Abstract

Background:

Standard treatment for locally-advanced cervical cancer is chemo-radiation, but many patients relapse and die of distant metastatic disease. OUTBACK was designed to determine the effects on survival of adjuvant chemotherapy after chemo-radiation.

Methods:

OUTBACK was an international, randomised phase 3, intergroup trial. Eligible participants had locally-advanced cervical cancer (FIGO 2008 stage IB1 & node positive, IB2, II, IIIB or IVA) suitable for chemo-radiation. Participants were randomly assigned to standard cisplatin-based chemo-radiation, or standard cisplatin-based chemo-radiation followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with 4 cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel. The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS) at 5 years. Efficacy was assessed in the intention-to-treat population (ie, all eligible patients who were randomly assigned to treatment) and safety was assessed in all participants in the control group who started chemoradiotherapy and all participants in the experimental group who received at least one dose of adjuvant chemotherapy. The study is registered on ANZCTR.org.au; ACTRN12610000732088.

Findings:

919 of 926 participants recruited from April 2011 to June 2017 were eligible and included in the primary analysis: 463 assigned adjuvant chemotherapy, 456 control. Median (IQR) age was 46 (37–55) years. Ethnicity was 663 (72%). Adjuvant chemotherapy was started in 361 (78%) participants assigned it. Median follow-up was 60 months (IQR 45–65). OS at 5 years was similar among those assigned adjuvant chemotherapy versus control (105 vs 116 deaths, survival rate 72% (95%CI: 67–76%) vs 71% (95%CI: 66–75%), difference 1%, 95% CI −6 to +7; P=0·81). The hazard ratio for OS was 0·90 (95% CI 0·70–1·17). AE of grade 3–5 within a year of randomisation occurred in 81% assigned adjuvant chemotherapy versus 62% assigned control, but there were no differences in AEs beyond 1-year post randomisation. The most common clinically significant grade 3–4 adverse events were decreased neutrophils in 71 (20%) assigned adjuvant chemotherapy vs 34 (8%) control, and anaemia in 66 (18%) assigned adjuvant chemotherapy vs (34 (8%) control. Serious adverse events occurred in 107 (30%) assigned adjuvant chemotherapy versus 98 (22%) control. There were no treatment-related deaths. Patterns of disease recurrence were similar in the two groups.

Interpretation:

Adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy given after standard cisplatin-based chemo-radiation for unselected locally-advanced cervical cancer increased short-term toxicity but did not improve OS, so should not be given in this setting.

INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer is a significant global health issue with more than half a million women diagnosed worldwide each year. In developed countries the incidence has decreased dramatically following the widespread introduction of cervical screening programs1. Unfortunately, many women still die from cervical cancer, particularly in low and middle income countries, making it the 4th leading cause of cancer-related death in women worldwide2.

For women presenting with early-stage disease, surgical approaches or treatment with chemo-radiation provide excellent outcomes. However, a significant percentage of women, particularly those who have not participated in screening programs, present with more locally-advanced disease and have much lower cure rates3.

The use of chemotherapy concurrent with radiation (chemo-radiation) for cervical cancer is proven to improve survival and became established as standard of care in 19994–6. Subsequently, a meta-analysis of individual patient data from 18 randomised trials found that adding concurrent chemotherapy to radiation increased the 5-year overall survival rate by 6% (60 vs 66%; HR 0.81; 95% CI, 0.71 – 0.91)7. In this meta-analysis the 5-year disease-free survival rate of 58% in the chemo-radiation group still leaves many women not cured with this treatment, with the majority of deaths due to the development of distant metastatic disease8.

We hypothesized that giving additional adjuvant chemotherapy following chemo-radiation would reduce distant relapses and thereby improve overall survival. Indeed, the meta-analysis demonstrated larger survival benefits in 2 trials that gave further cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy following chemo-radiation. Subsequently, a randomised South American trial compared standard cisplatin-based chemo-radiation versus the same radiotherapy with concurrent cisplatin and gemcitabine, followed by 2 cycles of adjuvant cisplatin and gemcitabine. The trial reported a 9% improvement in both progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) at 3 years, and was highly influential in changing practice at some centers9.

However, criticisms of the trial including the limited follow-up time of 3 years, as well as significantly increased toxicity in the additional chemotherapy arm, precluded its widespread acceptance as standard treatment. A recent analysis of the United States National Cancer Database suggested that one in ten patients were receiving multi-agent adjuvant chemotherapy in addition to chemo-radiation with no survival benefit. Concerningly, there was also a lower rate of brachytherapy completion in those treated with adjuvant chemotherapy10. Consequently, the Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup (GCIG) envisaged OUTBACK as a confirmatory trial. OUTBACK aimed to test the potential benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy following primary chemo-radiation for locally-advanced cervical cancer.

METHODS

Study design and participants

OUTBACK (ANZGOG 0902, RTOG 1174, NRG 0274) is an international, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial, comparing cisplatin-based pelvic chemo-radiation versus the same chemo-radiation followed by 4 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel for the treatment of locally-advanced cervical cancer. The trial was performed globally at hospital sites (listed in Appendix) under the auspices of the GCIG, led by the Australia and New Zealand Gynaecological Oncology Group (ANZGOG), and coordinated by the National Health and Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Centre, The University of Sydney (NHMRC CTC) in Australia. Participating cooperative groups (countries) included NRG (USA, Saudi Arabia, Canada, China), and Singapore. OUTBACK is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01414608) and the Australia New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ACTRN12610000732088).

Participants had locally-advanced cervical cancer suitable for primary treatment with chemo-radiation. Eligibility criteria included: age 18 years or older, histologically confirmed squamous cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, or adenocarcinoma that was FIGO 2008 stage 1B1 disease with nodal involvement, or stage 1B2, II, IIIB or IVA; WHO performance status 0–2; adequate bone marrow and organ function as per the protocol (Appendix). Key exclusion criteria were: prior hysterectomy; para-aortic nodal involvement above the level of the common iliac nodes or above L3/L4 (if biopsy proven, positive on FDG-PET, or ≥ 15mm short axis diameter on CT); stage IIIA disease or disease assessed at presentation as requiring interstitial brachytherapy. All participants had baseline imaging with computerised tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis (CT), as well as PET, PET/CT, ± MRI pelvis if available at the treating centre.

The protocol was approved by all participating groups and relevant institutional ethics review committees, and all participants gave signed, written, informed consent. The trial was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Randomisation and masking

Participants were randomly assigned to treatment with either: standard chemo-radiation (control group) or standard chemo-radiation plus adjuvant chemotherapy (adjuvant chemotherapy group), using the method of minimization. Randomisation was 1:1 and performed by sites through a web-based system with stratification by pelvic or common iliac nodal involvement (Yes, No, or Unknown); requirement for extended-field radiation therapy (Yes or No); FIGO 2008 Stage IB / IIA, or IIB, or IIIB / IVA; age <60 or ≥60 years; treating hospital/site. Nodal involvement was defined as any pelvic or common iliac nodes which were either PET positive, had a short axis diameter of >15mm on CT and/or MRI, or were histologically positive on surgical sampling. Participants and investigators were not masked to treatment allocation given the alopecia associated with paclitaxel chemotherapy in the intervention arm.

Procedures

Participants in both arms were to be treated with standard external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) to the pelvis plus brachytherapy. Cisplatin was given concurrently during radiation at a dose of 40mg/m2 weekly for 5 doses. Cisplatin was omitted or the dose reduced to 30mg/m2 for toxicities as specified in the protocol. External radiation continued if cisplatin was withheld. Participants who had not recovered from toxicities within 21 days did not receive further cisplatin.

The standardised radiation therapy used megavoltage energy with a source to surface distance (SSD) of 80 cm or greater. Use of linear accelerators or Cobalt 60 units was allowed. A four-field box technique with parallel-opposed AP/PA and two opposing lateral fields was recommended and defined in the protocol; intensity-modulated radiotherapy was not allowed. All participants were to be treated with 45–50.4 Gy EBRT delivered in fractions of 1.8 Gy to the whole pelvis. Those with common iliac nodal disease were treated with 45 Gy in 1.8 Gy fractions of extended field radiation therapy (EFRT). Parametrial or nodal boost was allowed at the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist.

The external beam target volume was to encompass, with adequate margins, the gross tumour volume (GTV) including the primary cervical tumour, any gross extension, and any grossly-involved lymph nodes. The clinical target volume included the GTV, parametria, uterus, upper half of the vagina; the internal, external, and distal common iliac nodes; and the utero-sacral ligaments.

Intracavitary brachytherapy was delivered with standard applicators using either tandem and ovoids, or tandem and ring. Brachytherapy could be delivered either as high-dose rate (HDR) or low-dose rate (LDR) to deliver a total dose to the primary tumour of 80 – 86.4 Gy (EQD2), including EBRT and brachytherapy. Brachytherapy could be prescribed either to point A, or to image-guided target volumes.

Radiation quality assurance was monitored by the Imaging and Radiation Oncology Core (IROC) administered by the American College of Radiology. Simulation films of digitally reconstructed radiographs (for all treatment fields and phases of treatment) were submitted and reviewed for the first 2 participants at each participating site. If these were deemed acceptable, then subsequent data from every 10th patient was submitted for review. Centers with unsatisfactory results were required to send more cases for review until deemed compliant with the protocol.

