Abstract

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common reasons for consultation in general practice. Currently, LBP is categorised into specific and non-specific causes. However, extravertebral causes, such as abdominal aortic aneurysm or pancreatitis, are not being considered.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed across MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane library, complemented by a handsearch. Studies conducted between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2020, where LBP was the main symptom, were included.

Results

The literature search identified 6040 studies, from which duplicates were removed, leaving 4105 studies for title and abstract screening. Subsequently, 265 publications were selected for inclusion, with an additional 197 publications identified through the handsearch. The majority of the studies were case reports and case series, predominantly originating from specialised care settings. A clear distinction between vertebral or rare causes of LBP was not always possible. A range of diseases were identified as potential extravertebral causes of LBP, encompassing gynaecological, urological, vascular, systemic, and gastrointestinal diseases. Notably, guidelines exhibited inconsistencies in addressing extravertebral causes.

Discussion

Prior to this review, there has been no systematic investigation into extravertebral causes of LBP. Although these causes are rare, the absence of robust and reliable epidemiological data hinders a comprehensive understanding, as well as the lack of standardised protocols, which contributes to a lack of accurate description of indicative symptoms. While there are certain disease-specific characteristics, such as non-mechanical or cyclical LBP, and atypical accompanying symptoms like fever, abdominal pain, or leg swelling, that may suggest extravertebral causes, it is important to recognise that these features are not universally present in every patient.

Conclusion

The differential diagnosis of extravertebral LBP is extensive with relatively low prevalence rates dependent on the clinical setting. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for extravertebral aetiologies, especially in patients presenting with atypical accompanying symptoms.

Keywords: Extravertebral, Non-vertebral, Non-spinal, Low back pain

Background

Fundamentally, low back pain (LBP) represents a symptom rather than an aetiological diagnosis per se. Since establishing a definite pathophysiological diagnosis is often neither necessary nor possible, most clinical guidelines pragmatically distinguish between non-specific LBP, specific LBP, and sciatica/radiculopathy [1]. Furthermore, extravertebral or non-spinal medical disorders may mimic or present clinically as LBP. Consequently, some guidelines recommend considering extravertebral or non-spinal diseases in the differential diagnosis. Recognising extravertebral causes is crucial to avoid misdiagnosis and inappropriate management of potentially life-threatening diseases. In settings where patients have direct access to specialised care, such as orthopaedics and physiotherapy, the likelihood of considering non-musculoskeletal disease may be lower [2]. Deyo and Weinstein once estimated that approximately 2% of patients presenting with LBP in primary care have what they referred to as “visceral” disease. However, this percentage lacks a specific data source [3], yet it has been consistently cited in subsequent literature [4–16]. Within a specialist setting, it has been estimated that up to 10-25% of patients presenting with back pain do not have a vertebral pathology [17].

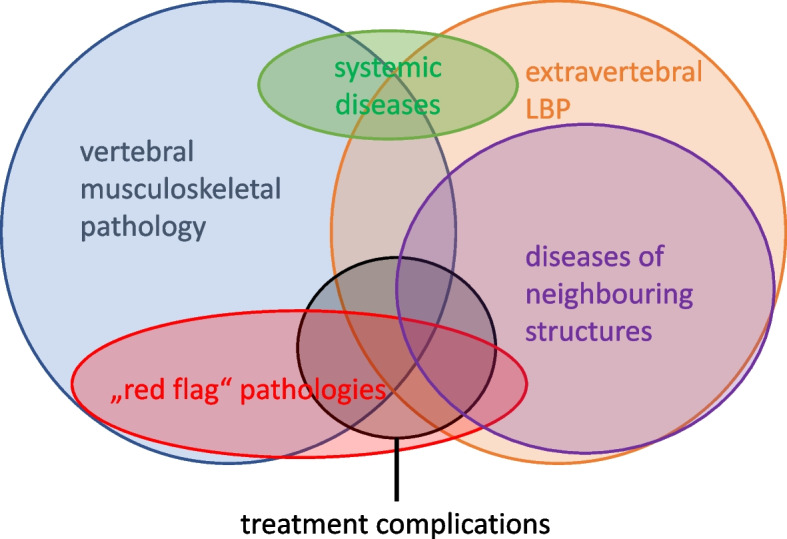

While LBP caused by conditions such as abdominal aortic aneurysm, peripheral arterial disease [18–20], or renal calculus can unambiguously be classified as extravertebral or non-spinal diseases, in many instances, categorisation remains challenging. For example, determining whether conditions involving intramedullary tumours, metabolic diseases (e.g., spinal gout), or hip pathology [21] mimicking radiculopathy should be attributed to spinal or extravertebral causes of pain remains debatable (Fig. 1). At times, these conditions are collectively referred to as unusual or rare causes for LBP [22–34]. The term “extravertebral” or “non-spinal” LBP is anatomically incorrect since it refers only to the bony structures of the back. Currently, there is no consensus on a definition or terminology to classify serious LBP not typically covered by “red flags”. Red flags are warning signs related to pathologies like tumours, fractures, inflammations or infections of the spine [35–37].

Fig. 1.

Overlap of definitions with bubble sizes approximately representing epidemiology. LBP = low back pain

The aim of this scoping review is to summarise what is known on the epidemiology and presentation of extravertebral or non-spinal LBP, in order to help clinicians assessing patients with LBP to recognise when it is appropriate to include this in the differential diagnosis.

Methods

This is a scoping review conducted according to the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (Appendix 1) [38]. Since PROSPERO does not register scoping reviews, a protocol was not registered. A scoping review was chosen due to several factors, including the absence of a universally accepted definition, the broad spectrum of diseases, and the limited existing literature on the topic. Furthermore, this methodology was selected to facilitate a comprehensive overview of the field, identify current research gaps, and provide recommendations for future research.

Search strategy

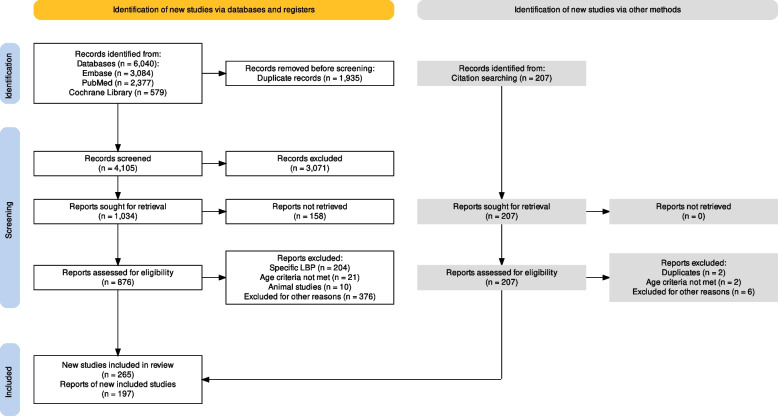

The authors searched three electronic databases (MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Library). In 2001, Deyo and Weinstein published the first major narrative review of extravertebral causes of LBP [3]. Therefore, the search scope was limited to publications from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2020. The detailed search strategy is outlined in Fig. 2, and the specific search terms used are available in Appendix 2. Where required, search terms were amalgamated using Boolean logic and database-specific filters. All publications available in either German or English languages were included.

Fig. 2.

Search flow diagram of the literature review process for studies on extravertebral low back pain according to the PRISMA2020 Statement [39]. LBP = low back pain

Study selection

There is no universally accepted definition allowing to separate “extravertebral” unambiguously from “vertebral” LBP (Fig. 1). Furthermore, the terminologies are not formulated clearly and are insufficient for classifying both included and excluded diseases. Alternatively, the terms “extraspinal” or “non-spinal” back pain are also used. During the review process, the authors encountered difficulties in finding an accurate definition due to overlapping terms and classification systems. Nevertheless, an attempt was made to classify the diseases related to low back pain.

Inclusion criteria comprised publications of case reports, case series, case-control studies, cohort studies, randomised controlled trials, observational studies, and reviews reporting low back pain as a symptom of non-primary vertebral/musculoskeletal disease in adults, including systemic diseases. The MeSH-terms are available in Appendix 2.

Exclusion criteria comprised publications with patients under the age of 18 and pain primarily reported in thoracic and cervical spine. Furthermore, “red flags” indicating pathologies, such as infections, rheumatic diseases, tumours, and fractures were excluded. A complete summary of excluded pathologies can be seen in Appendix 3.

After the removal of duplicates, two authors screened the titles and abstracts independently. The included articles were discussed among the authors according to relevance, data extraction, and quality. Dissents were solved by consensus. This was followed by a handsearch.

Clinical guideline selection

All clinical guidelines listed in the most recent review of LBP guidelines [1] written in English or German language were reviewed to find recommendations regarding extravertebral LBP.

Data extraction

Descriptive characteristics were extracted from each manuscript, including, author’s name(s), year of publication, country, study design and setting. Depending on the type of publication, further data was extracted.

For case reports and case series, extracted data included participant characteristics (sample size, sex, age, and co-morbidities), pain characteristics (acute vs chronic LBP, pain description, neurological and other symptoms), diagnostic characteristics (laboratory results, imaging, biopsy/other diagnostic, diagnostic confirmation, and physical examination) and differential diagnosis.

For case-control or cohort studies, the following data were extracted: data collection (retrospective/prospective), inclusion criteria, baseline, follow-up, LBP (acute/chronic), other symptoms, pain description, differential diagnosis and other information (e.g., epidemiological information, risk factors, and physical examination findings).

For reviews encompassing LBP in general, the following data points were extracted: classification, terminology, causes, estimated prevalence, symptoms pointing toward a non-spinal pathology, diagnostic values (e.g., patient history, physical examination, laboratory results, and imaging) and whether Weinstein and Deyo 2001 was cited or not. If specific pathologies were mentioned, only unique information about LBP associated with those diseases were extracted.

Results

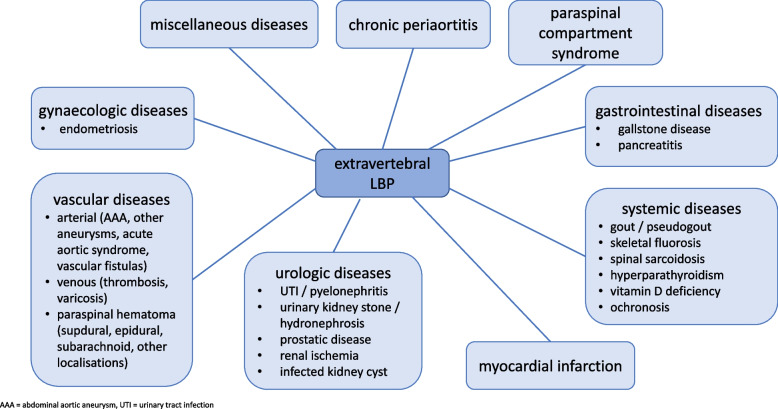

After elimination of duplicates and resolving disagreement between the reviewers, a total of 4105 manuscripts were screened. Additionally, a handsearch was carried out and a further 197 manuscripts were included in the review (Fig. 2), thereby bring the total number of manuscripts included in this review to 462. Various extravertebral causes of LBP were identified and are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Overview: causes of extravertebral low back pain organised by pathologies. AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm. LBP = low back pain. UTI = urinary tract infection

Description of studies

Case reports and case series

Various case reports mentioned LBP as part of the clinical presentation, but it often remained unclear, if LBP was the chief complaint. Case reports, where back pain was mentioned but no connection to the final diagnosis could be made or it seemed that back pain was a coincidence, were excluded. None of the case reports claimed adherence to the standards of reporting from CARE [40].

Case control and cohort studies

Only a few case-control or cohort studies were included. In these studies, various diseases, their therapies, and diagnostic methods were examined. If LBP was reported, comparisons were often made between pre- and post-interventional symptoms to draw conclusions regarding the association between pathology and LBP.

Narrative and systematic reviews

The content of narrative or systematic reviews often dealt with low back pain in general or in association with other pathologies, where LBP was a reported symptom. Reviews of other pathologies often omitted information regarding duration or localisation of LBP, while frequently including associated symptoms.

Guidelines

The included guidelines were examined with regards to the recommendations for dealing with extravertebral low back pain.

Results of the guideline review

Guidelines featured in the latest review of clinical practice guidelines on LBP were examined by Oliveira et al. 2018 [41]. They presented a total of 15 guidelines across various countries, of which 11 guidelines available in German or English were reviewed. Four guidelines mentioned extravertebral, non-vertebral, or systemic causes of LBP. One guideline reported that an “alternative diagnosis” should be considered [42]. The rest did not mention the possibility of an extravertebral origin of low back pain.

Results organised by pathology

Systemic diseases

Spinal gout

Gout is a systemic disease where monosodium urate crystal deposit in various joints, such as, facet, sacroiliac or interverbal joints as well as discs. Rheumatic diseases are pathologies indicated by red flags and usually refer to axial spondyloarthropathies excluding gout. Spinal or axial gout was first described in 1950 [43]. Since then, several case reports and case series have been published (Table 1). Toprover et al. published a review of 131 cases of spinal gout. We decided to disregard all case reports featured in their review in Table 1 [30, 44–52]. Furthermore, many of them were not within the time frame of this review. The majority (roughly 75%) had a history of gout. It is frequently concluded that axial gout is more common than assumed. However, no conclusions about the prevalence of axial gout can be drawn from the case reports and case series. The case series reveal a prevailing trend wherein a significant number of patients with axial gout have a confirmed diagnosis of gout, frequently accompanied by the presence of peripheral tophi. In most cases, the diagnosis was confirmed through intraoperative biopsies or fluoroscopy [43]. The case series conducted by de Mello et al. [53], stands out due to its investigation of spinal computed tomography (CT) scans in individuals who had a confirmed diagnosis of gout. Possible evidence of axial gout was found in 12/42 (29%) and peripheral tophi were associated with CT-findings suggestive for gout. The findings were not associated with current pain. Therefore, the claim that spinal gout is more frequent than assumed is weak, assuming that despite radiological findings, many patients with urate deposition in the spine are asymptomatic.

Table 1.

Case reports of gout presenting with low back pain

| Author / year / country | Setting | Patient | Spinal symptoms | Extraspinal symptoms | Diagnostic confirmation / differential diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardoso et al., 2014, Brazil [54] | ED send by GP | male, 55 y | chronic LBP, paraparesis | fever, no h/o gout, chronic kidney disease, diabetes | elevated ESR, CT-guided biopsy |

| Lu et al., 2017, China [55] | ED | male, 68 y | chronic LBP | no h/o gout | biopsy during surgery |

| Wang et al., 2017, China [56] | ED | male, 62 y | chronic LBP | h/o gout | biopsy during surgery |

| Ribeiro et al., 2018, Portugal [57] | ED | male, 77 y | acute LBP, paraparesis | h/o gout | biopsy during surgery |

| Qin et al., 2018, China [58] | ED | male, 56 y | subacute LBP | h/o gout | biopsy |

| Alqatari et al., 2018, Ireland [59] | specialist care | male, 55 y | chronic LBP | h/o gout, tophi and psoriatic arthropathy with non-response to TNF-blocker | elevated ESR, imaging (MRI, CT) |

| Zou et al., 2019, China [60] | specialist care | male, 55 y | acute LBP | intermittent claudication, h/o gout | elevated ESR, biopsy during surgery |

| Chen et al., 2020, China [61] | ED | male, 55 y | chronic LBP | no h/o gout | biopsy during surgery |

CT computer tomography, ED emergency department, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, GP general practitioner, h/o history of, LBP low back pain, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, TNF-blocker tumour necrosis factor blocker, y years

Pseudogout

Pseudogout is a rare disease with calcium-pyrophosphate deposition, which can affect any joint, including facet joints, causing inflammatory arthritis. Five case reports and case series of pseudogout presenting with low back pain (Table 2) were included. Symptoms are non-specific and diagnosis is usually made incidentally due to suspicious findings leading to operative exploration with biopsies. Only one patient had a history of pseudogout.

Table 2.

Case reports or case series of pseudogout presenting with low back pain

| Author / year / country | Setting | Patient(s) | Presentation / clinical history | Diagnostic confirmation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fujishiro et al., 2002, Japan [62] | ED | female, 71 y | acute LBP, h/o pseudogout, elevated ESR and CRP | joint aspiration |

| Gadgil et al., 2002, UK [63] | ED | female, 67 y | chronic LBP, sciatica, CT-Scan with calcified cyst with nerve compression | biopsy during surgery |

| Mahmud et al., 2005, UK [44] | not reported |

6 patients (4 with gout, 2 with pseudogout): female, 70 y |

subacute LBP, sciatica, MRI-Scan with cyst and nerve compression | biopsy during surgery |

| male, 81 y | chronic LBP, claudication, MRI-scan with severe spinal stenosis due to deformity and cysts | |||

| Namazie et al., 2012, New Zealand [64] | not reported | female, 69 y | subacute LBP, h/o scleroderma, CT-Scan with large, calcified mass | biopsy |

| Shen et al., 2019, China [65] | ED | male, 53 y | chronic LBP, h/o gout, elevated ESR and CRP, CT-Scan with mass and bone destruction of facet joints | biopsy |

CRP c-reactive protein, CT computer tomography, ED emergency department, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, h/o history of, LBP low back pain, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, y years

Skeletal fluorosis

Two case reports were identified where the diagnosis of skeletal fluorosis, contributing to the onset of chronic metabolic bone disease, was associated with chronic LBP (Table 3). Skeletal fluorosis is a rare disease caused by increased ingestion of fluoride. It is endemic in some parts of Asia (e.g., China, India), where elevated fluoride concentrations are found in soil and water. Industrial exposure, accidental ingestion of fluoride containing medication or toothpaste and substance abuse are other possible causes. Mottling of teeth is a clinical sign of excessive exposure to fluoride as an infant. The condition is typically diagnosed incidentally based on osteosclerosis and ligamentous calcification on X-ray. There is no established treatment.

Table 3.

Case reports of skeletal fluorosis presenting with low back pain

| Author / year / country | Setting | Patient | Clinical history | Diagnostic confirmation | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peicher et al., 2017, USA [66] | not reported | male, 33 y | progressive LBP for 3 years | X-ray (generalised osteosclerosis) | fluoride inhalation (huffing of cleaner) |

| Shetty et al., 2015, India [67] | not reported | male, 35 y | compressive myelopathy with paraparesis with LBP for 3 years, mottling of teeth | X-ray (generalised osteosclerosis and calcifications of the longitudinal ligament) | most likely endemic due to increased fluoride in drinking water |

LBP low back pain, y years

Spinal sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease, which most commonly affects the lung. It is estimated that 1-3% of patients with sarcoidosis have some form of osseous disease, which is mostly asymptomatic. A total of 6 case reports highlighting spinal sarcoidosis associated with LBP were included (Table 4). Back pain can be caused by either spinal osseous involvement or medullary disease. Improvement following treatment, e.g., with corticosteroids, has been reported. In some patients, the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was pre-existing, while in other cases, suspicious findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prompted bone biopsies that lead to diagnosis [68, 69]. The radiological findings, however, lack specificity. Given the array of potential differential diagnoses encompassing osseous metastasis, myeloma, lymphoma, tuberculosis, and osteomyelitis, the verification of the diagnosis primarily relied on bone biopsy. No discernible clinical clue beyond a pre-existing diagnosis of sarcoidosis were evident.

Table 4.

Case reports of sarcoidosis presenting with low back pain

| Author / year / country | Setting | Patient | Spinal symptoms | Extraspinal symptoms | Diagnostic confirmation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ludwig et al., 2003, USA [68] | not reported | female, 51 y | LBP (no duration reported) | - | MRI, PET-Scan, bone biopsy |

| Ashamalla et al., 2016, USA [69] | not reported | female, 60 y | LBP (no duration reported) | h/o Crohn’s disease | MRI, PET-Scan, bone biopsy |

| Rice et al., 2011, UK [70] | not reported | female, 62 y | LBP (no duration reported) | h/o sarcoidosis | MRI, bone biopsy, response to therapy with corticosteroids |

| Valencia et al., 2009, USA [71] | not reported | female, 48 y | LBP (no duration reported) | diffuse arthralgia, abdominal pain, dyspnoea | MRI, PET-Scan, bone biopsy |

| Packer et al., 2005, USA [72] | specialist care | male, 47 y | chronic LBP | h/o pulmonary sarcoidosis, weight loss | MRI, PET-Scan, bone biopsy |

| Barazi et al., 2008, UK [73] | not reported | female, 44 y | chronic LBP, altered sensation in the lower limbs | - | MRI, bone biopsy |

h/o history of, LBP low back pain, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, PET positron emission tomography, y years

Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism is another rare condition that can arise from either primary origin, such as, adenomas (and rarely carcinomas), or as a secondary manifestation of end stage kidney disease (ESKD). Presenting complaints typically include general and non-specific symptoms such as weakness, thirst, polyuria, weight loss, and musculoskeletal pain. Only five case reports describing hyperparathyroidism as a cause of LBP were found and included (Table 5). Up to 3% of individuals with hyperparathyroidism will develop brown tumours (osteitis fibrosa cystica), which are neoplastic and can cause LPB and neurological symptoms due to compression if located in the spine. The presence of the mass lesion is typically identified through imaging as a consequence of neurological symptoms [74]. Symptoms suggesting the need to consider hyperparathyroidism in the differential diagnosis include a patient’s previous history of urolithiasis and ESKD in the context of chronic LBP. The diagnosis is likely with elevated serum calcium and alkaline phosphatase, low serum level of phosphate and confirmed by measuring serum hyperparathyroid hormone.

Table 5.

Case reports and reviews of hyperparathyroidism presenting with low back pain

| Author / country / year | Design / setting | Patient(s) | Spinal symptoms | Extraspinal symptoms | Diagnostic confirmation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khalatbari et al., 2014, Iran [74] | CR and | 4 cases with brown tumours (50% females), but only 2 in the lumbar spine | chronic LBP and progressive weakness of the lower extremity, radicular pain | muscular weakness | laboratory work up, surgery |

| review of 15 previously reported CR / not reported | 15 cases of brown tumour, only 6 in the lumbar spine | ||||

| Hoshi et al., 2008, Japan [75] | CR / outpatient clinic | female, 23 y | chronic LBP | h/o urolithiasis | laboratory work up, biopsy |

| Yu et al., 2012, Taiwan [76] | CR / not reported | female, 28 y | chronic LBP | weakness, thirst, constipation, h/o urolithiasis | laboratory work up, surgery |

| Anastasilakis et al., 2011, Greece [77] | CR / outpatient clinic | female, 70 y | chronic LBP, kyphosis | weakness, arthralgias | laboratory work up, surgery |

| Wiederkehr, 2020, USA [78] | CR / not reported | female, 33 y | chronic LBP | end stage kidney disease | laboratory work up, biopsy |

CR case report, h/o history of, LBP low back pain, y years

Vitamin D deficiency / insufficiency

Osteomalacia arises from a deficiency in vitamin D, an essential substance for maintaining bone health, consequently leading to the manifestation of LBP [79]. However, most people with low 25-hydroxyvitamin (25-OH) D3 (calcidiol) level do not develop osteomalacia. A connection between low calcidiol and LBP was initially made by Al Faraj et al. [80], in an observational study, which subsequently resulted in numerous studies (Table 6). The documented deficiency of calcidiol in 83% of individuals experiencing lower back pain (LBP), along with the observed cessation of LBP in all patients with low levels following supplementation within an unspecified time frame, prompted the initiation of cross-sectional and case-control studies into the potential correlation between LBP and vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency. (Table 6). Most studies, except one [81], concluded that vitamin D deficiency was contributing to LBP and even recommended screening patients with chronic LBP. However, no specific symptoms, which could help to identify patients with vitamin D deficiency, were described. Additionally, the definitions of vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency were heterogenous. A Cochrane review on the effectiveness of vitamin D for chronic pain, including LBP, found no consistent evidence for the effectiveness of vitamin D substitution [82].

Table 6.

Studies reporting on vitamin D and low back pain

| Author / country / year | Design / setting | Patients | Inclusion criteria / exclusion criteria | 25-OH Vitamin D3 status | Main finding and conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Faraj et al., 2003, Saudi Arabia [80] |

observational study / specialist clinic |

360 patients (90% female) | LBP, 15-52 years (90 % female), no red flag pathologies, no renal impairment or chronic liver disease | 299 (83%) had low 25-OH-vit D (< 22.5 nmol/L) | substitution of vitamin D: cessation of LBP (95%) (100% with low vitamin D and 69% with normal vitamin D level) |

| Rkain et al., 2013, Morocco [83] |

case control study / specialist clinic |

105 cases / 44 controls (100% female) | postmenopausal women 42-80 years with LBP, no red flag pathologies | 79 % cases vs 61.4 % controls had low vitamin D (<20 ng/ml) | association between vitamin D deficiency and chronic LBP in Moroccan post-menopausal women |

| Johansen et al., 2013, Denmark [81] | cohort study / specialist clinic | 902 patients screened; 152 patients included (48% female) | chronic LBP 19-64 years, no specific LBP, disk herniation or spinal stenosis | 99 (65.1%) had normal vitamin D levels (> 50 nmol/L), 36 (23.7%) had mild vitamin D deficiency (25–50 nmol/L) and 17 (11.2%) patients had moderate/severe deficiency (< 25 nmol/L) | vitamin D deficiency not more common than in the general population, no relation to clinical symptoms |

| Baykara et al., 2014, Turkey [84] |

case control study / specialist clinic |

60 cases (62% female) / 30 controls (63% female) | chronic LBP, 20-50 years, no red flag pathologies | 53 (88%) cases & 11 (37%) controls had low vitamin D (<20 ng/ml) | vitamin D level: significantly lower in the patient group |

| Rehman et al., 2020, Pakistan [85] | cross-sectional observational study / outpatient clinic | 182 patients (36% female) | LBP, no exclusion criteria described | 20 (11%) with vitamin D deficiency (< 50 ng/ml), 132 (74%) with vitamin D insufficiency (< 20 ng/ml) | vitamin D: contributing to LBP; conclusion not justified by study design. |

| Bahinipati et al., 2020, India [86] |

cross-sectional observational study / specialist clinic |

196 patients (61% female) | chronic LBP | 35 (18%) had normal vitamin D levels (> 30 ng/ml), 59 (30%) had insufficiency (21–29 ng/ml) and 52 (52%) had deficiency (< 20 - ng/ml) | pain intensity measured by visual analogue scale score: significantly higher with decrease in vitamin D levels. |

LBP low back pain, 25-OH-vit D 25-hydroxyvitamin D

Ochronosis / Alkaptonuria

Ochronosis, also known as alkaptonuria, is a rare autosomal recessive genetic disorder leading to accumulation of homogentisic acid in the body. Ochronotic arthritis gives rise to chronic back pain typically occurring during the fourth and fifth decade of life, mimicking ankylosing spondylitis including the marked spine stiffness. However, this condition commonly extends its involvement to other joints as well. A total of 12 case reports were found, all focussing on chronic LBP (Table 7). Diagnostic signs, such as pigmentation of the sclera and ear, and darkening of morning urine, were not always present. Intervertebral disc calcification on imaging can be considered pathognomonic and was observed in all case reports. The diagnosis was confirmed with measurement of homogentisic acid in the urine or sometimes from specimens obtained during surgery [87–89]. Only a few patients had been previously diagnosed during childhood, and one patient received a diagnosis during prior surgery.

Table 7.

Case reportsa of ochronosis presenting with chronic low back pain

| Author / country / year | Setting | Patient | Spinal symptoms | Extraspinal symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capkin et al., 2007, Turkey [90] | outpatient clinic | male, 50 y | stiffness, restriction of movements | yellowish green ochronotic pigmentation of cartilage & ears, reduced chest expansion |

| Al-Mahfoud et al., 2008, UK [91] | outpatient clinic | female, 58 y | not reported | darkening of the urine, diagnosis established previously during surgical intervention (hip replacement) |

| Grasko et al., 2009, Australia [92] | outpatient clinic | male, 38 y | progressive severe LBP, decreased lumbar flexion | hip pain, urine discolouration changing to black after prolonged standing, renal colic, passing black calculus, angular pigmentation in sclera and bluish discolouration of auricle |

| Ahmed et al., 2010, Pakistan [93] | not reported | male, 38 y | progressively increasing stiffness, reduced ability to bend forward | degenerative changes of both radiocarpal joints and metatarso-phalangeal joints |

| Effelsberg et al., 2010, Switzerland [94] | outpatient clinic | male, 38 y | limited spine mobility, slight scoliosis | none, diagnosis of ochronosis established in childhood |

| Amiri et al., 2012, Iran [95] | hospital | female, 54 y | severe low back pain and limitation of motion | discolouration of the sclera, knee pain, renal colic and subsequently passing black urine |

| Sebastian et al., 2012, South Africa [28] | rheumatology clinic | male, 46 y | limited extension of the spine | bluish discolouration of the pinnae bilaterally, 2 mm bilateral blue nodules between the joints on the thumbs |

| Seidhamed et al., 2012, Qatar [32] | emergency department | male, 45 y | not reported | generalised joint pain |

| Mirzashahi et al., 2016, Iran [87] | outpatient clinic | male, 51 y | weakness of both lower limbs | none |

| Etzkorn et al., 2014, USA [96] | not reported | female, 55 y | decreased range of motion, morning stiffness, scoliosis | yellowish green ochronotic pigmentation of cartilage and ears, reduced chest expansion |

| Bozkurt et al., 2017, Turkey [89] | outpatient clinic | male, 47 y | tingling, and numbness and weakness in both legs, increased kyphosis | darkening of the urine |

| Alkasem et al., 2019, Irak [88] | not reported | female, 56 y | severe kyphosis, inability to stand straight | hip pain, discoloration of urine that changed to black after urination, three angular pigmentations in sclera and bluish discolouration of auricle |

LBP low back pain, y years

aall reported chronic low back pain

Vascular diseases - arterial

Abdominal aortic aneurysm

An aneurysm is an outward bulging of the vessel wall usually caused by wall weakness. Most aneurysms develop slowly and are initially asymptomatic. Symptoms of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), such as LBP and abdominal pain, can vary depending on the location and type, i.e., acute versus chronic contained ruptured. Several case reports, three cohort studies and nine narrative reviews were identified documenting AAA featuring LBP within the clinical manifestation (Table 8). Mainly middle-aged to older male individuals were affected. Initially 8-18 % of non-inflammatory AAA are symptomatic, while patients with inflammatory AAA exhibit symptoms in 65 to 90% of cases [97]. The majority of symptomatic patients report chronic LBP, occasionally characterised by a progressive exacerbation. Acute or subacute back pain presentations are also possible. The presence of LBP as part of the clinical presentation of an AAA ranged from 32% [98] to 72% [99]. The co-occurrence of LBP and abdominal pain was 29.4% [100]. Furthermore, abdominal pain and a pulsatile abdominal mass in patients with LBP were indicative of the presence of an abdominal aortic aneurysm [97, 99–123]. The presence of the complete triad of LBP or abdominal pain with hypotension and a pulsatile abdominal mass is rather low at 21% [100] and usually observed during rupture [117, 118, 124]. In some cases, history of smoking was reported [97, 102–104, 106, 108, 110, 111, 115, 117, 119, 121–123, 125–132]. Other common risk factors are atherosclerotic disease, hypertension, positive family history for AAA and other aneurysms, collagen vascular disease and Marfan and Ehlers-Danlos-syndromes [106, 117, 119, 121–123, 133].

Table 8.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm presenting with back pain

| Author / year / country | Design / setting | Patient(s) | Spinal symptoms | Extraspinal symptoms | Diagnostic confirmation | Other information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Koteesh et al., 2005, UK [134] | CR / not reported | male, 46 y | acute LBP, numbness (upper left thigh) | - | laparotomy | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA, similar attacks for past years |

| Arici et al., 2012, Italy [135] | CR+NR / not reported | male, 73 y | chronic LBP | uncontrolled hypertension | spinal MRI | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA; review: most prevalent symptom = LBP (78.6%) |

| Aydogan et al., 2008, Turkey [101] | CR / hospital | male, 51 y | chronic LBP | - | MRI | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA; physical examination: pulsatile mass |

| Caynak et al., 2008, Turkey [103] | CR / hospital | male, 75 y | chronic LBP, increased | - | CTA | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA; h/o smoking; physical examination: palpable mass |

| Copetti et al., 2017, Italy [104] | CR / ED | male, 85 y | chronic LBP | - | abdominal CT scan | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA; h/o smoking; physical examination: pulsatile abdominal mass |

| Dobbeleir et al., 2007, Belgium [105] | CR / ambulatory care | male, 79 y | acute LBP | dyspnoea | CT | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA; physical examination: palpable mass |

| Gandini et al., 2007, Italy [136] | CR / hospital | male, 69 y | LBP (no duration reported) | fever |

msC T-guided needle aspiration |

type: chronic contained rupture of AAA |

| Martos et al., 2018, Spain [137] | CR / ambulatory care | male, 73 y | chronic LBP | - | plain radiology | type: AAA without rupture |

| Henderson et al., 2003, USA [125] | CR / ED | male, 67 y | acute LBP | - | CT | type: rupture of AAA; h/o smoking (10 cigarettes per day) |

| Horowitz et al., 2005, Israel [138] | CR / not reported | male, 82 y | LBP (no duration reported) | - | MRI lumbar spine | type: AAA without rupture |

| Jimenez Viseu Pinheiro et al., 2014, Spain [126] | CR / hospital | female, 75 y | chronic LBP, difficulties walking properly | - | CTA | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA; 45-pack-year history |

| Kim et al., 2013, Korea [139] | CR / hospital | male, 73 y | chronic LBP, claudication, left leg paralysis | pitting oedema of both legs | abdominal contrast-enhanced CT | type: AAA without rupture |

| Lai et al., 2008, Taiwan [140] | CR / not reported | male, 67 y | chronic LBP | - | CT and radiography | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA |

| Lucas et al., 2018, Portugal [141] | CR / ED | male, 74 y | acute LBP, radiating | - | abdominal ultrasonography | type: AAA without rupture |

| Mechelli et al., 2008, Italy [127] | CR / ambulatory care | male, 38 y | subacute LBP, unable to run | frequent awakening | CT | type: AAA without rupture; h/o smoking (10 cigarettes per day) |

| Moos et al., 2009, USA [106] | CR / ambulatory care | female, 31 y | chronic LBP | chronic abdominal pain | CT aortogram | type: AAA without rupture; h/o smoking, physical examination: pulsatile abdominal mass |

| Nakano et al., 2013, Japan [142] | CR / not reported | male, 62 y | acute LBP, right leg pain | - | open biopsy | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA |

| Nguyen et al., 2018, Vietnam [107] | CR / not reported | male, 49 y | subacute LBP | - | biopsy, spinal surgery | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA; physical examination: pulsatile abdominal mass |

| Patel et al., 2005, USA [124] | CR / not reported | male, 69 y | acute LBP, radiating, weakness right leg | - | CTA | type: AAA without rupture |

| Seçkin et al., 2006, Turkey [143] | CR / not reported | female, 38 y | acute LBP, difficulty walking, right buttock pain | - | MR | type: AAA without rupture |

| Tan et al., 2019, Singapore [128] | CR / not reported | male, 81 y | acute LBP | hoarseness | CT | type: AAA without rupture; 4-pack / year-history (has quit 35 years ago) |

| Terai et al., 2015, Japan [144] | CR / not reported | male, 89 y | LBP (no duration reported), bilateral weakness in lower extremities | - | CT | type: AAA without rupture |

| Wyngaarden et al., 2014, USA [108] | CR / not reported | male, 58 y | acute LBP | abdominal pain, difficulty falling asleep | CT | type: AAA without rupture; h/o smoking early 1970s, abdominal pulsation |

| Walker et al., 2017, USA [129] | CR / ED | male, 57 y | acute LBP | weight loss | MRI | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA; 20 pack-year history |

| Jukovic et al., 2016, Serbia [130] | CR / hospital | male, 60 y | chronic LBP | - | CT | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA; h/o smoking |

| Alshafei et al., 2015, Bahrain [131] | CR / not reported | male, 63 y | chronic LBP, 1-year history of bilateral intermittent claudication, later: rigors | later: fever, elevated white cell count and a rise of CRP | surgery | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA; h/o smoking |

| Bogie et al., 2008, The Netherlands [109] | CR / ED | male, 55 y | acute LBP, sudden onset, loss of motor function in both legs | nausea, abdominal pain, 3 days previously: abdominal discomfort and nausea | CT | type: AAA without rupture; no h/o smoking; used antihypertensive medication |

| Chieh et al., 2003, USA [145] | CR / ambulatory care | female, 23 y | back pain (no duration or localisation reported) | dyspnoea on exertion | CT | type: multiple isolated aneurysms in Takayasu’s aortitis |

| De Boer et al., 2010, The Netherlands [110] | CR / ambulatory care | male, 74 y | chronic LBP (slowly developing, 5/10 pain scale, radiating to the knee, worsening with walking, standing, stair climbing, diminished when lying down) | later: abdominal pain while lying supine, aggravated by lying – sharp intermittent pain | ultrasound, surgery | type: AAA without rupture; previous treatments without permanent results, heavy prior cigarette use but stopped 15 years ago |

| Defraigne et al., 2001, Belgium [146] | CR / not reported | 5 patients (1 with LBP): male, 73 y | subacute LBP (sciatic pain), crural neuropathy | - | CT, ultrasound | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA; no inflammatory syndrome, no vertebral erosion |

| Dorrucci et al., 2001, Italy [147] | CR / hospital | female, 87 y | subacute back pain (no localisation reported) | mild jaundice, abdominal fullness, dyspepsia | CT, surgery | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA |

| Lombardi et al., 2016, Brazil [113] | CR / ED | male, 66 y | back pain (no duration or localisation reported), exacerbation, unsteady gait | lower left quadrant pain | CT | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA |

| Sakai et al., 2007, Japan [148] | CR / not reported | male, 72 y | chronic LBP | - | CT | type: chronic contained rupture of AAA |

| Whitwell et al., 2002, UK [149] | CR / ED | male, 70 y | acute back pain (no localisation reported), loss of power and sensation in both legs | collapse | laparotomy | type: AAA with rupture |

| Kamano et al., 2005, Japan [150] | CR / hospital | male, 40 y | LBP (no duration reported) (mild), bilateral lower limb paralysis | - | surgery | type: AAA with rupture |

| Hocaoglu et al., 2007, Turkey [115] | CR / not reported | male, 67 y | chronic LBP (radiating to the abdomen and shoulder, pressure sensation towards rectum, increasing at night), difficulty walking | flushing, sweating, abdominal distension associated with pain, weight loss (3 kg in 3 weeks) | ultrasound, CT / MRI | type: AAA without rupture; h/o smoking, LBP resistant to medication and rest |

| Metcalfe et al., 2016, USA [100] | CHS / hospital | 85 (17.6% female), median age: 76 y | LBP (54.1%) (no duration reported) | abdominal pain (61.2%), groin pain (11.8%), atypically distributed pain (8.2%), loin pain (4.7%), palpable AAA (70%), distracting symptoms (38.8%), hypotension (37.6%), LOC (36.5%), tachycardia (18.8%), gastrointestinal symptoms (17.6%) | - | combination of abdominal and LBP (29.4%), complete triad of back or abdominal pain, hypotension, and palpable mass (21%) |

| Takeyachi et al., 2006, Japan [98] | CHS / hospital | 34 (5.9% female), median age: 72 y | LBP (32%) (no duration reported) | not reported | - | - |

| Tsuchie et al., 2013, Japan [151] | CHS / hospital | 23 (34.8% female), mean age: 77 y | LBP (52.2%) (no duration reported) | not reported | - | - |

| Crawford et al., 2003, Australia [116] | NR / - | - | mostly asymptomatic at the beginning; most common symptom: LBP (no duration reported) | fullness or pulsations in the abdomen, abdominal pain | diagnostic methods: physical examination (tender, palpable, pulsatile abdominal mass and bruit) | 91% with symptoms at first presentation |

| Anderson et al., 2001, USA [117] | NR / - | age: 50-60 y, male:female = 5:1 | back pain radiating to abdomen, back pain in case of vertebral body erosion (no duration or localisation reported) | palpation of a pulsatile abdominal mass, vague abdominal pain with radiation to flank, groin; early satiety / nausea / vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding (in case of fistula), lower extremity ischaemia, venous thrombosis, flank / groin pain | diagnostic methods: US = preferred first method, diagnostic confirmation: CT / CTA or MRI / MRA | risk factors: cigarette use, hypertension, coronary artery disease, COPD, hyperlipidaemia |

| Assar et al., 2009, USA [118] | NR / - | - | severe back pain (no duration or localisation reported), chronic contained rupture: chronic LBP may radiate to the groin, maybe lumbar vertebral erosion, lumbar spondylitis-like symptoms; unusual: transient lower limb paralysis; chronic contained rupture: left lower limb weakness or neuropathy, crural neuropathy | right hypochondrial pain, nephroureterolithiasis, groin pain, testicular pain, testicular ecchymosis (blue scrotum sign of Bryant), iliofemoral venous thrombosis, inguinoscrotal mass mimicking a hernia; chronic contained rupture: left psoas muscle haematoma and obstructive jaundice | diagnostic methods: physical examination (pulsatile epigastric mass); diagnostic confirmation: CT | - |

| Isselbacher et al., 2005, USA [119] | NR / - | - | acute LBP, typically steady and gnawing lasting hours to days | pain (hypogastrium) | diagnostic methods: physical examination (pulsatile abdominal mass), ultrasound, CT / CTA, MRI | risk factors: cigarette use, age, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, atherosclerosis, positive family history for AAAs, male:female = 10:1, abrupt onset associated with rupture |

| Kumar et al., 2017, USA [120] | NR / - | - | back pain (no duration or localisation reported) | mostly asymptomatic and often incidentally detected; unruptured aneurysms (uncommonly abdominal pain or a pulsatile mass), ruptured aneurysms (severe abdominal pain, hypotension and shock, high mortality: 59-83%) | diagnostic methods: ultrasound, CT / CTA, MRA, DSA | - |

| Metcalfe et al., 2011, UK [133] | NR / - | - | back pain (no duration or localisation reported) | from asymptomatic to showing overt signs of rupture; pain in the abdomen or loin; distal embolisation | diagnostic methods: physical examination (pulsatile mass), ultrasound | risk factors: age, positive family history (not otherwise specified), male sex, cigarette use, hypertension, ethnicity (white > Asian), diabetes) |

| Sakalihasan et al., 2005, Belgium [122] | NR / - | male: 1.3-8.9%, female: 1.0-2.2% | LBP, recent onset, severe (no duration reported) | non-ruptured: generally asymptomatic, essentially diagnosed incidentally; chronic vague abdominal pain, ureterohydronephrosis; ruptured: sudden-onset pain in the mid-abdomen or flank, shock, pulsatile abdominal mass | diagnostic methods: physical examination (pulsatile abdominal mass), CT / CTA, MRI / MRA, aortography | risk factor: cigarette use, familial clustering; causes: trauma, acute infection, chronic infection, inflammatory diseases, connective tissue disorders (Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos-syndrome) |

| Rogers et al., 2004, USA [123] | NR / - | 4-8% older than 65 y have an AAA | back pain (no duration or localisation reported) | chest pain and neurological abnormalities, chest pain in association with abdominal pain and chest pain that radiates into the back | - | reasons for delayed diagnosis: absence classic triad; risk factors: atherosclerotic diseases, advanced age, cigarette use, male sex, hypertension, strong familial association, patients with connective tissue disorders (Ehlers-Danlos, Marfan), white race; DDx: urological diseases, gastrointestinal bleeding, neuropathy, diverticulitis |

| Winters et al., 2006, USA [9] | NR / - | male:female = 10:1, advanced age | more commonly: back pain, lower-extremity paraesthesia | triad of hypotension, abdominal pain, and a pulsatile abdominal mass (< 50% of patients); flank pain, left lower-quadrant pain, syncope | diagnostic methods: physical examination (palpable pulsatile mass, abdominal bruit, diminished lower-extremity pulses, tender left lower-quadrant mass) | risk factors: hypertension, h/o tobacco use, hyperlipidaemia, atherosclerotic vascular disease, diabetes, connective tissue disorders, positive family history for AAA |

AAA abdominal aortic aneurysm, CHS cohort study, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CR case report, CRP c-reactive protein CT computed tomography, CTA computed tomography angiography, DSA digital subtraction angiography ED emergency department, h/o history of, LBP low back pain, LOC loss of consciousness, MR magnetic resonance, MRA magnetic resonance angiography, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, msCT multi-slice computed tomography, NR narrative review, US ultrasound, y years

In summary, in middle-aged and elderly males with chronic back pain and a pulsatile mass, abdominal pain, or other present risk factors, an AAA should be considered. The median time to diagnosis of an AAA is 7.3 years [99], with imaging studies (CT, MRI) typically used to confirm the diagnosis. In patients presenting with LBP as chief complaint and without other accompanying symptoms, an AAA is usually an incidental finding in lumbar radiographs [124]. Subsequent differential diagnoses include spinal tumours, metastasis, retroperitoneal tumours, iliopsoas muscle abscess, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis and osteomalacia [103], especially when AAA leads to vertebral erosion.

Other aneurysms

A total of twelve case reports and a cohort study revealed instances of patients with aneurysms in locations other than the abdominal artery experiencing LBP as part of their clinical presentation (Table 9). Visceral artery aneurysms, for example, account for 1-2 % of non-aortic aneurysms. Of these, 60% affect the splenic artery [152]. Here, LBP was mostly described as acute pain [25, 153–159]. Extraspinal symptoms varied depending on the location of the aneurysm. For example, a splenic artery aneurysm showed gastrointestinal symptoms [152], while an aneurysm of the artery of Adamkiewicz showed neurological/vegetative symptoms [153]. The aetiology of non-aortic aneurysms is diverse and also includes infections, such as Takayasu arteritis, albeit rarely [154]. Moreover, additional underlying diseases can further contribute. For example, the majority of intercostal artery aneurysms arise in association with neurofibromatosis.

Table 9.

Other aneurysms presenting with back pain

| Author / year / country | Design / setting | Patient(s) | Affected artery | Spinal symptoms | Extravertebral symptoms | Diagnostic confirmation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanschke et al., 2002, Germany [152] | CR / hospital | male, 46 y | splenic artery | chronic LBP, left sided, analgesic resistant | feeling full, stool irregularities | CT |

| Iihoshi et al., 2011, Japan [153] | CR / hospital | female, 60 y | artery of Adamkiewicz | acute LBP, severe, left lower limb pain | headache, nausea | CT, DSA |

| Kellner et al., 2019, Germany [25] | CR / hospital | male, 38 y | 7. and 8. intercostal artery | acute LBP, immobilisation, increase in vigilance | vomiting, general malaise | CT |

| Matsumoto et al., 2015, Japan [154] | CR / hospital | female, 51 y | superior mesenteric artery | acute LBP | sustained fever | angiography |

| Nakamura et al., 2020, Japan [155] | CR / not reported | male, 66 y | artery of Adamkiewicz | acute LBP, progressive posterior cervical pain | fever | DSA |

| Nogueira et al., 2010, USA [156] | CR / not reported | male, age not reported | lateral sacral artery | acute LBP, lower extremity paraesthesia, weakness, numbness of the genitalia | urinary hesitance | angiography |

| Ferrero et al., 2001, Italy [160] | CR / hospital | male, 43 y | splenic artery | back pain (no duration or localisation reported) | severe state of shock, abdominal pain | CT |

| Takebayashi et al., 2020, Japan [157] | CR / hospital | female, 67 y | ruptured posterior spinal artery aneurysm | acute LBP, worsened with movement, right thigh pain | sudden nausea | MRI + CE-CT |

| Bushby et al., 2010, Australia [159] | CR / ED | male, 67 y | iliac artery aneurysm | acute LBP, left sided, radiation into the left leg, numbness, weakness | weight loss (10 kg in 3 months), no bowel movements since symptom onset | CT |

| Bell et al., 2014, USA [158] | CR / ED | female, 68 y | ruptured posterior spinal artery pseudoaneurysm | acute LBP (severe, sharp, developed suddenly during physical exertion) | - | MRI/MRA |

| Caglar et al., 2005, Turkey [161] | CR / ED | female, 74 y | ruptured posterior spinal artery of the conus medullaris | LBP (severe, no duration reported), radiation into the right leg | - | DSA, histopathological examination |

| Gonzalez et al., 2005, USA [162] | CR / hospital | 4 (all male), mean age: 56 y | spinal aneurysms | acute onset of back pain (no localisation reported), paraesthesia of lower extremities (sometimes bilateral), radicular pain | presented with ruptured aneurysms, spinal SAH concomitant headache (bilateral) | - |

| Knol et al., 2002, Belgium [163] | CHS / hospital | 51 (2% female), mean age: 69.1 y | aortic or iliac | 39% acute LBP (or abdominal pain) | 12% haemorrhagic shock, 49% haemorrhagic shock and abdominal pain or LBP | - |

CE-CT contrast enhanced computed tomography, CHS cohort study, CR case report, CT computed tomography, DSA digital subtraction angiography, ED emergency department, LBP low back pain, MRA magnetic resonance angiography, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, SAH subarachnoid haemorrhage, y years

Acute aortic syndrome

The acute aortic syndrome includes pathologies, such as aortic dissection (AD), intramural haematoma (IMH), and penetrating aortic ulcer (PAU). An aortic dissection is a tear in the inner wall of the aorta, which is potentially life-threatening and often occurs in patients with underlying diseases that weaken the aortic wall, e.g., hypertension, atherosclerosis, and AAA. A distinction is made between type A und type B dissection. Type A is a proximal aortic dissection involving the ascending aorta, while type B affects the descending aorta. The IMH is an atypical aortic dissection and characterised by bleeding into the aortic wall without an intimal tear. A PAU is an ulcerative defect of the intima of the aorta, which breaks through the internal membrane into the tunica media. Acute aortic syndromes usually present with sudden onset of symptoms, like devastating chest pain, which can radiate into the back, including the lower back, and mainly affect middle-aged men. Eleven case reports, two case series, ten cohort studies, nine register studies, a chart review study, an interventional study, thirteen narrative and one systematic review have documented acute aortic syndrome concomitant with LBP (Table 10). Wu et al. published a systematic review and meta-analysis which examines various studies on acute aortic syndrome (partly included in Table 10), where the incidence of back pain varies greatly between 10 % and 75% [164]. Most patients present with a sudden onset of acute severe LBP (pain scale: 7/10, [165]). Possible accompanying symptoms are chest discomfort, abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting, and dyspnoea [9, 166–204]. To confirm the diagnosis, imaging studies, such as computed tomography angiography (CTA), are used [167, 170, 189, 194, 205–208].

Table 10.

Acute aortic syndrome presenting with back pain

| Author / year / country | Design / setting | Patient(s) | Spinal symptoms | Extravertebral symptoms | Diagnostic confirmation | Other information / comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fojtik et al., 2003, USA [166] | CR / ED | male, 48 y | acute LBP (sharp, sudden onset, radiating into the groin) | diaphoresis, dyspnoea, nausea | CT | h/o smoking cigarettes |

| Hughes et al., 2016, USA [205] | CR / ED | female, 56 y | acute LBP, bilateral lower extremity paraesthesia and paralysis | - | CTA | h/o smoking cigarettes |

| Itoga et al., 2017, USA [167] | CR / not reported | male, 59 y | acute LBP, left sided pain and paraesthesia, bilateral buttock stabbing discomfort, resting pain in thigh and calf | abdominal discomfort (radiating to the back) | CTA | - |

| Johnson et al., 2008, USA [165] | CR / ED | male, 49 y | acute LBP (7/10 NRS, intensifying with prolonged periods of sitting still, moderate breathing difficulties) | - | CT | hypertension |

| Hsu et al., 2008, China [209] | CR / ED | male, 32 y | acute LBP (acute onset developed during the night) | - | CT | - |

| Sixsmith et al., 2005, USA [169] | CR / ED | male, 27 y | acute LBP (radiating from upper abdominal area) | diffuse abdominal cramping, bloody diarrhoea, frank blood per rectum | autopsy | - |

| male, 60 y | acute LBP, severe left sided flank pain | - | autopsy | hypertension | ||

| Stäubli et al., 2004, Switzerland [210] | CR / ED | male, 49 y | acute LBP (sudden, severe, later radiating to the abdomen) | pale, sweating | spiral CT, MRI | h/o smoking cigarettes |

| Takahashi et al., 2017, Japan [170] | CR / hospital | male, 73 y | acute LBP (severe) | chest pain | CTA | hypertension |

| Morris-Stiff et al., 2008, UK [211] | CR / ambulatory care | male, 47 y | acute LBP (acute onset, commenced during coitus, radiating down the right leg, increased, claudication-type pain) | - | CT, TTE | hypertension and hyperlipidaemia |

| Furui et al., 2012, Japan [199] | CR / hospital | male, 83 y | acute back pain (no localisation reported) | chest pain | CT | - |

| Ahmed et al., 2012, UK [206] | CR / ED | male, 45 y | acute LBP, weakness in lower limbs | collapse | CTA | h/o smoking cigarettes, family history of ischaemic heart disease |

| Asouhidou et al., 2009, Greece [175] | CS / ED | 49 (16.3% female), mean age: 54.8 y | back pain (no duration or localisation reported) with chest pain (8.1%), paralysis of lower extremities (4.1%), hemiparesis (2%) | only chest pain (36.7%), chest pain with neurological deficit (12.2%), chest pain with syncope (8.1%), chest pain with CHF (6.1%), CHF (10.2%), syncope (6.1%), intubated (4.1%), syncope with pulselessness of the lower extremities (2%) | - | - |

| Nathan et al., 2012, USA [202] | CS / hospital | 315 (39.8% female), mean age: 73.2 y | back pain (or chest pain) (11%,) (no duration or localisation reported) | chest pain | - | - |

| Kalko et al., 2008, Turkey [171] | CHS / hospital | 8 (12.5% female), mean age: 62.5 y | severe back pain (and abdominal pain) (57%) (no duration or localisation reported), acute ischaemia with paraplegia of the lower limb (14.3%) | abdominal pain, haemodynamic collapse, and shock (28.6%) | - | - |

| Hsu et al., 2005, Taiwan [172] | CHS / hospital | 107 (23.4% female), mean age: 58.4 y | back pain (or chest pain) (91.6%) (no duration or localisation reported) | intramural haematoma (12.1%), leg ischaemia (8.4%), hypotension / shock (0.9%) | - | - |

| Li et al., 2012, China [173] | CHS / hospital | 1812 (total: 22.5% female), mean age: 51.1 y | acute back pain (69.1%) (no localisation reported), other neurological deficits (1.5%) | pain (88.1%), abrupt onset (70.3%), anterior chest pain (69.4%), abdominal pain (12.3%), migrating pain (8.7%), leg pain (1.7%), pulse deficit (14.1%), aortic regurgitation murmur (9.2%), syncope (5.7%), shock (5.3%), stroke (5.0%), heart failure (4.1%), systolic blood pressure (143.2 +/- 24.4), diastolic blood pressure (81.8 +/- 13.8) | - | - |

| Xu et al., 2006, China [212] | CHS / hospital | 63 (6.3% female), mean age: 50.4 y | back pain (100%) (no duration or localisation reported) | shock (3.2%), hoarseness (1.6%) | - | - |

| Falconi et al., 2005, Argentina [174] | CHS / hospital | AD: 76 (34% female), mean age: 69 y, IMH: 27 (30% female), mean age: 71 y | acute back pain (72%) (no localisation reported) | abrupt onset of pain (85%), chest or back pain (25%) | - | - |

| Sen et al., 2020, USA, Switzerland [200] | CHS / hospital | 14 (29% female), median age: 73 y (range: 44-90 y) | acute back pain (7%) (no localisation reported) | abdominal pain (14%), hypotension (7%) | - | - |

| Ho et al., 2011, China (Classic AD) [201] | CHS / hospital | classic AD: 56 (32.1% female), mean age: 60.5 y | back pain (64.3%) (no duration or localisation reported) | chest pain (75%), abdominal pain (23.2%), stroke (21.4%) | - | - |

| IMH: 34 (47.1% female), mean age: 69.7 y | back pain (64.7%) (no duration or localisation reported) | chest pain (70.6%), abdominal pain (26.5%), stroke (0%) | - | - | ||

| Jansen Klomp et al., 2016, Netherlands [184] | CHS / hospital | 200 (39% female), mean age: 64 y |

comparison between part of first DDx (fDDx) and not part of first DDx (nfDDx): back pain: (fDDx: 56.1%, nfDDx: 31%) (no duration or localisation reported), focal neurological deficit (fDDx: 15.8%, nfDDx: 9.9%) |

chest pain (64.7% vs 61.3%), abdominal pain (23.7% vs 24.0%), TLOC (19.5% vs 10.7%), coma (12.1% vs 10.7%); signs: any pulse deficit (27.7% vs 9.9%), median heart rate (73 vs 78), median blood pressure (120/104 vs 120/102), median haemoglobin (7.8 vs 8.0), median creatinine (104 vs 102) | - | - |

| Collins et al., 2004, USA [185] | CHS / hospital | 617 (100 with previous surgery (w), 517 without previous surgery (wo)), female (overall: 33.1%), mean age overall: 61.1 y | back (or chest pain) (overall: 84.6%, w: 67.4%, wo: 87.9%) (no duration or localisation reported), abrupt onset of back or chest pain (overall: 91%, w: 83.9%, wo: 92%) | migrating pain (overall: 14.8%, w: 8.8%, wo: 15.9%) | - | - |

| Imamura et al., 2011, Japan [186] | CHS / hospital |

98, painless (pl): 16 (44% female, mean age: 71 y), painful (pf): 82 (46% female, mean age: 65 y) |

pf: back pain (60%) (no duration or localisation reported), focal neurological deficit (pl: 19%, pf: 2%), weakness of lower extremities (pl: 6%, pf: 12%) | chest pain (71%), abdominal pain (27%), disturbance of consciousness (transient: pl: 25%, pf: 1%; persistent: pl: 44%, pf: 6%), dyspnoea (pl: 6%, pf: 2%), nausea and vomiting (pl: 6%, pf: 7%), abdominal fullness (pl: 6%, pf: 0%), bleeding tendency (pl: 6%, pf: 0%), pyrexia (pl: 0%, pf: 2%), haematemesis (pl: 0%, pf: 1%) | - | - |

| Januzzi et al., 2004, USA [176] | register study / hospital |

1049 (Marfan (marf): 5.1%, non-Marfan (nmarf): 94.9%); marf: 26% female, mean age: 35 y; nmarf: 32% female, mean age: 64 y |

LBP (marf: 60%; nmarf: 55%) (no duration reported) | chest pain (marf: 75%, nmarf: 76%), migrating pain (marf: 16%, nmarf: 18%), syncope (marf: 10%, nmarf: 13%), congestive heart failure (marf: 10%, nmarf: 5%), coma / altered consciousness (marf: 6%, nmarf: 10%), systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg (marf: 27%, nmarf: 44%), diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg (marf: 19%, nmarf: 23%), murmur of aortic regurgitation (marf: 46%, nmarf: 32%) | - | - |

| Nallamothu et al., 2002, USA [177] | register study / hospital | 728 (31% female), mean age: 63 y | back pain (or chest pain) (83%) (no duration or localisation reported) | syncope (13%) | - | - |

| Nienaber et al., 2004, Germany [178] | register study / hospital | 1078 (32.1% female), mean age: 62.4 y) | back pain (54.4 %) (no duration or localisation reported), any focal neurological deficits (14.3%), ischaemic peripheral neuropathy (2%) | abrupt onset of pain (87.1%), chest pain (75.5%), migrating pain (17.9%), hypotension / shock / tamponade (19.2%), syncope (13.1%), shock / tamponade (11.5%), coma / altered consciousness (10.3%), shock (10.0%), congestive heart failure (6.6%), cardiovascular accident (6.1%), tamponade (3.6%), mean systolic BP (142 +/- 43), mean diastolic BP (82 +/- 23), any pulse deficit (27.7%) | - | - |

| Suzuki et al., 2003, Germany [179] | register study / hospital | 384 (28.6% female), mean age: 64.4 y | back pain (and / or chest pain) (86%) of abrupt nature (89%) (no duration or localisation reported) | migrating pain (uncommon, 25%), hypertension (69%), pulse deficits (21%), spinal cord ischaemia (3%) hypotension / shock (3%) | - | - |

| Bossone et al., 2013, Italy [180] | register study / hospital | 1354 (36.4% female), mean age: 62.8 y | back pain (59.6%) (no duration or localisation reported) | any pain reported (93.8%), abrupt onset (83%), chest pain (73%), radiating pain (44.1%), abdominal pain (32.6%), migrating pain (7%), syncope (10.3%) | - | - |

| Evangelista et al., 2005, USA [181] | register study / hospital | classic AD: 952 (30.9% female, mean age: 61.7 y); IMH: 58 (39.7% female, mean age: 68.7 y) | acute back pain (no localisation reported): AD: 54.2%; IMH: 63.8%; abrupt onset described | abrupt onset (AD: 87.3% / IMH: 87.5%), chest pain (AD: 75.6% / IMH: 75.9%), pain rated as worst ever (AD: 20.0% / IMH: 39.6%), abdominal pain (AD: 28.2% / IMH: 31.0%), pain migration (AD: 18.2% / IMH: 15.5%), leg pain (AD: 10.8% / IMH: 1.7%) | - | - |

| Harris et al., 2012, USA [182] | register study / hospital | type A: AD: 1744 (32.3% female, mean age: 61.4 y), IMH: 64 (42.2% female, mean age: 69.6 y); type B: AD: 651 (33.5% female, mean age: 62.9 y), IMH (34.4% female, mean age 68.6 y) | back pain (no duration or localisation reported) (type A: AD (42.8%), IMH (41.0%); type B: AD (70.3%), IMH (78.7%)) | pain severity - severe or worst ever pain (type A: AD (91.6%), IMH (98.1%); type B: AD (93.6%), IMH (94.7%)), abrupt onset of pain (type A: AD (82.6%), IMH (86.7%); type B: AD (87.4%), IMH (82.6%)), chest pain (type A: AD (81.5%), IMH (82.5%); type B: AD (67.4%), IMH (77.3%)), radiating pain (type A: AD (36.3%), IMH (45.9%); type B: AD (44.7%), IMH (35.3%)), abdominal pain (type A: AD (26.0%), IMH (13.1%); type B: AD (43.9%), IMH (36.8%)) | - | - |

| Vagnarelli et al., 2015, Italy [183] | register study / hospital | 398 (33.2% female), mean age: 66.7 y | back pain (48.7%) (no duration or localisation reported) | chest pain (65.6%), abdominal pain (27.6%), migratory pain (12.8%), autonomic symptoms (38.9%), dyspnoea (14.6%), shock within 12 hours of admission (14.3%), pain + shock (11.1%), pain + syncope (8.5%), pain + cerebrovascular accident (3.0%), pain + paraplegia (2.5%) | - | - |

| Wang et al., 2014, China [204] | register study / hospital | Sino-RAD: 1003 (22.2% female), mean age: 51.8 y; IRAD: 464 (34.7% female), mean age: 63.1 y | back pain (no duration or localisation reported) (Sino-RAD: 77%, IRAD: 53.2%) | any pain reported (Sino-RAD: 89.6%, IRAD: 95.5%), abrupt onset (Sino-RAD: 68.5%, IRAD: 84.8%), chest pain (Sino-RAD: 17.3%, IRAD: 72.7%), abdominal pain (Sino-RAD: 12%, IRAD: 29.6%), syncope (Sino-RAD: 2.1%, IRAD: 9.4%), heart failure (Sino-RAD: 0.2%, IRAD: 6.6%) | - | - |

| Tsai et al., 2009, Taiwan [203] | chart-review study / hospital | 18 (16.7% female), mean age: 32 y | LBP (11.1%) (no duration reported) | chest pain and / or tightness (38.9%), chest-back pain (27.8%), epigastric pain (11.1%), abdominal pain (5.6%), lower limb weakness or numbness (11.1%), sudden cardiac arrest (5.6%) | - | - |

| Li et al., 2010, China [187] | interventional study / hospital | stent graft: 33 (27% female, mean age: 60 y); treated medically: 23 (35% female, mean age: 56 y) | back pain (or chest pain) (100% of all patients) (no localisation or duration reported) | - | - | - |

| Léon Ayala et al., 2011, Taiwan [188] | NR / - | male (68%) > female (32%) | acute back pain (no localisation reported), sudden onset, neurological deficits: paraplegia | most common symptom: sudden onset of severe chest pain, radiating to neck or shoulders; hypotension and / or shock (type A), hypertension (type B); other findings: fever, diaphoresis, absence of pulse, cerebrovascular manifestations, acute abdominal pain, aortic regurgitation related to cardiac failure, cardiac tamponade, syncope | diagnostic methods: laboratory testing, ECG, TEE / TTE, CT, MRI, aortography, chest x-ray | diagnosis was missed up in 38%; signs: pulse deficit (< 20%), diastolic murmur, jugular venous distention, distant heart sounds, pulsus paradoxus, ostium or coronary artery involved (7%); risk factors: cocaine, pregnancy, iatrogenic trauma |

| Golledge et al., 2008, USA [189] | NR / - | incidence: 3 / 100000 people per year, age: 61-65 y, male > female | back pain (or chest pain) (85%) (no duration or localisation reported), abrupt onset; any focal neurological deficit (12%) | severe or worst-ever pain (90%), abrupt onset of pain (90%), pain presenting within 6 hrs. of symptom onset (79%), abdominal pain (30%), migrating pain (19%), hypertension at presentation (49%), aortic regurgitation (32%), any pulse deficit (27%), hypotension / shock / tamponade (18%) | diagnostic methods: laboratory testing, ECG, chest radiograph, CT, echocardiography, CTA, MRI | risk factor: hypertension |

| Khan et al., 2002, USA [190] | NR / - | male > female, mean age: 50-55 y proximal and 60-70 y distal; patients with Marfan syndrome tend to be younger | back pain (53%) (no duration or localisation reported, depending on location of dissection); cerebral ischaemia / stroke (5-10%), spinal cord ischaemia / ischaemic peripheral neuropathies (up to 10%), various spinal cord syndromes | pain (95%) (typically catastrophic / abrupt onset (85%), sharp (64%), ripping or tearing (51%) or knife-like in nature (no percentage reported)), chest pain (73%), abdominal pain (30%), acute cardiac decompensation and shock, hypotension and shock, pericardial effusion, obstruction of the superior vena cava or from cardiac tamponade, neurological deficits (18-30%), syncope (12%), acute GI haemorrhage / acute abdomen / dysphagia; signs: aortic regurgitation (18-50%), diastolic murmur (25%), systolic BP < 100 mmHg (25%), left ventricular regional wall motion abnormalities (10-15%), low coronary perfusion, pulse differential (38%), bruits | diagnostic methods: TEE, CT, MRI, chest radiograph, TTE, aortography, serum smooth muscle myosin heavy chain | predisposing factors: hypertension, aortic disease, direct iatrogenic trauma, cocaine, pregnancy |

| Mussa et al., 2016, USA [191] | SR / - | patients with AAD: median age: 61 y, 19-50% female; incidence 15/100000 patient-years | back pain (or chest pain) (84.8%) (no duration or localisation reported); stroke (11.3%) | sharp pain (64.4%); weak carotid, brachial or femoral pulse (pulse deficit) (30%), hypotension (> 25%), syncope (13%), regurgitation murmur (31.6%), abdominal pain (type B: 42.7%, type A: 21.6%), IRAD (syncope (33.9%), congestive heart failure (19.7%), painless aortic dissection (6.4%)) | diagnostic methods: ECG, chest x-ray, CT / MRI, TEE, serologic biomarkers (e.g., d-dimer) | most common comorbidity: hypertension (45-100%), h/o smoking (20-85%), chronic renal insufficiency (3-79%), COPD (5-36%), stroke / transient ischaemic attack (0-20%); |

| patients with IMH | back pain (61.6%) (no duration or localisation reported) | abrupt chest pain (77.9%), hypertension (68-96%) | diagnostic methods: CT / MRI = gold standards | smokers: 18-67% | ||

| Nienaber et al., 2002, Germany [192] | NR / - | - | back pain (no duration or localisation reported) | chest pain | - | risk factors: hypertension (85%), coronary artery disease (61%), abdominal or thoracic aneurysm (53%, chronic renal insufficiency (31%), peripheral artery disease (17%), cerebrovascular accidents (12%) |

| Nienaber et al., 2003, Germany [193] | NR / - | IMH prevalence: 10 – 30 % | instantaneous onset of severe back pain (64%) (no localisation reported); stroke (21%), peripheral ischaemic neuropathy (encountered on occasion) | chest pain (63%), sudden abdominal pain (43%), ischaemic leg (encountered on occasion) | diagnostic methods: physical examination (pulse deficits: <20%, diastolic murmur: 40-50%), chest x-ray, ECG, TTE, TEE, CT, MRI, angiography | risk factors: smoking, dyslipidaemia, cocaine / crack, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos-syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, coarctation, giant cell arteritis, Takayasu arteritis, Behcet’s disease, syphilis, Ormond’s disease, trauma, iatrogenic factors, pregnancy related |

| Thrumurthy et al., 2011, UK [194] | NR / - | female: 32% | back pain (no localisation or duration reported); neurological deficit | sharp, tearing, stabbing chest pain radiating to neck (type A) or interscapular region (type B), abrupt onset of ripping, tearing, stabbing pain in chest or abdomen, shock | diagnostic methods: CTA, echocardiography, MRA | risk factors: hypertension (40-75%), race (79% white), connective tissue diseases (Marfan syndrome: 15-50% in patients under 40 years), congenital cardiovascular abnormalities, aortic vasculitis disease, cocaine misuse, pregnancy, iatrogenic (5%) |

| Tsai et al., 2005, USA [195] | NR / - | incidence: 2.6-3.5 cases per 100.000 person-years | back pain (64% type B vs. 47% type A) (no duration or localisation reported) | cataclysmic onset, chest pain (blunt, severe, sometimes radiating); chest pain (79% type A vs. 63% type B), abdominal pain (43% type B vs. 22% type A) | diagnostic methods: ECG, chest x-ray, TTE, TEE, CT, MRI, aortography, coronary angiography | risk factors: smoking, dyslipidaemia, cocaine / crack, Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos-syndrome, bicuspid aortic valve, coarctation, giant cell arteritis, Takayasu arteritis, Behcet’s disease, syphilis, Ormond’s disease, trauma, iatrogenic factors |

| Vilacosta et al., 2001, Spain [196] | NR / - | - | acute back pain (no localisation reported) | severely intense, acute, tearing or tearing, throbbing and migratory chest pain = AAS, anterior chest, neck, throat and even jaw pain = ascending aorta; back and abdominal pain = descending aorta | diagnostic methods: laboratory tests (CK, troponin), ECG, chest x-ray, CT, MRI, TEE | risk factors: severe hypertension, disorders of elastic tissue |

| Vilacosta et al., 2009, Spain [197] | NR / - | - | acute back pain (no localisation reported) | severely intense, acute, tearing or ripping, pulsating and migratory chest pain = AAS; chest pain irradiating to the neck, throat or jaw indicates = ascending aorta; back or abdominal pain: descending aorta | diagnostic methods: laboratory tests, electrocardiography, chest x-ray, CT, MRI, TEE | risk factors: moderate to severe hypertension, disorders of elastic tissue; physical examination: murmur of aortic regurgitation, pulse differentials |

| Siegal et al., 2006, USA [198] | NR / - | incidence: 5-30 cases per 1 million people per year, 34% female, age: 65 y | back pain (or abdominal or chest pain) (95%) (no localisation or duration reported), severe or worst ever, sharp (64%), tearing, ripping; neurologic deficits | pulse deficits, hypotension, hypertension, end-organ ischaemia; other clinical findings: acute myocardial ischaemia / infarction, pericardial friction rub, syncope, pleural effusion or frank haemothorax, acute renal failure, mesenteric ischaemia | - | patients history: systemic hypertension (72%), atherosclerosis, h/o prior cardiac surgery, aortic aneurysm, collagen diseases, bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarctation, Turner syndrome, strenuous exercise, large vessel arteritis (giant cell, Takayasu's, syphilis), cocaine and methamphetamine ingestion, third-trimester pregnancy, blunt chest trauma or high-speed deceleration injury, iatrogenic injury; DDx: acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolus, pneumothorax, pneumonia, musculoskeletal pain, acute cholecystitis, oesophageal spasm or rupture, acute pancreatitis and acute pericarditis |

| Lech et al., 2017, USA [207] | NR / - | patients with AD: male predominance (40% female); patients with IMH typically older and more frequently in Asia than in America or Europe; patients with PAU: age >70 y | acute back pain (no localisation reported) | can be missed up to 40%; most common: sudden onset and severe pain located in the chest, abdomen, flank; painless, pain: tearing and ripping, radiating to the back; other specific symptoms: paresis, paraplegia, syncope; other signs: myocardial ischaemia, cardiac tamponade, cardiogenic shock, acute aortic regurgitation, mesenteric ischaemia; hypertension | diagnostic methods: physical examination (pulse deficit, aortic murmur; gastrointestinal bleeding, haematuria, anuria), CT / CTA, ultrasonography, MRI / MRA | causes / risk factors: hypertension (70%), h/o connective tissue disease, h/o atherosclerosis, cigarette use, illicit drug use, dyslipidaemia, h/o blunt trauma, recent aortic manipulation, family h/o aortic disease, inflammatory disorders (autoimmune and infectious), pregnancy |

| Corvera et al., 2016, USA [208] | NR / - | 1/3 female, average age of male: 63 y and female: 67 y | acute back pain (no localisation reported), tearing, ripping severe | acute onset of severe chest pain, tearing or ripping; other symptoms: syncope, neurological deficit including stroke and paraplegia, acute congestive heart failure, myocardial ischaemia, lower extremity ischaemia, abdominal pain and shock | diagnostic methods: physical examination (aortic murmur (44%), pulse deficit (20-30% in type A), hypertension (1/3 in type A); diagnostic: CTA, TTE, TEE, MRI, catheter angiography, no biomarkers | risk factors: hypertension, atherosclerosis, prior cardiac surgery, known aneurysm and Marfan syndrome |

| Winters et al., 2006, USA [9] | NR / - | male:female = 5:1, advanced age (50-70 years) | descending aorta: more commonly back pain (no duration or localisation reported) with radiation to hip and legs, neurological symptoms (quadriplegia, paraplegia, unilateral paraesthesia) | instantaneous onset of chest pain (maximal at onset, knifelike, ripping or tearing), syncope, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding, dysphagia, and hoarseness | diagnostic methods: physical examination: hypertension / hypotension, bilateral blood pressure difference; imaging: chest radiography, CT, MRI, TEE | risk factors: chronic hypertension, smoking, hyperlipidaemia, connective tissue syndromes (Marfan syndrome, Ehlers Danlos syndrome), chromosomal disorders (Turner’s syndrome, Noonan’s syndrome), bicuspid aortic valve, coarctation of the aorta, decelerating trauma, inflammatory conditions of the aorta, aortic instrumentation, pregnancy, cocaine use |

AAD acute aortic dissection, AAS acute aortic syndrome, AD aortic dissection, BP blood pressure, CHF congestive heart failure, CHS cohort study, CK creatine kinase, CR case report, CS case series, CT computed tomography, CTA computed tomography angiography, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ECG electrocardiogram, ED emergency department, GI gastrointestinal, h/o history of, IMH intramural haematoma, IRAD International Registry of Aortic Dissection, LBP low back pain, marf marfan-group, MRA magnetic resonance angiography, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, nmarf non-marfan group, NR narrative review, NRS numeric rating scale, PAU penetrating aortic ulcer, pf painful, pl painless, Sino-RAD Registry of Aortic Dissection in China, SR systematic review, TLOC transient loss of consciousness, TEE transoesophageal echocardiogram, TTE transthoracic echocardiogram, w with previous surgery, wo without previous surgery, y years

Fistula

A fistula is an uncommon connection between two structures, such as organs or vessels. A total of twelve case reports, five case series, seven cohort studies, a chart review, and nine narrative reviews describing different fistulas (e.g., aorto-enteric, aorto-caval, aorto-venous) presenting with LBP (Table 11) were found. Middle-aged and elderly men were most commonly affected. The aetiology varies greatly depending on the localisation, for example, aorto-enteric fistulas are often (up to 80% [213]) caused by AAAs. LBP is described as a frequently accompanying symptom of fistulas, ranging from 1.7% [214] to 93% [215] of affected patients. Accompanying symptoms depend on the structures affected and can include abdominal pain or vomiting [118, 120, 213, 216–219]. Neurological symptoms like paraplegia and sensory disorders can also occur, especially when it is an aorto-venous fistula affecting the spine. The diagnosis is made incidentally during imaging studies especially when patients present with marked symptoms. CT is often used initially [118, 120, 216, 217, 219–228], followed by other possible imaging methods such as duplex sonography, MRI, and digital subtraction angiography (DSA). In some cases, surgery was necessary for diagnosis [215, 221, 229].

Table 11.

Vascular fistulas presenting with back pain

| Author / year / country | Design / setting | Patient(s) | Diagnosis | Spinal symptoms | Extravertebral symptoms | Diagnostic confirmation | Other information / comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mehmood et al., 2007, Ireland [216] | CR / ED | male, 59 y | aorto-enteric fistula | acute LBP | vomiting, central abdominal pain, chronic fatigue | CT | - |

| Ogura et al., 2020, Japan [230] | CR / hospital | male, 73 y | aorto-venous fistula | chronic LBP, numbness in lower extremities, gait disturbance | - | angiography | - |

| Ozcakir et al., 2008, USA [213] | CR / ED | male, 60 y | aorto-enteric fistula | acute LBP, severe | abdominal pain, vomiting of blood | laparotomy | - |