Abstract

About 11% of all human disease-associated gene lesions are nonsense mutations, resulting in the introduction of an in-frame premature translation-termination codon (PTC) into the protein-coding gene sequence. When translated, PTC-containing mRNAs originate truncated and often dysfunctional proteins that might be non-functional or have gain-of-function or dominant-negative effects. Therapeutic strategies aimed at suppressing PTCs to restore deficient protein function—the so-called nonsense suppression (or PTC readthrough) therapies—have the potential to provide a therapeutic benefit for many patients and in a broad range of genetic disorders, including cancer. These therapeutic approaches comprise the use of translational readthrough-inducing compounds that make the translational machinery recode an in-frame PTC into a sense codon. However, most of the mRNAs carrying a PTC can be rapidly degraded by the surveillance mechanism of nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), thus decreasing the levels of PTC-containing mRNAs in the cell and their availability for PTC readthrough. Accordingly, the use of NMD inhibitors, or readthrough-compound potentiators, may enhance the efficiency of PTC suppression. Here, we review the mechanisms of PTC readthrough and their regulation, as well as the recent advances in the development of novel approaches for PTC suppression, and their role in personalized medicine.

Keywords: Nonsense mutation, Premature termination codon (PTC), Readthrough therapy, Stop codon readthrough, Translation termination

Introduction

Nonsense mutations, resulting in the introduction of a premature translation-termination codon (PTC; UAA, UAG, or UGA) into the protein-coding gene sequence, account for approximately 11% of all described genetic alterations causing human inherited disease [1]. PTCs can arise from single nucleotide mutations, by genetic or somatic mutations and errors during transcription or splicing [2–4]. Nevertheless, PTCs can also arise as a consequence of non-faulty regulated processes of the mRNA metabolism, such as somatic rearrangements in the DNA, alternative splicing or utilization of alternative AUG initiation sites [4–7]. mRNAs carrying a PTC are, generally, committed to rapid decay through the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) mechanism [3–8]. Failure to induce this mechanism has pathological consequences in humans [5, 7]. Indeed, translation of the PTC-containing mRNAs generates truncated, often dysfunctional, polypeptides that can have a dominant-negative or gain-of-function effect on gene function, depending on the gene affected [7, 9]. For example, dominantly inherited forms of β-thalassemia can be caused by PTCs in the 3′-part of the human β-globin mRNA that do not induce NMD, generating a truncated dominantly negative-acting polypeptide that affects hemoglobin structure and function [8, 9]. As genetic diseases and cancer attributable to PTCs affect millions of patients all over the world, nonsense suppression therapies have the potential to provide a therapeutic benefit for many patients [8]. Most frequently, this therapeutic approach uses readthrough drugs that induce the translational machinery to recode an in-frame PTC into a sense codon [10–13]. Although suppression therapy efficiency is low, for many recessive, loss of function disorders, small amounts of functional protein can be therapeutically relevant in improving function and repressing disease progression [12, 13]. Nevertheless, the efficacy of PTC readthrough stimulation is an important issue to hold in consideration for the treatment of many other disorders. Indeed, many NMD inhibitors, or readthrough-compound potentiators, have been tested to enhance the efficacy of PTC suppression. Here, we review the mechanisms of PTC readthrough and how they are regulated, as well as novel therapeutic approaches based on PTC suppression and strategies to enhance its efficacy.

Mechanisms of translation-termination codon readthrough

Overview of mRNA translation

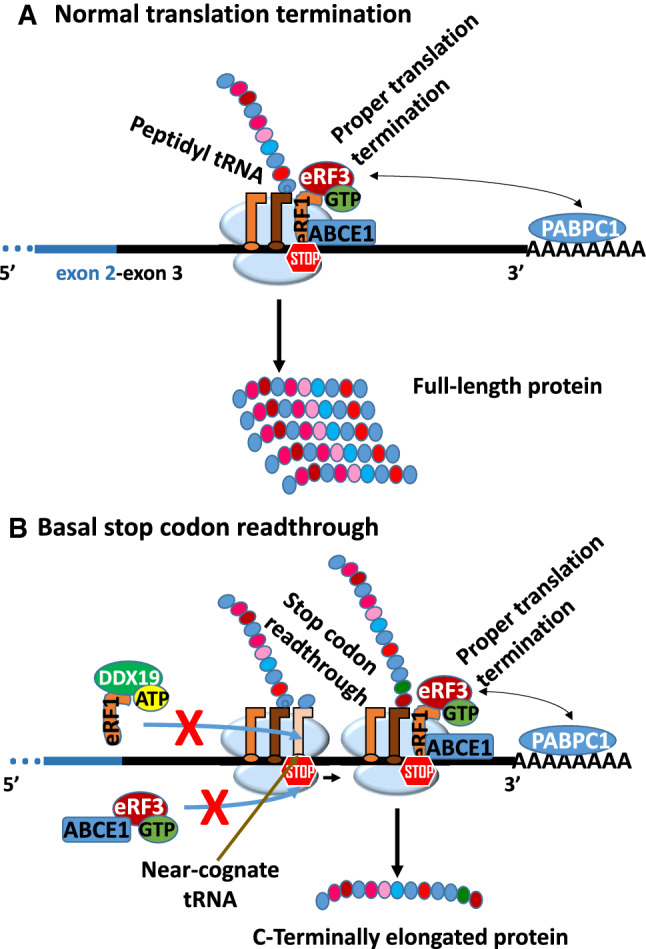

Translation, the process of protein synthesis from an mRNA template, can be divided into four phases—initiation, elongation, termination and ribosome recycling. Canonical eukaryotic mRNA translation initiates with the assembling of the 43S preinitiation complex (PIC) that includes the 40S ribosomal subunit bound to the eukaryotic initiation factor (eIF) 1, eIF1A, eIF2-GTP-Met-tRNAi, eIF3, and eIF5 [14, 15]. In parallel, the eIF4F complex, bound to the mRNA 5′-end cap structure, promotes binding of the 43S PIC to the mRNA to form the 48S complex. Subsequently, the 43S PIC scans the mRNA in a 5′–3′ direction until it recognizes an initiation codon (usually, an AUG) in a consensus sequence, base-pairing with Met-tRNAi [14–17]. Once the anticodon of the Met-tRNAi has engaged an AUG triplet, there is joining of the 60S ribosomal subunit and formation of the 80S ribosome at the initiation codon [14–17]. At this point, the ribosome is ready to start translation elongation and the polypeptide is synthesized [18–20]. Translation termination occurs when an elongating ribosome encounters an in-frame stop codon. In eukaryotic cells, all three stop codons (UAA, UAG or UGA) are decoded by the eukaryotic release factor 1 (eRF1) [21, 22]. eRF1 has a three-dimensional structure that mimics the size and shape of an aminoacyl-tRNA [23], and thus enters the ribosomal A site, to trigger hydrolysis of the peptidyl-tRNA at the ribosomal peptidyl transferase center [21]. In its turn, eRF1 binds to and activates another factor—eRF3, which is a ribosome-dependent and eRF1-dependent GTPase. In fact, the middle domain and the C-terminus of eRF1 interacts with eRF3 [24], and the C-terminus of eRF3 (GTPase) interacts with GTP, forming a ternary complex [25] (Fig. 1a). Hydrolysis of GTP by eRF3 allows the accommodation of the eRF1 in the peptidyl transferase center due to a conformational change in the structure of eRF1; this promotes the cleavage of the peptidyl-tRNA bond and the release of the polypeptide from the ribosome [26]. The productive binding of the eRF1–eRF3 complex to the ribosome is enhanced by the poly(A)-binding proteins (PABP), present in the 3′-end of the mRNA (Fig. 1a), via their interactions with the N-terminal domain of eRF3 [27]. More recently, it has been described that the activity of the canonical termination complex (eRF1–eRF3) can be modulated by several factors, such as DDX19, a DEAD-box ATP-dependent RNA helicase that seems to bind directly to eRF1 [28]. This interaction appears to aid in positioning eRF1 at stop codons and promoting eRF1–eRF3 complex formation [29]. Furthermore, the ATPase ABCE1 is, as well, able to interact with eRF1, substituting eRF3, and this interaction increases the rate of peptide release [30, 31]. The interaction of eRF1 with ABCE1, and hydrolysis of ATP to ADP by ABCE1, promote ribosomal recycling after peptide release [26, 30, 32]. In addition, ribosomal recycling involves eIF3, which promotes the dissociation of the 80S subunit into 40S and 60S subunits, eIF1 that mediates the dissociation of the 40S subunit from the tRNA, and eIF3j that mediates the dissociation of mRNA [26, 32].

Fig. 1.

