Abstract

Tumor cells, inflammatory cells and chemical factors work together to mediate complex signaling networks, which forms inflammatory tumor microenvironment (TME). The development of breast cancer is closely related to the functional activities of TME. This review introduces the origins of cancer-related chronic inflammation and the main constituents of inflammatory microenvironment. Inflammatory microenvironment plays an important role in breast cancer growth, metastasis, drug resistance and angiogenesis through multifactorial mechanisms. It is suggested that inflammatory microenvironment contributes to providing possible mechanisms of drug action and modes of drug transport for anti-cancer treatment. Nano-drug delivery system (NDDS) becomes a popular topic for optimizing the design of tumor targeting drugs. It is seen that with the development of therapeutic approaches, NDDS can be used to achieve drug-targeted delivery well across the biological barriers and into cells, resulting in superior bioavailability, drug dose reduction as well as off-target side effect elimination. This paper focuses on the review of modulation mechanisms of inflammatory microenvironment and combination with nano-targeted therapeutic strategies, providing a comprehensive basis for further research on breast cancer prevention and control.

Keywords: Inflammation, Tumor microenvironment, Breast cancer, Nanoparticle, Drug targeting, Chemotherapy

Introduction

The research on the relationship between inflammation and cancer has become popular since the nineteenth century. In 1989, Stephen Paget proposed the theory of “seed and soil” [1], which revealed the importance of TME in tumor development and drew attention to the interaction between tumor cells and microenvironment. In 1992, the tumor treatment strategies against tumor cells gradually shifted to simultaneously intervening TME. Hanahan D and Weinberg RA first summarized the features of TME in 2000, including chronic inflammation and immunosuppression. At present, extensive studies have been focused on inflammatory tissue repair and immune responses, which may be tumorigenic or anti-tumor. The degree of inflammation is closely related to the functions of the immune system, and chronic inflammation can lead to inappropriate immune responses and ultimately result in cancer progression.

Chronic inflammation maintains the local homeostatic balance especially and constructs the inflammatory TME, which provides conditions for breast cancer cell survival and production. TME is comprised of cellular components (e.g., cancer cells, endothelial cells, fibroblasts) and other non-cellular components (e.g., extracellular matrix, signal molecules) [2], showing characteristics of low vascular density, hypoxia, weak acidity, and reducibility, significantly different from normal tissue microenvironment. Under the inflammatory microenvironment, chronic inflammation and immunosuppression may show upregulation of inflammatory mediators and recruitment of immune cells such as macrophages and neutrophils, which usually indicates tumor promotion.

The development of breast cancer includes not only the changes of microenvironment, but also breast cancer cell adaptation to the microenvironment. Breast cancer cells can disturb the mechanisms of metabolic circumstances and change the tissue interstitial osmotic pressure. In addition, cancer cells secrete a large number of chemokines and growth factors to activate cancer proliferation [3]. The rapid growth of cancer cells induces abnormal angiogenesis and lactate acid accumulation, which leads to hypoxia and acidic conditions in the TME [4]. All the characteristics jointly affect the inflammation functions and thus reinforce the formation and evolution of breast cancer inflammatory microenvironment. As such, breast cancer cells and their life-supporting environment influence one another and the interaction between them demonstrates a vicious circle through the inflammation-cancer feedback loop.

Previous studies have revealed that TME has abnormal functions and acts a central role in tumor progression, one of the key factors contributing to the ineffectiveness of “cancer cell centric” therapies. There are only a few clinical drugs used to modulate the breast cancer microenvironment, such as using Aromatase Inhibitors (AIs) letrozole, anastrozole and exemestane [5] to modify the microenvironment, or applying metformin, an anti-diabetes drug in clinical trials, to regulate metabolism [6]. Although these drugs have significant therapeutic effects, there exist multiple limitations such as impermeable biological barriers, uneven drug distribution, and severe side effects. Recently, nanochemotherapy has become popular in oncology and it should stay for some time since it brought promising opportunities for cancer identification and treatment. The advantages of nanomedicines include high drug loads, long blood circulation and diffusion into tumor tissues. However, this kind of passive accumulation is not limit to tumor cells or tissues, difficult to achieve the ideal drug concentration in tumor tissues to induce cytotoxicity.

Considering these limitations, alternative approaches have been extensively explored to overcome these challenges. First, intracellular drug release is the key to the anti-tumor efficacy of nanomedicines to achieve tumor cell specific cell uptake. National and international researchers have been trying to identify underlying active ligands with high selectivity and affinity to modify the surface of nanoparticles. However, the targeted nanoparticles allowed for clinical application are only passive ones. Therefore, it is necessary to develop more effective delivery strategies. Based on the understanding of inflammatory microenvironment functions and characteristics in breast cancer, the nanoparticle-based targeted remedies of microenvironment have significant implications for cancer diagnosis and treatment. The peculiar characteristics of nanomedicines show great benefits to target typical processes associated with TME, including ameliorating inflammatory, acidic, and hypoxic states, abolishing immunosuppression, and inhibiting angiogenesis. For example, the pH-dependent release behaviors of nanoparticles with possibility of passing through biological barriers and targeting tumor microenvironment. The introduction of stimuli-responsive nanoparticles to a certain extent alleviates the non-specific uptake by RES (spleen, liver and lungs), mononuclear phagocyte system as well as kidney filtration [7].

This paper summarized the relationship between inflammation and cancer, as well as the constituents and activities of inflammatory microenvironment, and highlights its potential implications in breast cancer progression and treatment. It also discussed the treatment methods based on nanomedicines, where the main focus of the drug-targeted delivery approach is nanomedicines aiming at both tumor sites and tumor cells, providing a scientific basis for breast cancer-targeted therapy.

Inflammation and cancer

Cancer-associated inflammation

Inflammatory responses in fact are supposed to be the self-protection of human immune systems arising from vivo or vitro adverse stimuli, such as infection, mutation, and DNA damage. Generally, inflammation is beneficial for tissue repair and remodeling, which can be resolved in time and protect the body from potentially dangerous threats. When the dysregulation of inflammation leads to excessive or prolonged tissue damage, acute inflammation usually develops into chronic inflammation [8]. Definitely the chronic inflammatory conditions can be long-lived within the body and then lead to a variety of diseases, for instance, increasing vulnerability to carcinogenesis [9]. Although inflammation causes may vary in different subtypes of breast cancer, they are essential elements during the carcinogenic processes. There exist diverse kinds of extrinsic and intrinsic inflammatory factors for a long time before they induce breast cancer, including infectious viruses and germs, immune system diseases, gene mutations, unbalanced diet, and obesity [10]. These mechanisms, to some extent, contribute to chronic inflammation supported by inflammatory cells and cytokines. Under repeated exposure in inflammatory environment, the normal cells slowly and steadily develop into breast cancer cells.

Breast cancer has been known as a kind of high-risk tumors worldwide. Based on the data shown in 2018, breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality among females over the world [11]. Over the decades, the cancer cure rates have failed to show great improvement due to the obstacles of high aggressiveness and multi-drug resistance (MDR) [12]. Previous studies in the fields of breast cancer have placed a great priority on cancer cell gene mutation, proliferation, apoptosis, and protein activity changes than microenvironment changes, hence their therapeutic targets are limited and have little success in clinical application [13]. Interestingly, increasing evidence shows that chronic inflammation alters the microenvironment through multiple mechanisms, including cytokine production, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling, which are the likely explanations for the scourge of breast cancer. Chronic inflammation creates a pro-carcinogenic environment, of which the complex interplaying factors lead to the cancer formation and in turn enhance inflammatory conditions. Nowadays the term of “cancer-associated inflammation” receives great attention and is suggested as the typical seventh hallmark of tumor microenvironment [10]. Therefore, the whole picture of the inflammatory microenvironment establishes the knowledge of pathogenesis and therapy of breast cancer [14].

Inflammation and immunity

In most cases, the immunological functions of body can quickly track and clean harmful pathogens. Once an acute inflammation forms, the innate and specific immune systems are activated and then relieve the inflammation. However, the cancer-promoting inflammation may induce inappropriate immunity responses resulting in the condition of immunosuppression. It can be assumed that inflammatory microenvironment also contains immune components that support the immunosuppression and immune escape [15]. Inflammation-related mediators effectively stimulate and recruit immune cells to TME, which produce numerous interleukins and chemokines and activate transcription factors [16] to mediate signaling cascades that develop sophisticated molecular networks to control cancer progression. Inflammatory microenvironment not only raise the expression of immunosuppressive factors and immune checkpoint ligands, but also inhibit the anti-cancer activity of CD8+ T cells to hide from the immune surveillance [17]. Among them, the networks further aggravating the inflammatory responses may bring about major changes: the transformation of macrophages from M1 to M2; the transformation of neutrophil phenotypes from N1 to N2; transformation of T cells from Th1 to Th2 [18, 19]; the decreasing number and suppressive antigen-presenting performance of dendritic cells (DCs); the transform phenotypes of Tregs from negative to positive and deactivated anti-inflammatory activity of Tregs [20]. Immune cells with suppressive activity are able to regulate the immune system of body, which act an important role in facilitating cancer growth and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, and mediating inflammation for breast cancer development [21, 22]. The interaction between inflammation and immunosuppression suggests that cancer-promoting inflammation persistently establishes necessary microenvironment and greatly increases the risk of breast cancer propagation and recurrence.

