Abstract

Andes hantavirus (ANDV) is an etiologic agent of hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS), a severe disease characterized by fever, headache, and gastrointestinal symptoms that may progress to hypotension, pulmonary failure, and cardiac shock that results in a 25 to 40% case-fatality rate. Currently, there is no specific treatment or vaccine; however, several studies have shown that the generation of neutralizing antibody (Ab) responses strongly correlates with survival from HCPS in humans. In this study, we screened 27 ANDV convalescent HCPS patient sera for their capacity to bind and neutralize ANDV in vitro. One patient who showed high neutralizing titer was selected to isolate ANDV–glycoprotein (GP) Abs. ANDV-GP–specific memory B cells were single cell sorted, and recombinant immunoglobulin G antibodies were cloned and produced. Two monoclonal Abs (mAbs), JL16 and MIB22, potently recognized ANDV-GPs and neutralized ANDV. We examined the post-exposure efficacy of these two mAbs as a monotherapy or in combination therapy in a Syrian hamster model of ANDV-induced HCPS, and both mAbs protected 100% of animals from a lethal challenge dose. These data suggest that monotherapy with mAb JL16 or MIB22, or a cocktail of both, could be an effective post-exposure treatment for patients infected with ANDV-induced HCPS.

INTRODUCTION

Andes hantavirus (ANDV) is the primary etiological agent of hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS) in South America with up to 40% case-fatality rate. ANDV is transmitted to humans via aerosolization of excrement from the rodent vector, Oligoryzomys longicaudatus (1, 2). In contrast to other hantaviruses, ANDV is the only hantavirus to be associated with human-to-human transmission (3). Currently, there is no U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved therapeutic or vaccine to treat or prevent ANDV infections. ANDV represents a significant public health threat, particularly in South America where several countries annually report a high relative incidence of hantavirus-induced HCPS (4–6). Because of their capacity to spread via aerosol, their manipulation requires a biosafety level 3 (BSL3) and BSL4 laboratories.

Hantaviruses are negative-sense RNA viruses belonging to the order Bunyavirales, family Hantaviridae (7). These viruses contain a tri-segmented genome, which encodes for nucleocapsid protein (N), two viral glycoproteins (GPs) (Gn and Gc), and the viral RNA polymerase (RdRp) (2). Virion assembly may occur primarily on internal membranes; however, it has been suggested that New World hantaviruses such as ANDV may assemble and mature at the plasma membrane (8). The natural hosts for these viruses are small mammals (e.g., mice, moles, voles, and bats); however, transmission to humans most commonly occurs via rodent-to-human transmission (2, 9). In rodent reservoirs, infection persists despite neutralizing host immune responses against the virus (10). Infection in rodents is predominantly asymptomatic, whereas in humans infection causes severe pathology.

In humans, HCPS involves fever, headache, and gastrointestinal symptoms anywhere from 7 to 14 days after aerosol exposure to the virus (11). This is followed by a 2- to 7-day period characterized by hypotension, pulmonary edema/failure, cardiac shock, and death in a significant number of patients (12). Currently, no specific treatment has been shown to be effective for HCPS; however, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation has been used in intensive care unit, improving outcomes (13). Although no curative treatment exists, studies in humans have examined the potential of methylprednisolone (14) and ribavirin (15) to treat HCPS; however, no beneficial effect on disease severity, viral load, or mortality was observed (14, 15).

Despite these setbacks, the potential for a treatment is promising, because there are several lines of evidence indicating that neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) can inhibit HCPS in vivo. In small animal models, specific DNA vaccines and passive transfusion of polyclonal serum from rabbit, duck, and human protected animals from HCPS (16–18). In HCPS patients, abundant hantavirus-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) early in disease is a predictor for survival (19). High titers of hantavirus-specific IgG have been observed in convalescent patients (20), and higher nAb titers are associated with milder disease outcomes (21), both suggesting a strong correlation between hantavirus-specific IgG titers and disease outcome. Furthermore, convalescent immune plasma from HCPS survivors passively infused into acute HCPS patients reduces fatality rates (22). These data suggest an important and practical role for Abs in controlling hantavirus infection in vivo.

Here, we set out to exploit the potential for nAbs to be used as therapeutic agents to treat hantavirus-induced HCPS. Toward this aim, we recruited 27 ANDV convalescent HCPS survivors from several outbreaks that occurred in southern Chile and quantified their serum capacity to bind and neutralize ANDV pseudovirions; several hantavirus-specific memory B cell clones were isolated and used to produce IgG using recombinant DNA technology. Two monoclonal Ab (mAb) candidates, JL16 and MIB22, were selected on the basis of their ability to bind and neutralize ANDV in vitro, and we examined their capacity to protect against a lethal ANDV challenge in the Syrian hamster model of ANDV-induced HCPS.

