Abstract

Objectives

A 2021 safety alert restricted endovascular gelfoam use in Australia and resulted in an embargo on gelfoam sales to Interventional Radiology departments. This study aimed to show that gelfoam is safe in a population of trauma patients with pelvic injury, and discuss the basis of the recent controversies.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study was conducted between 1 January 2010 and 21 May 2021 for the patients who underwent gelfoam embolization for pelvic arterial haemorrhage. Primary outcome was the rate of adverse events related to intravascular gelfoam administration.

Results

Inclusion criteria met in 50 patients, comprising 58% males median age 59.9 years, and median injury severity score 31. There were 0 complications related to gelfoam use and 100% technical success. Thirty-five patients (70%) received a non-targeted embolization approach. All-cause mortality was observed in 5 patients (10%), unrelated to gelfoam.

Conclusions

Gelfoam is a safe and effective embolic agent in pelvic trauma. Patients are in urgent need of universal on-label registration of endovascular gelfoam products, as it is life-saving in major haemorrhage after trauma.

Advances in knowledge

Endovascular gelfoam is mandatory for a high-quality trauma service, and this study shows that it is safe to use intentionally in the endovascular space. Companies should work with interventional radiologists, sharing and collaborating to ensure positive outcomes for patients.

Keywords: trauma, fracture, pelvis

Introduction

Pelvic trauma requires a multidisciplinary approach to management including resuscitation, prevention/correction of coagulopathy, stabilization, and haemorrhage control.1,2 In up to 10% of patients, pelvic injury may result in bleeding with an arterial source.1 Mortality after pelvic trauma varies but can be as high as 50% in those who are haemodynamically unstable at presentation.3 However, these patients are often very unwell with a high burden of injury, not just within the pelvis.3 From the perspective of an Interventional Radiologist (IR), addressing pelvic arterial haemorrhage is an important strategy to consider early in management, to reduce risk of developing haemorrhage-induced coagulopathy and allow early management of remaining injuries including the bony pelvic ring.4,5

There is no universal standard in which to approach embolization of pelvic bleeding, with practice varying according to local expertise and choice of preferred treatment guideline. However, regardless of approach, embolization is generally considered to be either non-selective or selective.6 Non-selective embolization involves embolization of more than one branch including potential sacrifice of arteries not directly involved with a visible injury.6 It is often quicker and technically less challenging, sometimes leading to earlier haemostasis.6 Selective embolization refers to embolization of only injured arteries usually with a microcatheter, and requires more time and finesse.6 However, it spares adjacent collateral arteries which may not be currently bleeding. While there are advantages and disadvantages to each approach, both have a role as acknowledged by their inclusion in the Western Trauma Association and Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Practice Management Guidelines.7,8

A range of embolic agents are used in embolization of pelvic trauma, including coils, gelatin sponge (gelfoam), N-butyl-cyanoacrylate (NBCA or glue), and others.6 The choice of agent is at operator discretion and often dictated by the specific location and type of injury being treated.

Gelfoam is the most commonly used embolic agent for pelvic trauma when temporary occlusion is desired.6 The use of endovascular gelfoam is not new, having been documented across the world in other endovascular sites as early as 1967.9 It offers many advantages including being quick and easy to prepare, rapidly effective, and is temporary thus allowing treated arteries to recanalize within days-weeks after they have healed. This is particularly useful in non-selective embolization, allowing sacrificed arteries to retain function in the future.10 Gelfoam is so widely used that it features within standard IR teaching, textbooks, and treatment guidelines.

In the setting of splenic artery trauma, Freeman et al assessed the safety of gelfoam embolization, and demonstrated a low rate of adverse events, fewer complications, and a shorter hospital length of stay than with surgical or conservative treatment approaches to splenic injury.11 There have also been several studies from Australia which have shown the safe and cost-effective use of gelfoam.12 However, as with all treatments and medications, adverse events occur, albeit uncommonly.13

However, in May 2021, an email was sent to many Australian IR sites denoting a Safety Alert with the gelfoam product, warning that the product was intended for use on surfaces, and that intravascular use has been associated with adverse events. The safety alert also stated that gelfoam products “must not be placed into the intravascular compartment because of risk of embolisation” (Supplementary material). This coincided with a manufacturer embargo on product sales to IR departments.

