ABSTRACT

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a human restricted pathogen, releases inflammatory peptidoglycan (PG) fragments that contribute to the pathophysiology of pelvic inflammatory disease. The genus Neisseria is also home to multiple species of human- or animal-associated Neisseria that form part of the normal microbiota. Here we characterized PG release from the human-associated nonpathogenic species Neisseria lactamica and Neisseria mucosa and animal-associated Neisseria from macaques and wild mice. An N. mucosa strain and an N. lactamica strain were found to release limited amounts of the proinflammatory monomeric PG fragments. However, a single amino acid difference in the PG fragment permease AmpG resulted in increased PG fragment release in a second N. lactamica strain examined. Neisseria isolated from macaques also showed substantial release of PG monomers. The mouse colonizer Neisseria musculi exhibited PG fragment release similar to that seen in N. gonorrhoeae with PG monomers being the predominant fragments released. All the human-associated species were able to stimulate NOD1 and NOD2 responses. N. musculi was a poor inducer of mouse NOD1, but ldcA mutation increased this response. The ability to genetically manipulate N. musculi and examine effects of different PG fragments or differing amounts of PG fragments during mouse colonization will lead to a better understanding of the roles of PG in Neisseria infections. Overall, we found that only some nonpathogenic Neisseria have diminished release of proinflammatory PG fragments, and there are differences even within a species as to types and amounts of PG fragments released.

KEYWORDS: Neisseria, peptidoglycan, ldcA, ampG, NOD1, NOD2, inflammation, immune response

INTRODUCTION

The genus Neisseria contains multiple species of Gram-negative bacteria with varying cell morphology and niches. Neisseria spp. are almost always found associated with higher-order host organisms, which include multiple species of insects, birds and waterfowl, land and marine mammals, as well as the rhinoceros iguana and the marsupial quokka (1). The most well studied of the Neisseria sp. are Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis, which are human-restricted pathogens and etiological agents for the sexually transmitted infection gonorrhea and invasive meningococcal disease, respectively. Most species in this genus are nonpathogenic colonizers of mucosal surfaces of their respective host organism. In fact, N. meningitidis has a nonpathogenic lifestyle as a colonizer of the naso- and oropharyngeal space of healthy adults (2). Like N. meningitidis, the major niche occupied by commensal mammal-associated Neisseria is the oral and nasopharyngeal space. Neisseria spp. are considered part of the core oral microbiome of healthy humans and constitute up to 8% of the oral microbiota of humans (3–5).

The nonpathogenic species of Neisseria used in this study are all colonizers of mammals. Neisseria lactamica and Neisseria mucosa are associated with humans. The newly recognized species, Neisseria musculi, was isolated from wild house mice (6). The macaque isolates AP312 and AP678 were isolated from macaques housed in a national primate center (7). In terms of cell morphology, N. lactamica, N. mucosa, and macaque isolates AP312 and AP678 are all diplococci, while N. musculi is a rod-shaped bacterium (1, 6, 7). There are temporal and tissue-specific colonization patterns in different species of nonpathogenic Neisseria. For example, N. lactamica carriage rates are higher in children compared to adults, and nasopharyngeal colonization by N. lactamica protects against colonization by N. meningitidis (8–10). In contrast, N. meningitidis is commonly found in the throat of adults (8, 11). N. mucosa is mostly found in the gingival plaque and tooth surfaces of children and adults but does not appear to contribute to exacerbating or preventing tooth decay (11, 12). N. musculi was isolated from the mouths of wild mice but is able to colonize both the oral cavity and the gastrointestinal tract of mice in the laboratory (13). Although the macaque isolates colonize the nasopharyngeal and oral cavities of rhesus macaques, AP312 was initially isolated from a bite wound on a macaque (7).

Despite their roles as part of the core oral microbiome, nonpathogenic human-associated Neisseria spp. encode several virulence-associated factors and, in rare cases, will cause disease in people who are immunocompromised and have pre-existing risk factors or post-trauma, such as heart damage or tooth extraction (14, 15). Some diseases caused by commensal Neisseria spp. include high-fatality diseases like meningitis, septicemia, and endocarditis, as well as conjunctivitis, respiratory tract infections, and pneumonia (14). Multiple cases of endocarditis by commensal Neisseria spp. have occurred after dental procedures most likely due to oral wounds sustained from these procedures that provided a direct route for the bacteria to travel from the mouth to the bloodstream (14). Factors that favor colonization by these nonpathogenic Neisseria spp., while not promoting inflammation and disease, are not clear.

One factor that was previously found to differ between the inflammation-inducing species N. gonorrhoeae and the more commensal species N. meningitidis, N. mucosa, and Neisseria sicca is the release of peptidoglycan fragments, with the commensal species releasing about one-third as much of the proinflammatory molecules (16). Peptidoglycan (PG) makes up the bacterial cell wall and confers cell shape and protection against osmotic shock. PG consists of a glycan backbone of repeating subunits of N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc), with peptide stems extending off MurNAc that can be crosslinked to adjacent peptide stems forming a mesh-like structure. Because of PG remodeling to allow for cell enlargement and cell separation, small PG fragments are liberated from the sacculus during growth (17). In Gram-negative bacteria, these PG fragments are usually taken back into the cytoplasm to be recycled for reuse in the cell wall or general cellular metabolism. A limited number of Gram-negative bacteria, including the human pathogens N. gonorrhoeae, N. meningitidis, and Bordetella pertussis release sufficient amounts of proinflammatory PG fragments to stimulate production of proinflammatory cytokines in tissue explants (18–21). NOD1 and NOD2 are immune receptors found in host cells that are activated by small PG fragments (22, 23).

In this study, we characterized the PG fragments released by nonpathogenic human- and animal-associated Neisseria and their ability to activate NOD1 and/or NOD2. We hypothesized that lower amounts of PG fragment release might allow for continued colonization and not produce inflammatory responses that could lead to clearance of the bacteria. We found that PG fragment release from human-associated species N. mucosa and one strain of N. lactamica was similar to that previously seen in N. meningitidis or N. sicca, with low amounts of PG monomer released and more of the PG fragments being broken down into free sugars and free peptides. However, a different strain of N. lactamica exhibited PG fragment release similar to N. gonorrhoeae with large amounts of PG monomers released. We found that an amino acid difference in the PG fragment permease AmpG was responsible for the differing amounts of PG fragments released by N. lactamica, and a minority of strains encode the inefficient AmpG variant. The animal-associated species also released PG fragments, with some differences in the amounts of specific types of fragments released. N. musculi showed a PG fragment profile similar to N. gonorrhoeae though with lower amounts of PG released. Mutations affecting PG processing or recycling in N. musculi were made and affected amounts of PG released and mouse NOD1-mediated responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

