Abstract

Emerging evidence shows that m6A, one of the most abundant RNA modifications in mammals, is involved in the entire process of spermatogenesis, including mitosis, meiosis, and spermiogenesis. “Writers” catalyze m6A formation on stage-specific transcripts during male germline development, while “erasers” remove m6A modification to maintain a balance between methylation and demethylation. The different functions of RNA-m6A transcripts depend on their recognition by “readers”. m6A modification mediates RNA metabolism, including mRNA splicing, translation, and degradation, as well as the maturity and biosynthesis of non-coding RNAs. Sperm RNA profiles are easily affected by environmental exposure and can even be inherited for several generations, similar to epigenetic inheritance. Here, we review and summarize the critical role of m6A in different developmental stages of male germ cells, to understand of the mechanisms and epigenetic regulation of m6A modifications. In addition, we also outline and discuss the important role of non-coding RNAs in spermatogenesis and RNA modifications in epigenetic inheritance.

Keywords: m6A, RNA modification, Spermatogenesis, Sperm RNA, Epigenetic inheritance

Introduction

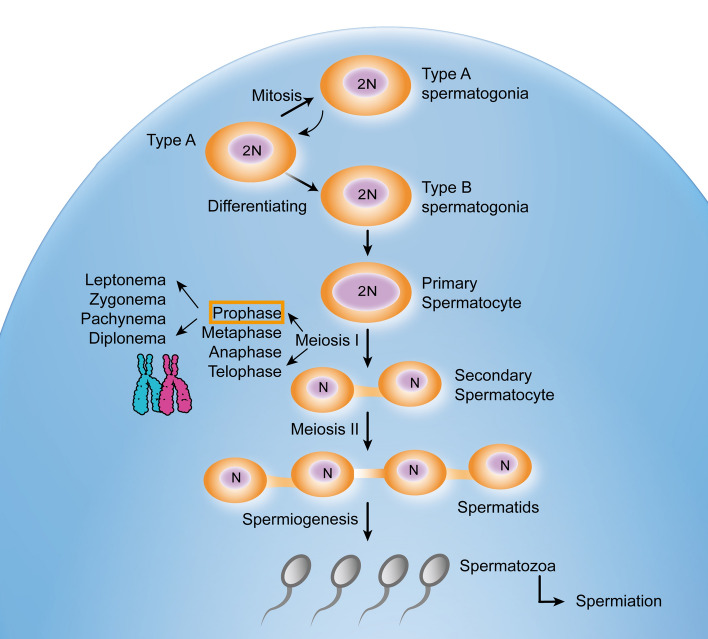

In mammals, spermatogenesis is a highly sophisticated and complex process that can be divided into four stages: mitosis, meiosis, spermiogenesis, and spermiation [1–3]. In the mitosis phase, A-single (As) spermatogonia are capable of self-renewal, amplifying the stem cell pool, and differentiation to undergo spermatogenesis. The As spermatogonia differentiate into two A-paired (Ap) spermatogonia and then undergo repeated mitotic division to form chains of 4, 8, 16, and even 32 A-aligned (Aal) spermatogonia. These spermatogonia, including As, Ap, and Aal, are connected together through an intercellular bridge arising from incomplete cytokinesis and are defined as undifferentiated spermatogonia. Undifferentiated spermatogonia undergo an irreversible transition to differentiating A1 spermatogonia (A–A1 transition), followed by five synchronized cell divisions to form A2, A3, A4, A-intermediate (AIn) and type B spermatogonia, which differentiate into preleptotene spermatocytes that enter the meiosis phase [2, 4]. The meiosis phase consists of a single round of meiotic DNA replication and two consecutive rounds of chromosome segregation, meiosis I, and meiosis II. Double-strand break (DSB) formation, recombination and synapse of homologs are hallmark events during meiotic prophase I ensuring proper segregation of homologs during meiosis I. Meiotic prophase I can be divided into leptonema (SPO11-induced DSB formation), zygonema (synapsis initiation), pachynema (synapsis completed) and diplonema (desynapsis and chiasmata) according to morphological characteristics [3]. During meiosis II, sister chromatids separate to produce haploid round spermatids and then enter the spermiogenesis stage. There are several major events in the development of highly specialized spermatozoa during spermiogenesis: formation of the acrosome and flagellum, chromatin remodeling, and removal of the residual body. The development of mouse spermatids is subdivided into 16 steps based on the morphology of the nuclei and acrosome [5]. Steps 1–8 are characterized by early round spermatids; whereas, the later steps (steps 9–11) are characterized by intermediate and late spermatids with elongating nuclei. In elongated spermatids (steps 12–16), transcription terminates due to chromatin compaction. Finally, mature spermatozoa are released into the seminiferous tubule, through a process termed spermiation [1] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

A schematic diagram of mouse spermatogenesis

Epigenetic regulation (DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNAs) plays an important role in spermatogenesis, including spermatogonia stem cell amplification to maintain stem cell pools, meiosis to form haploid cells, and spermiogenesis to develop into mature spermatozoa [6, 7]. Similar to DNA methylation, there are various types of methylation modifications on mRNA, such as m6A, 5-methylcytosine (m5C), N7-methylguanosine (m7G), N6-methyl-2′-O-methyladenosine (m6Am), and 2′-O-methylation, which comprise the emerging field “RNA Epigenetics” [8]. m6A plays an important role in gametogenesis [9–13], embryonic development[14–16], sex determination [17], and response to environmental insults [18] by affecting the splicing [19], translation [20, 21], and stability [22] of mRNA, as well as the maturity and biosynthesis of non-coding RNAs [23–25]. The importance of RNA-m6A modification and epigenetic regulation mediated by m6A in spermatogenesis has attracted widespread attention, as discussed in the following sections.

The functions of m6A-associated proteins in spermatogenesis

Although m6A was discovered as early as 1975 [26], its biological function and clinical application have received increasing attention with the development of epigenetics and the application of high-throughput sequencing technology. There are three m6A-associated proteins: “writer” (methyltransferase), “eraser” (demethylase), and “reader” (decoder). “Writer” is a multicomponent m6A methyltransferase complex (MTC), which introduces m6A into mRNAs. The main components of “writer” include METTL3, the core catalytic subunit; METTL14, the scaffold [27, 28]; and WTAP, the regulatory subunit, ensuring the stability and localization to nuclear speckles [29]. “Eraser” includes fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and alkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5), which are responsible for removing m6A modification. The decoder "reader" (YTH family) recognizes m6A modifications and has complex biological functions [30].

