Abstract

Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA) is an ultra-rare neurodegenerative disorder characterized by ataxia, cognitive decline, myoclonus, chorea, epilepsy, and psychiatric manifestations. This article delves into the multifaceted efforts of CureDRPLA, a family-driven non-profit organization, in advancing research, raising awareness, and developing therapeutic strategies for this complex condition. CureDRPLA’s inception in 2019 led to the establishment of the DRPLA Research Program, and since then have funded research projects to advance the understanding of DRPLA including but not limited to human cellular and mouse models, a natural history and biomarkers study, and a patient registry. There are currently no disease-modifying treatments for DRPLA, motivating a concerted effort on behalf of CureDRPLA to hasten their development by funding and coordinating preclinical studies of therapies in multiple modalities. Of particular interest are therapies focused on lowering the expression (or downregulation) of ATN1, the mutant gene that causes DRPLA, in hopes of tackling the pathology at its root. As with many ultra-rare diseases, a key challenge in DRPLA remains the complexity of coordinating both basic and clinical research efforts across multiple sites around the world. Finally, despite the generous financial support provided by CureDRPLA, more funding and collective efforts are still required to advance research toward the clinic and develop effective treatments for individuals with DRPLA.

Keywords: DRPLA, drug development, patient advocacy group, polyQ repeat disorders, rare diseases, research

Plain language summary

Funding research projects and activities to advance research towards treatments for dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA)

This article describes the journey of CureDRPLA, a family-driven non-profit organization dedicated to making strides against dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA), an ultra-rare brain disorder. It describes CureDRPLA’s tireless efforts to understand, treat, and raise awareness about DRPLA, a condition marked by movement difficulties (ataxia), intellectual disability, uncontrollable jerky movements (myoclonus), involuntary or irregular muscle movements (chorea) and seizures. This disorder is caused by a mutation in a gene called ATN1. The gene produces a protein called atrophin-1, and when the DRPLA-causing mutation is present, the protein becomes abnormal and can build up in the brain, affecting its normal functions. Since its founding in 2019, CureDRPLA has funded research projects to unravel the mysteries of the disease and provide support for affected individuals. CureDRPLA has funded projects to create models of DRPLA using human cells and mice, which helps scientists study the disease and test potential treatments. We have started a study to learn more about how DRPLA progresses in people and are building a global database of information from individuals with DRPLA. Due to the absence of a treatment or cure, CureDRPLA is focused on testing treatments. We are particularly interested in exploring different approaches to lower the levels of the abnormal protein in the brain. CureDRPLA is actively involving the DRPLA community worldwide, raising awareness through events, conferences, and social media. We aim to connect with medical professionals, researchers, and affected families to build a strong community focused on understanding and managing DRPLA. In summary, CureDRPLA is working hard to better understand DRPLA, support affected families, and accelerate the development of treatments for this challenging condition. Our collaborative efforts and dedication underscore the importance of a united global approach to address the complexities of DRPLA.

Introduction

Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA, MIM#125370) is an ultra-rare neurodegenerative disorder characterized by six cardinal features: ataxia, cognitive decline, myoclonus, chorea, epilepsy, and psychiatric manifestations.1,2 DRPLA is inherited in a dominant autosomal manner; the Atrophin-1 gene (ATN1) is the only gene known to cause DRPLA and is located on chromosome 12p13.31. 3 DRPLA is caused by a CAG repeat expansion of more than ⩾48 tandem copies in exon 5 of ATN1, resulting in an expanded polyglutamine (polyQ) tract in the atrophin-1 protein. 3 DRPLA is one of the nine polyQ disorders known to date that result from the expansion of a CAG repeat. This condition is more common in Asia, particularly Japanese populations where DRPLA has been estimated to have an incidence ranging from 2 to 7 per million individuals. 4

The function of the gene product, atrophin-1, is imperfectly understood, though it is thought to act as a transcriptional co-repressor. 5 However, the abnormally long CAG repeat expansion changes the structure of atrophin-1, rendering it capable of aggregation. This altered protein accumulates in neurons, ultimately interfering with normal cell functions. 6 Whilst the exact pathophysiology of DRPLA is not fully understood, the literature points toward a toxic gain-of-function of the mutant protein and neuronal cells are particularly susceptible to polyQ-mediated toxicity compared to other cell types. 3

