Abstract

Overexpression of EGFR drives glioblastomas (GBM) cell invasion but these tumours remain resistant to EGFR-targeted therapies such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). Endocytosis, an important modulator of EGFR function, is often dysregulated in glioma cells and is associated with therapy resistance. However, the impact of TKIs on EGFR endocytosis has never been examined in GBM cells. In the present study, we showed that gefitinib and other tyrosine kinase inhibitors induced EGFR accumulation in early-endosomes as a result of an increased endocytosis. Moreover, TKIs trigger early-endosome re-localization of another membrane receptor, the fibronectin receptor alpha5beta1 integrin, a promising therapeutic target in GBM that regulates physiological EGFR endocytosis and recycling in cancer cells. Super-resolution dSTORM imaging showed a close-proximity between beta1 integrin and EGFR in intracellular membrane compartments of gefitinib-treated cells, suggesting their potential interaction. Interestingly, integrin depletion delayed gefitinib-mediated EGFR endocytosis. Co-endocytosis of EGFR and alpha5beta1 integrin may alter glioma cell response to gefitinib. Using an in vitro model of glioma cell dissemination from spheroid, we showed that alpha5 integrin-depleted cells were more sensitive to TKIs than alpha5-expressing cells. This work provides evidence for the first time that EGFR TKIs can trigger massive EGFR and alpha5beta1 integrin co-endocytosis, which may modulate glioma cell invasiveness under therapeutic treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00018-020-03686-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Adhesion receptors, Cell migration, Growth factors receptors, Brain cancer, Membrane trafficking

Introduction

Glioblastomas (GBM), a subgroup of the diffuse astrocytic and oligodendroglial tumours [1], are the most frequent and aggressive brain tumours. GBM are characterized by an inter- and intra-tumoral heterogeneity and a highly invasive phenotype. Overexpression or mutations of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR, HER1, ErbB1) are recurrent molecular alterations in GBM, associated with an unfavourable prognosis [2]. EGFR, a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase which belongs to the ERBB family, is responsible for glioma cell proliferation, survival, invasiveness and stemness regulation [3]. Although EGFR is an attractive therapeutic target in GBM, targeted therapies using EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) failed to improve patient care [4, 5]. Following ligand binding and internalization, EGFR is either transported to lysosomes for degradation or recycled to the plasma membrane [6]. Many studies have shown that EGFR can trigger a wide range of signalling pathways from both cell surface and the endosomal compartment [7, 8] and that spatial regulation of EGFR signalling closely regulates its oncogenic activity [9]. The overexpression of Sprouty2 or Golgi phosphoprotein 3 (GOLPH3), two proteins that prevent EGFR endocytosis, promotes the tumorigenic potential of glioma cells in vitro and in vivo [7, 10, 12–15]. Sortilin, a member of the vacuolar protein sorting 10 (VPS10), binds to normal EGFR, promoting receptor internalization [16] and intracellular trafficking to degradation or exosome secretion pathway [17]. In contrast with GOLPH3, sortilin overexpression reduces tumour growth in lung cancer [16]. The Na+/H+ exchanger NHE9 limits EGFR turnover in endolysosomal compartment by inhibiting luminal acidification. EGFR downstream signalling pathways are thus sustained in NHE9 overexpressing glioma cells to promote tumour growth and cell invasion [18, 19]. EGFR interaction with Mig-6 (mitogen-inducible gene 6), a tumour suppressor gene, has been shown to inhibit EGFR signalling in cancer cells [11, 20, 21]. In GBM, Mig-6 drives EGFR trafficking to late endosome and to lysosomal degradation by linking EGFR to the SNARE protein (soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive-factor attachment protein receptor protein) syntaxin 8 [22, 23]. Loss of Mig-6 in GBM amplifies EGFR oncogenic activity by altering receptor trafficking [22].

By organizing signalling platform called adhesome [24], integrins, a family of cell adhesion receptors, cooperate with several growth factor receptors (GFRs) including EGFR to drive tumour progression and aggressiveness [25]. Integrins also play a key role in resistance to GFR-targeted therapies [26, 27]. Moreover, recent publications revealed that integrins orchestrate GFRs endocytic pathway [25, 28]. For instance, the fibronectin receptor, integrin α5β1 drives EGFR recycling from endosomes to the plasma membrane by promoting the interaction of the Rab-coupling protein to EGFR. Coordinate recycling of α5β1 integrin and EGFR leads to an increase in EGFR downstream signalling and promotes carcinoma cell invasion [29]. Genome-wide RNA interference screening identified integrins α5β1 and α2β1 as potential regulators of EGFR endocytosis [30]. We and others previously showed that the fibronectin receptor, is a pertinent therapeutic target in GBM [31–34] but the role of α5β1 in EGFR trafficking in GBM has not been examined so far.

The aberrant expression of proteins regulating EGFR membrane trafficking promotes glioma cell invasion and tumour progression [15, 16, 18, 35, 36]. However, the impact of TKIs on EGFR trafficking has not been studied in GBM cells. Conflicting results have been published in other solid tumour models. Gefitinib, an EGFR-TKI, could either induce EGFR endocytosis in mammary cancer cells [37] or limit EGFR internalization in lung carcinoma cells [38, 39].

The objective of our work was to evaluate the impact of clinically approved-TKIs on EGFR distribution in GBM cellular models. We showed that gefitinib strongly altered EGFR and integrin trafficking and promoted their endocytosis. Importantly, α5β1 integrin silencing delays gefitinib-mediated EGF endocytosis. Furthermore, depletion of the α5β1 integrin increased gefitinib efficacy to inhibit cell dissemination from GBM spheroids. Our findings uncover TKIs as key regulators of EGFR intracellular trafficking and highlight the complex relationship between EGFR and α5β1 integrin during GBM cell dissemination.

Material and methods

Reagents

Anti-EGFR antibody (D1D4J) and anti-Rab5 (C8B1) were from Cell Signaling. Anti-α5 integrin (IIA1) and anti–EEA1 (610,457) were from BD Transductions. Anti-β1 integrin (TS2/16) was from BioLegend. Fluorescently labelled secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen (Alexa Fluor − 488; − 568; − 647). DAPI was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Phalloïdin-Atto 488 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Following antibodies were used for immunoblot. Anti-EGFR antibody (D38B1) was from Cell Signaling, anti-α5 integrin (H104) from Santa Cruz and GAPDH from Millipore. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen. Cell culture medium and reagents were from Lonza. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors were obtained from ChemiTek. All other reagents were of molecular biology quality.

Cell culture

The human glioblastoma cell line U87MG was obtained from ATCC. T98G cells were purchased from ECACC (European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures, Sigma). LN443, LN18, and LNZ308 cells were kindly provided by Prof. Monika Hegi (Lausanne, Switzerland). GBM cells were maintained in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% sodium pyruvate and 1% nonessential amino-acid, in a 37 °C humidified incubator with 5% CO2. U87 cells were transfected by a specific shRNA targeting α5mRNA. U87 cells expressing α5-shRNA are considered as low α5 expressing cells (U87α5–) [40]. Plasmid encoding Rab5a-eYFP was kindly provided by Dr. Marino Zerial (MaxPlanck Institut, Germany) and plasmid containing α5-GFP was kindly provided by Dr. Alan Horwitz (University of Virginia, USA). Cells were transfected with 1.5 µg of DNA using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Fluorescent protein expression was confirmed the day after.

Cell growth

2D cell growth- Cells were plated (1000 cells/well) onto a 96-well plate in EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Cell viability was determined using a tetrazolium compound [3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt (MTS assay—CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Cell proliferation assay from Promega) at the indicated time. 3D cell growth- Single-cell suspension was mixed in EMEM/10% FBS containing 10% of methylcellulose [40]. All the spheroids were made on a U-bottom 96 well plate (Greiner Cellstar U-bottom culture plate) (100 μL, 2000 cells). Sphere growth was monitored for 8 days by phase-contrast microscopy (EVOS xl Core, 20 × magnification). Sphere area was measured using ImageJ software.

