Abstract

Aims

A mechanistic link between depression and risk of arrhythmias could be attributed to altered catecholamine metabolism in the heart. Monoamine oxidase-A (MAO-A), a key enzyme involved in catecholamine metabolism and longstanding antidepressant target, is highly expressed in the myocardium. The present study aimed to elucidate the functional significance and underlying mechanisms of cardiac MAO-A in arrhythmogenesis.

Methods and results

Analysis of the TriNetX database revealed that depressed patients treated with MAO inhibitors had a lower risk of arrhythmias compared with those treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. This effect was phenocopied in mice with cardiomyocyte-specific MAO-A deficiency (cMAO-Adef), which showed a significant reduction in both incidence and duration of catecholamine stress-induced ventricular tachycardia compared with wild-type mice. Additionally, cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes exhibited altered Ca2+ handling under catecholamine stimulation, with increased diastolic Ca2+ reuptake, reduced diastolic Ca2+ leak, and diminished systolic Ca2+ release. Mechanistically, cMAO-Adef hearts had reduced catecholamine levels under sympathetic stress, along with reduced levels of reactive oxygen species and protein carbonylation, leading to decreased oxidation of Type II PKA and CaMKII. These changes potentiated phospholamban (PLB) phosphorylation, thereby enhancing diastolic Ca2+ reuptake, while reducing ryanodine receptor 2 (RyR2) phosphorylation to decrease diastolic Ca2+ leak. Consequently, cMAO-Adef hearts exhibited lower diastolic Ca2+ levels and fewer arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves during sympathetic overstimulation.

Conclusion

Cardiac MAO-A inhibition exerts an anti-arrhythmic effect by enhancing diastolic Ca2+ handling under catecholamine stress.

Keywords: Monoamine oxidase, Ventricular arrhythmia, Calcium, Catecholamine, Oxidative damage, Calcium–calmodulin (CaM)-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), Protein kinase A (PKA)

Time for primary review: 40 days

1. Introduction

Depression is a major global health issue, affecting more than 280 million people, or 5% of the global population.1 Despite significant investments in the development of new antidepressant medications, drugs that enhance neurotransmitter activity in the serotoninergic and catecholaminergic systems continue to be primary pharmacotherapies used in the treatment and management of depression. Given that increased catecholaminergic stress is a key pathogenic factor underlying arrhythmogenesis, it is essential to determine whether antidepressants affect the risk of potentially harmful heart rhythm abnormalities and the mechanisms which might be involved.

Monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors (MAOIs) have been commonly used for the treatment of depression since the 1950s and are still used today, albeit less frequently.2 MAOs are flavoenzymes located at the mitochondrial outer membrane that catalyze oxidative deamination of catecholamines and biogenic amines, producing aldehyde and hydrogen peroxide as by-products.3 MAO has two isoforms, MAO-A and MAO-B. Of interest, MAO-A is present in the myocardium of several species including humans and rodents. MAO-A principally (but not exclusively) breaks down serotonin, norepinephrine (NE), and epinephrine, all of which have significant pathophysiological implications in the heart. Catecholamines like epinephrine and NE are well-known triggers for arrhythmogenesis. As such, slowing their metabolism (e.g. via inhibiting MAO-A), may potentially increase the risk of arrhythmias. However, research has also shown that MAO-A is induced and becomes an important source of reactive oxygen (ROS) and carbonyl species (RCS) that contributes to the pathogenesis of heart failure, myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion injury, and diabetic cardiomyopathy.4–9 Furthermore, multiple kinases including PKA and CaMKII,10 which play crucial roles in regulating cardiac rhythm, are sensitive to redox regulation. In addition, it has been postulated that MAO-A can affect the availability of catecholamines as ligands for β-adrenergic receptors in different cellular compartments.11,12

Despite these reports, mechanisms by which cardiac MAO-A inhibition may prevent or mitigate arrhythmogenesis have yet to be determined. In the present study, we provide evidence that patients with clinical depression have a lower incidence of arrhythmic events when treated with MAOIs relative to those treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Using a mouse model of cardiomyocyte-specific MAO-A inhibition (cMAO-Adef), we demonstrate that mice deficient in cardiac MAO-A have reduced arrhythmic incidence and duration in response to in vivo catecholamine stress, which is associated with faster Ca2+ reuptake, lower diastolic Ca2+ levels and reduced diastolic Ca2+ leak. Biochemical assays point to reduced oxidation and phosphorylation of important Ca2+ regulatory proteins as the molecular basis of improved Ca2+ handling and reduced arrhythmogenesis in catecholamine-stimulated cMAO-Adef hearts. Together, our findings suggest a translational potential of cardiac-specific inhibition of MAO-A for the prevention and treatment of arrhythmias.

2. Methods

2.1. TriNetX study design and data analysis

The data used in this study were collected on 10 May 2022, from the TriNetX research network in the United States (Cambridge, MA, USA), which provided access to comprehensive electronic medical records from ∼105 million patients from 66 healthcare organizations (HCOs). TriNetX is compliant with all data privacy regulations applicable to the contributing HCOs including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Any patient-level data provided in a data set generated by the TriNetX platform only contains de-identified data as defined in Section §164.514(a) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Because this study used only de-identified patient records and did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, this study was exempted from Institutional Review Board approval.

2.1.1. Study population

The study population consisted of adults (age, 18–80) with a history of either depressive episode (ICD10CM:F32) or major depressive disorder, recurrent (ICD10CM:F33) as defined by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 10th Revision. Individuals within this study population prescribed with MAOIs or SSRIs were assigned to MAOI and SSRI groups, respectively. Individuals with a diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ICD10CM:F90) were excluded to reduce confounding risks.

2.1.2. Assessed outcomes

The outcome of interest in this study was the risk of adverse arrhythmic events, including atrial fibrillation and flutter (ICD10CM:I48) and other cardiac arrhythmias (ICD10CM:I49). Risk refers to the probability of occurrence of any arrhythmic event mentioned above, which is assessed through built-in analytical tools provided by the TriNetX platform.

2.2. Animals

MAO-A flox/flox (MAO-Af/f) with 129/Sv genetic background that was used for this study have been previously described.13 Mice expressing the Cre recombinase driven by the α-myosin heavy chain promoter (αMHC-CRE+/−)14 were bred with MAO-Af/f mice to generate experimental cohorts including homozygous cardiac-specific MAO-A deficient mice (cMAO-Adef, MAO-Af/f/CRE+) and wild-type controls (WT, MAO-Af/f/CRE−). Both male and female mice at 2–4 months old were randomized and used in this study. All animal procedures were approved by and performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Iowa and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.3. MAO-A activity assay

Cardiomyocyte MAO activity was assessed in 20 µg cell lysate using Amplex™ Red Monoamine Oxidase Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A12214) with p-tyramine as the substrate. MAO-A activity is identified as the rate sensitive to MAO-A-specific inhibitor clorgyline according to the manufacturer’s directions.

2.4. Electrocardiographic recording and induction of ventricular arrhythmias in anaesthetized mice

Mice were placed on a heating pad (37°C) and lightly anaesthetized with isoflurane (1–1.5%) in 100% O2 for the duration of the electrocardiograph (ECG) recording. Surface ECGs were recorded by PowerLab 8/35 (AD Instruments, Sydney, Australia). Baseline ECGs were recorded for 5 min when stable heart rates were reached, followed by an additional 30 min recording following intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration of epinephrine (2 mg/kg) and caffeine (120 mg/kg).15,16 Baseline parameters including heart rate, P-wave duration, PR-interval, QRS-interval, and QT-interval were obtained via the ECG analysis module of LabChart 8 (AD Instruments). Analysis of cardiac arrhythmias was performed manually. Definitions of ventricular arrhythmias were based on the Lambeth Conventions II.17 Both non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT; run of 4–10 consecutive single ventricular premature contraction, PVC) and sustained VT (run of 10 or more consecutive PVCs) were included in the calculation of VT incidence and duration. The duration of VT is calculated by the sum of the time of both non-sustained and sustained VT episodes. Mice were then euthanized by cervical dislocation with 5% isoflurane anaesthesia via a vaporizer.

2.5. Confocal Ca2+ imaging in intact mouse hearts

Excised hearts were loaded with Rhod-2 AM (rhodamine 2 acetoxymethyl ester; 5 µM, AAT Bioquest) in Krebs–Henseleit solution (120 mM NaCl, 24 mM NaHCO3, 11.1 mM glucose, 5.4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.42 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM taurine and 5 mM creatine, oxygenated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2) at room temperature for 40 min via a retrograde Langendorff perfusion system. Hearts were later transferred to another Langendorff apparatus (37°C) attached to the confocal microscope system after Rhod-2 AM loading was completed. To minimize motion artefacts during Ca2+ imaging, blebbistatin (5–10 μM) was added to the perfusion solution containing 1.8 mM CaCl2. In situ confocal line-scan imaging of Ca2+ signals arising from epicardial myocytes was performed and acquired at a rate of 3.07 ms/line. Ca2+ transients were recorded under electrical pacing at 5–50 Hz (by placing a platinum electrode onto the surface of the ventricle apex). Analysis of Ca2+ imaging data was performed offline using custom-compiled routines in IDL (Interactive Data Language) software, as previously described.18

2.6. Isolation of cardiomyocytes

Mouse ventricular myocytes were isolated via enzymatic digestion as previously described.19 Briefly, the hearts were quickly excised and perfused on a Langendorff apparatus at 37°C with normal Ca2+ free Tyrode’s solution (containing the following in mM: NaCl, 137; KCl, 5.4; MgCl2, 2.0; NaH2PO4, 0.33; D-glucose, 10.0; and HEPES (4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid, N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid), 10.0; pH 7.40 at 37°C). After ∼5 min of perfusion, the perfusate was switched to Tyrode’s solution containing Collagenase (Type 2, 1 mg/mL, Worthington) and protease (0.05 mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) for the digestion of the connective tissue. After ∼20 min of digestion, single ventricular myocytes were isolated from the dissected and triturated ventricles and stabilized in Tyrode’s solution containing bovine serum albumin (1%). After gradually reintroducing Ca2+, the final Ca2+ tolerant cardiomyocytes were resuspended in 1.8 mM Ca2+ Tyrode’s solution and maintained at room temperature.