All strains used are listed in Table 1. All Neisseria strains are grown at 37°C either on gonococcal base (GCB) medium (Difco) agar plates with 5% CO2 or in gonococcal base liquid medium with 0.042% NaHCO3 and Kellogg’s supplements (cGCBL) (24, 25). When necessary, 80-µg/mL kanamycin was added to the growth medium. Escherichia coli strains were grown on lysogeny broth (LB) agar or in LB broth (Difco) at 37°C. The growth medium was supplemented with 40-µg/mL kanamycin, 500-µg/mL erythromycin, or 25-µg/mL chloramphenicol as needed.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain/plasmid | Description | Source/reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||||

| N. mucosa ATCCa 25996 | N. mucosa pharyngeal isolate | ATCC | ||

| N. lactamica ATCC 49142 | N. lactamica clinical isolate | ATCC | ||

| N. lactamica ATCC 23970 | N. lactamica nasopharyngeal isolate | ATCC | ||

| N. musculi AP2031 | N. musculi oral isolate, rough morphotype | (6) | ||

| Macaque isolate AP312 | Neisseria bite wound isolate | (7) | ||

| Macaque isolate AP678 | Neisseria nasopharyngeal isolate | (7) | ||

| N. gonorrhoeae MS11 | N. gonorrhoeae clinical isolate | (26) | ||

| DG132 | MS11 ΔampGGC | (27) | ||

| EC2000 | AP312 ampG::cat | This study | ||

| EC2003 | ATCC25996 ampG::kan | (16) | ||

| EC2005 | AP2031 ampG::kan | This study | ||

| EC540 | MS11 ampGGC− ampGNL23970+ | This study | ||

| EC544 | MS11 ampGGC− ampGNL49142+ | This study | ||

| EC561 | MS11 ampGGC− ampGNL49142T272A+ | This study | ||

| EC564 | MS11 ampGGC− ampGNL23970 A272T+ | This study | ||

| Plasmids | ||||

| pIDN3 | Cloning vector (ErmR) | (28) | ||

| pKH6 | Cloning vector (CmR); source of cat | (29) | ||

| pHSS6 | Cloning vector (KanR), source of kan | (30) | ||

| pEC012 | ampGAP312::cat in pIDN3 | This study | ||

| pEC088 | PampGGC-ampGNL49142 in pIDN3 | This study | ||

| pEC089 | PampGGC-ampGNL23970 in pIDN3 | This study | ||

| pEC095 | ampGNmus in pIDN3 | This study | ||

| pEC096 | ampGNmus::kan in pIDN3 | This study | ||

| pEC113 | PampGGC-ampGNL49142T272A in pIDN3 | This study | ||

| pEC116 | PampGGC-ampGNL23970A272T in pIDN3 | This study | ||

| pNmCompErm | Gibson cloning N. musculi complementation plasmid | This study | ||

| pKHmus502 | ldcANmus in pKHmus, expression plasmid | This study | ||

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Strain and plasmid construction

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1, and primers are listed in Table 2. Spot transformation was used to generate Neisseria mutants (31). Briefly, around 0.5- to 1.0-µg plasmid DNA was digested with PciI with a subsequent heat-inactivation step to linearize the plasmid, and the digest reaction was spotted onto a pre-warmed GCB agar plate. Five to ten piliated colonies were then streaked over the DNA spots, and the plate was incubated at 37°C overnight. Colonies growing on the spots were restreaked onto fresh GCB plates for selection or screening. All transformants were screened by PCR and sequencing.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| MC ampG SacI F3 | ATTCAGAGCTCCATCGGCGGCATCATCAAAC |

| ampG 3′ flank R BamHI | CTCAGGATCCGTTCTTTATATGAGCGGCAGG |

| AP312 ampG SacI F | GTATTGAGCTCGTCTTGTTCGGATTTCGTCTG |

| AP312 ampG BamHI R | GACTAGGATCCGTCCATTACTTCGGCGTATATGC |

| SOE-NL ampG F | GCTGTACGAACGATGACTGCATCGAAATCAGG |

| SOE-NL ampG R | GTTTGACGCGTTCATCTGCCTGCATCCTGAG |

| NL SOE-MS11 ampG 5′ flank R | CCTGATTTCGATGCAGTCATCGTTCGTACAGC |

| NL SOE- MS11 ampG 3′ flank F | GCAGGCAGATGAACGCGTCAAACTGGAGCG |

| NL49142 AmpG T272A F | GATTGCGAAAAATGCAGGACTGTGGC |

| NL49142 AmpG T272A R | GCCACAGTCCTGCATTTTTCGCAATC |

| NL23970 ampG A272T F | GATTGCGAAAAATACAGGACTGTGGC |

| NL23970 ampG A272T R | GCCACAGTCCTGTATTTTTCGCAATC |

| AP2031 ampG SacI F | CGGCCGAGCTCCTTCGTTGATACAATAACC |

| AP2031 ampG BamHI R | CATTAGGATCCCGCAAACGGGTTTGCTGTGG |

| ASM F | AGAAGATCCTCCGGTAGTGTTGTCTGAAAATAAGGTTG |

| ASM R | TGAAAAGTGGGGCCGTCTGAACCACCGT |

| erm msc TetR F | TCAGACGGCCCCACTTTTCAGACGGCATAC |

| erm msc TetR R | CATACCATAAGTTATGCTGCTTTTAAGACCC |

| hyp F | GCAGCATACCTTATGTTATGCTGAAACCG |

| hyp R | GACGGCAAGCGTACGAAACACATCAAAC |

| ori F | TGTTTCGTACGCTTGCCGTCTGAAATGG |

| ori R | ACACTACCGGAGGATCTTCTTGAGATCCTTTTTTTC |

| ldcA F 2 bp Pro Fc | CGAATAAGAAGGCTGGCTCTGTTTTGCAAATGGAAAGTGGGCTCA |

| ldcA R FC musculi | CTAGTTCTAGAGCGGCCTACGCGCAGATTGTGATTGG |

| erm comp F FC | GGCCGCTCTAGAACTAGTGG |

| hyp FC | AGAGCCAGCCTTCTTATTCG |

To construct pEC012 (AP312 ampG::cat in pIDN3), AP312 ampG was first amplified from macaque isolate AP312 chromosomal DNA with primers AP312 ampG SacI F and AP312 ampG BamHI R, and subsequently digested with SacI, BamHI, DpnI, and EarI, resulting in two DNA fragments. The chloramphenicol resistance gene cat was excised from pKH6 by digestion with DpnI and EarI. The cloning vector pIDN3 was digested with SacI and BamHI. All four digest products were ligated together to form pEC012. Macaque isolate AP312 was transformed with pEC012 to make EC2000.

The insert for pEC088 (PampGGC-ampGNL49142 in pIDN3) was generated via overlap-extension PCR (OE-PCR). First, ampGNL49142 was amplified from N. lactamica ATCC 49142 chromosomal DNA using primers SOE-NL ampG F and SOE-NL ampG R. Approximately 1-kb ampGGC upstream and downstream regions, which include the native ampGGC promoter and transcriptional terminator, were amplified from N. gonorrhoeae MS11 chromosomal DNA using primer pairs MC ampG SacI F3/NL SOE-MS11 ampG 5′ flank R and NL SOE-MS11 ampG 3′ flank F/ampG 3′ flank R BamHI, respectively. The three PCR products were used as templates in OE-PCR with primers MC ampG SacI F3 and ampG 3′ flank R BamHI. The final PCR product was digested with SacI and BamHI and ligated into similarly digested pIDN3 to form pEC088. pEC089 (PampGGC-ampGNL23970 in pIDN3) was constructed almost exactly as pEC088; the only exception is that ampGNL23970 was amplified from N. lactamica ATCC 23970 chromosomal DNA. Transformation of N. gonorrhoeae MS11 with pEC088 or pEC089 yielded EC544 and EC540, respectively.

