Abstract

The Pd-catalyzed C–H activation of natural tryptophan residues has emerged as a promising approach for their direct synthetic modification. While using water as the solvent and harnessing air as the oxidant is enticing, these conditions induce catalyst deactivation by promoting the formation of inactive Pd(0) clusters. In this work, we have studied optimized Pd-based catalytic systems via nonsteady state kinetic analysis and in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) to overcome catalyst deactivation, which enables the effective use of lower Pd loadings.

Keywords: homogeneous catalysis, reaction kinetics, X-ray absorption spectroscopy, aerobic oxidation, C−H activation, sustainable chemistry

Introduction

As one of the essential amino acids, tryptophan is key in the (bio)synthesis of peptides, proteins, and many small indole-containing molecules of biological relevance.1−3 In synthetic chemistry routes, harnessing this abundant and biobased building block can be a large asset for their overall sustainability and cost efficiency.4 Moreover, tryptophan residues are often tied to specific protein functions and possess intrinsic fluorescence, which results in a widespread use of tryptophan analogues in biochemical research.5−12 Along with the rise of bioconjugation methods for the site-selective synthetic modification of peptides or proteins, the catalytic conversion of the C–H bonds in native tryptophan residues is a promising approach to further expand such synthetic possibilities.13−17 Rather than reacting on functional groups, such as −NH2 or −SH, in lysine or cysteine or relying on the labeling with non-native amino acid residues (e.g., azide or alkyne functional groups), a recent research focus is to translate the advances in Pd-catalyzed C–H bond activation on the C2 position of indole scaffolds18−22 toward the direct C–H coupling of tryptophan residues. Along with the diversification of the individual amino acid, the strategy has also been demonstrated in the postsynthetic modification of tryptophan residues in peptide chains,23−28 for the formation of peptide macrocycles,29−31 or the direct bioconjugation of proteins32 by cleaving the C–H bonds in native tryptophan residues.

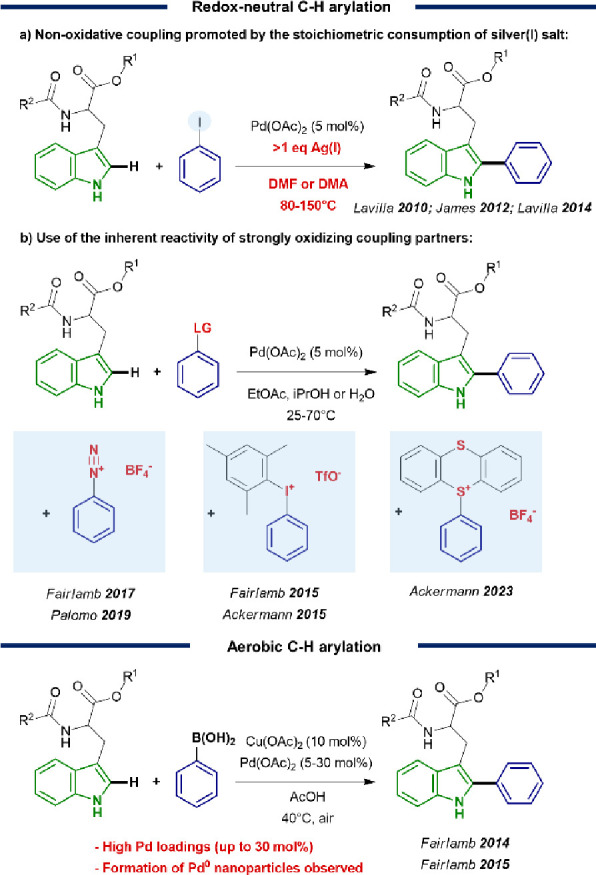

In contrast with the use of preinstalled or native functional groups, the cleavage of stable C–H bonds in tryptophan residues under mild temperature and in aqueous solvent is particularly challenging. Previous approaches that rely on the nonoxidative C–H/C-X coupling between reactive aryl iodides and the C–H bonds of tryptophan residues require thermal conditions in DMF or dimethylacetamide (DMA) as the solvent and the addition of stoichiometric silver salts (Figure 1a).23,29,31 Room temperature C–H couplings of tryptophan residues have been achieved through the use of reactive coupling partners, such as diazonium salts, strongly oxidizing periodinated salts, and recently thianthrenium salts (Figure 1b).25−27,32,33 While their inherent reactivity provides a strong driving force for the reaction, this approach is limited by the availability and stability of such preactivated starting materials and by the potential risk of unwanted side reactions. In contrast, harnessing molecular oxygen, which is abundantly present in air as the natural oxidative environment in biological systems, enables the use of readily available and often water-soluble boronic acid coupling partners (Figure 1c).24,26 In spite of these promising advances, the activation of molecular oxygen in air as the oxidant to drive the Pd-catalyzed tryptophan coupling has so far been linked to the formation of Pd0 clusters as a result of ineffective Pd0 to PdII reoxidation.24 This persistent problem necessitated the use of excessive Pd loadings up to 30 mol % to obtain complete conversion of the challenging reactants. In addition, the replacement of acetic acid by an aqueous solvent is highly desirable to enhance the overall sustainability of the chemical reaction and its future applicability in a biochemical context.