The formation process and influences of inflammatory microenvironment

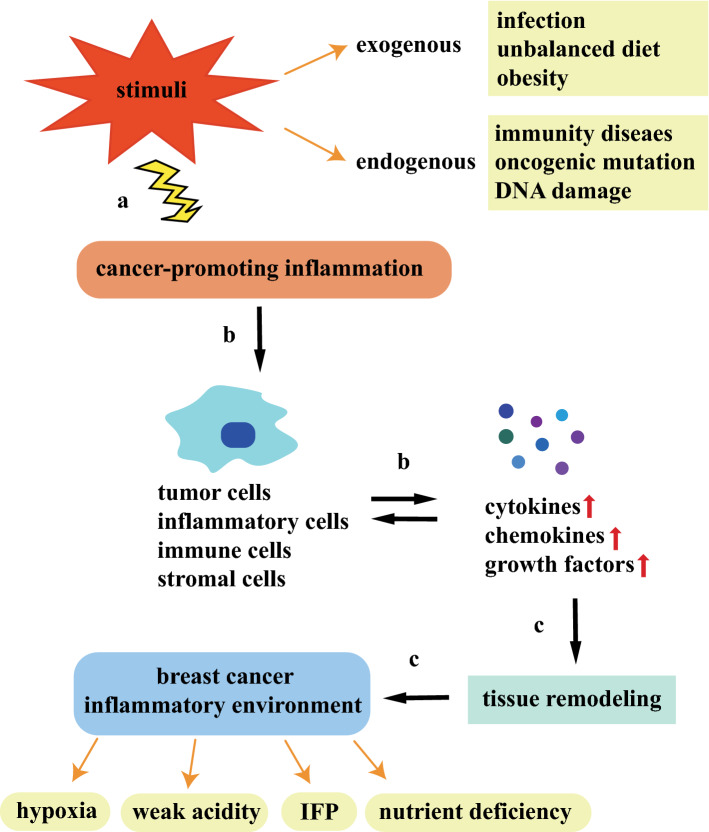

Current studies show that the exchange of information between cancer cells and inflammatory microenvironment turns out to be a virtuous circle of promotion. Inflammatory mediators in the TME recruit and activate various stromal cells, immune cells and inflammatory cells, which generate far more inflammatory signals to initiate related signaling pathways, thus inducing cancer cells to evade immune clearance. At the same time, the cells that reside in the TME release pro-proliferative signals and metabolites to reshape the tissues and create the inflammatory microenvironment. For the fact that normal blood vessels are unable to meet the material demand of unlimited multiplication of tumors, transcription factors induce high levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to reform a complex functional vascular networks. However, the new tumor vascular networks still cannot cover the entire region, which may occur from structural abnormalities and functional incompleteness. Thus, inflammatory microenvironment develops distinctive characteristics of hypoxia, nutrient deficiency, weak acidity, and high interstitial hydraulics (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

An outline of the endogenous and exogenous sources of cancer-promoting inflammation and the possible formation mechanisms of inflammatory microenvironment. a The endogenous and exogenous stimuli causing cancer-promoting inflammatory reactions are concluded as above; b cancer-promoting inflammation induces tumor cells, inflammatory cells, immune cells and stromal cells to secrete various cytokines, chemokines and growth factors. These cellular mediators, in turn, promote the recruitment and phenotypic alterations of immune cells; c inflammation remodel the tumor tissues and forms a favorable microenvironment for breast cancer cell survival

Due to the increased vascular permeability and the functional lymphatic system deficiency, the water inflow into the interstitial chamber can reach up to 15% of the plasma flow, forming the interstitial pressure (IFP). The levels of IFP are generally high at the tumor center and low at the tumor margin. IFP is not constant and fluctuates with the change of microvascular pressure because of tumor heterogeneity. The increased levels of tumor interstitial pressure will affect the anti-tumor functions of immune system and induce the large number of stimulating growth factors, cytokines and enzymes to regulate immune inflammatory responses and promote tumor angiogenesis. With limited survival material resources, tumor cells near blood vessels can absorb more energy than those in the distant tumor sites. Thus, radial concentration gradients of oxygen and nutrients are established in the inflammatory microenvironment. As the oxygen is gradually consumed, the cells far from the blood vessels are prone to be anoxemic necrosis. Actually hypoxia can affect the expression of maturation markers and chemokine receptors of dendritic cells, the replication of T cells, and the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The nutrient energy for rapid proliferation of tumor cells mainly depends on anaerobic glycolysis, which produce abundant lactic acid to reduce the pH level. At the same time, ATP hydrolysis, glutamine decomposition, carbon dioxide generation and bicarbonate consumption can also make the microenvironment slightly acidic. High level of lactic acid in the microenvironment are associated with immune escape [23], such as inhibiting NK cell division and reducing MDSC expansion. In addition, lactic acid also causes cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) to produce cytokines (e.g., IL-2, IL-6, TGF-β) so as to reduce the cell killing effects and promote inflammatory responses.

Major constituents of inflammatory microenvironment

In the continual process of cancer-associated inflammation, there exist considerable cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors in the TME. The cancer infiltrating cells are recruited and pro-inflammatory cytokines are released into the areas of breast cancer, greatly amplifying the inflammatory effects [24]. In this situation, different inflammatory cells are flexible in quantity and function under the stimulation of different chemical mediators, thereby exerting their biological influence on both cancer cells and TME [25]. Inflammatory cytokines are small molecular weight proteins that function in complex signaling and coordinated responses by autocrine, paracrine, or endocrine fashion [26]. Previous studies have investigated that a variety of cytokines such as IL-6, IFN-γ, Interleukin 1β (IL-1β), and TNF-α play an irreplaceable role during the process of inflammation and almost all of them build a communication bridge between TME, cancer cells, and immune cells [27]. Following are major elements of inflammatory cellular constituents and pro-inflammatory signals in the inflammatory microenvironment.

Cellular constituents

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)

In normal tissues, macrophages emerge as guardians to detect and respond to adverse stimuli. Functionally, macrophages engage in the nonspecific immune systems to kill the invaders and clear apoptotic cells. However, a large number of chemokines in the TME, such as CCL2 and CCL5, recruit monocytes to enter tumor tissues, which further derivate into TAMs [28]. In contrast to normal macrophages, TAMs, proved to be essential cells that reside in the TME, secrete various cytokines to mediate different aspects of immune and inflammatory responses [29]. There are two phenotypes of TAMs in the inflammatory microenvironment and the majority of them are M2 macrophages [30]. Obviously, the biological properties between them are almost completely opposite: classically activated M1 macrophages mediate acute inflammatory response, anti-infection, and antigen presentation; alternatively activated M2 macrophages suppress inflammation reactions, and induce tissue repair and angiogenesis.

The differentiation of TAM is determined not just by location but by cytokines. The intrinsic mechanisms of M2 phenotypic polarization require a series of key molecules, including IL-4, IL-13, IL-10, and M-CSF/CSF-1, which are mainly correlated to the NF-κB/STAT3 pathway [31]. NF-κB/STAT3 pathway is a crucial downstream signaling pathway of cytokines, especially in the regulation of IL-6-mediated inflammatory responses [32]. What is more, increasing evidence indicates that downregulation of LPS and TNF-α as well as activation of NF-κB tend to change cellular programs and phenotypes of TAMs toward M2 rather than M1. M2 macrophages can promote recruitment of Tregs and support evolution of cancer immune escape, since they can secrete cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β to impair T cell proliferation and killing ability [33]. Moreover, M2 macrophages also play an important role in the inflammatory microenvironment by upregulating VEGF, MMPs, and HIF1α [34]. These physiological changes help to drive an inflammatory and immunosuppressive TME, leading to poor clinical prognosis and decreased survival of patients.

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)

Fibroblasts in normal tissues (NFS) are spindle-shaped cells in rest state. Fibroblasts can handle wound-healing responses, damaged epithelial tissue regeneration, along with the ECM repair. Fibroblasts in the TME are reprogrammed into CAFs and activated their functions. It is reported that IL-1β, TGF-β, epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) play key roles in the recruitment and activation of fibroblasts [35]. CAFs are highly heterogeneous, derived from various types of cells, including pre-existing fibroblasts, stellate cells, epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [35].