2.7. Confocal Ca2+ imaging in single isolated cardiomyocytes

All Ca2+ imaging experiments were performed at 37°C. After isolation, myocytes were loaded with Rhod 2-AM (5 µM, AAT Bioquest) for 25 min at room temperature, followed by an additional 25 min of incubation in fresh Tyrode’s solution, to wash out excess dye and allowing the complete de-esterification of Rhod 2-AM. Myocytes were then seeded on a laminin-coated perfusion chamber, which is mounted on the inverted confocal microscope (ZEISS laser scanning microscope 510, Germany) equipped with a 63×, 1.4 NA oil immersion objective. Rhod 2-AM was excited with the 561 nm line laser and emission was collected by a 575-nm long pass filter. To assess Ca2+ dynamics in a single cardiomyocyte, myocytes were perfused with 1.8 mM Ca2+ Tyrode’s solution and paced using extracellular platinum electrodes at various frequencies (1, 3, 5 Hz). Ca2+ transients were recorded accordingly in the line-scan mode along the long axis for 2000 lines at a rate of 1.93 ms/line. To examine the effect of catecholamine stimulation on myocyte Ca2+ handling, the same procedures were carried out during perfusion with NE (1 µM). To assess the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ content, after recording Ca2+ transients under 1 Hz pacing as described above, electrical stimulation was stopped, and 20 mM caffeine was applied locally to rapidly induce total Ca2+ release from the SR. The caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient amplitude was used as an estimate of SR Ca2+ content. The time constants (Tau) of twitch and caffeine-induced Ca2+ transient decay were calculated from mono-exponential curve fitting, which reflects the contribution of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) and sodium–calcium exchanger (NCX) to diastolic Ca2+ removal, respectively.20,21 To assess Ca2+ spark activity, quiescent cardiomyocytes were recorded in the line-scan mode along the long axis for 1000 lines at a rate of 1.93 ms/line. Six consecutive recordings from one quiescent cardiomyocyte were used for Ca2+ spark analysis by a custom IDL programme as previously described.19

2.8. MitoSOX Red fluorescence recording in field-stimulated cardiomyocytes

Evaluation of mitochondrial ROS levels was performed using mitochondrial superoxide indicator MitoSOX Red as described earlier.22 Isolated cardiomyocytes were loaded with MitoSOX Red (3.3 µM, M36008, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature. After the staining procedure, myocytes were placed in the imaging chamber and perfused with Tyrode’s solution (contains 1.8 mM CaCl2), with or without NE (1 µM). Cardiomyocytes were then stimulated by electrical field pacing at 1 Hz for 1 min, which was then increased to 5 Hz for an additional 3 min. Images were captured at baseline, end of 1 Hz pacing, and after 3 Hz pacing, using a Zeiss Axiovert microscope equipped with a 40×, 1.2 NA, water immersion objective (λex = 380 nm, λem = 580 nm). The quantification of fluorescence intensity was analysed using ImageJ software (NIH).

2.9. Immunoblotting

For protein extraction, frozen heart tissues were collected in Precellys® Tissue Homogenizing Mixed Beads Kit (2.0 mL) and homogenized using a PRECELLYS homogenizer (Bertin) containing ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer (R0278, Sigma-Aldrich), supplemented with protease inhibitor mix (cOmplete, Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Roche). Solubilized heart homogenates were obtained by centrifugation at 13 200 rpm at 4°C for 30 min. The resulting supernatants were quantified for protein using a Bradford BioRad protein assay. The supernatant was mixed with Lithium dodecyl sulfate loading buffer and then resolved in a gradient NuPAGE gel (4–12%, Invitrogen). NuPAGE gel resolved proteins were transferred to PVDF (Polyvinylidene fluoride) membranes at 30 V overnight at 4°C. After blocking with Tris-buffered saline containing 0.5% Tween-20 and 5% non-fat milk powder, specific proteins were detected with anti-RyR2 (MA3-916, Sigma), anti-CaV1.2 (CACNA1C; ACC-003, Alomone Labs), anti-NaV1.5 (SCN5A; ASC-005, Alomone Labs), anti-Phospholemman (PLM, PA5-792881), anti-NCX1 (79350, Cell Signaling), SERCA2a (MA3-919, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-Calsequestrin (CSQ, PA1-913, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-RyR2 (pSer2814; A010-31AP, Badrilla), anti-RyR2 (pSer2030; A010-32, Badrilla), anti-RyR2 (pSer2808; A010-30, Badrilla), anti-CaMKII (phospho T286; ab32678, Abcam), anti-CaMKII (ab181052, Abcam), anti-ox-CaMKII (07-1387, sigma), anti-β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR; A-B2AR, Badrilla), anti-β1-adrenergic receptor (β1AR; ab3442, Abcam), PDE4D (PD4-401AP, FabGennix), GAPDH-HRP (MA5-15738-HRP, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-Phospholamban (PLB-pSer16; (A010-12, Badrilla), anti-Phospholamban (PLB-pThr17; A010-13, Badrilla), and anti-Phospholamban (PLB; A010-14, Badrilla) antibodies. Immunoblot analysis to assess the extent of PKA-RII and PKA-C disulphide formation was performed under non-reducing conditions and probed with anti-PKA-RIIα (612242, BD Transduction Laboratories) and anti-PKA-C (610980, BD Transduction Laboratories). All primary antibodies were revealed with HRP-conjugated goat secondary antibodies using the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP imaging systems and detected using SuperSignal™ West Pico or Femto Chemiluminescence Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Protein densitometry was analysed by Image Lab software (6.0).

2.10. OxyBlot analysis

To determine the degree of oxidative stress in mouse hearts following the epinephrine/caffeine challenge, the OxyBlot™ Protein Oxidation Detection Kit (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) was used to measure carbonyl groups (i.e. protein oxidation) in the myocardial lysates according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, myocardial tissue from WT and cMAO-Adef mice was rapidly dissected from mice 20 min after the epinephrine/caffeine challenge and flash frozen using clamps that were pre-cooled in liquid N2. Tissue samples (∼10 mg) were then lysed in ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer in the presence of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone (DNP-hydrazone) to derivatize the carbonyl groups. Following neutralization using the commercial reagent, samples were subjected to SDS–PAGE and transferred to the PVDF membrane as described above. Immunoblot procedure for the DNP-modified proteins was performed using primary and secondary antibodies provided by the manufacturer. Chemiluminescence was used in the final step after secondary antibody incubation and wash, using the iBright FL1500 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.11. Catecholamine measurement

After 30 min of administering a combination of epinephrine (2 mg/kg) and caffeine (120 mg/kg) or saline via i.p. injection, mouse heart tissue samples were harvested and homogenized in a saline solution containing 10 µM clorgyline. The lysate was spun at 3000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was removed for catecholamine measurement using QuickDetect™ Catecholamine ELISA Kit (E4462, BioVision) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.12. Statistics

All statistical analyses for the TriNetX study were completed on the TriNetX research platform. Potential confounding factors including patient characteristics (age, sex, and race/ethnicity) and comorbidities (diabetes, essential hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, and opioid use disorder) were considered in this study. Therefore, a 1:1 propensity score technique was used to match cohorts, mitigate the risk of bias, and obviate the need for covariate adjustments. The propensity score matching analysis was performed using a multivariable logistic regression model and nearest neighbour algorithms with a tolerance level of 0.01 and a difference between propensity scores ≤0.1.23 Risk difference (RD), risk ratio, and odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the arrhythmic outcome were calculated, and P < 0.05 indicates statistical significance between groups. Data obtained from animal models and related biochemistry studies are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical differences were determined by GraphPad Prism version 9.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The incidence of VT was compared using Fisher’s exact test. The VT duration was compared with the Mann–Whitney U test as the data were not normally distributed. For calcium measurements in isolated cardiomyocytes, analyses were performed in RStudio using the hierarchical statistical method described previously.24 Other normally distributed data were analysed by parametric tests: one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey post hoc for >2 groups or Student’s t-test for two groups. P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

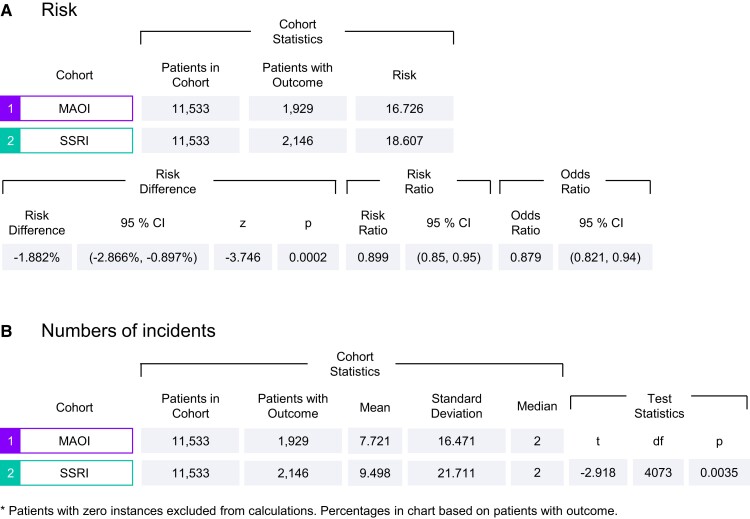

3.1. MAOI treatment is associated with a lower risk of arrhythmic events in adults with depression

Given the known association between depression and the risk of arrhythmias, we sought to determine whether arrhythmic events correlated with the class of antidepressant medication used by asking whether MAO-A activity correlates with arrhythmic outcomes. We conducted a retrospective matched cohort comparison of patients with depression, treated either with MAOIs or SSRIs utilizing the TriNetX database and analytics platform. 11 533 individuals were identified who were treated with MAOIs while 2 025 313 individuals were found to have been treated with SSRIs. The baseline characteristics of these two groups varied prior to matching. Specifically, the MAOI group had higher mean age, percentage of males, Caucasian ethnicity, prevalence of essential hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and more likely to be prescribed cardiovascular medications compared with the SSRI group. The MAOI group also had a decreased prevalence of opioid use-related disorders compared with the SSRI group (Table 1, before propensity score matching). To avoid these confounders, 1:1 propensity score matching was performed, using logistic regression to balance the groups.23 After matching, both groups were well-balanced for all clinical and demographic variables (Table 1, after propensity score matching). As shown in Figure 1A, 1929 individuals encountered arrhythmic events among the MAOI group (16.726%, n = 11 533) compared with 2146 individuals among the SSRI group (18.607%, n = 11 533). The MAOI group also had a significantly lower risk (RD: −1.882%; 95% CI: −2.866%, −0.897, P = 0.0002) of developing arrhythmic events as well as fewer incidences of arrhythmia (mean: 7.721 vs. 9.498, P = 0.0035, Figure 1B) compared with individuals treated with SSRIs.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (demographics and health) n (%) of patients with depression treated with MAOi or SSRI before and after propensity score matchinga

| MAOi group (n = 11,533) | SSRI group (n = 2,025,313) | P value | MAOi group (n = 11,533) | SSRI group (n = 11,533) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before propensity score matching | After propensity score matching | |||||

| Age, mean ± SD | 63.6 ± 13.5 | 51 ± 17.2 | <0.0001 | 63.6 ± 13.5 | 63.6 ± 13.5 | 0.9511 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male, | 5,723 (49.627) | 612,085 (30.222) | <0.0001 | 5,723 (49.627) | 5,736 (49.74) | 0.8641 |

| Female | 5,809 (50.373) | 1,412,796 (69.757) | <0.0001 | 5,809 (50.373) | 5,796 (50.26) | 0.8641 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 478 (4.145) | 167,750 (8.283) | <0.0001 | 478 (4.145) | 491 (4.258) | 0.6696 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 8,892 (77.107) | 1,410,754 (69.656) | <0.0001 | 8,892 (77.107) | 8,890 (77.09) | 0.9750 |

| Black or African American | 506 (4.388) | 241,335 (11.916) | <0.0001 | 506 (4.388) | 506 (4.388) | 1.0000 |

| Diagnoses, n (%) | ||||||

| Essential hypertension | 4,132 (35.831) | 625,024 (30.861) | <0.0001 | 4,132 (35.831) | 4,134 (35.848) | 0.9781 |

| Disorders of lipoprotein metabolism | 3,492 (30.281) | 504,799 (24.924) | <0.0001 | 3,492 (30.281) | 3,490 (30.264) | 0.9771 |

| Opioid-related disorders | 226 (1.960) | 48,325 (2.386) | 0.0028 | 226 (1.960) | 238 (2.064) | 0.5736 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1,775 (15.392) | 301,880 (14.905) | 0.1435 | 1,775 (15.392) | 1,742 (15.106) | 0.5455 |

| Alcohol-related disorders | 694 (6.018) | 115,019 (5.679) | 0.1169 | 694 (6.018) | 690 (5.983) | 0.9117 |

| Cardiovascular medicationsb | 7,886 (68.384) | 1,037,504 (51.227) | <0.0001 | 7,886 (68.384) | 7,877 (68.306) | 0.8986 |

aThe 1:1 propensity score matching technique was performed using a multivariable logistic regression model to balance the baseline characteristics of the population.

bCardiovascular medications include beta-blockers, antiarrhythmics, diuretics, lipid lowering agents, antianginals, calcium channel blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

Figure 1.