Within 4 weeks of completing radiation therapy, including brachytherapy, and following recovery from toxicities, patients assigned adjuvant chemotherapy were to be treated with 4 cycles of 3-weekly adjuvant chemotherapy using carboplatin AUC 5 and paclitaxel 155 mg/m2. Hospira provided paclitaxel for sites in Australia and New Zealand Before starting adjuvant chemotherapy, the toxicities of the concomitant chemo-radiation (regardless of whether completed) were required to be resolved to less than CTCAE grade two (except for lymphocyte count). Chemotherapy doses could be delayed for up to 2 weeks or doses reduced according to toxicities as described in detail within the protocol (Appendix).

After treatment, participants were followed every 3 months for the first 2 years, and then every 6 months for a minimum of 5 years. Response rate using RECIST v1.1 was determined by the site investigator in those with measurable disease, based on CT and/or MRI pelvis at baseline and repeated 6 months after randomisation and/or if relapse was suspected. If PET or PET/CT was done at baseline, then it was repeated 4–6 months after completing chemo-radiation. Metabolic PET response was assessed using PERCIST version 1.0. There was no restriction on treatment given for relapse, which was as per investigator discretion.

Adverse events were classified and graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events [NCI CTCAE] Version 4.0, and assessed face-to-face weekly during chemo-radiation, prior to each cycle of adjuvant chemotherapy, at the end of study treatment, then 3- monthly to 2 years, and then 6-monthly to 5 years from randomisation. HRQL was assessed at baseline, at the end of chemo-radiation, prior to each cycle of adjuvant chemotherapy, and then at each follow-up visit to 36 months after randomisation.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was overall survival at 5 years, defined as the time from the date of randomisation to death from any cause or censoring at last known follow-up. The secondary endpoints were: PFS at 3 years and at 5 years; adverse events within 1 year of randomisation (acute) and beyond 1 year (late); the patterns of disease recurrence; radiation protocol compliance; and aspects of self-reported health-related quality of life (HRQL). A tertiary endpoint was complete metabolic response by PERCIST 1.0 criteria on a PET scan performed 4 – 6 months after completion of chemo-radiation. PFS was defined as the time from the date of randomisation to tumour progression or recurrence at any site, commencement of non-protocol anti-cancer therapy, or death from any cause, whichever was earlier. Recurrences were analysed according to the first site of recurrence, and defined as either persistent disease (present at treatment completion), locoregional or distance recurrence. All endpoints were determined by investigators at the study sites. Several HRQL questionnaires were used; in this paper, we report the global health status/quality of life scale from the EORTC QLQ-C30. Due to the large amount of HRQL data collected a comprehensive analysis of HRQL will be reported elsewhere11. A further secondary endpoint of radiation protocol compliance and exploration of its association with clinical outcomes will also be reported elsewhere.

Statistical analysis

Sample size: OUTBACK was originally powered to provide 80% power with a two-sided type 1 error rate of 5% if the true absolute difference in 5-year survival rates was 10% (from 63% to 73%). This required 780 participants assuming 3 years accrual plus 3 years of additional follow-up. An Independent Data and Safety-Monitoring Committee (IDSMC) monitored the study and advised the trial steering committee on the safety and feasibility of the study. Planned interim analysis was positive for efficacy and so the trial continued. In 2016, after consideration of the lower-than-expected PFS rate, and significant non-adherence to prescribed adjuvant chemotherapy, the IDSMC recommended that the sample size be increased in a protocol amendment.

The revised sample size of 828 patients, (414/group), provided 80% power with a two-sided type 1 error rate of 5% if the true absolute difference in 5-year survival rates was 8% (from 72–80%). This corresponded to a hazard ratio of 0.68, and assumed 48 months for accrual plus 42 months of additional follow-up. The study sample size was increased to 900 (450/group) to allow for non-adherence and loss to follow-up.

All statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 and as per the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP in Appendix). Effectiveness analyses used the intention to treat (ITT) population, comprising all eligible participants analysed according to their randomised treatment allocation. The overall safety population comprised eligible participants in the control group who started chemo-radiation, and eligible participants in the experimental group who received at least one dose of adjuvant chemotherapy, with participants analysed according to their randomly allocated treatment group. The ITT population was used for analyses of sites of disease recurrence. The secondary endpoints of acute and long-term safety were defined according to worst grade experienced within one year after randomisation and worst grade experienced at any time after one year, respectively. For these analyses, participants in the safety population with no recorded safety assessment after one year post-randomisation were excluded from the analyses of long-term adverse events. Objective tumour responses according to RECIST 1.1 were calculated in participants with measurable disease (per RECIST 1.1 criteria) at baseline.

The primary outcome of OS and its 95% CI at 5 years was estimated in each randomised treatment arm using the Kaplan-Meier method and its standard error estimated using the Greenwood method. An unstratified log-rank test was used to quantify the evidence for overall survival differences between the two randomised groups.

Proportional hazards regression models were used to calculate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using the method of Li et al. based on Martingale residuals12. Calculations for PFS used the same method. For survival outcomes, participants who had not experienced the event of interest were censored at their last known event-free date.

Tests of the proportional hazards assumption showed no evidence of non-proportionality for OS (P=0.36), but some evidence for PFS (P=0.008). However, there were 20 participants with persistent disease (5 assigned adjuvant chemotherapy, 15 assigned chemo-radiation alone) whose progression was set to have occurred 0.5 days after randomisation. When these participants were removed, the proportional hazards assumption was upheld (P=0.07) but all participants are included in all survival analyses reported unless otherwise indicated.

Given significant rates of non-adherence in the adjuvant chemotherapy arm, a pre-specified sensitivity analysis for OS and PFS was performed based on those who did or did not complete the initial chemo-radiation (see SAP section 3.8.2), using the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate survival outcomes and a proportional hazards regression model with randomised treatment, completion/non-completion of chemoradiation and their interaction as predictors. Non-completion of chemoradiation was the strongest predictor of not starting any adjuvant chemotherapy as we have previously reported13. Specific sub-group analyses according to pre-specified baseline characteristics, (nodal involvement, requirement for extended-field radiotherapy, FIGO 2008 stage, age, country, smoking status) and one post-hoc predictor (tumour histology), were performed for the outcomes of OS and PFS. The analyses Cox proportional hazards regression models including terms for the subgroup, randomised treatment group, and their interaction.

A pre-specified analysis of cervical-cancer specific mortality was described and compared between randomised treatment groups using Gray’s method and hazard ratio with confidence interval calculated using the Fine and Gray method, after blinded central adjudication of the cause of death before the analysis was performed. For cervical cancer specific mortality, death from other causes was treated as a competing risk and patients alive at last follow up were censored. A pre-specified analysis in participants who underwent a PET scan 168 to 365 days after randomisation explored association between PET response (complete metabolic response (CMR) vs any other result (non-CMR, progressive metabolic disease, result unknown)) and the outcomes of OS and PFS. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate survival estimates separately for participants with and without CMR in each randomized treatment group. Proportional hazards regressions model tested for interaction between CMR and randomized treatment and calculated hazard ratios for the effect of treatment and CMR in a multivariable model. Changes in mean HRQL scores from baseline for those with at least one follow-up questionnaire were compared between groups using two-sample t-tests and described by difference with 95% confidence intervals. Categorical outcomes were compared using chi-square tests.

Role of the funding source

The funding bodies had no role in study design, data collection, data interpretation or analysis, or writing of the report.