Figure 1.

Overview of reaction conditions previously applied in C–H arylation of tryptophan residues. (a,b) Redox-neutral arylations and (c) C–H arylations with O2.

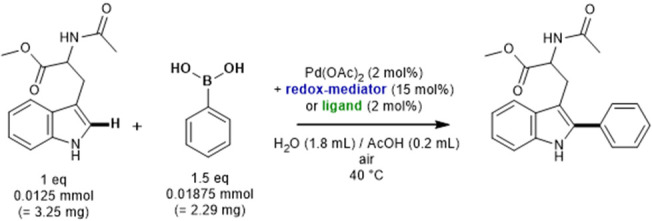

In this work, we report on the development of a Pd-based catalytic system that remains stable by enabling effective Pd(0) reoxidation by air in a mildly acidic aqueous environment. In order to activate dioxygen under ambient conditions and to overcome the rate-limiting oxidation of Pd(0), a broad screening of biocompatible redox mediators and ligands was performed, which ranged from organic redox-active cofactors to nontoxic metal ions for dioxygen activation. Like in biological dioxygen activation, iron(II) complexes emerged as effective redox mediators for the aerobic C–H activation of tryptophan residues. In addition, a screening of state-of-the-art nitrogen ligands was performed. In line with results obtained by Stahl and co-workers in aerobic oxidations in organic media,34−37 it was found that the use of a 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one ligand stabilizes the Pd-based catalytic system also in aqueous environment. The reaction kinetics were investigated using kinetic models, including nonsteady state models that also account for off-cycle Pd clustering. The enhanced stability of the ligated Pd(II) catalyst to counteract Pd(0) clustering was confirmed by in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy.

Results and Discussion

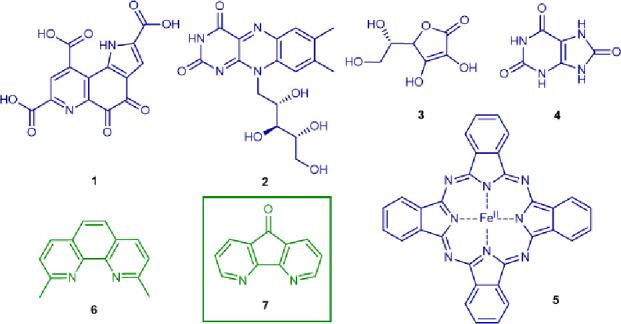

Optimization of the Catalytic System

To overcome the strong tendency for Pd(0) clustering or the necessity of highly reactive oxidants in previously reported catalytic systems, we hypothesized that an ineffective oxidation might be hampering catalytic turnover. Indeed, our investigation of the model reaction of N-acetyl tryptophan methyl ester and phenylboronic acid with the Pd loading limited to 2 mol % showed that the initial turnover rate is doubled when an enriched oxygen atmosphere (1 bar) is applied (Table 1, entries 1 and 2). Acetic acid was also used as a cosolvent (10 vol %) to promote acid-mediated reoxidation and as a source of acetate ligands for Pd(II). The product yield of N-acetyl-2-phenyltryptophan methyl ester nevertheless remained low. To enable the use of ambient partial oxygen pressure, the addition of potential redox mediators was tested as this had been successful in other oxidative Pd(0)/Pd(II) catalytic processes, such as the Wacker oxidation (Table 1, entries 3 and 4).38−43 However, most of the organic redox mediators were ineffective in the applied aqueous medium because of their insolubility. Water-soluble redox-active compounds from biological origin were investigated next, such as pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ), riboflavin (vitamin B2), ascorbic acid, and uric acid (Table 1, entries 5–8). The initial reaction yield was significantly increased with riboflavin, whereas ascorbic acid or uric acid had a detrimental effect on the reaction rate. Metal-based redox mediators were also tested as their chloride salts. In the series of CuI, MnII, and FeII, the latter ferrous chloride stood out and led to a remarkable increase in the initial reaction rate with 46% product yield after 3 h (Table 1, entries 9–12). Because of the efficiency of iron complexes and their known biological role in dioxygen activation, other complexes were also evaluated (Table 1, entries 13 and 14).44,45