Translation termination (a) or basal readthrough (b) at a normal stop codon. a In eukaryotic cells, all three stop codons are decoded by the eukaryotic release factor 1 (eRF1) when it enters the ribosomal A site. eRF1 also binds to and activates eRF3, which is a GTPase that hydrolyses GTP. Hydrolysis of GTP by eRF3 allows the accommodation of the eRF1 in the peptidyl transferase center. This promotes the release of the polypeptide from the ribosome. The productive binding of the eRF1–eRF3 complex to the ribosome is enhanced by the cytoplasmic 1 poly(A)-binding proteins (PABPC1), inducing a proper translation termination reaction. The ATPase ABCE1 is also able to interact with eRF1. b Basal stop codon readthrough occurs when normal translation termination is not efficient. In this case, a near-cognate tRNA is indeed able to outcompete eRF1 (which remains bound to DDX19). In this condition, the near-cognate tRNA accommodates in the A site of the ribosome, leading to the misreading of the stop codon into a sense codon, and an amino acid is incorporated into the nascent polypeptide. Consequently, translation resumes until the ribosome reaches another stop codon in the same open reading frame and a C-terminal elongated protein is synthesized

Basal readthrough of natural stop codons

During translation termination, a stop codon enters the A site of the ribosome and there is a competition between eRF1 and aminoacyl-tRNAs to be accommodated. However, there are no tRNAs with an anticodon complementary to the stop codons. Thus, eRF1 is able to outcompete tRNAs for stop codon binding, which results in a highly accurate and efficient translation termination process, with natural stop codons being suppressed at a rate of ≤ 0.1% [33]. In the few translation cycles in which normal translation termination is not efficient, its suppression can occur by ribosomal frameshifting (where the ribosome slides on the mRNA, changing the frame of translation), or basal stop codon readthrough (Fig. 1b) [34]. In the case of stop codon readthrough, a near-cognate tRNA is indeed able to outcompete eRF1 at the A site of the ribosome by base-pairing two out of the three anticodon bases to the stop codon in the mRNA [11, 12]. In this condition, the near-cognate tRNA accommodates in the A site of the ribosome, leading to the misreading of the stop codon into a sense codon, the so-called basal readthrough of the stop codon (Fig. 1b). Therefore, an amino acid is incorporated into the nascent polypeptide, and translation resumes until the ribosome reaches another stop codon in the same ORF (Fig. 1b) [35, 36]. In some transcripts, the cell can use basal stop codon readthrough as a mechanism to express two protein isoforms (see “Programmed readthrough of natural stop codons”).

Although stop codon readthrough has been studied for many years, the mechanism by which cis-elements and trans-acting factors affect translation termination and promote stop codon readthrough still remains to be fully understood. Physiologically, the basal readthrough efficiency of natural stop codons in mammalian species ranges between 0.01 and 0.1% [37, 38], and 0.3% in yeast [39, 40], which is considered low compared with induced readthrough [37, 38]. The efficiency of basal stop codon readthrough depends on several factors, such as the (1) type of the stop codon, and the sequence surrounding the stop codon (both 3′ context and 5′ context) [34, 37, 41, 42], (2) mRNA level and stability of a transcript, available for readthrough and translation, that can be modulated through the NMD mechanism [43, 44], (3) proximal RNA structures [45, 46], (4) RNA modifications [47], (5) presence of RNA binding proteins [48], (6) availability of aminoacylated near-cognate tRNA [49–51], (7) presence of compounds that stimulate the readthrough (see “Pharmacologically-induced readthrough of PTCs by aminoglycosides” and “Pharmacologically-induced readthrough of PTCs by non-aminoglycosides”), or (8) post-translational modifications of some ribosomal proteins or release factors [52].

Regarding the association of the type of stop codon and basal readthrough, in eukaryotes, the readthrough is more efficient in UGA codons, followed by UAG [37, 53–55]. UAA is the stop codon with less susceptibility to readthrough [53, 54]. In addition to stop codon identity, the surrounding sequences play a major role in the basal readthrough of these codons. It is known that the first and third nucleotides immediately downstream of the stop codon can influence translation termination efficacy [34, 39, 56, 57]. In fact, the nucleotide immediately downstream of the UGA stop codon has been described as a major contributor to readthrough efficiency: some authors have suggested that when the UGA is followed downstream by a C, the readthrough efficiency is higher than when followed by a U, A, or G (C > U > G > A)[35, 55, 58]. On the other hand, some authors have suggested a different readthrough efficiency order, such as C > A, U > G for the UGA and UAA codons observed in yeast models [34], while for the UAG codon readthrough is more efficient when there is a G at position (+ 4), followed by a C, A, and U [34]. In addition to these findings, some studies also suggest that when pyrimidine is located in the (+ 4) position, the termination translation (in the presence or absence of an enhancing readthrough compound) is less efficient, leading to a higher readthrough of the stop codon [37, 56, 57]. Recently, ribosome profiling data have shown that the two nucleotides immediately downstream of the stop codon strongly affect readthrough efficiency; the presence of adenosines or uridines surrounding the stop codon favors stop codon readthrough and the presence of guanosines or cytosines favors translation termination [59]. Furthermore, it has been described that even the nucleotides at positions (+ 5), (+ 8), and (+ 9) may influence stop codon readthrough efficiency [39, 40].

With the aim to understand the molecular mechanism underlying the process of stop codon readthrough, different authors have shown that it may also be stimulated by: the sequences CAA or CUAG immediately downstream of the stop codon [34, 38, 54, 57], CU downstream of the UAG codon (reviewed in [35]), or CAAUUA sequence downstream of any stop codon [39, 60]. This stimulation may be explained by the formation of stem-loops and secondary structures in the 3′UTR of the mRNA, which can interact with the ribosome [46, 61]. Although both the downstream and upstream contexts of a sequence play master roles in the efficiency of the readthrough of a stop codon, however, the upstream context is less understood. A study has shown that the presence of adenines in the two positions upstream of the stop codon can stimulate the readthrough of predominantly UAG stop codons. It has been hypothesized that a decrease in the accuracy of translation may be caused by a modification of these adenines in the mRNA structure at the P site of the ribosome, leading to a modification of the structure of the decoding center of the ribosome. These data have proved that the rate of stop codon readthrough can be regulated by a diversity of cis-acting elements [62].

Among the trans-acting factors potentially involved in modulating stop codon readthrough, are the proteins involved in translation termination, such as eRF1, eRF3 and Dbp5/DDX19. Indeed, it has been shown that loss of function of translation termination factors impacts stop codon readthrough. For example, the dead-box RNA helicase Dbp5/DDX19 is involved in translation termination by interacting with eRF1 and bringing it in contact with eRF3 (Fig. 1). However, when Dbp5/DDX19 is non-functional, eRF1 spontaneously approaches the ribosome and interacts prematurely with eRF3. This interaction leads to inefficient translation termination and promotes the incorporation of a near-cognate tRNA and the stop codon readthrough [29, 63].

Programmed readthrough of natural stop codons

Programmed stop codon readthrough allows translation of mRNAs beyond the canonical stop codon. This particular mechanism is responsible for the synthesis of protein isoforms containing a C-terminus extension, allowing the expansion of the proteome. The importance of programmed stop codon readthrough in the generation of protein isoforms is not completely understood. Programmed stop codon readthrough seems to be exclusive for specific transcripts, leading to the synthesis of specific and controlled protein isoforms with particular functions [64–66]. It has been described in viruses, fungi, Drosophila, and mammals [64–66]. However, in human cells, programmed stop codon readthrough seems to be a very rare event, described, until now, only in a few genes: the myelin protein zero (MPZ), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), opioid-related nociceptin receptor 1 (OPRL1), opioid receptor Kappa 1 (OPRK1), aquaporin 4 (AQP4), mitogen-activated protein kinase 10 (MAPK10), peroxisomal lactate dehydrogenase B (LDHB), NAD-LDHB, NAD-dependent malate dehydrogenase 1 (MDH1), and vitamin D receptor (VDR) [38, 66–70].

The full panoply of cis-elements and trans-acting factors that can regulate the levels of programmed stop codon readthrough is still unknown. Data have shown that the efficiency of programmed stop codon readthrough, similar to the basal translation readthrough, also depends on tRNA abundance, RNA secondary structures, release factor levels, stop codon identity and surrounding context, and post-translational modifications of either the ribosome or release factors [34, 47, 51]. It seems that some of these elements/factors have a similar role in the readthrough of the stop codon of all mRNAs, however, others are specific to a given mRNA. For instance, the interaction between a cis-acting element and the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 (hnRNPA2/B1) promotes programmed translational readthrough on the VEGFA mRNA by decoding the UGA stop codon as serine, generating the VEGF-Ax isoform with a unique 22-amino-acid C-terminus extension [68].