To generate pEC095 (ampGNmus in pIDN3), ampGNmus was amplified from N. musculi AP2031 chromosomal DNA using primers AP2031 ampG SacI F and AP2031 ampG BamHI R, digested with SacI and BamHI and ligated into similarly digested pIDN3. Plasmid pEC095 was digested with BtsBI, and the 5′ overhanging DNA ends were filled in with T4 Polymerase (NEB). A kanamycin resistance marker, kan, was excised from pHSS6 by digestion with NheI and BamHI, treated with T4 Polymerase, and blunt-ligated with the BtsBI-digested pEC095 to form pEC096 (ampGNmus::kan in pIDN3). Plasmid pEC096 was transformed into N. musculi AP2031 to generate EC2005.

Plasmid pEC088 was used as template in two PCR reactions with primer pairs MC ampG SacI F3/NL49142 ampG T272A F and NL49142 ampG T272A R/ampG 3′ flank R BamHI. The primer sequences of NL49142 ampG T272A F and NL49142 ampG T272A R contain a missense mutation (ACA → GCA) that would result in substitution of residue 272 from a threonine to an alanine in the final gene product. The two PCR products were used in OE-PCR with primers MC ampG SacI F3 and ampG 3′ flank R BamHI, and the final OE-PCR product was digested with SacI and BamHI and ligated into similarly digested pIDN3 to form pEC113 (PampGGC-ampGNL49142T272A in pIDN3). pEC116 (PampGGC-ampGNL23970A272T in pIDN3) was built with a strategy similar to pEC113, with two variations during the initial PCR reaction. Chromosomal DNA from EC540 was used as template in the PCR reaction, with primer pairs MC ampG SacI F3/NL23970 ampG A272T F and NL23970 ampG A272T R/ampG 3′ flank R BamHI instead. N. gonorrhoeae MS11 was transformed with pEC113 or pEC116 to form EC561 and EC564, respectively.

To create a complementation plasmid for N. musculi, the adenine-specific methyltransferase and a downstream gene for a hypothetical protein were amplified from AP2031 (rough isolate) chromosomal DNA using primers ASM-F and ASM-R, in addition to hyp-F and hyp-R. The plasmid origin was amplified from pIDN1 using oriF and oriR, and a region containing ermC, the tet repressor, and inducible promoter/operator were amplified from pKH18 using primers erm mcs TetR F and erm mcs TetR R. The final plasmid pNmCompErm was constructed using Gibson assembly.

An ldcA overexpression plasmid for N. musculi was created by amplifying a constitutively expressed version of ldcA using primers ldcA 2bp F Pro Fc and ldcA R FC musculi and amplifying the pNmCompErm plasmid using primers erm comp F FC and hyp FC. The final plasmid pKHmus2 was created using Gibson assembly.

Metabolic labeling of peptidoglycan with [3H] glucosamine or [3H] DAP and quantitative fragment release

Metabolic labeling of PG with [6-3H]-glucosamine or [2,6-3H]-diaminopimelic acid (DAP) and quantitative fragment release was performed as described previously for N. gonorrhoeae (16, 27). For [6-3H]-glucosamine labeling, strains were grown in cGCBL to mid-log phase, diluted to an OD540 of 0.2, and pulse labeled with 10-µCi/mL [6-3H]-glucosamine in GCBL supplemented with 0.042% NaHCO3 and modified Kellogg’s supplements containing pyruvate instead of glucose for 30 minutes. The cells were washed to remove unincorporated label and resuspended in GCBL containing supplements and glucose for the chase period. The cells were grown for 2.5 hours, after which cell-free supernatant was harvested by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 10 minutes and filtration using a 0.22-µm filter. For quantitative fragment release, the amounts of radiation measured in counts per minute (CPM) in the cell pellets were determined by liquid scintillation counting prior to the chase period and normalized to each other. Labeling with [2,6-3H]-DAP was performed in a similar way as labeling with [6-3H]-glucosamine, with variations in the pulse labeling phase. Strains were grown in DMEM lacking cysteine supplemented with 25-µCi/mL [2,6-3H]-DAP, 100-µg/mL threonine, and 100-µg/mL methionine for 60 minutes for the labeling phase. Released radiolabeled PG fragments are separated by size-exclusion chromatography and detected by liquid scintillation counting.

Bioinformatic analysis of polymorphism of AmpG residue 272 in Neisseria lactamica

AmpG sequence analysis was conducted using sequences hosted on BIGSdb (accessed 22 February 2024 from https://pubmlst.org/organisms/neisseria-spp) and the NCBI database, with organism search restricted to “Neisseria lactamica” (taxid 486), using built-in tblastn functions with N. gonorrhoeae MS11 AmpG sequence as query (NCBI accession number CP003909.1) (32, 33). A total of 1,119 AmpG sequences were retrieved, aligned using Clustal Omega, and further analyzed using JalView version 2.11.3.2 (34, 35).

Modeling of N. lactamica AmpG structures

The predicted AmpG structures for N. lactamica ATCC 49142 and N. lactamica ATCC 23970 were generated using AlphaFold2 via ChimeraX version 1.7 (36, 37). Alignment and visualization of AmpG structures and residue 272 were performed using PyMol version 2.5.

NOD1 and NOD2 activation with HEK293 reporter cells

NOD1 and NOD2 activation were measured using HEK293 reporter cells. Briefly, bacterial strains were grown to mid-log phase in cGCBL from an initial OD540 of 0.2. Cells were removed by centrifugation, and supernatants were passed through a 0.2 µM filter. Supernatants were normalized by dilution with GCBL, based on total protein content of cells in the cultures, and added to HEK293 reporter cells overexpressing NOD1 or NOD2 as described in reference (29). NF-κB activation was measured at OD650 after incubation of cell supernatants in QUANTI-Blue medium as described in the manufacturer’s instructions (InvivoGen).

RESULTS

Nonpathogenic Neisseria spp. release PG fragments

PG fragments released by growing N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis have been previously characterized through the method of metabolic pulse-chase labeling of the PG with [3H]-glucosamine (glcNH2) and [3H]-DAP, which labels the glycan backbone and peptide stems of PG, respectively (19, 38–40). [3H]-Glucosamine labeled PG fragments released by wild-type (WT) cells are PG dimers, tetrasaccharide-peptide, PG monomers, free disaccharide, and free anhydro-N-acetylmuramic acid. [3H]-DAP labeled PG fragments are PG dimers, tetrasaccharide-peptide, PG monomers, free tetrapeptide and free tripeptide (in one peak), and free dipeptide (in a second peptide peak). Any DAP that was unincorporated will appear as a shoulder on the dipeptide peak. The known structures of the released PG fragments are summarized in Fig. 1A. The major inflammatory molecules released are the PG dimers, PG monomers, and free tetrapeptide and tripeptide (Fig. 1B) (39). PG dimers that are digested by host lysozyme yield PG monomers with reducing ends, and these molecules are NOD2 agonists (41). The tripeptide PG monomers and the free tripeptides are human NOD1 agonists, while the tetrapeptide PG monomers and free tetrapeptides are mouse NOD1 agonists (22, 42). Small amounts of dipeptide PG monomers are released and serve as NOD2 agonists (43).

