Abstract

Transcriptional pausing aids gene regulation by cellular RNA polymerases (RNAPs). A surface-exposed domain inserted into the catalytic trigger loop (TL) of Escherichia coli RNAP, called SI3, modulates pausing and is essential for growth. Here we describe a viable E. coli strain lacking SI3 enabled by a suppressor TL substitution (β′Ala941→Thr; ΔSI3*). ΔSI3* increased transcription rate in vitro relative to ΔSI3, possibly explaining its viability, but retained both positive and negative effects of ΔSI3 on pausing. ΔSI3* inhibited pauses stabilized by nascent RNA structures (pause hairpins; PHs) but enhanced other pauses. Using NET-seq, we found that ΔSI3*-enhanced pauses resemble the consensus elemental pause sequence whereas sequences at ΔSI3*-suppressed pauses, which exhibited greater association with PHs, were more divergent. ΔSI3*-suppressed pauses also were associated with apparent pausing one nucleotide upstream from the consensus sequence, often generating tandem pause sites. These ‘–2 pauses’ were stimulated by pyrophosphate in vitro and by addition of apyrase to degrade residual NTPs during NET-seq sample processing. We propose that some pauses are readily reversible by pyrophosphorolysis or single-nucleotide cleavage. Our results document multiple ways that SI3 modulates pausing in vivo and may explain discrepancies in consensus pause sequences in some NET-seq studies.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Transcriptional pausing is a regulatory mechanism shared by all cellular DNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RNAPs) (1–3). Upon encountering pause signals during transcript elongation, RNAPs can enter a paused state that delays RNA synthesis by factors of ∼20–1000 (Figure 1) (4,5). A consensus elemental pause (ce-pause) signal has been identified with a sequence motif whose most conserved elements are 5′-g–11G–10t–3g–2Y−1G+1 (–1 corresponds to 3′ end position of nascent RNA) (4,6). Multiple sequence features, including the downstream fork junction, upstream fork junction, DNA-RNA hybrid, and downstream DNA, additively contribute to the strength of an elemental pause (5). The ce-pause sequence was identified in E. coli. Although it affects diverse RNAPs from bacterial to human (4), the consensus sequence has been difficult to discern in NET-seq studies of some organisms; pauses sometimes appear to occur just before instead of just after the consensus Y–1 (7–9).

Figure 1.

Changes in SI3 position modulate transcriptional elongation and pausing. SI3 occupies two major positions during the nucleotide addition cycle (NAC, panel in lower right): closed when the TL is folded and open when the TL is unfolded, also called in and out SI3 positions (top panels; pdb 6rh3 and 6rin, respectively) (75). TL folding occurs upon cognate NTP binding to the active center. Different pause states can form offline from the NAC as illustrated by the pathway to the left. The swiveled, hairpin-stabilized PEC is shown on the left in front and top views (pdb 6asx) (15). Swiveling of SI3 (pink contour in top view) is mediated by jaw–SI3 interaction (upper left panel). The consensus elemental pause sequence derived from genome-scale pause analysis (4) in E. coli is shown in the lower left.

Pausing provides time windows for dissociable transcription factors to bind RNAP, for nascent RNA to fold, for RNAP to backtrack, or for elemental paused elongation complexes (ePECs) to rearrange into other types of transcriptional pauses (1,10,11). Hairpin-stabilized PECs (hs-PECs) form when the nascent RNA folds into a stem–loop secondary structure (pause hairpin, PH) within the RNA-exit channel of RNAP (12). Hs-pauses guide formation of alternative RNA structures, couple RNAP to translating ribosomes, and aid both intrinsic transcription termination and attenuation mechanisms (13,14). Cryo-EM analyses of ePECs and hs-PECs have revealed a global conformational change in RNAP called swiveling that inhibits nucleotide addition (15–17). Swiveling, which is stabilized by PHs, involves rotation by a few degrees of interconnected modules in the PEC, including the clamp, dock, shelf, jaw, and lineage-specific sequence insertion 3 (SI3) in E. coli (15).

SI3 in E. coli contains two sandwich-barrel hybrid motifs (SBHMs) (18). SBHMs are inserted in the catalytic trigger loop (TL) of RNAP of many bacteria phyla except Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Deinococcus-Thermus, Thermotogae and Chloroflexi (18–20) (Supplementary Figure S1). SI3’s location on the surface of RNAP changes in coordination with folding and unfolding of the TL into which SI3 is inserted. Upon TL folding, which greatly promotes catalysis of nucleotide addition (Figure 1), SI3 breaks contact with the RNAP jaw module and contacts the RNAP rim helices (RHs).

Multiple lines of evidence suggest SI3 modulates transcriptional pausing in different ways (15,20–22). SI3 is proposed to be a key connector between RNAP swiveling and TL conformational change in a PECs; SI3–jaw rotates as part of the swivel module and thus stabilizes the unfolded TL (15,20,22). Conversely, SI3 may stabilize the folded TL in pretranslocated PECs, which form on strong ce-pause sequences (16). Deletion of SI3 or disruption of its connection with other swivel-module parts greatly reduces hs-pause strength in vitro (20,22,23). However, deletion of SI3 in viable E. coli cells has been unsuccessful to date, possibly due to SI3 participation in multiple transcription steps (23–25).

Here we describe the construction of a viable SI3-deleted E. coli strain and its use to quantify changes in transcriptional pausing in vivo compared to wild-type RNAP using NET-seq. Consistent with different roles of SI3 in pausing, deletion of SI3 increased pausing at some sites and decreased pausing at others. The ΔSI3-enhanced pause sequences strongly resembled the ce-pause sequence motif. The ΔSI3-suppressed pauses, some of which are known hs-pauses, were associated with a greater likelihood of RNA structure formation at PH locations and with what appears to be pausing one nucleotide upstream of the ce-pause sequence (i.e. pausing at position –2). Our experimental results support multiple roles of SI3 in modulating pausing globally and document how apparent –2 pauses may appear at pause sites that are sensitive to pyrophosphorolysis including during NET-seq sample processing.

Materials and methods

Reagents and materials

Plasmids, oligonucleotides, cell strains are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Oligonucleotides were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Corvalville, IA, USA) and RNA oligonucleotides and NET-seq cDNA library primers were purified with polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). [α-32P]GTP, [α-32P]CTP and [γ-32P]ATP were from PerkinElmer Life Sciences; rNTPs were from Promega (Madison, WI, USA).

Proteins

His-tagged wild-type, ΔSI3 and ΔSI3* RNAPs were purified as described previously (20). Briefly, plasmids harboring rpoA, rpoB, rpoC-His10 and rpoZ were transformed into BL21(DE3) cells. Overnight cultures (5 ml) were inoculated into 1 l LB medium with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) and the cells were grown at 37°C, 220 rpm until apparent OD600 reached 0.4. Then, 1 mM IPTG was introduced to induce protein expression for 3 h before harvesting. The cells were resuspended in 50 ml Lysis Buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 5% glycerol, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-ME, 10 mM DTT, 100 μg PMSF/ml and 1 tablet of protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]). Cells were lysed by sonication and clarified by centrifugation at 11,000 × g, 4°C for 15 min. A crude precipitation of RNAPs were obtained by adding PEI to 0.6% (v/v) to the supernatant followed by centrifugation at 11,000 × g, 4°C for 15 min. Contaminants were extracted from the pellet by crushing with a tissue homogenizer and washing with 25 ml PEI Wash Buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 μM ZnCl2, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT). Crude RNAPs were extracted from the pellet by crushing with a tissue homogenizer and washing with 25 ml PEI Elution Buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 μM ZnCl2, 1 M NaCl, 10 mM DTT). Proteins were precipitated by adding 0.37 g (NH4)2SO4 per milliliter of eluted solution. Precipitated RNAPs were resuspended in 35 ml His-column Buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole and 5 mM β-ME) and loaded into HisTrap FF 5 ml column. Proteins were washed with His-column Buffer and eluted with the same solution containing 30 ml gradient increasing imidazole (5–500 mM imidazole) in His-column Buffer. Samples containing RNAPs were pooled and adjusted to 200 mM final NaCl. The protein was then loaded into HiTrap Heparin HP 5 ml column to remove contaminants including residual nucleic acids. The protein was washed with Wash Buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 5% glycerol, 25 mM EDTA, 5 μM ZnCl2, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT) and eluted with Elution Buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 5% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 μM ZnCl2, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT). Fractions containing pure RNAPs were pooled and dialyzed in RNAP Storage Buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.9, 25% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 20 μM ZnCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM DTT) and stored at –80°C.

Native rpoC modification with no-SCAR

We followed the published protocols (26,27) to delete SI3 from E. coli genome. A plasmid with a Tet-inducible Cas9 protein (pCas9cr4) and a plasmid (pYB301) harboring an Ara-inducible λ-Red system plus an SI3-targeting sgRNA (target sequence: TTACGCGTCAGACCGACGAA) were sequentially transformed into an E. coli K-12 MG1655 (28). The cells were cultured at 30°C in SOB medium (2% w/v tryptone, 0.5% w/v yeast extract, 10 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MgSO4) containing 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 50 μg/ml spectinomycin until apparent OD600 reached 0.4. λ-Red was induced by adding 0.2% l-arabinose and incubating at 30°C for 15 min. The cells were chilled quickly on ice and made competent for electroporation using reported methods (27). A 202-bp double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) recombination template of a ΔSI3-rpoC was PCR-amplified from an existing plasmid (pRM759) and gel-purified. The del27 dsDNA template was cloned from pRM839 and the ΔSI3* dsDNA template was cloned from pYB205. The competent cells were transformed with 1 μg of dsDNA template, plated on LB plates containing 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 50 μg/ml spectinomycin and 200 ng/ml anhydrotetracycline, and grown at 30°C. The SI3 region in the genome was screened using colony PCR and primers flanking the SI3 insertion site and verified by Sanger sequencing. The two plasmids were cured as described (27). P1 phage grown on this strain was then used to transduce MG1655 thiC::Tn10 to thi+, yielding RL4010 (MG1655 SI3*). In parallel, MG1655 thiC::Tn10 was transduced to thi+ using P1 grown on unmodified MG1655, yielding RL4011 (control MG1655 rpoC+ strain for comparison to RL4010). RL4010 and RL4011 were used as ΔSI3* and WT strains for growth and cell-size tests.