Trying to understand how pre-termination ribosomes recognize a programmed stop codon for readthrough and how the readthrough mechanism occurs, Beznosková et al. have shown that eIF3 is able to promote programmed readthrough on all three stop codons [71]. For that, eIF3 interacts with pre-termination complexes where it interferes with the eRF1 decoding of the third/wobble position of the stop codon if in an unfavorable termination context, which allows incorporation of near-cognate tRNAs [71]. Accordingly, the knockdown of the subunits eIF3a and eIF3g in HeLa cells significantly decreases the efficiency of stop codon readthrough, indicating that eIF3 has, in fact, an important function in programmed stop codon readthrough [71]. However, it is important to note that eIF3 acts specifically on genes containing particular stimulatory elements downstream from the stop codon that are known to promote programmed stop codon readthrough [71]. Furthermore, recent data have shown that miRNAs can also be determinants in modulating specific stop codon readthrough. This is the case of Let7a miRNA that is able to promote programmed translational readthrough on the AGO1 mRNA by binding to a cis-acting element downstream of the canonical stop codon, which results in an isoform termed as Ago1x [72]. However, it remains to be shown if a similar mechanism occurs in other mRNAs.

Basal readthrough of PTCs

Nonsense mutations (or PTCs) may arise from 23 different nucleotide substitutions [UAG (40.4%), UGA (38.5%), or UAA (21.1%)]. The most frequent substitutions are CGA to TGA (21%) and CAG to TAG (19%) [1]. PTCs can also arise from errors during transcription, mRNA processing [73, 74], or from non-faulty regulated processes of mRNA metabolism, such as alternative splicing or use of alternative initiation codons [75]. PTCs lead to premature translation termination and, consequently, to the production of truncated proteins [76] (Fig. 2a) that can have dominant-negative or gain-of-function effects [7, 9]. To prevent the synthesis of these truncated proteins, the cell developed a surveillance pathway called nonsense-mediated RNA decay (NMD) [73, 78–81]. Moreover, one-third of all inherited genetic diseases are caused by PTCs, therefore NMD serves as a major modulator of these disorders, their phenotypes, and their severity [5, 7, 8, 82, 83]. More recently, the development of high-throughput technologies has revealed that NMD is also involved in the regulation of 10–20% of the wild-type eukaryotic mRNAs [75, 84–88]. These so-called natural NMD-targets present specific features—NMD-inducing features—that are responsible for eliciting their degradation through the process of NMD. Examples of NMD-inducing features are the existence of an intron downstream of the stop codon, i.e. in the 3′UTR [89], or the presence of upstream open reading frame(s) (uORFs) in the 5′UTR of the transcripts [90], as well as the existence of a long 3′UTR [78, 79, 91–93]. Therefore, NMD not only regulates the levels of certain physiological mRNAs, but also participates in the regulation of many essential biological processes, having an important role in development, stress and cancer (reviewed in [94]).

Fig. 2.

Translation termination (a) or nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) (b) at a premature termination codon (PTC). a If the PTC is located downstream of the last exon–exon junction, a proper translation termination reaction occurs and there is synthesis of a truncated protein. b If the mRNA carries a PTC located more than 55 nucleotides upstream of the last exon–exon junction, when the ribosome reaches the PTC, the termination complex that is formed cannot interact with the cytoplasmic poly(A)-binding protein (PABPC) and instead it interacts with the NMD-factor UPF1. Under these conditions, the mRNA is rapidly degraded by the process of NMD

As previously referred for physiological stop codons, translation termination at a PTC is not always effective. In fact, a small percentage of PTCs is also suppressed through the natural mechanism of stop codon readthrough. This basal readthrough, even in small proportions, can explain phenotype variations within patients with the same nonsense mutation. For example, some cystic fibrosis (CF) patients who carry a nonsense mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that leads to the absence of the CFTR protein, and by consequence, a severe phenotype, may present a less severe phenotype, which is attributable to the occurrence of basal PTC readthrough [95, 96]. Of note, the same nonsense mutation in the CFTR gene in different genetic contexts may also cause different levels of CFTR basal channel function, leading to a variation in the CF phenotype [97, 98].

The basal readthrough of a PTC (~ 1%) is more frequent than the basal readthrough of a natural stop codon (≤ 0.1%), but also depends on several factors, including the nature of the PTC and its context and the genetic background [10, 51, 99]. This is explained by the mechanism of translation termination and its efficiency, which is determined by the position of the termination codon relative to the PABP. When PABP is in close proximity with the stop codon, usually the case for natural stop codons, it functions as an enhancer of the translation termination process. This is caused by interaction between PABP and eRF3 during translation termination that stimulates peptide release (Fig. 1). However, in the case of a PTC located distant from the PABP (Fig. 2b) but located more than 55 nucleotides upstream of the last exon–exon junction of a transcript, there is no interaction between eRF3 and PABP, which leads to a pause in the translation termination process. This pause has been described for several years as an inducer of NMD (Fig. 2b) or an enhancer of ribosomal readthrough by allowing aminoacyl-tRNA to be incorporated (Fig. 3a). When the binding of a near-cognate tRNA to a PTC overcomes the binding of eRF1, an amino acid is incorporated into the nascent polypeptide and NMD is inhibited [36]. Despite this model having been described by several authors, it has recently been questioned by Karousis et al. In their study, the authors have shown a similar ribosomal occupancy at NMD-sensitive and -insensitive PTCs, suggesting that NMD activation, or PTC readthrough, does not depend on the ribosome pausing at the termination codon [100]. During PTC readthrough, the incorporated amino acid is not random, it is donated by an aminoacyl-tRNA with a mismatch within the anticodon; however, it may not be the same amino acid encoded by the original sense codon, prior to the nonsense mutation [10, 38]. Thus, depending on the location and function of the initial amino acid encoded, the structure and function of the protein may or may not be altered [10]. It has been described that at UGA codons, the most likely amino acids to be incorporated are tryptophan, arginine and cystine, and at UAG and UAA codons, the most likely inserted amino acids are glutamine, tyrosine and lysine [51, 101]. All these issues must be taken into consideration when new therapeutic strategies are designed to enhance the process of PTC readthrough. In fact, several studies have been published and different approaches have been developed to enhance the process of PTC readthrough, including the use of several aminoglycosides and non-aminoglycosides, suppressor tRNAs, pseudouridylation, and RNA editing, strategies that we review in the next sections.

Fig. 3.

Basal readthrough (a) or pharmacologically induced readthrough (b) at a premature termination codon (PTC). a When an aminoacyl-tRNA is accommodated in the A site of the ribosome instead of eRF1–eRF3 at a PTC, an amino acid is incorporated into the nascent polypeptide. Consequently, translation resumes until the ribosome reaches another stop codon in the same open reading frame. b Some compounds have the ability to increase the binding of near-cognate aminoacyl-tRNAs to the PTC, which allows a more efficient PTC readthrough. This approach constitutes what is called nonsense suppression therapy

Pharmacologically-induced readthrough of PTCs by aminoglycosides

As already described above, the use of some chemical compounds, such as aminoglycosides, can stimulate the readthrough of natural and premature stop codons [10, 35]. The first description of a drug that enhances translational readthrough of a PTC in mammalian cells was in 1985, by Burke and Mogg. These authors documented the readthrough of a PTC by treating COS-7 cells with G418 or paromomycin [102]. This approach constitutes what is called nonsense suppression therapy (Fig. 3b). The goal of nonsense suppression therapy is to use compounds that have the ability to increase the binding of near-cognate aminoacyl-tRNAs to the PTC [11]. The first two decades of efforts to establish efficient nonsense suppression therapies were comprehensively reviewed by Lee and Dougherty in 2012 [12]. Since then, further studies have been published and different approaches have been developed, including the use of several aminoglycosides, which we review below.

Aminoglycosides are a class of structurally related antibiotics of low molecular weight (300–600 Da) that lead to the inhibition of protein synthesis. Even though these aminoglycosides are known to have high toxicity, they were commonly used due to their high efficacy and low cost [103]. Streptomycin was the first aminoglycoside to be isolated (from Streptomyces griseus) and was introduced into clinical use in 1944 for the treatment of Gram-negative bacterial infections [104, 105]. Other aminoglycosides then were isolated, such as neomycin (1949, from S. fradiae), kanamycin (1957, from S. kanamyceticus), paromomycin (1959, from S. rimosus), gentamicin (1963, from M. purpurea), netilmicin (1967, derived from sisomicin), tobramycin (1967, from S. tenebrarius), amikacin (1972, derived from kanamycin), geneticin (also known as G418) (1974, from M. rhodorangea) [106], and amikacin, isepamicin, netilmicin and arbekacin in 1970 and early 1980 [107]. These aminoglycosides can be distinguished into two main classes depending on their structure: the ones containing a 4,6-disubstituted-2-deoxystreptamine ring, such as kanamycin, amikacin, gentamicin, G418, netilmicin, tobramycin, and those with a 4,5-disubstituted-2-deoxystreptamine ring, such as neomycin and paromomycin. In the case of streptomycin, this is a non-deoxystreptamine compound [56].