Fig 1.

(A) Peptidoglycan (PG) fragments released into the milieu by Neisseria spp. (B) Peptidoglycan fragments that stimulate the human or mouse pattern recognition receptor NOD1 or that stimulate NOD2 in both species. Cartoon depictions of the PG fragments found in gonococcal supernatants use symbols from Jacobs et al. (44).

We performed metabolic, pulse-chase labeling of the PG of the human-associated species N. mucosa. Consistent with previous studies, N. mucosa labeled with [6-3H]-glucosamine released PG monomers, free disaccharide, and anhydro-MurNAc but did not release any detectable PG dimers (Fig. 2A). To also examine PG-derived peptides released by N. mucosa, we used metabolic labeling with [2,6-3H]-DAP. DAP-labeled PG fragments released by N. mucosa included PG monomers, free tetrapeptide and tripeptide, and free dipeptide (Fig. 2B). Again, no PG dimer release was detected. A quantitative comparison with PG fragments released by N. gonorrhoeae showed that N. mucosa released lower amounts of PG monomer, as previously noted (16), and released larger amounts of free tetrapeptide and tripeptide (Fig. 2B). Thus, PG monomer release in N. mucosa is mostly similar to what is seen with N. meningitidis, with larger amounts of PG fragments being broken down to free peptides and sugars and less being released as intact PG monomers.

Fig 2.

PG fragment release from nonpathogenic, human-associated species Neisseria mucosa strain ATCC 25996. The PG fragments released were separated by size-exclusion chromatography. (A) PG fragments released during the chase period following metabolic labeling of PG with [3H]-glucosamine (glcNH2). (B) PG fragments released from N. mucosa following [3H]-DAP labeling compared quantitatively to those released by N. gonorrhoeae.

We examined PG fragment release in the human-associated species N. lactamica, examining strains ATCC 23970 and ATCC 49142. Attempts to metabolically label PG in these two isolates using [6-3H]-glucosamine were not successful. Therefore, we turned to labeling of the PG peptide chains using [2,6-3H]-DAP. The PG fragment release profile of ATCC 23970 showed characteristics similar to N. mucosa in that ATCC 23970 released larger amounts of free peptides and lower amounts of PG monomers (Fig. 3A). Unlike N. mucosa, ATCC 23970 released measurable amounts of PG dimers and tetrasaccharide-peptide. Overall, these data indicate that N. lactamica ATCC 23970 is similar to N. mucosa and N. meningitidis in substantially breaking down PG fragments via the AmiC-LtgC pathway prior to fragment release (40). By contrast, the N. lactamica ATCC 49142 PG fragments released were made up of PG monomers and free peptides in approximately equal amounts, similar to the PG fragment release seen with N. gonorrhoeae (Fig. 3B). Like ATCC 23970, ATCC 49142 also released PG dimers.

Fig 3.

PG fragments released by Neisseria lactamica strain ATCC 23970 (A) or N. lactamica strain ATCC 49142 (B) following metabolic labeling with [3H]-DAP. ATCC 23970 breaks down more of its PG fragments before release, resulting in the most abundant fragments being tetrapeptides and tripeptides, similar to the results seen with N. mucosa. ATCC 49142 releases substantial amounts of PG monomers as well as free tetrapeptides and tripeptides.

The difference in PG monomer release by N. lactamica ATCC 23970 and N. lactamica ATCC 49142 is partially due to a single-nucleotide polymorphism in AmpG

A major difference in PG fragment release between N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis is due to amino acid differences in the sequence of the PG fragment permease AmpG (16). AmpG functions in both species to transport anhydro-disaccharide containing PG fragments into the cytoplasm for recycling, but due to the amino acid differences, N. gonorrhoeae AmpG is less efficient, and three- to fourfold more PG monomers are released by N. gonorrhoeae than by N. meningitidis.

To examine PG recycling in N. lactamica, we attempted to mutate N. lactamica ampG, but we were unable to genetically manipulate either of the N. lactamica isolates. As an alternative strategy, we expressed N. lactamica ATCC 23970 ampG (ampGNL23970) or N. lactamica ATCC 49142 ampG (ampGNL49142) in N. gonorrhoeae in lieu of the native gonococcal ampG (ampGGC). Expression of N. lactamica ampG in this background is driven by the native ampGGC promoter. Determination of the amount of PG monomers released by the allelic replacement mutants relative to the amount released by WT N. gonorrhoeae allows us to determine if N. lactamica AmpG is more, less, or equally efficient as AmpGGC. Expression of ampGNL23970, but not of ampGNL49142, in N. gonorrhoeae resulted in lower levels of PG monomer release compared to WT N. gonorrhoeae (Fig. 4). The gonococcal strain expressing ampGNL49142 released similar levels of PG monomer as WT N. gonorrhoeae (Fig. 4). These results suggest that AmpGNL49142 transports similar amounts of PG monomer as AmpGGC, while AmpGNL23970 is the most efficient at recycling of the three.

Fig 4.

Function of N. lactamica ampG alleles assessed by metabolic labeling of PG with [6-3H]-glucosamine and size-exclusion chromatography separation of PG fragments released into the medium. Gonococcal ampG− strains expressing ampG from two different strains of N. lactamica released different amounts of PG monomer. The ampG gene from N. lactamica ATCC 49142 or N. lactamica ATCC 23970 was expressed in N. gonorrhoeae in lieu of the native gonococcal ampG gene. Expression of ampGNL23970 but not ampGNL49142 in N. gonorrhoeae reduced the amount of PG monomer released.

AmpGNL49142 and AmpGNL23970 differ by seven residues (Fig. S1). Previous work established that natural polymorphisms of gonococcal and meningococcal AmpG at residues 391, 398, and 402 contribute to differences in PG monomer release in these two pathogenic Neisseria (16). Both isolates of N. lactamica code for the same amino acids at AmpG positions 391, 398, and 402. We compared AmpG sequences from the two N. lactamica isolates, N. gonorrhoeae, and N. meningitidis, and one of the seven aforementioned residues is only found in AmpGNL49142 (Fig. S1). AmpG residue 272 is a threonine in N. lactamica ATCC 49142 and is an alanine in the other three species. We performed site-directed mutagenesis to determine if AmpG residue 272 plays a role in modulating AmpG efficiency in N. lactamica.