Table 1. Screening of the Redox Mediators for the Reoxidation of Pd-Catalyzed Tryptophan Coupling in Air.

| entry | additive/ligand | yielda after 3 h (%) | yielda after 24 h (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | none | 14 | 20 |

| 2b | none | 23 | 60 |

| 3 | 1,4-benzoquinone | 8 | 44 |

| 4 | 2,5-di-t-butyl-1,4-benzoquinone | 16 | 46 |

| 5 | pyrroloquinoline quinone (1) | 2 | 3 |

| 6 | riboflavin (vitamin B2) (2) | 19 | 39 |

| 7 | ascorbic acid (3) | n.d.c | 2 |

| 8 | uric acid (4) | 7 | 11 |

| 9d | CuCl2 | 5 | 8 |

| 10d | Cu(OAc)2 | 11 | 25 |

| 11 | MnCl2·4H2O | 7 | 12 |

| 12 | FeCl2·4H2O | 50 | 66 |

| 13 | FeII(phthalocyanine) (5) | n.d. | 1 |

| 14 | FeIII(phthalocyanine) chloride | 15 | 25 |

| 15 | bipyridine | 1 | 3 |

| 16 | 6,6′-dimethylbipyridine | 7 | 11 |

| 17 | phenanthroline | 1 | 3 |

| 18 | neocuproine (6) | 8 | 14 |

| 19 | 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione | 3 | 9 |

| 20 | Ac-Ile-OH | 17 | 49 |

| 21 | Boc-Val-OH | 9 | 21 |

| 22 | 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one (7) | 35 | 92 |

| 23 | 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one + FeCl2·4H2O | 23 | 48 |

| 24 | 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one + 2,5-di-t-butyl-1,4-benzoquinone | 23 | 67 |

| 25 | 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one + Ac-Ile-OH | 38 | 79 |

| 26 | 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one + Boc-Val-OH | 21 | 66 |

Yields determined via HPLC with the corresponding reactant and product calibration curves.

Reaction performed in enriched oxygen environment (1 atm).

Not detected.

N-Arylated side product was detected.

In parallel, a screening of various bidentate N,N-ligands for aerobic Pd catalysis was performed with a L/Pd ratio of 1. Traditional ligand scaffolds, such as bipyridine and phenanthroline, resulted in catalyst inhibition (Table 1, entries 15–19). Two monoprotected amino acid ligands were also tested (Table 1, entries 20 and 21). While Boc-Val-OH was ineffective, the Ac-Ile-OH resulted in higher reaction yields in comparison with the “ligand-free” benchmark reaction without redox mediator. The addition of 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one ligand (Table 1, entry 22) led to the highest yield after 24 h. The addition of redox mediator or other ligands to the N,N-ligand shows that both are not compatible with each other, which results in lower reaction yields (Table 1, entries 23–26). As a control, the stability of the N-acetyl-tryptophan methyl ester model reactant in the aqueous solution of acetic acid at 40 °C was tested, yet no hydrolysis was observed via 1H NMR and HPLC after 24 h.

Effect of Functional Groups on Catalytic Performance

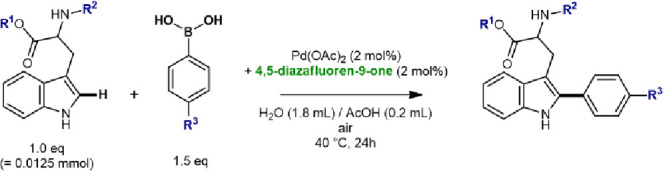

Next, we evaluated the influence of different functionalities on the tryptophan residues and boronic acid coupling partner. Replacement of the phenylboronic acid reactant with the corresponding pinacol ester or potassium trifluoroborate salt resulted in good conversions of the tryptophan reactant (Table 2, entries 1–3). The reaction tolerates a range of electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents on the para-position of the phenyl ring (Table 2, entries 4–9). Omission of the N-acetyl group in the tryptophan methyl ester reactant rendered the tryptophan residue unreactive (Table 2, entry 10). The reaction was successful in the presence of a coupled glycyl residue on the N-functionality, i.e. in the dipeptide NAc-Gly-Trp-OMe (Table 2, entry 11). The unprotected carboxylic acid group in N-acetyl tryptophan was also tolerated, which led to a moderate conversion (Table 2, entry 12). After amide coupling of the acid functionality with alanine methyl ester, the resulting dipeptide NAc-Trp-Ala-OMe converted smoothly (Table 2, entry 13). Furthermore, a peptide of six amino acid residues was tested as a comparison with a previously reported catalytic system24 to demonstrate that the required Pd loading can be strongly reduced (Table 2, entry 14).