E. coli cell microscopic imaging and cell size quantification

ΔSI3* and WT cells were cultured in MOPS rich defined medium (RDM) with 0.2% glucose to early log-phase (apparent OD600 ∼ 0.4). Cells (1 μl) were spotted on a custom-made 15 mm × 15 mm × 2 mm 1% agarose pad to immobilize the cells and covered with glass coverslips. Cells were imaged on an Olympus IX-83 inverted microscope with a 60× phase contrast objective. Raw images were adjusted with brightness/contrast in ImageJ software (29) and the cell area was analyzed with ‘Analyze particle’ module. The cell area distribution histograms were fitted with sigma distribution curves.

rpoC complementation

To test if modified rpoC could support cell growth, plasmids harboring full-length wildtype. ΔSI3, ΔSI3* or β′A941T rpoC expressed from a trc promoter were transformed into strain RL602 (30) in which expression of native rpoC is inhibited at >37°C. Cells were cultured at 37°C until log-phase, diluted sequentially, spotted on LB agar plate containing 0.5 mM IPTG, and incubated at 39°C for 16 h to score cell growth.

NET-seq strain construction

We generated an rpoC(ΔSI3*) strain with a C-terminal 3X FLAG tag and adjacent kanamycin-resistance marker by plasmid-mediated recombination as described previously (4,31). The plasmid pYB403 was transformed into strain RL324 and double-crossover recombinants were selected on LB-Kan plates (50 μg kanamycin/ml). Colonies were restruck on LB-Kan plates for several passages to ensure plasmid loss, which was confirmed by loss of ampicillin resistance. Replacement of rpoC with the rpoCΔSI3*::3X FLAG was confirmed by PCR-Sanger sequencing. P1 phage lysate grown on this strain was then used to transduce RL3000 to give strain RL4002.

In vitro transcription assay

In vitro transcription assays to measure elongation and pausing were performed as described previously (20), with minor modifications. For elongation assays, pre-assembled nucleic-acid scaffold (5 μM RNA, 10 μM template strand DNA [t-DNA]) was incubated with E. coli RNAP core enzyme in Elongation Buffer (20 mM Tris-acetate, pH 8.0, 40 mM KOAc, 5 mM Mg(OAc)2, 1 mM DTT) with 0.5 μM RNA, 1.0 μM t-DNA, 1.5 μM RNAP for 15 min at 37°C. Non-template strand DNA (nt-DNA) was added to 1.5 μM and the mixture was incubated for an additional 15 min at 37°C. The estimated concentration of assembled EC was 500 nM. To incorporate 32P, ECs were diluted to 150 nM with Elongation Buffer and 50 μl was incubated with 10 μCi [α-32P] GTP (3000 Ci/mmol) for 5 min at 37°C. Labeled ECs were then extended to form A26 halted ECs by incubating with ATP and GTP (83 μM each final) for 5 min at 37°C.

To ligate ECs to the 2.2 kb DNA template (PCR-amplified from plasmid pRL785), 5 nM A26 ECs were incubated with 15 nM purified DNA template and T4 DNA ligase (NEB; 25 unit/μl final) in T4 DNA ligase buffer (NEB) at 16°C for 2 h. Further reconstitution was then blocked by incubation with heparin (0.1 mg/ml final) for 5 min at 37°C. To re-start elongation, an equal volume of template-ligated EC was mixed with 4 NTPs (1 mM each). Reaction samples were withdrawn at 20 s and mixed with an equal volume of Stop Buffer (8 M urea, 50 mM EDTA, 90 mM Tris-borate buffer, pH 8.3, 0.02% bromophenol blue, 0.02% xylene cyanol). RNAs in all samples were resolved by denaturing PAGE (8% polyacrylamide, 19:1 acrylamide:bis-acrylamide, 45 mM Tris-borate, pH 8.3, 1.25 mM Na2EDTA, 8 M urea), exposed to a Storage Phosphor Screen (GE Healthcare) and scanned with Typhoon PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare). An 32P-labeled pBR322 MspI digested DNA ladder (NEB) was run on the gel for size reference.

The gels were quantified using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare). To estimate the averaged elongation rates, the intensities of RNAs longer than 66 nt (the 66 nt band was generated by unligated ECs) after 20 s extension with 1 mM NTPs were determined and average elongation rates were calculated from the average sizes of these RNAs in three independent assays.

For scaffold-based pause assays, pre-assembled nucleic-acid scaffolds (5 μM RNA, 10 μM template strand t-DNA) were incubated with E.coli RNAP core enzyme in Transcription Buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 50 mM potassium glutamate, 10 mM magnesium glutamate, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT and 5 μg acetylated BSA/ml) with 0.5 μM RNA, 1.0 μM t-DNA, 1.5 μM RNAP for 15 min at 37°C. Nt-DNA was added to 1.5 μM and the mixture was incubated for an additional 15 min at 37°C. Further reconstitution was then blocked by incubation with heparin (0.1 mg/ml final) for 5 min at 37°C. ECs were incorporation labeled using appropriate combinations of [α-32P]NTP and unlabeled NTPs (Figures 3B–D). The his hs-pause assay (Figure 3B) was performed by incubating 150 nM reconstituted EC (in 100–500 μl) with 10 μCi [α-32P] CTP (3000 Ci/mmol) for 3 min at 37°C. The labeled ECs were then extended to the pause site by adding CTP and UTP to 2 μM each, and a pause hairpin mimic was then generated by incubation with of antisense RNA (asRNA) oligo (2 μM final) for 5 min at 37°C. Pause escape was initiated by addition of GTP to 10 μM and samples from various time points were quenched with Stop Buffer prior to analysis by 15% PAGE. The consensus elemental pause assay (Figure 3C) was performed by incubating 150 nM reconstituted EC (in 100–500 μl) with 10 μCi [α-32P] GTP (3000 Ci/mmol) for 3 min at 37°C. The labeled ECs were then extended to the –1 pause site by adding GTP to 2.5 μM. Pause formation and escape was initiated by addition of GTP and CTP to 100 μM. The new hs-pause assay (Figure 3D) was performed by incubating 150 nM reconstituted EC (in 100–500 μl) with 10 μCi [α-32P] GTP (3000 Ci/mmol) for 3 min at 37°C. The labeled ECs were then extended to the pause site by adding GTP and ATP to 2 μM each, and a pause hairpin mimic was then generated by incubation with of antisense RNA oligo (2 μM final) for 5 min at 37°C. Pause escape was initiated by addition of UTP to 10 μM.

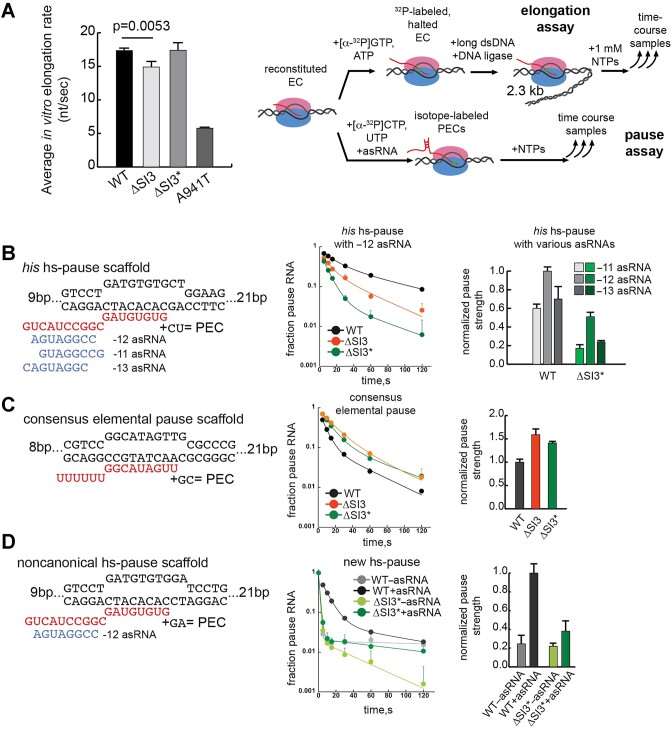

Figure 3.

ΔSI3* RNAP exhibits average elongation rate similar to WT but pause kinetics similar to ΔSI3 RNAP. (A) Left panel, average elongation rates of various RNAPs determined by in vitro transcription assay. Results are mean ± SD (n = 3); P value is from a two-tailed t-test. Right panel, schematic diagram of the in vitro elongation and pause assays. For elongation assays, the 32P-labeled, halted EC was ligated to a 2.3 kb DNA template before re-initiating elongation by addition of all 4 NTPs (1 mM each). Elongation rates were calculated from the average change in RNA lengths over time. For pause assays, the PEC was reconstituted on pause scaffolds and the kinetics of pause escape were measured. Representative gel images for panels (A)–(D) are shown in Supplementary Figure S7. (B) ΔSI3* RNAP his hs-pause assay. From left to right: the pause scaffold sequence and location of PH mimics formed with asRNAs; change in fraction paused RNA vs. time for WT, ΔSI3, and ΔSI3* RNAPs; and comparison of pause strengths for WT and ΔSI3* RNAPs for different PH mimic locations relative to the pause RNA 3′ end. (C) ΔSI3* RNAP ce-pause assay with panels as described for (B). (D) ΔSI3* RNAP pause assay using a hs-, non-consensus pause sequence (pause RNA 3′ rA) with panels as described for (B).