m6A writers in spermatogenesis

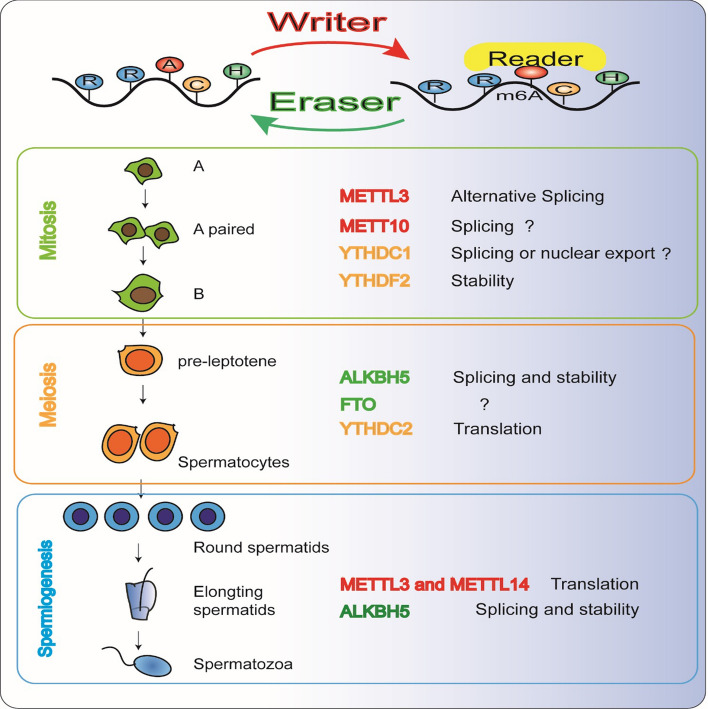

Methyltransferase complexes play an important role in mammalian spermatogenesis, including spermatogonial stem cell differentiation, meiosis, and spermiogenesis (Fig. 2). Mettl3 is highly conserved in eukaryotes from yeast to humans. In Arabidopsis [31], inactivation of methyltransferase results in failure of the developing embryo to progress past the globular stage. In yeast [32], the deletion of Ime4 (homolog of Mettl3) causes failure to initialize meiosis and sporulation. In zebra fish [11], Mettl3 mutation alters the expression profile of hormone synthesis genes, disrupts gametogenesis, and reduces fertility. In mice, inactivation of Mettl3 or Mettl14 with Vasa-Cre in early male germ cells causes m6A loss and excessive spermatogonial stem cell proliferation and depletion, disrupting spermatogenesis [12, 33]. Mettl3 and Mettl14 double-knockout mice showed severely reduced sperm motility, flagellar defects, and abnormal sperm head abnormalities, similar to the human oligo-astheno-teratozoospermia (OAT) syndrome [33]. In humans [34], METTL3 mediates higher m6A levels in sperm RNA and is considered a high-risk factor for asthenozoospermia.

Fig. 2.

The function of m6A-associated proteins in spermatogenesis. “Writers” catalyze m6A formation on stage-specific transcripts during male germline development while “erasers” remove m6A modification to maintain a balance between methylation and demethylation. The different functions of m6A transcripts (splicing, translation, and degradation) depend on their recognition by “readers.” Abnormal expression of m6A-associated proteins in different developmental stages results in male infertility

METTL16 is a non-classical methyltransferase that targets pre-mRNAs and various non-coding RNAs [35], such as MAT2A hairpins and spliceosomal U6 snRNA [36]. METTL16-mediated modifications may play an important role in regulating splicing events. In Caenorhabditis elegans, METT10 (a homolog of METTL16) inhibits the specification of germ-cell proliferative fate [37]. METT10 also promotes vulva, somatic gonad, and embryo development and ensures meiotic development of these germ cells do differentiate. However, whether METTL16 plays an important role in mammalian gametogenesis remains unclear. Additional studies are needed to explore the function and mechanism of “writer” in germ cells.

m6A erasers in spermatogenesis

FTO [38] and ALKBH5 [39] can remove the methyl group of m6A from RNA both in vitro and in vivo. FTO and ALKBH5 are highly expressed in the testis, and both are localized to nuclear speckles [40]. ALKBH5 co-localizes with mRNA processing factors that play an important role in alternative splicing [39]. FTO-dependent demethylation of m6A also regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis [41] (Fig. 2). Alkbh5-deficient male mice are characterized by impaired fertility resulting from apoptosis, which affects meiotic metaphase stage spermatocytes [39]. Dysfunction may be related to the interaction between ALKBH5 and nuclear speckle proteins to regulate RNA metabolism [39]. Another study showed that ALKBH5-mediated m6A is essential for correct splicing of transcripts with a longer 3′UTR in spermatocytes and round spermatids [42]. m6A marks the 3′-UTRs of longer mRNAs destined to be degraded during spermiogenesis. Global shortening of 3′-UTRs to enhance translational efficacy and fast turnover through selective degradation of longer 3′-UTR transcripts is essential for spermiogenesis. In short, ALKBH5-dependent m6A is required for the meiotic and haploid phases of spermatogenesis by controlling the splicing and stability of mRNAs. Genetic mutations in human FTO are significantly associated with reduced semen quality [43]. The discovery of two missense mutations and a genetic variant of FTO suggests that aberrant demethylation of messenger RNA is a risk factor for reduced male fertility [43].

m6A readers in spermatogenesis

The m6A function is mediated by the ‘‘reader’’ protein family, which carries a YTH (YT521-B homology) domain. In addition to providing an aromatic cage structure to accommodate m6A modification [30], the YTH protein can also modulate RNA structure (acting as methylation-dependent RNA switch), affecting RNA stability, and splicing [44]. It is worth noting that recent studies have shown that YTHDC2 [45, 46], YTHDC1 [9], and YTHDF2 [47], play an essential role in spermatogenesis (Table 1).

Table 1.

The functions of m6A-associated proteins in spermatogenesis

| m6A-associated proteins | Species | Function in germ cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| METTL3/METTL14 | Arabidopsis | METTL3 and METTL14 ensure the developing embryo to progress past the globular stage | [31] |

| Yeast | IME4 (homologue of METL3) ensures initialization of meiosis and sporulation | [32] | |

| Zebra fish | Mettl3 regulates hormone synthesis in gametogenesis and protects fertility | [11] | |

| Mouse | METTL3 and METTL14 ablation showed spermatogonial stem cells excessive proliferation and disrupted spermatogenesis | [33] | |

| Human | Higher m6A methylation levels in sperm RNA are considered a high- risk factor for asthenozoospermia | [34] | |

| METTL16 | Caenorhabditis elegans | METT10 (a homolog of METTL16) inhibits the specification of germ-cell proliferative fate | [37] |

| ALKBH5 | Mouse | ALKBH5-dependent m6A is required for meiotic and haploid phases of spermatogenesis by controlling both splicing and stability of mRNAs | [42] |

| FTO | Human | FTO genetic mutations are significantly associated with reduced semen quality | [43] |

| YTHDC2 | Mouse and Drosophila | YTHDC2-MEIOC complex is essential for meiosis by promoting translation | [48] |

| YTHDC1 | Mouse | Ythdc1 knockout mice showed a Sertoli-only phenotype in spermatogenic tubules | [9] |

| YTHDF2 | Mouse | YTHDF2 regulates spermatogonia migration and proliferation by affecting the stability of m6A-containing transcripts | [47] |

YTHDC2 is the largest YTH domain-containing protein and the only member of the family that contains helicase domains. YTHDC2 is highly expressed in testicular germ cells and is essential for meiosis because it promotes translation by recognizing m6A [45]. Ythdc2 missense mutations in germ cells cause germ cells to enter meiosis, but proceed prematurely to aberrant metaphase and apoptosis [48]. In addition, YTHDC2 has been reported to interact with the essential meiosis-specific protein MEIOC [49]. Bgcn-Bam (YTHDC2-MEIOC homolog in Drosophila) is required autonomously for mitotically dividing spermatogonia to stop meiosis initiation and spermatocyte differentiation [48]. This indicates that gene expression regulated by the YTHDC2-MEIOC complex is an evolutionarily ancient strategy that controls germline transition into meiosis.

The nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 is essential for maintenance of male spermatogonia development in mice [9]. Ythdc1 knockout mice showed a Sertoli-only phenotype in seminiferous tubules. In addition, YTHDC1 facilitates the nuclear export of m6A-containing mRNAs through SRSF3 and NXF1 [50]. Tyrosine phosphorylation of YTHDC1 regulates its intra-nuclear localization, thereby modulating its effects on alternative splicing [51]. The role of YTHDC1 in regulating spermatogenesis requires further investigation.

In recent years, YTHDF2 has been reported to play an important role in neural cancer development [52], cancer progression [53], and maternal mRNA clearance [54]. Recently, an in vitro experiment indicated that YTHDF2 may regulate spermatogonia migration and proliferation by affecting the stability of m6A-containing transcripts [47]. In addition, miR-145 modulates expression of YTHDF2 by targeting its mRNA 3′-UTR, which inhibits the proliferation of liver cancer cells [53]. The regulatory effect of microRNA (miRNA) on the "reader" undoubtedly increases the complexity of the functional study of m6A.

m6A function in testicular somatic cells

In addition to playing an essential role in spermatogenic cells, m6A can also participate in spermatogenesis by affecting the function of testicular somatic cells. In Sertoli cells, m6A and its “writer” WTAP are essential for sustaining the spermatogonial stem cell pool [55]. Loss of WTAP in Sertoli cells results in infertility and progressive loss of spermatogonial stem cell population [55]. In addition, exogenous Vitamin C supplementation decreases the level of global nucleic acid methylation (including DNA methylation and m6A RNA modification) in porcine immature Sertoli cells, which promotes the reproduction function [56]. In Leydig cells, m6A mRNA methylation was reported to regulate testosterone synthesis by modulating autophagy [57]. Furthermore, studies have shown that m6A and eraser “FTO” may be involved in environmental toxin-induced Leydig cell apoptosis [18, 58].