Table 2. Evaluation of Functional Groups on the Catalytic Performance.

| entry | R1 | R2 | R3 | conversion (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Me | Ac | H | 92 (62)b |

| 2c | Me | Ac | H | 73 |

| 3d | Me | Ac | H | 72 |

| 4 | Me | Ac | Me | 60 |

| 5 | Me | Ac | OMe | 83 |

| 6 | Me | Ac | F | 76 |

| 7 | Me | Ac | OH | 82 |

| 8 | Me | Ac | CH2OH | 98 |

| 9 | Me | Ac | NMe2 | 82 |

| 10 | Me | H (−NH3+) | H | <1 |

| 11 | Me | NAc-Gly- | H | 50 |

| 12 | H (−COOH) | Ac | H | 53 |

| 13 | –Ala-OMe | Ac | F | 73 |

| 14 | NAcTrpLysLeuValGlyAlaOH | F | 74 (95)e | |

Conversion of the tryptophan reactant with 2 mol % Pd and atmospheric oxygen pressure, as determined via HPLC using a calibration curve. The major product peak was identified as the arylated product via LC-MS (see the Supporting Information).

Reaction performed on a 1 mmol scale (0.0375 M) in an open flask.

Reaction with phenylboronic acid pinacol ester (1.5 equiv).

Reaction with potassium phenyltrifluoroborate (1.5 equiv).

Reaction performed with 6 mol % Pd(OAc)2/4,5-diazafluoren-9-one.

Kinetic Modeling of the Catalytic Cycle

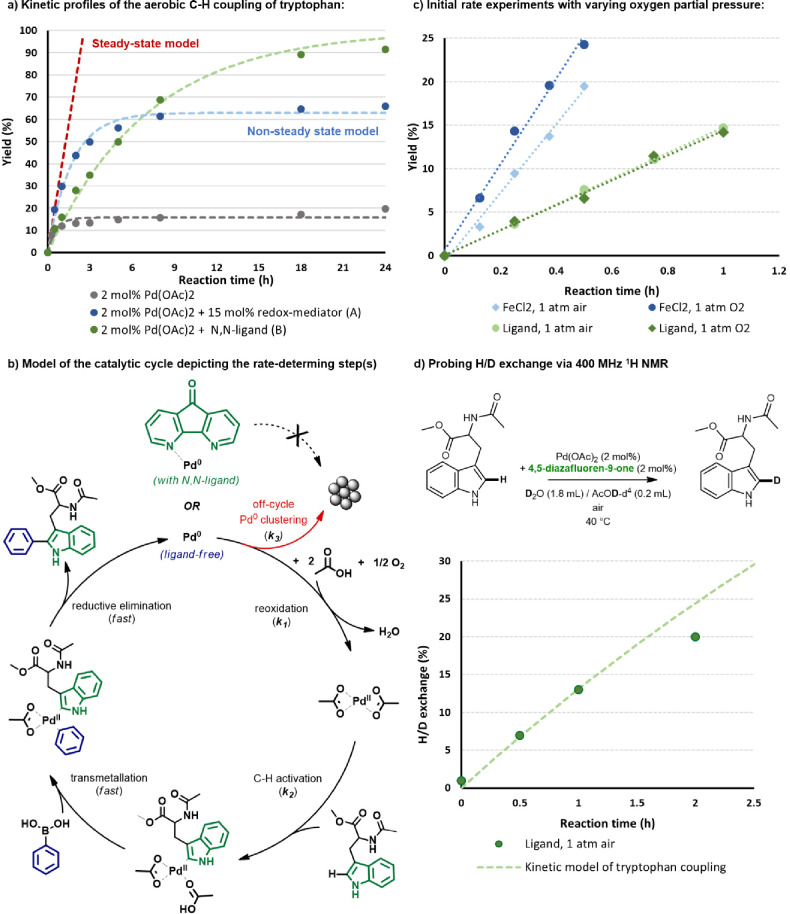

Our catalyst optimization studies revealed a trade-off between the (initial) activity and the stability of the Pd-based catalytic system. While the FeCl2 redox mediator led to a highly active catalytic system at short reaction times, the rate stagnated overnight. Interestingly, the alternative approach with 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one led to lower yields initially but was more robust as it yielded a complete conversion after longer reaction time. The kinetic behavior was further investigated by recording the corresponding time profiles of the reactions over a range of 24 h (Figure 2a). The reaction without a redox mediator or ligand immediately stagnated at a yield below 20%. The addition of FeCl2 postponed the deactivation, and up to 60% yield was obtained. While the initial rate was slower with the N,N-ligand, the reaction yield steadily increased up to 92% yield after 24 h.