To analyze pause kinetics, the pause fraction change through time was fit with bi-exponential decay equation:

|

F fast and Fslow represent the fraction of RNA species entering the slow and fast escape phase and kfast and kslow describe their escape rates. The pause strength (τ) was calculated as:

|

For promoter-based pause assays, the ∼400 bp transcription templates were PCR-amplified from pre-constructed plasmids (see Supplementary Table S1) followed by spermine precipitation to recover DNA free of primers (32). Transcription holoenzyme was formed by mixing 5 μM E. coli σ70 with 1 μM RNAP core enzyme in Transcription Buffer (see above) for 20 min at 37°C. The holoenzyme was incubated with other transcription components [50 nM holoenzyme, 40 nM DNA template, 0.5 unit/μl RNase inhibitor (Promega), 150 μM ApU dinucleotide, 10 μCi [α-32P] GTP (3000 Ci/mmol), 5 μM ATP, 5 μM UTP and 2 μM GTP] to form 32P-labeled A26 halted ECs for 10 min at 37°C. Further reconstitution was then blocked by incubation with heparin (0.1 mg/ml final) for 5 min at 37°C. If used, NusA was added at 200 nM and incubated for an additional 5 min at 37°C. To restart transcription, A26 halted ECs were mixed with 100 μM each NTP, incubated at 37°C, and samples were removed at specified times and combined with an equal volume of Stop buffer. Higher NTPs (1 mM each) were added after the time course and incubated for an additional 1 min at 37°C to generate a chase sample. To prevent RNA 2° structure interference by A26 sequence, 2 μM of the antisense DNA oligo (5′-ATACAACCTCCTTACTACAT, #15363) that specifically anneals with A26 RNA was included in the NTP mix. In assays to disrupt candidate hs-pauses with asDNA oligos, asDNA oligos were used at 2 μM final concentration. To map the exact lengths of pause RNAs, RNA sequencing ladders were generated by mixing 5 μl of halted A26 complex with 0.5 μl of sequencing ladder mix (250 μM 3′-deoxyATP/UTP/GTP/CTP and 250 μM each rNTP) and incubating at 37°C for 3 min followed by quenching with 5 μl of Stop buffer. The pause RNAs were electrophoresed next to ladders of RNAs with 3′ A, U, G or C through 12% PA gels, imaged, and quantified as described above.

NET-seq library preparation

Cell culture and harvest

A single colony of the 3X FLAG-tagged RNAP E. coli NET-seq strains was inoculated into MOPS rich defined medium with 0.2% glucose (RDM) (33) and 50 μg/ml kanamycin for overnight growth at 37°C. A 2.5-ml portion of the overnight culture was inoculated into 0.5 l RDM with 50 μg kanamycin/ml (freshly prepared and sterilized with 0.22 μ filter). The cultures were grown in 2 L Erlenmeyer flasks on an orbital shaker at 200 rpm and 37°C until cell density reached early log-phase (apparent OD600 ∼0.4) and then rapidly filtered at 37°C through a 0.45 μ cellulose filters. Cells were scrapped from the filter with a spatula and plunged into liquid nitrogen. Frozen cells were stored at –80°C before processing. Biological triplicate samples were collected for each NET-seq strain. B. subtilis cells bearing a 3X FLAG tag on rpoC (RL3116) for use as a spike-in quantitation control were grown in LB with 7.5 μg kanamycin/ml at 37°C. B. subtilis cells were recovered by centrifugation at 4000 × g for 10 min, resuspended in 10 ml ice cold sterile PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 2 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) containing 20% glycerol and one-half tablet of protease inhibitor mix (Roche cOmplete) at 1.24 × 1010 CFU/ml, and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Nascent RNA extraction

Frozen cells harvested from 0.5 L cell culture were combined 0.5 ml B. subtilis spike-in cells per apparent OD600 unit of E. coli (∼6.2 × 108 CFU spike-in cells per ODE.coli, resulting in approximately 3.4% B. subtilis cells for WT samples and 1.4% for ΔSI3* samples) and 400 μl frozen lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 0.4% Triton X-100, 0.1% NP-40, 100 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM MnCl2, 250 Unit RNaseIn (Promega), 1X protease inhibitor cocktail, 0.4 mg/ml puromycin). The mixture was pulverized in a Retsch MM400 Mixer Mill (canisters pre-cooled in liquid nitrogen) 6 times at 15 Hz for 3 min. The lysate was resuspended on ice in 5 ml of lysis buffer by gentle pipetting. RQ1 DNase I (110 Unit total, Promega) was added and incubated for 15 min on ice. The reaction was quenched with EDTA (25 mM final) to release ribosomes from the transcripts and chelate Mg2+ to inactivate RNAP. The lysate was then clarified at 4°C by centrifugation at 25 000 × g for 10 min and incubated with 0.5 ml anti-FLAG M2 affinity resin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 h at 4°C. The resin was washed 4 times with 10 ml Wash Buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 0.4% Triton X-100, 0.1% NP-40, 300 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA) at 4°C, and the ECs were then eluted with 600 μl Elution Buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 0.4% Triton X-100, 0.1% NP-40, 2 mg/ml FLAG peptide (Sigma-Aldrich)). Nascent RNA was extracted from the eluate with miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer's instructions. The nascent RNA sample was further purified by EtOH precipitation, dissolved in DEPC-treated water, and stored at –80°C.

Preparation of cDNA libraries

NET-seq library preparation was performed following published procedures (34) with minor changes. The adaptor oligo (#14047, 6 μM) was 5′ adenylated by incubating with 80 μM ATP, 6 μM Mth RNA ligase (NEB), 25% PEG 8000 in 1X NEB Buffer 1 at 65°C for 4 h, then 85°C for 5 min. Nascent RNA (16.7 ng/μl, 1.5 μg per sample) was ligated to the adaptor by incubating with 1X T4 RNA ligase buffer (NEB), 25% PEG 8000, 6.7 U/μl T4 RNA ligase 2, truncated (NEB), 2 μM adaptor, 1.3 U/μl RNaseIn at 37°C for 3 h. The ligation was stopped by adding EDTA to 16 mM. The adaptor-ligated RNA was alkaline fragmented by incubating with 6 mM Na2CO3, 44 mM NaHCO3, 1 mM EDTA at 95°C for ∼35 min (time varied depending on the freshness of the alkaline solution) and the RNA was precipitated with equal volume of isopropanol and 0.3 M NaOAc (pH 5.5) using 15 μg Glycogen-Blue (Thermo Fisher) as a co-precipitant. The fragmented, adaptor-ligated RNA was electrophoresed through a 15% polyacrylamide TBE urea (90 mM Tris base, 90 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA, 8 M urea) gel (Novex, Thermo Fisher) and the 50–100 nt RNAs were excised and extracted as described previously (34). The RNA was reversely transcribed into cDNA in 1X First Strand Buffer (Thermo Fisher), 0.5 mM dNTPs, 0.3 μM RT adaptor (#14637), 0.6 unit/μl SuperaseIn, 5 mM DTT, Superscript III (Thermo Fisher; 10 U/μl) at 50°C for 60 min. RNA template was removed from the cDNA by incubation in 0.1 M NaOH at 95°C for 20 min followed by neutralization with 0.1 M HCl. The cDNA was electrophoresed though a 10% polyacrylamide TBE urea gel (Novex, Thermo Fisher) and the 100–200-nt DNAs were excised and extracted as described previously (34). The cDNA library was circularized by incubation with 1X Reaction Buffer (Lucigen), 50 μM ATP, 2.5 μM MnCl2, CircLigase (Lucigen; 5 U/μl) at 60°C for 1 h and then at 80°C for 10 min. The cDNA libraries were amplified with Q5 DNA polymerase (NEB) using PCR conditions recommended by the manufacturer and dual-indexed primers for the NovaSeq6000 (Illumina) sequencing platform, and then subjected to 150-nt paired-end sequencing.

NET-seq data analysis

NET-seq data analysis was performed using open-source programs written in Python (35) and custom scripts written in R 4.1.0 (36). All custom scripts are available in the Zenodo repository (doi: 10.5281/zenodo.10159358). Adaptor sequence in raw NET-seq reads was removed with Cutadapt (37) and aligned to E. coli MG1655 reference genome (NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_000913.3) with Bowtie (38). Unwanted reads in ribosomal RNA regions and tRNA regions were removed with SAMtools (39) and surviving reads were converted to BED format with BEDTools (40). Each aligned NET-seq read was trimmed to retain only the first 15 nucleotides which represents the active transcription bubble of each RNAP starting from the 3′ end. The total read numbers and 3′ end read numbers in genome positions were quantified with BEDTools.

To scale reads among strains and replicates, 3′ end read counts (Rraw) were scaled according to the amount of E. coli cell genomic DNA in harvested material above (ME. coli, μg genomic DNA), the B. subtilis spike-in cell number (Nspike-in), and the reads (Rspike-in) unambiguously aligned to B. subtilis genome (NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_000964.3) using the following formula.

|

The mass of E. coli genomic DNA instead of the E. coli cell number was used to generate the scaling factor because number of elongating and paused RNAPs should be proportional to the total amount of DNA template whereas the genome copy number may not be identical for the two NET-seq strains in mid-log phase. We found differences in DNA mass per cell between WT and ΔSI3* strains.

To determine the relationship between apparent OD600 and DNA mass for the two NET-seq strains, cells cultured using the NET-seq protocol were harvested at two different apparent OD600 values in mid-log phase by rapidly mixing 0.5 ml culture with an equal volume of ice-cold methanol to stop cell growth. The cells were spun down and lysed in TES solution (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 2% SDS) at 65°C for 5 min. The lysate was extracted with equal volume of phenol:chloroform:IAA (Invitrogen) and the supernatant was sampled to determine genomic DNA concentration with Qubit dsDNA BR assay (Invitrogen). The following linear functions with coefficients determined from these measurements were used to calculate DNA amounts (in μg per 1 ml culture).

|

ME. colivalues of NET-seq samples were calculated based on the strain, the apparent OD600 value of each sample at harvest, and the culture volume harvested (Supplementary Table S2).

