INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy is a time of rapid transition involving many physiological, psychological, and social changes that can be associated with stress and anxiety (Anniverno et al., 2013). Anxiety during pregnancy is linked to various adverse perinatal outcomes, including preterm birth, low birthweight, small-for-gestational age birth (Grigoriadis et al., 2018), poor mother-child bonding (Dubber et al., 2015), low exclusive breastfeeding rates (Hoff et al., 2019; Horsley et al., 2019), and risk of behavioral and emotional problems in the child (Korja et al., 2017; O’Connor et al., 2002; Van den Bergh et al., 2005). Approximately one in every five pregnant women meet diagnostic criteria for at least one anxiety disorder during their pregnancy or in the postpartum period(Dennis et al., 2017; Fawcett et al., 2019). Prevalence is higher in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as Pakistan(Fisher et al., 2012), where the rate maternal anxiety is estimated to range from 35% to 49%(Niaz et al., 2004; Waqas et al., 2015), and this is exacerbated by a scarcity of mental health services(Demyttenaere et al., 2004; Patel et al., 2010; Saxena et al., 2007). Risk factors for anxiety in Pakistan include social and relationship stressors such as lack of social support, gender inequalities, and intimate partner violence during pregnancy(Waqas et al., 2015).

Social support during the perinatal period is strongly protective against common mental disorders (CMDs) in mothers(Surkan et al., 2006), whereas women who experience social isolation or loneliness are more likely to develop anxiety and depression(Lee et al., 2007; Littleton et al., 2007). In addition to increasing risk of anxiety before and after pregnancy, perceived social isolation is associated with pregnancy complications and preterm birth(Elsenbruch et al., 2007; Littleton et al., 2007; Surkan et al., 2020). Evidence on the effectiveness of providing social support as a preventive intervention to reduce preterm birth or maternal depression is mixed(Dennis and Hodnett, 2007; Hetherington et al., 2015; Hodnett and Fredericks, 2003). This fact might be explained by a failure to account for the sociocultural, context-specific aspects of support during pregnancy(Edmonds et al., 2011b), especially given the limited qualitative research available on pregnant women’s subjective experience of social support in the context of mental distress(McLeish and Redshaw, 2017; Rosario et al., 2017).

Pregnant women remain underrepresented in the literature on loneliness or perceived social isolation, a close corollary of low social support, despite there being extensive research on the elderly and other vulnerable groups across the lifespan(Cornwell and Waite, 2009; Kent-Marvick et al., 2020; Luoma et al., 2019). Perceived social isolation is a significant risk factor for anxiety and depression in pregnant women, including in LMICs(Cheng et al., 2016; Emmanuel and St John, 2010; Waqas et al., 2015). This may be due in part to absence of social support to help facilitate coping or buffering effects of stress during pregnancy(Jonsdottir et al., 2017; Nylen et al., 2013; Zachariah and health, 2009), but perceived isolation can also act as a direct source of stress that exacerbates social disconnectedness and has negative consequences on cognitions, behaviors, and emotions in a self-reinforcing loop(Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010; Luoma et al., 2019; Santini et al., 2020).

No prior study, to our knowledge, has examined perceived social isolation in relation to prenatal anxiety in South Asia. Given the complex, context-specific nature of these phenomenon and that there little known about this relationship, qualitative investigation is a crucial step toward addressing this gap in the literature(Adams et al., 2006; Agadjanian, 2002; Edmonds et al., 2011b; Finfgeld‐Connett, 2005). Our study aims to examine the role of perceived social isolation in the experience of prenatal anxiety among women in Pakistan from the perspective of symptomatic pregnant women and prenatal care providers.

METHODS

This study draws on semi-structured interviews that were conducted with 19 pregnant patients and 10 female providers at the Obstetrics/Gynecology Department of the Holy Family Hospital, a teaching hospital at Rawalpindi Medical University in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Holy Family Hospital serves a catchment area of over 7 million people and provides free or low-cost medical services. Interview data were collected between September 2017 and August 2018 to inform the development of a preventive mental health intervention for anxiety in pregnancy (Atif et al., 2019; Surkan et al., 2020). Interview topics included sources and manifestations of anxiety during pregnancy, common psychosocial stressors, interpersonal relationships, and forms of coping and social support for expectant mothers. The study procedures received ethical approval from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the IRB of the Human Development Research Foundation.

Women were eligible to participate in interviews if they had a score of at least eight or higher on an Urdu version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), which indicates a respondent is at least “at risk” of anxiety(Dodani and Zuberi, 2000; Mumford et al., 1991; Qadir et al., 2013; Zigmond and Snaith, 1983). Participants also had to live within 20 km of the Holy Family Hospital and screen negative for clinical depression or other serious medical conditions. Screening for major depressive disorder or suicidal ideation was conducted using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID)(First et al., 1997). Participants who were diagnosed with major depression, suicidal ideation, or self-reported psychiatric disorders (past or present) or were under psychiatric care were deemed ineligible to participate. Purposive sampling was used for provider recruitment to ensure inclusion of a diverse group of antenatal providers (i.e., physicians, nurses, and midwives) (Miles and Huberman, 1994).

