In this issue, Jennings et al. describes the emergence of the leucine rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) inhibitor BIIB122 from the Valley of Death1. The Valley of Death is the formidable abyss that exists between target identification and first in human studies2. So named because few targets and therapeutics that enter the Valley make it out the other side, Jennings et al. presents a rare look into the Valley of Death not typically published in Parkinson disease (PD) neuroprotectants. The study involved 186 healthy participants as well as 36 PD patients, randomized and treated in Phase 1 and 1b studies, respectively. Endpoints that were disclosed related to BIIB122 pharmacodynamics, target (i.e., LRRK2) engagement in different biomarker assays, and safety in 28-day dosing. BIIB122 comes on the heels of a previous publication with the LRRK2 kinase inhibitor DNL2013. DNL201 was likewise evaluated in Phase 1 and 1b studies in a slightly smaller cohort. Inhibitor profiles between BIIB122 and DNL201 appear overall similar although a direct head-to-head comparison of BIIB122 characteristics versus DNL201 was not formally presented. Perhaps the major difference includes once daily BIIB122 administration compared to twice daily for DNL201 with similar responses. Now, BIIB122 heads to efficacy studies both in the LIGHTHOUSE trial (NCT05418673) in pathogenic LRRK2 variant carriers as well as the LUMA trial in early-stage idiopathic PD patients (NCT05348785). This editorial highlights the importance of the Jennings et al. study in the context of recent and ongoing neuroprotectant trials in PD, as well as current LRRK2-related research in PD. The opinions and thoughts expressed reflect only the Authors’ views.

In the Valley of Death, drug and assay development, optimization, and safety studies are known to suffer unsettlingly high attrition rates4. Most of the fiscal brunt of failure has historically rested on the shoulders of large pharmaceutical companies. But recent years have witnessed a whole-scale recession of neuroscience programs in industry5–8. Among other factors, rising costs associated with studies in the Valley of Death and overall risk aversion to neurodegenerative disease investments have been exacerbated by expensive failures in Alzheimer’s disease. Unsurprisingly, candidates relevant to neurodegenerative diseases that are well-equipped to enter the Valley will become fewer and fewer, with efforts instead placed on cheaper alternatives such as the repositioning of existing drugs that have been through the Valley in some form. In the wake of broad industry withdrawal in neuroprotectant trials, the public agencies and foundations have entered the PD trial space in force, for example, with isradipine in STEADY-PD III, nilotinib in NILO-PD, and the GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide. The work in Jennings et al. distinguishes from these past trials in elaborating a biomarker and target-engagement driven strategy for drug choice (e.g., BIIB122 versus DNL201), informed dose, and patient selection.

With respect to target engagement, a crucial element of precision in modern clinical trial approaches9, 10, Jennings et al. demonstrates BIIB122 at moderate dose (e.g., 150 mg Q.D.) reduces total LRRK2 protein ~50% in CSF of PD. Higher doses of drug (e.g., 250 mg B.I.D.) caused a near complete ablation of LRRK2 protein levels in CSF in some patients. These results fall in line with pre-clinical observations in non-human primates with tool compound LRRK2 inhibitors that likewise cause a dramatic reduction of total LRRK2 in CSF11. The biology surrounding this phenomenon involves a probable two-part mechanism whereby LRRK2 inhibitors cause the loss of 14–3-3 binding and reduced release via exosome cargo12, 13, as well enhanced degradation of LRRK2 in the cytoplasm of cells in some tissues14, 15. Although the analysis of LRRK2 mutation carriers was not conducted in Jennings et al., some data in a previous study suggest the activating G2019S mutation in patients may nominally increase the total amount of LRRK2 protein in CSF16. A major difference between purpose-built drugs like BIIB122 and other repositioned drugs like isradipine is that brain penetration is championed early in the development pipeline of the former. While most drugs can be detected in the CSF to some extent owing to the intrinsic biology of the blood-CSF barrier, a rich history in other fields (for example, anti-infective drugs) show that fairly robust CSF accumulations of drug are needed for successful target engagement in deep parenchymal brain tissue with few exceptions17. BIIB122 shows typical CSF to plasma unbound ratios (e.g., ~1:1) for successful brain penetration. However, peripheral LRRK2 activity, for example in immune cells, has also been suggested to play a role in the pathobiology of LRRK2-linked PD18, 19. Beyond Jennings et al., a more controversial question should be raised whether any CNS-directed experimental therapeutic in PD that lacks clear target engagement data in the brain should advance to efficacy trials, irrespective of available funding.