As one of the most important stromal cells, CAFs secrete diverse cytokines and ECM components through autocrine or paracrine manner. The abundant activated infiltrating fibroblasts contribute to the promotion of cancer inflammation and fibrosis. A meta-analysis shows that the presence and function of activated CAFs in the TME are associated with poor survival in multiple solid tumors [36]. Hence, the mammary malignancy has long been believed to be as “wounds that never heal” for oncologist [37]. For one thing, CAFs activate HIF1α and NF-κB signals to promote epithelial–mesenchymal transformation (EMT) and boost the processes of oxidative stress, cell autophagy, and glycolysis [38]. For another, CAFs induce VEGF, IL-6, and CXCL1, which recruit immune cells into TME and inhibit innate and adaptive immune. CAFs closely interact with cancer cells and are widely involved in the processes of inflammation and immunosuppression in breast cancer microenvironment [39], to regulate microenvironment remodeling and cancer progression.

Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs)

Neutrophils are derived from hematopoietic stem cells of bone marrow and account for about 60–70% of white blood cells in circulation. Neutrophils can remain for 5 days or longer in circulation [40], and for several weeks in tissues. Neutrophils are usually the first line of defense at the site of infection or inflammation, responsible for the elimination of invading microorganisms, and are one of the markers of acute inflammation [41], but abnormal activation of neutrophils can lead to chronic inflammation and tissue damage. The ratio of neutrophils to lymphocytes (NLR) is an indicator of inflammation, and higher NLR is associated with poor prognosis and ineffective treatment [42]. NLR can also be used to distinguish primary breast cancer from benign proliferative breast cancer. Therefore, neutrophils are helpful in assisting cancer diagnosis and guiding treatment decisions.

Tumor cells and microenvironment recruit neutrophils to tumor sites by releasing signals, including chemokines such as CXCL8, CXCL5 and CXCL6, cytokines such as TNF-α, hydrogen peroxide and lipid mediators such as LTB4. Pro-inflammatory factors such as interferon-γ (INF-γ) in tumor microenvironment can prolong the survival time of neutrophils. Besides, neutrophils also secrete mediators to promote their own recruitment and persistence, and release various chemokines, such as CCL2 and CCL17 to recruit monocytes, macrophages, and Tregs to tumor sites.

TANs affect anti-tumor immunity depending on the different stages or types of tumors, demonstrating the complexity crosstalk of TANs in the TME. In 2009, Fridlender et al. classified the anti-tumor and pro-tumor neutrophils into N1 and N2 phenotypes, respectively [43]. The phenotype of neutrophils in the early stages of neoplasia is mainly N1. N1 neutrophils activate immunity and kill tumor cells by secreting cytokines and chemokines, such as IFN-I and IL-18. When exposed to regulatory molecules such as G-CSF or TGF-β, neutrophils are liable to convert to N2 phenotype. N2 neutrophils secrete ROS, arginase, peroxidase and other factors, which inhibit the functions of T cells and NK cells and suppress immunity systems to promote tumor progression. ANs can also promote the transformation of immune cells into pro-tumor phenotypes in the TME, including promoting macrophages differentiation into M2 macrophages by releasing TGF-β and OSM. The ROS released by TANs may lead to DNA mutations or damage, which means that TANs are essential for inflammation, immunosuppression, and cancer occurrence.

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)

MDSCs include a heterogeneous population of immature bone marrow cells, which can be divided into monocytic (M-MDSCs) and granulocytic (PMN-MDSCs). The phenotypes of the two subsets of MDSCs in humans are, respectively, labeled as CD11b+CD14+HLA-DR−/lowCD15− and CD11b+CD14−CD15+HLA−DRlow/− [44]. In tumors, granulocytes of MDSC (gMDSCs) and mature neutrophils have similar morphology and expression of cell surface markers, but the differences lie in the inhibitory ability of T lymphocytes [45]. In addition, HIF1α-mediated downregulation of p-STAT3 in tumor microenvironment leads to MDSC differentiation into M2 TAMs, while lacking HIF1α MDSCs would differentiate into DCs. The markers of MDSCs overlap with other cell populations, so it is necessary to combine phenotypes and immunosuppressive activities to identify MDSCs. According to a meta-analysis, the increased frequency of MDSCs is negatively correlated with overall survival (OS) and poor disease-free/relapse-free survival (DFS/RFS) [46]. Meanwhile, the expression level of MDSCs is also correlated with the clinical stages of breast cancer.

The recruitment of MDSCs from bone marrow to tumor is jointly controlled by different factors to continuously supply MDSCs to tumor. The main chemokines of M-MDSC recruitment in breast cancer are CCL2 and CCL5. PMN-MDSCs are mainly recruited by CXC chemokines, including CXCL1, CXCL5, CXCL6, CXCL8 and CXCL12. Abnormal accumulation of MDSCs in the TME promotes immunosuppression and immune evasion, which is conducive to tumor progression. MDSCs suppress adaptive immunity by inhibiting CD4+ and CD8+T cells, and activating Tregs. Meanwhile MDSCs suppress innate immunity by suppressing NK cytotoxicity through TGF-β1. The proliferation and differentiation of MDSCs are induced by a variety of pro-inflammatory mediators (e.g., COX2, IL-6, TNF-α) and growth factors (e.g., GM-CSF, G-CSF, VEGF) in the TME. MDSCs in vivo usually have a short lifespan of 1–2 days, but chronic inflammation is suggested to help extend half-life of MDSCs. The pro-inflammatory mediator HMGB1 can stimulate autophagy to inhibit MDSC apoptosis and promote MDSC proliferation. STAT3 and NF-κB upregulate the pro-inflammatory calcium-binding proteins S100A8 to increase the number of MDSCs and enhance inhibitory activities. MDSCs can also secrete S100A8/A9 to induce their own activities. MyD88-dependent NF-κB regulates the expression of inhibitory factors IL-10 and Arg1, as well as the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins to enhance the immunosuppressive activities of MDSCs.

T regulatory cells (Tregs)

Tregs are generally considered as a specialized subset of CD4+T cells and function in regulating the dynamic balance of the immune system and maintaining immune tolerance. The development, stability and inhibitory activities of Tregs in the TME are regulated by various mechanisms. Foxp3 is the key to stabilize the lineage and maintain the immunosuppressive abilities of Tregs. The deficiency of Foxp3 usually leads to multi-organ autoimmunity in mice or humans. Tregs with high expression of IL-2 receptor (IL-2R) depend on interleukin-2 (IL-2) to maintain the survival and functions of Tregs. IL-2 activates signal transducers and transcriptional activator 5 (STAT5) that directly regulates the expression of Foxp3 to program immunosuppressive Tregs. Disruption of this process will trigger the reprogramming of Tregs into pro-inflammatory ones, indicating that Tregs may adapt to the TME to differentiate and obtain pro-inflammatory activities. IL-6 is another important signal for Treg reprogramming during inflammation. While Tregs are activated by T cell receptor (TCR) in the presence of IL-6, Tregs will down-regulated Foxp3 and lose the inhibitory activity [20].

In the TME, Tregs regulate tumor immune escape by inhibit the activities of T cells and other immune cells. For examples, Tregs secrete TGF-β, IL-10 and IL-35 to inhibit DCs presenting antigens, resulting in inhibiting anti-tumor immunity. Tregs can inhibit the functions of classic NK cells through PD-1, IL-1R8 and IL-37. Factors produced by MDSCs and Tregs form a positive-feedback loop that expands the cell population and strengthens the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment. Tregs can also interfere with metabolic processes to destroy other cells, including the secretion of perforin, granzyme (Gzm), and cyclic adenosine phosphate (cAMP). The content of Tregs in breast tumor biopsy is positively correlated with invasive phenotype and recurrence [42]. Therefore, Treg infiltration may have a profound impact on the prognosis of breast cancer patients.

Non-cellular constituents

Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)

The NF-κB family consists of five subfamily members, including NF-κB1 (p105/p50), NF-κB2 (p100/p52), c-Rel, RelA (p65), and RelB. These subunits regulate the expression of NF-κB-dependent target genes by forming homo-dimers or hetero-dimers. During the resting state, NF-κB dimer in cytoplasm generally binds to its inhibitory protein IκB to inactivate NF-κB. NF-κB performs its physiological functions under precise control of the organism and is activated mainly by classical or alternative pathway. In classical pathway, IκB kinase (IKK) complex phosphorylates IκB, afterwards p65/RelA and p50 form dimer complex and translocate to the nucleus for regulating the expression of multiple target genes, which encode cytokines, adhesion molecules, and other active proteins [47].

NF-κB, an inducible transcription factor, can regulate the association between inflammation and TME by stimulating the expression of pro-inflammatory genes and modulating TCR signal transduction [48]. For example, NF-κB typically delivers activation and differentiation signals to T cells and helps activated CD4+ T cells differentiate into Th1, Th2, Th17, or Tfh under different circumstances, among which Th1 and Th17 cells are attributed to inflammatory T cells, acting an important role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases [49]. The primary effect of Th1 cells is to secrete IFN-γ so as to promote inflammation and immune abnormality when exposed to tumor sites [50]. Th17 cells are able to produce the inflammatory cytokine IL-17, which is a central cytokine in the defense of pathogens invasion by recruiting monocytes and neutrophils to inflammatory sites [51]. In addition, genetic studies have shown that aberrant NF-κB activation signal is always present within the surrounding inflammatory microenvironment [52]. In particular, the synthesis and release of inflammatory cytokines and NF-κB signaling pathway communicate closely with each other [53]. Given that, NF-κB acts as a multifunctional orchestrator in many signaling pathways responsible for inflammatory microenvironment regulation.