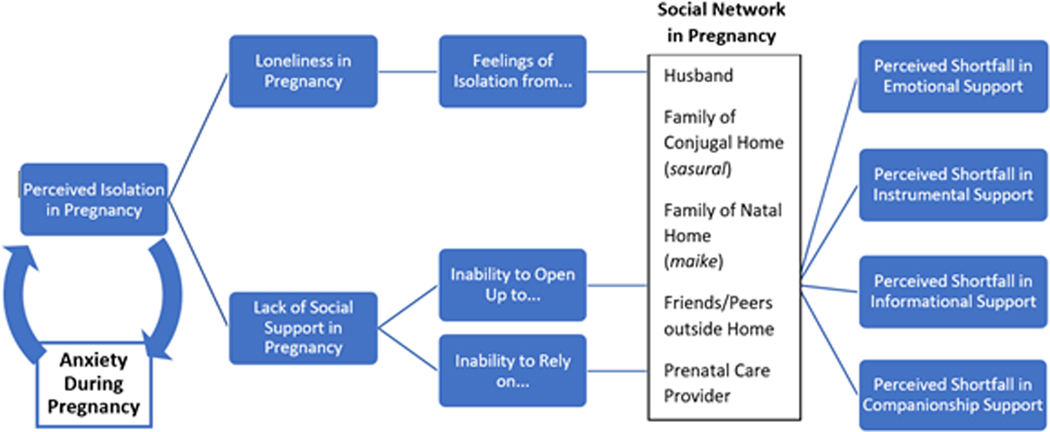

The audio recorded interviews were transcribed and translated to English before being analyzed thematically following the methods of Braun and Clarke (Braun and Clarke, 2006). Both inductive codes—derived from common forms of social support described by participants as available, unavailable, and/or normative in Pakistan—and deductive themes adapted from social support theory and constructs of perceived social isolation were applied to the transcripts. First, results of independent open coding (Saldaña, 2021) by two bilingual members of the study team were reviewed for relevance to social support and anxiety in pregnancy. Refined codes were then organized according to social support typology as described by House (1981) and a thematic framework adapted for pregnancy from conceptualizations of anxiety in relation to perceived social isolation (Figure 1), or the subjective experience of shortfalls in social network functioning and social resources, including the absence of support(Cornwell and Waite, 2009; House, 1981; Santini et al., 2020). Finally, data matrices were used to visualize the distribution of interview excerpts across sources of support (e.g., husband, mother, etc.), types of support (e.g., emotional, instrumental, etc.), and perceived status of support (e.g., available, unavailable, etc.). Analytic memos, close reading and comparison of excerpts, examination of data matrices, and periodic meetings to reconcile and refine code categorizations all contributed toward obtaining the final analysis by thematic analysis.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework for the Relationship between Anxiety, Social Support, and Perceived Isolation in Pregnancy, integrating concepts from House (1981), Cornwell and Waite (2009), and Santini et al (2020).

RESULTS

The sample included 19 pregnant women and 10 healthcare providers. Pregnant women participants were 18 to 37 years old (mean age of 26 years) and had between five and eleven years of education. Perinatal providers included obstetric and gynecologic physicians (n=4) and non-physician providers such as nurses and midwives (n=6) with ages from 24 to 55 years. The demographic profiles for the study sample of pregnant women and prenatal providers are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic Profile of Participants: Pregnant Women (n = 19)

| Participant | Age* (years) | Years of Schooling | Family Structure | Number/Gender of Living Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 20–24 | 10 | Nuclear | 1 (girl) |

| M2 | 25–29 | 12 | Nuclear | 3 (1 boy, 2 girls) |

| M3 | 20–24 | 12 | Joint | 0 |

| M4 | 30–34 | 12 | Joint | 2 (girls) |

| M5 | 25–29 | 10 | Joint | 0 |

| M6 | 30–34 | 10 | Nuclear | 0 |

| M7 | 20–24 | 5 | Joint | 2 (1 boy, 1 girl) |

| M8 | <20 | 5 | Joint | 0 |

| M9 | 20–24 | 10 | Joint | 2 (girls) |

| M10 | 20–24 | 5 | Joint | 2 (boys) |

| M11 | 20–24 | 14 | Joint | 0 |

| M12 | 20–24 | 6 | Joint | 0 |

| M13 | ≥34 | 10 | Joint | 1 (boy) |

| M14 | 20–24 | 5 | Nuclear | 2 (1 boy, 1 girl) |

| M15 | 25–29 | 16 | Joint | 1 (girl) |

| M16 | 30–34 | 14 | Joint | 0 |

| M17 | 20–24 | 12 | Joint | 0 |

| M18 | 30–34 | 14 | Nuclear | 4 (3 girls, 1 boy) |

| M19 | 25–29 | 10 | Joint | 0 |

Age ranges are presented to preserve participant anonymity

Table 2.

Demographic Profile of Participants: Providers (n = 10)

| Participant | Age* (years) | Provider Category | Years of Work Experience* |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | ≥50 | OB/GYN Physician | 28 |

| P2 | 40–49 | OB/GYN Physician | 15–19 |

| P3 | ≥50 | OB/GYN Physician | 25–29 |

| P4 | ≥50 | OB/GYN Physician | 30–34 |

| P5 | 30–39 | Nurse/Midwife | 15–19 |

| P6 | 30–39 | Nurse/Midwife | 5–9 |

| P7 | 20–29 | Nurse/Midwife | 5–9 |

| P8 | 20–29 | Nurse/Midwife | 0–4 |

| P9 | 40–49 | Nurse/Midwife | 20–24 |

| P10 | 30–39 | Nurse/Midwife | 5–9 |

Ranges and the merging of nurse and midwife for the provider categories presented to preserve participant anonymity

Findings from both groups of participants were organized by source of support as well as divided into four sub-themes, three of which were derived from the conceptual framework of perceived social isolation (i.e., Feelings of Isolation, Ability to Open Up, Ability to Rely On)(Cornwell and Waite, 2009) and one emergent topic about the connections between social support and prenatal anxiety symptoms as well as general health and wellbeing among pregnant women in our sample. Findings and interview excerpts are presented by thematic category, corresponding to the thematic coding scheme used in our qualitative analysis, while key distributional characteristics of the data across type of support and perceived status of support are included where relevant.

3.1. Feelings of Isolation

3.1.1. Isolation and Conjugal/Natal Family Support

Among the most important factors contributing to women’s experiences of anxiety during pregnancy was the feeling that they lacked close companionship, were left out, or were otherwise isolated from others, even those closest to them such as family. Perceived absence of sympathy, support, and understanding from family was described as a key source or exacerbator of anxiety symptoms. Women described feeling especially unsupported in the context of the conjugal or marital home (i.e., with in-laws) and the sense that there was no one available with whom to share stressors or discuss problems during their pregnancy (Table 3, Quote 1).

Table 3.