RESULTS

Selection of nAb donors from HCPS survivors

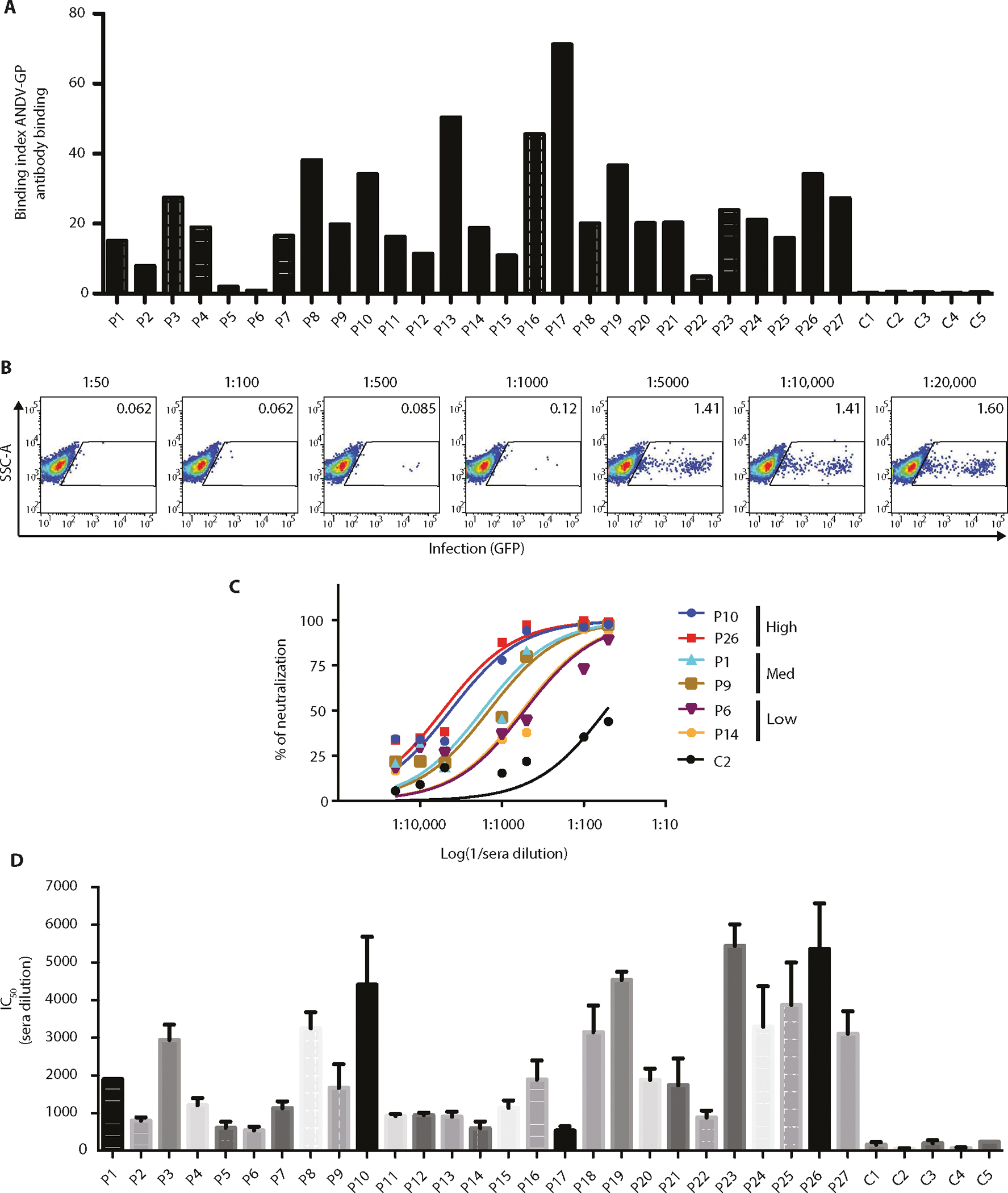

To determine whether sera from survivors retain circulating Abs against ANDV-GP, we developed a cell-based assay to quantify ANDV-GP–specific IgG binding. 293T cells were transfected with an ANDV-GP construct to express the GP on their surface. These ANDV-GP-293T cells were then incubated with sera from each of 27 ANDV convalescent or 5 healthy donors (negative control), and binding was determined by flow cytometry using a fluorescent secondary anti-human IgG Ab. To obtain a more accurate measurement of ANDV-GP–specific Ab binding, we used an Ab binding index measurement (23), which is a cumulative measure of the frequency (%) and density of antigen binding [mean fluorescence intensity (MFI)] (Fig. 1A). We observed no specific binding to ANDV-GP using healthy donor sera (C1 to C5) while observing a range of IgG-mediated binding to ANDV-GP using the ANDV convalescent sera (Fig. 1A). We observed between 2.4- and 116-fold of IgG binding above the negative control with a mean binding index of 23.33 ± 3.002 for convalescent sera versus a mean binding index of 0.3936 ± 0.04565 for healthy control sera (P = 0.0029). Subjects with a binding index greater than 70-fold of the negative controls and 3-fold above the mean binding index for patient sera were designated as high binders (P8, P10, P13, P16, P17, P19, and P26).

Fig. 1. Screening of sera reactive to ANDV-GP for mAb donor identification.

Binding and neutralization assays were performed with 27 ANDV convalescent sera. (A) Binding index analysis of ANDV-GP IgG sera using a cell-based assay. 293T cells expressing ANDV-GP were incubated with a 1:1000 dilution of sera from ANDV convalescent or healthy subjects followed by detection of total IgG by flow cytometry analysis (n = 1). (B) Representative ANDV pv neutralization assay is shown, and ANDV-GP pvs were incubated with sera from ANDV convalescent subject at different dilutions (1:50 to 1:20,000) and used to infect HEK293-IB3 cells. Upon productive infection, pseudoparticles produce GFP (n = 4). (C) Representative neutralization curves of ANDV convalescent sera with high, medium, and low neutralization activities and a healthy control (C2). The y axis displays the percent pseudovirus neutralization, and the x axis displays the reciprocal of the dilution (log) (n = 4; representative experiment is shown). (D) IC50 for 27 ANDV convalescent subjects and 5 healthy controls (n = 4). The y axis displays the reciprocal of the concentration. Error bars represent the SD of the mean. P1 to P27, ANDV convalescent subjects; C1 to C5, healthy control subjects.

Next, we examined the ANDV neutralization activity of the serum samples. To accomplish this, we used a BSL2 neutralization assay, in which ANDV-GP pseudotyped virus (pv) particles were used to infect target cells expressing the putative receptor β3 integrin (HEK293-IB3 cells) (fig. S1A) and assess IgG-mediated neutralization (24, 25). To facilitate the rapid readout of infection, cells produce green fluorescent protein (GFP) upon productive infection (fig. S1A). Because the GP mediates ANDV attachment and entry, it represents the major target of effective nAb responses. For the neutralization assays, virus particles pseudotyped with ANDV-GP (ANDV pv) were incubated with subject serum samples that were serially diluted from 1:50 to 1:20,000. Representative dot plots are shown (Fig. 1B). As a nonspecific control for serum inhibition, vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) pvs were also used to infect target cells in the presence of convalescent sera at the same dilutions as above. We observed no inhibition of VSV-G pv infections in the presence of any concentration of all subject sera tested (fig. S1B). To compare the efficiency of neutralization between sera, the 50% infection inhibition concentrations (IC50) were calculated by using HEK293-IB3 cells infected in the absence of any Abs as 100% infection. Convalescent sera displayed a wide range of neutralization activity, with 3.6- to 36.8-fold IC50 above negative control sera (fig. S1C).

To stratify neutralization data, we grouped serum samples into low (<5-fold), medium (5- to 25-fold), and high (>25-fold) neutralization activity (Fig. 1C). Most convalescent subjects (n = 18) displayed moderate neutralization activity, with four patients exhibiting low neutralization activity (Fig. 1D). However, five subjects displayed very potent IgG-mediated neutralizing activity, which were selected as the top neutralizers (P10, P19, P23, P25, and P26). These results indicate serological memory against ANDV-GP, even up to 14 years after infection, and are consistent with published reports showing the presence of nAbs in ANDV survival patients, with widely varying titers (19, 26).

Isolation of ANDV-GP–specific memory B cells and cloning of mAbs

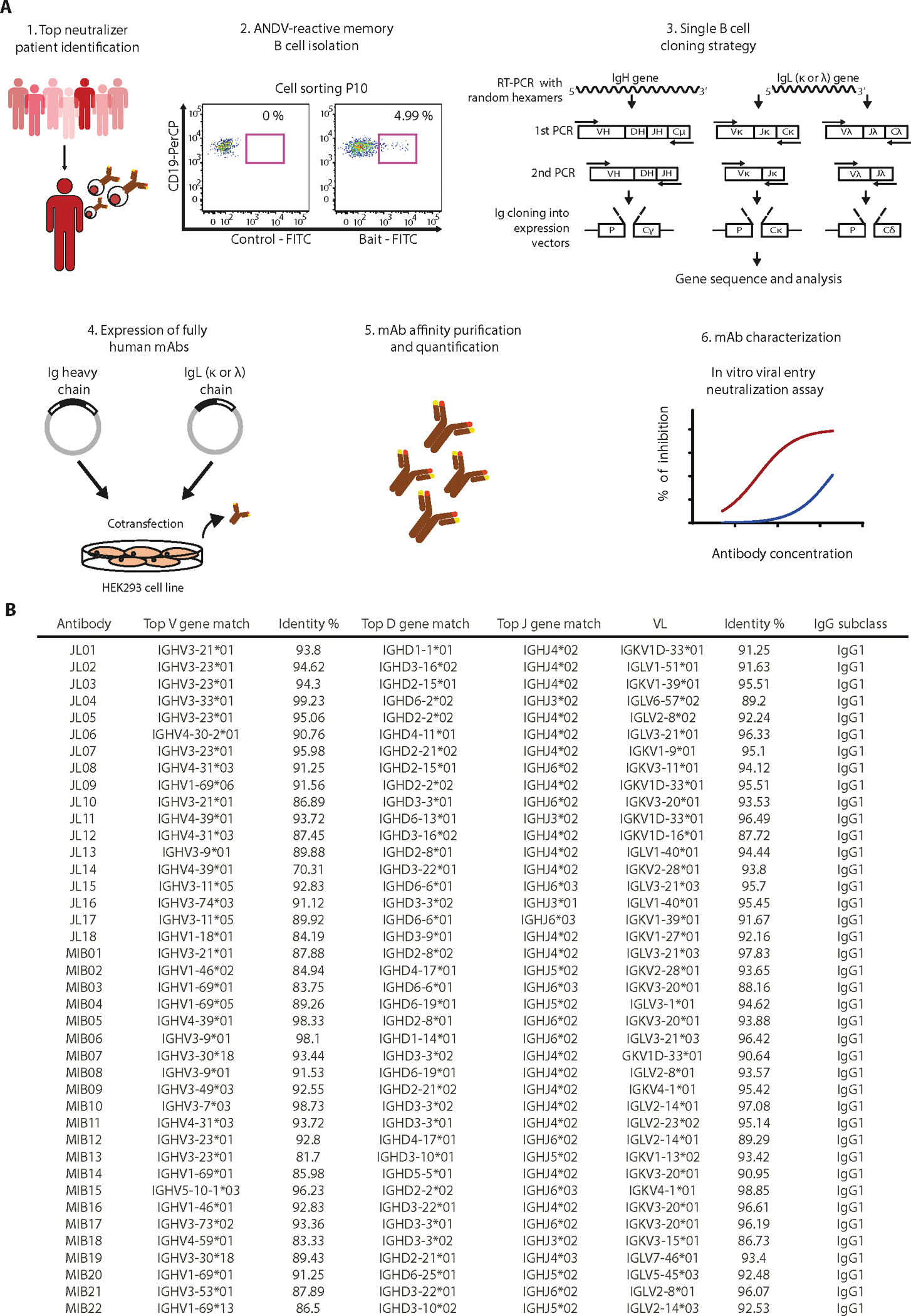

Several groups have demonstrated that isolation of pathogen-specific B cell clones from the blood of patients who display potent pathogen-specific binding and neutralization is an efficient method for generating nAbs against infectious diseases (27). Among our cohort, P10 displayed a high binding index, which was 87-fold above the negative control background (Fig. 1A), and a high neutralization capacity that was 30-fold higher than the negative control (Fig. 1D). Therefore, PBMCs from this patient were used to isolate ANDV-GP binding memory B cells, amplify IgG variable regions, and screen recombinant IgG for binding and neutralization activity against ANDV (Fig. 2A). Briefly, total cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were incubated with a cocktail of Abs including anti-CD19, anti-CD27, and anti-IgM and a fluorescent ANDV-GP bait scaffold (fig. S2). Then, we sorted CD19+/CD27+/IgM−/bait+ cells using a standardized protocol (28, 29). The binding specificity for ANDV-GP was confirmed using a nonrelated fluorescent envelope as control bait (Fig. 2A and fig. S2).