Soft agar assay for colony formation and cell survival

Assays of colony formation in soft agar were performed essentially as described previously. Briefly, 1-ml underlayers of 0.5% agar medium were prepared in 35-mm dishes by combining equal volumes of 1% agar solution and 2 × EMEM with 20% fetal bovine serum. U87 cells were trypsinized, centrifuged, and resuspended. Cells were further filtered through sterile cell strainers (Corning). 104 single cells were plated in 0.3% agar medium. Growth medium was added to the top of the agar gel. When indicated gefitinib or DMSO were added in all step of soft agar preparation at the indicated final concentration. After 15 days, formed colonies were stained with 0.005% crystal violet solution for 1 h, and counted. Results are expressed as percentage colonies formed in presence of gefitinib versus solvent.

Confocal microscopy and image analysis

Coverslips were coated with fibronectin (20 μg.mL−1 in DPBS). 15 000 cells were seeded in serum-containing medium and cultured for 24 h before TKI treatment. Alternatively, two-day-old U87 cell spheroids were seeded in complete medium in the presence or absence of TKIs. Cells were then fixed in 3.7% (v/v) paraformaldehyde during 10 min, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X100 for 2 min. After a 60-min blocking step using PBS-BSA 3% solution, cells were incubated with primary antibodies O/N at 4 °C (2 μg.mL−1 each in PBS-BSA 3%). Cells were rinsed in PBS and incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies (1 μg.mL−1 in PBS-BSA 3%) and DAPI for 45 min. Samples were mounted on microscope slides using fluorescence mounting medium (Dako). Images were acquired using a confocal microscope (LEICA TCS SPE II, 60 × magnification oil-immersion, N/A 1.3). For each experiment, identical background subtraction and scaling were applied to all images. Pearson correlation and Mender’s coefficients from 10–12 images (4–5 cells per images) from 3 independent experiments were calculated using JACoP plugin ImageJ software [41]. Quantification of the colocalized pixels in the cell periphery or in the perinuclear region (Fig. 2b and supplemental Fig. 5b) were performed using home-made Image J plugin. Briefly, using segmentation tools, a first region of interest (ROI) “total cell” corresponding to the cell contour is previously defined. A second ROI “cell periphery” is then defined as a regular inner region of 13 pixels following the cell contour. The third ROI “perinuclear region” is derived from the subtraction of the first two and the elimination of an ROI corresponding to the nucleus (DAPI labelling). Integrin/EGFR colocalized pixels are determined on each image using the scatter plot thanks to the Colocalization Finder plugin (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/plugins/colocalization-finder.html). After binarisation of the colocalized pixel channel, the obtained image is used to quantify the number of colocalized pixels in each ROI, cell by cell. The results are expressed as (number of colocalized pixel in ROI “cell periphery” or “perinuclear”/number of colocalized pixel in ROI “total cell”).

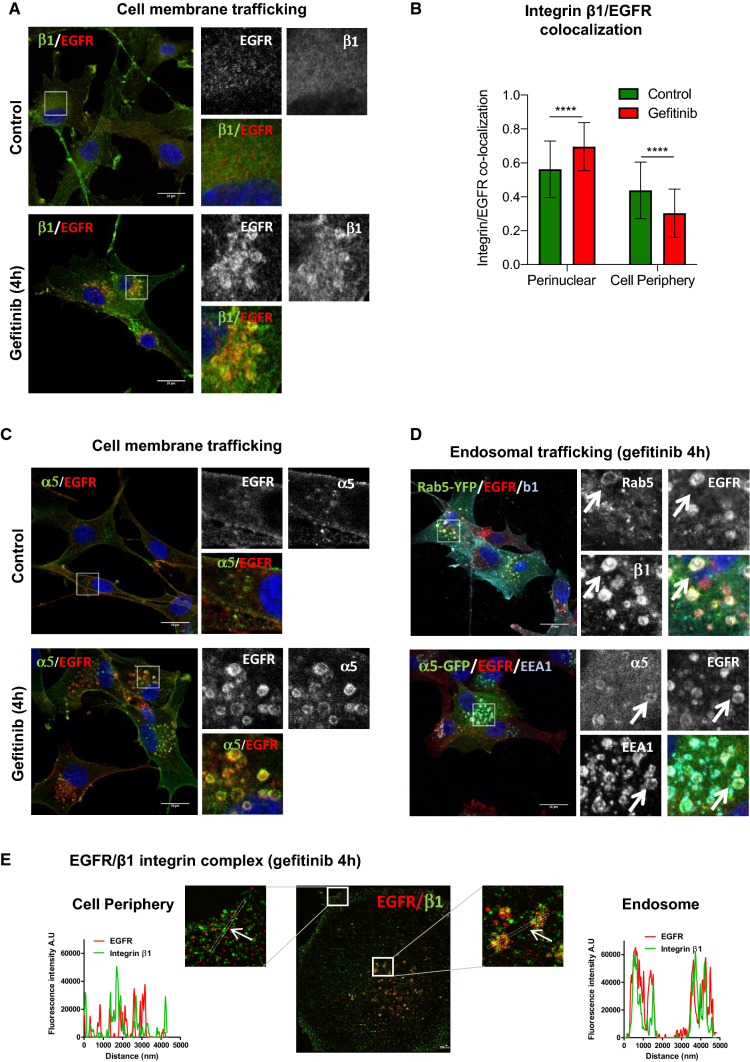

Fig. 2.

Gefitinib provokes the co-endocytosis of EGFR and α5β1 integrin. a–c Confocal images of U87 cells treated with vehicle (control) or gefitinib. Immunodetection of EGFR and β1 (a) or α5 (c) integrin subunits by confocal microscopy. Scale bar = 20 μm. b Quantification of the ratio β1 integrin/EGFR colocalized pixels in the perinuclear compartments compared to the cell periphery. The degree of colocalization between the β1 integrin and EGFR was quantified using a home-made plugin with the ImageJ software. d Confocal images of U87 cells expressing Rab5-YFP or α5-eGFP and treated with 20 µM of gefitinib. High magnification images of the inserts at the peri-nuclear area. Arrows highlight vesicles that are labelled with both EGFR, integrin and early-endosome marker. Scale bar = 20 μm. e Two-color dSTORM images of gefitinib-treated cells showing EGFR/β1 integrin complex at the cell periphery and endosomes. High magnification images of the inserts at the cell periphery and endosomes are shown. Plot profiles of pixel intensity of EGFR (red) and β1 integrin (green) corresponding to the region marked with white arrows. Scale bar = 200 nm

EGF endocytosis and uptake quantification

EGF coupled to AlexaFluor488 (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen) was used to study the ligand-induced EGFR internalization. To this end, cells were plated on coverslips previously coated with fibronectin (20 µg.mL−1 in DPBS). Cells were starved in OptiMEM (Gibco) for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were first washed in ice-cold DPBS and then incubated on ice in OptiMEM medium containing 100 ng.mL−1 AlexaFluor488–EGF. After incubation on ice for 30 min, cells were gently washed in ice-cold DPBS. Cells kept at 4°C were used as a negative control. Otherwise, cells were incubated with pre-warmed complete medium at 37 °C during 1 h in presence of gefitinib as indicated. Remaining cell surface EGF was removed by acid wash (sodium acetate 0.2M pH 2.7 for 5 min on ice), cells were fixed and nucleus stained with DAPI. Images were acquired using a confocal microscope. The analysis was performed after a threshold (identical for all conditions) applied to eliminate the background. The integrated fluorescence intensity of EGF-Alexa488 was determined in each cell. Image analysis was performed using ImageJ in between 20–30 cells per condition on 3 independent experiments.

Endocytosis of biotinylated cell-surface EGFR

Subconfluent cells were placed on ice during the following steps to prevent internalization. Cells were washed with ice-cold Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution containing 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 1.26 mM CaCl2 (Ca/Mg-HBSS) adjusted to pH 8, followed by incubation with 1 mg/ml EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in Ca/Mg-HBSS for 30 min, and washed with ice-cold Ca/Mg-HBSS. Free biotin was quenched with 20 mM glycine in Ca/Mg-HBSS for 15 min, then cells were washed with Ca/Mg-HBSS before internalization assays.