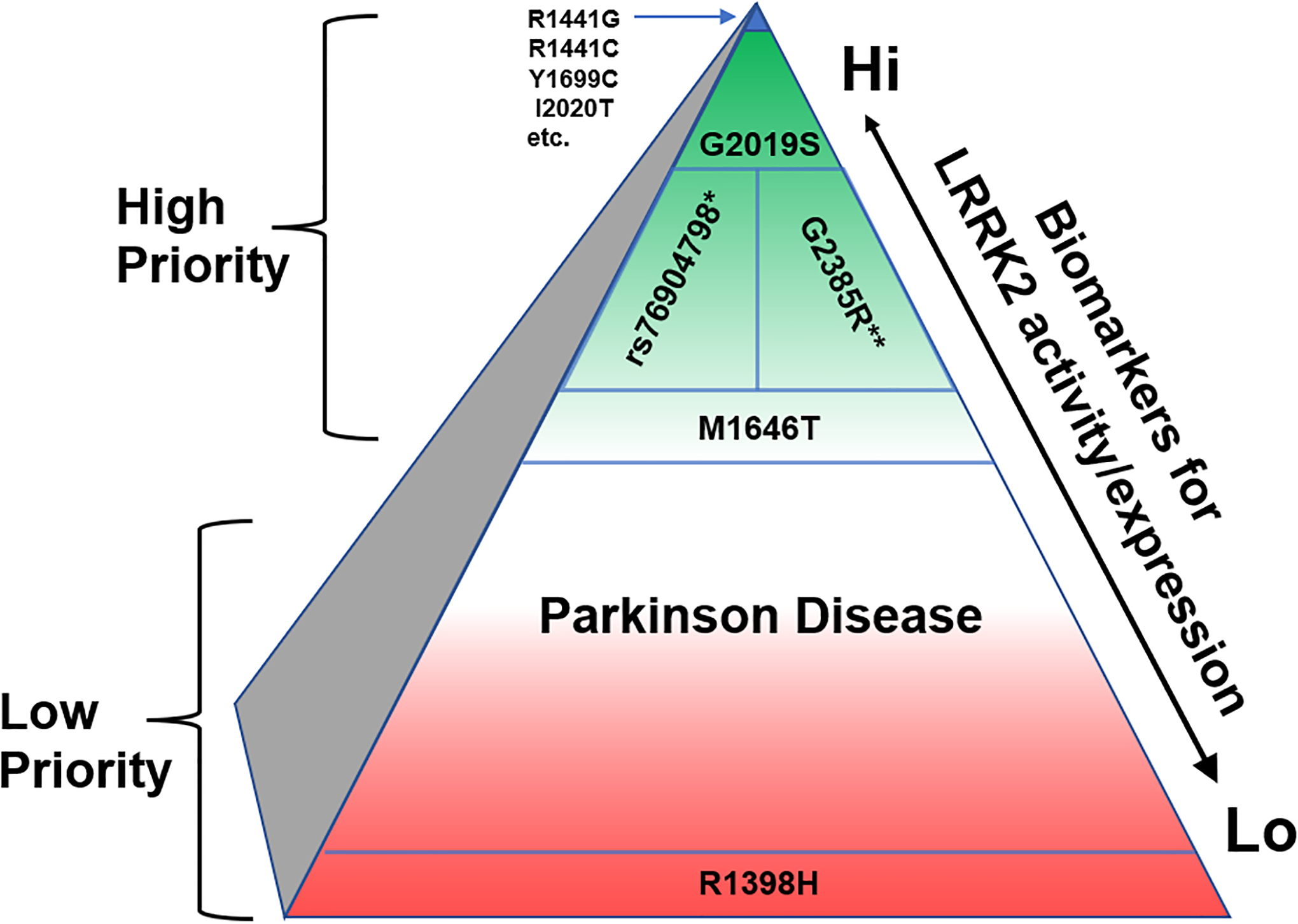

Clinical trials focused on targets that have good evidence for genetic association with disease, especially Mendelian associations like LRRK2 in PD, are greater than two-fold as likely to lead to approved drugs than targets without genetic associations20. In moving to the clinic, the rational for isradipine, c-Abl inhibition, and GLP-1 receptor activation rely heavily on observations in pre-clinical models (as well as epidemiological data). In contrast, the main rationale for linking LRRK2 with PD continues to center on quantifiable genetic risks that can be stratified in effect size (Fig. 1). Initial reports of autosomal dominant PD families that mimicked idiopathic PD phenotypes were reported nearly three decades ago21, with so-called PARK8 families subsequently accumulating in many centers around the world. These families all harbored missense variants in LRRK2, and recent observations have confirmed that LRRK2-linked disease is so close to idiopathic PD that patients still require a genetic test for identification. BIIB122 is advancing to some of these LRRK2 variant carriers in the LIGHTHOUSE trial.

Figure 1. Hypothesized genetic and biomarker-based enrichments may maximize the potential for LRRK2-targeting therapies in PD.

Green coloration indicates the PD population that might be prioritized for enrollment in LRRK2-targeted therapies, whereas red coloration indicates PD cases that might be lower priority initially. *rs76904798 is linked to PD in Caucasian populations but not East Asians, and **G2385R is linked to PD in East Asians and not Caucasians. The N551K-R1398H haplotype might