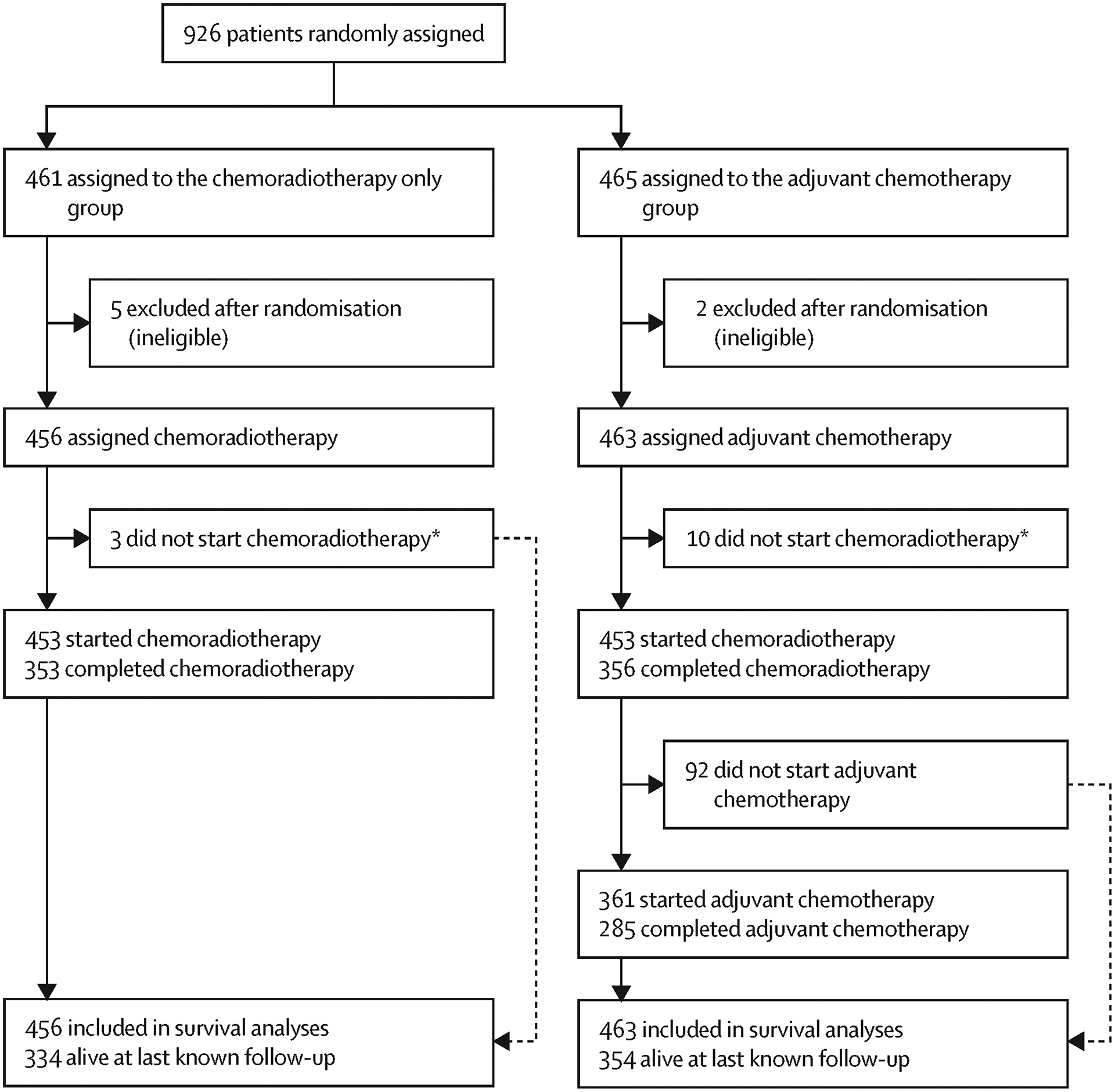

RESULTS

We recruited and randomised 926 women from 7 countries between 15 April 2011 and 26 June 2017. Seven participants found to be ineligible after randomisation were excluded from analyses (Figure 1). 919 women were included in the primary analysis: 456 randomly allocated to the control group and 463 to the adjuvant chemotherapy group. The median duration of follow-up was 60 months (IQR 45–65) at the data cut-off for the primary analysis (12 April 2021). Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the study arms, with two thirds of participants having a FIGO 2008 stage of IIB or higher, and half having pelvic and/or common iliac nodal involvement (Table 1).

Figure 1:

Trial profile

Table 1:

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics

| CRT (n=456) | CRT+ACT (n=463) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 45 (38–54) | 46 (37–55) |

| ECOG Performance status | ||

| 0 | 344 (75%) | 337 (73%) |

| 1 | 94 (21%) | 117 (25%) |

| 2 | 18 (4%) | 9 (2%) |

| Race/Ethnicity * | ||

| White/Caucasian | 326 (72%) | 337 (73%) |

| Black or African American | 68 (15%) | 53 (11%) |

| Asian | 22 (5%) | 31 (7%) |

| Aboriginal or Pacific Islander | 11 (2%) | 13 (3%) |

| Other | 28 (6%) | 29 (6%) |

| Region | ||

| Australia and New Zealand | 84 (18%) | 81 (17%) |

| USA and Canada | 366 (80%) | 373 (81%) |

| Rest of the World | 6 (1%) | 9 (2%) |

| Tobacco smoking | ||

| Never Smoker | 237 (52%) | 224 (48%) |

| Current or Ex-Smoker or Unknown | 219 (48%) | 239 (52%) |

| Histological type | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 358 (79%) | 383 (83%) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 79 (17%) | 68 (15%) |

| Adenosquamous | 19 (4%) | 12 (3%) |

| FIGO stage (2008) | ||

| 1B1 (all node positive), 1B2 or IIA | 152 (33%) | 154 (33%) |

| IIB | 196 (43%) | 197 (43%) |

| IIIB or IVA | 108 (24%) | 112 (24%) |

| Maximum tumour diameter, cm | 5.0 (4–6) | 5.0 (4–6) |

| Nodal involvement | ||

| Pelvic alone | 144 (32%) | 149 (32%) |

| Common iliac alone | 33 (7%) | 31 (7%) |

| Pelvic and common iliac | 44 (10%) | 44 (10%) |

| Neither | 225 (49%) | 231 (50%) |

| Unknown | 10 (2%) | 8 (2%) |

| Extended field planned | ||

| No | 397 (87%) | 404 (87%) |

| Yes | 59 (13%) | 59 (13%) |

Data are median (Q1–Q3) or n (%). CRT=Chemoradiation therapy. ACT=adjuvant chemotherapy. ECOG=Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. FIGO=International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Self-reported

Similar numbers of participants in each arm started and completed chemo-radiation as planned (Figure 1). Adherence to the standard chemo-radiation protocol was similar in the two treatment groups. Dose modification and/or delays for toxicity occurred for 162 (35%) of those assigned chemo-radiation plus adjuvant chemotherapy and 144 (32%) of those assigned chemo-radiation alone. A total of 765 (83%) of participants (382 (83%) CRT+ACT, 383 (84%) CRT alone) received five doses of cisplatin during chemo-radiation, with a further 140 received 1–4 doses (Table 2). One participant received radiation but no concurrent cisplatin.

Table 2:

Chemoradiation adherence

| CRT | CRT+ACT | |

|---|---|---|

| Cisplatin cycles | ||

| 0–3 | 27 (6%) | 49 (11%) |

| 4 | 46 (10%) | 32 (7%) |

| 5 | 383 (84%) | 382 (83%) |

| Cisplatin full doses with no delay | ||

| Cycle 1 | 450 100% | 451 99% |

| Cycle 2 | 438 98% | 434 96% |

| Cycle 3 | 431 97% | 423 95% |

| Cycle 4 | 420 95% | 409 93% |

| Cycle 5 | 383 88% | 375 87% |

| Cisplatin dose intensity, mg/m 2 /wk | 28 (27–29) | 28 (26–29) |

| Radiation technique | ||

| 4-field | 413 (91%) | 416 (92%) |

| 2-field | 7 (2%) | 5 (1%) |

| Other | 33 (7%) | 33 (7%) |

| EBRT dose given, Gy | 45·6 | 45·7 |

| EBRT nodal boost given | 145 (32%) | 135 (30%) |

| EBRT parametrial boost given | 161 (36%) | 165 (36%) |

| EBRT without interruption | 417 (92%) | 418 (92%) |

| Brachytherapy given | 429 (95%) | 426 (94%) |

| Brachtherapy dose rate | ||

| High dose rate (HDR) | 393 (92%) | 384 (90%) |

| Low dose rate (HDR) | 25 (6%) | 24 (6%) |

| Pulse dose rate (PDR) | 9 (2%) | 16 (4%) |

| Not recorded | 1 (0%) | 4 (1%) |

| Brachytherapy prescribed to | ||

| Point A | 292 (64%) | 292 (63%) |

| Image-guided | 134 (29%) | 131 (28%) |

| Not recorded | 30 (7%) | 40 (9%) |

| Duration of radiation | ||

| Less than 8 weeks | 278 (63%) | 281 (64%) |

| Within 8–10 weeks | 141 (32%) | 143 (33%) |

| >10 weeks | 19 (4%) | 14 (3%) |

| All chemoradiation completed | ||

| (5 cisplatin, 45 Gy EBRT, brachytherapy) | 353 (77%) | 356 (77%) |

| (minimum 4x cisplatin, 45 Gy EBRT, brachytherapy | 396 (87%) | 383 (83%) |

Data are median (Q1–Q3), n (%) or mean (SD). CRT=Chemoradiation therapy. ACT=adjuvant chemotherapy. EBRT=External beam radiation therapy.

External beam radiotherapy was given without interruption in 92% of participants, and brachytherapy was delivered as planned in 95%. All components of chemo-radiation were completed by 77% of participants, including at least 45 Gy of external beam radiotherapy, all planned brachytherapy, and all 5 cycles of concurrent cisplatin (Table 2).

Of participants randomly assigned adjuvant chemotherapy, 102/465 (22%) did not initiate any adjuvant chemotherapy. Patient preference was the most common reason recorded for this occurring (Supplementary table 8). Among 285 participants assigned adjuvant chemotherapy who received four doses, 200 (70%) completed all 4 cycles of carboplatin without dose reduction or delay, and 197 (69%) completed all 4 cycles of paclitaxel (Supplementary Table 1 and 9).

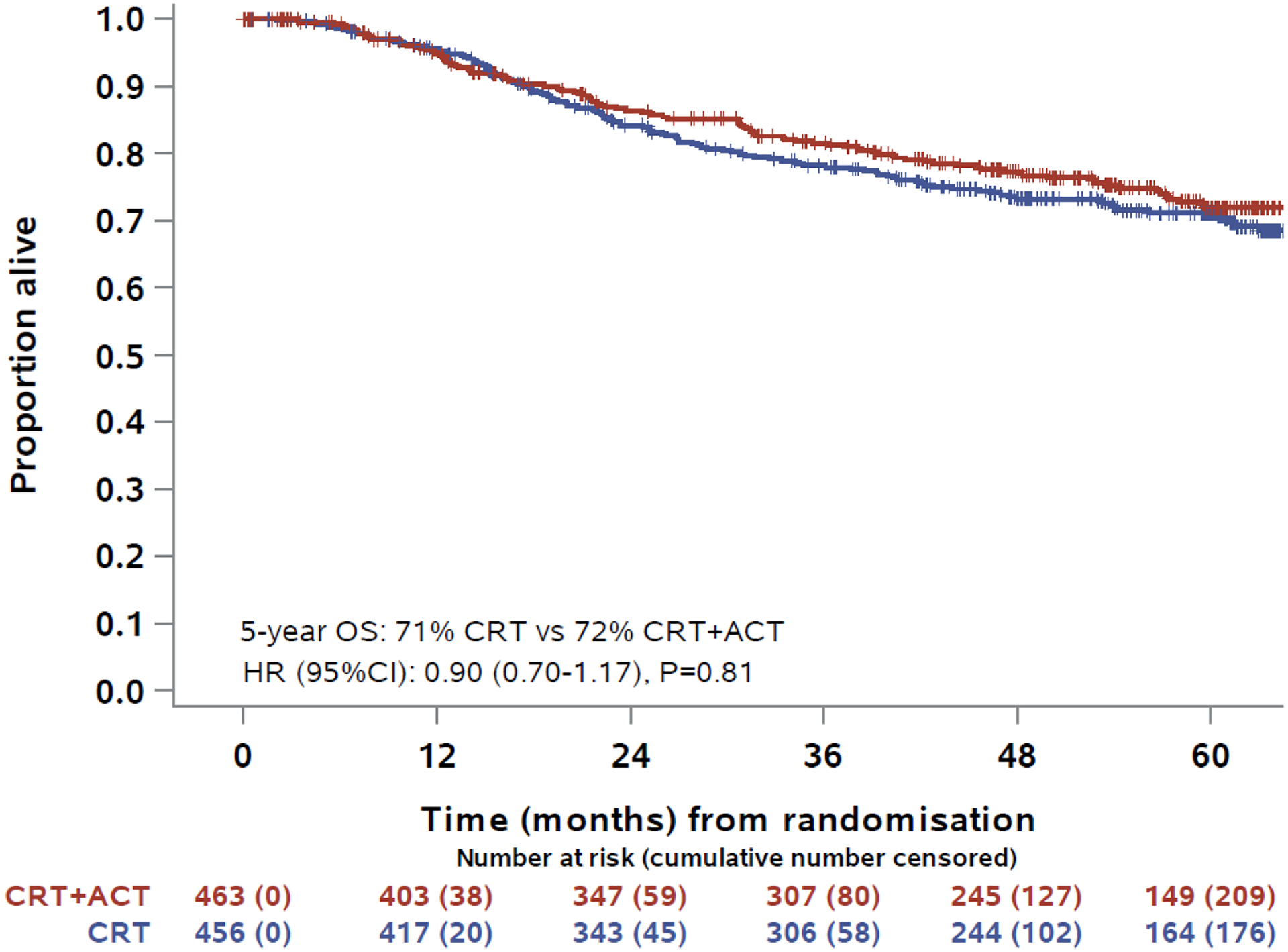

Overall survival was similar between allocated treatments. By the time of data cut-off there had been 109 deaths in the 463 participants assigned chemo-radiation plus adjuvant chemotherapy and 123 deaths in the 456 assigned chemo-radiation alone. The respective rates of 5-year OS were 72% (95% CI 67–76%, 105 deaths) vs 71% (95% CI 66–75%, 116 deaths) , difference 1% (p=0.81). The hazard ratio for OS was 0.90 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.17). Median overall survival time was not reached in either arm (Figure 2A).

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier estimates for overall survival

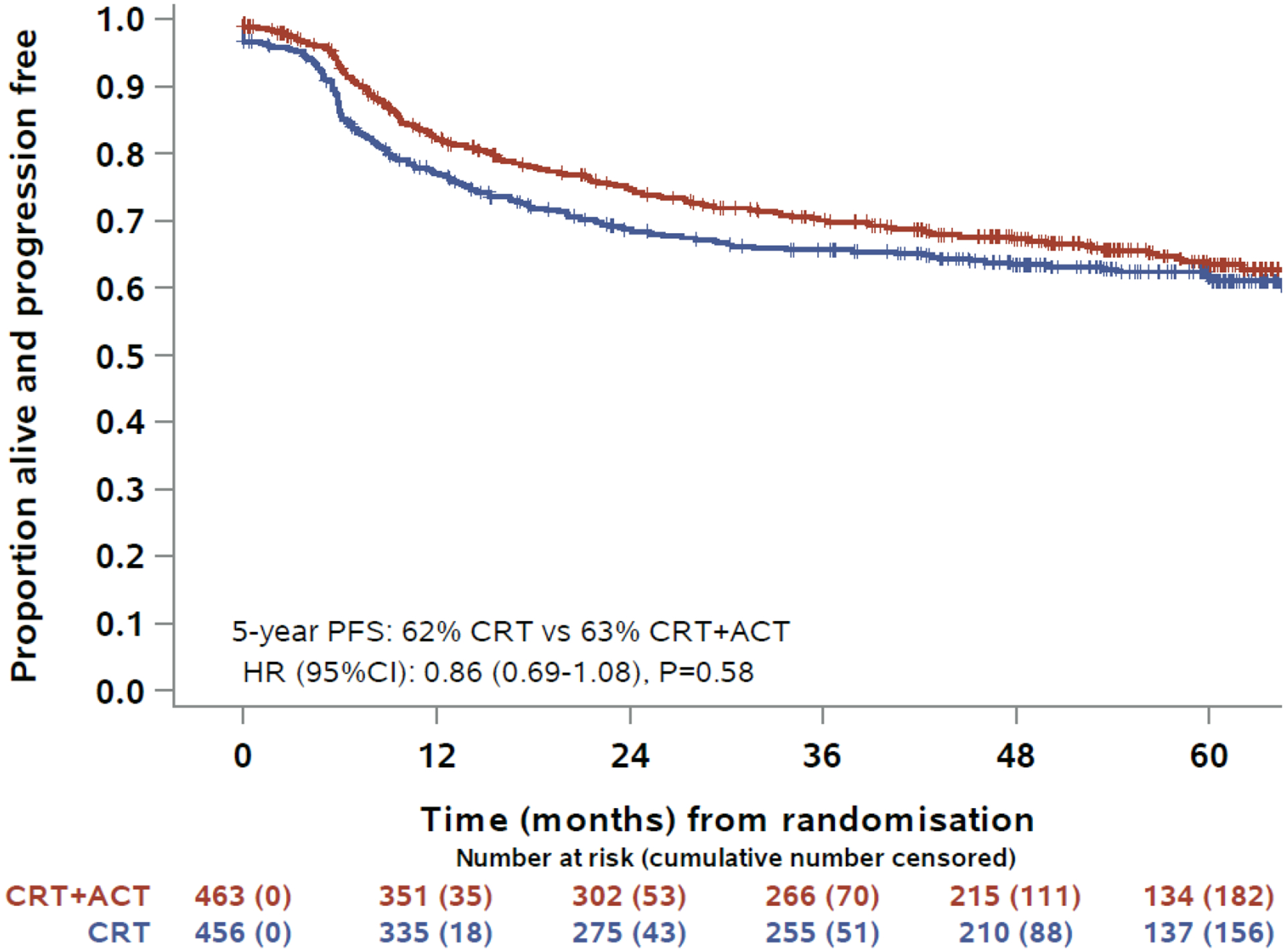

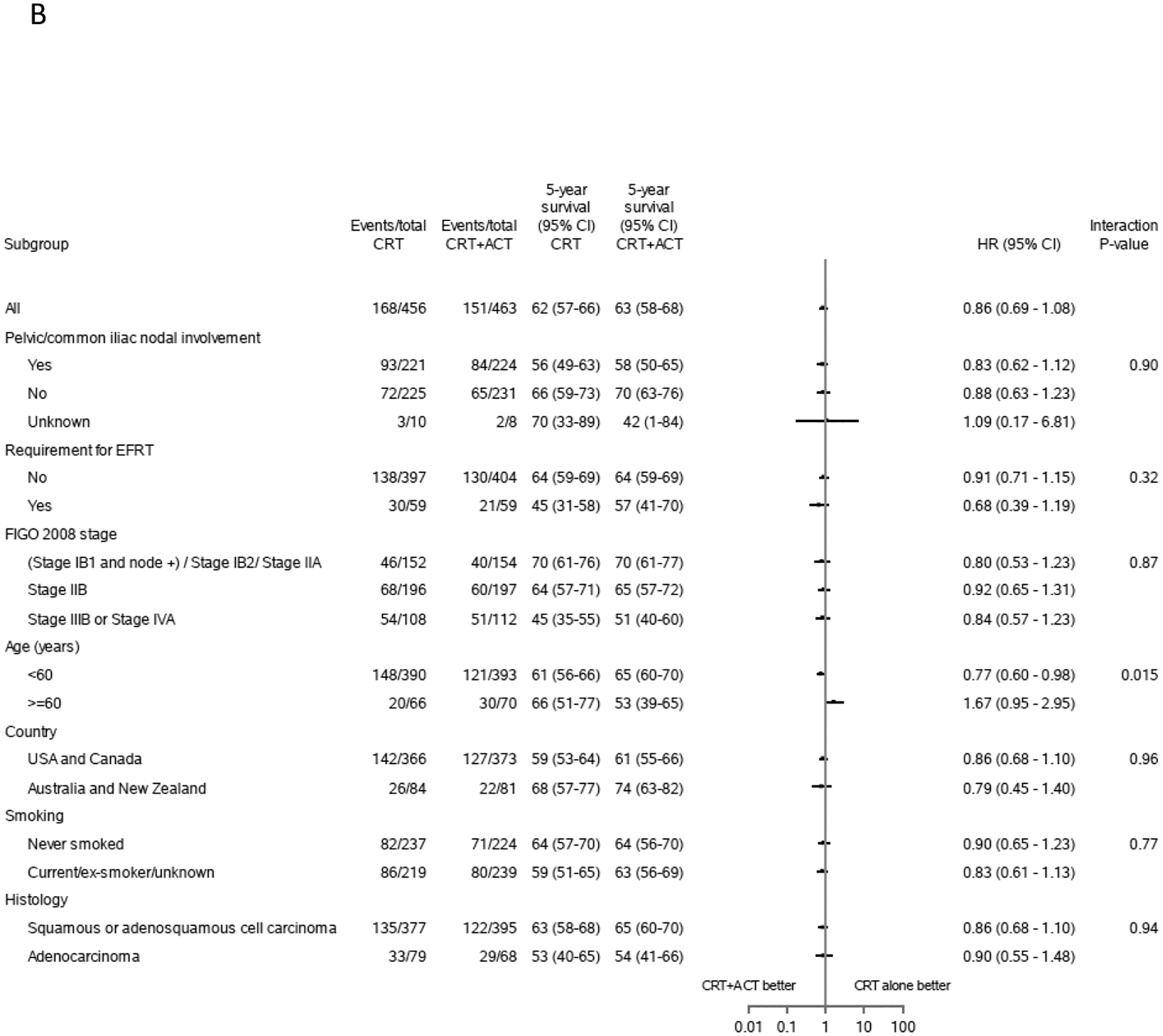

Progression-free survival was similar between allocated treatments. By the time of data cut-off there had been 151 events (20 deaths, 131 progressions) in the 463 participants assigned chemo-radiation plus adjuvant chemotherapy and 168 events (18 deaths, 150 progressions) in the 456 assigned chemo-radiation alone. The 5-year PFS was 63% (95% CI:58–68%,147 events (18 deaths, 129 progressions)) and 62% (95% CI:57–66%, 163 events (17 deaths, 146 progressions)), for CRT+ACT vs CRT alone, respectively, difference 2% (p = 0.58). The hazard ratio for PFS was 0.86 (95% CI:0.69–1.07, p=0.6) (Figure 2B). The 3-year PFS was 70% (95% CI:65–74%, 127 events (11 deaths, 116 progressions)) and 66% (95% CI:61–70%, 150 events (14 deaths, 136 progressions)), for CRT+ACT vs CRT alone, respectively, difference 4% (p = 0.17). There were 84 cervical-cancer specific deaths and 25 with other/unknown cause in CRT+ACT arm vs 102 cervical cancer specific deaths and 21 with other/unknown cause in CRT arm. The 5-year cumulative incidence of cervical-cancer specific death was also similar in in both arms: 21% (95% CI:17–26) vs 24% (95% CI:20–28), P=0.21. Forest plots and p-values for interactions showed no evidence that adjuvant chemotherapy had different effects on OS or PFS in pre-specified sub-groups defined by nodal status, requirement for extended field radiotherapy, FIGO stage, country and smoking status, or post-hoc subgroup histological sub-type (Figure 3). However, there was some evidence that the effects of adjuvant chemotherapy were less favourable among women aged 60 years or older, with interaction p-values of 0.015 for PFS and 0.019 for OS.

Figure 3:

Kaplan-Meier estimates for progression-free survival

Sensitivity analysis showed that among those who completed the initial chemo-radiation, the HR for the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on OS was 0.81, with an absolute difference of 3% in 5-year OS between the treatment arms, compared with a HR of 1.32 for those who did not complete chemo-radiation. A similar pattern was seen for PFS (Supplementary Table 2).

There were 281 participants for whom progression was documented (131 CRT+ACT, 150 CRT alone), sites of disease recurrence were similar in the randomly assigned groups, with the majority of participants remaining disease-free at last follow-up. In the ITT population, persistent disease after treatment was reported in 5 (1%) vs 15 (3%) participants (adjuvant chemotherapy vs control). Isolated loco-regional recurrence was reported in 54 (12%) vs 50 (11%). Distant recurrence was reported in 61 (13%) vs 70 (15%). Sites of other/unknown recurrence sites were reported in 11 (2%) vs 15 (3%). There was no evidence of difference in sites of recurrence (none vs loco-regional vs distant vs other/unknown) between the randomly assigned groups (P=0.12).

In the safety population (361 in CRT+ACT arm, 453 in CRT arm), Grade 2 or worse adverse events were reported in the first year after randomisation in 356 (99%) assigned adjuvant chemotherapy versus 409 (90%) participants assigned control, and ≥ grade 3 in 292 (81%) versus 280 (62%), p<0·0001. Table 3 shows the adverse events seen in ≥10% of participants. Established toxicities of carboplatin and/or paclitaxel such as nausea, vomiting, haematological toxicity, alopecia, fatigue, myalgia, and peripheral neuropathy were more frequent in the adjuvant chemotherapy group and resulted in 84 serious adverse events in 56 participants. Febrile neutropenia occurred in 2% of participants in both arms. There were no deaths attributed to study treatment. Beyond 1 year, there were safety data for 693 members of the safety population (316 CRT+ACT, 377 CRT alone) (Supplementary table 3–6). The only difference between treatment groups was a higher frequency of grade 2 sensory peripheral neuropathy among those assigned adjuvant chemotherapy (8% vs 2%; p<0.0001). Late effects of radiation therapy were not reported more frequently among those assigned adjuvant chemotherapy.

Table 3:

AEs occurring in at least 10% of participants at any grade, or in at least 1% of participants at Grade 3–5

| CRT n(%) | CRT+ACT n (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event | Grad e 1–2 | Grad e 3 | Grad e 4 | Grad e 5 | Grad e 1–2 | Grad e 3 | Grad e 4 | Grad e 5 | P-value* |

| Abdominal pain | 179 (40) | 16 (4) | 175 (48) | 19 (5) | 0.0086 | ||||

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 77 (17) | 3 (1) | 1 (0) | 98 (27) | 2 (1) | 0.0020 | |||

| Alopecia | 40 (9) | 284 (79) | 1 (0) | <.0001 | |||||

| Anemia | 259 (57) | 34 (8) | 1 (0) | 238 (66) | 66 (18) | <.0001 | |||

| Anorexia | 138 (30) | 5 (1) | 129 (36) | 2 (1) | 0.21 | ||||

| Anxiety | 62 (14) | 1 (0) | 76 (21) | 1 (0) | 0.020 | ||||

| Arthralgia | 40 (9) | 1 (0) | 79 (22) | 1 (0) | <.0001 | ||||

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 46 (10) | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 84 (23) | 2 (1) | <.0001 | |||

| Back pain | 111 (25) | 5 (1) | 96 (27) | 4 (1) | 0.79 | ||||

| Constipation | 204 (45) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 192 (53) | 1 (0) | 0.067 | |||

| Creatinine increased | 57 (13) | 4 (1) | 1 (0) | 59 (16) | 3 (1) | 0.30 | |||

| Cystitis noninfective | 102 (23) | 6 (1) | 95 (26) | 6 (2) | 0.40 | ||||

| Dehydration | 40 (9) | 14 (3) | 50 (14) | 9 (2) | 0.071 | ||||

| Depression | 57 (13) | 1 (0) | 70 (19) | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | 0.012 | |||

| Dermatitis radiation | 64 (14) | 1 (0) | 64 (18) | 1 (0) | 0.37 | ||||

| Diarrhea | 323 (71) | 21 (5) | 277 (77) | 21 (6) | 0.064 | ||||

| Dizziness | 53 (12) | 1 (0) | 65 (18) | 2 (1) | 0.028 | ||||

| Dysgeusia | 58 (13) | 60 (17) | 0.12 | ||||||

| Dyspnea | 58 (13) | 3 (1) | 1 (0) | 78 (22) | 3 (1) | 0.0037 | |||

| Dysuria | 54 (12) | 58 (16) | 0.088 | ||||||

| Edema limbs | 49 (11) | 2 (0) | 52 (14) | 0.14 | |||||

| Fatigue | 361 (80) | 8 (2) | 327 (91) | 9 (2) | <.0001 | ||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 8 (2) | 1 (0) | 9 (2) | 0.63 | |||||

| Female genital tract fistula | 10 (2) | 6 (1) | 2 (0) | 6 (2) | 5 (1) | 0.78 | |||

| Fever | 32 (7) | 54 (15) | 3 (1) | 0.0001 7 | |||||

| Headache | 94 (21) | 1 (0) | 103 (29) | 0.025 | |||||

| Hearing impaired | 47 (10) | 51 (14) | 4 (1) | 0.019 | |||||

| Hemorrhage Bladder | 76 (17) | 7 (2) | 54 (15) | 5 (1) | 0.76 | ||||

| Hemorrhage Rectum | 62 (14) | 2 (0) | 65 (18) | 1 (0) | 0.23 | ||||

| Hot flashes | 106 (23) | 115 (32) | 2 (1) | 0.0066 | |||||

| Hyperglycemia | 41 (9) | 8 (2) | 3 (1) | 58 (16) | 7 (2) | 3 (1) | 0.0087 | ||

| Hypertension | 28 (6) | 17 (4) | 45 (12) | 12 (3) | 0.0077 | ||||

| Hypoalbuminemia | 54 (12) | 1 (0) | 67 (19) | 2 (1) | 0.021 | ||||

| Hypocalcemia | 56 (12) | 3 (1) | 58 (16) | 1 (0) | 0.24 | ||||

| Hypokalemia | 69 (15) | 11 (2) | 4 (1) | 65 (18) | 17 (5) | 0.30 | |||

| Hypomagnesemia | 100 (22) | 2 (0) | 2 (0) | 111 (31) | 6 (2) | 0.0096 | |||

| Hyponatremia | 62 (14) | 3 (1) | 46 (13) | 12 (3) | 0.019 | ||||

| Insomnia | 96 (21) | 1 (0) | 104 (29) | 0.030 | |||||

| Kidney infection | 1 (0) | 5 (1) | 3 (1) | 0.62 | |||||

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 114 (25) | 167 (37) | 41 (9) | 77 (21) | 179 (50) | 32 (9) | 0.0012 | ||

| Menopause | 8 (2) | 12 (3) | 5 (1) | 16 (4) | 0.35 | ||||

| Myalgia | 52 (11) | 141 (39) | 3 (1) | <.0001 | |||||

| Nausea | 335 (74) | 14 (3) | 296 (82) | 11 (3) | 0.016 | ||||

| Neutrophil count decreased | 84 (19) | 27 (6) | 7 (2) | 117 (32) | 61 (17) | 10 (3) | <.0001 | ||

| Pain | 41 (9) | 3 (1) | 44 (12) | 3 (1) | 0.33 | ||||

| Pain in extremity | 94 (21) | 3 (1) | 123 (34) | 2 (1) | 0.0001 1 | ||||

| Pelvic pain | 146 (32) | 11 (2) | 138 (38) | 8 (2) | 0.20 | ||||

| Peripheral motor neuropathy | 19 (4) | 72 (20) | 4 (1) | <.0001 | |||||

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 130 (29) | 1 (0) | 271 (75) | 16 (4) | <.0001 | ||||

| Platelet count decreased | 140 (31) | 3 (1) | 2 (0) | 192 (53) | 14 (4) | 2 (1) | <.0001 | ||

| Premature menopause | 11 (2) | 1 (0) | 17 (5) | 0.11 | |||||

| Proctitis | 49 (11) | 2 (0) | 34 (9) | 0.36 | |||||

| Sepsis | 1 (0) | 8 (2) | 1 (0) | 3 (1) | 0.32 | ||||

| Small intestinal obstruction | 1 (0) | 5 (1) | 1 (0) | 8 (2) | 1 (0) | 0.31 | |||

| Syncope | 2 (0) | 5 (1) | 4 (1) | 5 (1) | 0.51 | ||||

| Thrombosis/Thrombus/Embolism | 19 (4) | 7 (2) | 18 (5) | 5 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.78 | |||

| Tinnitus | 84 (19) | 87 (24) | 1 (0) | 0.079 | |||||

| Urinary frequency | 92 (20) | 84 (23) | 0.31 | ||||||

| Urinary incontinence | 69 (15) | 68 (19) | 1 (0) | 0.20 | |||||

| Urinary tract infection | 63 (14) | 17 (4) | 1 (0) | 51 (14) | 17 (5) | 0.87 | |||

| Urinary tract obstruction | 1 (0) | 10 (2) | 1 (0) | 8 (2) | 0.99 | ||||

| Urinary tract pain | 45 (10) | 1 (0) | 56 (16) | 0.039 | |||||

| Urinary urgency | 40 (9) | 44 (12) | 0.12 | ||||||

| Vaginal discharge | 167 (37) | 147 (41) | 0.26 | ||||||

| Vaginal dryness | 56 (12) | 53 (15) | 1 (0) | 0.33 | |||||

| Vaginal hemorrhage | 164 (36) | 8 (2) | 1 (0) | 133 (37) | 7 (2) | 1 (0) | 0.95 | ||

| Vaginal pain | 65 (14) | 3 (1) | 47 (13) | 2 (1) | 0.84 | ||||

| Vaginal stricture | 57 (13) | 10 (2) | 39 (11) | 5 (1) | 0.49 | ||||

| Vomiting | 165 (36) | 11 (2) | 166 (46) | 15 (4) | 0.0042 | ||||

| Weight loss | 46 (10) | 6 (1) | 52 (14) | 6 (2) | 0.16 | ||||

| White blood cell decreased | 80 (18) | 16 (4) | 3 (1) | 74 (20) | 31 (9) | 7 (2) | 0.00066 | ||

Chi-square test comparing none vs. mild vs. severe between arms

A total of 807 participants (406 (88%) CRT+ACT, 401 (88%) CRT alone) participated in HRQOL collection, of whom 369 (92%) and 369 (91%) completed a questionnaire at baseline. The number of HRQL questionnaires available for analysis over the study period are summarized in supplementary Table 7. Mean QLQ-C30 global health status/quality of life scores were poorer among those assigned ACT versus control for 3–6 months after completion of chemo-radiation (supplementary figure 1, supplementary table 8). However, means were similar between the groups from months 12 to 36.

There were 536 participants with measurable disease at baseline according to RECIST 1.1 (284 CRT+ACT, 252 CRT). Of these the numbers (percentages) in each arm with a complete response were 150/284 (53%) vs 124/252 (49%) or a partial response were 77/284 (27%) vs 68/252 (27%), respectively for the adjuvant chemotherapy vs control group (P=0.55). The frequency of a complete metabolic response on PET or PET/CT performed 4 or more months after completing chemo-radiation was 138/244 (57%) vs 111/223 (50%) for the adjuvant chemotherapy vs control group (P=0.14). Achieving a complete metabolic response on PET or PET/CT was associated with improved OS (HR 0.22, 95% CI 0.14–0.33; p<0.0001), and PFS (HR 0.24, 95% CI 0.17–0.33; p<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

The planned addition of 4 cycles of paclitaxel and carboplatin following chemo-radiation with cisplatin for locally-advanced cervical cancer did not improve overall survival or progression-free survival in OUTBACK, but did increase adverse event rates and diminish patient-reported health and quality of life during and up to 6 months after treatment. The survival results are somewhat surprising given the suggestive evidence for adjuvant cytotoxic therapy in this same patient population in prior trials6,10,23. This academic study, with large sample size, mature follow-up and multi-national accrual, provides opportunities to generate hypotheses for the results seen in OUTBACK.

Despite the use of standard cisplatin-based chemo-radiation, treatment failures still exist. This led to trials aiming to improve upon chemo-radiation, largely focused on adding cytotoxics or novel agents to chemo-radiation, and most recently immune checkpoint inhibitors14–18. Of the trials with novels agents reported to date, tirapazamine moved into a randomised phase 3 trial, but did not improve PFS or OS19. A recent conference presentation indicated that adding adjuvant durvalumab to chemo-radiation failed to improve PFS20.

The rationale for adjuvant chemotherapy following chemo-radiation has its proof of concept in two of the original positive trials that lead to the NCI alert. RTOG 90–01 used one additional cycle of cisplatin/5-fluorouracil following RT, and GOG protocol 109 used 2 additional cycles of cisplatin/5-fluorouracil following RT after radical hysterectomy5,21. Subsequently, the Duenas-Gonzales trial evaluating the addition of gemcitabine to chemo-radiation followed by 2 additional cycles of cisplatin/gemcitabine did demonstrate an improved PFS, but the abridged follow-up time prohibited any robust conclusion about impact on overall survival9. OUTBACK did not demonstrate a similar improvement in PFS or OS in a larger sample size with 5 years of follow-up. Our results are consistent with a recent meta-analysis, which included two randomised controlled trials, and some matched case-control and retrospective studies, and found no survival benefit but increased toxicity with the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy22,23. Our results are also consistent with the similarly designed ACTLACC trial, which used only 3 cycles of adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel, but closed after interim analysis due to futility24. Although OUTBACK used carboplatin/paclitaxel adjuvant chemotherapy, rather than cisplatin/gemcitabine, it is unlikely that this difference accounts for the different outcomes given that platinum/paclitaxel is recommended as the most active regimen to treat metastatic disease25. The Duenas-Gonzalez trial also added additional gemcitabine chemotherapy to cisplatin during the standard chemo-radiation. However, a subsequent trial trying to test the impact of just adding gemcitabine during chemo-radiation, was closed early due to futility16.

Limitations and notable aspects of OUTBACK and how to move the field forward

Adherence with assigned adjuvant therapy: One key limitation, that is noteworthy for future trial design, is the lack of compliance with planned adjuvant chemotherapy with 22% of participants not receiving any planned adjuvant treatment. This is a substantial enough fraction to impact outcomes, however as a result the sample was size increased after the trial started to account for this. Of note this also occurred in prior trials of adjuvant chemotherapy, with 14%, 32%, 23% and 29% of participants not receiving any of the planned adjuvant chemotherapy in the Duenas-Gonzalez, RTOG 90–01, ACTLACC, or GOG109 trials respectively6,10,23 24. Patient preference was the most commonly reported reason for not commencing planned adjuvant chemotherapy, which likely resulted from residual toxicities after standard chemo-radiation including fatigue. Prior to performing the primary analysis for OUTBACK, we identified an association of older age (>60), non-White/Caucasian race and failure to complete the initial standard chemo-radiation, with not proceeding to any adjuvant therapy13. This suggests a subset of patients in this trial with additional vulnerabilities that impacted their ability to complete assigned therapy. For relatively young and sometimes disadvantaged patients, this may include financial and social pressures as well concern about alopecia. It also raises the hypothesis of whether future trials of adjuvant systemic therapy should randomise patients after completion of standard chemo-radiation. However, our sensitivity analysis did not find clinically meaningful improvements in survival even in the subset of patients who completed initial chemo-radiation, which was the group most likely to complete assigned adjuvant therapy. The ongoing INTERLACE trial will answer the question about whether giving a short-course of weekly chemotherapy prior to chemo-radiation could improve patient outcomes and be more deliverable (NCT01566240).

-

Radiation type and quality: OUTBACK utilized 4 field RT and brachytherapy to help generalize radiation availability for this global trial; while some higher resource countries are now moving to more sophisticated RT planning such as IMRT, this form of RT is still widely used and accepted standard treatment in the 2023 NCCN guidelines. Only 77% of OUTBACK patients completed planned chemo-radiation (with all 5 weekly doses of cisplatin), irrespective of allocated treatment. Radiation was completed within 8 weeks in <70% of patients with a mean dose of 45.6 Gy, indicating room for improvement. Impressively, brachytherapy was given to 95% of patients. For comparison, in the Duenas Gonzales study, the mean external beam dose was 50.4 Gy with a median time for overall radiation at 49 and 45 days in the experimental and control arms respectively9. Despite these differences, given that radiation adherence was similar between treatment arms it is unlikely to have impacted the primary endpoint of OUTBACK. In addition, we note the identical 3-year PFS rate of 65% in the control arm of both trials.

Emerging data suggests that improved imaging and radiation delivery may identify tumours at higher risk for treatment failure which may benefit from additional therapy. The EMBRACE 1 multicentre prospective cohort study confirmed the benefit of image-guided brachytherapy for locally-advanced cervical cancer, which was given to only 1/3 OUTBACK participants. In subset analysis this study identified clinical/pathologic factors associated with local treatment failure, including any positive common iliac lymph nodes (but negative para-aortics). Use of elective para-aortic radiation in this higher-risk group decreased para-aortic treatment failures26. The ongoing EMBRACE II study is evaluating IMRT/VMAT for elective para-aortic radiation and integrating radiation boost for cervical cancer (NCT03617133) in an attempt to improve local control and decrease distant failures. An important question is whether there is more to be gained by adding more drugs to chemo-radiation, or instead ensuring that excellent quality primary chemo-radiation is available to all women with this disease. In addition, new less-toxic radiation techniques could make it more feasible to test the benefit of giving additional systemic therapies.

-

Enrolment of a population at high-risk for treatment failure

Like OUTBACK, EMBRACE 1 recruited a population that was felt to be at high risk for recurrence, but ultimately was not found to be particularly high-risk. A recent exploratory analysis for OUTBACK re-evaluated outcomes when the tumours were re-staged based on FIGO 2018 staging criteria, which now incorporates nodal status. In this analysis, the FIGO 2008 Stage III/IV (T3 and T4 lesions) had a 5 year PFS rate of 48% and 5 year OS rate of 58%27. These more advanced tumours do appear to be highest risk and may comprise the group of patients who may benefit from any addition to chemo-radiation. However, in our study and others, those with higher stage tumours or node-positive disease, received no benefit from the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy24.

-

The best primary endpoint for trials in locally-advanced cervical cancer

In the past, when there were no effective interventions post systemic chemotherapy +/− bevacizumab for advanced/recurrent disease, overall survival was the best endpoint as there were no interventions expected to confound the results28. With the approval of immune checkpoint inhibitors concomitant with systemic chemotherapy +/− bevacizumab for advanced/metastatic disease as well as approvals for monotherapy use for second line metastatic disease, the expected overall survival has improved and these agents could confound outcomes depending on use and availability29,30. With new agents in the pipeline, one has to consider whether PFS may be an appropriate primary endpoint in lieu of, or with overall survival for future studies. However, it is unlikely that these newer therapies were potentially confounding for overall survival in OUTBACK, as they were not available to patients in study sites during the study timeframe.

Future studies should focus on participants with higher risk disease who have more to gain from additional treatment, and avoid over-treating patients who do well with current standard of care treatments. Subsequent translational research from OUTBACK will be important to further understand which groups of patients are most at risk of recurring. Further, benchmarks for studies moving forward will have to take into account the stage migration that occurred with the FIGO 2008 to FIGO 2018 staging transition. As an example, from the cited OUTBACK analysis mentioned earlier the 5-year PFS rate for FIGO 2008 Stage III/IVa was 48% but in the FIGO 2018 staging, stage III/IV was 56%27. The OUTBACK re-analysis provides helpful information for benchmarking control group expectations for future studies using the 2018 staging system.

Conclusion:

Adjuvant chemotherapy with 4 cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel did not improve overall survival or progression-free survival after chemo-radiation with weekly cisplatin for locally-advanced cervical cancer. Use of adjuvant carboplatin/paclitaxel following chemo-radiation should not be used. Future studies should select participants with high-risk disease and overcome barriers to adherence with treatment.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4:

Forest plots estimates for overall survival and progression-free survival

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed and Google Scholar for articles written in English from database inception before the study started, and again on 26th Oct 2022 using the terms “cervical cancer”, “cervix cancer”, “locally-advanced”, “radiotherapy” and “adjuvant” chemotherapy. Although some prior individual trials have suggested benefit from the addition of adjuvant chemotherapy to chemo-radiation, this data was considered controversial, and the results of meta-analyses have failed to confirm a survival benefit from this practice.

Added value of this study

OUTBACK is a large, adequately powered randomised controlled trial with mature follow-up and overall survival as the primary endpoint. This trial conclusively demonstrates that adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy given after standard chemo-radiation for unselected locally-advanced cervical cancer increases toxicity without improving progression-free or overall-survival. Our study also reinforced the value of strong multi-national intergroup collaboration required to successfully complete randomised trials in cervical cancer and raises several questions about the optimal way to design future trials in this disease.Implications of all the available evidence Standard treatment for locally-advanced cervical cancer should remain cisplatin-based external beam chemo-radiation plus brachytherapy. More efforts are needed to ensure that all women diagnosed globally with cervical cancer can receive standard cisplatin-based chemoradiation.. Adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy should not be used in this setting.

Acknowledgements:

We acknowledge and thank: the women who participated and their families; staff at sites in the USA, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, China, Singapore, Saudi Arabia; staff at the NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre, The University of Sydney, ANZGOG, and NRG; Australian NHMRC (APP1044349) and US NCI for financial support; Hospira for providing paclitaxel in Australia and New Zealand; and the OUTBACK IDSMC members.

Declaration of interests:

LRM reports grant from NHMRC Australia for support for the present manuscript.

KNM reports research funding to institution outside of submitted work from PTC Therapeutics, Lilly, Merck, GSK/Tesaro, participation on an Advisory Board for AstraZeneca, Aravive, Inc., Alkemeres, Addi, Blueprint Medicines, Eisai Co., Ltd., EMD Serono Inc., Elevar Therapeutics, GSK/Tesaro, Genentench/Roche, Hengrui, Immunogen, INXmed, IMab, Lilly, Mereo, Mersana Therapeutics, Merck, Myriad, Novartis, Novocure, OncXerna, Onconova Therapeutics, Tarveda Therapeutics, VBL Therapeutics and Verastem Oncology, and leadership role as Associate Director of GOG Partners and on the Board of Directors for GOG Foundation.

WSJ reports honoraria for invited talks from Carl Zeiss and payments made for participation on a DSMB from Novocure, and Co-Chair of Gynaecological Committee until June 2020 with NRG Oncology.

DKG reports grants/contracts from Elekta - Clinical Trial as Principal Investigator, payment/honoraria from ANZGOG for the 2022 Meeting, payment for expert testimony in the Montana court case, participating on a DSMB/Advisory Board for a Merck cervical trial, and leadership role in NRG Oncology as Co-Chair of the Gyn Committee.

PK reports funding outside of this submitted work from ANZGOG Fund for New Research (STRIVE Study, $100k over 12 months), Medical Research Future Fund Reproductive Cancers Grant (ADELE Study, $1.63 mil over 3 years from 2021), Deputy Chair of Treatment Pillar for the National Cervical Cancer Elimination Strategy (unpaid), Board Director for ANZGOG (unpaid) and Board Director for AMA Victoria (May 2021-April 2022, small retention fee paid).

JST reports support for the present manuscript from University of Oklahoma as his primary employment.

WKH reports consulting fee payments from AstraZeneca and SeaGen and payment for participation on a DSMB from Syneos and Inovio.

CAM reports support for the present manuscript from National Cancer Institute, and funding to institution outside of the submitted work from Syros, Deciphera, Astellas Pharma GlaxoSmithKline/Tesaro, Seagen, Genmab, EMD Serono, Merck, Regeneron, Moderna, Astra Zeneca, and Genentech.

TEL reports support for the present manuscript from the National Cancer Institute Community Research Program and support for attending meetings/travel from SHCC MU NCORP Grant.

CHH reports support for the present manuscript from GOG/NRG, and leadership role in the Executive Board, Western Association of Gynecologic Oncology and the 2023 Program Committee Chair, Western Association of Gynecologic Oncology.

MQ reports personal payment as Chair of IDSMC for the Garnet Study and Tesaro Study from GSK, and Chair of DSMB for the COMPASS Study.

DR reports trial funding all to institution outside of submitted work from MSD, GSK, Regeneron, Roche, BMS, Kura, ALX Oncology and participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board (unpaid) for MSD, Regeneron, Sanofi.

BJM reports consulting fees from Acrivon, Adaptimune, Agenus, Akeso Bio, Amgen, Aravive. AstraZeneca, Bayer, Clovis, Easai, Elevar, EMD Merck, Genmab/Seagen, GOG Foundation, Gradalis, Heng Rui, ImmunoGen, Karyopharm, Iovance, Laekna, Macrogenics, Merck, Mersana, Myriad, Novartis, Novocure, OncoC4, Panavance, Pieris, Pfizer, Puma, Regeneron, Roche/Genentech, Sorrento, TESARO/GSK, US Oncology Research, VBL, Verastem, Zentalis, and payment/horaria from AstraZeneca, Merck, Myriad, TESARO/GSK, Roche/Genentech, Clovis and Easai.

MRS reports grant to institution from NHMRC Australia for support for the present manuscript, and grants to institution for the conduct of investigator-initiated, academically-sponsored trials from Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BeiGene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Medivation, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi and Tilray.

EHB, VG, KN, MTK, NB, YCL, KD, AF, SB, MB, AS, IJB and SVD declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data sharing:

De-identified study data are available for sharing. To request access to the de-identified study data, please contact the corresponding author. Requests will be reviewed by the Trial Management Committee and written applications from investigators with the academic capability and credibility to undertake the work proposed will be considered. The scientific merit of the proposal, including the appropriate methods, analysis, and publication plan will be assessed. Consideration will be taken of any overlap with analyses already undertaken or planned to be undertaken by the study team. If a proposal is approved, a signed data transfer agreement will be required before data sharing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24(14): 2137–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021; 71(3): 209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spayne J, Ackerman I, Milosevic M, Seidenfeld A, Covens A, Paszat L. Invasive cervical cancer: a failure of screening. Eur J Public Health 2008; 18(2): 162–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keys HM, Bundy BN, Stehman FB, et al. Cisplatin, radiation, and adjuvant hysterectomy compared with radiation and adjuvant hysterectomy for bulky stage IB cervical carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1999; 340(15): 1154–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris M, Eifel PJ, Lu J, et al. Pelvic radiation with concurrent chemotherapy compared with pelvic and para-aortic radiation for high-risk cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 1999; 340(15): 1137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose PG, Bundy BN, Watkins EB, et al. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 1999; 340(15): 1144–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reducing uncertainties about the effects of chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 18 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26(35): 5802–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narayan K, Fisher RJ, Bernshaw D, Shakher R, Hicks RJ. Patterns of failure and prognostic factor analyses in locally advanced cervical cancer patients staged by positron emission tomography and treated with curative intent. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2009; 19(5): 912–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duenas-Gonzalez A, Zarba JJ, Patel F, et al. Phase III, open-label, randomized study comparing concurrent gemcitabine plus cisplatin and radiation followed by adjuvant gemcitabine and cisplatin versus concurrent cisplatin and radiation in patients with stage IIB to IVA carcinoma of the cervix. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29(13): 1678–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasioudis D, Smith AJ, Latif N. Adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with locally advanced cervical carcinoma receiving definitive chemoradiation: utilization and outcomes before the OUTBACK trial. 2022 Society of Gynaecological Oncology Annual Meeting; 2022 18–21 March 2022; Phoenix, Arizona; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993; 85(5): 365–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin DY, Wei LJ, Ying Z. Checking the Cox Model with cumulative sumars of Martingale-based residuals. Biometrika 1993; 80(3): 557–72. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mileshkin L, Barnes E, Moore K, et al. Disparities starting adjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced cervix cancer in the international, academic, randomised, phase 3 OUTBACK trial (ANZGOG 0902, RTOG 1174, NRG 0274). . ESMO Congress; 2021 September; Barcelona; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duska LR, Scalici JM, Temkin SM, et al. Results of an early safety analysis of a study of the combination of pembrolizumab and pelvic chemoradiation in locally advanced cervical cancer. Cancer 2020; 126(22): 4948–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose PG, Sill MW, McMeekin DS, et al. A phase I study of concurrent weekly topotecan and cisplatin chemotherapy with whole pelvic radiation therapy in locally advanced cervical cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecol Oncol 2012; 125(1): 158–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang CC, Chou HH, Yang LY, et al. A randomized trial comparing concurrent chemoradiotherapy with single-agent cisplatin versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine in patients with advanced cervical cancer: An Asian Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 2015; 137(3): 462–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rischin D, Narayan K, Oza AM, et al. Phase 1 study of tirapazamine in combination with radiation and weekly cisplatin in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2010; 20(5): 827–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunos CA, Sherertz TM. Long-term disease control with triapine based radiochemotherapy for patients with stage IB2-IIIB cervical cancer. Front Oncol 2014; 4: 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiSilvestro PA, Ali S, Craighead PS, et al. Phase III randomized trial of weekly cisplatin and irradiation versus cisplatin and tirapazamine and irradiation in stages IB2, IIA, IIB, IIIB, and IVA cervical carcinoma limited to the pelvis: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(5): 458–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monk BJ, Toita T, Wu X, Carlos J. Durvalumab, in combination with and following chemoradiotherapy, in locally advanced cervical cancer: results from the phase 3 international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled CALLA trial. IGCS Annual Global Meeting; 2022 Sept 29–Oct 1; New York Ciry; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters WA 3rd, Liu PY, Barrett RJ 2nd, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy compared with pelvic radiation therapy alone as adjuvant therapy after radical surgery in high-risk early-stage cancer of the cervix. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18(8): 1606–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horeweg N, Mittal P, Gradowska PL, Boere I, Nout RA, Chopra S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy after chemoradiation for locally advanced cervical cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2022; 172: 103638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tangjitgamol S, Katanyoo K, Laopaiboon M, Lumbiganon P, Manusirivithaya S, Supawattanabodee B. Adjuvant chemotherapy after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced cervical cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 2014(12): CD010401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tangjitgamol S, Tharavichitkul E, Tovanabutra C, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing concurrent chemoradiation versus concurrent chemoradiation followed by adjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer patients: ACTLACC trial. J Gynecol Oncol 2019; 30(4): e82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitagawa R, Katsumata N, Shibata T, et al. Paclitaxel Plus Carboplatin Versus Paclitaxel Plus Cisplatin in Metastatic or Recurrent Cervical Cancer: The Open-Label Randomized Phase III Trial JCOG0505. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(19): 2129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters M, de Leeuw AAC, Nomden CN, et al. Risk factors for nodal failure after radiochemotherapy and image guided brachytherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer: An EMBRACE analysis. Radiother Oncol 2021; 163: 150–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mileshkin L, Moore KN, Barnes EH, et al. Staging locally advanced cervical cancer with FIGO 2018 versus FIGO 2008: impact on overall survival and progression-free survival in the OUTBACK treial (ANZGOG 0902, RTOG 1174, NRG 0724). J Clin Oncol 2022; 40: 5531-. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tewari KS, Sill MW, Penson RT, et al. Bevacizumab for advanced cervical cancer: final overall survival and adverse event analysis of a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial (Gynecologic Oncology Group 240). Lancet 2017; 390(10103): 1654–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D, et al. Pembrolizumab for Persistent, Recurrent, or Metastatic Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med 2021; 385(20): 1856–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tewari KS, Monk BJ, Vergote I, et al. Survival with Cemiplimab in Recurrent Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med 2022; 386(6): 544–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

De-identified study data are available for sharing. To request access to the de-identified study data, please contact the corresponding author. Requests will be reviewed by the Trial Management Committee and written applications from investigators with the academic capability and credibility to undertake the work proposed will be considered. The scientific merit of the proposal, including the appropriate methods, analysis, and publication plan will be assessed. Consideration will be taken of any overlap with analyses already undertaken or planned to be undertaken by the study team. If a proposal is approved, a signed data transfer agreement will be required before data sharing.