major funding and supervision for the research, XL, and EYX wrote the manuscript. XL, MZh, MZ, DC, ZhX, HL, ZB, TZh performed the experiments. All authors have discussed the results and made comments on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant (31771652, 81270737 and 81830100).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Data availability statement

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the corresponding author.

Ethics approval

All animal experiment protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) of Nanjing Medical University and were in compliance with ethical regulations and institutional guidelines.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

All authors have consented for a publication in the CMLS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Frost ER, Taylor G, Baker MA, et al. Establishing and maintaining fertility: the importance of cell cycle arrest. Genes Dev. 2021;35(910):619–634. doi: 10.1101/gad.348151.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitfield ML, Sherlock G, Saldanha AJ, et al. Identification of genes periodically expressed in the human cell cycle and their expression in tumors. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1977–2000. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keene JD. RNA regulons: coordination of post-transcriptional events. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:533–543. doi: 10.1038/nrg2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kronja I, Orr-Weaver TL. Translational regulation of the cell cycle: when, where, how and why? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366:3638–3652. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teixeira FK, Lehmann R. Translational control during developmental transitions. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2019;11(6):32987. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a032987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park JE, Yi H, Kim Y, et al. Regulation of Poly(A) tail and translation during the somatic cell cycle. Mol Cell. 2016;62:462–471. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stumpf CR, Moreno MV, Olshen AB, et al. The translational landscape of the mammalian cell cycle. Mol Cell. 2013;52:574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanenbaum ME, Stern-Ginossar N, Weissman JS, et al. Regulation of mRNA translation during mitosis. Elife. 2015;4:7957. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstrohm AC, Hall TMT, McKenney KM. Post-transcriptional regulatory functions of mammalian pumilio proteins. Trends Genet. 2018;34:972–990. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimble J, Page DC. The mysteries of sexual identity. The germ cell's perspective. Science. 2007;16:400–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1142109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao Q, Padmanabhan K, Richter JD. Pumilio 2 controls translation by competing with eIF4E for 7-methyl guanosine cap recognition. RNA. 2010;16:221–227. doi: 10.1261/rna.1884610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakahata S, Kotani T, Mita K, et al. Involvement of Xenopus Pumilio in the translational regulation that is specific to cyclin B1 mRNA during oocyte maturation. Mech Dev. 2003;120:865–880. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(03)00160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Padmanabhan K, Richter JD. Regulated Pumilio-2 binding controls RINGO/Spy mRNA translation and CPEB activation. Genes Dev. 2006;20:199–209. doi: 10.1101/gad.1383106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen D, Zheng W, Lin A, et al. Pumilio 1 suppresses multiple activators of p53 to safeguard spermatogenesis. Curr Biol. 2012;22:420–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mak W, Fang C, Holden T, et al. An important role of pumilio 1 in regulating the development of the mammalian female germline. Biol Reprod. 2016;94(6):134. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.137497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mak W, Xia J, Cheng EC, et al. A role of Pumilio 1 in mammalian oocyte maturation and maternal phase of embryogenesis. Cell Biosci. 2018;8:54. doi: 10.1186/s13578-018-0251-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu EY, Chang R, Salmon NA, et al. A gene trap mutation of a murine homolog of the Drosophila stem cell factor Pumilio results in smaller testes but does not affect litter size or fertility. Mol Reprod Dev. 2007;74:912–921. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong H, Zhu M, Meng L, et al. Pumilio2 regulates synaptic plasticity via translational repression of synaptic receptors in mice. Oncotarget. 2018;9:32134–32148. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gennarino VA, Palmer E, McDonell LM, et al. A mild PUM1 mutation is associated with adult-onset ataxia, whereas haploinsufficiency causes developmental delay and seizures. Cell. 2018;172:924–936. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gennarino VA, Singh RK, White J, et al. Pumilio1 haploinsufficiency leads to SCA1-like neurodegeneration by increasing wild-type ataxin1 levels. Cell. 2015;160:1087–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kopp F, Elguindy M, Yalvac ME, et al. PUMILIO hyperactivity drives premature aging of Norad-deficient mice. Elife. 2019;8:1–31. doi: 10.7554/eLife.42650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin K, Qiang W, Zhu M, et al. Mammalian Pum1 and Pum2 control body size via translational regulation of the cell cycle inhibitor Cdkn1b. Cell Rep. 2019;26:2434–2450. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin K, Zhang S, Shi Q, et al. Essential requirement of mammalian Pumilio family in embryonic development. Mol Biol Cell. 2018;29:2922–2932. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E18-06-0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uyhazi KE, Yang Y, Liu N, et al. Pumilio proteins utilize distinct regulatory mechanisms to achieve complementary functions required for pluripotency and embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:7851–7862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1916471117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vessey JP, Schoderboeck L, Gingl E, et al. Mammalian Pumilio 2 regulates dendrite morphogenesis and synaptic function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3222–3227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907128107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang C, Zhu T, Chen Y, et al. Loss of preimplantation embryo resulting from a Pum1 gene trap mutation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;462:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang M, Chen D, Xia J, et al. Post-transcriptional regulation of mouse neurogenesis by Pumilio proteins. Genes Dev. 2017;31:1354–1369. doi: 10.1101/gad.298752.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matzuk M, Burns KH. Genetics of mammalian reproduction: modeling the end of the germline. Annu Rev Physiol. 2012;74:503–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, Melton C, Suh N, et al. Genome-wide analysis of translation reveals a critical role for deleted in azoospermia-like (Dazl) at the oocyte-to-zygote transition. Genes Dev. 2011;25:755–766. doi: 10.1101/gad.2028911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eppig JJ. Oocyte control of ovarian follicular development and function in mammals. Reproduction. 2001;122(6):829–838. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGee EA, Hsueh AJ. Initial and cyclic recruitment of ovarian follicles. Endocr Rev. 2000;21(2):200–214. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.2.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das N, Kumar TR. Molecular regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone synthesis, secretion and action. J Mol Endocrinol. 2018;60(3):R131–R155. doi: 10.1530/JME-17-0308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gershon E, Dekel N. Newly identified regulators of ovarian folliculogenesis and ovulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4565. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao MC, Midgley AR, Richards JS. Hormonal regulation of ovarian cellular proliferation. Cell. 1978;14:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robker RL, Richards JS. Hormone-induced proliferation and differentiation of granulosa cells: a coordinated balance of the cell cycle regulators cyclin D2 and p27Kip1. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:924–940. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.7.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jagarlamudi K, Rajkovic A. Oogenesis: transcriptional regulators and mouse models. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;356(1–2):31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takei N, Takada Y, Kawamura S, et al. Changes in subcellular structures and states of pumilio 1 regulate the translation of target Mad2 and cyclin B1 mRNAs. J Cell Sci. 2020;133:249128. doi: 10.1242/jcs.249128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Nostrand EL, Pratt GA, Shishkin AA, et al. Robust transcriptome-wide discovery of RNA-binding protein binding sites with enhanced CLIP (eCLIP) Nat Methods. 2016;13:508–514. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah A, Qian Y, Weyn-Vanhentenryck SM, et al. CLIP Tool Kit (CTK): a flexible and robust pipeline to analyze CLIP sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:566–567. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prasad A, Porter DF, Kroll-Conner PL, et al. The PUF binding landscape in metazoan germ cells. RNA. 2016;22:1026–1043. doi: 10.1261/rna.055871.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee S, Kopp F, Chang TC, et al. Noncoding RNA NORAD regulates genomic stability by sequestering PUMILIO proteins. Cell. 2016;164:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abbastabar M, Kheyrollah M, Azizian K, et al. Multiple functions of p27 in cell cycle, apoptosis, epigenetic modification and transcriptional regulation for the control of cell growth: a double-edged sword protein. DNA Repair (Amst) 2018;69:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elbaek CR, Petrosius V, Sorensen CS. WEE1 kinase limits CDK activities to safeguard DNA replication and mitotic entry. Mutat Res. 2020;819–820:111694. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2020.111694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu L, Michowski W, Inuzuka H, et al. G1 cyclins link proliferation, pluripotency and differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19:177–188. doi: 10.1038/ncb3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin KB, Zhang SK, Chen JL et al (2017) Generation and functional characterization of a conditional Pumilio2 null allele. J Biomed Res 0:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Li X, Yang J, Chen X, et al. PUM1 represses CDKN1B translation and contributes to prostate cancer progression. J Biomed Res. 2021;35(5):371–382. doi: 10.7555/JBR.35.20210067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asaoka-Taguchi M, Yamada M, Nakamura A, et al. Maternal Pumilio acts together with Nanos in germline development in Drosophila embryos. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:431–437. doi: 10.1038/15666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crittenden SL, Bernstein DS, Bachorik JL, et al. A conserved RNA-binding protein controls germline stem cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2002;417:660–663. doi: 10.1038/nature754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Forbes A, Lehmann R. Nanos and Pumilio have critical roles in the development and function of germline stem cells. Dev (Camb, Engl) 1998;125:679–690. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin H, Spradling AC. A novel group of pumilio mutations affects the asymmetric division of germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 1997;124:2463–2476. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.12.2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wickens M, Bernstein DS, Kimble J, et al. A PUF family portrait: 3'UTR regulation as a way of life. Trends Genet. 2002;18:150–157. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(01)02616-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]