Figure 2.

Kinetic study of the C–H coupling of tryptophan residues in water. (a) Experimental kinetic profiles and fitted kinetic models. (b) Initial reaction rate measurements in air or O2. (c) Plausible catalytic cycle used in the derivation of kinetic models. (d) C–H deuteration experiments monitored via 400 MHz NMR.

To interpret these kinetic profiles, we have modeled the catalytic cycle (Figure 2b). Related C–H coupling reactions in literature show that the starting Pd(OAc)2 complex can undergo C–H activation of the indole C2 core via a “concerted metalation–deprotonation” (CMD) mechanism mediated by the acetate ligand. Next, a transmetalation step occurs with phenylboronic acid. The C–C bond between the phenyl and tryptophanyl moieties is formed in a reductive elimination step. Finally, the resulting Pd(0) needs to be reoxidized to Pd(II) with oxygen as the terminal oxidant. However, the Pd(0) intermediate is prone to clustering, which can lead to the formation of inactive Pd(0) clusters. The initial reaction rates were measured in either atmospheric air or enriched oxygen environment (Figure 2c). These kinetic experiments revealed that the initial reaction rate was promoted by increasing the oxygen pressure in the presence of FeCl2, whereas with the N,N-ligand the rate remained unaffected by the increase in partial oxygen pressure. The first-order reaction profile indicates that the C–H activation of the tryptophan reactant is in this case rate-determining rather than the reoxidation of Pd(0).

On the basis of these kinetic profiles, the integrated rate equations were derived (Supporting Information). Under the steady-state assumption, that is, in the case of the rate of Pd clustering being much smaller than that of C–H activation (k3 ≪ k1), pseudo-zero-order kinetics are expected for the conditions with redox mediator, and first-order kinetics are expected in the N,N-ligand-based catalytic system. In the latter case, the model satisfactorily explained the full time profile of the reaction yield. Because of the observed stagnation of the reaction in the former case, it is clear that the rate of Pd(0) deactivation (k3) cannot be neglected. The nonsteady state rate equations were derived (see the Supporting Information section 2) and included an off-cycle Pd(0) clustering step in which inactive Pd(0) is irreversibly accumulated.

The change from a slow reoxidation to a rate-determining C–H activation in the presence of the ligand was further supported by H/D exchange studies. The C–H activation step was monitored via in situ1H NMR in D2O/d4-AcOD solvent, which showed a decrease in intensity of the C–H bond on the C2 position of the N-acetyl-tryptophan methyl ester reactant over the initial course of the reaction (see the Supporting Information section 3). The rates of H/D exchange were compared with the previously measured reaction rate for the C–H coupling with phenylboronic acid in the presence of the ligand-based catalytic system (Figure 2d). An initial reaction rate is found in agreement with the overall reaction rate for the initial reaction time of 1 h, which suggests that the C–H activation of the tryptophan reactant is in this case, indeed, the step that limits the overall rate of the coupling reaction. A difference between the rate of H/D exchange and C–H arylation emerges after these initial reaction times since the deuterated product is also a suitable reactant that can be activated by the Pd catalyst, thereby causing a deviation from strict first-order kinetics.