Following cell-surface biotinylation, cells were incubated 2 h at 37 °C in 10% FBS-containing medium (with or without 15 µM Gefitinib), to allow endocytosis. Cells were quickly replaced on ice, washed three times with ice-cold Ca/Mg-HBSS, then washed twice with 300 mM MESNa in the appropriate buffer (Tris 50 mM pH 8,6, NaCl 100 mM, EDTA 1 mM, BSA 0,2%) in the dark, for 15 min to remove biotin to cell-surface proteins. Cells were rinsed twice with Ca/Mg-HBSS, incubated with iodoacetamide (5 mg/ml) in Ca/Mg-HBSS for 10 min in dark, and subsequently washed with Ca/Mg-HBSS. To determine the total amount of surface biotinylation and to serve as a control, one dish was kept on ice after biotin labeling and preserved from MESNa treatment. Whole-cells extracts were prepared as described above and biotinylated proteins were recovered from 100 µg of cell lysate by using avidin protein immobilized on agarose beads, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and revealed by immunoblotting with the anti-EGFR antibody.

STORM imaging and analysis

Samples were prepared as previously described for confocal microscopy, except that cells were incubated with quantum dot 655 (Invitrogen). Super-resolution imaging was performed on an inverted microscope Nikon Eclipse Ti-E (Nikon) equipped with 100 ×, 1.49 N.A. oil-immersion objective. Fluorescence signal was collected with an EM-CCD camera (Hamamatsu) using a previously optimized protocol [42]. Image reconstruction was performed using Thunderstorm, quantum dots were used for drift correction of both channels. The reference image with TetraSpek beads (ThermoFischer) was acquired to correct the lateral shift and chromatic aberrations (UnwarpJ plugin, ImageJ) between the two channels.

Spheroid migration assays

Single-cell suspension was mixed in EMEM/10% FBS containing 10% of methylcellulose. All the spheroids were made with 1000 cells by hanging drop method in a 20 μL drop as previously described [40]. Tissue culture plates were coated with fibronectin (20 µg.mL−1 in DPBS solution) for 2 h at 37 °C. Two-day-old spheroids were allowed to adhere and migrate in complete medium ± gefitinib (EMEM, 10% FBS). Twenty-four hours later, cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde 3.7% and stained with DAPI. Nucleus were picturized under the 5 × objective a Zeiss-Axio fluorescence microscope. Image analysis to evaluate the number of cells that migrated out of the spheroid was performed with ImageJ software using a homemade plugin [40]. Alternatively, phase-contrast time-lapse images were acquired using a Leica DMIR2 microscope (5xNPlan 0.25NA objective) equipped with a 37 °C 5% CO2 control system (Life imaging Services) with Leica DCF350FX CCD camera piloted by the FW4000 software (1 image every 10 min.). Thirty randomly chosen cells per spheroids using (4–5 spheroids per assays) were tracked using MTrackJ plugin [43], average speed and average directionality (average ratio of the distance to the origin) were quantified. Phase-contrast images (EVOS Xl, Core5 × magnification, Thermo Scientific) were acquired. For 3D evasion assays, collagen/fibronectin gels were made as described [44] except that fibronectin (20 µg.mL−1) was added to the collagen solution prior polymerization.

Immunoblot

Equivalent amounts of proteins were separated on precast gradient 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare). Membranes were probed with primary antibodies; anti-EGFR antibody (D38B1), anti-α5 integrin (H104) at 1 µg/ml and anti-GAPDH at 0.2 µg/ml in blocking solution (PBS- 5% non-fat dry milk). Immunological complexes were revealed with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG coupled peroxidase antibodies using chemoluminescence (ECL, Bio-Rad) and visualized with LAS4000 image analyser (GE Healthcare). Quantification of non-saturated images was performed with ImageJ software. GAPDH was used as the loading control for all samples.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as Tukey’s box and whiskers unless otherwise stated. Statistical analysis between samples was done by one-way analysis of the variance (ANOVA) corrected by Bonferroni post-test with the GraphPad Prism program unless otherwise stated. Significance level is controlled by a 95% confidence interval.

Results

Gefitinib provokes EGFR endocytosis

EGFR trafficking dysregulation participates to GBM progression and aggressiveness. However, the significance and the role of TKIs on EGFR trafficking remain unclear [38, 45]. To address this question, we treated U87 GBM cells with gefitinib and examined EGFR localization by confocal microscopy (Fig. 1a). In untreated control cells, EGFR labelling was diffused and poorly localized in early endosome antigen-1 (EEA1)-positive endosomes. Remarkably, after 4 h of treatment, gefitinib provoked a massive re-localization of EGFR in EEA1-positive endosomes. These endosomes were enlarged compared to control cells suggesting endosomes fusion and/or endosomal arrest. Gefitinib-mediated EGFR re-localization to early endosomes was observed at gefitinib concentrations ranging from 5 µM to 20 µM (data not shown). Quantification of EEA1/EGFR co-localization revealed that EGFR distribution in early endosomes increased after 1 h of treatment (Fig. 1b).

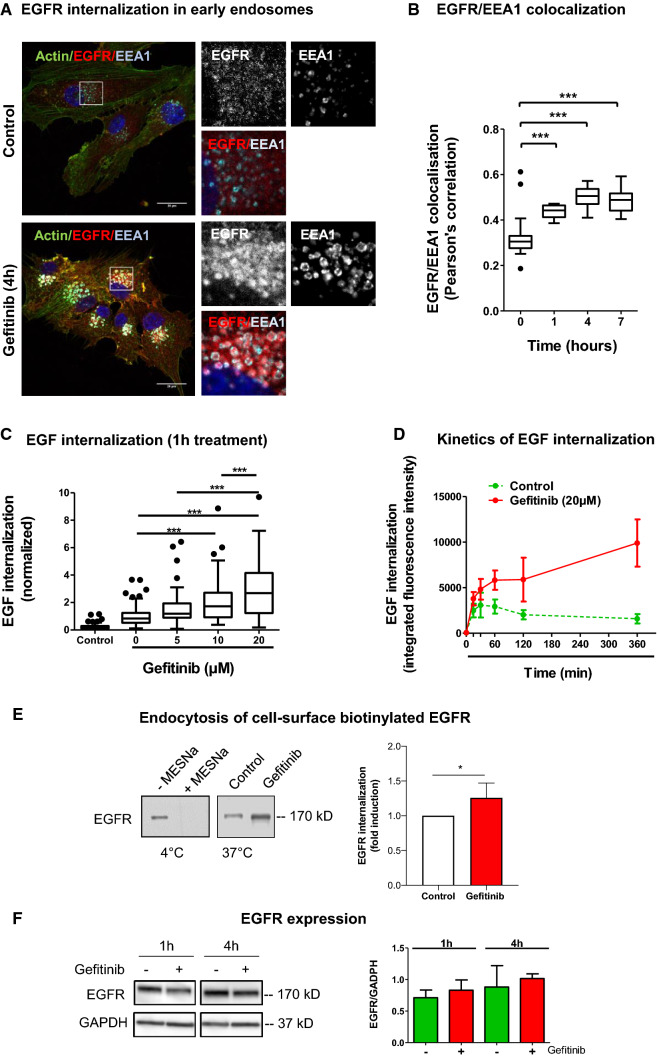

Fig. 1.

Gefitinib provokes EGFR endocytosis in U87 cells. a Immunodetection of actin (green), EGFR (red) and the endosomal marker EEA1 (cyan) after 4 h treatment with DMSO (control cells) or gefitinib (20 µM). Magnified images are from the inserts to the peri-nuclear area. Scale bar = 20 μm. b EGFR/EEA1 colocalization following gefitinib treatment. We collected 10–12 images from 3 independent experiments. ***p < 0.001. c–d EGF-Alexa488 internalization in U87 cells. Following serum-starvation and EGF-Alexa488 binding to the cell surface, cells were replaced in complete medium at 37 °C to allow internalization of the ligand, in presence of the indicated concentration of gefitinib. The internalization was measured by integrated fluorescence density of 20–30 cells from 3 independent experiments. c Cells were treated with different concentrations of gefitinib (5-20 µM) for 1 h at 37 °C incubation. ***p < 0.001. d Cells were treated with 20 µM of gefitinib for 15 min to 6 h. Data are represented as mean ± s.d. e Left panel: Immunoblot showing the endocytosis of biotinylated EGFR. Following cell-surface biotinylation, cells were incubated in complete media (with or without 15 µM gefitinib) for 3 h. Cells were treated with MESNa agent to remove biotin present on cell-surface proteins. After purification, biotinylated proteins were then subjected EGFR immunoblot. Right panel: Quantification of EGFR protein bands (mean of 4 independent experiment). *p < 0.05. f Left panel: Immunoblot showing similar EGFR protein expression in gefitinib-treated and untreated cells. Right panel: Quantification of EGFR/GAPDH protein ratio (mean of 3 independent experiments)