TriNetX analysis of arrhythmia risk among adult patients with depression prescribed either MAOIs or SSRI.

These data suggest MAOIs may lower the risk of cardiac arrhythmic outcomes in patients with depression relative to those treated with SSRIs.

3.2. Mice with cardiac MAO-A deficiency are protected from catecholamine-induced ventricular tarchycardia

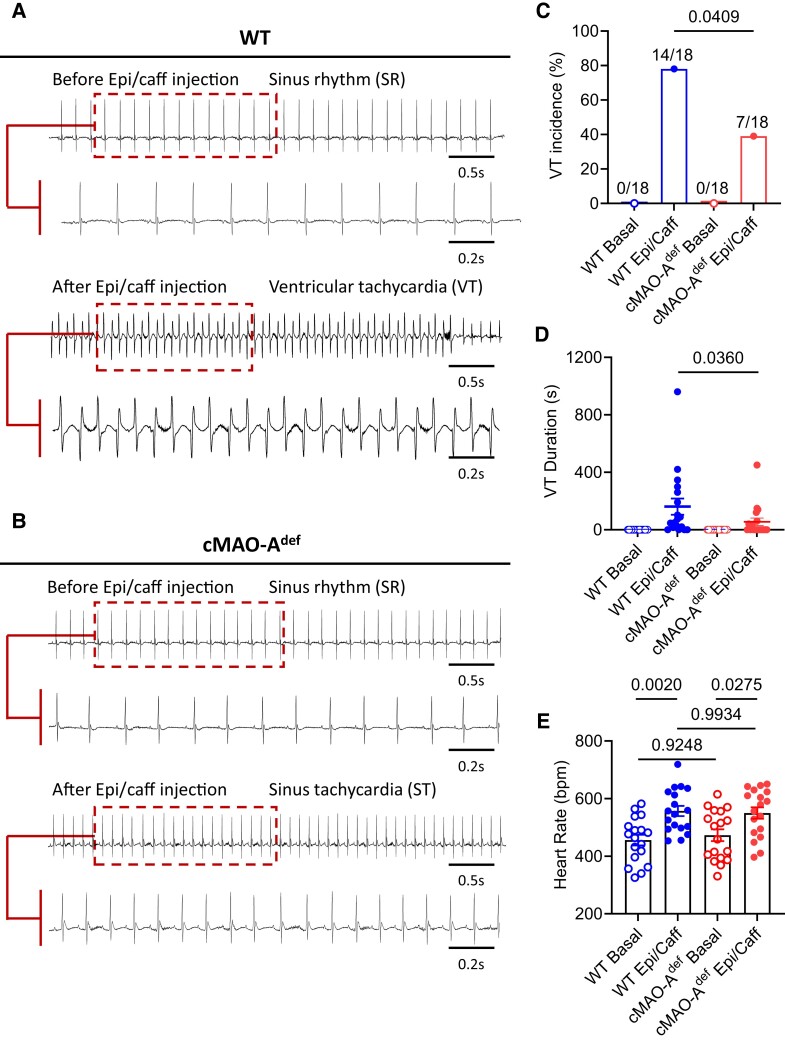

Both MAO-A and MAO-B isoforms are expressed in various tissues throughout the body. While both isoforms are present in human cardiomyocytes, MAO-A appears to be the predominant form.25,26 To study the relationship between cardiac MAO-A and arrhythmogenesis, we first used an αMHC promoter-driven Cre-LoxP system to selectively disrupt the Maoa gene in cardiomyocytes (cMAO-Adef). Enzyme activity assays confirmed that MAO-A activity was reduced by >50% in isolated cardiomyocytes (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1A); consequently, catecholamine levels were significantly increased in cMAO-Adef hearts compared with WT hearts at baseline (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1B). Next, we sought to determine the susceptibility of cMAO-Adef mice to VT. To this end, we used a combination of epinephrine (2 mg/kg) and caffeine (120 mg/kg) challenge, which is known to effectively induce arrhythmias including VT in rodent models, particularly in mice with ryanodine receptor (RyR) mutations.18,27–29 However, the susceptibility of mice to arrhythmias can also be influenced by their genetic background, with some strains being more sensitive to sympathetic stimulation than others.30,31 Indeed, while both wild-type (WT) and cMAO-Adef mice showed no arrhythmias or conduction disorders in unstressed conditions, a variety of arrhythmic events were observed in both groups after catecholamine/caffeine stimulation (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2), including single ventricular premature contraction (PVC, Supplementary material online, Figure S2A and B), couplet-PVCs (PVC, Supplementary material online, Figure S2C) and VT (>4 consecutive PVCs, Supplementary material online, Figure S2D–F). We observed that epinephrine and caffeine challenge was able to induce VT (including both non-sustained and sustained VT) in most cMAO-A WT mice (14 of 18 animals, 78%, Figure 2A and C). However, catecholamine stress-induced VT incidence was significantly lower in cMAO-Adef mice (7 of 18 mice, 39%, P = 0.0409, Figure 2B and C). The total duration of VT was also significantly shorter in cMAO-Adef mice compared with WT mice (Figure 2D, 55.33 ± 26.21 vs. 163.1 ± 56.38 s, P = 0.0360). There were no significant differences in heart rate or conduction intervals between WT and cMAO-Adef mice at rest or after 30 min catecholamine stimulation (Figure 2E and Supplementary material online, Figure S3A–H). However, cMAO-Adef mice had slightly longer QRS intervals at rest (see Supplementary material online, Figure S3D), which may be due to slightly increased heart weight (see Supplementary material online, Figure S4B).

Figure 2.

Cardiac MAO-A deficiency blunts susceptibility to catecholamine-induced VT in vivo. Representative surface ECG traces obtained from anaesthetized WT (A) and cMAO-Adef (B) mice before (basal) and after the injection of caffeine (120 mg/kg) and epinephrine (2 mg/kg) to induce VTs. During the 30 min period of ECG recordings following injection, VT incidence (%) (C), VT duration (s) (D) and heart rate (b.p.m.) (E) was determined and compared with basal levels of these parameters, in WT or cMAO-Adef mice (C–E, N = 18 mice per genotype). Data are represented as mean ± SEM in (D and E). Data are analysed by Fisher’s exact test in (C), Mann–Whitney test in (D), paired t-test in (E) for comparison in the same genotype; unpaired t-test for comparison between genotypes. P-values of comparisons are shown in the graph.

Together, these findings suggest that inhibiting cardiac MAO-A reduces the heart’s susceptibility to catecholamine stress-induced VT in vivo.

3.3. Cardiac MAO-A inhibition enhances diastolic Ca2+ kinetics in the whole heart

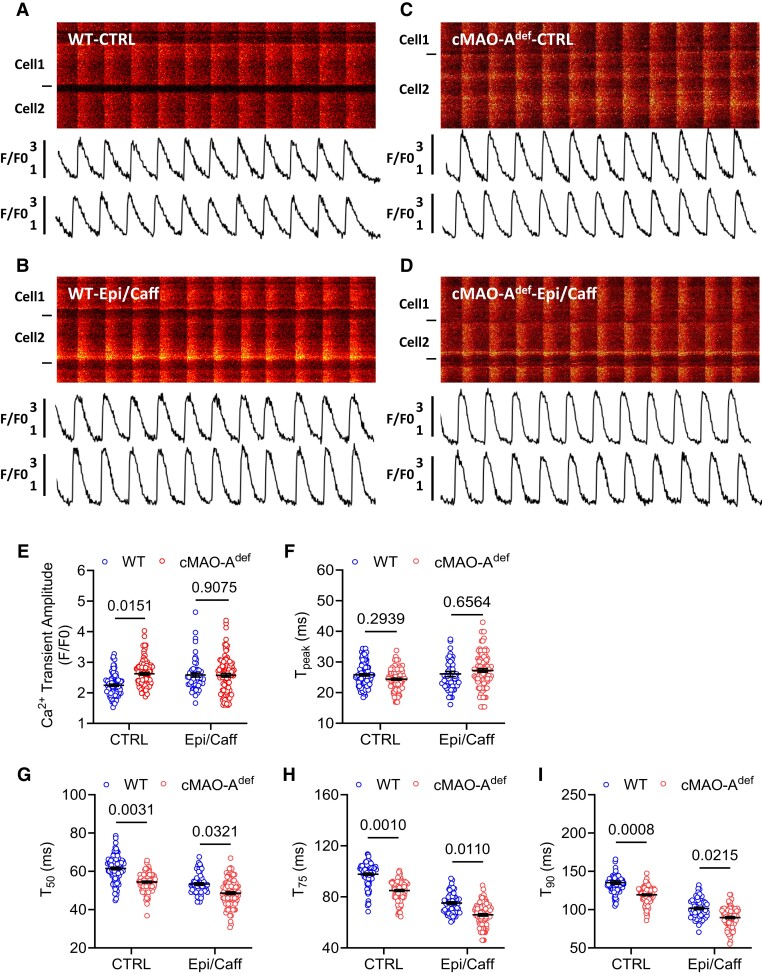

Imbalanced cellular Ca2+ homeostasis underlines arrhythmogenesis.32,33 Our in vivo findings that cardiac MAO-A inhibition suppresses catecholamine-induced VT in vivo suggests that cardiac MAO-A may affect intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. To this end, we first performed in situ Ca2+ imaging of ventricular cardiomyocytes from intact mouse hearts attached to an oxygenated Langendorff perfusion system.18 We examined Ca2+ signals initiated by 5 Hz external electric stimulation. At baseline, cardiomyocytes from both WT and cMAO-Adef hearts displayed uniform, synchronized Ca2+ transients (Figure 3A and C). Compared with WT, cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes showed higher Ca2+ transient amplitudes (Figure 3E) as well as faster Ca2+ decay kinetics (Figure 3G–I), indicating cardiac MAO-A inhibition is associated with accelerated basal Ca2+ kinetics.

Figure 3.

Catecholamine stimulation leads to altered in situ Ca2+ dynamics in cMAO-Adef hearts with 5 Hz pacing. Representative confocal microscopy images of in situ Ca2+ dynamics driven by 5 Hz electrical stimulation are shown in WT (A and B) and cMAO-Adef (C and D) intact hearts at baseline (A and C) and under caffeine (120 µg/mL) and epinephrine (2 μg/mL) perfusion (B and D). The Ca2+ transient amplitude (E), time to peak (Tpeak, F), and decay T50, (G); T75, (H); T90, (I) are also shown. (N = 69–105 cells from 4 to 5 hearts/genotype for each group). Cell boundaries were indicated by the black bars on the left. The F/F0 traces depict the average fluorescence signal of the scan area. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Data are analysed by hierarchical statistical tests for comparison between genotypes. P-values of comparisons are shown in the graph.