Non-coding RNAs in spermatogenesis

Non-coding RNAs, as epigenetic regulators, play an important role in spermatogenesis. Among them, miRNAs, circular RNAs (circRNAs), PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), tRNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs), and rRNA-derived small RNAs (rsRNAs) exert their functions to control the normal development of male germ cells at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and translational levels. We will summarize and discuss the functions of those non-coding RNAs in spermatogenesis in the following sections:

miRNA

The classic processing of mature miRNA s (22nt) includes two steps: an original long transcript (primary miRNA) is processed in the nucleus by a microprocessor complex consisting of the RNA-binding protein DGCR8 and ribonuclease type III DROSHA to form a 60–70nt stem-loop structure (pre-miRNA). The pre-miRNA is cut by DICER in the cytoplasm to form one mature miRNA, which is incorporated into the miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC) to recognize the 3′-UTR of target mRNA and promote mRNA degradation or inhibit translation [59]. In recent years, miRNAs have been found to regulate various biological processes, such as cancer, in a tissue- and developmental-specific manner [60]. Notably, as an important physiological process, spermatogenesis is also regulated by miRNAs to some extent [61]. miRNAs are abundantly enriched during the active transcription of meiotic genes in male germ cells, especially in pachytene spermatocytes and round spermatids [62]. Many genes, such as Rsbn1, participate in spermatogenesis and are involved in the regulation of translation by miRNAs [62]. In addition, miRNA clusters (miR-34b/c and miR-449a/b/c) are indispensable for spermatogenesis and male efferent ductule ciliogenesis [63, 64]. Proteins involved in miRNA processing, such as DGCR8 and DROSHA, are essential for spermatogenesis and male fertility in mice [65]. There is increasing evidence that abnormal expression of miRNAs is closely related to spermatogenic disorders in humans. For instance, compared to fertile men, the expression of miR-141 (targeting CBL and TGFβ2) and miR-7–1-3p (targeting RBL and PIK3R3) are significantly increased in non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) patients[66], and may serve as clinical biomarkers in the future.

In addition to miRNAs, endogenous small interfering RNAs (endo-siRNAs) can serve as epigenetic regulators and be involved in spermatogenesis [65]. Although there are many similarities between endo-siRNA and miRNA, such as 22nt length, requiring DICER for processing and the same function, the endo-siRNA processing is independent of the microprocessor. Thus, the role of endo-siRNA in mammalian spermatogenesis requires further study.

circRNA

Circular RNA (circRNA), a new class of non-coding RNA, is characterized by a back-splicing mechanism without poly-A tails and 5′ caps. The biosynthesis efficiency of circRNA is closely related to the integrity and extension speed of RNA polymerase II [67]. Compared with miRNAs, circRNAs are more conservative and tissue specific. As early as 1979, circRNAs were observed through electron microscopy, but these molecules have always been considered as "junk" products of abnormal splicing [68]. In 1993, the testicular-specific circRNA derived from the sex-determining region (SRY) gene was found to be functional [69]. With the development of next-generation sequencing technology, thousands of circRNAs have been detected in the testes. Most testicular circRNAs are derived from the exon regions of genes and are widely distributed on chromosomes (including the mitochondrial genome). CircRNAs exert their biological functions in various ways: 1) weakening the repressive effects of miRNAs on mRNA translation as “miRNA sponges”; 2) acting as decoys/transporters for factors or serving as a protein scaffold; and 3) being translated through the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) [70]. CircRNA levels increase with the progression of spermatogenesis, especially when late pachytene spermatocytes develop into round and elongating spermatids [71]. Interestingly, the differentially expressed circRNAs were detected in high-quality and low-quality human spermatozoa [72]. In addition, a large number of abnormally expressed circRNAs, such as hsa_circRNA_0023313, have also been detected in patients with NOA [73]. CicrRNAs generated from the conserved reproductive gene BOULE protect the fertility of males under heat stress [74]. In addition, the level of circBoule RNAs in asthenozoospermic sperm is lower [74]. Thus, sperm-derived circRNAs are potential modulators of sperm quality and can be used as a new non-invasive biomarker for male fertility.

piRNA

piRNA, another member of the non-coding RNA family, was discovered in 2006 and has high specificity in germ cells. piRNA can be divided into two categories according to piRNA expression in germ cells: pre-pachytene piRNAs and pachytene piRNAs. The length of piRNAs is mainly 24–31nt, which is longer than that of other small non-coding RNAs. piRNAs interact with PIWI subfamily members, represented by MIWI, MILI, and MIWI2. piRNA and PIWI proteins may inhibit transposable elements, regulate translation, participate in germline stem cell maintenance, regulate RNA degradation, and influence cellular defence at the transcriptional or post-transcriptional level [59]. Deficiency in any of the PIWI proteins (MIWI, MILI, and MIWI2) in mice causes aberrant piRNA production and spermatogenesis arrest [75–77]. In addition, a recent study revealed that the assembly of PIWI proteins and piRNAs can assemble to form germ granules, which are products of liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS), are filled with amorphous fibrous material mixed with RNA [78], and protect germline transcripts from inappropriate piRNA-induced silencing [79]. piRNAs establish intergenerational responses to environmental stress in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans [80]. In addition, recent research shows that piRNA-30473 contributes to tumourigenesis by regulating m6A RNA methylation in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [81], which may provide new insights into piRNA-mediated multi-generational epigenetic inheritance through m6A.

tsRNAs and rsRNA

In recent years, a novel class of tRNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) has been identified in mature mouse sperm [82]. In contrast to other small RNAs, the length of tsRNA (also known as tRNA-derived fragments, tRFs) is mainly 30–40nt. Sperm tsRNAs have been reported to play an important role in transmitting paternal high-fat-diet (HFD)-induced impaired glucose-tolerance phenotype in the progeny [83]. Further studies showed that deletion of tRNA methyltransferase abolished the transmission of HFD-induced metabolic disorder, implicating sperm RNA modifications as an additional layer of paternal hereditary information [84]. There are two independent pathways for tsRNAs biogenesis: one involving the specific cleavage in the T-loop of mature nuclear tRNAs and the other involving the mitochondrial tsRNAs [85]. tsRNAs are scarce in testicular sperm, but are abundant in mature sperm in the epididymis, suggesting the important role of exsome transfer [86]. The transcription of mitochondrial small RNAs is rarely understood.

In addition to tsRNAs, an underestimated “housekeeping RNA-derived” small RNA family (rsRNAs) is enriched in mature sperm and various somatic tissues [87]. Similar to tsRNAs, rsRNA-28 s are more abundant in mature sperm in the epididymis than in testicular sperm. Recent studies have suggested that rsRNA-28 s and tsRNAs are actively involved in the acute phase inflammation in mice [87]. The potential existence and function of these small RNAs in mature sperm increase understanding of mechanisms involved in reproductive health.

RNA-m6A modifications and spermatogenesis

mRNA-m6A modifications in spermatogenesis

m6A is the most abundant modification of mammalian mRNAs. To date, more than 12,000 m6A sites have been identified in more than 7000 genes using m6A affinity purification and sequencing (m6A-seq). Each mRNA contains an average of 3–5 m6A sites, which are synthesized co-transcriptionally and depend on the dynamics of RNA polymerase II [88]. The abundance of m6A in nascent transcripts is higher than that in mRNA in the nucleoplasm or in the cytoplasm [89, 90]. Histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 36 (H3K36me3), a marker for transcription elongation, guides m6A modification co-transcriptionally [89]. m6A modification is enriched near H3K36me3 peaks and reduced globally when cellular H3K36me3 is depleted. In addition, when the histone methyltransferase SETD2 is silenced, the target gene loci modified by the classic methyltransferase complex (METTL3 / METTL14 / WTAP), especially the CDS and 3′UTR regions, are hypomethylated. Further research shows that METTL14 directly recognizes and binds H3K36me3, promoting the transcription of nascent RNA with m6A modification [89]. The information exchange (cross talk) between histone modification and m6A modification provides a new concept for the biosynthesis of mRNA-m6A.