Excerpts about feelings of isolation and prenatal anxiety

| Quote # | Type* | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Theme/Source: Isolation and Conjugal/Natal Family Support | ||

| 1 | PW | Then there are problems with those at home. I wonder, what will happen? How will this happen? What can I do? I wish there were someone at home I could talk to. Those whom I have to talk to, I can’t talk to. (M13) |

| 2 | HP | There are certain women who have been ignored at home by their family. As you know, in-laws are not very caring [of daughters-in-law] in our society. (P5) |

| 3 | PW | I live upstairs, so I am busy with my household chores. They all live in the lower portion. I also sew others’ clothes, so I don’t have much time to share [with my sister- and mother-in-law]. (M7) |

| 4 | HP | The woman who is going through pregnancy is fighting a private battle for herself and her child. […] She wants someone to take care of her, to look after her and help her. (P5) |

| 5 | PW | I have been at my mother’s home for the last six months because it’s my first baby so she wants me to stay with her […] They are all very supportive. (M19) |

| 6 | HP | Some women are not allowed to step outside their houses, [and] no one knows at home that she has come to visit [a provider]. (P2) |

| 7 | PW | Before, it was that… (hesitates, looks around) Before, it was like my in-laws had prepared for a son. Everything was bought for a son. Everything. So, when I was in the hospital, [in a low voice] they abandoned me. (M1) |

| Theme/Source: Isolation and Spousal Support | ||

| 8 | PW | When my husband was here, I had no tension, but now I am alone and I feel more stress. Sometimes I become unconscious. No one was there to watch out for me. That’s why I felt it was very difficult. (M13) |

| 9 | PW | A woman depends on her husband because she leaves her mother’s home. If her husband is a nice person, then even if her in-laws are not good, time will pass. If her husband and in-laws are not good to her, then a woman cannot live. (M10) |

| 10 | PW | When I talk about visiting my sisters, he gets down on hearing this. If I were allowed to visit my siblings’ home, then there wouldn’t be any issue. (M11) |

| 11 | PW | My mother-in-law asked him [my husband] why he was happy as he was having a daughter, to which my husband replied that he is thankful to Allah [God] for granting him a child. […] Women nowadays can’t always handle such criticism. They need someone to talk to. (M18) |

| Theme/Source: Isolation and Peer Support | ||

| 12 | PW | I would get back pain. Otherwise, mentally, I did not like having to quit my former activities of going out with my friends and spending time with them. (M11) |

| 13 | HP | It’s very important [that] some people keep good relations with their friends. Some people depend on their neighbors a lot [for support]. (P2) |

Participant type: PW= Pregnant Woman; HP = Healthcare Provider

Feelings of isolation were not limited to women living apart from in-laws. Even among those women living in joint families—and thus in frequent contact and interaction with an extended family network—many endorsed feelings of loneliness or absence of support. The phenomenon of perceived isolation during pregnancy despite being situated in a large, connected family network was also validated by providers (Table 3, Quote 2). Participants frequently drew distinctions between the level of social support normatively expected from family of the conjugal home versus the natal home. One physician described it as a “deep-rooted concept in our society” that in-laws provide less care or support for a woman than her parents would during pregnancy (P1). Moreover, based on data matrices distributions, the vast majority of instances where pregnant women mentioned feelings of isolation were about unavailability of emotional or companionship support from family members.

A pregnant woman in Pakistan, according to participants, is still considered responsible for most of the domestic work generally expected of married women such as cooking, cleaning, and childcare. A few women highlighted the burden of such chores as a source of isolation, since the time one has available to confide in others becomes limited after marriage, even for those who receive some family assistance with household tasks (Table 3, Quote 3). Prenatal care providers also described how lack of assistance in household tasks can contribute to pregnant women’s feelings of isolation and anxiety, highlighting that concern demonstrated by family would provide comfort and contribute to a sense of companionship during this vulnerable period (Table 3, Quote 4).

Calls or visits to a woman’s natal home was an important mitigator of isolation and anxiety during pregnancy. One mother described visiting her mother’s home “twice or even thrice every month” of her pregnancy for companionship (M3). Women described time spent at their natal homes as a key form of support during the vulnerable and challenging period of pregnancy. (Table 3, Quote 5)

Many providers described circumscribed mobility for pregnant women due to families requiring them to travel accompanied by their mothers-in-law or husbands. While some women viewed accompanied visits to the hospital as a form of instrumental support, most gave accounts of such barriers furthering their isolation during pregnancy by preventing them from obtaining care or seeking help (Table 3, Quote 6). Citing an extreme example, one provider described a woman who faced resistance from her in-laws against attending prenatal visits and suffered “some domestic violence [and] later on, the patient came to us bleeding” (P2). Women described facing more strict restrictions against travel outside the home for distant trips during pregnancy when they were perceived to be physically vulnerable, and this limited their ability to visit the natal home, see friends, or otherwise access their social network.

One prominent cause of anxiety for women was male child preference among family, a cultural phenomenon observed across various societies including Pakistan for reasons such as carrying family names forward, inheriting a family business or trade, and being a source of financial support to parents in old age. The role of male child preference in expectant women’s isolation and anxieties was exemplified by one mother who felt abandoned by family after she delivered a baby girl. Her conjugal family, she reported, refused to visit her at the hospital after learning she had not borne a son (Table 3, Quote 7). Providers also mentioned male child preference as one of the main sources of stress or anxiety for Pakistani women during pregnancy, particularly during the third trimester, due to fears of how in-laws might react or give differential treatment and support to the mother if a female child were born.

3.1.2. Isolation and Spousal Support

Within a woman’s family, the husband was considered by participants to be especially important to receiving social support during pregnancy and alleviating feelings of isolation. Many women described unavailability of spousal support as “the biggest worry in life” and among the worst exacerbators of prenatal anxiety symptoms (M15). This included those whose husbands worked overseas to provide for the family. Even in joint family contexts, the husband was portrayed as an essential companion, without whom the woman was at risk of isolation or neglect. (Table 3, Quote 8)

According to some women and providers, the importance of spousal support to women’s emotional wellbeing during pregnancy was heightened in joint family contexts, where husbands’ cooperation may be critical to ensuring good treatment by in-laws or, in cases of poor treatment, giving her the strength to cope (Table 3, Quote 9). An unsupportive husband, on the other hand, could serve as a source of isolation and barrier to accessing support. One manifestation of this endorsed by a few women was their husbands’ resistance to allow them to visit their natal home, whether generally or during pregnancy (Table 3, Quote 10). A husband’s permission was described as normatively required for a Pakistani woman to visit or stay at her natal home, including during pregnancy, thus representing a potential barrier against accessing this means of dispelling loneliness, escaping poor treatment by in-laws, or coping with prenatal anxiety.

