Abstract

Excessive use of the internet, which is a typical scenario of self‐control failure, could lead to potential consequences such as anxiety, depression, and diminished academic performance. However, the underlying neuropsychological mechanisms remain poorly understood. This study aims to investigate the structural basis of self‐control and internet addiction. In a cohort of 96 internet gamers, we examined the relationships among grey matter volume and white matter integrity within the frontostriatal circuits and internet addiction severity, as well as self‐control measures. The results showed a significant and negative correlation between dACC grey matter volume and internet addiction severity (p < 0.001), but not with self‐control. Subsequent tractography from the dACC to the bilateral ventral striatum (VS) was conducted. The fractional anisotropy (FA) and radial diffusivity of dACC‐right VS pathway was negatively (p = 0.011) and positively (p = 0.020) correlated with internet addiction severity, respectively, and the FA was also positively correlated with self‐control (p = 0.036). These associations were not observed for the dACC‐left VS pathway. Further mediation analysis demonstrated a significant complete mediation effect of self‐control on the relationship between FA of the dACC‐right VS pathway and internet addiction severity. Our findings suggest that the dACC‐right VS pathway is a critical neural substrate for both internet addiction and self‐control. Deficits in this pathway may lead to impaired self‐regulation over internet usage, exacerbating the severity of internet addiction.

Keywords: dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, DTI, internet addiction, prefrontal‐striatum circuits, self‐control, VBM

The fractional anisotropy (FA) and radial diffusivity of dACC‐right VS pathway was negatively and positively correlated with internet addiction severity, respectively, and the FA was also positively correlated with self‐control. These associations were not observed for the dACC‐left VS pathway. Further mediation analysis demonstrated a significant complete mediation effect of self‐control on the relationship between FA of the dACC‐right VS pathway and internet addiction severity.

1. INTRODUCTION

The exponential growth of internet usage and the proliferation of online gaming platforms in today's society have given rise to a new form of behavioural addiction known as internet addiction, which has received much attention during the past decades. Despite the lack of a clinical diagnosis for internet addiction, researchers universally acknowledge and affirm the existence of this phenomenon, which can be characterized as an impulse‐control disorder that does not involve the use of intoxicating substances. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 Excessive use of the internet could lead to anxiety, depression, and adverse mental health, finally affecting students' academic performance. 6 A previous meta‐analysis has also identified that internet addiction was associated with significant cognitive deficits in working memory, attentional inhibition, motor inhibition, and decision making. 7 These results indicate that it is crucial to develop efficient interventions to prevent internet addiction. However, the underlying neuropsychological mechanism of internet addiction is still unclear.

Previous studies suggested that deficits in self‐control, which refers to the ability to regulate one's thoughts, emotions, and behaviours in the pursuit of long‐term goals, may play a significant role in modulating individuals' addictive behaviours. Specifically, individuals with internet addiction displayed significantly lower levels of self‐control 8 , 9 and a negative correlation was found between self‐control and the severity of internet addiction, 10 including its manifestations such as online game addiction, 11 , 12 which is a major form of internet use and has been officially included in the ICD‐11 by World Health Organization. 13 Previous studies have identified that the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) is an essential neural substrate underlying both self‐control and addiction behaviour. 14 , 15 For example, previous human studies have found that reduced dACC activity in response to errors predicts cocaine relapse, 16 while increased dACC activity is observed in individuals who have successfully maintained long‐term cocaine abstinence. 17 Our previous work has further identified dysfunctional frontostriatal circuits in substance use disorders, and a pivotal imbalance between the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and dACC/prelimbic circuits in both individuals struggling with compulsive drug use and rats exhibiting addictive‐like behaviour. 18 , 19 Moreover, we have further found that the resting‐state functional connectivity between the dACC and the right ventral striatum (rVS), but not the left ventral striatum (lVS), partially mediated the relationship between self‐control scores and internet addiction severity, 12 indicating the essential role that dACC‐rVS pathway plays in modulating self‐control and internet addiction. Despite this functional evidence highlighting the interplay between dACC, self‐control, and internet addiction, the underlying structural substrates remain elusive.

Voxel‐based morphometry (VBM) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) techniques offer distinct advantages for scrutinizing brain structure. VBM, which allows for a comprehensive and unbiased examination of the entire brain, 20 has been widely applied in mental disorders to find evidence of grey matter changes between patients and healthy controls. Previous quantitative meta‐analysis has identified that several brain regions displayed consistent grey matter volume decrease in the population of addiction relative to healthy controls, including bilateral dACC and insula. 21 In contrast, DTI is a noninvasive method that can provide estimates of brain structural connectivity through white matter fibre tractography 22 and has been used in addiction investigations. 23 Previous studies have identified that chronic alcoholics lost white matter, 24 and lower fractional anisotropy (FA) of white matter was found in individuals with alcohol use disorder compared with controls. Moreover, FA in the right superior longitudinal fasciculus and left posterior corona radiata was negatively associated with impulsivity. 25 , 26 The complementary information on abnormalities in white matter fibre bundles provided by DTI technology can advance our understanding of the pathogenesis of addiction. It also can be used to identify potential targets for brain‐based interventions, wherein stimulation applied to a specific area on the cortical surface can modulate the plasticity of aberrant pathways. 27

Here, we combined both VBM and DTI to investigate the structural substrates associated with the severity of internet addiction. Considering large heterogeneity in the purpose of internet use but only internet gaming has been officially classified as a mental disorder, we mainly focused on individuals who reported engaging in internet gaming. Based on previous findings from both resting‐state and structural studies, 12 , 18 , 19 , 21 we hypothesized that (1) the grey matter volume of dACC would be negatively correlated with the severity of internet addiction and positively correlated with self‐control; (2) the integrity of white matter pathway between dACC and rVS would be negatively correlated with the severity of internet addiction and positively correlated with self‐control; (3) the integrity of dACC‐rVS pathway may influence the severity of internet addiction by affecting levels of self‐control.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

One hundred and forty participants were recruited through online advertisement. Information regarding internet addiction, symptoms of internet gaming disorder (IGD), the level of self‐control, anxiety, depression, and demography were surveyed. Particularly, we asked the participants to report whether they played internet games or not. In addition, two catch trials were designed to exclude individuals who filled the survey carelessly. Two participants were excluded because of missing data. The participants who reported “do not play internet games” (n = 37), or made incorrect response in catch trials (n = 2) were excluded. The participants whose anxiety, depression, or self‐control score was more than three standard deviations away from the group mean were excluded (n = 2). Apart from this, for each participant, the scores of IGD (assessed by DSM, detailed below) and internet addiction (assessed by internet addiction test, IAT, detailed below) were transformed to Z scores, and the difference between two Z scores was calculated. The participants whose difference was away from the group mean more than three standard deviations, indicating they did not report symptoms consistently, had also been excluded (n = 1). With these exclusion criteria, 96 gamers aged from 18 to 28 were left for MRI analysis (age = 20.59 ± 2.27, 57 males; Table 1). To note, we further excluded four participants whose white matter indexes, namely, FA, radial diffusivity (RD), or axial diffusivity (AD), exceeded three standard deviations when performing partial correlations on white matter indexes against other variables, leaving 92 participants (age = 20.54 ± 2.24, 56 males) in all analyses concerning white matter indexes. It is important to note that data points more than 3 standard deviations from the mean in those variables were excluded to mitigate the violation of the normality assumption in parametric statistical tests. This is a standard practice to remove outliers that could unduly influence the results. 28 , 29 , 30 The resultant data for each variable, except for depression, had standardized skewness and kurtosis coefficients within ±3.29, which are considered indicative of a normal distribution. 31 , 32 All subjects have normal or corrected to normal vision, and none reported a history of psychiatric or neurological disorders.