During spermatogenesis, many genes are regulated by m6A modification in spermatogonial differentiation, meiosis, spermiogenesis, and other processes. m6A modification is highly enriched in pachytene/diplotene spermatocytes and round spermatids. Many m6A-target transcripts in male germ cells have been identified as the result of the development of high-throughput sequencing [4, 12, 33, 39, 42] (summarized in Table 2).

Table 2.

m6A-target genes in spermatogenesis

| Stage-specific events | m6A-target genes |

|---|---|

| Spermatogonial stem cell maintenance | Dazl, Ddx4, Plzf, Pax7, Nanos2, Id4, Pou3f1, Taf4b, Bcl6, Etv5, Bcl6b, Lhx1, Pou3f1, Gfrα1, Ret, Pou5f1, Foxo1, Lin28a, Plzf, Sox3, Taf4b, Stat3 |

| Spermatogonial differentiation | Sohlh1, Sohlh2, Neurog3, Kit, Dmrt1, Sox3, Stra8, Kit, Sohlh2, Dnmt3b, Ccnd2 |

| Meiosis | Stra8, Sycp1, Sycp3, Spo11, Rad18, Dmc1, Rec8, Mlh1, Smc1b, Prdm9, Spo11, Gm960, Rec114, Mei4, Hormad1, Rpa1, Brca1, Brca2, Dmc1, Rad51, Rec8, Atm, Msh4/5, Mlh1/3, Marf1 |

| Spermiogenesis | Brd7, Cstf2t, Jmjd1c, Parp11, Lmtk2, Tdrd12, Gopc, Pick1, Csnk2a2, Spaca1, Setd2, Gba2, Agfg1, Spaca1, Prm1, Camk4, Pygo2, Crem, Prm2, Foxj1, Dnnaf3 |

miRNA-m6A modifications in spermatogenesis

During the process of maturation of miRNA, the pri-miRNA is methylated by METTL3, allowing its recognition by HNRNPA2B1 and processing by DGCR8 [91, 92]. HNRNPA2B1 is recruited by "m6A switch" [93] and combined with DGCR8 promotes pri-miRNA processing [92]. For example, METTL3 interacts with DGCR8 to regulate the processing of pri-miRNA-221/222 in an m6A -dependent manner and downregulate the tumor-suppressor gene PTEN in bladder cancer [94]. The effect of METTL3 depletion on miRNA processing is not restricted to a particular cell line but is also observed in multiple cell types [95]. Additionally, HNRNPA2B1 can also regulate miRNA production and exert biological functions, such as endocrine resistance in breast cancer [96].

In spermatogenesis, miRNAs are expressed in a cell-specific or stage-specific manner and inhibit translation or promote mRNA decay at the post-transcriptional level [97]. miRNAs can also serve as epigenetic markers to participate in prenatal and postnatal male germ-cell development. However, the function of miRNA-m6A modifications in spermatogenesis is largely unknown. Owing to the recent discovery of the role of m6A in the promotion of mature mRNA processing, future research will focus on the understanding of the biological functions of m6A during germ-cell development.

CircRNA-m6A modifications in spermatogenesis

Recently, researchers proposed that m6A mediates the biogenesis of circRNAs [71, 98]. Junction sequences of these circRNAs appear to be enriched in m6A, which is usually located around the stop codons in linear mRNAs. Elevated m6A levels enhance circRNA production. The amount of circRNA in METTL3 deleted testes is significantly reduced compared to that in the wild type [71]. In contrast, the amount of circRNA in spermatogenic cells lacking ALKBH5 is significantly higher than that in wild-type cells [71]. For example, specific m6A promotes the synthesis of circ-ZNF609 through METTL3 and YTHDC1 in HeLa cells [99]. Although YTHDC1 was previously reported to play a role in the export of circRNAs, the export or stability of circ-ZNF609 was not found to be affected in this study [99]. This indicates that YTHDC1 on circ-ZNF609 is rate-limiting for the back-splicing reaction.

CircRNAs increase with a decrease in linear mRNAs during spermatogenesis. The number of circRNAs in mature sperm is approximately 50–100 times higher than that in spermatocytes and spermatids [71]. Further investigation indicates that circRNA encodes stable and long-lasting proteins, which compensates for the massive degradation of linear mRNAs during late spermiogenesis and maintains protein levels during the chromatin concentration stage [71]. ORF-containing circRNAs regard the specific m6A modification site as a ribosome entry site (IRES) to facilitate translation [98]. For example, specific m6A modifications promote the translation of circ-ZNF609 through YTHDF3 and eIF4G2 in HeLa cells [99]. The study of circRNA m6A in spermatogenesis is in its infancy, and additional studies are expected to reveal the role of m6A in non-coding RNA. In addition, studies have also shown that circRNAs reversely regulate m6A modification by binding to m6A-related proteins. By capturing the "eraser" ALKBH5, circSTAG1 inhibits ALKBH5 transport into the nucleus, resulting in enhanced FAAH m6A modification levels in astrocytes and reduced depression-like behavior in mice [100]. Thus, this type of feedback loop is worth exploring.

RNA modifications and epigenetic response

Environmental effects on RNA-m6A modifications

There have been several reports that external factors, such as environmental toxins [18], drugs [101], cigarette smoke [102], carbon black particles [103], ultraviolet [104], heat shock [105, 106] and PM2.5 [107], can regulate the levels of m6A modification of RNAs. For example, cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) leads to hypomethylation of DNA in the METTL3 promoter region and increases m6A levels, leading to the excessive maturation of miR-25-3p and pancreatic cancer [102]. In response to ultraviolet-induced DNA damage, m6A modification of mRNA is rapid (within 2 min) and induced at the site of DNA damage [104]. Under acute temperature stress, RNA-binding protein (DGCR8) and METTL3 are relocated to heat-shock genes, which in turn play co-transcriptional effects, affecting mRNA-m6A modifications, thus promoting mRNA degradation [106]. In addition, under heat-shock stress, the increased m6A modification in the 5′-UTR of mRNAs promotes cap-independent translation initiation, providing a mechanism for selective mRNA translation [105]. A recent study has shown that in humans with a higher PM2.5 exposure group, the expression levels of m6A writers (METTL3 and WTAP), erasers (FTO and ALKBH5), and readers (HNRNPC) are significantly higher than in the lower PM2.5 exposure control group [107]. In addition, the microbiome has a strong effect on host m6A mRNA modification by regulating the expression of both m6A writers and erasers [108]. Changes in m6A modifications induced by environmental factors may serve as molecular markers for monitoring and early diagnosis of adverse health outcomes from environmental exposure.