For women facing pressure or isolation by in-laws on account of the child’s gender, the ability to turn to one’s husband for support was portrayed as essential to coping. Understanding from the husband served as a source of relief and companionship in the face of unhappiness or disappointment among in-laws regarding a female child (Table 3, Quote 11).

3.1.3. Isolation and Peer Support

Several women who endorsed having friends who usually provide practical or emotional support described feeling isolated from those friends due to the unique challenges of pregnancy. Among these were physical limitations or other pregnancy-related health issues that prevented them from visiting friends (Table 3, Quote 12). Companionship of friends was also described as more difficult to access due to social limits or time constraints that women faced from married life more generally, with normative expectations that “after your marriage […] you don’t have time for your friends” (M11). The importance of such support systems outside of family, however, was recognized by a few providers. (Table 3, Quote 13)

3.2. Ability to Open Up

3.2.1. Opening Up to the Conjugal and Natal Family

Beyond feelings of isolation or loneliness, a second source of prenatal anxiety related to social support was the perceived inability to open up and share problems or worries, whether related to pregnancy or to anxiety, even with those closest to them. Several women in our sample attributed their unwillingness to open up with family to a fear of being judged, misunderstood, or viewed negatively (Table 4, Quote 1). Such concerns were frequently voiced by women living in joint families. While not physically isolated, these women described an emotional atmosphere at home that discouraged open or frequent discussion of problems, especially those related to pregnancy. This perception was further elaborated by provider accounts (Table 4, Quote 2). In contrast, a few women found comfort in sharing with someone other than the mother-in-law within the conjugal home, such as a sister-in-law.

Table 4.

Excerpts about ability to open up to others and prenatal anxiety

| Quote # | Type* | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Theme/Source: Opening Up to Conjugal and Natal Family | ||

| 1 | PW | A lot of thoughts fill my mind: what will the other person think? Will she be able to understand? They could completely misinterpret it. There are a lot of issues that you can’t share with your family […] Women are scared of sharing their problems with family, thinking about how they might react. (M18) |

| 2 | HP | Sometimes they think their families are already tired of their pregnancy issues, and if they tell them about these issues, they will think the patient is constantly beset with problems. So, they don’t want to discuss such issues with family, especially not with their mother-in-law or their husband. (P6) |

| 3 | PW | If someone understands you, they may give you some valuable advice, but if they don’t [understand], then they can’t. (M5) |

| 4 | HP | She may feel afraid to talk about her concerns because many of our women’s problems are directly linked to their husbands or mothers-in-law. That is why they are mostly afraid to speak openly [at home]. (P5) |

| 5 | HP | In our society, the older household members like grandmas and other elders think if a woman becomes pregnant, it is a routine matter. If a woman shows that she is pregnant, other members of the family will tell her she is being dramatic, wants to avoid household chores, or just wants to relax. (P5) |

| Theme/Source: Opening Up to Husband | ||

| 6 | PW | Yes, I discuss things with my husband […] I get stressed and don’t know how to deal with it, then he advises me. Sometimes I am afraid to discuss things with my father and father-in-law […] and he guides me. (M15) |

| 7 | PW | I used to stay in my room and share things with my husband. He can calm me down and distract me from the situation. Sometimes if I get angry, my blood pressure gets low. (M12) |

| Theme/Source: Opening Up to Peers | ||

| 8 | PW | Yes, I am friends with a neighbor. Sometimes I share [my problems] with her, and she appreciates that I am sharing with her. (M18) |

| 9 | PW | Some people will say, ‘She has been hurt by her husband,’ so I don’t discuss it with anyone. I have a good image in the eyes of people […] I don’t want to have my image distorted. I don’t want to feel low in the eyes of other people.” (M11) |

| Theme/Source: Opening Up to Healthcare Providers | ||

| 10 | HP | They [the women] don’t share with us because, when we are overburdened with our job sometimes, we may use harsh language. Then they don’t want to discuss with us. (P8) |

Participant type: PW= Pregnant Woman; HP = Healthcare Provider

Another major barrier to opening up was a woman’s level of trust or expected level of confidentiality with members of her family. Some women felt at risk of having their problems disclosed to others “because they might discuss [your problems] with others without considering your privacy”. (M12) A woman’s ability to open up also depended on the perceived extent to which the other person could be expected to understand and respond in helpful ways (Table 4, Quote 3). A few providers confirmed the constraints on women’s ability to open up and described how women may be afraid of discussing concerns with family members who are themselves sources of her anxiety or social strain (Table 4, Quote 4).

A woman’s perceived ability to open up had important implications for her ability to cope with anxiety as well as her overall health during pregnancy according to participants. Providers suggested that a key contributor to women feeling calm and progressing well through pregnancy was having a trusted person with whom to talk. Many women, however, experienced a shortfall in available support with respect to their family heeding or affirming their expressed concerns (Table 4, Quote 5). Such family expectations for women to effectively hide or remain silent about the effects of their pregnancy, physical and psychological, was a potential barrier against women disclosing serious symptoms or opening up about their anxieties and need for assistance. Moreover, a few women were met with dismissal by families when opening up about basic facts of their pregnancy or condition.

3.2.2. Opening Up to the Husband

Spousal support was essential to the perceived availability to open up about anxiety for a majority of the women. This included not only direct listening and companionship support from the husband but also his influence on how comfortable a woman could feel opening up around her in-laws in general, since their reaction or receptiveness was perceived to be shaped by the response of the husband. When asked with whom they share their worries, many women answered either primarily or exclusively with their husband. Some mentioned appreciating and relying on the support of their husbands when opening up to other family members (Table 4, Quote 6). Forms of spousal support that encouraged women to open up included a husband’s expressing sympathy for her anxieties, distracting her attention away from negative thoughts, and offering reassurance in response to her concerns. These helped dispel fears and relieve symptoms of distress or anxiety for many women. (Table 4, Quote 7)

3.2.2. Opening Up to Peers

Despite pregnancy making it difficult for women to travel and visit with peers, a few of the women who lived near friends reported some benefit from the opportunity to open up and share concerns related to their pregnancy (Table 4, Quote 8). According to one woman, proximity in age and the intimacy of their friendships are key reasons why women may find comfort or ease in opening up with peers when possible about their anxieties or problems in pregnancy.