To understand Ca2+ performance in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes under catecholamine stress, we next perfused 5 Hz stimulated hearts with epinephrine (2 μg/mL) and caffeine (120 µg/mL; Figure 3B and D). Ca2+ transient decay kinetics of cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes (mainly reflecting SR Ca2+ uptake) were further accelerated beyond those achieved in WT cells (Figure 3G–I), but without a further increase in Ca2+ transient amplitude (Figure 3E). Moreover, under Epi/Caff stimulation, cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes showed a reduced propensity for abnormal triggered Ca2+ activity at higher pacing frequency (50 Hz; as indicated by Ca2+ waves upon cessation of pacing, Supplementary material online, Figure S5A–C), compared with WT cells. Sustained catecholamine stimulation under high frequency (50 Hz) stimulation caused aberrant conduction and Ca2+ transients in WT hearts (see Supplementary material online, Figure S6A). In contrast, cMAO-Adef hearts maintained regular electrical patterns and Ca2+ dynamics (see Supplementary material online, Figure S6B).

Together, these data suggest that catecholamine stress-induced Ca2+ homeostasis and arrhythmias are sensitive to the level of MAO-A activity in the heart.

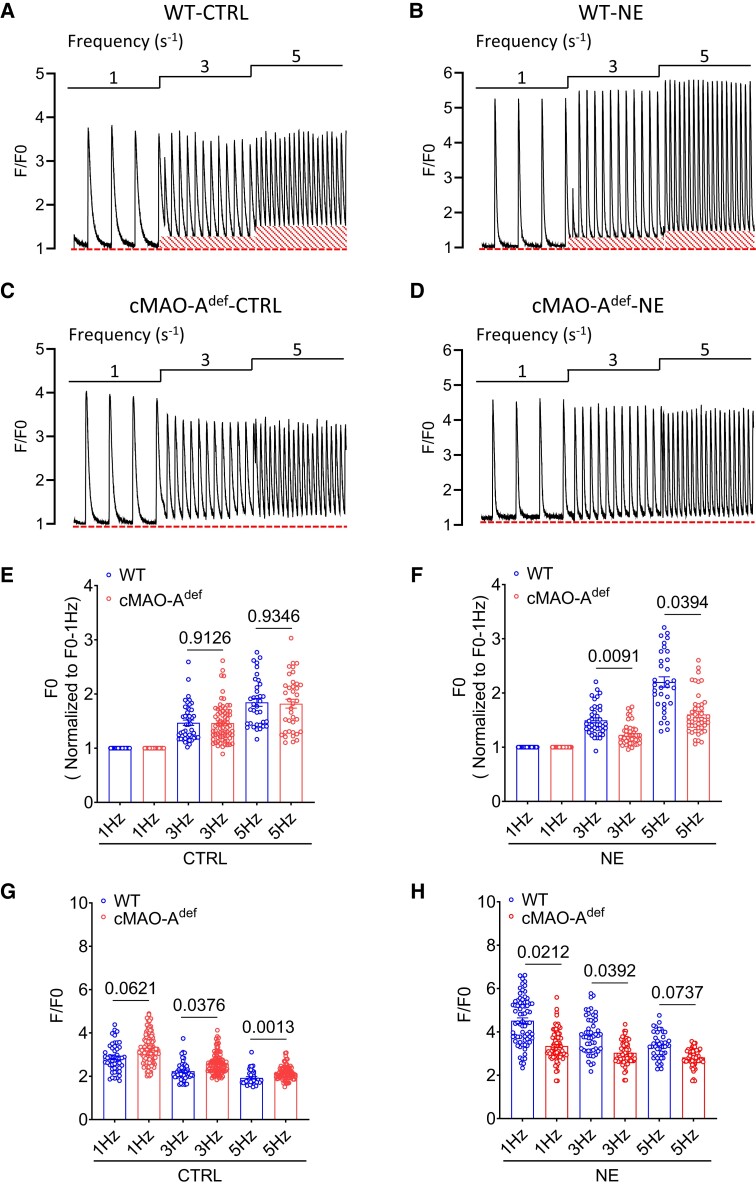

3.4. Cardiac MAO-A inhibition improves diastolic Ca2+ control under catecholamine stimulation in single cardiomyocytes

Change in the decay rate of Ca2+ transient is likely to affect end diastolic Ca2+ concentration.34 The faster Ca2+ decay kinetics observed in the cardiac MAO-Adef hearts therefore suggest lower diastolic Ca2+ levels. To this end, intracellular Ca2+ measurements were performed in isolated cardiomyocytes during field stimulation at three different electric frequencies (1, 3, and 5 Hz). Cardiomyocytes from both WT and of cMAO-Adef hearts showed pacing-induced increase in diastolic Ca2+ levels in a frequency-dependent manner at baseline (Figure 4A and C) and under catecholamine stimulation (Figure 4B and D, NE). However, the frequency-dependent increase in diastolic Ca2+ levels was markedly decreased in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes in response to NE compared with WT cardiomyocytes (Figure 4E and F). Notably, similar to the in situ Ca2+ imaging experiments conducted on intact hearts (Figure 3E), the amplitude of twitch-induced Ca2+ transients in isolated cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes was higher at baseline compared with WT cells (Figure 4G). However, when stimulated with 1 μM NE, the amplitude of twitch-induced Ca2+ transients was comparatively lower in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes (Figure 4H).

Figure 4.

cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes have lower diastolic Ca2+ level after catecholamine stimulation. Representative Ca2+ transient tracings obtained during three different electrical pacing frequencies at basal or under NE (1 μM) stimulation in a single cardiomyocyte isolated from WT (A and B) and cMAO-Adef (C and D) mouse hearts are shown highlighting the increased diastolic Ca2+ (outlined baseline segment) at higher pacing frequencies in the WT cardiomyocytes. Normalized diastolic Ca2+ levels (F0) and systolic Ca2+ release (F/F0) of WT and cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes at baseline (E and G) and under NE treatment (F and H) are also shown. (n = 35–119 cells from 5–7 hearts/genotype for each group). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Data are analysed by hierarchical statistical tests for comparison between genotypes. P-values of comparisons are shown in the graph.

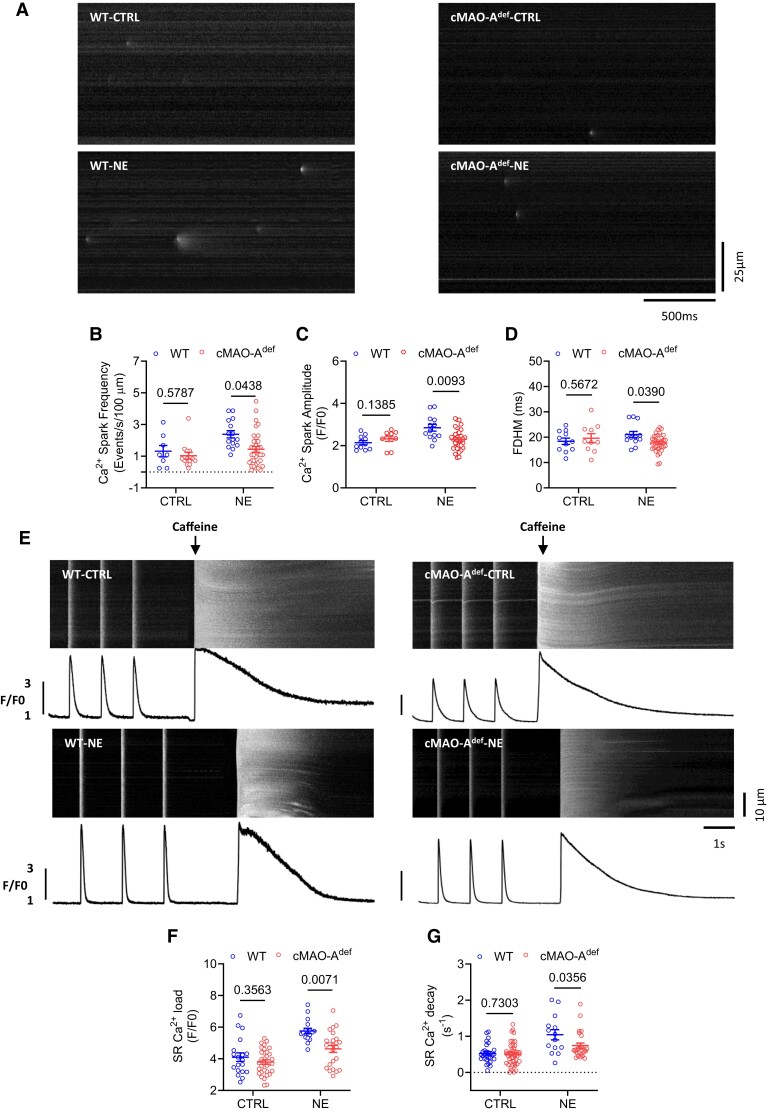

At the single cardiomyocyte level, studies have shown that higher diastolic Ca2+ levels could arise from increased diastolic SR Ca2+ leak which in turn activates NCX leading to delayed afterdepolarizations and the triggering of VT.35 Increased sympathetic drive is known to amplify diastolic SR Ca2+ leak which can be reflected in increased Ca2+ spark activity.36,37 In response to catecholamine stimulation, cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes had lower diastolic Ca2+ levels, suggesting that cardiac MAO-A inhibition may suppress Ca2+ spark activities. To this end, we measured Ca2+ sparks in quiescent cardiomyocytes isolated from WT and cMAO-Adef hearts. At baseline, the parameters of Ca2+ spark characteristics were comparable between genotypes, including frequency, amplitude, and full duration at half-maximum (FDHM; Figure 5A–D). However, in the presence of 1 μM NE, Ca2+ spark frequency, amplitude, and FDHM were significantly lower in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes than WT (Figure 5B–D), suggesting lower Ca2+ spark activities in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes under NE stimulation.

Figure 5.

Decreased Ca2+ spark activity and reduced SR Ca2+ content after catecholamine stimulation in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes. Shown in (A) are representative Ca2+ spark images in cardiomyocytes from WT and cMAO-Adef mice at baseline or under NE (1 μM) stimulation. The frequency (B), amplitude (C), FDHM (D) of Ca2+ sparks are also shown. (n = 7–36 cells from 4 to 5 hearts/genotype per group). SR Ca2+ content was measured by rapid caffeine application induced Ca2+ release. Shown in (E) are representative traces of 1 Hz field stimulation-triggered Ca2+ transients and caffeine-induced Ca2+ release (SR Ca2+ content) from WT and cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes at basal or under NE stimulation. The amplitudes (F) and decay (G) of caffeine-induced SR Ca2+ transients are shown (n = 17–44 cells from 4 to 5 hearts/genotype for each group). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Data are analysed by hierarchical statistical test between genotypes. P-values of comparisons are shown in the graph. FDHM, mean duration at half-peak amplitude; FWHM, full width at half-maximum.