RNA modifications and epigenetic transgenerational inheritance

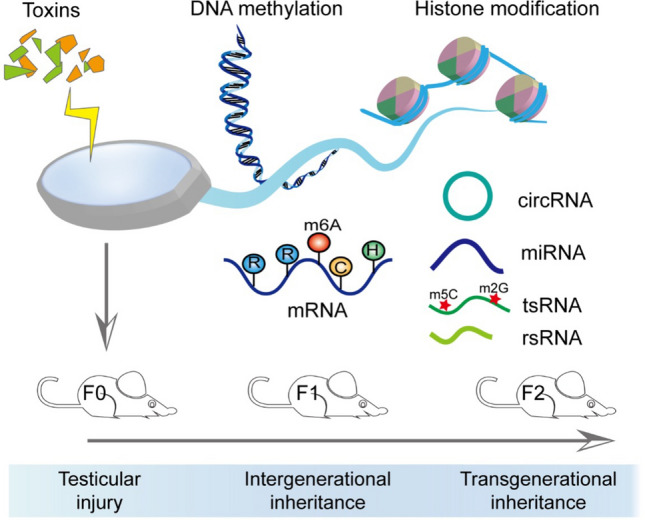

In mammals, the epigenetic response (DNA methylation, histone modifications or non-coding RNAs) plays a vital role in gametogenesis and embryonic development [6, 7]. Although sperm RNA is thought to play a minimal role in spermatogenesis, recent studies have shown that it can also be transmitted into the zygote during fertilization [109]. Mature spermatozoa are enriched in a wide range of larger RNAs (mRNA, long non-coding RNA, and circRNA) and small RNAs (miRNAs, tsRNAs, rsRNAs, and piRNAs) [82, 86, 87, 110]. Several compelling independent studies have corroborated that epigenetic modifications can be transmitted from the father to the offspring via paternal RNAs. Both coding RNA and non-coding RNA, as regulatory elements of gene expression and chromatin structure, can serve as targets of epigenetic programs induced by environmental factors, acting on the reproductive system and being transmitted from generation to generation [111]. Environmental exposure-induced epigenetic transgenerational inheritance is defined as the germ-line transmission of changed epigenetic information between generations without sustained environmental exposures [112]. When an F0 father is exposed to environmental insults, the effect on F1 (♂) is mediated by intergenerational inheritance, and the effect on F2 (♂) generation is defined as transgenerational inheritance (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

A schematic diagram of epigenetic response to environmental insults. Epigenetic alterations (DNA methylation, histone modification, m6A modification, and non-coding RNAs) induced by an environmental exposure can substantially affect the sperm function and have an inter-/transgenerational inheritance effect

Environmental exposure, such as HFD [83], high-fat and high-sugar diet [113], traumatic stress [114], and depression, alter the RNA profiles in sperm and have a corresponding impact on future generations. Several sperm miRNAs and piRNAs exhibited different expression profiles in F0 males of the depression-like model and reproduced paternal depressive-like phenotypes in F1 offspring [115]. Furthermore, when a combination of miRNA antisense strands was injected at the zygote stage to neutralize the abnormal miRNAs, successfully rescue the depressive-like phenotype in F1 offspring successfully [115]. In addition, m5C and m2G on sperm tsRNAs are involved in the intergenerational inheritance of HFD-induced metabolic disorders [83, 84]. In addition to small RNAs, large sperm RNAs could also be involved in transmitting of traumatic experiences from parent to offspring, but the mechanism is not clear [116]. Different sperm RNA fractions contain distinct profiles of RNA modifications, which add new dimensions of complexity regarding RNA structural and functional diversities (Fig. 3).

Conclusions and perspectives

Studies on the m6A of mammalian spermatogenic cells and knockout models of m6A-associated proteins have revealed the importance of m6A in spermatogonial stem cell maintenance, spermatogonial differentiation and meiosis. However, studies on the role of m6A in non-coding RNAs (such as miRNAs and circRNAs) in spermatogenesis are still very preliminary, and further research is required to enrich it. During spermatogenesis, the role of other methyltransferases, such as RBM15 (anchoring MTC in nuclear speckles and U-rich regions in mRNAs) [117], ZC3H13 (a bridge for WTAP and RBM15) [118], and KIAA1429(known as VIRMA, serving as a scaffold to guide m6A modification in the 3′-UTR around the stop codon) [119] needs also further exploration.

Crosstalk among writers, erasers, and readers of m6A regulates the homeostasis of biological processes. As key components of the methyltransferase complex, METTL3 and METTL14 are known to regulate each other’s stability at the protein level [15]. Furthermore, the “reader” YTHDF2 has been reported to preserve 5′UTR methylation of transcripts by limiting the “eraser” FTO under heat-shock stress [105]. In cancer cells, the “eraser” ALKBH5 and the “writer” METTL14 constitute a positive feedback loop to regulate the stability of m6A-target transcripts with the involvement of RNA stability factor HuR and miRNA silencing pathway [120]. Cooperation among writers, erasers, and readers ensures the appropriate m6A and proper mRNA processing.

In addition to the m6A modification, another major functional modification located on RNAs is m5C, which is abundant in tsRNAs, rsRNAs, and mRNAs. Interestingly, methylation of m5C by NSUN2 facilitates the methylation of m6A by MTC, which affects protein expression in a coordinated manner [21]. m5C also plays an important role in facilitating mRNA export [121] and preventing mRNA decay [122]. Similar to m6A, m5C modification of mRNA serves as a DNA damage code to promote homologous recombination [123]. The similarity and synergy between the various modifications in RNAs increase the charm of “RNA Epigenetics”.

The changes in the sperm RNA profile in response to environmental exposure initially revealed the role of RNA modification in coping with external pressure and its important role in epigenetic regulation. It would be promising to use the sperm RNA profile to assess the disease susceptibility of offspring. Further development of RNA sequencing technology will promote their application in translational medicine.