These compounds have two different mechanisms of action, depending on the dose used: at low doses, they tightly bind to the decoding center of the bacterial ribosome inducing translational misreading [10]; at high doses, these antibiotics lead to an inhibition of translation initiation, interfering with protein synthesis [108–110]. Despite the toxicity of aminoglycosides, they are advantageous in clinical use due to the fact that they inhibit prokaryotic protein synthesis at significantly lower concentrations than eukaryotic protein synthesis, as they have low efficiency in binding to the eukaryotic ribosomal decoding center due to differences at two key nucleotides of the rRNA at the ribosomal decoding site [12, 111–113].

Burke and Mogg demonstrated, for the first time, the ability of gentamicin to induce the readthrough of a nonsense codon, in yeast and mammalian cells, and the potential therapeutic benefit to treat PTC-associated genetic diseases [102]. Since this breakthrough, many other aminoglycoside compounds have been proven to induce translational misreading in mammalian cells and readthrough of stop codons by decreasing the fidelity of the proofreading activity of the decoding center of the ribosome [11, 114, 115]. However, this ability to induce readthrough of the stop codon is not shared between all aminoglycosides. For example, studies with tobramycin suggest that it does not promote significant levels of readthrough [56]. In contrast, G418 and paromomycin seem to have the greatest stop codon readthrough effect among aminoglycosides which can be justified by their chemical structures and their bondings to the A site of the ribosome [111, 112]. Furthermore, the efficiency of the readthrough of a stop codon by an aminoglycoside is also dependent on the efficiency of translation termination at that stop codon in the absence of a drug, which also depends on the stop codon identity, sequence context and other factors mentioned above [116]. For example, in the presence of gentamicin, the position (− 1) upstream of the stop codon is considered a major determinant in readthrough efficiency [37]. It was hypothesized by Floquet et al. that an uracil at this position can induce structural rearrangements that lead to efficient readthrough of the stop codon and that a combination of both an uracil and a cytosine, immediately upstream and downstream of the stop codon (U STOP C) would induce even higher levels of stop codon readthrough [37].

As described above, many aminoglycosides have been tested as potential suppressors of PTCs in vitro using reporters or gene constructs containing different PTCs, in cultured cell lines, in animal models for genetic diseases, and even in clinical trials [10, 59, 117–119]. The first genetic disease associated with the potential benefit of aminoglycosides as an enhancer of PTC readthrough was CF. CF can be caused by mutations in the CFTR gene that lead to premature translation termination and therefore to the presence of truncated protein. Early studies proved the ability of G418 and gentamicin to suppress nonsense mutations in the CFTR gene, leading to the translation of the functional full-length CFTR protein in bronchial epithelial cell lines [120, 121]. The therapeutic potential of gentamicin as a PTC suppressor has been tested in several genetic disorders summarized in Table 1. Even though these studies indicated positive results, other clinical trials performed with gentamicin did not reveal significant progress in some PTC-carrying CF or Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) patients being treated [10], indicating that aminoglycosides may not have the same effects for all the diseases or for patients with the same disease and nonsense mutation. To address this, more work needs to be done to develop more effective and robust drugs.

Table 1.

Summary of studies where gentamicin was shown to be a PTC suppressor in genetic disorders

| Disease | Gene/model | References |

|---|---|---|

| Ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T) | Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) gene | [127, 199] |

| p53-tumor related disease | p53 cDNA and gene | [130, 131] |

| Congenital muscular dystrophy (CMD) | Laminin alpha2 chain (LAMA) mRNA in CMD myotubes | [54, 177] |

| Genetic eye disorders | Zebrafish rep1, pax2.1, and lamb1 genes | [125] |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) | Dystrophin gene in mouse model | [57, 116, 271] |

| Rett syndrome (RTT) | Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) gene | [126] |

| Long QT syndrome (LQTS) | Human ether-a-go-go-related (hERG) gene | [272] |

| Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)-mediated colon cancer | (APC)-mediated colon cancer in mouse model | [129] |

| Lysosomal storage disease mucopolysaccharidosis I-Hurler (MPS I-H) | Mouse model | [267] |

| Cystic fibrosis (CF) and hemophilia | Mouse models | [132, 160, 273, 274] |

| Cystic fibrosis | Cultured cells | 120, 121] |

| Cystic fibrosis | Patients with CF | [278, 279] |

| Xeroderma pigmentosum complementation group C (XPC) | Cells XPC patients | [275] |

| Hemophilia | Patients with hemophilia | [119, 276] |

| Hailey–Hailey disease | Patients with Hailey–Hailey disease | [277] |

| Neurodevelopmental disorders | Cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 (CDKL5) gene | [280] |

| Herlitz junctional epidermolysis bullosa (H-JEB) | Laminin subunit beta-3 (LAMB3) gene | [281] |

| Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) patients | Collagen, type VII, alpha 1 (COL7A1) gene of RDEB patients | (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03012191) |

As indicated above, G418 is an aminoglycoside antibiotic produced by Micromonospora rhodorangea with a structure similar to gentamicin [122]. The mechanism of G418 in translation termination has been studied and described. In eukaryotic cells, G418 seems to block peptide translation by binding to the 80S ribosome, inhibiting the elongation cycle of protein synthesis [123]. Further to its mechanism, the ability of G418 to induce the readthrough of a PTC was also investigated in several disease models summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of studies where G418 was shown to be a PTC suppressor in genetic disorders

| Disease | Gene/model | References |

|---|---|---|

| Autosomal recessive proximal renal tubular acidosis | Solute carrier family 4 member 4 (SLC4A4) gene in cultured cells | [282] |

| β-Thalassemia | β-Globin gene expressed in erythroid precursor cells from homozygous β39-thalassemia patients | [99] |

| p53-tumor related disease | p53 gene | [131, 283] |

| Ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T) | Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) gene | [127] |

| Neurodevelopmental disorder Rett syndrome (RTT) | Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) gene | [126] |

| Cystic fibrosis | Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene | [56] |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) | Dystrophin gene | [57] |

| Xeroderma pigmentosum group C (XPC) patients | XPC gene | [124] |

| Primary ciliary dyskinesia | Selected genes involved in primary ciliary dyskinesia | [284] |

| Long QT syndrome (LQTS) | Human ether-a-go-go-related (hERG) gene | [272] |

| Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)-mediated colon cancer | Mouse models for APC-mediated colon cancer | [129] |

To understand the potential of these aminoglycosides as PTC suppressors, kanamycin, paromomycin and neomycin were tested in the topical treatment of PTC-associated xeroderma pigmentosum group C (XPC) patients. Results have shown that neither of these aminoglycosides was able to increase XPC protein levels, even though there was an increase in skin XPC mRNA levels [124]. Furthermore, paromomycin, was also demonstrated to induce the readthrough of a PTC in zebrafish rep1, pax2.1, and lamb1 genes, as a model for genetic eye diseases [125], in the human MECP2, XPC, dystrophin, ATM and CFTR genes [57, 124, 126–128], and also in a mouse model for APC-mediated colon cancer [129], and in eight PTCs identified in DMD and Becker's muscular dystrophy patients [57]. Amikacin, a compound that belongs to the family of kanamycin, was shown to be able to induce readthrough of a PTC in the p53 gene [130, 131], the MECP2 gene [126], the CFTR gene in a CF mouse model [132], and eight PTCs identified in DMD and Becker's muscular dystrophy patients [57]. Streptomycin was also confirmed to have readthrough-inducing properties, leading to an increase in SMN protein levels in spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) [133–135], as well as in a PTC-harboring MECP2 gene responsible for RTT syndrome [126]. In summary, these aminoglycosides have been proved to have significant impact on the readthrough of PTCs using several disease models. Even when only a low amount of full-length protein is produced, they may have an enormous influence on the patient’s disease phenotype. This is particularly important for recessive disorders, in which low amounts of full-length functional protein are able to restore a clinically less severe phenotype [136]. Therefore, the use of aminoglycosides seems to offer a novel therapeutic for patients with nonsense mutations, particularly when used in short-term treatments, such as cancer diseases caused by nonsense mutations [137].