A major barrier to opening up with peers, however, was fear of being judged or viewed as self-absorbed. To discuss anxieties and problems with people outside their household, according to some women, would show weakness or cause others to look down on her and her family (Table 4, Quote 9)

3.3.3. Opening Up to Healthcare Providers

Beyond the barriers against accessing healthcare providers caused by family, particularly husbands and mothers-in-law, many women also endorsed feeling reluctant about opening up to providers about anxiety during pregnancy. The most common reason was a perception of providers as excessively harsh, inattentive to patient concerns, or unsympathetic to emotional and psychological distress. Such perceptions were reinforced by some providers who attributed this to the realities of their being overburdened with work and lacking the opportunity to devote sufficient time and energy to listening and responding to women facing anxieties. (Table 4, Quote 10)

3.3. Ability to Rely On

3.3.1. Relying on Conjugal and Natal Family

A third factor contributing to participants’ anxieties during pregnancy was the feeling that they could not rely on members of their family, husband, or friends or provider to receive actual support even after opening up to them. Several women expressed an inability to rely on family members for assistance with household chores during pregnancy, particularly in the context of previously described attitudes among in-laws that pregnancy should not prevent a woman from fulfilling her domestic responsibilities (Table 5, Quote 1). Among those women who did report having instrumental support in physically-demanding chores, most described this support being primarily from their sisters, sisters-in-law, or natal parents as opposed to their mother-in-law or husband (Table 5, Quote 2). Practical assistance from family during pregnancy was crucial for alleviating women’s distress and anxiety symptoms by not only reducing burdensome household tasks but also providing companionship, special attention, and an expression of concern for their wellbeing (Table 5, Quote 3).

Table 5.

Excerpts about ability to rely on others and prenatal anxiety

| Quote # | Type* | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Theme/Source: Relying on Conjugal and Natal Family | ||

| 1 | PW | They don’t help me, meaning I wash my child’s clothes myself, whether I have the health or not. I wash my own clothes […] I do all my work myself, even making bread, whether I have strength or not, whether I live or die. (M13) |

| 2 | PW | My sister has come to my home and relaxed me throughout the nine months. She tells me […] everything is alright and helps me out [with chores]. (M15) |

| 3 | PW | If a little care and concern is shown to a woman during pregnancy, that would be enough for her. If care is not provided, then I can say that I feel insecure. (M15) |

| 4 | HP | At the end, most women are worried about their family being bothered on account of them. Families have to take care of their kids and get disturbed, so in the end they become tense [and] want to be discharged as soon as possible. (P9) |

| 5 | HP | When you see such women, they look depressed. They get angry about minor issues. When we ask them why they don’t take care of themselves, they respond that their family members do not bring them to the hospital. They also say that their mothers-in-law are too strict to bring them to the hospital on time (P5). |

| 6 | HP | When they feel that the degree of care I need and the care I have a right to is not being provided, then obviously the reaction is anger, depression, and deprivation […] And those girls who stay in this state for a long period, they often will come here and easily start weeping at something, or they are not gaining weight or not properly eating their medicine […] they start experiencing intra-uterine growth restriction and such problems. (P1) |

| 7 | HP | The thing is, how much support does she have? Patients cope very well if good family support is available. (P2) |

| Theme/Source: Relying on Husband | ||

| 8 | PW | No one has helped me, they [my in-laws] just talked behind my back and tried to create problems for me. However, what matters is the support and cooperation of my husband. (M18) |

| 9 | PW | Husbands listen more to their family, including their mothers and sisters, and ignore their wives, so one must make them understand the importance of their wives’ health. (M15) |

Participant type: PW= Pregnant Woman; HP = Healthcare Provider

In contrast, instrumental support from the conjugal family often focused less on routine chores and more on occasional health-related needs that arose during pregnancy, such as caring for children when the woman felt unwell, accompanying her to prenatal care appointments, or providing pregnancy-specific dietary advice. This was especially prevalent among women who lived with sisters-in-law with pregnancy experience. According to some providers, however, women still felt reluctant or limited in their ability to rely on such assistance from family (Table 5, Quote 4). Moreover, providers indicated that mothers-in-law were often a key barrier to women accessing adequate care during their pregnancy by discouraging them from visiting health facilities. This inability to rely on family for support in response to a woman’s health needs was portrayed by providers as linked to women’s emotional and psychological distress (Table 5, Quote 5). Importantly, such perceived shortfalls in instrumental support and overall care given to women by their families contributed not only to feelings of isolation and anxiety but also, according to providers, to negative effects on the progress and outcomes of the pregnancy (Table 5, Quote 6).

Beyond practical help, encouragement and advice were key forms of social support that women described wanting or seeking from family. Faith-based reassurance was a very common response to women opening up to family elders, who would encourage the women to pray and “have faith in Allah [God]” that things would get better with patience and time (M6). Another significant factor was acknowledgement and expressions of joy from family upon receiving news of the pregnancy, especially in the case of female children due to normative expectations that “people think daughters are a burden to parents” (M18). According to most providers, presence or absence of such emotional support was connected to women’s ability to cope with anxiety (Table 5, Quote 7).

One key barrier against women feeling able to rely on family for support during their pregnancy was fear of facing judgment or criticism rather than assistance in response, even from close family. For some, this was in the form of direct criticism and blame for pregnancy-related problems, while others described facing disparagement behind their backs. This phenomenon was validated by provider accounts: “They will criticize you; they will talk behind your back” (P5). The resulting inability to rely on their family members discouraged many women from seeking help and exacerbated experiences of anxiety.