Ca2+ sparks are the elementary events of Ca2+ release from the SR,38 and are affected by the SR Ca2+ load.39,40 We therefore tested whether SR Ca2+ content (SR Ca2+ load) is altered by measuring the rise in the Ca2+ transient induced by rapid application of 20 mmol/L caffeine (Figure 5E). At baseline, SR Ca2+ load was comparable between both genotypes (Figure 5F). In the presence of 1 μM NE, however, SR Ca2+ content was significantly lower in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes compared with those isolated from WT hearts (Figure 5F). This reduction aligns with the observed decrease in the amplitude of twitch-induced Ca2+ transients during NE stimulation (Figure 4H), considering the well-established steep relationship between SR Ca2+ content and fractional release.41 Meanwhile, cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes also showed a slower decay rate of caffeine-induced Ca2+ transients under NE stimulation, suggesting Ca2+ extrusion via the NCX is slower in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes (Figure 5G). Given that NCX activity has a linear relationship with intracellular Ca2+ concentration,42 slower NCX activity under NE stimulation would be consistent with smaller Ca2+ transients observed in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes (Figure 4H).

Collectively, these data suggest that cardiac MAO-A inhibition is associated with enhanced diastolic Ca2+ control in single cardiomyocytes and favours less irregular Ca2+ events under catecholamine stress.

3.5. Cardiac MAO-A inhibition alters the phosphorylation of important Ca2+ handling proteins in response to catecholamine stimulation

We next sought to investigate the molecular determinants of altered Ca2+ handling in cardiac MAO-A deficient hearts. Hearts from WT and cMAO-Adef mice that underwent baseline recording and catecholamine stress experiments were processed for Western blot studies. First, we inspected expression levels of proteins involving β-adrenergic signalling (a major catecholamine target pathway) and Ca2+ handling pathways and observed no significant differences in the protein abundance of β1AR, β2AR, PDE4D, CaV1.2, NaV1.5, NCX1, PLM, SERCA2a and CSQ between WT and cMAO-Adef hearts at baseline (see Supplementary material online, Figure S7).

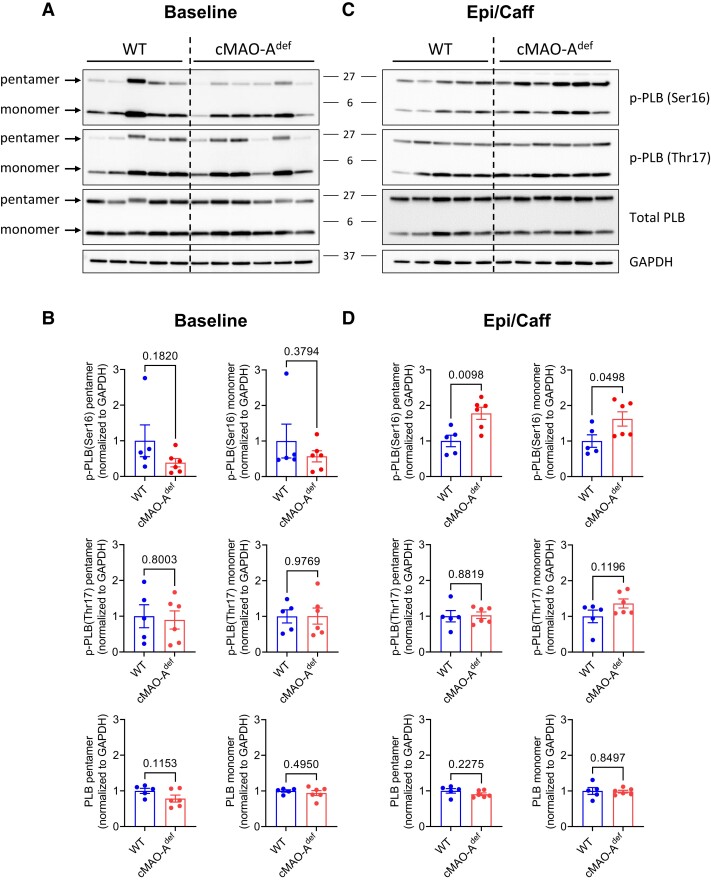

SR Ca2+ reuptake rate is known to be mainly regulated by the SR Ca2+ pump SERCA2 and its endogenous inhibitor phospholamban (PLB) during diastole,43,44 and their regulation could explain the accelerated Ca2+ reuptake rate under catecholamine stimulation we observed in cMAO-Adef hearts (Figure 3G–I). Although total SERCA2a and PLB levels are unchanged (see Supplementary material online, Figure S7 and Figure 6A and B), the phosphorylation of PLB monomers and pentamers at the Serine 16 site was significantly increased after catecholamine stimulation in cMAO-Adef hearts compared with WT (Figure 6C and D). Serine16 of PLB is phosphorylated by PKA and reflects reduced inhibition of SERCA2 activity,45,46 which is in line with the faster Ca2+ reuptake rates in both ex vivo hearts and reduced diastolic Ca2+ levels we found in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes (Figures 3G–I and 4F). Concurrently, phosphorylation of PLB at threonine 17, a CaMKII or AKT site,47,48 is unaltered (Figure 6C and D).

Figure 6.

PLB phosphorylation in WT and cMAO-Adef myocardium after catecholamine stimulation. Myocardial tissue from WT and cMAO-Adef mouse hearts were rapidly collected and frozen in liquid N2 at baseline or 30 min after injection with caffeine (120 mg/kg) and epinephrine (2 mg/kg). Representative immunoblots of p-PLB (Ser-16), p-PLB (Thr-17), and total PLB at baseline (A) and 30 min after epinephrine/caffeine challenge (C) are shown (N = 5–6 mice for each genotype). Densitometric quantification of total and phosphorylated levels of the PLB pentamer and monomer at baseline (B) and after epinephrine/caffeine (D). Data are normalized to GAPDH and shown as mean± SEM. Data are analysed by unpaired t-test. P-values of comparisons are shown in the graph. PLB, phospholamban.

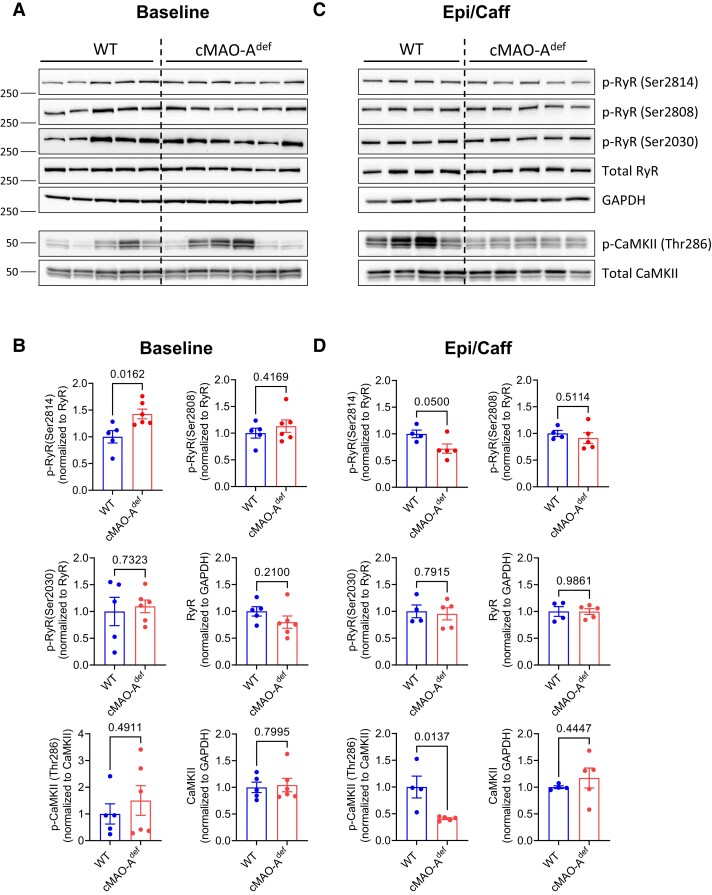

Lower diastolic Ca2+ levels could be both a cause and an effect of reduced diastolic SR Ca2+ leak and is supported by our observations that cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes have reduced Ca2+ spark activities under catecholamine stimulation (Figure 5A–D). Ca2+ release from the SR is mediated through RyR2 channels and increased through post-translational modification.35,49,50 In support of this hypothesis, we found a significant increase in RyR2 phosphorylation at serine 2814 in cMAO-Adef hearts at baseline, but not serine 2808 and serine 2030 (Figure 7A and B). Serine 2814 phosphorylation is likely to have contributed to the larger Ca2+ transients observed in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes at baseline (Figures 3E and 4G). In sharp contrast, serine 2814 phosphorylation is significantly reduced after catecholamine stress (Figure 7C and D). Serine 2814 of RyR2 is a well-known target of CaMKII, which has a prominent role in the pathophysiology of both heart failure and arrhythmias.35,49,50 Consistently, CaMKII autophosphorylation at the threonine 286 site, a marker of CaMKII activation, was significantly suppressed in cMAO-Adef hearts after catecholamine stress relative to WT mice (Figure 7C and D).

Figure 7.

CaMKII and RyR phosphorylation in WT and cMAO-Adef myocardium after catecholamine stimulation. Representative immunoblots of p-RyR2 (Ser-2814), p-RyR2 (Ser-2808), p-RyR2 (Ser-2030), p-CaMKII (Thr-286), total RyR2 and CaMKII at baseline (A) and 30 min after epinephrine/caffeine challenge (C) are shown (N = 5–6 mice for each genotype). Densitometric quantification of total and phosphorylated RyR2 and CaMKII at baseline (B) and 30 min after epinephrine/caffeine challenge (D). Total RyR2 or CaMKII protein is normalized to GAPDH. Phosphorylated RyR2 and CaMKII are normalized to corresponding total protein. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Data are analysed by unpaired t-test. P-values of comparisons are shown in the graph.

Together, these data suggest that cardiac MAO-A inhibition alters the phosphorylation of Ca2+ handling proteins leading to accelerated SR Ca2+ uptake but limiting spontaneous SR Ca2+ release upon stimulation that involves the suppression of CaMKII activation.