TABLE 1.

Demographic information of participants (n = 96).

| Gamers | ||

|---|---|---|

| N | 96 | |

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 20.59 (2.27) |

| Range | [17, 28] | |

| Gender | N of Male | 57 |

| N of Female | 39 | |

| DSM | Mean (SD) | 2.26 (2.02) |

| ≥5 N | 17 | |

| ≥5 N of Male | 11 | |

| ≥5 N of Female | 6 | |

| SCS | Mean (SD) | 15.94 (2.39) |

| IAT | Mean (SD) | 45.35 (10.63) |

| Anxiety | Mean (SD) | 11.05 (3.35) |

| Depression | Mean (SD) | 9.52 (3.43) |

Abbreviations: IAT, internet addiction test; SCS, self‐control score.

This study was approved by the Ethic Committee of Zhejiang University. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals prior to study enrolment, and participants received financial compensation for their participation.

2.2. Questionnaire assessments

2.2.1. Internet addiction test

The IAT was used to assess the severity of internet addiction, 33 and it has been proved to have sufficient reliability and validity among Chinese adolescents. 34 The test comprises six distinct dimensions, namely, Salience, Excessive use, Neglect work, Anticipation, Lack of control, and Neglect social life. The number of items in each dimension is 5, 5, 3, 2, 3, and 2, respectively, with a total of 20 items. Participants rated each item on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The overall test score, denoted as IAT in subsequent sections, is calculated by summing the scores of all items. A higher test score reflects a greater severity of internet addiction.

2.2.2. Self‐Control Scale (SCS)

The Chinese version of SCS was used to measure self‐control. 35 , 36 Five dimensions are included in the scale, namely, Impulse control, Healthy habit, Resistance to temptation, Work focus, and Appropriate entertainment, and the numbers of items of these dimensions are 6, 3, 4, 3, and 3, respectively, with a total of 19 items. For each item, the participants were instructed to score from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) according to how well the item fits their daily lives. The score of each dimension is the mean score of items in this dimension, and the total score of self‐control is the sum of all dimensions' scores.

2.2.3. Internet Gaming Disorder Scale

The severity of IGD was assessed by the nine criteria recommended in DSM‐5. 37 , 38 A previous study has demonstrated the robust internal consistency and test–retest reliability of the Chinese version of Internet Gaming Disorder Scale. 39 Participants were required to respond with either “yes” or “no” to indicate whether they had exhibited specific symptoms over the past 12 months. Online gambling was excluded from this criterion. The total number of symptoms a participant met was defined as the score of the scale. In contrast to a binary diagnostic approach, it has been recommended to characterize IGD with multiple severity levels in DSM‐5. 38 Building upon our previous studies, 18 , 40 the present study used the number of IGD symptoms, as a proxy for IGD risk (which is referred to as DSM in the following sections), with a higher score indicative of a greater risk of IGD.

2.2.4. Measures used as confounding variables

Anxiety and depression dimensions in the Brief Symptom Inventory were used to characterize symptoms of anxiety and depression. 41 Each dimension includes six items. For each item, the participants were instructed to choose from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) according to how well the item fits their daily lives. The sum of six items was used to measure the severity of anxiety or depression, and a higher sum indicates more severe symptoms.

2.2.5. Imaging data collection

The neuroimaging data were acquired by a 3T Siemens Prisma scanner using a 20‐channel coil at the Center for Brain Imaging Science and Technology (CBIST), Zhejiang University. The high‐resolution anatomical images were collected using a T1‐weighted 3D magnetization‐prepared rapid gradient echo sequence with the following parameters: TR/TE = 2300 /2.32 ms; flip angle = 8°; FOV = 240 × 240 mm2; matrix = 256 × 256; voxel size = 0.94 × 0.94 × 0.9 mm3; and 208 slices in the sagittal panel. Diffusion‐weighted images were acquired with the following parameters: TR/TE = 3230/89.2 ms; flip angle = 78°; FOV = 210 × 210 mm2; matrix = 140 × 140; voxel size = 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm3; 90 directions with multiple b‐values of 1000, 2000, and 3000 s/mm2, along with six images with no diffusion gradient applied (b value = 0). Opposite phase encoding directions, that is, anterior–posterior (AP) and posterior–anterior (PA), were both performed.

2.2.6. VBM preprocessing

VBM analysis was performed using CAT12 toolbox (http://www.neuro.uni-jena.de/cat/) implemented in SPM12 (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). The processing of T1‐weighted anatomic images included (1) correction for bias‐field inhomogeneity, (2) segmentation into grey matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid, (3) normalization to the DARTEL template in MNI space (with voxel size being resampled to 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm3), (4) modulation of grey matter to preserve regional amount, and (5) spatial smoothing of modulated grey matter with a Gaussian blurring kernel of 10‐mm full width at half.

2.2.7. Diffusion tensor image (DTI) preprocessing

DTI analysis was performed using MRIcron, 42 FDT tool of FSL, 43 and AFNI. 44 The DTI preprocessing followed a typical processing pipeline including (1) EPI distortion correction using TOPUP, (2) motion and eddy current distortion correction using eddy, (3) calculation of FA, AD, and RD using dtifit, and (4) averaging of resultant images from AP and PA encoding directions using 3dMean command of AFNI. The formula for calculating FA is as follows:

The , , and are the eigenvalues (or principal diffusivities) and the higher the FA, the healthier the nerve fibre bundles. 45 We used to represent the AD and to represent the RD. Similar to the FA, the higher the AD, the healthier the axon, 46 and the lower the RD, the more intact the myelin sheath. 47 , 48

The DTI analysis was conducted at a region of interest (ROI) level after VBM. Specifically, the dACC region showing significant correlation with IAT in the VBM analysis was defined as the ROI in the cortex. Based on our previous studies showing that the dACC and rVS form a “stop” pathway, 18 a spherical ROI was placed in the rVS (MNI coordinates [x = 9, y = 9, z = −8] with a radius of 6 mm). We first used dACC and rVS as the starting and ending points, respectively, to perform tractography, using FSL commands bedpost_gpu and probtrackx2_gpu. Next, we exchanged the starting and ending points and performed tractography once again. The two tracking results were added and binarized as the mask for each participant. Then the masks were summed across participants, and then voxels in the dACC mask or the VS mask or the left hemisphere were eliminated. Subsequently, we refined the mask by a white matter mask generated by applying a threshold of 0.5 to the white matter probability map. Ultimately, a voxel would be retained in the final pathway mask if it was traversed by the identified dACC‐rVS pathway in 80% of the participants. The same procedure was performed between dACC and lVS (MNI coordinates [x = −9, y = 9, z = −8] with a radius of 6 mm). Imaging metrics characterizing white matter integrity including FA, AD, and RD values for each participant within the masks were exacted for latter statistical analyses.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The relationship between addiction symptoms (DSM, IAT) and other variables, such as anxiety, depression scores, and age, were tested by correlation analyses, and gender differences on DSM and IAT were tested by independent T tests.