Even though aminoglycosides may be used in the short-term for several diseases, their long-term use has many side effects. They interfere with several enzyme pathways, having several off-targets, such as the phospholipids of the lysosomal membranes, and when endocytosed they become positively charged in the lysosome [10, 138]. Additionally, aminoglycosides lead to an increase of Ca2+ levels in the mitochondria that drives the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [139, 140]. The similarity of the eukaryotic mitochondrial and prokaryotic ribosomes may also allow aminoglycosides to bind to the mitochondrial ribosome, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and the increase of toxicity and side effects [117, 141]. Actually, the main effects of the toxicity of these compounds are kidney damage, which is reversible, and inner ear damage, which lead to hearing loss [142–144]. This is due to the fact that aminoglycosides, particularly amikacin and neomycin, enter into the cells through megalin, an endocytic receptor that is highly expressed in the proximal tubules of the kidney and hair cells of the inner ear [145]. Among all the aminoglycosides, streptomycin and gentamicin are particularly responsible for generating free radicals that permanently damage the sensory cells and neurons, leading to imbalance [144, 146]. Aminoglycosides also have other effects in the cell: they are able to modulate catalytic RNA features, such as splicing, RNase P and small ribozyme activity [147]. Furthermore, they are able to induce apoptosis due to the activation of stress pathways [140]. For a deep review of aminoglycosides toxicity, please see references [10, 11, 143].

To decrease the toxicity of aminoglycosides, some strategies have been developed. To protect cochlear hair cells, antioxidants, such as d-methionine and N-acetyl-l-cysteine [148], melatonin [149], daptomycin [150], edaravone [140] and salicylate [151, 152], have been used to avoid free-radical formation. Another approach to reduce aminoglycoside toxicity is to encapsulate the aminoglycoside into liposomes, altering the drug distribution and elimination and preventing nephrotoxicity [11], for example in a study using encapsulated gentamicin to decrease its toxic effects while improving its suppressor features in a DMD model [153]. This strategy has also been used in a clinical trial for the treatment of urinary tract infection (UTI) using liposome-encapsulated amikacin [154]. Other compounds that decrease the interaction of aminoglycosides with the lysosome membrane when administrated together are poly-l-aspartate and daptomycin. These compounds decrease the nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity and increase the amount of aminoglycosides available in the cytoplasm [117, 155]. This increase of aminoglycosides in the cytoplasm leads to an increase in their availability for PTC readthrough, as demonstrated by Du et al. in an experiment using gentamicin to induce the readthrough of a nonsense mutation in the CFTR gene [156]. These compounds are taken prior to and during aminoglycoside administration. Finally, compounds that interfere with cell death signaling are also being tested since they promote hair cell survival, which may reduce the secondary effects caused by the aminoglycosides [140].

The second generation of aminoglycosides

One of the negative aspects of using aminoglycosides as a suppression therapy is the low efficiency of the majority of these compounds, with gentamicin and G418 among those showing a better performance. Additionally, aminoglycoside antibiotics cannot be administered for long-term therapy as they may also induce bacterial resistance. To overcome the negative features of aminoglycosides and prevent toxicity, aminoglycoside derivatives have been developed. The first and second generation of these improved compounds were the NB30, and NB54 derivatives of paromomycin [53, 128, 157]. These compounds have higher readthrough activity, are less toxic than gentamicin, G418 and paromomycin [128, 158, 159], and have been demonstrated to be able to induce the readthrough of a PTC in a gene model of Usher syndrome (US), CF, DMD and Hurler syndrome (HS) [128, 157–160]. NB74 and NB84 were also designed, synthesized from G418 and tested both in vitro and ex vivo [161]. These compounds are less toxic than gentamicin and G418, and show higher PTC readthrough activity, as demonstrated in several models of CF, US, DMD and HS [161]. Furthermore, NB54 and NB84 have been effective in the readthrough of a PTC in the MECP2 gene associated with RTT [162]. Another aminoglycoside derivative with promising PTC readthrough features is TC007 [163]. TC007, a more stable and less cytotoxic compound than other aminoglycosides, is derivative from neomycin and belongs to the class of pyramycins [164]. This compound was able to restore the levels of SMN protein in fibroblasts from patients with SMA [163]. Furthermore, in a mouse model of SMA, TC007 was able to induce the readthrough of the PTC and to increase SMN protein levels in both the brain and spinal cord [163–165]. The mechanism of PTC readthrough of this aminoglycoside derivative appears to be similar to that of other conventional aminoglycosides [166]. A promising alternative synthetic aminoglycoside is NB124, also known as ELX-02 [167]. This synthetic aminoglycoside derivative has shown to be able to induce the readthrough of several PTCs in the tumor suppressor genes p53 and APC with a significantly higher efficiency than gentamicin (2–5 times higher), being able to restore the production and function of the full-length protein independently of the PTC context [137]. It has also been shown to increase CFTR mRNA levels containing PTCs and to induce the synthesis of full-length CFTR protein [168]. More recently, ELX-02 was found to have a higher safety profile associated with its readthrough properties, showing no cytotoxicity or nephrotoxicity in a cystinotic mouse model, and low renal toxicity and low ototoxicity when subcutaneously injected in healthy humans [166, 167, 169]. This compound was also shown to be 100 times more efficient in PTC readthrough than conventional aminoglycosides and is currently being tested in phase II clinical trials in patients with CF (NCT04126473) and with nephropathic cystinosis (NCT04069260). Such data suggest that the development of new readthrough compounds that have nonsense mutation suppression properties associated with a high safety profile, contrary to what was seen with conventional aminoglycosides, may now be possible.

Pharmacologically-induced readthrough of PTCs by non-aminoglycosides

The development of novel and more efficient nonsense mutation suppression agents with a safer profile is still extremely important. Herewith, different screening libraries of small molecular weight compounds have been and are still being tested. PTC124 (Ataluren or Translarna™) is a 3-[5-(2-fluorophenyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-3-yl]-benzoic acid, with the chemical formula C15H9FN2O3 and a molecular weight of 284.24 Da. PTC124 was discovered among 800,000 compounds by PTC Therapeutics during a high-throughput screen [170, 171]. These authors used a firefly luciferase reporter gene containing one PTC (UAA, UGA, or UAG) to test the ability of the compounds in the library to induce PTC readthrough. Of the 800,000 compounds, PTC124 was the most potent at restoring firefly luciferase activity at low concentrations (0.01–0.1 mM) [170]. PTC124 was also found to induce the readthrough of a nonsense mutation in several other studies. Furthermore, PTC124 proved to be dependent on the sequence context of the PTC and available mRNA levels when enhancing the readthrough of a PTC located in human bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) cDNA in cultured cells [172]. PTC124 has been shown as able to suppress numerous nonsense mutations in several disease models as shown in Table 3. Due to the positive results in PTC readthrough experiments and low toxicity obtained during the investigation phase, PTC124 was further tested in human clinical trials summarized in Table 4.

Table 3.

Summary of studies where PTC124 was shown to be a PTC suppressor in genetic disorders

| Disease | Gene/model | References |

|---|---|---|

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) | Cultured muscle cells from DMD patients | [170, 285] |

| Usher syndrome (USH) | Usher syndrome type I (USH1C) gene expressed in cultured cells and expressed in mouse retina | [158] |

| Long QT syndrome (LQTS) | Human ether-a-go-go-related (hERG) gene | [272] |

| Cystic fibrosis | Mouse model | [286] |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathway genes, BMP receptor 2 (BMPR2) and SMAD9 | [287, 288] |

| Ocular anterior segment dysgenesis, tooth agenesis, etc. | Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathway genes, bmp receptor 2 (Bmpr2) in Zebrafish model | [172] |

| Congenital aniridia | Congenital aniridia patient-derived cells | [289] |

| Mucopolysaccharidosis I (MPS I) | Mouse model | [290] |

Table 4.