Using an EGF-internalization fluorescent assay, we showed that gefitinib strongly increased EGF endocytosis from the cell surface in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1c). Time-course experiments confirmed that gefitinib increased EGFR endocytosis within 30 min after treatment initiation. Moreover, fluorescent EGF accumulated for hours in gefitinib-treated cells, whereas in untreated cells, we measured a slow decrease of intracellular fluorescent EGF (Fig. 1d). To confirm these results, we conducted endocytosis assays of cell-surface biotinylated EGFR (Fig. 1e). Densitometric quantification of EGFR immunoblot revealed a 25% increase of internalized EGFR. Importantly, short-term gefitinib treatment had no impact on total EGFR expression level in U87 cells (Fig. 1f). Considering glioblastoma heterogeneity, we analysed the effect of gefitinib on EGFR distribution in 3 other cell lines presenting a various level of EGFR expression (Supplemental Fig. 1e). We showed that gefitinib increased EEA1/EGFR colocalization in T98G and LN443 cells (Supplemental Fig. 1a, b) and EGF endocytosis in LN443, T98 and LNZ308 cells (Supplemental Fig. 1c, d). These experiments indicated that in vitro, gefitinib led to massive EGFR endocytosis in GBM cells.

Integrin and EGFR are co-recruited to early-endosomes by gefitinib treatment

Our previous experiments clearly showed that gefitinib strikingly increased EGFR endocytosis rate. Integrin α5β1 promotes EGFR recycling [29] and a genome-wide gene screening identified α5β1 integrin as a strong promotor of EGFR endocytosis [30]. We thus hypothesized that α5β1 integrin, a potential therapeutic target in GBM [32, 34] may have an impact on gefitinib-mediated EGFR endocytosis.

We first examined the impact of gefitinib on α5β1 integrin localization. Integrin/Rab5 colocalization was examined by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 2a, b, gefitinib triggered β1 integrin relocalization in Rab5-positive early endosomes. We next examined whether EGFR and integrin are transported to the same endosomes. In untreated cells, α5β1 integrin and EGFR were detected at the plasma membrane or as punctate intracellular staining (Fig. 2a). Surprisingly, upon short-term gefitinib treatment, α5β1 integrin was clearly redistributed into large EGFR-positive endosomes (Fig. 2a–c). As cells presented a dense EGFR and integrin co-labelling at the level of the plasma membrane (mainly due to membrane ruffling), we quantified the integrin/EGFR colocalized pixels ratio at the cell periphery or in the endosomes enriched perinuclear region. As shown in Fig. 2b, gefitinib treatment increased integrin/EGFR colocalization in the perinuclear region compared to untreated condition, indicating a recruitment of both receptors in the same endosomes. We next performed immunolabeling and confocal analysis of U87 cells that transiently expressed either α5-GFP or Rab5-YFP. Upon gefitinib treatment, integrin β1 and EGFR were both localized in Rab5-positive early-endosomes (Fig. 2d). Similarly, EGFR and α5-GFP were both found in EEA1-positive early-endosomes (Fig. 2d). We next performed 2-color dSTORM super-resolution microscopy to confirm a potential interaction between the integrin and EGFR in early-endosomes (Fig. 2e). In gefitinib-treated cells, plot profile views revealed a strong overlay of EGFR and integrin β1 labelling in endosome-like structures but not at the cell periphery, suggesting that these two receptors are more likely to interact in endosomes than at the plasma membrane (Fig. 2e). Additionally, we showed that not only first-class reversible TKI (erlotinib) but also second-generation irreversible TKIs which covalently bind to EGFR (lapatinib, afatinib, dacomitinib) provoked EGFR/β1 integrin co-redistribution in endosomal compartments (Supplemental Fig. 3a). Finally, upon gefitinib treatment, we observed endosomal integrin/EGFR co-labelling in three additional GBM lines (LN443, LNZ308 and T98) (Supplemental Fig. 4).

Taken together, these data showed for the first time that EGFR TKIs increased EGFR endocytosis and α5β1 integrin co-accumulation in early endosomes of GBM cells.

Knock-down of α5β1 integrin reduced gefitinib-mediated EGFR endocytosis

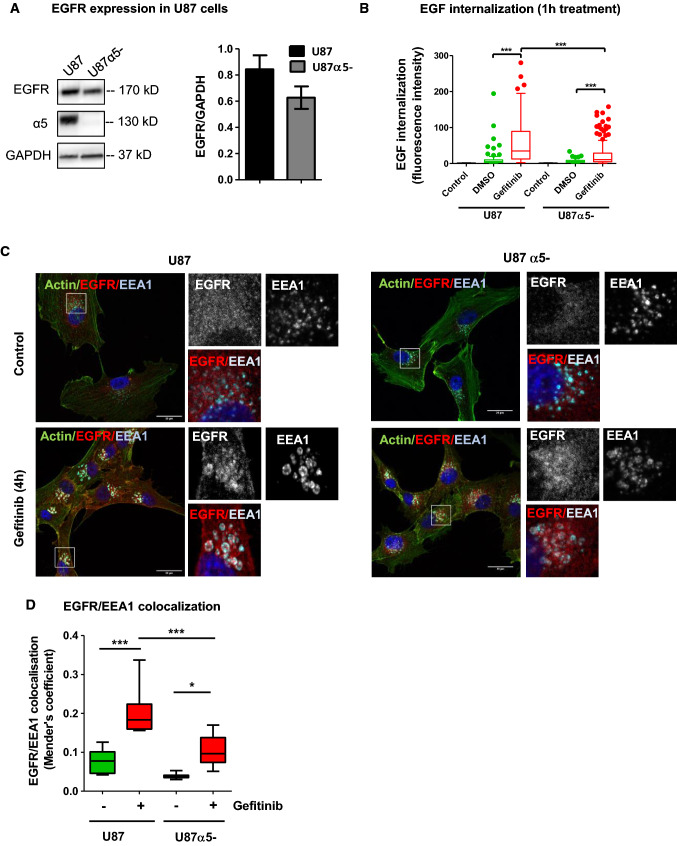

We next examined whether integrin α5 gene silencing may affect gefitinib-mediated EGFR endocytosis. We first controlled by immunoblot, that loss of α5 expression did not change EGFR expression level (Fig. 3a) and that EGFR expression was not altered by gefitinib treatment in both cell lines (Supplemental Fig. 5a). Similarly, we showed that the effect of gefitinib on cell proliferation and cell survival was not dependant on α5 expression in U87 cells (Supplemental Fig. 6). By contrast, EGF internalization assays showed that EGFR endocytosis was significantly reduced in α5-negative cells (U87 α5-) (Fig. 3b). Analysis of EGFR/EEA1 colocalization by confocal images revealed that loss of α5 expression limited the internalization and accumulation of EGFR in early-endosomes during short-term gefitinib treatment (Fig. 3c, d). These data support the hypothesis of a functional relationship between integrin α5β1 and EGFR and suggest that α5β1 integrin expression may contribute to gefitinib-mediated EGFR endocytosis.

Fig. 3.