We identified pause sites from non-rRNA regions using a five-round sliding window strategy in which a position was designated a pause if its read count was greater than 4 standard deviations higher than the mean for non-zero counts in window (centered at the position) from –100 to + 99 (z > 4). For rounds 2–4, pause positions identified in the preceding round or rounds were removed and the sliding-window z-score calculation was repeated to identify additional pause sites that might have been masked in the preceding round by nearby strong pause signals. Pause sites that were not identified in all three biological replicates were removed from the final data sets. Additionally, putative pauses corresponding to tRNAs, or sRNA 3′ ends were removed (Supplementary Table S3). Pauses were sorted into various classes based on effects of ΔSI3* (Supplementary Figure S2; Supplementary Table S4).

We estimated pause strength as the read number corresponding to a pause site RNA 3′ end divided by the number of 15-nt reads covering the location. We estimated changes in pause strength between WT and ΔSI3* strains by calculating the ratio of pause strength numbers for the two strains at a given pause position.

For pause hairpin prediction, RNA sequences from –50 to –11 positions (–1 corresponding to the 3′ end) were used for minimum free energy secondary structure prediction using the Vienna RNA package 2.0 (41). Stem loop structures with at least 4 base pairs in the stem region (allowing at most 1 mismatch inside the stem) were designated as putative pause hairpins (PH).

β-Galactosidase activity assay

Plasmids with lacZ fusion reporters were transformed into VH1000 E. coli cells [Δ(lacI–lacZ)]. Fresh colonies were inoculated into MOPS RDM with 0.2% glucose for overnight growth. On the next day, 10 μl of overnight culture was mixed with 190 μl RDM in a 96-well plate and shaken at 600 rpm at 37°C for 2–3 h until reaching mid-exponential phase. The cells were resuspended using a multichannel pipettor before recording apparent OD600 values on a plate reader (Tecan M1000). 10 μl A portion (10 μl) of cells was permeabilized by thoroughly mixing with 110 μl lysis buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.005% SDS) and 4 μl chloroform at room temperature. The β-galactosidase reaction was initiated by addition of 24 μl ortho-Nitrophenyl-β-galactoside (ONPG, 4 mg/ml) and stopped by addition of 60 μl 1M Na2CO3 at the reaction time (t, min) recorded. Absorbance at 420 nm (A420) and 550 nm (A550) was measured using a Tecan plate reader (M1000). β-galactosidase activity was calculated using the following formula.

|

When used, bicyclomycin was added to cultures to 20 μg/ml as the final concentration.

Results

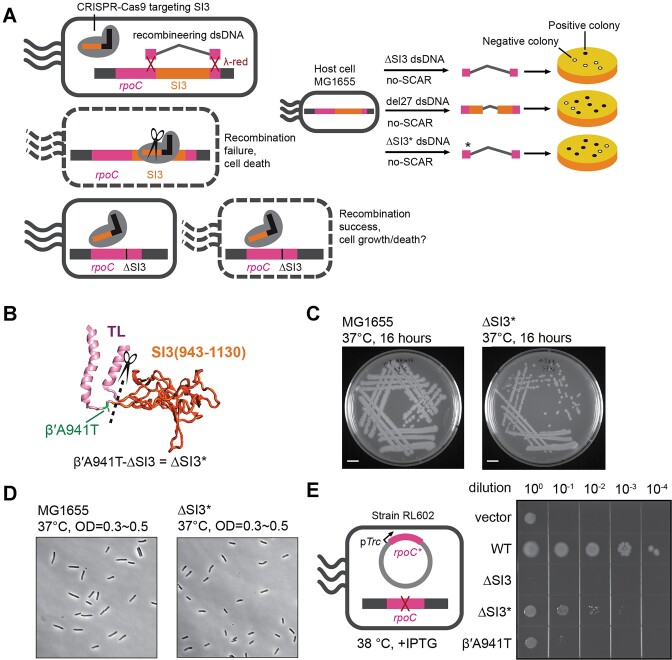

A viable E. coli strain lacking SI3

Deletion of SI3 from E. coli RNAP (ΔSI3; β′Δ[R943–G1130]) decreases the dwell time of the his hs-pause ∼3-fold in vitro (21,22) but is inviable in vivo (23). To study the effects of ΔSI3 RNAP on pause kinetics in vivo, we sought to delete SI3 from the E. coli genome using Scarless Cas9-Assisted Recombineering (no-SCAR) (27). This method combines λ-red recombination with CRISPR-guided selection, allowing gene editing without selection markers. As a positive control, a viable strain with an SI3 truncation, del27 (β′Δ[T1045–L1053]) (42) was constructed in parallel (Figure 2A). We easily obtained positive colonies of the del27 strain (25 out of 46 screened colonies), which were verified by PCR-sequencing. In contrast, we isolated only a single colony (1 out of 177 screened colonies) carrying the full-length SI3 deletion. The recovered deletion also encoded a single amino-acid substitution, β′A941T, in the ΔSI3 TL (Figure 2B). For conciseness, we refer to β′A941T-ΔSI3 as ΔSI3* hereafter. To confirm that β′A941T is required for growth of ΔSI3* E. coli, we re-performed no-SCAR recombineering in parallel using ΔSI3 and ΔSI3* (β′A941T-ΔSI3) recombination targets. Consistent with a requirement of the suppressor substitution β′A941T for viability, 36 of 48 colonies isolated using the ΔSI3* (β′A941T-ΔSI3) target contained ΔSI3* but none of the 48 colonies screened using the ΔSI3 target contained the deletion. However, ΔSI3* strains produced smaller colonies than wild type (E. coli K-12 MG1655) when grown on rich medium agar plates at 37°C (Figure 2C). In liquid culture, ΔSI3* grew exponentially at a rate similar to wild type in rich medium (determined by apparent OD600) but with significantly smaller cell sizes (Figure 2D and Supplementary Figure S3A-C).

Figure 2.

Construction of an SI3-deleted E. coli strain. (A) Left panel, No-SCAR method to construct SI3 deletion. The genomic sequence encoding SI3 was targeted using CRISPR-Cas9 and recombined with a ΔSI3 DNA fragment lacking the targeted sequence using λ-Red-mediated recombination. Right panel, schematic comparison of outcomes for different DNA fragments recombined with SI3 region. Only one colony was obtained with ΔSI3 and this colony encoded a spontaneous β′A941T substitution (ΔSI3 plus β′A941T, called ΔSI3*). DNA fragments encoding ΔSI3* or del27 (42) yielded large numbers of positive colonies (black dots). (B) The location of β′A941T in the TL. (C) Colony size comparison for WT and ΔSI3* strains. (D) Microscopy images of WT and ΔSI3* cells in log-phase, bar representing 5 μm. (E) Complementation of rpoC(temperature-sensitive) by various rpoC genes. Plasmids harboring IPTG-inducible rpoC gene variants were expressed in E. coli strain RL602 (23), in which rpoC expression is suppressed at ≥38°C.

To probe the effect of the β′A941T substitution alone, we exogenously expressed wild-type, ΔSI3, ΔSI3* and β′A941T rpoC genes from a plasmid in E. coli strain RL602. RL602 is unable to express native rpoC at >37°C (30). Unexpectedly, β′A941T alone could not support cell growth, but produced viable colonies when combined with ΔSI3 (ΔSI3*) (Figure 2E). Consistent with previous results (23), ΔSI3 rpoC also could not support cell growth. We conclude that a ΔSI3 strain is viable only when accompanied by a suppressor substitution like β′A941T.

ΔSI3* RNAP exhibited changes in elongation and pausing in vitro

To compare the transcriptional properties of β′A941T, ΔSI3 and ΔSI3* to WT, we purified recombinant RNAPs and conducted in vitro transcription elongation assays with an ∼2.3 kb DNA template (20,43). Both β′A941T and ΔSI3 RNAPs exhibited decreased elongation rates (33% and 86% of WT, respectively). In contrast, ΔSI3* RNAP exhibited an elongation rate indistinguishable from WT (Figure 3A). We postulate that the impaired average elongation rate of ΔSI3 RNAP reflects aberrant TL conformational dynamics that alter the balance between folded and unfolded states. Such imbalance may contribute to lethality. β′A941T may function as a suppressor by also altering TL dynamics in a way that itself is inviable but becomes viable when combined with ΔSI3 by restoring a balance of folded and unfolded TL states. The β′A941T substitution is not evident in TL sequences from bacteria lacking SI3 (Supplementary Figure S1). However, its position and the two adjacent residues (AA941S in E. coli) undergo major conformational changes during TL folding–unfolding and are both bulkier and more functionalized on average in TL sequences lacking SI3 (TAK versus VAG; Supplementary Figure S1). It also is possible that ΔSI3 alters other key RNAP processes (e.g. initiation, termination or proofreading) and that β′A941T could affect these processes.

We next asked if ΔSI3* RNAP exhibited reduced hs-pausing like ΔSI3 RNAP. We found that ΔSI3* RNAP decreased the his hs-pause more than ΔSI3 RNAP (∼27% versus ∼50% of WT RNAP pause strength, respectively; Figure 3B, middle panel). PHs stimulate pausing when the PH stem extends to –13, –12 or –11 (the position in PH stem closest to the RNA 3′ end, which is –1) (1,44). We used different antisense RNA oligos to mimic PHs formed at the –11, –12 and –13 positions. ΔSI3* RNAP reduced pause strength for all three by factors of ∼2–3 (Figure 3B, right panel); the –12 PH mimic gave the greatest pause stimulation. We conclude that, like ΔSI3 RNAP, ΔSI3* RNAP inhibits hs-pauses.

SI3 is known to mediate effects of PHs via swiveling, so this effect of ΔSI3* is as expected. In contrast, the ce-pause appears to favor a pretranslocated rather than swiveled state (16). Thus, we next probed how ΔSI3* RNAP responds to a ce-pause signal. ΔSI3* RNAP increased ce-pause strength (1.4-fold greater than wild type) (Figure 3C), in contrast to its reduced hs-pausing. We conclude that ΔSI3* also mimics ΔSI3 in increasing ce-pausing possibly by increasing folded-TL stabilization of the pretranslocated ce-PEC (16).