This safety alert did not reflect Australian or international IR user experiences, of what was the most widely used gelfoam product by IRs in Australia.14 This product was highly effective when deliberately used either in a macerated paste or as pledgets even though intravascular use was known to be off-label. This product was initially placed on market in 2009 and every day across Australia it was used to save lives from arterial bleeding, particularly in the setting of acute pelvic trauma where its availability is mandatory for an IR trauma service to exist.

This study aimed to add to the evidence base that the use of gelfoam in Australia is safe and effective in a cohort of critically unwell adult patients suffering traumatic pelvic arterial injury. The study aimed to show that the product is safe for intentional intravascular use, and to emphasise the need for nuanced consideration of the risk of issuing safety recalls that are at odds with a wide body of international expert consensus and literature.

Methods

Ethics and governance

The use of this data was approved by our institutional review board and conforms to the STROBE checklist. This retrospective cohort study forms a sub analysis of a larger dataset on pelvic arterial injury.15

Population

All patients from our adult level 1 trauma centre were included from January 1, 2010 (after the period of gelfoam registration),14 to the date of safety alert on May 21, 2021 (Supplementary material). Specific inclusion criteria included:

Traumatic pelvic injury resulting in arterial haemorrhage within the study period.

The sole use of gelfoam (Gelfoam gelatin sponge, Pfizer Australia, Mulgrave, Victoria) as an embolic agent, not combined with other embolic agents, to arrest haemorrhage.

All patients over the age of 18.

Patients were excluded if gelfoam was used in combination with another embolic agent, or not used at all.

Data and outcomes

Data were collected from the first 30-days after injury from a combination of the Electronic Medical Record and the Alfred Trauma Registry. Adverse events related to gelfoam administration were the primary endpoint, while all-cause 30-day mortality was the secondary endpoint. The primary endpoint was defined as an adverse event that was considered related to the intravascular administration of gelfoam. This included ischaemic muscle or skin necrosis in the distribution of embolization, abscess formation, an acute thromboembolic event during embolization (eg, pulmonary thromboembolism), or death.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata (Version 17.0-BE, StataCorp, TX, United States). Data were presented as mean (standard deviation), median (range), or number (percentage) according to the type and distribution. Significance testing was not required for this single-cohort analysis.

Results

As shown in Figure 1, embolization was performed in 171 patients during the study period. Exclusion criteria were applied to 121 as they were treated with an embolic other than gelfoam, or gelfoam in combination with another embolic such as coils.

Figure 1.

Inclusion criteria and outcomes of the study.

Summary statistics are shown in Table 1. Males comprised 58%, median age was 59.9 years (range 18-91), and median injury severity score (ISS) was 31 (range 1-75). The median number of packed red blood cell transfusion was 4 units (range 0-54) and fresh frozen plasma 2 units (range 0-42). Forty-seven patients (94%) had a concomitant pelvic fracture but only 3 (6%) were taking a therapeutic-dose anticoagulant at the time of injury.

Table 1.

Summary statistics of patients with traumatic pelvic haemorrhage treated with gelfoam embolization.

| Variable | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Total | 50 |

| Male sex, number (percentage) | 29 (58%) |

| Age in years, median (range) | 59.9 (18-91) |

| Injury severity score, median (range) | 31 (1-75) |

| Unstable at presentation as defined by Shock Indexa >1, number (percentage) | 13 (26%) |

| Mechanism of injury, number (percentage) |

|

| Time from arrival to embolization in hours, median (range) | 3.6 (0.5-40) |

| Units of packed red blood cells required in first 24 h, median (range) | 4 (0-54) |

| Units of fresh frozen plasma required in first 24 h, median (range) | 2 (0-42) |

| Units of platelets required in first 24 h, median (range) | 0 (0-8) |

| Concomitant pelvic fracture, number (percentage) | 47 (94%) |

| Therapeutic anticoagulation, number (percentage) | 3 (6%) |

| Technical success, number (percentage) | 50 (100%) |

| Procedural complications, number (percentage) | 0 (0%) |

| Gelfoam complications, acute, number (percentage) | 0 (0%) |

| Gelfoam complications, delayed, number (percentage) | 0 (0%) |

| Non-selective embolization, number (percentage) | 35 (70%) |

| Required repeat procedure due to ongoing haemorrhage, number (percentage) | 0 (0%) |

| Intensive care unit length of stay in days, median (range) | 3 (0-30) |

| Hospital length of stay in days, median (range) | 14 (1-83) |

| Gelfoam-related mortality, number (percentage) | 0 (0%) |

| All-cause trauma-related mortality, number (percentage) | 5 (10%) |

Shock index = Heart rate/Systolic blood pressure.