Silencing of α5β1 integrin delayed gefitinib-mediated EGFR endocytosis. a Left panel: U87 and U7α5- cell lysates were immunoblotted to detect EGFR, α5 integrin and GAPDH. Right panel: densitometric analysis. b EGF-Alexa488 internalization assays in U87 cells and U87α5-. Following serum-starvation and EGF-Alexa488 binding to the cell surface, cells were replaced in complete medium at 37 °C to allow internalization of the ligand in presence of gefitinib (20 µM) or DMSO. The internalization was measured by integrated fluorescence density on 20–30 cells/experiment of 3 independent experiments and reported in the histogram by arbitrary units of fluorescence (AUF). ***p < 0.001. c Confocal microscopy detection of actin filaments (green), EGFR (red) and EEA1 (cyan) in U87 and U87α5- cells treated with vehicle (control) or gefitinib (20 µM, 4 hours). High-magnification images are from the inserts into the peri-nuclear area. Scale bar = 20 μm. d EGFR/EEA1 colocalization using Mender’s coefficient. Confocal images from 3 independents experiments were analyzed with JACOPs plugin of ImageJ software

α5β1 integrin expression decreases EGFR-TKIs efficacy during cell dissemination from GBM spheroid

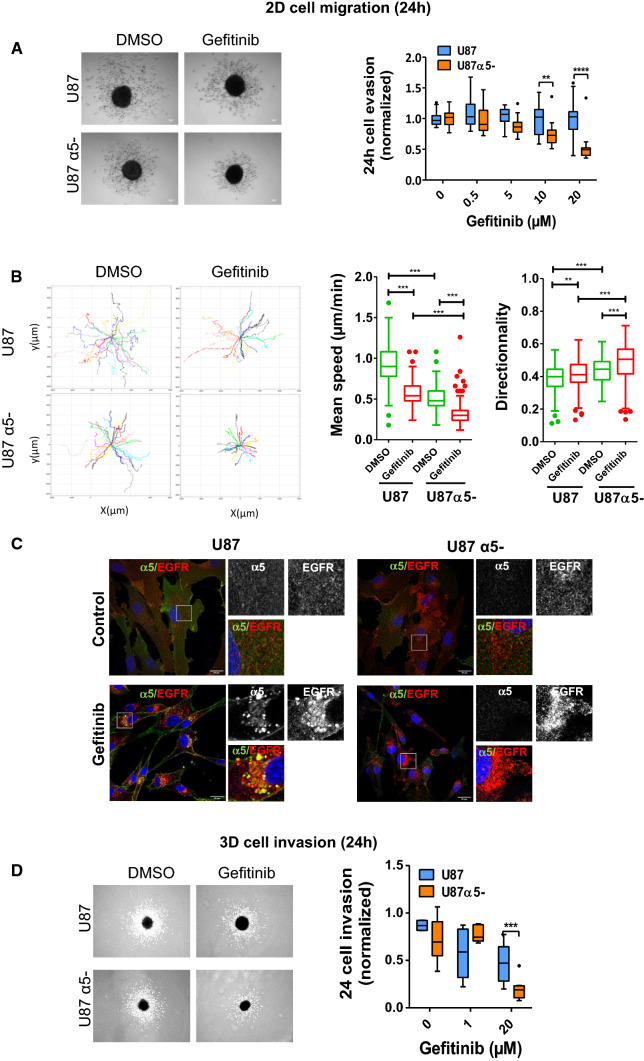

In ovarian cancer cells, the co- trafficking of α5β1 integrin and EGFR is critical for cell migration and invasion [46, 47]. We thus hypothesized that the potential interaction between EGFR and α5β1 in early-endosomes of gefitinib-treated cells may impact on glioma cell migration and invasion. Tumour spheroids are reliable models of solid tumours and are increasingly used to decipher molecular mechanisms of cancer cell migration and resistance to therapy [40]. We thus compared the role of gefitinib on cell evasion from spheroids in α5-expressing and α5-depleted cells (Fig. 4). Phase-contrast microscopy indicated that in presence of gefitinib U87α5- cells poorly escape from spheroids compared to control cells (Fig. 4a). Quantification of the number of evading cells, showed that gefitinib decreased the number of evaded cells from U87α5- spheroids in a dose dependent way, but did not significantly affect evasion of U87 parental cells (Fig. 4a). Using video microscopy, we analysed the trajectories of individual cells migrating away from the spheroids. Figure 4b showed that in all experimental conditions, cells migrated radially from the spheroids. We also noticed that loss of α5 integrin as well as gefitinib treatment slightly increased cell directionality, suggesting changes in direction sensing or planar polarity. As expected, α5β1 expression enhanced cell speed both in control and gefitinib-treated cells (Fig. 4b). However, we described that gefitinib significantly reduced both U87 and U87α5- cell speed (Fig. 4b). We then analysed EGFR and integrin localization in cells migrating at long distance from the spheroids. In U87 parental cells, EGFR was found in α5β1-positive endosomes, which is consistent with a co-trafficking of both receptors during cell migration (Fig. 4c-left panel). This result highlights that gefitinib had long term effect on EGFR and integrin co-trafficking. Interestingly, in α5-depleted glioma cells (Fig. 4c-right panel), we also observed enhanced EGFR internalization in gefitinib-treated cells compared to control cells, indicating that loss of α5-integrin expression reduced but did not suppress gefitinib-mediated endocytosis. Confocal images analysis confirmed that α5-integrin silencing reduced the number of β1 integrin/EGFR colocalized pixels in perinuclear region of migrating cells (Supplemental Fig. 5). We then compared the efficacy of 4 TKIs and confirmed that α5β1 integrin expression may trigger resistance to EGFR TKIs during U87 cell evasion from tumour spheres (Supplemental Fig. 3b). Finally, experiments performed with spheroids embedded in collagen/fibronectin matrix showed that α5β1-depleted U87 cells were more sensitive to gefitinib treatment than parental α5β1-expressing cells in 3D environment (Fig. 4d). In conclusion, we showed that EGFR-targeting TKIs induced EGFR/integrin co-endocytosis and trafficking, and that α5β1 expression stimulated evasion of TKIs-treated cell.

Fig. 4.

Silencing of α5β1 integrin sensitizes GBM cells to gefitinib treatment during GBM cell evasion in 2D and 3D environment. a Phase-contrast image of representative spheroids after 24 h of migration in the presence of DMSO or gefitinib (20 µM). Scale bar = 100 µm. After DAPI staining, the number of evading cells were quantified by automated counting of nuclei using an ImageJ homemade plugin. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. b Left panels show the migratory tracks of individual cells. Right panels: Mean speed and directionality of DMSO or gefitinib-treated escaping cells (30 cells/spheroids, 5 spheroids/experiment, 3 independent experiments).**p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. c EGFR and α5 integrin are co-distributed in intracellular compartment of cells migrating at long distance during 24 h of gefitinib treatment. Confocal microscopy detection of EGFR and α5 integrin in cells treated with DMSO (control) or gefitinib. High magnification images are from the inserts into the peri-nuclear area. Scale bar = 20 μm. d Left panel: Phase-contrast image of representative spheroids embedded in collagen/fibronectin 3D matrix after 24 h of invasion in the presence of DMSO or gefitinib (20 µM). Scale bar = 100 µm. Right panel: Curve-dose effect of gefitinib on cell invasion was quantified using ImageJ. Quantification of 15 spheroids from 3 independent experiments, normalized to the control cells. ***p < 0.001

Discussion

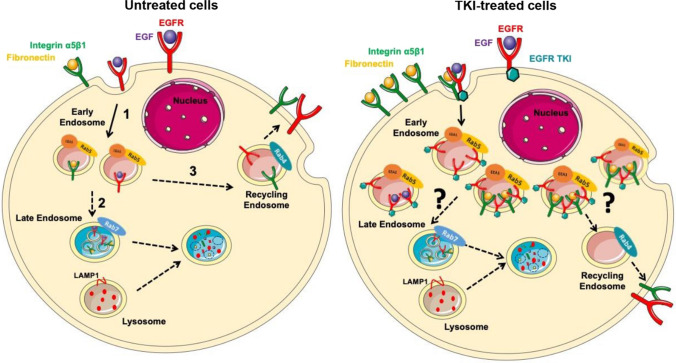

Gefitinib is a potent tyrosine kinase inhibitor of EGFR, used in cancer treatment. Despite the key role of EGFR in glioblastoma aggressiveness and progression, gefitinib did not improve the management of patients with a brain tumour [4, 5]. As membrane trafficking is a key regulator of EGFR function in cancer cells [6], and is often altered in GBM cells [12, 18, 22], we seek to study the impact of gefitinib treatment on EGFR trafficking. In this study, we showed that in a glioma cellular model, acute gefitinib treatment induced an intense EGFR endocytosis, a process we called gefitinib-mediated endocytosis (GME). GME is not specific to EGFR, as we observed a strong re-localization of the fibronectin receptor α5β1 integrin in EGFR-positive early endosome and a co-trafficking of both receptors under gefitinib treatment (Fig. 5). Moreover, we suggest that α5β1 integrin may play a role in this process as shRNA-mediated depletion of α5 integrin reduced EGFR GME. We showed that integrin expression is associated with a reduced gefitinib potency to inhibit cell dissemination from tumour spheroids. This suggests that in gefitinib-treated glioma cells, proteins involved in GME and in this altered EGFR trafficking, may affect cell response to gefitinib. The presence of integrin in EGFR-positive endosomes may modulate cell sensitivity to TKI during cell invasion. Our work underlines new properties of TKIs that need to be further investigated to improve cancer cell response to treatment.