Expression of ampGNL49142T272A in N. gonorrhoeae lacking ampGGC resulted in lower levels of PG monomer release compared to WT N. gonorrhoeae (Fig. 5A), mimicking the phenotype seen when ampGNL23970 is expressed by N. gonorrhoeae. Additionally, expression of ampGNL23970A272T in N. gonorrhoeae resulted in WT-like levels of PG monomer release, which phenocopied the gonococcal strain expressing ampGNL49142 (Fig. 5B). We conclude that N. lactamica ATCC 23970 is better at recycling PG monomers compared to N. lactamica ATCC 49142 due to a polymorphism at AmpG site 272, which contributes in part to differences in the amount of PG fragments released by the two N. lactamica isolates.

Fig 5.

PG fragment release from N. gonorrhoeae expressing mutant versions of N. lactamica ampG alleles. Polymorphism of N. lactamica AmpG contributes to the differences in the amounts of PG monomer released. (A) N. gonorrhoeae lacking gonococcal ampG and instead expressing ampGNL49142 with a single substitution at AmpGNL49142 residue 272 from a threonine to an alanine shows reduced PG monomer release by approximately half. (B) N. gonorrhoeae expressing ampGNL23970 with a single substitution at AmpGNL23970 residue 272 from an alanine to a threonine released N. gonorrhoeae WT-like levels of PG monomer.

We examined N. lactamica genome sequences to determine how common changes were at amino acid 272 of AmpG. Examination of 1,119 N. lactamica genome sequences found that 990 (88.5%) had alanine at residue 272, and 129 (11.5%) had threonine (Fig. S2). No other amino acid was found at this position. Thus, T272 is rare, predicting that most N. lactamica strains will have an AmpG that functions efficiently for PG fragment recycling.

We used AlphaFold2 to predict the AmpG tertiary structure for N. lactamica ATCC 23970 and N. lactamica ATCC 49142. The two structures we obtained had a canonical MFS-transporter topology and aligned well together (Fig. S3) (45). Residue 272 was situated close to the middle of transmembrane helix 8; unfortunately, the structures did not provide clear mechanistic insights into how this polymorphism affects AmpG efficiency. One possibility is that the bulkier side chain on threonine may impede or slow the conformational changes required for PG monomer transport, as MFS transporters employ an “alternating-access” mode of action (45).

PG fragment release by animal-associated Neisseria

To determine if the macaque nasopharyngeal colonization model or the mouse oropharyngeal colonization model might be useful for examining the effects of PG fragment release in Neisseria infections, we characterized PG fragment release from macaque isolates AP312 and AP678 and from mouse isolate N. musculi. AP312 released PG monomers, free disaccharide, and anhydro-MurNAc, but little if any PG dimers (Fig. 6A). AP678 released PG dimers, PG monomers, and free disaccharide and monosaccharide (Fig. 6B). In addition, AP678 exhibited a large shoulder on the PG monomer peak, representing dipeptide PG monomers.

Fig 6.

PG fragment release from Neisseria spp. that colonize macaques. Macaque isolates AP312 (A) and AP678 (B) released different types and amounts of PG fragments as demonstrated by size-exclusion chromatography of [6-3H]-glucosamine labeled molecules released into the medium.

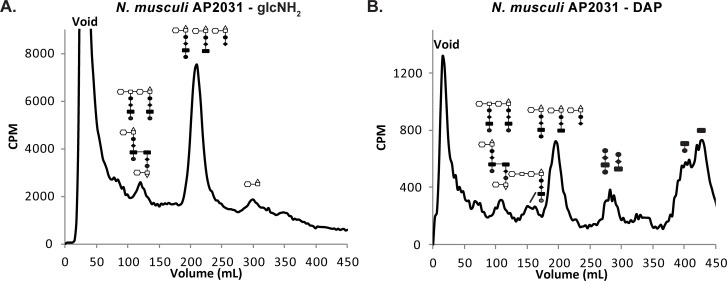

N. musculi released PG dimers, PG monomers, and free disaccharide (Fig. 7A). Examination of PG released using [2,6-3H]-DAP labeling demonstrated that N. musculi releases PG dimers, tetrasaccharide-peptide, PG monomers, and free peptides (Fig. 7B). In both the glucosamine labeling experiments and the DAP labeling experiments, PG monomers were the major PG fragments released.

Fig 7.

N. musculi releases a variety of PG fragments as determined from experiments using metabolic labeling with [3H]-glucosamine (A) or [3H]-DAP (B). The types of PG fragments released and their relative abundance are similar to that seen with N. gonorrhoeae in that the PG monomers are the most abundant fragments, and PG dimers, free disaccharide, and free peptides are all observed.

Analysis of PG recycling by animal-associated N. musculi and macaque isolate AP312 using mutation of ampG

AmpG transports PG monomers and anhydro-disaccharide from the periplasm to the cytoplasm for recycling (44, 46). By comparing the amount of PG released by ampG mutants compared to the amount released by WT strains, the normal amounts of glycan-containing PG fragments recycled and released can be calculated. We previously demonstrated that the human-associated species N. mucosa encodes a functional AmpG permease and recycles 95% of PG monomers liberated during growth (16).

We mutated ampG in N. musculi and macaque isolate AP312 by insertional inactivation with an antibiotic resistance marker and determined the PG fragment release profile of the ampG mutants. Mutation of ampG in N. musculi and macaque isolate AP312 resulted in 8.7- and 10.8-fold increases in PG monomer release, respectively, with modest changes to anhydro-disaccharide release (Fig. 8A and B). N. musculi releases around 11% of PG monomer generated during growth, while macaque isolate AP312 releases approximately 9% of PG monomers. Like other Neisseria spp., mutation of ampG did not alter PG dimer release in N. musculi or in macaque isolate AP312. This observation is consistent with the reported inability of E. coli AmpG to transport PG dimers and our previous results with ampG mutants of N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis (19, 27, 46).

Fig 8.

Mutation of ampG impaired PG fragment recycling in N. musculi and macaque symbiont AP312. Mutation of ampG in the macaque isolate AP312 (A) and N. musculi (B) resulted in large increases in the amount of PG monomer released, without affecting PG dimer release.

PG fragments released by nonpathogenic human-associated Neisseria stimulate hNOD1 and hNOD2 activation in HEK293 reporter cells

Recognition of bacterial products by the immune system is important to prevent or resolve infections, as well as to attune the immune response (47, 48). In humans, PG fragments are recognized by two intracellular receptors, human NOD1 (hNOD1) and NOD2 (hNOD2). hNOD1 responds to small PG fragments with a terminal DAP moiety (49) (Fig. 1B). hNOD2 binds to muramyl-dipeptide and also responds to reducing-end PG monomers, which are generated from PG dimers or longer strands by the action of host lysozyme (23, 41, 50) (Fig. 1B). PG monomers released by Neisseria have anhydro-ends instead of reducing ends due to the enzymatic activity of lytic transglycosylases that cleave the glycan backbone (38, 51, 52). The NOD receptors signal through two major pathways to induce an immune response, and one of those pathways results in activation of NF-κB (52). We sought to determine if PG fragments released by nonpathogenic Neisseria are capable of stimulating an hNOD and an NF-κB-dependent response.