3.3.2. Relying on Husband

The importance of relying on spousal support was especially high for women who were in frequent or severe conflict with other members of the conjugal family such as their mother- or sister-in-law. When asked how they coped with anxieties during pregnancy, some women would describe talking with their husbands and receiving positive or supportive responses. Forms of spousal support included listening and expressing sympathy, providing reassurance, buying gifts, and assisting with household chores. Women described such supportive behaviors by husbands as a source of confidence and strength to cope with other stressors (Table 5, Quote 8)

While the majority of women expressed some willingness to rely on their husbands for support when facing problems or experiencing anxiety, some described limits to the extent that they could expect cooperation from their husbands. These limits were portrayed as hinging on whether the husband viewed a problem as a family conflict versus an issue with consequences for his wife’s wellbeing and child’s health (Table 5, Quote 9). According to providers, other limits to women’s ability to rely on their husband for support included circumstances of domestic violence, drug addiction, severe poverty, overseas work, or occupations that left no time for involvement in pregnancy-related care. Providers also stressed the need to revisit the policy of public hospitals in Pakistan not allowing husbands to accompany their wives into clinic appointments. The presence of husbands during the prenatal appointments, many providers argued, would help make them more aware of medical concerns and their wives’ need for support to ensure a healthy pregnancy.

DISCUSSION

For women in Pakistan facing symptoms of anxiety during pregnancy, perceived social isolation and subjective experiences of low social support represent important contextual factors that can exacerbate distress and limit available strategies for coping. Our results indicate that pregnant women, as well as the providers who care for them, perceive a number of barriers to women opening up and accessing social support for prenatal anxiety. Feelings of physical and social isolation during pregnancy are pervasive, even among women living in joint families with ostensibly larger social networks. Often fearing censure by their in-laws and peers for sharing or seeking help with pregnancy-related anxieties, women may rely on involvement by husbands or members of natal family to provide desired care and companionship. Normative expectations around pregnancy such as male gender preference in offspring, perceived immutability of wives’ domestic responsibilities, and a need for accompanied travel by women may serve as additional sources of disconnectedness and confinement in the prenatal period. According to providers, the effects of perceived social isolation and deficits in social support during pregnancy include not only worsened women’s anxiety symptoms but also reduced access to care and poorer health behaviors during pregnancy.

Our findings are consistent with prior research linking perceived social isolation to more severe symptoms of anxiety, particularly among at risk populations such as the elderly, perinatal women, and immigrants(Harrison et al., 2021; Hashimoto et al., 2011; Heinrich and Gullone, 2006; Santini et al., 2020). For example, in a longitudinal mediation analysis examining social disconnectedness among older adults, Santini et al. (2020) showed that perceived isolation was a precursor to higher levels of anxiety and depression symptoms(Santini et al., 2020). Our study points toward the possibility of similar pathways among pregnant women in Pakistan, except that the social connectedness of joint families did not appear to be protective against perceived social isolation in our qualitative results. This highlights the importance of distinguishing situational factors such as network size, time spent alone, or other quantitative measures of social contact from subjective experiences of isolation, lack of support, or perceived inadequacy of social relationships(Cornwell and Waite, 2009; Hawkley et al., 2003; McHugh et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2020). Moreover, the apparent intensification of perceived social isolation among participants precipitated by conflicts with their spouses or in-laws provides qualitative elucidation of how social strain from members of one’s network may increase loneliness despite also providing social contact, as observed in prior research on older adults(Chen and Feeley, 2014).

Results of this study, particularly those related to pregnant women’s perceived inability to rely on members of the conjugal or marital home for supportive responses to their anxieties, are closely related to the sociocultural context of Pakistan, where prior research has indicated the importance of social relationships involving husbands and in-laws to perinatal mental health and access to prenatal care(Kazi et al., 2006; Mumtaz and Salway, 2007). The present study extends previous research from Pakistan that focuses on husbands’ unsupportive or even abusive behaviors as risk factors for perinatal CMDs by also indicating their central role in providing emotional support and assurance to women who experience anxiety or perceived isolation during pregnancy(Ali et al., 2009; Karmaliani et al., 2009). This finding, supported by accounts from both pregnant women and providers, complicates traditional narratives about men lacking the needed empathy or emotional expressiveness to provide such support(Wellman and Wortley, 1990). A 2009 study from Ahmadnagar, India, and a 2011 study from Matlab, Bangladesh, both showed similar patterns of substantial emotional support and involvement by husbands during pregnancy(Edmonds et al., 2011a; Singh and Ram, 2009). Our study thus adds to existing evidence on culturally-specific opportunities to include men in social support interventions for pregnant women in South Asia. Moreover, both pregnant women and providers portrayed various forms of instrumental support at home, particularly by sisters-in-law or natal family, as not only as helpful in reducing the burden of household chores but also indicative of care and concern and thereby alleviating perceived isolation and anxiety. This finding points to the context-specific nature of social support with respect to its form and meaning, with traditional divisions between instrumental and emotional support becoming less clear in cultural contexts where open verbal exchanges are considered less desirable(Chan et al., 2001; Finfgeld‐Connett, 2005).

Limitations

There were a number of limitations of our study. Due to the potential sensitivity of topics such as pregnant women’s mental health and treatment by husbands and in-laws, participants were interviewed in private areas of the hospital to ensure confidentiality. Nonetheless, holding interviews at a healthcare facility may have resulted in underreporting of abuse and neglect, though the hospital was still considered preferable to women’s homes where fears of social repercussions would be heightened given norms of having other family members present when such encounters occur at home(Clifford et al., 1999; Husain et al., 2014). The hospital setting for our study also limited our access to pregnant women who do not utilize facility-based prenatal care, limiting the transferability of our findings to these populations. Furthermore, this research was focused on the interaction of perceived social isolation with prenatal anxiety, and further research is still needed to compare the experiences of perceived isolation presented here with those of women outside the context of pregnancy or affective disorder symptoms. The inclusion of provider, however, did allow for triangulation to enhance completeness of our investigation, while purposive sampling to capture the perspectives of a diverse group of providers enhanced the breadth of information from these interviews.