be protective from PD and highlight cases where LRRK2 may not play a major role in risk or progression. Putative LRRK2-activity biomarkers might include measures of autophosphorylated LRRK2 (pS1292-LRRK2) or Rab protein phosphorylation (e.g., pT73-Rab10).

Among the pathogenic (i.e.,Mendelian) LRRK2 variants, G2019S reigns king in Western PD populations with respect to combined effect size in disease risk and higher frequency as affirmed by whole-genome sequencing efforts around the world22. In the United States alone, more than 5,000 people with PD are estimated be G2019S carriers22, 23. This sizable population suggests a sufficient worldwide population to support concurrent therapeutic candidate efficacy studies, though their efficiency will benefit greatly from mounting efforts to introduce routine CLIA-certified PD gene testing into the clinic. Moreover, there are other opportunities besides Mendelian LRRK2 variant carriers (e.g., G2019S-LRRK2 carriers) to garner the apparent benefits genetic targets offer for drug approval likelihood. The LRRK2 promoter variant rs76904798, independently associated with PD from the Mendelian variants, is one of the strongest known genome-wide associations for PD risk in Caucasians24. In East Asians, some genetic variants in LRRK2 are behind only SNCA in genome-wide significance, presumably due to the strong effect of the G2385R and R1628P missense variants that are not present in Caucasian populations25. Thus, rs76904798 and G2385R carriers, with the common M1646T risk variant, provide a population much larger than the G2019S carrier population that could be considered in the future (Fig. 1).