Fig. 2. Experimental flow chart for identification and isolation of human mAbs against ANDV-GP.

(A) PBMCs isolated from one HCPS convalescent subject (P10) were used for sorting of ANDV-specific memory cells, and IGVH and IGVL were cloned in an IgG1 backbone vector. Selected mAb clones were recombinantly produced and purified, followed by characterization of binding and in vitro neutralization. FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate. (B) List of IgG variable gene sequences analyzed using I-Blast and IMGT database shows the information for each Ab heavy and light variable chain.

The frequency of memory B cells expressing IgG reactive to ANDV-GP (bait) was 4.99% for cells from P10 (Fig. 2A). A total of 400 ANDV-GP IgG+ cells were single cell sorted, and complementary DNA (cDNA) was generated by two-step reverse transcription using random primers. The variable heavy and light chain domains were then amplified by nested polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and the resulting products were purified and sequenced (Fig. 2A) (29, 30). Only Abs with recovery of both heavy and light chains were analyzed further.

Sequencing analysis of 40 light and heavy Ig chain paired Abs revealed sequence heterogeneity across the cloned IgGs, with 70 to 99% germline identity for heavy chains and 86 to 98% germline identity for light chains (Fig. 2B). Analyzing the IGHV gene usage, IGHV1–69 and IGHV3–23 were the most frequent. With respect to light chains, IGK1 and IGL2 usage was more represented. Analysis showed that the Abs were not clonally related.

Using specific adaptors, we cloned the variable IgG (IgGV) region in frame with a backbone vector containing the human IgG1 constant (IgGC) region. The vectors were used to transfect 293T cells to produce full-length Ig. Two mAb clones, JL16 and MIB22, highly bound to ANDV-GP and were selected for further characterization.

Sequence analysis revealed that JL16 Ab displayed 91.12% of germline identity for heavy chain and 95.45% of germline identity for light chain. The JL16 IgG heavy chain was identified as belonging to the IGHV3–74 family, with a closest V gene match to HV3–74*03, a closest D gene match to HD3–3*02, and a J gene match closest to J3*01. The JL16 IgG light chain was identified as belonging to the IGV1–40, with a V gene match closest to LV1–40*01 and a closest J gene match to LJ2*01 (Fig. 2B).

Conversely, MIB22 Ab displayed 86.5% of germline identity for heavy chain and 92.53% of germline identity for light chain. The MIB22 IgG heavy chain was identified as belonging to the IGVH1–69 family, with a top V gene match of HV1–69*13, a top D gene match of HD3–10*02, and a top J gene match of J5*02. The MIB22 IgG light chain was identified as belonging to the IGV2–14, with a top V gene match of LV2–14*03 and a top J gene match of LJ1*01 (Fig. 2B).

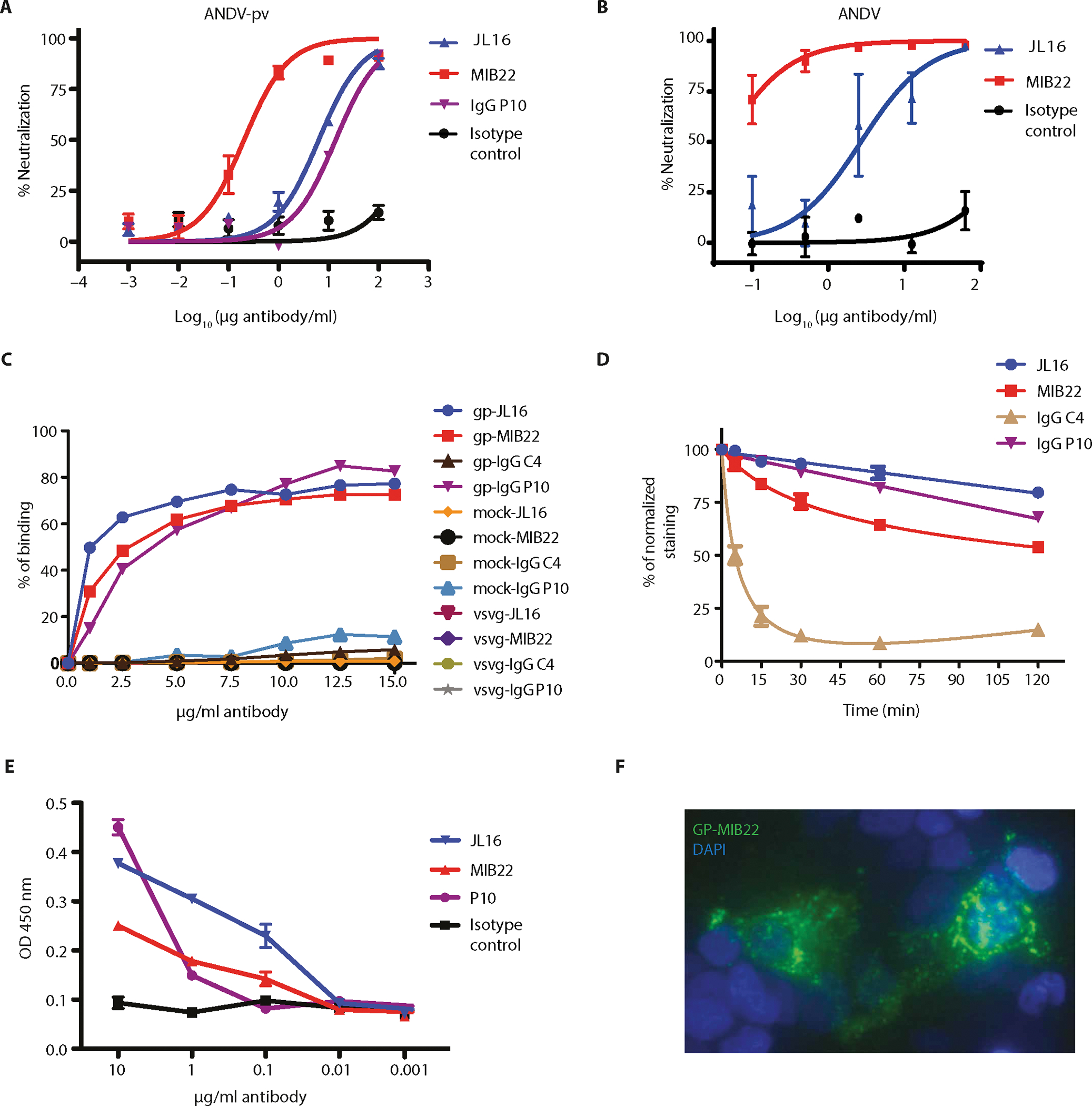

In vitro characterization of JL16 and MIB22 human mAbs

Next, JL16 and MIB22 were examined for their ability to neutralize ANDV. ANDV pvs were preincubated with different dilutions of purified IgG (0.001 to 100 μg/ml). As a positive control, polyclonal IgG from P10 was used, and isotype monoclonal IgG was used as a negative control. The MIB22 Ab had 32-fold higher neutralization capacity, as compared to JL16 Ab, with an IC50 of 0.205 versus 6.60 μg/ml, respectively (Fig. 3A). In the ANDV pv neutralization assay, mAb MIB22 displayed a 67-fold higher neutralization capacity, as compared to polyclonal IgG from P10, the patient from which MIB22 and JL16 were isolated. To test the ability of these two mAbs to neutralize live ANDV, we performed a focus reduction neutralization test (FRNT80). The MIB22 and JL16 showed FRNT80 of 0.14 versus 15.35 μg/ml, respectively, where the isotype control showed no protection (Fig. 3B). Together, these data strongly suggest that MIB22 and JL16 block viral entry and neutralize infectivity.