Among the CAG repeat diseases, DRPLA exhibits the most prominent instability in the number of CAG repeats, both somatically and meiotically; the length of the CAG tract expands significantly through subsequent generations, a phenomenon known as genetic anticipation.7,8 In common with many other CAG expansion disorders, the onset of DRPLA is closely associated with ATN1’s CAG repeat length. Juvenile-onset DRPLA (by definition, with an age at onset of <20 years) is characterized by myoclonus, epilepsy, developmental delay, and progressive intellectual disability.3,7 Brief generalized seizures were observed in juvenile-onset patients at the early stages of the disease and generalized tonic-clonic seizures were more common at an advanced state, suggesting that seizure types might change during the course of the disease. 9 Adult-onset DRPLA (age at onset of >20 years) is characterized by ataxia, choreoathetosis, cognitive impairment, and personality changes.2,3

The autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of DRPLA means that usually, there are multiple family members affected with DRPLA. Thanks to the pronounced anticipation observed, is very common for a parent and one or multiple children to be affected at the same time and therefore, the unaffected members have a lot of responsibilities as caregivers. This anticipation adds another layer of difficulty, as symptom onset can appear earlier and in fact, the age at onset is reduced by approximately 19 years with each generation. 10 Disease heterogeneity and different progression rates4,11,12 imply that each patient has very different needs – thereby proving that in addition to the effects on patients suffering from DRPLA, family members and caregivers experience emotional and physical burden of their own.

CureDRPLA, a non-profit organization founded in November 2019, emerged from a deeply personal journey – the co-founders’ son was diagnosed with DRPLA in 2018. His diagnosis prompted them to create a patient advocacy group (PAG) dedicated exclusively to DRPLA.

Mission statement

The mission of CureDRPLA is to connect families, physicians, and scientific investigators to further DRPLA research and work toward a treatment for DRPLA. Our primary motivation is time, and therefore we are working strategically with both academic and commercial partners to advance DRPLA treatments to the clinic as quickly as possible.

Partnering with another PAG to build the research program

After considering other models, CureDRPLA’s founders decided that the most rapid and effective model would be a hybrid in which an established PAG supports some of CureDRPLA’s activities. CureDRPLA engaged with Ataxia UK to help further its efforts and benefit from their expertise and connections in the ataxia field. Ataxia UK is a charity working to improve the treatment and care of people affected by ataxia since 1963 and funds research to help find treatments and cures.

Here, we outline our projects and milestones achieved since CureDRPLA’s inception.

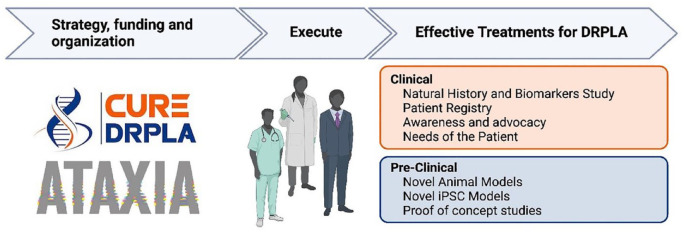

Resources created to advance DRPLA research

To translate our mission into tangible outcomes, we established the DRPLA Research Program with the aim to advance multiple research areas in parallel to move as quickly as possible toward our goal, hastening effective treatments for DRPLA (Figure 1). To date, over 50 scientists have contributed to DRPLA research funded by CureDRPLA.

Figure 1.

Overview of the efforts led by CureDRPLA to advance research toward treatments. CureDRPLA, in partnership with Ataxia UK, plays a pivotal role in propelling research efforts for DRPLA. The organization allocates funds to both academic institutions and commercial partners, supporting the development of essential tools for research, such as cell and animal models. This funding facilitates a deeper understanding of the function of the ATN1 gene and the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms in DRPLA. These collaborative projects contribute significantly to the progress of drug discovery, preclinical studies, and clinical research. To prepare for future clinical trials, CureDRPLA actively manages a patient registry and funds a natural history and biomarkers study. By doing so, the organization aims to gather crucial information that will inform future trial designs. Furthermore, the organization has dedicated some funds to document the lived experiences of individuals affected by DRPLA and their caregivers, as well as elevating awareness about DRPLA, advocating for improved care, and advancing therapies toward clinical application. Image created with BioRender.com.