To the extent that current and imminent LRRK2 PD trials may presently rely on G2019S carriers, the emerging evidence for a counterintuitive slower clinical progression in G2019S-LRRK2 PD raises an important caveat to the therapeutic hypothesis of LRRK2 inhibition. Although indistinguishable from idiopathic PD at the level of an individual subject’s symptoms, G2019S-LRRK2 PD collectively may differ in its pathological26 and clinical features27, including in its generally slower rate of worsening of both its motor and non-motor features28. If excessive LRRK2 kinase activity is indeed the basis of elevated PD risk among G2019S carriers it may also be the basis of their relatively favorable clinical progression in manifest disease. Thus it must be considered that while LRRK2 kinase inhibition in G2019S carriers at-risk for PD may help prevent the disease, the same treatment might paradoxically accelerate its progression in carriers with manifest PD. The safety implications of this risk-progression paradox can be readily addressed in the design of efficacy trials, for example, by ensuring periodic monitoring of clinical progression rate as a safety rather than an efficacy measure, and by unblinded study statisticians and a suitable safety monitoring board.

On a biochemical level, BIIB122 seems purpose-built to bind to the ATP-pocket of the LRRK2 kinase domain to interrupt the ability of LRRK2 to bind ATP, block autophosphorylation, as well as the phosphorylation of other Rab proteins. LRRK2 is a large multi-domain protein with PD risk variants and pathogenic missense mutations scattered from non-coding domains to missense mutations in the Rab-like “ROC” domain (Ras-of-complex), the connecting COR (C-terminal of ROC) domain, the serine/threonine kinase domain, and the WD-40 like domain. The so-called ROCO family proteins include LRRK2 and LRRK1 in mammals, but many orthologues in lower organisms omit the kinase domain altogether in favor of a conserved Rab-like ROC and COR combination29. Indeed, the most penetrant LRRK2 missense variants with respect to PD risk lie within the ROC and COR domain (e.g., R1441C and Y1699C) and not the kinase domain (e.g., G2019S)30. What if the underlying assumption, that LRRK2 kinase activity is the part of LRRK2 biology influencing PD risk or progression, is fundamentally wrong; could BIIB122 then be successful in efficacy trials?

Because of this residual uncertainty over the kinase overactivity hypothesis of LRRK2 pathogenicity, after nearly two decades of bench research, the main evidence that support it should be critically evaluated and continually challenged experimentally, especially with clinical samples. In 2005, crude in vitro autophosphorylation measurements of LRRK2 using radioactive phosphorous demonstrated that both the R1441C mutation in the ROC domain as well as G2019S mutation increased LRRK2 autophosphorylation activity in test tubes31. Advances in mass spectrometry led to the identification of specific LRRK2 autophosphorylation sites, and in 2012, antibodies to the main autophosphorylation site at Ser1292 demonstrated that all known Mendelian LRRK2 missense mutations shared the property of increasing cis-LRRK2 kinase activity, at least in transfected HEK-293T cells32. With clinical samples, the clearest evidence for enhanced autophosphorylated pS1292-LRRK2 has been provided in the analysis of urine samples from G2019S carriers33. A subset of idiopathic PD may also have high pS1292-LRRK234, but this result awaits replication. In 2016, candidate proteomic approaches identified several Rab small GTPase LRRK2 substrates (e.g., Rab10) to demonstrate a shared gain-of-function effect for LRRK2 mutations on trans-LRRK2 Rab phosphorylation35. The clearest evidence for enhanced pT73-Rab10 levels in clinical samples comes from the analysis of blood cells from R1441G carriers36. Based again on urine samples from idiopathic PD cases, some patients may share the high pT73-Rab10 biomarker37, but this result awaits replication. Interestingly, the phosphorylation events dependent on LRRK2 activity, pS1292-LRRK2 and pT73-Rab10, do not appear to correlate well, either in LRRK2 mutational screens or in patient biofluids, suggesting a complex biology that is not well understood38. Given the intense research focus on LRRK2 function in model systems (e.g., mice, iPSCs, etc.), there is little known about how LRRK2 kinase activity may change over the course of disease in patients, and how LRRK2 activity varies from person to person. The biomarker assays employed in Jennings et al. highlight the opportunity that exists to probe whether LRRK2 activity variance may serve as a valuable biomarker of PD risk in healthy populations or those with genetic or prodromal features predisposing to the disease, along with other promising, emerging biomarkers of PD pathophysiology like α-synuclein seed amplification activity. Moreover, while the aforementioned genetic and biochemical evidence for a preventative benefit of LRRK2 kinase inhibition is compelling, it remains less certain if not controversial how LRRK2 kinase inhibitors – or LRRK2 missense mutations for that matter – may alter progression of manifest disease. As inhibitors like BIIB122 and LRRK2-targeting antisense oligonucleotides (e.g., BIIB094) enter efficacy trials, it seems unlikely that the debate for whether LRRK2 should be expected to modify disease progression will be settled in pre-clinical models alone. However, should BIIB122 or other LRRK2-targeting therapeutics successfully slow disease progression in PD patients, these therapeutics can positively feedback into the pre-clinical space to help refine better PD models to increase the likelihood of predictive results in the clinic.