Fig. 3. In vitro characterization of human mAbs.

(A) Neutralization assay. HEK293-IB3 cells infected with a standardized amount of ANDV-GP pv in the presence of a 10-fold dilution titration curve of purified polyclonal IgG (P10), mAb MIB22, mAb JL16, or isotype control. The percent neutralization as a measure of IgG concentrations is shown (n = 2). (B) FRNT using live ANDV (Chile-9717869). Vero E6 cells were incubated with ANDV in the presence of mAbs MIB22, mAb JL16, or isotype control (0.1 to 62.5 μg/ml), and after 7 days, viral antigen was visualized by immunoperoxidase assay. The percent neutralization as a measure of Ab concentrations is shown (n = 3). (C) Binding assay. ANDV-GP-293T cells, mock-transfected 293T cells, and VSV-G–transfected 293T cells were incubated with purified IgG (1 to 15 μg/ml) from P10, a healthy donor (C4), or mAb JL16 or MIB22. Samples were analyzed by flow cytometry (n = 2 to 3; representative experiment is shown). (D) mAb off-rate determination. ANDV-GP-293T cells were incubated with purified polyclonal IgG (15 μg/ml) from a control donor (C4), ANDV convalescent patient (P10), or mAb JL16 or MIB22 at 4°C; after the indicated times at 37°C, surface levels were detected using an Alexa Fluor 488 anti-human IgG Ab and flow cytometry. The percent of normalized staining with respect to time = 0 is shown (n = 3). (E) ELISA using ANDV-GP pv as the coating antigen and purified polyclonal IgG (P10) (0.001 to 10 μg/ml), isotype control Ab, or mAbs JL16 and MIB22 (n = 3). OD, optical density. (F) Confocal imaging. Surface staining of ANDV-GP-293T cells that were incubated with MIB22 mAb at 1 μg/ml followed by staining with an anti-human IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) nuclear staining dye was used, and cells were visualized using confocal microscopy (n = 4; representative experiment is shown). Error bars represent the SD of the mean.

Because both JL16 and MIB22 displayed higher neutralization activity than the sera from which it was isolated, we compared the amount of Ab binding of these two mAbs versus P10 polyclonal IgG. 293T cells were transfected with an ANDV-GP or a VSV-G expression construct as a nonspecific viral envelope control. Mock-transfected cells were also used as negative control cells. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were incubated with different concentrations (1 to 15 μg/ml) of JL16 or MIB22 or polyclonal IgG from P10 or an ANDV naïve donor (C4; negative control), and Ab binding was measured by flow cytometry. We observed that P10 polyclonal IgG, JL16, and MIB22 bound to cells expressing ANDV at all Ab concentrations used. In contrast, IgG isolated from the ANDV naïve donor did not bind to cells transfected with ANDV-GP or the control transfected cells (fig. S3A and Fig. 3C). The 50% binding to ANDV-GP–expressing cells was at log 0.2878 for JL16 (1.94 μg/ml), 0.5292 for MIB22 (3.38 μg/ml), and 0.5456 for P10 IgG (3.51 μg/ml). At Ab concentrations of 10 μg/ml or higher, we observe similar binding of all ANDV-specific Abs (Fig. 3C). No Ab binding to VSV-G or mock-transfected cells was observed, demonstrating that binding was ANDV-GP dependent.

Next, we wanted to examine the relative affinity of these mAbs in comparison to P10 polyclonal IgG. For this, we measured the dissociation rate of each Ab using a flow cytometry–based method (31). In this experiment, 293T cells expressing ANDV-GP were first incubated with a saturating amount of IgG and then incubated at 37°C for various time periods (fig. S3B). Surprisingly, JL16 dissociated at much slower rate than both MIB22 and P10 polyclonal IgG. The proportion of bound JL16 after 120 min of incubation was 80% of saturating levels, representing a significantly higher proportion (P = 0.001), as compared to MIB22 and P10 IgG, which displayed 54% and 68% of saturating levels, respectively (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the proportion of background binding with negative control IgG showed little change over time. Together, these results suggest that JL16 has a higher relative affinity than MIB22.

Then, we examined the potential for combination therapy evaluating antagonistic binding to ANDV-GP. Using mAbs conjugated with quantum dots (Qdots), we performed a competitive binding assay on ANDV-GP-293T cells. The results showed that the JL16–Qdot-800 signal increased in a concentration-dependent manner, independent on the presence of saturating concentration of MIB22–Qdot-655. Similarly, MIB22–Qdot-655 signal increased despite the presence of JL16–Qdot-800 at saturating concentrations. Thus, each Ab bound to ANDV-GP despite the presence of the other (fig. S4), suggesting that they recognize different regions of ANDV-GP and therefore could be used as combination immunotherapy.

We next examined the ability of JL16 and MIB22 to detect ANDV pv particles by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). We incubated ANDV pv with various concentrations of JL16, MIB22, P10 polyclonal IgG, or an isotype control IgG (10 to 0.001 μg/ml). In line with the cell-based binding and relative Ab affinity results, JL16 displayed higher levels of ANDV particle detection at lower Ab concentrations, with a 2.8-fold higher level of Ab binding at 0.1 μg/ml, as compared to P10 polyclonal IgG, and a 1.6-fold difference as compared to MIB22. The isotype negative control did not bind (Fig. 3E). To confirm the specific binding to ANDV-GP expressed on the cell surface, we examined ANDV-GP by confocal microscopy. We observed specific surface staining (Fig. 3F), demonstrating that the Ab could be used not only for flow cytometry but also in imaging assays.

In vivo protective efficacy of JL16 and MIB22 human mAbs against lethal ANDV challenge