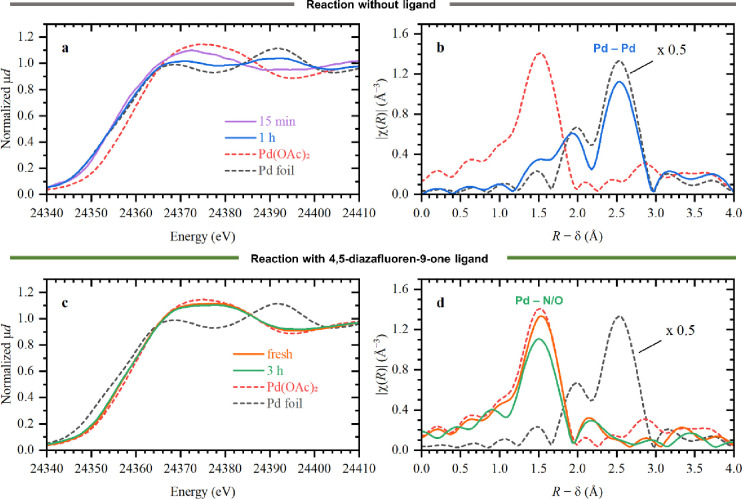

Probing Catalyst Deactivation via In Situ XAS

In view of the importance of the resting state and ligand coordination to maintain the stability of the catalyst under mild aqueous reaction conditions in air, we proceeded with an in situ XAS study. X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra at Pd K-edge during the coupling reaction directly probe the oxidation state of palladium, while the extended X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy (EXAFS) data track the changes in its local coordination. The spectra were acquired for the first hours of the reaction at 40 °C under ambient atmosphere, both with and without the addition of ligand (Figure 3). The XANES spectra clearly indicated the reduction to Pd(0) in the absence of ligand already after 15 min of reaction (Figure 3a), while the EXAFS spectra showed an increasing contribution at ca. 2.5 Å corresponding to Pd–Pd clustering (Figure 3b). The absolute intensity of the Pd–Pd peak in EXAFS data was almost two times lower than that of bulk palladium (dashed black line) because of the lower coordination number in small Pd clusters. In contrast, the resting state of the Pd(4,5-diazafluoren-9-one)(OAc)2 complex remained in the Pd(II) state even after 3 h of reaction (Figure 3c) with no evidence of clustering in EXAFS data (Figure 3d).

Figure 3.

XANES (a,c) and EXAFS (b,c) data for the catalyst without (a,b) and with (c,d) ligand at different times of reaction (solid colored lines) in comparison with reference Pd foil (dashed black) and Pd(II) acetate (dashed red).

Conclusions

The results discussed in this paper demonstrate the importance of catalyst stability in synthetic Pd catalysis using air as a mild oxidant. Two strategies were pursued, which either relied on a redox mediator or a ligand-based approach, through experimental screening and in-depth analysis via a combination of kinetic studies and in situ spectroscopy. While the rate of C–H activation is lower upon addition of 4,5-diazafluoren-9-one for the studied C–H arylation of N-acetyl tryptophan methyl ester, the resting state of the catalytic system shifts toward a Pd(II) rather than a Pd(0) intermediate, which enhances the stability of the catalyst. The results show that catalyst deactivation was successfully overcome in the C–H coupling of tryptophan in spite of the challenging reaction conditions with water as the solvent and air as the terminal oxidant. This study revealed useful concepts for the future development of other sustainable Pd-based catalytic systems for oxidative reactions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Gert Steurs for support with the NMR experiments and to Bart Van Huffel for assistance with LC-MS measurements. We also thank Karen Aerts and Dr. Nada Savić for their help with CD spectroscopy.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.4c01699.

Experimental section, mathematical derivation of kinetic models, and information on the acquisition of XAS spectra (PDF)

Author Contributions

I.B. conceived the research concept and performed the experiments. C.V. and H.V.D. assisted with the research experiments. O.U., A.S., and A.B. performed the analysis via XAS and interpreted the resulting spectra. D.D.V. supervised the project and contributed to the research concept. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