Of paramount importance, Jennings et al. begins to tackle, but does not fully resolve, whether it is safe to inhibit LRRK2 kinase activity in people, and particularly over years in people with PD. At the highest levels of BIIB122, no serious adverse events were reported, and treatment emergent adverse events were mild. This is consistent with disclosures related to DNL2013. In combining the BIIB122 and DNL201 Phase I safety data, targeting LRRK2 kinase activity appears exceptionally safe with short-duration (28-day) treatment. These studies emerge out of a cloud of initial safety concerns that began in earnest with reports of increased vacuoles in some subsets of type II lung pneumocytes associated with higher doses of LRRK2 inhibitors in non-human primates39. This report had a chilling effect on the field. Lung changes were labeled pathological in the first reports, albeit without clear functional correlations to a deficit or disease. A follow up study with multiple pharmacologically distinct inhibitors addressed some of the main questions to show that relatively high drug exposures are needed to produce the lung changes, and these changes wash out rapidly with drug cessation14. Because the lung histological changes have not been clearly quantified and occur without functional deficit, it is difficult to establish a dose-response relationship with respect to drug levels reported by Jennings et al. Nevertheless, in moving forward, it seems reasonable to clearly disclose to sites and patients that the highest doses of BIIB122 reported by Jennings et al. have the potential to result in lung features that so-far are understood as benign histopathological changes. Apart from on-target adverse effects, most analogs of the original Genentech series of compounds described by Estrada et al.40, a parental series possibly related to BIIB122, suffer from off-target interactions with the dual specificity protein kinase TTK. Although it is unclear what the full potential off-target interactions of BIIB122 might be (along with the currently undisclosed structure of BIIB122), idiosyncratic liabilities inherent to BIIB122 like TTK off-target interaction should not be conflated with on-target liabilities. A better knowledge of on-target (e.g., LRRK2-related) liabilities will probably evolve over time as other distinct LRRK2-targeting therapeutics advance in the future.

In summary, the data presented in the Jennings et al. Phase I studies provide a guide for how biomarker and target engagement assays intersect in advancing neuroprotectant therapeutics through the Valley of Death. The stakes are high. If BIIB122 were successful in slowing PD, there will be a wave of renewed enthusiasm not only for more LRRK2-targeting therapeutics, but for translational neurodegenerative disease research across the board. If BIIB122 were unsuccessful, the data presented in Jennings et al. will prove an invaluable resource in both setting a clear bar for other CNS-targeting LRRK2 therapeutic candidates, as well as how precision should be engineered in PD patients early in clinical development.

Acknowledgements

A.B.W. and M.A.S. wrote the manuscript. A.B.W. has received a past research grant from Biogen to study the biology of LRRK2 in PD models, focused on the pathobiology of the G2385R-LRRK2 variant. M.A.S. receives consultancy payment from the Parkinson Study Group for service on the Global Steering Committee of LIGHTHOUSE and LUMA studies of BIIB122.