DRPLA, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy.

CureDRPLA has funded multiple research projects across the world. The goal of these efforts is to develop the tools needed to better define DRPLA within the broader context of health, encompassing both its medical and societal dimensions, as well as developing a deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of DRPLA (Table 1). Other than advancing research, these resources aim to de-risk the drug development process and make it more tempting for commercial companies to develop treatments for DRPLA.

Table 1.

Resources and data elements available for the scientific community generated with funding from CureDRPLA.

| Category | Resources and data elements available |

|---|---|

| Human cellular models | DRPLA patient iPSCs (heterozygous for a 67 CAG repeat expansion) |

| ATN1 CRISPR/Cas9 knockout series: ATN1 wild-type, 50% knockout, and 100% knockout | |

| Fibroblast cultures from 16 DRPLA patients. Some were reprogrammed to iPSCs and differentiated into neurons | |

| Mouse models | A fully humanized mouse model of DRPLA expressing human ATN1 from the mouse Atn1 locus. Two lines have been generated expressing 112 and 70 pure CAG repeats |

| DRPLA natural history and biomarkers study | Clinical scales and questionnaires that include but not limited to ataxia, choreoathetosis, dementia, cognitive impairment, seizures, myoclonus |

| Volumetric brain MRI | |

| Biosamples: blood, saliva, urine, feces, skin biopsy, and cerebrospinal fluid | |

| CureDRPLA Global Patient Registry | Demographics Contact information Diagnosis information Family history of DRPLA Symptoms of DRPLA Management of DRPLA symptoms Epilepsy seizures Participation in future research studies Functional mobility Use of assistive devices Functional ability for activities of daily living Education Employment Marital status and children Living arrangement Assistive care Hospitalizations |

| Collection of lived experiences | The Voice of the Patient: living with polyQ spinocerebellar ataxias and DRPLA |

| Qualitative interviews on the most bothersome symptoms, impact on daily life, treatment goals, and clinical trial participation preferences |

DRPLA, dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy; iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell.

Human cellular models

In order to advance the understanding on ATN1 function and pathophysiology, as well as testing of potential therapies for DRPLA, we have funded projects to developed human cellular models. At least 16 patients with different CAG repeat expansions have consented to a skin biopsy for the collection of fibroblasts. Fibroblasts have been reprogrammed and engineered in various ways to produce induced pluripotent stem cells, differentiated neurons, and knockout lines (Table 1).

Humanized ATN1 mouse models

In hopes of hastening preclinical testing of potential therapies for DRPLA, we used genome editing techniques in mouse embryonic stem cells to develop a fully humanized set of mouse lines congenic on the C57Bl/6N strain. These mice express a human transcript of ATN1, inclusive of non-coding (5′ UTR to 3′ UTR) and coding sequences at the mouse Atn1 locus, which the human gene replaces. This ensures that sequence-specific therapies of interest, such as antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), have their target sequence in a mouse model, even if those targets are in the UTRs or introns, that the gene is expressed under the appropriate regulatory elements, and that levels of ATN1 are physiological.

To date, we have generated two lines of mice with long, pure CAG repeat expansions (70 and 112) inserted (Table 1). We are currently characterizing the emergent DRPLA-like signs in these mice but are making them accessible to other researchers and drug development organizations immediately. The 112Q line has very pronounced phenotypes, including emergent seizures, behavioral changes, and many molecular alterations that we are currently characterizing (Carroll lab, unpublished data). We will submit an initial paper describing the Q112 mice in 2024, as well as depositing them at academic repositories such as Jackson Laboratories. To date, we have not characterized the Q70 line, which has only recently been received and is successfully breeding at the Carroll Lab, University of Washington. Our goal with the shorter length CAG repeat is to have a model system to study more protracted aspects of DRPLA pathology beyond the constrained lifespan of the Q112 line.