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)

Notably, the activation of STAT3 signaling cascade is also an important mechanism of mediating inflammatory microenvironment. STAT family involves six major members, among which STAT3 has an exact impact on various inflammation and immune diseases. STAT3, a primary pro-inflammatory transcription factor, directly or indirectly binds to specific DNA sequences to regulate genetic transcription. STAT3 normally locates in cytoplasm as an inactive monomer and is negatively regulated by several endogenous inhibitors, including cytokine signaling inhibitors (SOCS), cellular phosphatases (SHP1, SHP2, DUSP22, PTPRD, PTPRT, and PTPN1), and protein inhibitors (PIAS). When a cytokine or growth factor binds to its corresponding cell surface receptor, tyrosine kinases such as JAK can phosphorylate STAT3 with subsequent downstream signaling activation [54]. Meanwhile, STAT3 also can be phosphorylated directly by non-receptor tyrosine kinases such as Src or Bcr-Abl, and then homodimeric p-STAT3 transfers to the nucleus [55]. Mechanistically, inflammatory conditions rapidly activate STAT3 signal by pro-inflammatory mediators and STAT3-dependent feed-forward loops. STAT3 participates in relevant inflammatory responses and regulates the synthesis and release of inflammatory factors (e.g., TNF-α, INF-γ, IL-6) by binding to gene promoters, which are of vital importance in maintaining inflammatory environment and enhancing breast cancer progression [56].

Interleukin-6 (IL-6)

IL-6 mainly comes from cancer cells, TAMs, helper T cells (Th), MDSCs, and CAFs, and can induce multiple inflammatory signaling cascades linking with cells turning cancerous. Meanwhile, IL-6 is described as a dominant pro-inflammatory cytokine with pleiotropic biological effects and becomes a molecular indicator in the diagnosis of inflammation and breast malignancy due to its high serum concentrations. Research demonstrates that there are two types of IL-6 receptors: transmembrane IL-6 receptor (mIL-6R), soluble IL-6 receptor (SIL-6R) and their co-receptor gp130, which represent different receptor-binding mechanisms [57]. For example, a well-acknowledged function of IL-6 is the cooperation with NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway by mating with IL-6R and gp130 on the surface of the cell membranes [58]. But in trans-signaling way, IL-6, SIL-6R, and gp130 form the IL-6/SIL-6R/gp130 complex to convert extracellular signals into intracellular ones.

Indeed, IL-6 may affect immune systems to promote the maturation of DCs and other antigen presenting cells (APCs) and induce the multiplication and differentiation of B lymphocytes [59]. IL-6 also influences the levels of the macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) receptor signaling on monocytes, which are closely related to the initiation of macrophage differentiation and many inflammatory diseases [60, 61]. In addition to immunomodulation, IL-6 possesses dual functions in suppressing or amplifying inflammation by regulating its downstream signaling pathways including JAK/STAT3, MAPK, and PI3K/AKT. On the one hand, IL-6 activates STAT3 to achieve anti-inflammatory effects of reversing inflammation progression and promoting epithelial cell proliferation. On the contrary, IL-6 exhibits its pro-inflammatory properties by activating NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway in the inflammatory microenvironment. Further research confirms that IL-6 family is associated with breast cancer, lung cancer, gastric cancer, and liver cancer [62]. Kim et al. simulated the mutations in two genes including tumor suppressor gene p53 and phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN) and then revealed that the mutations in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) could upregulate IL-6 to induce NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway. However, the cancer cells were significantly reduced when treated with anti-IL-6R antibodies [63, 64]. Therefore, the pro-inflammatory positive feedback not only alters IL-6 expression but also reinforces inflammation-induced genomic instability associated with the occurrence of breast cancer, which indicated that IL-6 [65]. Not surprisingly, IL-6 is generally acknowledged to be a strong cancer promoter and has been implicated in inflammation regulation and cancer development.

Interleukin-8 (IL-8)

IL-8, also identified as the chemokine CXCL8, is secreted by large numbers of cells including epithelial cells, macrophages, fibroblasts, and cancer cells. IL-8 exerts its effects through cell-surface receptors and the human receptors are CXCR1/2 and ACKR1/DARC. IL-8 and CXCR1/2 are rarely expressed in normal tissues and may be promoted by inflammatory signals such as NF-κB, ROS, and steroids. The stimuli in the TME may also regulate IL-8 expression, including acidity, hypoxia, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. When encounter stimulus signals, increased IL-8 receptors meditate intercellular and intracellular communication by activating different signaling pathways.

IL-8 is one of the major inflammatory mediators and has similar functions to IL-6, but has a longer half-life. As the research moves along, IL-8 appears to become an important part of cancer-related activities. The functions of IL-8 cover promoting inflammatory cell activation, inflammatory mediator release, angiogenesis, and host immune functions, and involves in the infiltrating process of cells (e.g., lymphocytes, neutrophils) in cancer mass [66], thus IL-8 can respond to many biological actions such as inflammation and host defense against infections [67]. IL-8 regulates inflammation symptoms and tissue homeostasis by chemotactic activity on neutrophils, macrophages, and other types of cells after binding with special receptors. Overall, IL-8 triggers abnormal inflammatory and immune reactions, aiming to construct favorable circumstances for breast cancer progression and poor differentiation.

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)

TNF-α is a member of pro-inflammatory cytokines applied to the intercellular communication. TNF-α mainly comes from monocyte–macrophages, endothelial cells, and lymphocytes and TNF-α receptors involve TNF-α RI and TNF-α RII. TNF-α RI, ubiquitously expressed in most cells, induces pro-inflammatory responses and cell apoptosis. TNF-α RII locates in immune cells and acts as a sensor of environment to accelerate cell activation and proliferation. At the receptor-binding sites, TNF-α may activate four different signaling pathways dependent on the appropriate conditions to dynamically transmit chemical signals: pro-apoptotic pathway induced by the interaction of caspase-8 with Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD) [68]; anti-apoptotic pathway induced by the interaction between cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein-1 (cIAP-1) and TNF receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2) [69]; AP-1 signaling pathway induced by TRAF2 and JNK [70]; NF-κB pathway induced by receptor-interacting protein (RIP) [71].

TNF-α performs its role in the immune system regulation, virus replication inhibition, and inflammation responses. Definitely, dysregulation of TNF-α production might be related to many human diseases, including chronic inflammation, Alzheimer disease, especially breast cancer, leukemia cancer, colon cancer, and lymphoma cancer. It should be noted that exposure to high sustained levels of TNF-α strengthens the anti-tumor and anti-angiogenesis effects, which are related to the downregulation of MCE3 and angiotensin signaling pathway [72]. Instead, less concentrated TNF-α promotes in inflammation initiation, angiogenesis, and cancer growth.

MicroRNA (MiRNA)

As the name implies, non-coding RNA (ncRNA) does not prepare to be transcribed into mRNA or protein but to serves as a functional agent to regulate physiological and biochemical reactions by interacting with signaling molecules. MiRNA is one type of nearly 22–25 base pair-long ncRNA after alternatively splicing and possesses high conservatism of evolution under stringent spatiotemporal control, indicating its cell and tissue specificity. Well known for adjusting gene expression functions, miRNA takes advantage of every opportunity to desire translation inhibition or degradation of target mRNA and is considered to be the strongest regulator of inflammation [73]. Different miRNA on different situation can work as “mitomiR” or tumor suppressor miRNA, respectively, amplifying or attenuating inflammatory signals [74]. Although miRNA content in vivo accounts for less than 1% of total ncRNA, miRNA may be a potent biomarker to diagnose cancers and predict prognosis for the fact that uncontrolled miRNA expression and cancer progression appear to go hand in hand [75].

Researches show that NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway and miRNA are interrelated and work with each other to co-regulate biological reactivities in vivo. Result in breast cancer, the expression of miRNA changes significantly, of which miR-21 adds the largest amount by activated STAT3 [76]. miR-21 can target many different mRNAs of PDCD4, PTEN, HIF-1α, TIMP3, and TM1. and is closely associated with clinical stage, lymph node metastasis, and badly prognosis. Furthermore, STAT3 has an immediate impact on the expression of miR-146b and miR-204. Generally, miR-146b remains high concentration in normal breast epithelial cells but low in breast cancer cells. Therefore, in normal circumstances miR-146b would suppress NF-κB expression to down-regulate inflammatory cytokines, thereby inhibiting inflammatory responses and impeding cancer initiation. Conversely, activated STAT3 in breast cancer can reduce miR-146b expression to make NF-κB free from miR-146b control, namely the NF-κB/IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway going back to normal activation pattern and reinforcing inflammatory microenvironment [77]. Equally, IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway can downregulate miR-204 to inhibit the expression of IL-6R. It means that IL-6R/STAT3/miR-204/IL-6R feedback loop starts to present in the inflammatory microenvironment, thus reversely suppressing inflammation. Taken together, inflammation is dynamically controlled by the co-action of inflammatory cytokines, transcription factors, and miRNA.