To answer this question, we utilized HEK293 reporter cells that express a secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) under the control of an NF-κB promoter and measured the amount of SEAP in the supernatant using a colorimetric assay. We treated the NOD1- or NOD2-expressing reporter cell lines with cell-free supernatant from N. mucosa or N. lactamica isolates, as well as supernatant from N. gonorrhoeae for comparison. Our initial hypothesis was that nonpathogenic Neisseria would induce lower levels of NOD activation. However, most of our nonpathogenic strains induced similar levels of hNOD1 and hNOD2 activation as N. gonorrhoeae (Fig. 9A and B). The value for N. mucosa stimulation of hNOD1 was lower than that for N. gonorrhoeae, though the values were not statistically different. A lower level of stimulation would be consistent with the decreased PG monomer release seen in N. mucosa. N. lactamica ATCC 23970 induced higher levels of hNOD2 activation than N. gonorrhoeae and other Neisseria spp. in this assay (Fig. 9B). The increased hNOD2 activation by N. lactamica ATCC 23970 could be due to PG dipeptide monomer, seen as a shoulder on the right side of the PG monomer peak, or to the substantial PG dimer release from N. lactamica ATCC 23970 (Fig. 3A).

Fig 9.

hNOD1 and hNOD2 activation by supernatants from different Neisseria spp. Supernatants from N. mucosa, N. lactamica (A and B), and ampG mutants of N. mucosa (C and D) induced hNOD1 (A and C) and hNOD2 (B and D) activation in HEK293 reporter cells overexpressing NOD1 or NOD2. Supernatant from an ampG mutant of N. mucosa induced a larger hNOD1 response compared to wild type. Supernatant from N. lactamica ATCC23970 induced the largest hNOD2 response of all supernatant treatment samples. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05.

Since mutation of ampG increases the amount of PG monomers released, and tripeptide monomers are known agonists of hNOD1, we hypothesized that supernatant from ampG mutants of N. mucosa would induce higher levels of hNOD1 activation compared to WT. As expected, supernatant from the ampG mutant activated hNOD1, but not hNOD2, to a greater degree compared to that of the WT parent (Fig. 9C and D). Thus, we conclude that N. mucosa and N. lactamica release hNOD-activating PG fragments and that PG recycling modulates the amount of hNOD1 agonists released by the bacteria.

PG fragments released by N. musculi stimulate mNOD1 activation in HEK293 reporter cells

Similar to hNOD1 expressed in humans, mice also express a NOD1 receptor. While hNOD1 is activated by tripeptide monomer and tripeptides, mNOD1 is activated by tetrapeptide monomer and tetrapeptides (Fig. 1B) (42). mNOD1 activation in HEK293 reporter cells was analyzed for ampG and ldcA mutant N. musculi strains (Fig. 10). Mutation of ampG in N. musculi resulted in mNOD1 activation that was not statistically significantly different from that seen with the WT parent. We mutated ldcA in N. musculi since LdcA is the enzyme which converts tetrapeptides into tripeptides in the periplasm (53). Since free tetrapeptides and tetrapeptide monomers are the mNOD1 agonists, and tripeptides versions of those molecules are poor stimulatory molecules for mNOD1, the mutation would make all the released PG monomers and free peptides into mNOD1 agonists. Supernatant from the ldcA mutant stimulated mNOD1 to a much higher degree than WT or ampG supernatants. We created a genetic construct for expression of genes of interest at a neutral site on the N. musculi chromosome, and we used this construct to overexpress ldcA. Overexpression of ldcA in N. musculi resulted in a background level of mNOD1 stimulation (Fig. 10).

Fig 10.

mNOD1 activation by supernatants from N. musculi used to treat HEK-293 cells overexpressing mNOD1. Supernatants from N. musculi WT, ampG or ldcA mutants, or a strain overexpressing ldcA were used. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Due to the role of PG monomers in causing damage to mucosal epithelium by inducing death and sloughing of ciliated cells during N. gonorrhoeae and Bordetella pertussis infections, we hypothesized that nonpathogenic Neisseria would release only small amounts of inflammatory PG fragments. The first characterization of PG fragments released by N. mucosa, performed as quantitative fragment release in comparison to N. gonorrhoeae, showed that this species releases lower levels of proinflammatory PG monomers compared to N. gonorrhoeae and no PG dimers (16). It was logical to infer that the reduced PG monomer release by N. mucosa means that nonpathogenic Neisseria spp. are less inflammatory compared to N. gonorrhoeae. This inference is supported by the observation that human-associated, nonpathogenic Neisseria spp. induce lower Toll-like receptor 4 responses compared to N. gonorrhoeae and N. meningitidis due to differences in lipooligosaccharide modification (54).

As we continued to investigate PG fragment release by more strains of human- and animal-associated Neisseria, it became clear that the situation is not as simple as we initially hypothesized. There are both interspecies and intraspecies variations in PG fragment release patterns. N. mucosa and macaque isolate AP312 did not release PG dimers, while N. lactamica, N. musculi, and macaque isolate AP678 released PG dimers. The two strains of N. lactamica evaluated showed differences in the relative amounts of PG monomer and PG peptides released (Fig. 3). Labeling of N. mucosa with [3H]-DAP revealed that, although N. mucosa released less PG monomer compared to N. gonorrhoeae, N. mucosa released more PG-derived peptides that might also activate hNOD1 (Fig. 2). N. meningitidis, which is more commonly found as a colonizer of the nasopharyngeal space, despite its ability to cause invasive disease, also releases less PG monomer and more PG peptides compared to N. gonorrhoeae (19, 40).

The two strains of N. lactamica used in the study displayed differences in the relative amounts of PG monomer and PG peptides released, partly due to differences in the efficiency of PG recycling. Such intraspecies variation in PG monomer release has been previously observed with two different isolates of N. meningitidis that have polymorphisms at AmpG residues 398 and 402 (16). We identified another AmpG residue (residue 272) capable of modulating PG recycling efficiency and indirectly controlling the amount of PG monomer released. AmpG residue 272 is a threonine in N. lactamica ATCC 49142 and an alanine in N. lactamica ATCC 23970, and WT N. gonorrhoeae and WT N. meningitidis. This finding suggests that different species of Neisseria independently evolved strategies to fine-tune the amount of PG fragments released. Examination of 1119 N. lactamica sequences available in public databases found that T272 in AmpG is present in 11.5% of strains. So, only a minority of N. lactamica strains are predicted to release larger amounts of PG fragments. Information about carrier state or disease in the people providing these isolates was not available, and thus it is not known if the amino acid substitution is more associated with disease isolates. It is possible that alterations to PG fragment release would allow strains to colonize different body sites more effectively.

Through hNOD1 and hNOD2 activation, we were able to determine that despite the nonpathogenic nature of human-associated Neisseria commensals, NOD activation was not lower in these species compared with N. gonorrhoeae. In fact, hNOD2 activation was higher in N. lactamica ATCC 23970 than in the pathogenic N. gonorrhoeae. Therefore, PG fragment release in substantial amounts does not make commensal Neisseria pathogens during nasopharyngeal colonization. Further research into the differences between NOD responses in the different niches infected by Neisseria may lead to a better understanding of these responses.