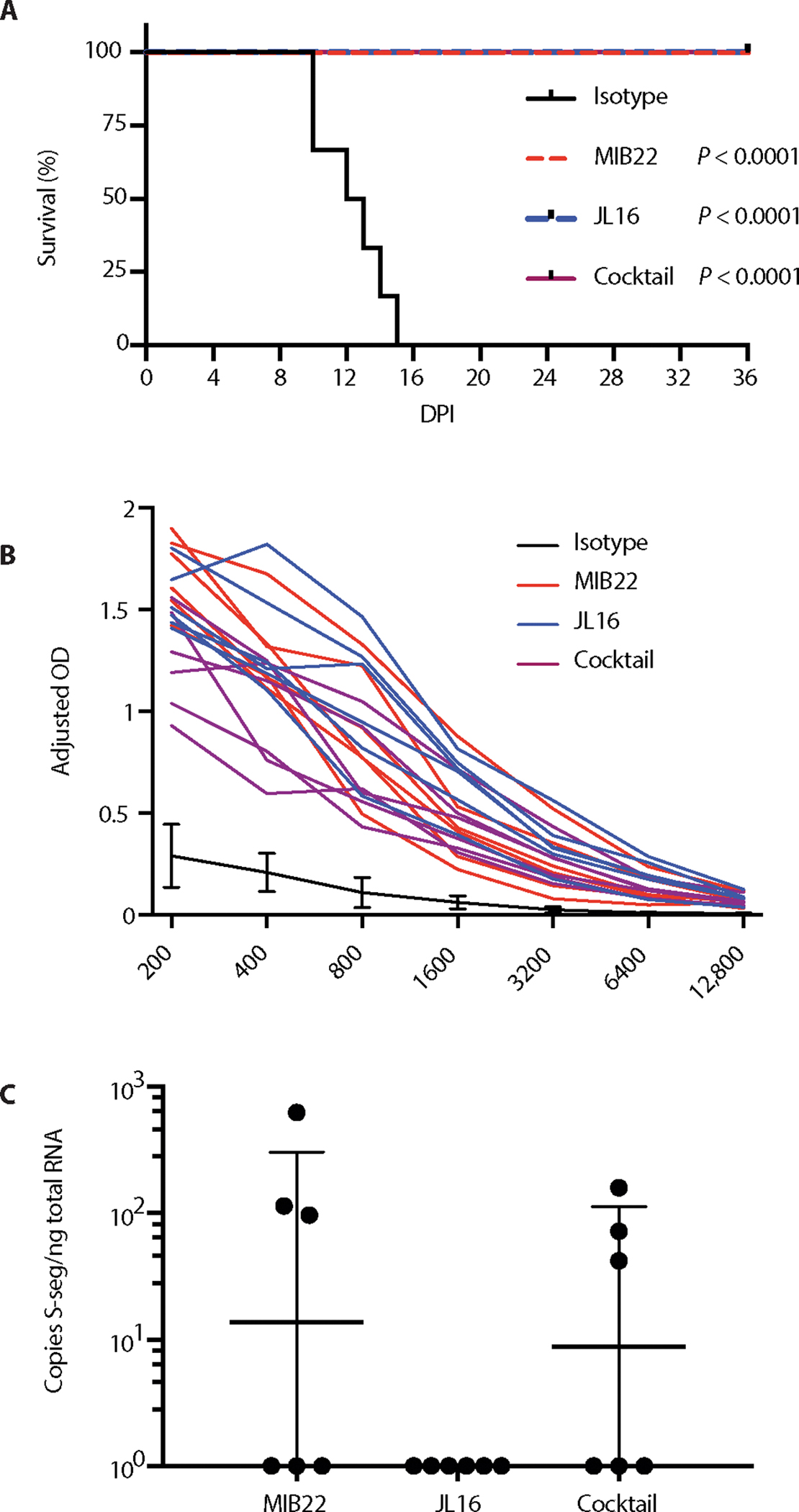

The potent in vitro neutralization capacity, coupled with mAb recognition of cell- and virus particle–associated forms of ANDV-GPs, suggests that JL16 and MIB22 might mediate in vivo protection from ANDV-induced mortality. To test the post-exposure efficacy of JL16 and MIB22 in vivo, we used the Syrian hamster model of ANDV disease. Upon productive infection, this model recapitulates many of the hallmarks of human ANDV–induced HCPS, including lethargy and pulmonary edema, and is nearly uniformly lethal (32–34).

Four groups of six hamsters were challenged with 200 focus-forming units (FFUs) of ANDV and treated with either isotype control IgG (50 mg/kg), JL16 (50 mg/kg), MIB22 (50 mg/kg), or a combination of the two (25 mg/kg each) at 3 and 8 days post-infection (DPI) (Fig. 4A). All the hamsters given the control IgG succumbed to ANDV infection within 15 days after challenge (range, 10 to 15 days). No overt signs of disease were observed in any of the treatment groups.

Fig. 4. Passive transfer of mAb protects against ANDV infection.

Twenty-four hamsters were inoculated intranasally with 200 FFUs of ANDV. (A) Groups of six hamsters were then administered MIB22, JL16, cocktail, or isotype control (50 mg/kg) intraperitoneally at days 3 and 8 after inoculation. Hamsters were monitored for disease. Survival was statistically evaluated using log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests (P < 0.0001). (B) ANDV-N ELISA from sera collected from surviving hamsters on 36 DPI for evidence of ANDV infection (n = 18). (C) Animals that survived to 36 DPI were euthanized, and ANDV-specific S-segment RNA was quantified using qRT-PCR in the lung tissue (n = 18).

At 36 days after challenge, all surviving animals were considered to be convalescent and euthanized. To confirm infection, we performed an ANDV N-specific ELISA, and all euthanized animals had serum anti-N titers ≥12,800 (Fig. 4B). We next assessed the levels of residual ANDV in the lungs of the convalescent animals by quantifying the S-segment RNA using sensitive quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). Low copy numbers of S-segment ANDV RNA were detected in three of six hamsters in each group that received either MIB22 or was given the cocktail therapy. The animals treated with JL16 showed no detectable ANDV RNA (Fig. 4C). The results of this experiment demonstrated that both MIB22 and JL16 are able to protect against lethal ANDV challenge, with JL16 treatment being potentially superior over MIB22 treatment.

DISCUSSION

Although HCPS cases reported annually are scarce, the number of cases is steadily on the rise, with the highest increases in South America. During 2017, the number of reported HCPS cases in Chile alone rose 76% above the previous year, representing a 63% rise over the 5-year trailing median (35). These increases are causing concern among many South American countries, because case-fatality rates remain high and no vaccine or specific treatment is available. Thus, any large outbreaks could simultaneously threaten public health and cripple several key economic drivers, such as agriculture, forestry, and tourism (36).

Recent clinical trial in humans has shown the potential of using convalescent plasma infusions to decrease mortality of HCPS (22). This supports the concept that neutralizing Abs generated from ANDV convalescent patients could serve as an effective treatment for HCPS. Therefore, we screened a cohort of hantavirus convalescent patient sera, to identify patients with high ANDV-GP recognition and potent neutralization activity, to develop an effective mAb-based treatment for HCPS.

Although the characterization of HCPS Ab responses has focused on anti-N Abs as valuable diagnostic tools (21, 37), anti-GP responses have been significantly associated with survival in HCPS patients (19, 22). The hantavirus GP represents the viral antigen expressed on the surface of viral particles, thereby representing the dominant target for neutralizing Ab responses. Here, we examined the capacity of convalescent patient Abs to recognize a cell surface–expressed form of the ANDV-GP. This assay quantifies the Abs that bind exposed epitopes on the native quaternary ANDV-GP structure, which likely represent the Abs that recognize free virus in vivo. Similar techniques have been previously used to characterize the functionality of anti-HIV Abs (23, 38). Therefore, here, we isolated and selected two mAbs, which showed simultaneously having high binding and neutralizing activity against ANDV.

Examining the in vitro neutralization activity, we observed that both JL16 and MIB22 neutralized ANDV pv more potently than P10 IgG, which indicates that our system is able to isolate mAbs with high affinity for native antigens. Moreover, the results obtained from the FRNT assay using live ANDV are in line with those obtained from the pv neutralization assay, which indicates the suitability of this assay as a tool for a rapid Ab screening.

Limitations of this study such as epitope mapping and therapeutic window of mAbs were not addressed. In addition, issues in producing soluble recombinant ANDV-GP prevented the obtaining of accurate affinity measurements for mAbs. To overcome that, in a cell-based assay (33), we observed that JL16 had a higher degree of ANDV-GP recognition and relative affinity, compared to both MIB22 and P10 IgG. These data demonstrate that although JL16 has a lower in vitro neutralization capacity, as compared to MIB22, it still has a higher affinity for ANDV-GP binding.

Because our results suggest that both mAbs bind different regions of the GP, we could potentially use them together in a therapeutic cocktail, because one of the limitations of single mAb therapy is the emergence of Ab escape variant and breakthrough (39). The use of two or more mAbs that recognize different epitopes should reduce the chances of escape mutant variants.

Using a well-characterized model of ANDV infection (17, 32, 40), we observed that JL16 and MIB22 yielded 100% protection from a lethal challenge with ANDV. Previous studies in this model demonstrated that at 3 days after challenge, productive infection is already established (40, 41). When we examined the euthanized animals for evidence of infection, all animals had seroconverted, confirming that infection was established before mAb administration. This suggests that inhibition of HCPS-induced mortality by JL16 and MIB22 was not attributable to neutralization of the initial inoculum alone. Most likely, protection is a result of neutralizing progeny virus and inhibiting infection of naïve cells. We also examined viral copy number in the lungs of euthanized animals, the major site of viral replication and disease pathogenesis (40). We observed that 50% of MIB22- and cocktail-treated group had low levels of detectable viral RNA, which is not surprising because viral RNAs have previously been shown to persist in tissue for several weeks after infectious virus is undetectable (42). However, we observed no detectable viral RNA in JL16-treated group, suggesting that JL16 was able to completely clear virus and viral RNA within this compartment despite having lower neutralization activity in vitro. Other antiviral mechanisms mediated by Abs could be in place, such as Ab-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity or complement-mediated virolysis (27).

Various attempts have been made to examine the potential of antiviral drugs to inhibit hantavirus infection, which include ribavirin and corticosteroids (14, 15). Unfortunately, these studies have failed to show any therapeutic efficacy. However, Hooper and colleagues (39) have recently demonstrated that polyclonal sera obtained from transgenic bovines DNA vaccinated against ANDV and SNV were able to partially protect hamsters from HCPS. Although promising as a potential vaccine, several barriers exist in using this type of polyclonal IgG product as a therapeutic agent, such as the risk of pathogen contamination from the source animals, the high costs associated with manufacturing and production, and the potential for batch-to-batch variability (27). Another disadvantage associated with polyclonal Ab products is that the vast majority of their Abs are non-neutralizing (27). In contrast, human recombinant Abs isolated from subjects who have survived infection have the advantage of being effective and naturally optimized (43). Moreo ver, the advances in recombinant Ab technology and mAb production have improved yield and reduced cost, and new methods of mAb manufacturing have benefits such as purity, safety, and cost.