Mode of action of inflammatory microenvironment on breast cancer

Since excessive levels of inflammatory mediators may raise the risks of poor prognosis and high mortality, without question, they are key factors to mediate the activation of molecular signaling pathways, such as NF-κB, STAT3, and other signals, which provide favorable conditions for inflammation and oncogenesis. The phenomenon of signal crosstalk in the inflammatory microenvironment may occur across and within various signaling pathways. The signaling pathways are reported to induce the expression of oncogenic genes and certain active proteins, ultimately contributing to rapid amplification of the pro-carcinogenic inflammation and accelerating all phases of carcinogenesis [78].

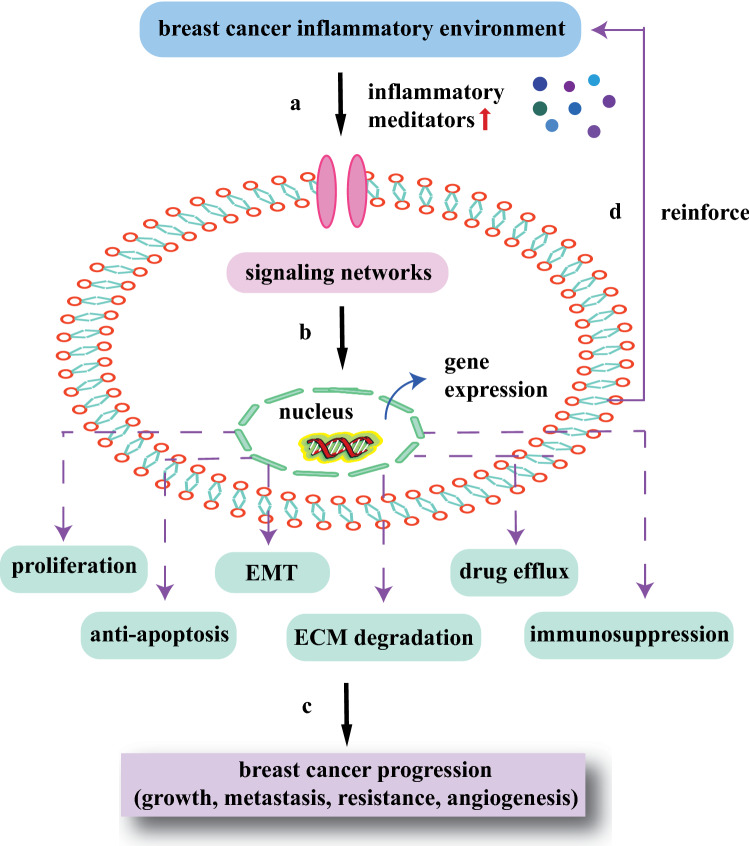

Studies have found that STAT3 and NF-κB are often co-activated in cancers and NF-κB-dependent IL-6 is thought to be the primary driving force of STAT3 activation. The abnormal activation of STAT3 in turn captures RelA in the nucleus causing constitutive activation of NF-κB. The complex crosstalk between NF-κB and STAT3 in the inflammatory microenvironment can collaboratively stimulate the transcription of specific target genes encoding HIF1α, Bcl-2, and MMP9. The adjustive functions of active proteins are typically downstream consequences of NF-κB/STAT3-induced inflammatory genes, which closely link with poor prognosis for breast cancer patients. So far, excessive expression and continuous phosphorylation of NF-κB/STAT3 signal have been observed in breast cancer inflammatory microenvironment. It is reasonable to assume that numerous factors come into play simultaneously in the association between chronic inflammation and breast cancer, whereas NF-κB and STAT3 are indispensable ones to induce and maintain the inflammatory microenvironment [79]. The idea that activated NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway could regulate in vivo biological reactivities of inflammation, immunity, cell proliferation, morphogenesis, and differentiation, suggests the significance of inflammatory microenvironment modulation in breast cancer. To figure out the relationship between inflammatory microenvironment and breast cancer, it requires a comprehensive analysis of mechanisms behind complicated signaling networks (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Interaction between inflammatory microenvironment and breast cancer development. a Inflammatory conditions induce cells to upregulate inflammatory meditators, which activate signaling transduction networks; b the transcription factors translocate to nucleus and interact with each to enhance relevant gene expression; c activated miRNAs and proteins promote the processes of breast cancer growth, metastasis, resistance, and angiogenesis, including cell proliferation, anti-apoptosis, EMT, ECM degradation, drug efflux and immunosuppression; and d the signaling transduction networks in turn reinforce inflammatory microenvironment for better cancer survival

Growth

Chronic inflammation can induce DNA damage and oncogenic mutation directly through cytokine signals or indirectly through reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen intermediates (RNI) to cause genetic changes or epigenetic modifications [80]. Inflammatory microenvironment ensure the provision for cell proliferation and anti-apoptosis, thus leading to breast cancer generation and development. It has been suggested that ROS and inflammation-related cytokines enhance the activity of NF-κB and STAT3, which are highly and simultaneously induced in inflammatory cells, immune cells, and cancer cells [80, 81]. The NF-κB-dependent inflammatory mediators and growth factors with a vital role in proliferation and survival of cancer cells, tend to boost expression of anti-apoptotic genes, namely cylin D1, caspase-8 inhibitor cFLIP, apoptosis inhibitors cIAPs and XIAP, and Bcl-2 apoptosis factor family [82]. In terms of the mechanisms, STAT3 has been established as a major cause of upregulated genes such as survivin, c-myc, cyclin D1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL, which not only promote breast cancer cell growth but also protect against apoptosis. Cai et al. have proved that TNF-α can upregulate the expression of oncoprotein hepatitis B X-interacting protein (HBXIP) to promote breast cancer growth through the positive-feedback loop of TNFR1/NF-κB (and/or p38)/p-STAT3/HBXIP/TNFR1. Thus, it becomes clear that the pro-inflammatory effects of TNF-α may increase the aberrant gene expression that develops high risk of breast cancer [83]. The researchers also found that cytokines showed some abilities to regulate cancer stem cell (CSC) replication, thus initiating cancer cell growth.

Meanwhile, the translation of immunosuppressive cells from immune cells also happens during the processes of chronic inflammation, breast cancer formation, blood vessel growth, and tissue reconstruction. The immunosuppressive cell recruitment and immunosuppressive factor expression require phosphorylation and activation of STAT3 by overactive protein kinases. Such immunosuppression mechanisms help breast cancer cells escape from the immune-mediated detection and elimination of the hosts. According to previous research, STAT3 seems to be a necessary condition for MDSCs to accumulate and apply immunosuppressive effects on the areas of cancers, which markedly promotes the breast cancer growth and development [84]. In addition, histone transmethylase 2 (SMYD2) also adds crosstalk between STAT3 and NF-κB to promote cancer cell proliferation and avoid apoptosis. NF-κB/STAT3 and other inflammatory signals in the TME also change effector T cells anti-tumor immunity and efficiently induce Treg expression. Collectively, inflammation and immune escape that mediate breast cancer growth are consequences of combined forces.

Metastasis

For the reasons of cancer-related death, migration and invasion should be on top of the list [85]. The spread procedure of breast cancer is to form an invasive lesion with local infiltration and next the cancer cells enter the blood circulation for transport to distant metastases, allowing them to settle down and proliferate again [86]. The metastatic processes are inclusive of primary breast cancer site remodeling and breast cancer cell adaptation to the secondary environment [87]. However, the invasive and metastatic capacities of cancer cells do not arise from the beginning. In the inflammatory microenvironment, the tumor matrix and other components can react to both internal and external variations and then secrete cytokines, protease, and receptors, which reflect the metastatic mechanisms including shifting tissue osmolality and nutrient metabolism, recruiting immune cells, exerting angiogenesis and immune inflammatory effects [88].

Studies show that TNBC cells activate IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway, which induces the expression of CCL5, HIF1α, and VEGF to accelerate metastasis. Patients with higher plasma IL-6 levels particularly tend to have advanced tumor accompanying distant metastasis [89, 90]. Experimentally, inside the inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) microenvironment, macrophages secrete a great many IL-8 resulting in neutrophil recruitment [91]. It is observed that one crucial aspect of elevated abilities of IBC motility and aggressiveness remains to be raising IL-8 expression to promote neutrophil recruitment. M2 macrophages have similar functions of activating NF-κB, STAT3, and HIF1α signaling pathways by secreting VEGF, platelet-derived factor (PDGF), and inflammatory cytokines to mediate inflammation and EMT [92]. The prominent emphasis of breast cancer metastasis is abnormal vessel formation [93]. Therefore, aggressive tumors highly link with vascularization courses. NF-κB engages in the processes of EMT, invasion, migration, and angiogenesis through upregulating the levels of SLUG, TWIST1, SNAIL, and MMP9 [94]. As it turns out, one of the most instructive inducers of metastasis is matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which not only mediate the ECM degradation, but also control breast cancer angiogenesis, and cell–matrix adhesion. STAT3 is also a major factor in tumor migration and invasion accompanying transcriptional expression of MMP2, MMP9, TWIST, and vimentin, which enables breast cancer cells to penetrate the basement membranes and spread from situ organ to distant by means of lymphatic and blood vessels, making further invasion and metastasis. For all these reasons, the inflammatory condition is destined to maintain the probabilities of metastasis and recurrence, causing deteriorated conditions or death.