The recent establishment of macaque and mice-associated Neisseria as model organisms provide avenues for studying aspects of Neisseria colonization and infection in their cognate host organisms (6, 7, 13). One caveat of using mice as a model organism for understanding PG fragment responses in humans is that the murine NOD1 detects tetrapeptide monomers instead of tripeptide monomers like the human NOD1 (42). Still, our findings indicate that both macaque isolates and N. musculi release PG monomers, and that macaque isolate AP312 and N. musculi recycle PG fragments liberated during turnover (Fig. 6 and 7). Our ability to mutate genes in macaque isolate AP312 and N. musculi provides us with tools to vary the amounts and types of PG fragments that the host organism is exposed to and to study the corresponding host response. Future studies in these models will allow us to better understand the roles of PG fragments in Neisseria infection and to discern factors that distinguish a pathogen from a nonpathogen.

Contributor Information

Joseph P. Dillard, Email: jpdillard@wisc.edu.

Kimberly A. Kline, Universite de Geneve, Geneva, Switzerland

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.00004-24.

AmpG sequence alignment, sequence conservation, and predicted structures.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Liu G, Tang CM, Exley RM. 2015. Non-pathogenic Neisseria: members of an abundant, multi-habitat, diverse genus. Microbiology (Reading) 161:1297–1312. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stephens DS, Greenwood B, Brandtzaeg P. 2007. Epidemic meningitis, meningococcaemia, and Neisseria meningitidis. Lancet 369:2196–2210. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61016-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE. 2005. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol 43:5721–5732. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burcham ZM, Garneau NL, Comstock SS, Tucker RM, Knight R, Metcalf JL, Taste Lab Citizen S, Genetics of Taste Lab Citizen Scientists . 2020. Patterns of oral microbiota diversity in adults and children: a crowdsourced population study. Sci Rep 10:2133. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59016-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bogaert D, Keijser B, Huse S, Rossen J, Veenhoven R, van Gils E, Bruin J, Montijn R, Bonten M, Sanders E. 2011. Variability and diversity of nasopharyngeal microbiota in children: a metagenomic analysis. PLoS One 6:e17035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weyand NJ, Ma M, Phifer-Rixey M, Taku NA, Rendón MA, Hockenberry AM, Kim WJ, Agellon AB, Biais N, Suzuki TA, Goodyer-Sait L, Harrison OB, Bratcher HB, Nachman MW, Maiden MCJ, So M. 2016. Isolation and characterization of Neisseria musculi sp. nov., from the wild house mouse. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 66:3585–3593. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weyand NJ, Wertheimer AM, Hobbs TR, Sisko JL, Taku NA, Gregston LD, Clary S, Higashi DL, Biais N, Brown LM, Planer SL, Legasse AW, Axthelm MK, Wong SW, So M. 2013. Neisseria infection of rhesus macaques as a model to study colonization, transmission, persistence, and horizontal gene transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:3059–3064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217420110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gold R, Goldschneider I, Lepow ML, Draper TF, Randolph M. 1978. Carriage of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria lactamica in infants and children. J Infect Dis 137:112–121. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.2.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oliver KJ, Reddin KM, Bracegirdle P, Hudson MJ, Borrow R, Feavers IM, Robinson A, Cartwright K, Gorringe AR. 2002. Neisseria lactamica protects against experimental meningococcal infection. Infect Immun 70:3621–3626. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3621-3626.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deasy AM, Guccione E, Dale AP, Andrews N, Evans CM, Bennett JS, Bratcher HB, Maiden MCJ, Gorringe AR, Read RC. 2015. Nasal inoculation of the commensal Neisseria lactamica inhibits carriage of Neisseria meningitidis by young adults: a controlled human infection study. Clin Infect Dis 60:1512–1520. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Donati C, Zolfo M, Albanese D, Tin Truong D, Asnicar F, Iebba V, Cavalieri D, Jousson O, De Filippo C, Huttenhower C, Segata N. 2016. Uncovering oral Neisseria tropism and persistence using metagenomic sequencing. Nat Microbiol 1:16070. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Richards VP, Alvarez AJ, Luce AR, Bedenbaugh M, Mitchell ML, Burne RA, Nascimento MM. 2017. Microbiomes of site-specific dental plaques from children with different caries status. Infect Immun 85:e00106-17. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00106-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma M, Powell DA, Weyand NJ, Rhodes KA, Rendón MA, Frelinger JA, So M. 2018. A natural mouse model for Neisseria colonization. Infect Immun 86:e00839-17. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00839-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson AP. 1983. The pathogenic potential of commensal species of Neisseria. J Clin Pathol 36:213–223. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.2.213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marri PR, Paniscus M, Weyand NJ, Rendón MA, Calton CM, Hernández DR, Higashi DL, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Rounsley SD, So M. 2010. Genome sequencing reveals widespread virulence gene exchange among human Neisseria species. PLoS One 5:e11835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chan JM, Dillard JP. 2016. Neisseria gonorrhoeae crippled its peptidoglycan fragment permease to facilitate toxic peptidoglycan monomer release. J Bacteriol 198:3029–3040. doi: 10.1128/JB.00437-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park JT, Uehara T. 2008. How bacteria consume their own exoskeletons (turnover and recycling of cell wall peptidoglycan). Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 72:211–227. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00027-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Melly MA, McGee ZA, Rosenthal RS. 1984. Ability of monomeric peptidoglycan fragments from Neisseria gonorrhoeae to damage human fallopian-tube mucosa. J Infect Dis 149:378–386. doi: 10.1093/infdis/149.3.378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Woodhams KL, Chan JM, Lenz JD, Hackett KT, Dillard JP. 2013. Peptidoglycan fragment release from Neisseria meningitidis. Infect Immun 81:3490–3498. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00279-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heiss LN, Moser SA, Unanue ER, Goldman WE. 1993. Interleukin-1 is linked to the respiratory epithelial cytopathology of pertussis. Infect Immun 61:3123–3128. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3123-3128.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kessie DK, Lodes N, Oberwinkler H, Goldman WE, Walles T, Steinke M, Gross R. 2020. Activity of tracheal cytotoxin of Bordetella pertussis in a human tracheobronchial 3D tissue model. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:614994. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.614994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Carneiro LAM, Antignac A, Jéhanno M, Viala J, Tedin K, Taha M-K, Labigne A, Zähringer U, Coyle AJ, DiStefano PS, Bertin J, Sansonetti PJ, Philpott DJ. 2003. Nod1 detects a unique muropeptide from gram-negative bacterial peptidoglycan. Science 300:1584–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1084677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Viala J, Chamaillard M, Labigne A, Thomas G, Philpott DJ, Sansonetti PJ. 2003. Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. J Biol Chem 278:8869–8872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200651200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morse SA, Bartenstein L. 1974. Factors affecting autolysis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 145:1418–1421. doi: 10.3181/00379727-145-38025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kellogg DS, Jr, Peacock WL, Deacon WE, Brown L, Pircle DI. 1963. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. I. Virulence genetically linked to clonal variation. J Bacteriol 85:1274–1279. doi: 10.1128/jb.85.6.1274-1279.1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Swanson J, Kraus SJ, Gotschlich EC. 1971. Studies on gonococcus infection I. Pili and zones of adhesion: their relation to gonococccal growth patterns. J Exp Med 134:886–906. doi: 10.1084/jem.134.4.886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garcia DL, Dillard JP. 2008. Mutations in ampG or ampD affect peptidoglycan fragment release from Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Bacteriol 190:3799–3807. doi: 10.1128/JB.01194-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hamilton HL, Schwartz KJ, Dillard JP. 2001. Insertion-duplication mutagenesis of Neisseria: use in characterization of DNA transfer genes in the gonococcal genetic Island. J Bacteriol 183:4718–4726. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.16.4718-4726.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Woodhams KL, Benet ZL, Blonsky SE, Hackett KT, Dillard JP. 2012. Prevalence and detailed mapping of the gonococcal genetic Island in Neisseria meningitidis. J Bacteriol 194:2275–2285. doi: 10.1128/JB.00094-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Seifert HS, Chen EY, So M, Heffron F. 1986. Shuttle mutagenesis: a method of transposon mutagenesis for Saccharomyces cervisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83:735–739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.3.735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dillard JP. 2011. Genetic manipulation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Curr Protoc Microbiol 4:Unit4A.2. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc04a02s23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jolley KA, Bray JE, Maiden MCJ. 2018. Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res 3:124. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sayers EW, Bolton EE, Brister JR, Canese K, Chan J, Comeau DC, Connor R, Funk K, Kelly C, Kim S, Madej T, Marchler-Bauer A, Lanczycki C, Lathrop S, Lu Z, Thibaud-Nissen F, Murphy T, Phan L, Skripchenko Y, Tse T, Wang J, Williams R, Trawick BW, Pruitt KD, Sherry ST. 2022. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res 50:D20–D26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Madeira F, Pearce M, Tivey ARN, Basutkar P, Lee J, Edbali O, Madhusoodanan N, Kolesnikov A, Lopez R. 2022. Search and sequence analysis tools services from EMBL-EBI in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res 50:W276–W279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ. 2009. Jalview version 2--a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Meng EC, Goddard TD, Pettersen EF, Couch GS, Pearson ZJ, Morris JH, Ferrin TE. 2023. UCSF chimerax: tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci 32:e4792. doi: 10.1002/pro.4792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mirdita M, Schütze K, Moriwaki Y, Heo L, Ovchinnikov S, Steinegger M. 2022. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat Methods 19:679–682. doi: 10.1038/s41592-022-01488-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sinha RK, Rosenthal RS. 1980. Release of soluble peptidoglycan from growing gonococci: demonstration of anhydro-muramyl-containing fragments. Infect Immun 29:914–925. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.3.914-925.1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chan JM, Dillard JP. 2017. Attention seeker: production, modification, and release of inflammatory peptidoglycan fragments in Neisseria species. J Bacteriol 199:e00354-17. doi: 10.1128/JB.00354-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chan JM, Hackett KT, Woodhams KL, Schaub RE, Dillard JP. 2022. The AmiC/NlpD pathway dominates peptidoglycan breakdown in Neisseria meningitidis and affects cell separation, NOD1 agonist production, and infection. Infect Immun 90:e0048521. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00485-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Knilans KJ, Hackett KT, Anderson JE, Weng C, Dillard JP, Duncan JA. 2017. Neisseria gonorrhoeae lytic transglycosylases LtgA and LtgD reduce host innate immune signaling through TLR2 and NOD2. ACS Infect Dis 3:624–633. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.6b00088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Magalhaes JG, Philpott DJ, Nahori M-A, Jéhanno M, Fritz J, Le Bourhis L, Viala J, Hugot J-P, Giovannini M, Bertin J, Lepoivre M, Mengin-Lecreulx D, Sansonetti PJ, Girardin SE. 2005. Murine Nod1 but not its human orthologue mediates innate immune detection of tracheal cytotoxin. EMBO Rep 6:1201–1207. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schaub RE, Perez-Medina KM, Hackett KT, Garcia DL, Dillard JP. 2019. Neisseria gonorrhoeae PBP3 and PBP4 facilitate Nod1 agonist peptidoglycan fragment release and survival in stationary phase. Infect Immun 87:e00833–18w. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00833-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jacobs C, Huang LJ, Bartowsky E, Normark S, Park JT. 1994. Bacterial cell wall recycling provides cytosolic muropeptides as effectors for beta-lactamase induction. EMBO J 13:4684–4694. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06792.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Drew D, North RA, Nagarathinam K, Tanabe M. 2021. Structures and general transport mechanisms by the major facilitator superfamily (MFS). Chem Rev 121:5289–5335. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cheng Q, Park JT. 2002. Substrate specificiy of the AmpG permease required for recycling of cell wall anhydro-muropeptides. J Bacteriol 184:6434–6436. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.23.6434-6436.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chamaillard M, Hashimoto M, Horie Y, Masumoto J, Qiu S, Saab L, Ogura Y, Kawasaki A, Fukase K, Kusumoto S, Valvano MA, Foster SJ, Mak TW, Nuñez G, Inohara N. 2003. An essential role for NOD1 in host recognition of bacterial peptidoglycan containing diaminopimelic acid. Nat Immunol 4:702–707. doi: 10.1038/ni945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Philpott DJ, Sorbara MT, Robertson SJ, Croitoru K, Girardin SE. 2014. NOD proteins: regulators of inflammation in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 14:9–23. doi: 10.1038/nri3565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Girardin SE, Travassos LH, Hervé M, Blanot D, Boneca IG, Philpott DJ, Sansonetti PJ, Mengin-Lecreulx D. 2003. Peptidoglycan molecular requirements allowing detection by Nod1 and Nod2. J Biol Chem 278:41702–41708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307198200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Inohara N, Ogura Y, Fontalba A, Gutierrez O, Pons F, Crespo J, Fukase K, Inamura S, Kusumoto S, Hashimoto M, Foster SJ, Moran AP, Fernandez-Luna JL, Nuñez G. 2003. Host recognition of bacterial muramyl dipeptide mediated through NOD2. J Biol Chem 278:5509–5512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200673200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Höltje J-V, Mirelman D, Sharon N, Schwarz U. 1975. Novel type of murein transglycosylase in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 124:1067–1076. doi: 10.1128/jb.124.3.1067-1076.1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schaub RE, Chan YA, Lee M, Hesek D, Mobashery S, Dillard JP. 2016. Lytic transglycosylases LtgA and LtgD perform distinct roles in remodeling, recycling and releasing peptidoglycan in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol 102:865–881. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lenz JD, Hackett KT, Dillard JP. 2017. A single dual-function enzyme controls the production of inflammatory NOD agonist peptidoglycan fragments by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. mBio 8:e01464-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01464-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. John CM, Liu M, Phillips NJ, Yang Z, Funk CR, Zimmerman LI, Griffiss JM, Stein DC, Jarvis GA. 2012. Lack of lipid A pyrophosphorylation and functional lptA reduces inflammation by Neisseria commensals. Infect Immun 80:4014–4026. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00506-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

AmpG sequence alignment, sequence conservation, and predicted structures.