CONCLUSIONS

Findings from this study help further our understanding of the cultural and contextual factors shaping the experience of prenatal anxiety in South Asia as well as the phenomenon of perceived social isolation among pregnant women, a vulnerable group that remains underrepresented in existing literature on loneliness and isolation. Insights into how the perceived shortfalls in social support during pregnancy can contribute to and exacerbate prenatal anxiety offer to inform future research on effects of these factors on women’s health or pregnancy outcomes. They may also guide intervention development aiming to address deficits in social support as a risk factor for affective disorders in pregnancy, particularly in the sociocultural context of Pakistan. Further investigation is needed to facilitate the meaningful focus on and inclusion of social support in the prevention of perinatal CMDs and development of strategies to screen for and address perceived social isolation in pregnancy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health [grant number R01MH111859]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The authors would like to thank to the team at Holy Family Hospital and Human Development Research Foundation in Pakistan who contributed to this project. Also, we are sincerely thankful to the women who shared their experiences with us, without these we would not able to complete this research.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- Adams AM, Madhavan S, Simon D, 2006. Measuring social networks cross-culturally. Social Networks 28, 363–376. [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian V, 2002. Informal social networks and epidemic prevention in a third world context: cholera and HIV/AIDS compared. Advances in medical sociology 8, 201–222. [Google Scholar]

- Ali NS, Ali BS, Azam IS, 2009. Post partum anxiety and depression in peri-urban communities of Karachi, Pakistan: a quasi-experimental study. BMC public health 9, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anniverno R, Bramante A, Mencacci C, Durbano F, 2013. Anxiety disorders in pregnancy and the postpartum period. New iInsights into anxiety disorders. Rijeka: InTech, 259–285.

- Atif N, Nazir H, Zafar S, Chaudhri R, Atiq M, Mullany LC, Rowther A, Malik A, Surkan P, Rahman A, 2019. Development of a psychological intervention to address anxiety during pregnancy in a low-income country. Frontiers in psychiatry 10, 927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V, 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chan CW, Molassiotis A, Yam BM, Chan S, Lam CS, 2001. Traveling through the Cancer Trajectory: Social Support perceived by Womenwith Gynecological Cancer in Hong Kong. Cancer Nursing 24, 387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Feeley TH, 2014. Social support, social strain, loneliness, and well-being among older adults: An analysis of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 31, 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ER, Rifas-Shiman SL, Perkins ME, Rich-Edwards JW, Gillman MW, Wright R, Taveras E.M.J.J.o.W.s.H., 2016. The influence of antenatal partner support on pregnancy outcomes. 25, 672–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford C, Day A, Cox J, Werrett J, 1999. A cross‐cultural analysis of the use of the Edinburgh Post‐Natal Depression Scale (EPDS) in health visiting practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing 30, 655–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell EY, Waite LJ, 2009. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of health and social behavior 50, 31–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, De Girolamo G, Morosini P, 2004. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291, 2581–2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis C-L, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R.J.T.B.J.o.P., 2017. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. 210, 315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis CL, Hodnett E.D.J.C.d.o.s.r., 2007. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dodani S, Zuberi RW, 2000. Center-based prevalence of anxiety and depression in women of the northern areas of Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc 50, 138–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubber S, Reck C, Müller M, Gawlik S.J.A.o.w.s.m.h., 2015. Postpartum bonding: the role of perinatal depression, anxiety and maternal–fetal bonding during pregnancy. 18, 187–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds JK, Paul M, Sibley LM, 2011a. Type, content, and source of social support perceived by women during pregnancy: Evidence from Matlab, Bangladesh. Journal of health, population, and nutrition 29, 163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds JK, Paul M, Sibley L.M.J.J.o.h., population,, nutrition, 2011b. Type, content, and source of social support perceived by women during pregnancy: Evidence from Matlab, Bangladesh. 29, 163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsenbruch S, Benson S, Rücke M, Rose M, Dudenhausen J, Pincus-Knackstedt MK, Klapp BF, Arck P.C.J.H.r., 2007. Social support during pregnancy: effects on maternal depressive symptoms, smoking and pregnancy outcome. 22, 869–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmanuel E, St John W.J.J.o.A.N., 2010. Maternal distress: a concept analysis. 66, 2104–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett EJ, Fairbrother N, Cox ML, White IR, Fawcett JM, 2019. The Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period: A Multivariate Bayesian Meta-Analysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Finfgeld‐Connett D, 2005. Clarification of social support. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 37, 4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB, 1997. User’s guide for the Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders SCID-I: clinician version. American Psychiatric Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J, Cabral de Mello M, Patel V, Rahman A, Tran T, Holton S, Holmes W, 2012. Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90, 139–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriadis S, Graves L, Peer M, Mamisashvili L, Tomlinson G, Vigod SN, Dennis C-L, Steiner M, Brown C, Cheung A.J.T.J.o.c.p., 2018. Maternal Anxiety During Pregnancy and the Association With Adverse Perinatal Outcomes: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. 79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison V, Moulds ML, Jones K, 2021. Perceived social support and prenatal wellbeing; The mediating effects of loneliness and repetitive negative thinking on anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women and Birth. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Ito K, Yamaji Y, Sasaki Y, Murashima S, Yanagisawa S, 2011. Difficulties of pregnancy, delivery, and child raising for immigrant women in Japan and their strategies for overcoming them. Journal of International Health 26, 281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Burleson MH, Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT, 2003. Loneliness in everyday life: cardiovascular activity, psychosocial context, and health behaviors. Journal of personality and social psychology 85, 105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT, 2010. Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of behavioral medicine 40, 218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich LM, Gullone E, 2006. The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical psychology review 26, 695–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington E, Doktorchik C, Premji SS, McDonald SW, Tough SC, Sauve RS, 2015. Preterm birth and social support during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology 29, 523–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodnett ED, Fredericks S.J.C.d.o.s.r., 2003. Support during pregnancy for women at increased risk of low birthweight babies. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hoff CE, Movva N, Rosen Vollmar AK, Pérez-Escamilla R.J.A.i.N., 2019. Impact of Maternal Anxiety on Breastfeeding Outcomes: A Systematic Review. 10, 816–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley K, Nguyen T-V, Ditto B, Da Costa D.J.J.o.H.L., 2019. The Association Between Pregnancy-Specific Anxiety and Exclusive Breastfeeding Status Early in the Postpartum Period. 35, 729–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS, 1981. Work stress and social support reading. MA: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Husain N, Rahman A, Husain M, Khan SM, Vyas A, Tomenson B, Cruickshank KJ, 2014. Detecting depression in pregnancy: validation of EPDS in British Pakistani mothers. Journal of immigrant and minority health 16, 1085–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsdottir SS, Thome M, Steingrimsdottir T, Lydsdottir LB, Sigurdsson JF, Olafsdottir H, Swahnberg KJW, Birth, 2017. Partner relationship, social support and perinatal distress among pregnant Icelandic women. 30, e46–e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmaliani R, Asad N, Bann CM, Moss N, Mcclure EM, Pasha O, Wright LL, Goldenberg RL, 2009. Prevalence of anxiety, depression and associated factors among pregnant women of Hyderabad, Pakistan. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 55, 414–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazi A, Fatmi Z, Hatcher J, Kadir MM, Niaz U, Wasserman GA, 2006. Social environment and depression among pregnant women in urban areas of Pakistan: importance of social relations. Social Science & Medicine 63, 1466–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent-Marvick J, Simonsen S, Pentecost R, McFarland MM, 2020. Loneliness in pregnant and postpartum people and parents of children aged 5 years or younger: a scoping review protocol. Systematic reviews 9, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korja R, Nolvi S, Grant KA, McMahon CJCP, Development H, 2017. The relations between maternal prenatal anxiety or stress and child’s early negative reactivity or self-regulation: a systematic review. 48, 851–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AM, Lam SK, Lau SMSM, Chong CSY, Chui HW, Fong DYTJO, Gynecology, 2007. Prevalence, course, and risk factors for antenatal anxiety and depression. 110, 1102–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton HL, Breitkopf CR, Berenson AB, 2007. Correlates of anxiety symptoms during pregnancy and association with perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 196, 424–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma I, Korhonen M, Puura K, Salmelin RK, 2019. Maternal loneliness: concurrent and longitudinal associations with depressive symptoms and child adjustment. Psychology, health & medicine 24, 667–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh J, Kenny RA, Lawlor BA, Steptoe A, Kee F, 2017. The discrepancy between social isolation and loneliness as a clinically meaningful metric: findings from the Irish and English longitudinal studies of ageing (TILDA and ELSA). International journal of geriatric psychiatry 32, 664–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeish J, Redshaw M, 2017. Mothers’ accounts of the impact on emotional wellbeing of organised peer support in pregnancy and early parenthood: a qualitative study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 17, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford DB, Tareen IA, Bajwa MA, Bhatti MR, Karim R, 1991. The translation and evaluation of an Urdu version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 83, 81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumtaz Z, Salway SM, 2007. Gender, pregnancy and the uptake of antenatal care services in Pakistan. Sociology of health & illness 29, 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niaz S, Izhar N, Bhatti M, 2004. Anxiety and depression in pregnant women presenting in the OPD of a teaching hospital. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 20, 117–119. [Google Scholar]