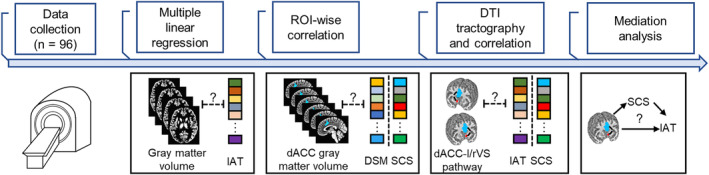

We first performed multiple regression analysis on grey matter volume and IAT scores (Figure 1). The total intracranial volume (TIV), age, gender, depression score, and anxiety score were used as covariates. As our main focus lies in the grey matter volume of the dACC, our analyses were confined to a mask encompassing the entire dACC region. Specifically, the mask was generated by merging Brodmann Area 6, 8, 24, and 32. Clusters with p < 0.05 (FDR corrected) was considered as significant. The grey matter volume of the dACC cluster showing significant correlation was further extracted for correlation with DSM and self‐control.

FIGURE 1.

Analysis pipeline. Abbreviations: IAT, internet addiction test; SCS, self‐control score.

Next, we examined the relationship between dACC‐rVS white matter integrity and internet addiction symptoms. Specifically, we extracted FA, AD, and RD values from the dACC‐rVS white matter pathway, and correlated these indexes with IAT scores, with age, gender, depression score, and anxiety score as covariates. The same statistical analyses were performed for the dACC‐lVS pathway to characterize the laterality in brain‐behavioural association for internet addiction. Given that the laterality effect in correlation between the IAT and white matter indexes of dACC‐rVS and dACC‐lVS may be biased by bundle size and subtle anatomic difference in the two fibre tracks, we mirrored the two white matter masks along the x‐axis. Subsequently, we extracted white matter indexes from the mirrored masks, specifically dACC‐rVS_flip and dACC‐lVS_flip, and conducted the correlation analysis. The same complementary analyses were also conducted for self‐control.

To examine whether individual differences in grey matter volume covariates with white matter integrity, partial correlation analyses on the grey matter volume of the dACC against FA and RD values were performed, with age, gender, depression score, and anxiety score as covariates.

Lastly, to reveal which dimension of IAT and self‐control is mostly related with structural characteristics, partial correlation analyses were performed between each subscale score and grey matter volume of dACC, as well as with white matter indexes. Further mediation analysis was performed to characterize the relationship between structural indexes, IAT, and self‐control.

3. RESULTS

A descriptive summary of demographic and questionnaire data were provided in Table 1. The correlation analyses displayed that both DSM and IAT scores were negatively correlated with self‐control, and DSM was also positively correlated with depression score and anxiety score, whereas IAT was positively correlated with anxiety score only (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

The correlation between DSM, IAT, and other variates (n = 96).

| DSM [95% CI] | IAT [95% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SCS | r | −0.40 [−0.56, −0.22] | −0.57 [−0.69, −0.42] |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| ANXIETY | r | 0.23 [0.04, 0.42] | 0.37 [0.18, 0.53] |

| p | 0.022 | <0.001 | |

| DEPRESSION | r | 0.26 [0.06, 0.44] | 0.19 [−0.01, 0.37] |

| p | 0.010 | 0.067 | |

| GENDER | t | −1.78 [−1.57, 0.08] | 1.95 [−0.08, 8.56] |

| p | 0.078 | 0.055 | |

| AGE | r | 0.05 [−0.15, 0.25] | −0.06 [−0.25, 0.15] |

| p | 0.607 | 0.593 | |

Notes: The 95% CI for T test indicates the CI for mean difference between males and females. The boldface is used to highlight significant results.

Abbreviations: IAT, internet addiction test; SCS, self‐control score.

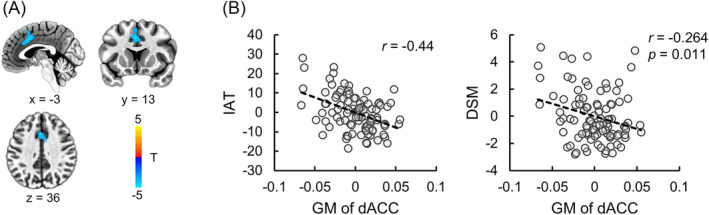

3.1. dACC grey matter volume is inversely correlated with IAT but not self‐control

Multiple regression analysis showed that after controlling for TIV, depression, anxiety scores, age, and gender, a cluster located at dACC (MNI coordinates: x = −1.5, y = 13.5, z = 39, cluster size: 908) was found negatively correlated with IAT score, which survived FDR correction (Figure 2A,B). The grey matter volume was extracted from the dACC region (with a threshold p < 0.01) and further correlated with DSM score, similarly, a significant negative correlation was found (Figure 2B). The correlation between grey matter volume of dACC and self‐control score was not significant (r = 0.15, p = 0.167).

FIGURE 2.

VBM results. (A) Multiple regression indicated the grey matter volume of dACC was negatively correlated with IAT scores after controlling for total intracranial volume, depression, anxiety scores and age as well as gender. (B) Partial correlation scatter plot of dACC grey matter volume and IAT, DSM scores. Abbreviations: GM, grey matter volume; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; IAT, internet addiction test.