Summary of clinical trials where PTC124 was tested as a PTC suppressor in genetic disorders

| Disease | Clinical trial | Conclusion | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cystic fibrosis |

Phase II ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT00351078, NCT00237380, NCT00458341, NCT00234663 |

Suppress nonsense mutations in the CFTR gene and diminish epithelial electrophysiological abnormalities | [291] |

| Cystic fibrosis |

Phase III ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT02139306, NCT02107859, NCT02456103, NCT00803205, NCT01140451 |

No significant difference between patients using PTC124 or placebo | [292, 293] |

| Cystic fibrosis |

Phase IV ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT03256968, NCT03256799 |

Change in lung function as measured by spirometry | [294] |

| Cystic fibrosis or Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) | Phase I | Safe, tolerable, with high bioavailability and low toxicity | [171] |

| DMD | Phase IIa | Positive outcome and a safety profile | [295, 296] |

| DMD | Phase III | No effect when assessing the patients using a 6 min’ walk test | [297] |

| DMD | Long-term therapy ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03179631 | Ongoing with an estimated study completion in October 2023 | [171] |

| DMD |

Phase IIa |

Terminated early because a similar study with Ataluren exhibited lack of efficacy at the high dose | [174] |

| Hemophilia A and B |

Phase II |

None of the participants had a change from baseline in plasma anti-FVIII/FIX Inhibitor Titers at day 14 | [171] |

| Methylmalonic acidemia |

Phase II |

No difference between the baseline and Day 28 and Day 29 (last day of dosing) of Cycles 1 and 2 for all testing parameters | [171] |

| Dravet syndrome |

Phase II |

Ongoing with an estimated study completion in March 2021 | [171] |

| Aniridia |

Phase II |

Ongoing with an estimated study completion in February 2022 | [171] |

Interestingly, a study reports that the response of DMD patients to PTC124 treatment depends on the patient's age and disease severity [173]. Further to PTC124 (Ataluren) conditional approval by the European Medicines Agency in August 2014, this compound was tested in non-ambulatory PTC-associated DMD patients, which was evaluated according to several clinical parameters, including cardiac function, pulmonary function and muscle strength. The results obtained have shown that Ataluren may cause a mild attenuation of disease progression without any detected toxicity or adverse effects. Although these results are very encouraging, it is extremely important to assess the Ataluren long-term impact on disease development and its clinical effects in non-ambulant PTC-associated DMD patients (NCT01009294) [174]. PTC124, contrary to other aminoglycosides and non-aminoglycosides compounds, does not present toxicity and adverse effects. In fact, PTC124 has been referred to as being well-tolerated in long-term treatments [171, 175]. Furthermore, PTC124 efficiency depends on the dose used, since it has been described as having a bell-shaped dose-response curve [10]. In addition, it does not seem to promote the readthrough of natural stop codons [170, 176]. Even though this compound has been exhaustively studied, the mechanism by which it is able to induce readthrough is not completely clarified. It is able to stimulate the incorporation of the near-cognate tRNAs at PTCs [177], but it is not still clear if its action is similar to the aminoglycoside mechanism (by interacting with A site of the ribosome) or if interacts directly with the stop codon to promote readthrough [176, 178]. Even though PTC124 seems to be an innovative and promising compound in several studies, other results see this compound as controversial. In fact, studies suggested that the first discovery of PTC124 as a nonsense codon suppressor was attributed to its properties in stabilizing the firefly luciferase used as a reporter of suppression therapy instead of inducing PTC readthrough [179, 180]. Furthermore, several studies reported the lack of suppression of PTCs using PTC124, in vivo, in vitro, and using other luciferase assay reporters [181, 182]. For example, a recent study showed that the use of PTC124 in 293 T/17 cells with mutant human BMP4 cDNA containing two different nonsense mutations did not produce significant results in either of them. However, when PTC124 was used in vivo, it was able to produce relevant phenotypic improvement associated with homozygosity for a nonsense mutation in the bmp4 alleles in Danio rerio [172]. Another study concludes the inability of PTC124 to rescue levels of UAA-mutated mRNA in the choroideremia (CHM) system, UAA nonsense-carrying human fibroblasts, and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium, even when associated with NMD and proteasome inhibition [182]. In 2012, Harmer et al. showed that PTC124 was unable to rescue the function of the nonsense mutations R518X-KCNQ1 and Q530X-KCNQ1 that cause LQT1 (long-QT syndrome type 1) in HEK-293 cells [183]. In 2016, PTC124 was shown to be unable to suppress the premature stop codons R1638X and W156X in sodium channel gene SCN5A in human-induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)–derived cardiomyocytes [184]. With such uncertain results obtained with PTC124 for the treatment of PTC-associated disorders, arises the necessity of identifying other readthrough compounds.

Another non-aminoglycoside, negamycin, or 2-(3,6-diamino-5-hydroxyhexanoyl)-methylhydrazino] acetic acid, is an antibiotic identified in 1970 by Hamada et al. [185]. It was reportedly a low toxicity compound that is very effective against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [185, 186]. The mechanism of action of negamycin has been described as an interaction with both the small and large subunits of the ribosome. In the small subunit, negamycin contacts with the 16S rRNA and the anticodon loop of the A-site tRNA [187]. On the prokaryotic 50S ribosomal subunit, it is able to bind to the wall of the nascent chain exit tunnel [188] and to form bonds with the anticodon of the A-site tRNA [187]. The first association between negamycin and the readthrough of a stop codon was hypothesized in 1976 by Uehara [189]. Its readthrough properties have been studied in several human diseases, such as congenital muscular dystrophy [177], DMD [177, 190], CF [191], and colon cancer [192]. Several analogs of negamycin were synthesized and tested by Akihiro et al. in their ability to promote the readthrough of a PTC in a DMD mouse model [193]. Among all the tested analogues, 11b was the most efficient and least toxic, indicating that it might be used as a readthrough compound in the long-term treatment of DMD [193]. Recently, a novel negamycin derivative TCP-1109 (13x) was proved to be twice as potent as gentamycin in a dose dependent manner [194].

Tylosin, identified as a readthrough agent, is a macrolide antibiotic composed of a 16-membered branched lactone, and three deoxy-sugar residues [195]. Tylosin binds to the E site of the 50S ribosome, to the nascent peptide exit tunnel, inhibiting protein synthesis or inducing the readthrough of a PTC [196, 197]. It is able to induce the readthrough of a PTC in the APC gene and to improve tumorigenic symptoms in a mouse model [129]. According to these results and due to its low toxicity and high readthrough efficiency, tylosin has been suggested as a readthrough agent in a future therapy for patients with colorectal cancer [129]. Among readthrough compounds, their ability of the macrolides spiramycin and josamycin to induce the readthrough of a PTC in mouse models for APC-mediated colon cancer was also studied [198]. Both spiramycin and josamycin bind to the 50S bacterial ribosome to inhibit translation [198]. Additionally, using high-throughput screening (HTS) assays on a library of 34000 compounds, twelve low molecular weight compounds were identified as being able to induce the readthrough of a nonsense mutation in an A-T genetic model. Of these twelve compounds, the readthrough compound (RTC) 13 and RTC14 showed the ability to induce PTC readthrough in the ATM gene and the translation of full-length and functional ATM protein in A-T cell models [199], and to induce the readthrough of a PTC and restore dystrophin full-length and functional protein in cells isolated from a mouse model for DMD [200]. Furthermore, the results of a study showed that RTC13 may be more effective than gentamicin when inducing the readthrough of a PTC in the dystrophin gene [201]. However, these compounds were not able to suppress hemophilia A associated PTCs otherwise responsive to either gentamicin or geneticin, giving experimental evidence of genetic context dependence of nonsense suppression by readthrough compounds and of factors predicting responsiveness [119]. Nevertheless, the mechanisms by which RTC13 and RTC14 bind to the ribosome and induce PTC readthrough are not yet known. In addition to these novel PTC readthrough compounds discovered by HTS, two novel compounds able to induce the readthrough in all three stop codons were identified among a collection of 36000 small molecular weight compounds, GJ071 and GJ072 [201]. RTC204, RTC219, NV2445, NV2907, NV2909, NV2899 and NV2913 were among several other compounds identified by HTS with PTC readthrough properties similar to PTC124, gentamicin or G418 [199, 202].