DRPLA Natural History and Biomarkers Study

An ongoing natural history study is currently recruiting pediatric and adult DRPLA mutation carriers and healthy controls across different countries to characterize the progression of DRPLA in both juvenile- and adult-onset patients. Using a variety of clinical and biomarker modalities, it aims to identify biomarkers, and clinical measures predictive of disease progression. The results of this study will contribute to instruct future trial design.

The DRPLA Natural History and Biomarkers Study (NHBS) is a prospective multicenter study with sites in North America and the United Kingdom currently running. The United Kingdom investigators are establishing collaborations with neurologists in other countries to boost recruitment numbers. An effort to open sites in Japan, the country with the greatest known prevalence of DRPLA, is underway. Participants will undergo three study visits, each scheduled 1 year apart. The protocol includes scales and questionnaires that are crucial to capture the progression of the disease in its multi-systemic aspects and participants will also be offered the optional opportunity to collect biomaterials and brain MRI (Table 1).

CureDRPLA Global Patient Registry

This online registry is establishing a longitudinal database of patient-reported data on individuals affected with DRPLA [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05489393]. Over time this registry will enhance our understanding of DRPLA prevalence across the world and create a cohort of well-characterized patients for participation in research projects and clinical trials. It also collects information on diagnostic journeys, burden of illness and patient reported outcomes. Individuals with DRPLA or their caregivers can participate in this registry and all participants are asked to update their information once a year (Table 1). The registry is available in English, French, Italian, Japanese, Korean, and Portuguese. Currently, there are 49 participants from 10 different countries in the registry.

The Voice of the Patient: living with polyQ spinocerebellar ataxias and DRPLA

CureDRPLA and the National Ataxia Foundation (NAF) co-hosted an Externally-Led Patient-Focused Drug Development (EL-PFDD) on 25 September 2020. EL-PFDD meetings are organized by PAGs and aim to obtain the patient perspective on specific diseases and their treatments. The input from such meetings can inform the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) decision during their review of a marketing application. The meeting organized by CureDRPLA and NAF, enabled spinocerebellar ataxias (SCA) and DRPLA-affected individuals to share their perspectives on the impact of these diseases in other to provide the FDA and other key stakeholders a meaningful understanding of the patient experience. It also gathered information regarding potential therapeutic treatment goals. In total, seven people described their experience of living with DRPLA or caring for someone with this condition, and the recording of the event and the report are available on our website (Table 1). 13

Qualitative interviews for the assessment of symptom burdens

CureDRPLA worked with a contract research organization, Casimir (Emmes), to conduct a qualitative interview study amongst DRPLA patients and caregivers (Table 1). The goal of this study was to understand their most bothersome symptoms, and the impact of these symptoms on daily life. It also aimed to explore patient and caregiver treatment goals and clinical trial participation differences. These interviews described the experiences of 7 adult-onset patients and 11 juvenile-onset patients (manuscript accepted for publication).

Raising awareness of DRPLA and CureDRPLA

In parallel to this basic and clinical research, CureDRPLA has undertaken extensive initiatives to raise awareness of DRPLA and our organization’s programs. Ultimately, we want to find as many DRPLA patients as possible and connect with the medical professionals that provide care to these patients to create a global DRPLA community. We started with targeted outreach, sending more than 3,000 cold emails to authors that published on DRPLA or other conditions of interest, PAGs, professional bodies, and medical professionals. The global reach is evident, this resulted in connections with more than 320 medical professionals and the identification of DRPLA patients in 30 countries. To continue building this network and keeping up to date with advances in ataxia research, we have joined initiatives like the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society, the Rare Epilepsy Network, and the Ataxia Global Initiative.

Members of our organization and some of our funded researchers have attended international conferences and presented posters with their latest findings. Having a presence at conferences has been rewarding, we connected with those very familiar with our initiatives but more importantly, we forged new connections amongst researchers interested in DRPLA. In 2022, we held our first CureDRPLA Research Conference in Boston, and we recently had our second conference in October 2023 with 26 attendees in-person. CureDRPLA hosted these conferences and invited some researchers working on DRPLA projects, key opinion leaders in the field and representatives of pharmaceutical companies and biotech. These conferences have become crucial to our research program as scientists have shared knowledge and progress around the different projects and been able to foster collaborations. For representatives of pharmaceutical companies and biotech, our conferences have become an example of our dedication to this mission and provided a chance for them to realize the scope of our collective and collaborative efforts.