As a final check of ΔSI3* in vitro, we verified whether it inhibits PH effects at sites distinct from the ce-pause. The his hs-pause exhibits elemental pausing when the PH is ablated (12). Therefore, we asked how ΔSI3* RNAP affects a his hs-pause mutant with little or no pausing in the absence of the PH. For this purpose, we replaced the his pause 3′ rU with rA, changed the downstream DNA sequence, and used a –12 PH mimic oligonucleotide (asRNA) to control PH formation. Without the asRNA, this scaffold does not trigger detectable pausing for WT RNAP (Figure 3D). Addition of an asRNA to form the –12 PH mimic caused measurable pausing by WT RNAP but not by ΔSI3* RNAP. This result confirms that ΔSI3* RNAP reacts differently to hs-pauses vs. ce-pauses and that ΔSI3* reduces pausing solely dependent on PH-induced swiveling.

ΔSI3* caused global changes in RNAP pausing profiles

To ask how ΔSI3* affects different classes of pause sites in vivo, in particular hs-pauses, we next used NET-seq to catalog pauses and apparent pause strengths in wild-type and ΔSI3* strains. To create strains for NET-seq, we used a different recombination method to modify and FLAG-tag native rpoC (31). This strain (rpoCΔSI3*::3X FLAG; ΔSI3*-NETseq strain) also exhibited smaller colonies than wild-type (rpoC::3X FLAG; WT NET-seq strain), consistent with the phenotypes of the strains constructed using the no-SCAR method (Supplementary Figure S3D).

We performed NET-seq on the WT and ΔSI3* NET-seq strains in biological triplicate using a modification of the previously described method (4) that enabled quantitative comparisons of global pause patterns between strains. To enable scaling of read counts among different samples and strains, we added a ‘spike-in’ of 3X FLAG-tagged rpoC Bacillus subtilis cells to samples prior to cell homogenization (see Materials and Methods). Uniformly trimmed reads (15 nt from 3′ ends) were mapped to the E. coli and B. subtilis genomes. After scaling, the 3′-end reads for a given template position were proportional to the number of RNAPs located at the site (Figure 4A, right part). We observed much greater variation between WT and ΔSI3* signals than between biological replicates for normalized 3′ end reads (Figure 4B). These results indicate that ΔSI3* globally altered RNAP distribution among genomic positions. These ΔSI3* effects were immediately evident at specific loci where ΔSI3* either enhanced or decreased pausing compared to WT at different positions (Figure 4C). Interestingly, these differences were not seen in rRNA genes (Figure 4B), where pausing is known to be suppressed by antitermination factors (45). These results confirm that the ΔSI3* RNAP alters transcriptional pausing globally in vivo.

Figure 4.

ΔSI3*-induced changes in global pause profiles determined by NET-seq. (A) Pipeline for quantitative NET-seq library preparation and data analysis. To enable quantitative comparisons of pausing between WT and ΔSI3* strains, a B. subtilis strain was used as spike-in control (∼6.2 × 108B. subtilis colony forming units per apparent OD600E. coli). (B) The consistency of NET-seq reads in non-rRNA region and rRNA region between datasets represented by Pearson's coefficient (r). (C) Comparison of NET-seq reads between ΔSI3* and WT datasets in the his operon leader region. Numbers 1 to 6 represent alternatively pairing RNA segments in the attenuation control region (1:2–3:4–5:6 forming the termination configuration and 1–2:3–4:5–6 forming the antitermination configuration). (D) Schematic diagram of pause site detection and numbers of pause signals in WT and ΔSI3* datasets. Overlapping region represents pause sites detected in both datasets.

The NET-seq results reveal numerous genome-wide loci with increased and decreased 3′ read signals in the ΔSI3* strain. To catalog these pause sites statistically, we used a sliding window algorithm to assign pause sites as locations with a normalized 3′-end count >4 standard deviations greater than the mean of all the non-zero reads within a +99/–100-bp window (z> 4; Figure 4D; see Materials and methods). This pause-calling method yielded ∼43,000 pauses in non-ribosomal RNA operons for WT E. coli and ∼53,000 for the ΔSI3* strain, comparable to published pause densities (4). We then applied a cutoff of ≥40 average normalized counts, yielding 10,700 WT pauses in dataset and 14,230 ΔSI3* pauses (Figure 4D). Only 5,259 sites were found in both the ΔSI3* and WT datasets; ΔSI3* reduced some WT pauses (5,441) to z< 4 and many ΔSI3* pauses were not significant for WT.

SI3 exerts opposite effects on two types of pauses in vivo

To assess quantitatively how ΔSI3* RNAP alters pause strength, we calculated a pause index for each of the 10,700 WT and 14,230 ΔSI3* pause sites. The pause index is defined as the site's normalized 3′-end counts divided by the number of all 15-nt normalized reads that include the position (Figure 5A) (46). This approach corrects for differences in NET-seq signals that arise from differences in gene expression levels and provides a measure of pause strength that is unaffected by global changes in pausing. Although these pause index values are not a direct measure of pause strength, changes in the values provide a useful measure of changes in pause strengths caused by RNAP alteration in different strains. Similar to normalized NET-seq reads (Figure 5B), pause indices were much more divergent between ΔSI3* and WT strains than between replicates (Figure 5B) and this divergence was not evident in ribosomal RNA operons in which pausing is suppressed by antitermination factors (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Compasion of pause strengths between WT and ΔSI3* datasets using pause indices. (A) Calculation of pause indices. Dark colored squares represent 3′ ends of the mapped reads. (B) 3′-end pause index comparisons between WT biological replicates and between WT and ΔSI3* datasets. (C) 3′-end pause index comparisons between WT and ΔSI3* datasets in non-rRNA regions and in the rRNA region. (D–G) Top panels, volcano plots of false-discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P values versus pause index ratios of the WT and ΔSI3* datasets at WT-specific pause sites, all WT pause sites, all ΔSI3* pause sites and ΔSI3*-specific sites, respectively. Blue dots represent pause sites with statistically significant decreased pause indices in ΔSI3* versus WT. Orange dots represent pause sites with statistically significant increased pause indices in ΔSI3* versus WT. Index change thresholds are marked with vertical dotted lines and the P value threshold (10, 4) is marked with the horizontal dotted line. Middle panels, Venn diagrams of pause sites represented in the volcano plots (slashed regions). Bottom panels, sequence logos of the corresponding regions in the volcano plots.

To categorize pauses changed by ΔSI3* at the 10,700 WT pause sites, we used a two-sample Z proportion test to assess whether ΔSI3* pause strength differed significantly from WT (P< 10–4). Using the fold change threshold of ΔSI3*/WT ≤ 0.8 or ≥ 1.25, we found 4,491 pauses significantly affected by ΔSI3* (Figure 5D, E). We used ΔSI3*/WT ≤ 0.8 as a threshold for suppressed pausing because 0.8 was the smallest change of pause strength among several known hs-pause sites in our NET-seq dataset (Figures 5E and S3A, B). We used ΔSI3*/WT ≥ 1.25 as a symmetric threshold for increased pausing to detect pause sites enhanced by ΔSI3* (e.g. resembling the ce-pause signal enhanced 1.4-fold by ΔSI3* in vitro; see Figure 3C). Overall ΔSI3* changed ∼42% of WT pauses enough to merit further investigation, with 3,134 decreased and 1,357 increased (Tables S5 and S6). We also examined the pause indices for sites detected in the ΔSI3* strain. Consistent with the analysis of WT sites, most ΔSI3* pauses were suppressed rather than enhanced in the WT strain (Figures 5F, G). These results confirm that SI3 modulates pausing globally both positively and negatively.

Since ΔSI3* enhanced the pause strength of the ce-pause in vitro (Figure 3C), we wondered if the ΔSI3*-enhanced pause sites exhibited ce-pause sequence features. Strikingly, the sequence logo generated from 1357 WT pause sites enhanced by ΔSI3* (i.e. enhanced pauses in Figure 5E) strongly resembled the ce-pause logo (g–11G–10t–3g–2Y−1G+1) (4), although with more enrichment for –10 G, –3 T, –1 Y and +1 G and less enrichment for –11 G and –2 G (Figure 6A, top). In addition, ΔSI3*-specific pauses (i.e. significant pauses in Figure 5G) generated a sequence logo comparable to that of the ΔSI3-enhanced pauses (compare Figure 6A, top two panels). We hypothesize that SI3 reduces the strength of strong elemental pauses at which TL folding stabilizes a pretranslocated paused state (16) and that these pauses are favored by sequences with optimal matches to the ce-pause sequence. Hence, SI3 deletion increases pausing at these sites.

Figure 6.

SI3 exerts opposite effects on different types of pauses in vivo. (A) The sequence logos of WT pauses enhanced by ΔSI3* (corresponding to Figure 5E enhanced pauses), ΔSI3*-specific pauses (corresponding to Figure 5G pauses), all WT pauses, and the previously reported consensus elemental pause sequence (4). The four sequence elements contributing to elemental pause strength (5) are shown as colored bars above the logos and the relative information contribution of these elements to the overall pause consensus is shown in the bar graphs on the right. (B) Relative fractions of predicted PHs at ΔSI3*-suppressed pauses, at ΔSI3*-enhanced pauses, and at random genomic sites (shown as percentages). PHs positions are as shown in the diagram above the bar graphs. (C) In vitro transcription templates encoding putative hs-pause signals from NET-seq analyses. The predicted PHs of the putative hs-pause candidates. (D) In vitro transcription assays of the putative hs-pause candidates with WT and ΔSI3* RNAPs. The asterisk in the yfaSanti gel indicates a missing sample. (E) In vitro transcription assay of the putative hs-pause candidates by WT RNAP with NusA. (F) In vitro transcription assay of the putative hs-pause candidates by WT RNAP with PH-disrupting asDNAs.