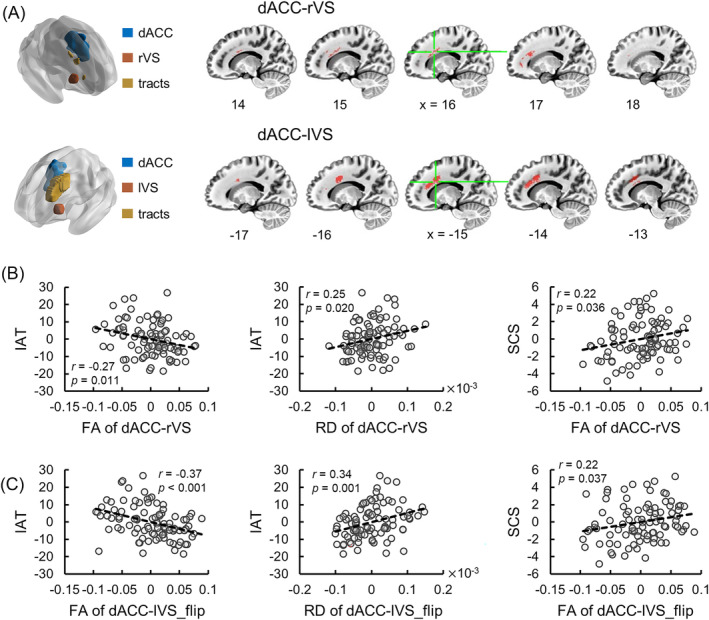

3.2. White matter integrity of fibre track connecting dACC and right ventral striatum is inversely correlated with IAT and positively correlated with self‐control

The DTI tractography analysis identified white matter connections between dACC and rVS, lVS, respectively (Figure 3A). We further extracted the FA, AD, and RD values from these two masks and correlated them with IAT and self‐control scores, using depression, anxiety scores, age, and gender as covariates. The results showed the FA of dACC‐rVS white matter connection was significantly negatively correlated with IAT scores of individuals (Figure 3B; r = −0.27, 95% CI [−0.45, −0.08], p = 0.011), whereas the RD of this pathway was positively correlated with IAT scores (Figure 3B; r = 0.25, 95% CI [0.06, 0.42], p = 0.020). As for self‐control, a significantly positive correlation was found between self‐control score and FA of dACC‐rVS white matter pathway (Figure 3B; r = 0.22, 95% CI [0.02, 0.39], p = 0.036). No significant correlation was found between white matter indexes of dACC‐lVS and IAT or self‐control (p min = 0.537). As the identified white matter connection masks of dACC‐rVS and dACC‐lVS pathways were asymmetrical, we mirrored two masks and extracted white matter indexes from dACC‐rVS_flip and dACC‐lVS_flip masks to examine whether the correlation difference was induced by this asymmetry. The results showed that three indexes of the flipped dACC‐rVS pathway did not correlate with IAT or self‐control scores (p min = 0.264), whereas the FA and RD of flipped dACC‐lVS pathway was negatively and positively correlated with IAT (Figure 3C; r = −0.37, 95% CI [−0.53, −0.20], p < 0.001; r = 0.34, 95% CI [0.17, 0.48], p = 0.001), respectively, and the FA of flipped dACC‐lVS pathway was positively correlated with self‐control scores (Figure 3C; r = 0.22, 95% CI [0.03, 0.41], p = 0.037), indicating that the irrelevance between white matter properties of the left pathway and IAT was not induced by voxel location difference. The correlation between DSM and white matter indexes was not significant (p min = 0.135).

FIGURE 3.

DTI results. (A) Bilateral dACC‐VS white matter pathways identified by tractography. (B) Correlations between white matter indexes of dACC‐rVS pathway and IAT, self‐control scores. (C) Correlations between white matter indexes of flipped dACC‐lVS pathway and IAT, self‐control scores. Abbreviations: rVS, right ventral striatum; lVS, left ventral striatum; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; IAT, internet addiction test; SCS, self‐control score; FA, fractional anisotropy; RD, radial diffusivity.

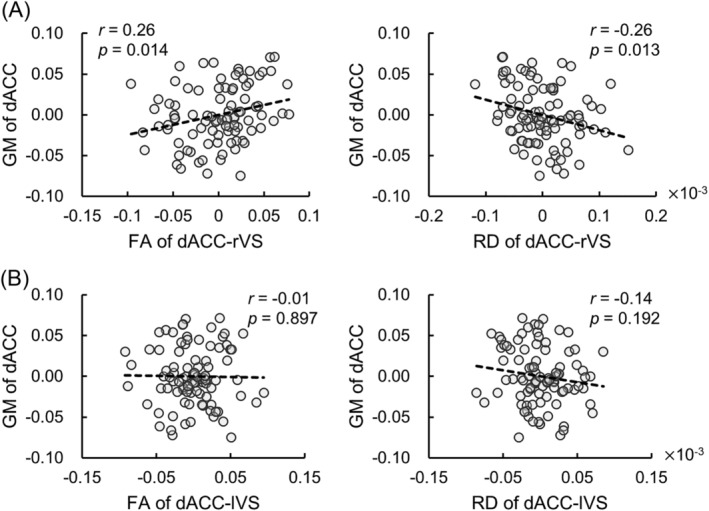

3.3. dACC grey matter volume is positively correlated with white matter integrity of the fibre track connecting to right ventral striatum

The partial correlation analyses showed that grey matter volume of dACC was positively correlated with FA of dACC‐rVS pathway (r = 0.26, 95% CI [0.08, 0.45], p = 0.014, Figure 4A) and negatively correlated with RD (r = −0.26, 95% CI [−0.44, −0.09], p = 0.013, Figure 4A). The relationship between grey matter volume of dACC and white matter indexes of dACC‐lVS pathway was not significant (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Partial correlation between grey matter volume of dACC and DTI indexes. (A) Grey matter volume of dACC was positively and negatively correlated with FA and RD of dACC‐rVS pathway, respectively. (B) no significant correlation was found between grey matter volume of dACC and FA or RD of dACC‐lVS pathway. Abbreviations: GM, grey matter volume; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; rVS, right ventral striatum; lVS, left ventral striatum; FA, fractional anisotropy; RD, radial diffusivity.

3.4. White matter indexes of dACC‐rVS pathway were correlated with subscales of IAT and self‐control

To further investigate which dimension of IAT and self‐control scale was mostly correlated with the structural indexes of dACC‐rVS pathway, we performed partial correlation analyses. The results indicated that the grey matter volume of dACC was negatively correlated with Salience, Excessive use, Neglect work, Anticipation, and Lack of control subscales of IAT (Table 3), but no significant correlation was found between grey matter volume of dACC and any subscale of self‐control (Table 3). As for the white matter indexes, significant correlation was found between FA of dACC‐rVS pathway and Excessive use, Lack of control subscales of IAT (Table 3). In addition, the FA of dACC‐rVS pathway was positively correlated with Appropriate entertainment subscale of self‐control (Table 3). Similar results were found between RD of dACC‐rVS pathway and subscales of IAT, and self‐control (Table 3). No significant correlation was found between white matter indexes of dACC‐lVS pathway and any subscale of IAT or self‐control (p min = 0.085). Moreover, the Excessive use, Lack of control subscales of IAT, and Appropriate entertainment subscale of SCS were found negatively and positively correlated with the FA of flipped dACC‐lVS pathway (Excessive use: r = −0.36, 95% CI [−0.53, −0.18], p = 0.001; Lack of control: r = −0.33, 95% CI [−0.51, −0.14], p = 0.001; Appropriate entertainment: r = 0.24, 95% CI [0.03, 0.43], p = 0.025), respectively, but not with the FA of flipped dACC‐rVS pathway (p min = 0.603). The Excessive use, Lack of control subscales of IAT were positively correlated with the RD of flipped dACC‐lVS pathway (Excessive use: r = 0.35, 95% CI [0.18, 0.51], p < 0.001; Lack of control: r = 0.34, 95% CI [0.17, 0.51], p = 0.001), but not with the RD of flipped dACC‐rVS pathway (p min = 0.193).