Ab therapy is a promising solution for New World hantavirus infections, as antivirals have not shown efficacy so far. Vaccines are unlikely to be broadly used because of the low case numbers and the difficulty associated with vaccinating the at-risk population and the huge cost. Certainly, Ab therapy not only could improve patient outcome but also has the potential to play an important role in prophylaxis for persons at high risk of infection (44).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The study was conducted to identify, isolate, and characterize human mAbs specific against ANDV-GP, with the potential to neutralize ANDV infection and prevent HCPS. Twenty-seven ANDV survival subjects were recruited, and serum ANDV-GP–specific binding and neutralization were assessed, allowing the identification of high binding and neutralizing subjects. ANDV-GP–specific memory B cells from one of these subjects were isolated by cell sorting, and paired IGHV/IGLV was cloned into a human IgG1 and sequenced. mAbs were expressed and characterized in vitro. Last, mAb efficacies were evaluated in the Syrian hamster model of lethal HCPS. Primary data are located in table S1.

Human subjects

Human samples were collected after signed informed consent in accordance with approval of Institutional Review Board protocols (Ministry of Health, Valdivia Health Service, protocol number 456). Convalescent subjects corresponded to patients surviving a previous episode of HCPS (Hospitals from Valdivia and Puerto Montt cities) (n = 27), greater than 1 year after diagnostic confirmed by the Chilean Institute of Public Health (Instituto de Salud Publica). Healthy controls were subjects with no history of HCPS. Samples were processed as previously described (45).

Ethical statement

All work with ANDV-infected hamsters and potentially infectious animal material was conducted in the BSL4 facility at Rocky Mountain Laboratories (RML), Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH). Sample removal from high containment after inactivation was performed according to standard operating protocols approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee. All animal experiments were approved by the RML Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number 2017–053-E).

Pseudovirus particle generation

Viral particles pseudotyped with ANDV-GP (Chile-9717869) (ANDV pv) or VSV-G (VSV-G pv) envelope were prepared by transfecting 293T cells with the respective envelope construct, the transfer vector pHR SIN CSGW, and the packing vector psPAX2 with the calcium phosphate transfection method (46). Sixteen hours after transfection, the medium was replaced with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% cosmic calf serum (CCS), L-glutamine, and antibiotics. Collection of the ANDV pseudovirion containing suspensions was made at 72 hours after transfection. The suspensions were filtered through a 0.45-μm filter, seeded on a 20% sucrose cushion, and ultracentrifuged at 145,000g. Last, the pseudovirion pellet was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and normalized using an HIV core p24 ELISA (Sino Biological). Aliquots were stored at −80°C for later use.

Identification and isolation of ANDV-GP–specific human B cells

PBMCs were isolated by Ficoll density gradient separation (Histopaque, Sigma-Aldrich) and stored in liquid nitrogen. To isolate antigen-specific B cells from the samples with ANDV-GP binding and high neutralization activity, PBMCs were rested overnight and ANDV-specific memory B cells were labeled using anti-CD19–peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)–Vio700, anti-CD27–phycoerythrin (PE), and anti-IgM–allophycocyanin (APC) (Miltenyi Biotec) anti-human Abs and a fluorescent bait for ANDV-GP and isolated by cell sorting (BD FACSAria II) into single-cell wells.

Human mAb cloning, expression, and sequence analysis

Human Ab clones were generated by amplifying Ig genes from individually sorted B cells. Briefly, RNA from single cells was reverse transcribed, and the cDNA was used to amplify IgH, Igλ, or Igκ transcripts by two rounds of PCR (29, 30). All PCR products were purified, sequenced, and analyzed by IgBLAST/IMGT-V-Quest against the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information, NIH) and the IMGT (The International Immunogenetics Information System) human variable gene databanks. Once analyzed, gene-specific primers containing restriction enzyme sites were used to amplify IgH, Igk, and Igl genes for cloning. Digested IgH, Igκ, and Igλ PCR products were purified and directly cloned into pFUSEss-CHIg or pFUSEss-CLIg expression vectors (InvivoGen). These expression constructs enable the expression of full-length human constant regions from IgG1, Igk, or Igλ. Briefly, PCR products were flanked with different restriction sites and ligated using a T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) before transformation into Escherichia coli (DH5α) (Invitrogen). To verify the insertion, colony PCR and sequencing were performed. The positive clones were validated through sequencing and compared to the original PCR sequences. Other molecular features of the heavy and light variable genes such as junctional diversity and length, as well as somatic hypermutation rates and complementarity-determining regions, were determined.

Production and purification of human mAbs

293T cells were cultured in Pro293 CD serum-free medium, with Pluronic, without L-glutamine and phenol red (Lonza). Once confluent, 293T cells were cotransfected with 6 μg of IgH and IgL chain encoding plasmid DNA (pFUSEss-C HIg or pFUSEss-CLIg) with calcium phosphate. Transfection supernatants were collected 5 days after transfection and purified with protein A/G Sepharose (GE Healthcare). Purity was checked by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Binding and screening of anti–GP-ANDV human Ab

Human Abs were screened using a flow cytometry–based binding assay. Briefly, 293T cells expressing surface GPs from ANDV were used to assess the binding of sera from HCPS convalescent or healthy subjects (1:1000 dilution), supernatants from transfected cloned Abs (1:500 dilution), or concentrations of purified human polyclonal IgG or mAbs (0 to 15 μg/ml). Human sera, supernatants, or purified IgGs were incubated at 4°C for 1 hour followed by washes and staining with Alexa Fluor 488 anti-human IgG Ab at 4°C for 1 hour (1:2000; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Binding was analyzed by flow cytometry or confocal microscopy. The binding index was calculated by multiplying the percent of Alexa Fluor 488–positive cell by the MFI ratio, and the MFI ratio was calculated by dividing the MFI of the sample divided by the average MFI of negative controls. Polyclonal IgG was isolated from sera using the NAb Protein A/G Spin Kit and desalted using Zeba spin desalting columns according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Thermo Fisher Scientific). ANDV-GPC (Chile-9717869) was gene synthesized (Genewiz).

Neutralization assay

Heat-inactivated human sera obtained from 27 convalescent subjects and 5 healthy controls were analyzed for the presence of virus nAb by using an ANDV pv system. The neutralization activity was measured as a function of reduction in GFP expression in HEK293-IB3 cells (human embryonic kidney 293 cells stably expressing integrin β3). For the assay, pvs (9.25 ng/ml) were preincubated with dilutions of sera (1:50, 1:100, 1:500, 1:1000, 1:5000, 1:10,000, and 1:20,000) from ANDV convalescent or healthy control subjects in quadruplicate for 1 hour at 37°C in 96-well culture plates and used to transduce HEK293-IB3 cells. One set of control wells received cells only, another set received ANDV pv, and another set received VSV-G pv as an unrelated envelope control. After 16 hours of incubation, the virus was replaced with DMEM supplemented with 10% CCS, L-glutamine, and antibiotics. After 72 additional hours, cells were trypsinized and resuspended in 0.5% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Cells were analyzed for GFP expression by flow cytometry (BD LSRFortessa X-20). The data were quantified using FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc.). The percent of virus neutralization was determined by calculating the normalized percent reduction in the number of GFP-positive cells compared to control wells receiving only ANDV pv without sera.

Focus reduction neutralization test

JL16, MIB22, or isotype control Abs (0.1, 0.5, 2.5, 12.5, and 62.5 μg/ml) were mixed with equal volumes of 168 FFUs of ANDV (Chile-9717869) for 1 hour at 37°C and then added to Vero E6 cells in 24-well culture plates for 1 hour at 37°C. After adsorption, cells were washed with PBS and overlaid with medium containing 1.2% methylcellulose for 7 days. After methylcellulose removal, cells were fixed with methanol containing 0.5% hydrogen peroxide. Viral antigen was visualized by incubation with rabbit anti-serum (1:1000) followed by incubation with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Igs (1:1000) (Agilent) and diaminobenzidine (DAB)/metal concentrate as substrate. The neutralization activity of Abs was expressed as the Ab concentration that reduces the number of foci by 80% (47).

Measuring off-rate dissociation of mAbs

The Ab dissociation was measured according to the protocol of Geuijen et al. (31). 293T cells expressing ANDV-GP were incubated with saturating concentrations of Ab [MIB22, JL16, IgG P10, and IgG C4 (15 μg/ml each)] for 10 min on ice. Cells were then washed with cold PBS and incubated at 37°C for different periods of time (1 to 120 min). Then, cells were washed with cold PBS and stained with an Alexa Fluor 488–conjugated secondary anti-human IgG Ab. Last, cells were washed with cold PBS and resuspended on 0.5% PFA in PBS. The cell-associated Ab was analyzed by measuring the percent cell binding obtained a t = 0 that was set at 100%, and the subsequent time points were calculated as a percentage of this value.