An interesting PTC readthrough compound is a nucleoside analog isolated from the mushroom called clitocine, which can be incorporated into RNA molecules during transcription. It has been shown that when clitocine is in the third position of a PTC, it allows PTC readthrough, as shown by the production of a functional full-length p53 protein in both cell culture and in xenograft tumors carrying p53 nonsense-containing genes [203]. A similar PTC readthrough compound also isolated from the mushroom is 2,6-diaminopurine (DAP). This compound was able to induce the readthrough of a UGA PTC located in the TP53 gene, being able to restore p53 protein levels in Calu-6 cancer cells and decrease tumor growth in a mouse model [204]. DAP was described as being able to induce the readthrough of a UGA PTC into a tryptophan codon [204]. Another clinically approved drug selected from an HTS with PTC readthrough features is escin. Escin is a natural herbal compound that was shown to be both an efficient readthrough agent and an inhibitor of the NMD mechanism in cell models of CF [205]. This dual feature contributes to the increase of mRNA levels available for PTC readthrough and so, increases escin nonsense readthrough efficiency and its potential as a future clinical therapy [205]. Among the most efficient readthrough compounds found in an HTS of 1200 small molecules is amlexanox, an anti-allergic and anti-inflammatory compound able to induce the efficient readthrough of a PTC at mRNAs expressed in human cultured cells [206]. Amlexanox was able to induce the readthrough of 8 of 12 PTCs in the COL7A1 gene and to induce the translation of the full-length protein in cells derived from patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB) [207]. Amlexanox is also efficient in inducing the readthrough of a PTC in the enzyme aspartylglucosaminidase (AGA) mRNA and therefore increasing the enzyme activity level expressed in aspartylglucosaminuria patient cells, and so being a potential therapy for patients with lysosomal storage disorders [208]. Furthermore, this drug inhibits the NMD mechanism, which contributes to the increase of mRNA levels available for PTC readthrough and thereby increases amlexanox nonsense readthrough efficiency [206]. Given the duality of this compound in both PTC readthrough and NMD inhibition, amlexanox can be further investigated as a therapeutic approach for the treatment of genetic diseases caused by nonsense mutations, where the NMD is a strong modulator of its phenotype [206]. Although the positive results previously described may indicate amlexanox as a potential compound to be used as a therapeutic approach for several genetic diseases, other studies may indicate opposite results. A recent study used three models of McArdle disease associated with the PYGM p.R50X nonsense mutation to demonstrate that amlexanox does not have PTC readthrough properties under the conditions studied [209]. The constructs used were: a gene construct transiently transfected into HeLa cells, a gene construct stably transfected into HEK293T cells and skeletal muscle cells cultured from a McArdle mouse model. However, as neither Ataluren, RTC13 or G418 were able to induce readthrough of PTCs in the three McArdle models, the authors hypothesize several factors for this lack of PTC readthrough, such as dosage and incubation times or the sequence context of the chosen PTC [209]. These differences in the obtained results from different studies suggest the need for discovering and developing new readthrough compounds with improved and robust characteristics. A summary of aminoglycosides and non-aminoglycoside readthrough compounds and their readthrough properties in several disease models is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of studies where nonsense readthrough was observed using small molecule compounds (aminoglycosides and non-aminoglycosides)

| Compound | Disease model | References |

|---|---|---|

| Gentamicin | See Table 1 | See Table 1 |

| G418 | See Table 2 | See Table 2 |

| Kanamycin | Xeroderma pigmentosum group C (XPC) | [124] |

| Paromomycin | XPC, eye diseases, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), Rett syndrome, Ataxia-Telangiectasia (A-T), Cystic fibrosis (CF), Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)-mediated colon cancer, Becker's muscular dystrophy | [57, 124–129] |

| Neomycin | XPC | [124] |

| Amikacin | p53-associated tumor, CF, Rett syndrome (RTT), DMD and Becker's muscular dystrophy | [57, 126, 130–132] |

| Streptomycin | Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), RTT | [126, 133–135] |

| NB30, NB54 | Usher syndrome, CF, DMD and Hurler syndrome, RTT | [128, 158–160, 162] |

| NB74, NB84 | CF, Usher syndrome, DMD and Hurler syndrome, RTT | [161, 162] |

| TC007 | SMA | [163, 165] |

| NB124 | p53-associated tumor, APC-mediated colon cancer, CF | [137, 168] |

| PTC124 | See Tables 3 and 4 | See Tables 3 and 4 |

| Negamycin | Congenital muscular dystrophy, DMD, CF, and colon cancer | [177, 190–192] |

| Negamycin analogue 11b | DMD | [193] |

| Tylosin | APC-mediated colon cancer | [129] |

| Spiramycin and josamycin | APC-mediated colon cancer | [298] |

| RTC13 and RTC14 | A-T, DMD | [199–201] |

| Clitocine | p53-associated tumor | [203] |

| 2,6-diaminopurine | p53-associated tumor | [204] |

| Escin | Cystic fibrosis | [205] |

| Amlexanox | Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, aspartylglucosaminuria | [207, 208] |

PTC readthrough by nucleic acid-based methodologies

In an attempt to obtain alternatives to small molecules for PTC readthrough, several nucleic-acid-based approaches have been developed, including those based on suppressor tRNA, pseudouridylation, adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR)-catalyzed RNA editing, and CRISPR technology.

Suppressor tRNAs

Suppressor tRNAs are derived from natural tRNA genes, however, they contain an anticodon mutation that allows them to read the nonsense stop codon on the mRNA, allowing PTC readthrough [210]. The transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms of suppressor tRNAs are similar to those of natural tRNAs [10, 210]. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases recognize and charge suppressor tRNAs, although usually with lower efficiency than the natural tRNAs [10]. In 1982, Temple et al. described the use of a suppressor tRNA as a potential therapeutic strategy in homozygous β-thalassemia [211]. Using site-specific mutagenesis, a human tRNALys gene was mutated and transcribed into an amber suppressor tRNA. In fact, the tRNALys anticodon was mutated to CUA, so the UAG codon could be readthrough and lysine would be introduced into the nascent β-globin peptide in the position of the nonsense mutation at codon 17 [211]. Suppressor tRNAs have been used in several studies, both in vitro and in vivo, aiming to suppress PTCs associated with Ullrich Congenital Muscular Dystrophy, DMD, CF [212–214] and XPA [215]. In 2014, Bordeira-Carriço et al. demonstrated for the first time the benefit of the use of suppressor tRNAs in the readthrough of a PTC in hereditary gastric cancer [216]. An arginine suppressor tRNA vector was developed by site-directed mutagenesis to suppress a nonsense mutation in the E-cadherin gene associated with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) syndrome [216]. Recently, a high-throughput, cell-based assay was developed to identify anticodon edited tRNAs (ACE-tRNA) able to induce PTC readthrough that have a similar role in translation as a natural tRNA, being recognized and charged by the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and interacting with eEF-1α during amino acid incorporation into the nascent peptide [217]. A similar strategy is in development by ReCode Therapeutics with the aim of inducing accurate readthrough of nonsense mutations in the CFTR mRNA and restoring functional full-length CFTR protein. The strategy involves the delivery of a suppressor tRNA (RCT101) into cells by a patented nanoparticle system. RCT101 is being studied in patients with G542X/G542X and F508del/G542X CFTR genotypes with promising results so far [218]. Although the use of suppressor tRNAs could constitute a sustainable therapeutic option for PTC-associated diseases as it presents a relatively high efficacy, the toxicity associated with stable expression of suppressor tRNAs due to, for example, immune rejection, has delayed the development of these therapies. In fact, there are several obstacles that need further investigation, such as the toxicity associated with the possibility of readthrough of natural stop codons, suppressor tRNA non-specificity, competition between natural and suppressor tRNAs, loss of suppressor tRNA activity, poor efficiency of delivery to the target cells, toxicity of uncontrolled expression in long-term therapies, and also the previously mentioned conventional suppression therapy obstacles, such as PTC identity and context, mRNA levels, and the role of the NMD mechanism in the readthrough of PTCs [10, 217, 219]. Thus, to use suppressor tRNAs as a suppression therapy for nonsense codons associated diseases, further investigation and several improvements are crucial.

Pseudouridylation

Pseudouridylation consists of the isomerization of the ribonucleoside uridine to 5-ribosyl isomer pseudouridine (the Greek letter abbreviation psi is Ψ), resulting in an extra hydrogen bond donor. Pseudouridylation is the RNA post-transcriptional modification that mainly occurs in the cell. Pseudouridylation can occur by two independent mechanisms. One involves the enzymes called pseudouridine synthases (PUSs) that alone recognize the substrate and catalyze the isomerization of uridine to pseudouridine. The other is an RNA-guided pseudouridylation by a family of box H/ACA RNPs, each of which consists of a unique guide RNA (box H/ACA RNA) and four common core proteins (Cbf5/NAP57/Dyskerin, Nhp2/L7Ae, Nop10, and Gar1) [220–222]. Pseudouridylation has been associated directly and indirectly with alteration of RNA structure, stress conditions and human diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and dyskeratosis [223]. As pseudouridylation occurs through the base-pairing interactions between the guide sequence of the box H/ACA RNA and the target RNA with a minimum of 8-base pairs guide-subtract base-pairing interaction, a site-specific pseudouridine is introduced into the RNA of interest [224]. Since the uridine residue occurs in all the three nonsense codons (UAA, UGA, UAG), Karijolich and Yu showed for the first time that pseudouridylation of a PTC (modification of UAA, UAG or UGA to ΨAA, ΨAG or ΨGA, respectively) could result in PTC readthrough and translation of a full-length protein both in vitro, using CUP1-PTC as a reporter, and in vivo using both CUP1-PTC and TRM4-PTC reporter genes and derived H-ACA RNA specific guides in yeast [47]. Furthermore, it has been hypothesized that the PTC readthrough of pseudouridylated PTCs is specific and occurs with an efficiency of 74–100%, in contrast to non-pseudouridylated PTCs that have a low basal PTC readthrough efficiency (~ 1%) [47, 225]. Additionally, the suppression of a PTC by pseudouridylation seems to be independent of the sequence context of the PTC as neither the upstream sequence nor the nucleotides immediately nearby the PTC seem to have an effect on its readthrough, which differs from the conventional therapies discussed so far [226]. The results achieved to date show that this strategy combines both the high efficiency of the PTC readthrough with the expected low toxicity, high specificity and sequence independence, that has not been achieved so far with either conventional or novel suppressor compounds or suppressor tRNAs. The potential for artificially synthesized specific box H/ACA guide RNAs to be used as a therapeutic strategy for PTC- associated diseases may be an important breakthrough in the suppression therapy field.