In order to keep the patient and caregiver community informed, we organize an online event once a year in which we provide a lay update of our work and the progress made in the research projects we fund. During the year, we provide updates on our social media channels and website – for example, we moderate a closed Facebook group with 151 members, which for us is the best tool to communicate our work and create a sense of belonging. Earlier this year, we launched a newsletter that we send every 6 to 8 weeks, and it has been very well received. 14

Since DRPLA is most prevalent in Japan, we have made sure that our communications are also available to DRPLA families in Japan, in Japanese. A member of CureDRPLA is from Japan and has been responsible for setting up a closed Facebook group for Japanese-speakers. We have also featured our work twice on the Japanese Association of Ataxia Patients’s newsletter (also known as Tomonokai).

Now that our work is reaching the DRPLA patient community, and we have established connections with medical professionals who provide care for DRPLA patients, we have launched an initiative to accredit ‘DRPLA Centers of Excellence’, adapting the scheme of specialist ataxia centers to our needs and resources available. 15 We will give accreditations to those neurologists who have experience in DRPLA care and commit to supporting the work of our organization. In addition to providing expert clinical care and identifying the various needs of those diagnosed with DRPLA, the centers must have an ongoing interest in research into DRPLA. With this initiative, we aim to help families more easily identify clinical experts in DRPLA for their healthcare needs.

Therapeutic strategies

While there are no disease-modifying treatments for DRPLA, the only approach available involves managing symptoms albeit with limitations. 16 We briefly summarize potential therapies for DRPLA, with a focus on ATN1-lowering strategies. Advances in understanding DRPLA at the mechanistic level are crucial, and research in this area is benefiting from knowledge gained from other polyQ repeat disorders, most notably Huntington’s disease (HD), another autosomal dominant disease caused by polyQ repeat expansion that shares commonalities with DRPLA. Given its much higher prevalence, more therapeutic attention has focused on HD compared with DRPLA, and a large number of clinical trials in HD are underway. 17 A particular focus for the HD therapeutic community has been on lowering the levels of the mutant huntingtin protein, whose CAG-expansion mutation underlies HD. 18 A similar focus on lowering mutant, CAG-expanded, protein has also occurred in other polyQ diseases including spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1 19 ) and 3 (SCA3 20 ).

Following a similar logic to the HD and SCA fields, our primary therapeutic modality of interest is ATN1-lowering to downregulate the levels of toxic mutant polyQ protein levels in the brain of DRPLA patients. Currently, RNA-targeting therapies are our primary focus of interest for the treatment of DRPLA, given their advanced state of clinical development for neurological indications compared with DNA-targeted genome editing techniques. In particular, ASOs, which induce cleavage of the RNA encoding the toxic polyQ protein, are of great interest given their rapid advances in neurological diseases. Specifically, ASOs are being tested in clinical trials for other polyQ repeat disorders – a phase 1/2a open-label trial for SCA1, SCA2, and HD is investigating VO659, an ASO that binds to expanded CAG repeats and reduces harmful polyQ mutant protein levels [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05822908]. In addition, Tominersen, an ASO targeting Htt, is currently being tested in a phase-2 study [GENERATION-HD 2; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05686551], after an initial failure in a phase-3 failure in HD patients. 21 Finally, Wave Life Sciences is testing WVE-003 in a phase-1/2 study of an ASO targeting Htt in an allele-specific manner [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05032196]. Although ASO therapies are not yet approved for other polyQ repeat disorders, they have found recent success in treating other neurodegenerative diseases, including spinal muscular atrophy (Nusinersen 21 ), Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Eteplisren 22 ) and SOD1-ALS (Tofersen 23 ). CureDRPLA is actively funding multiple research projects to test ATN1-targeting ASOs, including accumulating evidence and proof-of-concept for ASO therapy in DRPLA mouse models (a non-exhaustive list is available on CureDRPLA website 24 ).