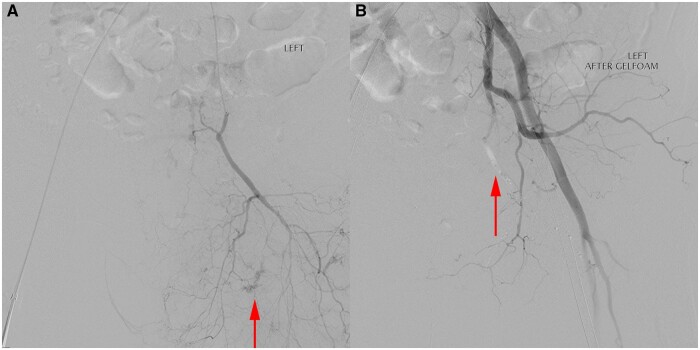

In terms of the primary endpoint, there were zero complications related to gelfoam and zero patients died as the result of endovascular gelfoam administration. This included immediate, acute, or delayed complications up to 30 days post embolization. Technical success was observed at the time of gelfoam administration in all 50 patients (100%) and no patients required a repeat embolization. Thirty-five patients (70%) received a non-targeted embolization approach as shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Trauma CT shows pelvic fracture (arrow) and extraperitoneal haematoma (asterisk).

Figure 3.

Angiogram showing (A) small foci of arterial bleeding (arrows). After non-target gelfoam embolization (B) the bleeding has ceased, and there is static contrast/gelfoam seen in the embolized vessel (arrow).

All-cause mortality was observed in 5 patients (10%), all unrelated to gelfoam or the treated arterial bleeding site. However, in the deceased cohort, the median ISS was higher (43 vs 31) and patients received a higher median volume of blood products (6 units packed red blood cells vs 4, and 6 units fresh frozen plasma vs 2). Significance testing was not performed given the small sample size.

Discussion

In this study, gelfoam was shown to be safe and technically effective in the treatment of acute traumatic pelvic haemorrhage. This was using a gelfoam product off-label, which was subsequently and surprisingly recalled due to unspecified safety concerns. Unsurprisingly, this reflects over 50 years of published literature and established practice and is supported by major international guidelines.7,8,16,17 So far, studies showing complications after gelfoam use have been scant. In an animal model from Li et al, the authors showed that the use of 50-150 µm gelfoam particles increases the risk of ischaemic complications in the pelvic viscera. However, these particles are far smaller than are used in a traditional slurry form for trauma embolization.18 Hundersmarck et al recently reported their experience of pelvic trauma management which included 74 patients undergoing embolization, with 3 in-hospital cases of skin necrosis.19 The authors queried an additional 10 cases of delayed out-of-hospital adverse events including erectile dysfunction, osseous non-union, and rectal pain, for which it is hard to reasonably attribute this to gelfoam use in the context of severe pelvic trauma, operative fixation, and a range of potential more likely causes than gelfoam. There are also other non-traumatic indications for which endovascular gelfoam has also shown to be safe and effective, and while this list is non exhaustive, includes post-partum haemorrhage management, embolization of symptomatic uterine fibroids, bronchial artery embolization for haemoptysis, embolization of retroperitoneal haemorrhage, rectal artery embolization for haemorrhoids, and portal vein embolization.20,22–27

The role of the Therapeutic Goods Association (TGA) in Australia is to evaluate, assess, and monitor products in Australia according to the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989. This role includes drugs and medical devices. They also govern reporting of adverse events, issuance of safety alerts, and recalls. The TGA plays an important role in ensuring that devices comply with relevant legislation, but also in protecting patients by ensuring that devices and drugs meet an evidence-based standard.