The research leading to these results has received funding from the NMBP-01-2016 Program of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Framework Program H2020/2014-2020/under grant agreement no. [720996]. The authors are also grateful for the access to SLS beamtime provided by the European Union as part of the Horizon Europe call HORIZON-INFRA-2021-SERV-01 under grant agreement number 101058414 and cofunded by the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) under contract number 22.00187. I.B. and H.V.D. are grateful to FWO for funding (1291724N and 1S31822N, respectively). D.D.V. is grateful to KU Leuven for support in the frame of the CASAS Metusalem project and to Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) for project funding (G0781118N and G0D0518N).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Tang S.; Vincent G. Natural Products Originated from the Oxidative Coupling of Tyrosine and Tryptophan: Biosynthesis and Bioinspired Synthesis. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27, 2612. 10.1002/chem.202003459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S.; Wang Z.; Wang B.; Hou B.; Cheng J.; Bai T.; Zhang Y.; Wang W.; Yan L.; Zhang J. Expanding the application of tryptophan: Industrial biomanufacturing of tryptophan derivatives. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1099098. 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1099098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn W. S.; Nims E.; O’Connor S. E. Reengineering a Tryptophan Halogenase To Preferentially Chlorinate a Direct Alkaloid Precursor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 19346. 10.1021/ja2089348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L.; Bilal M.; Luo H.; Zhao Y.; Iqbal H. M. N. Metabolic Engineering and Fermentation Process Strategies for L-Tryptophan Production by Escherichia coli. Processes 2019, 7, 213. 10.3390/pr7040213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Barkley M. D. Toward Understanding Tryptophan Fluorescence in Proteins. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 9976. 10.1021/bi980274n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghisaidoobe A. B. T.; Chung S. J. Intrinsic Tryptophan Fluorescence in the Detection and Analysis of Proteins: A Focus on Förster Resonance Energy Transfer Techniques. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 22518. 10.3390/ijms151222518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivian J. T.; Callis P. R. Mechanisms of Tryptophan Fluorescence Shifts in Proteins. Biophys. J. 2001, 80, 2093. 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barik S. The Uniqueness of Tryptophan in Biology: Properties, Metabolism, Interactions and Localization in Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8776. 10.3390/ijms21228776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felczak M. M.; Simmons L. A.; Kaguni J. M. An Essential Tryptophan of Escherichia coli DnaA Protein Functions in Oligomerization at the E. coli Replication Origin. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 24627. 10.1074/jbc.M503684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer M.; Chang C.-H.; Stevens F. J. The functions of tryptophan residues in membrane proteins. Protein Eng. 1992, 5, 213. 10.1093/protein/5.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B.; Nussinov R. Trp/Met/Phe Hot Spots in Protein-Protein Interactions: Potential Targets in Drug Design. Curr. Topics Med. Chem. 2007, 7, 999–1005. 10.2174/156802607780906717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen O. S.; Greathouse D. V.; Providence L. L.; Becker M. D.; Koeppe I. R. E. Importance of Tryptophan Dipoles for Protein Function: 5-Fluorination of Tryptophans in Gramicidin A Channels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 5142. 10.1021/ja980182l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Vinogradova E. V.; Spokoyny A. M.; Buchwald S. L.; Pentelute B. L. Arylation Chemistry for Bioconjugation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4810. 10.1002/anie.201806009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniev O.; Wagner A. Developments and recent advancements in the field of endogenous amino acid selective bond forming reactions for bioconjugation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 5495. 10.1039/C5CS00048C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adakkattil R.; Thakur K.; Rai V. Reactivity and Selectivity Principles in Native Protein Bioconjugation. Chem. Rec. 2021, 21, 1941. 10.1002/tcr.202100108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGruyter J. N.; Malins L. R.; Baran P. S. Residue-Specific Peptide Modification: A Chemist’s Guide. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 3863. 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy N. C.; Kumar M.; Molla R.; Rai V. Chemical methods for modification of proteins. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 4669. 10.1039/D0OB00857E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deprez N. R.; Kalyani D.; Krause A.; Sanford M. S. Room Temperature Palladium-Catalyzed 2-Arylation of Indoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 4972. 10.1021/ja060809x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane B. S.; Sames D. Direct C–H Bond Arylation: Selective Palladium-Catalyzed C2-Arylation of N-Substituted Indoles. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 2897. 10.1021/ol0490072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemoets H. P.; et al. Mild and selective base-free C–H arylation of heteroarenes: experiment and computation. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 1046. 10.1039/C6SC02595A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrasseur N.; Larrosa I. Room Temperature and Phosphine Free Palladium Catalyzed Direct C-2 Arylation of Indoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 2926. 10.1021/ja710731a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckers I.; Krasniqi B.; Kumar P.; Escudero D.; De Vos D. Ligand-Controlled Selectivity in the Pd-Catalyzed C–H/C–H Cross- Coupling of Indoles with Molecular Oxygen. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 2435. 10.1021/acscatal.0c04893. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Rodriguez J.; Albericio F.; Lavilla R. Postsynthetic Modification of Peptides: Chemoselective C-Arylation of Tryptophan Residues. Chem.—Eur. J. 2010, 16, 1124. 10.1002/chem.200902676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T. J.; Reay A. J.; Whitwood A. C.; Fairlamb I. J. S. A mild and selective Pd-mediated methodology for the synthesis of highly fluorescent 2-arylated tryptophans and tryptophan-containing peptides: a catalytic role for Pd0 nanoparticles?. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 3052. 10.1039/C3CC48481E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y.; Bauer M.; Ackermann L. Late-Stage Peptide Diversification by Bioorthogonal Catalytic C-H Arylation at 23°C in H2O. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015, 21, 9980. 10.1002/chem.201501831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reay A. J.; Williams T. J.; Fairlamb I. J. S. Unified mild reaction conditions for C2-selective Pd-catalysed tryptophan arylation, including tryptophan-containing peptides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 8298. 10.1039/C5OB01174D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplaneris N.; Puet A.; Kallert F.; Pöhlmann J.; Ackermann L. Late-stage C-H Functionalization of Tryptophan-Containing Peptides with Thianthrenium Salts: Conjugation and Ligation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202216661 10.1002/anie.202216661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrey M. J.; Holmes A.; Perry C. C.; Cross W. B. C–H Olefination of Tryptophan Residues in Peptides: Control of Residue Selectivity and Peptide–Amino Acid Cross-linking. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 7902. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H.; Limberakis C.; Liras S.; Price D.; James K. Peptidic macrocyclization via palladium-catalyzed chemoselective indole C-2 arylation. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 11644. 10.1039/c2cc36962a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preciado S.; Mendive-Tapia L.; Albericio F.; Lavilla R. Synthesis of C-2 Arylated Tryptophan Amino Acids and Related Compounds through Palladium-Catalyzed C–H Activation. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 8129. 10.1021/jo400961x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendive-Tapia L.; Preciado S.; García J.; Ramón R.; Kielland N.; Albericio F.; Lavilla R. New peptide architectures through C–H activation stapling between tryptophan–phenylalanine/tyrosine residues. Nature Comm. 2015, 6, 7160. 10.1038/ncomms8160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Rizquez C.; Abian O.; Palomo J. M. Site-selective modification of tryptophan and protein tryptophan residues through PdNP bionanohybrid-catalysed C–H activation in aqueous media. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 12928. 10.1039/C9CC06971B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reay A. J.; Hammarback L. A.; Bray J. T. W.; Sheridan T.; Turnbull D.; Whitwood A. C.; Fairlamb I. J. S. Mild and Regioselective Pd(OAc)2-Catalyzed C–H Arylation of Tryptophans by [ArN2]X, Promoted by Tosic Acid. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 5174. 10.1021/acscatal.6b03121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diao T.; Wadzinski T. J.; Stahl S. S. Direct aerobic a,b-dehydrogenation of aldehydes and ketones with a Pd (TFA)2/4,5-diazafluorenone catalyst. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 887. 10.1039/C1SC00724F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A. N.; Meyer E. B.; Stahl S. S. Regiocontrolled aerobic oxidative coupling of indoles and benzene using Pd catalysts with 4,5-diazafluorene ligands. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 10257. 10.1039/c1cc13632a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White P. B.; Jaworski J. N.; Zhu G. H.; Stahl S. S. Diazafluorenone-Promoted Oxidation Catalysis: Insights into the Role of Bidentate Ligands in Pd-Catalyzed Aerobic Aza-Wacker Reactions. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 3340. 10.1021/acscatal.6b00953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A. N.; White P. B.; Guzei I. A.; Stahl S. S. Allylic C-H Acetoxylation with a 4,5-Diazafluorenone-Ligated Palladium Catalyst: A Ligand-Based Strategy To Achieve Aerobic Catalytic Turnover. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 15116. 10.1021/ja105829t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A. N.; Stahl S. S. Overcoming the Oxidant Problem: Strategies to Use O2 as the Oxidant in Orgaometallic C-H Oxidation Reactions Catalyzed by Pd (and Cu). Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 851. 10.1021/ar2002045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.; Weinstein A. B.; White P. B.; Stahl S. S. Ligand-Promoted Palladium-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidation Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2636. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäckvall J.-E.; Hopkins B. R.; Grennberg H.; Mader M. M.; Awasthi A. K. Multistep Electron Transfer in Palladium-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidations via a Metal Macrocycle-Quinone System. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 5160. 10.1021/ja00169a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar C. A.; Flesch K. N.; Haines B. E.; Zhou P. S.; Musaev D. G.; Stahl S. S. Tailored quinones support high-turnover Pd catalysts for oxidative C–H arylation with O2. Science 2020, 370, 1454. 10.1126/science.abd1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piera J.; Bäckvall J.-E. Catalytic Oxidation of Organic Substrates by Molecular Oxygen and Hydrogen Peroxide by Multistep Electron Transfer—A Biomimetic Approach. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3506. 10.1002/anie.200700604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W.; Jiang H. Palladium-Catalyzed Oxidation of Unsaturated Hydrocarbons Using Molecular Oxygen. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1736. 10.1021/ar3000508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costas M.; Mehn M. P.; Jensen M. P.; Que L. Dioxygen Activation at Mononuclear Nonheme Iron Active Sites: Enzymes, Models, and Intermediates. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 939. 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S.; Lee Y. M.; Ray K.; Nam W. Dioxygen activation chemistry by synthetic mononuclear nonheme iron, copper and chromium complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 334, 25. 10.1016/j.ccr.2016.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.