RNA editing

RNA editing was discovered by Benne et al. in trypanosomes [227]. It is an RNA (mRNA, tRNA, rRNA) process that comprises insertion or deletion of nucleotides that alters the length of the RNA or substitutes nucleotides within the RNA [228]. RNA editing is highly regulated and it is physiologically catalyzed by the family of RNA editases, such as apolipoprotein B mRNA editing catalytic polypeptide-like (APOBEC), and adenosine deaminases that acts on RNA (ADAR) enzymes. It results in the recoding of amino acids, alters splicing processes, changes miRNA specificity and defines stability and levels of RNA. RNA editing is associated with several diseases, such as cancer and metabolic disorders (reviewed in [229, 230]).

RNA editing was used as a strategy to induce the readthrough of PTCs through a natural mechanism using ADARs as site-directed mutagenesis catalyzers in several studies [231–233]. ADARs are responsible for converting adenosines into inosines, that are read as guanosines, altering the translation process [232–234]. This mechanism may be used as a tool to target adenosines within the nonsense stop codons (UGA, UAA and UAG), that when edited, promote the readthrough of the PTC and allow translation to continue. This may be achieved by redirecting endogenous ADAR to a target by creating a dsRNA structure using an RNA oligonucleotide, or by artificially replacing the catalytic domain of the ADAR to be able to bind to specific guide RNA, using i.e. SNAP-tags, Lambda N protein (λN) and the BoxB RNA hairpin, MS2 systems or the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) Cas13b system (these mechanisms are extensively reviewed in [230]). These mechanisms have been studied in several different reporters [232, 235] and disease models. For example, in a study of suppression therapies for CF, the authors engineered a site-directed RNA editase and specific RNA guides that would support efficient and specific editing that could lead to PTC readthrough in CFTR (W496X) both in vitro and in vivo and the restoration of CFTR protein function in Xenopus oocytes [236]. Another study associated with Parkinson’s disease showed the use of synthetic guide RNAs to be 65% efficient in re-addressing the human ADAR2 to edit the PTC UAG into tryptophan (UIG) in the PINK1 gene (W437X) in HeLa cells, thereby rescuing protein function [231]. In a study of KRAS and STAT1 signaling related diseases, the authors were able to edit the target RNA nucleotide adenosine into inosine using a SNAP-ADAR guided by a specific guide RNA in 293 Flip-In cells with 90% efficiency and high precision [233]. In recent studies, authors have used CRISPR-Cas13 systems as a tool to efficiently promote RNA editing [237, 238]. This strategy comprises the elimination of Cas13 RNA nuclease activity and the fusion of the inactive Cas13 with the N-terminus of ADAR1 or 2, serving as a structure to bind the guide RNA and the target RNA [230, 237, 238].

RNA editing may therefore be a potential therapy for genetic diseases related to nonsense codons as it appears to be highly effective. However, it still presents off-target effects therefore necessitating further investigation and the development of new and improved systems that may soon be translated into applied therapeutic approaches for such disorders.

Gene editing and CRISPR/Cas9 strategy

The concept of gene editing was originated in 1970 and allowed researchers to understand the connection between a single gene and a disease and to apply this tool not only in fundamental and clinical research but also in biotechnology, industry and medical therapy [239]. Targeted DNA alterations were first attempted in 1989 when Rudin et al. were able to introduce a novel cloned DNA into the genome by homologous recombination (HR) by targeting DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs) [240]. Even though HR is extremely precise in introducing specific mutations, it is not efficient [239] and therefore, this method cannot be used as a gene therapy [241]. To overcome this challenge, new approaches have been developed and optimized. In 2005, Urnov et al. showed that the used of zinc-finger (ZF) proteins with customized sequence-specific DNA-binding domains can be fused to a nuclease, which will recognize a site-specific sequence and introduce the desired novel DNA sequence [242]. This approach has disadvantages related to low specificity and sequence context dependence [242]. Later in 2009, Boch et al. discovered that transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) similar to the ZF, can bind the DNA via a customized domain and cleave the site-specific sequence when fused to a programmed nuclease [243]. This strategy is sequence context-dependent, has low efficiency, and is time-consuming and expensive, which are disadvantages when developing a new suppression therapy [239, 244]. Interestingly, clustered regularly interspersed short palindromic repeats (CRISPRs) had already been discovered in 1978 in E. coli, but only recently was their editing utility in association with the Cas9 system described [239]. The CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two components: a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) and a Cas9 nuclease [245–247]. The mechanism involves a 20-base pair guide RNA with an upstream short sequence compatible with Cas9 that recognizes and binds to the targeted genomic DNA and recruits the Cas9 endonuclease to induce a double-stranded cleavage in the site-specific sequence of the genomic DNA [245–248]. The double-stranded break is then repaired either by non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) or by homology-directed repair (HDR), which leads to genetic modifications, such as deletions (knock out) or insertions (knock-in) in the target DNA [249]. In fact, it was in 2012 that Doudna, Charpentier and their co-workers isolated and identified the components of CRISPR-Cas9 system, highlighting for the first time its potential in genome editing [250]. This work allowed these two authors to be honored with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 2020 [250, 251]. The advantage of this gene therapy approach is the fact that, contrary to other therapies, CRISPR/Cas9 eliminates the dysfunctional copy of the gene from the patient cells [246, 252]. The association between gene editing using CRISPR/Cas9 and the suppression of nonsense codons has been intensively studied and explored. Long et al. used this system to correct nonsense mutations in the dystrophin gene in the germline of the DMD mdx mouse model [253]. Another example is the work performed by Jo et al., in which the authors used the CRISPR/Cas9 mechanism to correct a PTC in the Rpe65 gene and improve retinal function in a mouse model for human Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) [254]. A recent study showed the benefits of CRISPR/Cas9 not directly in suppression of PTCs, but in NMD inhibition. Using a gene editing strategy, the authors were able to successfully suppress the NMD mechanism in the degradation of the CFTR mRNA containing a PTC, increasing the levels of mRNA available for readthrough induced by a second suppressor compound [255]. The main challenge of the CRISPR/Cas9 system is the fact that while the phenotype of some diseases may be alleviated through the correction of a small number of cells, others may need a more extensive correction [256]. Other challenges, especially for long-term use, are its off-targets and toxicity, the specificity of the therapeutic approach, optimization of delivery, bioavailability, robustness, and others. All these factors need to be evaluated in preclinical studies in large-animal models of disease. However, it also has great efficiency, it can be used in any model and it is easily programmable, therefore potentially representing the future of genetic engineering [255–257].

Strategies to enhance suppression therapy efficacy

Suppression therapy has shown promising results in several constructs, animal models, and clinical trials. However, there are several obstacles in the use of suppressor compounds and the results obtained are variable among several diseases and studies, challenging the establishment of a suppression therapy for nonsense-mediated diseases [53, 117]. Even though these differences can be associated with technical variability, suppression therapy also depends on the context sequence and the identity of the PTC, as was discussed above. Moreover, the incorporated amino acid is not specific, and so may alter the protein structure, function and/or stability [117, 119]. Additionally, the level of mRNA is also variable depending on the location of the PTC in the mRNA and activation of the NMD mechanism [84, 258]. While NMD degrades the mRNA containing a PTC, it also decreases the efficiency of the suppressor compound. Nonetheless, it is difficult to establish the ideal conditions for the treatment of the disease in in vivo models, as in many cases the amount of functional protein necessary for a beneficial therapeutic result is unknown [259]. Due to all these limitations, there is a need to create new strategies to improve suppression therapy as a therapeutic approach to genetic diseases caused by PTCs.

Inhibition of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay