Abstract

The Escherichia coli H-NS protein is a nucleoid-associated protein involved in gene regulation and DNA compaction. To get more insight into the mechanism of DNA compaction we applied atomic force microscopy (AFM) to study the structure of H-NS–DNA complexes. On circular DNA molecules two different levels of H-NS induced condensation were observed. H-NS induced lateral condensation of large regions of the plasmid. In addition, large globular structures were identified that incorporated a considerable amount of DNA. The formation of these globular structures appeared not to be dependent on any specific sequence. On the basis of the AFM images, a model for global condensation of the chromosomal DNA by H-NS is proposed.

INTRODUCTION

The Escherichia coli H-NS (H1) protein was originally isolated as a heat stable transcription factor (1). Later it was identified as one of the major components of the bacterial nucleoid (2), and it was therefore included (together with other small DNA-binding proteins like HU, IHF and Fis) into the family of nucleoid-associated proteins, sometimes referred to as histone-like proteins. Some of these nucleoid-associated proteins are more or less sequence specific, and are involved in processes such as transcription, recombination and replication (for reviews see 3,4). H-NS and HU, which are both very abundant, bind DNA without any obvious sequence specificity. Nevertheless, H-NS plays an important role as a pleiotropic transcription factor, influencing the expression of a wide variety of unrelated genes. Some examples include genes such as proU, hns, virF, fimB, rrnB, bgl and the genes involved in the early development of bacteriophage Mu (5–11).

Apart from its regulatory role, H-NS was proposed to be involved in the structural organisation of the E.coli chromosome. Overproduction of H-NS leads to highly condensed nucleoids and is lethal (12). The absence of H-NS in an hns deletion mutant results in an increased degree of negative supercoiling of both plasmid and chromosomal DNA (13). It is also evident from in vitro experiments that supercoiled plasmids are highly compacted by H-NS (14) and that H-NS constrains negative supercoils (15).

In this paper we will focus on the role of H-NS in DNA condensation. H-NS is a 15.6 kDa protein that has long been thought to exist predominantly as a dimer in solution (16), although the existence of higher oligomeric forms has also been reported (16,17). Recently it was shown that the predominant form of H-NS in solution is not dimeric, but instead tetrameric (18). This capacity to oligomerise has been shown to be important for the regulation of specific genes in vitro, and also seems to be important in the process of DNA condensation in vivo (17). The true nature of the complexes formed between H-NS and DNA, however, is unclear (15). We wish to gain insight into the structure of complexes in which DNA is compacted by H-NS. Here we apply atomic force microscopy (AFM) to observe directly structures formed upon H-NS binding to DNA. On the basis of the AFM images a mechanism is proposed through which this global DNA condensation is achieved.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA substrate for atomic force microscopy

Plasmid pUC19 was grown in E.coli strain XL10 and isolated by alkaline lysis and subsequent purification on Qiagen 100 columns according to the supplier’s instructions. Nicked DNA molecules were obtained from closed circular (supercoiled) DNA molecules (50 ng/µl) by digestion with DNase I (0.0625 U/µl) in the presence of ethidium bromide (360 ng/µl) in 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2 (total reaction volume of 60 µl) for 30 min at 30°C (19). The reaction was terminated by cooling on ice and addition of EDTA to a final concentration of 5 mM. Ethidium bromide and DNase I were removed by 3-fold extraction with 1.5 vol phenol, followed by 2-fold extraction with chloroform. Subsequently the buffer was replaced with HPLC water (Sigma) by dialysis overnight. Relaxation of the supercoiled plasmids was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Protein purification

The H-NS protein was purified from E.coli strain KA1746 containing the plasmid pHOP-11 (20). Cells were grown on LB in a 12 l fermenter. At an OD600 of 0.60, H-NS expression was induced by addition of IPTG. Two hours after induction cells were collected and resuspended in buffer A [20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.2), 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol], containing 100 mM NH4Cl and 1 mg/ml Pefabloc SC (Boehringer Mannheim). Cells were lysed by French-press at 10 000 p.s.i. and the lysate was cleared by centrifugation at 37 000 r.p.m. for 2.5 h at 4°C. The supernatant was directly loaded onto a P11-column pre-equilibrated with the same buffer. A linear NH4Cl gradient up to 1 M was applied and H-NS eluted around 800 mM NH4Cl. The buffer with NH4Cl was replaced with buffer A, containing 100 mM NaCl by dialysis overnight. Subsequently the dialysate was loaded onto a pre-equilibrated Heparin column. H-NS eluted around 550 mM NaCl. H-NS containing fractions were dialysed against a buffer solution containing 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.2), 300 mM KCl and 10% glycerol. All buffers contained 100 µg/ml PMSF (Sigma) and 2 mM benzamidine (Sigma) to prevent proteolytic cleavage of the H-NS protein (21). The purity of the H-NS protein was verified on an SDS–PAGE gel and the protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad).

Atomic force microscopy

Complexes of protein and pUC19 were formed by incubation of 85 ng of DNA with 450 or 900 ng of H-NS (H-NS:DNA = 1 dimer:12 bp or 1 dimer:6 bp), as indicated in the text, in 10 µl H-NS BB [40 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mM MgCl2, 60 mM KCl] for 30 min at 37°C. This incubation mixture was then diluted 20 times [to a final concentration of 5 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 5.5 mM MgCl2, 3 mM KCl] and deposited onto freshly cleaved mica (Ted Pella Inc., Redding, CA). DNA without H-NS was deposited under the same buffer conditions. After ~20 s the mica disc was gently rinsed with HPLC water (Sigma). Excess water was removed with highly absorbent tissue paper, and subsequently the disc was dried under a steady stream of filtered air. The deposition frequency thus obtained was about 1 molecule/complex per µm2.

Images were acquired on a Nanoscope IIIa (Digital Instruments Inc., Santa Barbara, CA), operating in tapping mode in air with a type E scanner. Silicon tips (Nanoprobes) were obtained from Digital Instruments Inc. DNA lengths were measured from Nanoscope images imported into Image SXM 1.62 (an NIH Image version modified for use with SPM images by Dr Steve Barrett, Surface Science Research Centre, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK). DNA contours were manually traced. Where DNA was within a complex the shortest continuous path through the complex was assumed. The level of condensation was calculated as a condensation factor defined as the quotient of the contour length (CL) of naked DNA (average of the measured values) and the apparent contour length of the DNA in the protein–DNA complex: CLnaked DNA : CLcomplex. Analogously, but taking into consideration only the DNA apparently involved in complex formation, a local condensation factor was defined as (CLnaked DNA – CLnaked DNA within complex) / (CLcomplex – CLnaked DNA within complex). Note that the limiting ratio, when no condensation is occurring, approaches unity. As a consequence, the local condensation factor of uncondensed molecules is 1. Analysis of heights within protein–DNA complexes was done with the ‘Analyse Section’ function in the Nanoscope software. Two-dimensional images in Nanoscope format were imported into Image SXM 1.62 and brightness and contrast were optimised for the purpose of clarity. Three-dimensional images were created with the Nanoscope software and exported in TIFF format.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

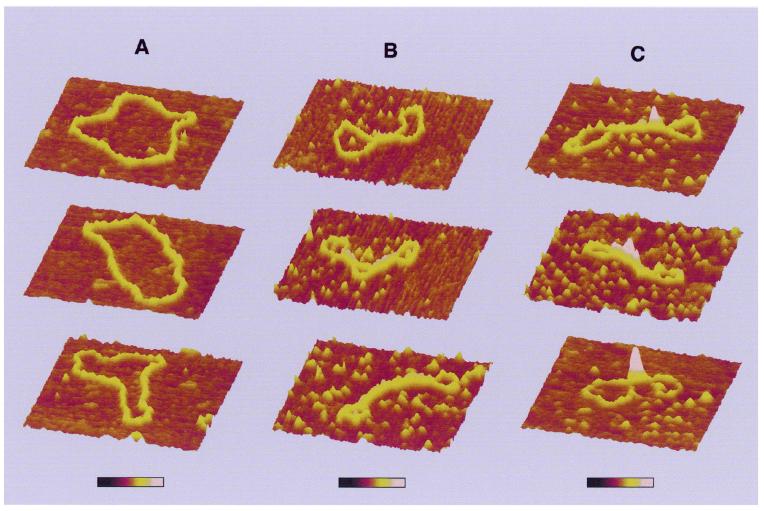

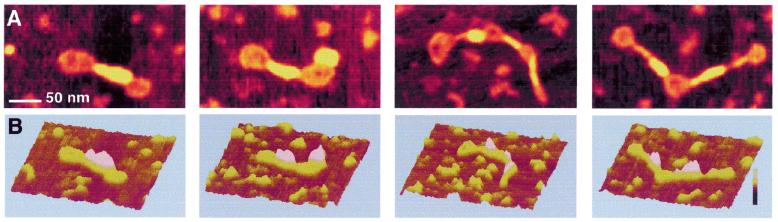

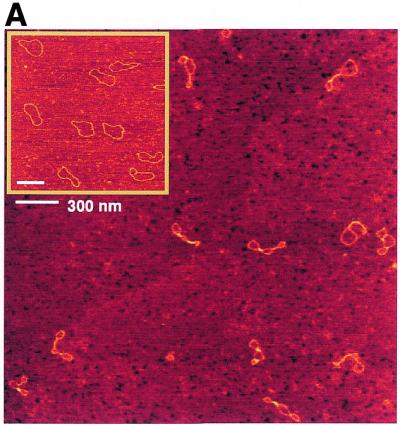

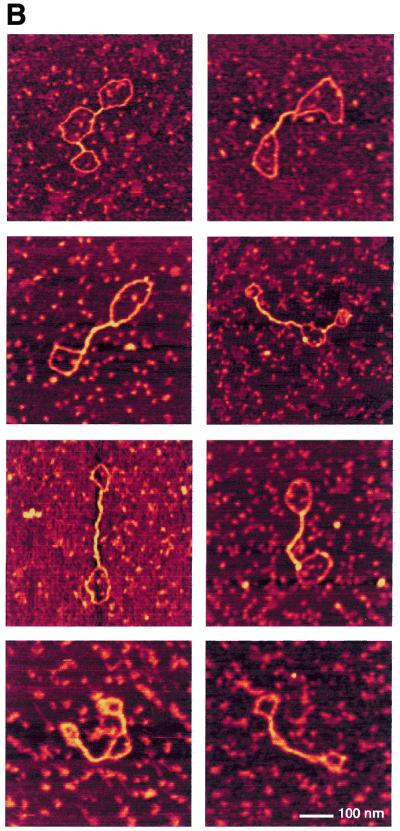

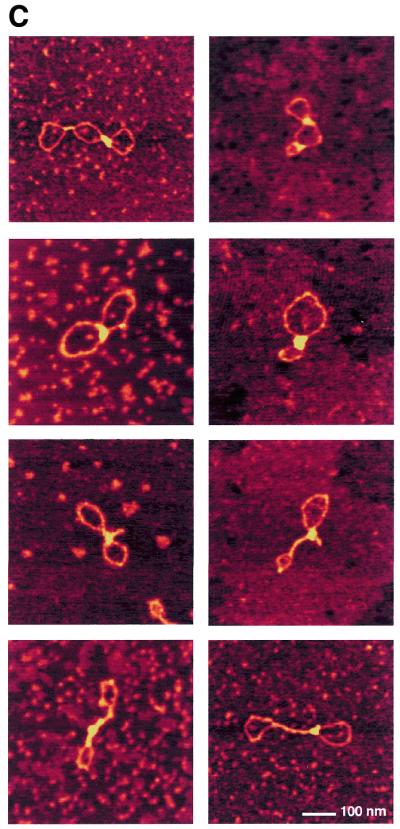

In order to obtain insight into the structural effects of H-NS binding to DNA, we have applied AFM. AFM analysis provides some distinct advantages over bulk biochemical assays, particularly when studying proteins that do not interact with specific DNA sequences or structures. Individual DNA–protein complexes are observed that can be qualitatively categorised and measured. Thus the distribution of complexes with specific features in a mixture is determined rather than a bulk average usually determined in biochemical assays. The effects of H-NS binding were studied on relaxed circular molecules, which were obtained by the introduction of a limited number of nicks in plasmid pUC19 (Materials and Methods). A ratio of 1 dimer of H-NS per 12 bp was used. These conditions correspond to the formation of 100% retarded complex on an agarose gel (not shown). In the absence of H-NS, the DNA molecules have an open appearance (Fig. 1A) and a uniform height (Fig. 2A) all along their contours. Less than 5% of the molecules are observed as not entirely open and show short lateral tracts in which the DNA duplexes have contacts. Presumably these are random overlaps of the DNA that occur during deposition onto mica. In the presence of H-NS, structural changes covering a long part of the DNA molecule were found (Fig. 1A). On the basis of the appearance of the complexes they could be divided into two classes. Complexes in the first class of molecules, depicted in Figures 1B and 2B, show large tracts with two regions of double-stranded DNA held close together. The remaining open loops are mostly found at the ‘ends’ of the plasmids. The second class of molecules, depicted in Figures 1C and 2C, is characterised by the presence of relatively high foci. These foci are 2.5–4 times higher than naked DNA. The remaining part of the molecule is apparently naked DNA, similar to that observed in the first class of molecules, or contains some lateral tracts. These lateral tracts and the tracts observed in the first class of molecules are not as high as the foci (only 1.5 ± 0.4 times the height of naked DNA). Very rarely (2% of the molecules observed) no obvious effect of H-NS on DNA structure is visible. However, it cannot be excluded that also here single H-NS molecules or dimers are bound to the DNA, but cannot be distinguished due to their small size. Similar results were obtained with plasmids of larger size or different base composition (not shown), illustrating the non-specific nature of this protein in binding to DNA and showing that the formation of foci is not dependent on any specific sequence.

Figure 1.

AFM images of circular nicked pUC19 molecules with and without H-NS. (A) DNA molecules after incubation with H-NS (1 dimer per 12 bp) on a 2.5 × 2.5 µm surface area and DNA molecules without H-NS on a 2 × 2 µm surface area (inset). (B) Close-up images of class I complexes. Complexes are laterally condensed and show a small reduction of DNA contour length (~3%). (C) Close-up images of class II complexes. Complexes show characteristic foci with a more dramatic level of condensation and a large reduction of DNA contour length (up to ~25%). All close-up images of condensed molecules show a 500 × 500 nm surface area. The colour scale ranges from 0.0 to 3.0 nm (from dark to bright).

Figure 2.

Three-dimensional representation of circular nicked pUC19 molecules with and without H-NS. (A) DNA molecules without H-NS. (B) Class I complexes. (C) Higher order condensed class II complexes. Each series of images corresponds to characteristic structures found in that class. All images show a 400 × 400 nm surface area. The colour bar indicates sample height and corresponds to a 0.0–3.0 nm range (from dark to bright).

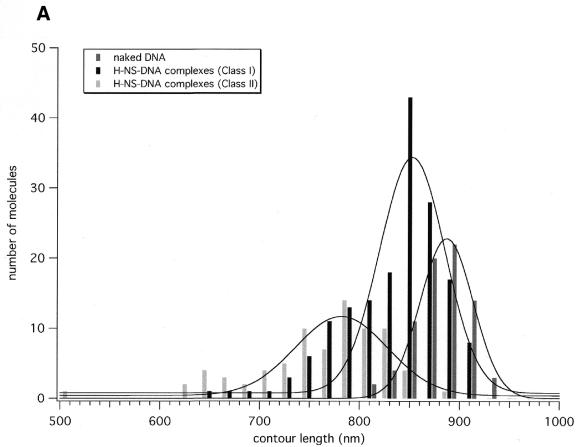

The apparent contour length of the complexes was measured and plotted as a histogram in Figure 3. The average value of the contour length as determined for naked DNA molecules was 873 ± 26 nm. This value is close to what is expected for B-form DNA (900 nm) and consistent with previous results (22). The average contour length of the DNA in the class I complexes has been reduced (~3%) with respect to the molecules without obvious bound protein. It is, however, not clear how H-NS mediates the interaction between the adjacent DNA duplexes. A specific oligomeric state is not evident from these experiments, as separate oligomeric structures cannot be identified on the DNA. The two DNA helices are possibly held together through the binding of one monomeric/dimeric subunit of an H-NS dimer/tetramer to each DNA duplex. The moderate level of condensation observed in these complexes could correspond to interwinding of the two DNA helices. This would be consistent with the observation that H-NS binding to DNA results in the constraining of supercoiling (15). In class II complexes the DNA is condensed much more dramatically, resulting in a strong reduction of DNA contour length (up to ~25%: see Fig. 3). The height of these foci together with the loss of a considerable amount of DNA indicates that each focus represents a region of highly compacted DNA, probably mediated by extensive oligomerisation of bound H-NS molecules. It should be noted that, although the protein–DNA complexes in this class all possess the characteristic foci and show a high level of compaction, they are not very homogenous in their overall structure.

Figure 3.

Histograms of measurements performed on H-NS–DNA complexes. (A) Apparent contour length of naked DNA molecules (n = 76) and H-NS–DNA complexes (n = 166 for class I complexes and n = 80 for class II complexes). (B) Global and local condensation factors as determined for H-NS–DNA complexes.

The effects of the two different kinds of compaction (formation of lateral tracts and foci) can be better evaluated when a condensation factor (Materials and Methods) is calculated for each of the complexes (Fig. 3). The global condensation factor indicates the apparent decrease in contour length as resulting from an average of the contributions of both kinds of condensation. One can, however, more specifically determine the direct effects of H-NS binding by calculating a local condensation factor (Materials and Methods) with the assumption that the ‘naked’ DNA is not affected by eventual bound H-NS molecules. In many cases the level of local condensation for class II complexes is likely to be still underestimated as the contributions of the different types of condensation cannot be separated when both types are found within the same complex (see Fig. 2C, top image). Nevertheless, this operation results in a more distinct separation of the condensation factors for the two classes. Local condensation factors of the class I complexes, with lateral condensation alone, are predominantly found at values close to their corresponding global condensation factor, while in the case of class II complexes they are found very broadly distributed around higher values. The highest values are obtained for complexes where condensation only occurs in foci, meaning that within these foci very strong condensation is taking place.

Interestingly, no condensation of the DNA molecules was observed when protein–DNA mixtures were incubated at the same molecular ratio, but under 20-fold more dilute conditions (not shown). This could reflect an effect of the oligomeric state of H-NS in solution on complex formation. Recent data suggest that under these more dilute conditions the H-NS in solution changes from a tetrameric to a monomeric form (18).

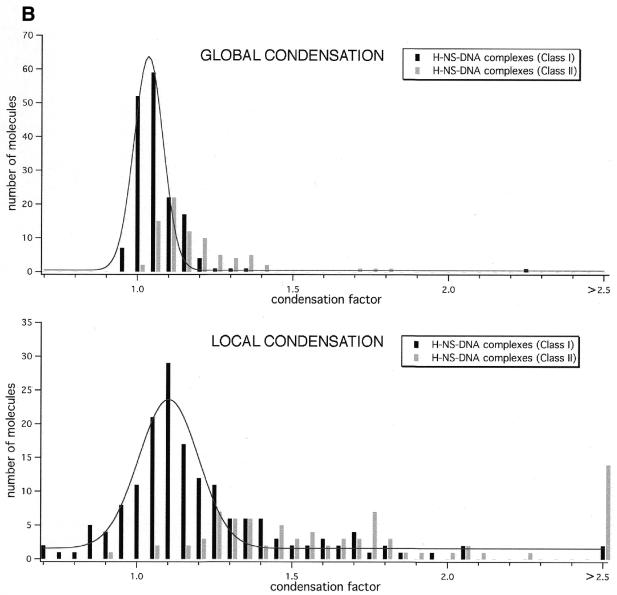

Upon incubation of the DNA at a higher ratio of H-NS:DNA (1 dimer:6 bp), more dramatically condensed structures are observed. These complexes have an almost rod-like appearance (Fig. 4A and B), which is reminiscent of the class I complexes with laterally condensed tracts, as discussed above. Contour length analysis and height measurement of the complexes, however, reveal a higher level of compaction. The apparent contour length can be as short as 400 nm, which corresponds to >50% condensation. These higher order structures may not be very stable, as slight, uncontrollable, variations in the preparation procedure result in their disruption. Then complexes are observed which are quantitatively and qualitatively similar to the complexes observed at the lower H-NS:DNA ratio described above.

Figure 4.

AFM images of circular nicked pUC19 molecules after incubation with H-NS (1 dimer per 6 bp). (A) Two-dimensional representation. Images show a 300 × 175 nm surface area. (B) Three-dimensional representation. Images show a 300 × 300 nm surface area. The colour bar indicates sample height and corresponds to a 0.0–3.0 nm range (from dark to bright).

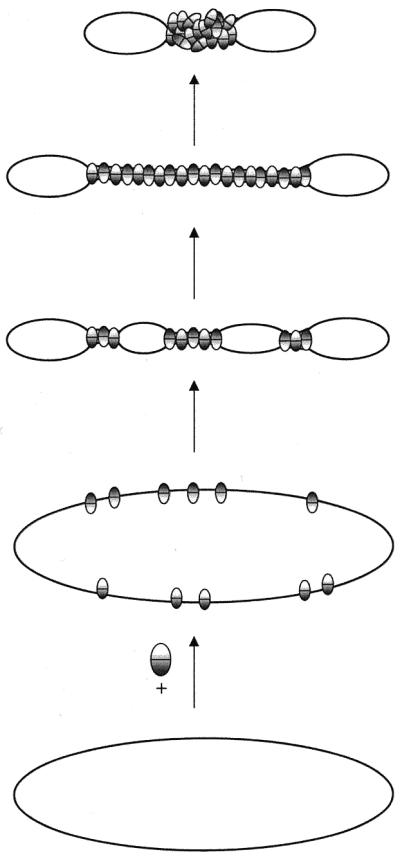

From the different levels of condensation observed by AFM a model for H-NS mediated compaction of the DNA can be proposed. H-NS protein is likely to initially bind randomly to the DNA without inducing significant linear condensation. When two DNA strands are close enough, the bound protein interacts with an additional DNA strand or another H-NS molecule bound to that strand forming an intramolecular bridge. A possible interwinding of the DNA helices would account for a first level of condensation. Subsequently, formation of highly compacted DNA in foci could result from further oligomerisation between the H-NS molecules bound in the lateral tracts, leading to a second level of condensation (Fig. 4). A further oligomerisation of H-NS between different loci on different DNA molecules could finally lead to an abnormally high condensation of the DNA through network formation. In vivo highly condensed nucleoids are observed upon overexpression of H-NS (12). Possibly the identified oligomerisation domain of H-NS (23) is especially important for the formation of these higher order structures (17).

It is not clear from the AFM images whether the complexes with tracts of lateral condensation have H-NS bound all along, as individual H-NS molecules cannot be identified. Significant differences in height within these tracts are not observed by AFM (Fig. 2B). Possibly, at this stage, the tracts are not completely covered with H-NS, but the two DNA duplexes might be aligned by a limited number of randomly positioned bridges. The positions on the ‘free’ DNA in between these bridges might not be resolved as such. On some complexes, however, it is very obvious that free DNA is remaining, as alternating tracts of lateral condensation and free DNA ‘bubbles’ are observed (see Fig. 1B). On the other hand, the binding process could be very cooperative as upon formation of the first bridges, neighbouring tracts on the DNA helices are brought closer together, which is likely to favour the formation of more bridges. At saturation the complexes are likely to have a structure similar to the final structure shown in the model of Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Model for DNA condensation induced by H-NS. When two DNA strands come close enough, the bound protein interacts with an additional DNA strand or protein bound to that strand forming an intramolecular bridge. The formation of the first bridges leads to an increased chance of further DNA bridging in the intervening free ‘bubbles’. Subsequently, further oligomerisation between the H-NS molecules bound in the lateral tracts leads to a second level of condensation. Split ovals represent an H-NS dimer or tetramer exposing at least two DNA binding domains.

Strikingly, open end-loops are reproducibly found to be present on H-NS–DNA complexes. It cannot be excluded that the affinity for the deposition surface for complexes with ‘free’ DNA loops is higher than for completely ‘covered’ DNA molecules, but on the other hand this might reflect a topological restraint imposed on these loops by the binding of the protein. This could occur if the limited number of nicks that was introduced into the plasmid DNA [close to one nick per molecule (19)] is held within the complex, in such a way that the topological changes resulting from H-NS binding cannot dissipate throughout the molecule.

A similar mechanism for DNA compaction through DNA-bridging has been put forward for a number of other proteins. Examples include the compaction of the Moloney murine leukemia virus DNA genome by dimeric BAF (24), and Bacillus subtilis chromatin by tetrameric LrpC (25). The eukaryotic linker histones H1 and H5 were shown to form complexes of similar appearance with tracts of lateral condensation, which are presumably due to the presence of two separate DNA binding domains, and it was proposed that these complexes contain two intertwined DNA helices (26). The proposed mechanisms leading to DNA condensation by these proteins, including H-NS, are clearly distinct from other nucleoid-associated proteins, such as HU (27), from φ29 p6 (28), archaebacterial HMf (29,30) and eukaryotic architectural proteins, such as HMG (31) and SMC (32). These have been proposed to function through a wrapping mechanism, forming solenoidal supercoils, resembling the organisation of eukaryotic DNA into nucleosomes. The model as proposed here might also explain the observed preferential binding of H-NS to highly curved DNA sequences (33), and the importance of the oligomerisation domain in this process (17). It can be envisaged that in such a case bridging by H-NS becomes stimulated as a consequence of the curve increasing the probability that the DNA in the two flanking regions is brought in close proximity.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Dr Rob Visse is kindly acknowledged for fruitful discussion and thorough reading of early versions of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jacquet M., Cukier-Kahn,R., Pla,J. and Gros,F. (1971) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 45, 1597–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varshavsky A.J., Nedospasov,S.A., Bakayev,V.V., Bakayeva,T.G. and Georgiev,G.P. (1977) Nucleic Acids Res., 4, 2725–2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goosen N. and van de Putte,P. (1995) Mol. Microbiol., 16, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkel S.E. and Johnson,R.C. (1992) Mol. Microbiol., 6, 3257–3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucht J.M., Dersch,P., Kempf,B. and Bremer,E. (1994) J. Biol. Chem., 269, 6578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falconi M., Higgins,N.P., Spurio,R., Pon,C.L. and Gualerzi,C.O. (1993) Mol. Microbiol., 10, 273–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falconi M., Colonna,B., Prosseda,G., Micheli,G. and Gualerzi,C.O. (1998) EMBO J., 17, 7033–7043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donato G.M., Lelivelt,M.J. and Kawula,T.H. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 6618–6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tippner D., Afflerbach,H., Bradaczek,C. and Wagner,R. (1994) Mol. Microbiol., 11, 589–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Defez R. and De Felice,M. (1981) Genetics, 97, 11–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Ulsen P., Hillebrand,M., Zulianello,L., van de Putte,P. and Goosen,N. (1996) Mol. Microbiol., 21, 567–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spurio R., Durrenberger,M., Falconi,M., La Teana,A., Pon,C.L. and Gualerzi,C.O. (1992) Mol. Gen. Genet., 231, 201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mojica F.J. and Higgins,C.F. (1997) J. Bacteriol., 179, 3528–3533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spassky A., Rimsky,S., Garreau,H. and Buc,H. (1984) Nucleic Acids Res., 12, 5321–5340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tupper A.E., Owen-Hughes,T.A., Ussery,D.W., Santos,D.S., Ferguson,D.J., Sidebotham,J.M., Hinton,J.C. and Higgins,C.F. (1994) EMBO J., 13, 258–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falconi M., Gualtieri,M.T., La Teana,A., Losso,M.A. and Pon,C.L. (1988) Mol. Microbiol., 2, 323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spurio R., Falconi,M., Brandi,A., Pon,C.L. and Gualerzi,C.O. (1997) EMBO J., 16, 1795–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ceschini S., Lupidi,G., Coletta,M., Pon,C.L., Fioretti,E. and Angeletti,M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem., 275, 729–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenfield L., Simpson,L. and Kaplan,D. (1975) Biochem. Biophys. Acta, 407, 365–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka K., Yamada,H., Yoshida,T. and Mizuno,T. (1991) Agric. Biol. Chem., 55, 3139–3141. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg M.D., Canvin,J.R., Freestone,P., Andersen,C., Laoudj,D., Williams,P.H., Holland,I.B. and Norris,V. (1997) Biochimie, 79, 315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muzzalupo I., Nigro,C., Zuccheri,G., Samori,B., Quagliariello,C. and Buttinelli,M. (1995) J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A, 13, 1752–1754. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueguchi C., Suzuki,T., Yoshida,T., Tanaka,K. and Mizuno,T. (1996) J. Mol. Biol., 263, 149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee M.S. and Craigie,R. (1998) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 1528–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tapias A., López,G. and Ayora,S. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 552–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark D.J. and Thomas,J.O. (1988) Eur. J. Biochem., 178, 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka H., Yasuzawa,K., Kohno,K., Goshima,N., Kano,Y., Saiki,T. and Imamoto,F. (1995) Mol. Gen. Genet., 248, 518–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serrano M., Gutierrez,C., Salas,M. and Hermoso,J.M. (1993) J. Mol. Biol., 230, 248–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandman K., Krzycki,J.A., Dobrinski,B., Lurz,R. and Reeve,J.N. (1990) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 5788–5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musgrave D.R., Sandman,K.M. and Reeve,J.N. (1991) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 88, 10397–10401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bianchi M.E. and Beltrame,M. (1998) Am. J. Hum. Genet., 63, 1573–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmes V.F. and Cozzarelli,N.R. (2000) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 1322–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jordi B.J., Fielder,A.E., Burns,C.M., Hinton,J.C., Dover,N., Ussery,D.W. and Higgins,C.F. (1997) J. Biol. Chem., 272, 12083–12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]