Since ΔSI3* RNAP reduces hs-pausing in vitro, we next asked if ΔSI3* RNAP reduced pausing in vivo at known hs-pause sites in amino-acid biosynthetic regions (thrL1, hisL, pheL, ilvL, leuL, pheM and ivbL) (47,48) (Supplementary Figure S4A). ΔSI3* significantly reduced pause strength at these sites (ΔSI3* pause strength 45–80% of WT, Supplementary Figure S4B). For comparison, we examined two non-hs-pause sites, the pyrL54C and rfaQ56U; pyrL54C and rfaQ56U exhibited similar pause strengths in the ΔSI3* and WT strains (Supplementary Figure S4B. These results suggest that deletion of SI3 also reduces hs-pause strength in vivo.

To ask if other ΔSI3*-suppressed pause sites are associated with PHs, we examined RNA secondary structure predictions (41) for nascent RNA 40 nt upstream from pause sites (–50 to –11, where –1 is the pause RNA 3′ end) (Figure 6B). We screened for stem–loop RNA structures that paired to positions –11 to –14 upstream from the RNA 3′ end (–11 to –14 PHs). RNA hairpins at the –12 and –13 positions give the strongest PH effects, but –11 and –14 locations also may increase pausing at least in the presence of NusA (49,50). RNA molecules easily form compact structures due to wobble base-pairing and base-stacking (51,52); thus, we first determined the background level of structures predicted using our criteria by sampling 1500 pseudo 40-nt RNA sequences transcribed from random fragments of each genomic strand. Over a third of random forward and reverse strand sequences yielded a predicted RNA structure (38 ± 1% and 37 ± 3%, respectively; Figure 6B). A higher fraction of the ΔSI3*-suppressed pause signals (n = 3,134) yielded a putative PH (42% and 42% from two genomic strands, P = 0.021 and 0.00063, single-tailed Z proportion test). In contrast, ΔSI3*-enhanced pause signals (n = 1,357) yielded only background levels of PH predictions (39% and 36%, P = 0.34 and 0.57, single-tailed Z proportion test). Although predicted –12 PHs accounted for the majority of the predicted PHs, their portion was not statistically distinct among three pools tested. We designated the 1,321 ΔSI3-suppressed signals with possible PHs putative hs-pause signals.

In vitro validation of putative hs-pause signals

To ask whether the putative hs-pause signals indeed were stimulated by PHs, we selected three candidates to compare in vitro to the well-characterized hisL hs-pause (in malT, fabH and yfaS genes; Figure 6C; see NET-seq reads for these sites in Supplementary Figure S5A). Short (∼60-bp) fragments of the native sequences (–40 to +10 relative to the pause sites) were inserted into a λPR promoter-driven DNA template (Figures 6C, B). In vitro transcription assays revealed that the pause strength for each case was significantly decreased in using ΔSI3* RNAP relative to WT RNAP (Figure 6D). Using RNA sequencing ladders, we confirmed that each in vitro pause corresponded to the expected position based on NET-seq data (Supplementary Figure S5B). Further, addition of NusA, which is known to enhance hs-pause by promoting swiveling and stabilizing pause hairpins (17,53), increased pause strength for each candidate site (Figure 6E). Finally, the contributions of putative PHs to pause stabilization were confirmed by reductions in pause strengths upon the addition of 18-nt antisense DNA oligos (asDNAs) that specifically paired to the upstream PH stems (Figure 6F). These results collectively validate our assignment of putative hs-pause signals based on ΔSI3* suppression of pause index and PH prediction as criteria.

We conclude that hs-pauses are infrequent in E. coli (∼12% or 1,321 of the 10,700 pauses assigned by our analysis for WT RNAP appear to be hs-pauses; Supplementary Table S7). Additionally, our validation of hs-pauses establishes unambiguously that SI3 modulates different classes of pauses oppositely. Pauses resembling the consensus elemental pause are inhibited by ΔSI3, presumably because SI3 destabilizes the folded-TL pretranslocated ePEC state whereas it inhibited TL folding in the hairpin-stabilized, swiveled PEC (16).

ΔSI3*-enhanced pause and putative hs-pause signals are enriched in early ORF regions

We next investigated the distribution of ΔSI3*-enhanced and putative hs-pause signals across the genome. Overall, both types of pauses exhibited genomic distributions that are similar to each other and to pauses generally (4). The majority (63–69%) were located in sense transcripts of protein-coding sequences of genes (including the 5′ leader peptide coding regions of transcription units (TUs)), followed by the 5′ untranslated regions of protein-coding TUs (5′ UTRs, 10–12%) (54), (Figure 7A). We identified a small number of putative hs-pause sites in 3′ UTRs, which could be associated with intrinsic terminators. Some of each pause class also occurred in antisense TUs. When normalized for the number of bp in these regions, 5′ UTRs and 3′ UTRs were enriched in both types of pauses relative protein-coding regions (Pearson's chi-squared test, P < 0.005) (Figure 7B). This enrichment is consistent with the roles of pausing and tunable RNA structures in regulating transcription elongation/termination and translation in these two regions (4,55–57).

Figure 7.

Genome distributions and in vivo tests of ΔSI3*-enhanced pauses and putative hs-pauses. (A) Distribution of ΔSI3*-enhanced pauses and putative hs-pauses in different genome locations. (B) Densities of pauses in various genome regions. (C) Cumulative probability distributions of distances of pauses from gene starts (AUG codons) for WT pauses (grey), ΔSI3*-enhanced pauses (orange) and putative hs-pauses (blue). The approximate difference in cumulative probability at 250 bp for all pauses and putative hs-pauses is shown by horizontal dotted lines. (D) Designs of the lacZ reporters fused with N-terminal peptide sequences and the fabH and rpoH hs-pause signals along with their PH-mutants (PH–). Altered bases in PH– constructs are shown in white letters. (E) Expression comparisons of the lacZ reporters for hs-pause candidates and their mutants. Plot represents 6 biological replicates and their mean values.

We also examined how ΔSI3*-modulated pause sites were distributed within ORFs. ΔSI3*-enhanced pauses and putative hs-pauses were found at significantly higher levels in the early ORF region (first 250 bp), accounting for 56% and 60% of the totals (single-tailed Z proportion test, P = 0.003 and 10–5, respectively). Both ΔSI3*-enhanced pauses and putative hs-pauses were located closer to the start codons than all pauses in aggregate (two sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, single-tailed, P = 0.001 and 4 × 10–5) (Figure 7C). A consensus elemental pause sequence is known to be enriched coinciding with translation start sites (AU–1G+1 pauses) (4). These ‘AUG’ pauses were not enriched in the ΔSI3*-enhanced and putative hs-pauses relative to their frequency in all pauses (19 of 709 ΔSI3*-enhanced pauses and 4 of 844 putative hs-pauses were AUG pauses). Consistent with prior analysis of pauses in protein-coding regions (4), we conclude that ΔSI3*-modulated pauses are more prominent before ribosomes load on nascent mRNA and may aid in establishing transcription–translation coupling.

Hs-pause signals in early ORFs divergently affect gene expression through PH action

To ask if hs pauses detected early in ORFs indeed depend on a PH for function in vivo, we tested two such pauses in detail using translational fusions of the ORFs to a lacZ reporter preceded by the native ribosome binding site (RBS) from the candidate ORF and the lacUV5 promoter. These hs pauses were located at +59 nt of fabH and +76 nt of rpoH, respectively (Figures 7D and S5A). For each, we generated PH– variants by introducing base substitutions in the PH stem regions without changing the encoded protein sequences or forming alternative PHs (Figures 7D and S5B). RNA secondary structure predictions verified that the PHs were disfavored and that RNA structure of the RBSs remained largely unchanged in the mutant sequences (Supplementary Figure S6C). In vitro transcription assays verified that both hs pauses were significantly weakened in the PH– variants (Supplementary Figure S6D).

Strikingly, fabH and rpoH hs-pauses had opposite effects on gene expression. Relative to the PH– mutant, the PH-stabilized pause decreased lacZ expression ∼42% for the fabH pause but increased it ∼70% for the rpoH pause (Figure 7E). These divergent effects suggest the ORF-internal hs-pauses may play diverse roles in regulation but that these pause functions indeed depend of PH action. Inhibition of ρ with bicyclomycin at levels with minimal effects on cell growth (20 μg/ml) (58) reduced the effect of the rpoH PH (to ∼24%) but did not alter the fabH-PH effect (Supplementary Figure S6E). We speculate that the rpoH hs-pause may aid ribosome recruitment and transcription–translation coupling and thus decrease ρ-dependent termination (59) whereas the opposite effect of the fabH PH will require further study to understand.

Some pause sites, including some hs-pauses, generate tandem –2 and –1 RNA 3′ ends

While examining the ΔSI3*-modulated pauses in detail, we observed an unexpected correlation in which many enriched RNA 3′ ends occurred at directly adjacent positions (i.e. tandem pauses; Figure 8A; Supplementary Table S8). Further analysis revealed that some NET-seq pauses were scored with 3′ ends at the –2 register relative to the consensus sequence (pause before a pyrimidine) without the accompanying classical –1 pause after a pyrimidine (i.e. shifted register pauses; Figure 8A). The tandem pauses occurred more frequently among the class of ΔSI3*-suppressed pauses including hs-pauses. They occurred with highest probability among ΔSI3*-suppressed pauses lacking PHs (Figure 8B). Considering the tandem pause registers separately, ∼60% of the –2 pauses were ΔSI3*-suppressed and only a few were ΔSI3*-enhanced whereas 22% of the –1 pauses were suppressed and 20% of the –1 pauses were ΔSI3*-enhanced (Figure 8C). This bias in ΔSI3* effect on –2 and –1 of tandem pauses could partially explain why the sequence logo for ΔSI3*-suppressed pauses was more degenerate than observed previously for pauses in general and for ΔSI3*-enhanced pauses (Figure 8D).