Fig. 5.

Proposed mechanism of gefitinib-mediated endocytosis of EGFR and α5β1 integrin in glioma cells. In untreated cells, upon ligand-binding, EGFR is internalized into early endosomes (1). EGF receptors are sorted to different fates, either degradation (2) or recycling (3), accordingto receptor-ligand dissociation. Ligand-bound receptors are led to degradation by the maturation of early-to-late endosomes and further fusion with lysosomes (2). Otherwise, EGFR can be recycled back to the plasma membrane (3). Upon treatment with an EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), EGFR is massively internalized into enlarged and abundant early endosomes (4). This massive internalization seems to happen to both bound and unbound EGFR. Moreover, TKI treatment also caused internalization of other membrane receptor such as the α5β1 integrin. EGFR and integrin were found together in early endosomes (5). After endocytosis, the journey of integrin and EGFR remains to be clarified and might modulate invasive behaviour of glioma cells under treatment

Here, we clearly established that gefitinib treatment provoked endosomal accumulation of EGFR, partially due to a strong increase in endocytosis. Indeed, we cannot completely rule out that EGFR accumulation in endosomes can also be the consequence of a dysregulated trafficking of neo-synthetized EGFR. Altered EGFR trafficking is sustained as observed on the immunofluorescence images of migrating cells that were treated with gefitinib for 24 h. While surprising, our data are in agreement with a recent study showing that gefitinib can trigger EGFR accumulation in endosomes of breast cancer cells [37]. While physiological EGFR endocytosis upon ligand-binding is well characterized [48], we still don’t know the driven mechanism of GME. Because gefitinib inhibits EGFR tyrosine kinase activity, we speculate that GME occurs independently of EGFR activity. Moreover, we observed that both ligand-bound and ligand-free EGFR (i.e. in serum-free medium, data not shown) were susceptible to GME. Stress-mediated by chemotherapeutic drugs elicits non-physiological EGFR endocytic trafficking dependant on p38-MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) activity [37, 45, 49–52]. In agreement to our own observations, in these processes, EGFR re-localization into intracellular compartments can occur independently of EGF binding [37, 51] or tyrosine-kinase domain activation [37]. Indeed, p38-MAPK can trigger Rab5 pathway activation to promote EGFR endocytosis [53, 54]. Rab5 activation by off-target effect seems to be a common mechanism for drug-induced EGFR endocytosis [55]. Future experiments will determine if Rab5 or p38-MAPK are involved in GME of EGFR and integrin.

In addition to a potential stress-induced endocytosis of EGFR and integrin in gefitinib treated cells, it has been observed that lipophilic drug with a weak basic moiety, such as gefitinib, can become protonated and trapped within acidic intracellular compartment such as lysosomes. Gefitinib lysosomotropism has already been described in normal cells [56, 57]. Furthermore, lysosomal sequestration of gefitinib and other TKI has been reported in cancer cells derived from lung, colon, breast or ovarian carcinomas [58–60]. Whereas these works described that drug retention in lysosomes is associated with therapeutic resistance of cancer cell, a more recent study indicates that lysosomal sequestration of TKIs does not affect their cytosolic and extracellular concentrations, which is not in a favour for a role of TKI accumulation in an acidic compartment in drug resistance [61]. Interestingly, hydrophobic weak base therapeutic drugs increase lysosomal activity in a breast cancer cell line [59]. Moreover, proteomic analysis revealed that gefitinib treatment of lung cancer cells increased the expression or the ubiquitination level of numerous proteins involved in lysosomal and endocytic pathways [62]. Therefore, it will be interesting to determine in the future whether GME of EGFR and α5β1 integrin described herein might be the consequence of an alteration of the endocytic pathway triggers by TKI sequestration in the acidic compartment.

In summary, this study described a novel role of TKIs in EGFR/α5β1 integrin endocytosis and membrane trafficking. As these receptors play a critical function in cancer cell invasion and dissemination, future challenges would evaluate TKIs impact on integrin biological functions and how integrin/EGFR altered endocytosis in TKIs-treated cells may contribute to GBM cell evasion. Finally, a recent report highlighted the underestimated importance of the off-target cytotoxicity of targeted therapies [63]. This work emphasized the need to better understand drug mechanisms to identify appropriate biomarkers predicting drug efficacy. Thus, it will be important in the future to depict the impact of drugs such as gefitinib on endosomal trafficking and uncover molecules involved in these mechanisms. This may provide rationales for novel treatment protocols and improve precision medicine approach for brain tumours.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1Supplemental Figure 1: Gefitinib provokes EGFR endocytosis in GBM cells. (A) Immunodetection of EGFR (red) and the endosomal marker EEA1 (green) after 4h treatment with DMSO (control) or gefinitib in LN443 and T98G GBM cells. Magnified images are from the inserts to the peri-nuclear area. Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) Quantification of EGFR/EEA1 colocalization following gefitinib treatment from 10–12 images (3 independent experiments). ***p < 0.001. (C-D) Endocytosis assays of EGF-Alexa488 was performed on LN443, T98G and LNZ308 cells during 1h in presence of gefitinib (20µM). The internalization was measured by integrating fluorescence density of 20-30 cells from 3 independent experiments. ****p < 0.0001. (E) Immunoblot showing α5 integrin and EGFR expression in the 4 cell lines used in this study. Supplemental Figure 2: Gefitinib provokes integrin re-localization in early endosomes. (A) Fluorescence microscopy images of U87 cells treated with gefitinib showing peri-nuclear co-localization of the β1 integrin (cyan) and the early-endosome marker Rab5 (red). (B) The Pearson correlation and Mender’s coefficient were used to quantify the degree of colocalization between the β1 integrin and Rab5. ***p < 0.001. Supplemental Figure 3: Second and third-generation TKIs also induce co-internalization of β1 integrin and EGFR during U87 GBM cell evasion. (A) Confocal images of U87 cells treated with vehicle (control) or TKIs gefitinib (20 µM), afatinib (5 µM), erlotinib (10 µM), dacomitinib (10 µM) or lapatinib (10 µM). Images are representative of 3 independent experiments. High-magnification images are from the inserts into the peri-nuclear area. Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) Quantification of the number of evading cells from U87 and U87α5- treated spheroids. Spheroids were incubated for 24 hours in the presence of DMSO or different TKIs (erlotinib, dacomitinib, lapatinib and afatinib) at the indicated concentrations. Nuclei were stained with DAPI and the number of evading cells was quantified using an ImageJ homemade plugin. Mean of 15 spheroids from 3 independent experiments. **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Supplemental Figure 4: Gefitinib treatment provokes integrin/EGFR relocalization in endosomal compartments of GBM cell lines. Confocal images showing the intracellular distribution (perinuclear region enriched in endomembrane) of EGFR and β1 integrin in LN443, T98G and LNZ308 gefitinib-treated cells. Supplemental Figure 5: Gefitinib treatment does not affect the expression of total EGFR in U87 cells. Left panel: A) Protein expression of EGFR and α5 integrin in U87 GBM cells and U87α5- cells after 24h treatment with DMSO (-) or gefitinib 20µM (+). GADPH was used as loading control. Right panel: Histogram showing the quantification of GADPH-normalized EGFR level of 3 independent experiments. Data represented are the mean +/- s.e.m. B) Quantification of the ratio integrin/EGFR colocalized pixels in the perinuclear compartments of U87 or U87α5- cells that migrated at distance from spheroids after 24 hours of incubation in presence of 20µM gefitinib or DMSO (control). The degree of colocalization between the β1 integrin and EGFR was quantified using an home-made plugin with the ImageJ software. Data expressed as box and whiskers are from at least 30 cells from 10 different fields. Supplemental Figure 6: α5 expression does not affect U87 cell sensitivity to gefitinib in cell growth and cell survival experiments. (A) 2D growth curve of U87 and U87α5- cells in serum-containing medium. (B) Gefitinib dose-response curve on cells growth in 2D after 3 days of treatment. (C) Left panel: phase contrast images of spheroids after 8 days of treatment with indicated concentration of gefitinib. Right panel: dose-response curves of gefitinib on spheroid growth. D) Clonogenic assay in soft agar comparing U87 and U87α5- cell survival in presence of the indicated concentrations of gefitinib. (PPTX 20689 kb)

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Ligue Contre le Cancer, Région Grand-Est, programme-inter region (No S17R417B). Elisabete Cruz Da Silva and Anne-Florence Blandin were PhD students funded by the University of Strasbourg. Marie-Cécile Mercier was a pharmacy intern funded by ARS Grand Est (regional health agency). We thank Romain Vauchelles and the PIQ platform (IBiSa Quest imaging facility) for their assistance in image quantification.