Multi-drug resistance

Multi-drug resistance of breast cancer not merely resists to one certain anti-cancer drugs, but also develops cross-resistance with other drugs. It is universally acknowledged that the emergence of chemoresistance makes it hard to find out suitable plans for individual chemotherapy. Most of the MDR mechanism researches focus on breast cancer cells, such as targets alterations, drug active excretion by efflux pump proteins, and limited absorption, but ultimately end in failure. This is due to the fact that MDR development counts on both cytogenetic changes and TME transformation [95]. Due to the heterogeneity and variability, inflammatory microenvironment may enable physiological barriers to shield from the chemotherapy drugs, thus affecting drug efficacy and promoting MDR [96].

It is observed that many cells, cytokines, transcriptional factors, and extracellular matrix in the inflammatory microenvironment are closely correlated with MDR [97]. In this case, the human secreted crimp-associated protein 2 (SFRP2) secreted by CAFs promotes the expression of WNT16B protein, which activates the classic Wnt signaling pathway and leads to drug resistance [98]. CAFs also induce the NF-κB/STAT3 pathway to affect the chemotherapy sensitivity of breast cancer cells [99]. NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway particularly favors MDR by regulating gene expression at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. IL-6 and IL-8 expression are significantly increased in human breast cancer, and the neutralization antibody assay indicates that MDR depends on their activity [26]. IL-6 can activate NF-κB/STAT3, PI3K/AKT, and Ras-MAPK signals to promote MDR [100]. NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathway induces HIF1α expression in breast cancer, leading to less drug sensitivity and chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity. NF-κB occupies an important place in chemoresistance by enhancing transcription of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family and subsequent disturbance of apoptosis [101]. The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family are major MDR efflux transporters including P-glycoprotein (P-gp/ABCB1), multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2/ABCC2), and breast cancer-resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) [102]. P-gp/ABCB1 is associated with the constitutively activated NF-κB signals [101]. In hypoxic-treated TNBC, STAT3 promotes expression of ABC transporters, especially multidrug-resistance proteins ABCC2 and ABCC6. Moreover, study in TNBC treated with adriamycin (ADR) has also explored the close relationship between miRNA expression levels and chemoresistance, demonstrating that STAT3 mediates increased miR-181a expression and induces acquired resistance [103]. The truth that inflammatory microenvironment is defined as significant role in MDR offers an effective strategy to cure breast cancer because of its action to several targets.

Angiogenesis and proliferation

In the early stages, the tumor in a dormant state appears to be inhibited by lack of blood vessels [104]. Inflammation is closely related to angiogenesis. The factors in the inflammatory microenvironment stimulate the production of vascular endothelial cells, thus inducing a large number of irregular angiogenesis and proliferation. The newly formed blood vessel network is capable of delivering nutrients, chemical signals, and oxygen necessary for tumor proliferation, and helps tumor release from dormancy. Due to the imbalance and continuous expression of angiogenic factors and inhibitors, the structures and functions of tumor blood vessels are different from normal blood vessels. The characters are decreased neovascularization flow, immature vascular stratified network, poor pericyte coverage, destroyed endothelial cell connections, and increased vascular permeability. Hence, tumor vessels vary in size and density. These structural abnormalities maintain the pathological features of the inflammatory microenvironment such as hypoxia, high permeability, and high interstitial pressure. Angiogenesis is important for the progression of primary breast cancer. Tumor vascular leakage and hypoxic-induced cell necrosis promote the continuous recruitment of immune/inflammatory cells (including lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and mast cells) to the inflammatory microenvironment. These cells release inflammatory cytokines to activate signaling pathways to aggravate the inflammatory responses. Abnormal tumor vascular system not only affects the recruitment of inflammatory cells, but also affects the activation of CAFs, stromal cells and other cell types in the inflammatory microenvironment.

Malignant proliferative tumors exhibit a high degree of vascularization, which is mediated by a combination of signaling molecules, including VEGF, inflammatory factors, chemokines, HIF1α, and MMPs. VEGF is believed to be pivotal for new vessel growth by activating certain signaling pathways, including the NF-κB and MAPK pathways, which increase vascular permeability and inflammation. Increased serum VEGFA concentration of metastatic breast cancer patients is associated with decreased progression-free survival (PFS) and poor overall survival (OS) [105]. During tumor progression, tumor cells and surrounding cells express various MMPs that contribute to angiogenesis and ECM remodeling. In recent years, it has been realized that hypoxia condition in the inflammatory microenvironment activates HIF1α to control angiogenesis [106]. NF-κB combine with the promoter regions of HIF1α to directly regulate HIF1α expression, which induce angiogenesis factors including IL-6, IL-8, COX-2, macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM), vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM), original and urokinase fibrinolytic enzyme activator (UPA).

Another mechanism of tumor angiogenesis is inflammatory angiogenesis. Inflammatory factors such as IL-1 and IL-6 mediate multiple signaling pathways involved in inflammatory processes that promote endothelial cell migration and proliferation, thereby promoting tumor angiogenesis. It is suggested that high expression of VEGF and IL-6 family cytokines in HER2− breast cancer patients show significantly reduced survival rate [107]. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (INOS) in inflammatory cells activates nitric oxide (NO). NO not only expends vessels and increases permeability, but also stabilizes the transcription of HIF1α-induced angiogenic factors. In addition, miRNA interact with pro-inflammatory factors to control inflammation and angiogenesis, such as HIF1α-dependent miR-210. MiR-155 expressed in the ectopic breast cancer model can recruit inflammatory cells such as TAMs and enhance angiogenesis by targeting VHL 56. Thus, the inflammatory microenvironment plays an important role in maintaining tumor angiogenesis, altering phenotypes of tumors including cell proliferation, metabolic reprogramming, and immunosuppression.

The significance of inflammatory microenvironment in breast cancer treatment

During the past years, different modalities applied to cure malignant breast cancer involve surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. It seems that surgery is a useful option only in the early stages of cancers and radiation might do great harm to healthy tissues and organs [108]. Therefore, chemotherapy is still desired to be the most applicable approach, which provides potential of delivering drugs to tumor sites and controlling drug release. However, confined by cell selectivity and drug stability, therapeutic effects of conventional chemotherapy are usually far from satisfactory. Nowadays traditional methods have encountered dramatic challenges, so the demand for ideal anti-cancer drugs is becoming increasingly urgent.

With the development of nanotechnology, the NDDS has become one promising avenue for breast cancer-targeted therapy [7]. Nanoparticles have attracted great attention on account of their benefits, considered as promising carriers to treat devastating malignancy. For example, they can incorporate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs via special structures for drug combinations. In this context, nano-formulations are especially designed to produce the best possible outcomes and improve life quality for patients by increased targeted accumulation and reduced side effects. There exist numerous examples that have been succeed in translation to clinic, such as polymersomes, liposomes, dendrimers, and micelles. Given the subclinical and clinical studies, the focus of NDDS lies in the special decoration of nanoparticles, claiming that it not only ensures their precise targeted drug delivery to desired tumor sites, but also avoids the clearance by reticuloendothelial system (RES) and mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS) [109]. It is seen that nanomedicines have great advantages of bioavailability improvement, lower toxicities, and therapeutic efficacy enhancement in comparison to traditional chemotherapeutic drugs.

For the significance of inflammatory microenvironment, it is seen that effective breast cancer treatment requires to target not just cancer cells, but the connection between cells and inflammatory microenvironment. The treatment mechanism may be an inclusive of cancer cell inhibition and inflammatory microenvironment modulation. The constituents of inflammatory microenvironment except cancer cells may show a good genetic stability, so that therapeutic targets of inflammatory microenvironment may be applicable to different subtypes of breast cancer and the patients are less likely to acquire MDR, apparently having the advantage over traditional chemotherapy.

Nanochemotherapy suggests that nano-targeted drug therapy is useful for controlling abnormal cancer growth by interference with the message transduction and biological pathways. There are many inflammatory meditators in the inflammatory microenvironment, which indicates that suppressing the carcinogenic factors and signaling pathways can prevent breast cancer progression. Recently researchers have developed some therapeutic drugs and corresponding targets for selective cell killing effects and inflammatory microenvironment modulation (Table 1). Undoubtedly, the delivery of anti-cancer drugs with NDDS is bound to have appealing application value and provide guidance for breast cancer treatment. Accordingly, it is of utmost to discover new effective and safe chemical therapeutics which specifically target both TME and cancerous cells. To get a conceptual understanding, it is a critical step to figure out the mechanisms of action between nanomedicines and TME.