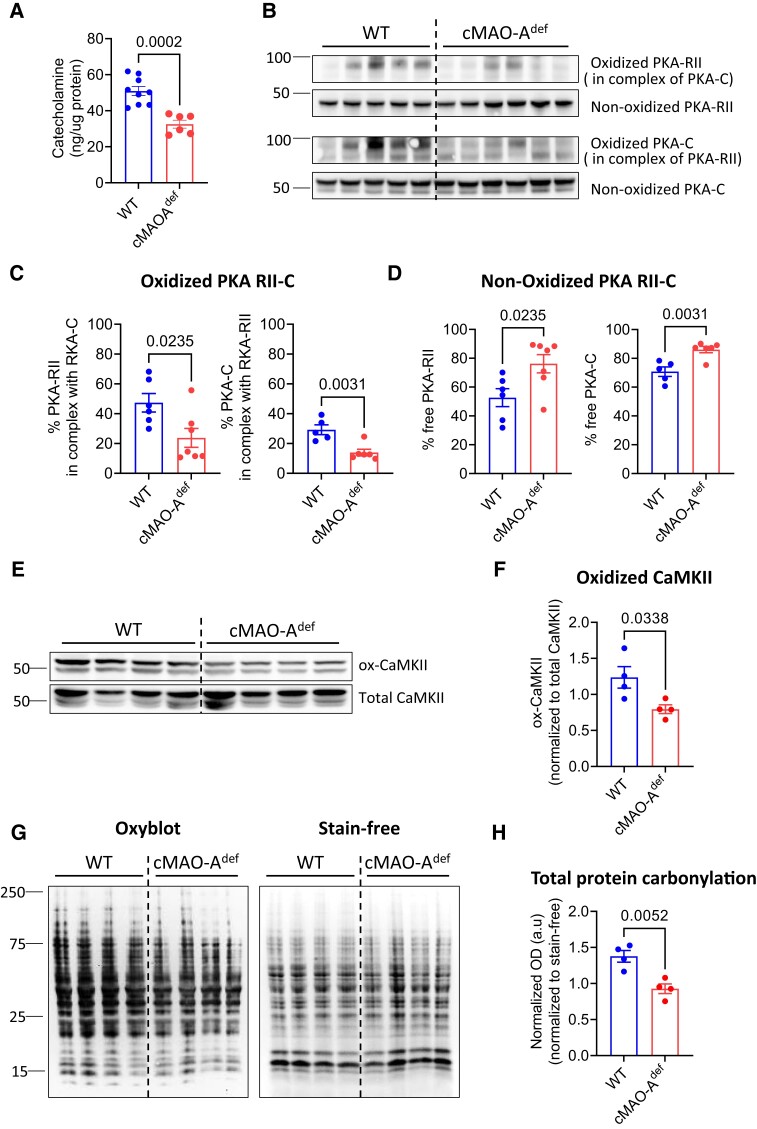

3.6. Cardiac MAO-A inhibition reduces catecholamine-induced oxidation of PKA, CaMKII and overall oxidative stress in the heart

To further understand the mechanisms related to cardiac MAO-A deficiency and the increased PKA activity which enhances PLB phosphorylation under catecholamine stress, we first tested the hypothesis that inhibiting cardiac MAO-A might indirectly result in PKA stimulation via catecholamine accumulation. Unexpectedly, in contrast to the baseline (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1B), catecholamine levels in the MAO-A deficient hearts post Epi/Caff stimulation were significantly lower compared with WT hearts (Figure 8A), thus suggesting alternate mechanisms may be involved.

Figure 8.

Cardiac MAO-A inhibition reduces catecholamine levels and oxidation of PKA, CaMKII and overall oxidative stress in the stress heart. (A) Total catecholamine concentration in the WT and cMAOdef heart tissue after epinephrine/caffeine challenge are shown (N = 6–7 mice for each genotype). Representative immunoblots (B) and quantification of oxidized (C) and non-oxidized (D) PKA-RII and PKA-C after epinephrine/caffeine challenge are shown (N = 6–7 mice for each genotype). Immunoblots (E) and densitometric quantification (F) of ox-CaMKII and total CaMKII after epinephrine/caffeine challenge are shown (N = 4 mice for each genotype). Oxidized CaMKII is normalized to total CaMKII protein. (G) OxyBlot analysis of total protein oxidation (left) as a marker of oxidative stress in heart lysates after epinephrine/caffeine challenge. Stain-free gel (right) was used for total protein loading control. (N = 4 mice for each genotype). (H) Lane intensities in OxyBlot were normalized to the corresponding loading controls and ratios were used to indicate total protein carbonyl levels. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. Data are analysed by unpaired t-test. P-values of comparisons are shown in the graph.

Catecholamines boosts cardiac function, an action often coupled with ROS generation.51 MAO-A is a key source of cellular ROS and is tethered to the outer mitochondrial membrane. Indeed, in both WT and cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes, mitochondrial ROS generation rose in a pacing frequency-dependent manner (see Supplementary material online, Figure S8), without a significant difference between the two genotypes (data not shown). However, under NE (1 μM) stimulation, ROS generation was further amplified in WT cardiomyocytes, whereas no further increase was observed in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes (see Supplementary material online, Figure S8). These findings suggest that MAO-A activity is tightly associated with ROS production under catecholamine stimulation conditions.

Of interest, the Type II PKA holoenzyme located at the SR is a redox-sensitive kinase that regulates SERCA2a function under sympathetic stimulation.52 Oxidation of Type II PKA prompts the complex formation of RII regulatory and catalytic (C) subunits, which subsequently diminishes kinase activity.53 In line with the absence of an additional ROS increase in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes under catecholamine stimulation (see Supplementary material online, Figure S8), a significant reduction in the oxidized RII-C interprotein complex was observed in cMAO-Adef hearts following Epi/Caff stimulation (Figure 8B and C). Correspondingly, an increased amount of unoxidized PKA-RII and C subunits were detected (Figure 8B and D). This implies that the increased PKA activity in cMAO-Adef hearts under sympathetic stress could be due to a reduction in Type II PKA holoenzyme oxidation.

Likewise, oxidation of CaMKII is also involved in both physiological and pathological regulation of calcium homeostasis.54–57 Compared with WT, oxidized CaMKII levels were significantly decreased in cMAO-Adef hearts after catecholamine stress (Figure 8E and F). Interestingly, antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine (NAC, 5 mM) increased basal Ca2+ transient, however, it significantly inhibited NE (100 nM) induced increase in Ca2+ transient in the WT cardiomyocytes (see Supplementary material online, Figure S9), a phenotype which is similar to that was observed in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes. However, cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes were insensitive to NAC at both baseline and under NE stimulation (see Supplementary material online, Figure S10), suggesting a reduced ROS signalling in the cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes.

Moreover, the overall degree of protein oxidation (carbonylation) was also dramatically reduced in the cMAO-Adef hearts after Epi/Caff challenge as demonstrated by OxyBlot analysis (Figure 8G and H). Together, these data suggest that inhibiting cardiac MAO-A may have an anti-arrhythmic effect by reducing ROS/RCS-activated proarrhythmic signals.

4. Discussion

Growing evidence strongly suggests that MAO-A plays a pathogenic role in various cardiac diseases including post-ischaemic myocardial injury,58,59 heart failure,9,60 postoperative atrial fibrillation,61 and diabetic cardiomyopathy.5,62 In this study, we provide the first direct evidence that MAO-A is also involved in ventricular arrhythmogenesis.

Based on a large and well-balanced clinical patient cohort, our study discovered that clinically depressed patients treated with MAOIs had a significantly lower risk of adverse arrhythmic outcomes compared with SSRI-treated patients (Figure 1). Of note, MAOIs, due to their undesirable side effects,63 are no longer the primary choice for antidepressants. In line with this notion, the reduced arrhythmia risk might be attributed to MAO inhibition (MAO-A and/or MAO-B) in a range of tissues, not just the heart. We have also demonstrated that mice with cardiomyocyte-specific MAO-A inhibition are protected from catecholamine-induced ventricular tachycardia (Figure 2). While human studies provide a systemic perspective, our mouse model offers heart-specific insights that suggest a potential therapeutic benefit of cardiac-specific MAO-A inhibition in patients with arrhythmias.

Catecholamine overload is a key driver of arrhythmias owing largely to β-adrenergic overactivation and the consequent aberrant Ca2+ handling in cardiomyocytes.36 To gain mechanistic insight into the anti-arrhythmic effect of cardiac MAO-A inhibition, we assessed catecholamine levels in WT and cMAO-Adef mouse hearts before and after stimulation. As expected, cMAO-Adef heart did exhibit increased tissue catecholamine levels at baseline (unstimulated), but remarkably the catecholamine levels are significantly lower in the cMAO-Adef hearts after Epi/Caff challenge when compared with WT (Figure 8A). These intriguing results indicate adaptive responses have occurred in the cMAO-Adef mice over time to diminish catecholaminergic overload during stress, potentially through the enhancement of systemic catecholamine clearance and/or decreased neuronal catecholamine release in response to sympathetic stress, which also contributes to the observed anti-arrhythmic effect.

In addition to decreased catecholamine levels during stress, cMAO-Adef hearts also exhibit enhanced diastolic Ca2+ control, as reflected by increased diastolic Ca2+ reuptake (Figure 3G–I), suggesting an elevated SERCA activity. Under catecholamine stress, increased phosphorylation of PLB at serine16 (a PKA target), the key inhibitory regulator of SERCA,44 is observed in cMAO-Adef hearts (Figure 6C and D). This suggests a scenario where elevated PKA activity enhances PLB phosphorylation, subsequently accelerating Ca2+ reuptake and lowering diastolic Ca2+ levels (Figure 4F) in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes under catecholamine stimulation.

The apparent contradiction of lower catecholamine levels and higher PKA activity in cMAO-Adef hearts can be reconciled when considering the redox sensitivity of PKA, in addition to the regulation by cAMP. Specifically, oxidation increases the enzymatic activity of Type I PKA,64,65 while it reduces the activity of Type II PKA,53 which is known to be involved in β-adrenergic regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis and muscle contraction.52 Importantly, cMAO-Adef hearts demonstrate a significant reduction in the oxidation of Type II PKA under catecholamine stress (Figure 8B and C), which can be attributed to the decreased generation of ROS/RCS due to MAO-A inhibition (see Supplementary material online, Figure S8 and Figure 8G and H).

While increased PKA-mediated phosphorylation of PLB under β-adrenergic stimulation is typically associated with increased Ca2+ transients and SR Ca2+ content,66 cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes displayed a reduction in both Ca2+ transient amplitude and SR Ca2+ content compared with WT under catecholamine stimulation (Figures 4H and 5F). This could potentially be due to reduced Ca2+ influx through the L-type calcium channel (LTCC) and subsequently diminished Ca2+ release from RyR2 in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes under catecholamine stimulation. This notion is supported by the observed reduction of CaMKII oxidation in cMAO-Adef hearts under stress (Figure 8E and F), as oxidant-activated CaMKII has been shown to potentially activate the LTCC,67 thereby contributing to increased muscle contractility.54 H2O2 has a similar effect, enhancing the influx of Ca2+ through this same pathway.68 On the other hand, given that CaMKII activity is also involved in sensitizing physiological RyR2 Ca2+ release,69 significantly reduced autophosphorylation of CaMKII in cMAO-Adef hearts under stress (Figure 7C and D) may also contribute to the reduced Ca2+ transients (Figure 4H) in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes under stress. In either case, reduced overall CaMKII activity attenuates phosphorylation of RyR2 at serine 2814 which reduces diastolic Ca2+ leak (Figure 5A–D) and further prevents arrhythmogenic Ca2+ wave generation (see Supplementary material online, Figure S5). This is in line with the previous report of transgenic mice with RyR-S2814 (S2814A) ablation in which spontaneous Ca2+ waves were reduced, rendering them protected from catecholaminergic-induced arrhythmias.70 Overall, the increased Type II PKA activity together with the reduced CaMKII activity in cMAO-Adef hearts during catecholamine stress enhances the regulation of diastolic Ca2+. However, this may come with a trade-off of reduced systolic Ca2+ release. Conversely, at baseline, Ca2+ transient is increased in cMAO-Adef cardiomyocytes compared with WT (Figures 3E and 4G). This may be a result of systemic alterations due to the increased basal catecholamine levels in the cMAO-Adef heart (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1B). What is clear from these findings is that the precise underlying mechanism is likely multifactorial and needs further investigation.

Previous studies from our group and others have demonstrated that MAO-mediated catecholamine metabolism leads to the robust generation of reactive catecholaldehydes in the heart.9,71 In excess, these RCS disrupt mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OxPHOS)72 and trigger pro-inflammatory/pro-fibrotic signalling in the myocardium.73 The decreased overall protein carbonylation (Figure 8G and H) in cMAO-Adef hearts after catecholamine overload could also contribute to the lower arrhythmogenesis in these mice.