Figure 8.

Tandem pauses found in NET-seq analyses. (A) Top, number of tandem pauses found in the WT strain. Bottom, the sequence logo of all –1 pauses in tandem pause pairs. (B) Fractions of tandem pauses for which both registers were ΔSI3*-enhanced or ΔSI3*-suppressed among all ΔSI3*-enhanced or -suppressed pauses found in the WT strain (shown as percentages); P values are from Z-proportion test. (C) Effects of ΔSI3* on all –2 and –1 registers among tandem pauses. P values are from Z-proportion test. (D) Sequence logos of all ΔSI3*-suppressed pauses and of ΔSI3*-suppressed pauses in the –1 and –2 registers of tandem pauses. (E) The tandem pause observed early in hisG. (F) Possible routes interconversion of –1 and –2 pauses by nucleotide addition, pyrophosphorolysis, hydrolysis, and phosphorolysis (60).The hisG pause sequence is shown. (G) In vitro transcription of hisG tandem pauses at various concentrations of PPi. Bottom bar graph shows the relative amount of –1 and –2 pauses at 3 time points after transcription restart at various PPi concentrations. (H) Ratios of tandem pause registers in WT NET-seq samples +/–apyrase treatment. Bar graph on the left shows the 3′-end changes for hisG tandem pauses. Scatter plot on the right shows 3′-end changes for tandem pause registers for WT NET-seq samples. Pause sites shown correspond to the WT samples depicted in panel A.

We also noticed that the frequency of tandem pauses and –2 pauses appeared to vary in different samples of the same strain and growth conditions prepared for NET-seq analysis. Of note, the DNA and RNA contacts of –2 pauses in the post-translocated register are the same as the contacts of –1 pauses in the pre-translocated register (Figure 8F). These observations led us to hypothesize that the apparent –2 pauses might arise by conversion of –1 pauses to –2 pauses during NET-seq sample processing. Current NET-seq protocols include an incubation in the presence of Mg2+ to digest DNA. Thus, the RNAP active center could be active during this step for nucleotide addition, pyrophosphorolysis, and intrinsic transcript cleave by OH– or phosphate (60).

To test this hypothesis, we first examined a tandem pause from the early hisG gene using in vitro transcription (Figure 8E, G). Like the fabH and rpoH hs-pauses (Supplementary Figure S6D), the hisG pause is hairpin-stabilized (–13 PH for –1 or –12 PH for –2, Figure 8E). In vitro, apparent pausing at both –2 and –1 was readily detected (Figure 8G). However, the –2 pause band was suppressed by addition of pyrophosphatase and was enhanced by even low concentrations of added pyrophosphate. These results establish that the canonical hisG hs-pause is highly susceptible to reversal of nucleotide addition (pyrophosphorolysis) and that the apparent –2 pauses might result from pyrophosphorolysis of –1 pauses. They do not, however, fully exclude the possibility that weak pausing might occur directly in the –2 register.

To ask if reversal of –1 to –2 pause RNA 3′ ends might occur during NET-seq sample processing, we adopted a different approach by adding apyrase to destroy NTPs in the samples prior to exposure to Mg2+. This approach had the advantage that it also tests whether nucleotide addition may occur during sample processing. If Mg2+ enables interconversion of –2 and –1 PECs during NET-seq sample processing by addition of a nucleotide to a –2 PEC, by pyrophosphorolysis of –1 PEC, or by 1-nt intrinsic cleavage of –1 PEC by OH– or Pi, then destruction of NTPs by apyrase is predicted to increase the observed –2/–1 RNA 3′-end ratio at apparent tandem pause sites. Strikingly, apyrase shifted the 3′ ends at both the hisG pause and tandem pauses generally more to the –2 position (i.e. apyrase increased the –2/–1 ratios; Figure 8H; Supplementary Table S9). This result suggests that both nucleotide addition to convert –2 to –1 pause registers and likely pyrophosphorolysis or 1-nt intrinsic cleavage by OH or Pi can occur during NET-seq sample preparation (Figure 8F).

Discussion

Our results lead to several important insights into the function of SI3 as a modulator of RNAP and pausing as well as into the accuracy of the NET-seq method. By deleting all of SI3 enabled by a suppressor substitution, we established that E. coli can grow relatively well without this important domain. However, ΔSI3* RNAP not only responds less effectively to RNA PHs it also pauses more strongly at consensus elemental pause sequences. By mapping hs-pauses based on the effect of ΔSI3* and RNA structure predictions, we found that ∼12% of pauses sites in E. coli are associated with PHs but that the distribution of hs-pauses is not dramatically different than pauses in general. Finally, the effects of ΔSI3* uncovered a class of apparent tandem pause sites that document difficulties in accurately capturing pause RNA 3′ ends by NET-seq and thus explain some discrepancies in prior descriptions of consensus pause sequences.

SI3 and TL residues shape TL dynamics

Although small deletions within E. coli SI3 are known to be viable and to alter pausing (42), a complete deletion of SI3 was thought to be inviable (23). β′A941T near the point of SI3 insertion in the TL enabled construction of a viable SI3 deletion and increased the rate of nucleotide addition by ΔSI3-RNAP (Figures 2 and 3A). However, β′A941T alone was inviable and decreased RNAP elongation rate (Figure 3A). These opposite effects of β′A941T in the presence and absence of SI3 highlight the complex dynamics of TL folding and unfolding that is easily perturbed by small changes (61–63). The added bulk and H-bonding capacity of Thr (64,65) may enable interactions with SI3 itself that slow TL folding but interactions with non-SI3 residues that aid TL folding when SI3 is absent. Alternatively, β′A941T may shift the folded–unfolded TL balance in the same direction in both cases, but this effect could be compensatory for ΔSI3 and over-shift the balance when SI3 is present.

Examination of TL sequences from bacteria with and without SI3 does not provide obvious insight into how β′A941T enables a viable SI3 deletion (Supplementary Figure S1; Supplementary Table S10). The helix2a region, where SI3 is inserted, is less conserved between bacteria with or without native SI3, likely due to adaptive evolution after SI3 insertion event. However, the Ala-to-Thr change itself is not evident in TLs lacking SI3 and an Ala-to-Thr substitution in yeast RNAPII, which contains Ala at the corresponding residue and lacks SI3, is phenotypically silent (63). TLs in archaeal RNAPs and eukaryotic RNAPII contain one less amino acid in TH2a but the region corresponding to β′A941 and two adjacent residues is not generally conserved other than that it typically containing smaller amino acids (e.g. G, A, S, V). It may be relevant that bacterial RNAPs lacking SI3 often contain Lys adjacent to the A941 position. Like Lys, Thr at A941 would increase the potential for side chain interactions that could be explain its ΔSI3-suppressor phenotype. SI3 interacts with both peripheral domains and dissociable factors (20,22,66). Thus, increasing the potential for interactions when SI3 is absent might be compensatory. A more systematic study of diverse substitutions in this region with and without SI3 would be required to explain the β′A941T phenotype more completely.

SI3 influences transcriptional pausing positively and negatively via multiple intermediates

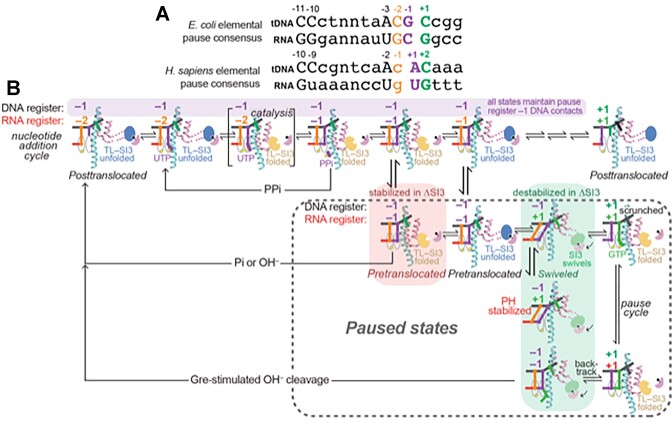

An emerging view of pausing emphasizes the roles of multiple interconverting paused states that range from pretranslocated PECs with a folded TL to swiveled PECs with a half-translocated RNA:DNA hybrid (Figure 9) (15). Different pause sequences may preferentially stabilize one or more state among of this ensemble of paused states. Collectively the ensemble stabilizes the PEC against formation of a post-translocated state competent for NTP binding and continuation of transcription.

Figure 9.

SI3 in interconverting PECs and transcription cleavage. (A) the consensus elemental pause sequence logos from E. coli and H. sapiens (4,8). These similar logos differ by 1 nt in the assigned positions of pause RNA 3′ ends (numbered here as –1 to match the published consensus sequences). Our results suggest the discrepancy between pauses sites detected by NET-seq relative to the consensus sequence could be due to changes in RNA 3′ ends during the NET-seq library preparation (e.g. by PPi/Pi/OH–-induced RNA cleavage). (B) routes of interconversion of EC/PEC states from the –2 species at the post-translocated register to the –1 species at the post-translocated register showing translocation registers and TL/SI3 states. SI3 is shown in different colors to indicate its position (blue, open; yellow, closed; green, swiveled). Note that –2 and –1 pause states maintain the same DNA contacts with the consensus pause sequence. For example, PPi may generate apparent –2 pauses from –1 pauses even though DNA contacts remain unchanged. Colored boxes, the effects of ΔSI3* on different pause states. Red box, ΔSI3* increases near consensus–sequence pauses that reside primarily in the pre-translocated state (16) because SI3 destabilizes the pre-translocated register. Green boxes, ΔSI3* decreases hs-pauses that reside primarily in the swiveled state (15) because SI3 stabilizes swiveling.