The safety alert created confusion and significant concerns, as it disrupted accepted, life-saving practice by reducing access to temporary non-selective embolization in critically unwell patients. The confusion was accentuated by the availability of endovascular gelfoam for use on-label in many countries including the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the United States. While this situation is currently unique to Australia, it highlights a potential future risk for other countries and a need to publish safety data on the topic.

This study supports the urgent and immediate need for gelfoam products in Australia which are on-label for use within the intravascular space for intentional embolization, and we encourage IRs, medical device companies, IR societies, and those in IR governance to lobby the TGA to improve access to gelfoam products for the endovascular management of haemorrhage. Such products are not at the point of navigating a novel treatment approach, but merely enabling patients to receive the minimum standard of care in trauma IR. This will require drug and device companies to work with IRs, sharing and collaborating on ideas and data. There is also an urgent need for regulatory bodies to recognise the modern role that IR plays in healthcare and integrate IRs within regulatory and advisory positions.21 These steps will help to prevent a repeat of this unfortunate safety recall and embargo.

It is acknowledged that this is a single-centre cohort study with a small sample size. However, prospective assessment of embolic agents is difficult and outside the scope of the aims of presenting this data. The sample also represents a large timeframe for acute pelvic haemorrhage management within our population. Large and prospective studies are desirable. However, iterative gelfoam and other temporary embolic products including non-porcine options are also desirable, with many drugs and devices known to be currently under evaluation. This should not detract from urgent clarification of gelfoam use, which remains a priority.

Conclusion

This study showed that gelfoam is safe and highly effective when used as an embolic agent for critically unwell injured adults with pelvic fractures and uncontrolled arterial bleeding. Patients are in urgent need of on-label registration of an endovascular gelfoam product in Australia, and IRs are encouraged to publish safety data on gelfoam use in a range of settings to prevent a repeat of these events in other countries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Alfred trauma registry for their help with data collection for the study. The authors also acknowledge the assistance of Joseph Mathew, Tallula Dunne, Steven Clare, Ee Jun Ban, and Jim Koukounaras.

Contributor Information

Warren Clements, Department of Radiology, Alfred Health, Melbourne 3004, Australia; Department of Surgery, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne 3004, Australia; National Trauma Research Institute, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne 3004, Australia.

Matthew Lukies, Department of Radiology, Alfred Health, Melbourne 3004, Australia.

Adil Zia, Department of Radiology, Alfred Health, Melbourne 3004, Australia.

Mark Fitzgerald, Department of Surgery, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne 3004, Australia; National Trauma Research Institute, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne 3004, Australia; Department of Trauma, Alfred Health, Melbourne 3004, Australia.

Helen Kavnoudias, Department of Radiology, Alfred Health, Melbourne 3004, Australia; Department of Surgery, Central Clinical School, Monash University, Melbourne 3004, Australia.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at BJR online.

Funding

None declared.

Conflicts of interest

W.C., M.L., A.Z., and H.K. disclose that they are investigators in the Merit Medical EmboCube study. The authors have no other financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Approval to conduct this study was provided by the Alfred Hospital Human Research and Ethics Committee. For this type of study formal consent is not required.