TABLE 3.

Correlations between structural indexes of dACC‐rVS pathway and subscales of IAT and self‐control.

| GM of dACC | IAT | |||||||||||

| Salience | Excessive use | Neglect work | Anticipation | Lack of control | Neglect social life | |||||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |

|

−0.38 [−0.56, −0.19] |

<0.001 |

−0.40 [−0.57, −0.19] |

<0.001 |

−0.29 [−0.49, −0.08] |

0.005 |

−0.27 [−0.45, −0.10] |

0.009 |

−0.34 [−0.53, −0.11] |

0.001 |

−0.18 [−0.39, 0.06] |

0.097 | |

| SCS | ||||||||||||

| Appropriate entertainment | Work focus | Resistance to temptation | Healthy habit | Impulse control | ||||||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |||

|

0.06 [−0.16, 0.26] |

0.602 |

0.14 [−0.09, 0.34] |

0.197 |

0.08 [−0.13, 0.30] |

0.465 |

0.17 [−0.01, 0.35] |

0.099 |

0.07 [−0.15, 0.27] |

0.500 | |||

| FA of dACC‐rVS | IAT | |||||||||||

| Salience | Excessive use | Neglect work | Anticipation | Lack of control | Neglect social life | |||||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |

|

−0.20 [−0.39, −0.01] |

0.067 |

−0.28 [−0.46, −0.08] |

0.008 |

−0.20 [−0.38, 0.003] |

0.056 |

−0.20 [−0.37, 0.01] |

0.066 |

−0.22 [−0.41, −0.04] |

0.041 |

−0.02 [−0.24, 0.18] |

0.854 | |

| SCS | ||||||||||||

| Appropriate entertainment | Work focus | Resistance to temptation | Healthy habit | Impulse control | ||||||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |||

|

0.28 [0.08, 0.45] |

0.008 |

0.12 [−0.08, 0.29] |

0.268 |

0.14 [−0.05, 0.32] |

0.194 |

0.11 [−0.08, 0.29] |

0.309 |

0.15 [−0.05, 0.34] |

0.165 | |||

| RD of dACC‐rVS | IAT | |||||||||||

| Salience | Excessive use | Neglect work | Anticipation | Lack of control | Neglect social life | |||||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |

|

0.17 [−0.04, 0.35] |

0.121 |

0.28 [0.08, 0.45] |

0.008 |

0.18 [−0.003, 0.34] |

0.097 |

0.17 [−0.03, 0.34] |

0.125 |

0.25 [0.07, 0.45] |

0.020 |

−0.03 [−0.23, 0.19] |

0.802 | |

| SCS | ||||||||||||

| Appropriate entertainment | Work focus | Resistance to temptation | Healthy habit | Impulse control | ||||||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |||

|

−0.23 [−0.42, −0.02] |

0.034 |

−0.10 [−0.31, 0.11] |

0.342 |

−0.12 [−0.31, 0.07] |

0.269 |

−0.06 [−0.24, 0.13] |

0.596 |

−0.16 [−0.35, 0.07] |

0.147 | |||

Note: The boldface is used to highlight significant results.

3.5. Self‐control mediated the relationship between FA of dACC‐rVS pathway and internet addiction severity

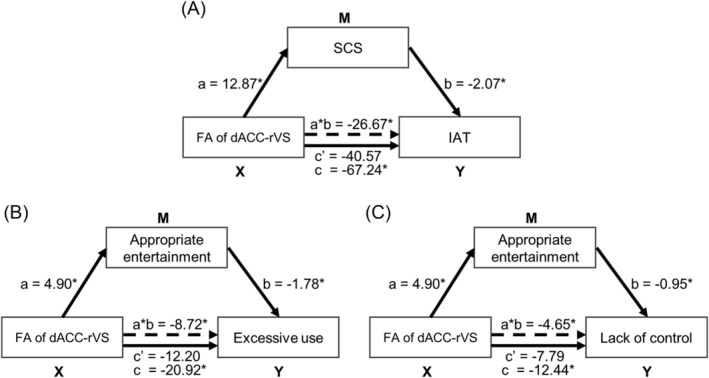

Further mediation analyses showed that self‐control completely mediated the relationship between FA of dACC‐rVS and IAT (Figure 5). Specifically, a significant total effect of FA of dACC‐rVS on IAT was identified (c = −67.24, p = 0.012). The mediation effect of self‐control was significant (a * b = −26.67, bootstrapped 95% CI [−52.08, −4.12], p < 0.05), and the direct effect of FA of dACC‐rVS on IAT was not significant (c′ = −40.57, p = 0.088). Based on the above findings, the FA of dACC‐rVS was positively correlated with the subscale of self‐control, namely, Appropriate entertainment, and negatively correlated with subscales of IAT, namely, Excessive use and Lack of control. To further investigate how the subscale of self‐control mediated the relationship between FA of dACC‐rVS and subscales of IAT, we constructed two mediation models, with Appropriate entertainment served as mediator, Excessive use, and Lack of control served as dependent variables, respectively. The results revealed a complete mediation effect of Appropriate entertainment on the relationship between FA of dACC‐rVS and Excessive use, Lack of control, respectively (Figure 5). Specifically, the total effect of FA of dACC‐rVS on Excessive use was significant (c = −20.92, p = 0.008), and the mediation effect of Appropriate entertainment was also significant (a * b = −8.72, bootstrapped 95% CI [−15.27, −2.62], p < 0.05). No significant direct effect of FA of dACC‐rVS on Excessive use was found (c′ = −12.20, p = 0.101). In addition, the total effect of dACC‐rVS on Lack of control was significant (c = −12.44, p = 0.041), and the mediation effect was also significant (a * b = −4.65, bootstrapped 95% CI [−9.27, −0.72], p < 0.05). No significant direct effect of FA of dACC‐rVS on Lack of control was found (c′ = −7.79, p = 0.198).

FIGURE 5.

Results of mediation analysis. (A) Self‐control completely mediates the relationship between FA of dACC‐rVS pathway and internet addiction severity. (B) Appropriate entertainment subscale of self‐control completely mediates the relationship between FA of dACC‐rVS pathway and Excessive use subscale of internet addiction. (C) Appropriate entertainment subscale of self‐control completely mediates the relationship between FA of dACC‐rVS pathway and lack of control subscale of internet addiction. Abbreviations: SCS, self‐control score; IAT, internet addiction test; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; rVS, right ventral striatum; FA, fractional anisotropy.

4. DISCUSSION

In the current study, we investigated the structural basis of frontostriatal circuits underlying internet addiction. The results demonstrated that the grey matter volume of the dACC was negatively correlated with the severity of addiction assessed by both DSM and IAT, but not with self‐control. White matter pathways between the dACC and bilateral VS were identified by DTI tractography and the FA and RD of dACC‐rVS pathway were negatively and positively correlated with IAT, respectively. In addition, FA of the dACC‐rVS pathway was positively correlated with self‐control. No significant relationship was found between the white matter indexes of dACC‐lVS pathway and self‐control or internet addiction severity. Further mediation analyses revealed that the Appropriate entertainment subscale of self‐control completely mediated the relationship between FA of dACC‐rVS pathway and the Lack of control and Excessive use subscales of IAT. These results indicate that the dACC‐rVS pathway serves as the common substrate of self‐control and internet addiction and further provide novel insights to the role of the dACC‐rVS pathway in the internet addiction.

4.1. dACC‐rVS pathway as the common substrate underlying self‐control and internet addiction

Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that dACC plays an important role in the addiction development in both substance use disorder and behavioural addiction. 12 , 18 The current study extended previous findings by providing structural evidence. The brain's structure shapes how neural dynamics unfold, thereby influencing the cognitive functions of human beings. 49 The explanation of changes in grey matter volume is complex. During brain maturation, the overall volume of grey matter decreases after the age of 6, 50 , 51 , 52 and this phenomenon could be explained by the selective‐elimination hypothesis, which assumes that the neuronal activity could tunes the molecular structure of individual synapses and eliminates those being initially overproduced, that is, those with unused or weak synaptic connections. 53 Alongside developmental procedure, the experience could also influence the grey matter volume. For example, both increased and decreased grey matter volumes have been found after cognitive training in children and adults. 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 In addition, decreased grey matter volume was consistently reported in addiction population. 21 The current study has found that as the severity of internet addiction increases, the grey matter volume of the dACC decreases in individuals. It could be speculated that when individuals remain immersed in the internet, the self‐control procedure could hardly be initiated to prevent individuals from spending more time in the internet, and consequently, the synapses underlying the self‐control would be selectively eliminated because of disuse. This is consistent with previous human and animal research demonstrating that functional connectivity between prelimbic/dACC and VS significantly decreased in drug/cocaine addiction. 18 , 19 The negative correlation between FA of dACC‐rVS pathway and severity of internet addiction indicated the white matter pathway between dACC and VS serves as the structural substrates underlying this functional deficit. Moreover, the positive correlation between FA of dACC‐rVS pathway and self‐control further support the speculation that the internet addicts may have difficulty adequately engaging the dACC region, resulting in a failure to adapt behaviour properly when faced with negative consequences during internet using.

4.2. The laterality of dACC‐VS pathway in addiction

Although dysregulated frontostriatal circuit in addiction was consistently discussed, the functional laterality of frontostriatal circuits in addiction development was rarely mentioned. VS is a typical region that is related to the representation of reward, as well as motivation, 65 , 66 and receives projections from areas within cognitive control network anatomically. A previous large‐scale study found that right, but not left, nucleus accumbens (NAcc) had smaller grey matter volume in alcohol‐dependent participants compared with nondependent controls 67 and a reduced rightward asymmetry of NAcc in substance‐dependent participants, 68 indicating the right VS was more closely associated with addiction. The hemispheric asymmetries in striatal function have also been reported in previous approach‐avoidance learning studies. Patients with Parkinson's disease, who have a relatively greater dopamine (DA) deficit in the left hemisphere showed greater approach deficit (less effort to increase gain than to avoid loss), whereas those with greater DA deficit in the right hemisphere showed greater avoidance deficit (less effort to avoid loss than to increase gain). 69 Another study found that participants with increased reward response in the left (versus right) NAcc displayed better approach learning and better encoding of positive prediction errors (PEs), and those displaying higher reward response in the right NAcc displayed better avoidance learning, indicating that left VS was more involved in approach motivation, whereas the right VS was more involved in avoidance motivation. 70 This approach‐avoidance bias was also found closely related with addictive behaviour. For example, relative to light drinkers, the heavy drinkers displayed a faster response when asked to move a computer manikin towards alcohol‐related pictures compared with moving it away from alcohol‐related pictures. 71 In abstaining alcohol‐dependent patients, a relative avoidance bias (faster response towards alcohol‐unrelated pictures) rather than relative approach bias (faster response towards alcohol‐related pictures) was found, and relapse rates increased as the relative tendency to avoid alcohol grew. 72 These results indicated that the approach‐avoidance bias was closely associated with addiction, and would dynamically change during the different phases of addiction, and asymmetries in striatal function may serve as the potential neural substrates. Consistent with our previous finding, which displayed that only functional connectivity between rVS and dACC was negatively correlated with individuals' severity of internet gaming disorder, 12 we found that only white matter characteristics of dACC‐rVS pathway correlated with individual's self‐control and internet addiction severity in the current study. This result indicates that the interplay between self‐control and avoidance procedure may play a dominant role in the internet addiction development. Medium spiny neurons (MSNs) are the most common cell type in the striatum, and the input to the MSNs from cortical are mainly glutamatergic and excitatory. 73 The lower integrity of the dACC‐rVS pathway may suggest a decrease in excitatory input from the dACC to the rVS, resulting in dysregulation of avoidance motivation. This argument is supported by the finding that the grey matter volume of the dACC is positively correlated only with the white matter integrity of the dACC‐rVS pathway, indicating that the selective elimination of synapses in the dACC has a more pronounced effect on modulating the right VS. Nevertheless, the impact of white matter integrity deficits on approach‐avoidance bias and the precise relationship between approach‐avoidance bias and internet addiction require further investigation.

4.3. The mediation role of self‐control in the relationship between white matter integrity of dACC‐rVS pathway and internet addiction severity

The significant complete mediation role of self‐control in the relationship between white matter integrity of dACC‐rVS pathway and IAT scores suggests that the individual differences in brain structure could predict the severity of internet addiction through the mechanism of self‐control. This outcome offers insight into how brain structure influences an individual's internet usage behaviour. As discussed above, further analysis on subscales revealed that white matter integrity of dACC‐rVS pathway could predict the excessive internet use and lack of control, with appropriate entertainment as mediator. The inability to effectively control one's entertainment behaviour may result in a loss of control over internet usage and lead to excessive use, with the underlying structural basis possibly involving compromised pathway between dACC and rVS. These results further emphasize the significance of dACC‐rVS pathway in understanding internet addiction and suggest that interventions targeting this pathway, such as neuromodulation therapies, combined with cognitive training aimed at enhancing one's self‐control, could be beneficial for individuals struggling with internet addiction.

5. CONCLUSION

Our results reveal that the grey matter volume of dACC was significantly negatively correlated with internet addiction severity, and white matter integrity of dACC‐rVS pathway (but not the dACC‐lVS pathway) is significantly associated with self‐control and the severity of internet addiction symptoms, with self‐control serving as a mediator. These results suggest that the dACC‐rVS pathway plays a pivotal role in the cognitive control mechanisms that govern internet usage behaviours. Importantly, these findings offer a promising direction for the development of prevention and therapeutic strategies. By targeting this specific brain circuit, interventions could potentially be designed to enhance self‐regulatory processes and reduce the possibility of developing internet addiction. In short, this study provides valuable insights into the neuropsychological mechanisms of addiction and suggests a potential target in developing effective interventions for addictive disorders. Given that only a small proportion of participants (17 out of 96) had DSM scores exceeding 5, caution should be exercised when generalizing these findings to the broader internet addiction population. Additionally, it is important to note that this study was not preregistered, and therefore, the results should be considered exploratory.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors report no financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the Ethic Committee of Zhejiang University. Written informed consent was obtained from all individuals prior to study enrolment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81971245, 62077042), the STI 2030—Major Projects (no. 2021ZD0200409), the MOE Frontiers Science Center for Brain Science & Brain‐Machine Integration, Zhejiang University, the Zhejiang Province “Qianjiang Talent Program,” Research of Basic Discipline for the 2.0 Base of Top‐notch Students Training Program, and the Ministry of Education of China (20211033).

Zhou H, Gong L, Su C, et al. White matter integrity of right frontostriatal circuit predicts internet addiction severity among internet gamers. Addiction Biology. 2024;29(5):e13399. doi: 10.1111/adb.13399

Contributor Information

Fengji Geng, Email: gengf@zju.edu.cn.

Yuzheng Hu, Email: huyuzheng@zju.edu.cn.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Due to privacy concerns, the data used in this article can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Young KS. Internet addiction: the emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;1:237. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Servidio R. Exploring the effects of demographic factors, internet usage and personality traits on Internet addiction in a sample of Italian university students. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;35:85‐92. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dong G, Potenza MN. A cognitive‐behavioral model of Internet gaming disorder: theoretical underpinnings and clinical implications. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;58:7‐11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rumpf H‐J, Achab S, Billieux J, et al. Including gaming disorder in the ICD‐11: the need to do so from a clinical and public health perspective: commentary on: a weak scientific basis for gaming disorder: let us err on the side of caution (van Rooij et al., 2018). J Behav Addict. 2018;7(3):556‐561. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wei L, Zhang S, Turel O, Bechara A, He Q. A tripartite neurocognitive model of internet gaming disorder. Front Psychol. 2017;8:285. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lebni JY, Toghroli R, Abbas J, et al. A study of internet addiction and its effects on mental health: a study based on Iranian University students. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ioannidis K, Hook R, Goudriaan AE, et al. Cognitive deficits in problematic internet use: meta‐analysis of 40 studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2019;215(5):639‐646. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2019.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li C, Dang J, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Guo J. Internet addiction among Chinese adolescents: the effect of parental behavior and self‐control. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;41:1‐7. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yuan K, Yu D, Cai C, et al. Frontostriatal circuits, resting state functional connectivity and cognitive control in internet gaming disorder. Addict Biol. 2017;22(3):813‐822. doi: 10.1111/adb.12348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li S, Ren P, Chiu MM, Wang C, Lei H. The relationship between self‐control and internet addiction among students: a meta‐analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:735755. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.735755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim EJ, Namkoong K, Ku T, Kim SJ. The relationship between online game addiction and aggression, self‐control and narcissistic personality traits. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23(3):212‐218. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gong L, Zhou H, Su C, et al. Self‐control impacts symptoms defining Internet gaming disorder through dorsal anterior cingulate–ventral striatal pathway. Addict Biol. 2022;27(5):e13210. doi: 10.1111/adb.13210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. WHO . ICD‐11 for mortality and morbidity statistics, 2018.

- 14. Tang Y‐Y, Tang R, Posner MI. Mindfulness meditation improves emotion regulation and reduces drug abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;163:S13‐S18. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tang YY, Posner MI, Rothbart MK, Volkow ND. Circuitry of self‐control and its role in reducing addiction. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015;19(8):439‐444. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Luo X, Zhang S, Hu S, et al. Error processing and gender‐shared and ‐specific neural predictors of relapse in cocaine dependence. Brain. 2013;136(4):1231‐1244. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Connolly CG, Foxe JJ, Nierenberg J, Shpaner M, Garavan H. The neurobiology of cognitive control in successful cocaine abstinence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;121(1‐2):45‐53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hu Y, Salmeron BJ, Gu H, Stein EA, Yang Y. Impaired functional connectivity within and between frontostriatal circuits and its association with compulsive drug use and trait impulsivity in cocaine addiction. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(6):584‐592. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hu Y, Salmeron BJ, Krasnova IN, et al. Compulsive drug use is associated with imbalance of orbitofrontal‐ and prelimbic‐striatal circuits in punishment‐resistant individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(18):9066‐9071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1819978116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Why voxel‐based morphometry should be used. Neuroimage. 2001;14(6):1238‐1243. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang M, Gao X, Yang Z, et al. Shared gray matter alterations in subtypes of addiction: a voxel‐wise meta‐analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2021;238(9):2365‐2379. doi: 10.1007/s00213-021-05920-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gulani V, Sundgren PC. Diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. J Neuroophthalmol. 2006;26(1):51‐60. doi: 10.1097/01.wno.0000205978.86281.3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hampton WH, Hanik IM, Olson IR. Substance abuse and white matter: findings, limitations, and future of diffusion tensor imaging research. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;197:288‐298. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jensen GB, Pakkenberg B. Do alcoholics drink their neurons away? Lancet. 1993;342(8881):1201‐1204. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92185-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McQueeny T, Schweinsburg BC, Schweinsburg AD, et al. Altered white matter integrity in adolescent binge drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(7):1278‐1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00953.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thayer RE, Callahan TJ, Weiland BJ, Hutchison KE, Bryan AD. Associations between fractional anisotropy and problematic alcohol use in juvenile justice‐involved adolescents. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2013;39(6):365‐371. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.834909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jannati A, Oberman LM, Rotenberg A, Pascual‐Leone A. Assessing the mechanisms of brain plasticity by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2023;48(1):191‐208. doi: 10.1038/s41386-022-01453-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sasanguie D, Defever E, Van den Bussche E, Reynvoet B. The reliability of and the relation between non‐symbolic numerical distance effects in comparison, same‐different judgments and priming. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2011;136(1):73‐80. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Edwards MS, Edwards EJ, Lyvers M. Cognitive trait anxiety, stress and effort interact to predict inhibitory control. Cognit Emot. 2017;31(4):671‐686. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1152232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schroeder PA, Nuerk HC, Plewnia C. Prefrontal neuromodulation reverses spatial associations of non‐numerical sequences, but not numbers. Biol Psychol. 2017;128:39‐49. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2017.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. DemİR S. Comparison of normality tests in terms of sample sizes under different skewness and kurtosis coefficients. Int J Assess Tools Educ. 2022;9(2):397‐409. doi: 10.21449/ijate.1101295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim H‐Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dentist Endodont. 2013;38(1):52‐54. doi: 10.5395/rde.2013.38.1.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Widyanto L, McMurran M. The psychometric properties of the internet addiction test. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004;7(4):443‐450. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lai C‐M, Mak K‐K, Watanabe H, Ang RP, Pang JS, Ho RC. Psychometric properties of the internet addiction test in Chinese adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(7):794‐807. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tangney JP, Baumeister RF, Boone AL. High self‐control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. J Pers. 2004;72(2):271‐324. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tan S, Guo Y. Revision of self‐control scale for Chinese college students. Chin J Clin Psych. 2008;16:468‐470. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Petry NM, Rehbein F, Gentile DA, et al. An international consensus for assessing internet gaming disorder using the new DSM‐5 approach. Addiction. 2014;109(9):1399‐1406. doi: 10.1111/add.12457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. APA A. P. A . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The American Psychiatric Association; 2013. doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lei W, Liu K, Zeng Z, et al. The psychometric properties of the Chinese version internet gaming disorder scale. Addict Behav. 2020;106:106392. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang J, Zhou H, Geng F, Song X, Hu Y. Internet gaming disorder increases mind‐wandering in young adults. Front Psychol. 2020;11:619072. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.619072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13(3):595‐605. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700048017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Li X, Morgan PS, Ashburner J, Smith J, Rorden C. The first step for neuroimaging data analysis: DICOM to NIfTI conversion. J Neurosci Methods. 2016;264:47‐56. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Jenkinson M, et al. Characterization and propagation of uncertainty in diffusion‐weighted MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50(5):1077‐1088. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29(3):162‐173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pierpaoli C, Basser PJ. Toward a quantitative assessment of diffusion anisotropy. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36(6):893‐906. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim JH, Budde MD, Liang H‐F, et al. Detecting axon damage in spinal cord from a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21(3):626‐632. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Beaulieu C. The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system–a technical review. NMR Biomed. 2002;15(7‐8):435‐455. doi: 10.1002/nbm.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Song S‐K, Sun S‐W, Ramsbottom MJ, Chang C, Russell J, Cross AH. Dysmyelination revealed through MRI as increased radial (but unchanged axial) diffusion of water. Neuroimage. 2002;17(3):1429‐1436. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Honey CJ, Thivierge J‐P, Sporns O. Can structure predict function in the human brain? Neuroimage. 2010;52(3):766‐776. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gennatas ED, Avants BB, Wolf DH, et al. Age‐related effects and sex differences in gray matter density, volume, mass, and cortical thickness from childhood to young adulthood. J Neurosci. 2017;37(20):5065‐5073. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3550-16.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dong H‐M, Castellanos FX, Yang N, et al. Charting brain growth in tandem with brain templates at school age. Sci Bull. 2020;65(22):1924‐1934. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2020.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bethlehem RA, Seidlitz J, White SR, et al. Brain charts for the human lifespan. Nature. 2022;604(7906):525‐533. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04554-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Petanjek Z, Judaš M, Šimić G, et al. Extraordinary neoteny of synaptic spines in the human prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(32):13281‐13286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105108108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Krafnick AJ, Flowers DL, Napoliello EM, Eden GF. Gray matter volume changes following reading intervention in dyslexic children. Neuroimage. 2011;57(3):733‐741. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sterling C, Taub E, Davis D, et al. Structural neuroplastic change after constraint‐induced movement therapy in children with cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):e1664‐e1669. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lovden M, Wenger E, Martensson J, Lindenberger U, Backman L. Structural brain plasticity in adult learning and development. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(9):2296‐2310. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Colom R, Martínez K, Burgaleta M, et al. Gray matter volumetric changes with a challenging adaptive cognitive training program based on the dual n‐back task. Personal Individ Differ. 2016;98:127‐132. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.087 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Takeuchi H, Taki Y, Sassa Y, et al. Working memory training using mental calculation impacts regional gray matter of the frontal and parietal regions. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e23175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Scholz J, Niibori Y, Frankland PW, Lerch JP. Rotarod training in mice is associated with changes in brain structure observable with multimodal MRI. Neuroimage. 2015;107:182‐189. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Brooks S, Burch K, Maiorana S, et al. Psychological intervention with working memory training increases basal ganglia volume: a VBM study of inpatient treatment for methamphetamine use. NeuroImage: Clin. 2016;12:478‐491. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. James CE, Oechslin MS, Van De Ville D, Hauert C‐A, Descloux C, Lazeyras F. Musical training intensity yields opposite effects on grey matter density in cognitive versus sensorimotor networks. Brain Struct Funct. 2014;219(1):353‐366. doi: 10.1007/s00429-013-0504-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hänggi J, Koeneke S, Bezzola L, Jäncke L. Structural neuroplasticity in the sensorimotor network of professional female ballet dancers. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31(8):1196‐1206. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gotink RA, Vernooij MW, Ikram MA, et al. Meditation and yoga practice are associated with smaller right amygdala volume: the Rotterdam study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12(6):1631‐1639. doi: 10.1007/s11682-018-9826-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhou H, Yao Y, Geng F, Chen F, Hu Y. Right fusiform gray matter volume in children with long‐term abacus training positively correlates with arithmetic ability. Neuroscience. 2022;507:28‐35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2022.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. de la Fuente‐Fernández R, Phillips AG, Zamburlini M, et al. Dopamine release in human ventral striatum and expectation of reward. Behav Brain Res. 2002;136(2):359‐363. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(02)00130-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cardinal RN, Parkinson JA, Hall J, Everitt BJ. Emotion and motivation: the role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26(3):321‐352. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(02)00007-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mackey S, Allgaier N, Chaarani B, et al. Mega‐analysis of gray matter volume in substance dependence: general and substance‐specific regional effects. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(2):119‐128. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17040415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Cao Z, Ottino‐Gonzalez J, Cupertino RB, et al. Mapping cortical and subcortical asymmetries in substance dependence: findings from the ENIGMA Addiction Working Group. Addict Biol. 2021;26(5):e13010. doi: 10.1111/adb.13010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Porat O, Hassin‐Baer S, Cohen OS, Markus A, Tomer R. Asymmetric dopamine loss differentially affects effort to maximize gain or minimize loss. Cortex. 2014;51:82‐91. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2013.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Aberg KC, Doell KC, Schwartz S. Hemispheric asymmetries in striatal reward responses relate to approach‐avoidance learning and encoding of positive‐negative prediction errors in dopaminergic midbrain regions. J Neurosci. 2015;35(43):14491‐14500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1859-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Field M, Kiernan A, Eastwood B, Child R. Rapid approach responses to alcohol cues in heavy drinkers. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2008;39(3):209‐218. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Spruyt A, De Houwer J, Tibboel H, et al. On the predictive validity of automatically activated approach/avoidance tendencies in abstaining alcohol‐dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;127(1‐3):81‐86. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Haber SN. Corticostriatal circuitry. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016;18(1):7‐21. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.1/shaber [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy concerns, the data used in this article can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author upon request.