A major role of SI3 in pausing is stabilizing the unfolded TL when SI3 swivels as part of the RNAP swivel module (consisting mainly of the clamp, dock, jaw, shelf, and SI3) (1,15–17). Additionally, PECs can be stabilized in the pretranslocated register on sequences close to the consensus elemental pause (16). Our NET-seq results and in vitro validation substantiate these roles of SI3 in oppositely affecting different paused intermediates. SI3 promotes pausing at sites for which swiveling plays a dominant role, including hs-pauses, but inhibits pausing at sites where the TL-folded, pretranslocated PEC plays a dominant role (Figure 9).

Because SI3 mediates PH inhibition of TL folding in the swiveled PEC, we could identify hs-pauses based on the effect of ΔSI3* combined with RNA structure predictions. This analysis suggested that E. coli encodes a relatively large number (∼1300) of hs-pauses with different sequence contexts and PH structures genome-wide (Figures 6 and 7). We observed a slight bias in locations of hs-pauses (and strong elemental pauses inhibited by SI3) toward earlier regions of protein coding genes, but overall hs-pauses occur throughout transcribed regions. We did not include a free energy cut-off for RNA secondary structure prediction when identifying hs-pauses because NusA may chaperone formation of weak hairpins to promote pausing. Additionally, ternary interactions not captured in our prediction may stabilize PHs (67). Further analysis of the ΔSI3-suppressed pause sites using improved algorithms for RNA structure prediction that can detect complex RNA structures involving more nascent RNA may reveal additional hs-pause sites that tune transcription via novel mechanisms (68,69).

It is also notable that a significant fraction of pause sites are stabilized in ΔSI3*, presumably because the TL-folded, pretranslocated state is a significant pause intermediate at these sites. Although the strong elemental pause consensus sequence (ce-pause) is known to exhibit such stabilization (16), no E. coli pause sites exactly match the full consensus sequence. Our results suggest the TL-folded, pretranslocated state, which is stabilized by SI3 deletion, is a kinetically significant intermediate for a large number of pauses even when they match only the most highly enriched positions of the consensus pause sequence (e.g. –10, –1, and +1).

We note that our NET-seq analysis also verifies the predicted inhibition of pausing during ribosomal RNA gene transcription. During exponential phase, up to two-thirds of active RNA polymerases (RNAPs) are found in the rRNA region, which highlights the significance of rRNA transcription in bacterial growth (70,71). To enable uninterrupted and rapid rRNA transcription, a transcription antitermination complex (TAC) is formed, which helps prevent transcriptional pausing and premature termination (45). Our NET-seq analysis of wild-type and pause-altering RNAPs provides direct evidence supporting the effectiveness of the TAC in rRNA transcription (Figures 4B and 5C).

The limited effects of ΔSI3* on cell growth despite large effects on pausing may seem surprising if pausing plays crucial roles in regulation. Our study focused on the mechanistic role of SI3 in pausing and did not explore diverse growth conditions where effects of altered pausing on regulation would most likely manifest (e.g. minimal media, stress conditions, nonoptimal temperatures, or inhibitors). Even large reductions in pausing can have diverse effects (e.g. Figure 8). Further, the fact that ΔSI3* increases some pauses and decreases others may mask regulatory impacts of pausing. Although some pause sites may function correctly only at precise DNA locations, many may only need to act within a region (e.g. early in genes to promote transcription–translation coupling). Decreased pausing at sites could be compensated for by increased pausing at nearby sites, thereby masking impacts of ΔSI3*-altered pausing. Even a net increase in pausing may have limited impact because coupled ribosomes can suppress pausing (13,72).

NET-seq may not report precise pause sites and elongation dynamics accurately

Diverse bacterial RNAPs and mammalian RNAPII respond similarly to the E. coli consensus and anti-consensus elemental pause sequences in vitro (4), although some variations in in vitro pausing do occur (73). However, the consensus pause sequences derived from different NET-seq experiments vary even for the same species and sometimes indicate pausing before instead of after the U or C typically found at pause RNA 3′ ends (6–9). Our results suggest a possible resolution to these discrepancies by documenting that pause RNA 3′ ends can shift during NET-seq sample work-up either by reaction with NTPs or possibly by pyrophosphorolysis or intrinsic transcript cleavage (Figure 9). Although we have not extensively characterized these changes, the very low KNTPs for nucleotide addition at some template positions (74), the high rates of 1-nt cleavage observed for reaction with inorganic phosphate (60), and the high sensitivity of some pause RNA 3′ ends to pyrophosphorolysis reported here all suggest a need to develop NET-seq methods that employ more rapid quench of transcription and Mg2+-free sample preparation. Specifically, we suggest that the observation of pause consensus sequences for mammalian and yeast RNAPII similar to the E. coli consensus but shifted 1 nt upstream (8) may have resulted from cleavage reactions during sample processing (Figure 9). In the same vein, the extreme discrepancy in reported consensus sequences for B. subtilis RNAP (4,9) may reflect the consequences of RNA 3′-end changes that occur when NTPs, PPi, and Pi remain in reactive states during NET-seq sample preparation.

Overall, our findings both reveal the complex ways the SI3 modulates pausing and suggest a need to improve NET-seq methods to accurately capture nascent RNA 3′ ends in living cells. SI3 can increase pausing by favoring swiveling at some sites and decrease pausing at other sites by disfavoring stabilization of the pretranslocated, TL-folded state. New NET-seq methods should allow us to define the interconversion of these states in vivo with far greater accuracy and should be a key goal for mechanistic work on transcription elongation and pausing for the immediate future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank members of the Landick lab for insightful discussions and valuable feedback on the manuscript, Dr Michael Engstrom for help improving NET-seq library preparation procedures and data processing pipelines, Dr Michael Wolfe for assisting in statistical analysis of data, the Jue Wang lab and Dr Danny Fung for their assistance with microscopy imaging, and the Richard Gourse Lab and Dr Wilma Ross for providing materials and assistance with in vivo experiments. This work was supported by a grant the National Institutes of Health to R.L. (GM38660 ).

Notes

Present address: Yu Bao, MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge CB2 0QH, UK.

Present address: Xinyun Cao, Department of Microbiology, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA.

Contributor Information

Yu Bao, Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

Xinyun Cao, Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

Robert Landick, Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA; Department of Bacteriology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA.

Data availability

All NET-seq data sets are available at Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under the accession numbers GSE230757 and GSE240163 recording datasets for WT/ΔSI3* NET-seq and apyrase-treated NET-seq, respectively. NET-seq data processing scripts are available from the Zenodo repository (doi: 10.5281/zenodo.10159359).

Supplementary data

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Funding

National Institute of General Medical Sciences, U.S. National Institutes of Health [GM38660 to R.L.]. Funding for open access charge: NIH NIGMS [GM38660].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1. Landick R. Transcriptional pausing as a mediator of bacterial gene regulation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2021; 75:291–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mayer A., Landry H.M., Churchman L.S.. Pause & go: from the discovery of RNA polymerase pausing to its functional implications. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2017; 46:72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blombach F., Fouqueau T., Matelska D., Smollett K., Werner F.. Promoter-proximal elongation regulates transcription in archaea. Nat. Commun. 2021; 12:5524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Larson M.H., Mooney R.A., Peters J.M., Windgassen T., Nayak D., Gross C.A., Block S.M., Greenleaf W.J., Landick R., Weissman J.S.. A pause sequence enriched at translation start sites drives transcription dynamics in vivo. Science. 2014; 344:1042–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saba J., Chua X.Y., Mishanina T.V., Nayak D., Windgassen T.A., Mooney R.A., Landick R.. The elemental mechanism of transcriptional pausing. eLife. 2019; 8:e40981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vvedenskaya I.O., Vahedian-Movahed H., Bird J.G., Knoblauch J.G., Goldman S.R., Zhang Y., Ebright R.H., Nickels B.E.. Interactions between RNA polymerase and the “core recognition element” counteract pausing. Science. 2014; 344:1285–1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Churchman L.S., Weissman J.S.. Nascent transcript sequencing visualizes transcription at nucleotide resolution. Nature. 2011; 469:368–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gajos M., Jasnovidova O., van Bommel A., Freier S., Vingron M., Mayer A.. Conserved DNA sequence features underlie pervasive RNA polymerase pausing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49:4402–4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yakhnin A.V., FitzGerald P.C., McIntosh C., Yakhnin H., Kireeva M., Turek-Herman J., Mandell Z.F., Kashlev M., Babitzke P.. NusG controls transcription pausing and RNA polymerase translocation throughout the Bacillus subtilis genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020; 117:21628–21636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gong S., Wang Y., Wang Z., Zhang W.. Co-transcriptional folding and regulation mechanisms of riboswitches. Molecules. 2017; 22:1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lai D., Proctor J.R., Meyer I.M.. On the importance of cotranscriptional RNA structure formation. RNA. 2013; 19:1461–1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chan C.L., Wang D., Landick R.. Multiple interactions stabilize a single paused transcription intermediate in which hairpin to 3' end spacing distinguishes pause and termination pathways. J. Mol. Biol. 1997; 268:54–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Landick R., Carey J., Yanofsky C.. Translation activates the paused transcription complex and restores transcription of the trp operon leader region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985; 82:4663–4667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan C.L., Landick R.. The Salmonella typhimurium his operon leader region contains an RNA hairpin-dependent transcription pause site. Mechanistic implications of the effect on pausing of altered RNA hairpins. J. Biol. Chem. 1989; 264:20796–20804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kang J.Y., Mishanina T.V., Bellecourt M.J., Mooney R.A., Darst S.A., Landick R.. RNA Polymerase Accommodates a Pause RNA Hairpin by Global Conformational Rearrangements that Prolong Pausing. Mol. Cell. 2018; 69:802–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kang J.Y., Mishanina T.V., Bao Y., Chen J., Llewellyn E., Liu J., Darst S.A., Landick R.. An ensemble of interconverting conformations of the elemental paused transcription complex creates regulatory options. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023; 120:e2215945120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guo X., Myasnikov A.G., Chen J., Crucifix C., Papai G., Takacs M., Schultz P., Weixlbaumer A.. Structural basis for NusA stabilized transcriptional pausing. Mol. Cell. 2018; 69:816–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]