Author contribution

Participated in research design: ML, MD, LC, PD. Conducted experiments: AFB, ECS, MCM, OG, NES, SD, CS, JD. Performed data analysis: AFB, ECS, MCM, SD, CS, JD. Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: AFB, ECS, SD, LC, ML. All of the authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Anne-Florence Blandin, Elisabete Cruz Da Silva contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Anne-Florence Blandin, Email: anne-florence_blandin@dfci.harvard.edu.

Maxime Lehmann, Email: maxime.lehmann@unistra.fr.

References

- 1.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan CW, Verhaak RGW, McKenna A, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell. 2013;155:462–477. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.An Z, Aksoy O, Zheng T, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and EGFRvIII in glioblastoma (GBM): signaling pathways and targeted therapies. Oncogene. 2018;37:1561–1575. doi: 10.1038/s41388-017-0045-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor TE, Furnari FB, Cavenee WK. Targeting EGFR for treatment of glioblastoma: molecular basis to overcome resistance. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2012;12:197–209. doi: 10.2174/156800912799277557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mellinghoff IK, Cloughesy TF, Mischel PS. PTEN-mediated resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor kinase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:378–381. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomas A, Futter CE, Eden ER. EGF receptor trafficking: consequences for signaling and cancer. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim HJ, Taylor LJ, Bar-Sagi D. Spatial regulation of EGFR signaling by Sprouty2. Curr Biol. 2007;17:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sousa LP, Lax I, Shen H, et al. Suppression of EGFR endocytosis by dynamin depletion reveals that EGFR signaling occurs primarily at the plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200164109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sigismund S, Avanzato D, Lanzetti L. Emerging functions of the EGFR in cancer. Mol Oncol. 2018;12:3–20. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong ESM, Fong CW, Lim J, et al. Sprouty2 attenuates epidermal growth factor receptor ubiquitylation and endocytosis, and consequently enhances Ras/ERK signalling. EMBO J. 2002;21:4796–4808. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh AM, Lazzara MJ. Regulation of EGFR trafficking and cell signaling by Sprouty2 and MIG6 in lung cancer cells. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:4339–4348. doi: 10.1242/jcs.123208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou X, Xie S, Wu S, et al. Golgi phosphoprotein 3 promotes glioma progression via inhibiting Rab5-mediated endocytosis and degradation of epidermal growth factor receptor. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:1628–1639. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu S, Fu J, Dong Y, et al. GOLPH3 promotes glioma progression via facilitating JAK2–STAT3 pathway activation. J Neurooncol. 2018;139:269–279. doi: 10.1007/s11060-018-2884-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park J-W, Wollmann G, Urbiola C, et al. Sprouty2 enhances the tumorigenic potential of glioblastoma cells. Neuro Oncol. 2018;20:1044–1054. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh AM, Kapoor GS, Buonato JM, et al. Sprouty2 drives drug resistance and proliferation in glioblastoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13:1227–1237. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0183-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Akhrass H, Naves T, Vincent F, et al. Sortilin limits EGFR signaling by promoting its internalization in lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1182. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01172-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson CM, Naves T, Vincent F, et al. Sortilin mediates the release and transfer of exosomes in concert with two tyrosine kinase receptors. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:3983–3997. doi: 10.1242/jcs.149336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kondapalli KC, Llongueras JP, Capilla-González V, et al. A leak pathway for luminal protons in endosomes drives oncogenic signalling in glioblastoma. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6289. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gomez Zubieta DM, Hamood MA, Beydoun R, et al. MicroRNA-135a regulates NHE9 to inhibit proliferation and migration of glioblastoma cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2017;15:55. doi: 10.1186/s12964-017-0209-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Pickin KA, Bose R, et al. Inhibition of the EGF receptor by binding of MIG6 to an activating kinase domain interface. Nature. 2007;450:741–744. doi: 10.1038/nature05998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferby I, Reschke M, Kudlacek O, et al. Mig6 is a negative regulator of EGF receptor–mediated skin morphogenesis and tumor formation. Nat Med. 2006;12:568–573. doi: 10.1038/nm1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying H, Zheng H, Scott K, et al. Mig-6 controls EGFR trafficking and suppresses gliomagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6912–6917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914930107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, Zhang Y, Skalski M, et al. microRNA-148a is a prognostic oncomiR that targets MIG6 and BIM to regulate EGFR and apoptosis in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1541–1553. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaidel-Bar R, ItzkovitzMa’ayan SA, et al. Functional atlas of the integrin adhesome. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:858–867. doi: 10.1038/ncb0807-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ivaska J, Heino J. Cooperation between integrins and growth factor receptors in signaling and endocytosis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:291–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cruz da Silva E, Dontenwill M, Choulier L, Lehmann M. Role of integrins in resistance to therapies targeting growth factor receptors in cancer. Cancers. 2019 doi: 10.3390/cancers11050692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seguin L, Kato S, Franovic A, et al. An integrin β3-KRAS-RalB complex drives tumour stemness and resistance to EGFR inhibition. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:457–468. doi: 10.1038/ncb2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barrow-McGee R, Kishi N, Joffre C, et al. Beta 1-integrin-c-Met cooperation reveals an inside-in survival signalling on autophagy-related endomembranes. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11942. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caswell PT, Chan M, Lindsay AJ, et al. Rab-coupling protein coordinates recycling of alpha5beta1 integrin and EGFR1 to promote cell migration in 3D microenvironments. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:143–155. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collinet C, Stöter M, Bradshaw CR, et al. Systems survey of endocytosis by multiparametric image analysis. Nature. 2010;464:243–249. doi: 10.1038/nature08779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaffner F, Ray AM, Dontenwill M. Integrin α5β1, the fibronectin receptor, as a pertinent therapeutic target in solid tumors. Cancers. 2013;5:27–47. doi: 10.3390/cancers5010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janouskova H, Maglott A, Leger DY, et al. Integrin α5β1 plays a critical role in resistance to temozolomide by interfering with the p53 pathway in high-grade glioma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3463–3470. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-4199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Renner G, Janouskova H, Noulet F, et al. Integrin α5β1 and p53 convergent pathways in the control of anti-apoptotic proteins PEA-15 and survivin in high-grade glioma. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:640–653. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maglott A, Bartik P, Cosgun S, et al. The small alpha5beta1 integrin antagonist, SJ749, reduces proliferation and clonogenicity of human astrocytoma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6002–6007. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Wang Z, Zhang Y, et al. Golgi phosphoprotein 3 sensitizes the tumour suppression effect of gefitinib on gliomas. Cell Prolif. 2019;52:e12636. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Z-X, Qu L-Y, Wen H, et al. Mig-6 overcomes gefitinib resistance by inhibiting EGFR/ERK pathway in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:7304–7311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan X, Thapa N, Sun Y, Anderson RA. A kinase-independent role for EGF receptor in autophagy initiation. Cell. 2015;160:145–160. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jo U, Park KH, Whang YM, et al. EGFR endocytosis is a novel therapeutic target in lung cancer with wild-type EGFR. Oncotarget. 2014;5:1265–1278. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishimura Y, Bereczky B, Ono M. The EGFR inhibitor gefitinib suppresses ligand-stimulated endocytosis of EGFR via the early/late endocytic pathway in non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Histochem Cell Biol. 2007;127:541–553. doi: 10.1007/s00418-007-0281-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blandin A-F, Noulet F, Renner G, et al. Glioma cell dispersion is driven by α5 integrin-mediated cell–matrix and cell–cell interactions. Cancer Lett. 2016;376:328–338. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bolte S, Cordelières FP. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J Microsc. 2006;224:213–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glushonkov O, Réal E, Boutant E, et al. Optimized protocol for combined PALM-dSTORM imaging. Sci Rep. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27059-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meijering E, Dzyubachyk O, Smal I (2012) Methods for cell and particle tracking. In: Methods in enzymology. Elsevier, pp 183–200 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Thuault S, Hayashi S, Lagirand-Cantaloube J, et al. P-cadherin is a direct PAX3–FOXO1A target involved in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma aggressiveness. Oncogene. 2013;32:1876–1887. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan X, Lambert PF, Rapraeger AC, Anderson RA. Stress-induced EGFR trafficking: mechanisms, functions, and therapeutic implications. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:352–366. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caswell PT, Chan M, Lindsay AJ, et al. Rab-coupling protein coordinates recycling of α5β1 integrin and EGFR1 to promote cell migration in 3D microenvironments. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:143–155. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muller PAJ, Caswell PT, Doyle B, et al. Mutant p53 drives invasion by promoting integrin recycling. Cell. 2009;139:1327–1341. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Caldieri G, Barbieri E, Nappo G, et al. Reticulon 3–dependent ER-PM contact sites control EGFR nonclathrin endocytosis. Science. 2017;356:617–624. doi: 10.1126/science.aah6152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zwang Y, Yarden Y. p38 MAP kinase mediates stress-induced internalization of EGFR: implications for cancer chemotherapy. EMBO J. 2006;25:4195–4206. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oksvold MP, Huitfeldt HS, Østvold AC, Skarpen E. UV induces tyrosine kinase-independent internalisation and endosome arrest of the EGF receptor. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:793–803. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tomas A, Vaughan SO, Burgoyne T, et al. WASH and Tsg101/ALIX-dependent diversion of stress-internalized EGFR from the canonical endocytic pathway. Nat Commun. 2015 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cao X, Zhu H, Ali-Osman F, Lo H-W. EGFR and EGFRvIII undergo stress- and EGFR kinase inhibitor-induced mitochondrial translocalization: a potential mechanism of EGFR-driven antagonism of apoptosis. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:26. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cavalli V, Vilbois F, Corti M, et al. The stress-induced MAP kinase p38 regulates endocytic trafficking via the GDI:Rab5 complex. Mol Cell. 2001;7:421–432. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Macé G, Miaczynska M, Zerial M, Nebreda AR. Phosphorylation of EEA1 by p38 MAP kinase regulates μ opioid receptor endocytosis. EMBO J. 2005;24:3235–3246. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen X, Wang Z. Regulation of epidermal growth factor receptor endocytosis by wortmannin through activation of Rab5 rather than inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:842–849. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nadanaciva S, Lu S, Gebhard DF, et al. A high content screening assay for identifying lysosomotropic compounds. Toxicol Vitro. 2011;25:715–723. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kazmi F, Hensley T, Pope C, et al. Lysosomal sequestration (Trapping) of lipophilic amine (Cationic Amphiphilic) drugs in immortalized human hepatocytes (Fa2N-4 Cells) Drug Metab Dispos. 2013;41:897–905. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.050054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Englinger B, Kallus S, Senkiv J, et al. Lysosomal sequestration impairs the activity of the preclinical FGFR inhibitor PD173074. Cells. 2018 doi: 10.3390/cells7120259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhitomirsky B, Assaraf YG. Lysosomal sequestration of hydrophobic weak base chemotherapeutics triggers lysosomal biogenesis and lysosome-dependent cancer multidrug resistance. Oncotarget. 2014;6:1143–1156. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gotink KJ, Broxterman HJ, Labots M, et al. Lysosomal sequestration of sunitinib: a novel mechanism of drug resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7337–7346. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruzickova E, Skoupa N, Dolezel P, et al. The lysosomal sequestration of tyrosine kinase inhibitors and drug resistance. Biomolecules. 2019 doi: 10.3390/biom9110675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li W, Wang H, Yang Y, et al. Integrative analysis of proteome and ubiquitylome reveals unique features of lysosomal and endocytic pathways in gefitinib-resistant non-small cell lung cancer cells. Proteomics. 2018;18:1700388. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201700388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin A, Giuliano CJ, Palladino A, et al. Off-target toxicity is a common mechanism of action of cancer drugs undergoing clinical trials. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaaw8412. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw8412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1Supplemental Figure 1: Gefitinib provokes EGFR endocytosis in GBM cells. (A) Immunodetection of EGFR (red) and the endosomal marker EEA1 (green) after 4h treatment with DMSO (control) or gefinitib in LN443 and T98G GBM cells. Magnified images are from the inserts to the peri-nuclear area. Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) Quantification of EGFR/EEA1 colocalization following gefitinib treatment from 10–12 images (3 independent experiments). ***p < 0.001. (C-D) Endocytosis assays of EGF-Alexa488 was performed on LN443, T98G and LNZ308 cells during 1h in presence of gefitinib (20µM). The internalization was measured by integrating fluorescence density of 20-30 cells from 3 independent experiments. ****p < 0.0001. (E) Immunoblot showing α5 integrin and EGFR expression in the 4 cell lines used in this study. Supplemental Figure 2: Gefitinib provokes integrin re-localization in early endosomes. (A) Fluorescence microscopy images of U87 cells treated with gefitinib showing peri-nuclear co-localization of the β1 integrin (cyan) and the early-endosome marker Rab5 (red). (B) The Pearson correlation and Mender’s coefficient were used to quantify the degree of colocalization between the β1 integrin and Rab5. ***p < 0.001. Supplemental Figure 3: Second and third-generation TKIs also induce co-internalization of β1 integrin and EGFR during U87 GBM cell evasion. (A) Confocal images of U87 cells treated with vehicle (control) or TKIs gefitinib (20 µM), afatinib (5 µM), erlotinib (10 µM), dacomitinib (10 µM) or lapatinib (10 µM). Images are representative of 3 independent experiments. High-magnification images are from the inserts into the peri-nuclear area. Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) Quantification of the number of evading cells from U87 and U87α5- treated spheroids. Spheroids were incubated for 24 hours in the presence of DMSO or different TKIs (erlotinib, dacomitinib, lapatinib and afatinib) at the indicated concentrations. Nuclei were stained with DAPI and the number of evading cells was quantified using an ImageJ homemade plugin. Mean of 15 spheroids from 3 independent experiments. **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Supplemental Figure 4: Gefitinib treatment provokes integrin/EGFR relocalization in endosomal compartments of GBM cell lines. Confocal images showing the intracellular distribution (perinuclear region enriched in endomembrane) of EGFR and β1 integrin in LN443, T98G and LNZ308 gefitinib-treated cells. Supplemental Figure 5: Gefitinib treatment does not affect the expression of total EGFR in U87 cells. Left panel: A) Protein expression of EGFR and α5 integrin in U87 GBM cells and U87α5- cells after 24h treatment with DMSO (-) or gefitinib 20µM (+). GADPH was used as loading control. Right panel: Histogram showing the quantification of GADPH-normalized EGFR level of 3 independent experiments. Data represented are the mean +/- s.e.m. B) Quantification of the ratio integrin/EGFR colocalized pixels in the perinuclear compartments of U87 or U87α5- cells that migrated at distance from spheroids after 24 hours of incubation in presence of 20µM gefitinib or DMSO (control). The degree of colocalization between the β1 integrin and EGFR was quantified using an home-made plugin with the ImageJ software. Data expressed as box and whiskers are from at least 30 cells from 10 different fields. Supplemental Figure 6: α5 expression does not affect U87 cell sensitivity to gefitinib in cell growth and cell survival experiments. (A) 2D growth curve of U87 and U87α5- cells in serum-containing medium. (B) Gefitinib dose-response curve on cells growth in 2D after 3 days of treatment. (C) Left panel: phase contrast images of spheroids after 8 days of treatment with indicated concentration of gefitinib. Right panel: dose-response curves of gefitinib on spheroid growth. D) Clonogenic assay in soft agar comparing U87 and U87α5- cell survival in presence of the indicated concentrations of gefitinib. (PPTX 20689 kb)