Relevant Conflicts of interests/Financial disclosures

A.B.W. has received federal research grant support from NIH NINDS R01 NS064934, P50 NS108675 and R33 NS097643, and has served as a member of the Michael J. Fox Executive Foundation (MJFF) Scientific Advisory Board, a paid consultant for EscapeBio Inc., and has received research grants from Biogen Inc. and EscapeBio, Inc, as well as MJFF, ASAP foundation, Parkinson’s Foundation, and National Institutes of Health. A.B.W. is part owner of a series of LRRK2 kinase inhibitor (WO 2013166276) and part owner of induced-pluripotent stem cell lines of early-onset PD distributed by Cedars Sinai. M.A.S. receives consultancy payment from the Parkinson Study Group (PSG) for service on the Global S teering Committee of LIGHTHOUSE and LUMA for studies of BIIB122. He also received advisory board, data monitoring committee, steering committee, and/or travel payments in the past 3 years from Denali Therapeutics, Eli Lilly & Co, the PSG (for advising Bial, Biogen, Partner Therapeutics, and UCB), Cure Parkinson’s, World Parkinson Congress, Parkinson’s Foundation, MJFF, Sutter Health, Northwestern University, and National Institutes of Health.

Funding

This manuscript was supported by NIH R01s NS064934 and NS110879

Citations

- 1.Jennings et al. (Placeholder) LRRK2 Inhibition by BIIB122 in Healthy Participants and Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. In press Movement Disorders 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler D Translational research: crossing the valley of death. Nature 2008;453(7197):840–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jennings D, Huntwork-Rodriguez S, Henry AG, et al. Preclinical and clinical evaluation of the LRRK2 inhibitor DNL201 for Parkinson’s disease. Sci Transl Med 2022;14(648):eabj2658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkbeiner S. Bridging the Valley of Death of therapeutics for neurodegeneration. Nat Med 2010;16(11):1227–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fillit H Pfizer Ends Its Neuroscience Program—What Does it Mean For Alzheimer’s? 2018.

- 6.Lowe D. Amgen and Neuroscience. In the Pipeline 2019.

- 7.Adams B. Eli Lilly to shutter neuroscience R&D center next year. 2019.

- 8.Jarvis LM. Tough Times For Neuroscience R&D. 2012.