Binding competition assay

mAb MIB22 was conjugated with SiteClick Qdot 655 Antibody Labeling Kit (Life Technologies), and mAb JL16 was conjugated with SiteClick Qdot 800 Antibody Labeling Kit (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For the binding competition assay, 293T cells expressing ANDV-GP (ANDV-GP-293T) were incubated with MIB22–Qdot 655 (20 μg/ml) following the incubation of JL16–Qdot 800 from 0 to 16 μg/ml. We also incubated ANDV-GP-293T cells with JL16–Qdot 800 (20 μg/ml) following the staining of MIB22–Qdot 650 from 0 to 16 μg/ml. Cells were washed between the staining and incubated at 4°C. Last, cells were resuspended on 0.5% PFA in PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry. As control of binding of conjugated mAbs, ANDV-GP-293T cells were stained with the conjugated Abs MIB22–Qdot 655 and JL16–Qdot 800 from 0 to 16 μg/ml at 4°C, resuspended on 0.5% PFA in PBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Virus inoculation and treatment with Abs

Twenty-four female Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) (Harlan Laboratories), 5 to 6 weeks of age, were intranasally inoculated with 200 FFUs of ANDV (Chile-9717869), diluted in 100 μl of sterile medium [DMEM–2.5% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, streptomycin (50 μg/ml), and penicillin (50 U/ml)]. Six hamsters were injected intraperitoneally at 3 and 8 DPI with either isotype control Ab (50 mg/kg), JL16 (50 mg/kg), MIB22 (50 mg/kg), or a cocktail of JL16 and MIB22 (25 mg/kg each). Hamsters were monitored daily for disease signs. Survivors were euthanized at 36 DPI, and sera and lung were collected for analysis.

Detection of ANDV loads by qRT-PCR

Lung samples were excised and placed into a 2-ml tube containing 500 μl of sterile DMEM and a stainless steel bead. Tissues were homogenized (10 min, 30 Hz) using a TissueLyser (Qiagen). Tubes were then centrifuged for 5 min at 8000g, and 140 μl was used for RNA extraction using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). qRT-PCR was performed using the Rotor-Gene RG-6000 instrument (Qiagen) and QuantiFast Probe RT-PCR kit (Qiagen), as previously described (48). Samples were compared to a standard curve using in vitro transcribed ANDV RNA fragment of known S-segment copy number. Total RNA was quantified using a NanoDrop 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

To detect reactivity of mAbs to ANDV pv, 96-well Costar plates (Corning) were coated overnight at 4°C with ANDV pv (10 ng per well). The plates were washed with PBS–0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and then blocked at 37°C for 1 hour with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS-T. Samples were 10-fold diluted in PBS-T starting at an Ab or purified IgG concentration of 10 μg/ml and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. After washes, plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour with a 1:5000 dilution in PBS of peroxidase-labeled goat anti-human IgG (H+L) Ab (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Plates were washed and developed with TMB (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine) substrate (eBioscience) and spectrophotometrically measured at 450 nm on a Victor3 plate reader (PerkinElmer).

To detect N-specific Abs, 96-well Nunc MaxiSorp plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) were coated overnight at 4°C with recombinant ANDV N antigen (2 μg/ml) in PBS (41). The plates were washed with PBS-T and then blocked at room temperature for 1 hour with 5% milk in PBS-T. Serum samples were twofold serially diluted in PBS, starting at a 1:100 dilution, and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. After another wash, plates were incubated at room temperature for 1 hour with a 1:2000 dilution in PBS of peroxidase-labeled goat anti-hamster IgG (H+L) Ab (SeraCare Life Sciences). After washing, the plate was incubated for 15 min with 2,2′-azino-di(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonate) (ABTS) two-component peroxidase substrate kit (SeraCare Life Sciences) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Plates were spectrophotometrically measured at 405 nm on a Synergy HTX plate reader (BioTek Instruments). Positive wells were determined by an optical density >3 SDs above the same dilution of ANDV-negative control hamster sera.

Statistical analysis

The IC50 (reciprocal of the sera dilution that causes 50% reduction in viral infectivity) and the inhibition curve slopes were calculated by fitting pooled data from four independent experiments to sigmoid dose response curves (variable slope). The FRNT80 (the concentration of Ab that causes an 80% reduction in the number of focus units) and the inhibition curve slopes were calculated by fitting pooled data from an experiment (three replicates) to sigmoid dose response curves. The 50% binding in the cell-based assay was calculated using nonlinear fit of transformed data. Survival analysis was determined by Mantel-Cox test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. The data were graphed using GraphPad Prism 6.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Neutralization assay.

Fig. S2. Single-cell sorting gating strategy.

Fig. S3. mAb binding.

Fig. S4. Binding competition assay.

Table S1. Primary data.

Acknowledgments:

We are grateful to the staff of Hospitals from Valdivia and Puerto Montt cities who help us to collect the samples and the participant subjects for their contribution. We thank O. Sanchez for sharing laboratory facility at University of Concepcion.

Funding:

This work was supported by the Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica, Gobierno de Chile (CONICYT), through grant FONDECYT 11140561, CONICYT FONDEF/I Concurso IDeA en Dos Etapas ID14I10084, and FONDEF ID14I20084 to M.I.B. in collaboration with Ichor Biologics, CONICYT/FONDEQUIP EQM150061, CONICYT/FONDEQUIP EQM150134, MECESUP UCO 1408-PM, and Universidad de Concepcion through grant VRID 214.036.042-1. Part of the work was supported by internal funding from Ichor Biologics to J.L.G., F.B., and M.I.B. In addition, this work was partially funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to H.F.