RNA interference technology has made relevant strides in silencing the expression of target mutant genes, advances that could be relevant for DRPLA. Preliminary studies suggested that it is possible to target expanded CAG repeats with RNA technology and a single compound could be used to treat multiple polyQ diseases, including DRPLA.25–27 We have watched with great interest the rapid advancement of genome engineering approaches as potential therapeutic approach to genetic disease, including a recent approval of a CRISPR-Cas9 therapy (Casgevy) to treating sickle-cell disease and β-thalassaemia [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03745287]. 28 And, indeed, similar genome engineering approaches have been shown protective in preclinical studies in, a Htt lowering approach in HD, 29 and CAG expansion reduction approaches in SCA3. 30 While exciting, several factors have caused CureDRPLA to take a cautious approach to supporting (epi-)genome engineering approaches. First, none has been approved for any neurological disease, suggesting that the time scale for these approaches to reach the clinic is beyond our horizon. Second, because DRPLA diffusely impacts many structures within the brain, we perceive delivery challenges for gene therapy approaches to be particularly challenging in DRPLA.

While our primary focus is on ATN1-lowering strategies, we remain optimistic that druggable pathways involved in multiple neurodegenerative diseases may provide fruitful for DRPLA therapeutics. Autophagy is stalled in DRPLA mice models and in human fibroblasts from patients with DRPLA. 31 Logically, therapeutics that activate autophagy in neuronal cells could be of interest as potential treatments for DRPLA. Limited evidence indicates the possible involvement of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of DRPLA, particularly in juvenile-onset cases with epilepsy. 32 Small molecules countering oxidative stress, therefore, warrant exploration for DRPLA.

Challenges and future directions

As CureDRPLA endeavors to advance research and treatments for DRPLA, several challenges and future directions have become clear. While substantial progress has been made, several hurdles must be addressed to comprehensively understand and effectively manage and treat this ultra-rare neurodegenerative disorder.

Despite being poorly described outside of Japan 4 and a few clusters in Europe,11,33,34 the prevalence of DRPLA is gradually being elucidated through outreach efforts and the CureDRPLA Global Patient Registry [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT05489393]. DRPLA exhibits pronounced genetic anticipation,7,8 and this phenomenon poses challenges in predicting the age of onset and the severity of symptoms. The ongoing DRPLA NHBS aims to identify biomarkers and clinical measures predictive of disease progression, contributing to future trial design. However, the rarity of DRPLA and its diverse manifestations 3 present challenges in recruiting a sufficiently large and representative patient cohort for clinical trials. International collaboration and continuous efforts to engage with neurologists worldwide are essential to overcome these recruitment challenges.

The autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of DRPLA results in multiple family members being affected, placing a significant emotional and physical burden on caregivers.11,13,16 The anticipation-driven earlier onset of symptoms with each generation adds another layer of complexity. Addressing the unique needs of caregivers and providing a robust support system is essential to enhance the overall well-being of affected families. Although CureDRPLA has made commendable strides in global outreach, the ongoing challenge lies in identifying and connecting with DRPLA patients worldwide, particularly in Asia, where the disease is most common. The organization’s initiative to accredit ‘DRPLA Centers of Excellence’ is a positive step, but sustaining and expanding this network requires continuous efforts. Cultural and linguistic diversity further complicates awareness campaigns, necessitating tailored approaches for different regions.

As potential therapies for DRPLA progress, navigating regulatory pathways and fostering collaboration with pharmaceutical companies and biotech entities become critical. Bridging the gap between promising preclinical research findings and its clinical application requires effective communication, collaboration, and adherence to regulatory standards.

In conclusion, although CureDRPLA has achieved significant milestones in advancing research and awareness, addressing these challenges will be pivotal for the organization’s continued success. The commitment to a multi-faceted approach, collaboration with global stakeholders, and adaptability to emerging scientific and clinical insights will play a crucial role in shaping the future of DRPLA research and treatment.