Table 1.

Summary of inflammation inhibitors and targeting group of inflammatory microenvironment for breast cancer therapy

| Type | Drug | Targeting group |

|---|---|---|

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | Aspirin; indomethacin; piroxicam; sulindac; ibuprofen | COX enzymes (COX1 and COX2) |

| Glucocorticoids (GCs) | Dexamethasone; prednisone, prednisone; betamethasone | Inflammatory cytokines |

| JAK inhibitors | SAR302503; AZD1480; WP1066 | JAK |

| TNF-α inhibitors | Etanercept; infliximab; adalimumab | TNF-α |

| IL-6 inhibitors | Siltuximab; sirukumab; Tocilizumab; ALX-0061 | IL-6; IL-6R |

| IL-1 inhibitors | Anakinra; canakinumab; rilonacept | IL-1 |

| NF-κB inhibitors | Bortezomib; PDTC; QNZ (EVP4593); caffeic acid phenethyl ester | NF-κB |

| STAT3 inhibitors | Bt354; osthole; arctigenin; Rhus coriaria; schisandrin B | STAT3 |

| CXCR1/2 antagonists | AZD5069; reparixin | CXCR1/2 |

| CSF-1R antagonists | CSF1 mAb; PLX3397; RG7155; BLZ945; CSF-1R ATP inhibitor | CSF-1R |

| CCR5R antagonists | Maraviroc; vicriviroc | CCR5R |

Passive nano-drug delivery system

The targeted drug delivery systems can be divided into “passive” and “active” targeted drug delivery systems. The enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect requires nanoparticles to change proper size and shape for tumorous site accumulation, leading to what we usually called passive targeted effect [110]. The passive targeted delivery strategy utilizes the physiological conditions specific to the TME for drug release. It is well known that tumor blood vessels alter the integrity of vessel walls and increase average pore sizes so that nanoparticles could easily penetrate into tumor parenchyma in contrast with normal ones [111]. Despite the passive targeted of nanoparticles contributes to longer circulation time to some extent, the opposite opinions insist that they have lots of limitations in uniform distribution [112]. One case is that the EPR-mediated method is restricted to the diameter less than 4.6 mm of tumors. In other cases, they only preferentially accumulate in extracellular stroma near leaky site of tumor vessels but fail to reach the deep inside tumors, resulting in uneven killing of tumor cells and intrinsic or acquired resistance.

To address those challenges, the design of targeted nanoparticles for fully distribution has regained great interest [113]. However, many approaches have been applied to enhance diffusion of cell targeted nanoparticles to the whole tumor region, but few have generated positive results in clinical therapeutic efficacy. Research has investigated that dense stromal tissues, abnormal angiogenesis, and high interstitial pressure help TME form an impermeable barrier to remove foreign substances. As matters stand, the design in targeted NDDS needs to resolve one issue: the way to overcome both microenvironment barriers and cellular barriers. In combination with cellular targets, microenvironment targets can pave the way for nanoparticles to be specifically internalized by cancer cells for exposure to drug treatment. Nanotechnology has exploited the features in the TME including pH, hypoxia, and glucose metabolism to apply to stimuli-responsive nanoparticle system for smart targeted drug delivery (Table 2). Stimuli-responsive nanoparticles are imposed by special stimuli, so that they can readily cross biological barriers and control drug release to bring about notable effects of drugs internalization and accumulation in tumors. In view of the foregoing contribution of inflammatory microenvironment to breast cancer progression, the nanochemotherapy hold promise in utilizing “hallmarks of cancer” of inflammatory microenvironment for better targeting [114].

Table 2.

Examples of passive NDDS for breast cancer therapy

| Mechanism | Nanocarrier | Material | Cell line/animal model | Drug | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH-responsive | Polymeric micelles | Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)-poly(d,l-lactide) (PEOz-PLA) | MCF-7/ADR, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-231 male BALB/c nude mice | Paclitaxel (PTX) and honokiol (HNK) | [109] |

| Solid-lipid nanoparticles | Adipic acid dihydrazide (HZ) | MCF-7, MCF-7/ADR, MCF-7/ADR | Doxorubicin (DOX) | [110] | |

| Micelles | 2,3-Dimethylmaleic anhydride-block-polyethylenimine-block- poly[(1,4-butanediol)-diacrylate-β-5- amino-1-pentanol](DMA-PEI-PDHA) | Mouse breast cancer cell lines 4T1, 4T1 Female BALB/C nude mice | PTX | [112] | |

| Hypoxia-responsive | Liposomes | Nitroimidazole derivative | Mouse prostate cancer cell lines (RM-1), human pharyngeal squamous carcinoma cell lines (FaDu), RM-1 C57BL/6 mice, patient-derived xenograft non-obese diabetic combined immune-deficient (NOD/SCID) mice model | DOX | [114] |

| Drug–drug conjugated nanoparticles | Azobenzene (AZO) | MCF-7, cancer stem cell (CSC), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) | Combretastatin A-4 (CA4), irinotecan (IR) and cyclopamine (CP) | [115] | |

| Biomimetic | Liposomes | Macrophage membrane | 4T1 cancer cells, murine RAW 264.7 macrophage cells, 4T1 cancer cells bearing mice | Emtansine | [122] |

| Poly(d,l-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NP | Inflammatory neutrophil-derived membrane | 4T1 cells, 4T1 female Balb/c nude mice | Carfilzomib | [124] |

PH-responsive nano-drug delivery system

As discussed in Warburg hypothesis, cancer cells survive in hypoxia and commendably adjust to the anaerobic glycolysis, producing lactic acid and maintaining the tumor tissues in slightly acidic condition (pH 6.5–6.9) [115], which has stimulate effects of cancer metastasis and resistance. The quantity of protons, ironically, increases with the changes of the microenvironment to ensure pH at physiological levels but ends up promoting acidic microenvironment formation [116]. It is an effective strategy to make utmost of acidic condition, namely pH-responsive nanoparticles can only be activated until they reach acidic microenvironment.

The pH-sensitive prodrugs with such biodegradable nanoparticles control drug release gradually with drug coating layer degradation in acidic microenvironment, but are too stable to deliver drugs in normal tissues, thus having minimal side effects and maximum therapeutic effects. Wang et al. constructed dual drug-loaded pH-sensitive polymeric micelles to promote tumor targeting and medication accumulation, which were triggered by low pH to suppress MDR and metastasis of breast cancer [117]. Zheng et al. synthesized RGD-DOX-SLNs and exploited breast cancer models in vivo and in vitro to evaluate the inhibitory effects of RGD-DOX-SLNs on growth and drug resistance. The RGD tripeptide-conjugated, pH-sensitive solid-lipid nanoparticles loaded with DOX will steadily decompose in slight pH microenvironment and reach the maximum drug concentration in tumor sites for 1–72 h after administration. The research investigated that RGD-DOX-SLNs can improve drug release efficiency, cellular uptake, and cytotoxicity of drugs to improve breast cancer therapy, thereby reducing the DOX-induced cardiotoxicity and nephrotoxicity [118]. In addition, mechanistic studies demonstrated that positively charged nanoparticles can be drawn to cell membranes through electrostatic adsorption, so the way to keep nanoparticle surface charge negative in normal tissues while reversing positive in tumor tissues will enhanced internalization and biodistribution in tumors [119]. Based on this mechanism, Tang et al. developed a dual pH-sensitive PTX-loaded micelles (DPM) with the charge switchable function in the slightly acidic environment of breast cancer, which resulted in higher cellular uptake, cytotoxicity, and intra-tumor accumulation of PTX [120]. It will be seen that pH-dependent NDDS offers effective treatment strategies and approaches for targeting breast cancer microenvironment.

Hypoxia-responsive nano-drug delivery system

As far as is known, growth efficiency of tumor cells is built on the basis of high metabolic expenditure, which leads to lack of blood supply and oxygen-deficient environment. Throughout this process, hypoxic microenvironment overextends oxygen and increases levels of free radicals and ROS to interfere DNA repair mechanism and drive genomic damage. Hypoxic condition also induces tyrosine kinase-mediated signal transduction pathways to cause cancer angiogenesis, metastasis, and drug resistance. Moreover, hypoxia activates key enzymes of glycolysis for more energy demand and pushes the local site transformation into less-acidic environment, hence acidity and hypoxia conditions complement each other and make indispensable contribution to cancer progression [121]. It is demonstrated that the partial pressure of oxygen is as low as 0 mm Hg in solid tumors, but it reaches nearly 30 mm Hg in normal tissues. Inspired by this, hypoxia as a striking feature catches the attention of targeted drug delivery and the hope for effective therapeutic approach has turned toward hypoxia-responsive nano-drug delivery system.