Author contributions

YG reviewed the literature and wrote the manuscript, SY conceived and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81971444 to S.Y.), the Science Technology and Innovation Commission of Shenzhen Municipality (JCYJ20170244 to S.Y.), and the Strategic Collaborative Research Program of the Ferring Institute of Reproductive Medicine, Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Chinese Academy of Sciences (FIRMSCOV02 to S.Y.).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.O'Donnell L, Nicholls PK, O'Bryan MK, McLachlan RI, Stanton PG. Spermiation: The process of sperm release. Spermatogenesis. 2011;1(1):14–35. doi: 10.4161/spmg.1.1.14525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Rooij DG. Proliferation and differentiation of spermatogonial stem cells. Reproduction. 2001;121(3):347–354. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1210347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griswold MD. Spermatogenesis: The Commitment to Meiosis. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(1):1–17. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin Z, Tong MH. m(6)A mRNA modification regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2019;1862(3):403–411. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abe K, Shen LS, Takano H. The cycle of the seminiferous epithelium and stages in spermatogenesis in dd-mice. [Hokkaido igaku zasshi] Hokkaido J Med Sci. 1991;66(3):286–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.L L, D C, cell TJJSi, biology d. Developmental windows of susceptibility for epigenetic inheritance through the male germline. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;43:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou S, Feng S, Qin W, Wang X, Tang Y, Yuan S. Epigenetic regulation of spermatogonial stem cell homeostasis: from dna methylation to histone modification. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s12015-020-10044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J, Jia G. Methylation modifications in eukaryotic messenger RNA. J Genet Genom = Yi chuan xue bao. 2014;41(1):21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasowitz SD, Ma J, Anderson SJ, Leu NA, Xu Y, Gregory BD, et al. Nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 regulates alternative polyadenylation and splicing during mouse oocyte development. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(5):e1007412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wojtas MN, Pandey RR, Mendel M, Homolka D, Sachidanandam R, Pillai RS. Regulation of m(6) A transcripts by the 3' 5' RNA helicase YTHDC2 is essential for a successful meiotic program in the mammalian germline. Mol Cell. 2017;68(2):374. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia H, Zhong CR, Wu XX, Chen J, Tao BB, Xia XQ, et al. Mettl3 mutation disrupts gamete maturation and reduces fertility in zebrafish. Genetics. 2018;208(2):729–743. doi: 10.1534/genetics.117.300574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu K, Yang Y, Feng GH, Sun BF, Chen JQ, Li YF, et al. Mettl3-mediated m(6)A regulates spermatogonial differentiation and meiosis initiation. Cell Res. 2017;27(9):1100–1114. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao BS, He C. "Gamete On'' for m(6)A: YTHDF2 exerts essential functions in female fertility. Mol Cell. 2017;67(6):903–905. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meng TG, Lu XK, Guo L, Hou GM, Ma XS, Li QN, et al. Mettl14 is required for mouse postimplantation development by facilitating epiblast maturation. FASEB J. 2019;33(1):1179–1187. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800719R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Y, Li Y, Toth JI, Petroski MD, Zhang Z, Zhao JC. N6-methyladenosine modification destabilizes developmental regulators in embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(2):191–198. doi: 10.1038/ncb2902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang DD, Qiao J, Wang GY, Lan YY, Li GP, Guo XD, et al. N-6-Methyladenosine modification of lincRNA 1281 is critically required for mESC differentiation potential. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(8):3906–3920. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haussmann IU, Bodi Z, Sanchez-Moran E, Mongan NP, Archer N, Fray RG, et al. m(6)A potentiates Sxl alternative pre-mRNA splicing for robust Drosophila sex determination. Nature. 2016;540(7632):301. doi: 10.1038/nature20577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao TX, Wang JK, Shen LJ, Long CL, Liu B, Wei Y, et al. Increased m6A RNA modification is related to the inhibition of the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response in di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-induced prepubertal testicular injury. Environ Pollut. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.113911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adhikari S, Xiao W, Zhao YL, Yang YG. m(6)A: signaling for mRNA splicing. Rna Biol. 2016;13(9):756–759. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1201628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu J, Chen M, Huang H, Zhu J, Song H, Zhu J, et al. Dynamic m6A modification regulates local translation of mRNA in axons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(3):1412–1423. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q, Li X, Tang H, Jiang B, Dou Y, Gorospe M, et al. NSUN2-mediated m5C methylation and METTL3/METTL14-mediated m6A methylation cooperatively enhance p21 translation. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118(9):2587–2598. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang C, Klukovich R, Peng H, Wang Z, Yu T, Zhang Y, et al. ALKBH5-dependent m6A demethylation controls splicing and stability of long 3'-UTR mRNAs in male germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(2):E325–E333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717794115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coker H, Wei G, Brockdorff N. m6A modification of non-coding RNA and the control of mammalian gene expression. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2019;1862(3):310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warda AS, Kretschmer J, Hackert P, Lenz C, Urlaub H, Hobartner C, et al. Human METTL16 is a N-6-methyladenosine (m(6)A) methyltransferase that targets pre-mRNAs and various non-coding RNAs. Embo Rep. 2017;18(11):2004–2014. doi: 10.15252/embr.201744940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang C, Xie YM, Yu T, Liu N, Wang ZQ, Woolsey RJ, et al. m(6)A-dependent biogenesis of circular RNAs in male germ cells. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):211–228. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt W, Arnold HH, Kersten H. Biosynthetic pathway of ribothymidine in B subtilis and M lysodeikticus involving different coenzymes for transfer RNA and ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1975;2(7):1043–1051. doi: 10.1093/nar/2.7.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang P, Doxtader KA, Nam Y. Structural basis for cooperative function of mettl3 and mettl14 methyltransferases. Mol Cell. 2016;63(2):306–317. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Feng J, Xue Y, Guan Z, Zhang D, Liu Z, et al. Structural basis of N(6)-adenosine methylation by the METTL3-METTL14 complex. Nature. 2016;534(7608):575–578. doi: 10.1038/nature18298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ping XL, Sun BF, Wang L, Xiao W, Yang X, Wang WJ, et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 2014;24(2):177–189. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Theler D, Dominguez C, Blatter M, Boudet J, Allain FH. Solution structure of the YTH domain in complex with N6-methyladenosine RNA: a reader of methylated RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(22):13911–13919. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhong S, Li H, Bodi Z, Button J, Vespa L, Herzog M, et al. MTA is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex-specific splicing factor. Plant Cell. 2008;20(5):1278–1288. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwartz S, Agarwala SD, Mumbach MR, Jovanovic M, Mertins P, Shishkin A, et al. High-resolution mapping reveals a conserved, widespread, dynamic mRNA methylation program in yeast meiosis. Cell. 2013;155(6):1409–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin Z, Hsu PJ, Xing X, Fang J, Lu Z, Zou Q, et al. Mettl3-/Mettl14-mediated mRNA N(6)-methyladenosine modulates murine spermatogenesis. Cell Res. 2017;27(10):1216–1230. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Y, Huang W, Huang JT, Shen F, Xiong J, Yuan EF, et al. Increased N6-methyladenosine in human sperm RNA as a risk factor for asthenozoospermia. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24345. doi: 10.1038/srep24345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warda AS, Kretschmer J, Hackert P, Lenz C, Urlaub H, Höbartner C, et al. Human METTL16 is a N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methyltransferase that targets pre-mRNAs and various non-coding RNAs. EMBO Rep. 2017;18(11):2004–2014. doi: 10.15252/embr.201744940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pendleton KE, Chen B, Liu K, Hunter OV, Xie Y, Tu BP, et al. The U6 snRNA m(6)A methyltransferase mettl16 regulates SAM synthetase intron retention. Cell. 2017;169(5):824–35.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dorsett M, Westlund B, Schedl T. METT-10, a putative methyltransferase, inhibits germ cell proliferative fate in caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2009;183(1):233–247. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.105270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gulati P, Avezov E, Ma M, Antrobus R, Lehner P, O'Rahilly S, 2014. Fat mass and obesity-related (FTO) shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Biosci Rep. Epub 2014/09/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49(1):18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fu Y, Klungland A, Yang YG, et al. Sprouts of RNA epigenetics: the discovery of mammalian RNA demethylases. RNA Biol. 2013;10(6):915–918. doi: 10.4161/rna.24711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao X, Yang Y, Sun BF, Shi Y, Yang X, Xiao W, et al. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res. 2014;24(12):1403–1419. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tang C, Klukovich R, Peng H, Wang Z, Yu T, Zhang Y, et al. ALKBH5-dependent m6A demethylation controls splicing and stability of long 3'-UTR mRNAs in male germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(2):325–333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1717794115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landfors M, Nakken S, Fusser M, Dahl JA, Klungland A, Fedorcsak P. Sequencing of FTO and ALKBH5 in men undergoing infertility work-up identifies an infertility-associated variant and two missense mutations. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(5):1170–9.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu N, Dai Q, Zheng G, He C, Parisien M, Pan T. N(6)-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature. 2015;518(7540):560–564. doi: 10.1038/nature14234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wojtas MN, Pandey RR, Mendel M, Homolka D, Sachidanandam R, Pillai RS. Regulation of m(6)A transcripts by the 3' 5' RNA helicase YTHDC2 Is essential for a successful meiotic program in the mammalian germline. Mol Cell. 2017;68(2):374–387. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bailey AS, Batista PJ, Gold RS, Chen YG, de Rooij DG, Chang HY, et al. The conserved RNA helicase YTHDC2 regulates the transition from proliferation to differentiation in the germline. Elife. 2017;6:e26116. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang T, Liu Z, Zheng Y, Feng T, Gao Q, Zeng W. YTHDF2 promotes spermagonial adhesion through modulating MMPs decay via m(6)A/mRNA pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(1):37. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-2235-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jain D, Puno MR, Meydan C, Lailler N, Mason CE, Lima CD, et al. ketu mutant mice uncover an essential meiotic function for the ancient RNA helicase YTHDC2. Elife. 2018 doi: 10.7554/eLife.30919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abby E, Tourpin S, Ribeiro J, Daniel K, Messiaen S, Moison D, et al. Implementation of meiosis prophase I programme requires a conserved retinoid-independent stabilizer of meiotic transcripts. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10324. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roundtree IA, Luo GZ, Zhang Z, Wang X, Zhou T, Cui Y, et al. YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N(6)-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. Elife. 2017 doi: 10.7554/eLife.31311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rafalska I, Zhang Z, Benderska N, Wolff H, Hartmann AM, Brack-Werner R, et al. The intranuclear localization and function of YT521-B is regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(15):1535–1549. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li M, Zhao X, Wang W, Shi H, Pan Q, Lu Z, et al. Ythdf2-mediated m(6)A mRNA clearance modulates neural development in mice. Genome Biol. 2018;19(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1436-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang Z, Li J, Feng G, Gao S, Wang Y, Zhang S, et al. MicroRNA-145 modulates N(6)-Methyladenosine levels by targeting the 3'-untranslated mRNA region of the N(6)-methyladenosine binding YTH domain family 2 protein. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(9):3614–3623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.749689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ivanova I, Much C, Di Giacomo M, Azzi C, Morgan M, Moreira PN, et al. The RNA m(6)A reader YTHDF2 is essential for the post-transcriptional regulation of the maternal transcriptome and oocyte competence. Mol Cell. 2017;67(6):1059–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jia GX, Lin Z, Yan RG, Wang GW, Zhang XN, Li C, et al. WTAP function in sertoli cells is essential for sustaining the spermatogonial stem cell niche. Stem Cell Rep. 2020;15(4):968–982. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang YW, Chen L, Mou Q, Liang H, Du ZQ, Yang CX. Ascorbic acid promotes the reproductive function of porcine immature Sertoli cells through transcriptome reprogramming. Theriogenology. 2020;158:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2020.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen Y, Wang J, Xu D, Xiang Z, Ding J, Yang X, et al. m(6)A mRNA methylation regulates testosterone synthesis through modulating autophagy in Leydig cells. Autophagy. 2020 doi: 10.1080/15548627.2020.1720431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao T, Wang J, Wu Y, Han L, Chen J, Wei Y, et al. Increased m6A modification of RNA methylation related to the inhibition of demethylase FTO contributes to MEHP-induced Leydig cell injury(☆) Environ Pollut. 2021;268:115627. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136(2):215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Z, Yao H, Lin S, Zhu X, Shen Z, Lu G, et al. Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of human microRNAs. Cancer Lett. 2013;331(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kotaja N. MicroRNAs and spermatogenesis. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(6):1552–1562. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ro S, Park C, Sanders KM, McCarrey JR, Yan W. Cloning and expression profiling of testis-expressed microRNAs. Dev Biol. 2007;311(2):592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yuan S, Tang C, Zhang Y, Wu J, Bao J, Zheng H, et al. mir-34b/c and mir-449a/b/c are required for spermatogenesis, but not for the first cleavage division in mice. Biol Open. 2015;4(2):212–223. doi: 10.1242/bio.201410959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yuan S, Liu Y, Peng H, Tang C, Hennig GW, Wang Z, et al. Motile cilia of the male reproductive system require miR-34/miR-449 for development and function to generate luminal turbulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(9):3584–3593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1817018116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zimmermann C, Romero Y, Warnefors M, Bilican A, Borel C, Smith LB, et al. Germ cell-specific targeting of DICER or DGCR8 reveals a novel role for endo-siRNAs in the progression of mammalian spermatogenesis and male fertility. PLoS one. 2014;9(9):e107023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu W, Qin Y, Li Z, Dong J, Dai J, Lu C, et al. Genome-wide microRNA expression profiling in idiopathic non-obstructive azoospermia: significant up-regulation of miR-141, miR-429 and miR-7–1–3p. Hum Rep. 2013;28(7):1827–1836. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Salzman J, Circular RNA. Expression: its potential regulation and function. Trends genet: TIG. 2016;32(5):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hsu MT, Coca-Prados M. Electron microscopic evidence for the circular form of RNA in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells. Nature. 1979;280(5720):339–340. doi: 10.1038/280339a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Capel B, Swain A, Nicolis S, Hacker A, Walter M, Koopman P, et al. Circular transcripts of the testis-determining gene Sry in adult mouse testis. Cell. 1993;73(5):1019–1030. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90279-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kristensen LS, Andersen MS, Stagsted LVW, Ebbesen KK, Hansen TB, Kjems J. The biogenesis, biology and characterization of circular RNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(11):675–691. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tang C, Xie Y, Yu T, Liu N, Wang Z, Woolsey RJ, et al. m(6)A-dependent biogenesis of circular RNAs in male germ cells. Cell Res. 2020;30(3):211–228. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chioccarelli T, Manfrevola F, Ferraro B, Sellitto C, Cobellis G, Migliaccio M, et al. Expression patterns of circular RNAs in high quality and poor quality human spermatozoa. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:435. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ge P, Zhang J, Zhou L, Lv MQ, Li YX, Wang J, et al. CircRNA expression profile and functional analysis in testicular tissue of patients with non-obstructive azoospermia. Reprod Biol Endocrinol: RB&E. 2019;17(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s12958-019-0541-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gao L, Chang S, Xia W, Wang X, Zhang C, Cheng L, et al. Circular RNAs from BOULE play conserved roles in protection against stress-induced fertility decline. Sci Adv. 2020;6(46):eabb7426. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abb7426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kuramochi-Miyagawa S, Kimura T, Ijiri TW, Isobe T, Asada N, Fujita Y, et al. Mili, a mammalian member of piwi family gene, is essential for spermatogenesis. Development. 2004;131(4):839–849. doi: 10.1242/dev.00973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carmell MA, Girard A, van de Kant HJG, Bourc'his D, Bestor TH, de Rooij DG, et al. MIWI2 is essential for spermatogenesis and repression of transposons in the mouse male germline. Dev Cell. 2007;12(4):503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deng W, Lin HF. miwi, a murine homolog of piwi, encodes a cytoplasmic protein essential for spermatogenesis. Dev Cell. 2002;2(6):819–830. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00165-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Trcek T, Lehmann R. Germ granules in drosophila. Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark). 2019;20(9):650–660. doi: 10.1111/tra.12674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pal A, Shah VN, Simard MJ. Defend thyself and thy offspring. Dev Cell. 2019;50(6):677–679. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Belicard T, Jareosettasin P, Sarkies P. The piRNA pathway responds to environmental signals to establish intergenerational adaptation to stress. BMC Biol. 2018;16(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s12915-018-0571-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Han H, Fan G, Song S, Jiang Y, Qian C, Zhang W, et al. piRNA-30473 contributes to tumorigenesis and poor prognosis by regulating m6A RNA methylation in DLBCL. Blood. 2020 doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peng H, Shi J, Zhang Y, Zhang H, Liao S, Li W, et al. A novel class of tRNA-derived small RNAs extremely enriched in mature mouse sperm. Cell Res. 2012;22(11):1609–1612. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen Q, Yan M, Cao Z, Li X, Zhang Y, Shi J, et al. Sperm tsRNAs contribute to intergenerational inheritance of an acquired metabolic disorder. Science. 2016;351(6271):397–400. doi: 10.1126/science.aad7977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang Y, Zhang X, Shi J, Tuorto F, Li X, Liu Y, et al. Dnmt2 mediates intergenerational transmission of paternally acquired metabolic disorders through sperm small non-coding RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20(5):535–540. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0087-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nätt D, Kugelberg U, Casas E, Nedstrand E, Zalavary S, Henriksson P, et al. Human sperm displays rapid responses to diet. PLoS Biol. 2019;17(12):e3000559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sharma U, Conine CC, Shea JM, Boskovic A, Derr AG, Bing XY, et al. Biogenesis and function of tRNA fragments during sperm maturation and fertilization in mammals. Science. 