References

- 1. Rommens PM, Hofmann A, Hessmann MH.. Management of acute hemorrhage in pelvic trauma: an overview. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2010;36(2):91-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vaidya R, Waldron J, Scott A, Nasr K.. Angiography and embolization in the management of bleeding pelvic fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018;26(4):e68-e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tanizaki S, Maeda S, Matano H, Sera M, Nagai H, Ishida H.. Time to pelvic embolization for hemodynamically unstable pelvic fractures may affect the survival for delays up to 60 min. Injury. 2014;45(4):738-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mikdad S, van Erp IA, El Moheb M, et al. Pre-peritoneal pelvic packing for early hemorrhage control reduces mortality compared to resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta in severe blunt pelvic trauma patients: a nationwide analysis. Injury. 2020;51(8):1834-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wong YC, Wang LJ, Ng CJ, Tseng IC, See LC.. Mortality after successful transcatheter arterial embolization in patients with unstable pelvic fractures: rate of blood transfusion as a predictive factor. J Trauma. 2000;49(1):71-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mirakhur A, Cormack R, Eesa M, Wong JK.. Endovascular therapy for acute trauma: a pictorial review. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2014;65(2):158-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tran TL, Brasel KJ, Karmy-Jones R, et al. Western trauma association critical decisions in trauma: management of pelvic fracture with hemodynamic instability—2016 updates. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(6):1171-1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cullinane DC, Schiller HJ, Zielinski MD, et al. Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guidelines for hemorrhage in pelvic fracture—update and systematic review. J Trauma. 2011;71(6):1850-1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ishimori S, Hattori M, Shibata Y, Shizawa H, Fujinaga R.. Treatment of carotid-cavernous fistula by gelfoam embolization. J Neurosurg. 1967;27(4):315-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barth KH, Strandberg JD, WHITE JRRI.. Long term follow-up of transcatheter embolization with autologous clot, oxycel and gelfoam in domestic swine. Invest Radiol. 1977;12(3):273-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Freeman C, Moran V, Fang A, Isreal H, Ma S, Vyas K.. Nonoperative management of blunt splenic trauma: outcomes of gelfoam embolization of the splenic artery. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2018;11(4):293-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clements W. Embolization of acquired uterine arteriovenous fistula and pseudoaneurysm as a definitive uterine-sparing treatment. EJMCR. 2020;4(3):107-109. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khoriaty E, McClain CD, Permaul P, Smith ER, Rachid R.. Intraoperative anaphylaxis induced by the gelatin component of thrombin-soaked gelfoam in a pediatric patient. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;108(3):209-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Australian Government. Therapeutic Goods Association. Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd—Gelfoam Sponge—Gelatin haemostatic agent (160667) [Internet]. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.tga.gov.au/resources/artg/160667

- 15. Clements W, Dunne T, Clare S, et al. A retrospective observational study assessing mortality after pelvic trauma embolisation. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Velmahos GC, Chahwan S, Hanks SE, et al. Angiographic embolization of bilateral internal iliac arteries to control life-threatening hemorrhage after blunt trauma to the pelvis. Am Surg. 2000;66(9):858-862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jander HP, Russinovich NA.. Transcatheter gelfoam embolization in abdominal, retroperitoneal, and pelvic hemorrhage. Radiology. 1980;136(2):337-344. 10.1148/radiology.136.2.6967615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li Y, Yin Z, Wang W, Qin K, Wang Y.. [Complication after selective arterial embolization in internal iliac artery and median sacral artery with gelfoam particle in dogs]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011;25(6):724-728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hundersmarck D, Hietbrink F, Leenen LPH, Heng M.. Pelvic packing and angio-embolization after blunt pelvic trauma: a retrospective 18-year analysis. Injury. 2021;52(4):946-955. 10.1016/j.injury.2020.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang XQ, Chen XT, Zhang YT, Mai CX.. The emergent pelvic artery embolization in the management of postpartum hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2021;76(4):234-244. 10.1097/OGX.0000000000000887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clements W, Goh GS, Lukies MW, et al. What is a modern interventional radiologist in Australia and New Zealand? J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2020;64(3):361-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cheng L, Zhao X, Hu X, Huang J, Zhang X.. Safety and efficacy comparison of embospheres and gelfoam particles in bronchial artery embolization for massive hemoptysis. Altern Ther Health Med. 2023;29(5):298-301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ahn JM, Oh JS.. Gelfoam embolization technique to prevent bone cement leakage during percutaneous vertebroplasty: comparative study of gelfoam only vs. gelfoam with venography. Korean J Neurotrauma. 2020;16(2):200-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lukies M, Gipson J, Tan SY, Clements W.. Spontaneous retroperitoneal haemorrhage: efficacy of conservative management and embolisation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2023;46(4):488-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang X, Sheng Y, Wang Z, et al. Comparison of different embolic particles for superior rectal arterial embolization of chronic hemorrhoidal bleeding: gelfoam versus microparticle. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(1):465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cazejust J, Bessoud B, Le Bail M, Menu Y.. Preoperative portal vein embolization with a combination of trisacryl microspheres, gelfoam and coils. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2015;96(1):57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yadavali R, Ananthakrishnan G, Sim M, et al. Randomised trial of two embolic agents for uterine artery embolisation for fibroids: Gelfoam versus Embospheres (RAGE trial). CVIR Endovasc. 2019;2(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.