As the term suggests, hypoxia-responsive nanoparticles stay inactive in normal tissues while they convert into active metabolites in hypoxia TME. These nanoparticles equipped with variable properties and structures under hypoxic condition can alter the drug release rates, reduce side effects, and improve uneven tissue distribution, which bring great benefits to the majority of cancer patients. They come up with a proof that hypoxia-induced reductive reactions of the nitroimidazole derivative triggers liposome decomposition and facilitates drug release, so that DOX-HR-LPs are able to avoid non-specific internalization by normal cells. The cell line-derived and patient-derived xenograft models have showed that DOX-HR-LPs possess high sensitivity to hypoxia and would obtain better selectivity for hypoxic tumor cells, thus significantly improving anti-cancer efficacy and reducing DOX toxicity [122]. Zhang et al. reported that hypoxia-responsive drug conjugated NPs with azobenzene (AZO) linker can simultaneously restrain the growth and invasion of differentiated cancer cells, CSCs, and the “vascular niche” in breast cancer hypoxic microenvironment. Once arriving at tumor sites, the AZO linker responds to hypoxia condition and changes its construction, afterwards the disassembled NPs selectively accumulate and release the drugs into tumor sites for better permeability and cellular uptake. Given all this, hypoxia-responsive nanoparticles could flexibly change shape, size, surface charge, and function to avoid cytotoxicity in healthy tissues [123].

Biomimetic nano-drug delivery system

For the past few years, the discovery of biomimetic carriers underlying drug delivery improvement has been introduced to cancer intervention, including exosomes, or cell membranes of erythrocytes, leukocyte, platelets, and stem cells. The experimental results show that biomimetic carriers give full play to the superiority of targeting particular destinations, since they cover noteworthy features of high specificity, immune escape, and physiological barrier penetration [124]. More importantly, the nanoparticles coated with membrane components can preserve the nanoparticle characterizations while conferring surface properties from various origins of cells, such as long circulation time, biodegradability, and adhesive membrane proteins to several targets [125]. Exosomes are membrane vesicles secreted by different cells that contain an abundance of proteins and nucleic acids to provide channels for information delivery system [126]. For that reason, exosomes are usually useful for transportation of proteins, mRNA, and ncRNA. Membranes of erythrocytes and leukocytes are also desirable candidates for biomimetic carriers. Erythrocytes, unquestionably, the largest group of cells in human blood, can be employed in NDDS to increase drug absorption and target macrophages, which extend the residence time of drug-loaded nanoparticles and improve pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of chemotherapy [127]. In addition to increased biocompatibility and circulation time, leukocytes (including monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes) have the capabilities to pass blood–brain barrier (BBB) and centralize at the inflammatory TME so that they favor TME modulation and tumor necrosis [128]. In this regard, the biomimetic nanomaterials with great flexibility over normal nanomaterials can decide different cell-derived membranes and nanomaterials according to complex disease patterns. Here, some examples for biomimetic nano-drug delivery system will be enumerated.

As presented in previous studies, with the properties of inflammation tendency and low immunogenicity, macrophages can be isolated and utilize the membranes to construct macrophage-modified nanoparticles. The specific conjugation of chemokines and chemokine receptors located on the macrophage membranes enables macrophage-modified nanoparticles to recruit to tumor sites, which improves drug transport efficiency, selective cellular uptake, and intracellular drug release [129]. Cao et al. attempted to design a biomimetic strategy to endow emtansine liposome with macrophage membrane (MEL) for treating lung metastasis of breast cancer. It could be mentioned that α4 integrin on the surface of macrophages grants MEL the specific targeting ability of combination with vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) on the surface of cancer cells. As a result, macrophage-decorated emtansine liposome will hardly enter the normal tissues and can prolong blood circulation, increase tumor infiltration, and induce cell apoptosis [130]. Kang and his team decorated the surface of poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles by inflammatory neutrophil-derived membranes to synthesis neutrophil-mimicking nanoparticles (NM-NPs). Evidence shows that the intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) is widely expressed on the surface of metastatic breast cancer cells and mediates the cell-specific adherence between neutrophils and endotheliums by chemotactic influences [131]. It could be inferred that the high bio-binding activity of neutrophils mainly attributes to intrinsic cell adhesion molecules on membranes. In comparison with undecorated NPs, NM-NPs can target and eliminate metastatic cells, thus effectively preventing metastasis in the early and advanced phases [132].

In brief, according to the unique characteristics of the inflammatory TME, natural biological membranes are developed to be prospective carriers loaded with drugs, which start with the advantages of biocompatibility, organize penetration, targeting, and safety [133, 134].

Active nano-drug delivery system

Breast cancer is a clinically heterogeneous type of disorders and can be classified into different subtypes largely dependent on specific circumstances, making it difficult to regulate standard targeted therapies [135]. It cannot be denied that the key to cure breast cancer is personally choosing therapeutic regimens based on the situations of patients. As is mentioned above, nanoparticles passively target and accumulate in the TME and the next step is to realize the endocytic process of drugs uptake into cells. To address the dilemma, the most practicable approach is to find out desirable targets for breast cancer patients and modify drug-carrying nanoparticles with each individual tumor biomarker. When ligand-functionalized nanomedicines bind to corresponding receptors, they will stimulate the receptor-mediated internalization of the external substances into cells, which have great impacts on specifically destroying cancer cells [136]. Therefore, cell-targeted drug delivery system aims to conjugate nanomedicines to one or more therapeutic targets, including antibodies, ligands, and peptides for the sake of interacting with receptors or proteins overexpressed on cancer cells [137] (Table 3). Considering these factors, active targeting is expected to further facilitate enough drug accumulation by the ligand–receptor interactions and has superior performance in the near future. The commonly used kinds of active targeted receptors for breast cancer cells are listed below.

Table 3.

Examples of active NDDS for breast cancer therapy

| Targeted receptors | Targeting group | Nanocarrier | Cell line/animal model | Drug | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HER2 | Trastuzumab (TmAb) | Polymeric nanoparticles | MDA-MB-231-H2N breast cancer tumor-bearing mouse model | PTX and everolimus (EVER) | [131] |

| Gold nanoparticles | SK-BR-3, MDA-MB-361, MDA-MB-361 female CD1-athymic mice | N/A | [133] | ||

| CD44 | HA | Hyaluronic acid-polyarginine nanoparticles | Human lung (A549) and breast (MDA-MB-231) cancer cell lines | Pentamidine | [136] |

| FR | FA | Liposomes | Mouse breast cancer cells (4T1) and mouse origin fibroblast cells (NIH3T3), 4T1 Balb/c mice | DOX | [138] |

| Silver nanoparticles | MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-231 female athymic nude mice | Berberine | [139] | ||

| Integrin | RGD | Lipid/calcium/phosphate (LCP) asymmetric lipid layer nanoparticles | MCF-7, MCF-7 female athymic nude mice, MCF-7 male Sprague–Dawley rats | PTX and gemcitabine monophosphate (GMP) | [142] |

| Generation 5 (G5) poly(amidoamine) dendrimers | U87MG cell line | DOX | [143] | ||

| EGFR | Peptide GE11 (YHWYGYTPQNVI) | Polymersomes | TNBC cell line(MDA-MB-468/231) | DOX | [148] |

Human epidermal factor receptor 2 (HER2)

HER2 is a transmembrane glycoprotein belonging to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family, which plays an important role in the processes of cell division, proliferation, and apoptosis. As a matter of fact, only a small amount of HER2 can be detected in normal tissues, while gene amplification and overexpression of HER2 are found in 20–30% diagnosed breast cancer [138], which lead to abnormally cellular proliferation and differentiation in tumor sites. Thus, it is thought that HER2 excessive expression appears to closely correlate with initiation, progression, and prognosis of malignancies.

Houdaihed et al. designed the HER2 and EGFR dual-targeted PTX + EVER-loaded NPs (dual NPs) that proved to enhance penetration in tumor tissues and reduce systematic toxicities [139]. Overall, the performance of dual-ligand nanoparticles is better than mono-targeted nanoparticles, which evaluates to be an interesting design at the forefront of anti-cancer therapies. Previous studies indicate that the considerable attraction between antibody and antigen makes HER2 to serve as a potential target for cancer treatment. Currently monoclonal antibody or antibody fragment are widely utilized because their light relative molecular weight cannot elicit strong immune reactions and there are many cases to translate basic and translational advances into clinical practice. Trastuzumab, a humanized anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody, can be used to modify the surface of the nanoparticles for specific drug delivery to HER2 overexpressed breast cancer cells [140]. Cai et al. modified gold nanoparticles (AuNP) with trastuzumab (trastuzumab-AuNP-111In), which were found to specifically bind to HER2-positive breast cancer cells. Trastuzumab-AuNP-111In turned out to be more efficiently internalized than AuNP-111In, improving tumor cytotoxicity and inhibitory growth effects [141]. Therefore, monoclonal antibodies are likely to be more durable and safety than small molecule ligands. Taken together, development of therapeutic HER2 methods still remains challenges for us.

CD44