Footnotes

Competing interests: J.L.G., F.B., and M.I.B. have a pending patent application related to this work (U.S. Provisional 62/474,681) that covers hantavirus-specific human Abs. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencetranslationalmedicine.org/cgi/content/full/10/468/eaat6420/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Hjelle B, Torres-Pérez F, Hantaviruses in the Americas and their role as emerging pathogens. Viruses 2, 2559–2586 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaheri A, Strandin T, Hepojoki J, Sironen T, Henttonen H, Makela S, Mustonen J, Uncovering the mysteries of hantavirus infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 539–550 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez VP, Bellomo C, San Juan J, Pinna D, Forlenza R, Elder M, Padula PJ, Person-to-person transmission of Andes virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 1848–1853 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macneil A, Nichol ST, Spiropoulou CF, Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Virus Res. 162, 138–147 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Figueiredo LT, Souza WM, Ferres M, Enria DA, Hantaviruses and cardiopulmonary syndrome in South America. Virus Res. 187, 43–54 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez VP, Bellomo CM, Cacace ML, Suarez P, Bogni L, Padula PJ, Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in Argentina, 1995–2008. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16, 1853–1860 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams MJ, Lefkowitz EJ, King AMQ, Harrach B, Harrison RL, Knowles NJ, Kropinski AM, Krupovic M, Kuhn JH, Mushegian AR, Nibert M, Sabanadzovic S, Sanfaçon H, Siddell SG, Simmonds P, Varsani A, Zerbini FM, Gorbalenya AE, Davison AJ, Ratification vote on taxonomic proposals to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2016). Arch. Virol. 161, 2921–2949 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jonsson CB, Figueiredo LT, Vapalahti O, A global perspective on hantavirus ecology, epidemiology, and disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23, 412–441 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Padula P, Figueroa R, Navarrete M, Pizarro E, Cadiz R, Bellomo C, Jofre C, Zaror L, Rodriguez E, Murúa R, Transmission study of Andes hantavirus infection in wild sigmodontine rodents. J. Virol. 78, 11972–11979 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schountz T, Prescott J, Hantavirus immunology of rodent reservoirs: Current status and future directions. Viruses 6, 1317–1335 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vial PA, Valdivieso F, Mertz G, Castillo C, Belmar E, Delgado I, Tapia M, Ferrés M, Incubation period of hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 1271–1273 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mertz GJ, Hjelle B, Crowley M, Iwamoto G, Tomicic V, Vial PA, Diagnosis and treatment of new world hantavirus infections. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 19, 437–442 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartline J, Mierek C, Knutson T, Kang C, Hantavirus infection in North America: A clinical review. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 31, 978–982 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vial PA, Valdivieso F, Ferres M, Riquelme R, Rioseco ML, Calvo M, Castillo C, Díaz R, Scholz L, Cuiza A, Belmar E, Hernandez C, Martinez J, Lee S-J, Mertz GJ; Hantavirus Study Group in Chile, High-dose intravenous methylprednisolone for hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome in Chile: A double-blind, randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 57, 943–951 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mertz GJ, Miedzinski L, Goade D, Pavia AT, Hjelle B, Hansbarger CO, Levy H, Koster FT, Baum K, Lindemulder A, Wang W, Riser L, Fernandez H, Whitley RJ; Collaborative Antiviral Study Group, Placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of intravenous ribavirin for the treatment of hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome in North America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39, 1307–1313 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Custer DM, Thompson E, Schmaljohn CS, Ksiazek TG, Hooper JW, Active and passive vaccination against hantavirus pulmonary syndrome with Andes virus M genome segment-based DNA vaccine. J. Virol. 77, 9894–9905 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hooper JW, Ferro AM, Wahl-Jensen V, Immune serum produced by DNA vaccination protects hamsters against lethal respiratory challenge with Andes virus. J. Virol. 82, 1332–1338 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brocato R, Josleyn M, Ballantyne J, Vial P, Hooper JW, DNA vaccine-generated duck polyclonal antibodies as a postexposure prophylactic to prevent hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS). PLOS ONE 7, e35996 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valdivieso F, Vial P, Ferres M, Ye C, Goade D, Cuiza A, Hjelle B, Neutralizing antibodies in survivors of Sin Nombre and Andes hantavirus infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12, 166–168 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacNeil A, Comer JA, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Sin Nombre virus–specific immunoglobulin M and G kinetics in hantavirus pulmonary syndrome and the role played by serologic responses in predicting disease outcome. J. Infect. Dis. 202, 242–246 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bharadwaj M, Nofchissey R, Goade D, Koster F, Hjelle B, Humoral immune responses in the hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome. J. Infect. Dis. 182, 43–48 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vial PA, Valdivieso F, Calvo M, Rioseco ML, Riquelme R, Araneda A, Tomicic V, Graf J, Paredes L, Florenzano M, Bidart T, Cuiza A, Marco C, Hjelle B, Ye C, Hanfelt-Goade D, Vial C, Rivera JC, Delgado I, Mertz GJ; Hantavirus Study Group in Chile, A nonrandomized multicentre trial of human immune plasma for treatment of hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome caused by Andes virus. Antivir. Ther. 20, 377–386 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alvarez RA, Maestre AM, Law K, Durham ND, Barria MI, Ishii-Watabe A, Tada M, Kapoor M, Hotta MT, Rodriguez-Caprio G, Fierer DS, Fernandez-Sesma A, Simon V, Chen BK, Enhanced FCGR2A and FCGR3A signaling by HIV viremic controller IgG. JCI Insight 2, e88226 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gavrilovskaya IN, Shepley M, Shaw R, Ginsberg MH, Mackow ER, β3 Integrins mediate the cellular entry of hantaviruses that cause respiratory failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7074–7079 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthys VS, Gorbunova EE, Gavrilovskaya IN, Mackow ER, Andes virus recognition of human and Syrian hamster β3 integrins is determined by an L33P substitution in the PSI domain. J. Virol. 84, 352–360 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manigold T, Mori A, Graumann R, Llop E, Simon V, Ferrés M, Valdivieso F, Castillo C, Hjelle B, Vial P, Highly differentiated, resting Gn-specific memory CD8+ T cells persist years after infection by Andes hantavirus. PLOS Pathog. 6, e1000779 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marasco WA, Sui J, The growth and potential of human antiviral monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1421–1434 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weitkamp J-H, Kallewaard N, Kusuhara K, Feigelstock D, Feng N, Greenberg HB, Crowe JE Jr., Generation of recombinant human monoclonal antibodies to rotavirus from single antigen-specific B cells selected with fluorescent virus-like particles. J. Immunol. Methods 275, 223–237 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith K, Garman L, Wrammert J, Zheng N-Y, Capra JD, Ahmed R, Wilson PC, Rapid generation of fully human monoclonal antibodies specific to a vaccinating antigen. Nat. Protoc. 4, 372–384 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tiller T, Meffre E, Yurasov S, Tsuiji M, Nussenzweig MC, Wardemann H, Efficient generation of monoclonal antibodies from single human B cells by single cell RT-PCR and expression vector cloning. J. Immunol. Methods 329, 112–124 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geuijen CAW, Clijsters-van der Horst M, Cox F, Rood PML, Throsby M, Jongeneelen MAC, Backus HHJ, van Deventer E, Kruisbeek AM, Goudsmit J, de Kruif J, Affinity ranking of antibodies using flow cytometry: Application in antibody phage display-based target discovery. J. Immunol. Methods 302, 68–77 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hooper JW, Larsen T, Custer DM, Schmaljohn CS, A lethal disease model for hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Virology 289, 6–14 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez VP, Padula PJ, Induction of protective immunity in a Syrian hamster model against a cytopathogenic strain of Andes virus. J. Med. Virol. 84, 87–95 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Safronetz D, Ebihara H, Feldmann H, Hooper JW, The Syrian hamster model of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Antiviral Res. 95, 282–292 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boletín Epidemiológico de Hantavirus. Situación al 15 enero de 2018 (2018); http://epi.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/hantavirus_SE522017.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karesh WB, Dobson A, Lloyd-Smith JO, Lubroth J, Dixon MA, Bennett M, Aldrich S, Harrington T, Formenty P, Loh EH, Machalaba CC, Thomas MJ, Heymann DL, Ecology of zoonoses: Natural and unnatural histories. Lancet 380, 1936–1945 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jenison S, Yamada T, Morris C, Anderson B, Torrez-Martinez N, Keller N, Hjelle B, Characterization of human antibody responses to four corners hantavirus infections among patients with hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. J. Virol. 68, 3000–3006 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu X, Yang Z-Y, Li Y, Hogerkorp C-M, Schief WR, Seaman MS, Zhou T, Schmidt SD, Wu L, Xu L, Longo NS, McKee K, O’Dell S, Louder MK, Wycuff DL, Feng Y, Nason M, Doria-Rose N, Connors M, Kwong PD, Roederer M, Wyatt RT, Nabel GJ, Mascola JR, Rational design of envelope identifies broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to HIV-1. Science 329, 856–861 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hooper JW, Brocato RL, Kwilas SA, Hammerbeck CD, Josleyn MD, Royals M, Ballantyne J, Wu H, Jiao J-A, Matsushita H, Sullivan EJ, DNA vaccine–derived human IgG produced in transchromosomal bovines protect in lethal models of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 264ra162 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Safronetz D, Zivcec M, Lacasse R, Feldmann F, Rosenke R, Long D, Haddock E, Brining D, Gardner D, Feldmann H, Ebihara H, Pathogenesis and host response in Syrian hamsters following intranasal infection with Andes virus. PLOS Pathog. 7, e1002426 (201. 1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prescott J, Safronetz D, Haddock E, Robertson S, Scott D, Feldmann H, The adaptive immune response does not influence hantavirus disease or persistence in the Syrian hamster. Immunology 140, 168–178 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duggal NK, Ritter JM, Pestorius SE, Zaki SR, Davis BS, Chang G-JJ, Bowen RA, Brault AC, Frequent Zika virus sexual transmission and prolonged viral RNA shedding in an immunodeficient mouse model. Cell Rep. 18, 1751–1760 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker LM, Burton DR, Passive immunotherapy of viral infections: ‘Super-antibodies’ enter the fray. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 297–308 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marston HD, Paules CI, Fauci AS, monoclonal antibodies for emerging infectious diseases—Borrowing from history. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1469–1472 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barría MI, Garrido JL, Stein C, Scher E, Ge Y, Engel SM, Kraus TA, Banach D, Moran TM, Localized mucosal response to intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccine in adults. J. Infect. Dis. 207, 115–124 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soneoka Y, Cannon PM, Ramsdale EE, Griffiths JC, Romano G, Kingsman SM, Kingsman AJ, A transient three-plasmid expression system for the production of high titer retroviral vectors. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 628–633 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ye C, Prescott J, Nofchissey R, Goade D, Hjelle B, Neutralizing antibodies and Sin Nombre virus RNA after recovery from hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10, 478–482 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Safronetz D, Haddock E, Feldmann F, Ebihara H, Feldmann H, In vitro and in vivo activity of ribavirin against Andes virus infection. PLOS ONE 6, e23560 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Neutralization assay.

Fig. S2. Single-cell sorting gating strategy.

Fig. S3. mAb binding.

Fig. S4. Binding competition assay.

Table S1. Primary data.