2016;351(6271):391–396. doi: 10.1126/science.aad6780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chu C, Yu L, Wu B, Ma L, Gou LT, He M, et al. A sequence of 28S rRNA-derived small RNAs is enriched in mature sperm and various somatic tissues and possibly associates with inflammation. J Mol Cell Biol. 2017;9(3):256–259. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjx016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Slobodin B, Han R, Calderone V, Vrielink J, Loayza-Puch F, Elkon R, et al. Transcription impacts the efficiency of mRNA translation via co-transcriptional N6-adenosine methylation. Cell. 2017;169(2):326–37.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Huang H, Weng H, Zhou K, Wu T, Zhao BS, Sun M, et al. Histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 36 guides m(6)A RNA modification co-transcriptionally. Nature. 2019;567(7748):414–419. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1016-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ke S, Pandya-Jones A, Saito Y, Fak JJ, Vågbø CB, Geula S, et al. m(6)A mRNA modifications are deposited in nascent pre-mRNA and are not required for splicing but do specify cytoplasmic turnover. Genes Dev. 2017;31(10):990–1006. doi: 10.1101/gad.301036.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Alarcón CR, Lee H, Goodarzi H, Halberg N, Tavazoie SF. N6-methyladenosine marks primary microRNAs for processing. Nature. 2015;519(7544):482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature14281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Alarcon CR, Goodarzi H, Lee H, Liu X, Tavazoie S, Tavazoie SF. HNRNPA2B1 is a mediator of m(6)A-dependent nuclear RNA processing events. Cell. 2015;162(6):1299–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wu B, Su S, Patil DP, Liu H, Gan J, Jaffrey SR, et al. Molecular basis for the specific and multivariant recognitions of RNA substrates by human hnRNP A2/B1. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):420. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02770-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Han J, Wang JZ, Yang X, Yu H, Zhou R, Lu HC, et al. METTL3 promote tumor proliferation of bladder cancer by accelerating pri-miR221/222 maturation in m6A-dependent manner. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Alarcon CR, Lee H, Goodarzi H, Halberg N, Tavazoie SF. N6-methyladenosine marks primary microRNAs for processing. Nature. 2015;519(7544):482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature14281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Klinge CM, Piell KM, Tooley CS, Rouchka EC. HNRNPA2/B1 is upregulated in endocrine-resistant LCC9 breast cancer cells and alters the miRNA transcriptome when overexpressed in MCF-7 cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):9430. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45636-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen X, Li X, Guo J, Zhang P, Zeng W. The roles of microRNAs in regulation of mammalian spermatogenesis. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2017;8:35. doi: 10.1186/s40104-017-0166-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yang Y, Fan X, Mao M, Song X, Wu P, Zhang Y, et al. Extensive translation of circular RNAs driven by N(6)-methyladenosine. Cell Res. 2017;27(5):626–641. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Di Timoteo G, Dattilo D, Centrón-Broco A, Colantoni A, Guarnacci M, Rossi F, et al. Modulation of circRNA metabolism by m(6)A modification. Cell Rep. 2020;31(6):107641. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Huang R, Zhang Y, Bai Y, Han B, Ju M, Chen B, et al. N(6)-Methyladenosine modification of fatty acid amide hydrolase messenger RNA in circular RNA STAG1-regulated astrocyte dysfunction and depressive-like behaviors. Biol Psychiat. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Huang T, Guo J, Lv Y, Zheng Y, Feng T, Gao Q, et al. Meclofenamic acid represses spermatogonial proliferation through modulating m(6)A RNA modification. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2019;10:63. doi: 10.1186/s40104-019-0361-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang J, Bai R, Li M, Ye H, Wu C, Wang C, et al. Excessive miR-25–3p maturation via N(6)-methyladenosine stimulated by cigarette smoke promotes pancreatic cancer progression. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1858. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09712-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Han B, Chu C, Su X, Zhang N, Zhou L, Zhang M, et al. N(6)-methyladenosine-dependent primary microRNA-126 processing activated PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway drove the development of pulmonary fibrosis induced by nanoscale carbon black particles in rats. Nanotoxicology. 2020;14(1):1–20. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2019.1661041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xiang Y, Laurent B, Hsu CH, Nachtergaele S, Lu Z, Sheng W, et al. RNA m(6)A methylation regulates the ultraviolet-induced DNA damage response. Nature. 2017;543(7646):573–576. doi: 10.1038/nature21671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhou J, Wan J, Gao X, Zhang X, Jaffrey SR, Qian S-B. Dynamic m(6)A mRNA methylation directs translational control of heat shock response. Nature. 2015;526(7574):591–594. doi: 10.1038/nature15377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Knuckles P, Carl SH, Musheev M, Niehrs C, Wenger A, Bühler M. RNA fate determination through cotranscriptional adenosine methylation and microprocessor binding. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24(7):561–569. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cayir A, Barrow TM, Guo L, Byun HM. Exposure to environmental toxicants reduces global N6-methyladenosine RNA methylation and alters expression of RNA methylation modulator genes. Environ Res. 2019;175:228–234. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wang X, Li Y, Chen W, Shi H, Eren AM, Morozov A, et al. Transcriptome-wide reprogramming of N(6)-methyladenosine modification by the mouse microbiome. Cell Res. 2019;29(2):167–170. doi: 10.1038/s41422-018-0127-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Johnson GD, Mackie P, Jodar M, Moskovtsev S, Krawetz SA. Chromatin and extracellular vesicle associated sperm RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(14):6847–6859. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sharma U, Sun F, Conine CC, Reichholf B, Kukreja S, Herzog VA, et al. Small RNAs are trafficked from the epididymis to developing mammalian sperm. Dev Cell. 2018;46(4):481–94.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gòdia M, Swanson G, Krawetz SA. A history of why fathers' RNA matters. Biol Reprod. 2018;99(1):147–159. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nilsson EE, Skinner MK. environmentally induced epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of reproductive disease. Biol Reprod. 2015;93(6):145. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.115.134817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Grandjean V, Fourré S, De Abreu DA, Derieppe MA, Remy JJ, Rassoulzadegan M. RNA-mediated paternal heredity of diet-induced obesity and metabolic disorders. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18193. doi: 10.1038/srep18193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gapp K, Jawaid A, Sarkies P, Bohacek J, Pelczar P, Prados J, et al. Implication of sperm RNAs in transgenerational inheritance of the effects of early trauma in mice. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(5):667–669. doi: 10.1038/nn.3695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang Y, Chen ZP, Hu H, Lei J, Zhou Z, Yao B, et al. Sperm microRNAs confer depression susceptibility to offspring. Sci Adv. 2021;7(7):eabd7608. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd7605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Gapp K, van Steenwyk G, Germain PL, Matsushima W, Rudolph KLM, Manuella F, et al. Alterations in sperm long RNA contribute to the epigenetic inheritance of the effects of postnatal trauma. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(9):2162–2174. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0271-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Patil DP, Chen C-K, Pickering BF, Chow A, Jackson C, Guttman M, et al. m(6)A RNA methylation promotes XIST-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature. 2016;537(7620):369–373. doi: 10.1038/nature19342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Knuckles P, Lence T, Haussmann IU, Jacob D, Kreim N, Carl SH, et al. Zc3h13/Flacc is required for adenosine methylation by bridging the mRNA-binding factor Rbm15/Spenito to the m(6)A machinery component Wtap/Fl(2)d. Genes Dev. 2018;32(5–6):415–429. doi: 10.1101/gad.309146.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yue Y, Liu J, Cui X, Cao J, Luo G, Zhang Z, et al. VIRMA mediates preferential m(6)A mRNA methylation in 3'UTR and near stop codon and associates with alternative polyadenylation. Cell discovery. 2018;4:10. doi: 10.1038/s41421-018-0019-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Panneerdoss S, Eedunuri VK, Yadav P, Timilsina S, Rajamanickam S, Viswanadhapalli S, et al. Cross-talk among writers, readers, and erasers of mA regulates cancer growth and progression. Sci Adv. 2018;4(10):eaar8263. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aar8263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yang X, Yang Y, Sun BF, Chen YS, Xu JW, Lai WY, et al. 5-methylcytosine promotes mRNA export - NSUN2 as the methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m(5)C reader. Cell Res. 2017;27(5):606–625. doi: 10.1038/cr.2017.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Yang Y, Wang L, Han X, Yang WL, Zhang M, Ma HL, et al. RNA 5-methylcytosine facilitates the maternal-to-zygotic transition by preventing maternal mRNA decay. Mol Cell. 2019;75(6):1188–202.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chen H, Yang H, Zhu X, Yadav T, Ouyang J, Truesdell SS, et al. m(5)C modification of mRNA serves a DNA damage code to promote homologous recombination. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2834. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16722-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Gulati P, Avezov E, Ma M, Antrobus R, Lehner P, O'Rahilly S, 2014. Fat mass and obesity-related (FTO) shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Biosci Rep. Epub 2014/09/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]