- 9.Kelly K, West AB. Pharmacodynamic Biomarkers for Emerging LRRK2 Therapeutics. Front Neurosci 2020;14:807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon GM, Niphakis MJ, Cravatt BF. Determining target engagement in living systems. Nat Chem Biol 2013;9(4):200–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang S, Kelly K, Brotchie JM, Koprich JB, West AB. Exosome markers of LRRK2 kinase inhibition. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2020;6(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang S, West AB. Caught in the act: LRRK2 in exosomes. Biochem Soc Trans 2019;47(2):663–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraser KB, Moehle MS, Daher JP, et al. LRRK2 secretion in exosomes is regulated by 14–3-3. Hum Mol Genet 2013;22(24):4988–5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baptista MAS, Merchant K, Barrett T, et al. LRRK2 inhibitors induce reversible changes in nonhuman primate lungs without measurable pulmonary deficits. Sci Transl Med 2020;12(540). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly K, Wang S, Boddu R, et al. The G2019S mutation in LRRK2 imparts resiliency to kinase inhibition. Exp Neurol 2018;309:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mabrouk OS, Chen S, Edwards AL, Yang M, Hirst WD, Graham DL. Quantitative Measurements of LRRK2 in Human Cerebrospinal Fluid Demonstrates Increased Levels in G2019S Patients. Front Neurosci 2020;14:526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nau R, Sorgel F, Eiffert H. Penetration of drugs through the blood-cerebrospinal fluid/blood-brain barrier for treatment of central nervous system infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010;23(4):858–883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu E, Boddu R, Abdelmotilib HA, et al. Pathological alpha-synuclein recruits LRRK2 expressing pro-inflammatory monocytes to the brain. Mol Neurodegener 2022;17(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozina E, Sadasivan S, Jiao Y, et al. Mutant LRRK2 mediates peripheral and central immune responses leading to neurodegeneration in vivo. Brain 2018;141(6):1753–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.King EA, Davis JW, Degner JF. Are drug targets with genetic support twice as likely to be approved? Revised estimates of the impact of genetic support for drug mechanisms on the probability of drug approval. PLoS Genet 2019;15(12):e1008489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wszolek ZK, Pfeiffer B, Fulgham JR, et al. Western Nebraska family (family D) with autosomal dominant parkinsonism. Neurology 1995;45(3 Pt 1):502–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryant N, Malpeli N, Ziaee J, et al. Identification of LRRK2 missense variants in the accelerating medicines partnership Parkinson’s disease cohort. Hum Mol Genet 2021;30(6):454–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lake J, Reed X, Langston RG, et al. Coding and Noncoding Variation in LRRK2 and Parkinson’s Disease Risk. Mov Disord 2022;37(1):95–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nalls MA, Blauwendraat C, Vallerga CL, et al. Identification of novel risk loci, causal insights, and heritable risk for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol 2019;18(12):1091–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foo JN, Chew EGY, Chung SJ, et al. Identification of Risk Loci for Parkinson Disease in Asians and Comparison of Risk Between Asians and Europeans: A Genome-Wide Association Study. JAMA Neurol 2020;77(6):746–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalia LV, Lang AE, Hazrati LN, et al. Clinical correlations with Lewy body pathology in LRRK2-related Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol 2015;72(1):100–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kestenbaum M, Alcalay RN. Clinical Features of LRRK2 Carriers with Parkinson’s Disease. Adv Neurobiol 2017;14:31–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahamadi M, Mehrotra N, Hanan N, et al. A Disease Progression Model to Quantify the Nonmotor Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease in Participants With Leucine-Rich Repeat Kinase 2 Mutation. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021;110(2):508–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.West AB. Ten years and counting: moving leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 inhibitors to the clinic. Mov Disord 2015;30(2):180–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trinh J, Guella I, Farrer MJ. Disease penetrance of late-onset parkinsonism: a meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol 2014;71(12):1535–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.West AB, Moore DJ, Biskup S, et al. Parkinson’s disease-associated mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 augment kinase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102(46):16842–16847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheng Z, Zhang S, Bustos D, et al. Ser1292 autophosphorylation is an indicator of LRRK2 kinase activity and contributes to the cellular effects of PD mutations. Sci Transl Med 2012;4(164):164ra161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fraser KB, Moehle MS, Alcalay RN, West AB, Consortium LC. Urinary LRRK2 phosphorylation predicts parkinsonian phenotypes in G2019S LRRK2 carriers. Neurology 2016;86(11):994–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fraser KB, Rawlins AB, Clark RG, et al. Ser(P)-1292 LRRK2 in urinary exosomes is elevated in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2016;31(10):1543–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steger M, Tonelli F, Ito G, et al. Phosphoproteomics reveals that Parkinson’s disease kinase LRRK2 regulates a subset of Rab GTPases. Elife 2016;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan Y, Nirujogi RS, Garrido A, et al. R1441G but not G2019S mutation enhances LRRK2 mediated Rab10 phosphorylation in human peripheral blood neutrophils. Acta Neuropathol 2021;142(3):475–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang S, Unnithan S, Bryant N, et al. Elevated Urinary Rab10 Phosphorylation in Idiopathic Parkinson Disease. Mov Disord 2022;37(7):1454–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalogeropulou AF, Purlyte E, Tonelli F, et al. Impact of 100 LRRK2 variants linked to Parkinson’s disease on kinase activity and microtubule binding. Biochem J 2022;479(17):1759–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fuji RN, Flagella M, Baca M, et al. Effect of selective LRRK2 kinase inhibition on nonhuman primate lung. Sci Transl Med 2015;7(273):273ra215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Estrada AA, Liu X, Baker-Glenn C, et al. Discovery of highly potent, selective, and brain-penetrable leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) small molecule inhibitors. J Med Chem 2012;55(22):9416–9433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]