- Nylen KJ, O’Hara MW, Engeldinger J.J.J.o.B.M., 2013. Perceived social support interacts with prenatal depression to predict birth outcomes. 36, 427–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Heron J, Glover V, Alspac Study T, 2002. Antenatal anxiety predicts child behavioral/emotional problems independently of postnatal depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 41, 1470–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Maj M, Flisher AJ, De Silva MJ, Koschorke M, Prince M, WPA Zonal and Member Society Representatives, 2010. Reducing the treatment gap for mental disorders: a WPA survey. World Psychiatry 9, 169–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qadir F, Khalid A, Haqqani S, Medhin G, 2013. The association of marital relationship and perceived social support with mental health of women in Pakistan. BMC Public Health 13, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario MK, Premji SS, Nyanza EC, Bouchal SR, Este D, 2017. A qualitative study of pregnancy-related anxiety among women in Tanzania. BMJ open 7, e016072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J, 2021. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE Publications Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Santini ZI, Jose PE, Cornwell EY, Koyanagi A, Nielsen L, Hinrichsen C, Meilstrup C, Madsen KR, Koushede V, 2020. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. The Lancet Public Health 5, e62–e70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H, 2007. Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. The Lancet 370, 878–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Ram F, 2009. Men’s involvement during pregnancy and childbirth: Evidence from rural Ahmadnagar, India. Population review 48. [Google Scholar]

- Surkan PJ, Hamdani SU, Huma Z. e., Nazir H, Atif N, Rowther AA, Chaudhri R, Zafar S, Mullany LC, Malik A, 2020. Cognitive–behavioral therapy-based intervention to treat symptoms of anxiety in pregnancy in a prenatal clinic using non-specialist providers in Pakistan: design of a randomised trial. BMJ open 10, e037590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surkan PJ, Peterson KE, Hughes MD, Gottlieb BR, 2006. The role of social networks and support in postpartum women’s depression: a multiethnic urban sample. Maternal and child health journal 10, 375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh BR, Mulder EJ, Mennes M, Glover VJN, Reviews B, 2005. Antenatal maternal anxiety and stress and the neurobehavioural development of the fetus and child: links and possible mechanisms. A review. 29, 237–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waqas A, Raza N, Lodhi HW, Muhammad Z, Jamal M, Rehman A, 2015. Psychosocial factors of antenatal anxiety and depression in Pakistan: is social support a mediator? PloS one 10, e0116510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman B, Wortley S, 1990. Different strokes from different folks: Community ties and social support. American journal of Sociology 96, 558–588. [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Mazzoni S, Lauzon M, Borgatti A, Caceres N, Miller S, Dutton G, Salvy S-J, 2020. Associations Between Social Network Characteristics and Loneliness During Pregnancy in a Sample of Predominantly African American, Largely Publicly-Insured Women. Maternal and child health journal 24, 1429–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariah, R.J.R.i.n., health, 2009. Social support, life stress, and anxiety as predictors of pregnancy complications in low‐income women. 32, 391–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP, 1983. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67, 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]