Taken together, our findings strongly indicate that cardiac MAO-A inhibition exerts an anti-arrhythmic effect by enhancing diastolic Ca2+ handling under catecholamine stress. Mechanistically, this is facilitated by a reduction in ROS/RCS generation, consequently leading to decreased oxidation of Type II PKA and CaMKII. The former promotes PLB phosphorylation improving diastolic Ca2+ reuptake, while the latter reduces RyR2 phosphorylation, decreasing diastolic Ca2+ leak. Ultimately, these changes together result in lower diastolic Ca2+ levels, thereby preventing the generation of arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves. This anti-arrhythmic effect of cardiac MAO-A inhibition could potentially hold therapeutic promise in the context of aging, diabetes, and heart failure, conditions which are well known to be associated with increased cardiomyocyte MAO expression in parallel with risk of arrhythmias.9,11,62,72,74

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Qian Shi, Department of Internal Medicine, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, 285 Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

Hamza Malik, Department of Internal Medicine, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, 285 Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

Rachel M Crawford, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Experimental Therapeutics, College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, 180 S Grand Ave., Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

Jennifer Streeter, Department of Internal Medicine, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, 285 Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

Jinxi Wang, Department of Internal Medicine, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, 285 Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

Ran Huo, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Experimental Therapeutics, College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, 180 S Grand Ave., Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

Jean C Shih, Department of Pharmacology and Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Pharmacy, University of Southern California, 1985 Zonal Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90089, USA.

Biyi Chen, Department of Internal Medicine, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, 285 Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

Duane Hall, Department of Internal Medicine, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, 285 Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA; Abboud Cardiovascular Research Center, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, CBRB 2267285, Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

E Dale Abel, Department of Internal Medicine, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, 285 Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA; Abboud Cardiovascular Research Center, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, CBRB 2267285, Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA; Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, 169 Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

Long-Sheng Song, Department of Internal Medicine, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, 285 Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA; Abboud Cardiovascular Research Center, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, CBRB 2267285, Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA; Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, 169 Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

Ethan J Anderson, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Experimental Therapeutics, College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, 180 S Grand Ave., Iowa City, IA 52242, USA; Abboud Cardiovascular Research Center, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, CBRB 2267285, Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA; Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, 169 Newton Rd, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Authors’ contributions

Q.S., H.M., R.M.C., J.S., J.W., R.H., and B.C. performed experiments and analysed data. J.C.S. provided MAO-A flox/flox (MAO-Af/f) mice. Q.S., E.J.A., and L.-S.S. were responsible for the overall project concept. Q.S. designed the experiments and prepared the manuscript. Q.S., D.H., E.D.A., L.-S.S., and E.J.A. discussed the results and edited the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01 HL122863, R21 HL057006, R01 HL130346, R01 HL157741, and R01 HL157781), American Heart Association (20SFRN35200003 and CDA935054) and Department of Veterans Affairs (I01-BX002334).

Data availability

Additional data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Translational perspective.

This study implicates catecholamine metabolism in arrhythmogenesis and reveals that monoamine oxidase is linked to Ca2+ regulation in the heart. It further illustrates the therapeutic potential of cardiac monoamine oxidase-A inhibition as a dual-purpose drug target to simultaneously manage depression and lower arrhythmia risk in affected patients.