As we reflect on the achievements of CureDRPLA and their ongoing efforts, it becomes evident that the challenges are not insurmountable but require a collective, sustained effort from the scientific community, policymakers, and PAGs. The pursuit of therapeutic advancements for rare diseases is a marathon, not a sprint, and the torchbearers like CureDRPLA illuminate a path toward a future where effective treatments are within reach.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the research participants for their time and dedication to supporting our efforts. Additionally, we thank all the researchers that have participated and are participating in DRPLA research projects, in particular all the scientists that have developed the resources listed under Table 1. For human cellular models, we would like to thank Elizabeth Ross, Vikram Khurana, Timothy Yu, Joanna Korecka-Roet, Tojo Nakayama, and Claudia Lentucci. For mouse models, we would like to thank Taconic, Aliza Ben-Varon, and Velvet Smith. For DRPLA NHBS, we would like to thank the study investigators that participated in developing the study and the protocol Paola Giunti, Yael Shiloh, Henry Houlden, Claire Miller, and Hector Garcia-Moreno, Ola Volhin, Ellie Self, Yulissa Gonzalez, Danika Anganoo-Khan, Joseph Binu, Diana Cejas, Zheng Fan, Thomas Massey, Silvia Grimaldi, Jee-Young Lee and all the study collaborators. For the CureDRPLA Global Patient registry, we would like to thank the Governance Board Members Julie Greenfield, Barry Hunt, Graham McClelland, Silvia Grimaldi, and Paul Compton. For the collection of lived experiences we would like to thank NAF staff, Marielle Contesse, Rebecca Woods, Mindy Leffler, and Julie Greenfield.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Silvia Prades  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8561-2919

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8561-2919

Contributor Information

Silvia Prades, Ataxia UK, 12 Broadbent Close, London N6 5JW, UK; CureDRPLA, Brooklyn, NY, USA.

Andrea Compton, CureDRPLA, Brooklyn, NY, USA.

Jeffrey B. Carroll, CureDRPLA, Brooklyn, NY, USA Department of Neurology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Ethical approval and informed consent were not required for this review.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Silvia Prades: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Andrea Compton: Funding acquisition; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Writing – review & editing.

Jeffrey B. Carroll: Conceptualization; Investigation; Project administration; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: JBC received financial support from CureDRPLA to develop and characterize the humanized DRPLA mouse models.

SP declares no competing interests. JBC is a paid advisor for Cajal Neuroscience and Guidepoint. He has received research support from Ionis Pharmaceuticals and Wave Life Sciences.

Availability of data and materials: Data from the patient registry can be requested by contacting the author Silvia Prades, PhD. Access to the resources listed on this article like cell lines and mouse models can be facilitated via the authors. Please contact Silvia Prades, PhD with any questions and/or requests at info@curedrpla.org.

References

- 1. Ikeuchi T, Koide R, Tanaka H, et al. Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy: clinical features are closely related to unstable expansions of trinucleotide (CAG) repeat. Ann Neurol 1995; 37: 769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kanazawa I. Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy or Naito-Oyanagi disease. Neurogenetics 1998; 2: 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carroll LS, Massey TH, Wardle M, et al. Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy: an update. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov 2018; 8: 577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tsuji S, Onodera O, Goto J, et al. Sporadic ataxias in Japan – a population-based epidemiological study. Cerebellum 2008; 7: 189–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nowak B, Kozlowska E, Pawlik W, et al. Atrophin-1 function and dysfunction in dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy. Mov Disord 2023; 38: 526–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Suzuki Y, Yazawa I. Pathological accumulation of atrophin-1 in dentatorubralpallidoluysian atrophy. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2011; 4: 378–384. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hasegawa A, Ikeuchi T, Koike R, et al. Long-term disability and prognosis in dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy: a correlation with CAG repeat length. Mov Disord 2010; 25: 1694–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koide R, Ikeuchi T, Onodera O, et al. Unstable expansion of CAG repeat in hereditary dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA). Nat Genet 1994; 6: 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Egawa K, Takahashi Y, Kubota Y, et al. Electroclinical features of epilepsy in patients with juvenile type dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy. Epilepsia 2008; 49: 2041–2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wardle M, Morris HR, Robertson NP. Clinical and genetic characteristics of non-Asian dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy: a systematic review. Mov Disord 2009; 24: 1636–1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grimaldi S, Cupidi C, Smirne N, et al. The largest caucasian kindred with dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy: a founder mutation in italy. Mov Disord 2019; 34: 1919–1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maruyama S, Saito Y, Nakagawa E, et al. Importance of CAG repeat length in childhood-onset dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy. J Neurol 2012; 259: 2329–2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Compton A. Externally led-patient focused drug development meeting – September 25, 2020. CureDRPLA, https://curedrpla.org/en/2022/04/29/externally-led-patient-focused-drug-development-meeting-september-25-2020/ (2022, accessed 26 December 2023).

- 14. Newsletter. CureDRPLA, https://curedrpla.org/en/newsletter/ (2023, accessed 26 December 2023).

- 15. Morris S, Vallortigara J, Greenfield J, et al. Impact of specialist ataxia centres on health service resource utilisation and costs across Europe: cross-sectional survey. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2023; 18: 382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prades S, Melo de Gusmao C, Grimaldi S, et al. DRPLA. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al. (eds.) GeneReviews®. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wiggins R, Feigin A. Emerging therapeutics in Huntington’s disease. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2021; 26: 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tabrizi SJ, Ghosh R, Leavitt BR. Huntingtin lowering strategies for disease modification in Huntington’s disease. Neuron 2019; 101: 801–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Friedrich J, Kordasiewicz HB, O’Callaghan B, et al. Antisense oligonucleotide-mediated ataxin-1 reduction prolongs survival in SCA1 mice and reveals disease-associated transcriptome profiles. JCI Insight 2018; 3: e123193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McLoughlin HS, Moore LR, Chopra R, et al. Oligonucleotide therapy mitigates disease in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 mice. Ann Neurol 2018; 84: 64–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Finkel RS, Mercuri E, Darras BT, et al. Nusinersen versus sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1723–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mendell JR, Rodino-Klapac LR, Sahenk Z, et al. Eteplirsen for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol 2013; 74: 637–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Miller TM, Cudkowicz ME, Genge A, et al. Trial of antisense oligonucleotide tofersen for SOD1 ALS. N Engl J Med 2022; 387: 1099–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Researchers & Industry. CureDRPLA, https://curedrpla.org/en/researchers-industry/ (2022, accessed 20 February 2024).

- 25. Hu J, Liu J, Narayanannair KJ, et al. Allele-selective inhibition of mutant atrophin-1 expression by duplex and single-stranded RNAs. Biochemistry 2014; 53: 4510–4518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ciesiolka A, Stroynowska-Czerwinska A, Joachimiak P, et al. Artificial miRNAs targeting CAG repeat expansion in ORFs cause rapid deadenylation and translation inhibition of mutant transcripts. Cell Mol Life Sci 2021; 78: 1577–1596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kotowska-Zimmer A, Ostrovska Y, Olejniczak M. Universal RNAi triggers for the specific inhibition of mutant huntingtin, atrophin-1, ataxin-3, and ataxin-7 expression. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2020; 19: 562–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wong C. UK first to approve CRISPR treatment for diseases: what you need to know. Nature 2023; 623: 676–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang S, Chang R, Yang H, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing ameliorates neurotoxicity in mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J Clin Invest 2017; 127: 2719–2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. He L, Wang S, Peng L, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated gene correction ameliorates abnormal phenotypes in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells. Transl Psychiatry 2021; 11: 479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baron O, Boudi A, Dias C, et al. Stall in canonical autophagy-lysosome pathways prompts nucleophagy-based nuclear breakdown in neurodegeneration. Curr Biol 2017; 27: 3626–3642.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miyata R, Hayashi M, Tanuma N, et al. Oxidative stress in neurodegeneration in dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy. J Neurol Sci 2008; 264: 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chaudhry A, Athanasiou-Fragkouli A, Garcia-Moreno H, et al. Correction to: DRPLA: understanding the natural history and developing biomarkers to accelerate therapeutic trials in a globally rare repeat expansion disorder. J Neurol 2021; 268: 3042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wardle M, Majounie E, Williams NM, et al. Dentatorubral pallidoluysian atrophy in South Wales. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008; 79: 804–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]