References

- 1. Herrman H, Patel V, Kieling C, Berk M, Buchweitz C, Cuijpers P, Furukawa TA, Kessler RC, Kohrt BA, Maj M, McGorry P, Reynolds CF, Weissman MM, Chibanda D, Dowrick C, Howard LM, Hoven CW, Knapp M, Mayberg HS, Penninx BWJH, Xiao S, Trivedi M, Uher R, Vijayakumar L, Wolpert M. Time for united action on depression: a Lancet–World Psychiatric Association Commission. Lancet 2022;399:957–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thase ME, Trivedi MH, Rush AJ. MAOIs in the contemporary treatment of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 1995;12:185–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shih JC, Chen K, Ridd MJ. Monoamine oxidase: from genes to behavior. Annu Rev Neurosci 1999;22:197–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Manni ME, Rigacci S, Borchi E, Bargelli V, Miceli C, Giordano C, Raimondi L, Nediani C. Monoamine oxidase is overactivated in left and right ventricles from ischemic hearts: an intriguing therapeutic target. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016;2016:4375418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Umbarkar P, Singh S, Arkat S, Bodhankar SL, Lohidasan S, Sitasawad SL. Monoamine oxidase-A is an important source of oxidative stress and promotes cardiac dysfunction, apoptosis, and fibrosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Free Radic Biol Med 2015;87:263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kaludercic N, Carpi A, Menabò R, Di Lisa F, Paolocci N. Monoamine oxidases (MAO) in the pathogenesis of heart failure and ischemia/reperfusion injury. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011;1813:1323–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sturza A, Duicu OM, Vaduva A, Dănilă MD, Noveanu L, Varró A, Muntean DM. Monoamine oxidases are novel sources of cardiovascular oxidative stress in experimental diabetes. Can J Physiol Pharm 2015;93:555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaludercic N, Mialet-Perez J, Paolocci N, Parini A, Di Lisa F. Monoamine oxidases as sources of oxidants in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2014;73:34–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaludercic N, Takimoto E, Nagayama T, Feng N, Lai EW, Bedja D, Chen K, Gabrielson KL, Blakely RD, Shih JC, Pacak K, Kass DA, Lisa FD, Paolocci N. Monoamine oxidase A–mediated enhanced catabolism of norepinephrine contributes to adverse remodeling and pump failure in hearts with pressure overload. Circ Res 2010;106:193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burgoyne JR, Oka S, Ale-Agha N, Eaton P. Hydrogen peroxide sensing and signaling by protein kinases in the cardiovascular system. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013;18:1042–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang Y, Zhao M, Shi Q, Xu B, Zhu C, Li M, Mir V, Bers DM, Xiang YK. Monoamine oxidases desensitize intracellular β1AR signaling in heart failure. Circ Res 2021;129:965–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang Y, Zhao M, Xu B, Bahriz SMF, Zhu C, Jovanovic A, Ni H, Jacobi A, Kaludercic N, Di Lisa F, Hell JW, Shih JC, Paolocci N, Xiang YK. Monoamine oxidase A and organic cation transporter 3 coordinate intracellular β1AR signaling to calibrate cardiac contractile function. Basic Res Cardiol 2022;117:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liao C-P, Lin T-P, Li P-C, Geary LA, Chen K, Vaikari V, Wu J, Lin C-H, Gross ME, Shih JC. Loss of MAOA in epithelia inhibits adenocarcinoma development, cell proliferation and cancer stem cells in prostate. Oncogene 2018;37:5175–5190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abel ED, Kaulbach HC, Tian R, Hopkins JCA, Duffy J, Doetschman T, Minnemann T, Boers M-E, Hadro E, Oberste-Berghaus C, Quist W, Lowell BB, Ingwall JS, Kahn BB. Cardiac hypertrophy with preserved contractile function after selective deletion of GLUT4 from the heart. J Clin Invest 1999;104:1703–1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen W, Wang R, Chen B, Zhong X, Kong H, Bai Y, Zhou Q, Xie C, Zhang J, Guo A, Tian X, Jones PP, O’Mara ML, Liu Y, Mi T, Zhang L, Bolstad J, Semeniuk L, Cheng H, Zhang J, Chen J, Tieleman PD, Gillis AM, Duff HJ, Fill M, Song L-S, Chen WS. The ryanodine receptor store-sensing gate controls Ca2+ waves and Ca2+-triggered arrhythmias. Nat Med 2014;20:184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang Y, Li C, Shi L, Chen X, Cui C, Huang J, Chen B, Hall DD, Pan Z, Lu M, Hong J, Song L-S, Zhao S. Integrin β1D deficiency–mediated RyR2 dysfunction contributes to catecholamine-sensitive ventricular tachycardia in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2020;141:1477–1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Curtis MJ, Hancox JC, Farkas A, Wainwright CL, Stables CL, Saint DA, Clements-Jewery H, Lambiase PD, Billman GE, Janse MJ, Pugsley MK, Ng GA, Roden DM, Camm AJ, Walker MJA. The Lambeth Conventions (II): guidelines for the study of animal and human ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias. Pharmacol Ther 2013;139:213–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen B, Guo A, Gao Z, Wei S, Xie Y-PP, Chen S, Anderson ME, Song L-SS. In situ confocal imaging in intact heart reveals stress-induced Ca(2+) release variability in a murine catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia model of type 2 ryanodine receptor(R4496C+/−) mutation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2012;5:841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guatimosim S, Guatimosim C, Song L-S. Light microscopy, methods and protocols. Methods Mol Biol 2011;689:205–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bassani RA, Bassani JW, Bers DM. Mitochondrial and sarcolemmal Ca2+ transport reduce [Ca2+]i during caffeine contractures in rabbit cardiac myocytes. J Physiol 1992;453:591–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li L, Chu G, Kranias EG, Bers DM. Cardiac myocyte calcium transport in phospholamban knockout mouse: relaxation and endogenous CaMKII effects. Am J Physiol 1998;274:H1335–H1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nickel AG, von Hardenberg A, Hohl M, Löffler JR, Kohlhaas M, Becker J, Reil J-C, Kazakov A, Bonnekoh J, Stadelmaier M, Puhl S-L, Wagner M, Bogeski I, Cortassa S, Kappl R, Pasieka B, Lafontaine M, Lancaster CRD, Blacker TS, Hall AR, Duchen MR, Kästner L, Lipp P, Zeller T, Müller C, Knopp A, Laufs U, Böhm M, Hoth M, Maack C. Reversal of mitochondrial transhydrogenase causes oxidative stress in heart failure. Cell Metab 2015;22:472–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. de Graaf MA, Jager KJ, Zoccali C, Dekker FW. Matching, an appealing method to avoid confounding? Nephron Clin Pract 2011;118:c315–c318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sikkel MB, Francis DP, Howard J, Gordon F, Rowlands C, Peters NS, Lyon AR, Harding SE, MacLeod KT. Hierarchical statistical techniques are necessary to draw reliable conclusions from analysis of isolated cardiomyocyte studies. Cardiovasc Res 2017;113:1743–1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sivasubramaniam SD, Finch CC, Rodriguez MJ, Mahy N, Billett EE. A comparative study of the expression of monoamine oxidase-A and -B mRNA and protein in non-CNS human tissues. Cell Tissue Res 2003;313:291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saura J, Kettler R, Da Prada M, Richards J. Quantitative enzyme radioautography with 3H-Ro 41-1049 and 3H-Ro 19- 6327 in vitro: localization and abundance of MAO-A and MAO-B in rat CNS, peripheral organs, and human brain. J Neurosci 1992;12:1977–1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cerrone M, Colombi B, Santoro M, di Barletta M, Scelsi M, Villani L, Napolitano C, Priori SG. Bidirectional ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation elicited in a knock-in mouse model carrier of a mutation in the cardiac ryanodine receptor. Circ Res 2005;96:e77–e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhou Q, Xiao J, Jiang D, Wang R, Vembaiyan K, Wang A, Smith CD, Xie C, Chen W, Zhang J, Tian X, Jones PP, Zhong X, Guo A, Chen H, Zhang L, Zhu W, Yang D, Li X, Chen J, Gillis AM, Duff HJ, Cheng H, Feldman AM, Song L-S, Fill M, Back TG, Chen WS. Carvedilol and its new analogs suppress arrhythmogenic store overload–induced Ca2+ release. Nat Med 2011;17:1003–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang J, Zhou Q, Smith CD, Chen H, Tan Z, Chen B, Nani A, Wu G, Song L-S, Fill M, Back TG, Chen SRW. Non-β-blocking R-carvedilol enantiomer suppresses Ca2+ waves and stress-induced ventricular tachyarrhythmia without lowering heart rate or blood pressure. Biochem J 2015;470:233–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jelinek M, Wallach C, Ehmke H, Schwoerer AP. Genetic background dominates the susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias in a murine model of β-adrenergic stimulation. Sci Rep 2018;8:2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang C, Zhang Y. Caffeine and dobutamine challenge induces bidirectional ventricular tachycardia in normal rats. Heart Rhythm O2 2020;1:359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kistamás K, Veress R, Horváth B, Bányász T, Nánási PP, Eisner DA. Calcium handling defects and cardiac arrhythmia syndromes. Front Pharmacol 2020;11:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Landstrom AP, Dobrev D, Wehrens X. Calcium signaling and cardiac arrhythmias. Circ Res 2017;120:1969–1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eisner DA, Caldwell JL, Trafford AW, Hutchings DC. The control of diastolic calcium in the heart. Circ Res 2020;126:395–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ai X, Curran JW, Shannon TR, Bers DM, Pogwizd SM. Ca2+/calmodulin–dependent protein kinase modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor phosphorylation and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak in heart failure. Circ Res 2005;97:1314–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Curran J, Hinton MJ, Ríos E, Bers DM, Shannon TR. Beta-adrenergic enhancement of sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium leak in cardiac myocytes is mediated by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Circ Res 2007;100:391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grimm M, Ling H, Willeford A, Pereira L, Gray C, Erickson JR, Sarma S, Respress JL, Wehrens X, Bers DM, Brown J. CaMKIIδ mediates β-adrenergic effects on RyR2 phosphorylation and SR Ca2+ leak and the pathophysiological response to chronic β-adrenergic stimulation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2015;85:282–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cheng H, Lederer W, Cannell M. Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science 1993;262:740–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bers DM. Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu Rev Physiol 2008;70:23–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cheng H, Lederer MR, Xiao R-P, Gómez AM, Zhou Y-Y, Ziman B, Spurgeon H, Lakatta EG, Lederer WJ. Excitation-contraction coupling in heart: new insights from Ca2+ sparks. Cell Calcium 1996;20:129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shannon TR, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM. Potentiation of fractional sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release by total and free intra-sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium concentration. Biophys J 2000;78:334–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Barcenas-Ruiz L, Beuckelmann DJ, Wier WG. Sodium-calcium exchange in heart: membrane currents and changes in [Ca2+]i. Science 1987;238:1720–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bers DM. Calcium fluxes involved in control of cardiac myocyte contraction. Circ Res 2000;87:275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. MacLennan DH, Kranias EG. Phospholamban: a crucial regulator of cardiac contractility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2003;4:566–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Koss KL, Kranias EG. Phospholamban: a prominent regulator of myocardial contractility. Circ Res 1996;79:1059–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sasaki T, Inui M, Kimura Y, Kuzuya T, Tada M. Molecular mechanism of regulation of Ca2+ pump ATPase by phospholamban in cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Effects of synthetic phospholamban peptides on Ca2+ pump ATPase. J Biol Chem 1992;267:1674–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mattiazzi A, Mundiña-Weilenmann C, Guoxiang C, Vittone L, Kranias E. Role of phospholamban phosphorylation on Thr17 in cardiac physiological and pathological conditions. Cardiovasc Res 2005;68:366–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Catalucci D, Latronico MVG, Ceci M, Rusconi F, Young HS, Gallo P, Santonastasi M, Bellacosa A, Brown JH, Condorelli G. Akt increases sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ cycling by direct phosphorylation of phospholamban at Thr17. J Biol Chem 2009;284:28180–28187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Maier LS, Bers DM. Role of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) in excitation–contraction coupling in the heart. Cardiovasc Res 2007;73:631–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yang D, Zhu W-Z, Xiao B, Brochet DXP, Chen SRW, Lakatta EG, Xiao R-P, Cheng H. Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II–dependent phosphorylation of ryanodine receptors suppresses Ca2+ sparks and Ca2+ waves in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 2007;100:399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Perjés Á, Kubin AM, Kónyi A, Szabados S, Cziráki A, Skoumal R, Ruskoaho H, Szokodi I. Physiological regulation of cardiac contractility by endogenous reactive oxygen species. Acta Physiol 2012;205:26–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Di Benedetto G, Zoccarato A, Lissandron V, Terrin A, Li X, Houslay MD, Baillie GS, Zaccolo M. Protein kinase A type I and type II define distinct intracellular signaling compartments. Circ Res 2008;103:836–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. de Piña MZ, Vázquez-Meza H, Pardo JP, Rendón JL, Villalobos-Molina R, Riveros-Rosas H, Piña E. Signaling the signal, cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase inhibition by insulin-formed H2O2 and reactivation by thioredoxin. J Biol Chem 2008;283:12373–12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wang Q, Hernández-Ochoa EO, Viswanathan MC, Blum ID, Do DC, Granger JM, Murphy KR, Wei A-C, Aja S, Liu N, Antonescu CM, Florea LD, Talbot CC, Mohr D, Wagner KR, Regot S, Lovering RM, Gao P, Bianchet MA, Wu MN, Cammarato A, Schneider MF, Bever GS, Anderson ME. CaMKII oxidation is a critical performance/disease trade-off acquired at the dawn of vertebrate evolution. Nat Commun 2021;12:3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wagner S, Ruff HM, Weber SL, Bellmann S, Sowa T, Schulte T, Anderson ME, Grandi E, Bers DM, Backs J, Belardinelli L, Maier LS. Reactive oxygen species–activated Ca/calmodulin kinase IIδ is required for late I Na augmentation leading to cellular Na and Ca overload. Circ Res 2011;108:555–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xie L-H, Chen F, Karagueuzian HS, Weiss JN. Oxidative stress–induced afterdepolarizations and calmodulin kinase II signaling. Circ Res 2009;104:79–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Swaminathan PD, Purohit A, Soni S, Voigt N, Singh MV, Glukhov AV, Gao Z, He BJ, Luczak ED, Joiner MA, Kutschke W, Yang J, Donahue JK, Weiss RM, Grumbach IM, Ogawa M, Chen P-S, Efimov I, Dobrev D, Mohler PJ, Hund TJ, Anderson ME. Oxidized CaMKII causes cardiac sinus node dysfunction in mice. J Clin Invest 2011;121:3277–3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bianchi P, Kunduzova O, Masini E, Cambon C, Bani D, Raimondi L, Seguelas M-H, Nistri S, Colucci W, Leducq N, Parini A. Oxidative stress by monoamine oxidase mediates receptor-independent cardiomyocyte apoptosis by serotonin and postischemic myocardial injury. Circulation 2005;112:3297–3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Pchejetski D, Kunduzova O, Dayon A, Calise D, Seguelas M-H, Leducq N, Seif I, Parini A, Cuvillier O. Oxidative stress–dependent sphingosine kinase-1 inhibition mediates monoamine oxidase A–associated cardiac cell apoptosis. Circ Res 2007;100:41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Villeneuve C, Guilbeau-Frugier C, Sicard P, Lairez O, Ordener C, Duparc T, De Paulis D, Couderc B, Spreux-Varoquaux O, Tortosa F, Garnier A, Knauf C, Valet P, Borchi E, Nediani C, Gharib A, Ovize M, Delisle M-B, Parini A, Mialet-Perez J. p53-PGC-1α pathway mediates oxidative mitochondrial damage and cardiomyocyte necrosis induced by monoamine oxidase-A upregulation: role in chronic left ventricular dysfunction in mice. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013;18:5–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Anderson EJ, Efird JT, Davies SW, O’Neal WT, Darden TM, Thayne KA, Katunga LA, Kindell LC, Ferguson TB, Anderson CA, Chitwood WR, Koutlas TC, Williams JM, Rodriguez E, Kypson AP. Monoamine oxidase is a major determinant of redox balance in human atrial myocardium and is associated with postoperative atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e000713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Deshwal S, Forkink M, Hu C-H, Buonincontri G, Antonucci S, Sante MD, Murphy MP, Paolocci N, Mochly-Rosen D, Krieg T, Lisa FD, Kaludercic N. Monoamine oxidase-dependent endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria dysfunction and mast cell degranulation lead to adverse cardiac remodeling in diabetes. Cell Death Differ 2018;25:1671–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Yamada M, Yasuhara H. Clinical pharmacology of MAO inhibitors: safety and future. Neurotoxicology 2004;25:215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Simon JN, Vrellaku B, Monterisi S, Chu SM, Rawlings N, Lomas O, Marchal GA, Waithe D, Syeda F, Gajendragadkar PR, Jayaram R, Sayeed R, Channon KM, Fabritz L, Swietach P, Zaccolo M, Eaton P, Casadei B. Oxidation of protein kinase A regulatory subunit PKARIα protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting lysosomal-triggered calcium release. Circulation 2021;143:449–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Brennan JP, Bardswell SC, Burgoyne JR, Fuller W, Schröder E, Wait R, Begum S, Kentish JC, Eaton P. Oxidant-induced activation of type I protein kinase A is mediated by RI subunit interprotein disulfide bond formation. J Biol Chem 2006;281:21827–21836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bers DM. Cardiac excitation–contraction coupling. Nature 2002;415:198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Song Y-H, Cho H, Ryu S-Y, Yoon J-Y, Park S-H, Noh C-I, Lee S-H, Ho W-K. L-type Ca2+ channel facilitation mediated by H2O2-induced activation of CaMKII in rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2010;48:773–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Andersson DC, Fauconnier J, Yamada T, Lacampagne A, Zhang S, Katz A, Westerblad H. Mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species contributes to the β-adrenergic stimulation of mouse cardiomycytes. J Physiol 2011;589:1791–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Li L, Satoh H, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM. The effect of Ca2+–calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II on cardiac excitation–contraction coupling in ferret ventricular myocytes. J Physiol 1997:501:17–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. van Oort RJ, McCauley MD, Dixit SS, Pereira L, Yang Y, Respress JL, Wang Q, De Almeida AC, Skapura DG, Anderson ME, Bers DM, Wehrens XHT. Ryanodine receptor phosphorylation by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II promotes life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in mice with heart failure. Circulation 2010;122:2669–2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Nelson M-AM, Builta ZJ, Monroe TB, Doorn JA, Anderson EJ. Biochemical characterization of the catecholaldehyde reactivity of L-carnosine and its therapeutic potential in human myocardium. Amino Acids 2019;51:97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Nelson M-AM, Efird JT, Kew KA, Katunga LA, Monroe TB, Doorn JA, Beatty CN, Shi Q, Akhter SA, Alwair H, Robidoux J, Anderson EJ. Enhanced catecholamine flux and impaired carbonyl metabolism disrupt cardiac mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in diabetes patients. Antioxid Redox Signal 2021;35:235–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Monroe TB, Anderson EJ. A catecholaldehyde metabolite of norepinephrine induces myofibroblast activation and toxicity via the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts: mitigating role of L-carnosine. Chem Res Toxicol 2021;34:2194–2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Maurel A, Hernandez C, Kunduzova O, Bompart G, Cambon C, Parini A, Francés B. Age-dependent increase in hydrogen peroxide production by cardiac monoamine oxidase A in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003;284:H1460–H1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement